Introduction

Without help, many individuals struggle to make important decisions about their pension in the decumulation phase.Footnote 1 This is the case for both the decreasing number of defined benefit (DB) and the growing number of defined contribution (DC) pension scheme members.

Members of DB schemes must decide the age at which to retire and understand the impact this has on their annual pension. They must also assess whether it is better or not to take a tax-free lump sum in exchange for a lower annual pension. Members must also understand how taking early retirement, or working past their scheme’s normal retirement age, will impact their pension. These choices have associated tax implications specific to an individual’s personal circumstances. In addition, an individual’s retirement income can also be affected by scheme changes. DB schemes may be affected by changes to accrual ratesFootnote 2 or changes from final, to career average, salary as a basis for calculating annual pension entitlements. In addition, as they become less affordable to run, some DB schemes have tried to entice their members into leaving them by buying them out.Footnote 3 These choices are hard to navigate, and most individuals will require help to do so.

For DC scheme members in the U.K., the 2015 Pension Freedoms Act (referred to as Pension Freedoms) introduced further complexity into pension choices by changing the way DC pensions are accessed. The reforms were transformational for both pension savers and pension providers. Previously, most DC pension members, at retirement, purchased an annuity that was expected to provide an income over their remaining life. Other drawdown options existed but were not available to the majority of savers due to their pension scheme rules, leaving annuities (which often were poor value for money) as the only option. The reforms enabled pension savings to be accessed more flexibly to suit individual circumstances.

Thus, the Pension Freedoms shifted the onus onto the individual: the savings were theirs, and they took responsibility for how and when they should be accessed. Savers can choose to convert their pension pot to an annuity, draw the entire pot in cash, draw the pot in smaller chunks using various drawdown arrangements, or leave savings invested. These options have different tax implications and can be combined in different ways. Pension providers were required to develop new products quickly and to offer advice suited to a myriad of different circumstances as savers took advantage of the new flexibility.

In addition, the reforms enabled members of private or funded public sector DB schemes to now opt out of them and put their pension savings into DC schemes. Whether this is beneficial is specific to an individual and to the DB scheme to which they belong. There is no doubt that the Pension Freedoms increased the discretion of pension savers but nonetheless also increased complexity in the market.

Poor pension decisions may have serious consequences for wellbeing in retirement. Since the reforms, examples of poor decisions include running out of money by making unsustainable rates of drawdown; losing substantial pension savings to taxation; withdrawing pension savings only to invest them into cash-based products providing poor returns; and transferring out of DB schemes when it is not beneficial to do so (Financial Conduct Authority, 2018).

A lack of pension literacy puts individuals at risk of making poor choices in the decumulation phase of retirement (The Personal Finance Research Centre, 2017; Association of British Insurers, 2020). This risk is likely to be higher for individuals who do not seek appropriate financial advice. In the U.K., financial advice is a legal regulatory requirement relating to DC pension pots of £30,000 or over with a guaranteed annuity rate attached, and for DB to DC transfers when the pension pot is £30,000 or over. Other than this, there is no legal requirement to seek advice.

A gap exists between those who need and those who seek financial help. This is referred to as the Financial Advice Gap and encompasses both advice and guidance (Financial Conduct Authority, 2016; Touray, Reference Touray2022; Financial Conduct Authority, 2023). The Guidance Guarantee was introduced by the U.K. government to help pension savers. The Money and Pensions Service, an arms-length body sponsored by the Department of Work and Pensions, currently has responsibility for the provision of guidance. However, guidance and advice are different from each other.

Guidance is free and provided by such government agencies as well as by informal sources such as websites, employers, pension providers, and friends and family. However, it is not personalised and only likely to be helpful for individuals with straightforward choices. In addition, guidance provided by employers to their employees, for example, in relation to the best time to retire, may not be in the employees’ best interests or be free from bias (Loretto and White, Reference Loretto and White2006; Vickerstaff, Reference Vickerstaff2006). For those with more complex pension decisions, personalised financial advice provided by independent financial advisors is required, which is not free (Allam et al., Reference Allam, Echalier, James and Luheshi2016; Financial Conduct Authority, 2016; Thurley, Reference Thurley2018).

We have found no academic research about the association between pension literacy and financial advice. However, studies about financial literacy have shown lack of it to be a barrier to seeking advice (Brancati et al., Reference Brancati, Franklin and Beach2017) and why individuals make poor retirement decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell, Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2011a; Lusardi, Reference Lusardi2012; Lusardi et al., Reference Lusardi, Mitchell and Curto2014). There is also a debate over whether financial literacy and financial advice are complementary to (Robb et al., Reference Robb, Babiarz and Woodyard2012; Porto and Xiao, Reference Porto and Xiao2016), or substitutes for (Hung and Yoong, Reference Hung and Yoong2010; Disney et al., Reference Disney, Gathergood and Weber2015), each other. In other words, are those who are more financially literate more or less likely to seek financial advice?

Equally concerning is that individuals are not always aware of the extent of their lack of financial literacy. In other words, ‘they don’t know what they don’t know’. Numerous studies have shown that perceived Footnote 4 is not always indicative of actual financial literacy (Radecki and Jaccard, Reference Radecki and Jaccard1995; Dunning et al., Reference Dunning, Johnson, Ehrlinger and Kruger2003; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Vincent, Hardesty and Bearden2009; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Bruine de Bruin, Yoong and Willis2012; Asaad, Reference Asaad2015; Iwona and Bialowas, Reference Iwona and Bialowas2015; Allgood and Walstad, Reference Allgood and Walstad2016; Kiliyanni and Sivaraman, Reference Kiliyanni and Sivaraman2016; Kramer, Reference Kramer2016). In addition, actual and perceived financial literacy do not always impact financial behaviour in the same way (Allgood and Walstad, Reference Allgood and Walstad2016; Gentile et al., Reference Gentile, Linciano and Soccorso2016; Kramer, Reference Kramer2016; Porto and Xiao, Reference Porto and Xiao2016). In the context of pensions, the capacity to not know what you don’t know is considerable, and individuals may be unaware of the extent of their knowledge or lack of it. If individuals think they know more than they do, then plausibly they may be less inclined to seek advice or guidance.

The aim of this study was to address a gap in the literature by exploring the association between pension literacy and the propensity to seek financial advice about the decumulation phase of retirement planning. Our contribution is unique as while pension literacy and financial literacy are linked, they remain distinct concepts (Eling and Jaenicke, Reference Eling and Jaenicke2023). Pension literacy requires basic financial literacy, but also knowledge about pensions in general and more specifically about one’s own pension scheme. One can be financially literate but not pension literate.

We were interested to discover whether associations between pension literacy and financial advice seeking about the decumulation phase of retirement, support the literature concerning financial literacy and financial advice seeking about other areas of personal finance such as debt, mortgages, taxation, savings, and investments (Porto and Xiao, Reference Porto and Xiao2016; Robb et al., Reference Robb, Babiarz and Woodyard2012). Our findings have the potential to help policymakers address the financial advice gap in the U.K. by understanding how both actual and perceived pension literacy impact financial advice seeking about the decumulation phase of retirement.

Whilst the catalyst for the study emerges from the U.K., the impact of pension literacy on pension decisions and the propensity to seek advice is an important consideration for other countries as individuals now bear more responsibility for their own financial wellbeing in retirement. We focus on both actual and perceived pension literacy. Our research question was How does pension literacy impact the propensity to seek financial advice when making choices about the decumulation phase of retirement?

This article is structured as follows: the next section establishes the academic debates to which the study contributes. The hypotheses, sample characteristics, and the methods of data collection and analysis are then explained. The next two sections describe the results and discuss their significance. The final section summarises the key findings and contributions of the study.

