A personal recollection: When I first arrived at Merce Cunningham’s studio in 1978 it was a breath of fresh air for me, a palpable relief, to be asked to dance, simply dance, without playing a role or evoking any emotion other than what I might actually be experiencing at the moment of performance.

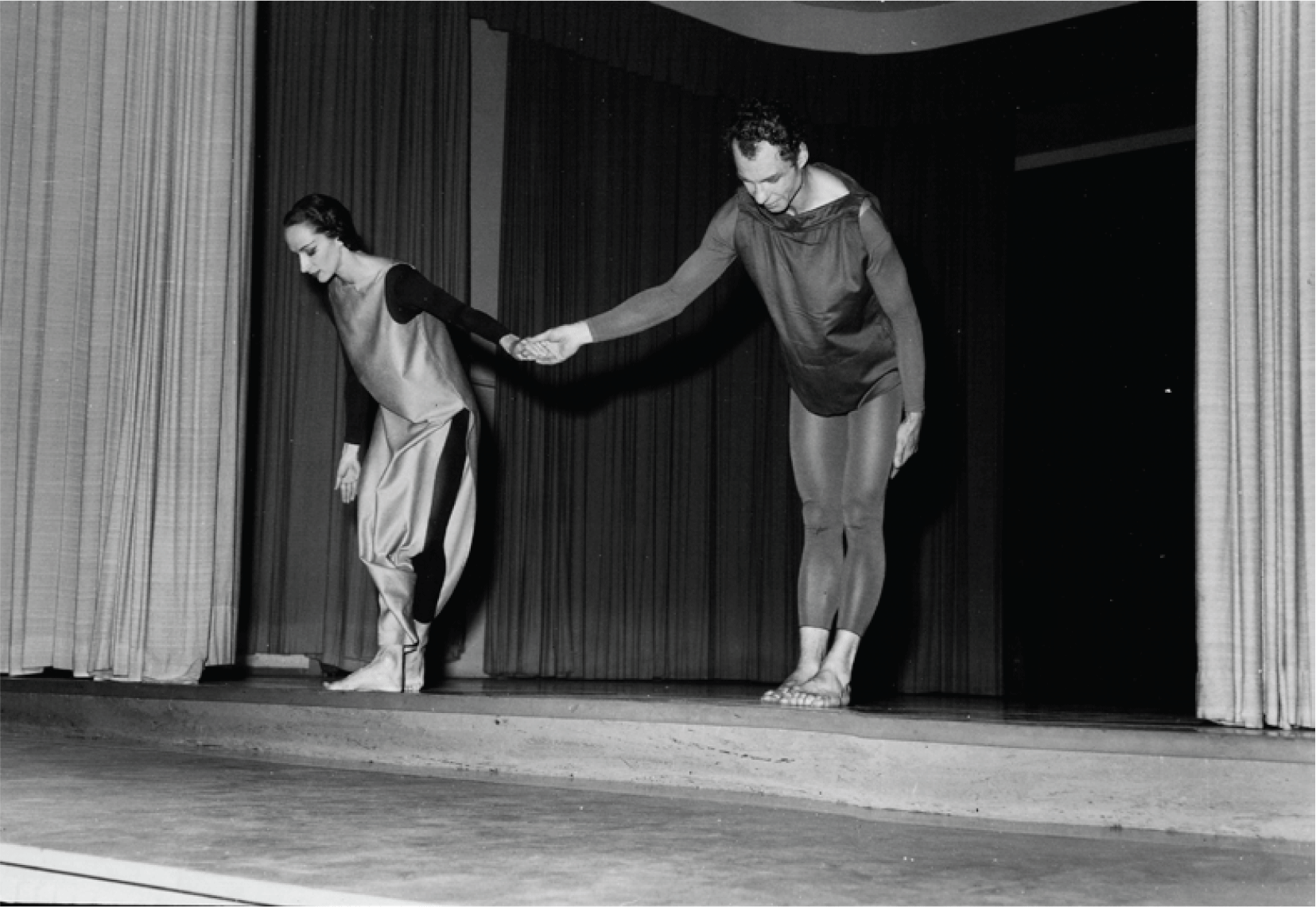

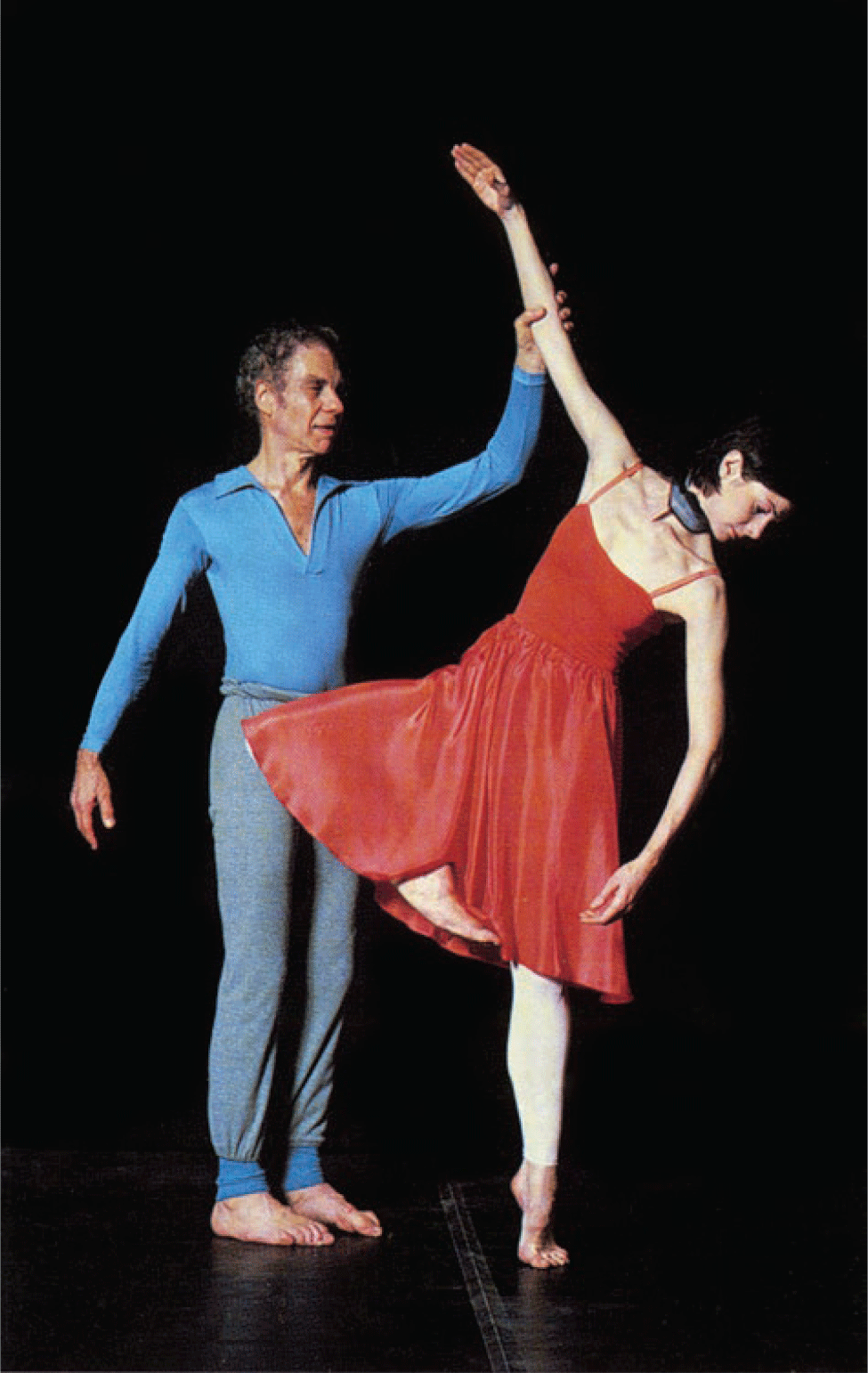

Figure 1. Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham bowing after a performance of Night Wandering (1958) from a performance in Cologne on 5 October 1960. Note the gender conventions of their bow, with Brown in a curtsy and Cunningham with his weight on both feet, supporting her. (Photo by Peter Fischer; courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library, with permission from the photographer’s estate)

Previously, when dancing in the work of other, more traditional modern dance and ballet choreographers, I had been asked to express predetermined emotional states or play roles in a narrative, usually some version of the young heterosexual lover. I don’t imagine I was convincing in the least, given that I had trained to be a dancer, not an actor, and had no personal experience as a heterosexual lover. More importantly, my attempts to embody these straight roles felt dishonest, like I was hiding an inescapable and hard-won aspect of my identity.

I was relieved that my charge in Cunningham’s work was to go onstage and simply dance: I no longer had to hide my sexuality. Within Cunningham’s work I found permission and encouragement to be both my gay self and a dancer, to dance queerly.

My thoughts toward a queer reading of Cunningham’s work began incubating while I was a member of his dance company from 1980 to 1986, yet I only began noting these down on paper two decades later while completing my MFA. I now return to that moment in 2007 when I began to examine my early encounters with Cunningham and how I have reckoned with his work over the years. I draw in part from my own experiences within the company and from previously unpublished interviews I conducted in support of that 2007 project, with: Cunningham; original company member Carolyn Brown shortly before the publication of her memoir Chance and Circumstance: Twenty Years with Cage and Cunningham; and David Vaughan, who began his work as an archivist for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in the 1950s. I have made available full-text transcriptions of my interviews with Cunningham, Brown, and Vaughan should they prove of some value to others interested in Cunningham’s life and work.Footnote 1

I employ the term “queer” in this article, yet I identify more readily as gay. I came of age in New York in the late 1970s into the ’80s when license to publicly identify as gay was still a new possibility. The reclamation and repurposing of the one-time slur “queer” by activists and other, well, queers, was largely still to come. Hence “gay” is usually the first term to spring to my lips, and I remain relieved and proud to utter it.

Cunningham, 40 years older than me (and a day, to be exact), was much less comfortable with any term that might signal homosexuality, and no wonder. He was born in 1919, moved to New York in 1939 at the age of 20, and started his dance company in 1953 in the midst of the McCarthy era.Footnote 2 During those years, homosexuality was criminalized and widely viewed as deviant. Few were those who dared to come out of the closet and publicly identify as queer. Cunningham and John Cage, his artistic collaborator and lover, were not among them.

