Markets, especially in the United States, have become increasingly concentrated in recent years (Wu, Reference Wu2018). The consequences of market concentration are far-reaching. Concentration is associated with decreased competition, increased prices, and reduced productivity (Grullon et al., Reference Grullon, Larkin and Michaely2019; Philippon, Reference Philippon2019). The costs of concentration may also go beyond the economy and affect political power and representation. Large firms have more political influence (Rickard, Reference Rickard2012; Kim and Osgood, Reference Kim and Osgood2019), which can facilitate further consolidation of their political and economic power (Callander et al., Reference Callander, Foarta and Sugaya2024). To the extent that the preferences of large firms conflict with those of the public, concentration can undermine the representation of the public interest and erode democratic institutions.

Antitrust law (also called competition law) was created to limit anticompetitive actions by firms and to promote fair and competitive markets. Antitrust pits the interests of large firms against the public (Weymouth, Reference Weymouth2016; Lee and Pond, Reference Lee and Pond2025).Footnote 1 Political action to strengthen antitrust has historically relied on broad coalitions that included strong public support (Purdy et al., Reference Purdy, Lindahl and Carter1946; Gordon, Reference Gordon1963).

Consistent with this historical account, politicians and the public have recently renewed the campaign to strengthen antitrust. Although antitrust is a complex policy area, citizens express widespread support for market competition and opposition to monopolies, and they are broadly supportive of antitrust (Orth, Reference Orth2023). Politicians are also supportive. Democratic Senator Warren argues that antitrust legislation protects “workers, entrepreneurs, small businesses, and families from being squeezed even more by harmful mergers” (Warren, Reference Warren2020). Republican President Trump noted that mergers can put “too much concentration of power in the hands of too few” (Stephensen, Reference Stephensen2016). With public officials continuing to look to public opinion to guide their decision-making (Griffin and Newman, Reference Griffin and Newman2005; Butler and Nickerson, Reference Butler and Nickerson2011), we examine how arguments about antitrust affect public opinion in the United States.

This paper assesses common arguments that are presented in media coverage of antitrust, and it evaluates which appeals are most compelling to the American public. We fielded two survey experiments in the United States in 2020, which find that respondents are not moved by common economic arguments about prices and small businesses. They are instead attuned to concerns about fairness: they are supportive of antitrust if it rewards hard work and grants everyone an equal chance to succeed. Republican respondents are more concerned about antitrust harming companies than Democrats, whereas Democrats are more concerned with limiting corporate political influence. Taken together, the results point to the broad-based appeal of antitrust, especially framed in terms of fairness. At the same time, partisan divisions remain over whether antitrust threatens democratic institutions or business interests.

1. Public support for antitrust

To understand how the public evaluates antitrust and what arguments influence public support for antitrust, we begin with a broad theoretical approach that draws on economic and psychological foundations. Since there is little systematic analysis of public support for antitrust, we cast a wide net that generates a diverse set of theoretical perspectives and hypotheses. Two recent exceptions are Brutger and Pond (Reference Brutger and Pond2025), who examine how public opinion on antitrust is shaped by global markets, and Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Sophie and Nicholas2025), who look at motivations for antitrust beyond the consumer welfare standard.

1.1. Economic effects

We begin with a straightforward assessment of economic arguments surrounding antitrust. Since antitrust is designed to enhance competition and prevent collusion in the marketplace, it should reduce prices (Lande, Reference Lande1982). However, there is disagreement in the academic literature about how much the mass public understands the price effects of economic policies. Some studies find that trade policy preferences are influenced by price considerations (Casler and Clark, Reference Casler and Clark2021) and that informing respondents about price effects allows them to incorporate prices into their decision-making (Rho and Tomz, Reference Rho and Tomz2017). Others show that price benefits do not necessarily affect preferences (Bearce and Moya, Reference Bearce and Moya2020; Mutz, Reference Mutz2021). It thus remains an empirical question whether the public will respond favorably to information about the price benefits of antitrust policy.