Literature review

The financialisaton of daily life refers to the influence of financial markets and institutions on the everyday activities of individuals such as saving, investing, and retirement planning (Bobek, Reference Bobek2019; Agunsoye and James, Reference Agunsoye and James2024). Risks previously borne collectively by society now fall on individuals to manage (Langley, Reference Langley2007). One such example is the shift from DB to DC pension schemes in the U.K. Individuals are now responsible for ensuring their own retirement security using financial products and markets. To do this effectively requires sufficient financial literacy to make the correct decisions (Langley and Leaver, Reference Langley and Leaver2012).

Many individuals in the U.K. admit to having poor financial and pension knowledge (Money Advice Service, 2020) and require financial advice or guidance to help them make optimal pension choices (Erturk et al., Reference Erturk, Fround, Sukhdev, Leaver and Williams2007; The Personal Finance Research Centre, 2017; Association of British Insurers, 2020). There is empirical evidence to support the association between financial literacy and seeking financial advice about personal finances (Calcagno and Monticone, Reference Calcagno and Monticone2015; Stolper, Reference Stolper2015; Gentile et al., Reference Gentile, Linciano and Soccorso2016; Kramer, Reference Kramer2016; Porto and Xiao, Reference Porto and Xiao2016; Stolper and Walter, Reference Stolper and Walter2017). Individuals with high levels of income and wealth have been found to be more likely to seek financial advice (Bluethgen et al., Reference Bluethgen, Gintschel, Hackethal and Mueller2008; Finke et al., Reference Finke, Huston and Winchester2011; Collins, Reference Collins2012; Allgood and Walstad, Reference Allgood and Walstad2016). The propensity to seek advice increases with age (Bluethgen et al., Reference Bluethgen, Gintschel, Hackethal and Mueller2008; Hackethal et al., Reference Hackethal, Haliassos and Jappelli2012), experience of investing (Hackethal et al., Reference Hackethal, Haliassos and Jappelli2012), and being risk averse (Gerhardt and Hackethal, Reference Gerhardt and Hackethal2009). Men are less likely to seek financial advice than women (Guiso and Jappelli, Reference Guiso and Jappelli2007), and there is conflicting evidence on whether being married increases the likelihood of seeking financial advice (Hung and Yoong, Reference Hung and Yoong2010) or decreases it (Halko et al., Reference Halko, Kaustia and Alanko2012). Higher levels of education have been shown to increase the propensity to seek financial advice (Elmerick et al., Reference Elmerick, Montalto and Fox2002).

Most studies have found a complementary relationship between financial literacy and financial advice, in that financially literate individuals are more likely to seek advice (Collins, Reference Collins2012; Robb et al., Reference Robb, Babiarz and Woodyard2012; Calcagno and Monticone, Reference Calcagno and Monticone2015; Porto and Xiao, Reference Porto and Xiao2016; Seay et al., Reference Seay, Kim and Heckman2016). However, it has been argued that it is not possible, or desirable, to turn people into financial experts. As such, delegating financial decisions to an expert makes sense, suggesting that financial advice is a substitute for financial literacy (Disney et al., Reference Disney, Gathergood and Weber2015; Money Advice Service, 2020). If this holds true, measures should exist to provide those in society who have poor financial literacy with help when they need it.

Studies have shown perceived financial literacy to significantly influence financial advice seeking (Allgood and Walstad, Reference Allgood and Walstad2016; Gentile et al., Reference Gentile, Linciano and Soccorso2016; Porto and Xiao, Reference Porto and Xiao2016). In the Netherlands, Kramer (Reference Kramer2016) found that groups with high levels of self-assessed financial literacy, or confidence, were less likely to seek financial advice. In other words, those who thought they understood finance were less likely to seek out advice.

However, it is often the case that perceived is not indicative of actual financial literacy (Radecki and Jaccard, Reference Radecki and Jaccard1995; Dunning et al., Reference Dunning, Johnson, Ehrlinger and Kruger2003; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Vincent, Hardesty and Bearden2009; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Bruine de Bruin, Yoong and Willis2012; Asaad, Reference Asaad2015; Iwona and Bialowas, Reference Iwona and Bialowas2015; Allgood and Walstad, Reference Allgood and Walstad2016; Kiliyanni and Sivaraman, Reference Kiliyanni and Sivaraman2016; Kramer, Reference Kramer2016). As such, an individual’s perception of their own financial literacy should not be taken as a proxy of how literate they are (Agnew et al., Reference Agnew, Szykman, Utkus and Young2011; Allgood and Walstad, Reference Allgood and Walstad2016). If an individual is overconfident, this could be detrimental to their decision making (Asaad, Reference Asaad2015), resulting in framing errors,Footnote 5 engaging in more costly behaviours (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Bruine de Bruin, Yoong and Willis2012; Asaad, Reference Asaad2015) and underestimating risk (Goel and Thakor, Reference Goel and Thakor2008).

The next section explains the hypotheses development, method of data collection and analysis.

Methods

Hypotheses development

The empirical evidence supports an association between financial advice seeking in relation to personal finances and both actual and perceived financial literacy. We surmised that pension literacy is also associated with seeking financial advice, specifically in relation to pension decumulation decisions. Actual and perceived pension literacy may not impact the propensity to seek advice in the same way. Therefore, the following hypotheses were developed to address the research question:

H1 – There is an association between individuals’ actual pension literacy and seeking pension advice about the decumulation phase of retirement.

H2 – There is an association between individuals’ perceived pension literacy and seeking pension advice about the decumulation phase of retirement.

Development of the research instrument

There is no clear definition of pension literacy in the academic literature. For this study, a working definition of pension literacy was established:

The knowledge and skills in relation to pensions that are sufficient to make effective and optimal choices about retirement.

A survey was developed comprising forty questions (Appendix 1) and incorporating a test of pension knowledge based on twenty multiple choice questions split over three sections: basic financial literacy; basic pension literacy; and knowledge of the U.K. Pension Freedoms. Typically, tests of pension knowledge have comprised fewer questions and we argue that this test was more comprehensive than those used in previous studies. Some of the questions were adapted for the U.K. from the globally used and well-cited Lusardi and Mitchell study (Lusardi and Mitchell, Reference Lusardi and Mitchell2011b). The majority were, however, developed with a panel of twenty experts from the financial services industry to ensure the questions were valid, accurate, and of the right difficulty for a layperson.

Three questions measured perceived pension knowledge and financial confidence using a 5-point Likert scale. Likert scales have been used in other studies to measure similar concepts (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Bruine de Bruin, Yoong and Willis2012; Lusardi et al., Reference Lusardi, Mitchell and Curto2014; Asaad, Reference Asaad2015; Allgood and Walstad, Reference Allgood and Walstad2016; Kramer, Reference Kramer2016; Porto and Xiao, Reference Porto and Xiao2016). Participants were asked: ‘How would you rate your own level of knowledge about pensions?’ This question was included twice, once before completing the test of pension knowledge (Q5) and once after doing so, having just received their quiz results (Q39). We surmised that participants’ perceptions of their pension knowledge may change having completed the test. To assess participants’ level of financial confidence participants were asked: ‘How confident are you that you will be financially secure in retirement?’ (Q4) and ‘How confident do you feel about making choices on how to draw your pension? (Q6).

