Introduction

NHS Talking Therapies for anxiety and depression (NHS-TT, formerly Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT)) was established in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2008 to deliver treatment for common mental health issues such as anxiety and depression (Clark, Reference Clark2018) within the National Health Service (NHS). NHS-TT operates a stepped care framework, in which treatment resources are allocated based on condition severity and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines regarding the treatment of particular conditions (NHS Talking Therapies, 2024). Most service users initially receive a ‘low-intensity’ treatment (ranging from use of self-help books or computer platforms to receiving short-term manualised cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) sessions), then if clinically indicated, go on to receive a ‘high-intensity’ treatment, which typically involves 12–20 therapy sessions based on an individualised formulation (Chan and Adams, Reference Chan and Adams2014; Richards et al., Reference Richards, Bower, Pagel, Weaver, Utley, Cape, Pilling, Lovell, Gilbody and Leibowitz2012). For some clinical conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and social anxiety disorder, low-intensity interventions are not recommended by NICE, so some service users start with a high-intensity intervention.

Upon presenting to NHS-TT services, service users are typically assessed by Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners (PWPs), a junior workforce within NHS-TT that conduct assessments and deliver cognitive behaviourally informed low-intensity interventions. During assessments, the PWP and service user discuss current difficulties and consider the main problem the service user would like to work on. Based on this, the PWP selects a ‘problem descriptor’ (descriptions of psychological difficulty derived from ICD-10 codes) in the electronic patient care record, and allocates the service-user to an appropriate low-intensity (sometimes called ‘Step 2’) or high-intensity (‘Step 3’) treatment (NHS Talking Therapies, 2024). NHS-TT uses problem descriptors to match service-users to appropriate, disorder-specific cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) protocols (Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Cape, Leibowitz, Aguirre, Jena, Cirkovic, Wheatley, Main, Pilling and Buckman2020). NHS-TT services using problem descriptors frequently and accurately achieve higher rates of recovery and reliable improvement (Clark, Reference Clark2018; Skelton et al., Reference Skelton, Carr, Buckman, Davies, Goldsmith, Hirsch, Peel, Rayner, Rimes and Saunders2023).

The NHS-TT assessment process poses challenges for PWPs given that large amounts of clinical, safety, and practical information must be collected in short time periods, while simultaneously conveying empathy, understanding and openness to patients (Scott, Reference Scott2018). PWPs must also be able to assess service users who are experiencing conditions they are not trained to treat; one such condition is PTSD. PWPs need to be able to discuss traumatic events with service users, identify if PTSD is present and the main presenting difficulty, and consider the most appropriate intervention, which may include NHS-TT interventions or referral to other services if service-user needs cannot be met within NHS-TT (NHS Talking Therapies, 2024).

NHS service users frequently report experience of traumatic events (Finch et al., Reference Finch, Ford, Lombardo and Meiser-Stedman2020; Sandford, Reference Sandford2023). Prevalence research in this area indicates that between 50 and 75% of primary mental healthcare service users in the UK have experienced clinically significant threatening events in the year preceding assessments; furthermore, 67% report at least one experience of childhood trauma (Hepgul et al., Reference Hepgul, King, Amarasinghe, Breen, Grant, Grey, Hotopf, Moran, Pariante, Tylee, Wingrove, Young and Cleare2016; Thomlinson et al., Reference Thomlinson, Muncer and Dent2017). Experiencing a traumatic event is Criterion A of a PTSD diagnosis, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edn; DSM-5; American Psychatric Association, 2013); the American Psychatric Association (2013) defines a traumatic event as actual or threatened, death, serious injury or sexual violence, directly experienced, witnessed or learned about happening to a close relative or close friend. While traumatic events are often distressing and subsequently distressing to discuss openly in therapy (Boterhoven de Haan et al., Reference Boterhoven de Haan, Lee, Correia, Menninga, Fassbinder, Köehne and Arntz2021), experiencing a traumatic event is not synonymous with a PTSD diagnosis; PTSD is just one of many potential psychological reactions to trauma (Ehrenreich, Reference Ehrenreich2003).The prevalence of PTSD in the UK is estimated at 4.4% (Baker and Kirk-Wade, Reference Baker and Kirk-Wade2021).