Additionally, helping small businesses may provide a convincing justification for antitrust. Firms can use their dominant positions to erect entry barriers and prevent new firms from entering markets (Kennard, Reference Kennard2020; Perlman, Reference Perlman2020). When the public is aware that antitrust helps small companies participate, they might become more supportive of antitrust. A recent article follows this line of reasoning, noting that “legislation would protect independent businesses from the predatory behavior of dominant companies” (Amott, Reference Amott2022). At the same time, enforcement of antitrust in the United States has often placed small firms at a disadvantage (Foster and Thelen, Reference Foster and Thelen2024). Where small firms cannot cooperate with each other, it is harder for them to compete against large firms. Our survey allows us to assess the extent to which the public finds the price and small business arguments compelling.

H-1a. Americans will become more supportive of antitrust when they are informed that antitrust reduces prices or enables small companies to participate in the market.

The expectations presented thus far focus on economic arguments in favor of antitrust. Antitrust is also subject to criticism. One economic argument against antitrust is that the largest companies have expanded because they worked the hardest, and limiting their growth punishes their productivity. Alan Greenspan summarized the argument: “The actual practice of the antitrust laws in the United States has led to the condemnation of the productive and efficient members of our society” (Greenspan, Reference Greenspan1966).

We also anticipate that certain people are more likely to be receptive to this argument. We focus on partisanship here, as partisanship is an increasingly relevant political cleavage in the United States, and partisans of each major party tend to view government intervention differently. Republicans tend to be more supportive of business interests and more concerned about burdening businesses with government regulation (Short, Reference Short2022b). We thus expect that Republicans will be more responsive to arguments that entrepreneurs should be rewarded for their efforts and that breaking up big, successful businesses may only punish those who worked the hardest. The following summarizes our expectations.

H-1b. Americans will become less supportive of antitrust when informed that antitrust punishes companies that are successful. Republicans will have a stronger negative reaction than Democrats to this information.

1.2. Fairness

Though the public may be concerned about successful companies being punished by antitrust, an alternative argument is that antitrust could be used to make the economy more fair. For example, Democratic Senator Klobuchar argued that “Protecting competition speaks to the basic principles of economic opportunity and fairness” (Klobuchar, Reference Klobuchar2017). Similarly, Republican Senator Grassley emphasized the need for stronger antitrust legislation, noting “Our bill will help create a more even playing field” (Grassley, Reference Grassley2021). These arguments tap into the moral concept of fairness, which guides individual and group behavior and is often thought to be a universal norm (Lü et al., Reference Lü, Scheve and Slaughter2012; Kertzer and Rathbun, Reference Kertzer and Rathbun2015; Brutger and Rathbun, Reference Brutger and Rathbun2021).

When considering the importance of fairness for antitrust, we focus on two related types of fairness—equity and equality. Antitrust could ensure that the hardest-working entrepreneurs will be the most likely to succeed, which taps into equity concerns that outcomes are proportional to effort (Ballard-Rosa et al., Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2017). Similarly, antitrust could be used to ensure that everyone has an equal chance to compete and succeed, which taps into concerns for equal opportunity. In practice, concerns for equity and equality frequently go hand-in-hand, and we have no reason to find one argument more convincing. We thus hypothesize and test whether raising each type of fairness argument affects antitrust support.

H-2. Americans will become more supportive of antitrust when they are informed that antitrust can help provide more equal or equitable opportunity.

1.3. Democracy

Antitrust policy could also be related to democracy. Democratic governments are thought to prioritize the public interest, as they must attract widespread support to remain in power. Where business interests conflict with the public interest—often in areas like environmental or labor regulation and corporate taxation—factors that increase business influence may undermine the representation of the public interest. One factor that increases the political influence of businesses is their size. Large firms can more easily overcome collective action problems and pressure the government for their preferred policies (Betz, Reference Betz2017; Osgood, Reference Osgood2018; Brutger, Reference Brutger2023). By limiting the size of businesses and preventing cooperation among them, antitrust could help reduce the political influence of big businesses. Newspaper headlines echo these ideas declaring, “Monopolies Threaten Not Just Our Economy, But Our Liberty, Too” (Gleason, Reference Gleason2020). We expect that respondents will become more supportive of antitrust when they are informed that antitrust can curb business influence and help maintain democratic institutions.

