Introduction

How security communities develop has been one of the most pervasive questions that international relations (IR) theorists have been trying to answer. Deutsch first addressed the issue in the 1950s, primarily outlining the conditions under which a ‘peaceful change’ could emerge within a group of states dealing with anarchy.Footnote 1 In his so-called transactional (or cybernetic) approach, he argued that ‘the capacity of the participating political units or governments to respond to each other’s needs, messages, and actions quickly, adequately, and without resort to violence’ is one of the key conditions for the emergence of security communities.Footnote 2 Drawing on mainstream constructivist insights, Adler and Barnett addressed the issue anew after the Cold War. They emphasised trust and collective identity as the engines that drive the development of security communities.Footnote 3 From a different perspective, Pouliot has more recently advocated a ‘practice turn’, arguing that ‘in social and political life, many practices do not primarily derive from instrumental rationality (logic of consequences), norm-following (logic of appropriateness), or communicative action (logic of arguing)’.Footnote 4 He pointed out that while the relationship between ‘practicality’, ‘consequences’, ‘appropriateness’, and ‘arguing’ is one of complementarity, ‘socialization, learning, and persuasion follow rather than precede practice; at best, they co-evolve’.Footnote 5

These three main theoretical approaches suffer from a similar bias: they are inattentive to the theoretical and empirical complexities regarding how and under what conditions security communities also develop through law at both the systemic (regional) and domestic levels. By (un)consciously failing to take the legal literature seriously, they have encapsulated their theoretical and analytical framework into a kind of ‘iron cage’ that leaves little room for a greater conceptualisation and understanding of security community building through norms and legal and judicial practices. Yet all social communities, including security communities, rely on ‘societal norms’.Footnote 6 Understanding the processes through which these norms are created, internalised, and become ‘embedded’ in domestic legal and political systems could have helped avoid several shortcomings,Footnote 7 for instance, the lack of a convincing explanation for the origins of ASEAN norms and the failure to conceptualise ‘norm robustness’Footnote 8 independently of the effects attributed to norms, leading to tautology.Footnote 9 This, in fact, is a common weakness in the constructivist literature.Footnote 10 As one constructivist acknowledged,Footnote 11 ‘Whether one emphasizes the behavioral or the linguistic/discursive facet of norms, avoiding circular reasoning requires a notion of norm robustness that is independent of the effects to be explained. This is no easy task.’Footnote 12

This lack of engagement with legal works is a missed opportunity to broaden the ontology of security communities, and to bring theoretical heft to some of the fundamental concepts on which security communities rely, for example, ‘dependable expectations of peaceful change’. Indeed, contrary to the constructivist and practice theory approaches, whose focus is on the state elite,Footnote 13 the subject of dependable expectations of peaceful change in Deutsch’s pathbreaking book was the population of the territory covered by the community.Footnote 14 As Collins has argued, ‘the state elite are necessary, but … not sufficient for building a security community. It is the sense of belonging together at the mass level that ensures the “we-feeling” is held by more than a select group of state elite.’Footnote 15 If we are to fully understand how security communities develop, we need a sophisticated theoretical and analytical framework that can capture all the relevant dimensions of this institution, for instance, a Bourdieu-type analysis including legal norms in both the delimitation of social fields and the habitus.Footnote 16

To be sure, considering the concept of security communities as deeply rooted in international political theory,Footnote 17 or studying security communities solely by focusing on IR theory, is not a problem in itself. As many IR scholars have demonstrated,Footnote 18 all these approaches have made significant contributions to our understanding of how security communities develop. The problem rests with the ‘transnational legal process’Footnote 19 (TLP) that fuels reasonable expectations of peaceful change at the regional and domestic levels, but which neither practice theory nor the transactional and constructivist approaches explain.

Take for instance the case of illicit drug trafficking, one of the most salient and persistent threats to regional security, especially in the Western hemisphere.Footnote 20 The study of such an issue, from the perspective of security communities, should also require analysts to study regional norms and legal and judicial practices governing the fight against illicit drug trafficking in the Americas. This in turn raises several theoretical, analytical, and methodological questions, beginning with the definition and conceptualisation of regional norms: what is a regional norm, and how should it be approached in the context of security communities? Where do these norms come from? More importantly, through which mechanisms and practices do such norms penetrate domestic legal systems to the point of creating enforceable legal rights and obligations that, in turn, contribute to maintaining reasonable expectations of peaceful change among the population of a transnational region comprised of at least two sovereign states? Are these mechanisms and practices the same across states or do they vary? If they vary, how can these variations help better understand, explain, and perhaps predict the success or failure – or at least delays – in the development of security communities? Suppose the behaviour of one nation-state switches from the ‘logic of consequences’ to the ‘logic of appropriateness’ (what Checkel has termed socialisation type II), how could one rigorously assess the transformation of an instrumental or grudging complianceFootnote 21 into a legitimate, reflexive, and durable obedience?Footnote 22

Empirical works worth mentioning include Bassamagne Mougnok (2019, 2021),Footnote 23 which show how TLP led to the codification and institutionalisation of Inter-American drug lawFootnote 24 between 1986 and 2009,Footnote 25 and how these processes facilitated the emergence of reasonable expectations of peaceful change within the region through an iterative process of interaction – at various levels (within states and at the level of CICAD, REMJA, OAS-General Assembly, Summit of the Americas, etc.) between various states and private actors (see, e.g., CICAD’s expert groups on model regulations) – and socialisation to best practices and agreed norms in the context of the fight against illicit drug trafficking and related crimes.Footnote 26 Evidence from these works not only sheds light on the ‘norm-generative process’ as a process that is conscious of the two-tiered basis of norms as both fact-based (appropriateness, practicality) and value-based (contentedness, validity) but also reinforces Brunnée and Toope’s argument that ‘law is most persuasive when it is created through processes of mutual construction by a wide range of participants in a legal system’.Footnote 27 Through the lens of transnational law creation, internormativity, and recursivity, TLP provides an avenue for a more comprehensive understanding of ‘dependable expectations of peaceful change’ in the context of security communities, capturing a myriad of normative factors, sites, actors, processes, and outcomes.Footnote 28

I argue that IR scholars can fill these gaps by drawing on the theoretical, empirical, and methodological analyses in international law (IL). This study starts from the premise that to fully understand or explain the development of security communities, it is necessary to move beyond the boundaries and canonical narratives of how IL and IR have evolved as disciplines.Footnote 29 Of course, as Slaughter et al. emphasised, ‘These narratives are valuable both as intellectual history, providing necessary context for current debates, and as bulwarks against ad hoc borrowing of terms and concepts’.Footnote 30 However, and even if one could agree with Cox, to some extent, that theory is always for someone and for some purpose,Footnote 31 it is time to move on. The purpose of this study, therefore, is to start enriching IR understandings of how security communities also develop through ‘regional norms’ and legal and judicial practices by pointing out what IR theory can learn from IL. In so doing, the article joins a larger trend advocating an interdisciplinary turn in the study of world politics.Footnote 32

