Introduction

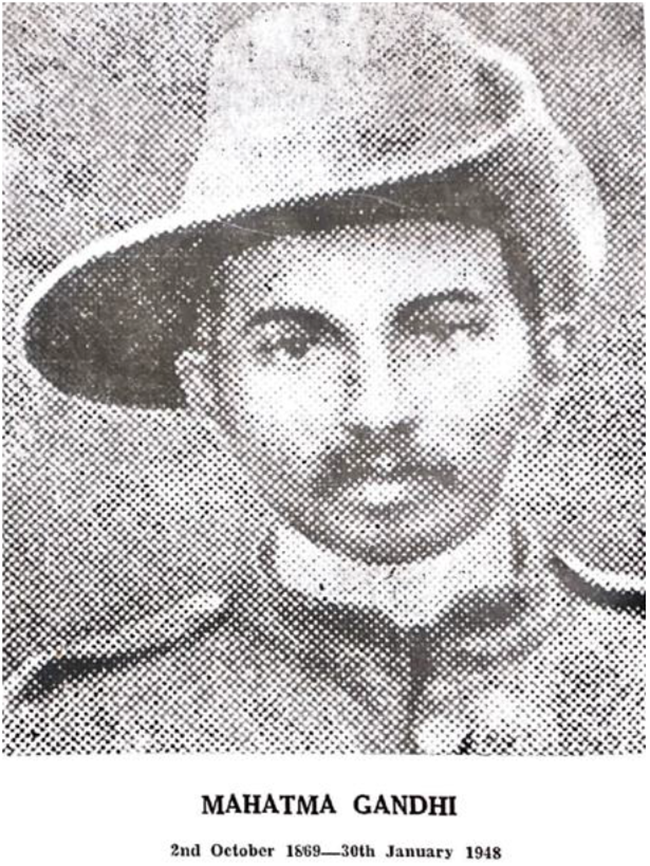

The inception of Indian statecraft is often associated with Gandhian ideals of non-violence and the embrace of a Nehruvian focus on Third-Worldist anti-colonial solidarity in the face of superpower rivalry in the aftermath of Independence. Yet an image from a 1948 volume of the United Services Institution (USI) Journal unsettles this narrative (Figure 1). The image pictures a young Mohandas Gandhi from 1906, when Gandhi, according to the caption ‘raised an Indian Ambulance corps during the Zulu rebellion’.Footnote 1 ‘During the Boer war’, the caption notes, Gandhi ‘mustered an Ambulance Corps of 1,100, which included some 400 Indians’.Footnote 2 While the image appears alone and its intended purpose is left unsaid, it raises salient questions about how the emergent Indian state project is represented in relation to the violence of Western empire. The Natal Indian Ambulance Corps, which Gandhi founded, consisted of 300 free Indians and 800 indentured labourers. Gandhi’s valour and fighting with the Corps earned him many British medals and accolades. What might USI Journal’s attempt to reclaim Gandhi as imbricated in the exercise of colonial violence imply? In light of Gandhi’s own condescension towards ‘Untouchables’ in India, and espousal of anti-Black racism in Africa, this image betrays the complexity of the post-Independence Indian state – simultaneously anti-colonial and invested in the oppressive and racialised logics of colonialism. This image further offers a point of entry to reinvigorate the questioning of post/colonial rupture anew,Footnote 3 as well as interrogating the boundaries between different forms and categories of empireFootnote 4 through the lens of counter-insurgency. In this article, we centre the discourse and praxis of counter-insurgency to interrogate how post-Independence India remains wedded to, and reproduces, colonial logics.

Figure 1. Photo of Mahatma Gandhi in USI Journal, 1948.

The word ‘counter-insurgency’ connotes particular geographies: the (supposed) peripheries in the Global South where powerful Western empires and states wage various ‘small’, ‘unconventional’, ‘irregular’, or ‘low-intensity’ campaigns against colonised subjects. British anti-communism in Malaya, the British Mandate in Palestine, US campaigns in the Philippines and in Vietnam all fit within this frame. Since the onset of the ‘war on terror’, there has been a wide-ranging discussion about the ‘long’, even ‘forever’ counter-insurgency wars of the present.Footnote 5 However, existing discussions of counter-insurgency within International Relations (IR) show limited interest in what happened to imperial counter-insurgency projects after formal decolonisation. In other words, there is less critical attention to the ‘durability’Footnote 6 of counter-insurgency wars into ostensibly post-colonial states and how these projects were resituated on nationalist terrain. This occlusion is significant because although Western empires invented modern counter-insurgency as we know it, they hardly hold a monopoly on how these are fought, rationalised, or imagined. Indeed, some of the longest contemporary counter-insurgency campaigns have been waged by ostensibly post-colonial states, in turn shaping counter-insurgency doctrine and practice around the world.

Indian counter-insurgency campaigns are a key case in point.Footnote 7 India was a central theatre of British counter-insurgency across the empire.Footnote 8 India’s formal Independence from Britain in 1947 hardly signalled the end of such campaigns. Since ‘decolonisation’, India has been engaged in unending counter-insurgency wars across a range of geographies, within its territorial borders and in disputed territories like Kashmir, as well as abroad in Sri Lanka. While the campaign in Sri Lanka proved disastrous and Indian forces were forced to withdraw, many of its other campaigns remain ongoing, with no foreseeable end in sight. These have been waged by a dense array of state forces spanning the Indian Army and centrally administered paramilitary forces like the Assam Rifles and Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) as well as municipal and state police. Yet these campaigns remain largely overlooked in bourgeoning critical discussions of counter-insurgency in IR and beyond.Footnote 9

In this article, we respond to this lacuna through engagement with Indian counter-insurgency archives from 1947 onward, focusing on USI Journal. This publication emerged as a professional journal of the British Empire in 1871 and came under new management following Independence in 1947. It covers discussions of counter-insurgency campaigns stretching from the British Empire to Independence and into the present. USI Journal provides a window into how Indian state officials and others have debated and rationalised India’s counter-insurgency campaigns. Importantly, the trajectory of USI Journal post-1947 offers a literal and metaphorical bridge between the colonial and post-Independence histories of counter-insurgency in the Subcontinent. Thus, it complicates the nature of post-colonial Indian statecraft and its relations with “estern empire, past and present.

USI Journal is neither an academic nor necessarily a ‘high-quality’ publication (judged by the gold standard of double-blind peer review). Its impact on counter-insurgents outside of the Subcontinent is also uncertain. Yet methodologically it provides a window into the minds of the Indian counter-insurgents and their writings’ implications for the nascent Indian state. Rather than being a definitive guide to Indian counter-insurgency, it helps us grapple with how a handful of writers understood the specificities of Indian counter-insurgency within a wider global frame, including the boundaries between its multiple theatres as well as between ‘the colonial’ and ‘the post-colonial’. USI Journal does not capture the full range of perspectives shaping India’s post-Independence repertoire of counter-insurgency, an issue we return to below. Nevertheless, it offers a rich resource through which we can glean insights into not merely the conduct of counter-insurgency itself, but also how India enacts a post-colonial coloniality within its nation-building efforts.

