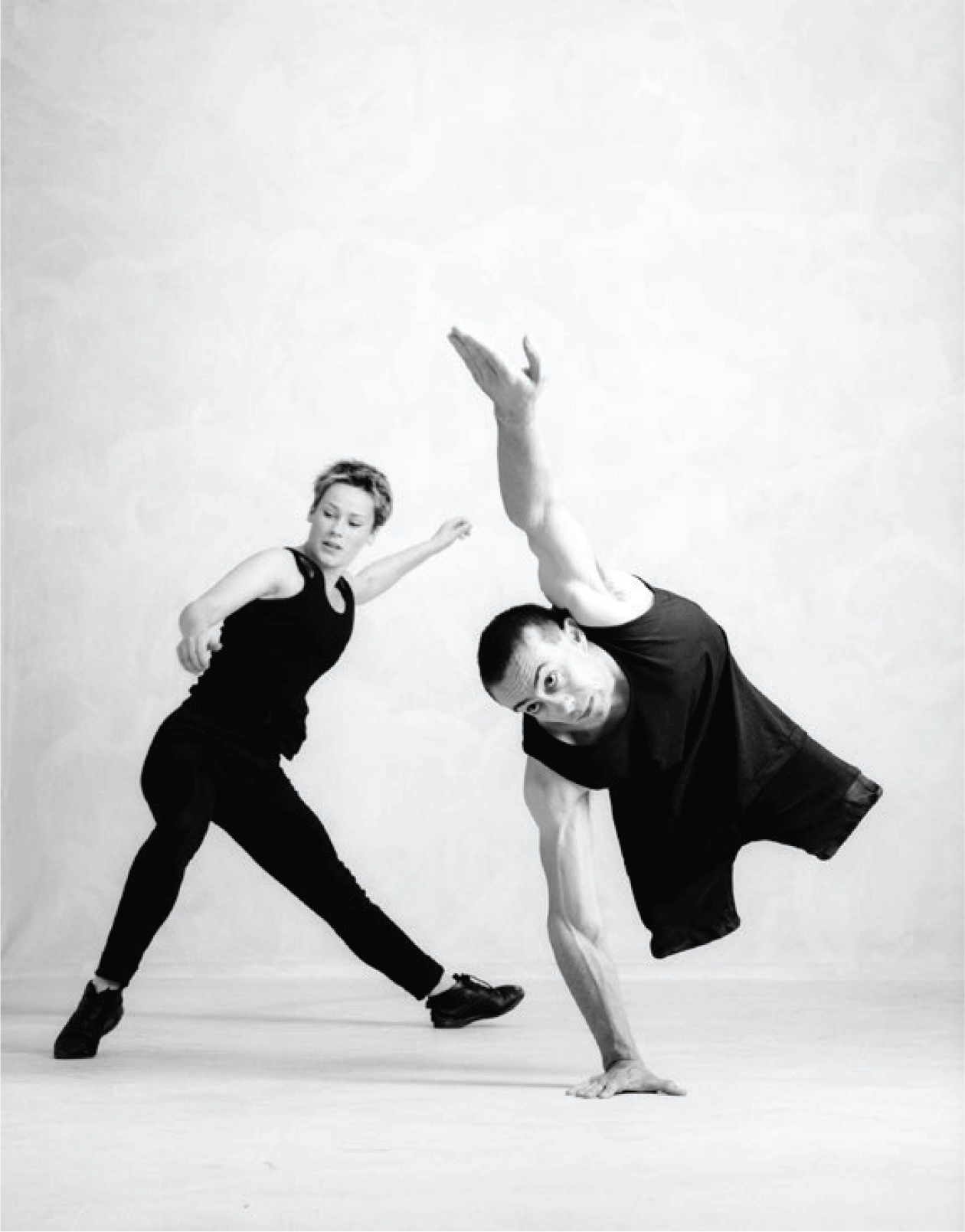

German-born scholar, poet, wheelchair dancer, and performance artist Petra Kuppers emphasizes the role of performance as a tool for social change, disability justice, and community building. Kuppers shows how disability shapes the creation and reception of new forms of artistic expression that embrace the unique experiences and perspectives of disabled people (Kuppers Reference Kuppers2003). Variously abled performers challenge, change, and work current stereotypes associated with disability, thus shedding light on contemporary identity politics and aesthetics. For example, legendary British legless dancer David Toole (1964–2020) performed in the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Paralympic Games.Footnote 1 He worked with the Royal Shakespeare Company, Candoco Dance Company, Graeae Theatre Company, and the Slung Low and Stopgap Dance Company. He played a lead role in the award-winning film The Cost of Living (2004) by DV8 Physical Theatre company. Toole was born with sacral agenesis. His lower spine and legs did not develop properly during gestation, and his legs were amputated when he was around 18 months old. Toole danced using only his hands, challenging accepted norms of strength, grace, and beauty. The circular fluidity of his movements, his leaps, rolls, and jumps, and the continuous rotations of his strong arms and torso made him appear to float in the air without effort. When Toole danced, space danced with him (fig. 2).

Our bodies are the instrument that allows us to move forward with our lives. Watching Toole perform—his dance dismantling the barriers of disability, the myth of bodily perfection—has always made me think about how our bodies are limited by social norms and structures and how necessary it is to change our perception of our bodies: a body does not have to be virtuosic to dance.

American award-winning dancer and performance artist Lisa Bufano (1972–2013) had her legs and fingers severed when she was 21 years old after a staph infection. This loss did not keep her from performing. She made different prosthetics for performances. She performed underwater with a single big fin. She danced as a glamorous, mythological being on four 20-inch wooden stilts made out of Victorian-style table legs (see fig. 1, fig. 3). She developed a cyborg lyra—an aerial steel hoop suspended from the ceiling designed to accommodate her limited grip and to allow her to float in the air. Bufano said these prosthetics gave her many different bodies as her center of gravity and the size of her body changed (in Davis Reference Davis2012).

Figure 1. Lisa Bufano on her signature Queen Anne table legs. All Worlds Fair, San Francisco, 2013. (Photo by Audrey Penven)

Figure 2. David Toole and Sue Smith. Back to Front with Side Shows, by Emilyn Claid for Candoco Dance Company, 1993. Photo shoot at Studio Hugo Glendinning, London. (Photo © Hugo Glendinning, All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2023)

Figure 3. Lisa Bufano In/Visible: Women fighting for visibility & survival in a world that doesn’t always celebrate difference, performed with Sonsheree Gilles. Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, 2012. (Photo by Audrey Penven)

My eye has always been drawn to abnormal forms […] It’s just that now my tool is my body. I’m still animating a form, but it’s my own form […] I’m not an astounding dancer […] But being a performer with a deformity, I find that there’s a gut response in audiences, an attraction/repulsion aspect to it that can be compelling. I just hope that there’s a balance between that gut response and the substance of a performance. (in SMFA 2013)

Bufano deployed her physical disability in performance to demonstrate that a disabled dancer can change our perception of what dance can be by producing tension in the spectators:

Despite my own terror and discomfort in being watched (or, maybe, because of it), I am finding that being in front of viewers as a performer with deformity can produce a magnetic tension that could be developed into strength. I attempt to channel this tension by exaggerating the mode of physical difference (for example, presenting myself on stilts). (Bufano Reference Bufano2006)

Referring to where cultural knowledge about disability leaves off and the lived experience of difference begins, Kuppers writes:

The aesthetics of disability dance can bring about an accessible dance culture. Accessibility does not only refer to impairment-specific alterations to the normal performance encounter but to providing conceptual space for a “stepping back” to see our cultural framings. (2000:129)

When performers do not conceal their physical limitations, spectators cannot escape their experience of voyeurism and personal preconceptions of the body. However, in the encounter with disability, they are also pushed to share the world with the vulnerable, hopefully moving toward a more socially inclusive future that emphasizes the creativity, resilience, and activism of disabled artists and socially disadvantaged people in general (Kuppers Reference Kuppers2022). Indeed, disabled performers are “signs of their times: a point when extraordinary bodies have a currency as lifestyle accessories when any shock or alienation value is eroded by the ubiquity of difference that is consumed and repackaged” (Kuppers Reference Kuppers2003:3).

When French choreographer Jérôme Bel staged Disabled Theater (2012) with the Swiss company Theater HORA—founded in Zurich in 1993 with Down Syndrome and Autistic Spectrum Disorder performers—Marcel Bugiel, the dramaturg for the production, said that the experience helped him understand that “the on-stage potential of actors with learning disabilities not only involved the social and political, but also the aesthetic, and that their work as actors touched on major issues around contemporary experimental theatre” (Bugiel Reference Bugiel2013). Bel realized that the performers’ extraordinary mental and physical presence threatened the “normal” idea of the healthy human as well as the idea of “normal” theatre, shaking up traditional codes both in art and in life. What happened with Bel was “the opening up of a space where disability is not expelled from visual and discursive practices, nor hidden behind the screen of political correctness, but is instead internal to a discourse that has a bearing on both the aesthetic and political dimensions” (Vecchiarelli Reference Vecchiarelli2013). With Disabled Theater, Bel rejected the marginalization of disabled performers.

