1. Introduction

In today’s increasingly polarized political landscape, the division between urban and rural communities has become highly visible in various micro- and macro-political phenomena such as voting behavior, trust, and perceived effectiveness of electoral and representational processes. Yet, while much attention has been paid to the differences between urban and rural populations, less is known about how these divides play out in the realm of issue salience across time and space. Understanding these divides sheds light on the broader dynamics of political representation and the policy process in electoral democracies. In this study, we ask the following research questions: Do rural and urban populations prioritize different policy problems, and how have these priorities evolved over time? How does partisanship interact with place-based gaps in priorities? Answers to these questions will help us gain a deeper understanding of the role of geography and partisan cues in opinion formation.

Decades of empirical research have identified significant differences in key aspects of political life between urban and rural areas. These differences range from voting patterns (Scala and Johnson, Reference Scala and Johnson2017; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Lucas, Armstrong and Bakker2023), nonvoting political behavior (Lin and Lunz Trujillo, Reference Lin and Lunz Trujillo2023b), perceptions of representation, geographic bias, and group consciousness (Walsh, Reference Walsh2012; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Jennings and Stoker2023a) to trust (Mitsch et al., Reference Mitsch, Lee and Ralph Morrow2021; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Jennings and Stoker2023b), external efficacy (García del Horno et al., Reference del Horno, Rubén and Hernández2023), place resentment (Munis, Reference Munis2022; Jacobs and Munis, Reference Jacobs and Kal Munis2023), populist and anti-science attitudes (Lunz Trujillo, Reference Lunz Trujillo2022), as well as attitudes toward a broad range of public policies (Diamond, Reference Diamond2023; Lin and Lunz Trujillo, Reference Lin and Lunz Trujillo2023a), among other areas. The breadth of these variances arguably makes it challenging to achieve a holistic understanding of the aggregate impact they have on the political identities of individual citizens living within an urban versus rural dichotomy. Still, scholars focusing on various aspects of the urban–rural divide in politics have made considerable progress in advancing our understanding of the political behavior and attitudes of rural and urban populations.

For understandable reasons, most scholarly attention in the literature has focused on the differences in voting patterns between urban and rural areas. Recent research has shown that the urban–rural divide in party identification has grown considerably in many countries in the past century, and the United States is no exception (Gimpel et al., Reference Gimpel, Lovin, Moy and Reeves2020; Mettler and Brown, Reference Mettler and Brown2022; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Lucas, Armstrong and Bakker2023; Zumbrunn, Reference Zumbrunn2024). Although this widening gap has led to renewed interest among scholars in understanding geographic divisions in political attitudes, studies almost exclusively used questions of policy preferences when examining the urban–rural divide in attitudes. This represents a missed opportunity, as the heavy focus on policy preferences overlooks other critical aspects of attitudes toward public policies and representation. To that end, Broockman Reference Broockman(2016) highlighted the importance of incorporating policy priorities especially when the question of interest is ideological congruence between voters and elites. As Jones and Baumgartner (Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005, p. 250) noted, “most scholarship on representation focuses on the correspondence in the policy positions of representatives and the represented … but this approach is incomplete, because it neglects priorities among issues. How representative is a legislative action that matches the policy preferences of the public on a low-priority issue but ignores high-priority issues?”

We make several empirical and theoretical contributions to the literature on urban–rural gaps in political behavior and policy attitudes. First, we turn our attention from policy preferences to policy priorities—an underexplored aspect of the urban–rural divide in the American public.Footnote 1 Building on recent scholarship e.g.,Lin and Lunz Trujillo Reference Lin and Lunz Trujillo(2023a), our main objective is to explore the extent to which urban residents differ from those living in rural areas and small towns, and whether geographical gaps in policy priorities intersect with partisan differences. If the policy priorities of citizens living in rural and other peripheral areas deviate little from those of urban citizens or align closely with partisan lines, then the prospects for nonurban interests being effectively voiced in the legislative agenda will be greatly enhanced.

Our second contribution addresses the rigidity of rural identity and the distinctiveness of rural policy priorities. By relaxing some of the assumptions regarding the stability of place-based gaps in policy attitudes, we explore differences between urban and nonurban residents across a wide array of policy areas over time and across different regions. Building on studies examining the role of local economic and ideological context in shaping sociospatial cleavages e.g., Yang (Reference Yang1999), Scala and Johnson (Reference Scala and Johnson2017), Hertz and Silva (Reference Hertz and Silva2020), Potrafke and Roesel (Reference Potrafke and Roesel2020), Bonomi et al. (Reference Bonomi, Gennaioli and Tabellini2021), Rodden (Reference Rodden2022), we test the idea that the ideological orientation of state policies i.e., policy liberalism; Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw(2016) and state-level income inequality (Frank, Reference Frank2014; Grossmann et al., Reference Grossmann, Jordan and McCrain2021) affect urban–rural cleavages in policy attitudes in important ways.

We test our theoretical expectations using a newly introduced dataset of content-coded policy priorities of over 1.1 million Americans from the period of 1939–2020 (Yildirim and Williams, Reference Yildirim and Williams2024). We start by examining urban–rural gaps in policy priorities across decades and show that there are episodic, albeit fairly small, gaps in policy priorities across urban and rural populations, even after controlling for essential demographic and political variables. Consistent with the arguments put forward by Mettler and Brown Reference Mettler and Brown(2022), the urban–rural gap in the prioritization of many policy areas including the economy and areas related to family and moral values has widened over the past four decades. Crucially, we also show that state-level political and socioeconomic conditions such as state policy ideology and income inequality have relatively little influence over the urban–rural gap in priorities. In a subsequent analysis, we examine the extent to which urban–rural gaps in issue priorities crosscut partisan differences and find that the policy priorities of voters living in rural and urban areas closely reflect partisan divisions in policy agendas. This supports the idea that place-based gaps are dwarfed by partisan gaps in policy priorities (Lin and Lunz Trujillo, Reference Lin and Lunz Trujillo2023a). We discuss the implications of our findings for the study of place-based differences in political attitudes and representation.

2. Literature review

2.1. Place-based gaps in policy priorities

Empirical research studying urban–rural gaps in policy attitudes and voting behavior focused largely on urban politics until recent decades, leaving various aspects of the rural side underexplored (Gimpel and Karnes, Reference Gimpel and Karnes2006). Over the past decade, there has been a considerable increase in the volume of studies exploring the political and social identities of ruralites and the consequences of these identities for political behavior and policy preferences e.g., Gimpel et al. (Reference Gimpel, Lovin, Moy and Reeves2020), Lyons and Utych (Reference Lyons and Utych2023), Lunz Trujillo (Reference Lunz Trujillo2024). Despite recent advances, however, there is a notable scarcity of research examining the temporal and spatial variability of the urban–rural gap in policy attitudes and priorities, with the majority of studies focusing on the disparities between urban and rural areas at a single point in time (see Gimpel et al. (Reference Gimpel, Lovin, Moy and Reeves2020), Brown and Mettler (Reference Brown and Mettler2023) for a few exceptions). Recognizing this disparity, it is imperative to investigate the extent to which the urban–rural gap in policy attitudes demonstrates stability over time and across various political contexts.

