Introduction

NHS primary care mental health services in England

Within England, free psychological therapies within primary mental health care are delivered within NHS Talking Therapies for anxiety and depression (TTad). Previously known as Improving Access to Psychological Therapy (IAPT), it aims to provide evidence-based psychological interventions for depression or anxiety disorders (NHS Digital, Reference NHS2022), and was initiated in 2008, with the intention of addressing the lack of evidence-based psychological therapies for people with common mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression (Clark, Reference Clark2011). Since then, the programme has developed and expanded to streamline and improve access to evidence-based psychological approaches (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2024): training thousands of therapists across England, treating millions of clients, reducing waiting times, improving access to therapy, integrating the use of outcome measures and being a model of delivery being disseminated across the globe (Clark, Reference Clark2018).

TTad offers a range of therapies, including low-intensity cognitive behavioural therapy (LICBT), cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), counselling, dynamic interpersonal therapy (DIT), counselling for depression (CfD), couples therapy for depression (CTfD), interpersonal therapy (IPT), psychotherapy, mindfulness and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2024).

Poorer access and outcomes within TTad for clients from diverse backgrounds

TTad was developed to streamline the delivery of therapy and improve access to evidence-based psychological approaches (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2024). The idea is that people from all sections of the community should have an equal chance to benefit from evidence-based psychological therapies.

Despite this, access rates and treatment outcomes in TTad tend to be lower for clients from diverse backgrounds compared with White British clients, as reported by Baker and Kirk-Wade (Reference Baker and Kirk-Wade2024). This trend has persisted over the years, with White individuals being more likely to complete treatment and experience improvement than those from other backgrounds during 2018–2019 (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, McManus, Cooper, Hatch and Das-Munshi2022). Poorer outcomes have specifically been observed for clients of Yemeni, Pakistani and Somali backgrounds, as noted by Arafat (Reference Arafat2021), as well as for Pakistani women, as highlighted by Kapadia et al. (Reference Kapadia, Brooks, Nazroo and Tranmer2017). Harwood et al. (Reference Harwood, Rhead, Chui, Bakolis, Connor, Gazard and Hatch2023) found that clients from Black Caribbean, Black Other, and White Other groups were more likely to be referred to other services rather than receive treatment within TTad. Furthermore, Bhavsar et al. (Reference Bhavsar, Jannesari, McGuire, MacCabe, Das-Munshi, Bhugra and Hatch2021) reported that even after accounting for factors such as English proficiency and reason for moving, individuals who have lived in the UK for less than 10 years are less likely to engage with TTad services.

Access and outcomes to interpreter-mediated therapy in TTad

In writing this, attempts were made to gain access and outcome data for interpreter-mediated therapy with little success. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that poor access and outcomes for clients from diverse backgrounds are compounded when the client requires or requests to have therapy in a language other than English. Overall, assessing the outcomes of interpreter-mediated therapies within the TTad program is challenging due to the irregular reporting of such data as it is not routinely captured or centrally collated. This hinders our ability to evaluate the effectiveness and impact accurately. Without reliable data, it becomes difficult to make informed decisions, optimise interventions, and ensure equitable access to mental health care for all individuals, including those requiring interpreters.

Low uptake of psychological therapies from clients from diverse groups is, in part, due to the limited ability to speak the majority language acting as a barrier (Department of Health, 2005). Interpreter availability results in delays in assessment and appointments, which have negative effects on access or treatment benefits (Harwood et al., Reference Harwood, Rhead, Chui, Bakolis, Connor, Gazard and Hatch2023). Delays can lead to disengagement from treatment (Costa and Briggs, Reference Costa and Briggs2014) and even act as a barrier to accessing therapy (Bernardes et al., Reference Bernardes, Wright, Edwards, Tomkins, Dlfoz and Livingstone2010). Moreover, booking interpreters, especially for less prevalent languages in the localities, can be expensive and delayed (Transformation Partners in Health and Care, n.d.). Some practitioners avoid working with an interpreter, resulting in longer waits, especially if only a few therapists are prepared to work with an interpreter (Costa, Reference Costa2022b). Also, without sufficient training and support, the practitioners report challenges in expressing empathy and extra attention needed for navigating a three-way relationship (Tutani et al., Reference Tutani, Eldred and Sykes2018). The level of competency and proficiency of interpreting within a therapy context can be variable, with some straying away from best practice, e.g. trying to steer the conversation. Other issues relate to the preparation phase, such as booking systems with interpreting companies (which are not regulated) and even a lack of therapist preparation (Costa, Reference Costa2022a).

However, that is not to say that it cannot be done within TTad; Mofrad and Webster (Reference Mofrad and Webster2012) offer a case study which demonstrates the feasibility and positive outcomes of interpreter-mediated psychological therapies. However, they acknowledge some of the complexity and acknowledge the need to address gaps in training and literature.

Efficacy of interpreter-mediated psychological therapy

This lack of research examining the efficacy of interpreter-mediated therapy is not limited to TTad but rather across the board. Several studies are significant as they explored efficacy in relation to psychological therapies offered within TTad.

In relation to LICBT, Lopez et al. (Reference Lopez, Rees and Castro2013) explored the efficacy of an LICBT anxiety management group specifically for Latino migrants in the UK, delivered with the assistance of an interpreter. While their findings indicated a trend toward reduced anxiety levels, the results did not reach statistical significance. In addition, they used focus groups to explore participants’ experiences. Participants valued the practical anxiety management skills in LICBT, appreciating their immediate benefits and ease of use. While they also found conceptual insights helpful, the physiological explanations of anxiety resonated in a culture with prevalent somatisation. Facilitators played a crucial role, with cultural alignment and Spanish-language delivery enhancing engagement. Standardised questionnaires were appreciated for tracking progress. Participants expressed a range of expectations for further support, underscoring the need for more personalised and culturally sensitive approaches.

Research also suggests that interpreter-mediated CBT may be an effective treatment approach. Quiroz Molinares (Reference Quiroz Molinares2024) found no significant differences in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms or treatment outcomes between refugee clients in the Netherlands who received therapy with or without interpreters. Similarly, d’Ardenne et al. (Reference d’Ardenne, Ruaro, Cestari, Fakhoury and Priebe2007a) examined CBT for PTSD among refugees in the UK and found that the presence of an interpreter did not hinder therapeutic progress. Some findings suggested that refugee clients who received interpreter-mediated therapy showed slightly higher rates of improvement compared with those who did not. Further supporting this, Schulz et al. (Reference Schulz, Resick, Huber and Griffin2006) reported that cognitive processing therapy (CPT) was effective among non-US-born refugees receiving therapy in their native language, regardless of whether an interpreter was used. The study noted a particularly strong effect size, highlighting the robust clinical utility of CPT even when delivered in real-world community settings with interpreters. Additionally, Woodward et al. (Reference Woodward, Orengo-Aguayo, Stewart and Rheingold2020) examined the use of prolonged exposure with a Spanish-speaking Latina woman and found clinically significant reductions in PTSD and depression symptoms, reinforcing the feasibility and effectiveness of interpreter-assisted therapy in trauma-focused treatments. However, the evidence base is not conclusive, as Sander et al. (Reference Sander, Laugesen, Skammeritz, Mortensen and Carlsson2019) found that interpreter-mediated CBT was associated with less improvement in PTSD symptoms compared with sessions where no interpreter was used.

While research generally supports the effectiveness of interpreter-mediated CBT, several limitations and variations across studies highlight the need for further investigation. While all the studies examined PTSD treatments, they employed different forms of CBT, including CPT, prolonged exposure, and other trauma-focused interventions. This variation makes direct comparisons challenging and suggests that different interventions may interact differently with interpreter use. Additionally, the studies primarily focused on PTSD, leaving open questions about the efficacy of interpreter-mediated CBT for other mental health conditions typically seen within TTad. The reliance on refugee samples in these studies, while valuable for understanding trauma-focused interventions in displaced populations, may limit the generalisability of findings to other groups with different cultural backgrounds, migratory experiences, mental health needs, and trauma histories.

