Introduction

The transfer of theoretical knowledge into practice is considered a crucial aspect of therapist competence development (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Muse et al., Reference Muse, Kennerley and McManus2022). Derived from information processing theory, Bennett-Levy (Reference Bennett-Levy2006) proposed a model of therapist skill development that focuses on three related systems: the declarative, the procedural and the reflective (DPR) system. The declarative system encompasses factual knowledge, for example knowing symptoms of a depressive episode. Declarative knowledge is assumed to be acquired by reading, listening to lectures or observational learning (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009). As training progresses, it is assumed that declarative knowledge will transform into more practical abilities, namely procedural knowledge. Procedural knowledge refers to the actual application of knowledge in practice and is defined as ‘knowledge of how to and when to rules’ (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; p. 59) or ‘practical understanding of application of cognitive-behavioural therapy’ (Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013; p. 488). Novice therapists are assumed to build their procedural knowledge by didactic learning, modelling and feedback (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009). Bennett-Levy (Reference Bennett-Levy2006) suggests that strategies for building competence change at different stages of training. While declarative and procedural processes are especially relevant for novice therapists, the reflective system becomes more relevant for more experienced therapists. Reflection is defined as a metacognitive process, encompassing ‘the observation, interpretation and evaluation of one’s own thoughts, emotions and actions, and their outcomes’ (p. 60). The DPR model has since been widely applied in psychotherapy competence research, and has been adapted to different modalities and contexts (e.g. Churchard, Reference Churchard2022).

In accordance with the DPR model, it is assumed that procedural knowledge is based on declarative knowledge. However, only few studies have investigated the empirical relationship between different aspects of competence. In an experimental study, the communication and therapy skills of 69 psychology students were trained and compared in terms of their theoretical and procedural knowledge (Heinze et al., Reference Heinze, Weck, Maaß and Kühne2023). The results indicated that procedural knowledge was significantly correlated with communication and therapy skills and predicted the level of skills after a training intervention. Similarly, in a naturalistic study, 219 psychotherapy trainees were assessed over a 3-year period and compared with a control group of psychologists without postgraduate psychotherapy training (Evers et al., Reference Evers, Schröder-Pfeifer, Möller and Taubner2022). Over the course of the study, the trainees demonstrated an increase in procedural knowledge, along with declarative knowledge. However, it was only in procedural knowledge that the trainees outperformed the control group over time.

In order to assess procedural knowledge, it is recommended to use an open-response format, such as in short-answer clinical case vignettes or written case reports, as this approach reduces guesswork and allows for more complex answers (Muse et al., Reference Muse, Kennerley and McManus2022; Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013). For example, Eells and colleagues (Reference Eells, Kendjelic and Lucas1998) provide an elaborate coding method for evaluating comprehensive case conceptualisations, a method that is frequently employed in training research (e.g. Evers et al., Reference Evers, Schröder-Pfeifer, Möller and Taubner2022). However, this method necessitates considerable resources, both in terms of writing and the subsequent evaluation. In contrast, shorter case vignettes provide standardised information and facilitate more efficient assessment and evaluation (Muse et al., Reference Muse, Kennerley and McManus2022; Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013).

Few measures have been developed to assess procedural knowledge. Heinze and colleagues (Reference Heinze, Weck, Maaß and Kühne2023) introduced written case vignettes with multiple-choice answer options but reported improvable indices for item difficulty and item discrimination, suggesting that the items were either too easy to solve or that participants with different knowledge levels could not be distinguished sufficiently. Based on these findings, the authors propose to use video-based vignettes with an open response format instead (Heinze et al., Reference Heinze, Weck, Maaß and Kühne2023). In a similar attempt, situational judgement tests (SJTs), written or video-based, present participants with hypothetical clinical scenarios. Participants indicate how they would behave in these situations based on the given answer options (Campion et al., Reference Campion, Ployhart and MacKenzie2014). Another exemplary assessment tool was developed by Myles and Milne (Reference Myles and Milne2004), the so-called Video Assessment Task. It involves a short (simulated) patient video and open questions about the reported symptoms, problems and suitable treatment techniques. The authors report good inter-rater reliabilities but no other psychometric data (Myles and Milne, Reference Myles and Milne2004).