On the one hand, there are good reasons to expect rural populations to differ from their urban counterparts in policy priorities. Studies have shown that rural areas in the United States have historically had a disproportionate share of the country’s poverty population, and structural changes in the economy make rural areas even more vulnerable (Tickamyer and Duncan, Reference Tickamyer and Duncan1990; Lichter and McLaughlin, Reference Lichter and McLaughlin1995; Cramer, Reference Cramer2016). Highlighting the persistence of rural policy problems and their interconnectedness, Lichter and Schafft (Reference Lichter, Schafft, Brady and Burton2016, p. 334) note that “rural poverty reflects the lack of opportunities – good schools and stable jobs – that serve to concentrate poverty and reproduce it generation to generation.” Studies across decades point out considerable urban–rural gaps in various quality of life measures, often indicating that rural residents are in a disadvantaged position regarding material well-being and the receipt of institutional services, especially among minorities (Dillman and Tremblay, Reference Dillman and Tremblay1977; Burton et al., Reference Burton, Lichter, Baker and Eason2013; Thiede et al., Reference Thiede, Lichter and Slack2018).

Previous scholarship has also shown that rural inhabitants tend to have lower external political efficacy compared to their urban counterparts (García del Horno et al., Reference del Horno, Rubén and Hernández2023), and that local socioeconomic deprivation may lead to feelings of grievance or resentment, as well as diminishing political trust, due to perceived neglect of their geographic location (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Jennings and Stoker2021; Huijsmans, Reference Huijsmans2023). Based on participant observation, Walsh Reference Walsh(2012) showed that rural residents attribute local deprivation to political elites who are out of touch with rural lifestyles. These perceptions of bias may interact with subjective economic factors (e.g., unemployment) and quality of life indicators (e.g., access to medical care) to shape the policy priorities of rural populations in ways that differ from those of urbanites.

Free-text answers given to ANES surveys over the past few decades are quite informative in revealing urban–rural dynamics in policy attitudes. When asked about the most important problem (MIP) facing the country, a respondent in ANES 2020 mentioned education policy, highlighting “lack of completed lower and higher education throughout the country (primarily in rural America and among minority-based communities)” as the MIP. Another from ANES 1990 noted, “we have so many people at a poverty level; so many people are two checks away from being homeless. The performance level and achievement in the country has become so poor especially in the urban areas.” An ANES 1988 respondent stated: “I think the economy of all rural and small towns all over the U.S. is the single largest problem of the country.” Similarly, a respondent from ANES 1988 mentioned that “The economy in our parts of the country is not as good as it should be. The small towns are being hurt so much.” Some others pointed to broader issues that have polarized urban and rural voters, stating “Racial divide ... Rural white males have felt disenfranchised” (ANES 2016), and “urban voters condescending and rejecting rural America” (ANES 2020) as the MIP.

A contrary logic dictates that although place-based differences in socioeconomic background and lifestyles have a profound influence over how people form opinions about political outcomes and processes, such differences are usually absorbed by other politically salient divisions such as partisan affiliation and ideology (Lin and Lunz Trujillo, Reference Lin and Lunz Trujillo2023a). An early study by Knoke and Henry Reference Knoke and Henry(1977) predicted that the political behavior of rural and urban populations would gradually be indistinguishable as the rural electorate became more exposed to mass media and population interchange. Examining the evolving relationship between rural and urban areas in the United States, Lichter and Brown Reference Lichter and Brown(2011) argue that the traditional boundaries that separated rural and urban life have increasingly become blurred. Specifically, the authors highlight that structural changes in the economy, as well as increasing cultural and social exchanges between urban and rural areas in the country, reflect a complex interdependence (also see Irwin et al. Reference Irwin, Bell, Bockstael, Newburn, Partridge and JunJie(2009) for a similar argument).

Another line of scholarly work highlights the similarity with which different subgroups process elite and media cues. For instance, Jokinsky et al. Reference Jokinsky, Lipsmeyer, Philips, Williams and Whitten(2024) argue and show subgroups, especially partisan subgroups, respond to shifting conditions in similar and consistent ways. Challenging the arguments that use the growing significance of social and morality issues among rural populations as an explanation for the widening urban–rural gap in voting patterns, Bartels et al. Reference Bartels(2006) argue that economic issues still occupy the most central place in Americans, regardless of place-of-residence. As Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017 convincingly argue in their seminal book, partisan allegiances play a key role in shaping policy choices by the electorate. This line of scholarly inquiry suggests that partisan affiliation trumps other social identities in shaping policy attitudes (Dickson and Yildirim, Reference Dickson and Murat Yildirim2025), meaning that urban–rural gaps would be relatively small and primarily reflect partisan divisions. In a recent study, Lin and Lunz Trujillo Reference Lin and Lunz Trujillo(2023a) lend strong support to this idea and find that policy preferences are mostly partisan rather than place-based. Although we expect to find consistent urban–rural gaps in policy priorities, we also recognize the possibility of urban–rural gaps reflecting partisan divisions.

Hypothesis 1: There are urban–rural gaps in the prioritization of traditionally salient policy areas.

2.2. The role of contextual factors: state ideology and economic inequality

Studies show that rural and urban populations are hardly monolithic, and the economic and social structures within rural and urban areas vary greatly across both time and space e.g., Scala et al. (Reference Scala, Johnson and Rogers2015); Scala and Johnson (Reference Scala and Johnson2017). This implies that the nature of place effects may be subject to various contextual factors. In this research, we focus on two such factors that can help explain variation in urban–rural attitude gaps across space: local economic inequality and state policy liberalism.

The relationship between economic inequality and urban–rural gaps in various social and political phenomena has received considerable scholarly attention from distinct fields of research (Yang, Reference Yang1999; Hertz and Silva, Reference Hertz and Silva2020; Rodden, Reference Rodden2022). Especially after the election of Donald Trump in 2016, scholarly and journalistic accounts turned to economic explanations for the growing divide between rural and urban areas in political behavior (Orejel, Reference Orejel2017; Mettler and Brown, Reference Mettler and Brown2022). One potential mechanism here is that economic hardship may activate other grievances. As Bonomi et al. (Reference Bonomi, Gennaioli and Tabellini2021, p. 2375) argue, “economic losers become more socially and fiscally conservative,” and this, in turn, may further widen urban–rural differences in policy attitudes. Because economic inequality and poverty differentially impact rural and urban populations (Slack, Reference Slack2010; Young, Reference Young2013; Duncan, Reference Duncan2015; Binelli and Loveless, Reference Binelli and Loveless2016; Thiede et al., Reference Thiede, Butler, Brown and Jensen2020), changes in economic inequality levels may influence the extent of the urban–rural gap in policy priorities.Footnote 2

Hypothesis 2: The size of the urban–rural gap in policy priorities varies significantly across different levels of state economic inequality.