Their freedoms reveal theatrical possibilities that I didn’t know existed. The first question to ask is what theatre these actors perform. The second is why they perform this theatre. And the first thing to ask yourself is: Who are they? That’s when another research field appears, that of the individuation of performers. It’s impossible for me not to use that. The performer is the heart of my theatre: he or she must appear on stage as an artist, worker, citizen, subject, and individual in his or her most absolute uniqueness. It’s this uniqueness that can reveal to me just what theatre is capable of. Disabled (or incapable!) actors open up new possibilities, new powers! (in Bugiel and Bel Reference Bugiel and Bel2013)

Forty-five years before Disabled Theater, in 1967, the National Theatre of the Deaf was founded in the US, the first disability theatre “creating performance works that bridge the deaf and hearing worlds through their combination of American Sign Language (ASL) and speech” (Kochhar-Lindgren Reference Kochhar-Lindgren2002:3).

Beginning in the late 1970s, disability theatres were formed outside the US: Compagnie de l’Oiseau-Mouche (1978, France), Graeae Theatre Company (1980, UK), Theatre Terrific (1985, Canada), Back to Back Theatre (1988, Australia), RambaZamba (1990, Germany), among others. However, disability theatre is still a niche. In Brazil, for example, disability performance remains controversial.

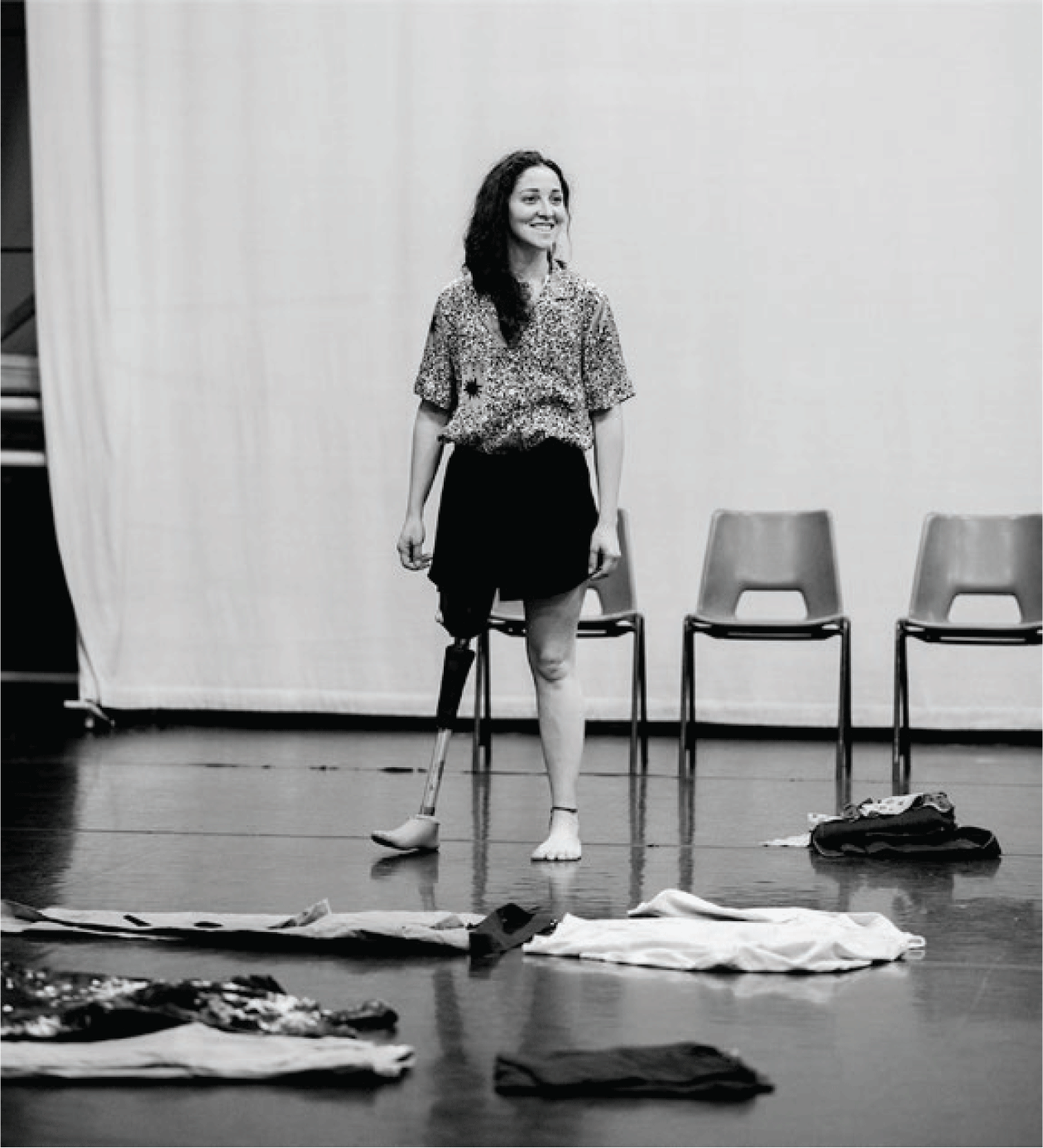

Poverty frames most of Brazilian society. The marginalized are misused and forgotten. Mainstream media, pop culture, and advertising propagate unrealistic images of body perfection and hyperefficient body performances that condition people to believe that the image and shape of their body are critical components of their worth. A systemic lack of adequate infrastructure means disabled people do not have access to public spaces and cannot move autonomously from one place to another. Still, disabled artists persevere. Take the case of Brazilian dancer Mickaella Dantas (fig. 4), who sadly passed away on 10 February 2024, after a long battle with cancer, which inhabited her body at different times during her life: “Dantas was first diagnosed with cancer at the age of 11. As a result of the disease, after two years of chemotherapy, she had to have one of her legs amputated. This experience led her to get closer to dance, especially in companies that brought together people with disabilities and other physicalities” (FRRRK Guys 2024).

Figure 4. Mickaella Dantas in Hetain Patel’s Let’s Talk About Dis by Candoco Dance Company. Aspire National Training Centre, Stanmore, England, 2018. (Photo by Camilla Greenwell)

In 2011, she left for Portugal and then the UK, where she found extensive support for prosthetics and general health (Dann Reference Dann2020). She danced for choreographers Henrique Amoedo (Companhia Dançando com a Diferença [Dancing with a Difference Dance Company]), Paulo Ribeiro, and Clara Andermatt. From 2017 through to 2021, she joined the prestigious Candoco Dance Company, whose mission is to extend the limits of dance by employing disabled and nondisabled artists who find innovative ways to collaborate. As a full-time company dancer with Candoco, “Dantas performed nationally and internationally in more than 10 different pieces of work” (Candoco Dance Company 2024).

In July 2023, already undergoing cancer treatment, reflecting on her body and the experience she was going through, Dantas wrote on social media:

Listen to your body so you don’t break it. I feel my structure is fragile, my skeletal system is tired, and for the first time, I don’t blame it. My body has sustained me with immense perseverance: chemotherapy, radiotherapy, strong doses of medication, the effects of the medications, and pain. My body, my structure, my source of energy, vitality, creativity, strength and dance, it also has the right to get tired, and all I can do for it now is to do very little… accept physical help, thank it for having sustained me so firmly until now and respect it. Strength is rebuilt every day. (FRRRK Guys 2024)

In the fields of theatre, dance, and performance art, performers with disabilities are often outspoken in exposing the systemic flaws of the societies in which they live, highlighting obstacles that hinder them in their daily lives: “attitudinal, communication, physical, policy, programmatic, social, and transportation” (CDC 2024). There are many barriers, hindrances, and

external factors in a person’s environment that, through their absence or presence, limit functioning and create disability. These include aspects such as a physical environment that is not accessible, lack of relevant assistive technology [assistive, adaptive, and rehabilitative devices], negative attitudes of people towards disability, services, systems and policies that are lacking or that hinder the involvement of all people with a health condition in all areas of life.

(Ustün et al. 2010:79)

In their performances, Brazilian Felipe Monteiro, Italian Nicola Fornoni, and French-Algerian Kamil Guenatri confront their disabilities to highlight the systemic shortcomings that negatively impact people with “differentiated bodies.” They emphasize what alienates them; they deploy and risk their fragile bodies as poetic-political devices blurring the line between art and the rest of reality. Their performances are in-depth reflections on human finitude.

From Felipe Monteiro

In 2013, Nara Salles and I coined the term “differentiated bodies” not only to designate people with disabilities but also to transcend the stigma, affirming everyone’s right to have, inhabit, and perform a differentiated body. “Differentiated body” does not refer specifically to the medical and social models of disability. The medical model aims to discover the causes of a person’s disability and tries to normalize the person to make them socially acceptable, linking disability to misfortune, assigning “outsider” status to the unfortunate, a stigma that brings with it exclusion (see Goffman Reference Goffman1963).

