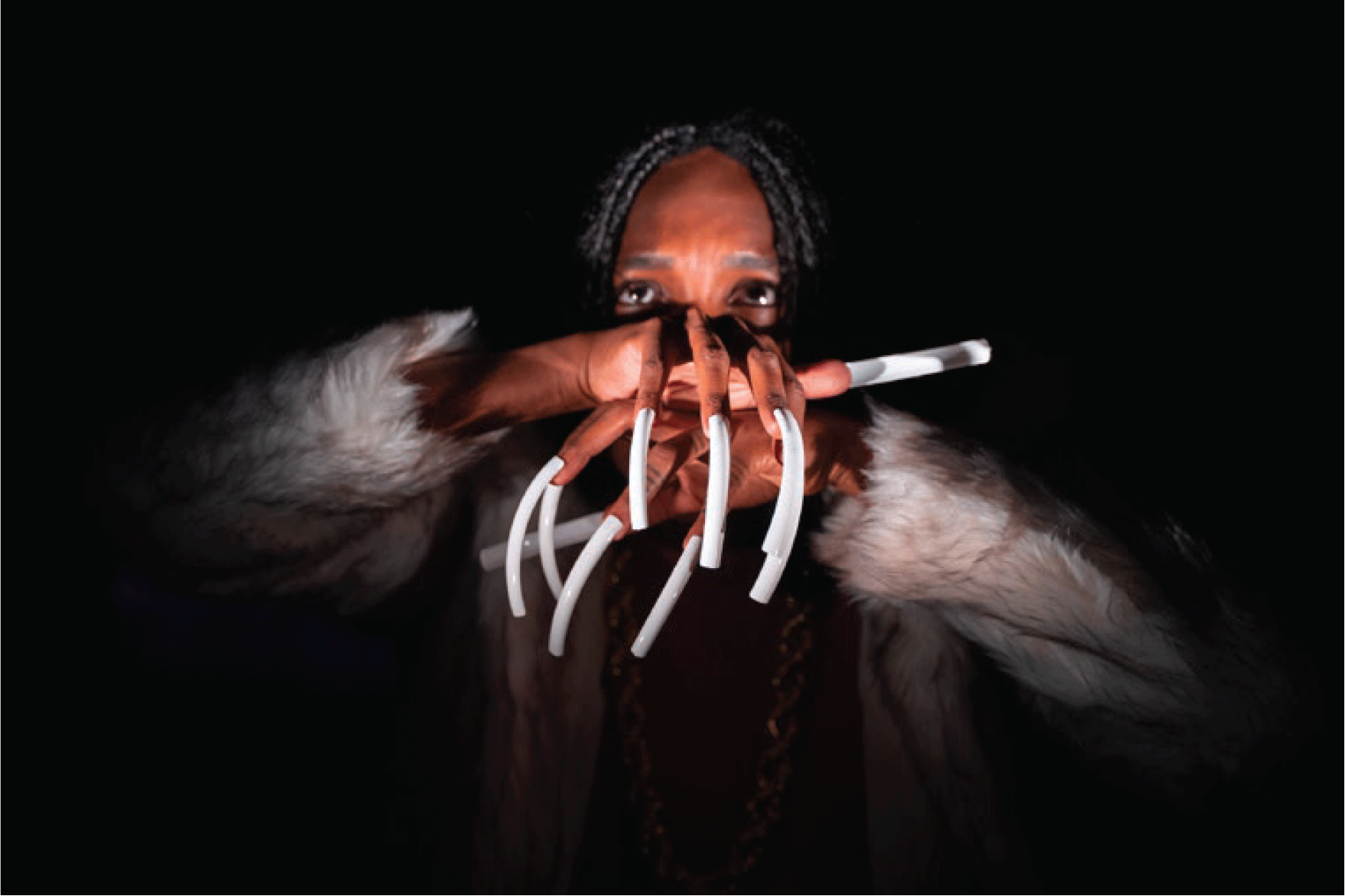

Figure 1. Cherish Menzo is a “video vixen” in Jezebel (2019), choreography by Cherish Menzo. Frascati, Amsterdam, 5 September 2019. (Photo by Bas De Brouwer)

Jezebel and Darkmatter

Can you hear the explosion

Of voices from the ocean

Songs full of emotion

From a time without a notion

—Camilo Mejía Cortés (Darkmatter 2022)While just at the outset of her career as a choreographer, Cherish Menzo has already solidified her presence as a significant voice in the European dance scene. She has garnered multiple international awards and embarked on tours across Europe and North America. Menzo graduated in 2013 from the Urban Contemporary program (Jazz and Musical Dance) at the Amsterdam University of the Arts. Following her graduation, she danced in pieces by Lisbeth Gruwez, Jan Martens, Nicole Beutler, Akram Khan, Olivier Dubois, Benjamin Kahn, and Eszter Salamon. During this period, she also began to create her own work. In 2016, she collaborated with Nicole Geertruida to create EFES, an energetic choreography exploring themes of perfection and fallibility. Two years later, she developed Live, a collaborative project with musician Müşfik Can Müftüoğlu that blurs the lines between a dance performance and a pop/rock concert. The pieces that truly brought her recognition as a choreographer, however, were Jezebel (2019) and Darkmatter (2022), two pieces that critically explored the racial and gendered constructions that surround the black body.