In relation to counselling, Schiphorst et al. (Reference Schiphorst, Levi and Manley2022) examined the effectiveness of counselling delivered in a client’s primary language versus through an interpreter in an NHS Specialist Language Counselling Service. This study is the first to assess the efficacy of interpreter-facilitated counselling using standardised measures of mental health outcomes. They found no significant differences in treatment outcomes or client satisfaction between the two groups, supporting the effectiveness of interpreter-assisted counselling in line with NICE guidelines. Although there was a trend towards greater improvement in the primary language condition, the findings indicate that counselling with an interpreter is as effective as counselling in a client’s primary language.

Despite the small but growing body of research on interpreter-mediated therapy, significant limitations remain across these efficacy studies, regardless of modality. One key issue is the variation in therapeutic approaches; this inconsistency makes direct comparisons difficult and raises questions about whether certain modalities are more suited to interpreter use than others. Additionally, sample sizes were small, limiting the statistical power of findings and the ability to draw firm conclusions. Furthermore, methodological limitations, such as a lack of long-term follow-up, inconsistencies in how interpreters are integrated into therapy, and limited exploration of proficiency, leave gaps in understanding how these factors influence outcomes. Across all studies, there is a consistent call for further research to refine best practices, explore interpreter-mediated therapy in a wider range of psychological treatments, and better understand the complex dynamics at play in cross-linguistic mental health care.

Guidance on interpreter-mediated therapy within NHSE Talking Therapies

Psychological therapists must work effectively with interpreters to promote accessible psychological therapies, ensure good clinical practice, and achieve equal outcomes and service delivery (Tribe and Lane, Reference Tribe and Lane2009). Costa (Reference Costa2022a), Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2019), Beck (Reference Beck2016), Tribe and Lane (Reference Tribe and Lane2009), Tribe and Thompson (Reference Tribe and Thompson2008) and Tribe and Thompson (Reference Tribe and Thompson2022) offer general guidelines on interpreter-mediated psychological therapies. Moreover, Kunorubwe (Reference Kunorubwe2025) offers a narrative review of recommendations from empirical research in interpreter-mediated CBT. Within the scope of this review, it is not feasible to detail all of the recommendations; therefore, it encourages the reader to delve into the original papers to gain a comprehensive understanding and guidance.

Rationale for the current study

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first paper of its kind to explore barriers specifically related to TTad. The closest similar paper is Gartner et al. (Reference Gartner, Mösko, Becker and Hanft-Robert2024), which explored why many out-patient psychotherapists do not use professional interpreters when treating migrants with limited language proficiency in Northern Germany. Their findings related to structural barriers, like lack of funding and additional workload, and subjective concerns, such as doubts about the interpreter’s suitability and the impact on the therapeutic process.

Despite an onus on ensuring access to interpreters (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2024) and specific guidance for interpreter-mediated psychological therapies (Tribe and Morrissey, Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004; Costa, Reference Costa2022a; Beck, Reference Beck2016; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2019), these recommendations are not always implemented consistently within practice.

The purpose of the research is to explore staff experiences of interpreter-mediated therapy and specific barriers faced in Talking Therapies.

Method

Participants

The sample was a convenience sample with participants recruited primarily online using social media and professional networking sites. The inclusion criteria were working-age adults, currently working within TTad services. A total of 133 participants completed the survey and all participants met the inclusion criteria, and none required exclusion.

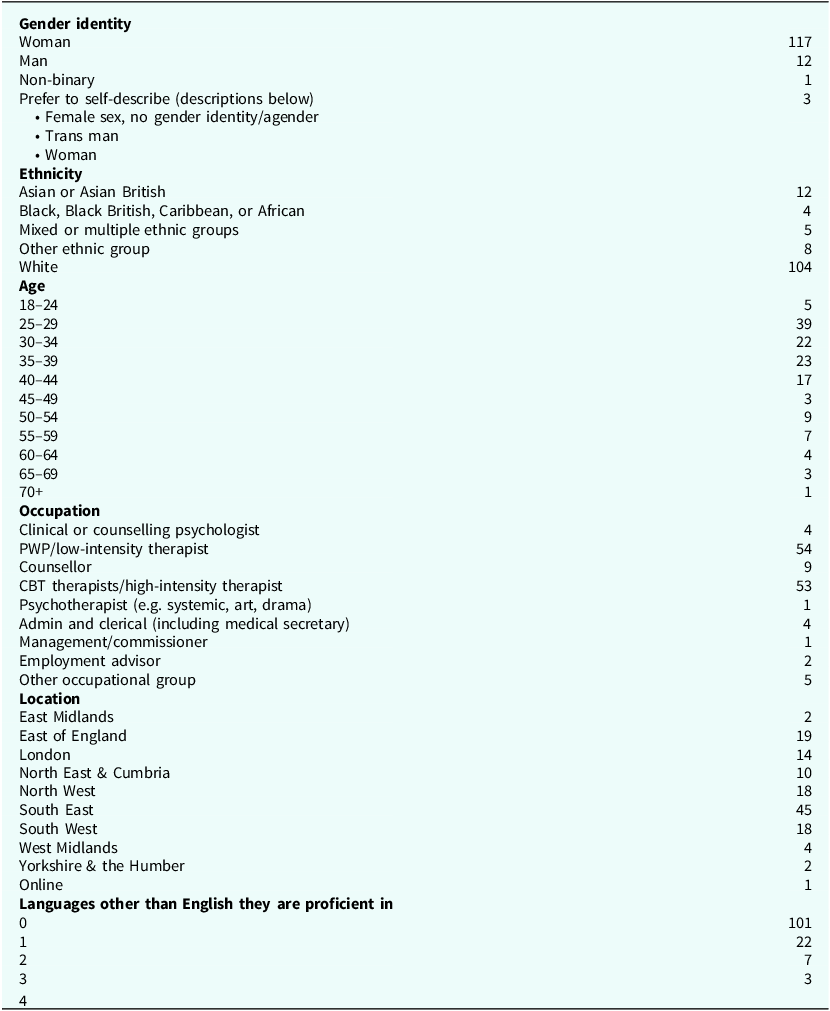

Unfortunately, research papers can lack clarity in reporting the characteristics of the samples, incorrectly interchange descriptors of distinct aspects of identity, omit key data, and even group some aspects of demographics as ‘minority’. Such ambiguity homogenises the sample, neglects nuance, fuels stereotypes, results in imprecise generalisations, and raises questions about relevance (Kunorubwe et al., Reference Kunorubwe, John, Molina, Davies, Gait, John, Roderique-Davies and Lancastle2024). Therefore, within this report, consideration was given to ensure the collection and reporting of information about the sample to provide helpful information about their demographics and identity. Please see Table 1 for a full outline of the demographic details collected.

Table 1. Participant demographic information

The categories related to gender identity were used to provide inclusive and clear options that acknowledge both traditional gender identities and those that exist beyond the binary, ensuring respectful and accurate acknowledgement of diverse gender experiences. The categories related to ethnicity were selected to align with the UK Census classification, providing a clear and consistent framework for capturing the diverse ethnic backgrounds of the population. They ensure comparability with national data and enable the identification of disparities and trends across different ethnic groups. The decision not to use more detailed subcategories was made because of the recognition of issues with diversity within the workforce and the challenges of balancing the need for detailed data and usability. The categorisation of Age, Occupation, Location, and Languages other than English was carefully considered to capture key demographic factors that influence workforce distribution, professional roles, and language proficiency.

However, for the sake of brevity, the sample primarily consisted of individuals who identified as women (87.9%); the majority reported their ethnicity as White (78.1%); most participants were either Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners (PWPs, 40.6%) or high-intensity therapists (HI, 39.8%).