Our outcome variable of interest was whether participants intended to pay for independent financial advice about drawing their pension. Participants were asked to respond yes, no, or don’t know (Q7). To assess the personal characteristics and background of participants, other demographic and fact-finding questions were included. Before completing the twenty quiz questions, participants were informed they would receive their score and some feedback at the end of the survey. This was to incentivise completion of the full survey. In addition to this, regardless of score, all participants were directed to the Pension Wise website for more information about pensions.Footnote 6

Data collection and sample

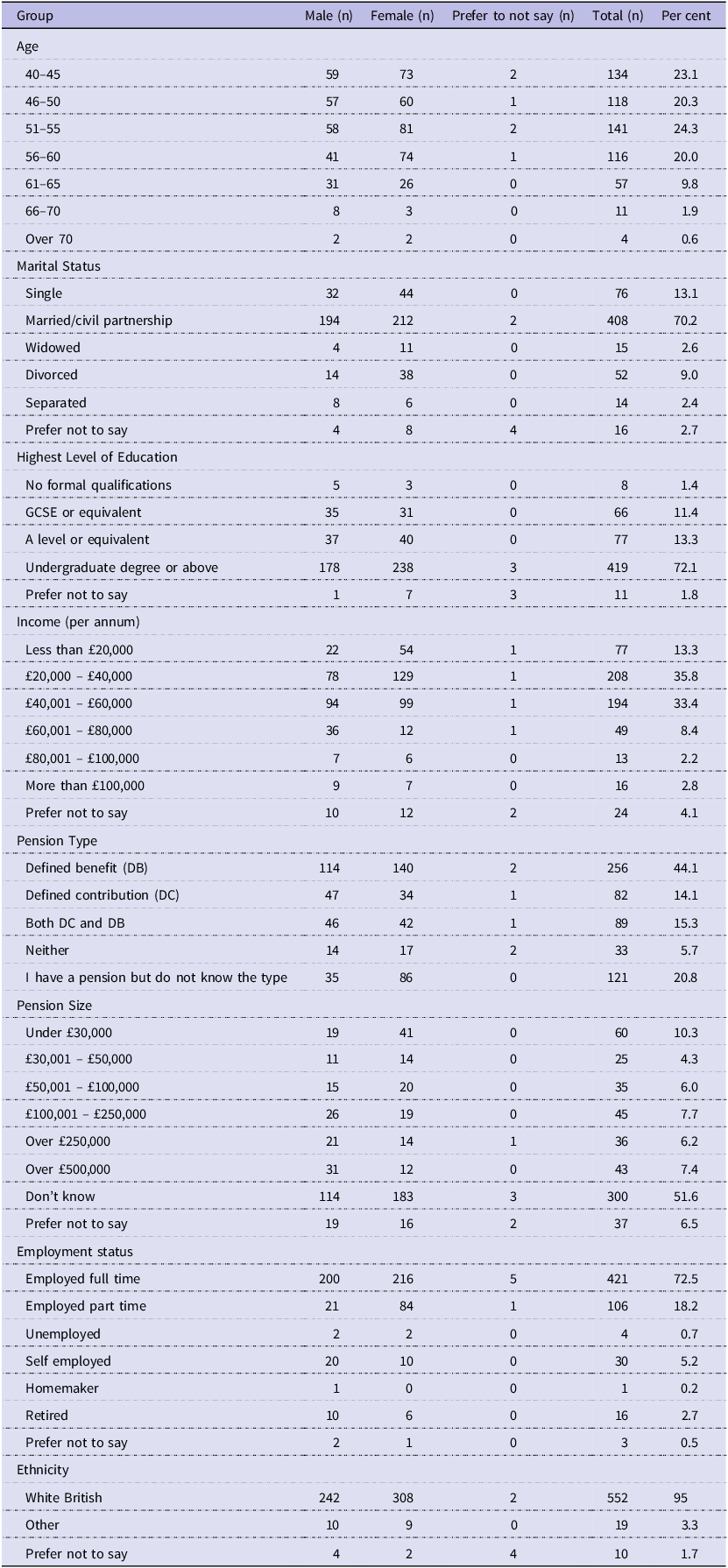

The survey was distributed electronically via social media and email over a six-month period. Six-hundred forty-five responses from participants living in the North East region of England were collected, having self-selected to participate.Footnote 7 Responses from participants aged under forty were discarded as being too young to yet be thinkning about decumulation choices. Therefore, the final sample comprised 581 participants. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample. Of those who provided a response, 45 per cent were male, 55 per cent female; 70.2 per cent were married; 82.5 per cent had an income level of less than £60,000 per annum; 44.1 per cent had only a DB pension, 14.1 per cent only a DC pension, 15.3 per cent had both types, 20.8 per cent did not know the type of pension they had, and 5.7 per cent had no pension.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants

Source: Author.

Individuals educated to undergraduate degree level or higher were overrepresented in the study, as 72.1 per cent is very much higher than in the North East region and in England. Because general education and pension literacy are distinct concepts, we were interested to see if this bias would influence the results obtained.

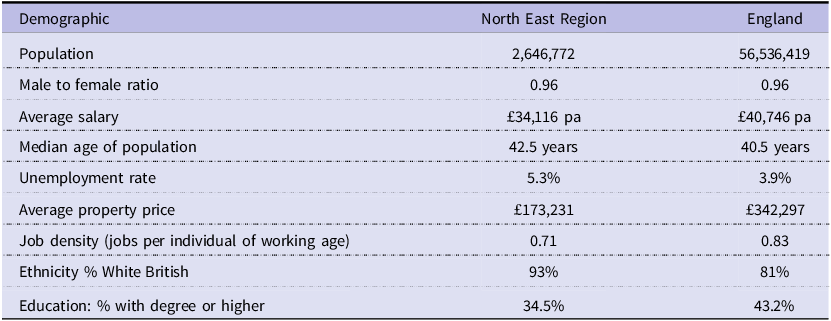

Table 2 compares the demographics of the North East region to that of England. The population of the North East is less wealthy, has a lower average salary, a higher rate of unemployment, and lower level of general education. In addition, the North East has a 93 per cent White British population compared with 81 per cent in England (ONS, 2021). Therefore, we cannot claim our sample to be representative of the region or of England. These sample biases do raise issues of external validity and must be acknowledged.

Table 2. Demographics of the North East Region compared with England (ONS Census data 2021)

Methods of data analysis – establishing variables

Actual pension literacy

Based on the approach of Lusardi et al. (Reference Lusardi, Mitchell and Curto2014), weightings were applied to each of the questions to account for difficulty. A correct answer was given more credit if most of the sample answered incorrectly, and incorrect answers were penalised more heavily if most of the sample answered correctly. Weighting according to how difficult respondents found the questions provided a more informative measure than using an absolute score. A total weighted score was determined for each participant by totalling individual question scores, and this provided a measure of actual pension literacy.