We explore India’s ‘long wars’ – the counter-insurgency campaigns that the state imposed on recalcitrant populations, with a focus on those fought across its so-called north-eastern borderlands. India has waged expansive and unresolved wars, often in relation to nationalist struggles by particular groups, including religious minorities and Indigenous communities, to gain independence from the Indian federal state structure. These long wars, we argue, must be understood both as drawing inspiration from, but also departing in significant ways from, British colonial policy pre-Independence. The newly independent state largely internalised the logics of ‘Otherness’ through which north-eastern populations were classified by the British. Simultaneously, Indian counter-insurgents express desires to incorporate these regions and peoples into one unified Indian nation, ideologically and materially. In other words, whereas British counter-insurgency was premised on the logics of exclusion and racialisation that defined colonial rule, India’s counter-insurgency operations in north-eastern states post-1947 take place within territories that India claims as its own, gesturing to how borderlands are simultaneously within and without the grasp of the nation-state.Footnote 10 Nonetheless, Indian counter-insurgency thinking betrays some similar logics of differentiation to those of the British, and, as we show, the political economy of (post-)colonial rule results in its own particular sets of inclusions and exclusions. We tease out these tensions and the anxieties that underpin them by exploring how India’s long wars in its north-eastern states have been rationalised amongst Indian counter-insurgents, namely through their exceptionalist references to the ‘democratic’ and ‘diverse’ characters of the Indian state project. The registers of ‘diversity’ and ‘democracy’, we further argue, index India’s politics of disavowal of its violence, which represents an important weapon of war.

As we demonstrate below, this politics of disavowal seeks to legitimise efforts to pacify Indigenous populations and minoritised (non-citizens) and appropriate land and natural resources. Yet, in partial contrast to forms of imperial/colonial disavowalFootnote 11 that seek to distance empires from the places and subjects they intervene in, India’s disavowal of its violence manifests through somewhat distinct modalities with their own particular tensions and contradictions. Against this backdrop, the article makes two central contributions. First, by assaying India’s post-colonial status and its proximity (racial, geographic, etc.) to the populations it is fighting, we complicate dominant taxonomies of coloniality and statecraft that remain wedded to distinguishing types of colonialism on claims based on distance and difference, and to privileging a temporal reading of governance as ‘pre-colonial’, ‘colonial’ and ‘post-colonial’. We find these typologies and linear narratives wanting in the case of India. Second, by focusing on counter-insurgency waged by Global South state actors, we extend contemporary critical scholarship on long wars, which remains largely focused on Western counter-insurgency campaigns.

Situating ‘The Northeast’

‘The Northeast’ – officially referred to as the ‘Northeast Region’ (NER) – shares an international border of 5,182 kilometres (about 99 per cent of its total geographical boundary) with several neighbouring countries. This easternmost region of India represents both a geographic and political administrative division of the country. It comprises eight states – Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Tripura (commonly known as the ‘Seven Sisters’), and the ‘brother’ state Sikkim, which became part of India in 1975. ‘The Northeast’, an administrative category coined by the British, has persisted, representing an attempt to homogenise a heterogeneous border region with the aim of cathecting ‘Indian’ nationalism and nationhood upon disparate groups of people.Footnote 12 Over time, the shifting allegiances based on class, caste, religion, political affiliation, and expedience have led to relationships that do not map neatly onto the categories inherited by the Indian state from the British. This produced a patchwork of identities that escape the Indian state’s ongoing efforts to taxonomise the region and its peoples.

The first of these are ‘tribe’ and the ‘tribal’. The term ‘tribe’ in the context of north-eastern India does not have the derogatory undertones it does in many other places.Footnote 13 Indeed, the ‘tribes’ inhabiting the hills of north-eastern states have displayed a sense of place-based superiority, especially vis-à-vis (predominantly but not only) Muslim refugees who fled to north-eastern states from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 14 In these hills, refugees from Tibet and MongoliaFootnote 15 can lay greater claim to a fiercely contested borderland, where discourses of the ‘Otherness’ of ‘the Northeast’ propounded by Indian ‘mainlanders’ are rearticulated and weaponised against ‘Indians’ in general, and Muslims in particular. These contradictory forms of identification and alterity also abound in, and are further complicated by, discourses and notions of ‘Indigeneity’.

India does not officially recognise any of the autochthonous groups found within its borders as ‘Indigenous’. Although the politics of Indigeneity are beginning to take hold within the state, not least because of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People, India’s constitution has opted to divide the communities in north-eastern states along ‘tribal’ and ‘non-tribal’ groupings. Four hundred heterogeneous communities are grouped into one broad classification – of tribe – that distinguishes them from castes.Footnote 16 Likewise, all other people belonging to different communities and religions, and who speak different languages are deemed ‘non-tribal’. This latter group includes both recent immigrants to the region and those who have lived there for centuries. The politics of Indigeneity, therefore, often goes against the grain of the ‘protected category’ of ‘scheduled tribes’ deployed by the Indian state ostensibly for the purposes of economic development and cultural protection. ‘Protected’ groups themselves have further bifurcated along class. This is because those with access to land have become wealthy, whereas most others continue to live under oppressive conditions.Footnote 17 Relatedly, certain schemes introduced by the Indian state to preserve the ‘Indigenous culture’ of north-eastern tribes such as the Inner Line Permit have enabled certain groups classified as ‘Tribal communities’ to exert disproportionate power over other inhabitants.

Not only does the Indian state’s use of ‘tribal’ reinscribe colonial categories; it also creates an-Other enemy – that of the (largely) ‘migrant’ Muslim population – thereby providing grist to the mill of Indian nationalism. The Indian state has long mobilised these categories towards its own ends, for instance, bolstering claims to Indigeneity when it undermines working-class solidarity across religious and communal divides.Footnote 18 Through its recurring reliance on the ‘tribal’ frame, the Indian state has further evacuated Indigeneity of any radical potential as a ‘dynamic and interconnected concept of Indigenous identity constituted in history, ceremony, language and land’.Footnote 19 As Sanjib Baruah notes in relation to land rights in north-eastern India, ‘it is often hard to graft the easy binaries of indigenous/settler, insider/outsider, or tribal/nontribal on the “tangled thicket of tenure relations”’.Footnote 20 In this article, we do not weigh in on the involuted logics of claims to Indigeneity by the communities themselves. Instead, we focus on the long wars waged by the Indian state in these regions, which at times exhibit the logics of settler colonialism.Footnote 21

Counter-insurgency in IR

IR scholarship on counter-insurgency has long been at the centre of efforts to rethink core concepts and orthodoxies in the field. Scholars have focused on the workings of foreign policy,Footnote 22 the status of national borders and their differentiation of inside/outside,Footnote 23 on violent cartographies and genocide,Footnote 24 ‘globalisation’Footnote 25 and the political/ideological underpinnings of security studies.Footnote 26 Recent discussions of counter-insurgency have been effectively mobilised to challenge the tenets of conventional international – and social theoryFootnote 27 and within it central concepts therein, not least of all warFootnote 28 and its imbrication with and distinction from police.Footnote 29

These discussions within IR and across cognate disciplinesFootnote 30 have principally focused on colonial and imperial counter-insurgency campaigns waged by major Western powers against their subjugated populations ‘at home’ and abroad.Footnote 31 This shows that the origins of counter-insurgency in global politics are quintessentially imperial and inextricably imbricated with material dispossession and race-making.Footnote 32 The history of the British empire has long been central to these discussions, with the histories of imperial and colonial India playing a particularly significant role.Footnote 33

However, scholars have been less attentive to the fates of imperial and colonial counter-insurgency projects after formal decolonisation, despite notable exceptions.Footnote 34 Indeed, some of the longest-running counter-insurgency campaigns waged by more powerful states in the Global South like India – but also Brazil and Indonesia – remain relatively uninterrogated. Perhaps even more importantly, Western counter-insurgency casts a long shadow, keeping other counter-insurgency projects peripheral. The ‘counter-insurgent imagination’Footnote 35 remains theorised as quintessentially Western, even though counter-insurgency’s actually existing geographical remit has always been and remains global.

