Introduction

The purpose of an extended training in a healthcare profession has been said to be to ensure safe and effective practice (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Snell, Cate, Holmboe, Carraccio, Swing, Harris, Glasgow, Campbell, Dath, Harden, Iobst, Long, Mungroo, Richardson, Sherbino, Silver, Taber, Talbot and Harris2010), which in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) translates to training the workforce of competent practitioners that Clark (Reference Clark, Whittington and Grey2013) states is necessary to deliver CBT as an evidence-based psychological therapy. Rakovshik and McManus (Reference Rakovshik and McManus2010) concluded that more extensive CBT training produces increased therapist competence and better patient outcomes. However, Jenkins et al. (Reference Jenkins, Waddington, Thomas and Hare2018) argue that the research focus on measurable training outcomes leaves gaps in understanding trainees’ experiences, which, if explored, could contribute to a better understanding of the impact of training, and potentially improvements to it (Bennett-Levy and Beedie, Reference Bennett-Levy and Beedie2007). Despite the addition of recent qualitative research on trainee experiences using either convenience samples of reflective academic work (e.g. Presley and Jones, Reference Presley and Jones2024; Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020) or online questionnaires (Presley, Reference Presley2023; Roscoe et al., Reference Roscoe, Bates and Blackley2022; Roscoe and Wilbraham, Reference Roscoe and Wilbraham2024), this gap persists. No recent research was identified that interviewed UK-based trainees and recently qualified practitioners. The following sections summarise and critique existing literature on how CBT training is experienced and its perceived contribution to developing competence.

Defining and assessing competence in CBT

Competence has been described as a foundational developmental need to acquire ‘skills for acting in and on the world’ (Dweck, Reference Dweck2017; p. 693) that is linked to self-esteem and wellbeing (Deci and Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000; Eccles and Wigfield, Reference Eccles and Wigfield2002). The acquisition of competence has been described as at the core of achievement motivation (Elliot and Dweck, Reference Elliot, Dweck, Elliot and Dweck2005). In the healthcare professions, competence is understood as both a boundary marker distinguishing competence, partial competence (dyscompetence), and incompetence, and a professional attribute consisting of competencies that enable practitioners to select appropriate interventions and techniques and deliver them skilfully for the specific client and therapeutic situation (Dennhag et al., Reference Dennhag, Gibbons, Barber, Gallop and Crits-Christoph2012; Frank et al., Reference Frank, Snell, Cate, Holmboe, Carraccio, Swing, Harris, Glasgow, Campbell, Dath, Harden, Iobst, Long, Mungroo, Richardson, Sherbino, Silver, Taber, Talbot and Harris2010). Progression of competence takes place when practitioners move from being novice practitioners, characterised by rigid adherence to rules and limited situational perception, to mastery that reflects performance at a higher level (Tracey et al., Reference Tracey, Wampold, Lichtenberg and Goodyear2014), where expertise is intuitive, flexible, and responsive to context (Dreyfus and Dreyfus, Reference Dreyfus and Dreyfus1980; Dreyfus and Dreyfus, Reference Dreyfus and Dreyfus2005; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Spiegel, Hoffman, Kivlighan and Gelso2017; Rousse and Dreyfus, Reference Rousse, Dreyfus, Silva Mangiante and Peno2021). The development of skilfulness from ‘mere’ competence, through proficiency, to expertise aligns with foundational literature on self-regulated learning processes, where increasing metacognitive awareness, self-efficacy, and adaptive expertise enable practitioners to refine and internalise their skills (Zimmerman and Schunk, Reference Zimmerman and Schunk2001).

James et al. (Reference James, Blackburn, Milne and Reichfelt2001) describe competence in CBT as an acquired skill influenced by situational factors such as training and experience, encompassing adherence to the cognitive model, technical proficiency in CBT techniques, interpersonal effectiveness, and the capacity to apply knowledge and skills flexibly and sensitively in practice. The earliest description of CBT’s component competencies was included in Beck et al.’s (Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979) disorder-specific Cognitive Therapy of Depression comprising an eclectic medley of behavioural and cognitive techniques bound together by the cognitive rationale and delivered using generic psychotherapeutic skills (Beck, Reference Beck1976; Beck and Haigh, Reference Beck and Haigh2014). Beck et al.’s competencies appear to form the basis of Roth and Pilling’s (Reference Roth and Pilling2007) competency framework for CBT for anxiety and depression which was derived by reverse engineering manuals of ‘exemplar’ CBT treatment trials (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2008) that were likely to have been versions of Beck’s CBT (no information was found describing the types of CBT utilised in these trials) which potentially creates circularity. The Roth and Pilling framework consists of five categories: generic therapeutic competencies, basic CBT competencies, CBT-specific techniques, problem-focused competencies, and the metacompetencies that enable therapists to adapt their approach to individual clients. Roth and Pilling (Reference Roth and Pilling2008) point out that their framework does not distinguish between the ‘wheat’ and the ‘chaff’ of skills that are implicated in change processes and those that are redundant. This admission suggests that there are questions as to which competencies are necessary and/or sufficient, and which are perhaps institutionally reified habits of practice.

Although a modified version of Beck’s CBT is thought to be the most practised version of CBT in the UK (Trower, Reference Trower, Dryden and Branch2012) we would argue that defining CBT simply in terms of Beck’s approach is unhelpful because CBT encompasses a range of cognitive, behavioural, and cognitive-behavioural psychotherapies, each with their theoretical base and technical requirements (Dobson and Dozois, Reference Dobson, Dozois and Dobson2010). The diversity of CBT approaches combined with the continuously evolving nature of CBT and the limited understanding of its mode of action (Bruijniks et al., Reference Bruijniks, DeRubeis, Hollon and Huibers2019), means that establishing a consensus about what constitutes effective and competent CBT practice remains challenging (Campbell-Lee et al., Reference Campbell-Lee, Barton and Armstrong2024; Muse et al., Reference Muse, Kennerley and McManus2022). Furthermore, while CBT competence has been traditionally defined by frameworks such as Roth and Pilling, and therapeutic ‘drift’ is discouraged (Waller and Turner, Reference Waller and Turner2016), rigid adherence does not necessarily equate to better outcomes and may even limit effective practice (Rapley and Loades, Reference Rapley and Loades2019). There is increasing emphasis on the importance of metacompetencies for individualised, flexible practice that allows therapists to adapt interventions to the unique needs of their clients while maintaining fidelity to core therapeutic principles (Hogue et al., Reference Hogue, Henderson, Dauber, Barajas, Fried and Liddle2008).

Assessing competence in CBT training typically involves a combination of academic assignments (e.g. essays, case reports) and ratings of clinical practice using standardised scales (Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013). The Cognitive Therapy Scale-Revised (CTS-R: Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Claydon, Blackburn, James and Sheikh2001) is commonly used in the disorder-specific NHS Talking Therapies (formerly Improving Access to Psychological Therapies) training programs (Clark, Reference Clark2011). This creates an anomaly; while many generic CBT competencies provide the foundation for disorder-specific approaches (Newman, Reference Newman2013), the CTS-R is not designed to assess distinctive disorder-specific skills (Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013). We would argue that the CTS-R also fails to assess how competence might be demonstrated across a course of treatment, potentially a more useful metric than the fine-grained analysis of a single session. Furthermore, each item is weighted equivalently, so the scale does not differentiate between the skills that contribute most (or least) to outcomes. More generally, some authors state that the evidence for using competence measures is limited (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Liese and Abrams2003; Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013; Wampold and Imel, Reference Wampold and Imel2015). Adequate inter-rater reliability has been difficult to establish (Fairburn and Cooper, Reference Fairburn and Cooper2011), and the items in competence scales are potentially not attuned to measuring metacompetencies (Campbell-Lee et al., Reference Campbell-Lee, Barton and Armstrong2024). Nonetheless, it is mandated in the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies’ (BABCP) core curriculum to use a measure of competence as part of a BABCP-accredited CBT training (British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies, 2021). Given the contested nature of competence and its measurement, and that the purpose of training is to develop competence, it is potentially useful to understand better how trainees experience training as they seek to develop competence.

