Esta rabia es vuestra, es tuya, te la devuelvo.

(This rage is yours; I return it to you.)

—Silvia Albert Sopale (Reference Albert Sopale2021:355)

In the shadowy ambiance of the “Museum of Shame,” Oda Mae Brown (Silvia Albert Sopale) explains to the audience that it is the year 3054, and they are watching a film that gazes back at the past. The film is in fact the play we came to watch, Blackface y otras vergüenzas. Oda Mae is a medium, just like her namesake played by Whoopi Goldberg in the 1990 film Ghost, who hints that she will be conjuring specters from a racial history. This future gaze looks back at our present—a present mired in silence on the discourse of racism in a country that has historically ignored its existence. As the play within a play unfolds, the audience finds itself in a transformative moment, as the Afro-Spanish playwright Silvia Albert Sopale challenges us to engage in collective introspection and beckons us toward a future that demands acknowledgment, dialog, and action toward racial justice.

Sopale’s Blackface y otras vergüenzas (Blackface and Other Embarrassments; 2021) and La Moreneta (The Black Madonna; 2019) interrogate the legacy of Black bodies as spectacles within European consciousness, dismantling the performative nature of racial constructs.Footnote 1 These plays challenge not only the historical amnesia surrounding the Black influence in Spain but also the modern-day implications of such portrayals. Through this artistic practice, Sopale’s theatre reveals a continuous thread from past to present, illustrating how Spain’s Black heritage has been systematically obscured and how contemporary expressions like blackface contribute to this invisibility. Her approach deconstructs the notion that the Black experience in Spain is a new phenomenon of the 21st century, highlighting instead a centuries-long narrative that is integral to understanding the nation’s complex identity.

By depicting racialized characters as integral to the national fabric, these plays present otherness as part of the lingering historical trauma inflicted by institutionally sanctioned anti-Blackness. In Sopale’s plays, the deaths of Blacks reflect the experience of living amid the ghosts of those lost to migration, invisibilization, and racialized dehumanization, which persist in new forms.

In contrast to the violent erasure of necropolitical theatre, the self-determining impulse within the theatrical works of Afro-Hispanic playwrights resonates with José Esteban Muñoz’s concept of disidentification.Footnote 2 As marginalized artists reshape their identity by subverting dominant paradigms, they enact a process that counters the stereotypical representations imposed upon them. They reject hegemonic narratives in favor of self-authored expressions of identity. By highlighting the intersections of Black and Hispanic identities from a Black feminist perspective, Sopale shifts from imposed tropes to a radical self-definition, echoing Muñoz. These plays demonstrate how disidentificatory performances can be used to reclaim identity and unleash new, liberatory understandings of marginalized subjectivities, challenging audiences to rethink their own perspectives on selfhood. They not only question audiences but also push for social change by bringing people together as performers to explore racial hierarchies onstage, especially as these hierarchies relate to the audience’s own perceptions.

Blackface as Disidentification

As a founding member of the pioneering Black feminist theatre collective No Somos Whoopi Goldberg, Silvia Sopale, alongside fellow artists Kelly Lua and Maisa Sally-Anna Perk, has been at the forefront of advocating for increased visibility of Black women and Black culture on the Spanish stage (Garcia Espelta Reference Garcia Espelta2019). Driven by a mission to highlight the overlooked and underrecognized contributions of Black women throughout history across various fields, the group’s inaugural production in 2016, Palabra de Negra, was a poetry performance that showcased the work of female Afro-descendant authors. This pioneering recital announced the arrival of No Somos Whoopi Goldberg as a formidable creative force dedicated to amplifying marginalized voices through an inventive, politically engaged theatre. Their subsequent productions continued to excavate and draw attention to the neglected narratives of remarkable Black female figures, catalyzing crucial conversations about race, gender, identity, and cultural belonging. Sopale’s artistic activism within the collective solidified her reputation as a leader in the struggle for symbolic justice and self-determination in Afro-Spanish communities.

Sopale is also the founder of No Es País Para Negras, a theatre company with which she has written and produced two of her notable monologs, Blackface y otras vergüenzas and La Moreneta. In these, she examines the quotidian experiences of women of African descent in contemporary Spain. Each features an interactive segment that allows the author to engage with the audience, fostering a discussion about the play’s content and providing them with a broader understanding of the topic beyond what they see in the monolog. They subversively examine racial hierarchies by strategically structuring the audience participation: Black women are invited to participate in the dialog first, followed by Black men, white women, and finally, white men (Guerrero Reference Guerrero2020). This order prioritizes marginalized voices, amplifying their agency while delaying and restricting contributions from those who usually dominate. Having Black female perspectives sets the tone for critical conversations about race. Layered participation reveals the asymmetry between racial privilege and power in public discourse. White men must wait and listen before speaking and counteract habitual centering. This metadramatic technique exposes the ingrained protocols of privilege that frequently erase diverse voices in favor of white male dominance in public debates about race.

The play’s structure enacts Muñoz’s conceptualization of disidentification as a generative hermeneutic process. He describes disidentification as a reciprocal movement “shuffling back and forth between [the] reception and production” of identity constructs (1999:25). Similarly, Sopale receives and subverts normalized racial hierarchies by inverting and staging them within theatrical spaces. Audience participation brings into view and problematizes the dominant paradigms that erase diverse voices. The reshuffling of discursive authority provides marginalized subjects with a means of countering internalized protocols of privilege. Just as Muñoz frames disidentification as an oscillating hermeneutic, Sopale dynamically critiques institutionalized racism by exposing and productively reshaping the patterns of racism within the theatre.

