Introduction

Despite divided public support, American states began passing legislation that bans transgender athletes from competing on teams that match their gender identity in 2020 (Flores et al. Reference Flores, Haider-Markel, Lewis, Miller and Taylor2022; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Flores, Haider-Markel, Miller and Taylor2022). Citing biological differences, Republican lawmakers argued that the bills do not discriminate, but rather, promote fairness and preserve tradition (Sharrow Reference Sharrow2021). In contrast, Democratic legislators have, with few exceptions, opposed athlete bans, arguing that they harm an already vulnerable population and amount to a solution without a problem.

Republican lawmakers have largely introduced and supported athlete bans, but are party preferences the only predictor of voting behavior? Which district or personal attributes led some legislators to cross party lines and vote counter to their party’s position? Unlike studies that examine policy outcomes using the state or the U.S. Congress as the unit of analysis, this research focuses on the voting behavior of individual state legislators on a trans-exclusive policy. Multilevel models are the most efficient approach to evaluating hierarchical data (legislators nested in states) and are employed here to differentiate empirically between state and district level factors.

Prior to the success of athlete bans, most trans-exclusive policies at the state level, such as the infamous “bathroom bills,” were unsuccessful and in some cases met with public outcry (Cunningham, Buzuvis, and Mosier Reference Cunningham, Buzuvis and Mosier2018). Bill supporters found a winning argument with sports where traditional, biological understandings of males and females are highly influential (Kane Reference Kane1995). At a time when questions of gender and identity are central to popular discourse, legislators saw athlete bans as an opportunity to advance their agenda by promoting traditional beliefs and values (Castillo Reference Castillo2023; Martin and Rahilly Reference Martin and Rahilly2023). As Jones (Reference Jones2021) writes, “…the buck stops at sports.”

The success of athlete bans, relative to previously proposed trans-exclusive policies, is significant as the anti-transgender movement expands its agenda at the state and national level. This warrants further investigation considering the current political challenges facing the transgender community, in addition to public attitudes toward transgender people which tend to be more negative than perceptions of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual persons (LGB) individuals (Norton and Herek Reference Norton and Herek2013; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Flores, Haider-Markel, Miller, Tadlock and Taylor2017). This study aims to advance, inform, and encourage future analysis of state legislator voting behavior on transgender policies.

Polarization, constituents, and voting behavior

Party positions on LGBT+ issues have become steadily more polarized since the late 1980s (Bishin, Freebourn, and Teten Reference Bishin, Freebourn and Teten2021; Lindaman and Haider-Markel Reference Lindaman and Haider-Markel2002). Among elites, positions on transgender specific policies are no exception. As an example, transgender athlete bans in U.S. states have passed along highly partisan lines, with 96.16% of Republican legislators voting “yes” and 95.05% of Democratic legislators voting “no.”

The chambers that advanced transgender athlete bans were all Republican majority, raising the question of whether Republicans are supporting athlete bans because they hold the majority or if other factors influence their decisions. Kingdon (Reference Kingdon1977) describes a “field of forces” where lawmakers weigh the influence of critical actors, such as constituents and party leadership, before making voting decisions. Republicans in supermajority chambers would likely be emboldened to vote in favor of athlete bans as the “field of forces” favor their vote.

