Introduction

Vision impairment affects 2.2 billion people globally, of which, around one billion cases are avoidable or yet to be addressed (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2019). In addition to being a global financial burden, unaddressed vision impairment affects many aspects of life, health, and sustainable development (Burton et al, Reference Burton, Ramke, Marques, Bourne, Congdon, Jones, Tong, Arunga, Bachani, Bascaran and Bastawrous2021; United Nations (UN), 2018). A large proportion of those affected by unaddressed or preventable vision impairment live in low- and middle-income countries (WHO, 2019; Burton et al, Reference Burton, Ramke, Marques, Bourne, Congdon, Jones, Tong, Arunga, Bachani, Bascaran and Bastawrous2021). Accessible eye care services can help to reduce the prevalence of avoidable blindness within a population by providing timely high-quality interventions to those who may benefit from them. Healthcare access has been defined as ‘the opportunity to reach and obtain appropriate health care services in situations of perceived need for care’ (Levesque, Harris and Russell, Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell2013). A recent scoping review (Malik et al, Reference Malik, Strang, Campbell and Jonuscheit2022) has identified a scarcity of high-quality evidence and the need for research surrounding the experiences of older age groups with eye care in Pakistan; specifically in view of an increasing prevalence of age-related eye conditions, significantly associated with more severe levels of impaired vision (Dineen et al, 2006; Jadoon et al, Reference Jadoon, Dineen, Bourne, Shah, Khan, Johnson, Gilbert and Khan2006).

Moreover, potential financial difficulties due to substantial health expenses are a global concern, especially in developing countries, where inadequacy of the state-provided health system results in high out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure. Around 100 million people experience extreme poverty annually due to OOP expenditure on health services (World Health Organisation, 2022). In Pakistan, OOP payments finance 55% of total healthcare costs. The average annual household income per capita is 132,089 PKR (∼GBP481) in Pakistan, with the gap between the rich and poor widening (CEIC, 2019; Islam et al, Reference Islam, Abrar, Arshad and Akram2022).

Considering global healthcare needs more broadly (i.e. beyond eye care), around half of the world’s population do not receive the healthcare they require (World Health Organisation, 2022). Universal health coverage (UHC) an initiative launched by the World Health Organisation is defined as, individuals having equal access to the health services they require, where and when they require them, and without financial hardship. Many low- and middle-income countries have implemented various health insurance schemes with a view to achieving UHC while reducing OOP costs (Bitran, Reference Bitran2014; Bredenkamp et al, Reference Bredenkamp, Evans, Lagrada, Langenbrunner, Nachuk and Palu2015).

As part of recent and ongoing initiatives to achieve UHC in Pakistan by 2030, the Sehat Sahulat programme (SSP), a health insurance scheme, was launched in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (KPK) in 2015 (Cheema et al, Reference Cheema, Zaidi, Najmi, Khan, Kori and Shah2020). Initially users of the scheme had to apply for the ‘Sehat Insaf card’, which needed to be shown upon use at eligible hospitals. Currently, the SSP is available to all permanent residents in KPK, Punjab, Gilgit–Baltistan, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Islamabad, district Tharpakar (Sindh), and to all transgender communities across Pakistan who are registered with the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) and have a computerized national identity card (CINC) (Sehat Sahulat Programme, 2022).

The SSP provides an allowance to families to use towards healthcare costs, which is renewed annually without rollover. The SSP can be used towards secondary care in-patient medical services with additional financial limits assigned for certain treatments (i.e. cancer, cardiological interventions, dialysis, and renal transplant), emergency situations, and in the event of maternity. Transport costs up to 1,000 PKR (GBP3.64) to reach a secondary health care facility are covered three times per year, and transport for patients referred by a secondary care hospital to a tertiary care hospital are also covered under the SSP (Din et al., Reference Din, Mashhadi, Khan, Zubair, Khan and Hussain2022). In the KPK province the ‘Sehat card plus’ initiative is being rolled out where higher allowances are provided for secondary and tertiary in-patient care (Health Department Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 2021). The SSP is a cashless scheme for insured people, administered through the State Life Insurance Corporation (SLIC). The provincial government currently pays a fixed premium per eligible family to SLIC, which manages members’ in-patient healthcare expenses at participating private and public healthcare facilities. At the end of the 3-year contract period with SLIC, the provincial government receives a refund of 90% of any unspent net premium (Morgan and International Labour Organisation, Reference Morgan2019; Forman et al., Reference Forman, Ambreen, Shah, Mossialos and Nasir2022; Shaikh & Ali, Reference Shaikh and Ali2023). There is a paucity of research on the SSP’s use towards eye care services. To improve efficiencies in decision-making processes and resource allocation in healthcare, information regarding the SSP with respect to eye care services needs to be generated, which will in turn provide valuable evidence to both care providers and users, as the programme continues to gain popularity.

To capture comprehensive qualitative and quantitative evidence and to allow for a meaningful synthesis of the data the study adopted a mixed methods design to evaluate access of eye care services in Pakistan, with a focus on older age groups. The aim of this research is to answer the following research questions 1) What barriers do older age groups experience in relation to accessing eye care in Pakistan? 2) Is access to eye care influenced by the SSP and what other costs are associated with eye care access?

