Introduction

Civil society organizations (CSOs)Footnote 1 in India face a Hindu majoritarian state that uses a range of regulations and extra-legal practices to limit dissent and the freedom of faith-based organizations (FBOs) and other civic actors (Arora Reference Arora2020; Chacko Reference Chacko2018; Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2018; Deo et al. Reference Deo, Hilhorst and Ganguly2019). The previous United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, led by the Indian National Congress from 2004 until 2014, introduced new regulations for CSOs regarding accounting practices, permissions needed to access foreign funding, corporate social responsibility (CSR) collaborations, and also used intelligence agencies to investigate activists. These regulations and practices have been adapted and expanded by the subsequent governments led by the religious majoritarian Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), under Prime Minister Narendra Modi since 2014, in ways that stifle dissent and limit religious freedom. This article explores how FBOs rooted in different religious traditions experience the state’s changing regulation of civic space differently. We will show that, in response to the narrowing civic space by a religious nationalist government, FBOs adopt similar rhetorical strategies to protect themselves, but they relate to the state quite differently depending on the particular history of their faith community.

In so doing, we engage with an important knowledge gap. The literature on FBOs in development is limited in size and scope. According to Erin Wilson, the development sector’s policymaking and its academic knowledge-making have a secularist bias, in that practitioners and scholars tend to see development as part of a modernization process, and religion and religiously driven organizations as marginal to it (Reference Wilson2023). This has started to shift in the past two decades as there is a new willingness to engage with religious actors, identities, and narratives in the development space (Smith Reference Smith2017). Most development sector actors engage with religion, including FBOs, by using FBO grassroots networks in a purely instrumental way (Kidwai Reference Kidwai, Mavelli and EK2016). Gradually, however, scholarship is adopting a more critical approach in which frameworks for engaging with the values and goals of religious practitioners are taken more seriously (Deneulin and Zampini-Davies Reference Deneulin and Zampini-Davies2017). While scholarship on development CSOs is catching up with these shifts, significant gaps remain. Wilson calls for more contextually grounded, intersectional, and specific approaches to studying religion in world politics. Others point out the dearth of literature on FBOs in development (Brass et al. Reference Brass, Longhofer, Robinson and Schnable2018). Our paper addresses the way FBOs in India relate to the questions of constricting civic space that face them—a condition faced by many FBOs around the world. This is specifically important given that the literature on constricting and changing civic space has not at all addressed the question of its implications for FBOs. We seek to understand how development organizations from five faith traditions navigate constricting and changing civic space as defined for them by the majoritarian government, thus providing a context-specific, intersectional, and specified approach to studying religion and politics.

Civic space and FBOs

In recent years, many states have restricted the space for civil society to carry out its roles—especially political ones (CIVICUS 2020; Dupuy et al. Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2016; Hossain et al. Reference Hossain, Khurana, Mohmand, Nazneen, Oosterom, Roberts, Santos, Shankland and Schröder2018; Rutzen Reference Rutzen2015; Toepler et al. Reference Toepler, Zimmer, Fröhlich and Obuch2020). These restrictions are structural, with states deliberately and systematically undermining civic space (Buyse Reference Buyse2018). Van der Borgh and Terwindt (Reference Van der Borgh and Terwindt2012), integrating existing research, distinguish five sets of actions and policies that restrict operational space for CSOs: physical harassment and intimidation; preventive and punitive measures; administrative restrictions; stigmatization and negative labeling; and pressure in institutionalized forms of interaction and dialogue between government entities and civil society, distinguishing between co-optation or closure of newly created spaces. Empirical literature shows these strategies being implemented in many regimes or permitted by them as restrictive actions are carried out by non-state actors such as vigilante groups. Some work has been done on the ways authoritarian regimes regulate religion that coincides with our finding about the disparate impact these regulations have on FBOs belonging to different faith traditions (Reardon Reference Reardon2019a, Reference Reardon2019b).

However, civic space does not shrink for all civil society actors to the same degree or in the same way. Constraints on civic space are also often selective, with new restrictions mostly affecting human rights defenders, social movements, and marginalized and disempowered groups (Hossain et al. Reference Hossain, Khurana, Mohmand, Nazneen, Oosterom, Roberts, Santos, Shankland and Schröder2018, 7–8, 14). Some scholars also argue that civic space should be seen as changing or shifting rather than shrinking, since governments may constrict some CSOs while enlarging the space for others, for example in collaborations or in roles legitimating the regime ideologically (see e.g. Skokova et al. Reference Skokova, Pape and Krasnopolskaya2018; Toepler et al. Reference Toepler, Zimmer, Fröhlich and Obuch2020).

The literature on constricting and “changing” civic space shows little attention to FBOs. Some publications show how certain FBOs are singled out, as with Muslim CSOs in various countries (Howell Reference Howell2014). However, publications explicitly meant to survey the nature and implications of states’ policies regarding civic space are generally almost or totally silent on policies regarding FBOs or how policies regarding FBOs based on different faiths may be different or similar (see e.g. Hossain et al. Reference Hossain, Khurana, Mohmand, Nazneen, Oosterom, Roberts, Santos, Shankland and Schröder2018; CIVICUS 2020; Dupuy et al. Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2016; Rutzen Reference Rutzen2015).

This lack of attention is surprising for two reasons. First, FBOs are a widespread category of CSOs, with organizations rooted in diverse faiths active in many countries around the world, and they profess or work from distinct values that may not be in line with authoritarian and hybrid regimes seeking to manage or constrain civic space for CSOs. This makes at least some FBOs a likely target for constriction, with important implications for their operations (Tam and Hasmath Reference Tam and Hasmath2015). Second, at least a subset of FBOs engages with minority interests, perspectives, or identities. They may be grounded in minority faiths, and in many contexts, these faiths face discrimination. FBOs may seek to represent and/or protect members of their faith community and others based on principles of freedom of religion or rights more generally (Bauman and Ponniah Reference Bauman and Ponniah2017). With this, at least some FBOs in a country may easily find themselves in a position where they may oppose regimes, are silenced, or self-censor, thereby working against their principles and mission. In this paper, we therefore address the following research question: How does the religious nationalist state, which seeks to reshape and repress civil society from its ideological basis, affect FBOs in heterogeneous ways? We show that FBOs in India adapt to political constraints in common ways, while those belonging to different faith traditions additionally respond to specific pressures. We do this through an interview-based comparative empirical study of thirty-four FBOs in India from five faith traditions active in fifteen states.

Below, we first discuss the context of India and its faith traditions, continuing with a theoretical discussion of civic space, religious nationalism, and India’s Hindu majoritarian government. We then describe our research methods, after which the findings of the study are presented, followed by a conclusion.