Data collection

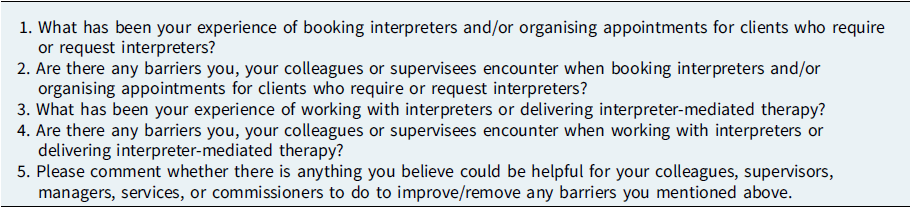

Between April 2022 and September 2022, an online survey was utilised to collect data on professionals’ perceptions of the barriers to interpreter-mediated therapy within NHSE Talking Therapies. This has been selected as it would allow access to a range of participants across a wide geographic spread (Safdar et al., Reference Safdar, Abbo, Knobloch and Seo2016), which was considered important due to the spread of NHSE Talking Therapies services across England. Also, it offers a high degree of anonymity (Terry et al., Reference Terry, Hayfield, Clarke and Braun2017), which is significant as it could allow participants to be candid about experiences and views without fear of being identified or negative consequences. Online surveys tend to be quicker and more convenient (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Baxter and Khanduja2013), which would hopefully suit busy clinicians. Qualitative data were collected and collated using JISC online survey software (JISC, Bristol, UK). Participants answered the questions in their own words in as much depth as they chose (Table 2), resulting in 32 pages (18,428 words) of single-spaced qualitative data.

Table 2. Survey questions on barriers to interpreter-mediated therapy within NHSE Talking Therapies Services in England

Data analysis

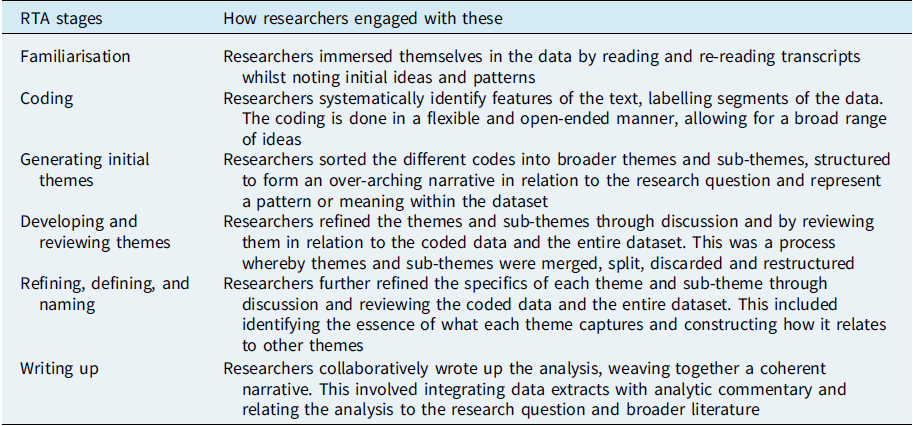

The data analysis in this study employed reflexive thematic analysis, a method emphasising the researcher’s active role in data interpretation and theme generation. Reflective thematic analysis was selected because it offers flexibility, accessibility, and the ability to provide rich/detailed interpretations, enabling an in-depth exploration of clinicians’ experiences. This ensures that the voices and experiences are heard and accurately represented.

This approach prioritises rigorous and systematic coding, researcher reflexivity, and theoretical understanding (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The study’s thematic analysis was grounded in a broadly critical realist, inductive, and descriptive framework, aiming to closely align with participants’ subjective experiences and the work context.

The analysis was conducted by C.O’L. and T.K. Each completed an independent analysis of the data – familiarising, coding, and generation of initial tentative themes. This process consists of six phases, as recommended by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021, Reference Braun and Clarke2023); more detail on how this process was engaged with and the stages can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Detail of how researchers engaged with RTA stages (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021)

These phases characterise the reflexive thematic analysis process, emphasising the active role of the researcher in constructing themes and narratives based on the data and research objectives.

Reflexivity

Recognising the role of positioning in thematic analysis is crucial, as it encourages self-awareness and transparency, and acknowledges the researcher’s active involvement in interpretation and theme generation (Terry et al., Reference Terry, Hayfield, Clarke and Braun2017).

Author C.O’L. is a psychology student entering her third and final year of undergraduate study. She recently completed a placement year in a forensic service, where she developed a strong interest in forensic and clinical psychology. Although she did not have previous experience with working in interpreter-mediated therapy, her curiosity about the research stemmed from a desire to explore potential overlapping barriers between culturally adapted therapies in forensic services and Talking Therapies. Furthermore, she sought to experience a new area of psychology not covered in her undergraduate course.

Author T.K. is a CBT therapist and supervisor working in private practice, as well as a trainer across higher education institutions and a consultant supporting services in improving access and outcomes for clients from minoritised backgrounds. He has a special interest in low-intensity CBT and ensuring that psychological therapies are culturally adapted. Previously, he worked in various Talking Therapies services in the South of England, both as a PWP and as a CBT therapist. In these roles, he has experience arranging and delivering interpreter-mediated LICBT and CBT. Additionally, he has personal experience with the barriers of interpreter-mediated CBT and is interested in exploring whether these barriers are unique to his experience or a common challenge.

J.W. is an undergraduate student currently pursuing an MSci in Applied Psychology (Clinical) program. This degree is designed to qualify him for a career as a PWP within the NHS and provides a masters-level qualification. The program combines elements of the core BSc Psychology with the Postgraduate Certificate in Evidence-Based Psychological Treatments. With prior experience in forensic mental health care, J.W. is particularly interested in the intersection of psychology and mental health treatment and aims to further develop his skills in evidence-based therapies through his studies.

All three researchers kept a journal throughout the research process; this practice allows researchers to contemplate their own perspectives and backgrounds. It allowed researchers to document their evolving thoughts, assumptions, and decisions throughout the analysis process. C.O’L. recognised that not having prior experience with interpreter-mediated therapy might affect her interpretation of the data. On the one hand, it allowed her to provide an outside perspective on the analysis. On the other hand, she remained mindful of avoiding any assumptions about the participants’ perspectives and experiences. After identifying patterns in the analysis, she revisited the data to ensure that her interpretations were built on explicitly stated references rather than her own assumptions on what may have been experienced. For T.K., there was a recognition of how experiences of working within TTad offering interpreter-mediated therapy could enhance the analysis; he was also mindful to not assume other practitioners experiences and perspectives were the same as his. Therefore, throughout the stages of the analysis, he would revisit the data and ensure the codes, themes and sub-themes were being generated from the data. To support this, group discussion among the researchers and supervision was utilised throughout the research. For J.W., there were reflections related to his upcoming clinical training and placement as a trainee PWP. The prospect of working alongside interpreters felt both exciting and challenging; he recognised the unique dynamics of interpreter-mediated interactions and the importance of fostering effective communication to ensure the best outcomes for clients. He anticipated moments where cultural nuances and language barriers might test his adaptability, but also viewed this as an opportunity to grow personally and professionally. Building strong working relationships with interpreters was seen as crucial, and he was eager to approach the role with openness, empathy, and a commitment to delivering inclusive and equitable care.

Results

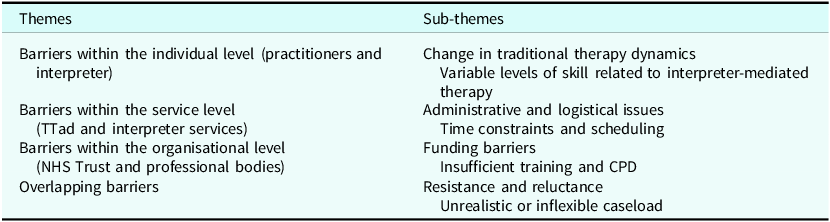

Through the process of data analysis, the researchers identified four main themes and eight sub-themes that captured staff experiences and perspectives on barriers when working in interpreter-mediated therapy within Talking Therapies.