We additionally expect there to be partisan divides when it comes to concerns about democratic erosion and the political influence of large companies. Consistent with polling that shows that Democrats are more likely to believe that American democracy is under threat (Orth and Frankovic, Reference Orth and Frankovic2022), we expect Democrats to be more supportive of antitrust efforts aimed at weakening business influence and preserving the democratic process.

H-3. Americans will become more supportive of antitrust when they are informed that antitrust can help maintain democratic institutions by reducing the chance that large companies control government policy. Democrats will have a stronger positive reaction than Republicans to this information.

2. Research design

Our empirical approach uses a two-pronged strategy to evaluate the prevalence and persuasiveness of arguments about antitrust. We begin with a descriptive media analysis to assess which arguments are most prevalent in American media coverage of antitrust. We then move to the experimental portion of our analysis. The experiment exposes respondents to common arguments advanced in public debates on antitrust and allows us to measure which arguments are persuasive in moving public opinion.

2.1. Analysis of antitrust media coverage

We conducted a search of news coverage in the United States to identify common arguments advanced in support of, and opposition to, antitrust policy. Using Nexis Uni, we searched for news articles that included “antitrust AND policy OR enforcement” published between 1990 and August 2021. From this search, we selected a random sample of 525 articles that were manually coded by a team of research assistants.Footnote 2 The coding identified which frames and arguments are prevalent in the media’s reporting on antitrust.