Indian context

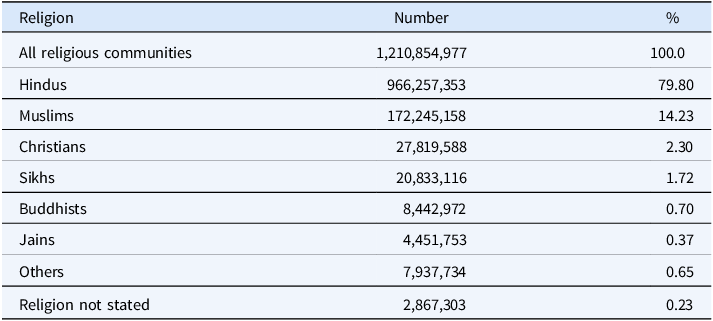

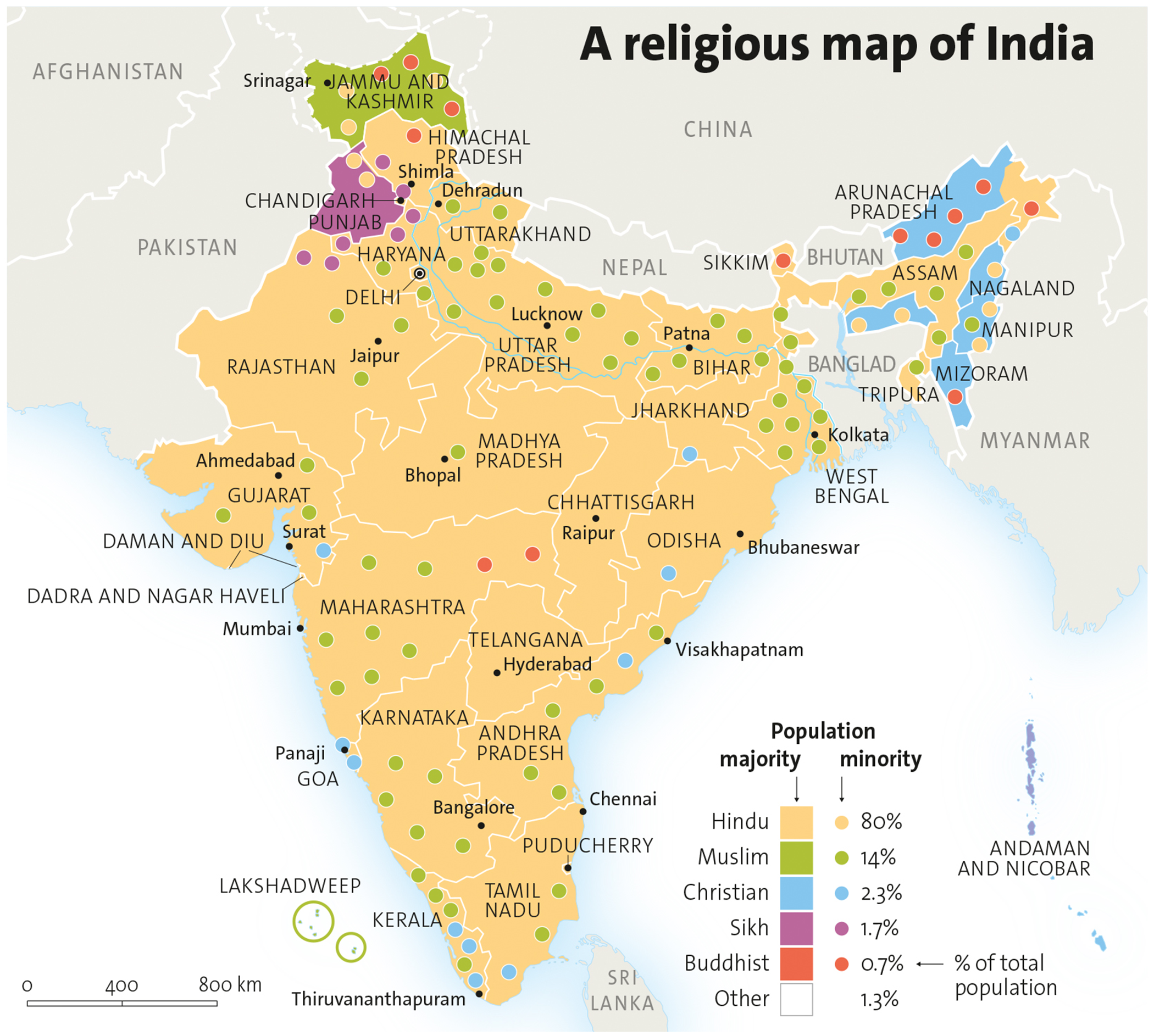

India is both a deeply religious society and one that is home to a remarkable diversity of faith traditions and religious practices as seen in Table 1 and Figure 1. The largest category, Hindus (80.5%), is itself a category that papers over a remarkable diversity (Verghese Reference Verghese2020). Hindus can be atheists, monists, and/or polytheists. They may be SavarnaFootnote 2 Hindus whose practice is defined by caste identity, and they may be DalitsFootnote 3 who continue to self-identify as Hindus while rejecting caste. Hindus may be Shaivite or VaishnaviteFootnote 4 ; devotees of one or many Gods and Goddesses. They may follow a particular guru (spiritual mentor) or practice tantric (rituals based on ancient Hindu or Buddhist scriptures) rituals or study Sanskrit texts. Their worship may involve pilgrimage or regular visits to a temple or prayer at an altar in their homes. The practice and theologies of Hinduism are diverse and vary according to region and caste in a way that makes the category of Hindu more of a meta-category than one with a robust sense of groupness. In fact, it takes a lot of work to produce a self-understanding as Hindu and then to translate it into a political category (Williams and Deo Reference Williams, Deo and Hua2018). Hindutva as the ideology of the government attempts to encompass most varieties of Hindu practice. However, it tends to favor rituals and beliefs that center on the North Indian worship of Ram and Sita (Rajagopal Reference Rajagopal2001), a focus on religious precepts that emphasize social order over more mystical forms (Sharma Reference Sharma2002), and cultural practices that promote public demonstrations of faith (Hansen Reference Hansen1999).

Table 1. Religious diversity in India (2011)

Data Source : Religion, Census of India 2011 https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/11361 Accessed Feb 2, 2024 (This is the most recent census)

Figure 1. A religious map of India.