Clinician capacity to distinguish between PTSD and other psychological experiences involving traumatic events can be limited, particularly in primary care settings (Cowlishaw et al., Reference Cowlishaw, Metcalf, Stone, O’Donnell, Lotzin, Forbes, Hegarty and Kessler2021; Ehlers et al., Reference Ehlers, Gene-Cos and Perrin2009). Several factors complicate such recognition (Frissa et al., Reference Frissa, Hatch, Fear, Dorrington, Goodwin and Hotopf2016). Firstly, information regarding trauma exposure is not always disclosed during initial assessments (Spoont et al., Reference Spoont, Williams, Kehle-Forbes, Nieuwsma, Mann-Wrobel and Gross2015). Secondly, service users with experience of trauma may perceive somatic symptoms as indicators of physical illness rather than mental distress (American Psychatric Association, 2013); conversely, colloquial use of terms such as ‘traumatic’ can contribute to both professionals and patients conflating difficult life experiences with PTSD (Tully et al., Reference Tully, Bhugra, Lewis, Drennan and Markham2021). Finally, diagnostic measures of trauma disorders may be susceptible to pathologising contextually normal reactions as trauma symptoms (Rosen and Lilienfeld, Reference Rosen and Lilienfeld2008). Such ambiguities highlight the importance of clinician knowledge and competency in identifying and appropriately responding to disclosure of traumatic event experience (Hall and Hall, Reference Hall and Hall2007).

How cases involving experience of traumatic events are assessed in mental health services can influence service user outcomes (Sweeney et al., Reference Sweeney, Clement, Gribble, Jackson, Carr, Catty and Gillard2019). Furthermore, the effectiveness of various PTSD treatments is influenced by assessment quality (Ehlers and Wild, Reference Ehlers and Wild2022; Laliotis and Shapiro, Reference Laliotis and Shapiro2022; Schnyder and Cloitre, Reference Schnyder and Cloitre2022). Robust assessment procedures in psychological services can guard against longitudinal harm to service users and encourage treatment engagement (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Bishop-Edwards, Chambers, Connell, Dent-Brown, Kothari, O’hara and Parry2019). Quality of such assessments is somewhat dependent on factors including clinician training provision, service culture, bureaucratic pressures, idiosyncratic skill application and therapeutic alliance strength (Nakash and Alegría, Reference Nakash and Alegría2013). Despite the importance of the accurate assessment of traumatic events, particularly in distinguishing experience of traumatic events from meeting diagnostic thresholds for PTSD, how clinicians in UK mental health services conduct such assessments in practice remains unclear in literature (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Brown and Carpenter2018).

Additionally, it is well documented that working with service users who have experienced trauma can prove stressful for clinicians (Voss Horrell et al., Reference Voss Horrell, Holohan, Didion and Vance2011). Junior mental health workers are particularly susceptible to such stress (Clemons, Reference Clemons2020). PWPs are provided weekly supervision, designed to offer case management, clinical oversight and wellbeing restoration. They can also access ‘duty supervision’ for support managing issues of clinical risk and safeguarding concerns. However, research surrounding CBT supervision indicates that experiences of supervisory practice can vary widely (Roscoe et al., Reference Roscoe, Taylor, Harrington and Wilbraham2022).

The present study therefore aimed to explore PWPs’ experiences of assessments featuring the discussion of traumatic events within an NHS-TT service.

Method

This study’s scope was established through collaboration between the authors and an NHS-TT service’s clinical leadership team, following staff feedback regarding challenges associated with assessing traumatic events. The service anticipated that thorough exploration of PWPs’ experiences of assessments featuring discussion of traumatic events would culminate in deeper understanding of challenges within the role, and eventual development of future training for PWPs. It was envisioned that the study’s results could help inform support for PWPs to manage the emotional impacts of such assessments, enhancement of PWPs’ PTSD identification and greater understanding of what future supports might benefit PWPs most.

Design

The study used individual semi-structured qualitative interviews. A semi-structured interview guide (see Supplementary material) was developed by the research team. Questions examined the emotional impact of assessing service users’ experience of traumatic events, the practical feasibility of conducting assessment calls featuring patient experience of traumatic events, and satisfaction with training regarding assessments featuring discussion of traumatic events. Data were analysed inductively according to the principles of reflective thematic analysis, outlined through a six-stage approach recommended by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021).

Participants

Twelve participants were recruited. All were 18 years old or above, capable of providing informed consent, and currently employed as a PWP in the participating NHS-TT service.