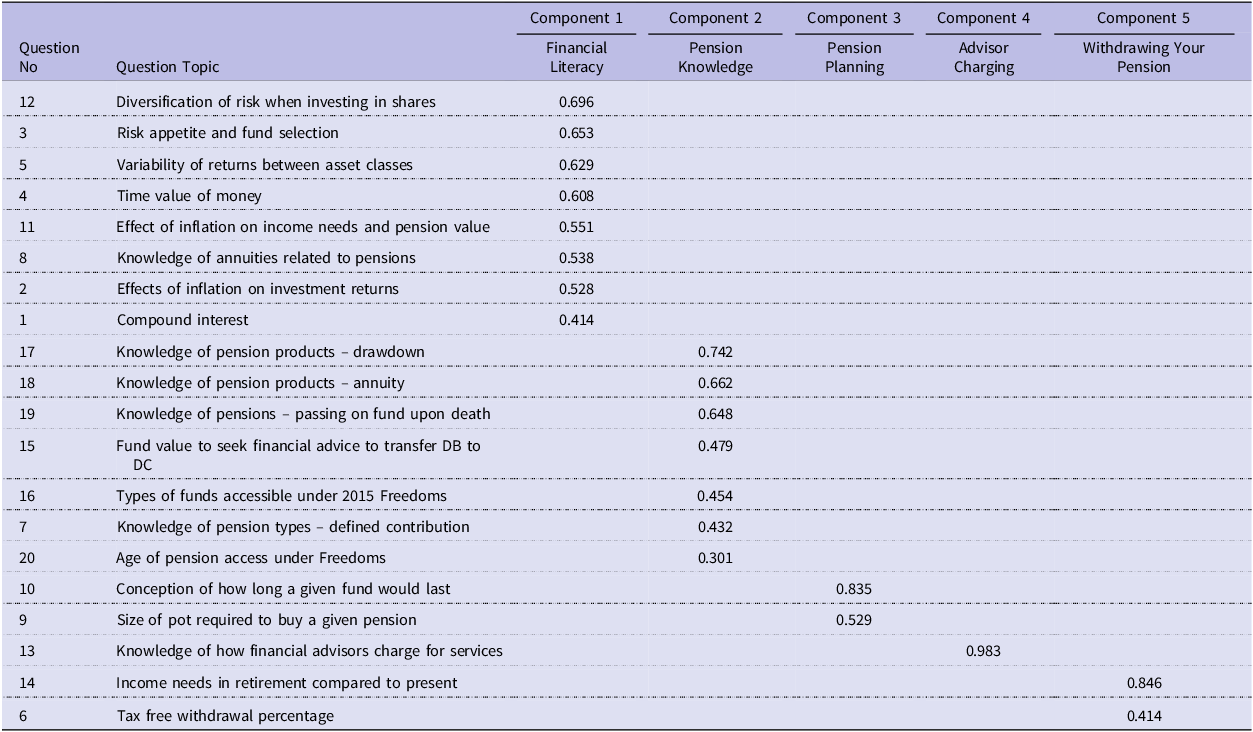

Following previous studies on financial literacy (Lusardi et al., Reference Lusardi, Mitchell and Curto2014; Gentile et al., Reference Gentile, Linciano and Soccorso2016), Principal Components Analysis was applied to the weighted question scores. Principal Components Analysis reduces a set of variables to smaller dimensions (or components). It was used here to explore if the concept of pension literacy could be reduced to smaller components.

The analysis was performed using an oblique rotation method, based on covariance. By applying Kaiser’s criterion (Kaiser, Reference Kaiser1974), five meaningful components were extracted, explaining 47.2 per cent of variance. Upon examination, each component was observed to represent different aspects of pension literacy and so there was no need to reduce the number of factors. Table 3 shows, by question topic, how the factor loadings were distributed to the components, which were named: Basic financial literacy; Basic pension knowledge; Pension planning; Advisor charging; and Withdrawing your pension. The factor scores were saved as continuous variables serving as proxies for each of the five elements of pension literacy, representing alternative measures of actual pension literacy.

Table 3. Principal components analysis – factor loadings

Source: SPSS.

Perceived pension literacy

The three questions on perceived knowledge and financial confidence were combined into one composite variable (by adding Likert scores together) representing perceived pension literacy. Perceived knowledge and confidence have been shown to be very closely related in the literature, and other studies have used a similar approach (Robb et al., Reference Robb, Babiarz and Woodyard2012; Asaad, Reference Asaad2015; Allgood and Walstad, Reference Allgood and Walstad2016). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.841, which is considered good (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1951).

Outcome variable

The study focused on paid-for financial advice as most DB and DC pension scheme members will need financial advice if they do not have very straightforward choices. An outcome variable was defined based on the survey question (Q7) Do you intend to seek professional independent financial advice prior to making your pension choices? A binary outcome was established where participants who did intend to seek advice were coded 1 and those who did not 0. Those who did not know whether they intended to seek advice, were excluded as missing values for this part of the analysis (n=213).Footnote 8

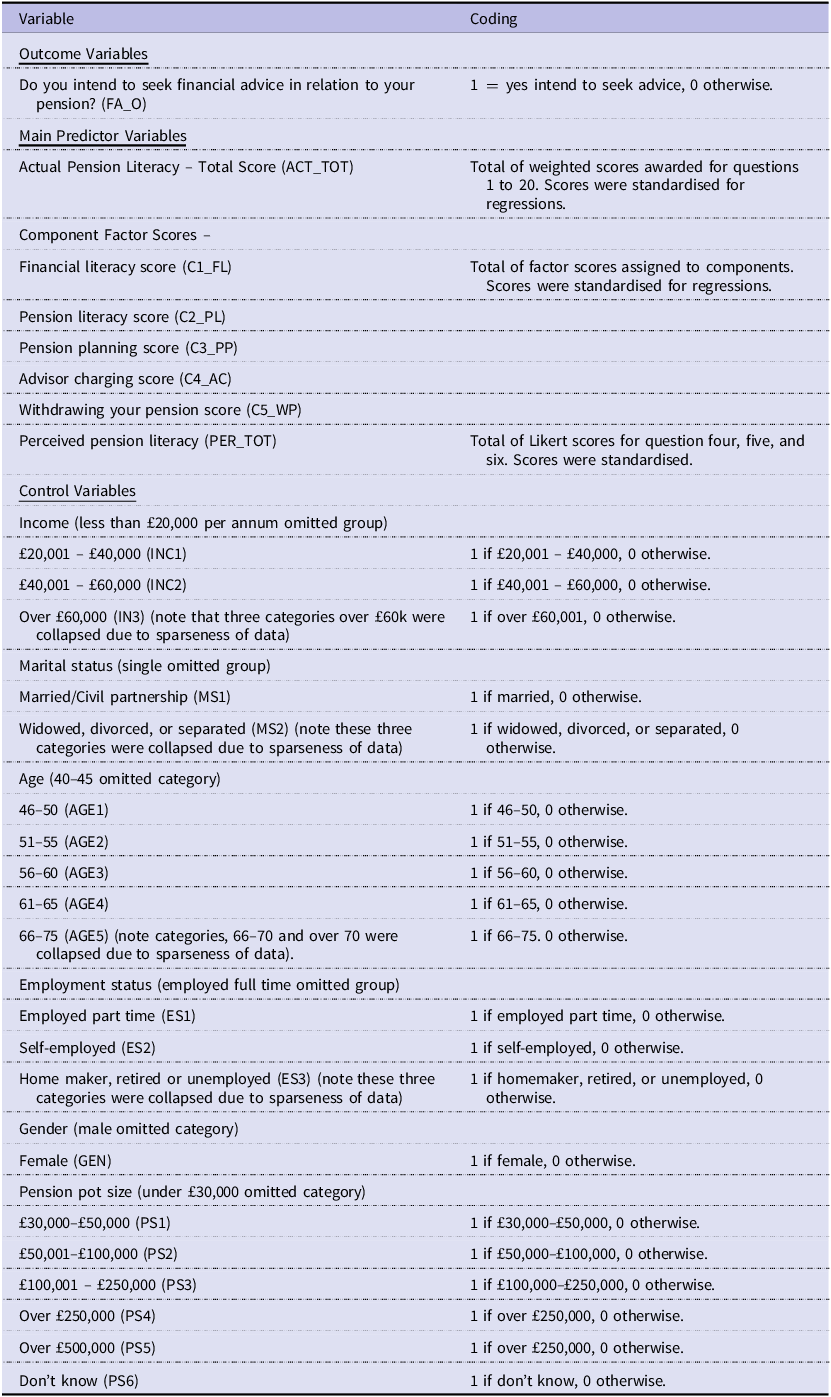

Control variables

Six control variables were included. These were income, age, gender, employment status, marital status, and pension pot size. These variables correlate with the dependent variables, and their relationship to financial advice seeking has been established in the literature. The full list of variables can be seen in Table 4.

Table 4. Variables in the logistic regressions

Source: Author.