Methods

Study design and participants

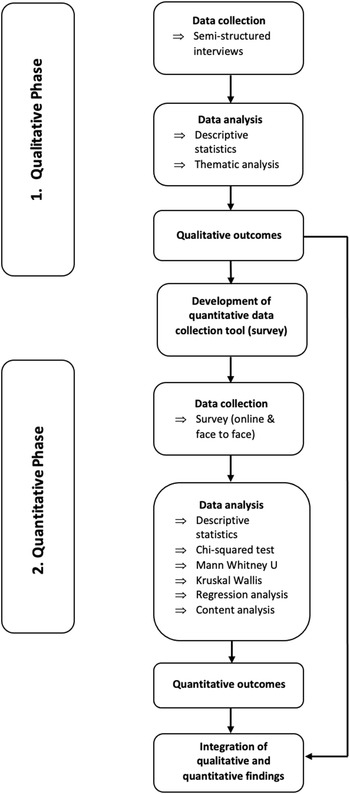

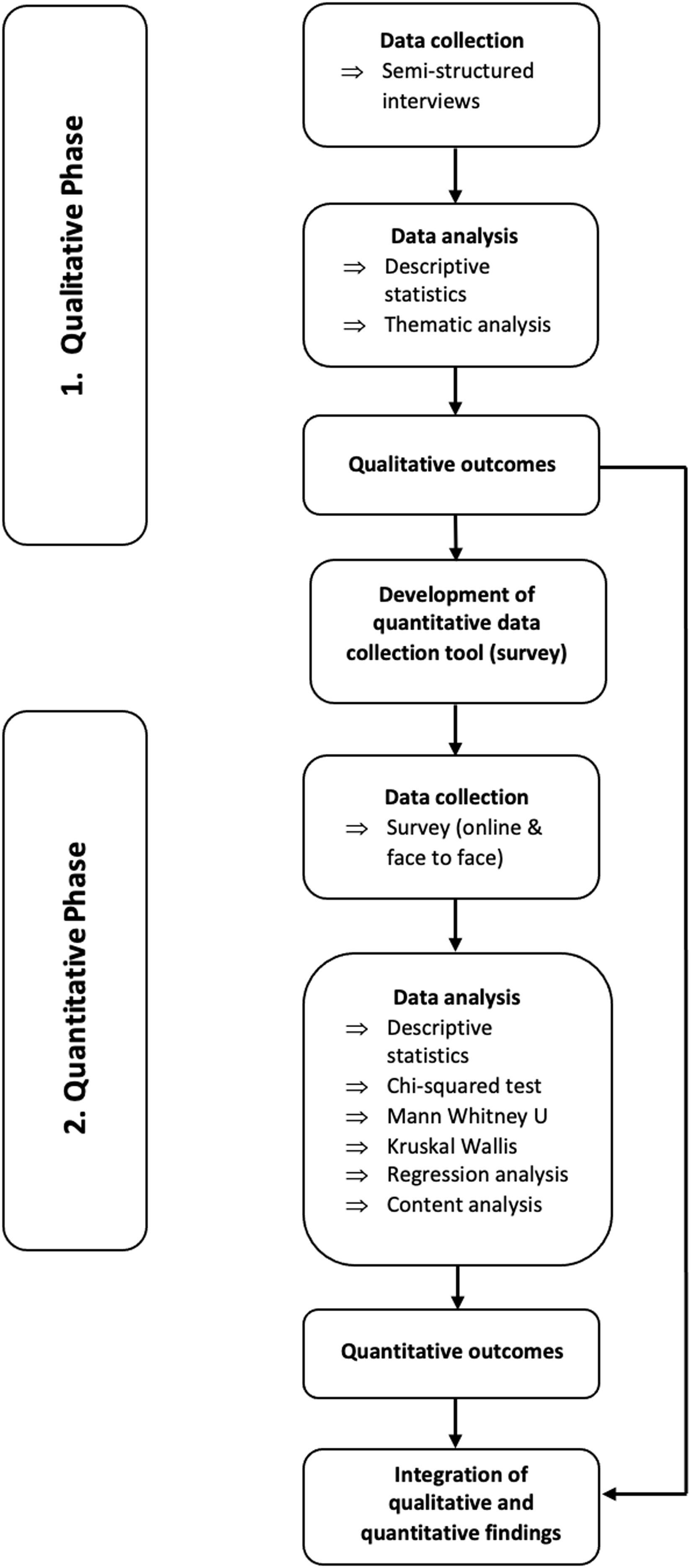

To develop a detailed understanding of patient views and priorities in terms of eye care in Pakistan, an exploratory sequential mixed methods design was used (Fetters, Curry and Creswell, Reference Fetters, Curry and Creswell2013) – see Figure 1. The design begins by exploring with qualitative interviews, to better understand the views, beliefs, and perspectives of participants towards access to eye care in Pakistan (phase one). Phase two involves building on the results of phase one, to design and use a survey tool tailored to meet the needs of the individuals being surveyed; allowing for the quantification of barriers to access eye care. Data from both phases were then integrated in a mixed methods display (Fetters, Curry and Creswell, Reference Fetters, Curry and Creswell2013). Ethical approval for phase one of the study was granted by the ethics review board of the authors’ institute on the 1st of July 2021, and approval for phase two was granted on the 12th of November 2021.

Figure 1. Illustration of exploratory sequential design of mixed methods study, showing initial qualitative phase, followed by survey development and secondary quantitative phase and ending with integration of outcomes from both phases.

An information sheet was provided to all participants recruited for the study. For the qualitative interviews, a consent sheet was emailed to participants to fill and return. For participants unable to sign and return the consent form, due to technological difficulties, verbal consent was obtained prior to starting the interview. For the online survey, participants provided implied consent by proceeding with the survey, as indicated on the first page: ‘By continuing with the survey, you are providing consent to participation’. For participants recruited for the face-to-face survey consent was obtained prior to asking the survey questions, by asking the following statement: ‘Please tick the box next to this statement to confirm that you have read and understood the information sheet and agree to participate in this survey’.