Trainee experiences of training in CBT

There is considerable evidence that training in psychotherapies such as CBT can be highly demanding and stressful (e.g. Duryee et al., Reference Duryee, Brymer and Gold1996; Reiser and Milne, Reference Reiser and Milne2013; Skovholt and Rønnestad, Reference Skovholt and Rønnestad2003). A spoof paper on a fictitious disorder named Cognitive Therapy Training Stress Disorder illuminates the widespread perception that CBT training can be highly challenging (Worthless et al., Reference Worthless, Competent and Lemonde-Terrible2002). While NHS England commissioned programmes are not the only CBT training in the UK, they train the greatest number of practitioners. Owen et al. (Reference Owen, Crouch-Read, Smith and Fisher2021) report that trainees on those courses may experience levels of stress and burnout that are higher than their qualified peers and among the higher end of healthcare professionals more generally, which the authors attribute to the challenge of fulfilling concurrent roles as mental health professionals and university students. It is also possible that the highly compressed nature of NHS Talking Therapies training, which is mostly full-time over 12 months, creates further pressure.

Training in CBT has been described as a professional role transition that can be experienced as deskilling (Reiser and Milne, Reference Reiser and Milne2013) as well as causing a loss of identity, support, role familiarity and workplace seniority (Roscoe and Wilbraham, Reference Roscoe and Wilbraham2024). Orienting to CBT’s values and practice norms as one changes profession can also be challenging and this might be manifested in differing experiences of gaining competence for mental health nurses, counsellors, and non-core profession trainees (Wilcockson, Reference Wilcockson2020). Wolff and Auckenthaler (Reference Wolff and Auckenthaler2014) described CBT trainees as ‘constructive jugglers’ defining and redefining CBT throughout training as part of their professional identity development, a process that seemed more straightforward for those with a good epistemological fit to CBT. Roscoe et al. (Reference Roscoe, Bates and Blackley2022) described professional transition in terms of competing former and developing professional selves. If training is frequently experienced as highly demanding, then it is worth asking how it is perceived to contribute to the development of competence.

The acquisition of competence

Models of the acquisition of competence in healthcare professions (e.g. Benner, Reference Benner1984; Dreyfus and Dreyfus, Reference Dreyfus and Dreyfus1980; Dreyfus and Dreyfus, Reference Dreyfus and Dreyfus2005; Eraut, Reference Eraut1994) and in psychological therapy (e.g. Rodolfa et al., Reference Rodolfa, Bent, Eisman, Nelson, Rehm and Ritchie2005; Sperry, Reference Sperry2010) describe it as a progressive journey from foundational knowledge to advanced expertise through structured learning and clinical practice. Rønnestad and Skovholt’s (Reference Rønnestad and Skovholt2013) cyclical trajectories model describes a process of professional competence development through progressively mastering the challenges of training in psychotherapy but might not apply to CBT training. Bennett-Levy’s (Reference Bennett-Levy2006) Declarative-Procedural-Reflective (DPR) model focuses on the acquisition of competence in CBT in terms of developing CBT-relevant declarative knowledge (knowing ‘that’), procedural knowledge (knowing ‘how’), and reflective skills to facilitate metacompetence and continuing professional development. However, there is a risk that the DPR model, which assumes an outdated information-processing model of cognition (Piccinini and Scarantino, Reference Piccinini and Scarantino2011) fails to accommodate contemporary constructivist definitions of learning (e.g. Chuang, Reference Chuang2021; De Corte, Reference De Corte2012), or social cognitive theories of the reciprocal interactions between personal processes, behaviour, and context (Bandura, Reference Bandura1986). The DPR model is also somewhat historically decontextualised in that it makes little reference to Dewey’s (Reference Dewey and Dewey1910, Reference Dewey1933) foundational work on the role of reflection in learning and Lewin’s (Reference Lewin1946) work on action research that were highly influential on Kolb’s (Reference Kolb1984) experiential learning model which provides the foundation for the understanding of reflection in CBT (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock and Davis2009b). As a result, the DPR model potentially misses the broader philosophical implications of reflection as a dynamic, often dialogical process that occurs in specific cultural contexts.

Some research has found that trainees’ self-perception of competence and self-identified theoretical orientation is moderated by level of engagement, itself influenced by quantity of training, use of active learning strategies, trainee enthusiasm, and expectations of benefit (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Waddington, Thomas and Hare2018). Research also indicates that outcomes may be moderated by use of supervision. For example, Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Kellett, King and Keating2012) found that supervision was the most important factor in supporting role transition especially when feeling deskilled, and Rakovshik and McManus (Reference Rakovshik and McManus2013) found that trainees thought that supervision had a greater influence on their competence than clinical instruction. Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Davies and Weatherhead2016) highlight how supervision provides both feedback and opportunity for reflection which facilitates the development of metacognitive awareness in trainees as they learn to attune to key therapeutic processes. However, there are sparse data on the mediating role of specific supervision methods or models. Milne’s (Reference Milne2009) evidence-based clinical supervision suggests that structured supervision, incorporating experiential learning and systematic feedback, enhances skill acquisition by promoting active reflection and goal-directed practice. Given that imitation is a primary learning tool even in adults (McGuigan et al., Reference McGuigan, Makinson and Whiten2011), group supervision and supervisor modelling are likely to lead to exposure to a variety of approaches to skill development and sociocultural learning (Tomasello, Reference Tomasello1999).

Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009a) proposed that different methods of instruction were likely to influence different domains of knowledge and skill acquisition, for example skills in reflection could be enhanced by self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR). Subsequently, SP/SR has been found to offer significant benefits, including increased empathy, a more profound self-awareness, and strengthened adherence to CBT principles (Gale and Schröder, Reference Gale and Schröder2014). Haarhoff et al. (Reference Haarhoff, Flett and Gibson2011) tentatively concluded that SP/SR enhanced competence in case conceptualisation, theoretical understanding of the CBT model, self-awareness, empathy, conceptualisation of the therapeutic relationship, and adaptation of clinical interventions and practice. However, the benefits of SP/SR may depend both on level of engagement with SP/SR tasks (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014), and engaging both personal self and therapist self (Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014). Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones (Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018) described a model for the role of personal practice to link personal and professional selves across a ‘reflective bridge’, and Presley and Jones (Reference Presley and Jones2024) claimed that SP/SR as a personal practice can help trainees in ‘crossing’ the reflective bridge to explore their identity as a therapist, examine aspects of themselves that may be impeding the therapeutic process, and pursue both personal and professional growth.

The perceived benefits of SP/SR and supervision might also relate to the importance of mobilising emotion as part of learning (Lombardo et al., Reference Lombardo, Milne and Proctor2009), although when affect is too great it might lead to emotional avoidance that could have a harmful impact on learning (Presley et al., Reference Presley, Jones and Marczak2023). Personal characteristics, such as sensitivity to receiving feedback, might also affect the acquisition of competence (Delgadillo et al., Reference Delgadillo, Nissen-Lie, De Jong, Schröder and Barkham2024). There is also evidence that some CBT skills may also be more strongly linked to outcomes than others. For example, Braun et al. (Reference Braun, Strunk, Sasso and Cooper2015) found that Socratic questioning significantly predicted session-to-session symptom change across early sessions of CBT for depression, a skill that Roscoe et al. (Reference Roscoe, Bates and Blackley2022) found was particularly tricky for trainees to master.

Thus, while training is thought to make a significant contribution to competence, despite being highly demanding, it raises the question of how trainees understand the relationship between the experience of training and outcomes, the resources they need to learn, and how they acquire competence under those circumstances. Given the difficulties researchers have in agreeing a clear working definition of competence (Campbell-Lee et al., Reference Campbell-Lee, Barton and Armstrong2024; Muse et al., Reference Muse, Kennerley and McManus2022) and the questionable appropriateness of assessment measures (Muse and McManus, Reference Muse and McManus2013), it would be useful to ask what novice CBT therapists see as competence during and recently after training. This research seeks to address those questions through an exploration of the training experience and to consider practical applications to improve CBT training.

Aims of the research and researcher reflexivity

Lazard and McAvoy (Reference Lazard and McAvoy2020) state that reflexivity is a fundamental expectation of qualitative work in psychology to unpack the ‘partial, positioned and affective perspectives we bring to the research’ (p. 159) so that the influence of the researchers’ values, attitudes, and experience on the choice of topic can be more easily seen (Patnaik, Reference Patnaik2013). The first author’s methodological philosophy is based on a critical realist social ontology (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2012; Searle, Reference Searle2006) that believes participants’ experiences reflect real events and conditions in their lives (e.g. actual challenges in training). It is epistemologically pragmatist in that it assumes that ontology becomes known, albeit fallibly, through an iterative process of inquiry (Morgan, Reference Morgan2014) with the goal of improvements in practice (Dewey, Reference Dewey1929), that is, prudential wisdom, or phrōnesis (Kristjánsson et al., Reference Kristjánsson, Fowers, Darnell and Pollard2021).