Data analysis – logistic regressions

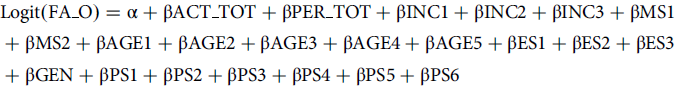

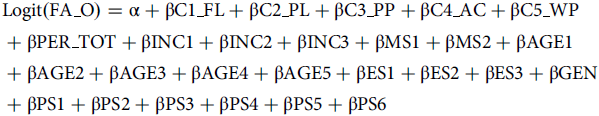

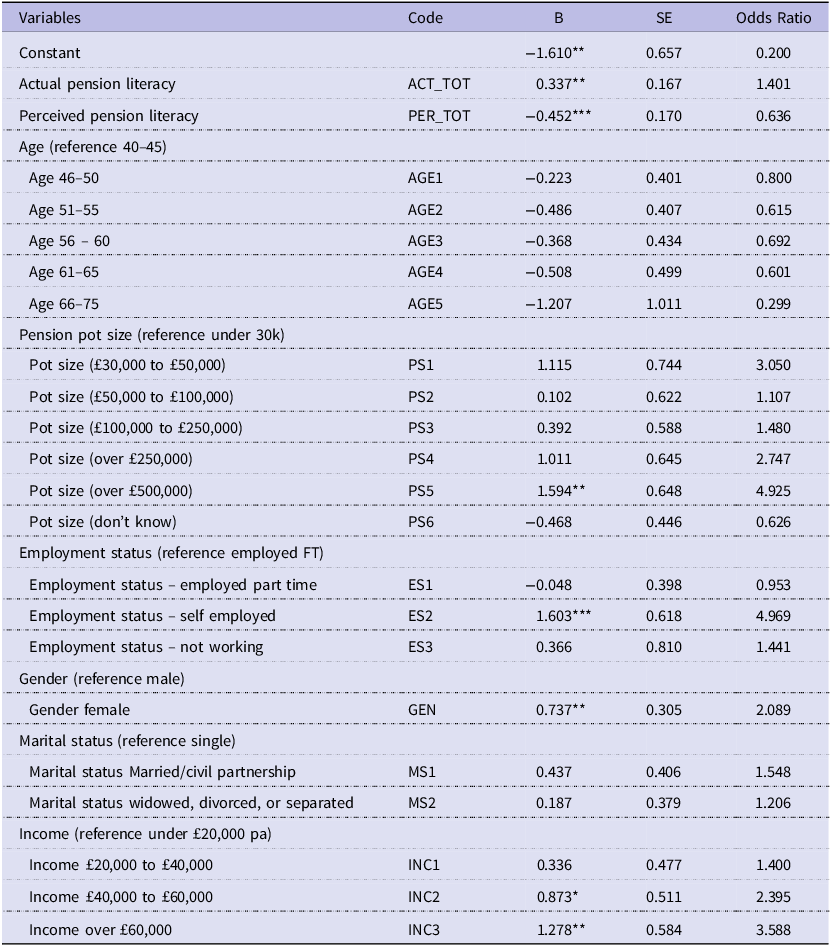

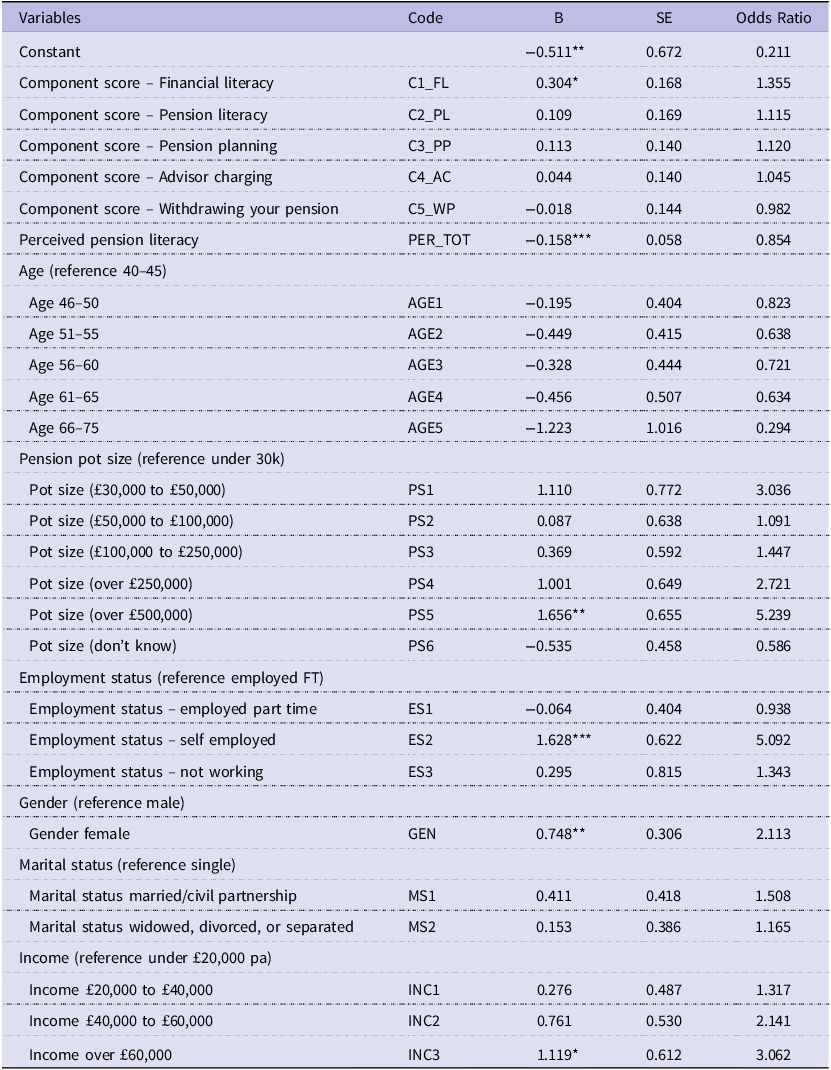

Some simple statistical analysis was performed on the survey data based on all 581 participants. Binary logistic regression was then applied to test the hypotheses based on the outcome variable. As well as participants answering ‘don’t know’ (n=213), we excluded any participants who had refused to answer any demographic questions (n=51) providing a final sample of 317 participants for the regressions. Two regressions were conducted:

The first used actual and perceived total score and the control variables.

The second replaced actual pension literacy with the five-component scores from the principal components analysis, in addition to the perceived score.

All continuous measures were converted to Z scores for ease of output interpretation. In the next section, the results of the descriptive statistical analysis are discussed followed by the logistic regressions.

Results

Descriptive statistics

When asked Do you intend to pay for independent professional financial advice prior to making your pension choices?, 23 per cent of participants intended to seek financial advice, 40 per cent did not, and 37 per cent did not yet know. Half of the latter group were aged forty to fifty, possibly too far from retirement to decide. Policymakers still have time to persuade this group about the benefits of seeking advice.

Chi-squared tests revealed a significant difference in the intention to seek financial advice based on pension type (x 2 (8, 581) = 34.49, p < 0.01), indicating a relationship between seeking advice and pension type. Participants with only DC schemes were more likely to seek financial advice than those with DC and DB schemes or those with only DB schemes. However, Cramer’s V, reported as 0.172, only showed a small effect size (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988). The small effect size could be attributed to the similar level of complexity of choices faced by both DB and DC pension scheme members at retirement. Sixty-three per cent of participants who were members of only DC schemes; 72 per cent of participants who were members of both DB and DC schemes, and 88 per cent of participants who did not know the type of pension of which they were a member (which in itself shows a lack of pension literacy), either did not intend to seek advice, or did not know whether they would seek advice.

After having completed the test, 39.2 per cent of participants indicated their decision on whether to seek advice had changed. Of the participants who had originally indicated they did not intend to seek advice, 25.6 per cent changed their mind after completing the test (47.9 per cent said it would have no impact, and 25.6 per cent did not know). This suggests that, for most of these participants, not seeking advice may be due to factors other than their pension knowledge. However, of the participants who originally stated they did not know whether they would seek advice (37 per cent of the sample), nearly half (47.4 per cent) said that taking the test changed their minds. This suggests that perceived pension literacy had an impact on their decision. This emphasises the importance of perceived pension literacy and of self-assessment to better gauge one’s actual level of pension knowledge.