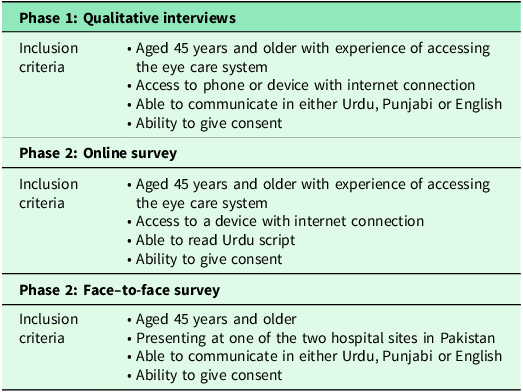

Purposive sampling was adopted in this study as participants were identified through personal and professional contacts and by word of mouth (Hibberts et al., Reference Hibberts, Johnson and Hudson2012). Participants aged 45 years and older were invited to take part in the study. The inclusion of participants aged 45 years and older aligns with the study’s focus on the older population, as age-related eye conditions (i.e. presbyopia) often begin to emerge in mid-life. With Pakistan’s rising life expectancy and aging population, the demand for eye care services is expected to increase (Dineen et al., Reference Dineen, Bourne, Jadoon, Shah, Khan, Foster, Gilbert and Khan2007; Najam & Bari, Reference Najam and Bari2017). Addressing eye care needs from mid-life onward will help manage the growing demand and contribute to reducing avoidable blindness amongst the older population. An information sheet was given to all participants and consent obtained prior to involving them in the study. Detailed inclusion criteria for phase one and two can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria for both phases of exploratory sequential mixed methods study

Qualitative phase

Data collection

Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, with questions designed initially in English to meet the objectives of the study and based around the five abilities of the population which influence access (Levesque, Harris and Russell, Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell2013) (supplementary file 1). Interview questions were translated from English into Urdu and pre-tested with Urdu-speaking Pakistani nationals, which allowed us to test the suitability of questions and preferred language translations. Interviews were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, therefore, following the initial testing stage, telephone interviews were carried out as participants indicated a preference to this method of contact due to unreliable internet connections, which made online interviews problematic.

All interviews were carried out by the primary researcher with a second observer present to allow for accurate translation from English into Urdu and Punjabi (and vice versa), and to minimize any potential researcher bias. Interviews ranged from 10 to 30 minutes in length. The interviews took place from 14th of July to 6th of September 2021. After 11 interviews, saturation was reached. To ensure no relevant information had been missed two additional interviews were conducted, which confirmed that no new information could be obtained, resulting in a total of 13 remote interviews conducted. Interview transcripts were audio recorded, and translated, and transcribed into English.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the qualitative interview data (Saldana, Reference Saldana2016). Line by line hand coding of each interview transcript was undertaken inductively by the primary researcher. This approach allowed for data familiarization and for data quality to be assessed by reviewing the variety of responses and elaboration of answers. An iterative process was adopted where codes were refined and updated as more interviews were coded. Codes were then combined to produce categories. Themes and sub-themes were then produced.

Quantitative phase

Survey design

The survey was designed based on the outcomes from phase one of the study (supplementary file 2). The online survey consisted of 45 questions, beginning with closed-ended questions to obtain demographic information from participants. This was followed by questions (some of which adopted a Likert scale) exploring the participants’ knowledge of eye health, journey to the eye care provider, cost of eye care, and finally the participants’ overall experience with eye care services was explored, ending with an open-ended question and free text box for the participant to add any additional comments regarding their experience with eye care services in Pakistan.

Maintaining the overall data capture capabilities of the survey, a very slightly modified version of the survey was used for individuals who presented in-person to one of the two hospital survey sites. The slight modification was necessary to reflect the in-person nature of the data collection. The survey was split into two parts to better capture participants’ experiences with the facility they were presently visiting as well as previous eye care experiences. To ensure consistency and reliability of the two survey versions, both designs were piloted amongst five Pakistani nationals (these results were not included in the final dataset or analysis). This stage proved useful as it allowed for minor adjustments to the wording of some questions.

Data collection

A version of the survey was made available online, in Urdu script, for the general public in Pakistan to access from 5th November 2021 to 30th March 2022. Survey data was collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools (Harris et al, Reference Harris, Taylor, Thielke, Payne, Gonzalez and Conde2009; Harris et al, Reference Harris, Taylor, Minor, Elliott, Fernandez, O’Neal, McLeod, Delacqua, Delacqua, Kirby and Duda2019). Accessing the survey online required participants to have access to a device with an internet connection. The participants also needed to be literate. To ensure widest possible participation, we identified two eye hospitals in Pakistan where hard copies of the survey were handed out. Interviewers were at hand locally to conduct the surveys face-to-face with illiterate participants. These two sites included: Al-Shifa Trust Eye Hospital, Rawalpindi, and a government hospital in Chakwal.

Sample size

Sample sizes were determined based on expected heterogeneity of population groups at selected survey sites (Hibberts et al., Reference Hibberts, Johnson and Hudson2012). Al-Shifa Trust Eye Hospital is one of the largest eye hospitals in the country, with some participants, from phase one, reporting travelling up to four hours to reach this hospital. We can therefore assume heterogeneity amongst the population will be higher for this location, and a sample size of 30 participants was set as a baseline. In contrast, the government hospital serves local populations in neighbouring villages with a relatively homogenous population, requiring a smaller sample, which was set at 15 participants. The surveys were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore due to decreased activities at the hospitals, these sample sizes were deemed reasonable. The online dissemination of the survey aimed to target a variety of participants across Pakistan; therefore, a sample size of 100 participants was set.