See Table 4 for an overview of themes and sub-themes.

Table 4. Overview of themes and sub-themes

The four themes are as follows: Barriers within an individual level, Barriers within a service level, Barriers within an organisational level, and Overlapping barriers from all three levels.

Theme 1: Barriers within the individual level

Within the first theme, participants’ responses identified key challenges with adapting to changes in traditional therapy dynamics, which disrupted the typical therapist–client relationship and therapeutic processes. Another significant barrier was the variability in certain TTad staff skills, where participants felt that interpreters had differing levels of competence, and even supervisors were sometimes perceived as lacking the necessary experience to effectively support interpreter-mediated therapy.

Sub-theme: Changes in traditional therapy dynamics

This related to how interpreter-mediated sessions changed the conventional therapist–client relationship and altered the ‘traditional’ flow of communication within therapy.

Participants reported experiencing challenges when adapting to changes in traditional therapy dynamics, shifting from a dual to a triadic therapeutic relationship involving an interpreter. They found it difficult to maintain the natural flow of communication, and a significant part of this disruption were challenges in conveying empathy accurately through a third party. This made it harder to express understanding and warmth, which are crucial elements for building a strong therapeutic alliance:

‘I use a lot of humour, warmth and empathy within all my sessions with clients, but when working with interpreters, some seem to have difficulties conveying this in the language that they are interpreting in.’ (Participant 28; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

Within the shift in traditional therapy dynamics, participants expressed concerns about feeling like a ‘third party’ in the therapeutic relationship, as the interpreter became a prominent mediator between the therapist and the client. The alteration in dynamics left certain therapists feeling detached and distanced from the therapeutic process, leading to feelings of doubt about their ability to establish a meaningful alliance with the client when relying on an interpreter to co-produce communication:

‘Hit and miss, some interpreters won’t interpret word for word even when requested and you can find yourself feeling like the third party, even when you try to join the discussion.’ (Participant 53; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

Moreover, participants reported challenges when experiencing deviations from pre-agreed or a lack of defined expectations regarding each participant’s role in the session. When roles and responsibilities were not clearly established, it created confusion and tension:

‘Other times experiences have been problematic is when both interpreter and client speak at the same time, they tend to speak a lot between each other despite setting the expectations at the start or when it is difficult to understand the interpreter.’ (Participant 10; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

With regard to changes in communication, the introduction of an interpreter reportedly altered the natural flow of conversation and increased the risk of miscommunication, making it harder to build rapport. Frequent misunderstandings or mistranslations sometimes led to confusion or misinterpretation of key therapeutic messages, impacting the overall effectiveness of the session:

‘Interpreters changing a client terminology to be easier to translate which can then mislead the session or presentation.’ (Participant 80; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

‘Difficulty with flow of conversations. – The Lost in Translation effect: much like the scene in the Bill Murray film, 30 seconds of dialogue of conversation is often translated into a quick quote, whereby we lose a ton of the nuance and additional information that is often very important.’ (Participant 74; employment advisor)

The changes in traditional therapy dynamics also raised issues related to confidentiality, as involving a third party in therapy sessions heightened concerns about maintaining privacy. Clients might feel less comfortable sharing sensitive information, fearing that their confidentiality could be compromised, particularly when the interpreter belonged to the same community or culture as the client. Additionally, clients expressed discomfort to therapists with having another person in the room, further intensifying worries that the interpreter might breach confidentiality:

‘Some clients are mistrustful of having interpreters due to fear of the interpreter knowing who they are, knowing who their family are, and worries that the interpreter will break confidentiality – there is stigma in some communities about mental health.’ (Participant 7; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

‘Patients are sometimes worried about saying certain things in front of the interpreter because they’re from the same culture and are worried about being judged.’ (Participant 96; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

Sub-theme: Variable levels of skill related to interpreter-mediated therapy

Participants reported variable levels of skill in interpreter-mediated therapy among therapists, interpreters, and even supervisors, which was a considerable barrier at an individual level.

Participants reported experiences of inconsistencies in the reliability of interpreters and interpreting agencies, which negatively impacted their perspectives of interpreter-mediated therapy. Inconsistencies in interpreter competence not only affected the therapeutic alliance but also placed additional strain on therapists who had to adapt their approaches on the fly:

‘It’s difficult as it depends on the interpreter competence as some are good and will translate in first person and everything the client says where as some don’t do a good job.’ (Participant 1; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

Participants noted that therapists often felt inadequately trained to manage the complexities of working with interpreters, leading to uncertainty in experiencing an effective therapeutic process:

‘Low therapist confidence likely acts as a barrier.’ (Participant 113; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

‘I also don’t feel PWPs have had adequate training, it is not covered in the core training and often PWPs, myself included (who has been one for a few years) can feel under confident in their skills and the practical needs of a session.’ (Participant 110; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

Furthermore, supervisors were perceived as lacking the necessary cultural understanding to provide adequate support or guidance, leaving therapists feeling isolated and under-prepared to handle the challenges of interpreter-mediated therapy:

‘I don’t feel my supervisor has any understanding of working with someone of a minoritised background or using interpreter. I’m not sure how much clinical work he even does.’ (Participant 63; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

Theme 2: Barriers within the service level (NHS and interpreter)

While the experiences and perspectives of participants highlighted barriers at an individual level, they also revealed several obstacles at the service level. This theme was primarily associated with issues related to administration and logistics, as well as time and scheduling. Administrative challenges, such as coordinating interpreter availability and managing logistics, often led to delays and disruptions in the process. Additionally, the need to allocate extra time for interpreter-mediated sessions added strain within inflexible services.

Sub-theme: Administrative and logistical issues

Administrative and logistical issues impacted the planning, managing, and organising of interpreter-mediated therapy. This sub-theme encapsulates experiences of a lack of continuity of care, being unable to have the same interpreters consistently, a limited variety of languages offered and technological challenges with remote calls.

Participants reported issues around the administrative processes related to reliability, short-notice cancellations and even interpreters not attending. These disruptions led to wasted appointment slots, poor care, and additional administrative burdens on staff, who were often left scrambling to reschedule or manage the fall-out from last-minute changes:

‘[Company name redacted] cancel bookings all the time due to only confirming them with their interpreters 3 days prior to the appointment even when given multiple weeks warning which means we have to call multiple companies last minute.’ (Participant 121; admin & clerical staff)

‘…interpreter services are not always reliable e.g. turn up to appointments or give short notice cancellation or confirm booking 48 hours prior.’ (Participant 26; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

‘A lot of times the interpreter doesn’t show up which obviously wastes time for the patient and the staff member. It’s also difficult to then rearrange appointments as an appointment needs to be made just to communicate the re-book date.’ (Participant 48; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

Participants also reported not having the same interpreters throughout the course of therapy, creating a lack of continuity of care. This inconsistency required therapists to repeatedly establish new working dynamics and re-explain therapeutic concepts, slowing progress and diminishing the effectiveness of treatment:

‘It’s quite tricky to have the same person which impacts familiarity and the bond of the therapeutic relationship.’ (Participant 43; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

‘I was taught in best practice that booking the same interpreter is best for rapport. This doesn’t happen as the interpreting company state they are unable to do so even when the interpreter themselves agree.’ (Participant 31; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

Participants also raised concerns about some interpreting agencies not allowing for pre-booking or block booking options. The inability to pre-book often led to a delay in sessions and risked negatively impacting the client’s experience, creating feelings of frustration for the participants:

‘[Company name redacted] do not allow you to book in advance so it’s difficult to plan and organise an interpreter for the time you need, especially with a high volume case load as a PWP.’ (Participant 75; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

‘The interpreter service for my trust doesn’t allow me to pre-book telephone interpreter sessions for regular sessions. The really impacts both my client & me.’ (Participant 25; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

Within this sub-theme, further issues revolved around the unavailability of interpreters for certain languages and dialects. Often, the closest available language is chosen as the ‘best alternative’ but this approach can cause delays and lead to further complications in providing effective therapeutic care for some client:

‘We have been unable to source a Mandinka interpreter at all as it is deemed a rare language.’ (Participant 133; primary care practitioner in IAPT, advanced mental health nurse)

‘It is difficult, the forms do not always have enough detail and sometimes an interpreter speaking the wrong language is booked as client has chosen the language closest to their spoken language rather than their dialect.’ (Participant 21; clinical or counselling psychologist)

The accounts seem to be identifying a desire for services to expand the pool of language options to better meet the needs of clients.