In summary, the existing measures for the reliable assessment of procedural knowledge in clinical psychology, contrary to recommendations, frequently rely on pre-defined answer options and often lack sufficient psychometric reporting (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Becker-Haimes and Kendall2020; Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013).

Objective

We thus aimed to develop and validate a psychometrically sound instrument for the assessment of procedural knowledge in clinical psychology (the Pro CliPs Task), that would allow for a resource-efficient application and assessment. This project aimed to:

-

Evaluate the Pro CliPs Task regarding its inter-rater reliability, item characteristics, applicability and authenticity (feasibility study), and to

-

Examine the instrument’s validity (evaluation study).

Method

Data were collected in a multi-stage process, which included conceptual development (pre-tests 1 and 2, expert survey), a feasibility study and an evaluation study. The study project was approved by the university’s ethics committee (55/2023) and pre-registered prior to data collection (Paunov et al., Reference Paunov, Weck and Kühne2024b).

Conceptual development of the Pro CliPs Task

The structure of our instrument was derived from tasks commonly used for the assessment in medical education and research (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Hanstock and Clark2017; Daniel et al., Reference Daniel, Rencic, Durning, Holmboe, Santen, Lang, Ratcliffe, Gordon, Heist, Lubarsky, Estrada, Ballard, Artino, Da Sergio Silva, Cleary, Stojan and Gruppen2019; Epstein et al., Reference Epstein, Hooper, Weinfurt, DePuy, Cooper, Harless and Tracy2008; Peabody et al., Reference Peabody, Luck, Glassman, Dresselhaus and Lee2000; Schmidmaier et al., Reference Schmidmaier, Eiber, Ebersbach, Schiller, Hege, Holzer and Fischer2013). These tasks entail the concise presentation of a clinical case vignette followed by questions about the vignette. In the field of medicine, these questions typically encompass areas such as (differential) diagnosis, necessary steps in the evaluation process, therapeutic measures and medication or correct behaviour in specific situations. In the context of clinical psychology, these elements are reflected in the formulation of a case conceptualisation. A case conceptualisation (or formulation) consists of hypotheses about the causing and maintaining influences of a person’s problems and serves to guide therapy in identifying treatment goals and suitable interventions (Kendjelic and Eells, Reference Kendjelic and Eells2007).

A common framework for case conceptualisations is the trans-theoretical ‘5 Ps model’ (Dudley and Kuyken, Reference Dudley, Kuyken, Johnstone and Dallos2013; Kendjelic and Eells, Reference Kendjelic and Eells2007; Polipo et al., Reference Polipo, Willemsen, Hustinx and Bazan2024; Weerasekera, Reference Weerasekera1993). The framework asks therapists to describe the patient’s ‘presenting problem’ and complement their analysis with ‘precipitating factors’ (which triggered the current symptoms), ‘predisposing factors’ (which increased the patient’s vulnerability to the development of their problems), ‘perpetuating factors’ (which maintain the patient’s problems in the present) and ‘protective factors’ such as the patient’s resources (Weerasekera, Reference Weerasekera1993). Given its generic nature and widespread acceptance (Bucci et al., Reference Bucci, French and Berry2016; Polipo et al., Reference Polipo, Willemsen, Hustinx and Bazan2024), we decided to base the information in the case vignettes and corresponding questions largely on the ‘5 Ps model’.