The argument proceeds as follows. The first section traces the evolution of the concept of security communities, critically reviewing its dominant approaches. I argue that the transactional, constructivist, and practice theory approaches all suffer from a similar bias whose epistemological roots run deep in the traditional divide between IR and IL.Footnote 33 Taking the level-of-analysis question seriously,Footnote 34 including the norm-generative process which remains to be targeted more systematically, the second section proposes a definition and conceptualisation of regional norms. Insights from IL not only reinforce the call to separate the international from the regional levelFootnote 35 but also provide useful clues as to how to approach regional norms in the context of security communities.Footnote 36 The third section discusses the ‘legal internalisation’ of regional norms, highlighting legal and judicial factors that can facilitate or hinder the process and therefore affect the development of security communities. Building on empirical evidence provided by recent works on the focal point theory of (expressive) law,Footnote 37 the fourth section contends that regional norms, once internalised into domestic legal systems, can provide a repertoire of legal focal points around which individuals as well as states coordinate their behaviour and expectations. By helping to solve coordination and distribution problems at the systemic and domestic levels, these focal points contribute to maintaining reasonable expectations of peaceful change at the transnational mass level – that is, as much within states as between states.

The evolution of the concept of security communities

Introduced in the discipline of IR by Richard W. Van Wagenen,Footnote 38 the concept of security communities has gone through decades of heated debateFootnote 39 among scholars without losing its heuristic and practical relevance. Indeed, many scholars and practitioners have been using it.Footnote 40 They even have expanded its original scope to make it more applicable to the study of contemporary IR, broadening its empirical use and positioning it as an alternative concept to other forms of security governance and peaceful orders, such as alliances, regimes, international organisations, and imperial orders.Footnote 41 This section briefly reviews the dominant approaches of security communities, namely transactional, constructivist, and ‘practice theory’.

The transactional approach emphasises the role of social communication and transnational transactions in the construction of a broader sense of community, a ‘we-feeling’ at the international level.Footnote 42 To be sure, in addressing the question of how humanity could learn to act together to eliminate war as a social institution, Deutsch was aware of the existence of political communities where wars, or the threat of using large-scale physical violence as a means of solving disputes, were no longer an option.Footnote 43 He called these political communities a security community, which he conceptualised as:

A group that has become integrated, where integration is defined as the attainment of a sense of community, accompanied by formal or informal institutions or practices, sufficiently strong and widespread enough to assure peaceful change among members of a group with ‘reasonable’ certainty over a ‘long’ period of time.Footnote 44

Without simplifying too much, a security community, from this perspective, refers to a group of political communities whose members continuously share the conviction that whatever the nature and degree of their disputes, they must settle them peacefully. Deutsch even went on to say, by definition, that ‘if the entire world were integrated as a security-community, wars would be automatically eliminated’.Footnote 45 Although this assertion appeared to realist scholars to be extremely optimistic and naive because of the difficulty of cooperation between political units in an anarchic system, it is worth highlighting the originality of Deutsch’s reasoning. While realists were almost exclusively interested in studying the causes of war and analysed it as one of the consequences of anarchy and of the security dilemma, Deutsch reflected on the conditions of peace (like the so-called idealists) and, more interestingly, on a scientific approach to security communities. Peace, in his theoretical framework, was not defined as a truce or a lasting suspension of hostilities among political units in the shadow of past battles or for fear of future ones. Rather, it was defined as a state of relationships where wars or the threat of using large-scale physical violence had become unthinkable. Therefore, he insisted on the ‘long period’, arguing that the unthinkability of wars also depends on the level of mutual trust over a long period.

In designing a scientific approach to security communities, Deutsch distinguished two ideal types, namely amalgamated and pluralistic.Footnote 46 The former refers to ‘the formal merger of two or more previously independent political units into a single larger political unit, with some type of common government after amalgamation’. The latter – the case under study – refers to two or more legally independent political units coexisting peacefully without a common government.Footnote 47 He then identified three conditions under which pluralistic security communities (PSCs) could emerge, namely the compatibility of the core values of political elites; the capacity of the political units to respond to each other’s needs, messages, and actions quickly, adequately, and without resorting to physical violence; and the possibility of predicting the behaviour of the other and acting accordingly.Footnote 48 When Deutsch speaks of ‘core values’, he refers to those values that can foster ‘mutual sympathies and loyalties’ (a common political ideology, for example). According to him, it is indeed necessary to distinguish essential values from non-essential ones – like religion, to use his example. The observance of such a prerequisite can help bring the participating political units closer and encourage transnational transactions. It is through these collusive transactions that political units will learn to know each other and share fears as well as expectations for peaceful change (second condition). As for the third condition, he contended that as soon as political units trust each other over a long period, they become able to predict each other’s behaviour and act accordingly.

Overall, the transactional approach has led to promising generalisations about the conditions under which PSCs could emerge.Footnote 49 Throughout the Cold War, however, this approach remained in the shadow of the so-called materialist and rationalist IR approaches, probably because of the conceptual, theoretical, and methodological shortcomings raised by Adler and Barnett.Footnote 50 Moreover, perhaps because of the dominant (neo)realist’s view of IL as being ‘an epiphenomenon concealing temporary cooperation among power – or security – seeking states’, the transactional approach paid little attention to the role of law in the development of PSCs. Although Deutsch later acknowledged ‘the need and the potential demand for law and law enforcement at the international level, he was still speaking in terms of ‘probability of international law’.Footnote 51 Thanks are due to Adler and Barnett, who – taking advantage of the systemic changes surrounding the end of the Cold War – pulled Political Community and the North Atlantic Area out of its theoretical anonymity.

In their efforts ‘to resurrect the concept’, Adler and Barnett refined Deutsch’s framework by taking intersubjective structures seriously, including transnational interactions, power, and security practices.Footnote 52 They also exploited the conceptual architecture of a security community in order to provide an alternative view of the dynamics underlying the development of security communities.Footnote 53 This led them, first, to focus on PSCs, which they defined as ‘a transnational region comprised of sovereign states whose people maintain dependable expectations of peaceful change’ – peaceful change meaning ‘neither the expectation of nor the preparation for organized violence as a means to settle interstate disputes’.Footnote 54

Building on several empirical works, they then identified three conditions under which PSCs could develop. The first condition is what they termed ‘precipitating factors’. These are situations where states are individually and collectively dealing with a common transnational issue that forces political elites to coordinate their policies. The second condition is a positive and dynamic relationship between the ‘structure’ and ‘social processes’. By structure, they mean power and knowledge.Footnote 55 Regarding social processes, they refer to the need to take transactions and social learning seriously. According to them, without transactions, there is no social learning; communication enables mutual understanding and conveys representations of the world, as well as expectations for peaceful change. The third condition is mutual trust and collective identification.Footnote 56

Unlike Deutsch, whose work was limited to studying the conditions of the emergence of security communities, Adler and Barnett moved deeper by suggesting three stages of the development of PSCs, namely, nascent, ascendant, and mature.Footnote 57 In the nascent stage, states begin to consider how they can coordinate their policies in order to enhance mutual security, reduce transaction costs, or encourage reliable and predictable new social and political interactions. Such initiatives do not initially aim at creating a PSC;Footnote 58 but because they are motivated by the awareness of a common transnational issue, they promote interactions between participating states. It is through these interactions that regional institutions are created in order to foster cooperation, uncover new areas of mutual interest, shape common norms, and help build a common identity.Footnote 59