Nevertheless, the impact of partisanship on support for trans-exclusive policies remains unsettled. Survey data indicate that public support for transgender issues is divided by party (Flores et al. Reference Flores, Haider-Markel, Lewis, Miller and Taylor2022; Parker, Horowitz, and Brown Reference Parker, Horowitz and Brown2022), though citizen attitudes are more nuanced. Young people and women generally support transgender rights (Parker, Horowitz, and Brown Reference Parker, Horowitz and Brown2022), while white men are less supportive (Flores Reference Flores2015; Krimmel, Lax, and Phillips Reference Krimmel, Lax and Phillips2016; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Flores, Haider-Markel, Miller and Taylor2022; Norton and Herek Reference Norton and Herek2013). Highly educated constituents (Haider-Markel Reference Haider-Markel1999) are more likely to support pro-LGBT policies (Parker, Horowitz, and Brown Reference Parker, Horowitz and Brown2022). In addition, other district-based factors such as district ideology (Tausanovitch and Warshaw Reference Tausanovitch and Warshaw2013), electoral competition (Bishin and Smith Reference Bishin and Smith2013), the prevalence of highly religious constituents (Wald, Button, and Rienzo Reference Wald, Button and Rienzo1996), and the urban–rural divide (Parker, Horowitz, and Brown Reference Parker, Horowitz and Brown2022; Scala and Johnson Reference Scala and Johnson2017), lend local context and inform voting behavior on LGBT policy.

The tendency of lawmakers to follow constituent preferences may explain, in part, why legislators will support or oppose this highly visible and salient issue (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Flores, Haider-Markel, Miller and Taylor2022). Legislators advocate for constituents whose beliefs align with their own (Bishin and Smith Reference Bishin and Smith2013). For instance, we might expect a woman Democrat representing young and educated constituents in an urban district to oppose athlete bans, given that this legislator’s party and personal attributes parallel the conventional beliefs of her constituents. Constituent attitudes are known to be particularly influential for white men and women Democrat lawmakers and Black lawmakers, while Republican lawmakers oppose LGB policies, regardless of other factors (Krimmel, Lax, and Phillips Reference Krimmel, Lax and Phillips2016).

Finally, vote homogeneity among members of the same party is not absolute. Both Republicans and Democrats cast votes in opposition to their party. Here, I examine the conditions under which legislators are likely to vote counter to their party’s position. For instance, are these legislators unconcerned about backlash from voters or do competitive districts make it more acceptable to take the position of the opposing party (Bishin and Smith Reference Bishin and Smith2013)?

Data and methods

This study serves as a descriptive analysis of the personal and district level attributes that increase the likelihood that a state legislator will support or oppose a transgender athlete ban. This analysis employs an originally constructed dataset containing 3,867 unique roll-call votes. Absentee and “No Votes” were excluded as it would be challenging to determine why a lawmaker was absent or chose not to vote. The final dataset includes 3,654 “yes” or “no” votes recorded across 28 states during the 2020–23 sessions. By mid-2023, four states had passed athlete bans in one chamber and 24 passed bans in both chambers.

While several states considered multiple athlete bans, only one bill was examined per state, ensuring that each legislator’s vote was only recorded once. Similar to studies that use state legislators as the unit of analysis (Kreitzer Reference Kreitzer2015; Hicks, McKee, and Smith Reference Hicks, McKee and Smith2016; Shor Reference Shor2018), bills in the final passage stage of the policy process are included because lawmakers are more likely to engage in sincere voting once legislation reaches this stage, rather than when it is proposed (Volden Reference Volden1998).

Bills were identified through the Movement Advancement Project (MAP) and the Human Rights Campaign (HRC). Both organizations track the progress of LGBTQ+ bills in state legislatures. The bills in this study prohibit transgender participation on sports teams based on gender identity and are labeled “sports bills” by politicians and the media. While there are slight variations in the provisions addressed in each bill, they are identical in two important ways. First, each explicitly bans transgender girls from participation on sports teams, and second, the bans are uniformly enforced at the secondary education level. A detailed explanation of bill selection and a summary of the contents of each bill is presented in the Supplementary Material.