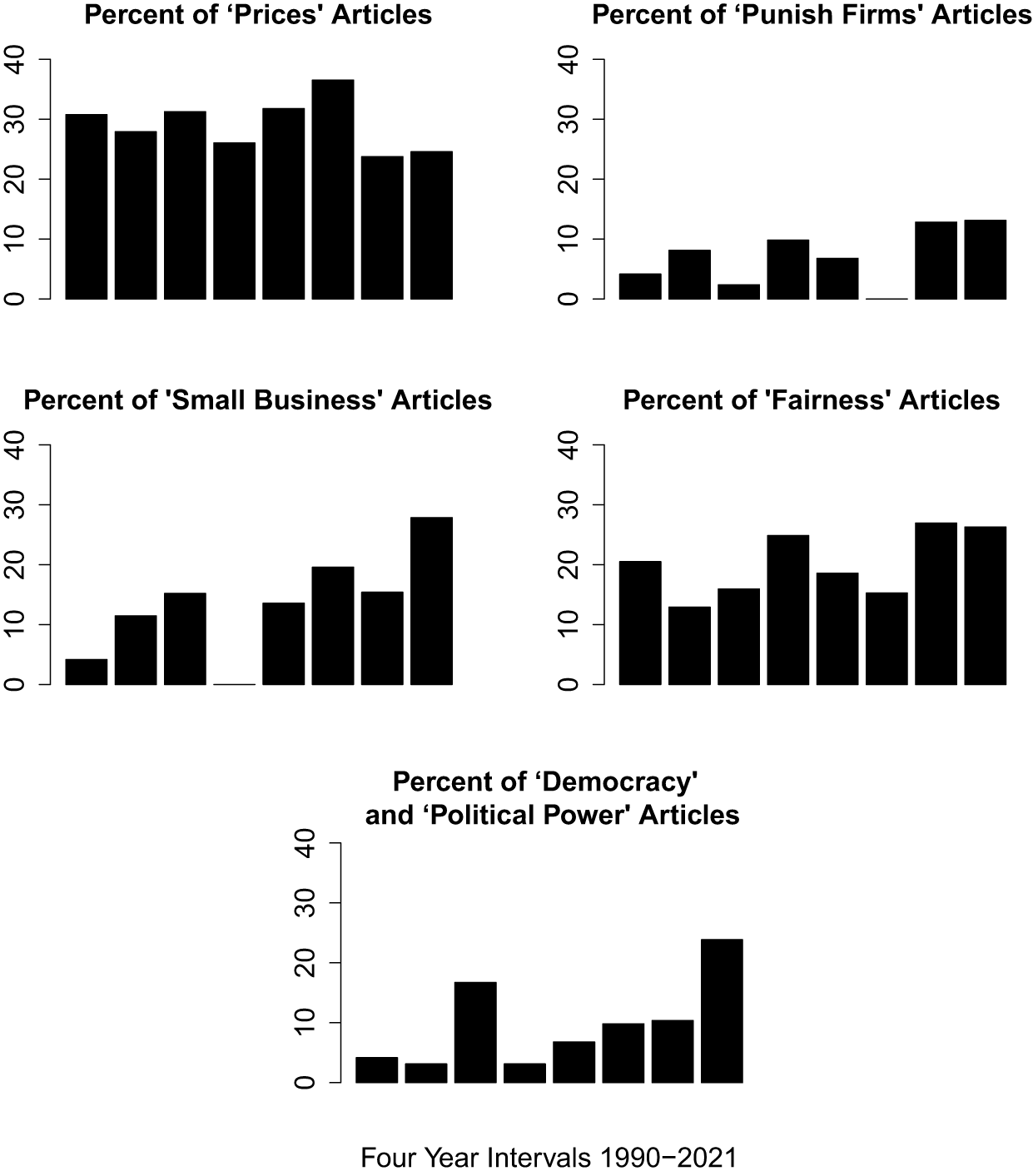

Figure 1 displays the composition of antitrust media coverage over time in several issue areas. The majority of the news articles provided basic information about antitrust promoting competition in the marketplace (57 percent), which has been relatively constant across time. The next most common theme focused on the potential for antitrust to reduce prices, which appeared in 24 percent of the articles. 22 percent of articles focused on the connection between antitrust and fairness. 16 percent focused on the importance of antitrust for democracy and curbing the political power of large companies. Eight percent of the media coverage discussed the potential for antitrust to harm or punish large firms. Arguments emphasizing fairness, democracy, and harming firms all increased in prominence in recent years.

Figure 1. Composition of antitrust media coverage: 1990–2021.

2.2. Experimental analysis of antitrust arguments

To evaluate the effect of different arguments about antitrust, we use a survey experiment. The experiment allows us to randomize the information that survey respondents read about antitrust so we can estimate how different types of information affect public opinion on antitrust. We used Lucid to field our experiment during the Summer of 2020. Survey samples from Lucid track well with U.S. national benchmarks (Coppock and McClellan, Reference Coppock and McClellan2019) and are increasingly used in social science research, including many political science articles.Footnote 3We used a number of best practices to limit our sample to attentive respondents, which resulted in a sample of 3,539 respondents in our first module, as discussed in Appendix, § A.1. Our hypotheses were not pre-registered, and we report results for all treatments and their interactions with partisanship.

Our survey experiment proceeds through two modules. In the first module, we provide a basic summary of antitrust law to all survey respondents. Because the laws governing antitrust and their execution are complex, we were concerned that respondents might not know what antitrust is. However, citizens have opinions about small businesses (and large ones), competitive markets, and government regulation. Similar to Brutger and Pond (Reference Brutger and Pond2025), all respondents read the following description in order to connect the ideas that they know and understand to the antitrust nomenclature,Footnote 4 “Antitrust laws prohibit certain mergers and anticompetitive business practices. The prohibited practices include the creation of monopolies or coordination among companies to split markets, fix prices, or limit production. Antitrust laws are frequently enforced against large companies.”Footnote 5

Respondents were then assigned to one of four treatment groups. The first group is a control, where respondents were given no additional information. The respondents in the control group read the basic summary of antitrust law above and were then asked about their opinion on antitrust law: “Do you think the United States government should strengthen or weaken its antitrust laws?” (5 = dramatically strengthen, 1 = dramatically weaken). We use the five-point response scale from this question for the dependent variable. In order to understand baseline attitudes toward antitrust, we look at the average level of support among respondents in the control group. We find that the majority of respondents in the control group, 59 percent, support strengthening antitrust laws (either dramatically or somewhat). We also find partisan differences in baseline support for antitrust policies: 67 percent of Democrats and 59 percent of Republicans support strengthening antitrust laws in the control group (8.3, ![]() $p \lt $ 0.03).Footnote 6

$p \lt $ 0.03).Footnote 6

In the first experiment, each respondent was provided with the same information as in the control group, but an additional sentence was added for the randomly assigned treatment groups. Our first module included the following three informational treatments.