Data analysis and statistical methods

Using outcomes of our earlier work and to allow for a comprehensive exploration of the relationships between variables, assumptions were formulated to identify relationships between variables and outcomes as suggested by the qualitative interviews (phase one) and literature (Malik et al., Reference Malik, Strang, Campbell and Jonuscheit2022). Supplementary file 3 provides the assumptions and their outcomes. Each assumption was tested through some form of robust statistical analysis.

The survey data was analysed through IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26). Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, adjusting if respondents had left an item blank. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD, median, and range. The Shapiro–Wilk test of normality was also conducted for continuous variables. Chi-squared tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, and the Kruskal–Wallis tests were employed. All factors (from chi-square test) found to be significant (p values <0.05) were included in a regression model (binary/multinomial), as they were more likely to add to the improvement in prediction of the logits (Smith, Reference Smith2018; Kwak and Clayton-Matthews, Reference Kwak and Clayton-Matthews2002; Chatterjee and Hadi, Reference Chatterjee and Hadi2012). All independent variables were entered simultaneously (forced entry approach), and the model fit was assessed. All regression models presented in the study, demonstrated a good model fit through assessment of chi-square values (p-value <0.05) and the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (p-value ≥0.05) (Field, Reference Field2018; Laerd Statistics, 2017). Content analysis was used to analyse written data generated from the free text box at the end of the survey. An inductive approach to coding was utilized, which allowed for open coding (Elo and Kyngäs, Reference Elo and Kyngäs2008). Codes describing similar concepts were then aggregated to form categories.

Integration of qualitative and quantitative outcomes

The integration of both qualitative and quantitative data occurred initially when qualitative outcomes from phase one were built upon by the development of a survey tool for phase two, and again at the reporting level through a joint display. In order to determine coherence between qualitative and quantitative findings the fit of data integration was assessed, resulting in four possible outcomes 1) Confirmation: findings from both phases agree with one another 2) Complementarity: findings from both phases show different, non-conflicting conclusions 3) Expansion: findings from both phases expand insights of the topic of interest (by addressing different aspects of the same topic or describing complementary aspects of the same topic) 4) Discordance: findings from both phases conflict/disagree with one another (Fetters, Curry & Creswell, Reference Fetters, Curry and Creswell2013; Nollett et al., Reference Nollett, Bartlett, Man, Pickles, Ryan and Acton2019).