I offer three main premises on which I base my hypotheses about the impact of Cunningham’s negotiation with the closet in shaping his aesthetic perspective and practices. The first two premises might be seen as positive, value-added contributions made by this negotiation; while the third premise, which considers the ubiquity of mixed-(cis)genderFootnote 3 duets throughout Cunningham’s work, I view as an area in which the closet might be seen to have triumphed. Any such consideration of Cunningham’s (homo)sexuality in relation to his artistic work deviates significantly from his own wishes and from the persistent party line that such biographical information is immaterial to an understanding of his art. Indeed, when I asked Cunningham if he feels issues such as sexuality can be relevant in looking at an artist’s life and work, he replied with a definitive, “Not to me” (2007:43). So I am reading “against the grain” (Feuer Reference Feuer and Jane C.2001:387), to reclaim the “constitutive and underrecognized role” (Desmond Reference Desmond and Jane2001:3) that Cunningham’s sexuality may have played in his work, following the now-established lead of scholars and other cultural workers, such as Jane Feuer, Jane Desmond, and Jill Johnston, who believe that “the work artists make not only evolves from the traditions of their media but also arises directly from their lives and times” (Johnston Reference Johnston1996:14).

There’s a lurking conundrum regarding meaning-making in relation to Cunningham’s work. Perhaps the primary explanation Cunningham has offered holds that “the meaning of the dance exists in the activity of the dance […;] a jump means nothing more than a jump” (in Guthman Reference Guthman1953:107). This account can lead to what Carolyn Brown argued is the “simplistic propaganda that his dances have no meaning” (2007a:56). Indeed, Brown’s view that Cunningham’s dances do have “secret and not-so-secret meaning” is the primary message of her book. She found “spiritual, psychological, sociological, physical, chemical, emotional—whatever” meaning specific to individual dances (273). My arguments rest less on interpreting individual dances than on what might be viewed as “discursive” (Caroll Reference Caroll, Fancher and Myers1981:101) meanings performed by Cunningham’s body of work, working methods, and practices.

To return to Brown’s assertion of “secret and not-so-secret” meanings deposited in Cunningham’s work, Brown wrote that Cunningham “relishes conundrums and riddles, and his skills in deception are Promethean. He’s like a fox, agile and sly, unexcelled at putting people off his scent” (2007a:165). She also reported on what she deemed his “devious behavior” when it came to discussing his own work, offering as a prime example the remark he added to his explanation of the movement creation for Minutiae (1954), an early work: “at least that’s what I replied when asked” (53). In other words, he admits to a party line of sorts from which aspects of the truth might be at variance. I take this into account when considering some of Cunningham’s more puzzling claims made during my interview with him, such as his insistence that he never perceived any stigma from being a male dancer or a gay man. Indeed, Cunningham might be viewed as tantamount to a hostile witness regarding any query that might take him away from his preferred messaging about his sexuality, which is no messaging at all.

Premise 1: Having to do with Movement-as-Movement as an Alternative to the Closet

It is my first main premise that Cunningham’s separation of dance from literary, narrative, or (predetermined) emotional expression opened a space for a lesbian and gay dancer, as for any dancer performing his work, to perform onstage without requirement to conceal their sexuality or any other aspects of their identity.

When I danced in the Cunningham company, I’m afraid I understood this permission as encouraging a “naked exposure of the self,” as Carolyn Brown put it in her Chance and Circumstance (2007a:39), as if there is a complete and clear self that is possible of being either hidden or expressed, an authentic, primary self that is not constructed, in flux, and performatively constituted. Indeed, I can now recognize that while in the Cunningham company I was performing, onstage and off, as a version of “a Cunningham dancer,” among other constructed aspects of my developing self. I continue to maintain, however, that within the performance of that identity there was room for me as a queer that didn’t exist in the work I had performed prior. Indeed, the home page of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company website, for years prior to the disbanding of the company, featured a declaration attributed to Cunningham from 1967: “My work is—or at least what I attempt to do—is to take each person for what they are”Footnote 4 (in MCDC 2006).

I hypothesize that Cunningham may have experienced a dissatisfaction as a dancer/performer similar to mine, and that freedom from playing roles that didn’t suit him may have initially accounted for some of his attraction to the new, nonnarrative manner of presentation he was discovering.

Susan Foster, in “Closets Full of Dances: Modern Dance’s Performance of Masculinity and Sexuality,” characterizes Cunningham’s avoidance of narrative and representation in his dances as constituting a closet: “In [his] focus on movement and on the individual response to and interpretation of that movement, Cunningham found protection for his homosexual identity” (2001:174). While I find validity in Foster’s point, I’m proposing a divergent, even paradoxical, reading. With the same aesthetic practices by which Foster proposes Cunningham has constructed a closet, I see him as also having taken a step in defiance of the closet.

I’m in sympathy with Jonathan Katz’s argument regarding John Cage’s—and by extension, Cunningham’s—“deepening involvement with Zen and his concomitant turn toward an antiexpressive art” (Katz Reference Katz1999). Katz sees this turn as motivated, in part, by the closet, while also understanding Cage’s antiexpressivity-through-silence, as “not only a symptom of oppression but also a chosen mode of resistance.” The same can be said of Cunningham’s movement-as-movement ethos.

The notion of Cunningham’s work as antiexpressive has been put under pressure not only by Brown (“secret and not-so-secret meanings”) but also by Mark Franko, who argues that “Cunningham’s dissociative practices have come to be interpreted as a far more radical alternative to expression theory than his writing and performances actually indicate” (1995:77).

To Franko, in spite of Cunningham’s severing of the traditional relationship between music and dance (dancing to music), and his use of chance procedures to disrupt traditional notions of continuity, he nevertheless purveyed “expressivist values, albeit in an original way” (77). Instead of manifesting inner turmoil or euphoria, the imposition of psychological meaning, or the enactment of narrative circumstance—all expressive forces in the work of Martha Graham and her contemporaries and antecedents—Cunningham’s art relied on the subjectivity of the dancers and their unique execution of the movement. Because “they did not play roles but remained resolutely themselves, Cunningham’s dancers did appear as psychological and social agents” (84). In Franko’s reading, with which I am in agreement, the effect of Cunningham’s work relies on each dancer investing their performance with their own subjectivity. I propose to extend this understanding to encompass queer subjectivities.

Brown seemed, when I interviewed her, to have little patience for my premise. She felt that while the absence of role-playing in Cunningham’s work did provide freedom to “deal directly, one on one, with movement, rather than ideas about it or…story ideas basically,” she didn’t see making the connection to identity, to “being free to go onstage as oneself,” as I put it to her then (2007b:3). Yet in contradiction to her protestations I find many instances within her Chance and Circumstance that support my interpretation, albeit in a register, like mine at the time of our interview, void of acknowledgment of the cultural construction of identity. Of the first dance by Cunningham that Brown saw, Suite for Chance in 1952, she noted “the naked exposure of the self […]. It was not, however, the self-exposure of the choreographer that was offered but that of each of the dancers, including Cunningham himself” (2007a:39). Regarding the challenge of performing Suite for Chance herself, she wrote that the dance is “divested of all the dramatic, romantic, sentimental, or sensuous artifices that theatrical dance usually offers as protection from revealing the self” (49). Brown’s reading here is consistent with mine, emphasizing the “exposure of the self” that Cunningham’s work allows, even requires.

David Vaughan expressed cautious agreement with my hypothesis, concurring especially that it “absolutely” makes sense that the attraction to Cunningham of a nonnarrative approach may have been related to his dissatisfaction with the roles he was asked to play within Martha Graham’s work, roles that didn’t fit him, or that constrained him. Vaughan added that though he’d never heard Cunningham make this connection in an explicit manner, “I certainly have heard him say he objected to the stereotyped kind of character that Graham always had him play, but it probably wasn’t a heterosexual lover. It was more the sort of faun-like role” (2007:15). So the alternative to hypermasculine, heterosexual roles was creaturely characters, impish and mercurial—not romantic leads. As Vaughan noted, “Erick Hawkins was in the company at the same time, and they [Graham and Hawkins] were married, so…[laughs]…he would get the lover role” (16).

In my interview with Cunningham he, true to form, denied feeling dissatisfied with the roles Graham gave him, asserting instead that his dissatisfaction was with “the whole thing about expression” (2007:23), in direct opposition to Vaughan’s recollection that he “certainly” had heard Cunningham object to the faun-like parts Graham gave him. Another of Cunningham’s statements provides further insight:

[A]round about the third yearFootnote 5 I was there [with Graham], I began to think, “I don’t think I want to do this.” I don’t know what…I certainly didn’t, then, but […] the kind of movement that she did was meant to express something. And somehow that…I don’t know why, but it didn’t agree with me. (2007:14–15)

While Cunningham went on to give his standard explanation that his problem with expression as a movement instigator was the limitation that expressive concerns place on movement, I suspect that this may be an interpretation after the fact. His earlier response, “I don’t know why, but it didn’t agree with me,” may be more to the point. After all, Cunningham’s early solos were still clearly in an expressive mode—for example, Root of an Unfocus (1944), which Cunningham once described as “about fear” (1968). Cunningham also was still creating narrative works, including his “dance-play” Four Walls (1944), a family drama. So if emotional expressivity, psychological motivation, and narrative weren’t yet acknowledged problems for Cunningham, what was it that “didn’t agree” with him?

I suggest that at least part of the trouble for Cunningham was the unavailability of expressive roles that might allow him mature agency, a collision with the limitations of narrative conventions that allowed no legitimate possibility for representation of queer lives. The roles that Graham gave him were limited, and therefore limiting: a whole register of human existence—sexuality—was disavowed. In short, there was no societally acceptable narrative available for Cunningham as a gay man, so he abandoned narrative.

Further, I find it plausible that a discomfort with having to enact heterosexual narratives—including those in which his character was effectively neutered—may have led Cunningham to recognize his unease with the received assumption that movement must necessarily have expressive intention. Certainly an effect of Cunningham’s project of focusing on the movement itself rather than on narrative or psychological motivations—if not both cause and effect, as I propose—is the permission his choreography allows each dancer to perform as themself, dancing. In my interview Cunningham agreed with this, echoing his 1967 statement that one of his choreographic aims is “to take each person for what they are.”