Prices: Some argue that antitrust laws promote competition, which reduces the price of goods and services for consumers.

Small Businesses: Some argue that antitrust laws promote competition, which enables small companies to participate in the market.

Punish Companies: Some argue that antitrust laws punish companies that are successful, since successful companies tend to grow fastest, and antitrust laws could slow the growth of such companies.

The results of the experiment are reported in Table 1. Only the Punish Companies treatment has a strong and significant effect. Consistent with H-1b, the Punish Companies treatment results in a significant decline in support for strengthening antitrust laws as shown in model 1 of Table 1, which is also robust when controlling for respondents’ demographics (model 2). Substantively, the Punish Companies treatment decreases the percentage of respondents who somewhat or strongly support strengthening antitrust laws by about 9 percentage points.

Table 1. Effects of treatments on support for antitrust laws

Notes:

† p < 0.1; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. The dependent variable is a 5-point measure ranging from 1 to 5 with higher values associated with greater support for strengthening antitrust laws. The interaction models are limited to Democrats and Republicans.

Notably, the economic arguments in favor of antitrust laws generate clear null results for that component of H-1a. The Prices treatment does not have a substantive or statistically significant effect, with the estimated effect measuring at about 1 percentage point.Footnote 7 Similarly, the Small Businesses treatment has a negligible effect but is actually signed in the negative direction, contrary to our expectation. These results suggest that even when the public is provided information about the consumer benefits of antitrust laws and their ability to help small businesses, their attitudes are not moved by such arguments.Footnote 8