Another important contextual factor that potentially influences urban–rural divisions in policy attitudes is the local political context. The extent to which state policies align with conservative or liberal ideological principles may impact urban and rural populations in different ways, exacerbating place-based gaps in priorities. Decades of research building on the thermostatic model of policy responsiveness have demonstrated that public attitudes toward policies adjust in response to changes in those policies (Wlezien, Reference Wlezien1995; Pacheco, Reference Pacheco2013; Bendz, Reference Bendz2015). Because rural residents tend to differ from their urban counterparts in key policy areas that have become ideologically divisive, such as immigration and the allocation of government resources (Fennelly and Federico, Reference Fennelly and Federico2008; Lyons and Utych, Reference Lyons and Utych2023), shifts in state policy liberalism toward either end of the ideological spectrum should produce observable implications for place-based differences in policy priorities. In other words, major shifts in state policies may disproportionately affect urban or rural areas, which may contribute to place-based gaps in policy priorities.

Hypothesis 3: The size of the urban–rural gap in policy priorities varies significantly across different levels of state policy liberalism.

3. Data and methods

Our empirical analysis is based on a recently introduced dataset of Americans’ responses to the MIP question (Yildirim and Williams, Reference Yildirim and Williams2024). The dataset includes data from around 850 MIP surveys available at the Roper Center and codes open-ended responses to the MIP questions from nearly 1.1 million Americans spanning the period from 1939 to 2020 into 110 specific issue categories. The surveys were sponsored by various organizations such as Gallup, Los Angeles Times, CBS News, American National Election Studies, among others and were based on representative national samples. The dataset includes standard demographic and political variables, as well as state identifiers that are consistent across surveys. We merged the MIP dataset with yearly data on the ideological orientation of state policies i.e., policy liberalism; Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw(2016) and state-level income inequality (Frank, Reference Frank2014; Grossmann et al., Reference Grossmann, Jordan and McCrain2021).

We focus on place-based gaps in 12 broad issue areas, namely, budget deficit, agriculture, moral values, immigration, economy, tax, civil rights, crime, education, foreign policy, health, and drugs.Footnote 3 We created 12 dependent variables that measure whether the respondent’s MIP answer (i.e., at least one quasi-response within each answer) mentions the respective policy area. Because our dependent variables are of binary nature, we use logistic regressions. We employ ordinary logistic regressions to document the main effects, while relying on multilevel models to explore the interactive effects of place of residence and state-level factors, where observations (i.e., respondents) are nested within states. We report the summary statistics of key variables (Tables A1 and A2) in Appendix A. In the same appendix, we present various descriptive tables and figures regarding sample characteristics, including the distribution of respondents by year, urban/rural residence, partisan affiliation, and their intersections, as well as the contribution of different sources to the overall dataset (see Figures C1–C5).

Our main independent variable, urban residence, is a dummy variable that indicates whether the respondent lives in an urban area (vs. small town, rural area, and other nonurban and peripheral communities). Survey organizations determine the respondent’s community type by using predetermined administrative designations or urbanity codes. While the binary urban–rural categorization has been occasionally used by a few survey organizations, many have usually employed more detailed categories, such as metropolitan, large central city, central city, small town, farm, country, or other community. To ensure comparability across time and space, The Most Important Problem Dataset (MIPD) standardizes community type classifications by recoding various survey-specific categories into a binary variable. Respondents living outside cities and metropolitan areas are grouped into a single “rural or small town” category (coded 0), while all others are classified as urban (coded 1).Footnote 4

For analysis focusing on state-level variation in urban–rural gaps, we utilize two variables, the ideological orientation of state policies i.e., policy liberalism; Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw(2016) and state-level income inequality (Frank, Reference Frank2014; Grossmann et al., Reference Grossmann, Jordan and McCrain2021), both of which are continuous measures. Previous scholarship has shown that partisanship (Egan, Reference Egan2013; Eppet al., Reference Epp, Lovett and Baumgartner2014), income level (Gilens, Reference Gilens2009), age (Fullerton and Dixon, Reference Fullerton and Dixon2010), education level (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997), gender and race (Yildirim, Reference Yildirim2022) influence attitudes toward policies in important ways, and we control for these factors in our empirical models. The race variable is binary, indicating whether the respondent is White (coded as 0 for non-White respondents). The education variable has five categories and ranges from “no high school” to “post-graduate degree.” We also control for whether the state where the interview took place is in the South and whether the sitting president is affiliated with the Democratic Party. Due to the lack of income-level data in surveys prior to 1960, our main models focus on the period from 1960 to 2020. However, we also present models excluding the income variable, which cover the full time span from 1939 to 2020, in the Appendix.

Finally, while the dataset contains information about survey weights from many of the survey organizations, these weights are not comparable across time and space, and we are therefore unable to use them in our empirical models. To establish robustness of our main findings, we created survey weights using the U.S. Census dataset that consists of over 60 million individuals interviewed from 1940 to 2020. These base weights adjust for demographic factors to match the sample more closely with known population characteristics from Census data. To that end, we downloaded the Census data and generated categories of age groups, gender, race, and education level that correspond to the respective variables in our dataset. After merging the datasets, we estimated new models using survey weights. The results from these weighted models, which are presented in Appendix C, are remarkably similar to our original models.

Our empirical analysis proceeds as follows: First, we present a series of logistic regressions that predict the prioritization of 12 policy areas to identify any urban–rural gaps. Second, we explore the stability of urban–rural differences in policy priorities by illustrating how these differences vary over time. Third, we examine the extent to which urban–rural gaps in priorities (i) intersect with partisan divisions and (ii) vary across different economic and political contexts (i.e., economic inequality and state policy liberalism). To further explore partisan and geography-based gaps in policy priorities, we supplement our analysis with qualitative exploratory research using verbatim answers given to ANES surveys.