Not long after I began studying at his studio, I heard Cunningham make a tightrope analogy during a choreographic workshop, which made a significant impression on me at the time: Each dancer must walk a tightrope. Off one side lies “the step,” which I understood as the choreography: the rhythm, shape of the movement, and other assigned dance values. Off the other side is the dancer themself, with their particular body, training, and movement affinities, by which I believe he was also referring to a dancer’s personal history, temperament, and other qualities of character. (“No two people walk alike,” as his familiar adage goes.) The dancer’s job is to balance between the two without falling to one side or the other, not committing so exclusively to the step that the dancer’s individuality is forfeited, and not personalizing the movement to the point that the choreography is compromised.

This tightrope image continues to be illuminating for me, relevant to choreographic concerns as well as to life concerns more broadly. It’s so complex and nuanced, how the tightrope operates—what this call for action, this opportunity, can produce. It’s a part of the Cunningham experiment that is too often overlooked: just what is engendered through the intersection of a particular “step” with a particular dance artist, or, more broadly, through the intersection of a particular demand, task, or life exigency with a particular person, and at a particular time. Even considering a dancer’s body as a starting point is to take into account all the knowledge living within and produced by that body, rising from a matrix of lived experience, and shaped by a specific context of time, place, training, and culture. While I am not sure Cunningham meant his analogy to be interpreted so widely and with these implications, I’m also not convinced he didn’t.

When dancers performing Cunningham’s work fell off this tightrope, I’d say they (we) usually fell toward the “step,” from whence came the oft-heard accusation of Cunningham dancers as onstage automatons.Footnote 6 More rarely, a dancer would fall toward the other side of the tightrope, compromising the choreography. But when dancers made it their work to negotiate the demands of that tightrope—and I had the honor of dancing with and watching many of these souls—that’s when Cunningham’s work really took off for me, both as a fellow performer and as a spectator.

During the same workshop when I heard Cunningham make his “tightrope” analogy he provided another guidance that I took to heart: Dancers of his work should “make the movement as much as it can be without making it something else,” with “something else” including connotative expression. Taking into account the “tightrope” instruction for dancers to balance between the step and their own individuality, the notion of “making the movement as much as it can be” takes on the dimension of personhood, bringing one’s full being and multiple intelligences into play to the greatest degree possible without distorting the movement.

Indeed, Cunningham once said that he “could see who and what they [the dancers] were through what they were doing” (Cunningham and Sontag Reference Cunningham and Sontag1986). Each dancer’s very being was present onstage. For dancers like me—and Cunningham—the being onstage was gay.

Premise 2: Having to Do with Chance Operations and Cultural Construction

The second of my basic premises involves reading Cunningham’s use of chance procedures as an implicit acknowledgment of what is now termed “cultural construction”—the understanding that a great many human behaviors and attitudes explained as “natural” are rather performances of cultural norms and expectations. It is a well-established argument in the literature on Cunningham that his use of chance procedures was an intervention into disciplinary conventions and assumptions, his interrogation of “the natural” in terms of aesthetics. But such explanations discourage straying beyond the aesthetic realm to consider the kind of cultural or political implications that I propose. Further, I mean to put into play the possibility that a contributing factor to Cunningham’s capacity to perceive the constructed nature of his aesthetic world rested in his status as an outsider in the social world in two interrelated respects: he was transgressing dominant conventions for gender roles as a male dancer, and he was a gay man, fully aware that his desires were taboo and that acting on them was illegal.

A quick review: At the beginning of the 1950s, John Cage began using chance procedures in his musical compositions, making large charts for plotting rhythmic structures and then composing “according to moves on these charts instead of according to my own taste” (in Vaughan Reference Vaughan1997:58). Cunningham soon began to apply similar methods to his choreography—the first time in 16 Dances for Soloist and Company of Three (1951), a point of no return in the development of his aesthetic and practices. Though in 16 Dances Cunningham was still working with expressive behavior and psychological archetypes in the content of individual sequences, the structural arrangement of the 16 sections was determined by tossing coins, thus beginning his experiments with chance operations as an “objective” mode of decision-making.

I’m often perplexed by the rampant misunderstanding of how Cunningham utilized chance operations. For example, it’s not that he left his dances entirely “up to chance,” whatever that might mean, but that he utilized chance procedures to make some, but nowhere near all, choreographic decisions. Further, Cunningham’s methods for utilizing chance procedures were extremely labor intensive: conceptualizing each question subjected to chance operations; creating a concrete gamut of possibilities to be put into play for determining each question’s result; the application of chance procedures—achieved through dice, I Ching stalks, or computer—to calculate the outcome of each question; and then the work of setting those results onto actual bodies within the choreography. Further, this process often required him to contend with additional questions that arose during rehearsal, requiring yet more go-rounds of all these steps. This was by no means an easy way out.

Quibbles with mistaken understandings about how Cunningham applied chance procedures aside, I’m interested in why he continued this practice, to a lesser or greater degree, in all of his choreography after 16 Dances in 1951.

In a 1994 essay Cunningham indicates that he utilized chance procedures because it led to new discoveries and presented situations that challenged his imagination (1994:276). Nancy Dalva, a critic and admirer of Cunningham’s work, suggests two further reasons: firstly, because Cunningham didn’t like to, or couldn’t easily make choices; and secondly, as a means of “intentionally—if minimally—depersonalizing his work in order to open it out to the individual viewer” (Dalva Reference Dalva and Kostelanetz1992:180). This second reason points, I would argue, to the use of chance operations as emblematic of Cunningham’s move away from the primitivism of Graham’s work and its attendant conceptions of “wholeness” and “purity of unconscious instinct” (Copeland Reference Copeland2004:18). Cunningham, it seems to me, would have been prone to reject a conception of “wholeness” that excluded him by definition. The employment of chance procedures throws a wrench in the works of decision-making by “instinct” via a “voyage to the interior” (83).

In our interview, Vaughan lent support to my queer reading of Cunningham’s use of chance procedures, thinking it “quite reasonable” that to Cunningham there was attraction and value in disrupting convention for the sake of disrupting convention (2007:8). I would extend this line of argument further to suggest that Cunningham’s experience as a queer in the United States and as a male in dance, both stigmatized (and often conflated) identities, may have led him to an interrogation of other cultural conventions that might have otherwise gone unnoticed.

This theory relies, in part, on a prima facie association of a stigma associated with being a male dancer, which Cunningham, as indicated earlier, at first denied feeling. Later he reluctantly admitted, “I mean, it might have come up. But…but I didn’t think about it” (2007:13). Vaughan, however, like me, took it as a given that Merce would have felt some stigma: “Well, let’s face it. It’s something we’ve all faced in our own lives. I mean, when I first told my father I wanted to be a dancer he was horrified, because he didn’t think it was a suitable occupation for a young man… It was entirely about…you know, because it was effeminate to dance” (2007:18). Even taking into account cultural differences related to geography and era—Vaughan, only five years younger than Cunningham, was born and raised in London—I maintain that it would have been well-nigh impossible for Cunningham to have escaped awareness that being a man in dance was a violation of conventional gender roles, a transgression that left male dancers open to homophobic accusation.

Cunningham was more amenable to the part of my argument that rests on making a jump from aesthetic concerns to broader issues:

GREENBERG: When I see the dances, my mind starts thinking of things other than just the movement. I become fascinated in the movement, and it starts to open up other possibilities for me, in my thinking.

CUNNINGHAM: Yes.

GREENBERG: That’s one of the theatrical powers of your work, to me, and I start to think that more things are possible than I had thought—

CUNNINGHAM: Oh, yes.

GREENBERG: —not just about movement, but about…everything.

CUNNINGHAM: Oh yes, yes. No…exactly…exactly.

GREENBERG: And that’s what you aim to do, in some way…

CUNNINGHAM: Well, I don’t know about aim—

GREENBERG: No?

CUNNINGHAM: —but I do it within the movement scale. I certainly intend that. (2007:49–50)

As expected, Cunningham emphasized the aesthetic implications of his work process. A bit later, however, he agreed that his deviation from his own preferences could have political ramifications. He acknowledged that tastes can be taught and enforced by the culture in which one lives, and that what one’s society dictates is not necessarily the only way to be. “If people were a little more aware of that, that just because you do it, doesn’t mean that somebody else has to do it” (51).

Cunningham was not, I would argue, speaking about movement preferences alone.

Cunningham also agreed that his use of chance mechanisms provided a means to break through learned and often unconscious assumptions. Again, as expected, he initially accepted this idea only in regards to disrupting choreographic conventions (a mention of the received choreographic wisdom from Louis Horst, Graham’s mentor, elicited a hearty chuckle) (2007:8). But he eventually acknowledged chance methods as a means toward circumventing more explicitly social conventions.

In the following interview excerpt we are building on an exchange slightly earlier in our conversation in which Cunningham introduced examples of roles that dancers are often required to play, “[t]hat in ballet…it’s based upon the idea of the prince and the princess, and the prince supports the princess in some way” (16):

GREENBERG: Well, part of what I’ve been working on is this idea of social construction…that a lot of things that we’re taught are natural, or the right way to be, are really constructed by a particular culture. The idea that women are supposed to be princesses and men are supposed to be princes is constructed by a culture. And I’ve thought, for instance, that chance mechanisms are a wonderful…chance procedures are a wonderful way to get past—

CUNNINGHAM: To break that. Sure.

GREENBERG: —to break through some of the assumptions that we might not even know are acting on us.

CUNNINGHAM: Yes.

GREENBERG: You know, the things we’ve been taught—

CUNNINGHAM: Yes, yes.

GREENBERG: —that we haven’t unlearned yet.

CUNNINGHAM: Yes.

GREENBERG: And I’ve been thinking that one of the strengths of it, in your work, is that possibilities come up…not just the socially received possibility of the prince and the princess, for instance.

CUNNINGHAM: Yes, yes. (16–18)

Cunningham’s work proposes and performs the idea that all sorts of phenomena that might seem to be dictated by the fate of “the natural,” as well as phenomena like homosexuality that are by many stigmatized as “unnatural,” are in actuality caused by chance interactions, simultaneously unpredictable and determined.