Participants who intended to seek advice (n = 134) had better pension literacy (M = 1.37, SD = 3.90) than participants who did not (n = 234, M = 0.21, SD = 4.32). This held true for all five components determined by the principal component analysis. However, results were reversed for perceived pension literacy. Participants who intended to seek advice scored lower (n = 134, M = 8.92, SD = 2.89) than participants who did not intend to seek advice (n = 234, M = 9.16, SD = 3.06). Participants’ mean scores based on the question How would you rate your own level of knowledge about pensions? fell after having taken the test. To determine if this was significant, a paired-samples t-test was conducted comparing participants’ perceived knowledge before and after taking the test. There was a significant difference in the scores before the test (M=2.57, SD=1.07) and after (M=2.36, SD, 1.01). This confirmed that having attempted the questions, participants rated their knowledge to be significantly lower than before doing so.

In summary, less than a quarter of participants intended to seek advice about drawing their pension. Participants who intended to seek advice had better actual pension literacy than those who did not. However, participants who did not intend to seek advice had higher perceived pension literacy. This suggests that those who think they know more about pensions are less inclined to seek advice. However, having taken the test, participants rated their own pension knowledge to be lower than before having done so, enabling them to better assess their own pension knowledge, and for some, this changed their mind about seeking advice.

Logistic regressions

Tables 5 and 6 show the results of the logistic regressions for the outcome variable Do you intend to pay for independent professional financial advice prior to making your pension choices? The odds ratios explain how a movement of one standard deviation above or below the mean value of the predictor variable impacts the likelihood of seeking advice.

Table 5. Logistic regression: weighted actual and perceived scores and outcome variable: ‘Do you intend to seek financial advice?’ (FA_O)

n = 317.

*** significant at the 1% level.

** significant at the 5% level.

* significant at the 10% level.

Table 6. Logistic regression: component factor scores and outcome variable: ‘Do you intend to seek financial advice?’ (FA_O)

n = 317.

*** significant at the 1% level.

** significant at the 5% level.

* significant at the 10% level.

Both actual (p < 0.05) and perceived pension literacy (p < 0.01) were significant predictors (Table 5). An increase of one standard deviation in the actual pension literacy score increased the intention of seeking advice by 1.4 times. However, an increase of one standard deviation in perceived literacy score decreased the likelihood of seeking advice by approximately 0.6 times.

Only the component of basic financial literacy was significant (p < 0.10) (Table 6). An increase of one standard deviation in financial literacy score, coincidentally, also increased the intention to seek advice by around 1.4 times.

Gender, employment status, income, and pension pot size were significant predictors of the intention to seek financial advice (p < 0.05) (Table 5). Females were twice as likely to seek financial advice. Self-employed participants were nearly five times as likely to seek advice than participants who were employed full time. Compared to participants with income less than £20,000 per annum, participants with incomes between £20,000 and £40,000 were 1.4 times as likely to seek advice, participants with incomes £40,000 to £60,000 were 2.4 times as likely, and participants with incomes over £60,000 were 3.6 times as likely. Participants with pots over £500,000 were nearly five times more likely to seek advice than participants with pots under £30,000, and the associated odds ratios increased as pension pot size increased. Participants with pots between £30,000 and £50,000 were three times as likely to seek advice as participants with pots under £30,000. Participants who did not know the size of their pension pot were 0.6 times as likely to seek advice as participants with pots under £30,000.

Discussion

The unique contribution of this study is to provide empirical evidence concerning the relationship between pension literacy and financial advice seeking in relation to pension decumulation decisions to assist practitioners and regulators. We address a gap in the academic literature by examining both pension literacy and the decumulation phase of retirement.

The motivation for the study originated from the U.K. However, pension literacy, pension decumulation decisions, and the uptake of financial advice are important areas for consideration beyond the U.K. This is especially the case as both DB and DC pension scheme members have more responsibility for their wellbeing in retirement than previously. This is likely to increasingly be the case as more DB pensions schemes are replaced with DC schemes.

Most individuals will require financial advice or guidance to help them make the most effective choices as they draw their pension savings (Financial Conduct Authority, 2016). Individuals with very small DC pension pots or members of unfunded DB pension schemes (not permitted to opt into a DC scheme) may find guidance alone will be sufficient.

However, as discussed, most DB pension scheme members have significant complexities to navigate when planning their retirement. For DC pension scheme members, choices are also complicated, made more so in the U.K., by the Pension Freedoms. Therefore, for both DB and DC pension scheme members, independent financial advice is likely to be required (Financial Conduct Authority, 2016). Despite this, our study showed that only 23 per cent of participants intended to seek financial advice, 40 per cent did not intend to seek advice, and 37 per cent did not yet know whether they would do so.

The results of the logistic regressions and the descriptive statistics support most financial literacy studies, in that they show a complementary relationship (Collins, Reference Collins2012; Robb et al., Reference Robb, Babiarz and Woodyard2012; Calcagno and Monticone, Reference Calcagno and Monticone2015; Gentile et al., Reference Gentile, Linciano and Soccorso2016; Seay et al., Reference Seay, Kim and Heckman2016). In this study, an increase of one standard deviation in the actual pension literacy score increased the intention of seeking advice by 1.4 times. In other words, pension literacy is required in order to seek advice, but individuals who most need advice, those who lack pension literacy, are less likely to seek it.

Unique to this study, pension literacy was deconstructed to five components based on principal components analysis. Only the component ‘financial literacy’ was statistically significant. An increase of one standard deviation in financial literacy score increased the intention to seek advice, coincidentally also by around 1.4 times. This suggests that one must be financially literate enough to weigh up the value of advice against the potential financial consequences of not doing so. Financial literacy appears, therefore, to be more important than pension-specific knowledge in seeking advice.

The findings enabled hypothesis one to be accepted:

H1 – There is an association between individuals’ actual pension literacy and seeking pension advice about the decumulation phase of retirement.

In this study, perceived pension literacy was a significant predictor of the intention to seek advice at the one per cent level. An increase of one standard deviation in perceived literacy score, decreased the likelihood of seeking advice by approximately 0.6 times. This indicates that perceived pension literacy is a substitute for financial advice. The study supports previous suggestions that individuals who perceive their financial knowledge to be high, may not perceive the need to seek financial advice because they believe they possess sufficient pension knowledge to make decisions without it (Gentile et al., Reference Gentile, Linciano and Soccorso2016; Kramer, Reference Kramer2016; Porto and Xiao, Reference Porto and Xiao2016).

The findings enabled hypothesis two to be accepted:

H2 – There is an association between individuals’ perceived pension literacy and seeking pension advice about the decumulation phase of retirement.

Various demographic factors were associated with seeking advice. This study found females are twice as likely to seek advice as males, supporting other studies (Guiso and Jappelli, Reference Guiso and Jappelli2007; Finke et al., Reference Finke, Huston and Winchester2011). For women, good pension decision making is especially important as many may be at a financial disadvantage in terms of pension income (Ginn, Reference Ginn2004; Ginn and MacIntyre, Reference Ginn and MacIntyre2012). Age was not a significant predictor of advice seeking in this study (possibly as the age range was limited to forty and over), whereas other studies have found age to be significant in seeking advice about other areas of personal finance, with the propensity to seek advice increasing with age (Bluethgen et al., Reference Bluethgen, Gintschel, Hackethal and Mueller2008; Hackethal et al., Reference Hackethal, Haliassos and Jappelli2012). Research has found that as personal incomes increase, so does the propensity to seek advice (Bluethgen et al., Reference Bluethgen, Gintschel, Hackethal and Mueller2008; Collins, Reference Collins2012; Jappelli and Padula, Reference Jappelli and Padula2013; Brancati et al., Reference Brancati, Franklin and Beach2017). Participants with incomes over £60,000 were 3.6 times as likely to seek advice than those with incomes under £20,000. Individuals with higher incomes can better afford financial advice, and cost has been identified as a factor in the decision to seek advice (Van Dalen et al., Reference Van Dalen, Henkens and Hershey2017).

