I think my light bulb moment was realising that a lot of obviously the reasons I felt unsafe was due to my past. I used to describe it as like a pit. This darkness all around me. Finding that light and opening doors to other people and actually letting people in to help you to then realise that you are actually safe and other people can make you feel safe, and you actually can feel safe in yourself as well, made me then start to have more lights, and then that pit got smaller and then eventually it was like a pothole, which I could just step out of. Rachel.

Introduction

Rachel believed that people wanted to hurt her, that everyone walking past her house was a potential danger, and sometimes that people were setting fire to her home. She mistrusted most people. Over the course of the Feeling Safe program (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Emsley, Diamond, Collett, Bold, Chadwick, Isham, Bird, Edwards, Kingdon, Fitzpatrick, Kabir and Waite2021) Rachel realized that her past trauma was a key driver of her fears. An alternative view was raised: that perhaps people could be trusted now. Over many months, Rachel practiced trusting people. She learned that she was safe. Her paranoia faded away. In other words, Rachel developed a sense of safety that functioned as a counterweight to her fears. Over time, the scales tipped and safety – rather than fear – became her dominant belief. Persecutory delusions, such as those experienced by Rachel are one of the most common difficulties in psychosis presentations (Lemonde et al., Reference Lemonde, Joober, Malla, Iyer, Lepage, Boksa and Shah2021; Collin, Rowse, Martinez, & Bentall, Reference Collin, Rowse, Martinez and Bentall2023; Pappa et al., Reference Pappa, Baah, Lynch, Shiel, Blackman, Raihani and Bell2025) but are all too often resistant to standard treatments. In this paper, we describe a way of understanding paranoia, of talking about it with patients – and of overcoming it.

What are persecutory delusions?

Persecutory delusions are strongly held, but incorrect, beliefs that others are deliberately trying to harm the person. That harm may, for instance, be psychological, social, financial, or physical. Such beliefs can produce extremely negative consequences. The attempt to deal with the perceived threat – for example, by withdrawing – can be highly disruptive to everyday life. Negative affect, especially anxiety and depression, but sometimes also anger, is common. Life can feel like a battle. Often, persecutory delusions are an extension of delusions of reference, in which people believe that others are talking about them behind their back or that messages are being sent to them, or of hallucinatory experiences such as hearing voices.

We conceptualize persecutory delusions as inaccurate threat beliefs that are attempts to make sense of events (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Garety, Kuipers, Fowler and Bebbington2002). They are the extreme end of a spectrum of paranoia in the general population. Many people have a few paranoid thoughts, and a few people have many paranoid thoughts (Bebbington et al., Reference Bebbington, McBride, Steel, Kuipers, Radovanoviĉ, Brugha and Freeman2013; Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Garety, Bebbington, Smith, Rollinson, Fowler and Dunn2005; Neidhart, Mohnke, Vogel, & Walter, Reference Neidhart, Mohnke, Vogel and Walter2024). This is unsurprising. Decisions about whether to trust or mistrust other people are an inescapable part of human cognition – after all, real dangers exist, people do bad things to others, and safety can seldom be completely guaranteed. Paranoia is what results when that decision-making skews excessively to the negative so that judgments are inaccurate (Freeman, Reference Freeman2016). In other words, it arises out of everyday risk estimation gone awry. Paranoia occurs transdiagnostically (e.g. Alsawy, Wood, Taylor, & Morrison, Reference Alsawy, Wood, Taylor and Morrison2015; D’Agostino, Monti, & Starcevic, Reference D’Agostino, Monti and Starcevic2019; Varghese et al., Reference Varghese, Scott, Welham, Bor, Najman, O’Callaghan and McGrath2011). In conditions such as anxiety and depression it has been found – most likely due to the negative effects on interpersonal relationships – to be a marker of poorer outcomes (Bird et al., Reference Bird, Fergusson, Kirkham, Shearn, Teale, Carr and Freeman2021; Wiedemann et al., Reference Wiedemann, Stochl, Russo, Patel, Ashford, Ali and Perez2024). Of course, paranoia can be an understandable reaction to events. Patients are more likely to live in difficult settings and experience hostility. A person can both have paranoia and face genuine threats. But ‘the dose makes the poison’. Too much paranoia – a high concentration – can create damaging effects. In persecutory delusions, the estimation of danger has become so dominant that the person feels extremely, and often debilitatingly, unsafe.