Source: Marin, Reference Marin2019, available at: https://mondediplo.com/maps/india-religion

India is also home to the 3rd largest Muslim population in the world, after Indonesia and Pakistan (Desilver and Masci Reference Desilver and Masci2017). Muslims in India are internally divided into caste-like Ashraf, Ajlaf, and Arzal communities. Ashrafs are the most privileged and generally are the descendants of Arabs or upper caste Hindu converts; Ajlaf are the “backward” Muslims and are local converts from lower caste Hindus; and Arzal are Dalit Muslims. Furthermore, there are sectarian divisions among Sunnis, Shias, Bohras, Khoja, Ismailis, and Ahmadis among others. While readers are likely familiar with Sunni and Shia differences, we offer a little context for the others. Bohras, Khoja, and Ismailis are sub-sects of Shia Islam. Ahmadis follow most of the tenets of Islam but believe that the promised savior has already arrived and established the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community in 1889, while other Muslims are still waiting for a savior to come. Their geographic distribution in a first-past-the-post electoral system means that there is no significant Muslim political party in India, and Muslims generally must vote for non-Muslim representatives (Devasher Reference Devasher2020).

Christian communities in India include those communities who adopted Christianity in the first century and more recent converts to Protestant and Pentecostal traditions. They are as dispersed as Muslims are, with some significant concentrations in the states of Kerala, Goa, and Nagaland, where they can act with some political cohesion (Marin Reference Marin2019).

The Sikh community is largely concentrated in the state of Punjab, which was created in response to mobilization by Sikhs, leading to the separation of Punjab and Hindu majority Haryana in 1966. The Sikh community has its own internal divisions along lines of caste, despite Sikhism having anti-caste sentiment as a core tenet (Hans Reference Hans, Ramnarayan and Satyanarayana2016). The Khalistan movement is a separatist movement pursuing the creation of a homeland for Sikhs by establishing an ethno-religious sovereign state called Khalistan in the Punjab region of India. The movement was brutally suppressed by the Indian state in the 1980s (Jetly Reference Jetly2008). The conflict periodically resurfaces, as shown by the recent arrest of Amritpal Singh—a pro-Khalistan activist (Sehgal Reference Sehgal2023). The overrepresentation of the community in the armed forces is both a means to integrate it into the national imagination and a source of tension (Kundu Reference Kundu1994).

The last religious group our study includes are Buddhists, the majority of whom descend from Dalits whose families converted from Hinduism to Buddhism (Burke Reference Burke2021). These Buddhists are politically active—their conversion was prompted by Dr. Ambedkar, the author of the Indian constitution and the leader who inspired the Dalit Buddhist movement. Ambedkar’s motto was “educate, organize, agitate,” and as we show in the paper, their organizations are the ones most willing to adopt a confrontational stance towards the current government.

A saffron government

Religious nationalism was the subject of many debates in the 1990s and 2000s as the ideological rivalry between communism and capitalism faded from world politics. Scholars tried to explain the seeming upsurge in ethnic, religious, and nationalist identities and conflict leading to a new literature on identity and politics (Huntington Reference Huntington2011; Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Fearon and Laitin Reference Fearon and Laitin2003). As we study the relationship between religion and nationalism, we find that it varies greatly based on historical context. National identities are stronger in some societies, while religion shapes social identity, or reinforces and is incorporated into nationalism in others (Casanova Reference Casanova2006; Greenfeld Reference Greenfeld1996). In India, Hindu nationalism has been one of several versions of Indian nationalism, and one that has risen to prominence in recent decades, led by what is known as the Sangh Parivar, a constellation of Hindu nationalist organizations, including the BJP as its political wing. In India, the view that the country is a Hindu homeland is inextricably linked with the view that non-Hindus, particularly Muslims and Christians, are outsiders because their holy lands of Mecca and Jerusalem are not in India’s borders. This means that religious minorities are regarded with suspicion, and violations of their civil and political rights may be justified as upholding the state’s security. A recent instance of such developments has been the abrogation of the protected status of Muslim-majority Kashmir, abolishing Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which granted Kashmir the autonomy of internal administration, allowing it to make its own laws in all matters except finance, defense, foreign affairs, and communication. Another recent instance has been the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA), which amended the Citizenship Act of 1955, providing an accelerated pathway to Indian citizenship for persecuted religious minorities from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan who are Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists, or Parsis who arrived in India before the end of December 2014. The law does not grant such eligibility to Muslims or Christians from these countries. The act has been criticized as constituting the first time that religion in India had been explicitly used as a criterion for citizenship under Indian law. Additional manifestations of the Hindu Nationalist movement’s ideology as practiced by the BJP government include the impunity offered to Hindu vigilantes and the orchestration of everyday majoritarian violence by the state and by the public (Basu Reference Basu, Hansen and Roy2022).

Ideological developments also impact civil society. Since the BJP came to power in 2014, leading a coalition titled the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), it has expanded the state’s use of tools for surveillance, regulation, and investigation to target a range of CSOs, especially those seen as critical of the state (Mukherji and Shrivastava Reference Mukherji and Shrivastava2024). It is important to note that there is not a sharp break in the policies of the state before and after the election of the BJP in 2014. Many of the forms of civic space restriction discussed by our interviewees were present even before that election and are driven by non-state actors aligned with the Modi government. Criticism of policies and exclusionary actions (and inactions) of the state have been the catalyst for investigation and suspension of registration of many organizations including Greenpeace and Amnesty International, and punitive action against activists. CSOs challenging the state are commonly delegitimized as “anti-national” (Chacko Reference Chacko2018) and academic freedom and freedom of the press are restricted for “security” reasons (Chakrabarti Reference Chakrabarti2018). The Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) laws, governing which organizations can receive donations from foreign organizations and individuals, are an important tool in favoring or disfavoring CSOs. Although first introduced in the 1970s, recent revisions to the rules have required CSOs to seek frequent renewals of their licenses, tightened accounting requirements, and introduced new restrictions on the activities the funds can be used for (Agarwal Reference Agarwal2022).

Much of our discussion of the religious nationalist state refers to the central (federal) government. However, FBOs also interact with state governments. Currently, 17 of the 31 state governments in India are governed by the BJP or its NDA coalition; thus, the sub-national variation that is often a hallmark of a federal system like India is becoming less and less significant. Finally, FBOs also work with local governments at the village and municipal level, and in theory, these bodies are not partisan. We observed that the rising power of Hindu nationalism at the state and central level over the past two decades has created a diffuse sense of being under surveillance and subject to intrusive regulation and repression by FBOs all over the country.