The lack of critical concern for the centrality of counter-insurgency to nationalist projects within post-colonial polities is significant for three key reasons. First is the question of scale and duration. In terms of contemporary counter-insurgency projects, US-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have been enormously destructive and costly. Before the campaign in Afghanistan officially ended in 2021, it had been the longest formally declared war in US history. Yet some of the longest running contemporary counter-insurgencies are in places like India. India’s long wars have been waged continuously for over seven decades and have no foreseeable end in sight.Footnote 36 They have also consumed enormous resources and lives as well as being deeply entwined with the theft of land and natural resources from Indigenous communities. To date, however, their costs and political economies remain comparatively neglected by critical scholars.Footnote 37 Second, a focus on the West continues to reinscribe a Eurocentrism, albeit in the form of critique.Footnote 38 We often look to counter-insurgency operations led by Europe and the US as exemplary and thereby continue to privilege the West as a site of knowledge production par excellence. Finally, the focus on Euro-American imperial powers elides how colonialism endures within ostensibly post-colonial state structures and practices. This last point is most germane to our analysis below.

This is by no means to suggest that the conduct of counter-insurgency campaigns in Global South contexts is completely ignored. Mainstream IR and strategic studies have extensively examined the campaigns of post-colonial states, including India’s. However, these discussions exhibit far more problematic features than those we have identified in critical scholarship (above). They include tendencies to exceptionalise post-colonial counter-insurgency campaigns as softer, less violent, and more ‘humane’ alternatives to Western onesFootnote 39 and to juxtapose national counter-insurgency as an alternative to the study of imperial/colonial forms.Footnote 40

For us, neither approach is satisfactory. While grappling with the durability of imperial/colonial counter-insurgency campaigns in post-colonial polities, we seek to open space to interrogate these projects’ specificities and disjunctures from Western counter-insurgency campaigns and their forms of reasoning and legitimation. This focus on the resonances and dissonances between colonial and post-colonial – including the simultaneous disavowal of state violence and interpellation of populations in territories being pacified – helps situate India as an actor with colonial intent and apprehend these projects as distinctly coloured by colonialism, even in putatively post-colonial spaces like India’s north-eastern ‘hinterlands’. As we demonstrate, counter-insurgency projects in post-1947 India have always been and remain underpinned by flagrantly racial precepts, which work to racialise various Others. Yet post-1947 those leading the charge against such insurgent Others have been officials of the Indian state for their own ideological and material ends, rather than those of Western states seeking to outsource their counter-insurgency operations to client states. Thus, we argue, it is necessary to engage more closely with their armature, including enduring practices of knowledge production.

A note on method and sources

Like all counter-insurgency campaigns, India’s have been waged across multiple registers and geographies simultaneously, including but not limited to literal battlefields. Our concern here is on how these long wars have been rationalised within spaces of professional strategic debate alongside wider public spheres, both within India and transnationally. We seek to wade into the texture of the Indian state’s ‘prose of counterinsurgency’Footnote 41 post-1947 and how it relates to those of other times and places.

Indian professional journals published by think tanks and policy institutes, of which USI Journal is but one part, represent important fora for such rationalisation.Footnote 42 Though filled with entries written by current and former Indian military and police officials (and occasionally foreign authors), the content of USI Journal and related Indian publications does not formally represent Indian state policy or doctrine.Footnote 43 They do, however, represent attempts to bring together common ‘experiences’ of and draw ‘lessons learned’ from India’s various military- and police/military-led campaigns to systematise and improve policy and strategy. While the broader project out of which this article emerges engages with a much more diverse range of such publications, we deliberately focus on USI Journal here for a few key reasons. First, unlike its competitors that emerged later,Footnote 44 USI Journal is the only Indian professional strategic affairs journal to cover the entire period from 1947 to the present, thereby bringing into focus the (supposed) break between colonial and post-colonial. Second, given its status as India’s oldest strategic affairs publication, it was an important first mover in the attempts to assemble a body of specifically Indian thinking on such matters as part of a broader nationalist project. The emergence of other competing Indian journals lags behind USI Journal’s handover to Indian officials by at least two decades. Third, not only has leading contemporary Indian counter-insurgents’ writing developed in partnership with the United Services Institution, but this work also cites USI Journal materials as the basis of its claims.Footnote 45 More broadly, influential scholars on Indian counter-insurgency take USI Journal writers’ views as indicative of distinctively Indian perspectives and approaches to counter-insurgency, including its (alleged) uniqueness.Footnote 46

We draw on a selection of articles between 1947 to the mid-1980s, during which some of the most intense Indian counter-insurgency campaigns were waged. Methodologically, we approach these sources as illuminating how Indian state violence is rationalised as ‘normal’, reasonable, democratic, just, etc. and how these are put to work within the Indian nationalist project. USI Journal’s authors are also exclusively male, relatively privileged, and educated upper-caste writers, often those that were the natural successors to colonial rule, thereby reflecting the gendered nature of counter-insurgency projects.Footnote 47 USI Journal also over-represents particular backgrounds and communities in India such as Punjabis and Gurkhas, reflecting the endurance of colonial notions of ‘martial races’.

While our focus is on discussions of counter-insurgency campaigns within India’s internationally recognised territorial borders, the conduct of such campaigns and the repertoires that nurtured them cannot be understood within an exclusively national frame. Below, we show how the rationalisation of India’s long wars intersects with and is co-constituted through their connection to other bodies of counter-insurgency knowledge and practice. This is because although the content of USI Journal is primarily written for and by Indian nationals, it drew its inspirations from theatres beyond India.Footnote 48 Moreover, the publication maintained its transnational circulation well after 1947.Footnote 49 As such, we approach USI Journal as an archive of the prose of Indian counter-insurgency that is quintessentially nationalist and always-already transnational.

‘Democracy’ and ‘diversity’

Foundational myths of the ‘nation’ shape how states are conceived, built, and sometimes manifested. ‘The state’, as Eric Cheyfitz reminds us, ‘requires the narrative of the nation to cover its tracks.’Footnote 50 Such myths are relational and transnational, seeking to forge identities, positions and ideas of national essences vis-à-vis other locations, civilisations, and nationalist projects.Footnote 51 For newly independent and nominally decolonised states, these myths play particularly significant roles in attempts to differentiate themselves from others. According to Perry Anderson, out of India’s struggle for independence emerged four central tropes – ‘antiquity–continuity’, ‘diversity–unity’, ‘massivity–democracy’, and ‘multi-confessionality–secularity’ – which have played formative roles in consecrating the broader ‘idea of India’.Footnote 52 More recently, Taylor C. Sherman identifies seven animating myths that structured Nehruvian India in the immediate post-1947 period, namely those of Independent India, non-alignment, secularism, socialism, democracy, the strong state, and high modernism.Footnote 53

We focus on these myths’ roles in negotiating and (re)defining India’s position in the world-system. Thus, we are concerned not merely with such myths as stand-alone entities or ideologies but rather how they operate within global politics. To this end we mobilise an analytic focus on India’s exceptionalist self-narration. While the most influential accounts on exceptionalist narration have emerged in the study of Western empire,Footnote 54 an emergent body of literature has begun to grapple with their roles in anti-colonial struggles, post-colonial politics and foreign policy.Footnote 55 Kate Sullivan de Estrada has shown that Indian exceptionalist ideas, particularly those concerned with India’s ‘moral pre-eminence’ and unique capacity to offer moral leadership in global politics, played central roles in the formation of Indian foreign policy as early as the 1940s and through to the 1960s,Footnote 56 later developing into India’s claim to be a vishwaguru (teacher of the world).Footnote 57 A focus on exceptionalist self-narratives offers an analytic conception of the global and the local not as two separate things to be reconciled but ‘as already existing in a specific place and time, and in constant coconstitution’.Footnote 58

In what follows, we position the recurring references to democracy and diversity in USI Journal as forms of exceptionalist narration. We show how such narrations seek to rationalise the violence of the Indian state against its various enemies. In doing so they also grapple with the emergent Indian state’s relation to Western imperial and colonial counter-insurgency projects in the Subcontinent and beyond.