The use of a reflexive qualitative methodology is consistent with the author’s background as a counselling psychologist (Rennie, Reference Rennie1994), and a critical realist/pragmatist approach with his practice as a social cognitive CBT psychotherapist, supervisor, and tutor. The first author’s intellectual interests have focused on developing theoretical models that find process commonalties between domains, as in the cloverleaf model (Grimmer, Reference Grimmer2022). His conceptualisation of the process of qualitative research mirrors both the therapeutic process of CBT and the acquisition of knowledge and skills in CBT; each is conceived of as forms of learning from reflection on situated experience that have their foundation in Dewey’s (Reference Dewey1933) conceptualisation of inquiry and its influence on Schön’s (Reference Schön1992) concept of the reflective practitioner .

More concretely, the research reported in this paper was inspired in part by the first author’s continuing reflection on the limits of metacompetent flexibility (Whittington and Grey, Reference Whittington, Grey, Whittington and Grey2014). Having had extensive experience of working in diverse contexts, including NHS Talking Therapies, part of the first author’s ‘felt difficulty’ (Dewey, Reference Dewey and Dewey1910) was formulating how diverse CBT perspectives could be integrated into a coherent, contextually sensitive approach, especially when trying to enhance the professional development of others. Collaborative discourse with practitioners at various points in their professional lifespan might shed light on that question by exploring the perceptions of professional development processes that lead to competence. By beginning with those at the start of their therapeutic career in CBT, the research aligns with Bennett-Levy and Beedie’s (Reference Bennett-Levy and Beedie2007) suggestion that exploring trainee perspectives could provide relevant insights. Most prior research has focused on discrete aspects of training such as acquisition of a specific skill (Roscoe et al., Reference Roscoe, Bates and Blackley2022), the impact of SP/SR on the personal and professional selves (Presley and Jones, Reference Presley and Jones2024), or motivation to train (Roscoe and Wilbraham, Reference Roscoe and Wilbraham2024), with no studies identified that explored the training experience more broadly including how trainee and recently qualified CBT practitioners understand the contribution of training to the development of competence. The specific research aims were therefore:

-

(1) To understand better the motivation to train and the experience of training and its outcomes for trainee and recently qualified UK CBT practitioners.

-

(2) To explore what competence in CBT means to participants and how they evaluate their competence.

-

(3) To describe participants’ perceptions of how training has influenced their own development of competence including the role of the personal and professional selves.

-

(4) To consider practical implications for CBT training.

Method

Participants

As an exploratory study, sample size was determined by balancing practical constraints with the need for a data corpus that would support robust conclusions, while pursuing maximum variation sampling (Patton, Reference Patton2002). Given a 12-month timeframe from ethical approval to presentation of findings, a sample size of 15 participants was deemed optimal to capture sufficient variation to achieve theoretical sufficiency (Dey, Reference Dey1999) and conceptual depth (Nelson, Reference Nelson2017), without focusing on data saturation, a concept that is contested in reflexive thematic analysis (RTA: Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2022) and difficult to operationalise (Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Sim, Kingstone, Baker, Waterfield, Bartlam, Burroughs and Jinks2018). The sample size also aligns with the relative homogeneity of the target participant group, the study’s focus, the intended analysis, and with recommendations for qualitative research sample sizes (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013; Guest et al., Reference Guest, Bunce and Johnson2006).

Eligible participants were UK-based CBT practitioners who were either currently in training on a Level 2 BABCP-accredited course or had qualified from one within the previous two years. Current experience of training was predicted to provide in vivo insights into training. For those who had completed training, it was thought that there would be sufficient distance from training to reflect on it, while still being sufficiently recent to provide relevant, easily recallable insights. Although experiences might vary between participants currently in training and those who have completed training, it was reasoned that such differences, if present, could offer additional theoretical insights. The possibility that participants in early stages of training might not reasonably be expected to have formed theoretically important opinions on their training to date and its impact on the meaning of competence in CBT was considered and, in the absence of literature to the contrary, it was decided that it would not be wise make a priori assumptions.

While Level 1 BABCP-accredited courses meet many of the BABCP’s Minimum Training Standards (MTS), and all BABCP individually accredited practitioners will meet the MTS, a Level 2 course was believed to provide the comprehensive training required to fulfil all of the MTS (British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies, 2022). By concentrating recruitment on Level 2 training, the study participants would be undertaking a training that is intended to lead to full accreditation, whereas trainees on Level 1 training might not intend to pursue full accreditation, and practitioners who have met Minimum Training Standards through other pathways might be more than two years post-qualification. While this decision might have narrowed the prospective pool of participants, it was thought that this was worthwhile to ensure the research would yield findings that are directly relevant to trainees pursuing full accreditation as CBT practitioners.

The first author carried out the recruitment process. All 42 BABCP Level 2 courses in the UK were contacted and 12 courses agreed to publicise the study. Recently qualified practitioners were recruited via posts on the first author’s LinkedIn page, the BABCP’s research requests website, and informal contacts with recent graduates from various training courses. All recently qualified participants had completed a Level 2 training.

Seventeen individuals volunteered, and 15 were able to participate within the allotted timeframe. No participants were previously known to the researchers. All participants identified as white and female; 14 as British and one as Northern Irish. Participants trained at seven institutions. Six participants trained at a single institution, four at one other, and the remaining five each at a different institution. Course durations were either one year full-time (n=13) or two years part-time (n=2). Eight participants were currently in training and seven had qualified. The shortest duration was 2 months in current training and the longest was 12 months post-qualification from a full-time, one-year training. All participants therefore met the inclusion criteria.

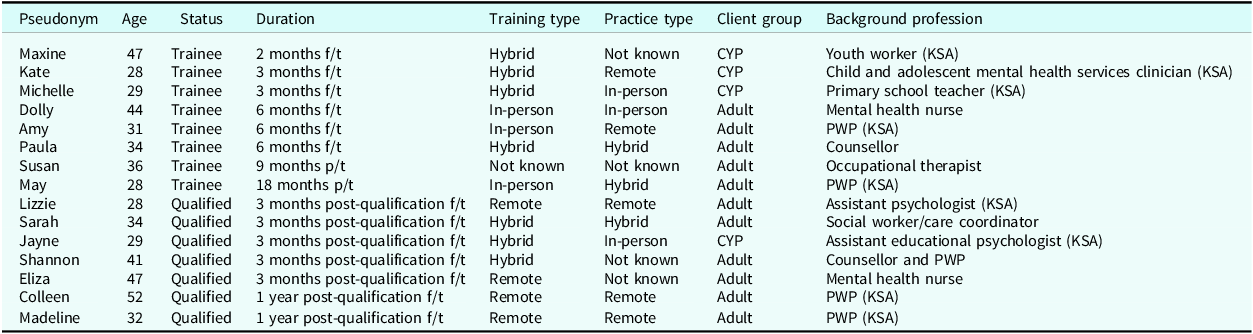

Fourteen participants trained with the NHS Talking Therapies programme. Four trained to deliver CBT to Children and Young People (CYP), and 11 to adults. Although there are differences in training for adult and CYP CBT, the BABCP Core Curriculum (British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies, 2021) specifies the same expected content for both. Six participants had a core profession, while nine followed the KSA (Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes) equivalency route (see Table 1 for an overview of participant characteristics).

Table 1. Participant characteristics

CYP, children and young people; PWP, psychological wellbeing practitioner; KSA, Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes assessment of prior competence in lieu of a core profession; f/t, full-time; p/t, part-time.

Demographic information was gathered at interview when it became evident that all participants were female and white. While this demographic was broadly representative of the gender and ethnicity most common in CBT training in England (NHS Benchmarking Network, 2023), the lack of diversity limited the study’s alignment with maximum variation sampling. Despite resource limitations, efforts were made to recruit participants from under-represented groups, including individuals who were male and/or from racially minoritised communities, including emailing the BABCP’s Anti-Racism Special Interest Group, re-posting recruitment information on LinkedIn, and utilising the first author’s personal contacts. Unfortunately, no additional participants came forward. The implications of this sampling limitation and learning from it are discussed later.

Procedure

Data collection involved two linked tasks: a photo elicitation exercise followed by a semi-structured interview. Interviews are the most common method of qualitative data collection (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013) and aim to elicit participant accounts of experience that document rationales, justifications, and explanations for actions and opinions (Tracy, Reference Tracy2020). The privacy and anonymity of an individual interview was thought appropriate because it enhances the possibility of honest and potentially vulnerable disclosures. Using a semi-structured format allowed conversation to focus on the relevant research topics while creating space for the development of idiosyncratic accounts.