In seeking to explain how a religious nationalist state reshapes and constrains FBOs, we might hypothesize that it constrains CSOs equally, without distinction between religious and secular organizations. However, given the role that religious chauvinism plays in religious nationalist ideology, we may expect that the religious nationalist government will favor FBOs if they belong to the same faith tradition as itself while discriminating against those who are associated with any other religious tradition. To understand how this may play out in India at present, we need to first address the meanings of secularism in India. The Indian experience with secularism can be described as having two major streams (Bhargava Reference Bhargava2010). The first is the Nehruvian ideal of secularism, in which the state embraces religious diversity and seeks to maintain equidistance from all traditions. Unlike the French model of sharp separation to protect the state from the church or the American view of separation to protect the church from the state, the challenge in this Indian secularism is to treat all religious groups equally, which requires state entanglement with religion to advance equality (Deo Reference Deo2016). This mode of Indian secularism was ideologically dominant under the Congress Party and UPA governments. It is important to note that the opposite of “secular” is communal in India. To be communal is to promote the well-being of one’s own group at the expense of all other Indians. It is seen as chauvinistic and potentially violent (Upadhyay and Robinson Reference Upadhyay and Robinson2012).

The second version of Indian secularism has a Hindu nationalist foundation. The ruling BJP’s Hindutva ideology conceives of India as a nation rooted primarily in Hindu tradition, with followers of other faiths required to acknowledge its hegemony. It constructs Hindus as secular regardless of what they do, because of Hinduism’s tolerance of spiritual diversity, with “Hindu” connoting an “Indian” way of life rather than a religion (Saxena Reference Saxena2018). Non-Hindus are potentially “communal,” also regardless of what they do, because their religious and nationalist loyalties are suspected of being in conflict with each other. While the advocates of Hindutva call the equidistant secularism of the Congress pseudo-secularism because it acknowledges religious diversity, they seek to advance a kind of religion-blind secularism that frames Hinduism as national culture, which will always favor Hindus in a Hindu majority context. In a strange inversion, the Hindu nationalist party is now a champion of Hindutva secularism and treats religious minorities as “communal” if they make any claims on the state on behalf of their community, exposing them to punishment. This ideology is deeply ahistorical and is used to justify discrimination against non-Hindus. FBOs’ understandings and maneuvering of civic space in the Indian context can be understood through this prism, as we show later in this article.

Just as there is a context of contested meanings over the secular in India, there is also a contextual history over the meaning of the political. MK Gandhi, who mobilized rural peasants along with urban elites in an anti-colonial struggle, rejected “politics.” That is, he believed that the state cannot provide a means to achieving a just society. This led him to propose disbanding the Congress party once independence was achieved, guided his refusal to accept an official role in the new government, and led to his marginalization in the postcolonial state being created (Dasgupta Reference Dasgupta2017). In the nonprofit sector in India, Gandhian and socialist organizations claim that they are engaged in sewa not rajneeti (service not politics). This tendency was strengthened by the experience of crackdowns during the Emergency in the mid-1970s when many CSOs were banned (Deo Reference Deo2012). To this day, “the political” in common parlance is often tainted with deeply negative associations of conflict and corruption, rather than peaceful negotiation and resolution of differences, or work to advance legitimate public interest. As we discuss below, FBOs’ understanding and maneuvering of civic space in India is to be understood through these two contextual prisms of secularism and politics.

Research methods

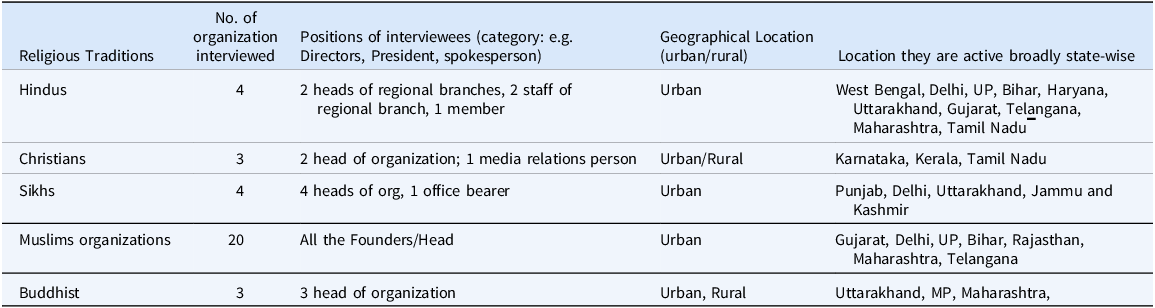

For this study, we interviewed leaders and some staff of FBOs of five major religious traditions in India (Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism, Christianity, and Buddhist) as seen in Table 2. We identified organizations with reputations for being FBOs in snowball samples that built on each of our individual research efforts conducted adjacent to this collaborative project. We identified FBOs largely by name and the types of activities they conduct. For example, an organization called “Christian Volunteers” or “Navayana Women’s Front,” presents themselves as associated with a faith tradition.Footnote 5 For legal reasons, all FBOs keep proselytizing activity quite distinct from their social work. They also must keep away from electoral activity under the Trusts and Societies rules. Further, each of the four interviewing investigators sought diversity in terms of geography, organizational structure, and type of activities among the FBOs we contacted. Our initial interviews left us with rich data from Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, and Christian FBOs. However, our interviews with Muslim FBOs were much less detailed. When our team found Sumita Pahwa was interviewing Muslim organizations in Western and Southern India for a project on Muslim civil society, we invited her to join our project and to integrate her data with ours. Her interviews included many questions that the larger team had not pursued, but Pahwa was asking Muslim CSOs about their work, their relationships with the state, and who they serve, thus making that data comparable to that of the original researchers. The types of activities FBOs engage in range from those that provide health care, to career counseling, to spiritual regeneration, to human rights protection, and legal advocacy. We looked for patterns in our interview data to see if the size, type of activity, location, faith tradition, and other variables shaped their experiences in systematic ways.

Table 2. Interview subjects

About two-thirds of our interviews were conducted over Zoom due to the COVID pandemic, but the other third took place in person. The concerns about surveillance were heightened over video conference, and working with Zoom inhibited our ability to build trust and rapport with our interviewees. We did run into some limits with interviewees’ openness, some of whom were hesitant about what to say, considering the current regime. They feared greater scrutiny of their tax records, delays in grant approvals, denial of grants, and even arrest and prosecution for alleged disloyalty. Nevertheless, we believe we captured meaningful information about how FBOs perceive and navigate their room to operate under a Hindu nationalist government, also precisely because of interviewees’ guarded, or deliberate, expressions. The perspectives shared arguably reflect the roles staff members see as publicly possible within the current Indian context. Moreover, the validity of findings is underlined by the similarities and differences between organizations grounded in different faith traditions, closely connected with their tradition and how they relate to Hindu nationalism.

As we collected our interviews, we shared the transcripts with each other. We engaged in thematic and narrative analysis. The thematic analysis pointed us in the direction of seeing the importance of secularism and service as important aspects of how FBOs describe their work. The narrative analysis showed how the FBOs often creatively managed the constrained civic space to also engage in advocacy on behalf of their faith communities.