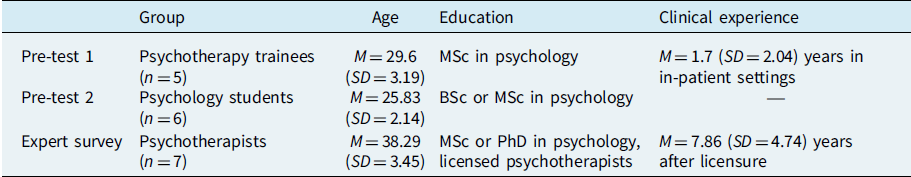

Construction of videos and questions

First, written case vignettes were developed, providing the information possibly needed to answer the questions following the ‘5 Ps model’. The scripts were based on fictitious patient histories, diagnostic criteria (World Health Organization, 2009) and casebooks (World Health Organization, 2012). To cover a broad spectrum of mental disorders, multiple case vignettes exemplifying the most prevalent mental disorders (Jacobi and Kessler-Scheil, Reference Jacobi and Kessler-Scheil2013) were developed, with corresponding open-ended questions. The scripts and questions were discussed within the team of researchers and refined in an iterative process to ensure coherence and authenticity. After the construction was completed, a first pre-test using the written case vignettes was conducted with five psychotherapy trainees (see Table 1 for characteristics of all groups involved in the construction process). The pre-test aimed to assess comprehensiveness, duration and usability of the task. As a result, the case vignettes and questions were refined.

Table 1. Characteristics of groups involved in the construction process

Subsequently, all case vignettes were videotaped with simulated patients (SPs), portraying the content of the written case vignettes. The majority of SPs were actors, female (71%) and with a mean age of M=47.29 years (SD=15.41, range 27–65). They memorised the script and received a 1-hour training session on the study project, rules for their portrayal and details on their role. All SPs received an expense allowance of €50.

Afterwards, a second pre-test was conducted using the video-based case vignettes. Six psychology students (see Table 1) evaluated the authenticity of the videos in addition to the feasibility, comprehensiveness and usability of the instrument. Therefore, think-aloud and probing techniques were used. Participants were further invited to provide open feedback. Based on their feedback, minor changes were made to the wording of the questions in order to make them more specific and easier to understand.

Construction of the coding method

For the evaluation of the responses to the open-ended questions, a unique coding system was developed. The objective was to devise a coding system that would facilitate a simple and efficient evaluation of the answers, while enabling the differentiation between incorrect (0), mostly incorrect (1), mostly correct (2) and completely correct (3) answers. For this purpose, seven experienced psychotherapists (see Table 1) completed the case vignettes. Their responses were then combined with information from clinical guidelines and disorder-specific manuals (e.g. Bandelow et al., Reference Bandelow, Wiltink, Alpers, Benecke, Deckert, Eckhardt-Henn, Ehrig, Engel, Falkai, Geiser, Gerlach, Harfst, Hau, Joraschky, Kellner, Köllner, Kopp, Langs, Lichte and Beutel2021; Hautzinger, Reference Hautzinger2021) and summarised in a coding sheet giving examples of incorrect, mostly incorrect, mostly correct and completely correct responses for each case vignette. The coding sheet aims to provide guidance for the raters when evaluating the open-ended responses. Similar to the case formulation content coding method proposed by Eells and colleagues (Reference Eells, Kendjelic and Lucas1998), our coding system takes into account not only the accuracy of the content but also the use of terminology, the diversity of solution ideas, and the level of elaboration and abstraction. This was assumed to be relevant for distinguishing between different knowledge levels (Eells et al., Reference Eells, Kendjelic and Lucas1998).