4. Results

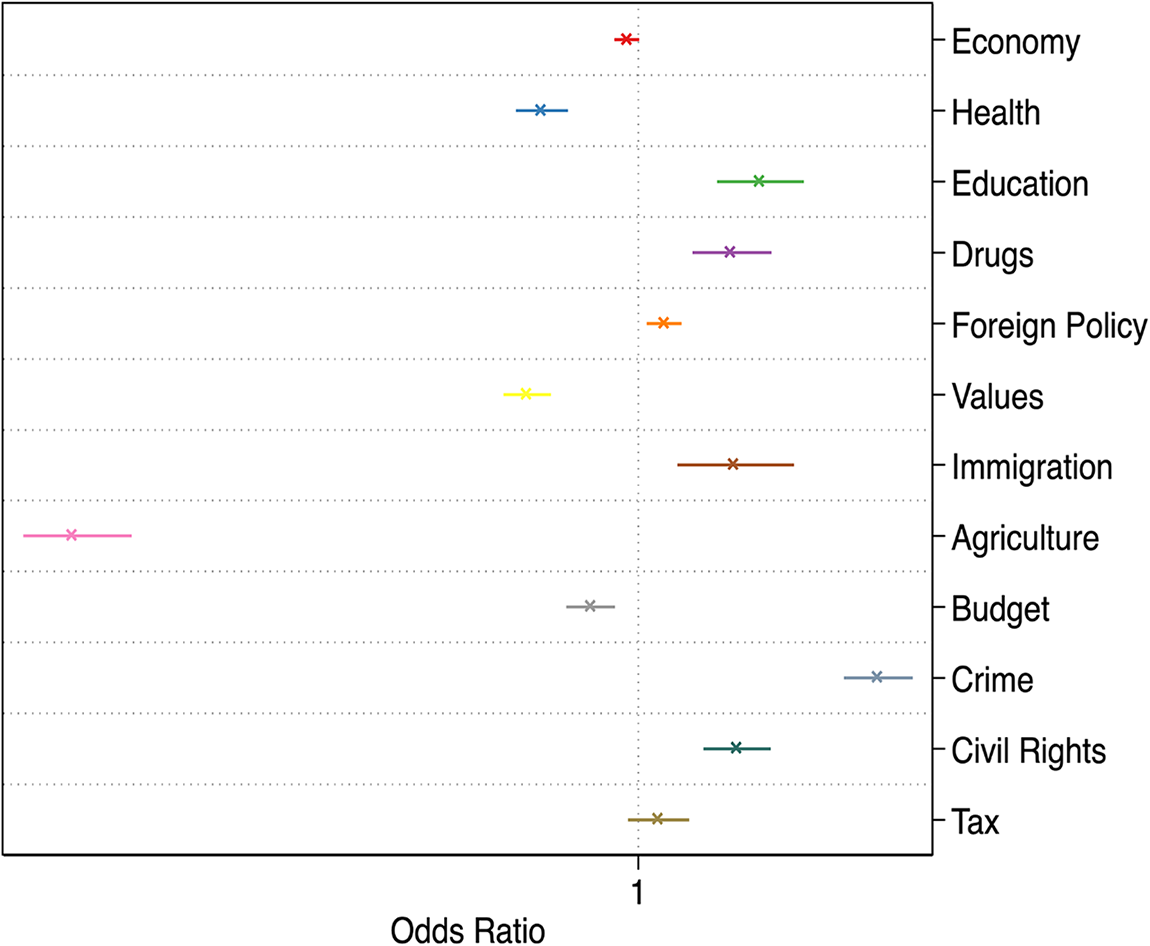

We begin our analysis by presenting odds ratios from 12 logistic regressions, one for each policy area, with year fixed-effects. In these models, we control for partisan affiliation, gender, age, race, formal education, income level, the political party of the sitting president, and the geographic region (i.e., the South). The odds ratios are reported in Figure 1. Note that the figure reports only the results for the variable urban for the sake of simplicity, illustrating urban–rural gaps in the prioritization of 12 policy areas. Odds ratios larger than 1 indicate urban–rural gaps favoring urban residents and vice versa. The figure clearly shows that urban populations differ from their rural counterparts in the prioritization of many of the traditionally salient policy areas. To be more specific, residents of rural and other peripheral communities are more likely than their urban counterparts to prioritize health care, moral values, agriculture, budget deficit, and issues related to the economy as the MIP facing the country, as indicated by the odds ratios that are smaller than 1. In contrast, urban residents seem to be more concerned about such issues as education, drugs, foreign policy, immigration, crime, and civil rights. While there are clear place-based gaps in policy priorities, it’s important to note that the effect sizes are modest. For example, the odds of mentioning education policy as the MIP are 14% higher for urban residents (![]() $e^{0.132} = 1.14$), while the odds of mentioning diminishing moral values are 13.5% lower (

$e^{0.132} = 1.14$), while the odds of mentioning diminishing moral values are 13.5% lower (![]() $e^{-0.143} = 0.8668$) for urban residents compared to their rural counterparts.

$e^{-0.143} = 0.8668$) for urban residents compared to their rural counterparts.

Our analysis so far has shown that urban and rural populations tend to differ in the prioritization of issues related to traditionally salient policy areas, although these place-based gaps are relatively modest. While useful, however, the above analysis does not provide a nuanced picture of the urban–rural divide in policy priorities. Most importantly, the pooled analysis presented in Figure 1 does not allow us to explore the stability and change of urban–rural gaps in policy priorities over time. Has rural identity always been an important predictor of policy priorities? To address this question, we examine the extent to which urban–rural gaps in priorities have varied over time in the following sections.

Figure 1. Urban–rural gaps in 12 issue categories.