The ascendant stage sees a deepening of mutual trust and the emergence of a collective identity. Because transnational interactions are intensifying, and because they contribute to socialisation and social learning, Adler and Barnett contend that they favour mutual trust and collective identification. Something akin to a pacifist ‘habitus’ develops during this stage, fostering reasonable expectations of peaceful change.Footnote 60 As for the mature stage, it is characterised by a high level of mutual trust and collective identification.Footnote 61 Mature PSCs can be ‘loosely’ or ‘tightly’ coupled depending on whether their members retain separate identities and institutions. The indicators illustrating the existence of loosely coupled PSCs also apply to tightly coupled PSCs. But to distinguish the two, Adler and Barnett identified indicators that apply only to the latter.Footnote 62 For example, a ‘multiperspectival’ polity – rule is shared at the national, transnational, and supranational levels – and the ‘internalization of authority’,Footnote 63 which refers to the process by which authority and governance structures extend beyond national borders to include international organisations and institutions.Footnote 64

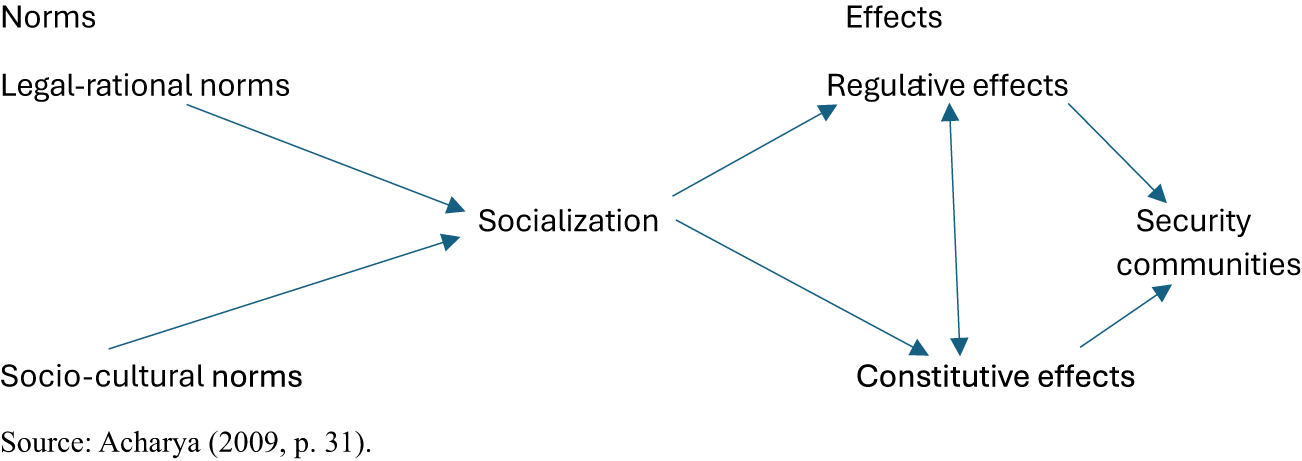

Insisting on the origins of collective identification, Adler and BarnettFootnote 65 suggest it is something actors learn through shared meanings and norms.Footnote 66 Once they collectively recognise the shared meanings and norms they have learned (or developed through behaviour), their new knowledge becomes an active component in the production and reproduction of order among them.Footnote 67 Of course, this is one of the key contributions of constructivist scholars, stating that agents (states) and structures (international norms) are mutually reinforcing and constituted.Footnote 68 Acharya drew a useful distinction in this regard between ‘legal-rational’ norms and ‘socio-cultural’ norms in the context of PSCs.Footnote 69 While the former refers to ‘formal rationalistic principles of law’, the latter refers to ‘the basis of informal social control and social habits’. As illustrated in Figure 1, both play an important role in the development of PSCs. ‘By making similar behavioral claims on different states, [they] create parallel patterns of behavior among states over wide areas.’Footnote 70 These patterns vary according to the nature and degree of internalisation, however.Footnote 71 That is why building on the logic of appropriateness,Footnote 72 Adler and Barnett hypothesisedFootnote 73 that:

Security community can count for compliance on the acceptance of collectively-held norms … because some of these norms are not only regulative, designed to overcome the collective action problems associated with interdependent choice, but also constitutive, a direct reflection of the actor’s identity and self- understanding.

Figure 1. Norms, socialisation, and security communities.

To sum up, PSCs are socially constructed. Their development relies mainly, but not exclusively, on intersubjective structures, such as norms, trust, and identity. While the focus on the importance of norms is welcome, the constructivist approach tells us little about the processes through which these norms are created, internalised, and become ‘enmeshed’ in domestic legal and political systems to the point of facilitating, maintaining, or fostering reasonable expectations of peaceful change at the transnational mass level. As Jervis rightly emphasised, ‘it is one thing … to point to the importance of regulative and constitutive norms, shared understandings, and common practices. It is quite another to say how norms are formed, how identities are shaped, and how interests become defined as they do.’Footnote 74

These gaps are not the preserve of the constructivist approach. The theory of practice of PSCs also fails to account for these dimensions. This is not surprising, however, since Pouliot did not pay attention to the legal literature, as can be seen at first glance in his references.Footnote 75 Although he implicitly acknowledged the relevance of norms and legal and judicial practices by emphasising the complementarity between ‘practicality’, ‘consequences’, and ‘appropriateness’,Footnote 76 he was not interested in understanding the normative or practical conditions under which PSCs could also develop through law. Rather, one of his main objectives was ‘to bolster the practice turn in IR theory by offering an in-depth discussion of the logic of practicality’.Footnote 77 According to this logic, if we want to better understand the development of PSCs, it is more productive to start with practice than with collective identification, because collective identity is at best embedded in practice.Footnote 78 Put differently, instead of conceiving ‘we-ness’ as the driver of practice – that is, a representation that precedes action – the practice theory approach suggests construing collective identification as the result of practice.Footnote 79 It represents ‘an invitation to see the agent not as the locus of representations, but as engaged in practices, as a being who acts in and on a world’.Footnote 80

All in all, the theory of practice of PSCs focuses on ‘what security practitioners actually do when they interact’.Footnote 81 Surprisingly, it evacuates the whole issue of rules enabling or governing those interactions.Footnote 82 Yet, as Lamp showed,Footnote 83 rules are implicated in practices in at least three ways: they constitute a pattern of action as a ‘practice’; they regulate the conduct that makes up the practice; and they provide a formula for extending and adapting the practice to ever new situations.Footnote 84 Taking the IL literatureFootnote 85 seriously promises to help overcome the above-mentioned gaps, whether studying PSCs from the transactional, constructivist, or practice theory perspective.