I thought of the expression “differentiated body” when I was rejected from a dance class at the university in Maceió, the city where I was born and live. Alagoas, in northeastern Brazil, is a region still dominated by a culture of intolerance and indifference. Since then, I have used this term to counter the impossible “perfect body” standards ingrained in the society and culture I grew up in.

I am affected by severe progressive spinal muscular amyotrophy (SMA), a genetic neurodegenerative disease that affects the anterior horn of the spinal cord. A progressive degeneration of motor neurons occurs but does not affect the sensory, at least in my case. Due to the SMA and severe scoliosis, I have no autonomous locomotion. Because my muscles are atrophied, my hands and feet have a certain degree of deformity, and I have no strength to perform movements (tetraparesis). I use a noninvasive ventilation device intermittently, which helps to keep my lungs open and prevents the muscles responsible for breathing from being overloaded. I struggled for years to obtain sufficient funds to be followed by a multidisciplinary medical team—a doctor, a physiotherapist, a nurse, and a medical technician—to minimize the complications in my musculoskeletal and respiratory systems and allow me a certain margin of independence at home and in my professional environment. As we say in Brazil, they “treat me to really live not to live just to treat myself.”

Through scholarships and grants, I contended successfully for homecare when attending the university, as well as for my sister, who has a clinical condition similar to mine, although slightly less severe. However, I have suffered discrimination since I was a child. When I attended primary school, I was bullied by the nuns. I endured humiliation in silence. Because of the overall lack of accessibility within the buildings where I studied, including the university, I was excluded from almost every activity.

All my performances are autobiographical. I organize performative situations to make life and art converge by sharing my personal experiences with an audience, exposing the difficulties I encounter in my quotidian activities. I take over the performance space and expose my vulnerable body as a tool to stimulate a discussion about the marginalization of disabled people as a minority, a discussion I deem necessary for societal development. Through performance art, I can express my concerns about the hypocritical society where I live, which regards “the disabled” as a separate category of humans, an unwelcome problem to be relegated to the periphery. I assert that the display of explicit differentiated bodies in performance art (the body as it is) is a radical invasion of the domain of established social norms that are predicated on judging bodies like mine as unacceptable according to cultural body standards. My performances are insurgent acts, insubordinate presences in the folds of a reactionary system that ghettoizes disabled people. By bringing the derogatory situations I live in inside the performance space, I expose my vulnerability and apparent weakness as a form of artivism. I denounce what I see and experience as unjust. I discuss diversity as an opportunity for societal change. In so doing, I explore how my differentiated body is perceived and understood by others, questioning Otherness as “the result of a discursive process by which a dominant in-group constructs one or many dominated out-groups by stigmatizing a difference—real or imagined—presented as a negation of identity and thus a motive for potential discrimination” (Staszak Reference Staszak2009:2). I also view the aesthetics of invasion as a form of resistance against discrimination and as a way to praise the courage of performers with differentiated bodies who expose themselves publicly in order to express their concerns and defend their ideas, and eventually to be acknowledged not only for their disabilities but also for their art (Monteiro and Salles Reference Monteiro and Salles2018).

While studying Antonin Artaud and Jerzy Grotowski at the university, I realized that if I was going to perform, my actions had to address how the stigmatization process affects my differentiated body and my interpersonal relationships. Because I cannot move autonomously, I had to identify aesthetic parameters related to my clinical condition and within which I could performatively implement my ideas, exposing my body to the gaze of others. I wanted to raise awareness about the physical suffering caused by severe diseases and disabilities for which there is often no remedy, attempting a performative conversation between bodies in pain (as individuals and as artists) and audiences, the community, and society, without falling into clichés and victimhood.

For my first performance, I envisioned an imaginary dialog between my differentiated body and Mexican artist Frida Kahlo’s—I empathized with her polio, several surgeries, loneliness, and life story. I was also inspired by Oswald de Andrade’s 1928 Manifesto Antropófago, which proposes that Brazil’s cannibalizing of other cultures is its greatest strength and a way for the country to assert itself against European neocolonialism (Andrade [Reference Andrade1928] 1991:38–47). “The anthropophagic thinking combines a focus on the body, the passions and ideas of physical desire and aggression with cultural notions of hybridity and mixture, making the notion ripe for debates in contemporary organization theory” (Islam Reference Islam2015:351). I anthropophagically swallowed episodes of Kahlo’s biography looking for an antidote to the psychological ghosts that hinder me from exposing my body in front of an audience—my psychophysical limitations, the sudden and frequent attacks of tachycardia (a heart rate over 100 beats a minute), and my extreme anxiety.

I performed Kahlo em mim Eu e(m) Kahlo for the first time on 16 January 2013. The title translates as “Kahlo in me and me in Kahlo” and explains that I understand Frida Kahlo’s body as differentiated and that I undertake an anthropophagic dialog between me and her. I did not represent Kahlo mimetically. I weaved visual and narrative elements of our personal experiences to find a luminous trail to make clear my urgency to be considered equal to any other person. At the beginning of the performance, those who assisted me handed out 30 lanterns to spectators—their colors recalling Kahlo’s paintings. A projection of photographs of her life and works was screened on a canvas hanging above the mat, where I would later be placed, aided by some spectators. The canvas alluded to the mirror on the Mexican artist’s bed that she often used to paint her self-portraits.

I was costumed in different kinds of fabrics cut into asymmetrical shapes: yellow, black, white, and red cotton knitwear; green and blue ribbons and embroideries; gold glitter; yellow leather shoes with red laces—a tribute to the colorful long skirts Kahlo wore to highlight her cultural origins and hide her leg atrophied by polio. Through the projections and the light produced by the lanterns the spectators held, I intended to open up a shared dreamlike space. A lavender scent, generally used to calm newborn children, permeated the space—a bittersweet reference to the impossibility of Kahlo giving birth.

In the first part of the performance, I recounted episodes of my life: my birth, the DNA test and subsequent discovery of my illness, moments of my childhood and adolescence, the many hospitalizations, episodes of discrimination, a few friends at school, my passion for performance, art, and theatre. Soon after, I asked some spectators to help me out of the wheelchair and position me on the mat. They hesitated: How do we lift you up? Does it hurt? This established a dialog; the spectators took part in the performance. Most of them probably had no daily relationships with people with differentiated bodies, hence the initial hesitation of those who decided to help me and the astonishment of the others who just watched. Yes, I do feel pain. Yes, I am scared of inadvertently breaking any part of my body. I have already broken my arms and legs twice. But I must continue the performance.

The spectators put me on the mat. I depended entirely on them. I invited them to remove my costume until I was completely naked. I asked them to write with markers a word or a sentence on my body: What have you thought or felt when I was lifted and placed on the mat? What do you see when you see me naked, so close to you? Look, I can hardly move my hands… Words began to cover my skin: Fear, Bold!, Mind, Fragility, Courage, Apparent Fragility, To Help, Caution, Life, Brave, Different, We Are One Body!, Trusting, Careful, Wings Not feet, Different Body, Illusion, Faith, Strong, Beautiful, Beautiful Life, Victory, Freedom, Love, Made to Love, Kindness, Human Being, Perseverance, Happiness, Anguish, Strength, Fight, Baby, Difference, Affection, Willpower, Softness, Ashamed of Me, Spirals, Contortions, Respect, To Dream, People (fig. 5).

Figure 5. Felipe Monteiro, Kahlo em mim Eu e(m) Kahlo. Espaço Cultural Linda Mascarenhas, Maceío, Brazil, 2013. (Photo courtesy of Felipe Monteiro)

Exposing my physical fragility and vulnerability and letting the audience interact directly with it by touch, did I subvert the sociocultural conventions that so much constrain our freedom to act? Did some spectators identify themselves with my differentiated body? Did they project something of themselves? Revealing my stigmas to the spectators’ gaze, did I transgress prejudices on disabilities and free myself from stereotypes commonly associated with it?

I involved the spectators as coauthors of a performance ritual, nurturing the need for proximity and interconnectedness. I gave them the chance to actively reflect on the marginalization and stigmatization that disabled people suffer. We are all incomplete but animated by the need to complete ourselves as human beings by entwining our hearts, as Frida Kahlo dreamed. My actions often depend exclusively on the spectators’ willingness to assist me. They exercise their responsibility in dealing with my defenseless body without injuring my body-in-pain.