The weight of paranoia

I couldn’t not believe my beliefs. I was convinced about them…and because my beliefs became so loud and just dominated me, they weren’t helping me at all. Steve.

Why do persecutory beliefs become such a persuasive way of understanding events? Why does their voice drown out other perspectives? Our view is that they carry such weight because so many factors contribute to their existence and maintenance – though the number and relative influence of those factors will vary from person to person. This complexity is illustrated in our study of 22 cognitive and social causes of paranoia (Freeman & Loe, Reference Freeman and Loe2023). We found that all 22 causes were individually associated with paranoia, and in a combined model, 13 factors explained two thirds of the variance in paranoia. The 13 factors were: within-situation defense behaviors, negative images, negative self-beliefs, discrimination, dissociation, aberrant salience, anxiety sensitivity, agoraphobic distress, worry, less social support, agoraphobic avoidance, less analytical reasoning, and alcohol use. Another illustration is the wide range of other factors researchers are examining to understand paranoia, including aberrant belief updating (Sheffield, Suthaharan, Leptourgos, & Corlett, Reference Sheffield, Suthaharan, Leptourgos and Corlett2022; Barnby, Mehta, & Moutoussis, Reference Barnby, Mehta and Moutoussis2022; Rossi-Goldthorpe et al., Reference Rossi-Goldthorpe, Silverstein, Gold, Schiffman, Waltz, Williams and Corlett2024), social group threat detection (Raihani & Bell, Reference Raihani and Bell2019), amplified threat processing and impaired emotion regulation (Lincoln, Sundag, Schlier, & Karow, Reference Lincoln, Sundag, Schlier and Karow2018; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Lefebvre, Conring, Gangl, Nadesalingam, Alexaki and Stegmayer2022), social isolation (Contreras et al., Reference Contreras, Valiente, Vázquez, Trucharte, Peinado, Varese and Bentall2022; Fett et al., Reference Fett, Hanssen, Eemers, Peters and Shergill2022), early life adversity (Bentall, Wickham, Shevlin, & Varese, Reference Bentall, Wickham, Shevlin and Varese2012), PTSD symptoms (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, O’Driscoll, Steel, Van Der Gaag and Van Den Berg2021; Panayi et al., Reference Panayi, Peters, Bentall, Hardy, Berry, Sellwood and Varese2024), and attachment style (MacBeth, Schwannauer, & Gumley, Reference MacBeth, Schwannauer and Gumley2008; Sood, Carnelley, & Newman‐Taylor, Reference Sood, Carnelley and Newman‐Taylor2022). At a neurobiological level of explanation, overactivation and hyperconnectivity of the amygdala – reflecting amplified detection of salience and threat and insufficient top-down regulation – have been repeatedly linked to paranoia (Pinkham et al., Reference Pinkham, Liu, Lu, Kriegsman, Simpson and Tamminga2015; Fan et al., Reference Fan, Klein, Bass, Springfield and Pinkham2021; Pinkham et al., Reference Pinkham, Bass, Klein, Springfield, Kent and Aslan2022; Walther et al., Reference Walther, Lefebvre, Conring, Gangl, Nadesalingam, Alexaki and Stegmayer2022).