On regional norms

Although there are no legal works dealing with PSCs, there is an abundant literature on ‘socio-legal theory and methods’,Footnote 86 including the TLP literature,Footnote 87 which can help better understand ‘the force of law’ in the context of PSCs. Building on the legal literature, this section deals with the definition and conceptualisation of regional norms.Footnote 88 I propose first to distinguish between ‘legal’ and ‘non-legal’ norms at both the domestic and international levels, since a regional non-legal norm can become a domestic legal norm through ‘the logic of internormativity’.Footnote 89 This distinction will not only help shed light on the cross-referencing interplay between regional norms and domestic legal norms in the development of PSCs but will also ease the definition and conceptualisation of regional norms, including the analysis of various legal and judicial dynamics that shape reasonable expectations of peaceful change at the regional and domestic levels.

Legal and non-legal norms in domestic and international law

Contrary to IR scholars who seem to agree on the definition of the norm ‘as a standard of appropriate behavior for actors with a given identity’,Footnote 90 the issue of defining norms is still controversial in Law.Footnote 91 Millard even argued that it would be illusory to characterise what a (domestic) legal norm is, especially if one focuses on its ontological dimension. According to him, one can only pinpoint some elementary consequences that the reference to a legal norm implies and seek a minimum consistency requirement for its use.Footnote 92 Indeed, the term, when not used carefully, can lead to confusions, as Finnemore and Sikkink have shown.Footnote 93 ‘But used carefully, [it] can help to steer scholars toward looking inside social institutions and considering the components of social institutions as well as the ways these elements are renegotiated into new arrangements over time to create new patterns of politics.’Footnote 94

Drawing on Kelsen,Footnote 95 several legal scholars nonetheless define norms as the meaning of a proposition prescribing individuals or institutions a pattern of behaviour.Footnote 96 Here, the norm expresses the idea that an actor must behave in a certain way. It is a devoir être (sollen) and, as such, imperative in essence. However, norms do not only articulate obligations since in practice their contents are often a combination of rights and obligations that one can extract through an exegetical interpretation.Footnote 97 It seems more appropriate to consider that they articulate obligation, permission, and interdiction.Footnote 98 But in domestic systems, what makes certain norms so different from others to the point of being labelled ‘legal’? Kelsen emphasised ‘the sanction’,Footnote 99 but as many scholarsFootnote 100 noted, sanction is not the preserve of domestic legal norms since we can find it, with all its various components, in ethical experiences, for example. Drawing on Amselek’s conceptualisation,Footnote 101 this study considers that the only thing specific to domestic legal norms, and what precisely makes them ‘legal’, is the status of public authority of the leaders who create, interpret, and institutionalise them in the context of national governance.Footnote 102

The reality is somewhat different with respect to international legal norms whose formal sources are listed in the article 38(1) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice. According to this provision, the sources of IL are treaties signed by two or more subjects of IL, customs, and general principles of law. Members of the international community have set up two other ways of creating international legal norms through treaties, namely the resolutions of multilateral organisations and the decisions of judicial or arbitral tribunals.Footnote 103 It follows that international legal norms are those created from one of the above-mentioned sources and, more importantly, they are legally binding – legally binding meaning their violation entails legal consequences (in principle at least). This is key to understanding the difference between international legal norms and the so-called non-legal, pre-legal, or para-legal norms which are not legally binding (soft IL).Footnote 104

Before delving into the definition and conceptualisation of ‘regional norms’, note that at the systemic (regional) level, the concept of ‘norm’ encompasses both legal norms that are practised and socially internalised, as well as socio-cultural and behavioural norms that are eventually codified into law or contribute to the codification of law, whether it be hard, soft, or some combination of the two.Footnote 105 At the domestic (states) level, the focus is on ‘legal’ norms, considering social groups and communities, as well as organisations within states as ‘semi-autonomous social fields’,Footnote 106 and including these specific norms in both the delimitation of social fields and the ‘habitus’.Footnote 107

Regional norms: Definition and conceptualisation

Since the end of the Cold War, IR scholars have been studying ‘the region’ as one of the most relevant levels of analysis.Footnote 108 Paradoxically, its definition and conceptualisation have raised a lot of controversy in the discipline. For instance, Nye defined regions as a ‘limited number of states linked together by a geographic relationship and by a degree of mutual interdependence’,Footnote 109 whereas Grugel and Hout contended that ‘although territoriality is a sine qua non of regions … they are not naturally constituted geographical units nor the straightforward “common-sense” expressions of shared identities’.Footnote 110 Regions, they argued, are made and re-made, and their membership and frontiers are decided through political and ideological struggle and through the conscious strategies of states and other social actors.Footnote 111 Not so distant, finally, is Adler and Barnett’s conceptualisation,Footnote 112 which suggests the geographical criterion should not be considered a necessary condition since states situated in very separate geographic areas could create ‘cognitive regions’.Footnote 113

Starting from the premise that ‘the whole regionalist approach [hangs] on the necessity of keeping and the ability to keep analytically separate the global and regional levels’,Footnote 114 I consider Nye’s definition of the region – which is similar to that of FawcettFootnote 115 and DeutschFootnote 116 – as one of the most appropriate to the study of regional norms. In my view, a definition that hardly pays attention to ‘territoriality’ not only conflates the international and regional levels into one level; but, as Buzan and Wæver have argued,Footnote 117 it also ‘voids the concept of region, which if it does not mean geographical proximity does not mean anything’, particularly in the context of new regionalism.Footnote 118 Hence, I suggest considering countries that share a history, culture, values, or interests, but which are not linked by a geographic relationship (e.g. Commonwealth or oil-producing countries), as a group; at best, as a community,Footnote 119 not a region.Footnote 120 As Herz emphasised,Footnote 121 the term region originates in fact from the idea of rule, as in regere, command. Taking the level-of-analysis problem seriously, we should be considering regions and their product – regional organisationsFootnote 122 – as the locus for the production of ‘regional norms’, with regional norms referring to special international norms whose scope of application is not general, and which govern the interactions among states within a given geographical area. Without a clear and systematic organisation of elements, however, it will be nearly impossible to properly use this concept in order to shed light notably on the conditions under which such norms (could) play a pivotal role in facilitating or maintaining reasonable expectations of peaceful change. This raises the question of the conceptualisation of regional norms: how should they be approached in the context of PSCs?