Results

Demographic factors

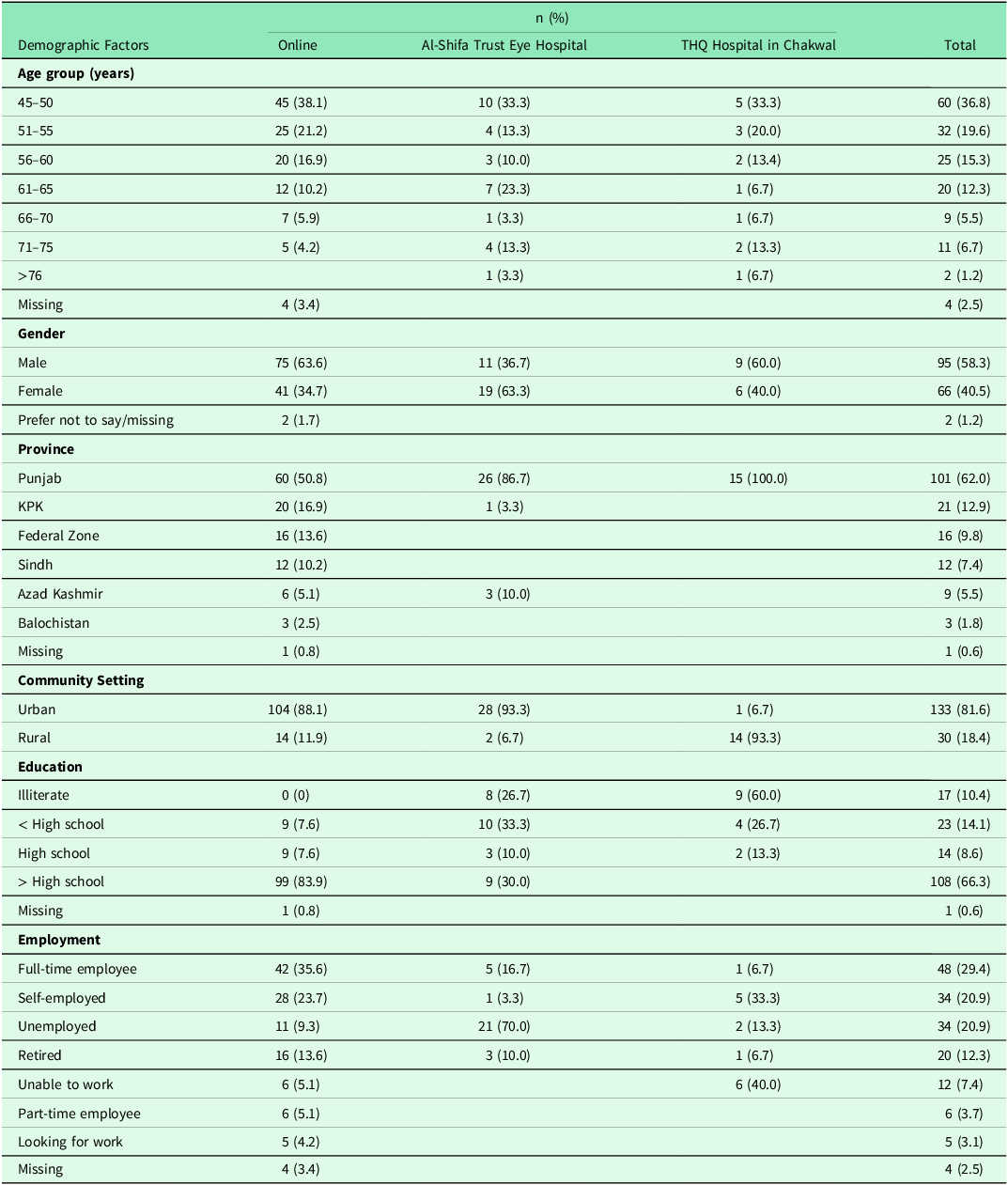

Thirteen participants took part in phase one (qualitative interviews) and had a mean age of 60 years old (± 10) with 54% male. The majority (9/13) resided in the Punjab province, with 2/13 from Sindh, and 1/13 in both KPK and the federal capital territory, with 54% reporting that they lived in a rural area. In (quantitative) phase two, a total of 163 participants responded to the survey, either taking part online or in-person at one of the two physical study sites. Of these, 58% were female and lived predominantly in urban areas (82%). Most participants resided in the province of Punjab (62%). A breakdown of participant demographic factors for each of the three survey sites is provided in Table 2. Full survey results can be found in supplementary file 4.

Table 2. Demographic factors for each of the three survey sites

Qualitative results

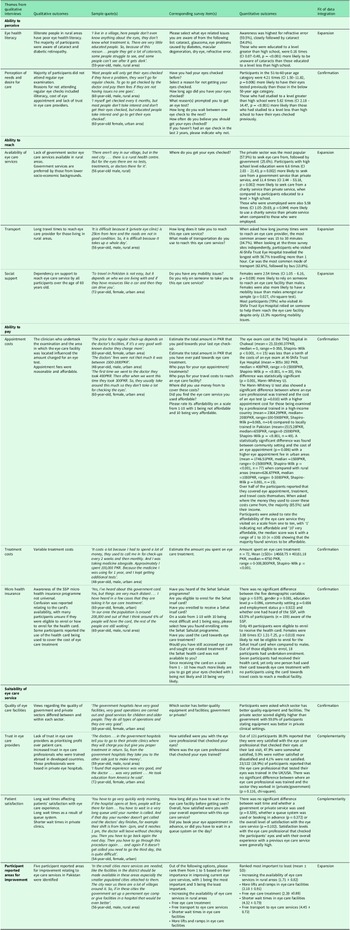

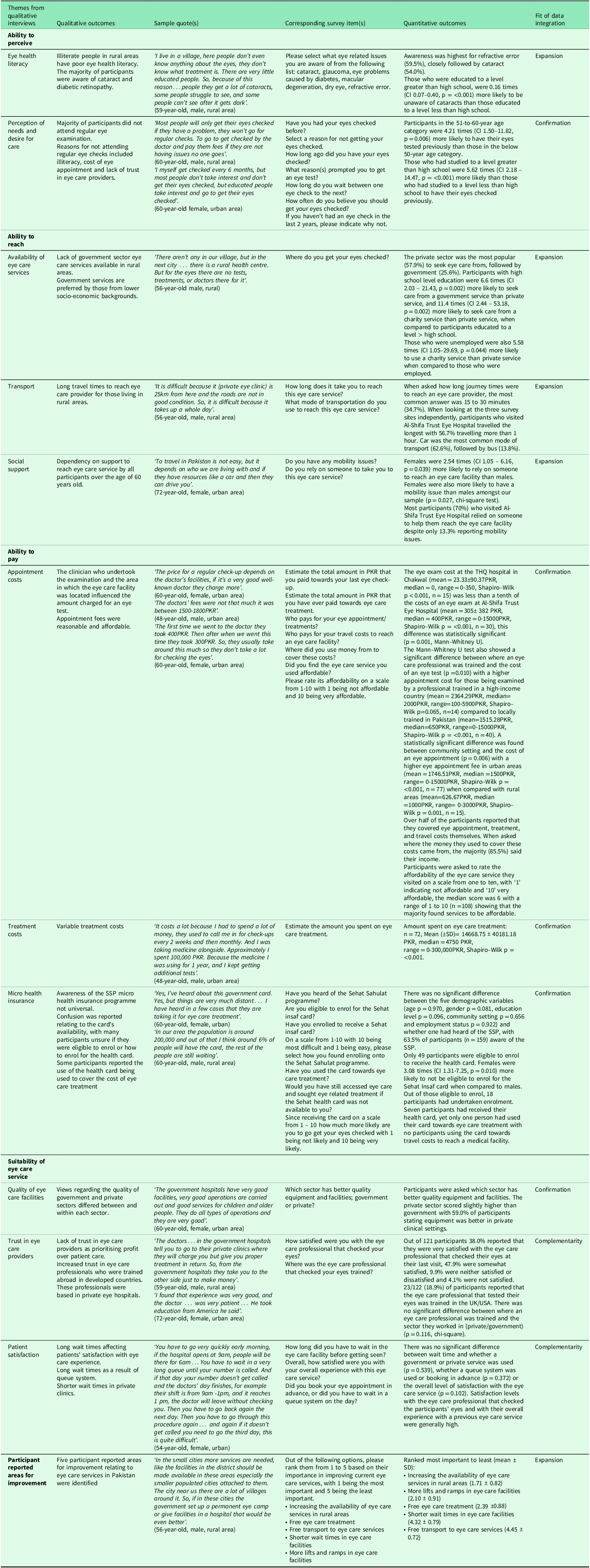

Following analysis of the thirteen interviews in phase one, a total of five themes emerged along with eleven sub-themes. The first three themes (i) ability to perceive; (ii) ability to reach; and (iii) ability to pay are based on Levesque, Harris and Russell, (Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell2013) demand side abilities affecting accessibility. The fourth theme suitability of eye care service explores the quality of eye care services, patient satisfaction and patients trust in eye care providers, and the fifth theme reports on areas needing improvement as reported by the participants. These themes and sub-themes helped to formulate corresponding survey items used in phase two (Table 3).