The Pro CliPs Task

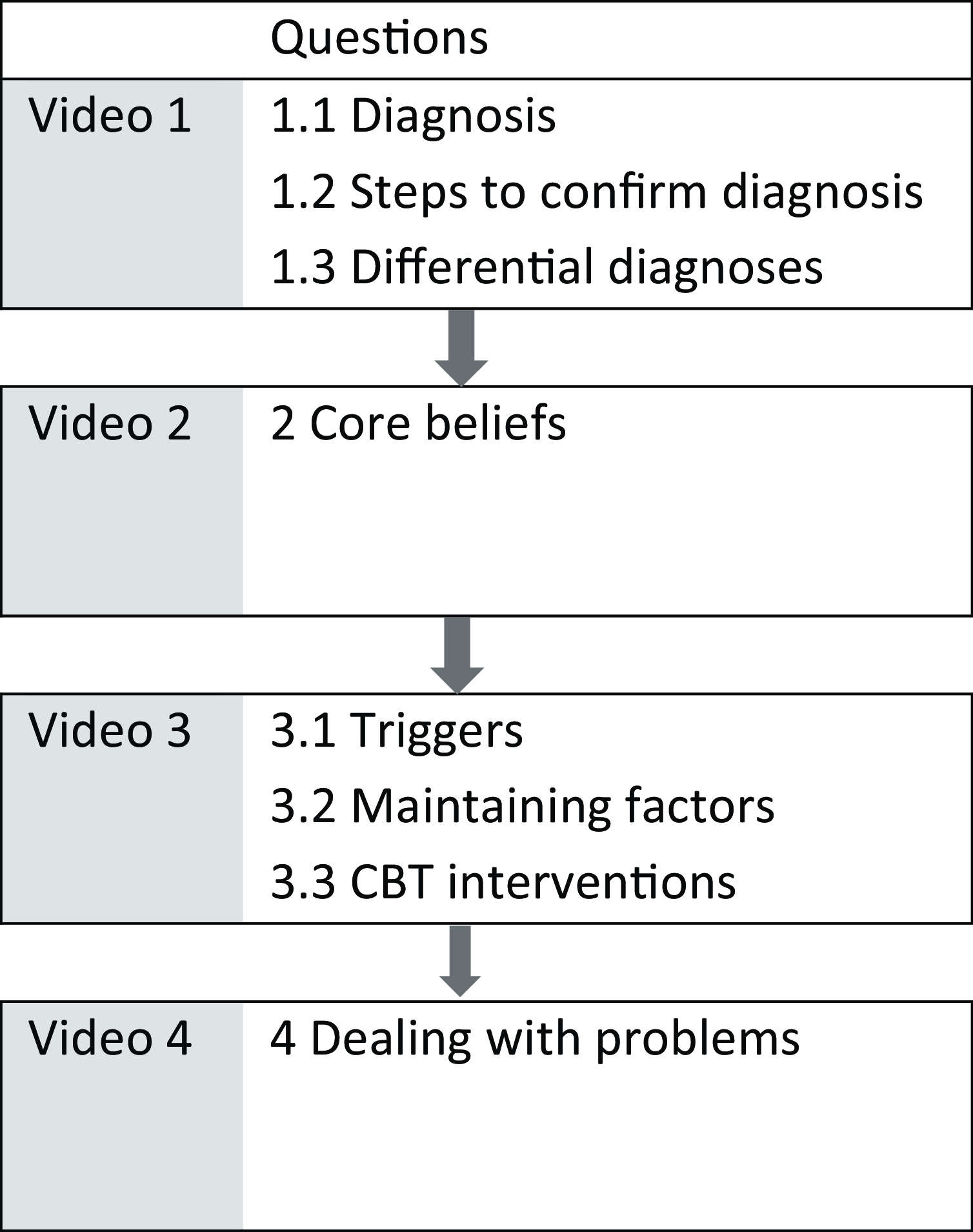

As a result of the construction process, the final Pro CliPs Task consists of a case vignette presented in four brief videos and eight open-ended questions pertaining to each case vignette (see Fig. 1). Each video lasts approximately half a minute (M=28.11 s, SD=10.42 s). In total, we developed seven different case vignettes covering a spectrum of the most prevalent mental disorders (e.g. depression, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder). For assessment purposes, we recommend to use one of the provided seven case vignettes. The completion of a single case vignette requires approximately 10–15 minutes. Once participants have answered all eight questions of one case vignette, their responses are then coded in accordance with the provided coding sheet. Subsequently, a sum score can be calculated (up to 3 points per question, with a maximum total score of 24 per case vignette). This sum score represents the primary outcome of the Pro CliPs Task. An example video vignette and the pertaining questions of the Pro CliPs Task are available in English (see Paunov, Reference Paunov2024). The German version of the Pro CliPs Task, including the coding system, is available upon request from the first author.

Figure 1. Schematic structure of the Pro CliPs Task. Every case vignette consists of four videos. The structure and questions apply to all case vignettes.