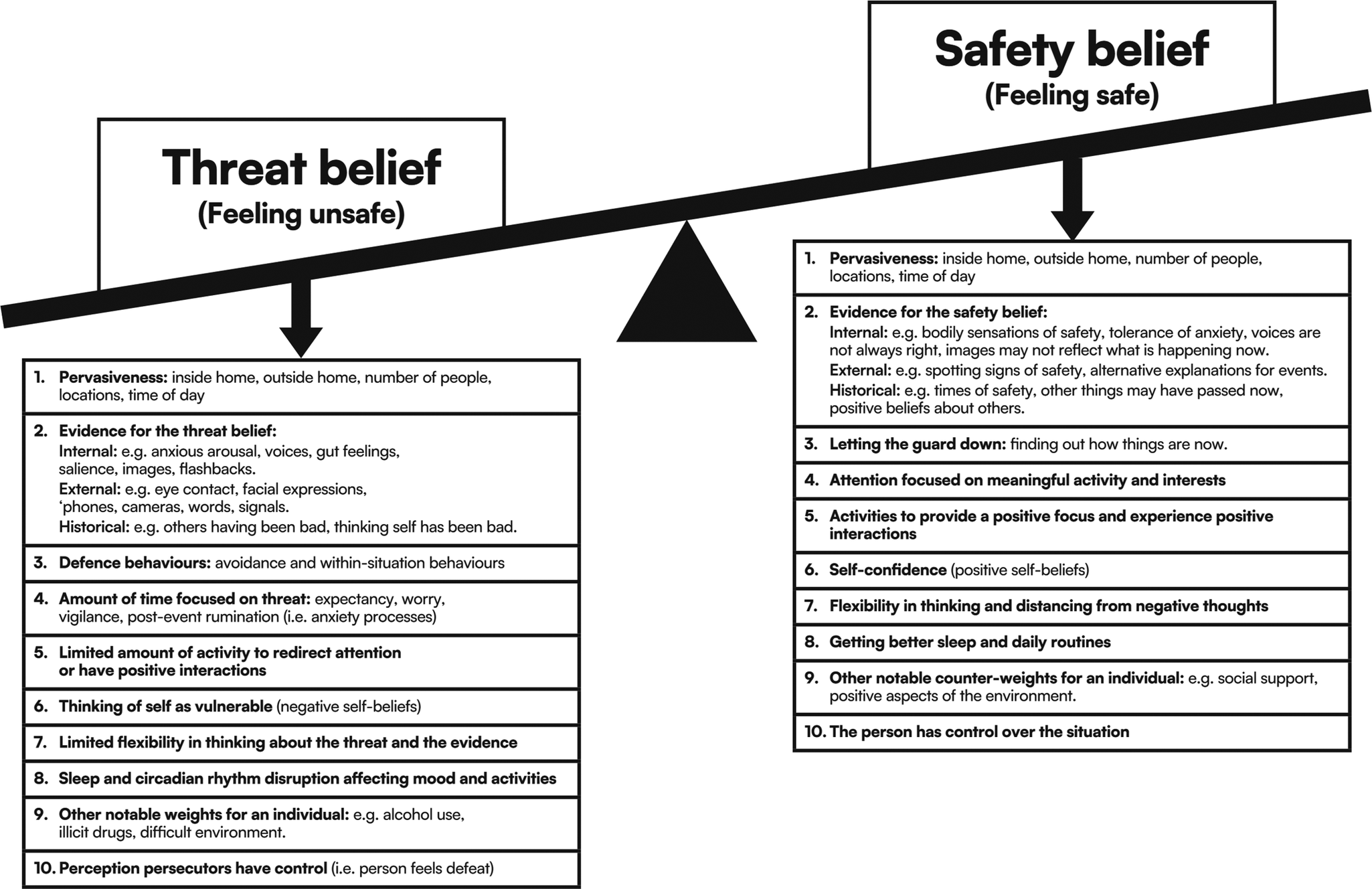

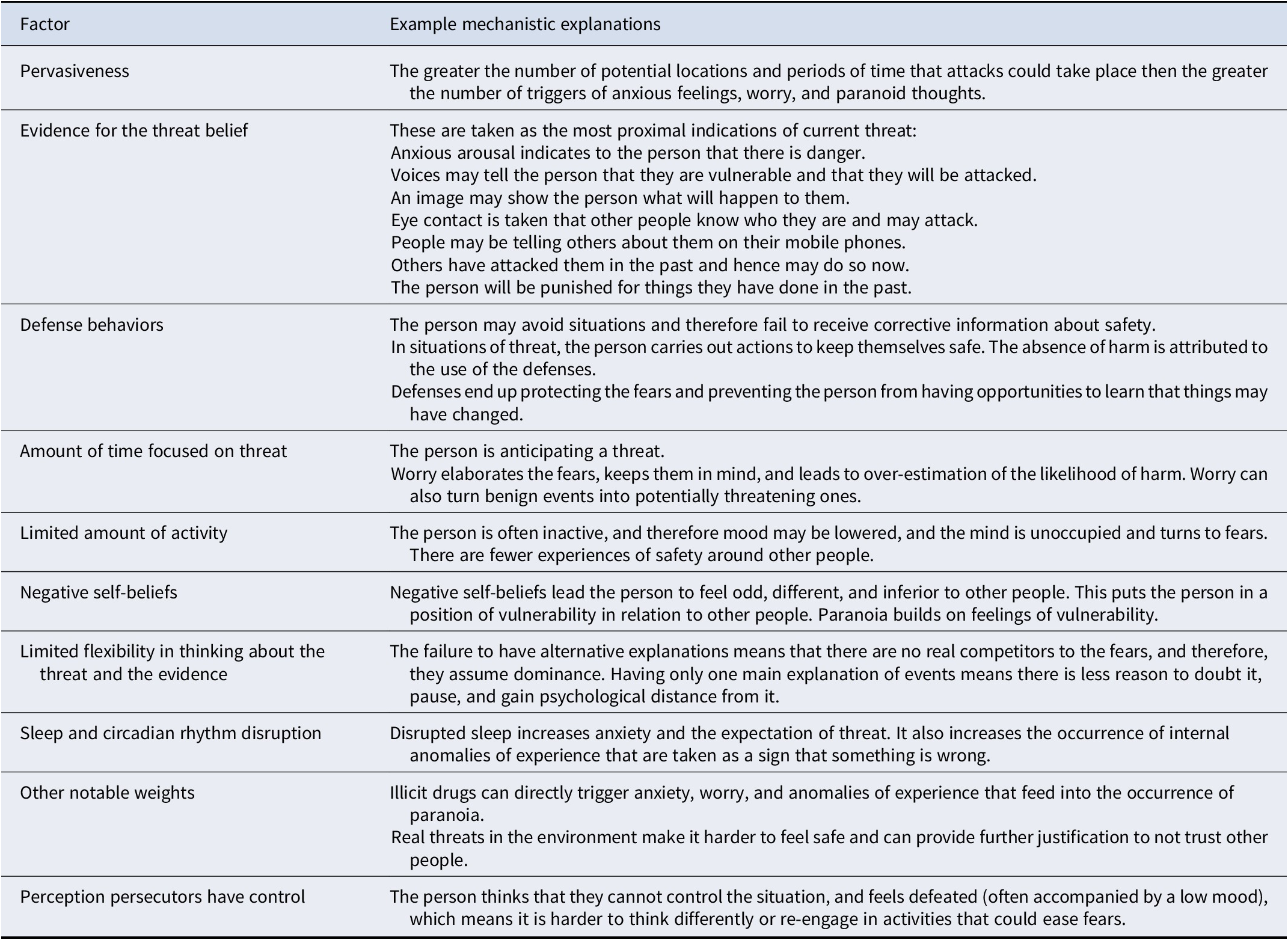

In our counterweight model of paranoia, we list 10 categories of factors that provide weight to the inaccurate threat belief (see Figure 1 and online Supplementary materials Figure S1). The focus is on factors that are tractable to intervention and that patients want treated (Freeman, Taylor, Molodynski, & Waite, Reference Freeman, Taylor, Molodynski and Waite2019). The factors are designed to accommodate the influence of past experience on current processing (e.g., trauma may have had effects on, for example, self-beliefs, beliefs about others, anxious arousal, and imagery). The model is designed to provide structure to a clinical assessment of persecutory delusions and to do so from the patient’s perspective. The conversation in that assessment starts at the belief itself. We discuss how much feeling unsafe pervades the person’s life, and the types of direct evidence supporting that feeling. Often, the person’s threat belief is fueled by the physiological effects of anxiety. The anxiety can sometimes be accompanied by negative images (Kingston et al., Reference Kingston, Dunford, Chau, So and Pile2025; Morrison et al., Reference Morrison, Beck, Glentworth, Dunn, Reid, Larkin and Williams2002). Sometimes the person hears a voice telling them that they are vulnerable and will be attacked, which is then believed (Sheaves et al., Reference Sheaves, Johns, Loe, Bold, Černis and Freeman2023). The long shadow of negative past events is often perceptible. Such events may involve things others have done to the person or actions the person feels guilty about. We then move on to a discussion of the defense behaviors – safety-seeking behaviors (Salkovskis, Reference Salkovskis1991) – that the person adopts to reduce the likelihood of harm. Often, the person avoids situations they find threatening. If they do enter