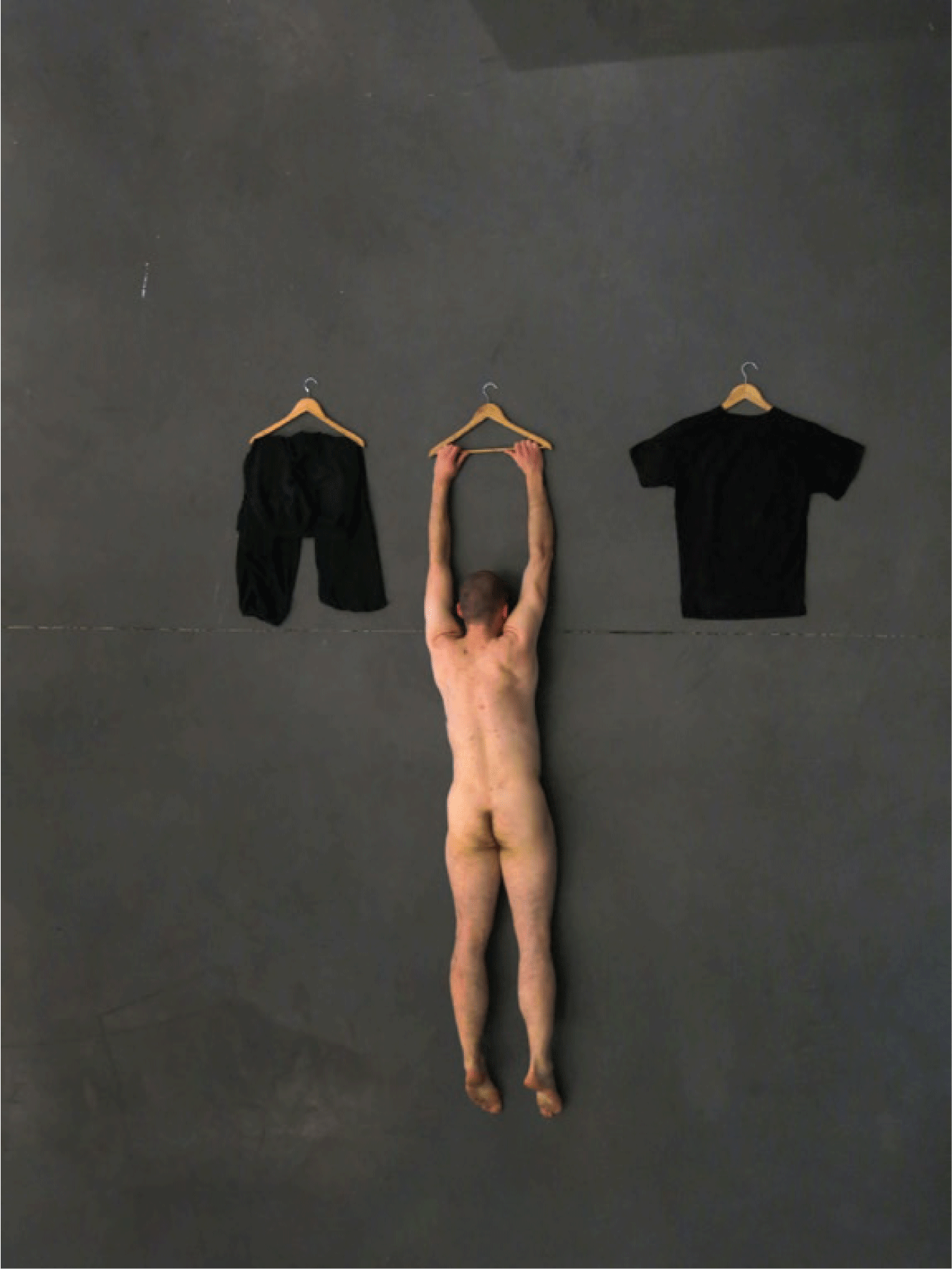

I implemented my ideas of interactive, participatory performance with (Des)Vitruviando, one of the three performances I conceived in 2014, the practical part of my PhD at the Federal University of Bahia (Salvador). In (Des)Vitruviando, I compared my differentiated body in opposition to Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man—my asymmetric corporeality challenging his model of harmonious proportion perfectly, and impossibly, fitting the square and the circle.

The performance occurred at the Cañizares Gallery, in a university building. A technician helped me make a square on the gallery floor with large sheets of white paper. Then he scattered several colored pencils the audience would use to outline my differentiated body on the paper floor. Or to scribble or write anything and, in so doing, engage with me.

Wearing only underpants, I then asked some spectators to take me in their arms and gently put me belly-up in the center of the paper square. Then I invited them to come closer and interact with my body. Only a few approached me. Ciane Fernandes, who leads the performance laboratories I attended, was the first to join. Then came Susanne Ohmann, a dancer and dance therapist who studied at the Folkwang Hochschule in Essen under the direction of Pina Bausch (fig. 6). As if alluding to aspects intrinsically linked to an inherent intimacy, we absorbed body shapes and signals from each other and started exploring the proportions and disproportions of our bodies in space. We experienced an affective reciprocity—a multiple, inclusive, emphatic improvisation of imperceptible movements and minimal touches, so that I could participate unassisted. The other spectators watched transfixed, making almost a ritual community, giving us their support silently. Somehow, I felt they shared my silent scream.

Any change in position or movement of his body would have to be initiated externally. And that is what he—a so-called disabled man—could do. He invited audience members to draw around and beyond his contours, extending his limbs by lines and wording. Sliding horizontally towards Felipe, I zoomed in on his exposed armpit. I felt free to explore the proximity. His skin was radiating a sensuousness that was difficult to ignore. I put my finger in a jar of body paint that I brought from a performance the night before as the pencils looked unappealing for me to draw with. With my blackened index finger, I accentuated the hair in his armpit. I put color on my lips and gently kissed his ribcage, leaving a mark similar to an explorer placing a flag on a mountain peak claiming: “I was here!” I continued kissing the paper while slowly retreating to the edge as if leaving footprints on my way out. Then I engaged in a movement trio with Fernandes and Felipe. A most memorable moment was when we created an energetic circle through mutual touch, ending in a highly dynamic pause. It was as if we simultaneously experienced a closed electric circuit that could turn a light bulb on. A transgression of boundaries occurred. Drawings and text became Monteiro’s bodily extensions, materializing without his “doing” since all he did was “be” there, motionless, in the center, like the eye of a hurricane. On the one hand, he looked like an elegant sculpture. On the other hand, he looked estranged, almost like an aborted embryo. But he was not forcing a “look at me!” or “look how special I am!” onto the audience, but seducing curiosity in a relatively gentle and subtle way. He claimed his space without defending any territory. His vulnerability proved to be his strength. (Ohmann Reference Ohmann2014:176–77)Footnote 2

Figure 6. Ciane Fernandes and Susanne Ohmann with Felipe Monteiro, (Des)Vitruviando. Galeria Cañizares, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, 2014. (Photo by Luis Carneiro Leão; courtesy of Felipe Monteiro)

About (Des)Vitruviando, Ciane Fernandes wrote:

I created a volumetric autobiographical painting, an unfinished work by measures perhaps distant from the harmonic ideal of Vitruvius, but very close to each of the visitors to the site who, that night, felt called to bypass. My fragility was so visible that it became my irreverence. (2017:141–42)

I performed the other two performances outdoors as part of my PhD research in scenic arts at the Federal University of Bahia (Salvador, Brazil). Sanguis (Blood) was an outdoor hospital ritual metaphorically recalling the hospital’s visiting hour. It was a reframing of my several hospitalizations, my fear when I see the blood on the syringe’s needle when doctors and nurses give me an injection, and my rejection of medical gowns. I asked permission to color the fountain’s water in the university park with red food dye. I was forbidden to do so. So I chose a spot in the park to station my wheelchair. I installed a small table with surgical gloves, white gauze, needles, and a small sound system reproducing the sound of my heartbeats recorded during an echocardiogram. I asked the people who approached me to wear surgical gloves, take a needle, pierce one of my fingers, scribble with my blood on the white gauze what they wished, and light two incense sticks (fig. 7). Those who gathered around me were worried about the protocols. Those who had the courage to pierce my finger were hesitant, afraid of causing me unnecessary pain. Where should we prick? Where does it hurt the least? I perceived the disquiet and restlessness but also the empathy of the spectators. I tried to put them at ease as much as possible. The blood on the white gauze—a symbol, symptom, and backdrop of my reality—remained as the tangible evidence of the interaction between myself and the spectators.

Figure 7. Felipe Monteiro, Sanguis, 2014. Video still. UFBA Theatre School (the park), Salvador de Bahia. (Courtesy of Felipe Monteiro)

I performed Sanguis not just to exorcise my fear of blood but also to raise a concern about the need to care for each other. I faced my disease self-sacrificially, offering my body and engaging the audience in a participatory act on my body—an act of mutual trust. After watching the video of the performance, French philosopher Sylvère Lotringer wrote me that I staged my reality in a public place in such a conflicted way that those who were there hadn’t the courage to walk away because I was genuinely performing my private theatre of cruelty publicly, leaving my transitory audience incapable of deciding if they witnessed something too lewd to be seen, or the ultimate act of bravery, which is my physical deterioration (Monteiro and Salles Reference Monteiro and Salles2018:265–66).