The state legislatures and individual chambers that advanced transgender athlete bans to the governor’s desk were all Republican majority and 17 had veto-proof supermajorities in both chambers (> = 66% Republican). However, not all states consist of a unified Republican trifecta in the legislature and governor’s office. Bills were vetoed by both Democrat and Republican governors. Athlete bans were typically “dead-on-arrival” in committees in Democrat majority states, where they never received a roll-call vote. Because the bills only advanced in Republican chambers, there are no instances where legislation failed during a roll-call vote.Footnote 1 , Footnote 2

Using multilevel logistic regression, legislators, j, are nested within states, i, and the outcome, y, is the likelihood that a legislator will vote “yes” on a transgender athlete ban. Multilevel models are common in studies exploring the voting behavior of individual legislators. They are utilized in research on abortion (Kreitzer Reference Kreitzer2015), voter ID laws (Hicks, McKee, and Smith Reference Hicks, McKee and Smith2016), and the Affordable Care Act (Shor Reference Shor2018) and are more efficient at separating within-cluster effects (legislator specific attributes) from between-cluster effects (state specific attributes) than fixed effects models, which ignore differences across states (Sommet and Morselli Reference Sommet and Morselli2017).

Votes, coded dichotomously, serve as the dependent variable and were retrieved from state legislative websites or bill archives. Roll-call votes were taken before the bill crossed to the opposite chamber – generally on third Reading – or before the bill moved to the governor’s desk. Nearly 70% of the votes were cast in favor of the legislation. Roll-call votes were taken in Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

In addition to party identification and majority status, race, gender, and sexual orientation play a meaningful role in public support for transgender rights (Flores Reference Flores2015; Norton and Herek Reference Norton and Herek2013). A variable indicating the LGBT+ status of state legislators was incorporated to assess whether legislators who identify as LGBT+ will advocate for the transgender community. Women are more supportive of the trans community than men, but will all female legislators be as accepting regardless of party? Black Americans have become more supportive and tolerant of trans individuals over time (Public Religion Research Institute 2021), but some studies have found that Black Protestants remain divided over gender ambiguity and transgender athlete participation (Barnes Reference Barnes2013; Oldmixon and Calfano Reference Oldmixon and Calfano2007; Public Religion Research Institute 2021). Are Black legislators as conflicted as their constituents despite party identification? Information identifying Black legislators was retrieved from the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. The Center for American Women and Politics maintains a list of women state officeholders and LGBTQ+ identifying legislators were identified through the Victory Institute’s yearly “Out for America” report. Each source is publicly available.

Tausanovitch and Warshaw (Reference Tausanovitch and Warshaw2013) and Warshaw and Tausanovitch (Reference Warshaw and Tausanovitch2022) estimate citizen policy preferences in state legislative districts and find a relationship between district ideology scores and roll-call voting that varies by state. These scores allow for direct comparison of constituent ideological preferences across districts. Assuming that constituents elect representatives who share their policy preferences, district ideology should matter to legislators who stand to lose reelection if voting against their district. The district scores range from −1.07 (liberal) to 0.97 (conservative).

Additional district-level variables specify the age of constituents, the percentage of non-white constituents, the proportion of same-sex partner households, and include a measure indicating the percentage of the district population living in rural areas. Young adults and those with a bachelor’s degree or higher are more supportive of transgender rights (Parker, Horowitz, and Brown Reference Parker, Horowitz and Brown2022). Minority constituents are more likely to embrace Democratic candidates (Scala and Johnson Reference Scala and Johnson2017) resulting in representatives who adhere to corresponding viewpoints. A higher prevalence of same-sex partner households is expected to increase the likelihood that legislators will oppose the bans (Haider-Markel et al. Reference Haider-Markel, Gauding, Flores, Lewis, Miller, Tadlock and Taylor2020). Finally, Wald, Button, and Rienzo (Reference Wald, Button and Rienzo1996) find that urban districts are more likely to enact anti-discrimination protections based on sexual orientation. It then follows that legislators representing more urban districts will oppose athlete bans. Data for each of these variables are publicly available from the American Community Survey.