such situations, they use subtle strategies for protection (e.g., rushing, choosing a quiet time of day, making themselves inconspicuous). Next, we assess how much the person is anticipating and thinking about threat, and, conversely, the time they spend in positive activities, such as social contact. Most patients devote considerable time to worrying about the threats and much less to other activities. We then broaden out into a discussion of how the person may feel inherently vulnerable in regards to other people due to negative self-beliefs (Collett, Pugh, Waite, & Freeman, Reference Collett, Pugh, Waite and Freeman2016; Humphrey et al., Reference Humphrey, Bucci, Varese, Degnan and Berry2021; Waite et al., Reference Waite, Diamond, Collett, Bold, Chadwick and Freeman2023). We may note that it is hard for the person to view events in different ways, and that the situation is not helped by disruption to sleep and routines (Freeman & Waite, Reference Freeman and Waite2025). Typically, we conclude by exploring how much control the person feels the persecutors possess. This signposts that we want the person themselves to have greater control. In sum, the process we follow in the assessment allows us to build a personalized picture of the individual’s situation. It gives us a tailored appraisal of the weights pulling the person’s understanding towards paranoia. Descriptions of the mechanistic links between the factors and paranoia are provided in Table 1.

Figure 1. A counterweight model of paranoia.

Table 1. Examples of mechanistic pathways to severe paranoia

Overcoming paranoia: counterweights

Nobody can tell you, you’ve got to learn yourself. I found out a) it was okay b) there was life outside my house that I wanted to be part of and c) people smiled. Gill.