The solo performance Jezebel premiered in 2019 at Frascati Amsterdam.Footnote 1 The piece, created and performed by Menzo, takes the figure of the “video vixen” as its starting point. Also known as “hip hop honeys,” video vixens were black women and women of color who featured in rap and hip hop music videos during the 1990s and 2000s (Balaji Reference Balaji2010:9). Typically characterized by their curvaceous figures and revealing attire, these women were portrayed as alluring, seductive, and sexually available. As former video vixen Amber Johnson argues, the video vixen “personified sex” (2014:182). As such, their main role in the music video industry, in which sex is known to sell, was to serve as “eye candy” to enhance the popularity of the music video and the lead artists (Sharpley-Whiting 2007; Balaji Reference Balaji2010). In her performance, Menzo draws a connection between this hip hop phenomenon and the “Jezebel,” one of the primary stereotypes used to define black women, especially during the slavery era in the US (Jewell Reference Jewell1993; White [Reference White1985] 1999).Footnote 2 Similar to the video vixen, the Jezebel is depicted as a purely sexual being, an inherently promiscuous seductress “almost entirely governed by her libido” ([1985] 1999:29). By directly linking the figure of the Jezebel to that of the video vixen, Menzo illustrates the ongoing hypersexualization of the black female body. Menzo’s performance, however, goes beyond a critical deconstruction of the video vixen-cum-Jezebel archetype. Reflecting on her own teenage fascination with video vixens, Menzo explores this figure’s potential for empowerment. Her aim is not only to expose the video vixen as a prime example of the continued sexual exploitation of the black female body but also to craft a “futuristic image” of this figure, reimagining the stereotypes that surround her and enabling her to reclaim and redefine her identity and sexuality (in De Zendelingen Reference Zendelingen2020).Footnote 3

Dressed in pink hot pants and crop top, a white fur coat, and white Nike Airs, and piloting a lowrider bicycle, Menzo’s stage appearance embodies the cliché of the video vixen. As in the video clips, she dances seductively, twerking, crawling on the floor, and thrusting her hips side to side. Despite these obvious references to the video vixen, however, we cannot reduce Menzo’s stage performance to this hip hop stereotype. As dance critic Charlotte de Somviele observes, something about Menzo’s performance defies such a simplistic characterization:

Yes, she twerks, but just until it becomes an abstract drill. Yes, she has fake nails, but they are so long they look more like claws. Yes, she raps, but in the form of unintelligible gibberish. This jezebel […] is elusive, rebellious, and quite intimidating. (Somviele 2020; emphasis added)Footnote 4

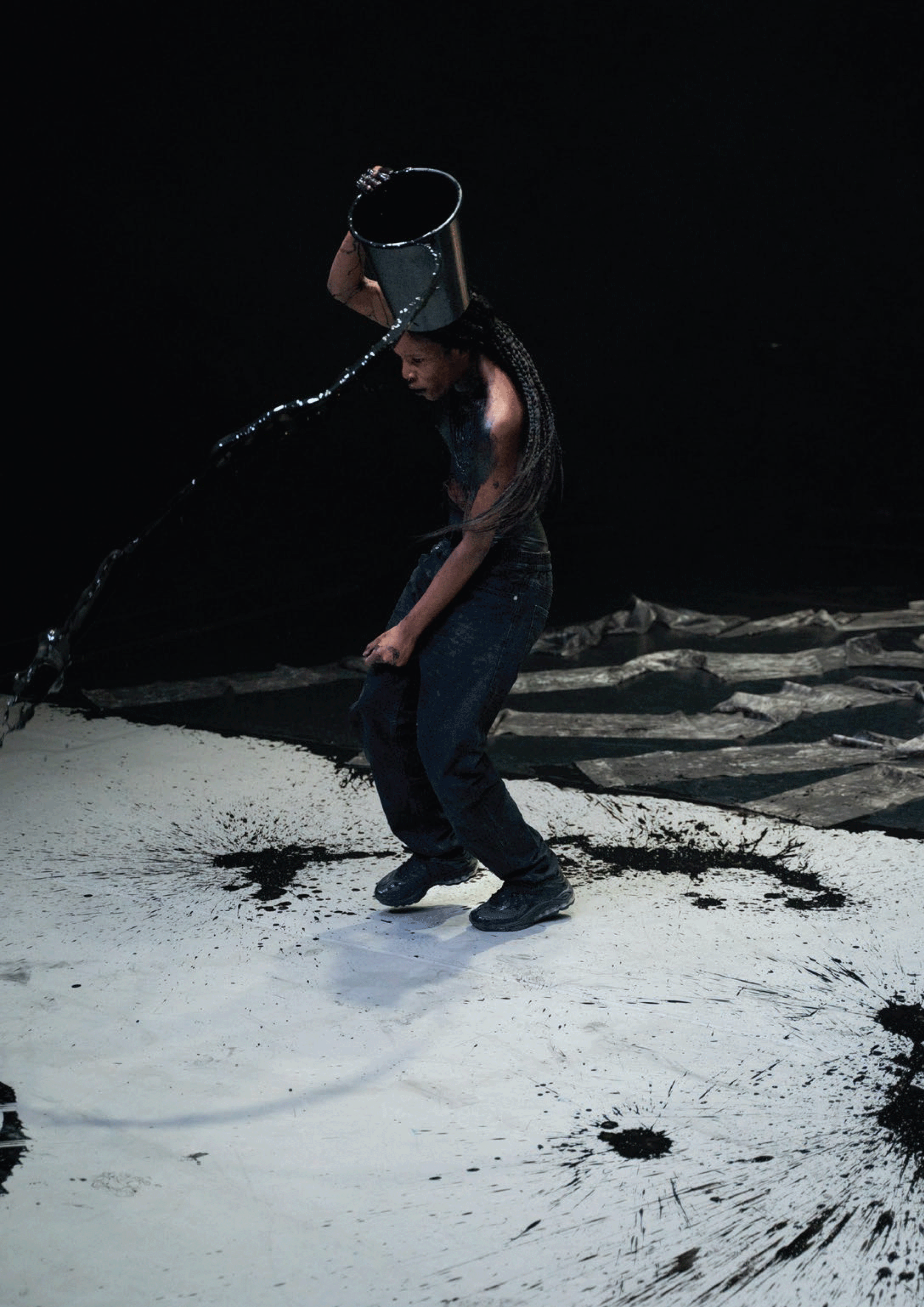

Figure 2. Cherish Menzo with her long white nails—a fantastic beast or a futuristic cyborg—in Jezebel (2019), choreography by Cherish Menzo. Frascati, Amsterdam, 5 September 2019. (Photo by Bas De Brouwer)