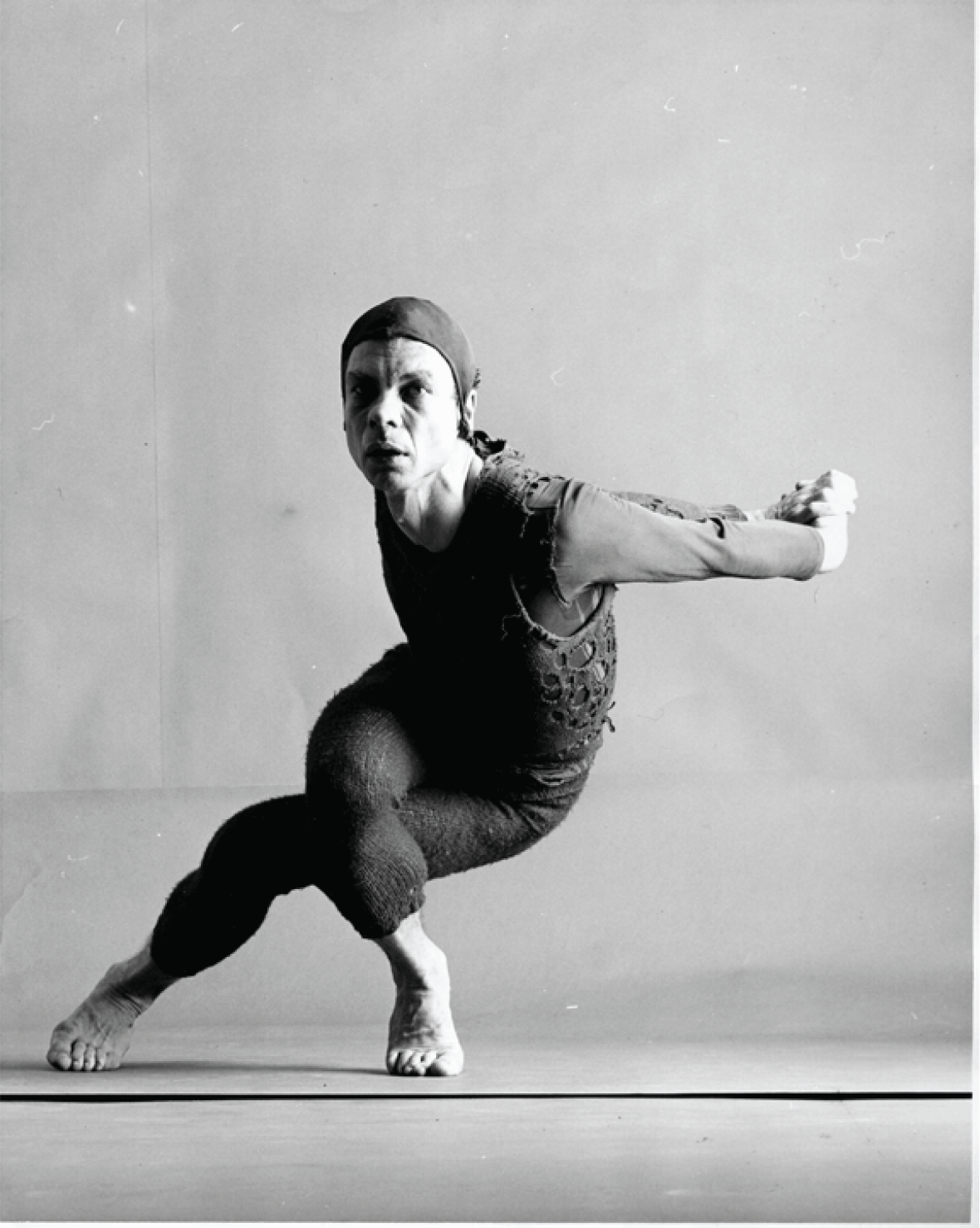

Figure 2. “He presented himself as aberrant, a deviant—grotesque and freakish.” Merce Cunningham in Changeling (1957). (Photo by Richard Rutledge, 1957; courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library)

Cunningham wrote of “chance as a method of finding continuity, that is, continuity thought of as being the continuum of one thing after another, rather than being related by psychological or thematic or other cause-and-effect devices” (in Dance Observer 1954:107). Could the causality of sexuality also have been at play for Cunningham? This must have concerned him as a queer man (it certainly worried me for many years). Surely Cunningham was aware of contemporaneous theories concerning the root causes of homosexuality—erroneous, oversimplified, and disparaging as they were. Wasn’t he searching for his own understanding of causes that would enable him to explain his sexual orientation?

If so, then the philosophy that follows from his use of chance procedures could also provide a nonstigmatizing explanation: homosexuality is just another phenomenon determined by complex chance interactions, neither a slip-up of nature nor a consequence of dysfunctional nurturing. Homosexuality “just is.”

In her discussion of Cunningham’s 1957 solo, Changeling, Brown made clear that Cunningham saw himself as different. “Merce often said he was sure that he had been a changeling—that is, a child who had been secretly exchanged for another in infancy. Perhaps it was his way to explain his odd-man-out-ness within his rather orthodox Catholic family.” Though Cunningham’s explanation is, of course, tongue-in-cheek, his feelings about his status as an outsider, which Brown could see in his performance of Changeling, may be more heart-on-sleeve:

Whatever he meant by the title and whatever the dance meant to him, words such as “desperation,” “anguish,” “torment” came to my mind when he performed it. Dressed in holey red woolens over a faded red leotard disintegrating with runs and rips, and wearing a red skullcap from which his ears protruded, he presented himself as aberrant, a deviant—grotesque and freakish. (2007a:190)

It’s striking how closely Brown’s account of Cunningham’s Changeling performance aligns with then-dominant views of homosexuality as unnatural (at best). Changeling may, then, reveal Cunningham struggling with being labeled a “deviant-grotesque” due to his sexual orientation, and may provide yet another view to his search for conditions of relation that evade causality.

If taken to its furthermost, Cunningham’s use of chance procedures would have resulted in an open field of activity in which all possibilities of movement and structure are allowed, accepted, and aestheticized, and no convention remains unchallenged. Of course, such a utopian outcome is impossible, as those procedures are necessarily being employed by an enculturated human person working, consciously or unconsciously, within many traditions. While a huge number of choreographic conventions are called into question throughout Cunningham’s body of work, there are still other conventions that remain quite intact.Footnote 7

Indeed, many have noted incongruities between Cunningham’s philosophies and his application of these in his work. Brown recalled “a curious discussion” between Cunningham and one of his hosts in India during the company’s 1964 world tour:

Bharati [Sarabhai…] peppered Merce with questions related to the stated Cage/Cunningham philosophy and use of chance procedures. If, in the music, any sound is music, any sound can follow any other—be it ugly or beautiful to the human ear—why is it that all the dancers in his company are tall and beautiful? Merce laughed, and said he’d always wanted to have a company of midgets. This of course, begged the question. Choice, not chance, was involved in the selection of dancers, as well as the composers and designers invited to collaborate with Merce. What were the criteria for these choices? Surely likes and dislikes played a crucial role. Surely it was not by using chance procedures that Bob Rauschenberg had been invited to design costumes, sets, and lighting? Both Merce and John seemed somewhat taken aback and uncomfortable under this intensive scrutiny and barrage of questions. (2007a:430)

Sarabhai’s point, with which Brown concurs, that a great many factors in Cunningham’s work are dictated by “choice, not chance,” leads to more questions: Why are some conventions and traditions left untouched, and others subjected to disruption by chance procedures? What cultural constructions escape the interventions of Cunningham’s methodology?

Premise 3: Having to Do with the Thorny Issue of Mixed-Gender Duets

Upon learning that I was approaching Cunningham’s work from a queer studies perspective, both Brown and Vaughan were quick to offer female-male duets as a relevant problematic. While this may seem self-evident, among many aficionados of Cunningham’s work the suggestion can still be met with outcries. So I’ll begin by stating the obvious: In the whole of Cunningham’s oeuvre there is a vastly greater incidence of mixed-gender duets that employ physical contact of some kind than of same-gender duets.