Democracy

The pages of USI Journal focus on lionising the Indian state’s ‘success in a system of parliamentary democracy’Footnote 59 and venerating the Indian soldier as a ‘cornerstone’ thereof.Footnote 60 This is hardly surprising given India’s long-standing claim to be the world’s ‘biggest democracy’. While this claim has been challenged by ‘enemies of the state’,Footnote 61 it continues to be celebrated at home and in the West even amid concern over the rise of Hindutva under Modi.Footnote 62

However, USI Journal’s references to India’s democratic character as integral to national security prerogatives do key work in justifying the perpetuation of violence against various Others, including Indigenous communities in north-eastern states. For instance, discussions on ‘unconventional warfare’ in the mid-1960s reflect on the roles of centrally administered ‘special forces’ in helping to train and equip ‘indigenous’ i.e. local forces to carry out guerilla war and counter-insurgency operations effectively.Footnote 63 Authors recommend respecting local populations living in counter-insurgency theatres and attempting to understand their local customs and traditions as well as economic conditions and political aspirations in ways that could potentially enable the special forces to ‘merge with the local population in appearance, customs, habits, language and way of living’.Footnote 64 The counter-insurgent imagination here is thus one of Indian army forces undertaking a kind of mimesis of their insurgent adversaries through adopting what another author terms as their ‘tribal tactics’Footnote 65 and gaining competency with local ways of being, yet in such a way that is mutually respectful and consensual rather than extractive and violent.

Although couched in terms that pay heed to India’s democratic ethos, these articles concede the existence of a fundamental divide between central state forces and local Indigenous populations. It is evocative of colonial and neo-imperial counter-insurgency campaigns, including in Malaya under the British and Afghanistan under the US, where the impulse to win ‘hearts and minds’ stems from a recognition that those waging counter-insurgency campaigns are outsiders and occupiers.Footnote 66 It is also reminiscent of the ruthless grammars of counter-insurgency that the British deployed in India at the height of Empire.Footnote 67 Given that this long war is waged within independent India’s officially recognised national borders, however, the juxtaposition of the soldier against a tribal outsider/Other is telling and intimates complex relationships between types of Indian ‘citizens’.

Other articles from the 1960s echo this imperative of maintaining India’s national (democratic) essence, while fighting insurgents.Footnote 68 They stress that fighting counter-insurgency campaigns within national borders is necessarily based on a commitment to restraint or democratic credentials and that excesses are the exception rather than the rule. Such accounts represent the Indian soldier as a professional and moral figure generally unaccustomed to meting out gratuitous violence,Footnote 69 thereby implying that examples thereof are exceptional rather than routine or inherent in (Indian) counter-insurgency campaigns. This is not unique to Indian counter-insurgency. The British likewise defended their record in India and elsewhere as not particularly violent, even as they enacted an explicit policy of ‘savage war’ in their imperial strongholds.Footnote 70

In the Indian national context, questions about territorial integrity and geopolitical borders became central to the (ostensible) imperative of ensuring that Indian counter-insurgency operations uphold democratic credentials. In the 1960s, the Indian state was especially fixated on the ‘Chinese problem’ and the threat of Chinese military activity on India’s north-eastern frontier. Indian counter-insurgents also drew considerable inspiration from Chinese strategy, even as the authors in USI Journal found China wanting on the democratic front, suggesting that certain Chinese tactics were unsuitable to India because of the latter’s democratic character.Footnote 71 Indeed, in keeping with their ostensible imperative of maintaining India’s vibrant democratic character, USI Journal authors suggest fighting counter-insurgency operations is not wholly or even primarily a tactical matter but rather one of cultivating ‘people’s support’,Footnote 72 in other words ‘winning hearts and minds’ and the implied consent of local populations being pacified. Across the journal, democracy is frequently touted as exerting a determining influence on Indian counter-insurgency ex post facto.

When ‘democracy’ cannot be made to fit the justification for certain actions, Indian counter-insurgents represent populations being pacified as outside their democratic ambit. A 1969 article on Nagaland, while emphasising territorial borders as a central problem of insurgency in India’s newest (sixteenth) state at the time, displays this thinking in action. Casting Nagaland as a ‘problem state’ suffering from a lack of security and underdevelopment,Footnote 73 the author contends that its problems stem directly from its status as a ‘border state’ prone to instability. Indeed, the author frames the imperative of integrating Nagaland into (mainland) India and thereby rendering it as a ‘contented border state’ as the best policy option available, representing this as a shift away from the British policy of the region’s historic ‘isolation’.Footnote 74 Yet tellingly the article casts Nagas as quintessential outsiders to the Indian nation-state and trivialises their claims to Indigeneity. It frames questions of their origin as indeterminate –‘anybody’s guess’ – though nevertheless classifies them in racial terms as being ‘Indo-Mongoloid’, based on their ‘physiognomy’.Footnote 75 This terminology is borrowed directly from the British, who coined the term ‘Mongolian fringe’ to describe the border populations of the north-eastern edge of British India. In this instance, the author contends that while folding the Nagas into Indian democracy is essential to pacifying them, they make no reference to Nagas as fellow Indian brethren in high-minded Nehruvian terms. The Nagas are instead cast as threats and racialised outsiders. Democracy does not apply to them until they can be democratised into submission.

The way that USI Journal defines the core terms of insurgency and counter-insurgency is also a crucial barometer of India’s democratic credentials. In its pages, counter-insurgency is often apprehended as necessary for developing countries to govern effectively and sometimes represented in contradistinction to imperial and colonial conquest. A 1970 article notes that ‘With wars of colonial conquests out-dated and against the background of nuclear balance of terror, insurgency has now become an accepted form of warfare’.Footnote 76 The author further suggests that insurgencies are, at their core, problems of (under)development (rather than matters of colonialism or extraction) and that developing nations like India suffer from poor and ‘vulnerable’ societies, serving as ‘breeding grounds for insurgency’.Footnote 77 The author defines insurgency as a struggle with the support of the bulk of the population, though he argues that whereas nationalism fuelled insurgencies historically, at the time of writing communism had become their underlying ‘motive power’, often relying on external support.Footnote 78

This is a common trope seen across the journal, namely that even though some insurgencies like those of the Nagas and Mizos make claims about the need for a separate nation-state and that such claims enjoy popular appeal, insurgencies necessarily require foreign assistance and/or inspiration. As Joseph McQuade argues, this has precedents in British counter-insurgency in India.Footnote 79 McQuade’s intervention is specifically into the confected colonial discourse of ‘terrorism’ and the justification it provided for British imperial violence in large swathes of India and along its borders. Yet this prose has proven durable and useful to Indian counter-insurgents post-Independence.

Accompanying this general trope of separatism/terrorism is a common anti-communist refrain that presents the defence of Indian democracy as the primary consideration in strategic planning, sometimes mobilising the spectre of ‘communist military and ideological infiltration’ to justify moving away from a purely defensive posture.Footnote 80 Other authors mobilise this trope of outside interference to legitimise India’s defence of ‘democracy’ as an ‘integral value’ within its borders against such external threats.Footnote 81 By construing the Nagas as an ‘outside’ threat to India’s democracy, the state seeks to legitimate the violence of counter-insurgency in the name of democracy.