Photo elicitation as part of a semi-structured interview is a widely used technique in qualitative research (Glaw et al., Reference Glaw, Inder, Kable and Hazelton2017; Harper, Reference Harper2002; Kyololo et al., Reference Kyololo, Stevens and Songok2023) and is said to encourage participants to move beyond binary thinking and engage with their experiences in a more nuanced and reflective way (Kara, Reference Kara2015; Mannay, Reference Mannay2016). The contemporary use of photo elicitation has been traced to Collier’s (Reference Collier1957) foundational ethnographic studies (Banks, Reference Banks2007; Harper, Reference Harper2002). Collier suggested that incorporating photographs sharpened memory, reduced areas of misunderstanding, and elicited longer and more comprehensive interviews. Harper (Reference Harper2002) states that photo elicitation leads to a reflective stance on otherwise taken-for-granted aspects of work and community, making photo elicitation particularly suitable for an exploration of lived experience and learning outcomes.

Photo elicitation was also intended to help participants reflect on their training using metaphor as a cognitive tool to embody relatively abstract ideas about the training experience in concrete form that makes them accessible to discuss at interview. Metaphors are frequently employed in CBT as a means of bridging the gap between the concrete and the abstract (Mathieson et al., Reference Mathieson, Jordan, Carter and Stubbe2016; Stott et al., Reference Stott, Mansell, Salkovskis, Lavender and Cartwright-Hatton2010) and can provide valuable insights into personal and professional processes (Sfard, Reference Sfard1998). The image selection process was also intended to act as a visual priming device, so that participants had the opportunity to reflect on the topic before interview and thus provide potentially more considered responses to interview questions.

Prior to interview, participants were contacted by email in which the tasks of the study were described. Participants were offered the opportunity to discuss the research with the first author and most participants did so. The text of the email read:

The study involves two tasks, the first of which is for you in your own time to select a photo or image that represents your training journey. This is merely a way to help you to start thinking about your training experience using the image as a metaphor. Having selected a suitable photo we would then have a 50–60 minute individual interview on Zoom where we can have a semi-structured conversation about what the image represents, your training experience more generally, and what being a competent CBT practitioner means to you.

All participants took part in the photo elicitation exercise. Fourteen participants said they searched online for a suitable image based on key phrases (e.g. a blindfolded dancer), while the fifteenth chose a photo of a quotation that itself employed a metaphor. The semi-structured interview initially focused on the meaning of the selected image to elicit deeper reflections on how training was experienced, followed by (1) further reflections on the experience of training; (2) a personal understanding of competence and how it is evaluated; (3) participants’ perceptions of developmental processes in context; (4) the role of the personal and professional in competence; and (5) advice participants would offer to a prospective trainee. The interview schedule, which was employed freely in a conversational manner, is reproduced in Appendix 1 (Supplementary material). Interviews were carried out over Zoom video call by the first author, who is an experienced interviewer, and ranged from 50 min 21 s to 1 h 22 min 46 s (mean duration = 1 h 6 min 41 s).

Data analysis

Audio was extracted from recordings and pseudonymised participant accounts were transcribed by the first author, who conducted the primary data analysis using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA: Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006; Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2022). Although alternative methods, such as grounded theory (GT) were considered, RTA was selected for its flexibility in supporting theoretically informed interpretations without the extensive resources and methodological commitment required for a full GT approach. In studies with limited resources, RTA avoids the risk of being perceived as ‘GT lite’ (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021).

The analysis process was conducted using TA’s six-phase structure (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) consisting of (1) data familiarisation, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing a report. However, consistent with RTA’s later conceptual and design thinking (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2022; Byrne, Reference Byrne2022) these are better understood as reflexive tasks that interact in a recursive and iterative fashion as the analysis progresses. Data analysis attempted to capture both descriptive and interpretive insights. The first stage, an inductive, data-driven approach, focused on the descriptions and accounts that participants gave across the whole of the interview, including their descriptions and interpretations of chosen images. Images were not analysed separately from participant accounts to remain faithful to their meanings as described.

Line-by-line coding involved extracting segments of text from transcripts, labelling them with a key word or phrase, and organising them into a hierarchical coding tree that drew on the subject domains in the interview schedule. This was conducted by the first author and NVivo 12 software was selected as an organisational tool to support this process and help make the large quantity of data more manageable. NVivo 12 was appropriate as a database to organise the data reduction process of coding, but the software did not shape code development; for example, no data queries were run in NVivo to organise data within the software. At the conclusion of coding, Word documents were created that captured provisional themes that cut across the interview structure but remained influenced by it because the interview schedule reflected research aims. Themes are constructed, rather than emerging from the data (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013) and exist as higher order abstractions of patterns of meaning (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) so were subject to continuous reorganisation to check for their adequacy in accurately representing participants’ accounts while incorporating theoretical and personal reflexive insights based on the knowledge and expertise of the authors (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2022). The first author conducted the primary analysis, as is both typical and recommended in RTA (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2019; Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2022) but to maintain critical distance and ensure the theoretical adequacy and coherence of the themes, the analysis was revisited repeatedly through consultations with the other authors, who reviewed and provided feedback on theme development and the production of research reports.

Results

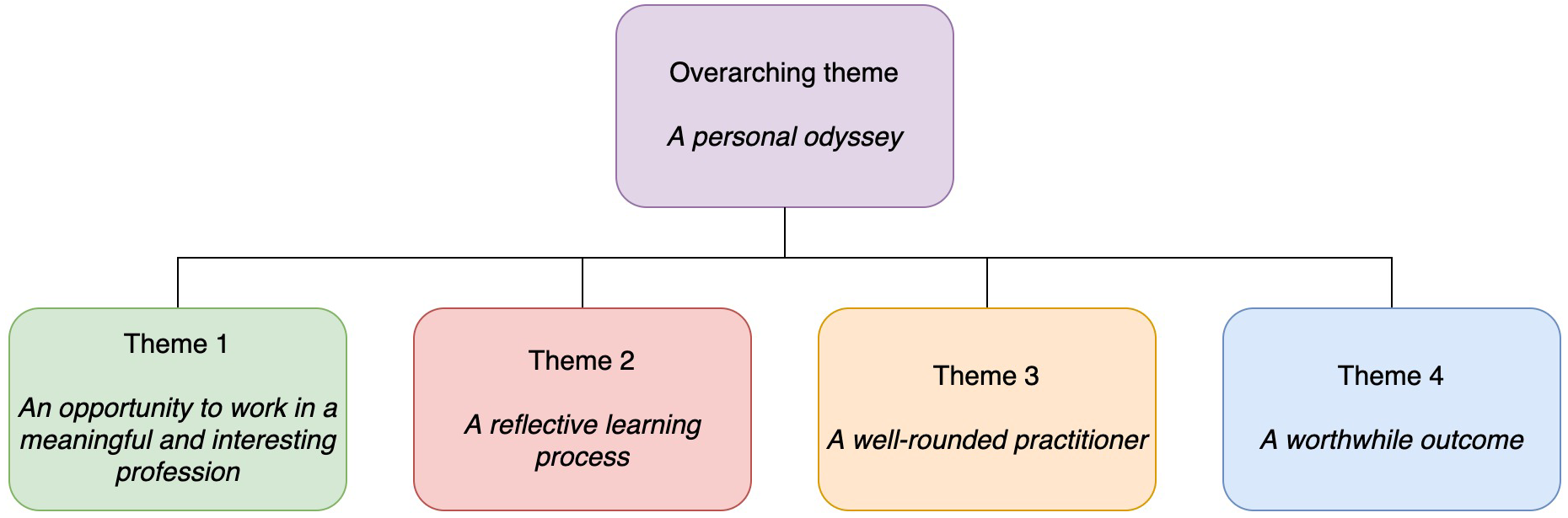

The study’s findings were organised thematically into a superordinate theme and four main themes (Fig. 1). Each participant contributed something to each theme, but counts are avoided in RTA because frequency is not equated with theoretical importance (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2022).

Figure 1. A concept map of themes.

Over-arching theme: A personal odyssey

A single over-arching theme of training as a personal odyssey was identified, inspired by discussion of choice of image and subsequent discussion. While the metaphor of a journey was assumed in interview questions, it was a personal odyssey in the Homeric sense of being a testing experience that drew on participants’ resources to make a transformative professional transition that could change participants as professionals and people. Images included Madeline’s ‘a smooth sea has never made a skilled sailor’, Dolly’s ‘masks’, and Eliza’s ‘CBT train’ that she was ‘trying to get on’. Jayne’s account of her image of ‘mountaineers climbing Everest’ clearly illustrated the over-arching theme, saying:

‘Quite a turbulent journey, but also one with a very high reward and a very big achievement at the end of it. So, one that involved both previous experience and knowledge … but also one that had to be an experience that involved that flexibility and that adjustment that’s needed to learn new experience and face challenges that you can’t always prepare for … on my course there were a lot of things that were out of my control that I had to deal with and overcome and at the end of it, completing the course, reaching the summit, was just such a massive, monumentous [sic] achievement.’