In addition to this, technological issues were part of the sub-theme related to administrative and logistical issues. These constraints included: clients and interpreters not having a confidential and quiet space for sessions, not having a device, or a device that works for attending remote calls and connection issues which negatively impacted the quality of remote sessions:

‘We do all our work over telephone so often practical issues come up with clients’ phones not working or not having a confidential space to talk in their accommodation. Or not having an email address and not receiving post in adequate time.’ (Participant 129; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

Sub-theme: Time constraints and scheduling

Participants experienced time constraints due to the inherent time needed for interpreter-mediated therapy. However, this need for additional time can be at odds with service demands. There were clear and frequent requests to allow more flexibility and time, which would allow practitioners to dedicate more hours to individual clients and enhance the quality of therapeutic interventions:

‘By its nature IMCBT takes twice as long as everything gets said twice. So therefore we should have longer sessions and/or more sessions, but this is not clearly mandated. So I know some colleagues are avoiding doing IMCBT as it means extra work but no extra time.’ (Participant 79; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

In addition, this sub-theme related to issues with insufficient time to do the recommended pre-briefing and de-briefing with interpreters. This was reported to have a negative knock-on effect on the therapeutic alliance, not only with the interpreter but also the client’s experience. Participants reported feelings of discomfort as it goes against best practice:

‘I was once told by the interpreting service I wasn’t allowed to debrief the interpreter. I don’t feel comfortable not being able to align with the recommendations for best practice when working with interpreters.’ (Participant 38; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

‘Interpreters only have a set amount of time so best practises such as pre-briefing, post-briefing are not able to be done when conducting appointments over the phone.’ (Participant 103; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

Theme 3: Barriers within the organisational level

This theme is related to broader issues encompassing a lack of adequate funding and insufficient training. The gap in support at the organisational level not only affected the delivery of care but also impacted staff.

Sub-theme: Funding barriers

This sub-theme related to challenges associated with the cost and funding decisions made by organisations. Identifying two varying points of views involving barriers within the funding of interpreters. On the one hand, participants reported the cost of certain interpreting agencies being expensive and prohibitive:

‘The cost associated with interpreters is quite high which sometimes impacts the organisations which we contact.’ (Participant 43; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

‘As service lead – recognition of the costs of interpreting and factoring this into the budget – for inner city services this can be a significant extra cost.’ (Participant 32; clinical or counselling psychologist)

On the other hand, other perspectives suggest that interpreters are not being paid enough by interpreting agencies to encourage them to continue working and, specifically, attend in-person consultations:

‘It can be difficult due to our providers. I don’t think interpreters are paid enough. Interpreters no longer want to work face to face since the pandemic because they now have an easier way of working.’ (Participant 92; Clinical or Counselling Psychologist)

Moreover, it was noted that there is a lack of funding for providing translated materials and resources. Whilst different from interpreting, the lack of written materials translated into other languages meant some participants are using unreliable materials and requiring interpreters to take on the role of translating materials to get through sessions:

‘Definitely a lack of translated materials. We have built a library of these in the service but there are still significant gaps. I try to use google translate but I know this isn’t really reliable.’ (Participant 129; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

Sub-theme: Insufficient training

This sub-theme relates to insufficient training on conducting interpreter-mediated therapy. In relation to therapists, it appeared that interpreter-mediated therapy was not covered within core therapeutic training, leaving many professionals feeling unprepared to navigate working with interpreters. Moreover, there is a lack of further training and continual professional development. This lack of training often left therapists feeling anxious during interpreter-mediated sessions, concerned that their ‘inability’ to communicate effectively could impact the therapeutic alliance and the overall quality of care provided:

‘Whilst my service provides clear and good protocols of how to book interpreters, it’s not sufficient to expect clinicians to just be able to use interpreters in the session without regular CPD/training. It’s not a coincidence that clinicians find it anxiety provoking, since regular training is limited in primary care services and on training programmes.’ (Participant 28; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

‘Not sure if training on working with interpreters is included now in HI and PWP training but it should be if not.’ (Participant 32; Clinical or Counselling Psychologist)

Additionally, participants shared that interpreters may have received minimal or no training in interpreting within a therapeutic context or within mental health care. Participants also emphasised the need for additional funding for mental health training for interpreters:

‘Interpreters are not very good as the companies pay them less and therefore we get people without training.’ (Participant 123; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

‘Better interpreting services, some training for interpreters about the role of IAPT and structure of sessions, set interpreters to work with IAPT so we use the same ones regularly.’ (Participant 31; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

‘Interpreters should have a training about translating what is said and not given their version of what they think is important.’ (Participant 9; Counsellor)

Theme 4: Overlapping barriers within the system.

This theme relates to barriers that span across individual, service, and organisational levels, encompassing issues such as resistance and reluctance and caseload management. These challenges were pervasive and interconnected, affecting not only the experiences of individual therapists but also shaping broader service delivery and organisational practices.

Sub-theme: Resistance and reluctance

This sub-theme related to participants reporting a sense of reluctance or resistance to interpreter-mediated therapy which stemmed from a lack of confidence, insufficient training, time constraints and a change in the traditional therapy dynamic. Some were related to a hesitation or unwillingness to engage in interpreter-mediated therapy:

‘It is very difficult, I don’t feel that I can trust the translator to accurately translate what either I or the client says and a lot of empathy is lost which negatively affects the therapeutic relationship.’ (Participant 80; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

‘It’s a long process (booking) and I don’t like working with interpreters because you never know if it’s being expressed correctly.’ (Participant 4; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

Some related to resistance, which may manifest as therapists or staff members deliberately avoiding these sessions, showing a lack of engagement, or expressing negative attitudes towards the inclusion of interpreters. It is also related to the observation that a small group of clinicians consistently worked with interpreters, while others may avoid it:

‘There is a general resistance to interpreter work so it seems to rely on good will due to anxiety. Getting slots available can be troublesome.’ (Participant 39; management/commissioner)

‘Sometimes clinicians are resistant to accepting interpreter clients as they say they have too many already or don’t have the time to extend the appointment as required.’ (Participant 82; admin & clerical staff)

‘I am not able to deliver therapy in a person-centred way. I find I need to ask more questions to clarify my understanding.’ (Participant 93; Counsellor)

Sub-theme: Unrealistic or inflexible caseload

This sub-theme related to unrealistic or inflexible caseloads, which left little room for the adaptation recommended for interpreter-mediated therapy, an inflexible expectation of workloads meaning there was no ability to compromise and a need for a reduction in their caseloads to ensure the quality of care provided to clients.