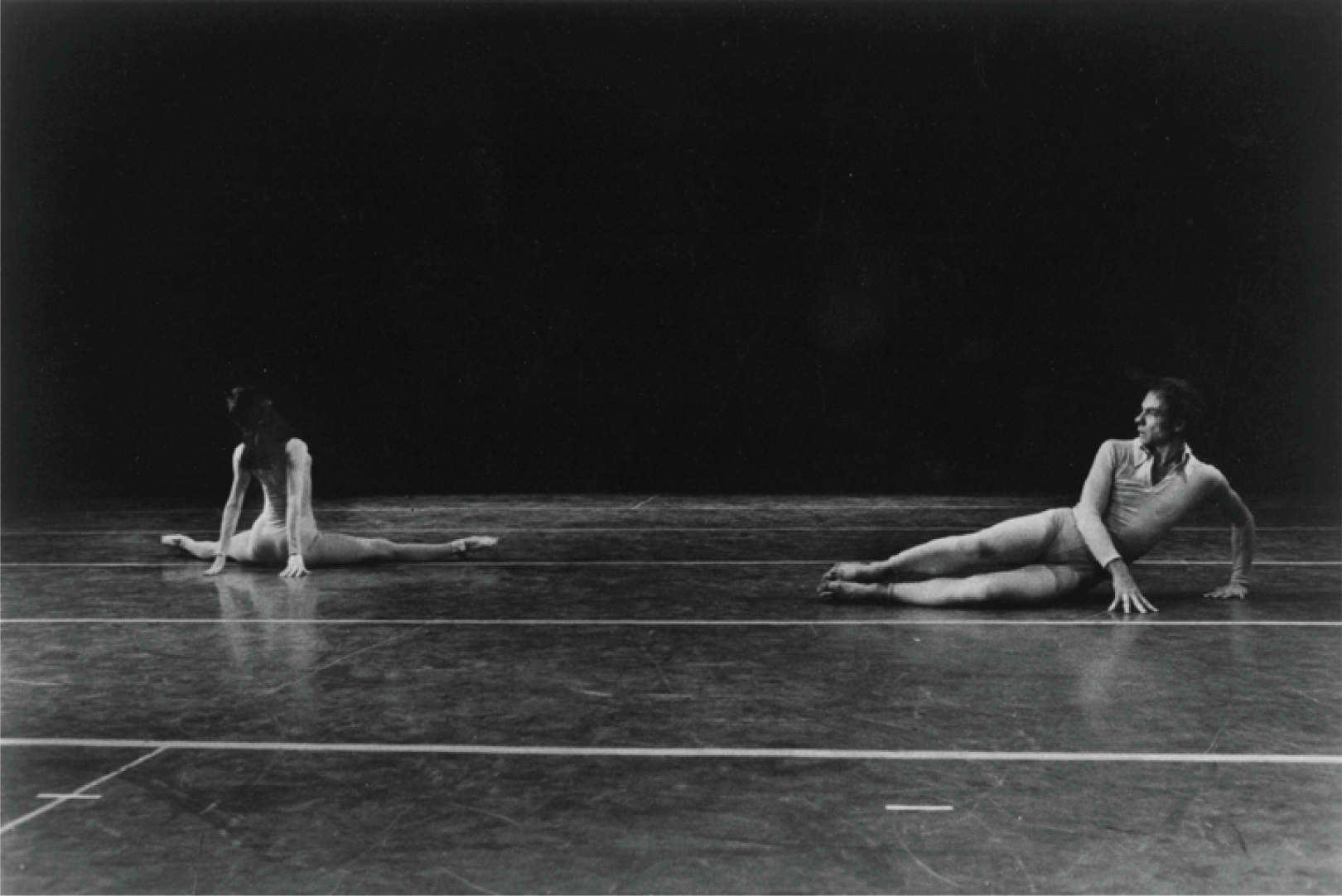

Brown and Vaughan each pointed to Cunningham’s 1970 work Second Hand as emblematic of this problem, seeing in this dance a clear disconnect between Cunningham’s philosophies and his actual practice. Second Hand was originally choreographed to be performed to the Socrate of Erik Satie. However, at the 11th hour Satie’s publisher refused to grant permission to use the score, so Cage wrote a new piece for piano that kept the structure and phrasing of Satie’s music. Nevertheless, Cunningham followed the musical structure of Socrate, and Brown and Vaughan believed he followed the dramatic content as well—implicitly if not explicitly. If so, this is an important exception to Cunningham’s usual working method of not allowing the structure of his choreography to be determined by narrative or musical structure. As Brown has told it, Cunningham’s duet with her from Second Hand “in the score, is really Socrates walking by the river with one of his male disciples” (see fig. 3). She noted that Remy Charlip, a previous member of the company, “found it, so to speak, dishonest. And he talked about it to John [Cage]” (2007b:5). Vaughan also remembered that Charlip “was outraged,” believing the duet should have been created for two men (2007:11). Both Vaughan and Brown seemed to accept Charlip’s objection. Here was a rare instance in which Cunningham was working with a preexisting narrative, and violating that narrative for what, they imply, were homophobic reasons. Any “straight-washing” of Socrates aside, however, Second Hand remains an anomaly within Cunningham’s choreography because of its direct relationship to both musical and dramatic structures. Yet within a broader look at Cunningham’s work the issue of the prevalence of mixed-gender duets remains, which Cunningham himself did not dispute in our interview.

Figure 3. Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham in Second Hand (1970). (Photo by James Klosty, 1970; courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library)

Cunningham provided the unconvincing rationale that he began this practice because “men were often not available” when he began making work (2007:19), a claim that, even if valid, might explain the absence of two men partnering, but not two women. He also fell back on his usual defense by offering that “a man and a woman dancing together” should be seen as “one of the possibilities. You can use it, if you want, for expressive purposes. But you can also simply use it as two human beings moving together” (18). Still, the question remains, if a duet is to utilize the possibilities of “two human beings moving together,” why can’t these human beings be the same gender?

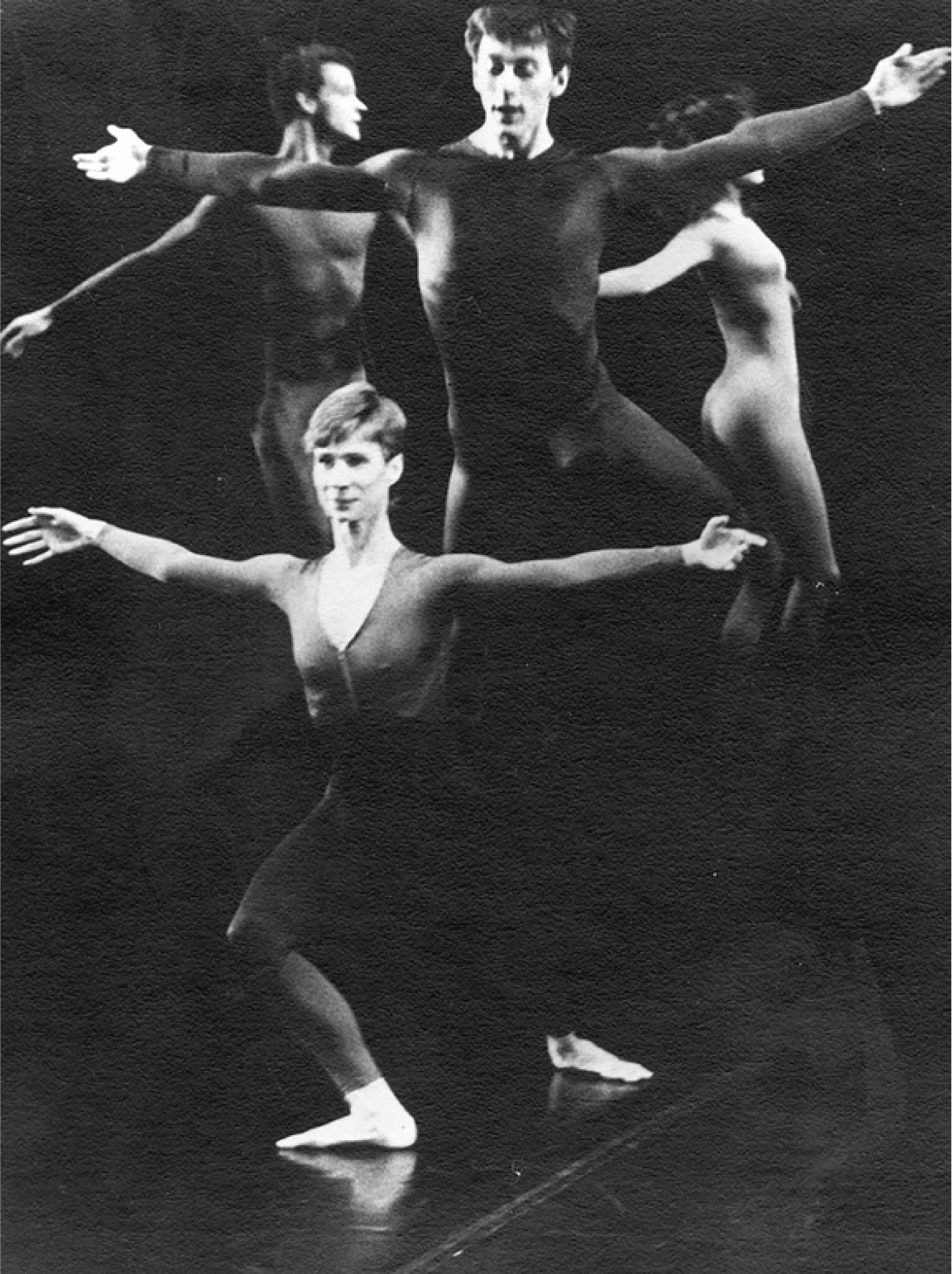

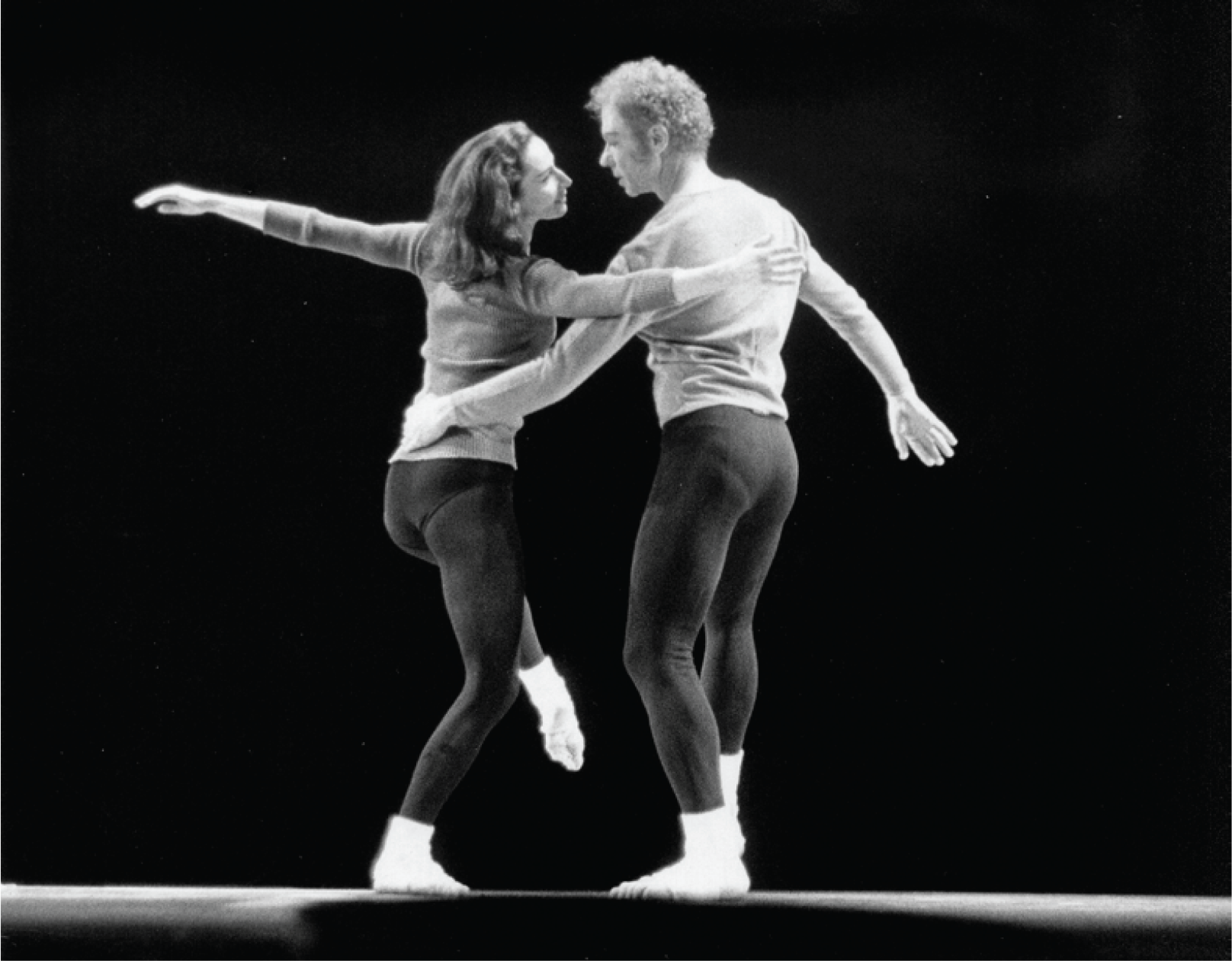

Indeed, Cunningham virtually defined the duet form as mixed-gender when in 1980 he created a dance that presents a progression of six duets, each between a cisgender man and a cisgender woman, and titled it simply Duets (see figs. 4 & 5).