Evangelical Protestants hold rigid views on gender and exhibit notably more negative attitudes toward transgender persons when compared to their secular counterparts (Kanamori et al. Reference Kanamori, Pegors, Hulgus and Cornelius-White2017). Traditionalist religious groups, such as evangelicals, are also known to oppose gay rights policies (Wald, Button, and Rienzo Reference Wald, Button and Rienzo1996). As a result, legislators in districts with higher proportions of evangelical Protestants are expected to support athlete bans. Data on religious adherents per 1,000 of the population were obtained through the Association of Religion Data Archives and sorted into legislative districts by county.

Finally, a margin of victory (MOV) variable describes the competitiveness of each legislator’s most recent election. What is more important to legislators, reelection or the pressure to follow party cues? Scores range from extremely competitive to non-competitive contests (M = 0.53 SD = 0.38). For example, a legislator with a MOV of 1 had no opponent, whereas a legislator with a MOV of 0.15 represents a highly competitive district. The MOV variable is calculated using Berry, Berkman, and Schniederman’s (Reference Berry, Berkman and Schniederman2000) formula.

Results

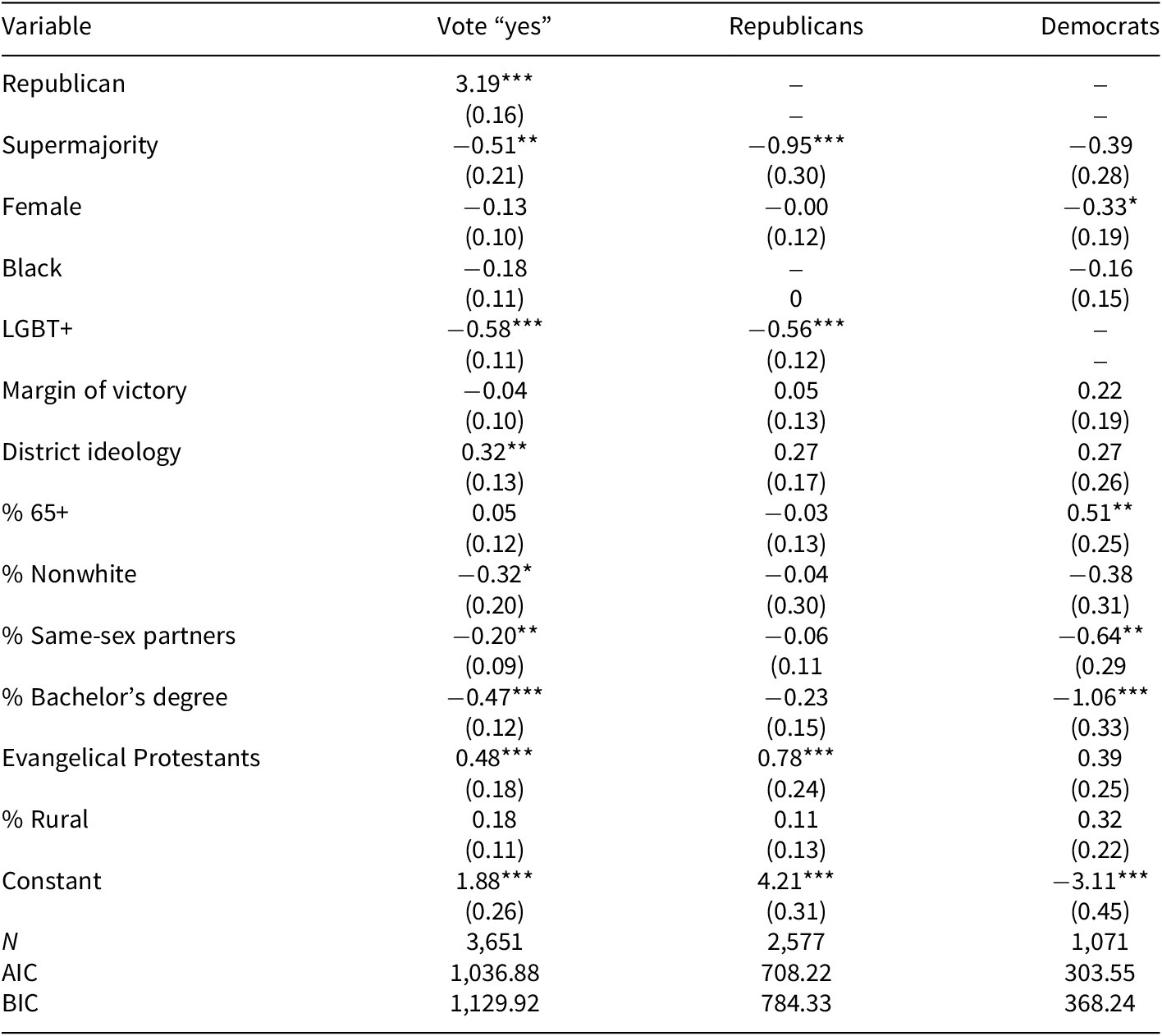

Table 1 displays coefficients and standard errors for the full range of independent variables. The first model comprises all lawmakers who cast a vote on a transgender athlete ban along with a binary variable indicating whether the legislator is a Republican. The Republican and Democratic parties are separated in the second and third models to highlight the importance of party identification on the decision to support athlete bans. Variables are standardized to ease interpretation.

Table 1. State legislators voting “yes” on a transgender athlete bill

Note. Standardized multilevel regression coefficients with standard errors in parenthesis.

AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion.

*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

With few exceptions, state legislators follow partisan preferences when deciding to vote for bills that prohibit participation on teams that align with an athlete’s gender identity. The odds of voting “yes” are 24 times higher if the legislator is a Republican. While not as strong of an association, legislators from conservative districts who represent a greater number of evangelical Protestants have 1.4- and 1.6-times higher odds of voting “yes” to an athlete ban than legislators from liberal districts with fewer highly religious constituents. Also, note that the supermajority variable is significant in the full and Republican model. Interestingly, Republican legislators in simple majority chambers voted “yes” at slightly higher rates (99%) than those in veto-proof supermajorities (95%), which explains the negative coefficient.