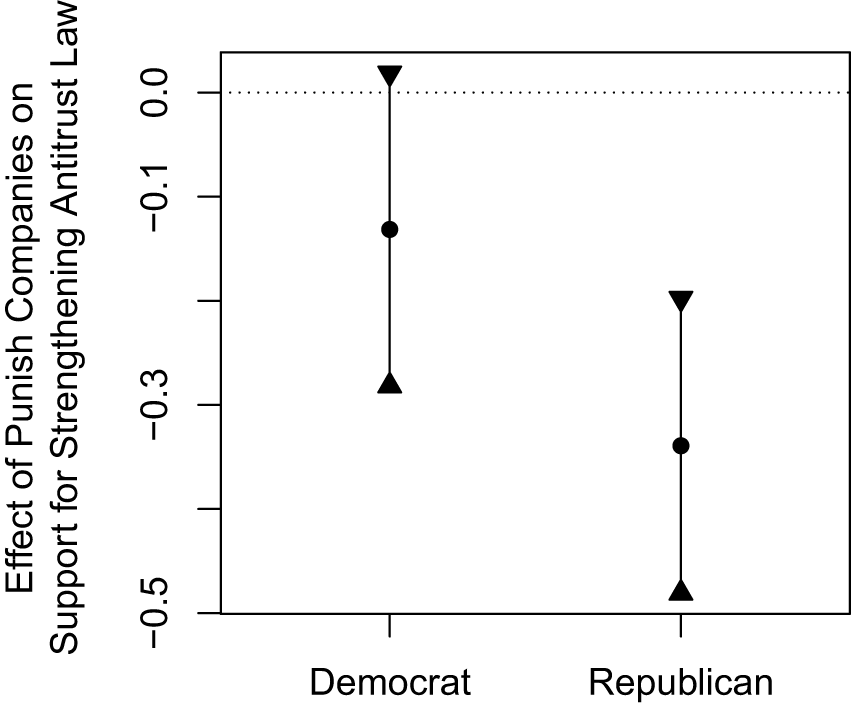

We now test whether Republicans have a stronger negative reaction to the Punish Companies treatment than Democrats (H-1b). To test this hypothesis, we first subset the data to those who identify as either Republicans or Democrats and then run a series of interaction models that interact our treatments with an indicator of whether the respondent identifies as Republican. The results are displayed in models 3 and 4 of Table 1. We find that Republicans have a significantly stronger negative reaction to the Punish Companies treatment than Democrats. While the main effect of the Punish Companies treatment is negatively signed, it is much smaller and only marginally significant for Democrats, whereas the interaction with the Republican indicator is highly significant and about twice the magnitude, as the marginal effects show in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Heterogenous treatment effects by partisanship for Punish Companies.

2.3. Concerns for fairness and democracy

We now turn to our second experimental module, which examines how concerns for fairness and democracy shape support for antitrust laws. The second experiment follows the same recruitment and screening procedures as the first experiment, which resulted in a sample of 5,475 respondents.Footnote 9 Each respondent in the second experiment was first presented with the text of the control condition, which read “Antitrust laws are designed to protect the process of competition in the economy by limiting the growth of some domestic companies.”Footnote 10 For respondents randomly assigned to one of the treatment conditions, they read the text from the control, which was then followed by the text from one of the following treatments.

Hard Work: Antitrust laws can also make it more likely that those who work hardest are more likely to succeed in the economy. By limiting the growth of some domestic companies, antitrust laws ensure hard-working entrepreneurs have a chance to compete and succeed.

Equal Chance: Antitrust laws can also make it more likely that everyone has an equal chance to succeed in the economy. By limiting the growth of some domestic companies, antitrust laws ensure everyone has a more equal chance to compete and succeed.

Democracy: Antitrust laws are also important for the maintenance of democratic institutions, as they reduce the chance that large domestic companies will control government policy.