Figure 4. Foreground, from left: Louise Burns, Neil Greenberg; background, from left: Chris Komar, Meg Eginton. Duets (1980) by Merce Cunningham, from an Event performance at Theatre National de Strasbourg (1980). (Photo courtesy of Neil Greenberg)

Figure 5. Merce Cunningham and Catherine Kerr in Duets (1980). (Photo by Nathaniel Tileston, 1980; courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library)

I can recall only one exception from my time in the company, a duet between two women as one of the five duets from Changing Steps (1973). The cast included six women but only four men, so after distributing dancers into the four mixed-gender duets there were two women “left over,” so to speak. While the two women touch hands and elbows in their duet together, they do not support each other’s weight in any significant way. Each of the four mixed-gender duets, however, includes instances of weight-sharing in which the man lifts or otherwise supports the weight of the woman.

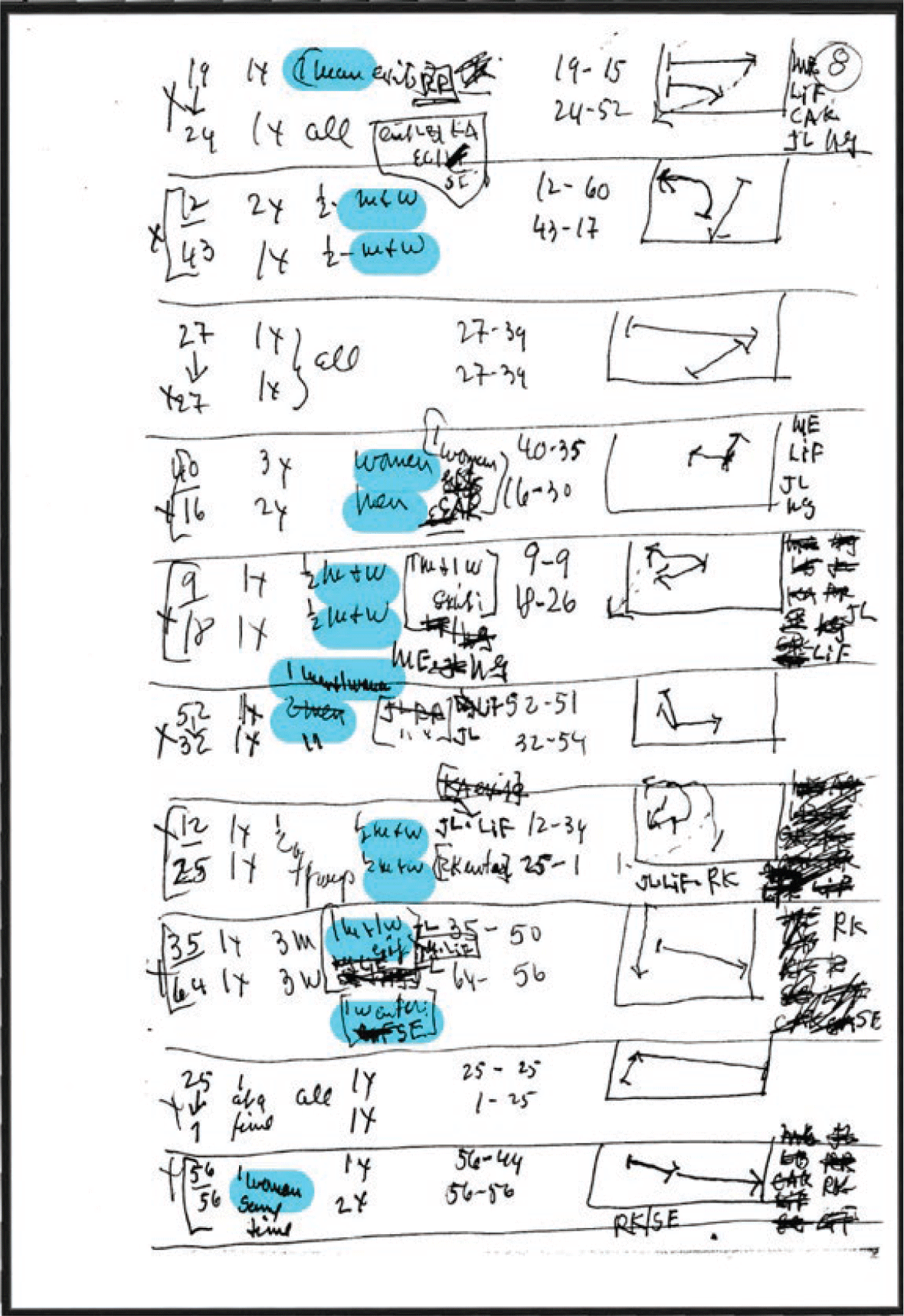

Not only are mixed-gender pairings the norm throughout Cunningham’s work, but gender binarism considered by itself plays a major organizational role in his choreography, along with received understandings that conflate sex with gender. As evidence one need look no further than the markings of “M” and “W,” “men” and “women,” and “male” and “female” throughout the preparatory notes he made for so many of his dances, as in his notes for Fielding Sixes (1981; see fig. 6). Though he largely distributed the same movement phrases across gender-binary boundaries, the classification of gender nevertheless permeated his stage.

Figure 6. Markings of “M” and “W” (highlight added) throughout Cunningham’s preparatory notes. Page from Merce Cunningham’s choreographic notes from Fielding Sixes (1980). (Courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library)

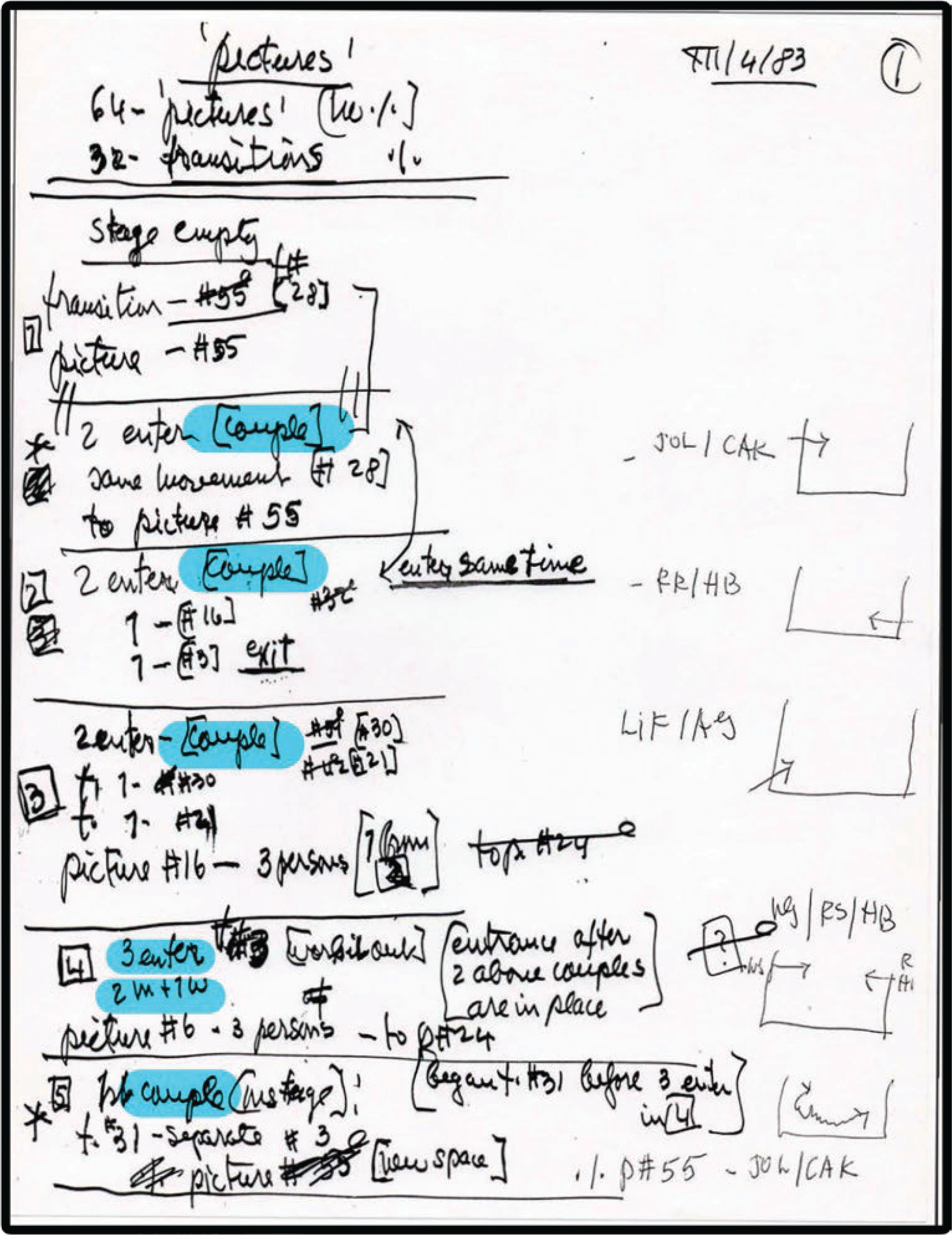

Cunningham’s preparatory notes also make clear his working definition of “couple” as necessarily mixed-gender, as seen in his notes for Pictures (1984) in which initials indicating particular dancers correspond to each mention of “couple” on the left, those dancers always paired “M” with “W” (see fig. 7).