Menzo’s video vixen does not behave as expected. Her movements are over the top, out of the ordinary, and out of place. Throughout the performance, she transforms from a “pretty little thing” into an “uncanny character that continuously blurs the boundaries between man, woman, animal, video vixen and rapper” (in De Zendelingen Reference Zendelingen2020).Footnote 5 Early in the piece, Menzo squats at the center of the stage, intertwining her fingers and positioning them in front of her mouth. Adorned with long white fake nails, the fingers cover her mouth completely, making her appear like a fantastic beast with teeth sticking out of the side, or a cyborg-like entity wearing a futuristic breathing device; I thought of the villain Bane in the Batman comics. As Menzo starts moving her fingers and hands, subtly at first but progressively expanding in scope, new figures come into focus, all straddling the line between the mythical and the futuristic. After a while, Menzo removes her hands from her face and starts moving her mouth and tongue. Again, we see her transforming from a sex symbol into an uncanny creature. Initially, Menzo sensually licks her lips and pushes her tongue against her cheeks, alluding to fellatio. The tongue movement continues until the sexual connotations recede and the tongue is an independent entity, a worm-like parasite invading Menzo.

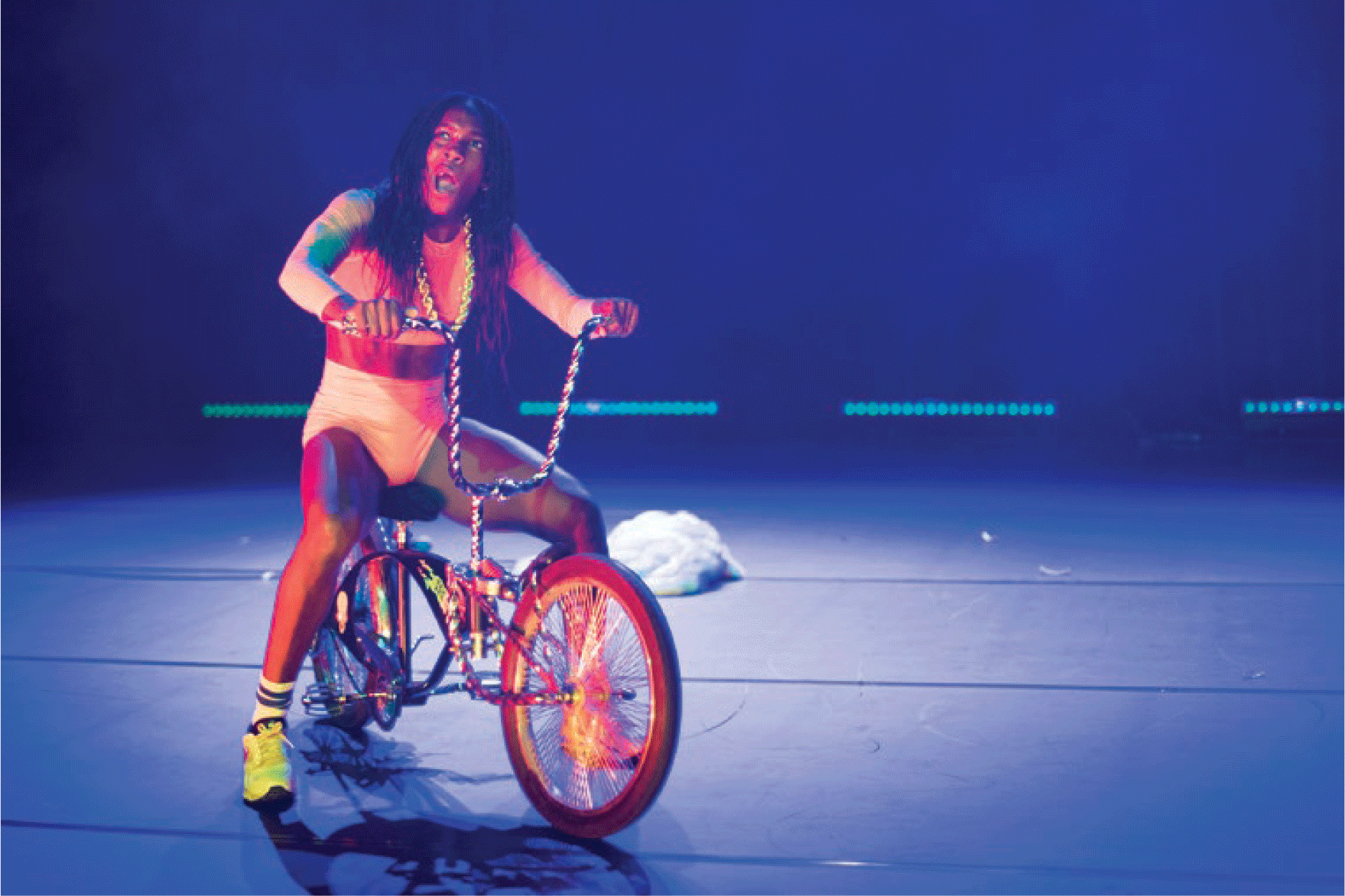

Figure 3. From left: Camilo Mejía Cortés and Cherish Menzo, smeared with the tar-like black liquid in Darkmatter (2022), choreography by Cherish Menzo. Beursschouwburg, Brussels, 12 May 2022. (Photo by Bas De Brouwer)