Procedure

All participants received study information and provided informed consent before participating. Interviews were conducted by the first author between August and September 2023. Technological issues led to missing data from one interview, which was excluded from analysis. Of the 11 interviews included, 10 were conducted via Microsoft Teams and one was conducted face-to-face due to participant preference. Interviews lasted an average of 50 minutes. They were audio- and video-recorded using Microsoft Teams and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Data from 11 participants were included in analysis. In line with recommendations from Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021), the data gathered was agreed upon as sufficiently rich and multi-faceted by the research team. Following multiple readings of each transcript to facilitate familiarisation (Stage 1), transcripts were broken down into individual items of meaning based on content and labelled with codes (Stage 2). An inductive orientation to coding was taken, with semantic coding used throughout the dataset. The first author coded with a critical realist ontology, aligned to the reflexive element of reflective thematic analysis, allowing the research team to reflect on their personal biases. Initial themes were then generated from these codes (Stage 3) using thematic mapping, and through reflexive conversation with supervisors were reviewed and developed. The first author’s perceptions as informed by experiences, society and culture were explored in the context of trauma within NHS-TT (Stage 4). Themes were subsequently refined, defined, and named (Stage 5). A thematic map detailing relationships between themes and subthemes was designed (see Fig. 1). Finally, analysis was written (Stage 6). Following initial analysis, two PWPs working for a different NHS-TT service were interviewed regarding the results as a means of triangulating data analysis. Their perspectives regarding themes, subthemes and quotes outlined in the Results section were explored and alterations were made accordingly.

Figure 1. Thematic map.

Reflexivity

The first author spent one year on a DClinPsych placement at this service in a separate workstream from PWPs. They approached this research mindful of the systemic challenges experienced by NHS-TT professionals. Additionally, they had prior experience in publishing qualitative research and were thus mindful of biases this could create.

Results

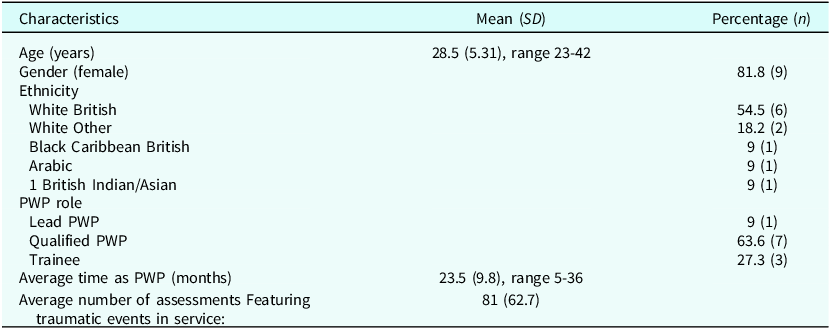

Nine women and two men were interviewed. Table 1 outlines their demographic information. Six themes, consisting of 13 subthemes, were established (see Fig. 1). These themes and respective subthemes are explored in sequence below. Further participant quotes substantiating these themes and subthemes are available in this paper’s Supplementary material.

Table 1. Participant demographics

PWP, Psychological Wellbeing Practitioner.

Navigating ambiguity makes assessments more difficult

Difficulties in fitting the life experiences reported by service users into NHS-TT problem descriptor criteria were described throughout the dataset. Among such challenges were navigating ambiguity regarding diagnostic criteria, inconsistent processes in assignment of problem descriptors, and uncertain discernment of appropriate referrals in a role untrained for PTSD treatment.

Difficulties distinguishing trauma from PTSD

Participants reported difficulties in distilling service users’ experiences of traumatic events into concrete problem descriptors and accordant treatment pathways. Numerous respondents explained challenges in identifying appropriate thresholds upon which trauma could be assigned to a problem descriptor:

‘In terms of descriptors within PCMIS, unless it’s PTSD … it feels hard to know what the right problem descriptor is.’ [P1]

Feeling lost upon encountering some patients reporting traumatic experiences was described:

‘When people don’t have those classic symptoms of PTSD, I think that’s when … I’m not sure whether I’m asking the right questions. I’m not sure if I’m gathering enough information to assess whether it is actual trauma.’ [P2]

Patients’ understanding of their experiences as traumatic sometimes contravened service trauma definitions:

‘You have patients who say trauma just because they’ve gone through something stressful.’ [P4]