The Pro CliPs Task assesses procedural knowledge in clinical psychology and is grounded in the trans-theoretical, generic ‘5 Ps model’, yet it also encompasses CBT-specific aspects, such as core beliefs and CBT interventions.

Feasibility study

The principal objective of the feasibility study was to examine the item characteristics and inter-rater reliability of the Pro CliPs Task in a student sample. In addition, the general applicability of the Pro CliPs Task and the authenticity of the case vignettes were assessed using the Authenticity of Patient Demonstrations Scale (APD; Ay-Bryson et al., Reference Ay-Bryson, Weck and Kühne2022). We hypothesised good inter-rater reliability (ICC≥.75; following Koo and Li, Reference Koo and Li2016) and adequate item characteristics (item difficulty Pi .20 < Pi < .80, item variance σ2>.16, item discrimination r>.30; following Moosbrugger and Kelava, Reference Moosbrugger and Kelava2012). We expected high applicability ratings and all case vignettes to be considered authentic (M=2.0 on the APD, ranging from 0 to 3). A moderate correlation between the Pro CliPs Task and the participants’ level of education was expected (r=.30 to .50), with Master’s students achieving significantly higher sum scores than Bachelor’s students (p<.05).

Statistical analysis and ratings

Following power analysis for the inter-rater reliability, we aimed at a sample size of n=62 participants answering two complete vignettes (minimum acceptable ICC=.75, power 0.80, based on data of two raters). We computed intraclass correlation coefficients, psychometric indices, Pearson correlation coefficients and a t-test to address our hypotheses. All analyses were performed using RStudio version 2023.12.1.402 (R Core Team, 2024). Two independent raters were trained in the use of the coding system. Their training lasted 10 hours. The raters worked independently from one another and convened after completing the ratings for one case vignette to discuss their ratings. The ratings were not changed after discussion. Both raters were female and one was the first author and a psychotherapist in training. The second rater was a Master’s student in clinical psychology.

Participants and procedure

Sixty-six Bachelor’s and Master’s psychology students participated in the feasibility study. Their mean age was M=25.75 years (SD=5.02). The majority was female (77%) and Bachelor’s psychology students (71%). They were recruited through the university’s participant pool for the participation in scientific studies. The students participated in a 1-hour online study and received course credit for their participation. The university’s survey platform was used, and participation was anonymous and voluntary. All participants gave informed consent prior to study completion. Each participant saw two out of seven case vignettes in a randomised balanced order. Based on the results of the feasibility study, minor changes were made to the wording of one question.

Evaluation study

The principal objective of the evaluation study was to examine the validity of the Pro CliPs Task. We sought to examine the association between procedural knowledge, assessed with the Pro CliPs Task and (a) declarative knowledge, as assessed by 15 true/false statements derived from the German psychotherapy licensure test (convergent validity), (b) self-reported grades in clinical psychology (criterion validity), and (c) the reflective system, as assessed by therapeutic self-efficacy with the Counsellor Activity Self-Efficacy Scales Revised-Basic Skill (CASES-R; Hunsmann et al., Reference Hunsmann, Ay-Bryson, Kobs, Behrend, Weck, Knigge and Kühne2024), which consists of 15 items on a scale from 0 to 9. Moderate correlations with declarative knowledge, self-reported grades in clinical psychology and therapeutic self-efficacy were expected (r=.30 to .50). We also compared the Pro CliPs Task sum scores of psychology students with those of postgraduate psychotherapy trainees (having obtained a Master’s degree in psychology) in order to ascertain whether the Pro CliPs Task was sensitive to different training levels. We hypothesised that postgraduate psychotherapy trainees would achieve higher sum scores in the Pro CliPs Task than psychology students (p<.05, d=.50 to .80).

Statistical analysis and ratings

Following power analysis for the group comparison, we aimed at a sample size of N=128 (n=64 in each group; d=.50, power .80, α=.05) with each participant answering one complete vignette. To address the hypotheses, a t-test and Pearson correlation coefficients were computed. The answers to the Pro CliPs Task were rated by the first author. As inter-rater reliability had been established in the feasibility study, this rater coded all the data and 25% of the answers were then coded by a second rater. The raters were blinded to group affiliation, and did not change their ratings after discussion.