In the immediate decades after 1947, questions of integrating border states/regions/peoples into the national body politic became a central national prerogative. Yet by the 1980s, alongside the multiplication and intensification of insurgencies across multiple Indian states as well as Jammu and Kashmir, India’s national integrity was coming into view as an open question. Under these conditions, USI Journal increasingly presented ‘democracy’ not merely as a justification but also as a fix. A 1984 article notes that, although India has been vulnerable to ‘insurgency and fissiparous tendencies’ in places like Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Andhra Pradesh, North Bengal, Kashmir, and Punjab, it remains ‘a developing country with a difference’ in large part because of its unshakable democratic roots.Footnote 82 Thus, claims to India’s democratic character provide cover for the perpetuation of India’s long wars.

Another 1981 article by Colonel V. K. Anand extends these claims about the supposedly ‘democratic’ features of Indian counter-insurgency and distils key ‘governing principles’ thereof. It makes the case that in ‘free societies’ it is imperative that ‘democratic norms have to be advocated and followed against the insurgent’.Footnote 83 Echoing the imperative of ‘wining hearts and minds’, Anand recommends that counter-insurgents exercise restraint and adopt a posture of ‘gratuitous benevolence’ as the ‘main plank’ of engagement with masses and insurgents in unstable areas.Footnote 84 This framing suggests that a policy of ‘minimum violence’ is the only way to turn the tide against insurgents, again drawing contradistinctions to Chinese counter-insurgency practices in Taiwan as quintessentially undemocratic. He argues that ‘Extortion, blackmail, falsehood and rampant corruption and maladministration as perpetuated by the KMT [Kuomintang] cannot become instruments of a democratic system’.Footnote 85 This analogy has colonial precedent. As Kate Imy notes, the tactic of drawing racial (and gendered) distinctions between populations was key to the waging of counter-insurgency by Western empires.Footnote 86 This meant differentiating populations within territories and distinguishing British colonial counter-insurgency from other types of violence, which (allegedly) belonged to other peoples and places.

The comparisons in such analyses are in no way accidental. They do crucial political work,Footnote 87 both in making the case that Indian counter-insurgency is indeed democratic and in construing Indian forces as ‘indigenous’ to all parts of India. Comparison is mobilised to set (Indian) ‘indigenous’ counter-insurgency apart from its imperial/colonial counterparts. Anand notes that because ‘Complete indigenisation’ is the basis of insurgents’ tactical superiority, ‘alien’ counter-insurgents suffer from inherent ‘handicaps’. For him, this is evinced in how Americans ‘belonged to an altogether different race, colour, religion, culture and linguistic area’ than their adversaries in Vietnam. On this basis he argues that the ‘indigenisation of the counter-insurgent’ offers the prospect of operating on an equal footing to the insurgents.Footnote 88 Such reasoning thereby posits that fighting within one’s territorial borders with ‘indigenous’ forces who share a similar (racial) identity bodes well for India’s counter-insurgency campaigns. This duality of Indian counter-insurgency lends itself a uniqueness, further muddying the waters between what is considered ‘colonial’ and what is not. Indian soldiers are represented as fighting their own people towards the shared ideal of democratisation, yet simultaneously involved in a war of attrition against enemy others, racialised as not-quite-yet Indian. The blurring of lines between insider and outsider, between citizen and ‘foreign agent’, between brethren and foe is more than a red herring; it lies at the heart of Indian counter-insurgency practice and statecraft and Indian (post-)colonial identity more broadly. Anand credits the creation of Nagaland both to the ‘super human restraint’ exercised by counter-insurgents fighting in the region and as a response to mass (democratic) demands, thereby helping India to ‘satisfy the overwhelming majority’.Footnote 89

The subsumption of counter-insurgency under the arc of democracy obfuscates the colonial coordinates of these operations: their intrinsic violence, destruction, dispossession, and constituent practices of policing, surveillance, and bombardment.Footnote 90 The invocation of ‘diversity’ further sediments the disavowal of these logics.

Diversity

As noted above, diversity is a core element of India’s national mythology that is entwined with others. For instance, the Indian tricolour national flag has diversity claims hardwired into it, sidelining disputes about which communities, ethnicities, and religions to include and which to exclude. What concerns us most, however, is how references to ‘diversity’ are mobilised within the prose of Indian counter-insurgency in the post-Independence period and what this does to our understandings of India as a (post-)colonial state. Our discussion of ‘tribes’, ‘tribals’, and various Others already touched on questions of diversity, more specifically with respect to how the emergent Indian state and its chosen terminology of ‘counter-insurgency’ represented these Others as simultaneously ‘domestic’ and ‘internal’ to the state and therefore under its sovereign jurisdiction but also foreign, less than truly Indigenous, or proxies of communist infiltration. This points to the fraught and contradictory ways that ‘diversity–unity’ is at work the nationalist project of Indian counter-insurgency.

From 1947 onward, explicit references to diversity-unity are present within USI Journal. The 1950 volume has an image with a crest picturing an eagle with the heading underneath BHINNEKA TUNGGAL IKA ‘UNITY IN DIVERSITY’ (Figure 2).Footnote 91 But by the 1980s amid the multiplication and intensification of insurgencies across India, counter-insurgents began to ruminate on the roles of minorities vis-à-vis the state’s solidity. While this concern was a focus across much of the Global South at the time, USI Journal authors argued that although problems of ‘national integrity’ are common to most developing countries, India’s exceptional degrees of diversity made it especially prone to fragmentation. Treating ‘diversity’ as a stand-in for the different cultures, ethnicities, backgrounds, and languages characteristic of India before the arrival of Europeans, a 1984 article locates ‘diversity’ both as a source of ‘strength’ and as a threat to the coherence of the Indian national project because of its ‘fissiparous tendencies’.Footnote 92

Figure 2. ‘Unity in diversity’, USI Journal, July–October 1950.

While presenting diversity as a positive and distinguishing feature of the post-Independence Indian state, the article makes the case that nationalism (supposedly long-standing in India) represents the glue that holds India together in the face of threats caused by its inherent diversity ‘from Kashmir to the Kanyakumari and from Punjab to the Eastern States’.Footnote 93 The widespread disillusionment with the Indian state in places like Kashmir, Punjab, and the ‘Eastern States’ prompts the author to admit that nationalism ‘does not mean peace and harmony within a nation’.Footnote 94 This implies that diversity necessarily engenders some level of conflict and/or violence in a nation-state. Crucially, echoing a common thread throughout the archive, the author argues that current threats to ‘national unity’ arise from the machinations of sub-national politicians who sacrifice ‘national integrity for political gains’, citing Phizo (a Naga nationalist), Laldenga (a Mizo separatist), and Jagit Singh Chauhan (a leader of the Khalistan Sikh independence movement in Punjab) as examples.Footnote 95 In other words, it is the agitators who are the cause of the insurgency and violence rather than the violent and extractive practices of the Indian state. Thus, diversity represents a double-edged sword to be managed by giving certain peoples and communities access to Indian democracy while excluding others.

A 1987 article by Lieutenant Colonel Y. S. Panwar returns to the unity–diversity interface, recalling the above-referenced ‘unity in diversity’ slogan and emblem used in 1950. It begins by noting the political context that motivated the writing, namely the threats being posed by the ‘fissiparous forces [that] are getting increasingly menacing by the day’.Footnote 96 Panwar suggests that although India was never formally a nation prior to Independence, ‘in the midst of the disunity there survived a geographical entity called Bharatvarsha’.Footnote 97 Such claims echo key Hindutva tropes, which have gained ascendancy and ever-deepening mass appeal across India and its diaspora today.