After Sanguis, I performed Reliquiarium Experientiis (Reliquary of Experience) in Salvador de Bahia at Largo de São Francisco, in the Pelourinho district. The performance was held in the central square before the San Francisco church where enslaved people were flogged and sold when Brazil was a Portuguese colony (1500–1822). Pelourinho is today the cultural heart of the city. The name means “pillory/whipping post” in remembrance of the cruelty of slavery.

I designed the performance sourcing from episodes of my life related to religion—my education by nuns, my past desire to become a priest, and my interest in Catholic art and the biographies of saints. I sat barefoot and motionless in my wheelchair for an hour, dressed in a costume similar to religious vestments. I placed a book in front of me and a small, red banner with the phrase “Write inside the book what you feel and/or think when you see me” (in Portuguese, English, French, and Spanish).

Only a few passersby wrote something in the book and signed it:

Eu vejo uma pessoa frágil, mas com coragem de mostrar suas fragilidades. Me faz questionar o que é considerado como frágil; corpo ou espírito? [I see a fragile person but with the courage to show their fragility. It makes me question what is considered fragile: body or spirit?] (Camila Freiras)

A 1ª imagem: um santo/A 2ª imagem: o pagador de promessas. [The first image: a saint. The second image: the fulfiller of promises.] (Olívia Camboim)

Então, o que é o corpo isolado? Qual sua noção há em ver o outro? E a imobilidade. [So, what is the isolated body? What is your notion of seeing the other? And the immobility?] Uma vida ser. Uma vida outra. É a minha, que não é a sua vida! Vida, Vide! IDA, DAVI. Filho ser. VIDA. [“A life to be. Another life. It’s mine, it’s not your life! Life, See! IFE, EFIL. Son to be. LIFE.”] (Carlos Alberto Ferreira)Footnote 3

EU QUERIA VER MINHA FILHA SE ESTÁ Bem. [I WANT TO SEE IF MY DAUGHTER IS okay.] (Telma do Santos)

Minha primeira impressão é admirar a coragem para realizar esse trabalho. Nem todos os artistas são capazes de tamanha entrega. O impacto está, para mim, em ver a expressão artística em tudo que o cerca e principalmente na corporificação dessa arte. Sinto-me admirado e orgulhoso! [My first impression is to admire the courage in carrying out this work. Not all artists are capable of such delivery. The impact is, for me, in seeing the artistic expression in everything that surrounds him and mainly in the embodiment of this art. I admire you and I am proud of you!] (Gildon Oliveira)

I exposed my disability in a public street to reveal my true self, to seek a link between art and life, to stimulate the gaze of the passersby, to show the value differences, and to transgress the stigmas and stereotypes associated with differentiated bodies. I was afraid because I spent one hour immobile, silent, and unguarded. Some people thought that I was a living sculpture and photographed me. Some others gave me coins, presuming I was begging. It made me feel how much the beggar is stereotyped. I sensed from people fleeting feelings of righteousness and compassion; and also a hypocritical guilt, maybe.

My last performance was in 2018. I was invited to perform a new work at FilteBahia Theatre Festival focusing on Artaud’s influence on Latin American contemporary performing arts, to celebrate the 70th anniversary of his death. I made O problema é porque sou lúcido?!, my most invasive work. The title is a question and an exclamation simultaneously, which in Portuguese means both “Is the problem because I am lucid?” and “The problem is that I am lucid!” I chose this title because sometimes I disagree with the care the professionals attending me at home give. They often want me to be docile and submissive. A while ago one of them said I am a problem because I am lucid and outspoken. Even though my differentiated body is deprived of locomotion, I still have my view of reality and a voice to express my thoughts and concerns, which, however, often is unheard.

In O problema é porque sou lúcido?! I laid motionless on a hospital stretcher, wearing only underpants and a tailored vest that Vivienne Westwood gifted me. I had unpretentiously written to her that I would have loved to perform wearing a costume designed by her. She sent me a T-shirt, a tailored vest, and an autographed book as a gift.

In the performance, I breathed through my bilevel positive airway pressure machine (BiPAP). This noninvasive ventilation device allows me to breathe and helps me open my lungs with air pressure when I cannot get enough oxygen and get rid of carbon dioxide. Unlike invasive mechanical ventilation, which connects to a tube in your throat, BiPAP delivers air through a mask on your face or nasal plugs connected to the ventilator.

Once again I used the sound of my heartbeat recorded from an echocardiogram (as in Sanguis) and a projection of photographs of meaningful moments in my life. I asked that the theatre’s foyer doors be left open, so the audience could enter and stay as long as they wished or leave whenever they wanted to. Some sat on benches and watched the projection, while others approached the stretcher to interact with me somehow. Some put their head on my chest to listen to my heartbeat and touched my hands gently. Brazilian performer Ciane Fernandes improvised a dance. French singer, actress, and storyteller Kaloune sang a capella while the spectators accompanied her, rhythmically clapping their hands (fig. 8). These unplanned, consensual, unmediated, interpersonal encounters with my motionless body created a togetherness. Once again, I performed against indifference. I deployed my differentiated body to shape the conversation about being seen as equal by others and, at the same time, to celebrate life.

Figure 8. Kaloune and Felipe Monteiro in O problema é porque sou lúcido?! Teatro Martins Gonçalves da UFBA, 5 September 2018. (Photo courtesy of Felipe Monteiro)

Nicola Fornoni

Nicola Fornoni was born in Brescia, Italy, in 1990. His life has been marked by the diseases he suffered since childhood, progressively compromising his bodily functions and motor skills. He started performing in 2013, evoking and elaborating upon memories of his hospitalizations through symbolic objects such as gauze and lancets for measuring the sugar level in his blood.

For Fornoni, to perform is almost an abreaction to relive and overcome painful experiences that trouble him. For years he tried to avoid the word “disability” for fear it would become a label from which he would not be able to free himself—a term that, in his own words, rather than defining his situation precisely, dismisses it, limiting understanding of the particularities that make each person unique, whatever their clinical condition. However, in 2016, he felt the urge to contribute to the debate around the lack of accessibility for disabled people in historic Italian cities, which is the norm. He wanted to denounce the public administration in my city for doing nothing to solve this problem.

He asked his mother and a friend who is a videomaker to bring him to the underpass of the Brescia train station. He remained motionless in his wheelchair for seven hours. He hid his face behind a round mirror, like a mask (fig. 9). He did so because if any of the passersby approached him to ask what he was doing there, they would see their faces reflected, as if they were asking that question of themselves. His mother and friend stood quite far from him, so it looked like he was all alone. Recounting the experience, Fornoni says that some people wondered if he was real or fake, and others greeted him. Only a few of them dared to ask him to explain what he was doing there, curious to look beyond the mirror and see his face. No one offered to help him climb the stairs and get out of the underpass (Fornoni Reference Fornoni2023). Later, he titled the performance Nemo Propheta in Patria (No One Is a Prophet in Their Land).

Figure 9. Nicola Fornoni, Nemo Propheta in Patria, 2016. Video still. (Courtesy of Nicola Fornoni)

For Fornoni, staying in the underpass, a transitory place-non-place, not seeing but hearing train noise and people’s shouts and voices nonstop, was tiring and alienating. Disengaging his gaze from the gaze of the others and sitting still for seven hours tested his endurance. After a few hours, his mind got clouded. “I felt confused, I lost of my capacity to perceive my surroundings. I experienced the separation people project when they come across a person in a wheelchair but do not see their face” (Fornoni Reference Fornoni2023).

Fornoni is affected by a severe form of scleroderma, which is a chronic, autoimmune, rheumatic disease that affects the body by stiffening the connective tissue. He has always resisted coming to terms with his disease, but he did so in the performance Fuckdermia in 2018. He stayed alone in a room, moving by means of an orthopedic walker for an hour and a half, with just a few breaks (fig. 10). While showing his physical fragility, he emphasized his struggle and resistance against the illness that afflicts him. He reacted and defeated it. He performed Fuckdermia shortly after discovering he could slowly walk again, aided by the walker. “Stand up, hold up, stay upright, walk” (Fornoni Reference Fornoni2023).

Figure 10. Nicola Fornoni. Fuckdermia. Vaku Project Space, Bergamo, Italy, 2018. (Photo by Sofia Obracaj; courtesy of Nicola Fornoni)

Fornoni walked as a philosophical exercise, like Thoreau who began his lecture “Walking” this way: “I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil,—to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society” ([1851] 1862).Footnote 4 He walked to praise his body because it allowed him to discover a new way of being and perceiving himself. He defied his profound fatigue to control his breathing, to balance his effort with repetition. The performance took place in a relatively small square room of the Vaku Project Space (Bergamo) in front of a limited number of spectators who could freely enter and exit the room or lean against the walls. Fornoni circled left and right, clockwise and counterclockwise—sometimes one round at a time and sometimes two. Periodically, he took a few steps and then sat for a moment on a chair placed in the corner of the room. Then he resumed the walking, a roundabout route like van Gogh’s 1890 painting, Prisoners’ Round, a walk of temporary relief.