Respondents reported that their workloads often did not allow for the necessary adaptations and recommendations related to interpreter-mediated therapy. Many therapists expressed that the high demands of their caseloads left them with insufficient time to implement best practices, such as preparing for sessions with interpreters or tailoring approaches to accommodate the unique dynamics of these interactions:

‘Due to time constraints and nature of our caseloads, we don’t have the time for briefing and debriefing.’ (Participant 7; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

In addition to this, the rigid structure of their workloads did not accommodate the additional time and preparation required for these sessions, making it difficult for therapists to implement necessary adaptations or recommendations. This inflexibility limited their ability to adjust their therapeutic approaches to meet the specific needs of clients requiring interpreter services:

‘We have had some excellent training on working with interpreters but the service is unwilling to support the recommendations that the training advised e.g. giving sufficient time for meeting interpreters before and after appointments.’ (Participant 97; CBT therapist/high-intensity therapist)

‘The service does not allow enough time, case load adjustment for sessions with interpreters – makes them feel like a burden for staff. Less motivated to do them which might consequently impact the service clients are receiving.’ (Participant 29; PWP/low-intensity therapist)

Participants reported a lack of consideration from an organisational and managerial perspective in the unrealistic nature of their current caseloads and stressing resistance and reluctance to work with interpreters:

‘Most therapists don’t realise they can reduce their caseload to do therapeutic work.’ (Participant 39; management/commissioner)

‘We might be given extra time however the number of clients seen in that week is not reduced and it’s a lot of work writing up notes, send out info etc. therefore it can be stressful.’ (Participant 109; primary care mental health worker)

Discussion

Summary of main findings

In this study, four themes were identified: individual, service, organisation and overlapping barriers. Whilst each contain differing barriers, they are interdependent and reciprocal. At the individual level, challenges such as adapting to the triadic relationship and varying levels of skills are influenced and impact on service-level barriers. For example, a therapist encountering difficulty building the therapeutic relationship may be compounded by the service-level problem of not being able to organise a consistent interpreter.

Similarly, service-level barriers around administrative and logistical issues are influenced and impacts on organisational level barriers. For example, difficulties related to not having interpreters attend face-to-face sessions may be compounded by funding issues, how much the interpreter is being paid and whether they have expenses covered.

Moreover, organisational level barriers around training of therapists will be influenced and impacts the individual and service level. For example, many therapists and interpreters appear to have received little or no training on working with interpreters. This affects individual-level challenges by leaving therapists and interpreters under-prepared.

The overlapping barriers appear to be a thread that runs through all levels, where the challenges perpetuate and reinforce one another. For example, unrealistic or inflexible caseloads result in practitioners struggling to familiarise themselves on the best practice guidelines before starting sessions, at a service level where there is service development to address administrative or logistical issues and at an organisational level where there is little flexibility to provide training.

This interconnectedness highlights a need for a holistic, multi-level approach to resolving these barriers, as addressing issues at one level can create a ripple effect that alleviates challenges at other levels. For instance, developing and ensuring reliable administrative processes at the service level would potentially mitigate organisational-level issues by promoting better resource management and funding allocation. A coordinated strategy ensures that each level supports the others, fostering a more cohesive system.

Other notable findings

There were other notable findings in the data that, while not directly related to the primary research question, remain significant enough to mention. These observations provide additional insights into participant experiences and highlight potential areas for further exploration, contributing to a broader understanding of the context surrounding interpreter-mediated therapy.

Proactivity versus hopelessness

Currently, participants are making persistent efforts to stay proactive and create flexibility by finding solutions to the barriers they encounter in their practice. They are reportedly holding onto hope that these challenges are transient in their presence and will eventually be addressed. However, throughout the data there were concerns that if these barriers stay persistent, this could lead to feelings of hopelessness and temptations to avoid working within interpreter-mediated therapy. Participants’ acknowledgements of their feelings have highlighted the importance of addressing persistent and transient barriers and eradicating negative experiences imminently.

This also raises the question of whether staff proactivity is driven purely by personal motivation or if there are also systemic factors that facilitate proactivity and support staff. Exploring how consistent barriers, systemic flaws, and the availability of support impacts these dynamics may provide a clearer picture of why some clinicians remain proactive while others feel reluctant or resistant.

Positive experiences

Whilst the majority of responses in the data express negative experiences, there was a small proportion (n=16) who reported partially positive experiences. In part, these related to a streamlined process of booking interpreters where administration and logistics were effective. Positive responses involving working with interpreters appeared to include instances where guidelines were followed, both roles had been trained, and allowances were made with time and caseloads. It is also of interest that these positive experiences with booking interpreters related to one interpreting agency. This suggests that there are discrepancies with the experiences of booking interpreters, depending on the interpreting agency you use. Although this finding was not directly related to the main research question, it was notable due to its relevance and potential implications for improving service delivery.

Broader context

While the research focused on staff experiences, it is important to acknowledge the broader social and external contexts. Respondents noted that clients may face stigma and shame within their communities, particularly when discussing mental health issues, which can heighten their discomfort in therapeutic settings. Additionally, societal prejudices and systemic inequalities can exacerbate these challenges, contributing to the creation of hostile environments for clients who require interpreters. Some participants highlighted how funding decisions at the organisational level may be influenced by the political climate, potentially limiting resources and support for interpreter-mediated services. This limitation can further impact clients’ sense of belonging and safety, as well as the overall quality and accessibility of care.

Relation to existing literature

The findings of this study align with existing literature on interpreter-mediated therapy. Firstly, despite guidelines on working with interpreters provided by Costa (Reference Costa2022a), Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2019), Beck (Reference Beck2016), Tribe and Lane (Reference Tribe and Lane2009), Tribe and Thompson (Reference Tribe and Thompson2008), Tribe and Thompson (Reference Tribe and Thompson2022), and Kunorubwe (Reference Kunorubwe2025), the analysis identified that staff within TTad are not consistently able to implement these guidelines due to service and organisational issues. For instance, despite recommendations to maintain the same interpreter throughout therapy unless a change is requested by the client (Costa, Reference Costa2022a; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2019; Beck, Reference Beck2016; Costa and Briggs, Reference Costa and Briggs2014; d’Ardenne et al., Reference d’Ardenne, Ruaro, Cestari, Fakhoury and Priebe2007a; d’Ardenne et al., Reference d’Ardenne, Farmer, Ruaro and Priebe2007b; Sander et al., Reference Sander, Laugesen, Skammeritz, Mortensen and Carlsson2019; Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Resick, Huber and Griffin2006; Tribe and Lane, Reference Tribe and Lane2009; Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2008; Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2022; Villalobos et al., Reference Villalobos, Orengo-Aguayo, Castellanos, Pastrana and Stewart2021; Kunorubwe, Reference Kunorubwe2025), several respondents noted that they had not been able to have the same interpreter consistently. Furthermore, contrary to the recommendations that debriefing following a session is essential (Costa, Reference Costa2022a; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2019; Beck, Reference Beck2016; Tribe and Lane, Reference Tribe and Lane2009; Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2008; Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2022; d’Ardenne et al., Reference d’Ardenne, Farmer, Ruaro and Priebe2007b; Villalobos et al., Reference Villalobos, Orengo-Aguayo, Castellanos, Pastrana and Stewart2021; Sander et al., Reference Sander, Laugesen, Skammeritz, Mortensen and Carlsson2019; Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Resick, Huber and Griffin2006), some respondents mentioned not being able to debrief, with one even noting that they were told they were not allowed to do so.

Secondly, these findings highlight barriers related to the training and skills of interpreters, reinforcing concerns raised in existing research. Many respondents indicated that interpreters often lacked specific training in mental health contexts, which aligns with previous studies emphasising the need for specialised training for interpreters working in therapeutic settings (d’Ardenne et al., Reference d’Ardenne, Ruaro, Cestari, Fakhoury and Priebe2007a; d’Ardenne et al., Reference d’Ardenne, Farmer, Ruaro and Priebe2007b; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Herold, Unterhitzenberger and Rosner2023). Our findings further strengthen the call for more comprehensive training programs for interpreters that include education on mental health topics, ethical considerations, and effective communication strategies within therapeutic environments. Ensuring that interpreters are adequately trained not only improves the quality of care but also supports the therapeutic alliance and outcomes for clients.