Recognising symptoms as those of trauma, rather than simply difficult life experiences, was also depicted as challenging by various participants:

‘Probably got quite a lot of people that sort of would say they’ve experienced trauma or experienced like childhood trauma or … different trauma from the workplace. And it feels like it’s a word that’s used quite a lot.’ [P5]

Service users themselves can struggle to recognise trauma-related symptoms, complicating assessments further:

‘Do they know they are experiencing some kind of trauma symptom? … some others that don’t even know that they are experiencing some kind of trauma.’ [P6]

Inconsistent process for assigning problem descriptors

Reported decision-making processes for trauma-related problem descriptors varied widely between participants. Some PWPs believed that choice of problem descriptor should be led by patients:

‘I think I would still be led by the patient and choose the problem descriptor that I think matches their sort of presentation, their goals, what they want to focus on.’ [P8]

Others felt dependent on measures that identified symptoms concretely:

‘Maybe I’ve done the PCL-5 [PTSD measure] with them and that, sort of, is scoring in caseness … then I would put PTSD as the problem descriptor there.’ [P7]

Some believed supervisors should decide whether trauma-related problem descriptors were appropriate:

‘I personally … would not put trauma as a descriptor unless my supervisor said to do that.’ [P2]

Beliefs that handling traumatic events was unfeasible for PWPs were managed differently by different participants. Some attempt to conceptualise issues workable at Step 2:

‘If they have traumatic events from the past and it doesn’t actually seem like PTSD, I suppose my go to is … what step 2 problem does it associate with? I would probably just fall back on that … ’cause I don’t think trauma is just one that we can put on the problem descriptor.’ [P7]

Others defer to Step 3:

‘I don’t think I’m qualified enough to say, is this trauma appropriate for IAPT [NHS-TT] or not? … I think it’s so good that it’s ran by those Step 3 therapists and not just left to us to decide.’ [P9]

Not treating PTSD makes assessing for it harder

Assessing for PSTD in a role not designed to treat it presents significant challenges:

‘I didn’t know necessarily what questions to ask … We’re trained to an extent how to assess PTSD and trauma, but obviously we’re not trained in how to treat it … I also don’t necessarily know how that treatment’s going to look for them either.’ [P5]

Some felt they lacked sufficient understanding of PTSD to assign its problem descriptor:

‘I don’t feel very confident putting a PTSD descriptor on because I can’t diagnose that or assess that really because I don’t treat it.’ [P4]

A perceived lack of training leaves PWPs feeling underprepared

Describing formal and in-service training interchangeably, various participants shared beliefs that they were not sufficiently prepared to conduct assessments of traumatic events. PWPs felt that training did not address distinctions between PTSD and other trauma problems:

‘In the training, they didn’t really mention anything between like the differences between trauma and PTSD … So you do feel a bit left in the dark.’ [P5]

PWPs also sought guidance in balancing patient boundaries with the accumulation of necessary information:

‘How much do I explore that area? That trauma for that patient when they’re saying … it’s not relevant … we haven’t had specific training in that.’ [P2]

Overall, some relayed that their training on assessing traumatic events had been scant:

‘I think in those 2 years there’s only been one instance of PTSD training that I remember.’ [P9]

Knowledge regarding assessment of traumatic events stemmed from learning gained while working, rather than from formal training:

‘In assessing traumatic events … I don’t think we necessarily went over anything with that in training, even recognising … I think that’s something we’ve made picked up from service.’ [P7]

Such experiential learning contributed to feeling under-prepared, especially given PWP roles are typically junior:

‘It does feel like there’s almost a bit of a gap there, I suppose. Where we’re sort of thrown in to the deep end.’ [P5]

Assessing traumatic events is emotionally overwhelming

Assessment of traumatic events were consistently described by participants as an emotionally overwhelming experience.