Fuckdermia is my middle finger to scleroderma, the disease that afflicts me. Breathe in, breathe out, resist. I prepared for several months, purifying the energy of my chakras by practicing twin hearts meditation and prana healing from Master Choa Kok Sui’s teachings. The audience reacted in silence and never intervened. Those spectators who lingered for almost the entire time of the performance empathically experienced my effort to walk independently, without assistance other than that of the orthopaedic device. Was my performance a sacrificial act in the hope of getting better, or a duel between myself and my increasing physical distress? (2023)

In 2022 Fornoni analyzed his clinical condition using spoken words in two installations of UnderScars, a collective performance opera envisioned and devised by VestAndPage (Verena Stenke and Andrea Pagnes) in collaboration with Andrigo & Aliprandi (figs. 11 & 12). UnderScars grew out of Pagnes’s research project, “Islands Included: Inclusive Production Methodologies in the Performing Arts for Diversely-Abled Performing Arts Practitioners” (2022), supported by Fonds Daku (Germany).Footnote 5 For the performance, Fornoni transformed his afflicted body into an organic poetic membrane. Navigating with his wheelchair between dancers and acrobatic body moversFootnote 6 in a play of tender physical contacts and contrasting moving images, he invited spectators to reflect on the broader dimensions of existence through his two monologs.

Figure 11. Nicola Fornoni and Marianna Andrigo in UnderScars, a collective performance opera by VestAndPage (Verena Stenke and Andrea Pagnes) in collaboration with Andrigo & Aliprandi. Forte Marghera, Venice, Italy, 2022. (Photo by Lorenza Cini; courtesy of VestAndPage)

Figure 12. Nicola Fornoni and Marianna Andrigo in UnderScars, a collective performance opera by VestAndPage (Verena Stenke and Andrea Pagnes) in collaboration with Andrigo & Aliprandi. Forte Marghera, Venice, Italy, 2022. (Photo by Lorenza Cini; courtesy of VestAndPage)

First monolog:

Many life events make us realize that we need a breakthrough. A humiliating society alienates those with different anatomical potentials—daily hardships. The notion of rebirth is applied in an apparent stasis situation. The body moves. It is all effort and fatigue. Its mutation throughout life is already an extraordinary and incredible performance. Have I ever performed without having health problems? The acute lymphoblastic leukemia when I was five years old and the relapse when I was eight. The first transplantation I had of the bone marrow, then scleroderma, and the second one of stem cells. Scleroderma is an autoimmune disease that, from the standing position, constrained me to the sitting one. Body art, love, body limit, transformation, relations, life, and its transcendence. I do not hide or run away. I perform and put myself on the line. It is my being in revolt.

Second monolog:

The origin of everything is in the body, in the clash-encounter of atoms and cells. There is something peculiar in relating to ways of life that are not one’s own. To conform, to get used to, to improve. Not only in a wheelchair but in the face of barriers to overcome. The obsession with feeling useful. For example, what makes me crawl down the stairs, limb after limb, at the risk of breaking my neck? Isn’t it unnatural? Any object can be shattered down, and each piece of architecture can be shaped to the body. A roof can be a floor, and a railing or rigid rope can be a line. Without one hand, one leg, one arm. With a stick. On a trolley. Being guided without wanting to. Will I be able to make it by myself and become independent? This question arises continuously with the disability. Novelty increases the risk, and the tension builds. Places change. Prostheses are indispensable to acknowledge what is around you. Finding always different methods of movement. Never make rash moves that could harm or be fatal. Anything can be a minefield. You have to look down at your feet. Stand on a tool that glides, slides, rotates, curves, and rears. The movement is oscillatory and rotatory. One hand remains stationary. The other pushes and holds. Coordinate the body: the back, the shoulders, and the head. Try to take things that are up there. No elasticity, no chance to stretch or squeeze. It all depends on the type of disability. Someone can fold their legs. Others do not fully extend or flex them. They wouldn’t even go through a narrow passageway. You can’t hide much under a bedsheet. Extend. Hold the position, melting, tendon by tendon, muscle by muscle. This is the Carthusian way of my body. A wader with the only certainty of the ass as support and feet that slide. Some obstacles contradict the “ease” theory, such as having to sleep on bunk beds that are too high. One push, one step after another. You can’t jump. Not even fall. It would mean facing a new trauma. (in VestAndPage et al. 2022)

Kamil Guenatri

Kamil Guenatri was born in Algiers in 1984. He moved to Toulouse at 17 to study mathematics and computer science. At the same time, he became interested in literature, particularly Arthur Rimbaud and Antonin Artaud; and artistic studies, especially performance and interventions in public spaces. Guenatri is affected by spinal muscular atrophy with low mobility of the limbs and suffers severe respiratory failure (similar to Felipe Monteiro). He uses a motorized wheelchair and needs 24-hour care. However, his clinical condition does not prevent him from performing at international art events.

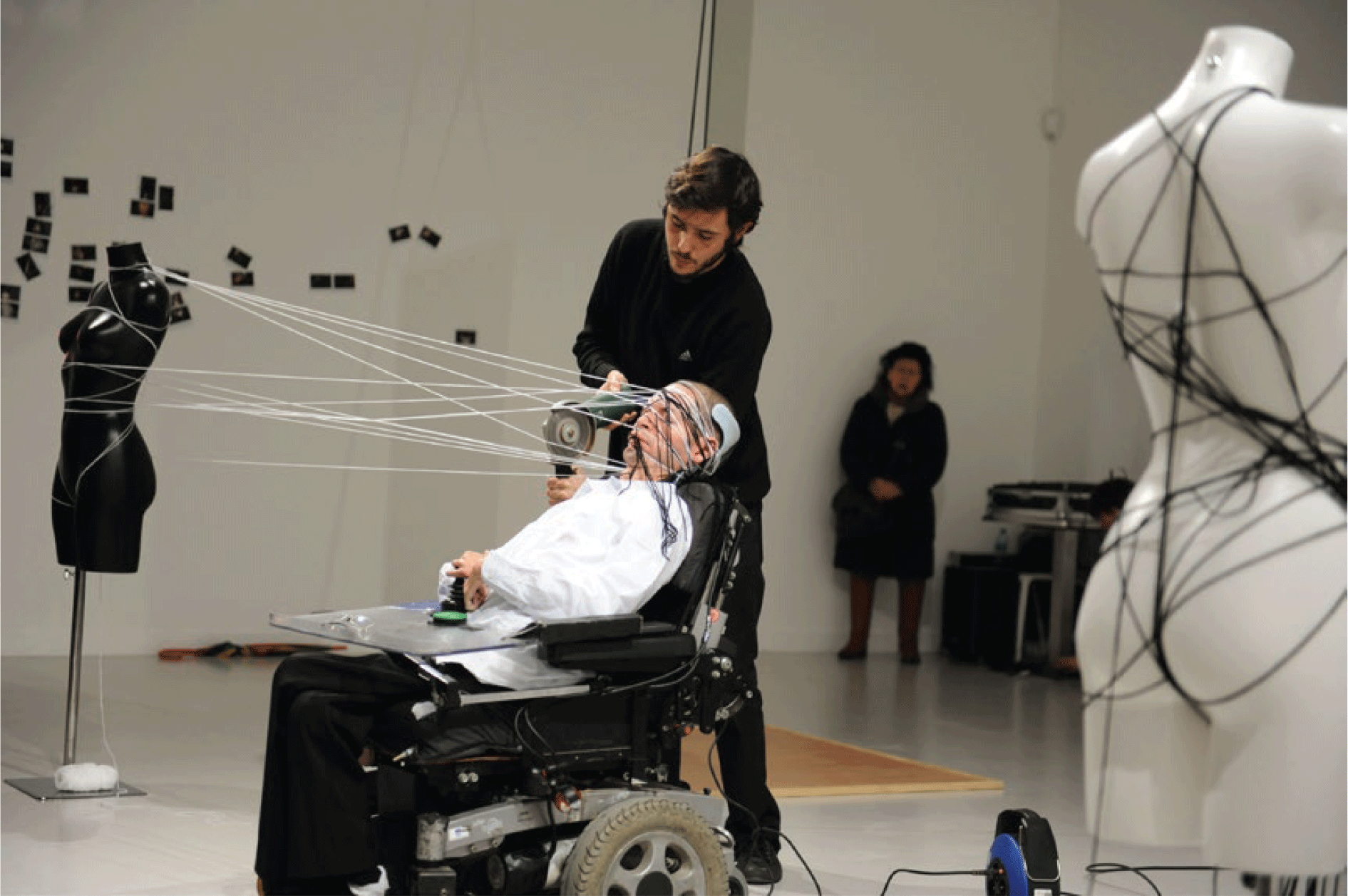

Guenatri’s art mainly focuses on exploring his physical dependence on assistants to help him perform basic daily activities. Guenatri calls them “the privileged witnesses of my daily life” (2023:6), compensating for what he cannot do alone. He refers to his body as “a manufacturing plant of poetry and actions” (3). In his performances, his assistants manipulate his defenseless body and perform specific actions that Guenatri establishes before each performance. Yet, his assistants seem to abuse his body, which ethically contravenes the care keeper’s duty.