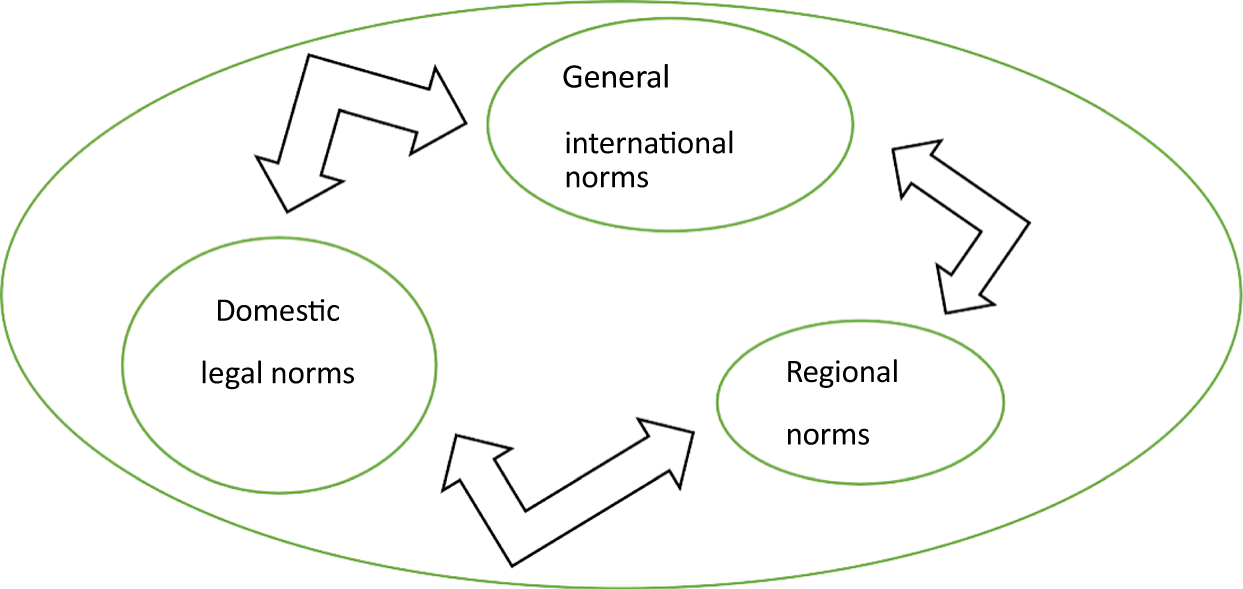

To answer this question, I first outline what I call ‘the socio-legal universe of PSCs’,Footnote 123 which is comprised of general international norms (universal law), regional norms (regional law), and domestic legal norms (domestic laws). As illustrated in Figure 2, which additionally shows the legal pluralismFootnote 124 surrounding the development of PSCs, these three categories of norms are cross-referenced and interplay. As we shall see later, this cross-referencing interplay, especially between regional norms and domestic legal norms, critically contributes to fostering reasonable expectations of peaceful change at the transnational societal level by providing a common legal frameworkFootnote 125 to state and non-state actors, as well as ‘legal focal points’ that help solve coordination and distribution problems within states, between states, and beyond states.Footnote 126

Figure 2. The socio-legal universe of security communities.

Contrary to Adler and Barnett’s opinion that ‘a security community which depends heavily on enforcement mechanisms is probably not a security community’,Footnote 127 I suggest construing the legalisationFootnote 128 of PSCs as a two-level game involving horizontal interactions among states (systemic level) and a vertical process of internalisation.Footnote 129 This TLP is a key variable that has been overlooked. While I agree with Adler and BarnettFootnote 130 that ‘soft legalisation’ might be desirable at the systemic level,Footnote 131 I contend that peaceful change in domestic societies rests mostly on the (expressive) power of law.Footnote 132 This is because actors – whether the state apparatus, government and opposition elites, interest groups, individuals, or other social actors – ‘must have some binding sense of obligationFootnote 133 to the law before it becomes viewed as the appropriate standard of behavior’.Footnote 134 Of course, people might comply with domestic law out of sense of moral duty.Footnote 135 But since we cannot directly peer into the consciences of millions of individuals,Footnote 136 it seems more productive and transparent to start with a binding sense of legal obligation and an identifiable course of appropriate action.Footnote 137 This added transparency, from a heuristic perspective, should make it easier to track, assess, and better understand how various actors are socialised through domestic legal norms,Footnote 138 and how this process of socialisation facilitates the coordination of behaviours and expectations of peaceful change at the transnational societal level.

Second, building on Barberis,Footnote 139 I define three scopes of application (i.e. dimensions) of a regional norm, namely spatial, personal, and material. I exclude the temporal one, since it may vary notably depending on the norm’s life cycle.Footnote 140 As a general proposition, a norm can be applicable all over the world or in one region or country; the geographic space within which the norm is applicable is referred to as its spatial scope of application. Norms also have a personal scope of application, which identifies the subjects to whom they apply. For instance, some norms may refer to all the inhabitants of a country (e.g. civil law or criminal code), whereas others may concern specific groups (civil servants, refugees, etc.). Finally, the behaviour prescribed by a norm is referred to as its material scope of application: the material scope is always defined with reference to human behaviour which may be authorised, prohibited, or obligatory.

Most legal scholars agree on two necessary conditions for the identification of regional norms.Footnote 141 The first one deals with the spatial scope of application of the norm, which must be limited to a given transnational region. In other words, a regional norm must not pretend to be applicable all over the world (universal law). Rather, it must meet the specific needs of a region (see, e.g., the first introductory paragraph of the Inter-American Convention against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Ammunition, Explosives, and other Related Materials, which clearly indicates the spatial scope of application of the Convention).

The second condition refers to the personal scope of application of the norm, which must be limited, too. It should be noted that an international norm can be limited solely in its spatial scope of application. For example, member states of the international community can agree on norms of sailing on the high seas or fishing in the Indian Ocean. Conversely, another international norm can be limited solely in its personal scope of application. The Benelux states, for instance, can agree to open joint embassies in the United States, China, or South Africa. In both cases, we are not in the presence of a regional norm since the two conditions are not met. By contrast, imagine that member states of the Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) ratified an agreement that authorises their citizens to travel within the CEMAC zone without a visa, the presentation of a national identity card being the necessary and sufficient condition. Here, both the spatial (CEMAC zone) and personal conditions (citizens of the member states) are met.

It follows that an international norm is said to be regional only if its spatial and personal scopes of application are both limited. But if this norm prescribes the same behaviour as that of general IL, then it probably is nothing special. Hence, the need to also examine the material scope of application of the norm, which must be different from that of general IL.Footnote 142 This difference can be found in what the norm prescribes as authorised, prohibited, or obligatory.Footnote 143 It can even happen that such a norm does not prescribe anything different but establishes a source of law distinct from those of general IL.Footnote 144 It would be a mistake, however, to assume that such differentiation entails the fragmentation of general IL, since a set of general international rules remains valid and applicable to all international relations, forming the general framework from which regional normsFootnote 145 are negotiated, elaborated, and institutionalised.

To sum up, an international norm is said to be regional only if its spatial and personal scopes of application are both limited, and its material scope of application is different from that of general international law. This conceptualisation allows us to keep analytically separate the global and regional levels, while also providing keys for a more systematic approach to targeting the norm-generative process in the study of PSCs. It can also be helpful in better understanding how the regional is very often, but in different ways, produced in conjunction with the evolution of domestic societies, including how such a ‘transnational field’Footnote 146 is renegotiated over time to maintain reasonable expectations of peaceful change at the transnational mass level.