The following sections elaborate the four constituent themes.

Theme 1: An opportunity to work in a meaningful and interesting profession

Motivation was understood as constituting a contextual cost–benefit calculation (Eccles and Wigfield, Reference Eccles and Wigfield2020). Four potential benefits were: the meaningfulness of the work as an integrated motivation, which refers to the internalisation of values as autonomously regulated motivation (Deci and Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan1985); an interest in the work, which refers to intrinsic motivation to undertake an activity for its inherent satisfaction (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2020); the utility or instrumental value of a motivational choice such as a career opportunity; and the prospect of self-expansion (Aron and Aron, Reference Aron, Aron, Fletcher and Fitness1996). The potential benefits were set against the potential cost of training given the resources available to take advantage of the opportunity (Flake et al., Reference Flake, Barron, Hulleman, McCoach and Welsh2015).

Formative influences, including personal or family members’ experience of mental health problems and therapy, could be influential factors in integrated motivation that acted recursively to validate the approach. For example, May said:

‘I’ve had CBT and it worked really well for me, so I’ve got even more faith in the model … it definitely influenced me wanting to do it because I’ve just seen the difference it can make … having my own experience of that as a patient, it made me more … trusting and invested in the theory.’

The work itself could also hold intrinsic value as an interesting activity that contributed to self-expansion. Kate said the work with young people allowed her to express her ‘creative side’, while Colleen said that although she ‘rather fell into’ mental health work, she found it ‘really fascinating’.

The role could also hold instrumental value in advancing one’s career. Lizzie said applying was a pragmatic choice after not getting on to a clinical psychology doctorate because she thought, ‘I can’t wait another year in this job because … I’m not progressing in my career’. Training could also be a normative opportunity, for example Amy said that as a Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner (PWP), ‘professionally it has felt like quite a natural progression’.

Motivation could be multiply determined (Litalien et al., Reference Litalien, Morin, Gagné, Vallerand, Losier and Ryan2017; Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2020). In addition to an integrated, values-based motivation, May also described the intrinsic enjoyment in ‘working out a puzzle’. For Madeline, motivation included an instrumental opportunity for professional advancement, an integrated desire to help more people, intrinsic curiosity about working with more complex presentations, and a drive for professional self-expansion (McIntyre et al., Reference McIntyre, Mattingly, Lewandowski and Simpson2014), saying:

‘I wanted to learn more about it and support more people, so I wasn’t able to work with social anxiety, OCD and I was quite interested in working with people struggling with social anxiety, OCD, curious about PTSD … a bit more diversity in the role I guess.’

Motivation to train was also contextual in that it could be influenced by personal and professional circumstances. Susan said that her experience of managing CBT therapists ‘got me really curious because all of a sudden I was thinking, “gosh, that sounds like really interesting work” and I wanted to know more’ but her interest translated to action when facilitated by ‘having a really supportive manager, who was saying “look, if you want to do this you can”’ combined with facilitative personal circumstances to become ‘the right opportunity for me at the right time’.

While role models could provide an inspiration to train, some could make training seem daunting and potentially costly, for example Paula said it was described to her by a former trainee as ‘hell on acid’. This could lead to ambivalence and hesitation. Amy said she delayed her application by a year because:

‘The almost horror stories I’ve heard of how it’s the worst year of your life, it’s so difficult, it’s almost at times unmanageable … it made it quite a daunting prospect to think about applying for it.’

Thus, the opportunity was one in which a participant might balance the potential multiple gains available from training (meaning, interest, utility, self-expansion) with its potential costliness in the context of their personal and professional lives (Eccles and Wigfield, Reference Eccles and Wigfield2020).

Theme 2: A reflective learning process

This theme describes the interaction between components of training that contribute to learning, including the felt experience (affective domain), the active use of personal and professional support (coping behaviour), the personal and professional context, for example the structural and contextual features of the learning setting (resource adequacy), and an iterative, self-regulated, experiential learning process (learning strategies). To the extent that resources, coping, and learning strategies were adequate to the learning context, and the context was reciprocally adequate to learning needs, participants experienced a sense of mastery that could make the process feel stimulating despite it being demanding, consistent with longstanding literature on learning for mastery or competence (Bloom, Reference Bloom1968; Elliot and Dweck, Reference Elliot, Dweck, Elliot and Dweck2005)

The self-regulated experiential learning process could be described in terms of an iterative, non-linear process consistent with experiential learning models (e.g. Borton, Reference Borton1970; Kolb; Reference Kolb1984; Grimmer, Reference Grimmer2022). The learning process linked (1) focusing on an aspect of knowledge or practice, such as lecture material, assignments, presentation of recordings in group supervision, and participation in self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR) and other experiential exercises, (2) reflecting on and evaluating the material, including one’s own knowledge and skilfulness, sometimes by social comparison with peers (e.g. in group supervision) or experts (e.g. demonstration role plays), and (3) active experimentation in role-play and in vivo workplace experience. Amy said:

‘I’d done a behavioural experiment but hadn’t really been very specific in what we were testing, and it hadn’t gone very well. And I took that to supervision, and it was still really helpful and the supervisor saying like, “I can see why you’ve done that, here’s how it could be improved”. And we had a plan for the next session. And I just think, if you do what feels right in that session, whether it is or isn’t, you still learn so much from that.’

Self-practice-self-reflection (SP/SR) could be valued as particularly vivid and memorable experiential learning that led to greater understanding. Understanding is conceptually different from either declarative knowledge or procedural skills, being better thought of as an integrative, metacognitive capacity to adapt, interpret, and flexibly apply knowledge and skills in diverse contexts that develops from active-constructive-interactive learning activities (Chi, Reference Chi2009). The role of SP/SR in developing the deep learning associated with understanding was described by Eliza, saying:

‘The moment I could turn it round and apply it to myself, it became easier to understand what I was doing with the client, again that SP/SR work, the moment I started doing that, the penny dropped.’

SP/SR could also help raise awareness of the impact of the personal on the professional, i.e. crossing the ‘reflective bridge’ (Presley and Jones, Reference Presley and Jones2024), as Sarah explained:

‘I’m grateful that some of the assignments last year were looking at our own stuff and what we bring to sessions … sometimes I do notice myself having these unrelenting standards or trying to fix everyone, for example, and then just noticing it is enough to remind yourself that actually it’s not very helpful.’

Coping behaviours, which could encompass many dimensions of the personal, professional, and educational, helped foster resources. Having time away from the course to focus on other important parts of one’s life could be valued, as was peer support, for example using cohort-specific WhatsApp groups. Contributing to the learning of one’s peers could also help maintain engagement and motivation, and thus was arguably a coping behaviour through identifying the self as part of a collaborative venture. Jayne said,

‘It wasn’t just my journey … I needed to seek support from others, but also share my knowledge with others too, in the hope that I helped some people to some extent on the course too.’

Resource adequacy refers to the quality of both the educational inputs and workplace environment. For example, supervision could provide emotional support and reassurance as well as technical and conceptual input. When a workplace made adaptations, such as allowing trainees to choose suitable clients, it was perceived as highly supportive. However, an ill-prepared workplace could have a negative impact. Eliza, the only CBT practitioner in a small and inexperienced inner-city service provider, described a paradoxical impact between enhancing fidelity at the potential cost of not making appropriate adaptations because she lacked more experienced colleagues, saying:

‘I had to do stuff by the book because there was nobody to say, “ah, maybe you could do that at that stage … move CBT around” … maybe that was a good thing for the protocols or being faithful to CBT and maybe it wasn’t so good for the clients.’

A mismatch, or asynchrony, between the timeliness of learning resources and the reality of the workplace could be stressful and undermine both learning and a sense of competence. Shannon described the relentlessness of the training role and the impact of treating people presenting with problems that had not yet been taught, saying:

‘You might have to take on an OCD patient, but you’re not going to have the training for eight weeks and so you’re having to really utilise supervision … but then also you’ve got to use that supervision time for the other patients because you also don’t really know what you’re doing with them either … at the beginning it takes so long to prep for each patient because you are literally teaching yourself what to do just before the session … then afterwards you’re trying to think, “OK, so now what do I do?” … then I’m writing up the notes … and then you’ve got to prep for the next patient after that.’