Panwar further suggests that although India’s much venerated Constitution enshrined the concept of a free, independent India, at the time of writing the same document has become a source of destabilisation.Footnote 98 He emphasises that in the midst of questions about the integrity of post-colonial India ‘the very fact that the cry today from many a States is for “Diversity in Unity” and not “Unity in Diversity” as cherished by the central leaders, portends a situation wherein we may not find it possible to survive within the framework we had laid down for ourselves’, namely a federal structure governed by parliamentary democracy.Footnote 99

What is particularly telling here is the critique of ‘Diversity in Unity’ rather than ‘Unity in Diversity’ (the latter which circulated in the immediate post-1947 period). ‘Diversity’ is framed as no longer serving its original function and cast in racialised terms. Panwar cites Laldenga as saying that ‘different racial origins’ and tribal identities/practices are the reason as to why he needed a ‘safeguard from the Indian government’, despite accepting its Constitution: ‘This is what the negotiations are all about … And whether in Tripura, Mizoram, Nagaland or Manipur the fundamental reason deep down in the heart of man is race.’Footnote 100

It is striking to see these overarching questions of coloniality and (internal) colonialism in post-1947 India being confronted so head-on in USI Journal. Panwar contends that: ‘The underlying causes for insurgency in the North East are the tribals’ difficulty of identifying with the [Indian] mainland, their fierce sense of pride and honour and their resentment at being meted out a colonial treatment.’Footnote 101 Again, he cites Laldenga: ‘The white master left us and the brown master stepped in.’Footnote 102 Thus, through discussions of diversity in the prose of Indian counter-insurgency, questions about the (supposed) liberal, Gandhian associations of the term are smuggled into the discussion, sometimes in unexpected ways. Counter-insurgency in India contributes to a racialisation of diversity, keeping alive the ambiguity of the relationships between the state and its wayward insurgent populations. This facet of Indian counter-insurgency, although crucial to India’s troubled status as a post-colonial imperial state, remains relatively unexplored.

We read the recurring references to ‘democracy’ and ‘diversity’ in USI Journal as attempts to differentiate colonial/imperial, communist/authoritarian counter-insurgency approaches from ostensibly more humane, post-colonial forms. While such efforts are primarily framed in terms of overcoming the challenge of these long wars as a national problem for the Indian state, they also have a core pedagogic orientation that seeks to position India on the world stage as having unique (or even superior) perspectives on counter-insurgency to be shared with others in keeping with India’s vishwaguru imperative. As Sullivan de Estrada argues, vishwaguru represents ‘a shorthand for a wider category of nationalist and civilizational beliefs’ spanning from 19th-century colonial India to the present ‘that have operated with … [a] “sense of mission” in the world’, namely the desire to ‘remake the global social hierarchy of civilizations and states’ by inverting them.Footnote 103 Yet even though exceptionalist self-narratives can and do work as responses to hegemony that actively seek an inversion of colonial and imperial hierarchies, they can also work in the service of domination.Footnote 104

This observation is particularly significant and one that we aim to extend. This is because although exceptionalist narrations of Indian counter-insurgency are not equivalent to those at work in Western imperial/colonial reasoning and practice, they do share at least one thing in common. This is their central work in mobilising nationalist and civilisational myths to disavow the inherent violence of counter-insurgency. Indeed, the ‘exceptionalist mode’ of narration ‘functions to deny the violent displacement of Indigenous peoples’ under Western settler colonialismFootnote 105 but also within the prose of Indian counter-insurgency, as we explore next.

The politics of disavowal

Above we explored how the violence of the Indian nationalist project has been historically rationalised within the prose of Indian counter-insurgency post-1947 by focusing on references to India’s ‘democratic’ and ‘diverse’ character. In this final section, we address the overarching processes of disavowal at work in this exceptionalist prose. We argue that the enduring instantiation of the ‘idea of India’ in its hegemonic forms is predicated on a disavowal of the ‘violent heart’ of Indian politicsFootnote 106 of which counter-insurgent warfare is a crucial part. We delve deeper into this politics of disavowal, arguing that it evinces an aspect of an underlying coloniality at work in Indian statecraft. We thereby extend critical discussions about India’s north-eastern regions within Indian nation-building.

Baruah shows how the region derogatorily and artificially lumped together as ‘the Northeast’ follows a political trajectory distinct from the rest of the country.Footnote 107 Focusing on what he calls the ‘AFSPA regime’, he shows how the Northeast has become established as an ‘anomalous zone’ reminiscent of Agamben’s arguments about states or zones of ‘exception’Footnote 108 established by states in frontier spaces where their sovereignty is contested. According to Baruah, special security laws, like the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), produce substantial ‘democracy deficits’ that shape the dynamics of a frontier along multiple axes – racialisation, resource extraction, and violence with impunity.Footnote 109 We build on this argument, while contending that the creation of an ‘affective boundary’ between what Baruah calls ‘India proper’ and its north-eastern hinterlands, is not merely the politics of a state trying to impose control over its unruly border zones. It is also a poignant example of how counter-insurgency in post-1947 India remains structured by antecedents in the ‘external’ colonisation of the British Empire as well the settler colonisation of the Americas and Australia.Footnote 110 India’s colonial governance in north-eastern states, we submit, has been sustained through a careful disavowal of its long war on Indigenous peoples and lifeways in this region.

(Post-)colonial reasoning

The annals of USI Journal are saturated with colonial and racial tropes and forms of reasoning, which cast Indigenous insurgents like the Nagas as being of the ‘Indo-Mongoloid’ race and represent their lifeways as pre-modern, savage, and ‘tribal’. Articles further assert that these so-called tribals’ desires to fight against the Indian state post-1947 reflect a deep-seated and long-running cultural attachment to violence pre-dating Independence. One author offers readers the opportunity to ‘go back by about 85 years and peep stealthily through the impregnable bamboo curtain into the hill-top villages of the Naga Hills separated by the deep valleys and spiritually by the god of vengeance and vendetta’.Footnote 111

This, we argue, manifests a coloniality – sometimes subterranean, at others overt – that saturates all Indian counter-insurgency thinking from the outset of the post-1947 period onwards, which can be traced back directly to British colonial rule.Footnote 112 As the above references to Laldenga allude to, moreover, many insurgents themselves clearly grasped the coloniality of Indian statecraft early on as they fought Indian state forces in north-eastern states. As we explore below, USI Journal also evidences other elements of the coloniality of Indian counter-insurgency projects.

Colonial inspirations

In a way that might first seem contradictory to India’s status as a post-colonial state and leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, USI Journal authors frequently draw ‘lessons’ from other imperial and colonial counter-insurgency operations and seek to apply their insights within Indian counter-insurgency theatres. There are frequent and favourable references to British counter-insurgency in Malaya.Footnote 113 A 1968 article offers readers ‘practical hints on the conduct of operations which may be of use to the officers commanding company columns in the Mizo Hills’.Footnote 114 Among other lessons from past counter-insurgency projects beyond India, it argues that thankfully ‘There is much that can be done to achieve success as was demonstrated by the British in Malaya’.Footnote 115

These counter-insurgents also draw explicit and favourable parallels to Indigenous dispossession and extermination in North America and Australia as instructive case studies that might inform how Indigenous populations can be successfully pacified as part of wider strategies of improvement through ‘development’, peddling another Indian foundational myth.Footnote 116 One 1966 article positively references the ‘long history’ of unconventional war including in ‘the American War of Independence, war on western border against the Apaches and the Red Indians’ as points of reference.Footnote 117 But such comparisons are especially prominent in one 1967 article by Lieutenant Colonel Paul Varma. Praising the triumph of ‘modern progressive nations’ over ‘backward tribes’, he argues that India has a lot to learn from Western settler colonies. North America and Australia, he argues, ‘illustrate how the richest combination of mineral resources and natural wealth avail nothing in the absence of human ability to utilize them’.Footnote 118 As he elaborates:

The original inhabitants of North America, the so-called Red Indians, were all but annihilated by the settlers from Europe despite vastly inferior numbers of the latter; this was principally possible on account of the superior knowledge of the settlers … Subsequently, the determination and pioneering enterprise of these settlers were rewarded a thousandfold as the virgin soil and untouched mineral resources of the continent yielded up their riches. All of this potential wealth, the present day foundation of the economic, political and military power of the United States, lay dormant and unexploited under the bison economy of the North American Indian tribes. The Australian story is similar.Footnote 119

Varma thus waxes lyrical about settler genocide as exemplary of efficient primitive accumulation in practice. Varma explicitly and enthusiastically cites this settler colonial genocide as an inspiration for India, recommending that ‘we [Indians] should look more to the character of the nations and their ability to control and improve upon their environments as being more truly indicative of their strength and potential’.Footnote 120 He makes the case that the genocide of Indigenous peoples is the basis of accumulation through the ‘improvement’ of land and a natural pathway to modernity for the Indian nation-state. As we explore next, however, these attempts by Indian counter-insurgents to draw parallels to colonial pacification campaigns of Western empires as inspirations for Indian statecraft are not merely a form of ‘mimicry’;Footnote 121 they also serve as points of differentiation. Indian counter-insurgency departs in significant ways from its Western counterparts, which in turn raises pertinent questions about how we might engage borders and the foreignness/domesticity of counter-insurgency in India and elsewhere.

Borders and their outsiders

USI Journal authors consistently represent nationalist movements in Nagaland, Mizoram, and other ‘unruly’ north-eastern areas as ‘internal’ problems and ‘insurgencies’. Such discussions begin in the early post-1947 period through the terminology of ‘guerrilla war’.Footnote 122 By the late 1960s, the terminology has shifted to one of ‘insurgency’ and ‘counter-insurgency’, reflecting the growing global hegemony of this language in relation to the US wars in South-east Asia. Nevertheless, references to the importance of ‘guerrilla war’ and ‘guerrilla tactics’ endure in the prose of Indian counter-insurgency. For instance, the slogan of the Indian Army’s Counter Insurgency and Jungle Warfare School (CIJWS), founded in the state of Mizoram in 1967, is to ‘fight the guerrilla like a guerrilla’.Footnote 123

Since the late 1960s, however, Indian state officials have generally shown a preference for the language of ‘counter-insurgency’ as its predominant framework for its campaigns in north-eastern states and elsewhere for self-serving political reasons. As Baruah notes, in the context of north-eastern states, the term insurgency was preferable to war and ‘armed conflict’ precisely because India wanted to inscribe the ‘sanctity of the principle of state sovereignty and the complementary principle of noninterference’ in its ‘domestic’ affairs.Footnote 124 Indeed, USI Journal articles frequently represent north-eastern states as ‘disturbed’ and therefore requiring central state forces to ‘help in the restoration of normalcy’.Footnote 125 Counter-insurgency in spite (or because) of its colonial connotations was normalised by the Indian state.

On one hand, the rhetorical preference for an insurgency/counter-insurgency vocabulary stands in contrast to and tension with its rejection by British officials in their imperial endeavours in Northern Ireland, in part because the lexicon of counter-insurgency acknowledges the political legitimacy and mass character of insurgencies.Footnote 126 Relatedly, Indian counter-insurgents often define their counter-insurgency projects in contradistinction to those of Western states and empires (as well as communist states), in part by asserting their ‘democratic’, and by extension just, character.

On the other hand, despite the vocabulary of counter-insurgency to assert the domesticity of these battles and thereby exercise national sovereign jurisdiction over them, the Nagas and Mizos are also frequently labelled as Others, outsiders, and lumped together with other ‘international problems’ that ‘surround India’, including Indo-Pakistan disputes, separatist movements, and the Vietnam and Malaysian wars.Footnote 127 Indeed, USI Journal represents insurgencies against the Indian state as being sponsored and inspired by actors outside of India.Footnote 128 Despite these efforts to disavow the inherent violence of its campaigns against separatist movements in north-eastern states, a close reading of the prose of Indian counter-insurgency attests to the internal colonisation of these areas by what is experienced by Indigenous communities as the presence of a foreign ‘occupying power’.Footnote 129 Far from being ‘unnatural’ or out-of-place, the separatist tendencies can be read as demands for decolonisation.

As in more familiar settler colonial contexts, USI Journal evidences Indian counter-insurgents’ attempts to simultaneously cast out and forcibly fold in different communities as a form of assimilation or ‘integration’ into the Indian state-building project.Footnote 130 Alongside his extolling of the virtues of American settler ‘ingenuity’ in removing ‘backward’ tribes from the land to make way for extractivism referenced above, Varma locates some north-eastern communities within the Indian nation-state. Crucially, although framed within the prerogative of national security, the prevailing imaginaries expressed within USI Journal in the late 1960s onwards present these problems as intra-national matters. And yet, remaining consistent with the tensions inherent to Indian counter-insurgency, Varma relegates those agitating for greater political representation and/or independence as foreign to India, equating them with ‘complex international problems [that] surround India’. In his account, such ‘problems’:

include the apartheid question, various African independence and post-independence movements, various West Asian rivalries, a number of Indo-Pakistan disputes, the Malaysian wars, the Viet-Nam war, Indonesia, the Pakhtoon and East Pakistan separatist movements, not to mention the Nagas and the Mizos.Footnote 131

Thus, in keeping with the party line, the Nagas and the Mizos are yet again relegated outside the nation-state, as ‘border’ problems precipitated by the machinations of foreign states.

The communities residing in north-eastern India thus serve the dual role of insider/outsider: interpellated into nationhood when convenient and as signifiers of ‘diversity’ but expunged when deemed too unruly or antithetical to the nation. The rallying cry of ‘diversity in unity’ explored above thus becomes visible here as an expedient ruse; it allows India to celebrate certain kinds of diversity, while disavowing other ‘diverse’ populations as outsiders that threaten the coherence of the nation-state. The very creation of the state of Nagaland in 1963 was the final push in the ‘many efforts to pacify the Nagas’, recalls S. K. Sinha in 2001, then governor of Assam.Footnote 132 The explicit resort to ‘pacification’, a touchstone in the argot of counter-insurgency,Footnote 133 is exemplary of the dual logics of exclusion and inclusion into the Indian polity of the denizens of north-eastern states. ‘The Northeast’ has been represented and governed by Indian state actors as a ‘security problem’. The litany of security legislation, including the AFSPA (1958), the Inner Line Permit, and The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (1967), ensures that a permanent state of exception becomes the default for its populations.

This security legislation dovetails with long-standing extractivist logics and practices at work across north-eastern states, which themselves have a long colonial genealogy. The frontier areas of Assam and its neighbouring regions were designated by the British as ‘backward tracts’, a terminology later changed and subdivided into ‘excluded areas’ and ‘partially excluded areas’, legislative categories that fall outside of the 1935 Constitution of India Act, and therefore outside of the jurisdiction the elected ministry. Instead, they fall under the direct control of the government (in this case of Assam) as stipulated by the ‘Excluded and Partially Excluded Areas’ Order of 1936.Footnote 134 These areas were bordered by ‘Frontier Tracts’ that came into existence in 1942 (including the Naga and Mizo hills), legally ‘casting out’ these spaces from the Constitution of India. Hence, they were deemed to lie outside the ambit of the central government and were instead relegated to the ‘special and individual responsibility of the Governor’.Footnote 135 Sir Robert Reid, who served as governor of Assam between 1939 and 1942, justified this omission of various ‘frontier tracts’ and ‘excluded areas’ from the machinery of ‘normal’ governance. It is telling that the government of Assam (controlled by the British) said to the Simon Commission, tasked with constitutional reform across India, in 1928: ‘In the interests of both the Backward Tracts and of the rest of the Province the present artificial union should be ended. The Backward Tracts should be excluded from the Province of Assam.’Footnote 136