Women are more supportive of transgender rights as a demographic group, but this support does not always supersede party (Parker, Horowitz, and Brown Reference Parker, Horowitz and Brown2022). Women legislators are significant in the Democratic model, demonstrating the negative effect that being female has on the likelihood that a Democrat will support an athlete ban. Democratic women legislators are even less inclined than their Democratic male counterparts to support the bills. The Republican model does not show a similar effect, meaning that gender does not influence support or opposition to athlete bans among Republican legislators.

There are few legislators identifying as LGBT in any state, especially conservative states (Haider-Markel et al. Reference Haider-Markel, Gauding, Flores, Lewis, Miller, Tadlock and Taylor2020), but of the LGBT identifying lawmakers in this study, their presence as a voting block was, perhaps unsurprisingly, unsupportive of athlete bans. There are 53 LGBT legislators, seven are Republican and 46 are Democrats. Three LGBT Republicans voted in favor of an athlete ban and represent competitive, conservative, majority white districts in South Carolina, Missouri, and Wisconsin. No Democrat LGBT legislators voted in favor of an athlete ban. Although the LGBT indicator was significant in the Republican model, one should exercise caution before drawing conclusions about the effect of sexual identity on Republican voting behavior, given the limited number of LGBT-identifying Republican legislators.Footnote 3

It is worth noting that the Black legislator variable was not significant in any model. Black legislators were omitted from the Republican model because all 15 Black Republicans voted in favor of transgender athlete bans. Despite this, the odds that a Black legislator will vote “yes” are lower than other control groups and this study found no evidence to support the notion that the conflicted preferences of Black citizens transfer to Black legislators (Bishin and Smith Reference Bishin and Smith2013). Instead, Black legislators adhere to party preferences; Black Democrats generally voted against athlete bans, while Black Republicans always voted in favor.