The focus on the Revised Cognitive Therapy Scale (CTS-R) could create unhelpful pre-occupation to the detriment of patient care. Lizzie noted that, ‘you can be so wrapped up in being competent that you become incompetent almost [laughs]’. The focus on the importance of passing assignments through demonstrating competence on recordings (i.e. learning for performance) could create perverse incentives. Shannon described how she found focusing on the CTS-R as a foundation for competence unhelpful because:

‘All that did was just make us good at the things that we knew would get the highest points, like the agenda, and at the end checking the barriers for home practice and really nailing down into that and [sighs] recapping on the session and did we cover everything and if not, should we add it to next week’s agenda? … to me that isn’t showing competence as a therapist … that’s not me as a person, that’s not me as a therapist.’

While role-play and feedback on recordings in supervision were highly valued learning resources, having few or no opportunities to observe competent practice could negatively impact learning. Without a demonstrated model of practice, participants might need to resort to guesswork or skills acquired in previous roles. Sarah said:

‘There was no opportunity to shadow any CBT sessions in my service … but that would have been really helpful because I didn’t really know what people were looking for.’

In the affective domain, the demands of training relative to resources could have a major emotional impact leading to descriptions such as ‘overwhelming’ or ‘information overload’. May likened the performative pressure to a dance competition, saying:

‘On Strictly Come Dancing the dancers [are] having to think about doing a hundred things at once but we’re trying to do it mentally and audibly within the session and then you’re trying to do that whilst also not really having a clue what you’re doing and there’s so much that you don’t know but you’re still trying to hit all these criteria … and at a very high standard.’

However, when resources were adequate to demands such that participants experienced a sense of mastery, it could feel highly stimulating. Susan said:

‘It’s almost like a paradox doing this course because … there’s times when it does feel incredibly difficult but then there’s another part of me that just is enjoying it so much because I’m learning so much … it’s a roller coaster, but … it’s an enjoyable journey, so far anyway.’

In contrast, if a participant struggled, it could be highly discouraging. Dolly said that at the halfway point in her training she felt profoundly deskilled, which appeared to inhibit her professional identity transformation from mental health nurse to CBT psychotherapist, saying:

‘I’m not doing very well … so the CTS-Rs feel quite damning at the moment, quite negative, but then there’s the split where you’re in clinical practice, and you have to have the other mask on of the happy face … it’s that, that confusion really, of am I, I don’t know where, whether I’m incompetent or competent and yes, so confusion, identity confusion, definitely.’

Theme 3: A well-rounded practitioner

This multi-faceted theme refers to what participants understood to be the multiple components that make up competence. Jayne summarised it using the idea of ‘a well-rounded practitioner’, who is:

‘Somebody who can achieve that therapeutic alliance, somebody who considers in detail the evidence base and the research to inform what they’re doing, somebody who’s very personable, somebody who is quite flexible and adaptable and within that, somebody who’s quite confident in what they do, so when they’re in that therapy room, they can adapt, they can work with what they’ve got and can use that research, that knowledge, that experience, and bring it into the room for that person who’s in front of them.’

Participants described internalising external competency criteria. For example, Eliza said that:

‘That’s still stuck in my head, that CTS-R of, you’re setting the agenda, you’re showing empathy, or you’re gonna discuss about emotions, you’re gonna discuss about how they feel in their body, you’re gonna get a cognition, or you’re gonna take ’em on a guided discovery, you’re gonna do an intervention.’

However, external frameworks could be reported humorously, perhaps indicating that they were seen as insufficient to describe competence fully. On being asked what competence meant to her, Paula said, ‘an image of all these competency frameworks just flew into my head [laughs], shall I just reel those off?’, and Shannon wryly said, ‘well, following the Roth and Pilling’s [laughs], God you can tell I’m fresh out of Uni’.

Competence in CBT might also be understood in terms of similarities and differences to the knowledge and skills required in a former professional role. Prior ways of working could be an obstacle to be overcome; Michelle, a former teacher, described how learning to use ‘curiosity and exploration’ in guided discovery was very different from her previous didactic role. However, the former professional self could be a personal resource or asset to one’s colleagues. Kate said her previous systemic practice helped her grasp collaboration because in her former systemic training she ‘had it ingrained into me that to effect change they need to be the ones to bring it about themselves’. Sarah said that as a former social worker, current colleagues had asked her for advice, so ‘being able to draw on that knowledge and feeling like you’re contributing to the bigger team as well is really nice and helpful’.

Having what May called ‘a really robust knowledge of the theory’ was also relevant to competence, for example knowing the rationale behind interventions. Colleen and Paula describe a developmental process from a mechanistic approach to one that is imbued with far greater understanding and procedural competence consistent with developmental models that distinguish between novice and competent practitioners based on the application of increasingly sophisticated metacognitive awareness (Rousse and Dreyfus, Reference Rousse, Dreyfus, Silva Mangiante and Peno2021; Zimmerman and Schunk, Reference Zimmerman and Schunk2001). Paula said:

‘When I first started this training … I was doing the interventions but not really knowing why … it was like, “here’s a technique, do this, it’s been shown that it works” and then I would go into supervision and my supervisor would say “well, why have you done that?”. “Well, ’cause it tells me to here in the protocol”. So for me, the first step towards me feeling more competent is not just knowing which technique to use, but also why.’

In Colleen’s account, competence and confidence seem to reciprocally enhance each other to produce increasing procedural automaticity and a corresponding attitude shift from therapist responsibility for change to the patient’s self-regulated learning (Rønnestad and Skovholt, Reference Rønnestad and Skovholt2013). Colleen said:

‘I don’t need to prepare for the patient sessions … I could do things off the hoof more because they’re more second nature … I’d have got turns of phrase worked out, how I’m expressing myself … If situations arise, I’ve probably seen something more like it before, so I can work out how I’m gonna handle that and where that might lead to … I’m certain it’s from being so much more confident, I know I’m good enough at it, that enables me to work less hard in it … just sitting back and just asking more probing questions … not trying to lead what they think about it, but just really genuinely letting it follow from what’s come before from the patient rather than me leading the horse to water and making sure it absolutely drinks when it gets there.’

Participants also cited a range of therapy-enhancing personal qualities such as warmth and kindness, and a non-judgemental attitude. This could involve bringing authentic but boundaried aspects of the personal into the professional relationship. Shannon described the importance to competence of how the patient experiences her, saying:

‘I try to be really authentic, it feels like there’s … a crossover in order to ensure that the patient feels I’m genuinely there with them but still boundaried to not overshare my life and my personal experiences.’

Participants described the importance of individualising treatment and making suitable adaptations, for example for age, educational level, and neurodiversity. Metacompetent adaptations seemed to require a rapprochement between adherence to CBT as taught and the metacompetencies needed to individualise CBT. For example, Eliza said:

‘A good, competent session to me is being able to be faithful to the CBT, but still being individualised … building on that foundation, that alliance with the client, but also trying to stick to what I know works.’

However, personalising CBT could convey a range of meanings from a within-model change in sequencing behavioural activation, to temporarily integrating a ‘heretic’ (Castonguay, Reference Castonguay2013) non-CBT approach such as person-centred counselling, which might reflect level of experience, professional background, or personal values.

Becoming a reflective evaluator of one’s competence could involve understanding the limitations of one’s current level of experience and an awareness of the post-qualification experience needed to consolidate and extend competence. Madeline said, ‘it’s a minimum training standards course and once that clicked in my mind that this is just to give you the foundation … I think that was helpful’. Shannon who was recently qualified, said:

‘I haven’t had very many that perfectly go through every stage when you’re learning that you would like to go through, so you know how to do everything properly, so I feel I need quite a few more examples of each anxiety disorder to feel like I can really get it.’

Having clients return to treatment could reassure practitioners about their competence at the beginning of training, but with experience was seen as limited. Client understanding could become a more useful metric, reflecting perhaps the dropping of idealistic standards and a focus on the client’s responsibility for change (Rønnestad and Skovholt, 2013). Amy said:

‘If a client tells you something they’ve learnt or taken from the sessions, you’ve helped them to get to that point, that can be really helpful in measuring some level of competence.’

Theme 4: A worthwhile outcome

This theme reflects an appraisal of the worth or value of the training as well as the types of personal and professional outcomes that were identified, the latter indicating that the ‘reflective bridge’ (Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones, Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018) could be bi-directional and might be mutually reinforcing in that growth in the personal self from being in the professional role potentially enables greater relational sensitivity in the therapist role.