In the 2014 performance cycle Le drame d’un homme, the symbolism represents aspects of disability that are related to transferences and transformations of memories of pain and suffering. In the performance in Berlin, Guenatri decided to be deprived of his prostheses, placed on a table by his assistant and positioned below the support axis of his motorized wheelchair. His assistant covered Guenatri’s vulnerable body with rose petals, leaving his upper and lower limbs naked, exposed to the gaze of spectators. In the performance at Centre d’Initiatives Artistiques du Mirail (Toulouse, 2014), another assistant wrapped a spool of thread around Guenatri’s face (fig. 13).

Figure 13. Kamil Guenatri. Le drame d’un homme. Centre d’Initiatives Artistiques du Mirail – La Fabrique, University of Toulouse, France, 2014. (Photo by Jérôme Carrié; courtesy of Kamil Guenatri)

Do we fall into an aesthetic hypnosis by watching Guenatri’s performances? Are they rituals of radical tenderness or cruelty? In an interview, Sarah Heussaff asked Guenatri: “Here, you are the free decider of these actions you impose on your assistants. It is like your mind inflicts these small, repeated acts of violence on your body through third parties. Can your assistants then be perceived as a physical demultiplication of your artistic thought?” Guenatri answered:

Before I got fully involved in performance, I asked social services to stop granting me aid through the voluntary sector and give me the allowances to recruit directly the assistants myself. It became necessary to do so because my practice is strongly linked to my daily life. My body is made of other bodies, those of my life assistants. It is essential for me that this exchange be desired and chosen. I really like this image of multihanded Indian deities like Ganesh and Shiva. In my practice, this corresponds in both directions: several hands and one head and several heads with two hands. When I develop my performances, the first images are mental and imagined by myself. The work with the assistants consists of giving them substance in the actions we carry out together. Their primary role is to compensate me for what I cannot do. This is precisely what they do in my daily life. They are liberating factors for my imagination. Our collaboration creates ambiguity and interests me because it questions the relationship with others. (Heussaff and Guenatri Reference Heussaff and Guenatri2016:159)

In Corpulences at KUB Galerie (Leipzig, 2014), another assistant cut lemons on Guenatri’s head, the stinging juice dripping into the performer’s eyes while he lay naked and motionless on a black mattress. In another part of the same performance, spectators were asked to take photographs of different parts of Guenatri’s body and then attach them to a wall underneath the phrase “THE HUMAN PERFECTION” (fig. 14). The purpose of Corpulences was to question and subvert ideals of physical perfection and beauty propagated by those who exclude people who do not fit those parameters. The photographs of parts of Guenatri’s body that were hung on the wall of the performance space created a new corporal form. As Guentari says:

In doing so, I confront a perfect symmetry on the wall with my body lying naked on the floor, transforming this ideal representation with parts of my body. I deconstruct physical standards and shine a light on the diversity and richness of our interior states […] to open a field of possibilities as a singular, diversified memory. (2023:26)

Figure 14. Kamil Guenatri, Corpulences. National Gallery of the Arts, Sopot, Poland, 2015. (Photo by Jurek Bartkowski; courtesy of Kamil Guenatri)

In 2015, Guenatri did Kamcel—perform the Other (Fiac, France) with German performance artist and body mover Marcel Sparmann (fig. 15). Guenatri described the work:

It is about a certain man that haunts my mind: an athletic man with symmetrical proportions who sometimes comes into my dreams, sometimes when all falls to pieces to let swift images show through. This man is strange because he comes each time with improbable objects and uses those to create splendid situations. Like the Wizard of Oz, a poet, or a performer, he is lost in the flow of symbols he conveys. I don’t know if this man tries to pass on elements of his existence or mine. Certainly, he tells me some stories. We discover each other a little bit more every time. I write all that he does in my notebook to never forget his appearance. Until now, this man was anonymous to me, but recently I have told this anecdote to a friend, and we decided to name him Kamcel. (in Sparmann Reference Sparmann2018)

Figure 15. Kamil Guenatri and Marcel Sparmann, Kamcel—perform the Other. Chapelle Saint Jacques Contemporary Art Center, Saint-Gaudens, France, 2015. (Photo by Lola Bernadi; courtesy of Kamil Guenatri)

The performance was the encounter between two different bodies (figs. 16 & 17)—the two performers considered the limits and communication between their bodies to create a performance dialog for the camera, entwining their imagination and embodying possibilities in different situations: public/private, inside/outside, and individually/together. Sparmann spoke of the experience this way:

Kamil considers the caretaker/assistant a coperformer. Kamil is the mind and spirit behind all the actions, but without his assistants, they would not take place and would not become a breathing manifestation of his mind and heart and, indeed, his punk attitude.

It is interesting how his assistants navigate the performance space between explicit instruction and improvisation. I felt complicity with Kamil and his assistants during the performance. I used my physical and mental capacities to make this work happen. I remember being very focused on small details while reflecting on topics like consent, ability, freedom, and dependency, the body as a breathing object, intimate and touching. I also questioned my physical limits and why I am doing performance art: What are my urgencies? Am I ready to fight for something or sacrifice something of myself?

From my perspective as

a coperformer/assistant,

the audience felt close and warm. Of course, there is

also a sense of fascination

for Kamil’s physical condition and appearance as an almost mystical, ephemeral figure, combined with a sense

of constant tension and compassion.

Before the performance, Kamil felt excited and nervous. The preparation was complex. Every performance is a hazardous endeavor for him. For example, the moment the caretaker takes off his orthopedic corset, Kamil’s vertebrae could get badly hurt because he has no muscles. Basically, he could die in these moments. During his performances, he is very focused and in a constant state of alertness and awareness, in a close connection with his assistant and the materials he wishes to use. He has to fully trust his assistants, for they execute actions on his fragile body. He is very aware of the audience. I know he enjoys every performance as a place of empowerment, a place to be seen and recognized as an artist beyond his physical aspect. After accomplishing a performance, he is exhausted physically, emotionally and spiritually—his performances are proof and a manifestation of images and situations he envisions and dreams of.

We often talked about his dreams—performing with a fit body and what he could possibly perform with such a body. The actions he dreams of guide what he does in real life. I felt great care and responsibility performing with him, which are necessary to handle his body without hurting it. I felt his trust and focus. I felt like performing two bodies, within two bodies, connected, disconnected, and connected again. I had the impression to become an extension of his body, merging together uncannily. The idea was I would become the abled body he dreamt of and accomplish further performances for him—to create a third person out of my body and his mind. It is a genuinely fascinating idea and task, but mentally challenging.

I felt his vulnerability very present inside me. Not that I felt vulnerable but that I could amplify or reduce the sense of vulnerability he transmitted during the performance. Assisting Kamil means embodying his energy and handing over your own to him for the entire course of the performance. It was osmosis between bodies, minds and imagination—ours and the audience’s—as if navigating an ocean of floating visions about the profoundness and fleetingness of our human existence. (Sparmann Reference Sparmann2023)

For Guenatri, the image of the puppet and the puppeteer shows his kind of freedom: consenting to let another body manipulate his body. We are left with the thought that these abusive acts cause suffering. Still, for the French Algerian artist, pain is relative and symbolic; it arises mainly from fear, for the mind is the channel of all forms of bodily suffering. Guenatri wants to demonstrate that he is the free decider of all these actions that mishandle him. He looks at his body as a site of action and self-reappropriation—a blank canvas to fill, oscillating between movement and immobility, between full force and fragmentation. What mainly interests him is the body as a tool for visual composition. For example, in the performance cycle L’infini equilibre (2013–2016), inspired by Yves Klein’s anthropometries, Guenatri had spectators paint his whole body black (fig. 18). Guenatri explains:

This action is an attempt to disappear through camouflage, using monochromatic canvases. It conveys ideas of extension, overlapping, and multiplication of the body, bridging performance and installation by leaving a trace, but also installation to performance. I explore an indeterminate performative time in which the stillness of my body becomes an installation of itself. (2023:20)

Committed to confronting stigmatization, Guenatri tests his body’s limits. The images, performances, and situations he creates are also a way to deconstruct his mental and physical spaces. He deploys his body to evoke the fragile frontier between impossibility and hope. He reimagines his disabled body as language, seemingly a body without organs.