Table 3. Joint display of qualitative and quantitative data. Emerging themes and sub-themes with overarching outcomes and sample quotes from phase one are presented alongside corresponding survey items, significant results from logistic regression/Mann–Whitney U tests and an assessment of fit of data integration

Content analysis

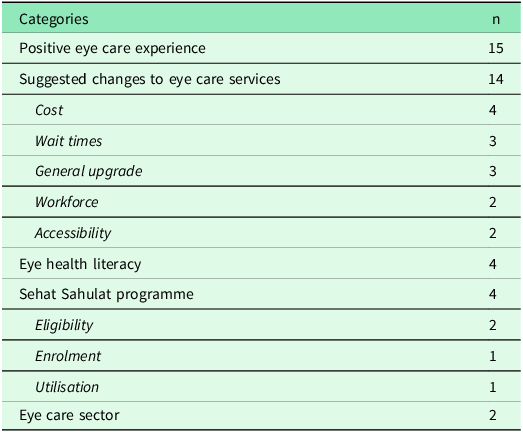

Thirty-four participants utilized the free text box. The resulting five categories identified through content analysis were: positive eye care experience, suggested changes to eye care services, eye health literacy, SSP, and eye care sector (Table 4). The most cited category was positive eye care experience, participants noted that they were satisfied with their eye care experience, however no specific details were shared as to what aspects of their eye care journey created this positive outcome. Within the category ‘suggested changes to eye care services,’ four participants commented on the need for free examinations and/or treatment. Three participants described long wait times, with one stating that long wait times were the reason they did not return for another eye exam. Three participants also commented on eye care facilities needing upgrades. While two participants discussed the need for more well-trained staff at eye care facilities and a further two participants commented on the need for nearby, easily accessible eye care services. Four participants provided comments demonstrating their understanding of the importance of eye health. The SSP also received comments detailing confusion surrounding eligibility for the programme, enrolling to receive a health card, and utilization of the health card. Comments relating to eye care sector were made by two participants, with one detailing that the equipment in government hospitals seems good but they are unsure if they are ‘properly used and maintained’.

Table 4. Frequency of categories and sub-categories identified through content analysis of participants additional comments on experience with local eye care services

Discussion

This mixed methods study has explored the experiences of people aged 45 years and older, with accessing eye care services in Pakistan. Overall, this study provides detailed evidence and novel insight from users of eye care. The outcomes of our study confirm that considerable barriers exist including illiteracy, long travel times, female gender, older age, mobility issues, and cost all limiting access to eye care in Pakistan. Awareness surrounding use of the SSP was poor, with the programme seldom used towards eye care costs.

The first barrier identified related to a person’s eye health literacy level. Previous literature also identified poor eye health literacy as a barrier to accessing eye care (see Safi et al., Reference Safi, Safi, Hafezi-Moghadam and Ahmadieh2018; Tatham, Weinreb & Medeiros, Reference Tatham, Weinreb and Medeiros2014; Cassum et al., Reference Cassum, Cash, Qidwai and Vertejee2020; Jalal & Younis, Reference Jalal and Younis2014; Itrat et al., Reference Itrat, Taqui, Qazi and Qidwai2007; Qureshi, Reference Qureshi2012; Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Nadeem, Memon, Soofi, Madhani, Karim, Mohammad and Bhutta2022). Within our sample many participants believed that if they were asymptomatic, there was no reason to schedule an eye exam. This highlights the lack of knowledge surrounding the importance of routine eye examinations and generally asymptomatic eye conditions in their early stages, such as glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy. For both conditions, it has been shown that routine asymptomatic examinations allow for earlier detection and treatment, thus reducing the likelihood and impact of visual impairment (Safi et al., Reference Safi, Safi, Hafezi-Moghadam and Ahmadieh2018; Tatham, Weinreb & Medeiros, Reference Tatham, Weinreb and Medeiros2014).

The next major barrier, impacting access to eye care, was the participant’s ability to reach an eye care provider. While this aspect is likely to vary and be dependent on geographical and socioeconomic attributes, it became evident that people living in rural areas in Pakistan struggled to travel long distances to reach secondary and tertiary eye care facilities in urban areas. Long travel distances for people living in rural areas to access eye care services have also been reported in the literature as a barrier to timely eye treatment in both Baluchistan and Sindh provinces (Jadoon et al., Reference Jadoon, Shah, Bourne, Dineen, Khan, Gilbert, Foster and Khan2007; Lane et al., Reference Lane, Lane, Abbott, Braithwaite, Shah and Denniston2018). Transport was also an issue for those who could not drive and had to rely on others to take them to an eye care provider. Due to the strong family support system in Pakistan this duty would usually fall to a member of their family, requiring them to take time away from their work to provide support for their family member (Cassum et al., Reference Cassum, Cash, Qidwai and Vertejee2020; Jalal & Younis, Reference Jalal and Younis2014; Itrat et al., Reference Itrat, Taqui, Qazi and Qidwai2007; Qureshi, Reference Qureshi2012). Females were also more likely to require support to reach an eye care facility. Gender discrimination is present in various aspects of Pakistani culture, as authority over family decisions and finances is usually given to male heads of household, limiting access to healthcare for females (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ali, Nadeem, Memon, Soofi, Madhani, Karim, Mohammad and Bhutta2022; Anwar, Green & Norris, Reference Anwar, Green and Norris2012) though, in phase two of our study, females were more likely to have mobility issues, which may have influenced this outcome.