These continual processes of transformation allow Menzo’s vixen to embody what Carla Peterson calls an “empowering oddness,” a form of “eccentricity” that eludes the narrow representational frameworks of the video vixen—and the black female body in general—thus creating “freedom of movement” (2000:xi–xiii). This is also why de Somviele characterizes Menzo’s video vixen as intimidating (Somviele 2020). She is emancipating herself, reinventing her identity, and forging new pathways to explore black female sexuality beyond traditional frameworks.

With Darkmatter Menzo continues to disturb the signifying chains of race, sexuality, and gender that surround the black body, and her explorations of the performative modes that activate this body differently.Footnote 6 The piece, which was conceptualized and choreographed by Menzo in collaboration with performer Camilo Mejía Cortés, looks for ways to detach black bodies “from the way they are perceived and the daily reality in which they move” (Menzo Reference Menzo2022). Instead of anchoring their performance in historical stereotypes, Menzo and Cortés look into the future. Building on ideas and concepts from posthumanism and Afrofuturism, they create an uncanny and eerie performance in which they stage themselves as undefinable creatures roaming a futuristic and dystopic landscape. The opening image immediately sets the tone. Upon entering the theatre, the audience is confronted with two figures standing at the front of a stage engulfed in fog. A soft rumbling sound is heard in the background. Both figures wear face-covering masks made from reflective material, resembling space travelers or extraterrestrial beings. One figure lies on its back, its bare chest smeared with a black, tar-like substance, while the other is on its knees, hovering over the reclining figure, touching the smeared skin with its hands. The nature of their actions remains ambiguous. Are they performing a surgical procedure, a ritualistic burial ceremony, repairing a bionic body part? After a couple of minutes, the light gradually dims, closing on the two performers. The reclining figure gets up and dons a black sweatshirt. Together, they slowly step into the darkness.

As in Jezebel, the images and figures conjured up in Darkmatter are elusive. Menzo uses the theatrical apparatus to its fullest to develop myriad tableaus, ranging from the desolate opening image described above to scenes that exude a club-like vibe. Deploying costumes, props, and scenographic elements, both performers repeatedly change their appearance. In the second half of the performance, for example, both performers are bare-chested, wearing only spandex hotpants and latex high-heeled boots that reach their thighs. At first, their appearance evokes a fetishistic imaginary. Through a lighting change, they suddenly look like minotaur-like creatures moving through a mythical landscape.

Layering all these images, references, and textures, the piece creates an experience of “spectacular opacity” (Brooks Reference Brooks2006:8). As Daphne Brooks argues, spectacular opacity invokes excess as a strategy to resist the conventional construction of blackness within Western culture, demonstrating “the insurgent power of imagining cultural identity in grand and polyvalent terms which might outsize the narrow representational frames bestowed on them” (8). Similarly, the semantic and affective excess staged by Menzo signals a refusal to be confined or pigeonholed by narrow cultural norms.

The black, viscous, tar-like substance in the opening scene is a recurring motif and a conceptual lens for looking at the piece. At various junctures in the performance, Menzo and Cortés “vomit” the pitch-black liquid, which they must have held in their mouths from the beginning of the performance, and in the second half of the performance they pour full buckets of the inky liquid onto the stage, covering it entirely with the oily substance. The performers also become one with the substance. Not only in a literal sense, as they are increasingly covered with it, but also figuratively. Like the substance, they become malleable, transforming into a fluid form or “dark matter” that distorts the customary frames employed to represent the black body. In doing so Menzo and Cortés aim to set the stage for what they describe as “the birth of a new (afro)futuristic and enigmatic body” (Menzo Reference Menzo2022).

Both Jezebel and Darkmatter do not merely critique the cultural construction of black and gendered bodies; they actively seek to disrupt and transform these constructions. Menzo is not only interested in unveiling the historical underpinnings of racism shaping the portrayal of the black body in mainstream culture but also aspires to transform these depictions and create, or fabulate, new narratives for them. She wants to create a “futuristic image of the video vixen” (in De Zendelingen Reference Zendelingen2020); a “new (afro)futuristic and enigmatic body” (Menzo Reference Menzo2022). In Paul Gilroy’s terms, we can define this strategy as a “politics of transfiguration” (1993:37). Gilroy distinguishes two types of politics in black activism and culture: the politics of fulfillment and the politics of transfiguration.Footnote 7 The politics of fulfillment emphasizes the discrepancy between claims of equality and equity made by Western societies and the continued existence of systemic racism. Proponents of the politics of fulfillment demand that “bourgeois civil society live up to the promises of its own rhetoric” (37). On the other hand, the politics of transfiguration develops a “counterculture that defiantly reconstructs its own critical, intellectual, and moral genealogy.” Whereas the politics of fulfillment is a discursive practice firmly embedded in the political domain, the politics of transfiguration is a creative endeavor, creating “qualitatively new desires, social relations, and modes of association” (37).