Findings

Across faith traditions, interviewees stress the non-political, secular, and service-oriented nature of their work in interconnected ways. This similarity reflects the way in which the secular and political are understood in the Indian context, expressing a contextually defined approach to civic space conditions constructed by the majoritarian government as perceived by FBOs. At the same time, the way different faith traditions are seen by a religious majoritarian state makes for important differences, reflecting the differentiated space for politics that FBOs from different faith traditions perceive.

Political space

In describing their role, FBOs were inclined to present their identity as apolitical and take a careful approach to the state. Organizations from minority religious traditions explained that their religion could be a soft target and thus choose not to be openly critical about the state, its policies, and politics in general. They risk a range of legal and administrative “barriers” being raised against their work (Chaudhry Reference Chaudhry2022). Minority FBOs, especially the Muslim ones, were not critical of the state and are guarded when it comes to speaking about majoritarian politics, right-wing state administration, and growing Hindu Nationalism. They insist that they do nothing which can be classified as anti-state, and mostly denied doing any advocacy. This connects then to notions of the political, as being partial to a faith. That is, this reflects the norm that any work deemed to strengthen a “particular” religious community rather than the “national” community is stigmatized as “political.” While recognizing that their service-oriented work (discussed in the next section) would allow “the community” to be more empowered, Muslim FBO leaders acknowledge that being seen as political would be dangerous for their organizations, creating a need for careful public image management. One interviewee ruefully noted that working in urban slums with large minority populations raises uncomfortable questions [from funders] about “the Muslim agenda” and that they keep their political opinions separate out of fear of political blowback. Another acknowledged being meticulous about fiscal transparency because any misstep could leave them open to government pressure. Some organizations reported in 2023 that state authorities had removed their clearance to receive FCRA funds and they tried to remove their charitable trust designation exempting them from income tax, on the accusation that they serve “only one community” and that they proselytize if religious literature is present at their service office. However, we often found that interviewees from Muslim organizations were evasive when we asked questions about their operational space under the current regime. As one Muslim human rights activist noted, “any Muslim organization risks having the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act [UAPA] thrown at it…call it social work and you are fine but call it human rights and you get into trouble.” The UAPA allows for preventative arrest and detention of individuals suspected of anti-national activities. Another emphasized that “in our bylaws we have not put down that we are working with a particular community, or we wouldn’t get registered.” These FBO activists showed awareness of the lines they did not want to cross as they responded to queries by giving limited, safe, information.

Organizational relations with the state shape FBO disclosures: Muslim FBOs that aspire to have state collaborations, hold FCRA clearances, are aiming for government grants for service provision, and want recognition in the eyes of the state in the future, made it clear that they were not “anti-state” (a common way of delegitimizing opposition against the government in India at present) and prefer to do service delivery rather than political advocacy of any kind. They avoided discussing politics, claimed to want to cooperate with the state and to want recognition in the eyes of the state so that they can be given preferential access to government projects and cooperation. Although some are not receiving any funds from the state, they are open to partnership, prefer to have a neutral stance about whichever political party comes to power, and want to work with the government. For example, one of the Muslim FBOs states, “We want Muslim reform and representation of Muslim issues which can be done when we work with the state support only.”

Sikh FBOs working on humanitarian relief and with victims of major disasters also want to be viewed as non-political. For instance, one said, “When we engage in different types of activities, we have to be very careful of how we are being viewed. When young people are joining us, we don’t want to create an image that these young volunteers are being taught to demonstrate and hold marches. Instead, we want to be seen as service providers.” They particularly want to be seen as organizations that do not engage in political advocacy. Even groups that gave food and water to protestors in Shaheen BaghFootnote 6 describe themselves as non-political.

However, this is a more surprising finding: minority FBOs were not the only ones wanting to be viewed as apolitical. Hindu FBOs also did not want to be viewed as allies of the government. They would like to be seen as autonomous and as having their own identity, which cannot be defined by the government. An example of this is when one of the Hindu FBO members said, “During a disaster, we start identifying the areas for relief and the party workers of the ruling party approach us to give service in their constituencies, but we never act on such requests. We identify areas as per the situation on the ground and then extend our service.” Two of the Hindu FBOs were collecting funds for a Ram temple at Ayodhya, and they advocated for its construction, which was completed in 2024. They present this as advocacy for their faith and not as political advocacy, even though most observers identify this campaign as crucial to the growth of Hindu nationalism in India. However, Hindu FBOs do openly talk about the politics shaping the state and the supportive nature of the state for some FBOs. Hindu FBOs were not critical of the state apart from speaking about bureaucratic bottlenecks, and they spoke highly of the state administration in collaborating with FBOs.

Some marginalized FBOs, such as Sikh and Christian Dalit organizations (specifically those not receiving funds from the state), were open to discussing the state more critically, discussing politics, corruption, and problems they face due to state actions. For example, Christian Dalit FBOs that do not receive any funds from the state talked about the hostile attitudes towards minorities by the current state administration, corruption, and increasing regulation, although some only did so because they were assured of anonymity. Similarly, Sikh FBOs, which do not receive any funds from the state and do not plan to have their work funded by the state, were willing to talk openly about politics. While organizations are guarded and careful of being critical of the state, their approach is also shaped by their representation of their own identities as apolitical. These constructions are grounded in contextually specific understandings of the political as a domain unfitting for FBOs. Describing themselves as “apolitical” avoids a direct critique of the government, it frames FBO activity in these contentious arenas as morally pure, because it is motivated by non-political goals.

While FBOs appear to be toeing ideological state lines or maybe accepting them, strategic considerations play a role here. Some FBOs that aim to secure funding and recognition from the state explained how this contributes to their being careful about their identity, especially to be seen as apolitical. Even those not looking for state support feel this pressure. At present, many CSOs in India seek what are called CSR funds. These are funds provided by companies for social development projects under India’s Companies Act, which requires they spend a minimum of 2% of their net profit over the preceding three years on CSR activities. An interviewee from a Muslim organization seeking such funding stated that those with the word Muslim in their name are unlikely to get it. An interviewee from another Muslim FBO explained: “We do not want to face witch-hunting and try to work with the government support, as we do service delivery and not political advocacy. The reason for this is that we aim to secure funding from the government schemes in the future.” Those minority FBOs that have an FCRA license are not openly critical and did not mention any threat from the state, nor did they discuss politics in general. They also choose not to do any obviously political advocacy. This could be because they do not want their FCRA license canceled or to face other repercussions from the state. There is not a significant difference between those FBOs that simply want to maintain an FCRA clearance and those that wish to win government grants, which indicates a possible limit to ideologically driven state funding. That is, the similarity of these two conditions—being able to operate with a FCRA license and being likely to win government contracts may suggest that the state is not actively awarding funding based on ideology alone, but rather on a more neutral basis of functionality.