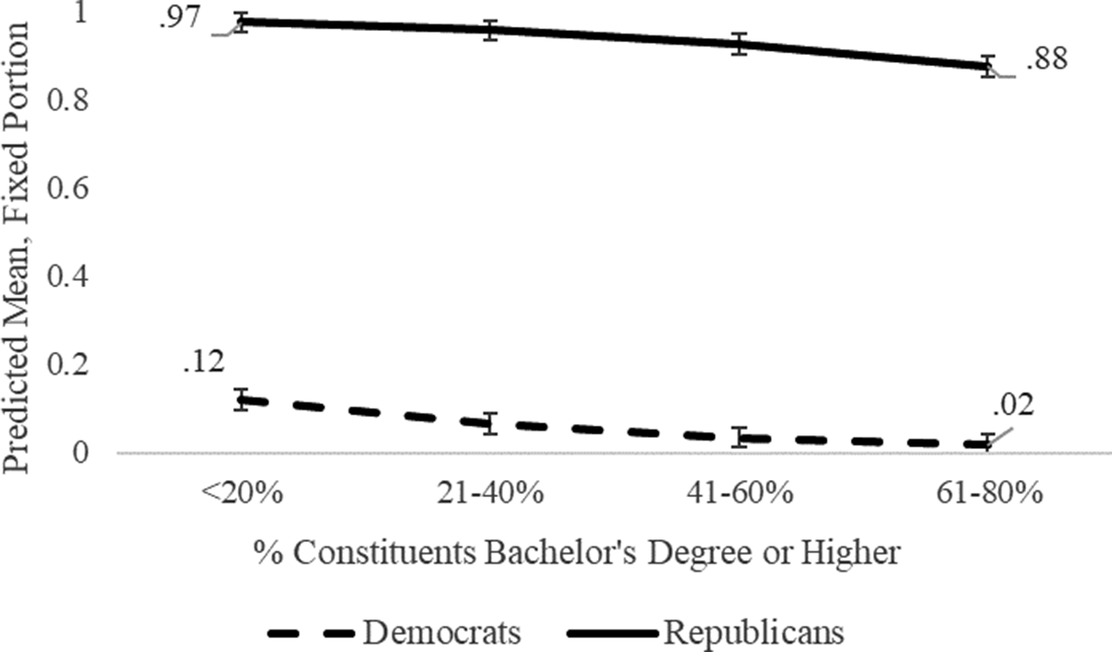

Lower levels of educational attainment are associated with traditional views on gender such as the belief that gender is determined by one’s sex assigned at birth (Parker, Horowitz, and Brown Reference Parker, Horowitz and Brown2022). Figure 1 illustrates the gap between the parties and the probability that legislators will support athlete bans as educational attainment increases in their district. Republicans are slightly less likely to support athlete bans in districts with highly educated constituents and Democrats are slightly more likely to support athlete bans in districts with less educated constituents.

Figure 1. Likelihood of a “yes” vote by party identification and percentage of constituents with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Outcomes were similar when controlling for the percentage of same-sex partner households in a district. Knowledge about transgender people and interpersonal contact with lesbians and gay men foster positive attitudes toward transgender rights (Flores Reference Flores2015). In the absence of direct measures, same-sex partner households serve as a proxy for interpersonal contact between legislators and their LGBT constituents. That is, legislators representing districts with a high percentage of same-sex partner households were less likely to support athlete bans, possibly due to more direct contact with LGBT constituents.

Among Democratic legislators, older constituents increase support for athlete bans while age does not influence Republicans’ voting behavior. Aside from partisanship, Republicans were influenced by one district-level factor: the proportion of evangelical Protestants. In comparison to other religious groups and the religiously unaffiliated, evangelical Protestants express concern that society has gone too far in accepting transgender individuals (Lipka and Tevington Reference Lipka and Tevington2022). The results reflect these findings. Republicans representing a high proportion of evangelicals were two times more likely to vote for an athlete ban.