Pension pot size was significant in the intention to seek advice, supporting other studies (Bluethgen et al., Reference Bluethgen, Gintschel, Hackethal and Mueller2008; Jappelli and Padula, Reference Jappelli and Padula2013; Brancati et al., Reference Brancati, Franklin and Beach2017). Participants with pots over £500,000 were nearly five times more likely to seek advice than participants with pots under £30,000, and the associated odds ratios increased as pension pot size increased. In the U.K., financial advice is a legal requirement for DB to DC transfers when the pension pot exceeds £30,000. Consistent with Brancati et al. (Reference Brancati, Franklin and Beach2017), this study found that self-employed participants were nearly five times more likely to seek advice than participants who were employed full time. This is perhaps not surprising as this group would not be exposed to any guidance facilitated by employers and is also encouraging.

In light of these findings, it is especially important for males and individuals who have lower levels of income and wealth to be incentivised to access appropriate forms of help to make pension decisions as these groups are less likely to seek advice. It is also important to address cases where individuals’ perceived pension knowledge may be higher than it actually is. High perceived pension knowledge may also be a barrier to seeking advice.

Limitations of the study

This study is based on a reasonably small sample size and focused on one region of England, the North East, which is not demographically representative of the U.K. However, despite the sample limitations described earlier in the paper, most of the descriptive and inferential findings do support those of other academics in previous studies in the field of financial literacy and seeking advice about personal finance issues. This suggests they may be reflective of other populations outside of the North East region. This would need to be determined empirically with a larger, more representative sample.

Conclusion

Individuals must make complex choices about how and when to draw their personal pensions as they near retirement. Many individuals will need personalised financial advice to make pension decisions about the decumulation phase of retirement, as free guidance will not be tailored to their individual circumstances (Financial Conduct Authority, 2015). However, in the U.K., a gap still exists between those who need advice and those who seek it (Financial Conduct Authority, 2023). This study has sought to understand how pension literacy may contribute to the decision to seek financial advice.

Many individuals admit to having poor knowledge of pensions. However, due to the complexity of the subject and lack of opportunity to do so, to make an accurate assessment of one’s knowledge is challenging, and it is possible many individuals ‘don’t know what they don’t know’.

In this study, actual and perceived pension literacy did not impact financial advice seeking in the same way. A discrepancy between the two could put individuals at risk of making poor financial decisions that may jeopardise their financial wellbeing in retirement. If individuals believe they know more than they do, they may fail to access the financial help they need.

The research question addressed was How does pension literacy impact the propensity to seek financial advice when making choices about the decumulation phase of retirement?

Four main findings emerged from this study, which we believe will aid regulators and practitioners:

-

1. The higher participants’ actual pension literacy, the more likely their intention to seek financial advice.

-

2. The higher participants’ perceived pension literacy, the less likely their intention to seek advice. This may be because individuals think they know enough to make decisions without advice. Self-assessment of pension knowledge may go some way to addressing over-confidence, allowing individuals to become more aware of what they do and do not know about pensions and in turn possibly making it more likely they will seek advice.

-

3. Many participants have yet to make up their minds about seeking advice, which suggests there is scope to persuade this group of the benefits to be gained from doing so. Some participants, particularly those who stated they were undecided, having been made aware of their own level of pension literacy, changed their minds about seeking advice. This suggests that providing opportunities for individuals to assess their own pension knowledge could improve the uptake of financial advice. For others, though, their decision was not changed by taking the test. This suggests that, for these participants, factors other than pension literacy are important. This is an interesting area for further study.

-

4. The results suggest that basic financial literacy may be more important than specific pension knowledge in the intention to seek advice. This may be because an understanding of core financial concepts enables individuals to appreciate the value to be gained from doing so. We argue that financial literacy is an important element of pension literacy and a pre-requisite to an understanding of pensions. Financial literacy alone, however, may not be important enough to make good pension choices without advice. This is an interesting area for further study.

In light of the foregoing, further education is needed to increase knowledge about pensions for everyone, but especially for those less likely to seek help. In school, being taught basic principles of financial literacy, for example, compound interest, will help young people understand the benefits of contributing to a pension from an early age. As highlighted in a recent report by the House of Lords (2024), schools should be encouraged to engage with the resources that are available to them (see, for example, The Money and Pensions Service (2024) and the Personal Finance Education Group (2024)). In addition to formal education, this research has also demonstrated the power of social media as a way of increasing the public’s curiosity about pensions, encouraging their engagement with self-assessment tools.

To conclude, most consumers now have more choice about how and when to draw their pensions. This is the case for both DB and DC pension scheme members. Individuals who need help in the form of financial advice are still not seeking it for various reasons and in the U.K., a financial advice gap still exists. This study has shown that improving the actual pension literacy, specifically basic financial literacy, of the public may be an important way to narrow this gap, and that lack of pension and financial literacy may be an important barrier to seeking financial advice. It also found that those with high perceived pension literacy are less likely to seek advice. We argue that, if the public are aware of their own pension knowledge (or lack of it), this will emphasise the need for help, stimulate education attempts and prevent overconfidence.

Pension literacy will be an even greater priority for future generations as more DB schemes are closed and replaced by DC schemes. These individuals will face complex decisions for which pension literacy, as well as access to appropriate forms of advice, will be increasingly important.

Appendix 1

Pension Literacy Survey (distributed using Survey Monkey)

Before starting the quiz section, please answer the following questions. The answers you give are completely anonymous, confidential, and will only be used for the purpose of this research project. If you are happy to proceed on this basis, please click OK to continue.

-

Q1 What type of private pension(s) do you have? Please ignore state pension.

-

a) Defined benefit (pension based on final or average salary)

-

b) Defined contribution/money purchase (pension based on contribution levels)

-

c) Both defined benefit and defined contribution

-

d) Neither

-

e) I have a pension, but I don’t know which type it is

-

-

Q2 Which of the following would you be likely to consult (or have already done so) prior to deciding on how to take your pension? (Indicate all that apply; then click OK to continue.)

-

a) Pension Wise

-

b) Independent Financial Advisor

-

c) Pension Provider

-

d) Internet Sources

-

e) Government Publications

-

f) Friends and Family

-

g) Employer

-

h) None of the above or I do not know

-

-

Q3 Have you ever tried to work out how much income you will need in retirement?

-

a) Yes

-

b) No

-

-

Q4 On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is not confident at all and 5 is very confident, how confident are you that you will be financially secure in your retirement?

-

a) 1

-

b) 2

-

c) 3

-

d) 4

-

e) 5

-

-

Q5 On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is very poor and 5 is excellent, indicate how you would rate your own level of knowledge about pensions.

-

a) 1

-

b) 2

-

c) 3

-

d) 4

-

e) 5

-

-

Q6 On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is not confident at all and 5 is very confident, how confident do you feel about making choices on how to take your pension?

-

a) 1

-

b) 2

-

c) 3

-

d) 4

-

e) 5

-

-

Q7 Do you intend to pay for independent professional financial advice prior to making your pension choices?

-

a) Yes

-

b) No

-

c) Don’t know

Thank you – Now let’s start the quiz! You will receive your score and feedback at the end. Quiz section one contains five questions and tests your basic financial literacy. Please answer all questions. Click OK to continue.

-

-

Q8 You invest £100 in a savings account with compound interest of 2 per cent per year. After 5 years, how much would you have in the account if you did not make any withdrawals?

-

a) Exactly £110

-

b) More than £110 (Correct)

-

c) Less than £110

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q9 You have savings in an account that pays an annual interest rate of 1.5 %. If annual inflation were 2 per cent after 1 year, which of the following would apply?