Exploring participant views on eye care providers has helped improve understanding of the population’s perceptions of this workforce and how it may influence their decision on which eye care services to access. Participants preferred eye care providers who had received their training abroad because they felt they received a superior examination from such individuals due to the higher level of quality of training and knowledge associated with degrees obtained in developed countries. Some participants showed a lack of trust in eye care providers as they felt they prioritized generating a profit over the patient’s needs. This therefore negatively impacted their decision to seek eye care.

Another key and novel aim of this study was to investigate how access of eye care services is influenced by economic aspects including the SSP. When discussing cost as a barrier to access of eye care services, participants largely felt that services were affordable and they covered any associated costs themselves. However, cost of treatment, for example, for cataract surgery varied depending on the type of intraocular lens selected and the ophthalmologist carrying out the surgery and in some instances proved to be costly. It was observed that people from lower socio-economic backgrounds struggled to afford services provided by the private sector, and subsequently sought care from government and charity services. This suggests that cost remains a barrier to uptake of eye care services in Pakistan, with particular emphasis on cost of cataract surgery (Haider, Hussain & Limburg, Reference Haider, Hussain and Limburg2003; Anjum et al., Reference Anjum, Qureshi, Khan, Jan, Ali, Ahmad and Khan2006; Jadoon et al., Reference Jadoon, Shah, Bourne, Dineen, Khan, Gilbert, Foster and Khan2007; Lane et al., Reference Lane, Lane, Abbott, Braithwaite, Shah and Denniston2018).

Findings from part one of the study found the overall influence of the SSP on eye care service utilization to be low. This was also confirmed in part two of the study as only one participant had used the Sehat Insaf card towards eye care treatment. Low utilization of the SSP with regard to general healthcare has also been reported in previous studies (Cheema et al., Reference Cheema, Zaidi, Najmi, Khan, Kori and Shah2020; Habib & Zaidi, Reference Habib and Zaidi2021). A reason given for low utilization is that the Sehat health card can only be used at a select few facilities which meet a certain criterion, therefore people using the programme have to seek out facilities which accept it. Moreover, the SSP does not cover primary healthcare services or patients who visit outpatient departments (OPD). As a result, its use in ophthalmology departments is limited as most patients are managed in the OPD (McDonald & Iordanous, Reference McDonald and Iordanous2022). However, all in-patient services are covered by the SSP, allowing the SSP to be used for certain eye related surgeries (i.e. cataract, trabeculectomy, and so on) within ophthalmology departments (Morgan and International Labour Organisation, Reference Morgan2019).

The Sehat Insaf card can also be used to cover travel costs to reach a medical facility, yet no participants had claimed this. Although our survey did not investigate how long participants had held the card for, and as the scheme is relatively new, they may not have had an opportunity to utilize it to its full potential. Since dissemination of the surveys between November 2021 and March 2022, eligible health facilities can now assess patients under the SSP without them needing to enrol to receive the Sehat Insaf card (Sehat Sahulat Programme, 2022; Health Department Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 2021; Hasan et al., Reference Hasan, Mustafa, Kow and Merchant2022). Therefore, it is possible that more patients may be inclined to utilize the SSP towards eye care as accessibility to the programme is increasing due to on-going roll out and wider spread eligibility.

With this study, we are hoping to provide useful insight into the issues people experience when accessing eye care. Listening to patients and service users is essential to enable decision makers and health departments to further improve clinical services and work towards achieving UHC. When asked to rank the five areas of improvement, participants ranked ‘increasing the availability of eye care services in rural areas,’ as their key priority. Healthcare planners are already working these aspects and Pakistan’s national health policy of 2001 recognized an urban bias in the health sector and aimed to address it by expanding public healthcare services to rural areas (Ministry of Health and Government of Pakistan, 2001). The responses our participants provided indicate that resolving access barriers is ongoing and requires a long-term view and continued funding efforts (Naz, Ghimire & Zainab, Reference Naz, Ghimire and Zainab2021).

Strengths and limitations

The use of a mixed methods approach allowed for utilization of both qualitative and quantitative methods which allows for increased strength than each of these approaches alone (Creswell & Plano Clark, Reference Creswell and Plano Clark2011). Part one identified a wide range of barriers, while part two demonstrated the magnitude of each barrier. The study also operationalized the framework to healthcare access by Levesque, Harris & Russell, (Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell2013). The study focused on the demand side features of this model and also allowed for new themes to arise through inductive thematic analysis, thus providing comprehensive new evidence on eye care service use in Pakistan.

Non-random sampling techniques were used due to limited accessibility and time constraints (Etikan, Musa & Alkassim, Reference Etikan, Musa and Alkassim2016). Within our sample slight over-representation within the data set occurred, for example the majority of participants were educated to a level greater than high school. Individuals with a higher level of education are more likely to understand research activities and participate (Nirmalan et al., Reference Nirmalan, Katz, Robin, Krishnadas, Ramakrishnan, Thulasiraj and Tielsch2004). We mitigated this by undertaking face-to-face surveys at the two hospital sites in the Punjab province, obtaining a more balanced sample and valuable data. The addition of face-to face surveys strengthened the validity and completeness of data collection as an interviewer was at hand to remove any ambiguities surrounding questions. It was also found that fewer questions were skipped in the face-to-face surveys when compared with the online survey. However, due to time constraints we were unable to check the interviewer’s inter-rater reliability. While providing novel evidence on barriers to eye care use, access, and costs, there remains considerable variability in geographic structure and socioeconomic capacity across Pakistan. Therefore, any generalising of the results to the whole country should be undertaken with caution. Furthermore, the SSP was not available at the government hospital in Chakwal at the time of the survey. Although the hospital provides free healthcare services to patients, this may have influenced their reliance on the SSP for eye care needs. This presents a limitation of the study, as the unavailability of the SSP at the facility could have impacted participants’ responses to questions related to the programme. Future research should consider comparing facilities that accept SSP with those that do not to gain deeper insights into the programme’s role in improving eye care accessibility.