Voting against party preferences

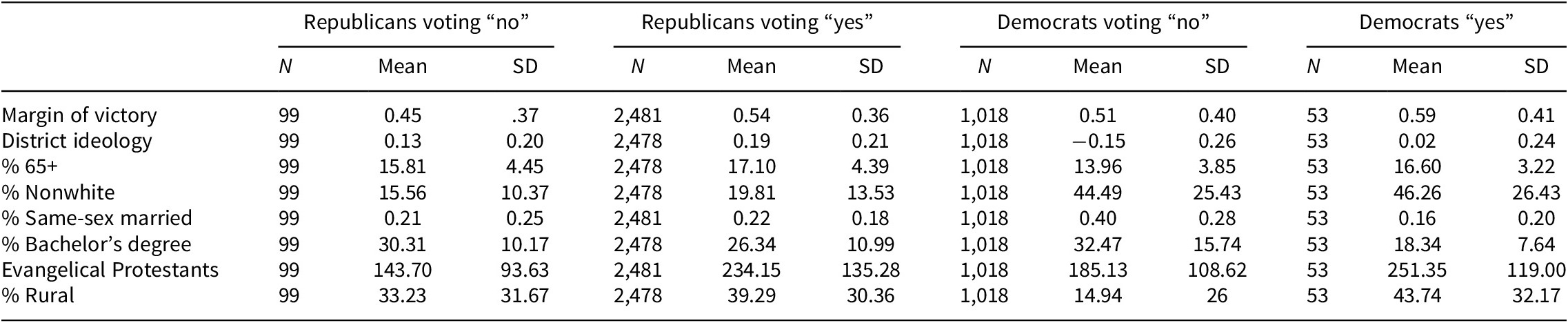

Almost every state had at least one cross party dissenter, but the number of dissenting legislators varied by state. For instance, in Florida two Democrats voted “yes,” in Louisiana, 12 Democrats voted “yes,” and in North Dakota 22 Republicans voted “no.” Overall, 53 Democrats voted “yes” to athlete bans and 99 Republicans voted “no.” What district-level factors distinguish these legislators from their peers?

Table 2 compares the mean and standard deviation of dissenting party members to the district characteristics of party adhering legislators. Republicans who voted “no” on athlete bans compared to those who voted “yes” represented slightly more liberal districts, t(2575) = −3.17, p = 0.002, with a smaller population of evangelical Protestants, t(2578) = −6.59, p = 0.000, non-white constituents t(2575) = −3.09, p = 0.002, and higher levels of educational attainment, t(2575) = 3.54, p = 0.000.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for legislative action across party lines

Note. Margin of victory varies by state.

Means ad standard deviations are not standardized.

Republicans voting “no” had an average 0.45 MOV while the average “yes” vote Republicans had a 0.54 MOV in their last election. In other words, Republicans who voted against their party were slightly more willing to disregard electoral repercussions, whereas, “yes” vote Republicans represented safer districts. This is an interesting aggregate finding but was not the case in every state. MOV varied considerably from state to state and can explain at least some of the within cluster effects, as some states feature more competitive districts than others.

The most striking disparities between “yes” and “no” vote Democrats concerned educational attainment and the urban–rural divide in their districts. Democrats who voted counter to their party represented more rural districts (43.74% rural) than their conforming colleagues (14.94% rural), t(1069) = −7.77, p = 0.000, and also represented districts with far less educational attainment (18.34% with a bachelor’s degree) than their colleagues (32.47%), t(1069) = 6.50, p = 0.000.