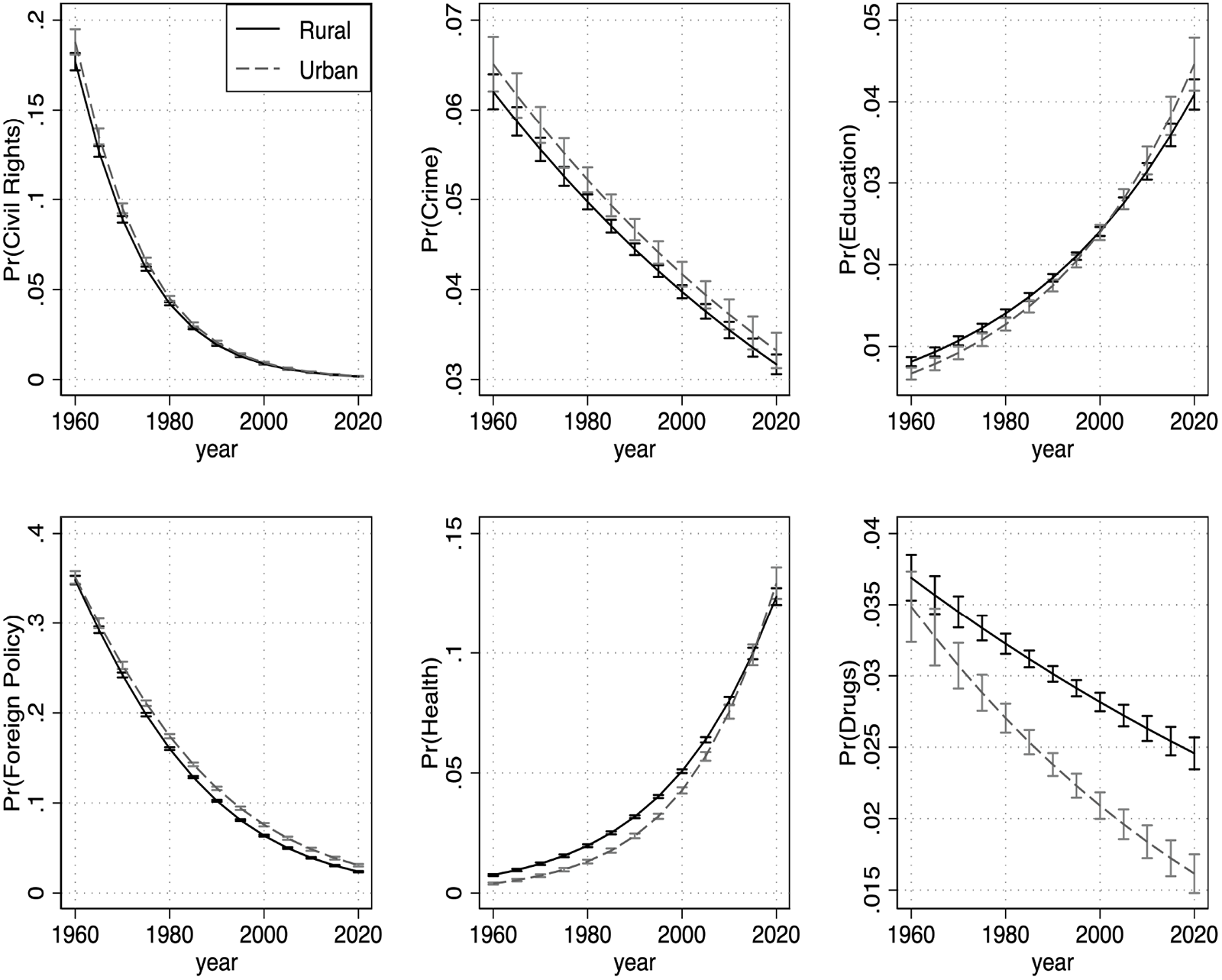

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the marginal effect of urban/rural residence on the prioritization of 12 policy areas over the period of 1960–2020 (see Tables C1 and C2 for full model specifications).Footnote 5 The figures show that urban–rural differences in many of the policy areas including budget deficit, immigration, taxes, civil rights, crime, education, foreign policy, and health have remained fairly stable across decades. Only in the prioritization of agriculture, moral values, drugs, and the economy has the urban–rural divide varied significantly over time. In the prioritization of drugs, and moral values, the gap broadened in favor of rural residents, while the gap has increased in favor urban residents in economic priorities. This aligns with the oft-cited argument that, over the past few decades, rural residents have become increasingly more concerned with morality issues at the expense of other important issues.

Figure 2. Urban–rural gaps in the prioritization of budget deficit, agriculture, moral values, immigration, the economy and tax across time, 1960–2020.

Figure 3. Urban–rural gaps in the prioritization of civil rights, crime, education, foreign policy, health, and drugs across time, 1960–2020.

Another important question is whether the state-level socioeconomic context, the ideological orientation of state policies, and the level of income inequality within the state shape urban–rural gaps in policy priorities. We argue that perceptions of the MIP facing the country among urban and rural populations may be significantly influenced by the economic conditions and the ideological orientation of policies in their respective states. To test this idea, we interact our main independent variable, urban–rural residence, with state-level income inequality (i.e., Gini) and policy liberalism and report marginal effects from multilevel logistic regressions in Figures B1–B3 (for income inequality) and Figures B4–B6 (for policy liberalism) in the online appendix.

The results clearly suggest that urban–rural gaps in priorities are remarkably resilient across varying sociopolitical contexts within the country. The urban–rural gap in priorities varies significantly only in issues related to moral values, taxation, and health policy. To give an example, rural residents living in states with high income inequality are significantly more likely to prioritize issues related to moral values as the MIP, compared to their urban counterparts. Conversely, the urban–rural gap in morality issues disappears in states where there is relatively low income inequality. Interestingly, the urban–rural gap in morality issues varies significantly also across the levels of policy liberalism. This shows that the prioritization of issues related to moral values among urban and rural residents is substantially influenced by contextual factors.

The urban–rural gap in the prioritization of the economy, agriculture, moral values, crime, foreign policy, and drugs diminishes as state-level policy liberalism increases. In health policy, the gap increases in favor of rural residents as state policy liberalism grows. Across most of the 12 policy areas examined in this analysis, the urban–rural gap in priorities remains relatively stable despite varying state-level economic and ideological conditions.