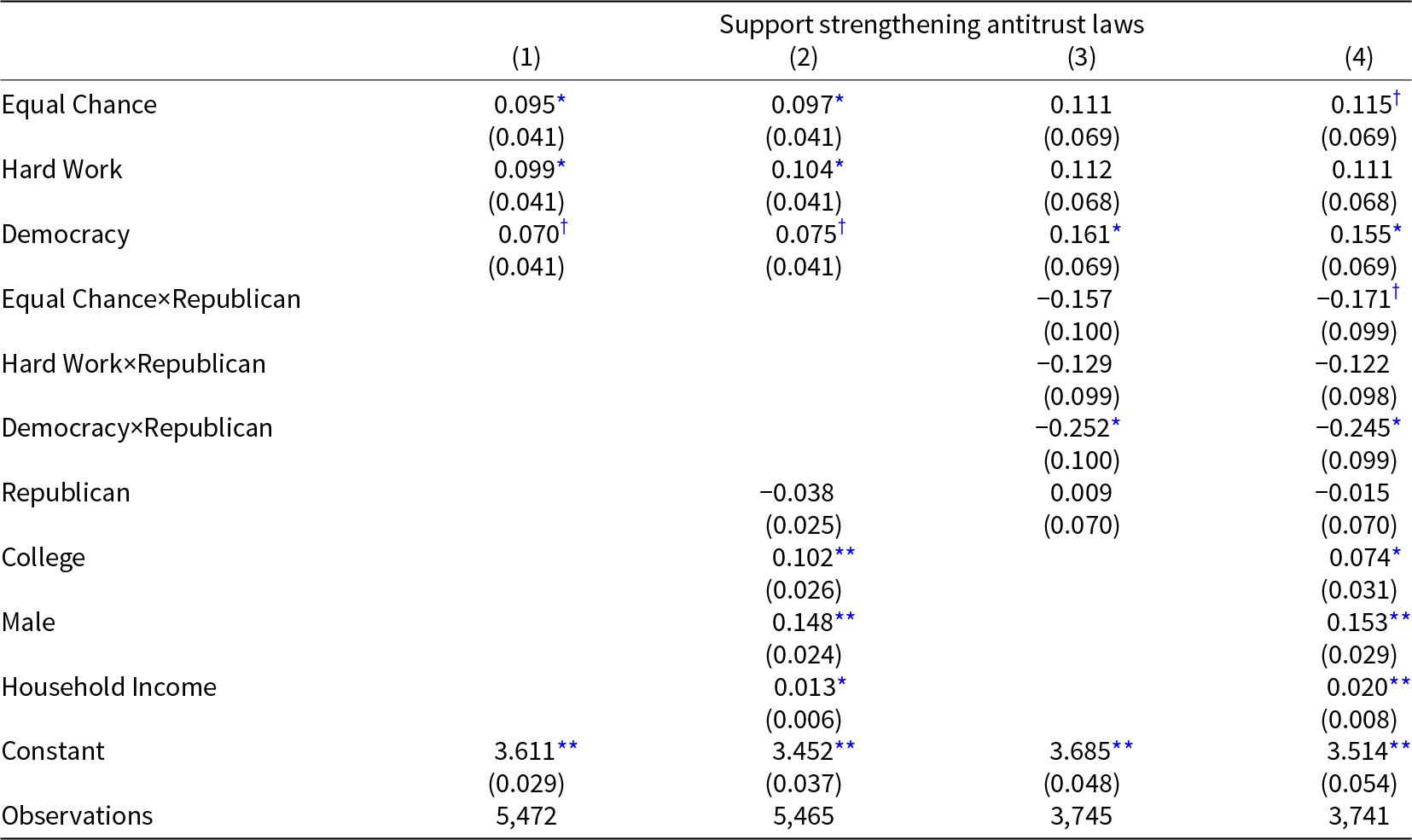

We present the results from the second experiment in Table 2. The Hard Work and Equal Chance treatments describe how antitrust can promote fairness, which we expect to increase support for strengthening antitrust laws as proposed in H-2.Footnote 11 We find that the Equal Chance and Hard Work treatments both have strong positive effects on support for antitrust laws.Footnote 12 In substantive terms, the two treatments lead to 4.9 and 5.3 percentage point increases of the number of respondents who support strengthening antitrust laws, respectively.

Table 2. Effects of fairness and democracy on support for antitrust laws

Notes:

† p < 0.1; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. The dependent variable is a 5-point measure ranging from 1 to 5 with higher values associated with greater support for strengthening antitrust laws. The interaction models are limited to Democrats and Republicans. The models also include our negative-fairness treatments, which are discussed and displayed in full in the Appendix, § A.2.