The legal internalisation of regional norms

Legal internalisation is defined as the process by which a regional norm is incorporated into the domestic legal system and becomes domestic through executive action, legislative action, judicial interpretation, or some combination of the three.Footnote 147 Understanding this process in the context of PSCs matters not only because it is a key variable in explaining the pivotal role regional norms play in the ‘constitution’Footnote 148 of state and non-state actors, but also because it is at the domestic level where regional norms gain their authority in the way that all citizens of a state, from the leaders to the general populace, are bound by their tenets – the tenets which form the general framework within which all decisions are made.Footnote 149 Put differently, internalising regional norms into the domestic legal system makes those norms part of domestic law in a way that their violations become violations of domestic law and are then subject to the same enforcement and adjudication mechanisms as all other domestic law.Footnote 150

It follows that the easier the legal internalisation in different domestic systems, the more likely it will be that regional law considerationsFootnote 151 form part of the basis for the lawful and appropriate course of action within a given transnational region.Footnote 152 The nature and speed of legal internalisation varies across states, however.Footnote 153 For instance, in legal systems where it is more difficult or time-consuming to transfer IL provisions from the level of diplomats to the level of domestic law, attention and adherence to IL have proven difficult.Footnote 154 This suggests that, in addition to help broaden the ontology of PSCs, understanding the legal internalisation of regional norms can help explain variations in the pace of development of reasonable expectations of peaceful change across states and within a security community. This in turn can contribute to a better understanding or explanation of variations across PSCs. Finally, understanding this process can be useful in predicting a wide range of systemic issues, including, as we shall see, variations in the level of legalisation of PSCs.

This third section concentrates on the legal internalisation of regional treaties. I do not deal with the other important and similar issue of customary IL, nor am I concerned with the states’ treaty-making idiosyncrasies.Footnote 155 Rather, like many other works that consider the importance of legal internalisation by focusing on factors that facilitate or hinder the process,Footnote 156 I seek to draw attention on two institutional factors that can affect the development of PSCs, namely, the attitude of states towards IL and institutional similarity between domestic and IL.

The attitude of states towards IL: Monism versus dualism

Whether a state adopts a ‘monist’ or ‘dualist’ attitude can significantly influence how easily regional norms will be internalised into the domestic legal system.Footnote 157 By definition, a monist state is one in which, after ratification or government acceptance of a principle of IL, that law automatically becomes part of the domestic law of the state and can be applied by state courts and relied on by citizens of that state.Footnote 158 This does not mean that in monist statesFootnote 159 the ratification of a regional treaty automatically integrates the treaty provisions into the domestic societal perceptions of law, since the norm internalisation process still occurs.Footnote 160 What it means is that legal internalisation may be facilitated by the absence of additional layers of institutional involvement before the regional norm has a chance to cascade into the domestic societal consciousness.Footnote 161

The situation is different in dualist states,Footnote 162 where at least one additional action is required to make the treaty part of domestic law. Here, although the treaty binds the state internationally upon its ratification, that act alone does not have the legal consequence of translating the treaty provisions into domestic law, because IL and domestic law are considered to be two distinct, equal, and independent orders.Footnote 163 This is why it is generally said that for a treaty rule to operate in the domestic legal system of a dualist state, there must be an ‘act of transformation’,Footnote 164 that is, an action by which a government translates the treaty provisions into national legislation, setting out in detail the various obligations, powers, and rights stemming from those international provisions.Footnote 165

As Zartner notes,Footnote 166 one of the key blockages which must be overcome in dualist systems is that there are additional political entities brought into the legal process, and the greater the number of actors that must be involved, the more difficult it becomes for regional law provisions to rapidly become part of domestic law. Here, the process usually takes longer than in states where internalising action is solely within the purview of one branch of the government. The situation is far more complicated in those federal systems where not only do treaties have to pass muster among the legislative or judicial branches at the federal level but must also overcome any objection at the substate level.Footnote 167 Clearly, this contributes to delaying legal internalisation, which in turn may impact, at least, the speed of development of a PSC. To better capture the socio-legal implications of these two major approaches to ILFootnote 168 in the context of PSCs, consider Mexico (a amonist state) and Canada (a dualist state), both having duly ratified a treaty which includes the following provision:

With respect to the right to own land within the territory of either contracting party, citizens of the states’ parties shall receive equal and non-discriminatory treatment.

The intent here is to balance the rights of the citizens of both states within the jurisdiction of each contracting party. But imagine that in each of these states, a citizen of the other party has been refused the right to own land by the local government, even though the treaty provision unambiguously states this right.Footnote 169 In that case, does a Canadian citizen have legal standing in Mexican domestic courts and vice versa? Based on the preceding distinction between monist and dualist states, a Canadian citizen will indeed be able to sue in the domestic courts of Mexico. The reverse, however, may not obtain for a Mexican citizen, who will not be able to sue in Canada’s courts unless the treaty provisions have been incorporated into Canadian domestic law.Footnote 170 Legal and judicial practices of member states of the European Union (EU) provide an additional illustration.Footnote 171 As Zartner notes:

Individual member states of the EU each have monist or dualist positions ingrained in their domestic legal structures. … Upon joining the European Union, however, each member state agrees to essentially act as a monist state in relation to European Union law. Particularly in the case of EU regulations, EU law is held to be immediately applicable in member states without further action [on] the part of domestic legislatures. Moreover, because the European Union has begun to legislate at the regional level on a number of subjects that are traditional topics of international treaties – such as human rights and the environment – this has allowed even dualist states that are members of the EU to more easily internalise certain international legal provisions into their domestic systems.Footnote 172

Institutional similarity between domestic and international law

Institutional similarity between domestic law and IL can also play an important role in facilitating or hindering the legal internalisation of regional treatiesFootnote 173 and, therefore, affect the development of a PSC. Indeed, several works support the conjecture that states where there is institutional similarity between the structures of domestic law and IL are more prone to negotiate and accept IL as valid and binding.Footnote 174 For instance, Powell and Weigand showed that domestic legal systems influence states’ choices of peaceful dispute resolution methods.Footnote 175 They noted that ‘in order to increase familiarity with rules of peaceful resolution of disputes, states use their domestic legal systems to provide them with clues about the most trustworthy ways to settle disputes, and they tend to choose methods of dispute resolution that are similar to those embedded in their domestic legal systems’.Footnote 176 Similarly, insisting on the role of legal traditionsFootnote 177 in states’ preferences towards the legal design of international courts, Mitchell and Powell argued that a state’s internal laws largely determine how states negotiate, draft, interpret, and internalise international commitments.Footnote 178 Specifically in states where the judicial branch has substantive power to make and interpret law – common law tradition – the internalisation of IL can be hindered because the judiciary at the international level is not responsible for lawmaking, only law application.Footnote 179 Thus, states like the United States which follow the rule of precedent (stare decisis) may have greater difficulty internalising IL than states like France – in the civil law tradition – which do not adhere to this rule, because IL does not formally adhere to the doctrine of precedent the way common law systems do, aligning more closely with civil law traditions.Footnote 180