Figure 7. Page from Merce Cunningham’s choreographic notes (highlight added) from Pictures (1984). (Courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library)

Jill Johnston, in her Jasper Johns: Privileged Information (1996), touched briefly, and stingingly, on the issue of mixed-gender duets in Cunningham’s work when she veered from a discussion of Johns’s attempted nullification of personal preference:

In another arena, Cunningham would accept the conventions of heterosexual partnering so central to dance history, forms that he inflicted on his medium as a preference. He would override his contract with chance operations, through which supposedly every manner of movement would find its outlet, and no importance would attach to one kind of movement over another. In partnering, with women cast in traditionally weak and dependent relations to the men (for example, by habitual lifts and supports), Cunningham made a significant exception. Preference in this case was perhaps deemed a social necessity, if not an obeisance to “nature,” as prescribed as the way the knees bend. It certainly suggested Cunningham’s interest in artistic survival over the long haul. (1996:136)

So Johnston too, like Brown and Vaughan, saw the prevalence of mixed-gender pairings as Cunningham abandoning his principles.

While outside the central arguments of this essay, it’s worth noting the sexism existing alongside the heterosexism in Cunningham’s mixed-gender duets. While much of his choreographic project can be seen as antisexist, especially his policy of using chance operations to distribute movement material to the dancers of his company in a gender-blind manner, his female-male duets can be seen, as Johnston asserted, to cast women “in traditionally weak and dependent relations to the men.” Indeed, I must note that, during the years I danced with Cunningham, he often referred to the male dancers as “men” and the female dancers as “girls” during rehearsals, as in “first the men and then the girls.” Though many of us bridled at this seemingly unconscious slip of the tongue, to my knowledge Cunningham was never called out on it.

Cunningham was, however, sometimes critiqued on a possible heterosexism lurking within his reliance on mixed-gender pairings. Among his characteristic responses was to claim that his seeming attraction to this convention was, indeed, to use Johnston’s phrase, “an obeisance to nature.” He explained:

CUNNINGHAM: [U]sually the male is stronger, just physically stronger, so there are things you could do that you just couldn’t do. If you have two men dancing together there’s a kind of parallel strength, almost equal, it could be. With women, it’s different. Although the women are much stronger now than they used to be [laughs]. (2007:34)

Here, he insists the possibilities for partnering are so greatly augmented by mixed-gender pairings that they are simply more efficacious for him choreographically, irresistible out of circumstance rather than out of preference for the normative.

Cunningham might be forgiven this claim, since he was unskilled in the kind of partnering that makes it quite possible for a much smaller person to support, lift, and maneuver a much larger partner, as in contact improvisation, for example. Perhaps his awareness of the increasing employment of such partnering contributed to his concession that “the women are much stronger now.” He still maintained, however, that in choosing mixed-gender pairings he was bowing, if not necessarily to “nature,” then at least to the materials at hand: the perceived comparative strengths of the particular men and women he selected for his company.

Yet Cunningham’s exclusion of same-gender possibilities regarding physical contact in his duets extends to completely nonsupportive physical contact, such as holding hands or linking arms, as well. In Cunningham’s choreography, there are some instances in which groups of three or more dancers might have nonsupportive physical contact such that two men hold hands for a brief period (see fig. 8), and a great many instances in which a woman and a man hold hands while dancing an extended duet. I count at least 10 dances during my years in the company in which I held hands with a woman during a duet sequence, but no instances of two dancers of the same gender holding hands for a duet. This would seem to shoot holes through Cunningham’s argument that he is “bowing to nature” in the prevalence of mixed-gender duets in his work, since no greater choreographic possibilities are provided by mixed-gender partners holding hands, as opposed to same-gender partners doing so.

Figure 8. An instance of two men holding hands within a group formation. From left: Catherine Kerr, Joseph Lennon, Alan Good, Robert Swinston, Helen Barrow, and Neil Greenberg in Pictures (1984). (Photo by Art Becofsky, 1984; courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library, with permission from the photographer)

In our interview Cunningham also maintained his customary stance regarding possible heterosexual or even romantic readings of his dance duets:

CUNNINGHAM: No, no. There are two people…what it is, there are two people dancing together. You watch it, and you think it’s about this… They [audience members] come up with some idea, whatever it is, and expect you to say it. I always say, “Well, that’s ok if that’s what you see.” […] I just see it as two people moving together. (2007:34)

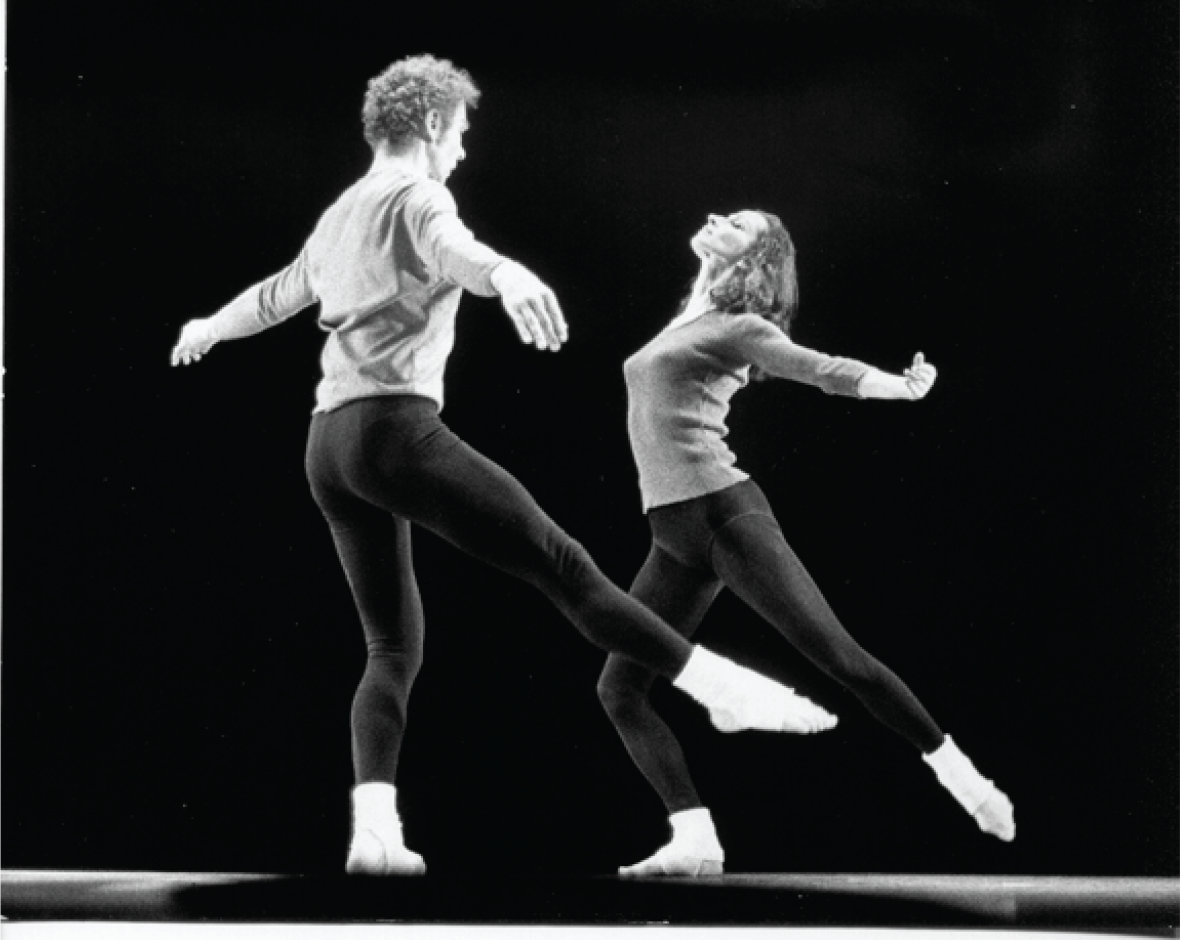

Brown, however, repeatedly suggested throughout her book that many of the duets she performed with Cunningham had erotic implications, citing their “man-woman duets” in Amores (1949) and Septet (1953) as “erotic and tranquil” (2007a:82); in Suite for Five (1956) as possessing resonances of “sexual or romantic attachment” (149; see fig. 9); and in Place (1966) as “mostly tender yet passionate” (476). Brown also provided a telling description of her duet with Cunningham from the 1965 How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run, and her experience of teaching the duet to later dancers:

In one brief section, I circled Merce doing a series of quick low developpé—front, side, and back—until I faced him. Then the phrase slowed down incrementally as he joined me doing the same movements, except that when I extended my leg back in low arabesque, arching my back away from him, he extended his to fourth front, curving his torso toward me, and vice versa. All the while, our opposing arms curved front, side, back, as if to stroke and embrace our partner. Sensuality, tenderness—that’s what I felt when Merce and I performed it. But when coaching the technically superb 2002 company in How to…, I couldn’t understand why the movement itself did not tell the couples this. The moment looked wooden, unfelt, mechanical. So, contrary to protocol, i.e., refusing to talk about such things, I risked spelling out what I believed was taking place: “Whatever your attitude in real life toward the person who is your dancing partner, at this moment you are in love with him or her, and if this doesn’t ‘read,’ then this section simply doesn’t work.” Merce chuckled. Nodding in agreement, he let me get away with it. (2007a:461)

Figure 9. Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham in Suite for Five (1956). (Photo by Marvin Silver, 1968; courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library)

Brown saw clearly romantic overtones within this Cunningham duet, complete with strokes and embraces. Importantly, she suggested here that Cunningham, by “nodding in agreement,” was giving his assent to her reading, at least concerning this one mixed-gender duet. Besides furthering her fundamental project of countering the “propaganda” that Cunningham’s work has no meaning, she specifies that a concealed meaning within this duet is, indeed, a representation of a love relationship—a love that, I maintain, can only be seen as heterosexual.

In Merce Cunningham: After the Arbitrary Carrie Noland argues “Cunningham’s dances contain and represent relations (even if built on arbitrary encounters)” (2020:9), extending “relations” to include not only temporal and spatial correspondences but also the interpersonal and theatrical as well. Further, for Noland, “the very nature of the duet as a form is to suggest an intimate relationship, one that almost inevitably bears the seed of a larger drama” (123). Though I might argue with the inevitable implication of the duets as part of “a larger drama,” I concur, as I think Brown surely would have done, that Cunningham’s work is replete with the performance of social relations, with the duet form continually appearing as a primary social organization on his stage.