Many patients lack alternative explanations for the delusion and its associated evidence. If they do have alternative ideas, these may be unpalatable and limited in explanatory power (e.g., ‘mental illness’, ‘brain damage’) (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Garety, Fowler, Kuipers, Bebbington and Dunn2004). We therefore provide a series of counterweighting beliefs or behaviors that are positive; can coexist with the person’s existing position; and if adopted will inherently tip the scales away from the persecutory fears. The primary counterweight is a belief that the person may be safe now. This is a position that does not dispute the past. And the counterweight can be even more circumscribed: that the person is safe enough now in certain places at certain times (to do things that they would like to do). Of course, absolute safety cannot be guaranteed for anyone, and certain environments at certain times can be dangerous. The development of safety is best learned from direct experience. Within an inhibitory learning framework of understanding (Craske et al., Reference Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek and Vervliet2014), the new learning of safety will constrain and dampen the old learning that others intend harm. Relatedly, the counterweight approach has similarities to a retrieval competition account of cognitive behavior therapy for emotional disorders, in which the principal mechanism of action of intervention is considered as ‘strengthening competitor representations in memory that are positive rather than negative in valence’ (Brewin, Reference Brewin2006). It is also consistent with the general reasoning literature: considering an alternative, accessible, and plausible explanation is more likely to debias judgements (Hirt & Markman, Reference Hirt and Markman1995; Wharton, Cheng, & Wickens, Reference Wharton, Cheng and Wickens1993; Sanna, Schwarz, & Stocker, Reference Sanna, Schwarz and Stocker2002; Hirt, Kardes, & Markman, Reference Hirt, Kardes and Markman2004).