These observations provide us with a basis for addressing or predicting the legalisation of PSCs at the systemic level. Indeed, based on the degree of formalism and the features of domestic legal systems, one can distinguish several dyads at the international level, notably civil law, common law, and Islamic law.Footnote 181 As Powell and Weigand showed,Footnote 182 civil law dyads prefer more legalised dispute resolution methods, since civil law tradition promotes a high formalism and strict interpretation of legal rules and principles. Also appealing to civil law dyads is the fact that international adjudication entails judicial decision-making within a well-defined framework of IL. Common law dyads, on the other hand, prefer less legalised methods – that is, ‘softer forms of legalization’Footnote 183 – since interpretation of rules and principles in this system entails a free and dynamic process. Common law dyads especially prefer negotiations and non-binding third-party methods (‘low delegation’), since all of these involve relatively flexible mechanisms. Finally, ‘Islamic law dyads prefer nonbinding third party because Islamic law embraces simple reconciliation between the contestants guided by an insider (the qadi) and speaks against formalized adjudication’.Footnote 184

Clearly, the legalisation of PSCs may vary at the systemic level depending on the participating states’ legal systems and traditions. This is because ‘Domestic law influences not only the willingness of states to utilize legalized dispute resolution methods in world politics but also delineates the strategies that states will be most comfortable employing on the international scene’.Footnote 185 If it is correct that states often choose binding arbitration and adjudication as effective means of solving disputes peacefully,Footnote 186 then there should be no a priori reason to presume that a security community which relies heavily on enforcement mechanisms is not a security community.Footnote 187 After all, what characterises a security community is the peaceful resolution of conflicts among its members – that is, ‘peaceful change’.Footnote 188 Of course, Adler and Barnett conceived of collective identification as one of the two ‘necessary conditions of dependable expectations of peaceful change’, the other condition being trust.Footnote 189 But as Pouliot has shown, collective identification is not a necessary condition for pacification. Peace can exist as a social fact when (non-coercive) diplomacy becomes the self-evident practice among security elites to solve interstate disputes.Footnote 190 Importantly, as mentioned above, when we talk of peaceful change, we should not be concerned only with interstate disputes, but equally with large-scale physical violence within domestic systems.

Regional norms, legal focal points, and security communities

To understand how regional norms contribute to maintaining reasonable expectations of peaceful change at the transnational mass level, it seems more appropriate to focus on a different but complementary logic of strategic interaction, that is, coordination.Footnote 191 Coordination is pervasive in PSCs. States as well as millions of individuals need to coordinate their behaviour and expectations in order to reach an equilibrium – peaceful change – in mixed-motive and (tacit) bargaining games involving multiple equilibria. In other words, several different outcomes are rationally possible in these games, but actors’ expectations must converge towards a particular outcome. The strategic problem, therefore, is selecting one means of coordinating among many, capable of creating, aligning, and maintaining actors’ expectations of peaceful change.

Decades ago, Schelling suggested that, in exactly these sorts of situations, certain ‘solutions’ stand out from the others as the sort that will attract the attention of the players. He called these special solutions focal points, which he defined as everything that is salient. For example, a pattern of behaviour, a strategy, an outcome, anything that leads the players to perceive an outcome as the solution of the game.Footnote 192 Focal points, from this perspective, help solve coordination and distribution problems by providing ways for actors to ‘coordinate their expectations’. Specifically, they first allow coordination by making actors’ expectations converge on a specific solution and, second, maintain coordination by reinforcing the coherence of individual expectations regarding everybody else’s behaviour.Footnote 193 The identification or emergence of focal points is particularly important in ‘tacit bargaining’,Footnote 194 which happens within security communities – on a vast scale, as among millions of citizens who cannot possibly all talk to each other, and on a small scale, as among regional leaders who cannot say or communicate everything they might wish. Because it is impossible to explicitly coordinate action in such situations, the implicit appeal of focal points – that is, ‘tacit coordination’Footnote 195 – becomes decisively important.Footnote 196

Recently, drawing on the insights of Schelling and others, several scholars have shown that law can serve as a legal focal point or help construct legal focal points through regulation, arbitration, or adjudication, both at the international and domestic levels.Footnote 197 Building on these empirical findings, the remainder of this section briefly discusses the role of regional norms as legal focal points, explaining how a transnational legal process can enhance expectations of peaceful change and strengthens a security community. The point here is not to be exhaustive,Footnote 198 but rather to draw attention to the untapped potential of IL in better understanding how reasonable expectations of peaceful change emerge and are held not only at the systemic or state elite level, but equally at the domestic mass level.

At the systemic level

Consider as an example the case of territorial disputes. Empirical evidence suggests that regional norms can serve as legal focal points in such situations if the legal principles relevant to the dispute are clear and well established,Footnote 199 and if one of the states in the dispute has a stronger legal claim to the disputed territory.Footnote 200 Of course, this presupposes that IL and legal principles are ‘common knowledge’ among states – having been established through either formal means (e.g. treaties, agreements, court rulings) or less formal means (e.g. customary IL, writings of legal scholars) – and that IL provides a common set of standards to assess the relative merits of competing claims.Footnote 201 As Huth et al. observed, this latter feature of IL is particularly important for resolving distribution problems because it provides a means of identifying which of the many potential ways to divide the contested territory the leaders should choose.Footnote 202 To be sure,

By narrowing the bargaining range, the focal point solves both coordination and distribution problems by identifying which of the many possible settlements to start with. It also makes negotiations more efficient by discouraging parties from offering terms their adversaries would reject with certainty. Consequently, even though the existence of a distribution problem necessarily implies that parties have divergent preferences regarding the settlement terms, a focal point that identifies a single solution to the dispute can affect leader behavior.Footnote 203

It follows that the emergence or identification of a regional legal focal point can significantly increase the probability that two neighbours will peacefully settle their dispute through negotiations or adjudication.Footnote 204 As an empirical illustration,Footnote 205 take the territorial dispute between Peru and Ecuador, settled in 1998, in which a legal focal point that favoured Peru was identified.Footnote 206 As Carter et al. reported:

Argentina, Brazil, and Chile (the ‘ABC’ powers) all made it clear that [IL] favored Peru. … In particular, and consistent with the legal focal point that favored Peru, the United States and the ABC regional powers conveyed to Ecuador the need for a settlement based on the 1942 Rio Protocol … As mediators of the dispute, the weight of the ABC states’ united interpretation … reinforced the movement toward peace. In a 1998 letter to the editor of the Wall Street Journal, Ecuador’s ambassador to the United States was confident enough to call the state a ‘peaceful island in the continent’ and to tout Ecuador’s deepening economic integration – even though a settlement was only just appearing on the horizon.Footnote 207

Overall, this suggests that at the systemic level, regional norms help solve coordination and distribution problems between member states of a PSC. By providing a common legal framework and facilitating the identification of legal focal points, they contribute to (1) fostering effective cooperation and coordination, ensuring that all parties have a ‘common knowledge’; (2) promoting consistency in legal interpretations and applications, reducing misunderstandings and the likelihood of large-scale physical violence; (3) enhancing confidence and trust, strengthening the belief in mutual security and peaceful change; (4) and fostering stable and predictable interactions, leading to a more cohesive and resilient interstate community.