For qualified participants, passing the course could validate the effort required to complete the qualification. Jayne said:

‘I got to the end and I thought, well, actually I’ve written this many essays, I’ve written this many pages for my portfolio, I’ve seen this many young people and done this many clinical hours, that brought it all into perspective, and I was like, wow, yeah, I know it felt a lot, but it was a lot, and look at how much I can show for that now.’

Professional transformation as an outcome could include not just competence in terms of acquired knowledge and skills, but the development of a valued professional identity, and a sense of pride. Jayne said:

‘Something that I never really perhaps felt I had before was an identity … I could list lots of skills and lots of experience, but it wasn’t a named thing … whereas now I can quite confidently say I am a therapist. I’ve done the course, I have the experience and … that excites me because I think OK now I can own that and be proud of that.’

Completing the training could also validate the initial motivation to train to work in a meaningful and interesting profession. Sarah said, ‘I’m glad I did it … to be so knowledgeable about something that can help everybody at some point in their life is a real honour’.

The experience of training could also lead to personal insight by applying CBT knowledge and skills reflexively. The potential for serendipitous early gains in CBT training might be seen as having a parallel to the concept of sudden gains in therapy (Tang and DeRubeis, Reference Tang and DeRubeis1999). It was described by Maxine, the participant who was least advanced in her training, who said,

‘Gosh, it’s not too early to ask, it’s made me reflect back on my experiences, the fact that I put in place protective mechanisms for my anxiety that I hadn’t recognised, that’s been an eye-opener.’

Maxine’s recognition of her safety-seeking behaviour seems to reflect a cognitive shift suggesting that CBT training, much like therapy itself, can foster reflective self-awareness, leading to transformative personal growth (Mezirow, Reference Mezirow and Illeris2009). Increased reflective self-awareness could even bring personal benefits for practitioners who had never experienced mental health problems. Colleen said:

‘I’m the most unreflective person naturally, I think I have bounded through life, completely disregarding of my own role in it … I’m more thoughtful … it has slowed me down, made me more questioning … “why do I act in that way”, it’s made me much more attuned to my own thought and behaviour processes.’

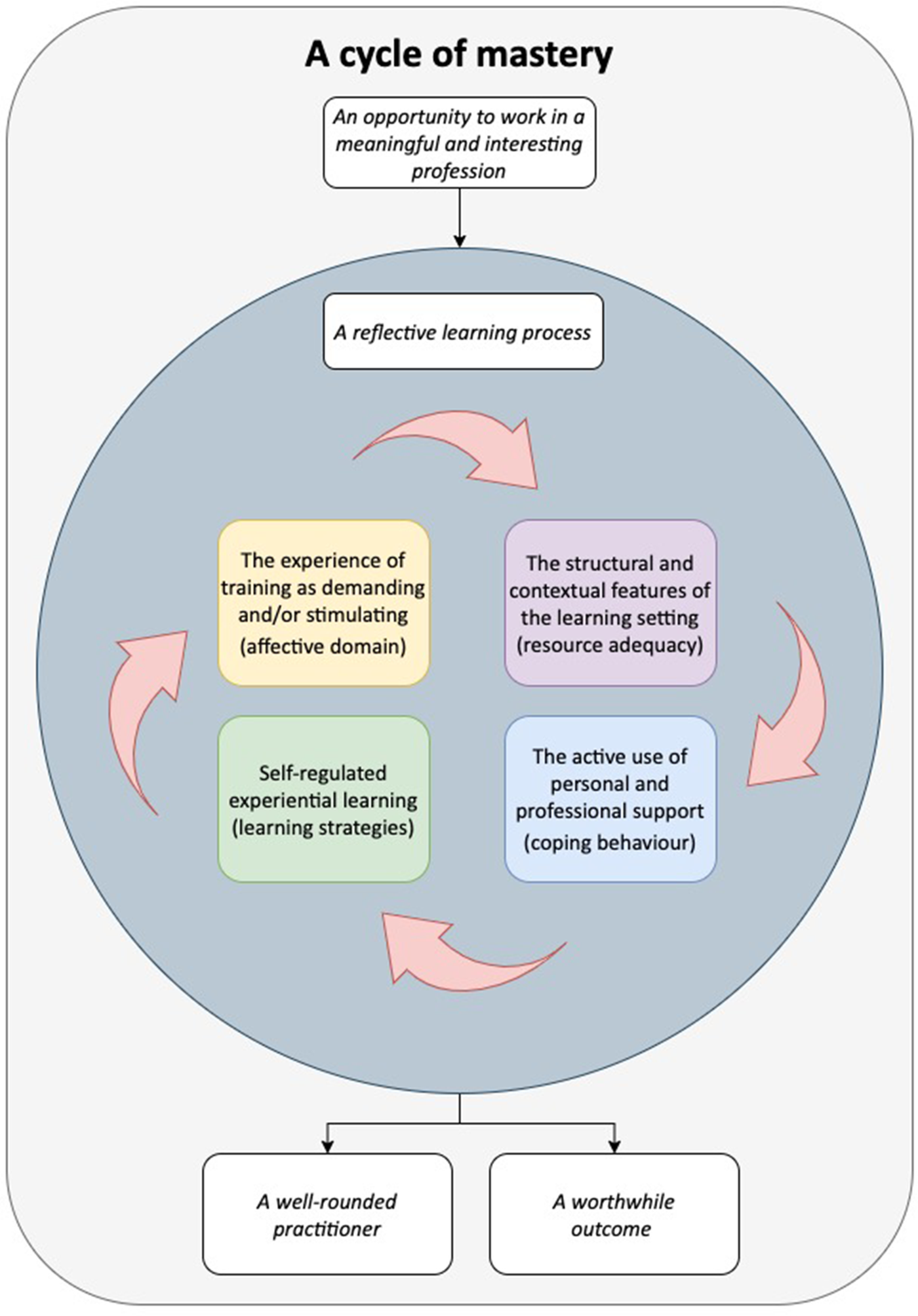

A cycle of mastery

Synthesising the themes above, we tentatively propose that the relationship between them might usefully be represented by a ‘cycle of mastery’, in line with the research aim of linking the experience of training with the development of competence as participants understand it. In the illustrative diagram shown in Fig. 2, training is represented as having multiple interacting facets that unfold temporally and link the person of the trainee with the context of learning. Interactions between motivations that comprise an opportunity to work in a meaningful and interesting profession propel trainees to transition into a learning environment that is more or less adequate to their learning needs. To the extent that trainees’ coping behaviours, as well as adequate learning resources, enable them to engage in effective learning strategies, within a reflective learning process, they have an affective experience of training as both demanding and stimulating as they attempt to master its demands in pursuit of competence. Repeated iterations of this cycle help develop relevant competencies in terms of both taught competency frameworks and in an idiosyncratic understanding of competence that together help form a well-rounded practitioner. At the completion of the course trainees have achieved a level of professional and personal development that they can regard as a worthwhile outcome.

Figure 2. A proposed ’cycle of mastery’ model of the learning process in CBT training.

Discussion

This section discusses the results through the lenses of relevant literature and the first author’s reflexive positionality (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2022). It also considers the limitations of the study, makes suggestions for practical strategies relevant to each theme and future research, and concludes by briefly evaluating the findings in terms of the research aims.

An opportunity to work in a meaningful profession

Some familiar aspects of the existing literature were present in that motivation to train in psychotherapy often includes liking intellectual stimulation, a strong altruistic desire to help others, and personal experience of mental health problems and therapy (Elliott and Guy, Reference Elliott and Guy1993; Farber et al., Reference Farber, Manevich, Metzger and Saypol2005; Guy, Reference Guy1987). Unlike Roscoe and Wilbraham’s (Reference Roscoe and Wilbraham2024) analysis of motivations to train in CBT that divided practitioners into those who endorsed CBT and those who were enhancing their career, the findings reported here suggest that motivation is a mix of personal dispositions and circumstantial opportunity set against perceived costs. For the first author, the construction of this theme was reminiscent of his professional training in CBT and reflects a social cognitive understanding of motivation in career choice as multiply determined by a mixture of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, and contextual opportunity (Lent et al., Reference Lent, Brown and Hackett1994).

Practice recommendation

It might be helpful to validate and normalise the prevalence of a mental health history in this population and support the ways in which it can be a strength (Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Scior, Clements and Mackenzie-White2020). Given that intrinsic motivation has been shown to mediate the relationship between adequacy of workplace resources and occupational engagement (Van den Broeck et al., Reference Van den Broeck, Vansteenkiste, De Witte and Lens2008), it might be useful to help trainees focus on the inherently meaningful and interesting aspects of training.