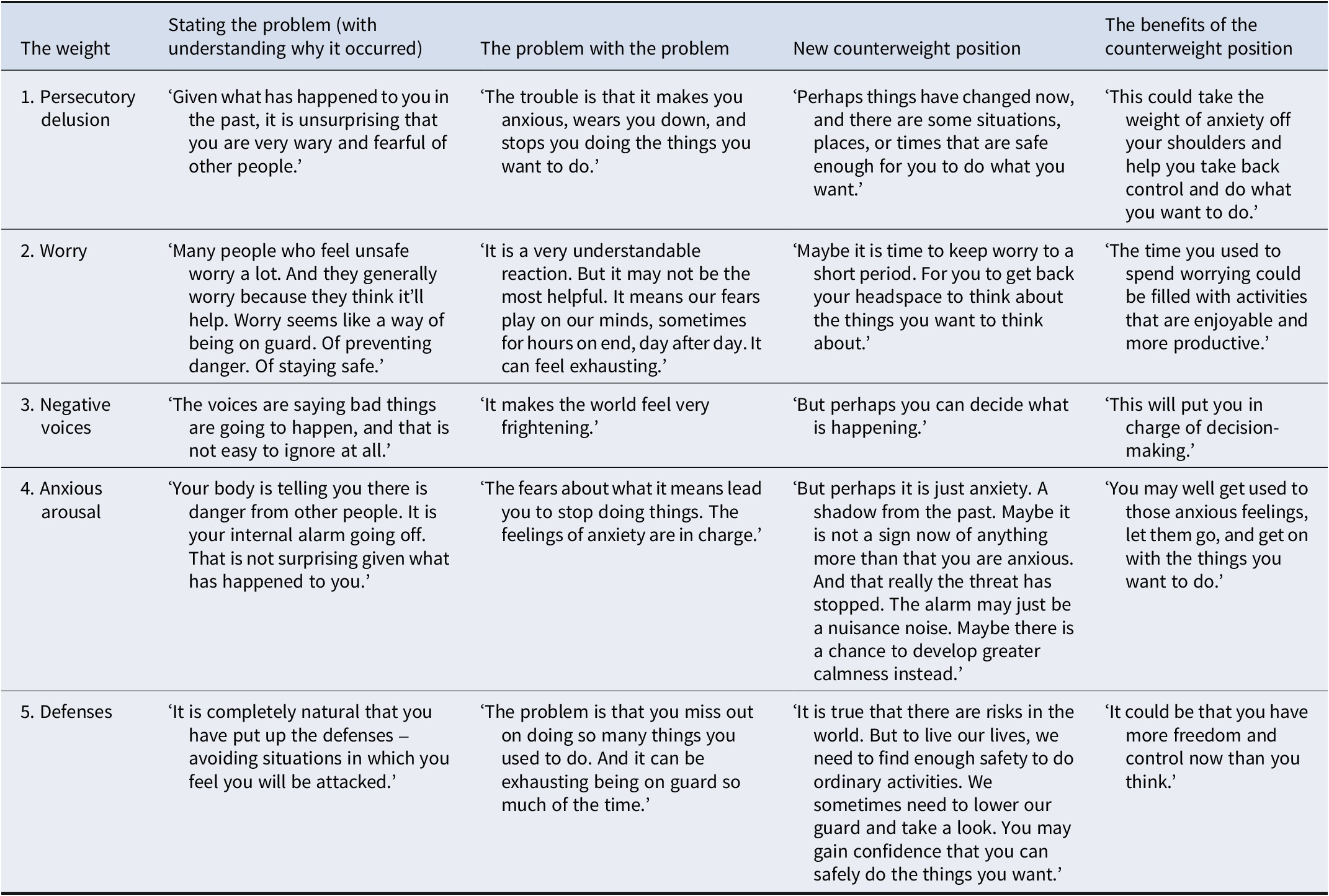

However, relearning safety can be extremely difficult when so many weights still pull in favor of the persecutory delusion. These weights can make even benign situations feel unsafe (e.g., ‘If I had not left early, I would have been harmed’, ‘I had an image of the harm they were going to do to me’, ‘Later I realized that the smile was because they were up to something’). Therefore, at least some of these weights must be lightened. Our framework for the introduction of counterweights is provided in Table 2. It is important to convey to the person that the existence of the particular weight is understandable – that it makes sense, for example, given their life experiences or as a response to their fears. But that forces a heavy burden upon them. A positive counterweight can then be introduced, and its potential benefits described. The merit of this approach is that many routes for treatment become evident. For example, increasing activities, sleeping better, building up self-confidence, looking for signs of safety, letting down one’s guard to find out how the world is now, learning to tolerate anxious feelings, letting oneself rather than the voices decide what is going on, and getting some distance from troubling thoughts. It is notable that the approach intrinsically introduces flexibility into thinking about difficulties because of the introduction of counterweights.

Table 2. Examples of how to pivot with patients to a counterweight

The model can be used to formulate a person’s difficulties with paranoia. Early in the intervention, we want to understand the weights pulling the person towards the delusion. But we then shift to identify and build up counterweights. A person with severe paranoia will typically need to follow several treatment routes, one at a time. But the counterweight approach typically identifies many options, allowing patient choice to be built into treatment provision. This approach generally produces a range of positive outcomes (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Emsley, Diamond, Collett, Bold, Chadwick, Isham, Bird, Edwards, Kingdon, Fitzpatrick, Kabir and Waite2021; Jenner et al., Reference Jenner, Payne, Waite, Beckwith, Diamond, Isham and Freeman2024). For some people, the weight of paranoia is lifted a little. For others, the change is enough to balance the scales. And sometimes the scales shift so dramatically in favor of safety that the burden of paranoia is lifted entirely.

Models are indispensable