Chopped and Screwed

Chopped and screwed is a musical style that originated in the Houston hip hop scene in the early 1990s, providing an ideal sonic backdrop for a city known for its scorching summer heat and car culture centered around the “slab” (an acronym for slow, loud, and banging). A slab, Houston’s take on the lowrider, is a customized American car that is made to cruise the streets at around 40 miles per hour (Petrusich Reference Petrusich2014). Named after its innovator, DJ Screw, the hip hop style incorporates two distinct techniques: chopping and screwing. Screwing involves intentionally slowing down the playback speed of a recording. It takes mainstream hip hop and R&B tracks, typically set at 100 beats per minute, and reduces their tempo to a range of 60 to 70 beats per minute, transforming both the tempo and pitch of the record (Sinnreich and Dols Reference Sinnreich, Dols and Christopher2022:120). Chopping refers to a specific sampling technique that generates new sonic and rhythmic textures by fragmenting or “chopping up” records. While sampling is a fundamental element of virtually all hip hop styles, chopped and screwed develops a unique approach in which beats are strategically repeated and rearranged to create sonic glitches and syncopations that unsettle the musical flow (Sinnreich and Dols Reference Sinnreich, Dols and Christopher2022:120). One example of this chopping technique is the repetition of vocal phrases or other musical elements through phasing or phase shifting. This compositional process, often used in minimalist music, brings two or more identical musical lines in conjunction by playing them simultaneously but slightly out of sync. In the context of chopped and screwed, this sonic experience is achieved by spinning the same record on two turntables, with one a beat behind the other, and toggling a crossfader (Petrusich Reference Petrusich2014). Combined, the techniques of chopping and screwing produce a distorted and often hypnotic auditory experience that critics have described as “oceanic,” “woozy and immersive, elastic and gummy” (Caramanica Reference Caramanica2010), or as a “gauzy dream” (Strew Reference Strew2022).

Figure 4. Cherish Menzo with a bucket of the viscous black substance that covers the stage in Darkmatter (2022), choreography by Cherish Menzo. Beursschouwburg, Brussels, 12 May 2022. (Photo by Bas De Brouwer)

Chopped and screwed not only brings a distinct sound to hip hop, and arguably to pop music at large,Footnote 8 but also introduces a novel approach to manipulating time. DJ Screw’s oozy sound textures and syncopated rhythms disrupt the listener’s conventional sense of time, creating a temporal experience that is at once stretched out and compressed. These temporal experiments align with the broader project of hip hop music, which takes “hijacking time as a central aesthetic” (Sloan et al. Reference Sloan, Harding, Gottlieb, Sloan and Harding2020:93). Blending different records and reappropriating fragments of older tracks through sampling techniques, hip hop DJs consistently manipulate time and duration (Christopher Reference Christopher2022:12). Yet, even within a genre known for temporal experimentation, chopped and screwed takes a radical stance. It not only introduces sonic elements that challenge the listener’s sense of regulated temporality but pushes time itself to its limits. Chopped and screwed unsettles the flow of time, causes it to dissipate and to lose its sense of pace and direction. As such, it introduces timelessness, making “moments feel eternal” (Pearce Reference Pearce2017). As cultural critic Jia Tolentino argues, chopped and screwed, with its “skip beats and stutter,” makes you feel “like your heart is about to stop” (2019:136).