Participants and procedure

One hundred thirty-three individuals participated in the evaluation study. In the student sample (n=68), the mean age was M=25.43 (SD=5.10). The majority was female (78%) and Bachelor’s students (69%). In the trainee sample (n=65), the mean age was M=31.94 (SD=6.76). Trainees were mostly female (80%) and had been in postgraduate psychotherapy training for M=3.29 years (SD=1.63). The majority were training in CBT (89%), and some were training in psychodynamic (6%) or systemic (5%) therapy. Participants were recruited via email lists and newsletters across German universities for the student sample and across institutions offering postgraduate psychotherapy training for the trainee sample. Participation was anonymous, voluntary, and took approximately 30 minutes. All participants provided informed consent prior to study completion.

Results

Feasibility study

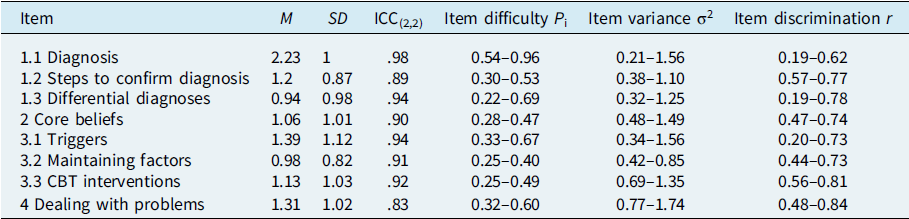

The average inter-rater reliability for the coded answers of the Pro CliPs Task was considered excellent for the vignette sum scores (ICC(2,2)=0.97–0.99) and good to excellent for the single items across vignettes (ICC(2,2)=.83–.98). The mean score across all vignettes was M=10.27 (SD=4.98, range 1.5–21.5). Descriptive results, ICCs and item characteristics for all items across case vignettes of the Pro CliPs Task are displayed in Table 2. Item characteristics were largely within the expected range, with a few exceptions. These included high item difficulty values for question 1.1 regarding the diagnosis in two case vignettes and low item discrimination values for five different questions in different case vignettes (see Supplementary material for the results on the case vignette-specific level). The correlation between sum scores in one vignette and another was high (r=.78).

Table 2. Item characteristics of all questions across case vignettes in the feasibility study

n=132 per item/question in the Pro Clips Task. Ratings on a scale from 0 to 3. Ranges across all case vignettes are reported for the psychometric indices.

In accordance with our hypothesis, the case vignette sum scores were also highly correlated with participants’ level of education (r=.60), indicating that more advanced students achieved higher Pro CliPs Task sum scores. The mean Pro CliPs sum score for Master’s students (M=14.95, SD=4.1) was significantly higher than that for Bachelor’s students (M=8.37, SD=3.97; t 64=–6.03, p<.001, d=1.6).

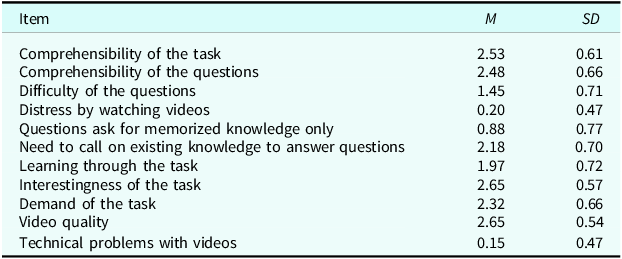

In accordance with our hypothesis, the case vignettes were perceived as authentic (M=2.25, SD=0.47; on a scale from 0 to 3) and the applicability of the Pro CliPs Task was rated as excellent (see Table 3).

Table 3. Applicability of the Pro CliPs Task as rated in the feasibility study

n=66. Ratings on a scale from 0 to 3.