A suitable model is essential for powerful psychological intervention. It allows us to identify treatment targets, share understanding with patients, and guide the focus of sessions. The counterweight model we describe here was developed to guide both psychological understanding and treatment, and underlies the face-to-face Feeling Safe program (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Bradley, Waite, Sheaves, DeWeever, Bourke and Dunn2016) and the guided online program Feeling Safer (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Isham, Freeman, Rosebrock, Kabir, Kenny, Diamond, Beckley, Rouse, Ahmed, Hudson, Sokunle and Waitein revision), both of which have shown strong treatment effects. For example, in a randomized controlled trial, Feeling Safe produced a large further reduction in persecutory delusions above an alternative psychological intervention delivered by the same therapists (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Emsley, Diamond, Collett, Bold, Chadwick, Isham, Bird, Edwards, Kingdon, Fitzpatrick, Kabir and Waite2021). Indeed, the principal counterweight (a feeling of safety) is signaled from the outset by the name of these programs. But an appropriate model alone is insufficient. Successful treatment requires other elements too. Elsewhere, we have described 10 key principles, including the use of counterweights, for developing psychological treatment for psychosis (Freeman, Reference Freeman2024). These include respect for patients, contributions from people with lived experience, and precise and rigorous treatment delivery. We also highlight the fundamental importance of collecting outcomes at each intervention session. We must be able to gauge whether a mechanistic target is being successfully addressed and whether there is improvement in the persecutory delusion. There is still work to be done on developing a comprehensive, patient-focused set of assessments to guide paranoia research and treatment. As we seek to improve the treatment of persecutory delusions, identifying further significant and tractable intervention weights and counterweights, that set of assessments must evolve accordingly.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291725001242.

Acknowledgments

We thank the individuals who agreed to provide quotes for this article.

Funding statement

The work was funded by a NIHR Programme Grant for Applied Research (PGfAR) (reference: NIHR204013). It is also supported by the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). DF and FW are supported by the NIHR Oxford Health BRC. DF is an NIHR Senior Investigator. FW is funded by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Doctoral Fellowship (102176/B/13/Z). LI is funded by a NIHR Development and Skills Enhancement Award (NIHR303752). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.