Discussion

While positions on transgender policies have become increasingly polarized, there is some evidence suggesting that lawmakers vote in accordance with personal attributes and constituents’ preferences. Factors beyond party, such as constituent educational attainment and evangelical adherence rates, serve to increase or decrease legislative support along with legislator gender and sexual orientation. Democrats from urban districts representing young and highly educated constituents and a high percentage of same-sex partner households, were more likely to oppose athlete bans. Republican legislators were almost entirely motivated by party positions, though districts with large populations of evangelical Protestants were particularly likely to support athlete bans.

Of interest are the 53 Democrats and 99 Republicans who voted in opposition to their party. Cross party voting was rare, but if a Democrat supports an athlete ban, that Democrat is likely male and represents less educated, older constituents, with few same-sex partner households, in a rural district. If a Republican opposes an athlete ban, that Republican likely represents a district with fewer evangelical Protestants.

Was the “field of forces,” as described by Kingdon (Reference Kingdon1977), influencing legislators’ decision to pass athlete bans in supermajority chambers? The supermajority variable was significant in the full and Republican model, but Kingdon’s conception of a “field of forces” encompasses party leadership, constituents, and other interested groups. As an example, consider the chambers that overwhelmingly voted for athlete bans despite knowing that their bill would not pass the opposing Democratic majority chamber (Virginia), or that lacking a veto-proof majority, the Democratic Governor would veto the bill (Wisconsin). In these cases, the district-level variables represent Fenno’s (Reference Fenno1978) notion of the reelection constituency and serve as critical determinants of legislative vote choice. If a legislator represents constituent groups who typically oppose pro-transgender and LGB policies, then the electoral payout for voting in favor of athlete bans is simply too great. Couple this with a Republican Party Platform that explicitly aims to “keep men out of women’s sports” (Republican National Committee 2024). The expectations of constituents and party leadership make it a near certainty that Republican legislators will support such measures. The fact that most chambers held a veto-proof supermajority was merely an added benefit.

When interpreting results, the reader should consider the “nonrandom” selection of states in this study. Athlete bans in Democratic majority states never received a roll-call vote and were not included. The omission of Democratic majority states affects interpretation of the results in two ways. First, there are conditional factors that limit the type of states that can pass these bills. That is, Republican lawmakers in conservative states influenced by state parties committed to this agenda. Second, aside from Virginia, the data are limited to the voting behavior of Democrats in states with two Republican controlled chambers. As such, the results may not reflect the behavior of Democrats in Democratic majority states. Would a Democratic lawmaker in a competitive or conservative district in a liberal state side with their party? This is a question that future research should explore if data become available.

There are other factors that may influence voting behavior on transgender issues, but they could not be examined due to the unavoidable limitations of the data available on state legislators and their districts. Shor and McCarty’s (Reference Shor and McCarty2022) state legislator ideology scores were originally included but were omitted due to data availability (45% missing). This is not ideal, and I urge future studies to utilize these data when they become available. When included in the models, both ideology and party are significant predictors of a “yes” vote. Preliminarily, where ideology appears to have an advantage over party is its explanatory power among legislators who voted against their party. Legislators who crossed party lines tended to be more ideologically moderate than platform adhering party members. The models, with and without ideology scores, are compared in the Supplementary Material.

Notwithstanding, the findings are noteworthy given that much of the extant research on LGBT legislation utilizes states or the U.S. Congress as the unit of analysis rather than individual state legislators. Republican lawmakers in the U.S. have since widened the scope of trans-exclusive legislation proposed in state houses. Athlete bans reflect broader trends (Michos, Figgou, and Baka Reference Michos, Figgou and Baka2022) that the U.S. and global community will contend with into the foreseeable future. Hopefully, future research can use this study as a catalyst for further exploration of legislative voting behavior on the various anti-trans policies, the effects of elite and interest group mobilization, electoral capture, and even studies on anti-trans framing and elite rhetoric.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/spq.2025.4.

Funding statement

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Competing interest

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author biography

Kimberly Martin is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Georgia Southern University. Her research focuses on state politics and public policy, including education policy, LGBTQ+ policy, political leadership, and civic engagement.