Finally, many minority FBOs that we interviewed in person and over Zoom reported being under surveillance, and this additional scrutiny likely chilled their willingness to offer any criticism of the state. Especially as many of our interviews were conducted over Zoom, even if they trusted us as researchers, they could reasonably fear digital surveillance software.

Service, constituency advocacy, and being “open to all”

The focus on apolitical work also connects closely to the emphasis on service delivery in interviewees’ discussions of their role. Despite constraints and the apparent acceptance of the need to present as apolitical, FBOs seek to protect or advance the position of their constituencies in India, addressing questions of rights, economic position, and social standing. FBOs commonly seek to advance these through service, conceptualized as open to all in society, and thus “secular” in the sense of impartiality to faith and not underlining religious difference. At the same time, most of them also indicate that it is precisely their faith traditions that motivate them to serve society, bringing in religious diversity in a non-political way. As interviewees argue, the Christian, Muslim, Sikh, etc., understanding of social service as a religious obligation motivates them to engage in civic work. Most of the minority FBOs—irrespective of their faith (Sikh, Muslim, and Christian)—want to be viewed as service-based organizations and stress being non-political by implication. As an interviewee from a Muslim organization said:

“Our motto is simple which is derived from the Creation of Humanity, verse 11.7 from the Quran; God wants Man to serve his fellow human beings. The purpose of creating you is to serve others who are not so privileged and fortunate human beings. Serving the community is serving the society. Human values are all about interfaith understanding and that is what we adhere to in our work…. We mainly do service delivery, that too within the parameters of democratic means. Nothing that can be classified as anti-state.”

Most CSOs led by Muslims and serving a majority Muslim population in Mumbai and Hyderabad focus on services, notably in education and employment, as the best way to help Muslims advance and work pragmatically with the state as needed, whether to connect beneficiaries with available government scholarships, or to maintain working relations with state-level politicians from all parties to advocate for projects and policies that could help working-class Muslims.

The Sikh FBOs, to varied degrees, believe in and follow the Sikh philosophy of Sewa (service). Their motivation to extend service is primarily drawn from the Sikh teachings of various teachers (gurus). For all four Sikh FBOs, which extend services like healthcare, distribution of essential items during an emergency, etc., the services are given across communities. For example, the beneficiaries of one of the Sikh FBOs include victims of earthquake and drought in Gujarat, the victims of floods in Assam, and Kashmiri students who were attacked after the withdrawal of Article 370. Most of these beneficiaries are not Sikh. In their interview with us, one of their leaders says that they also extended food as a service to the protestors of Shaheen Bagh and the farmers protesting proposed farm laws. On several occasions, they have faced the wrath of their own community members who question why they extend aid to members of other faiths. One organization said they overcome this issue by going to gurudwaras (Sikh places of worship) and addressing their community members, explaining their work and the philosophy behind it.

Interviewees emphasize how their work is apolitical, as it is grounded in the ideal of extending service to anyone in need and say they do not distinguish between the needs and wants of various groups and communities. In fact, one organization shares with us that “[We] are careful in ensuring that we are not viewed as a political organization as this is a huge responsibility.” This is important because they want more young members to join the organization as volunteers and that is not possible if they associate themselves with advocacy. The head of the above-quoted Sikh FBOs mentions that the elders in the family (like parents) will not let the children and youth participate as volunteers if they showed any political affiliation. Another organization, involved in providing health-based services during the COVID-19 pandemic, says that they hesitate to take money from donors as it comes with expectations attached, and this is particularly true of political groups or parties.

Hindu organizations also stress service open to all, even though this was not necessarily reflected in the actual usage of their service. One of the Hindu organizations made a distinction between the types of service given to all communities vis-à-vis those services which are not used by all communities. The Hindu FBO member said:

“We are an organization open to all communities and groups. In fact, our guru even helped a few Muslim families when they were in need. We do not believe in only extending our medical and other such services to one community. There are people from all over the world who come and avail the medical facilities in the trust hospital built in the name of our trust. However, the Vedic education [related to Vedas, the holy ancient scripture of Hindus written in Sanskrit] is not something that anyone can easily learn and therefore all our students belong to a particular community.”

Christian FBOs insisted that they serve all communities, explaining that they are not primarily working to convert anyone (a common accusation leveled at Christian organizations in India), but that their faith guides their service (Kaur Reference Kaur2024). One Christian FBO worker explained his work and commitment, suggesting that it is inherently part of Christian faith to serve others, compared with other faith traditions that in his view do not have the same charitable attitude. Another describes who they work with by claiming to be both secular and religious, integrating these two perspectives in a way fitting the position of providing service from faith while recognizing the role of religious diversity and the inequalities of Indian society as foundational to their work:

“We have been supporting our children regardless of their religion, regardless of their caste, regardless of their economic background. Religion is not important for me, even though I am a chaplain. We have to respect people’s faith… So, we function as a CSO under the rules of the Indian Government. But when they look at our school, when they look at the people who are with us operating, they know that we are all Christians. At the same time, they look carefully at whom we are serving: 90%, 80%, 90% are Hindus, Muslims. As I said, we don’t discriminate. Christians, Muslims, we consider them Indians, that’s it! Period! Most of them are Dalits because in that area all those people who are living in the rural villages, the majority are either backward communities or Dalits. We don’t have too many forward communities in our area like Brahmins and all those people.”

The sewa, or service, is motivated by faith but the benefits are available to all, even if there is selective uptake of a particular service. Each of the interviewees who spoke about the role of faith in inspiring and sustaining their work stresses that they would offer their assistance to anyone in need. That is, they are not narrowly sectarian or communal, as that would run counter to the legal framework for CSOs in India. Instead, their efforts are motivated by faith, but practiced in a way that is open to all regardless of faith.