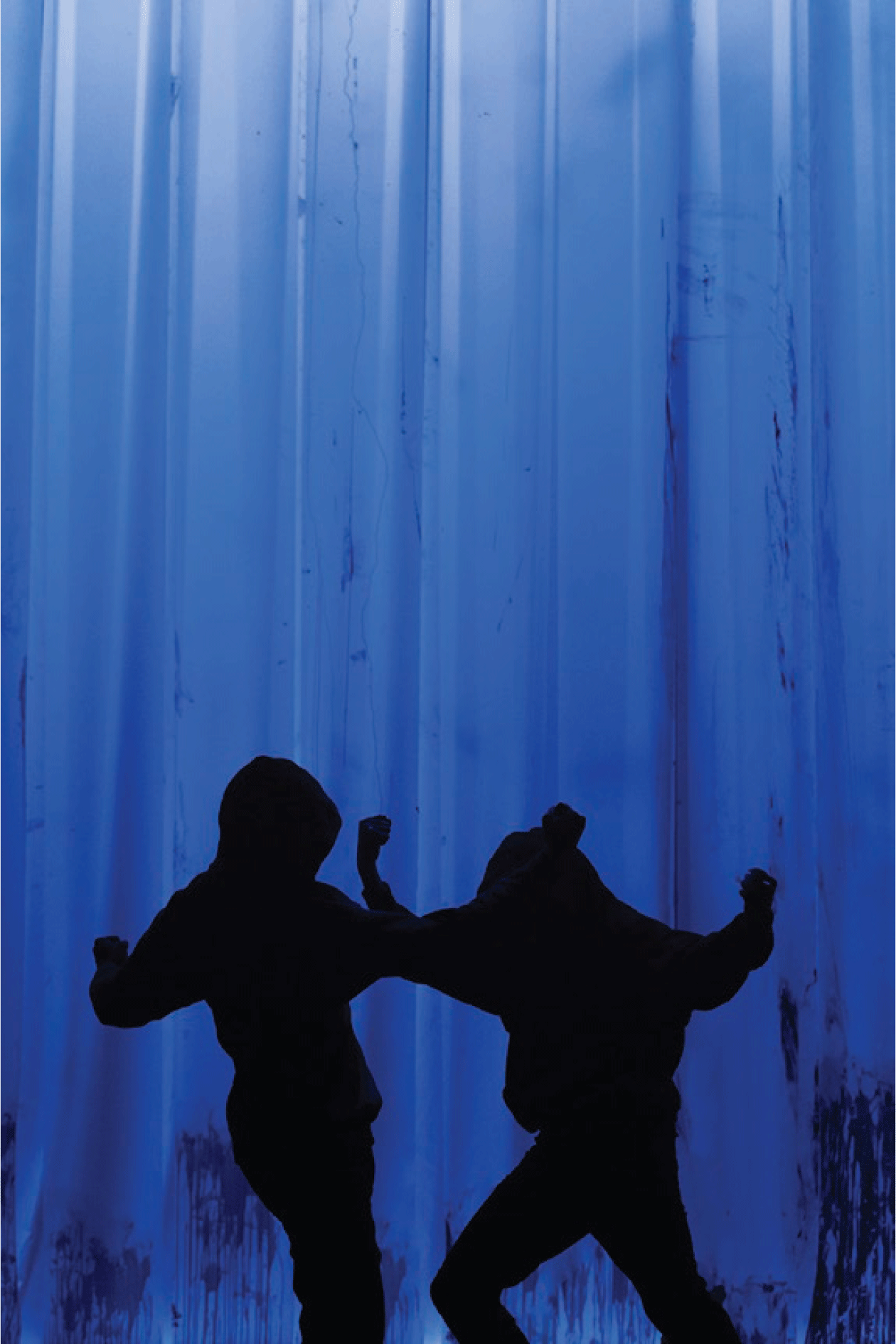

Chopped and screwed plays an important role in both Jezebel and Darkmatter. In Jezebel, it is mainly used as part of the soundscape. The first reference to the musical genre comes about 25 minutes into the performance. Lying on the floor, Menzo starts singing “Oochie Wally” (2001) from the New York–based hip hop group Bravehearts. In the beginning, the song is barely recognizable, as Menzo performs a slowed-down version of the song, and her voice is pitched down, resulting in an uncanny, robotic sound. After a while, it becomes clear that Menzo is performing an adapted version of an existing song, and the attention shifts from the sound textures to the explicit and aggressive lyrics of the song, which are also projected on the backdrop. By slowing down the tempo, Menzo dissolves the catchy melody, shifting focus to the words. The chopped and screwed musical style appears again in the second half of the performance. Midway through, accompanied by a thumping rhythmic track, Menzo starts to move energetically, almost frantically. Five minutes into this scene, when she is lying on the floor nearing exhaustion, the musical track suddenly slows down and transitions into a chopped and screwed version of Jay-Z’s “Big Pimpin’” (2000). During the transition, which is visually marked by a cloud of smoke that covers half the stage, Menzo steps on her lowrider bicycle and rides it slowly across the stage.

At some moments, Menzo also experiments with adapting the chopped and screwed technique to her choreography, creating oozy and elastic movements. An example of this is in the “Big Pimpin’” scene, described above. While Menzo is riding her bike across the stage, she lip-synchs Jay-Z’s lyrics. Her facial expression matches the mellow quality of the music and is projected in close-up on the back wall. Like in the song, her exaggerated movements are slowed down, drawing attention to the materiality of the movement rather than its meaning.

Figure 5. Cherish Menzo on her lowrider bicycle in Jezebel (2019), choreography by Cherish Menzo. Frascati, Amsterdam, 5 September 2019. (Photo by Annelies Verhelst)

While Menzo experiments with applying the chopped and screwed technique to movement in Jezebel, this feature really comes to the fore in Darkmatter, where it is not only used to develop the soundscape but also as a central tool to generate a specific movement quality (Menzo Reference Menzo2022). Twelve minutes into the performance, after the opening scene and a series of still images separated by blackouts, the lights come back on, and we see Menzo and Cortés standing close to the backdrop, a curtain of see-through plastic strips. In the backlight, we can only see their silhouettes. They dance like they would in a club, standing close and taking cues from each other. However, the dancing is very slow, adding to the mellow, oozy experience of chopped and screwed. This is amplified by the sound score, comprising fragments of William Grant Still’s opera Troubled Island (1949), which fades in and out over a low, droning chopped and screwed soundscape. The effect is of a hazy dream, as if the performers are dancing behind a veil or underwater, part of a world far removed from the spectator.Footnote 9

In a conversation with me, Menzo expanded on the development of chopped and screwed as a choreographic methodology. Similar to the musical style, the movement brings together techniques clustered around screwing and chopping. Menzo defines screwing as “slow time,” or the “slowing effect” (Menzo Reference Menzo2023). Screwing, however, should not simply be understood as slowed-down movements. Taking inspiration from hip hop’s turntable culture, Menzo connects screwing to the physical movement of the needle as it passes through the grooves of the vinyl record. Menzo and Cortés use this idea to develop circular movements, without a beginning or end, and to look for ways to torque certain parts of their bodies. Simultaneously, the screwing movement is used as a metaphor for the relation between the moving body and the space. Just as a screw needs friction to tighten, the dancers imagine that they need a counterforce to move. “While screwing through the space around us, we think about a screw going through something. There’s some sort of density around us” (Menzo Reference Menzo2023). The development of screwing as a choreographic tool should thus not simply be understood as a literal translation of the screwing technique used in the chopped and screwed music. Rather than slowing down preexisting material, screwing here defines a set of improvisational tools that focus on circular movement and stimulate the dancers to develop a state of “slow time gravity” (Menzo Reference Menzo2023).