Thirdly, the findings also align with existing literature by emphasising the clear need for organisational and service-level support to create optimum conditions for interpreter-mediated therapy. This support is crucial to address service pressures and organisational demands, as interpreter-mediated therapy often requires additional time and resources, increasing the workload for therapists (Sander et al., Reference Sander, Laugesen, Skammeritz, Mortensen and Carlsson2019; Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Resick, Huber and Griffin2006). Therapists who feel supported by their organisations are more likely to foster collaborative relationships with interpreters, confidently navigate power dynamics and cultural differences, and manage feelings of guilt or discomfort related to power and privilege (Gerskowitch and Tribe, Reference Gerskowitch and Tribe2021). Conversely, therapists who do not feel supported may experience increased stress, view working with interpreters as a threat to their competence, and adopt a defensive approach (Gerskowitch and Tribe, 2021). Such organisational support includes reducing target pressures, promoting a supportive work environment, encouraging reflective practice, and ensuring logistical issues are managed effectively (Wardman-Browne, Reference Wardman-Browne2023). These measures help facilitate smoother interactions between therapists and interpreters, ultimately leading to more effective therapeutic outcomes for clients.

Fourthly, these findings align with existing literature on the challenges associated with changes in existing therapeutic dynamics due to the presence of an interpreter. Introducing a third party into the therapy session inherently alters the traditional therapeutic dynamic, which can lead to discomfort for therapists. Many therapists expressed feelings of pressure and being scrutinised with the presence of an interpreter, potentially hindering their ability to engage effectively with the client (Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, Resick, Huber and Griffin2006; Mofrad and Webster, Reference Mofrad and Webster2012). This discomfort may stem from concerns about maintaining confidentiality, managing the flow of communication, and ensuring that the therapeutic alliance is not disrupted (Kunorubwe, Reference Kunorubwe2025). However, in contrast, clients generally appreciated the assistance provided by interpreters and did not report issues with having a third person in the session, suggesting that clients perceive the therapeutic environment positively even with an interpreter present (Briggs and Costa, 2014).

Fifthly, the findings about these challenges relate to existing literature that emphasises the importance of developing strong interpersonal and relational skills among therapists and interpreters to manage these changes effectively. Strengthening the triadic relationship between therapist, interpreter, and client is crucial for fostering a collaborative and effective therapeutic environment (Tutani et al., Reference Tutani, Eldred and Sykes2018; Mofrad and Webster, Reference Mofrad and Webster2012). Building trust and safety within this three-way relationship is essential for improving therapy outcomes, as it ensures all parties are aligned in their goals and approach (d’Ardenne et al., Reference d’Ardenne, Farmer, Ruaro and Priebe2007b). Some therapists are concerned that working with interpreters might hinder their ability to build a strong therapeutic bond with clients (Sander et al., Reference Sander, Laugesen, Skammeritz, Mortensen and Carlsson2019; Wardman-Browne, Reference Wardman-Browne2023). Furthermore, the interpreter’s non-involved stance in certain interpreting models can contradict the therapist’s empathic approach, potentially disrupting the therapeutic process. However, when interpreters mirror the therapist’s empathy, therapy outcomes improve, underscoring the importance of alignment in therapeutic attitudes (Tutani et al., Reference Tutani, Eldred and Sykes2018). These findings highlight the need for therapists and interpreters to develop strategies that maintain the integrity of the therapeutic relationship while navigating the complexities introduced by interpreter-mediated therapy.

Finally, the different perspectives related to funding – where some respondents reported that interpreters do not receive enough pay while others described interpreting agencies as too expensive and unaffordable – raise critical questions about the disparity between the costs of interpreting services and the low pay for interpreters. This discrepancy potentially highlights a deeper issue regarding how resources are allocated within interpreting agencies. Such challenges may lead to reluctance among both therapists and interpreters. This situation underscores the importance of communication and collaboration across all levels to achieve equitable funding. Costa (2023) further emphasises that some interpreting companies may underpay or rely on less qualified interpreters as a cost-cutting measure, which could explain some of the challenges noted above. This aligns with recommendations from Tomkow et al. (Reference Tomkow, Prager, Drinkwater, Morris and Farrington2023) for policymakers to reconsider their approach to interpretation provision, shifting the focus from cost-cutting to quality assurance. The findings of this research also highlight the critical need for mental health services and organisations to establish robust quality control measures when engaging interpreting services. It is imperative that agencies providing interpreters are thoroughly vetted for their policies, ensuring that interpreters are trained and supported and that they are fairly paid. Ultimately, addressing these issues will not only enhance the quality of interpreter-mediated therapy but also ensure a more equitable and supportive environment for both clients and practitioners.

Clinical implications

The findings from this study have significant clinical implications for the delivery of interpreter-mediated therapy within TTad. Clearly, work needs to be done to address the barriers across all levels – whether it is the individual practitioner, the service, or the organisation. Practitioners need to actively recognise their own resistance or reluctance towards working with interpreters and use self-reflection and supervision to address these issues. Supervisors should be equipped and encouraged to support practitioners in working with interpreters, fostering more effective communication, greater collaboration, and improved patient care in diverse clinical settings. Moreover, there is a need for acknowledging and addressing language discrimination in healthcare by all stakeholders, whether practitioners, supervisors, managers, commissions and so on, to address the unfair treatment of clients who require or request an interpreter rather than an implicit acceptance of substandard care (Tomkow et al., Reference Tomkow, Prager, Drinkwater, Morris and Farrington2023).

Without accurate data on interpreter-mediated therapy, identifying and addressing barriers becomes impossible, underscoring the need for consistent and centralised reporting on the number of clients requesting and receiving such services within TTad. Without examining these issues systematically, how can we encourage and support better practice? A lack of high quality data not only prevents meaningful improvements but also perpetuates disparities in access to quality care.

Despite existing guidelines on interpreter-mediated therapy, these are not always implemented within Talking Therapies. There is a critical need to ensure adherence to best practice guidance, both in the training of therapists and in the provision of adequate supervision and support. Additionally, interpreters themselves require specialised training to support therapeutic interventions effectively.

Managers, services, commissioners, and NHS England must review contracts and procurement arrangements to ensure that the mechanisms for arranging and delivering interpreter-mediated therapy do not face additional barriers. It is crucial to build in mechanisms that ensure interpreter-mediated therapy is given parity in importance, such as in waiting times and quality of care. Finally, the study underscores the importance of ensuring sufficient training, supervision, and support for therapists to overcome the challenges of interpreter-mediated therapy, and to provide high-quality care to all clients, regardless of language.

Research recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, several recommendations for future research are proposed to further understand and address the barriers to interpreter-mediated psychological therapies. Comparative research is needed to assess the effectiveness of interpreter-mediated therapy in routine practice in TTad, across different therapeutic modalities and client demographics. This will help determine whether specific therapies or client populations are more affected by barriers to interpreter-mediated therapy.

Implementation research should explore how existing guidelines for interpreter-mediated therapy can be better integrated into routine practice. This involves identifying factors that facilitate or hinder the adoption of best practices and developing strategies to overcome these obstacles.

Future research should focus on testing and evaluating strategies designed to reduce therapists’ resistance or reluctance to interpreter-mediated therapy. This could include enhanced training programs or changes in supervision practices.

Future research should explore supervisors’ experiences of supporting therapists who are working with interpreters, particularly how their level of experience and confidence influences their ability to provide effective support, guidance, and culturally responsive supervision in clinical settings.

Improving data collection and reporting mechanisms is also essential. Accurate and regular data on the number of clients requesting and receiving interpreter-mediated therapy will help identify trends, monitor outcomes, and address barriers at all levels. This will ensure that interventions are informed by reliable and up-to-date information.