The contingent ‘inclusion’ of excluded areas into the constitution of India post-1947 has bred another strange duality in the politics of the nation. On the one hand, there is a concerted effort to ensure that ‘scheduled tribes’, as the original inhabitants of these regions, are represented politically, often to the detriment of poorer communities, especially second- and third-generation migrants from East Pakistan/Bangladesh as policies of affirmative action and quotas for Scheduled Tribes in the assemblies of the individual states in the Northeast attest through the passing of laws such as the Sixth Schedule.Footnote 137

On the other hand, the ‘foreignness’ of tribes, communities, and Indigenous groups has shaped both attitudes to the region pre- and post-Independence. As Major P. B. Deb notes, ‘People pertaining to hill tribes and hill tracts, tribes of NEFA and Bhils of Rajasthan and Madya Pradesh possess excellent material to be trained as formidable guerilla [sic] warriors. Likewise suitable mountainous, deeply wooded bush, desert and those with ravines or gorges (e.g. Chambal Basin) … are centrally located in our country.’Footnote 138 The ‘people pertaining to hill tribes and hill tracts’ are thus simultaneously Othered but also compared to mountains and deserts ‘located in our country’. This duality is more fully elaborated in Indian author Sanjoy Hazarika’s best-selling Strangers in the Mist, which frames the inhabitants of north-eastern states as ‘strangers’ vis-à-vis mainland India, at once contained within the bounds of the nation-state and yet also spatially cut off from and light years apart from the imagined community that constitutes its spatial and political centre.Footnote 139 The duality is ultimately at the heart of the Indian state’s attempts to disavow the inherent violence at work in its efforts to pacify uprisings across north-eastern states. As with the acknowledgement of the fundamental difference between security forces and locals above, this underscores the tightrope act undertaken by the Indian state to construct ‘the Northeast’ and its populations as simultaneously inside and outside of ‘the nation’.

This oscillating representation of north-eastern states and their inhabitants is certainly a comment on the condition of ‘the Northeast’ and its geographical imagination vis-à-vis the Indian centre. Yet it also speaks the underlying precariousness of the Indian nation-building project. Varma discusses demographic questions at length, arguing thst the recurrence of the problem of insurgency in India reflects a deficiency, which he calls India’s lack of a ‘common trend’:

there is no underlying, deep-rooted common trend such as might be provided by race, religion, or culture in India. The organization of societies ranges from the humblest life of the widely separated tribes in NEFA, Nagaland, Manipur, Tripura, the Khasi and Jantia Hills and the Mizo Hills, the Gonds, Adivasis and other, the aboriginals of the Andamans, to mention only a few, to complex ancient societies such as that of the Hindus.Footnote 140

Thus, while suggesting that Hinduism is more ‘complex’ and superior to other forms of socio-religious organisation, he argues that India’s ‘diversity’ undermines the nation-state’s coherence. It is not much of a stretch to assume that the fissure at the crux of Indian nationhood can be attributed to the attempts by some ancient societies (such as the Hindus) to assert their dominance and superiority over Indigenous groups.

Contra Varma, we insist that insurgency in the Northeast is not due to some incidental ‘lack of common trend’ but is motivated by the political purpose of self-determination by the primary inhabitants of the region – a leitmotif in colonial warfare. This is not to romanticise political uprising, and emphatically not to endorse the violence against the politically expedient construal of some as ‘settlers’ (largely the Muslim population from East Pakistan/Bangladesh). Rather, it is to acknowledge that the Indian state’s hold over north-eastern states is so tenuous precisely because it has been experienced and resisted as a form of colonialism by Indigenous populations.

The simultaneous disavowal and attempted interpellation of these populations into a constructed ‘nation-ness’ is strikingly resonant of colonialisms elsewhere. The native must be ‘schooled’ into compliance, good habits, and law-abiding citizenship, or be exterminated as in the case of settler colonisationFootnote 141 or ghettoised through ‘internal colonisation’. USI Journal shows that these dynamics do not map neatly onto the Indian-state, but that remnants of colonialism and new practices of post-colonisation come into play in the 1970s and 1980s in the prose of Indian counter-insurgency.

Conclusion

We began this article with an image of a young Mohandas Gandhi in the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps as a point of entry into the complexity of the post-Independence Indian state as being both anti-colonial but also invested in the oppressive and racialised logics of colonialism. Through a focus on the prose of Indian counter-insurgency in the pages of USI Journal from 1947 until the 1980s, we have shown how these colonial logics have lived on within India’s long wars, which remain ongoing. Indeed, the seeds of exclusion and incorporation of north-eastern territories and populations into the Indian mainland were sown well before Independence in 1947. The legal acts of exclusion and abandonment that India inherited were a multi-headed monster with durable afterlives. Given this political backdrop, it is no surprise that the fledgling state of India sought to govern these regions with an iron fist as it reproduced discourses about ‘primitive tribes’ with racially inferior characteristics. It is also unsurprising that the experiences of those living in north-eastern states remained qualitatively unchanged, as the Indian state tried to assert mastery over what it claimed as its ‘domestic’ territory. As Julietta Singh argues, the very idea of ‘mastery’ is a colonial construct that is rearticulated and (re)deployed in violent ways by leaders of the Global South.Footnote 142

In north-eastern India, the logics of colonial disavowal continue to reinvent themselves based on political expediency. As we have shown, the long wars that India has waged on its north-eastern inhabitants follows many core logics of Western counter-insurgency, not least in its recourse to a language of necessary violence for the security and preservation of a normatively ‘good’ social order introduced and defended by the nation-state. Yet the terms of the prose of Indian counter-insurgency post-Independence have unfolded in ways that are not entirely reducible to the imperatives of Western imperial and colonial imperatives and forms of reasoning. While similarly committed to rationalising and explaining the irreducibly violent efforts to pacify Indigenous populations and minoritised (non-citizens) and appropriation of land and natural resources, the recuring exceptionalist references to ‘democracy’ and ‘diversity’ index the ways in which the emergent post-Independence Indian state attempts to carve out a place for itself within a world-system. Indeed, whereas Western empires have sought to distance themselves from the places and subjects they intervene in, India’s disavowal of its violence manifests through somewhat-distinct modalities with their own particular tensions and contradictions, underpinned by the imperative of folding occupied peoples and territories into the Indian ‘mainland’ and body politic and claiming them as their own.

Nonetheless, the ways that these wars are conducted by countries in the so-called Global South have largely been elided in the prevailing focus on Western counter-insurgency. Through this article, we have presented a corrective to Eurocentric perspectives on both counter-insurgency and linear narratives associated with Western colonialism. By investigating the particular recourse to the language of democracy and diversity (and of cognate concepts such as unity and secularism) that forms a part of India’s counter-insurgency arsenal, we have sought to tease out the specific contours of India’s post/colonial comportment and the influence this has on its war-making and state-making practices. Our empirical engagement with the archives demonstrates how India’s peculiar post-colonial status and its proximity to, if not affinity with, the populations it is fighting unsettles accepted taxonomies of colonialism and coloniality.

In so doing, our intention is not merely to spotlight local variations of counter-insurgency praxis; it is to reanimate the study of counter-insurgency as constitutively global and rethink colonialism beyond its accepted doctrinal wisdom and spatial parameters in prevailing critical debates. This article provides a springboard for future research on the colonial afterlives and particularities of (violent) ‘governance’ in the Global South after the end formal empire. Moreover, by bringing the international back into IR, we call for research that engages international relations and global power politics and works to fundamentally reorient critical analyses of militarism and martial politics by looking at their loci in the Global South.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank James Eastwood, Sara Salem, and Sharri Plonski for their close readings of previous drafts. The article also benefited from feedback at the 2023 European Workshop in International Studies in Amsterdam.