Figure 16. Kamil Guenatri in Kamcel—perform the Other. Kamil Guenatri and Marcel Sparmann. Chapelle Saint Jacques Contemporary Art Center, Saint-Gaudens, France, 2015. (Photo Lola Bernadi; courtesy of Kamil Guenatri)

Figure 17. Marcel Sparmann in Kamcel—perform the Other. Kamil Guenatri and Marcel Sparmann. Chapelle Saint Jacques Contemporary Art Center, Saint-Gaudens, France, 2015. (Photo Lola Bernadi; courtesy of Kamil Guenatri)

Figure 18. Kamil Guenatri, L’infini equilibre. Centre d’Initiatives Artistiques du Mirail – La Fabrique, University of Toulouse, France, 2014. (Photo by Jérôme Carrié; courtesy of Kamil Guenatri)

Furthermore

Performance and disability raise complex questions about the tension between the desire to show that people are all the same and the desire to expose us to their differences. What distinguishes performances by performers with differentiated bodies, pop TV shows featuring people with disabilities, events like the Paralympics, and old-fashioned “freak shows”? Are “freak shows” having a second life? What does the viewer see and receive? Is it voyeurism disguised as activist art?

In the 18th and 19th centuries, representations of disabled people were historically confined to the sideshow, the freak display. As Rosemarie Garland-Thomson analyzed in the introduction to her seminal Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (1996), the freak body, deviantly different, shown to entertain and amuse, becomes the other that serves to increase and comfort the “normal” identity of those who look at it, allowing the public to deny and suppress disagreeable aspects of their selves. In an era of social transformation and economic reorganization, the 19th-century freak show was a cultural ritual dramatizing the epoch’s physical and social hierarchy.

Today, performers with differentiated bodies affirm their differences. Live performances such as those discussed in this article and antidiscrimination legislation undermine the permission the old freak shows granted their audiences. We can no longer point, giggle, and forget. We are called to reflect on our own existence in relation to others who are different from us. The differentiated body breaks the rigidity of certainties about the body. This is true even in the face of popular culture and everyday obsessions: one’s image on social media often manipulated by filters to reduce what are considered imperfections, TV series that exalt beauty, the exponential increase in medical methods such as Botox and cosmetic surgery to “normalize” bodies, even the proliferation of closed-circuit cameras scanning all bodies.

The human body is a world of flesh. It is symbolically “a construction born of sensoriality filtered through our social and cultural condition, personal history and attention to the surroundings” (Le Breton 2017:2). It is a matrix of self-recognition and culturally anchored ways of interacting. The habit of gazing at disabled people is difficult to abandon. The medical gaze reads, interprets, and identifies bodily differences as abnormalities, which society in turn stigmatizes based on the hegemony of the gaze, leading to structural inequalities and systemic oppression. Often these are expressed as depression and illness on top of disability.

By performing their bodily differences and exposing their illnesses publicly, performers with differentiated bodies actively resist preconceived notions of illness that cast disabled persons as helpless passive individuals on whom others act and make decisions—medical personnel, caregivers, and family. Performers like Bufano, Monteiro, Fornoni, and Guenatri change the other’s gaze from pietism, mockery, or embarrassment into a profoundly human, nonhegemonic gaze. Their poetic revolt aims to overcome resistance to change and to find a new autonomy through that resistance.

Disability in the collective imagination is often an unseen or ill-defined presence that is therefore shocking. It places itself on the edge of consciousness between the known and the unknown, the perceived and the unperceived. Performers with differentiated bodies break down representational categories and, as a result of their will to act and be, destabilize the image of disability as a physical weakness or distant other. Disability does not fit traditional binaries and threatens to disrupt dominant, institutionalized knowledge that pigeonholes diversities into categories. Disability as represented by these artists points to unexplored terrain without precise contours, which few can comprehend.

If these performances were limited to addressing disability issues, their profound message would be lost. They would be static artistic operations. Instead, they should be read as incursions into the performative space generating original narratives that provide a mirror for a changing society.

The stigmatizing gaze resembles voyeurism: excitement and pleasure aroused exclusively by looking. To be a voyeur is considered unethical in terms of sexually deviant behavior. Some voyeurs also enjoy seeing people in distress. However, when taken as a research method, voyeurism connects many useful behaviors such as curiosity, the strong desire to know or learn something, and a sympathetic understanding of people. Voyeurism involves reflection and participation at a distance without disturbing the object investigated. In the cases offered here, the performer with a differentiated body, who with her or his presence affirms the vulnerability of life beyond the condition of ordinary social “reality,” embraces the dream and the newly created world. The artists discussed here perform rituals for life renewal in the Artaudian sense. They highlight vital energy as the basis of existence. It is also true that Artaudian magic—the idea of “organized anarchy” as a philosophy of experimentation and creativity to disrupt dogmatic rules and commonplaces (Artaud [Reference Artaud1938] 1958)—is seldom realized, especially when differentiated bodies are rendered harmless by media that reinforce stereotypes about disability.

In the relationship between disability and beauty, disabled people are linked to a form of “subversive sensualism” (Hahn Reference Hahn1988:28) that challenges traditional gender roles, stereotypes, and the idea that disability is a negative attribute that must be met with pity. When the vulnerability of the differentiated body is present and presses on the sensitivity of those close to bodies it is usually kept at bay by the label “disabled.” But in performance, the vulnerability (imagined and otherwise) of the differentiated body pairs with strength and resistance.

The encounter between spectators and a performer with a differentiated body is qualitative. The performer brings living energy; they are engaged in a journey between immediacy and mediation, art and everyday life. It is as if the eyes of the spectator gain a haptic function in addition to an optical one showing the distance between the extraordinary body and the average body. Thus, the encounter becomes an attempt to create a unified collective that strives to surpass ordinary detrimental labels regarding disability.

The artists presented here embrace their daily, physical, and existential discomfort in their performances as a tool to propose an alternative way of understanding social interaction. Despite the Artaudian cruelty of exposing their vulnerability onstage, their performances are vibrant, problematic, radical, and structural, undermining the traditional separations of the private and the political. However, for all that, the performances do not necessarily reposition disability in the reality shared by the abled and the disabled.

Disabled people are still unseen by most people—unable to participate in daily life, so essentially invisible. A major cause is the significant number of physical and social barriers that hinder their full integration into the public sphere and their continued lack of agency regarding their daily life experiences. Normalizing the social perception of disability and addressing negative attitudes, prejudices, and stereotypes is the most significant challenge that artists with disabilities face. Although an estimated 1.3 billion people experience significant disability, representing 16% of the world’s population—1 in 6 of us (WHO 2023)—media representation of people with disabilities is anchored in stereotypes and societal stigma.

Physical signs of difference related to disability cause prejudice, labeling, loss of status, and discrimination. Celebrations such as the International Day of Persons with Disabilities or World Down Syndrome Day usually receive only brief mentions in the media.Footnote 7 The occasional participation of people with disabilities in popular television programs and films is still news and often controversial. As important as it is to include disabled people as much as possible, it remains an open question if, for example, disabled fashion models shown as chic and exotic benefits the social integration of disabled people.

One might rightly argue that displaying disability as just another example of normal social variation in pop television programs and films is not realistic but an idealized expectation. What is needed instead is to support an accurate image of disability that strongly contrasts with the old visual rhetoric of the exotic, the wonderful, the pitiable, and the freakish. No disabled person asks to be considered and accepted as an exceptional exception but as someone equal and as worthy as all other people. Disabled athletes continue their fight to obtain equal rights. For example, 27-year-old fencing champion and multiple Paralympic medalist Beatrice “Bebe” Vio Grandis, similar to Lisa Bufano, contracted Type B Meningitis at age 11. The following year, her necrotized forearms and legs were amputated. After her second Paralympic gold medal in Tokyo 2020, she become brand ambassador, spokeswoman, and the New Global Face for L’Oréal Paris. In 2021, she brought the issue of disability to the European Parliament.

The problem is that the complexity of understanding and accepting disability is scarcely reflected in media representations that range from simplistic, cruel, and discriminatory frames anchored in stigma and stereotypes to more positive and motivating discourse that improves equality. The effective inclusion of people with disabilities in the public sphere, together with the normalization of the overall perception of their role in society and the progressive removal of stereotypes and stigma, depends to a large extent on the visibility provided by the media.

If disability is “a socially constructed definition of existence and nonexistence that is perpetually being redefined and re-enacted every day” (Bierdz Reference Bierdz2023:223), indeed, the question that lingers is whether performance can change “the dominant biomedical construction that affirms that the disabled body can be considered an aberration, and is imperfect and abnormal” (Santos et al. Reference Santos, Moreira and Gomes2020:3147).

Bufano, Fornoni, Guenatri, and Monteiro control their personal narratives when they perform. Their works reinforce the idea that disability does not limit one’s potential but can contribute to a cultural shift that embraces diversity and reflects the richness of the human experience. Their performances foster empathy and understanding among audiences. They enact the breakdown of societal barriers, increasing awareness of lives of the disabled and encouraging a more accepting and open-minded community. Performance allows spectators and audiences to actively participate in inclusive environments that create new opportunities for everyone.