Research into cultural competence and training for both therapists and interpreters should continue, evaluating the impact of such training on the effectiveness of interpreter-mediated therapy. Studies should identify which aspects of training are most beneficial and how they influence the therapeutic process and client outcomes. Additionally, future research should incorporate client perspectives to understand their experiences with interpreter-mediated therapy, particularly regarding the therapeutic relationship and overall effectiveness.

Expanding research to include various mental health services (primary, secondary, and specialist) across the UK will provide a more comprehensive view of interpreter-mediated therapy barriers and ensure that solutions are applicable in diverse contexts. Furthermore, exploring the causal relationships between distinct levels of barriers (individual, service, organisational and overlapping) will aid in developing targeted interventions.

Lastly, addressing the sources of resistance or reluctance among therapists and evaluating service development initiatives and organisational changes are crucial. Research should investigate the roots of resistance and how it can be effectively managed through training, supervision, or systemic changes. Implementing and evaluating these changes will offer valuable insights into the most effective strategies for overcoming barriers and improving interpreter-mediated therapy practices.

By addressing these research gaps, we can develop a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the barriers to interpreter-mediated therapy and identify effective strategies for overcoming them across all levels of practice.

Limitations

The study on barriers to interpreter-mediated therapy within TTad has several limitations that need to be considered when drawing conclusions from its findings.

A significant limitation of the study is the over-representation of specific demographic groups. For instance, in relation to ethnicity, the study may not capture the experiences and perspectives of individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds. However, this may be less of an indication of the study but more an artefact of the demographics within the workforce as the TTad workforce is majority female and majority white ethnicities. The TTad workforce data for 2022, reports 82% female and 81% from white ethnic backgrounds (NHS Benchmarking, 2022).

Another limitation is that the study recruited a relatively small sample size, especially considering the workforce census reported a total of 13,779 staff in TTad (NHS Benchmarking, 2022). The sample size of 133 accounts for 0.96% of the total workforce. The small sample size may not provide a comprehensive understanding of the barriers faced by interpreters and therapists across the board. This is a limitation when considering the entire workforce and would call for an exploration of barriers with a more sizeable sample.

The study noted regional disparities in response rates, with some localities, such as the West Midlands and York and the Humber, having lower responses. This suggests that the findings may not adequately represent the experiences and challenges faced by interpreters and therapists in these regions. Regional variations in healthcare settings and practices are significant factors that might be under-represented.

The study utilised a questionnaire to efficiently gather data from a large number of participants, but this method has limitations in exploring the depth and nuances of qualitative research. The use of an online survey restricted the ability to engage in an in-depth exploration of responses, potentially impacting the richness and context of the findings. To address these limitations, future research should consider alternative approaches, such as interviews or focus groups, which could provide a more detailed understanding of the barriers by allowing for deeper probing and elaboration on participants’ experiences.

Another limitation of the study is the relatively small number of participants who were counsellors, psychologists, managers, and administrative staff. This limited representation of some key roles within TTad may affect the comprehensiveness of the findings, as perspectives from these groups are crucial for a full understanding of the barriers to interpreter-mediated therapy. To the authors’ knowledge, existing studies have not extensively explored the perspectives of some of these specific roles, e.g. managers or administrators, suggesting that future research could benefit from a more targeted investigation into their unique experiences and insights.

In summary, while the study provides valuable insights into the barriers to interpreter-mediated therapy within TTad, it is crucial to acknowledge these limitations. Researchers and policymakers should consider supporting further research to understand and address complex issues surrounding interpreter-mediated therapy in the NHS effectively.

Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore the complex and interdependent barriers regarding interpreter-mediated therapy within TTad. By recognising that challenges at one level can significantly impact other levels, stakeholders can implement strategies that foster collaboration and resource allocation, ultimately enhancing the quality of care provided to clients requiring interpreter services. While some participants exhibited proactive behaviours to navigate these barriers, the risk of burnout and hopelessness remains a critical concern if systemic issues are not addressed. Furthermore, the occurrence of positive experiences highlights the potential for improvement when proper training, streamlined processes, and supportive environments are in place. This research aligns with existing literature, reaffirming the need for training for both interpreters and therapists, adherence to best practice guidelines, and organisational support to create a conducive environment for interpreter-mediated therapy. Additionally, there is a gap in the existing research on interpreter-mediated therapy, making further exploration essential to identify innovative solutions and best practices that can address these challenges and ultimately contribute to improved experiences and outcomes for all involved.

Important note about terminology

When referring to interpreters, it is specifically about spoken language interpreters who communicate the spoken word from one language to another, which should not be confused with translators, who translate the written word (Costa, Reference Costa2022a). In describing individuals accessing psychological therapies, this report will interchangeably use commonly used terms such as ‘patients’, ‘clients’, ‘service users’, and others in common usage.

This approach aligns with recommendations in Kunorubwe (Reference Kunorubwe2023) to be mindful of terminology, as it can have real-world impact on the individuals we work with, our colleagues, services, and even policy. Hence, we must continually reflect on our terminology, explicitly acknowledge how we are using it, and recognise that no single term is universally suitable for all our stakeholders.

Key practice points

-

(1) Encourage therapists to engage in regular self-reflection and supervision to address any reluctance or resistance they may have toward working with interpreters. Additionally, foster open communication among all stakeholders – including therapists, interpreters, administrative staff, and organisational leaders – to collaboratively identify challenges and solutions in the interpreter-mediated therapy process.

-

(2) Develop and implement comprehensive training and skill development programs for both therapists and interpreters that focus on effective communication strategies, cultural competence, and the dynamics of interpreter-mediated sessions.

-

(3) Supervisors should reflect on and actively develop their understanding and skills in working with interpreters to provide effective guidance and support to practitioners, ensuring clear communication, cultural responsiveness, and high-quality patient care. To support this, supervisor training programs should include competencies for supervising interpreter-mediated therapy.

-

(4) Wherever possible, therapists, supervisors, managers, interpreters, and other stakeholders should act as allies in challenging systemic barriers to equitable care. Working together to acknowledge and address language discrimination in healthcare can help to shift the culture away from the widespread yet often unacknowledged acceptance of substandard care. See Tomkow et al. (Reference Tomkow, Prager, Drinkwater, Morris and Farrington2023)

-

(5) Establish efficient administrative and logistical processes for booking and managing appointments with interpreters. This includes ensuring booking confirmations, consistency in interpreter assignments, the ability to pre-book for the duration of therapy, and a plan should the interpreter be unavailable.

-

(6) Create a supportive culture that enables the ideal conditions for interpreter-mediated therapy by providing adequate resources, reducing workload pressures, allowing necessary time for sessions, and offering flexibility for therapists to engage in training.

-

(7) Conduct a comprehensive review of contracts and procurement processes, ensuring robust quality control mechanisms for interpreting agencies, including thorough vetting of their training, support, and compensation.

-

(8) Encourage collaboration among lived experience advisors, therapists, interpreters, services, healthcare organisations, and interpreting companies at all levels to improve communication and understanding of the unique challenges and needs associated with interpreter-mediated therapy.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, T.K.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to Cardiff University’s Undergraduate Summer Internship scheme for facilitating Caitlyn O’Leary’s invaluable assistance and contributions to this research project, as well as to the University of Reading’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (UROP) for facilitating Joshua Wynne’s invaluable assistance and contributions to this research project. The authors would like to thank Pawel Kaliniecki, Katy Emerson, Kate Sheldon, Joanne Williams, Natalie Meek and Layla Mofrad for their support and encouragement. We would also like to thank all the Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression staff for sharing their insights and participating in the study, as well as those who helped share the research.

Author contributions

Taf Kunorubwe: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (joint), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Caitlyn O’Leary: Formal analysis (joint), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing – original draft (joint), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Joshua Wynne: Formal analysis (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests with respect to this publication.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Faculty of Life Sciences and Education (FSLE), University of South Wales, before it was conducted (reference number 22TK03LR). All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study. The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.