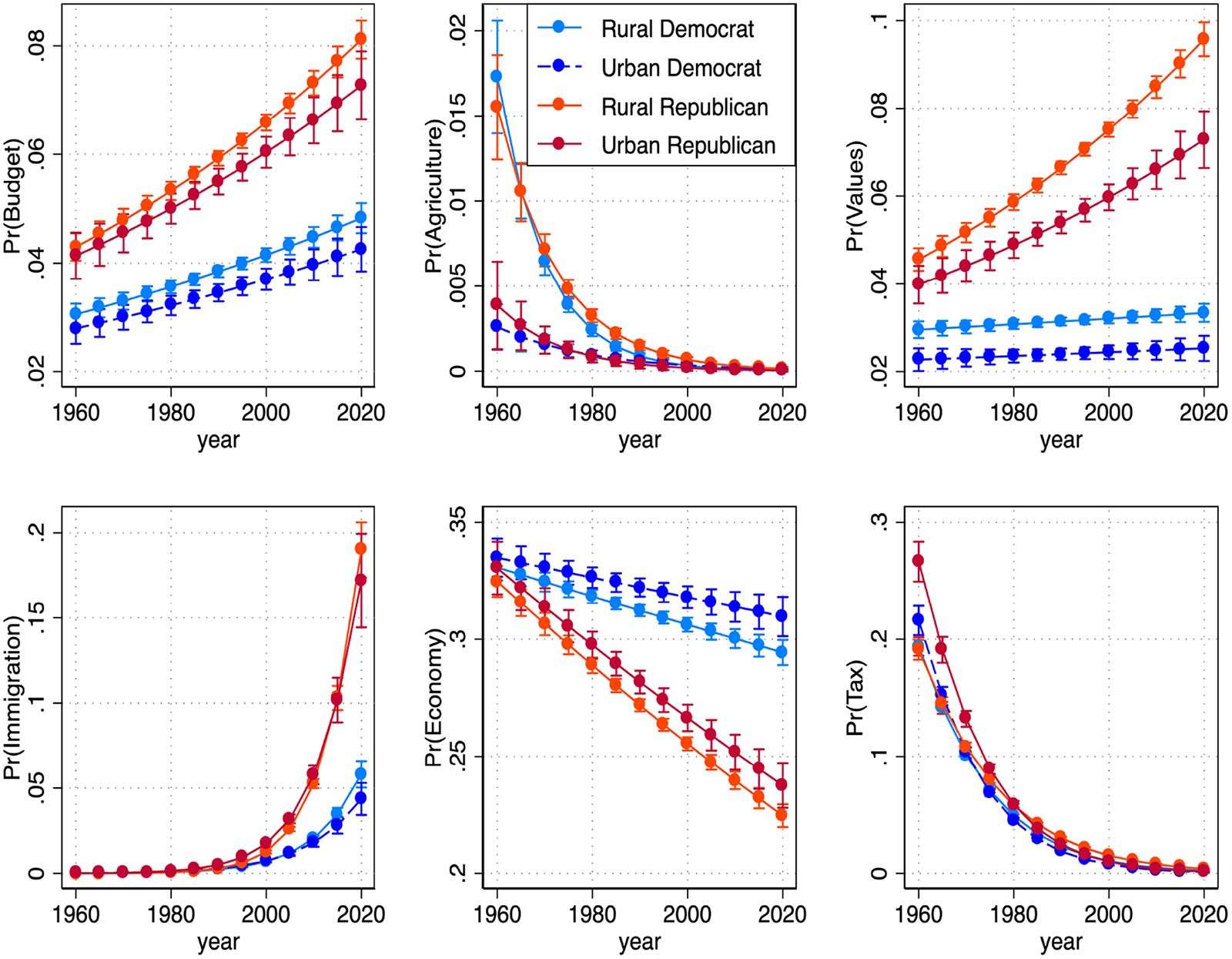

Next, we examine the extent to which the policy priorities of urban and rural populations are shaped by partisan actors. The fact that urban and rural policy priorities change predictably over time raises the possibility that residents in both areas respond similarly to external cues (e.g., elite and media influences). This also implies that citizens’ partisan identities may overshadow their place-based identities.Footnote 6 We explore this possibility in a set of new figures, Figures 4 and 5, which illustrate the interactive effects of partisan affiliation and urban–rural residence on the prioritization of 12 policy areas (see Table C3 and Table C4 for full model specifications). These figures allow us to investigate the extent to which co-partisans with different place of residence move in similar ways in the prioritization of problems.

Figure 4 demonstrates that the urban–rural gap within each partisan group is fairly small across all policy areas and that urban and rural co-partisans exhibit very similar policy prioritization behavior over time. Strikingly, in all policy areas documented in the figure, place-based gaps are overshadowed by partisan gaps. Another way to put it is that the policy priorities of co-partisans from urban and rural areas move in highly similar ways, indicating the role of partisan cues in shaping policy priorities. Only in issues related to moral values do rural Republicans differ considerably from their urban counterparts.

Figure 4. The interactive effects of partisan affiliation and urban–rural residence on the prioritization of budget deficit, agriculture, moral values, immigration, the economy and tax across time, 1960–2020.

On a separate note, the trend observed in issues related to agriculture is noteworthy, as their root causes likely highlight the dynamic nature of policy priorities influenced by structural changes. Both rural Democrats and Republicans were significantly more likely than their urban counterparts to prioritize issues related to agriculture until around the 1980s, after which the urban–rural gap disappeared.Footnote 7 This could be attributed to several factors. As rural populations shrank, attention to agricultural issues may have declined. Additionally, the gradual rise of cultural and morality issues in rural policy agendas may have led to a decline in the salience of issues related to agriculture in rural areas. Finally, since mentions of agriculture tend to involve government subsidies, the gradual diversification of the rural economy, coupled with the growing influence of deregulation and free-market ideals in the second half of the century, may have shifted focus away from agriculture as the MIP.