-

a) I would be able to buy more with my savings than 1 year ago

-

b) I would be able to buy less with my savings than 1 year ago (correct)

-

c) I would be able to buy the same as 1 year ago

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q10 Assume you are able to purchase some shares. Which of the following has the highest level of risk?

-

a) Investment in shares of one company (correct)

-

b) Investment in shares of an investment fund

-

c) Both have equal risk

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q11 Assume a friend inherits £10,000 today and his sibling inherits £10,000 3 years from now. Who is richer because of the inheritance?

-

a) Your friend (correct)

-

b) His sibling

-

c) Both are equally as rich

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q12 Which type of investment normally shows the greatest variability in returns over time?

-

a) Savings accounts

-

b) Corporate bonds

-

c) Shares (correct)

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

Thank you. Quiz section two contains eight questions and tests your understanding of basic pension concepts. Please answer all questions. Click OK to continue.

-

-

Q13 As a working figure, how much income do pension providers advise their clients will be needed in retirement?

-

a) One-half of working income

-

b) One-third of working income

-

c) Two-thirds of working income (correct)

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q14 What type of pension is described by the following: Members (and sometimes their employers, but not always) make contributions invested in asset groups according to the risk preference of the individual. Upon retirement, the scheme member has accumulated a fund that can be used either to buy an annuity or to draw down in some other way according to preference.

-

a) Defined benefit contribution pension scheme

-

b) State pension

-

c) Defined contribution pension scheme (correct)

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q15 Which type of pension is most likely to ensure you have a guaranteed income for life?

-

a) Defined benefit pension scheme (correct)

-

b) Defined contribution pension scheme

-

c) Both are equally as likely

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q16 If you want to have an income of around £25,000 per year, typically what size of pension pot do you require?

-

a) £62,500

-

b) £625,000 (correct)

-

c) £950,000

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q17 You have a pension fund of £100,000. How many years do you think it would last if you spent £10,000 per annum and you had investment returns on the remaining balance of 5 per cent per annum?

-

a) 10 years

-

b) 12 years (correct)

-

c) 15 years

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q18 What is the effect of high inflation on both your pension fund and on your income needs in retirement?

-

a) There will be no effect on either

-

b) Increase pension value and decrease income need

-

c) Decrease pension value and increase income need (correct)

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q19 If you are risk averse (you tend to avoid risk), which of the following investment funds are more likely to suit your risk preference?

-

a) 50% bonds, 10% cash 20% property 20% shares (correct)

-

b) 40% bonds, 10% cash, 20% property, 30% shares

-

c) 30% bonds, 10% cash, 20% property, 40% shares

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q20 You choose to go to a financial advisor for advice on pensions. On what basis can you expect your bill to be determined?

-

a) Fee based (correct)

-

b) Commission based

-

c) Both of these

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

Thank you. In 2015, the government introduced major pension reforms called Pension Freedoms. This final quiz section contains seven questions and tests your understanding of their impact. Please answer all questions. Click OK to continue.

-

-

Q21 Under the 2015 Pension Freedoms, at what age can individuals currently draw upon their pension funds?

-

a) 50

-

b) 55 (correct)

-

c) 60

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q22 Which types of pensions are accessible under the 2015 Pension Freedoms?

-

a) All pensions

-

b) Only defined contribution pensions (correct)

-

c) Only defined benefit pensions

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q23 How much of your qualifying pension fund can you normally withdraw tax-free?

-

a) 25% (correct)

-

b) 50%

-

c) All of it

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q24 Which pension product generally allows you to leave funds invested and withdraw money, as you require it?

-

a) An annuity product

-

b) A drawdown product (correct)

-

c) Both of these

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q25 Which pension product is most likely to provide a guaranteed income for life?

-

a) An annuity product (correct)

-

b) A drawdown product

-

c) Both of these

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q26 Which pension product allows you to pass on any unused funds to your family members when you die?

-

a) An Annuity product

-

b) A drawdown product (correct)

-

c) Both of these

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

-

-

Q27 Individuals with defined benefit schemes can access the total value of their pension fund at 55 only if they transfer it to a defined contribution scheme. What is the pension fund value at which they would be required to seek financial advice prior to the transfer?

-

a) £10,000

-

b) £30,000 (correct)

-

c) £50,000

-

d) Don’t know

-

e) Refuse to answer

You’re nearly finished – while your quiz score is being calculated, please answer a few final questions about yourself.

-

-

Q28 What is your age?

-

a) Under 40

-

b) 40 – 50

-

c) 51 – 60

-

d) 61 – 70

-

e) Over 70

-

f) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q29 What is your highest level of educational qualification?

-

a) No formal qualifications

-

b) GCSE or equivalent

-

c) A level or equivalent

-

d) Undergraduate degree

-

e) Master’s degree

-

f) PhD/doctorate

-

g) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q30 What is your current level of personal income (from all sources)?

-

a) Less than £20,000 per annum

-

b) £20,000 to £40,000

-

c) £40,000 to £60,000

-

d) £60, 000 to £80,000

-

e) £80,000 to £100,000

-

f) More than £100,000

-

g) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q31 In which region of the UK do you live? *

-

a) North East

-

b) North West

-

c) Yorkshire and Humber

-

d) East Midlands

-

e) West Midlands

-

f) East of England

-

g) Greater London

-

h) South East

-

i) South West

-

j) Wales

-

k) Scotland

-

l) Northern Ireland

-

m) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q32 What best describes your main employment status?

-

a) Employed full time

-

b) Employed part time

-

c) Unemployed seeking work

-

d) Unemployed not seeking work

-

e) Self-employed

-

f) Unable to work

-

g) Homemaker

-

h) Retired

-

i) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q33 In which sector have you spent the majority of your working life to date? (Please answer even if you are now retired).

-

a) Public sector

-

b) Private sector

-

c) Not for profit sector

-

d) Another sector not mentioned

-

e) None of these

-

f) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q34 In which industry have you spent the majority of your working life to date? *

-

a) Agriculture

-

b) Mining and extractives

-

c) Manufacturing

-

d) Construction

-

e) Retail and Wholesale

-

f) Transportation and storage

-

g) Accommodation and Food

-

h) Information and Communication

-

i) Finance and Insurance

-

j) Real Estate

-

k) Professional and Support

-

l) Government

-

m) Health

-

n) Education and Defence

-

o) Other services

-

p) None of these

-

q) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q35 To which gender do you most identify?

-

a) Male

-

b) Female

-

c) Transgender female

-

d) Transgender male

-

e) Not listed

-

f) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q36 What is the current total size of your pension pot?

-

a) Under £30,000

-

b) £30,000 to £50,000

-

c) £50,000 to £100,000

-

d) £100,000 to £250,000

-

e) Over £250,000

-

f) Over £500,000

-

g) Don’t know

-

h) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q37 What is your marital status?

-

a) Single (never married)

-

b) Married or in a civil partnership

-

c) Widowed

-

d) Divorced

-

e) Separated

-

f) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q38 What is your ethnicity?

-

a) White

-

b) Mixed multiple ethnic groups

-

c) Asian/Asian British

-

d) Black/African/Caribbean/Black British

-

e) Chinese

-

f) Arab

-

g) Another ethnic group

-

h) Prefer not to say

-

-

Q39 Having completed the pension literacy quiz, on a scale of 1 to 5 where 1 is very poor and 5 is excellent; indicate how you would rate your own level of knowledge about pensions?

-

a) 1

-

b) 2

-

c) 3

-

d) 4

-

e) 5

Thank you for completing this survey. Your score is xxx.

-

-

Q40 Do you think that your quiz score will be likely to influence your decision about whether or not to seek independent financial advice in relation to your pension choices?

-

a) Yes

-

b) No

-

c) Don’t know

-

d) Refuse to answer

Thank you for completing this survey.

Authors’ note: Not all demographics are included in Table 1 (indicated by *). This was because there was a lack of representation across subgroups, so they were not analysed further in the study.

-