Representation was achieved in all provinces apart from Gilgit–Baltistan, and the majority of responses were from the Punjab province despite best efforts to recruit more widely. However, the recruitment success is showing a similar distribution of results from provinces compared to other studies investigating health seeking behaviour in Pakistan (Naz, Ghimire & Zainab, Reference Naz, Ghimire and Zainab2021; Anwar, Green & Norris, Reference Anwar, Green and Norris2012). Reasons given for this unequal distribution include more densely populated provinces including the Punjab and Sindh provinces and more healthcare facilities in urban areas. Additionally, Pakistan has a diverse range of cultures and languages, primarily in rural areas across all provinces (Naz, Ghimire & Zainab, Reference Naz, Ghimire and Zainab2021). This could also have been a contributing factor, as our online survey was only available in Urdu, the national language of Pakistan and used for formal written communication. Future research could consider offering the survey in regional languages, based on the location of survey dissemination, to ensure better comprehension and inclusivity.

Participants were given the option to skip questions they did not want to answer in the survey. In order to minimize participants skipping questions a number of pre-designed categories were available for most questions to encourage the participant to select an answer for each question. This approach was successful with a high response rate for such questions compared to a lower response rate where free text options were given. However, the use of these categories in some instances may have caused some unintentional, but unavoidable, bias onto participants, that is, when exploring participants eye health literacy and practices. Moreover, participants were asked to rank statements covering five areas for improvement, many misunderstood the question and rated each statement individually on a scale from one to five, resulting in a lower number of responses analysed (n = 31).

Due to the predominantly remote nature of data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic, detailed information on participants’ eye health, such as visual acuity and existing eye conditions, was not gathered. However, some participants voluntarily shared insights about their personal eye health during qualitative interviews, providing a glimpse into their knowledge and eye care-seeking behaviours. This suggests that access to eye care may be influenced by an individual’s specific eye health condition(s). Future research can aim to measure these factors for a more comprehensive understanding of participants’ eye care behaviours.

A final potential limitation is that we did not directly assess whether other health conditions impaired access to eye care facilities. For example, patients with dementia may experience limited access to eye care services due to increased social isolation or inappropriate care. It has been noted that certain health conditions including depression, dementia, cardiovascular disease, and lung cancer are associated with an increased risk of vision impairment (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Ramke, Marques, Bourne, Congdon, Jones, Tong, Arunga, Bachani, Bascaran and Bastawrous2021; Luo et al., Reference Luo, He, Guo, Chen, Li and Zheng2018; Mohile et al., Reference Mohile, Fan, Reeve, Jean-Pierre, Mustian, Peppone, Janelsins, Morrow, Hall and Dale2011; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Wu, Lin and Lin2017; Crews et al., Reference Crews, Chou, Sekar and Saaddine2017). Such conditions also have a higher prevalence amongst the elderly cohort (Crews et al., Reference Crews, Chou, Sekar and Saaddine2017). Therefore, it is important that future research considers the effect of certain health conditions on access to eye care.

Implications for practice

The burden of eye diseases in Pakistan is expected to rise as life expectancy rises and the population ages (Dineen et al., Reference Dineen, Bourne, Jadoon, Shah, Khan, Foster, Gilbert and Khan2007; Najam & Bari, Reference Najam and Bari2017). Inadequate access to eye care services will result in a larger backlog of people who need but do not receive eye care. The current study has identified and quantified barriers surrounding access to a variety of eye care services in Pakistan, covering all sectors and types of services from tertiary care eye hospitals in urban cities to eye camps in rural villages. This provides eye care service providers with information relating to barriers that need to be addressed, to improve accessibility of their services. By improving access to eye care services for older age groups, the eye care sector will be better positioned to manage the increasing demand on services due to age-related eye conditions and thus contribute to the reduction of avoidable blindness. Additionally, cost was identified as a barrier to accessing eye care in Pakistan. This study provides valuable insights into the low awareness and utilization rates surrounding the SSP and eye care. Further evaluations and improvements to the programme are critical in the effort to provide affordable eye care to all citizens in the country. Future research can focus on barriers and enablers to accessing eye care in rural locations across the country as the language and cultural norms vary between areas. Therefore, exploring these areas may allow for culturally sensitive targeted interventions to improve access, which may be better accepted by such communities.

Conclusion

This mixed methods study has explored participants experiences accessing their local eye care services in Pakistan. Barriers to accessing eye care have been identified. Future efforts and initiatives should focus on continuing efforts to provide improvements to educating the public on eye health, increasing availability of secondary eye care services in rural areas, improving accessibility within eye care facilities, addressing gender disparities, and reducing costs associated with eye care treatments, potentially through advancement of the SSP. Most healthcare systems face challenges due to resources being scare, but despite these constraints, progress continues to be made.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423625100261.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. We would like to thank all participants who gave their time and shared their experiences. We would also like to thank Ghulam Shabbir, Farah Feroz, Khizzar Malik, Abda Malik, and Rahna Khan for aiding with translations and the recruitment process.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None

Ethical standards

All participants gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Glasgow Caledonian University School of Health and Life Sciences and given ethical approval for phase one on the 1st July 2021 (ref no: HLS/LS/A20/050), and approval for phase two was granted on the 12th November 2021 (ref no: HLS/LS/A21/003).