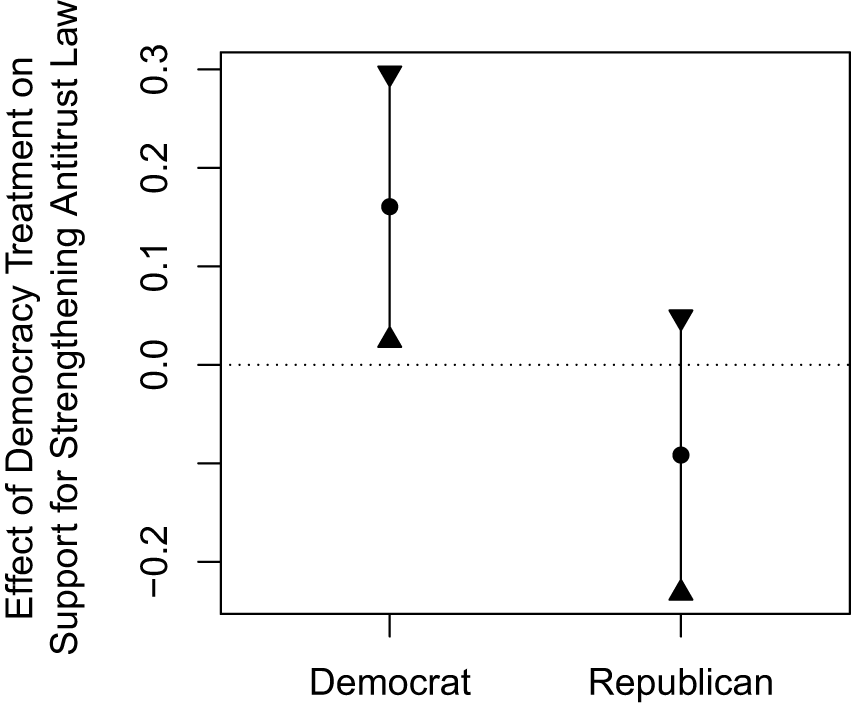

The Democracy treatment tests H-3, which expects support for antitrust laws to increase when people learn that antitrust laws can help maintain democratic institutions, with the expectation that the effect will be larger among Democrats than Republicans. We find a positive effect of the Democracy treatment, but it is significant only at the 10 percent level. However, when we test the partisan hypothesis, we find that the modest main effect of the Democracy treatment is driven by the divergent reactions of Democrats and Republicans. As we did with our first experiment, we subset the analysis to only those who identify as Democrat or Republican. Table 2 reports the regression results in models 3 and 4. Figure 3 displays the marginal effects of the treatment, highlighting the strong positive effect of the treatment among Democrats, while also showing that Republicans have a generally negative reaction to the treatment, though not statistically significantly different than zero. These results provide clear support for our partisan hypothesis, illustrating a strong partisan divide when it comes to using antitrust laws to protect democracy from the influence of large companies.

Figure 3. Heterogenous treatment effects by partisanship for democracy treatment.

3. Conclusion

The analysis presented here sheds light on the microfoundations of support for antitrust in the United States. We find that Democrats are about 9 percentage points more likely to support strengthening antitrust laws than Republicans. This finding is consistent with Democrats’ general support for relatively more government intervention in the economy than Republicans’ and their desire to rein in the power and influence of the largest companies.

This paper also tests the effects of many prevalent arguments about antitrust. Our treatments emphasizing the price benefits of antitrust laws and their ability to help small businesses did not have an effect on antitrust support. However, we found that the public is receptive to arguments about how antitrust law could punish successful companies. We find that respondents are more than 9 percentage points less likely to support antitrust when exposed to the argument that successful companies may be harmed by such policies, and this effect is larger among Republicans. The concern over antitrust laws’ potential to harm companies is consistent with a concern for fairness, where the public doesn’t want companies to be unnecessarily punished. Further probing sensitivity to fairness, we found that invoking concerns about equity and equality significantly moves public support for strengthening antitrust laws. These results are consistent with a broader literature in political psychology that emphasizes the importance of moral concerns in shaping political attitudes.

Our work also probed whether the public is receptive to ideas about antitrust and democratic institutions. Democratic respondents are more supportive of strengthening antitrust law to constrain the political power of large companies. Republicans are not persuaded by this line of argumentation, and the treatment actually had a marginally negative effect on their support for strengthening antitrust.

This partisan divergence highlights that although support for antitrust is bipartisan, differences are likely to emerge in how antitrust should be executed. While some arguments, like invoking concerns about fairness, resonate across the political spectrum, many of the arguments that politicians invoke either have no effect or have divergent effects among Democrats and Republicans.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.10016. To obtain replication material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MYZCO6.

Acknowledgements

This project has benefited from the generous feedback provided by Timm Betz, David Broockman, Tim Büthe, Alex Debs, Dirk Leuffen, Hannah Löffler, Nina Obermeier, Cleo O’Brien-Udry, Erik Peinert, Tyler Pratt, Didac Queralt, Thomas Sättler, Gerald Schneider, Nicholas Short, David Stasavage, Jan Stuckatz, Lora Anne Viola, Stephen Weymouth, and from participants at workshops and conferences where earlier versions of the paper were presented. We also thank Emma Guard, Katie Lee, Strong Ma, Abby Morris, Camilla Rodriguez Torres, and Avery Wheless for their research assistance on this project.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.