At the domestic level

Recall that, once internalised into domestic legal systems, regional norms become part of domestic laws.Footnote 208 According to ‘the constitutive theory of law’, law helps structure the most routine practices of social life by either eliciting compliance or generating acts of resistance.Footnote 209 In most instances, it also provides the framework for legitimate discourse and action and defines what are to be considered legitimate needs, claims, and aspirations, circumscribing the array of legitimate means for their satisfaction and fulfilment.Footnote 210 Finally, by imposing constraints and affording opportunities for individual and collective action, domestic laws, in all these ways, become part of the ‘reality’ within which social actors must live their lives and coordinate their behaviours.Footnote 211

This suggests that norm internalisation in domestic legal systems is critical in the context of security community-building for several reasons:

Consistency and coherence: When domestic laws align with regional norms and principles, it ensures consistency and coherence across member states. This alignment not only helps create a harmonised approach to security issues but also fosters mutual trust and cooperation. Commitment to shared values: By internalising norms, states demonstrate their commitment to shared principles. This commitment strengthens the collective identity of the community, while also reinforcing the belief in mutual security and peaceful change. Effective implementation: Internalised norms are more likely to be effectively implemented and adhered to by the population and institutions within a member state (at least in highly democratic countries). Conflict resolution: Internalised norms provide a framework for resolving disputes that may arise within the region. Having a common legal framework allows for more effective and consistent conflict resolution, maintaining stability and cohesion within the community. Building trust: By internalising norms that reflect regional needs and values, states demonstrate their reliability and commitment to a shared security agenda. This helps build and reinforce trust among community member, facilitating more effective cooperation, coordination, and collaboration in addressing security challenges at the transnational level. Transnational impact: When states integrate community’s norms into their domestic legal systems, it sets a precedent and encourages other states to follow suit, contributing to the broader diffusion of these norms and strengthening the overall regional security community.

Several legal scholars have shown that where there are multiple self-enforcing coordination equilibria, law can serve as a focal point institution to deliberately select an equilibrium.Footnote 212 For example, taking the case of a property dispute, McAdamsFootnote 213 and MyersonFootnote 214 argued that ‘a rule that deemed the immediate possessor of a piece of property to be its rightful owner can coordinate the strategies of rival claimants so as to avoid wasteful contests over the property. If both claimants expect the other to apply the concept of “rightful” ownership, then the “rightful” owner will rationally claim and the other will rationally recede.’Footnote 215 Similarly, in testing ‘the focal point theory of legal compliance’, McAdams and Nadler demonstrated that, in certain circumstances, domestic laws generate compliance not only by sanctions and legitimacy, but also by facilitating coordination around a focal outcome.Footnote 216

At the transnational mass level

Suppose that states A, B, C, and D in region X agree to a customary norm among themselves, such as to prohibit arms sales to rebels operating in the region. At some point, rebels start fighting the government in A. An arms dealer in B sends arms to the rebels in A. State A complains to state B, which triggers a transnational legal process. State B (or some other actor) initiates actions to domesticate the customary norm prohibiting arms sales and enforce it against the arms dealer. As a result of this legal process, the flow of arms stops. Achieving this outcome through a domestic legal process would, in turn, enhance expectations of peaceful change and strengthen the regional security community.

Note that the fact pattern above involves three discrete steps, namely the creation of a regional customary norm; the initiation of a legal process resulting in the successful incorporation and implementation of that norm in one of the members of the security community; and the outcome of the domestic proceedings in one state serving to enhance confidence and intersubjective understandings among the members of the security community. This suggests that domestic laws can significantly influence security community-building dynamics notably through compliance and enforcement,Footnote 217 fostering or facilitating the emergence of mutual trust,Footnote 218 collective identity,Footnote 219 and practical understandingsFootnote 220 at the transnational societal level.

Overall, the connection between legal focal points, TLPs, and peaceful change in PSCs unfolds through a dynamic, iterative process:

1. Defining or establishing legal focal points: legal focal points – such as shared norms, principles, or institutions – are defined, identified, or established to address coordination and distribution problems. These focal points provide a common framework that guides the behaviour and expectations of both public and private actors within the security community.

2. Operationalising through TLPs: legal focal points are embedded in TLPs, which involve interactions between state and non-state actors across borders to create, interpret, and enforce regional law. TLPs promote the diffusion of legal norms across states, shaping both domestic and regional legal frameworks. They also help to institutionalise peaceful mechanisms for resolving disputes, ensuring that legal systems evolve to support stability.

3. Norm internalisation and trust-building: through repeated engagement in TLPs, actors internalise the norms represented by legal focal points. This internalisation fosters trust and predictability, reducing the likelihood of conflicts escalating into large-scale physical violence.

4. Conflict resolution and adaptive mechanisms: the shared legal framework, established by focal points, enables the peaceful resolution of disputes. Over time, these processes adapt to emerging challenges, ensuring the continued relevance and effectiveness of the regional legal system.

5. Strengthening PSCs: as trust and cooperation deepen, the security community becomes more cohesive. Shared legal norms and TLPs contribute to fostering stable expectations of peaceful change at the transnational mass level.

Conclusion

In this article, I made a case for an interdisciplinary turn in the study of PSCs in four steps. First, I argued that the three main theoretical approaches of PSCs – namely transactional, constructivist, and practice theory – all suffer from a similar bias in that they overlook the TLP at the heart of PSCs. Second, taking the level-of-analysis problem seriously, including the norm generation process which remains to be targeted more systematically, I suggested a definition and conceptualisation of regional norms. Empirical evidenceFootnote 221 suggests that PSCs could benefit from a more refined approach about bottom-up norm generation. Third, I discussed the legal internalisation of regional norms, pointing out legal and judicial factors that can facilitate or hinder the process and therefore affect the development of a security community. As we have seen, in addition to helping broaden the ontology of PSCs, understanding the legal internalisation of regional norms can be useful in explaining variations not only within a PSC, but also across PSCs. It can also be helpful in addressing or predicting a wide range of systemic issues, including variations in the level of legalisation of PSCs. Fourth, in addition to explaining how domestic law can influence security community-building dynamics, I argued that regional norms, once internalised into domestic legal systems, can serve as legal focal points (or help construct/identify legal focal points) around which individuals as well as states of a given region coordinate their behaviour and expectations. By helping to solve coordination and distribution problems within states, between states, and beyond states, they contribute to maintaining reasonable and stable expectations of peaceful change at the transnational societal level.

All in all, PSCs’ scholars should not ignore the potential of IL. As the above shows, it is only by combining the two disciplines that one can provide a full picture of the development of PSCs. Taking the IL literature seriously not only suggests a myriad of new and important research questions but also fosters the much-needed interdisciplinary dialogue in the study of PSCs.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Gordon Mace for his unwavering encouragement, insightful ideas, and invaluable conversations, without which this article would never have come to fruition. I also want to thank Alexandre Stylios, Philippe Le Prestre, Kristin Bartenstein, Stefano Guzzini, and the anonymous reviewers and the editors of the Review of International Studies for their helpful comments and critiques of earlier versions.

Funding

I received no funding for this work.