Evaluation study

For the Pro CliPs Task, the mean score across all vignettes was M=10.06 (SD=4.22, range 1–19) in the student sample and M=16.03 (SD=3.54, range 5–24) in the trainee sample, with significantly higher scores in the trainee group (t 131=–8.83, p<.001, d=1.5). In the overall sample, there was a strong positive correlation between procedural knowledge and both declarative knowledge (r=.55) and therapeutic self-efficacy (r=.53). Additionally, there was a moderately negative correlation between self-reported grades in clinical psychology and procedural knowledge (r=–.34), indicating that better grades were associated with higher sum scores. The results were therefore in accordance with our hypotheses. Furthermore, the inter-rater reliability was computed for 25% of the data based on two case vignettes and considered excellent (ICC(2,2)=.93).

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to develop and evaluate a measure of procedural knowledge in clinical psychology. We thus constructed the Pro CliPs Task, consisting of a case vignette presented in four brief videos, and eight open-ended questions pertaining to the case vignette. In total, the Pro CliPs Task provides seven different case vignettes. We evaluated the Pro CliPs Task in a feasibility study regarding its item characteristics, inter-rater reliability, applicability and authenticity of the Pro CliPs Task. In addition, we examined its validity in a second study.

Overall, the Pro CliPs Task demonstrated adequate psychometric characteristics. With two exceptions; all item difficulty values were within the expected range of .20 < Pi < .80. Regarding item discrimination, the values for five different questions in different case vignettes were lower than recommended, yet still acceptable. Furthermore, all questions were deemed to be content-theoretically relevant for the measure and were thus not excluded following the recommendations by Moosbrugger and Kelava (Reference Moosbrugger and Kelava2012). It is noteworthy that none of the seven case vignettes nor any of the open-ended questions proved problematic regarding their psychometric data. The inter-rater reliability for the coded answers was excellent for the vignette sum scores and good to excellent for the single items across vignettes. In comparison to similar measures (e.g. Eells et al., Reference Eells, Kendjelic and Lucas1998; Myles and Milne, Reference Myles and Milne2004) and instruments of competence in which observed therapist competence is rated (such as the CTS; Young and Beck, Reference Young and Beck1980), the results are particularly encouraging. As inter-rater reliability was established based on the ratings of the first author and a trained student, these results indicate that with proper training and supervision individuals with less experience can also assess the Pro CliPs Task. The case vignettes were judged highly authentic and the applicability of the task was generally considered excellent. These are important aspects for the resource-efficient and realistic assessment of clinical competencies in general (Muse et al., Reference Muse, Kennerley and McManus2022; Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013).

The evaluation study yielded evidence supporting the instrument’s validity. The Pro CliPs Task was able to effectively differentiate between varying levels of study as well as between psychology students and psychotherapy trainees. Furthermore, it was strongly associated with declarative knowledge in clinical psychology and with therapeutic self-efficacy, as well as moderately correlated with grades in clinical psychology. The evidence for its convergent and criterion validity is therefore robust, and the Pro CliPs Task may be considered an easy-to-use, additional measure alongside more comprehensive rating scales, such as the Cognitive Therapy Scale (Young and Beck, Reference Young and Beck1980). In terms of the DPR model (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006), we investigated the basic relationships between the procedural system and the declarative and reflective systems. The results also indicate an improvement in procedural abilities over the course of training. This is consistent with previous research indicating that declarative knowledge and case formulation skills are dependent on psychotherapists’ experience (Eells and Lombart, Reference Eells and Lombart2003; Eells et al., Reference Eells, Lombart, Salsman, Kendjelic, Schneiderman and Lucas2011) and may improve over the course of training (Evers et al., Reference Evers, Schröder-Pfeifer, Möller and Taubner2022) in a manner analogous to the growth of reflexive capacity over the course of therapeutic development (Campbell-Lee et al., Reference Campbell-Lee, Barton and Armstrong2024).