Differentiated spaces to act in

Literature on civic space tends to differentiate conditions and relations between state and CSOs considering the degree to which the state constrains civic space, and the way the state differentiates between types of organizations, with the most important differentiation between advocacy and service delivery organizations (Toepler et al., Reference Toepler, Zimmer, Fröhlich and Obuch2020). This comes to define CSOs’ “operational space.” However, FBOs rooted in different faith traditions in India seek to advance their goals through diverse approaches meant to address the different conditions their constituencies face, which are related to the position of diverse faith traditions in India. The Indian case thus illustrates the need for approaches to civic space adjusted to the Hindu nationalist context. A first difference to relate to is this: How each faith tradition is framed within Hindutva ideology leads FBOs from diverse faith traditions to perceive differentiated opportunities and challenges in their relations with the Indian state. A second difference is: responses differ based on the differentiated position of faith traditions in Indian society. That is, the position of the religious community itself in terms of access to respect and resources shapes how FBOs define their objectives, and thus also the civic space conditions to engage. Importantly, the two aspects of the approaches are intertwined, leading to a situation where FBOs from different traditions perceive different spaces to act and to achieve their different objectives regarding the advancement of their constituents. At the same time, we note variety within each faith tradition, necessitating caution in attributing coherent understandings and strategies to any of the faith traditions. Below, we will illustrate these findings with discussion of how this plays out for each faith tradition, clarifying how interpretation and maneuvering civic space for FBOs under a Hindu nationalist regime is to be understood from the differentiated state framings and positions in society as discussed above.

While Hindu organizations are active on many fronts, some of them seek to counter the success of Christian organizations in Adivasi (tribal) areas, thus indicating competition between faith communities, directly or indirectly facilitated by the Indian state (Reddy Reference Reddy2011). These organizations set up schools and health care centers, attend to food and water supply issues, and provide legal aid to Adivasis. Some of the Hindu FBOs come with other “assertive” tactics, for instance, synchronizing Adivasi religious and cultural practices with those of mainstream Hinduism and organizing reconversion ceremonies for those who are Christian (Reddy Reference Reddy2011). This competition and tension between the Hindu FBOs and Christian missionaries is a long-standing struggle by these organizations to target the tribal communities in several parts of the country (Hansen Reference Hansen1999; Sarkar Reference Sarkar, Needham and Rajan2007). One key staff member we interview says, “We have expanded our branches to the tribal regions and I think it is an important move as conversion rate is very high in these regions.” However, this approach is not taken by all Hindu FBOs working with marginalized groups. Some Hindu organizations extend services to these tribal communities with no specific agenda to limit conversions. The Hindu organizations, in their approach towards extending service to specific communities, also seem to receive the approval of the state, which views their work as “valuable” and significant in extending essential services to the communities who need them.

Sikh organizations experience relations with the state and its institutions in diverse ways, depending on who they advocate for, where they are located, and how their influence spreads. Most of the Sikh organizations we interviewed said that the state and its agencies over the last decade have become more stringent when it comes to monitoring the work of CSOs in general and FBOs in particular. One of the Sikh organizations, which has an international presence, said that there is constant surveillance by intelligence officials, and several times they have been questioned by investigating agencies about their motives and work. This view is not shared by all Sikh organizations, and some feel that the state agencies only target those organizations that they view as security concerns. It also appears to us that Sikhs may be relatively highly scrutinized because of the historical legacy of the state repression of the Khalistan movement and its continuing support among the Sikh diaspora. Overall, however, smaller organizations with limited presence in specific districts often have cordial relations with state authorities, and their presence is not even felt by the state. They continue to work with the community in their own small ways with almost no interference from the state in extending services. Therefore, there is a diversity in how they experience the state and its entities in their everyday work. We find that there is an uncomfortable relationship between the state and those marginalized FBOs that either have, or aspire to have, an international presence or that work closely with aid from religious communities who live outside the country. Thus, in the case of Sikh organizations, what draws the attention of the state is not so much their service work but who they advocate for, where they are located, and how their influence spreads. Muslim organizations seem most keen to avoid confrontation with the state, taking care to stay within strict limits—seemingly in response to the marginalization of their faith in India in recent years, politically and socially—to the extent that the threat to their operations is addressed in our conversations with them only in indirect ways. At the same time, they seek to uplift their communities economically and socially, advancing their emancipation through education and support on the job market, seeking to counter the community’s marginalization through this avenue. Many Sikh organizations, like the Muslim ones, appear unwilling to be openly critical of the Modi government. Their history as targets of federal violence has made them wary of the state under both Congress and BJP alliances.

Dalit Buddhist organizations seek to uplift their community through service, organizing, and advocacy in the face of a state that fails their emancipation and a society that reinforces their oppression. They are relatively open in their critique of the Hindu nationalist government, understood in casteist terms, and address both state and society on this matter. A leader of a Dalit Buddhist organization said,

“Be it at the school level or at the Shastri Bhavan [national government building], be it about the handpump or Panchayat Bhavan [local government building] there was discrimination everywhere. When panchayat meetings were held these people [Dalits] used to sit where others took off their shoes. And all those who belonged to the upper caste people, they used to sit on chairs, and they [Dalits] had to sit outside and express their opinions and convey their demands.”

The highly critical stances taken by B.R. Ambedkar (who founded the Navayana Buddhist school which most Dalit Buddhists follow) provide a template for the more critical view Dalit Buddhist FBOs take of the current government and society. For Buddhist FBOs, their main challenge as a FBO is indeed confronting the deeply entrenched caste apartheid of the Indian state and society. They recognize that their work, however service-oriented, cannot be anything but political, and they are openly critical of the BJP government. They describe it as corrupt, hostile to development, anti-Dalit, and willing to use all kinds of regulations to strangle civil society. The main challenges they identify are petty harassment, attempts to take credit for their work without making the reforms they called for, and the general blindness of a casteist society to the plight of Dalits.

“This is their reign, nobody can say anything to them because they have all the power, if somebody says anything, they will have to face many problems, that is the reason everybody is quiet. People have stopped saying anything against them. They control the news channels and newspapers, what they say is what we see and listen, and they show what they want, not the reality. According to them, this is democracy. We are seeing what kind of democracy this is. We can’t do anything.”

Christian organizations similarly seek the upliftment of constituents, stressing, like Dalit Buddhist organizations, the need to work towards inclusion and equality. The Christian organizations are clear that the challenges they face are due to the religious prejudices of the BJP government. Even if it doesn’t target them for serving Dalits and Adivasis, it sees them as a threat because they are Christian. An interviewee from an FBO that had its FCRA license revoked and is no longer operating in India said,

“Why were we targeted? I can only speculate that it was because of our fund flows which were around $48 million annually. The change was because the Modi government is hostile to religious organizations. They wanted to make an example of us. India is on the cusp of being a state where freedom of religion only exists in theory. In practice the foreign funding rules restrict us.”

Another said,

“Especially under this current administration BJP which is very hostile to minorities, religious minorities, even for Dalits. They may say so many things, all rubbish, “oh we don’t do this, we don’t do this,” but when you see the ground reality it is totally opposite. The current administration says, “no we are working for Dalits. We have appointed the president, who is a Dalit, we have appointed an MLA who is a Dalit,” they are for their own favors they do some of those things. Just to show to the world a drama, a show that we are not unfair. But in reality, they are using, they are abusing the Dalits sometimes. This comes from the hatred this RSS is carrying all these years. For them only the Hindus should live in India. For them, not only Hindus, only the upper caste they have to rule the country. Any challenge for their authority, they could not accept that.”