Noland also provides an intriguing and valid argument concerning the “Dialogue” form that Cage and Cunningham developed and performed together over two decades:

Against the critical consensus (and accusation) that Cunningham never choreographed a same-sex duet—or, more precisely, a duet for two men […] I will maintain that in fact the Dialogue was that duet. The Dialogue was a queer duet, one that implicitly struggles with its own constraints and the constraints of the duet relation in general. (176)

While I applaud the notion of Cage and Cunningham’s specialized Dialogue form as a queer duet, I continue to ask why, within the vast majority of Cunningham’s company works, did he not challenge the obvious “constraint of the duet relation” that defined it as necessarily mixed-gender?

However one slices it, and Cunningham’s own denials notwithstanding, the mixed-gender duets of Cunningham’s dances represent a significant transgression of his own principles, chief among them the democratic distribution of materials and choreographic possibilities. Cunningham’s perpetuation of the mixed-gender duet shored up the closet by allowing this heterosexist choreographic convention to go unchallenged in his work. Why did he allow this?

Perhaps Cunningham’s perpetuation, and verbal defense, of mixed-gender pairings can be read simply as evidence of unexamined attitudes toward gender and sexuality, a perhaps unconscious maintenance and defense of cultural norms. As Vaughan pointed out in our interview, “Merce, in so many ways, is a product of his own time, and not our time” (2007:12).

Yet I think Johnston was also on target when she wrote that Cunningham’s indulgence in his preference for mixed-gender partnering suggests his ambition for long-term artistic survival.

It’s instructive to consider the duets Cunningham made for himself and Carolyn Brown in this light. Cunningham’s work began to take off when he began his partnership with Brown in 1953, both in terms of its reception by critics and audiences and of the consolidation of his artistic vision. Previously Cunningham had presented mostly solo concerts, and his best notices came from New York Herald Tribune critic Edwin Denby, who praised his “variations of solo lyric dancing,” but considered these “not sharp enough themselves to attract the intelligent audience he is equipped to interest,” though he possessed “a rare good sense in what a man dancing alone on the stage may with some dignity be seen to be occupied in doing” (1986:279). Here, Denby praises Cunningham for his “rare good sense” of appropriately gendered behavior,Footnote 8 but still considers his solo work somehow lacking.

Figure 10. “Sensuality, tenderness—that’s what I felt when Merce and I performed it.” Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham in How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run (1965). (Photo by Martha Keller, 1966; courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library)

After Cunningham began dancing with Brown he often presented concerts with just the two of them performing solos and duets. Note the contrast between Denby’s review of Cunningham’s solo concert and this glowing review by Horst Koegler of a duet performance in Berlin:

Watching the dance-duo Merce Cunningham and Carolyn Brown, you repeatedly ask yourself how far ahead of their time they had already moved, how many new possibilities in theatre dance they might reveal that would be brought to fruition only by future generations.

The physical control of the dancers is tremendous; if finally one admires Carolyn Brown even more than Cunningham himself, it is because in the accomplishment of his choreographic structures she shows once again a classical awareness, that he himself has not yet achieved with such absolute sovereignty. If modern dance is to look in a few decades the way it was shown to us in Berlin by Carolyn Brown, we may look forward to some extraordinary times. What was completely unexpected in these dances was precisely that they were of an incredible beauty. (in Brown Reference Brown2007:306)

Sadly, I never saw Brown dance in live performance, but it’s easy to see from recordings some of the qualities that made her so well suited as a Cunningham dancer. I discern a focused and attentive intelligence that matched Cunningham’s own. She also brought a laser-like calibration of line and form, rhythmic precision, and a voracious appetite for moving through space—all emblematic attributes of Cunningham’s movement technique and style that Brown’s dancing modeled for future dancers of Cunningham’s work.

But it’s also worth noting that Brown was a very beautiful woman, as understood and defined by the standards of the time and place, who sometimes moonlighted as a high fashion model. Critics often mentioned her physical beauty: “the gazelle-like Carolyn Brown”; “one of the world’s loveliest dancers”; “as remotely and passionately beautiful as Artemis” (in Brown 2007a:404). Surely it was a plus for Cunningham to be seen dancing with such a classically beautiful woman.

I’m not suggesting that Cunningham’s critical or audience reception suddenly skyrocketed after he began dancing with Brown. The aesthetic toward which he was moving was quite new for dance audiences, and as such did not meet with sudden approval. Quite the contrary. I am proposing that the duets he created for Brown and himself made it easier for contemporary viewers by providing a conventional—and heterosexual—frame for his very unconventional ideas. Not only did Cunningham leave the convention of the mixed-gender duet unchallenged, but he also opportunistically benefited from performing duets with a glamorous woman, a practice he continued with other women in the context of a larger company.

Figure 11. Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham in How to Pass, Kick, Fall and Run (1965). Brown saw romantic overtones in the duet. (Photo by Martha Keller, 1966; courtesy of the Merce Cunningham Trust and the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library)

Indeed, a revealing example of Cunningham’s deference to cultural norms of beauty can be gleaned from Brown’s account of a dancer leaving the company in 1955: “Like all the women in the company, she hoped to be cast in romantic duets with Merce, but he didn’t envision her that way,” suggesting as one reason the woman’s “very difficult body, tending to overweight” (2007a:117). Here, Brown could be describing a completely conventional ballet or modern dance company in the awarding of normative, heterosexually romantic roles only to women with contemporaneously idealized body types.

When I asked Cunningham if, perhaps, he didn’t at first challenge the convention of female-male duets because he wanted to make it easier for audiences, he replied, “Well, we performed so rarely, that…and even then, it was so curious…” (2007:36), implying that he did feel a need to cushion the blow of his very new ideas, and that the duet form may have served this purpose. Cunningham’s duets with Brown, and soon other women as well, allowed him to present himself as a mature, strong, confident, capable (male) person, by virtue of his gift of support and assistance to his (female) partner.

My reading mirrors Gay Morris’s take on another gay choreographer, Bill T. Jones, in her argument that in his early work Jones combatted “symbolic emasculation” by “a raiding of heterosexual power to counter the emasculating effects of racial and gender stereotypes” (2001:261). Cunningham’s reliance on the mixed-gender duet is his most overt “raiding” of heterosexual and/or masculine power in his work, but there are other candidates. The relatively unemotional performance demeanor of so many of Cunningham’s dancers might be seen as culturally butch in relation to the emotive acting required in the works of his female modern dance predecessors, a move away from “the ‘woman’s’ work of investigating psychological interiority” (Foster Reference Foster and Jane2001:150).

Foster noted Cunningham’s emphasis on the practical material elements of dance composition and his use of mathematical procedures as manifesting a “masculine” rationality and objectivity (2001:177). All these attributes claimed power that would otherwise be denied him as an artist working in the “woman’s medium” of modern dance.

Personally, and in contrast to Brown’s experience, I never felt called on to enact a romantic relationship with my (female) partner while performing any of the duets I danced in the Cunningham repertoire. It is my experience that the two partners of a Cunningham duet need in no way pretend they are lovers, but rather can dance with each other as themselves, as two human beings (I clearly took Cunningham’s directives to heart). An LGBTQ dancer need not cloak their sexual identity by playing it straight, and a heterosexual dancer paired with a gay or lesbian dancer need not function as a beard.

Yet, still, the exclusion of same-gender duets in all but Cunningham’s late career works is striking. If the organization of dancers onstage is in some way “a map or model of social relations” (Copeland Reference Copeland2004:270), Cunningham is then very apt in presenting couples as a major social organization, but heterosexist in presenting only mixed-gender pairings. Sadly (to me), Cunningham did “override his contract with chance operations” by categorically disregarding same gender couples.

And so it is here, in his favoring mixed-(cis)gender duets, where a closet within Cunningham’s choreography can be found.

Concluding Politics

Though I have asserted the existence of an overriding, anti-interpretive ethos running through statements that Cunningham and Cage have made about their work, it’s important to note exceptions to this general rule. In the documentary introduction to the 1987 Cunningham dance film, Points in Space, Cage comments on the instigation of the Cage/Cunningham mode of collaboration:

The modern dancers wanted the dance to be finished first and then the music to be written to fit it. Formerly, the ballet had taken a piece of music which was already finished and they made the dance fit the music. Neither situation struck me as being politically good. (in Caplan and Cunningham Reference Caplan and Cunningham1987:55:35)

Cage gives here an unabashedly political reason behind a fundamental tenet of his artistic partnership with Cunningham, the independent coexistence of music and dance. Cunningham, too, has viewed this principle through a lens of power relations: “It’s really a political move that says things are equal” (in Copeland Reference Copeland2004:271). He elaborates on this point in a 1980 interview:

[I]n a sense we are dealing with a different idea about how people can exist together. How you can get along in life, so to speak, and do what you need to do, and at the same time not kick somebody else down in order to do it. […] We do represent a kind of individual behavior in relation to yourself doing what you do and allowing the other person to do whatever he does. […I]t does imply good faith between people. (in Cunningham and Lesschaeve Reference Cunningham and Lesschaeve1991:163–64)

In these and other statements Cage and Cunningham have made it becomes clear that though one plank of their party platform asserts that their concerns are exclusively aesthetic, another plank encourages politically inflected readings that make personal freedom a paramount value.

The promotion of personal freedoms can be found in Cunningham’s active resistance to habits and cultural norms, in part through his use of chance operations; in his interrogation of “the natural” in movement and choreographic practices; and in the import he ascribes to dancers performing as themselves as fully as possible. Unfortunately these positive political values operate alongside the near-absence of same-gender duets throughout his work, a fault line that reveals the cultural quake of homophobia. Cunningham’s “closet” throws into relief the difficulty he faced as a gay man working in dance in America in the 1940s and 1950s. Cunningham’s very reticence, much noted by Brown in her memoir, served him well in the intolerant social climate of 1950s America, perhaps enabling the success of his choreographic project. Jane Desmond, introducing her edited book, Dancing Desires: Choreographing Sexualities on and off the Stage (2001), writes: “Homophobia, the dark background of dance history, is actually the constitutive ground of a great deal of what we know as the ‘canon’ of dance history” (4). Cunningham’s work, certainly to be included in any “canon” of Western dance history, stands as both a challenge to homophobia and as compromised by it.