Assessment calls involving trauma invoke intense emotions

PWPs described a multitude of powerful emotions following assessment calls:

‘I do feel quite drained … can feel a little bit down as well because it’s not the nicest thing to hear.’ [P10]

The emotional weight of being the first to hear disclosure of traumatic experiences is particular to such assessments:

‘Some patients have come to me and disclosed that I would be the first person that they’ve ever disclosed this information to … It’s upsetting to feel that, you know, they’ve gone through this and I’m the only person that they’ve ever spoken to.’ [P10]

Some ruminated upon service users’ circumstances:

‘I think you can’t help but think about this person’s sort of life picture.’ [P8]

Memories of such assessments caused physical distress:

‘Two years ago … I can still feel it now. I could just feel something in my stomach.’ [P3]

Not being able to help some service users invoked frustration and disillusionment:

‘I’m aware of the limitations of low intensity CBT, so I think it it’s almost a bit disheartening in a way because I know that myself as an individual, I can’t make a difference to that person in terms of treatment.’ [P2]

Supressing emotional reactions

Various participants detailed their suppression of emotional distress caused by assessments of traumatic events. For some, such suppression was practically necessary:

‘You have to put your feelings aside for a minute to focus on your next patient. Because sometimes you just don’t have that time to deal with your own emotions.’ [P10]

Often, time constraints perpetuate avoidance of processing such distress:

‘I guess the reality is … you normally just say oh yeah fine, because you don’t have enough time in case management supervision to discuss about half your patients anyway.’ [P5]

Lingering emotional impacts

Such assessments can lead to adverse emotional effects for some PWPs. These include carrying traumatic events in memory for months due to their emotional intensity:

‘Even now a year on, I can recall a good amount of cases that have had traumatic events … that’s how traumatic they were.’ [P10]

Difficult memories can lead to PWPs feeling nervous when trauma is mentioned in future assessments:

‘If they pull it out quite early, then I guess I’m a little bit more tense as to what are they gonna talk about next.’ [P2]

Or struggling to empathise with other patients who are experiencing less intense issues:

‘It’s more Step 2 straightforward cases, I might struggle with the empathy more because I’ve given it for the other more difficult ones and those just become a bit more routine.’ [P1]

Desensitisation

Participants described becoming desensitised to discussion of traumatic events following multiple assessments of such:

‘I think as the role [progresses] you do get desensitised; you get used to hearing quite unpleasant things. Quite quickly.’ [P1]

Some view such detachment as positive, conceptualising it as evidence of resilience:

‘To an extent it’s good, it’s almost like if you’re … if you were to take a lot of that with you to the next call, it might impact how you go through with the next call. So, in that sense it can be quite helpful.’ [P11]

Others found themselves numbed in their personal lives:

‘I guess it comes back to the desensitisation thing … when I’m like watching a film or something or hear on a telly program that people have been through these traumatic events, I almost feel like I’m not as shocked by it.’ [P5]

Personal distress compounds professional stress

Some participants’ personal and professional difficulties impacted one another. Such impacts could directly complicate assessment of traumatic experiences.

Assessments added to personal strife:

‘If you have difficult times in your personal life, it … just adds to any personal stress.’ [P8]

Personal issues made assessments more difficult:

‘There are other times where maybe you come to work, and you haven’t had a particularly good day or there’s other things going on in your life … and then you get hit with this … hearing these traumatic things.’ [P5]

Various participants reported imagining themselves in similar situations and becoming distressed at such a prospect:

‘The thought oh God, what if this happened to me or someone I cared about, that will cross your mind, that thought.’ [P6]

Many felt that they took assessments of traumatic events home with them more than they would other assessments:

‘It’s probably on those days that I’d … think more about work maybe when I went home.’ [P11]

Ultimately, assessing service users that reported traumatic events changed the way that some PWPs engaged with the world:

‘I barely read the news because I always say that I hear enough depressing stuff during my workday … kind of taking on some of that.’ [P1]

Assessing traumatic events is pressurising

Multi-faceted, relentless pressure was described by participants throughout the dataset. Time limits complicated assessments for PWPs:

‘When it comes to assessing trauma, given everything else we also have to explore, that can become quite tight timing wise. And often the appointments will need to overrun if you’re going to gather sufficient information.’ [P1]

Such constraints sometimes prevented PWPs from self-care following difficult assessments:

‘I take a step away, get a cup of tea or give myself a breather before having to jump on the next call. But you know, it’s trauma that sometimes can be coupled with complexity or risk. Sometimes that wasn’t an option and you had to immediately be responding to it.’ [P1]

Calls involving risk to service users further can add further pressure to PWPs during assessments featuring traumatic events:

‘I would say we’re probably trained not to panic, but … I need to, sort of, follow as many steps as I can remember in that sort of chaotic moment … You feel that pressure to … remain calm.’ [P8]

These constraints were suggested to affect PWPs performances of their roles:

‘It can sometimes feel … a bit muddled as well because you … weigh up, in the short amount of time that you’ve got, you know, what do I concentrate on?’ [P8]

Participants contextualised relentless pressure within NHS-TT’s focus on meeting service-wide targets:

‘You don’t have that space to destress … It’s just, having these targets you have to meet per day.’ [P9]

In-service support is invaluable

The camaraderie, guidance and comfort of colleagues was regularly depicted as central to PWPs’ experience of assessing traumatic events.