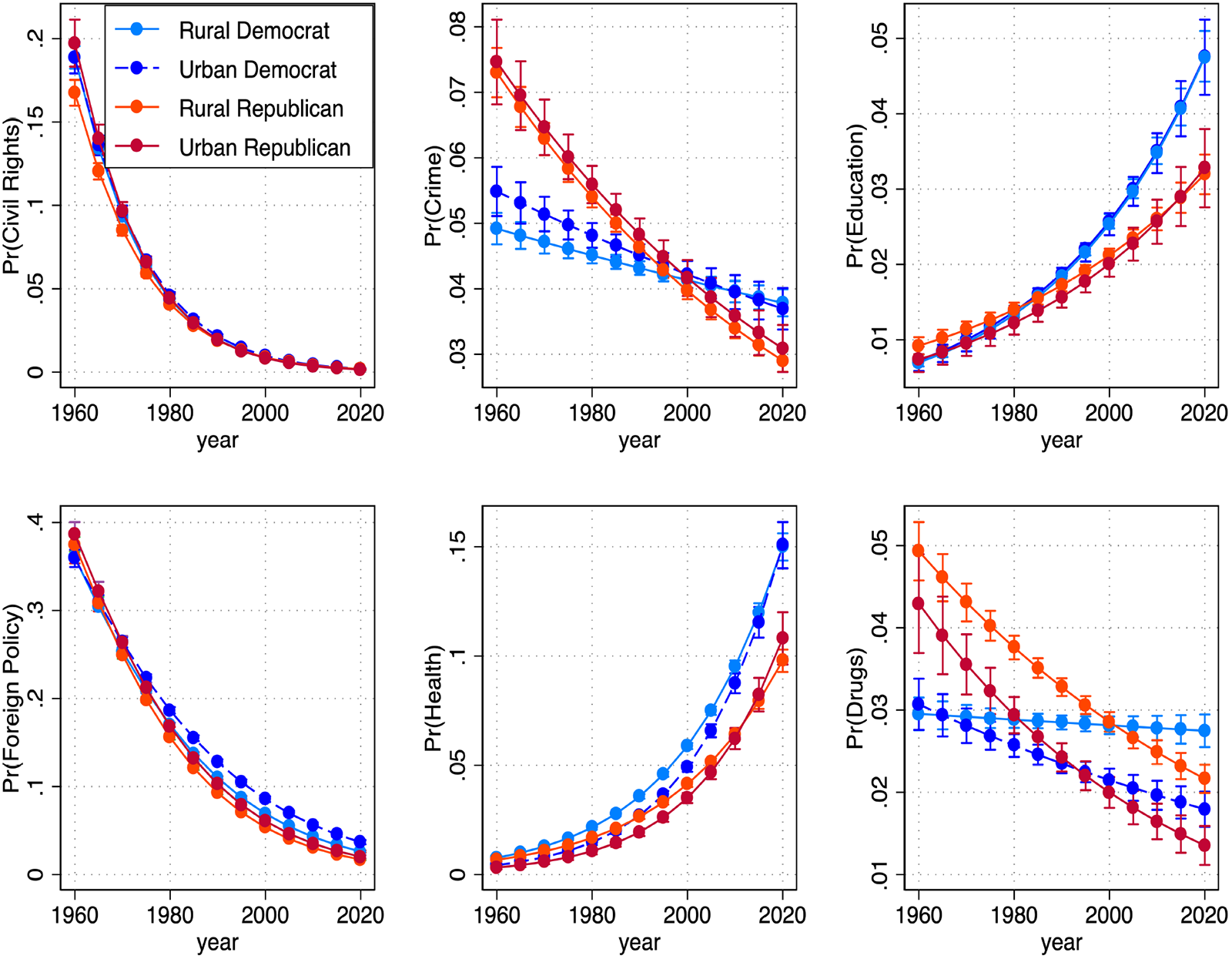

Figure 5 suggests that the results documented in the previous figure are not confined to a select few policy areas. The figure shows that partisan gaps in priorities overshadow urban–rural in most policy areas illustrated in the figure. Relative to Democrats, urban and rural Republicans were significantly more likely to prioritize crime as the MIP until around 1990s. The partisan gap in the prioritization of crime fluctuates considerably over time, whereas the urban–rural gaps both among Republicans and Democrats remain extremely stable. Except for the prioritization of drugs, which deviates from other policy areas by displaying high levels of heterogeneity, the main conclusion across all policy areas remains consistent. Overall, both Figures 4 and 5 indicate that the rural–urban identity seems to play a rather limited role in shaping policy priorities compared to partisan affiliation.

Figure 5. The interactive effects of partisan affiliation and urban–rural residence on the prioritization of civil rights, crime, education, foreign policy, health, and drugs across time, 1960–2020.

Our results strongly support recent findings by Lin and Lunz Trujillo Reference Lin and Lunz Trujillo(2023a). Similar to their study, we find that place-based gaps in policy opinions are significantly smaller than partisan gaps. Additionally, our study aligns with theirs in examining partisan differences within urban and rural areas. For example, Lin and Lunz Trujillo Reference Lin and Lunz Trujillo(2023a) find that rural Democrats show greater agreement with policies such as allowing refugees to come to the United States and permitting transgender people to serve in the military. According to their study, there are consistent, albeit minimal, partisan gaps within both urban and rural areas. Similarly, our study shows that urban Democrats and urban Republicans differ from their nonurban counterparts in the prioritization of issues related to moral values, the economy, drugs, and government spending. Especially in issues related to moral values, partisan gaps are stable over time, with rural partisans gradually attaching more importance to issues related to moral values compared to their urban counterparts. This aligns with past scholarship that documents growing conservatism in rural areas.

4.1. Additional analysis

4.1.1. A qualitative exploration of ANES verbatim answers

Figure 3 in the previous section showed that the prioritization of drugs as the MIP has been decreasing since 1960, with the gap between urban and rural voters increasing in favor of rural voters. Figure 5 showed that while both urban and rural Republicans have grown less concerned with issues related to drugs over time, this decline is less pronounced among urban Democrats and absent among rural Democrats. This implies that the stronger emphasis on drugs as the MIP in rural areas and small towns, as illustrated in Figure 5, is driven partly by persistent issue salience among rural Democrats.

One potential explanation for continued prioritization of drugs as the MIP among Democrats, especially those living outside urban areas, might concern partisan differences in key attributes associated with drugs. Democrats may be more likely than Republicans to associate drug issues with broader concerns about welfare and health-care access, rehabilitation, youth, and mental health support. The persistent lack of these services in rural areas could explain why drugs occupied a relatively larger space in the policy agenda of rural Democrats. Moreover, as seen in the three-way interactions, the patterns in the prioritization of drugs closely mirror those in the prioritization of crime as the MIP, particularly among Republicans. While Republicans may have shifted focus from drugs, regarding which they tend to adopt a more punitive and short-term stance, to other “morality issues” like abortion and immigration, Democrats, particularly those from rural areas, may have placed a greater emphasis on the role of drugs in various social problems, in particular problems related to structural issues such as maintaining social cohesion and community stability.

Although we are not prepared to systematically address these possibilities, free-text answers from ANES surveys might provide some cues. Here we present a glimpse of verbatim answers from ANES surveys related to drugs issues among respondents who identified as strong partisans, starting with strong Democrats. A rural respondent from ANES 1990 stated, “The drugs and gangs – if they stop the drugs, they’ll stop a lot of other problems.” Another rural respondent said “The drugs [are the most important problem] because that leads to all other problems particularly the welfare problems and the crime” (1996). Another rural Democrat said that “The drug situation, that is causing all the problems–stealing and murder. It’s affecting their minds, teenagers. When they get old, they won’t be able to run the country” (1988).

In contrast, both urban and rural Republicans appeared to be far more concerned with the moral dimension of drug problems, where drug-related mentions often included issues related to illegal immigrants, AIDS, homosexuality, youth disrespect, and lack of moral values. A strong Republican who did not report his or her place of residence stated: “morality, I feel our morality in the U.S. has fallen about as low as it can get what with drugs, sex, abortion and foul language” (2012). A respondent mentioned “Influx of illegal drugs disruptive of social fabric” (1986) as the MIP, whereas another Republican stated “morality, sex, drugs, and music, families breaking apart” (1996). A respondent from the 2012 ANES survey said “The drugs, alcohol and a lack of respect in the younger generation. Drugs and alcohol are too available to young people. The punishment should be more and dealt with by people who have proven themselves not to be users and uphold the laws. Not be wishy-washy.”

4.1.2. Disentangling the prioritization of moral values

As documented in the previous sections, both urban and rural Republicans, unlike their Democrat counterparts, have gradually become more concerned with issues related to moral values. Morality issues have occupied significant space particularly in the policy agenda of rural Republicans in the past few decades. Although useful, the above analysis did not provide a nuanced picture of the urban–rural gap in morality issues. Information on which aspect of morality issues the respondent prioritized is available in our dataset, based on which we seek to provide additional insight. Relying on the same model specifications used above, we estimated new models that predicted the prioritization of four frequently mentioned subcategories of morality issues: “morals and values,” “family values,” “lack of religion,” and “abortion.”