These are sharp criticisms of the Hindu nationalist government and of a society that fails to be inclusive or secular.

Conclusion: Towards a contextual understanding of FBOs navigating a religious majoritarian state

To return to the research question of this article: How does the religious nationalist state, which seeks to reshape and constrain civil society from its ideological basis, affect FBOs? We find that all FBOs adopt similar rhetorical strategies to protect themselves, but they relate to the state quite differently depending on the distinctive history of their faith community. In key respects, FBOs rooted in diverse faith traditions perceive and respond to the civic space conditions created for them by the majoritarian government in similar ways. This is a surprising insight, given the differentiated way in which the majoritarian nationalist state considers the role of faith traditions in India. A first similarity is that in response to conditions as they perceive them, most FBOs stress the secular nature of their aims, in ways that are in line with Indian majoritarian secularism, in the sense that they foreswear any possible claim to legitimately advance the interests of their religious community. The emphasis on being apolitical, building on an understanding of politics as morally impure, strengthens this understanding in many cases. This disavowal of politics is both strategic and draws on long-standing Indian discourses about the immorality of political activity. Organizations from most faith traditions seek to “play it safe” by denying any will to engage in politics, openness to all communities, and a focus on service delivery, while seeking to maintain a clean track record to avoid common accusations of illegality. Such responses show close similarity to some findings on implications of constraints to civic space more broadly, internationally and in India (Hossain et al. Reference Hossain, Khurana, Mohmand, Nazneen, Oosterom, Roberts, Santos, Shankland and Schröder2018), Moving away from sensitive topics, carefully treading around conditions, and sticking to service delivery, at least in appearance, are common responses to civic space constraints (Fransen et al. Reference Fransen, Dupuy, Hinfelaar and Zakaria Mazumder2021). However, the findings also shed light on the importance of the Hindu nationalist context that marginalizes religious minorities politically, supported by a discourse on secularism and politics that delegitimize FBO advocacy.

Muslim organizations describe themselves as working to uplift and reform their community. They see their role as helping to “secularize” and professionalize Muslims so they can help themselves, even as their work is based on their Islamic faith and its call to serve others. They mostly describe their work as service-based, with little space for advocacy, while also seeking to establish themselves as trustworthy partners for the state. Christian organizations claim to serve all groups, from charity as a tenet of their faith, while arguing against accusations of conversion activities commonly levied at them. They address, through their work, social and economic inequalities in India, including those rooted in caste. Sikh organizations stress the importance of their gurus in inspiring them to serve all of humanity. They work across communities, including those engaged in opposition to the state, while describing themselves as neutral or apolitical.

These narrative patterns are deeply rooted in the historical legacy and context of Indian decolonization and how those elements are deployed in the Hindu nationalist context of today. A key element of that context concerns understandings of the “secular” and the “political.” FBOs define their roles in these terms, with great impact for the space they conceive for advocacy grounded in their faiths or the interests of their constituencies.

These conditions, which delimit the space for religion per se as the basis for advocacy, have decisive influence on the way organizations construct their roles, undermining advocacy grounded in their religious traditions and constituencies.

At the same time, religion remains fundamental to the organizations in this study, in the way their faiths motivate them to do their work, also given the position of their communities in present-day India. And we also see diversity in the space for advocacy and the ways in which religious commitments are translated into action. For example, Hindu organizations talk about the sants (saints) that inspired their organization, orienting them towards service, especially education, while their educational activities can also be seen as countering the success of Christian organizations in Adivasi areas, which marks them as both political and favored by the state. Buddhist Dalit organizations are committed to empowering their highly marginalized community. They are the most explicit about engaging in advocacy that can be seen as political, but they also describe themselves as secular and inclusive in who they serve. These groups are the most critical of the BJP government, which they see as hostile to their community and its development.

More broadly speaking, we see that even in situations of civic repression, FBOs reinvent themselves and seek ways to do work, showing resilience and differentiated approaches to the constraints they face, while working from their commitments to the degree possible. At the same time, the future of FBOs in India remains difficult. There are few signs of an emerging political alternative to the Hindu nationalist government in power now. The rules and regulations for civic associations continue to become more onerous. In this environment, we expect that most FBOs will continue to serve their constituencies by adopting apolitical service roles as their public face while quietly engaging in advocacy where it is possible. For the few FBOs who have external sources of funding and are not seen as threats to the governing order, a more vocal opposition may be possible. The fact that FBOs from each tradition are facing their distinct challenges reveals the extent to which religion shapes civil life in today’s India. It also offers signs that room to maneuver is available at differential rates. Even if Muslim organizations must remain relatively quiescent, Dalit and Sikh organizations may be able to offer more pointed critiques of state policy.

Competing interests

Nandini Deo: I confirm that neither I nor any of my relatives nor any business with which I am associated have any personal or business interest in or potential for personal gain from any of the organizations or projects linked to this paper.

R. Balasubramanian: I confirm that neither I nor any of my relatives nor any business with which I am associated have any personal or business interest in or potential for personal gain from any of the organizations or projects linked to this paper.

Farhat Naz: I confirm that neither I nor any of my relatives nor any business with which I am associated have any personal or business interest in or potential for personal gain from any of the organizations or projects linked to this paper.

Sumita Pawha: I confirm that neither I nor any of my relatives nor any business with which I am associated have any personal or business interest in or potential for personal gain from any of the organizations or projects linked to this paper.

Margit van Wessel: I confirm that neither I nor any of my relatives nor any business with which I am associated have any personal or business interest in or potential for personal gain from any of the organizations or projects linked to this paper.

B. Rajeshwari is Thematic Lead (Research, Policy, and Communications) at Azad Foundation, New Delhi. Her main research interests include civil society collaborations, feminist studies, environment, and climate change governance.

Nandini Deo is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Lehigh University, USA. She works on democratic theory, civil society, religion, religion, and education with a focus on social activists.

Farhat Naz is an Associate Professor of Sociology in the School of Liberal Arts at the Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur, India. Her main research interests include natural resource management, water governance, disaster risk reduction, CSOs, and policy and governance studies.

Sumita Pahwa is an Associate Professor of Politics at Scripps College in Claremont CA. Her research and teaching focus on religion, politics, and social movements in South Asia and the Middle East.

Margit van Wessel is an Associate Professor in the Strategic Communication Chair Group at Wageningen University & Research, the Netherlands. Her main interest is civil society advocacy, with a focus on questions of voice, representation, and power.