Figure 6. From left: Camilo Mejía Cortés and Cherish Menzo silhouetted against a curtain of plastic strips in Darkmatter (2022), choreography by Cherish Menzo. Beursschouwburg, Brussels, 12 May 2022. (Photo by Bas De Brouwer)

Chopping is mainly associated with choreographic techniques of “scratching” and “stop time” (Menzo Reference Menzo2023). Menzo uses scratching as a choreographic tool to create small loops in which a specific movement is isolated and repeated. Referring to the physical act of scratching, the needle moving back and forward on vinyl, Menzo and Cortés make small repetitive patterns by moving back and forth between two positions. These micromovements are often done at normal speed, cutting through the slowness of the screwed movement and creating glitches that break open and distort the flow. Stop time is a technique that Menzo uses to suspend the movement. Notwithstanding its name, stop time does not stop the movement. Rather, it asks the dancers to enter into a “hyper-slowed space” (Menzo Reference Menzo2023). During our conversation, Menzo described how she develops this stop time with dancers during a workshop:

Just to give an example, sometimes I play this game where they have to go into stop time when I turn down the volume or stop the music, like in the children’s game “musical chairs.” I want the performers to feel like being in this space that is not tense but suspended and then also give them the space to understand questions like “Where can I go next?” I see this as the space of constant remixing. They are not just on one trajectory, but can suspend that trajectory and explore how they can move on from that. (Menzo Reference Menzo2023)

Stop time does not simply stop the movement but makes it more complex, multiplying the different possible outcomes. By interrupting the relation between action and reaction, it suspends the movement’s trajectory, allowing the performer to explore the different possible directions in which the movement could be advanced.

Although they are slow movements, it is important to distinguish chopped and screwed techniques from slow motion, a choreographic tool used extensively in contemporary dance, as well as in other movement traditions such as noh theatre and film. Slow motion preserves the integrity of the movement phrase, keeping the movement but slowing it down. Chopped and screwed, on the contrary, disturbs the flow of the movement. The insertion of screwed movements, as well as different types of scratching and stop time, undercut the experience of a temporal arc. This has a profound impact on our durational experience. Whereas slow motion does not really change our temporal experience—giving viewers more time to zoom in on its details—chopped and screwed destabilizes the temporal flow. As Han van Wieringen observes, in Darkmatter the “tension seeps away from the performance […], time slows down to the point where it suddenly seems meaning-less, without consequence” (2023:62).Footnote 10 But even as she disrupts the flow of the movement, Menzo does not eliminate the experience of time. Instead, she enables a different experience of time, an “Epiphenomenal” approach to time, which has profound implications for how blackness is experienced and constructed (Wright Reference Wright2015).

Epiphenomenal Time

In her landmark essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” Hortense Spillers argues that the black female body is always placed outside history. Buried beneath stereotypical names like “Peaches,” “Brown Sugar,” and “Sapphire,” it has become a static signifier lacking any “movement in the field of signification” (1987:65–67). Spillers argues that these stereotypes accrue “new layers of attenuated meanings” over time, further submerging the black female body beneath anachronistic markers (65). Unlike those who perceive racism as an antiprogressive force, a leftover from a bygone era destined to disappear, Spillers argues that the semiotic stasis of the black body is inherent in the Western progress narrative. Western modernity, she argues, necessitates the presence of the “primitive” black body as a counterpoint to its own perception of being “evolved” and “modern.” “My country needs me,” Spillers states ironically, “if I were not here, I would have to be invented” (65). In a similar fashion, Michelle M. Wright elucidates how the Western concept of progress contributes to the marginalization and erasure of black histories and experiences. While the progress narrative and its concomitant linear temporal framework are commonly perceived as intrinsic to reality, Wright contends that they constitute a historical construct originating in 18th- and 19th-century European philosophy. From its inception, this construct relegates black people to a mythical past, using them as a benchmark against which to gauge the West’s progress.

Wright proposes that the solution to this does not involve creating alternative histories or counternarratives that firmly integrate black identities within the progress narrative.Footnote 11 Although such endeavors may emancipate certain members within the black community, the embrace of a fixed narrative, with a distinct beginning, middle, and end, inevitably results in excluding those who diverge from the shared narrative. Wright particularly scrutinizes the “middle passage epistemology,” a progress narrative linking black identity to “the historical experience of slavery in the Americas and the struggle to achieve full human suffrage in the West” (2015:7). While this narrative holds the potential to liberate specific black communities by grounding their identities in history, it also tends to exclude people who do not share this origin story. Moreover, these progress narratives shift the focus away from the present and future of black identities, reducing them to products of history. As such, they “deeply inhibit agency by asserting that all members of the collective are the product of and reactors to history rather than agents with choice” (2015:26).

To mitigate these flaws Wright advocates for an approach that combines a historical reading of blackness with a phenomenological one. Whereas the former follows the logic of the linear progress narrative, trying to define blackness through the establishment of a shared origin story, the latter adopts what Wright defines as an “Epiphenomenal” approach to temporality (2015:6).Footnote 12 An epiphenomenon is defined as secondary, a byproduct that occurs alongside or parallel to a primary phenomenon but is not directly caused by it, thus complexifying the causal chain of action and reaction. Wright’s theory of temporality disentangles the causal relation between past, present, and future. “Epiphenomenal time,” she argues, defines a time in which the present moment is not directly determined by the moment that came before. This does not imply that the past does not influence the present, just that it does not do so directly or linearly. Wright argues, “the current moment, or ‘now,’ can certainly correlate with other moments, but one cannot argue that it is always already the effect of a specific, previous moment” (2015:6).

The concept of Epiphenomenal time enables Wright to perform a dual movement in theorizing black temporality. Firstly, Epiphenomenal time shifts the attention from the past to the present and from the question “What is blackness?” to “How is it performed in the present?” (2015:3). Rather than striving for a unifying narrative that delineates who can be identified as black, Epiphenomenal time “takes into account all the multifarious dimensions of blackness that exist at any one moment, or ‘now.’” Theorizing blackness “from the now,” Epiphenomenal time accounts for how different traces from both the near and distant past come together to shape the performances of blackness in the present as well as how these performances intersect with other collective identities, such as gender, sexuality, or socioeconomic class. Secondly, Epiphenomenal time frames the present as a moment not wholly determined by the past, thereby opening up possibilities for diverse futures. Drawing on the principles of “superposition” in particle physics— which posit that, at a subatomic level, quanta can exist in two states simultaneously—Wright advocates for conceptualizing the present as marked by fundamental ambiguity or multiplicity. No longer defined as an actualization of the past or an anticipation of the future, the present moment becomes a site of temporal experimentation, where the relations with the past are rethought and different futures are possible.