‘You’ve got people you can turn to’

Informal peer support during and after assessments of traumatic events was consistently described. Fellow PWPs provide mutual understanding to one another:

‘Sometimes just getting that off your chest that really helps and having that sort of supportive person who knows what it’s like because they probably experienced the same.’ [P11]

Training in cohorts creates a sense of solidarity:

‘I think just the natural fact that you train in cohorts … you’ve got people you can turn to, other people are going through the same experience of “I don’t know what I’m doing” at the same time.’ [P1]

The invaluable nature of peer support in crisis situations was also described:

‘When my colleague had a sort of active, you know, someone … tried to end their life … I could go and find a Duty worker in the building to come over and support with that.’ [P8]

‘Feeling that you’re not supported is not a good place to begin’

Such experiences contrast with some PWPs’ experiences of isolation, whether working from home or on-site. Participants described distance from colleagues as a barrier to accessing impromptu emotional support:

‘I’ve always got the option to like work from home … but I’ve always thought that it’s better for me to be here and be around people.’ [P3]

In an expanding service, some PWPs described being physically isolated while on-site, and the additional stressors this can present:

‘If you’re working where there aren’t many people in the office or you’re at home, that can sometimes be more difficult because you’ve gotta rely on … finding teams yourself.’ [P8]

Some PWPs described assessments as beginning with a sense of isolation in the face of uncertainty; a sense that such assessments were struggles they faced alone. Such feelings can make assessments emotionally difficult from the offset:

‘When we answer the phone, we don’t know what someone’s experience is gonna be. Starting that with uncertainty and feeling that you’re not supported is not a good place to begin.’ [P2]

A sense that more space could be cultivated in-service to support PWPs feeling isolated was felt:

‘Give more of a space for people to be able to talk about that … It’s encouraging people to speak up if they’re struggling. I guess you never know who you’re gonna speak to, what problem are they going to present with? It’s just encouraging people to ask if they need support.’ [P3]

Supervisors shape PWPs’ emotional experiences

The quality of support provided by supervisors was also recognised as a pivotal variable by participants:

‘I think supervisors are an incredibly important part of your experience. And if you have one that isn’t quite working so well, then that has a huge impact on the day-to-day work … But I think if it’s all working then that support is there.’ [P1]

Equally, substandard supervisory experiences compounded the emotional challenges of assessing traumatic events. These included focusing on case management without fully acknowledging PWPs’ emotional needs:

‘[My] supervisor was like … must have been difficult for you … And then on to the next one. Yeah, it was quite quick. I might not have spoke about as much as I would have liked.’ [P3]

Or having their own stress compounded by supervisors’ stress:

‘Like you can tell when someone’s really stressed … particularly if that person is a supervisor … they’re there to support the people that are lower down and if they’re not there and present, how am I being supported?’ [P2]

Similarly, the wider Talking Therapies system was regarded as a pivotal emotional support in the context of assessing traumatic event. Informal support from Duty was appreciated:

‘If a case has been difficult, if you wanted to talk through with someone from Duty, there is that option … they’re often able to recognise that this was not an easy call for you to go through.’ [P1]

Instances in which senior staff members were perceived as emotionally invalidating compounded PWPs’ emotional duress:

‘They’ve approached all of the people in senior management … they feel like they’ve been fobbed off and told to suck it up and get on with it.’ [P2]

However, a sense of support throughout the system was also reported:

‘I feel like you can speak to anyone you know however senior they are.’ [P8]

Discussion

This study aimed to explore PWPs’ experiences of conducting assessments involving discussions of traumatic events within an NHS-TT service, and to develop an understanding that may contribute to service and PWP training improvements. The study was designed collaboratively with the participating NHS-TT service’s research team. Following this study, recommendations regarding service adaptation were made to the service (see Supplementary material).