A reflective learning process

The role of reflection on learning from educational inputs was described across all elements of the curriculum in a finding that aligns with the importance ascribed to reflection that dates to Dewey (Reference Dewey and Dewey1910, Reference Dewey1933). Experiential exercises were highly valued, consistent with previous research (Gale and Schröder, Reference Gale and Schröder2014), and experiential learning with a focus on the person of the therapist was regarded as important in personalising knowledge. Experiential learning, as Kolb (Reference Kolb1984) observed, is consistent with Piaget’s (Reference Piaget, Green, Ford and Flamer1971) model of learning as adaptation through equilibration, i.e. moving from satisfaction with one’s current learning to disequilibrium as one becomes dissatisfied, to a new equilibrium with a greater level of competence. The process of progressively resolving the disequilibrium caused by repeated confrontation between the adequacy of what is known and what is now required, helps account for the paradoxically demanding but also stimulating nature of the experience, to the extent that participants master the challenges of learning given adequate resources. Highlighting the relationship between SP/SR and deeper learning suggests that the DPR model (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock and Davis2009b) might benefit from accommodating ‘understanding’ as a distinct, metacognitive category of knowledge. Sociocultural perspectives were also relevant, for example the desire to observe competent practice reflects sociocultural perspectives on scaffolding (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Bruner and Ross1976) to enable trainees to move into what Vygotsky described as their Zone of Proximal Development (Cole et al., Reference Cole, John-Steiner, Scribner and Souberman1978) Thus, both cognitive constructivist and sociocultural approaches are potentially relevant to understanding the personal and contextual factors that influence training as a developmental process that leads to competence.

The first author teaches reflective practice and has developed a model of CBT and trainee learning that draws on this (Grimmer, Reference Grimmer2022) so it was a concept that was readily available which may have influenced analysis of the data. However, the role of reflection in learning was present in so many facets of the course that it seems safe to conclude that this theme is an accurate reflection of participants’ experiences as adult learners.

Practice recommendation

Greater opportunity to observe competent practice prior to experimenting with personalising it would almost certainly be widely appreciated as a valuable contribution to the adequacy of resources to meet learning needs, and a useful starting point for experiential learning. Formative collaborative learning tasks that enable trainees to support each other’s learning might be highly valued.

The well-rounded practitioner

While the well-rounded practitioner does not map straightforwardly on to existing competence frameworks such as Roth and Pilling (Reference Roth and Pilling2007), the items on the CTS-R (Milne et al., Reference Milne, Claydon, Blackburn, James and Sheikh2001), or the DPR model (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009b), participant accounts did describe elements of each in terms of technical and conceptual knowledge and skills, facilitative personal and relational qualities, and metacompetent fidelity (Whittington and Grey, Reference Whittington, Grey, Whittington and Grey2014). Rather than describing equivalent generic skills such as Roth and Pilling assume, participants described idiosyncratic knowledge and skills derived from diverse previous roles, which may have implications for the assumed adequacy of both mental health-related tasks and generic psychotherapy process skills. Campbell-Lee et al. (Reference Campbell-Lee, Barton and Armstrong2024) suggest that metacompetencies develop after completion of training as practitioners encounter more complex client work. However, participant descriptions of the importance of adapting practice meant that metacompetence, even if not called by that name, was already well established as part of the concept of personalising CBT, even for trainees who were early in their training, perhaps due to prior experience or personal maturity. Having taught on NHS Talking Therapies training for over 10 years, the first author believes that the pace of training, and the asynchrony of what was treated with what was taught might mean that when participants encountered the reality of practice and the way it differed from the more idealised taught models, it forced a degree of improvisation built on prior professional foundations, consistent with Schön’s (Reference Schön1983, Reference Schön1987) concept of a reflective practitioner, with perhaps unpredictable consequences for developing an understanding of competence that aligns with competence frameworks.

Some of the methods of evaluation were held in low esteem by participants, or the context in which they were taught was regarded as unhelpful. The latter point might reflect the difference between learning for performance and mastery (i.e. competence) with available evidence suggesting that learning for mastery is both more intrinsically motivating and develops greater knowledge and skilfulness than learning for performance (Ames, Reference Ames1992). While summative assessments perform a gatekeeping function (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2020), the potential for learning for performance to create perverse incentives is important to recognise given that they can have a negative impact both on competence and wellbeing (Deci and Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan2000).

Practice recommendation

A pressing issue, and one with structural obstacles, is to ensure that trainees are not treating cases for which they have not been taught to protect both them and service users. Learning for performance has not been shown to enhance competence and can lead to negative outcomes such as helplessness after failure, attributions to low ability, loss of self-worth, rumination about the setback, loss of intrinsic motivation, and lower grades (Grant and Dweck, Reference Grant and Dweck2003; Kusurkar et al., Reference Kusurkar, Orsini, Somra, Artino, Daelmans, Schoonmade and van der Vleuten2023). Therefore, we would recommend that summative assessment is only carried out on procedural competence when that competence is well established. Informal assessment of competence could be achieved by, for example, role-play, which research suggests is a promising approach in place of, or to augment, recordings of workplace practice with real clients (Liness et al., Reference Liness, Beale, Lea, Byrne, Hirsch and Clark2019; Marriott et al., Reference Marriott, Cho, Tugendrajch, Kliethermes, McMillen, Proctor and Hawley2022). Feedback from trainees on their perceived level of competence and their readiness to submit summative recordings might help discriminate between gate-keeping and learning for mastery/competence. This might be enhanced by greater clarity about appropriate transferable knowledge and skills from former roles.

A worthwhile outcome

The current findings are somewhat different from Wolff and Auckenthaler’s (Reference Wolff and Auckenthaler2014) dichotomous description of the development of a professional identity, although this research did find that the development of a CBT professional identity could be a significant and worthwhile outcome and a source of pride. It was not clear if this reflected a feature of the participants and little to nothing is known of those for whom training does not represent a worthwhile outcome or who fail to complete it. The participants in this study represent an equifinal outcome (different origins culminating in a similar outcome, i.e. being in or completing training) so pursuing research on multifinal outcomes (e.g. looking at a cohort of PWPs and exploring the range of career progressions) might be a useful adjunct. The next stage of this research focuses on experienced practitioners, which should also add detail as to how both the understanding of competence develops and how attitudes towards the practice of CBT mature.

There are reports that learning and practising psychotherapy can lead to positive personal outcomes (e.g. Elliott and Guy, Reference Elliott and Guy1993) and this was the case here. There was evidence that experiential learning was perceived to help practitioners integrate personal and professional selves (Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones, Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018; Presley and Jones, Reference Presley and Jones2024) and that the ‘reflective bridge’ is bi-directional; the person of the therapist informs the attitudes and interpersonal skills of the therapist while the professional self’s technical and conceptual knowledge and skills can also inform the wellbeing and development of the personal self. Insofar as the experience of training provides insight and resources that can have personal benefit, then what is learned is experientially validated in a way that is reminiscent of the impact of personal therapy as a component of training (Grimmer and Tribe, Reference Grimmer and Tribe2001).

The first author’s background is not restricted to CBT and his training involved experiential and self-development work. The felt sense of personal transformation has informed the first author’s belief in the importance of the personal to the professional and the potentially positive impact of one’s professional life on the person. This may have influenced data analysis in terms of seeking confirmation of the personally transformative impact of training. However, the specificity of the changes identified and the relationship to prior lived experience of mental health problems suggest that this was a credible finding.

Practice recommendation

Given the potential for increased reflective self-awareness as a person and professional, courses might usefully provide formative opportunities for reflection on both professional and personal gains. It was notable that participants frequently reported how helpful and interesting they found it to take part in the research so this might take the form of a self-reflection workshop to help trainees process the experience of training. The first author has started to implement this with trainees nearing the end of their training.

A cycle of mastery

Mastery as a process and outcome is well established in the educational literature, for example Guskey and Anderman (Reference Guskey and Anderman2013) trace mastery to 13th century concepts of guild membership achieved through successive steps from apprentice via journeyman to master, similar to a preceptor model (Blum, Reference Blum2009) and to a progressive process of competence development (Frank et al., Reference Frank, Snell, Cate, Holmboe, Carraccio, Swing, Harris, Glasgow, Campbell, Dath, Harden, Iobst, Long, Mungroo, Richardson, Sherbino, Silver, Taber, Talbot and Harris2010). Therefore, the term mastery is appropriate to a training that is at once academic (conceptual), vocational (technical), procedural (skills-based), attitudinal (values-based), and relational (interpersonally-based).

Practice recommendation