Tavia Nyong’o elucidates Wright’s notion in his Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life (2019). Nyong’o characterizes Epiphenomenal time as both “tensed” and “tenseless” (2019:10). It is “tensed” in that the Epiphenomenal “now” possesses the ability to compress different moments from the past into a “coeval presentness” (10). Simultaneously, it is “tenseless” because this compression extricates the now from the traditional tripartite structure of past, present, and future tenses. Nyong’o draws a parallel between this temporality and Henri Bergson’s concept of the virtual, a concept that the French philosopher uses to theorize the past. According to Bergson, we should distinguish our personal recollections from “pure memory” (1991:127). Whereas the former is tied to our individual experience, the latter denotes an atemporal reservoir in which all past events and actions are stored. This pure memory does not lie behind us but exists in the present. More precisely, it represents a realm of potentiality and becoming that is virtually coexisting with the actual present. As Gilles Deleuze argues, it is “real without being actual” (1988:96). We continuously use this virtual reservoir to inform our actual present, projecting images of the past onto this present in order to predict how it will play out. Even when it is not actualized, however, the pure memory is still virtually present, surrounding the actual present “with a fog of virtual images” (Deleuze [Reference Deleuze1977] 2002:148).

Seeing Jezebel and Darkmatter through the lens of Epiphenomenal time clarifies the temporality developed in both pieces. By lifting the now out of its temporal flow, Menzo’s chopped and screwed choreographies refuse to develop a historical narrative that enables spectators to define blackness or to critically deconstruct it. No longer held together by a clear temporal motif, the history of blackness stops moving in a certain direction and starts fluttering about. As a spectator, this temporal disarticulation might feel frustrating at first, giving the feeling of being stranded in time. But it also opens the possibility for temporal experimentation, pointing towards the “fog of images” from the past that the actual present holds in reserve. Jezebel and Darkmatter are full of such references to the past. In Jezebel, Menzo engages historical references to the Jezebel, as well as specific iconic moments from hip hop history. Towards the end of the performance, for example, Menzo puts on an inflatable jumpsuit that transforms the shape of her body. While this can be read as foreshadowing the future, a body that is part human, part machine, it is also a reference to the suit Missy Elliot wore in her music video The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly) (1997). Similarly, Darkmatter has many references to historical moments and characters, like the earlier mentioned Troubled Island by William Grant Still, an opera that portrays the life of Jean-Jacques Dessalines and was the first opera composed by an African American to be produced by a major North American company (Salazar Reference Salazar2020). These references, however, are never fully actualized. They linger, moving in and out of focus like ghosts haunting the present. This ghostly presence, as Mark Fisher argues, should not be understood as something supernatural, but as “the agency of the virtual”; as “that which acts without (physically) existing” (2014:18).

Lifting the present out of its linear arc, Menzo is able to make room for the multiplicity of virtual pasts and potential futures the present holds in reserve. Her stretching of the present not only prolongs time but also fractures it, opening it up to what is virtual in it, to what in it differs from the actual, to what in it can bring forth the new. After all, Menzo states in Darkmatter, “the future is only for ghosts and the past” (Menzo Reference Menzo2022).

Politics at a Lower Frequency

Gilroy locates the politics of transfiguration first and foremost in the act of performing. Lyrics embed a song within a discursive framework that is typical of Western rationality, while the way these lyrics are performed breaks open this rationality, pointing towards “the hidden internal fissures in the concept of modernity” (Gilroy Reference Gilroy1993:37). In the musical performance, the lyrics are “stretched by melisma” and “mutated by the screams” of the singers, opening them to different potential meanings (37). In Jezebel and Darkmatter, the focus is less on the breaking of language and more on the breaking of time. Through the introduction of chopped and screwed, Menzo suspends the simple flow of time, creating an experience of a “tenseless” temporality in which past, present, and future are no longer neatly aligned. Freed from its temporal shackles, the past no longer appears as a vast block that buries the present under its weight, but as a set of virtual possibilities that surround the present and allow us to reimagine the future. In Menzo’s chopped and screwed temporality, Missy Elliott’s “Fly Suit” has the ability to transform into an image of a futuristic cyborg-like video vixen and William Grant Still’s opera becomes a dreamy soundscape that haunts the present.

Although Menzo’s works are decidedly political, they seem to take a different route to politics than more conventional activist performance. Instead of developing a counter-discourse that inserts itself into the public sphere, Jezebel and Darkmatter transform or transfigure reality. By “stretching the notions of time,” Menzo aims to “generate new readings” for the black body (Menzo Reference Menzo2022). These new readings do not hinge on the creation of a specific historical narrative that sutures past, present, and future, but on the fabulation of a different idea of spacetime. As Nyong’o argues, fabulation is “never simply a matter of inventing tall tales from whole cloth” (2019:6). Instead, it entails a “tactical fictionalizing” that is geared toward the destabilization of the present so that it opens up to “something else, something other, something more” (6). These tactical fictions do not tackle political issues head-on. Instead, they traffic in “deliberately opaque means” (Gilroy Reference Gilroy1993:37). They exist “on a lower frequency” where they are “played, danced, and acted, as well as sung and sung about” (37).