Factors important to improving service

Participants highlighted difficulties in identifying appropriate problem descriptors for many patients that reported experiencing traumatic events, inconsistencies in how such descriptors were identified, and the challenging nature of recognising a problem that they themselves were not qualified to treat. These represent novel findings within NHS-TT research. Awareness of the specific processes complicating assignment of appropriate problem descriptors is particularly pertinent given findings that identification of problem descriptors in NHS-TT achieves better clinical outcomes (Clark, Reference Clark2018; Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Cape, Leibowitz, Aguirre, Jena, Cirkovic, Wheatley, Main, Pilling and Buckman2020).

Participants identified knowledge gaps regarding trauma, PTSD and the distinction thereof, and noted that their experiences of learning experientially created a sense of unpreparedness in assessing trauma-related problems. Such findings substantiate Murray (Reference Murray2017)’s recognition of NHS-TT therapists’ minimal training in working with trauma-related problems and NHS-TT’s efforts to disseminate training programmes specifically designed to develop staff understanding of trauma problems.

Participants described how assessing trauma-related problems could produce long-standing emotional impacts, exacerbated confluences between personal and professional distress and occasionally result in emotional detachment. These descriptions are consistent with a growing body of research depicting NHS-TT staff’s experience of burnout, compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Crouch-Read, Smith and Fisher2021) and, in turn, the overall experience of working in psychological professions (McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, MacIntyre, O’Shea, Herring and Campbell2018).

While research consistently illustrates the PWP role as pressurised, this study provided novel findings regarding the pressures experienced whilst assessing trauma. Supplementary processes such as safeguarding, implementing disorder-specific questionnaires and gathering information with appropriate sensitivity were described as burdensome for PWPs. Additionally, feelings of isolation amidst such pressures that PWPs can experience working remotely are worthy of further research.

Participants highlighted the importance of peer relationships, supervisors and on-call duty clinicians as support structures when assessing traumatic events. Such findings corroborate those of Harper et al. (Reference Harper, Bhutani, Rao and Clarke2020). However, insight into the specific benefits of peer support following PWP assessment of traumatic events are novel, as are those identifying duty supervision as valuable support.

Dissemination of results

Findings were shared with the NHS-TT service’s clinical leadership team. A joint meeting was held with the service to discuss key findings and recommendations and an executive summary of the study’s findings was produced and shared with staff. It has been planned that this study’s findings would be disseminated with the wider staff team before provision of training based on this study’s recommendations.

Limitations

Given that this study relied on PWPs using their limited spare time to participate, it is possible that a sampling bias led to more polarised feedback in the data. Furthermore, only staff views were represented in discussing assessments featuring traumatic events; service user perspectives on such assessments were beyond the scope of this study but would doubtlessly contribute valuable insight to inform service recommendations.

Key practice points

-

(1) Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners (PWPs) can find it more difficult to identify the main clinical problem in assessments that include discussion of traumatic events.

-

(2) PWP training courses should consider providing further training on discussing and assessing traumatic events and identifying PTSD. NHS-TT services could consider offering additional training on these topics.

-

(3) Assessments featuring traumatic events can have long-standing emotional repercussions for PWPs. Supervisor training on such assessments could help supervisors’ provision of restorative emotional support to PWPs.

-

(4) Assessments featuring traumatic events often involve supplementary tasks that add substantial pressure to PWP workloads.

-

(5) Peers, supervisors, duty supervisors and the clinical leadership team shape PWPs’ emotional experience.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X25000170

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Oxford Institute of Clinical Psychology Training and Research for their facilitation of this research. Gratitude must also be expressed to each participant.

Author contributions

John Kerr: Conceptualization (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Writing - original draft (lead); Hjordis Lorenz: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing - original draft (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Samantha Sadler: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Resources (supporting), Software (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Victoria Roberts: Conceptualization (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (supporting); Craig Steel: Supervision (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Graham Thew: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting).

Financial support

This project is supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

Graham Thew is as Associate Editor for the Cognitive Behaviour Therapist. He was not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which he is listed as an author. The remaining authors have no competing interests related to this publication.

Ethical standards

Authors abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BPS and BABCP. Ethical approval was not required for this research, according to the NHS Health Research Authority Tool (Health Research Authority, 2025). The project was approved by an NHS Clinical Audit department, and ethical oversight throughout the project was managed through the service’s AMaT (Audit Management and Tracking) system. Participants provided informed consent to participate and for results to be published.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.