Marginal effects obtained from these models are illustrated in Figure C3. The analysis suggests that in morality issues rural Democrats differ from rural and urban Republicans in important ways. Unlike their Republican counterparts, the prioritization of morals, family values, and abortion among rural Democrats has been mostly steady over the past 60 years. While rural Democrats and rural Republicans showed similar levels of concern for issues related to religion and religious values in the 1960s, they have since moved in opposite directions. Interestingly, over time, rural Democrats have become increasingly similar to their urban counterparts in religious values and concerns. In all four categories of moral values examined here, the concerns of rural Republicans have grown considerably over the past decades.

To further explore these patterns, we draw briefly on George Lakoff’s framework of moral worldviews—specifically his distinction between the “strict father” and “nurturant parent” models (Lakoff, Reference Lakoff2008, p. 81)—to shed light on the different ways rural partisans may interpret similar policy issues. While not central to our theoretical framework, this lens helps clarify why rural Democrats are more likely to frame concerns about drugs in terms of harm to youth and community health, whereas rural Republicans often emphasize individual responsibility, punishment, and moral decline. Though exploratory, this contrast is consistent with Lakoff’s broader argument that liberals and conservatives are guided by distinct moral metaphors that shape how they define and prioritize social problems.

5. Discussion

The outcomes of both the 2016 and 2024 U.S. presidential elections underscore the continuing salience of urban–rural political divides in American politics. Although our analysis predates the 2024 election, the patterns we document here—particularly in how rural partisans articulate policy priorities and moral concerns—remain relevant for understanding the enduring role of place in shaping political behavior. These recent developments have sparked renewed scholarly interest in how rural identities contribute to broader political outcomes such as democratic dissatisfaction, declining institutional trust, and support for populist movements.

To advance our understanding of how urban–rural divides shape these macro- and micro-level trends, a growing body of research has emphasized the influence of place-based identities on opinion and attitude formation. One well-established insight from this literature is that rural populations differ from their urban counterparts in policy preferences—a distinction that carries important implications for political participation and representation. In this study, we contribute to this literature by shifting the focus from policy preferences to policy priorities, arguing that overlooking urban–rural differences in priorities limits our understanding of how these divides structure political attitudes.

Our results based on MIP surveys indicate that although there are modest but consistent urban–rural gaps in policy priorities, the urban–rural divide is overshadowed by the partisan divide in priorities. This is strongly aligned with findings documented in recent scholarship (see Lin and Lunz Trujillo Reference Lin and Lunz Trujillo(2023a)). In most policy areas analyzed in this study, the urban–rural gap varied only marginally over time and across space. This is indicative of the major role that partisan affiliation plays in shaping policy priorities. The policy agendas of urban and rural residents seem to respond to elite cues in highly similar ways, which helps explain the similar prioritization patterns among co-partisans from urban and rural areas. Overall, our results suggest that despite the growing partisan cleavage between rural and urban areas, the policy priorities of rural populations are not inherently distinct from those of urban populations.

The fact that urban–rural gaps in priorities mirror partisan gaps, to a certain extent, should be welcomed as good news for the representation of “rural” interests. We argue that the policy congruence between urban and rural co-partisans works to the advantage of political representation as it ensures that place-based interests are effectively represented within democratic processes. The parallel trends in urban and rural priorities supports the idea that citizens, irrespective of their urban–rural identities, respond to partisan cues when forming opinions about the pressing problems facing the country. If the policy priorities of rural partisans differ considerably from those of their urban counterparts, representatives would be under pressure to carefully balance and address the competing interests of both urban and rural co-partisans, which is often impractical. In other words, the policy congruence between urban and rural co-partisans likely contributes to democratic representation by helping integrate rural interests into the broader partisan landscape.

Our study has several limitations that warrant consideration. Most importantly, by focusing on issue priorities, we disregard qualitative differences in priorities. While there may be relatively little room for variation in the sources of mentions related to topics such as the economy, crime, drugs, taxes, and immigration, it is entirely possible that rural and urban co-partisans had different aspects of foreign policy or moral values, for example, in mind when citing these as the MIPs facing the country. Our additional analyses based on ANES verbatim responses and the subcategories of morality issues lend support to this idea. Moreover, we were unable to examine various other important explanatory factors that could help explain urban–rural gaps in priorities due to the lack of standardized variables in the dataset. As an example, Lunz Trujillo Reference Lunz Trujillo(2024) points out that there are non-rural individuals who identify with rural values and norms, having been socialized in a rural area or simply feeling an affinity for rural life despite currently living in an urban area. In the absence of more fine-grained data, this study is not prepared to examine how rural identifiers living in urban areas (and vice versa) influence the documented urban–rural gaps. Future research on place-based gaps in priorities should delve into these weaknesses.

Nemerever and Rogers Reference Nemerever and Rogers(2021) highlight that the literature on place-based gaps has relied on varying concepts and measures of rural and urban identities, and that geographic units of aggregation, which tend to overlook social and economic heterogeneity within areas, may lead to measurement error. As an illustrative example, the authors note that remote nonurban areas, such as those in San Diego, are often classified as “urban” for practical purposes, despite showing partisan similarities with traditionally rural areas. While our theoretical arguments are based primarily on the center-periphery cleavage between residents of urban and nonurban areas, rather than on rural consciousness or lifestyle-driven place-based gaps, our study is still subject to some of the issues highlighted by Nemerever and Rogers Reference Nemerever and Rogers(2021). In particular, the use of broad urban and rural categories drawn from nearly 850 surveys potentially masks significant heterogeneity within geographic areas. This constitutes an important weakness of our study.

Finally, a note on the external validity of our findings is warranted. While this study makes a comprehensive attempt at furthering our understanding of place-based gaps in policy priorities, it is based on a single-country case. The fact that partisan gaps outweigh place-based gaps in policy priorities underscores the role of elite cues in shaping policy agendas. This implies that political institutions and electoral systems may play an important role in shaping urban–rural gaps. In electorally more permissive political systems, especially those with agrarian political parties, urban–rural gaps in policy priorities may be relatively more visible. The extent to which how findings from a polarized two-party system travel to multiparty, consensus democracies await future research. Future research focusing on place-based gaps in a comparative fashion might prove useful in furthering our understanding of generalizability of empirical findings regarding geographic disparities in policy priorities.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.33. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WM7HDH.

Acknowledgements

We thank three anonymous reviewers and the editor for their detailed feedback. We are also grateful for comments from Olivier Godechot, Emiliano Grossman, Catarina Leão, Ulysse Lojkine, Lawrence McKay, Allison Rovny, Christine Sylvester, and Noam Titelman, as well as feedback from attendees at the 2024 Annual Meeting of the Political Studies Association (Glasgow) and the 2024 joint AxPo/CEVIPOF seminar at Sciences Po (Paris).