Limitations and future research

Firstly, it should be noted that the sampling of participants in our studies was not entirely random. It would be beneficial for further studies to explore the generalisability of the Pro CliPs Task to other populations, such as expert clinicians, or in different settings, such as before and after interventions focusing on the improvement of case conceptualisation competences. Secondly, although we conducted two studies that were consistent with the previous power analyses, it would be beneficial to include more diverse samples for further evaluation. Thirdly, as our primary objective was the preliminary evaluation of the Pro CliPs Task, the study design was not suitable for investigating the relationships between declarative, procedural and reflective systems in greater detail. Although declarative knowledge is frequently regarded as a pre-requisite for procedural and reflective skills (Heinze et al., Reference Heinze, Weck, Maaß and Kühne2023; Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013), a more comprehensive investigation of the inter-relationships between the different competence systems is warranted. Further research is also needed to address the lack of information on divergent validity of the Pro CliPs Task. Similarly, further research is required to examine the convergent validity with other measures of procedural knowledge. As such, case conceptualisation is one approach to operationalising procedural knowledge and other dimensions of this concept (i.e. standardised role-plays, real therapist–patient interactions) should also be investigated in order to gain a more thorough understanding of the role of procedural knowledge in competence development. Further research may also compare the Pro CliPs Task with other measures of case conceptualisation, such as the Collaborative Case Conceptualisation Rating Scale (Padesky et al., Reference Padesky, Kuyken and Dudley2011). Fourthly, the Pro CliPs Task has a focus on CBT and in the evaluation study, the trainees were predominantly from a CBT background. This limits its suitability for assessing clinical knowledge in psychodynamic or systemic therapy orientations. Nevertheless, the instrument could be adapted to assess other psychotherapy orientations. Finally, it should be noted that the high inter-rater reliability is also a result of rater training and the fact that one rater was the primary developer of the instrument. As previous research has demonstrated (Paunov et al., Reference Paunov, Weck, Heinze, Maaß and Kühne2024a), inter-rater reliability is likely to be contingent upon rater training and the provision of ongoing supervision. Consequently, researchers intending to utilise the measure in future studies should ensure that rater training is provided at the beginning and throughout the rating process.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Pro CliPs Task is a psychometrically sound measure of procedural clinical knowledge. This study provides psychometric and reliability data that are rarely reported in competency research (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Becker-Haimes and Kendall2020). The Pro CliPs Task requires approximately 10–15 minutes for most respondents to complete one case vignette, making it a time-efficient assessment tool. As there are few instruments for the reliable assessment of procedural knowledge, the Pro CliPs Task represents a valuable contribution to the measurement of psychotherapeutic competencies. The Pro CliPs Task is a pragmatic tool that can be utilised in research and teaching to assess and improve procedural knowledge in clinical psychology, particularly in CBT. Our findings indicate excellent psychometric properties and reliability, strong convergent and criterion validity, as well as applicability for measuring clinical procedural knowledge with the Pro CliPs Task. Consequently, it has the potential to serve as a comparatively brief and reliable competence measure.

Key practice points

-

(1) The Pro CliPs Task is a brief measure of procedural knowledge in clinical psychology. It consists of a case vignette presented in four brief videos, and eight open-ended questions pertaining to the case vignette. In total, the Pro CliPs Task provides seven different case vignettes, each exhibiting comparable psychometric properties. For assessment purposes, we recommend using one of the seven case vignettes.

-

(2) The Pro CliPs Task can be used in research, training and teaching contexts. It requires respondents 10–15 minutes to answer one case vignette, thus making it a time-efficient assessment tool.

-

(3) The evidence for the role of procedural knowledge in the development of therapeutic competence remains limited. However, theoretical frameworks such as the DPR model offer a foundation for understanding its importance in translating declarative knowledge into practice.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X2500011X

Data availability statement

The Pro CliPs Task materials are available on the Open Science Framework (osf.io/f6k52). Further information and data are available upon request from the first author.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Tatjana Paunov: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (lead); Florian Weck: Conceptualization (supporting), Resources (lead), Supervision (equal), Writing - original draft (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Franziska Kühne: Conceptualization (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing - original draft (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

This study was pre-registered, and the study protocol was approved by the university’s ethics committee (reference number 55/2023). The study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.