Both Blackface y otras vergüenzas and La Moreneta speak to the broader elision of racial discourse that Nicholas Jones locates in the dominant narratives of Spanish national identity. Jones argues that conceptions of cultural hybridity in Spain have centered on the cultural mingling of religious groups, especially during the medieval period called convivencia, while obscuring the racial dimensions of identity formation (2019:66). In other words, the predominant framework of cultural hybridity is based on religious syncretism, eliding discussions on Blackness and critical race perspectives. This prevailing framework specifically overlooks the presence and contributions of sub-Saharan African communities. Just as Sopale unveils and subverts the erasure of Black voices, her metadramatic techniques confront the marginalization of racial perspectives that have resulted from a focus on cultural syncretism and fluidity. Her disidentificatory reshaping of discursive power relations enacts a broader questioning of the national mythologies that have suppressed critical engagement with race. The plays challenge both theatrical and national stages, where institutional paradigms have relegated nonwhite subjectivity to the margins.

Jones’s Staging Habla de Negros: Radical Performances of the African Diaspora in Early Modern Spain examines blackface as a lens for understanding African cultural influences in Golden Age theatre. Jones’s analysis emphasizes the significance of sub-Saharan African folk traditions, linguistic nuances, religious practices, and musical forms (2019:40). Similarly, Sopale focuses on blackface as a tactic to challenge the prevailing anti-Black biases and stereotypes. She achieves this by highlighting characters persistently cast to contribute to the objectification of Black existence, both in their muted roles in white narratives asserting Black inferiority and in the continued mockery of Black physicality. When Sopale employs blackface in her theatre productions, she does so by studying its ambivalent dual role. On one level, she strategically uses blackface to assess broader resistance strategies. The play reminds us of how blackface has historically provided space for stereotypes, subversions, containment, and creativity. By metatheatrically staging an exaggerated blackface, she introduces a Black identity, which highlights the complexities of the practice. Through hyperbolic distortion, Blackface y otras vergüenzas unpacks the layered impact of theatrical techniques. In her work, blackface is simultaneously reinscribed, ruptured, encoded, and decoded. Therefore, by wielding this double-edged sword onstage, her play examines how institutions impress and contest racial paradigms over time. She harnesses the jarring visibility of blackface to reveal the nuances of representation, resistance, and self-determination.

Jones further unpacks the complexities of how blackface performances engage with Black vernacular culture by analyzing the phenomenon of habla de negros—the theatrical representation of Black Spanish speakers through stereotyped dialect and speech patterns in Spanish Golden Age theatre. He shows how playwrights deployed caricaturized renditions of Black speech and dialects. While these works were unquestionably racist in their intent, Jones argues that the aesthetic preservation of African diasporic linguistic forms within blackface represents an ambivalent mixture of mockery and cultural exchange (2019:67). The staged imitation of Black vocal patterns, rhythms, and lexicons both derides and preserves traces of actual Black voices. Thus, early modern Spanish dramas imitating Black vernaculars reinscribed racial hierarchies while simultaneously transmitting the components of the cultures they denigrated. For Jones, excavating these complexities enables a richer understanding of blackface’s oppressive legacy and its inadvertent registers of Black resistance:

White appropriations of Blackness […] demonstrate the slippery polymorphousness of racist depictions of blacks in early modern Castilian literature and cultural productions. And because race and voice are elusive and culturally charged and contextual, it is the polymorphous, slippery quality of Black Spanish that I contend will illuminate textual articulations of agency, resistance, and subversiveness in black African cultural expression and modes of speech. (2019:20)

Jones’s assertions about the generative instabilities of white appropriations of Blackness lay the groundwork for further analysis of the paradoxical function of blackface. Blackface y otras vergüenzas utilizes contradictory impulses toward reinforcing and subverting cited norms. The play’s blackface exaggerations verge on hyperbole, destabilizing traditional mimetic representations of Blackness by making them increasingly opaque and ambiguous, aligning with disidentification. By distorting blackface conventions to excessive proportions, Sopale’s performances rupture existing racial paradigms. The hyperbolic opacity of these racial representations allows counterhegemonic possibilities to emerge. No longer constrained to reinforcing stereotyped Blackness, the fluid ambiguity provoked by the play’s racial masquerades opens up the potential to assert unexpected voices. In this vein, the play’s risky excesses provide opportunities amid ambiguity for counternarratives of Afro-Spanish exclusion. Since the play’s power to implicitly mimic and destabilize epistemic violence is embedded in its own citational structure, it performatively intimates vulnerabilities and porousness within hegemonic racial constructs, even as it depends on those constructs. Furthermore, the generative instabilities produced through repetition with difference illuminate blackface’s paradoxical workings, suspended between reinscribing and contesting dominant racial paradigms. Building on Jones’s arguments regarding blackface’s slippery permutations, I unpack the rhetorical complexity of its racial citations to reveal unstable moments of critical possibility.

Blackface y otras vergüenzas

Revisiting Black History

Using a minimalist set design, Sopale stages a one-act monolog that explores racism through a series of haunted encounters. The protagonist’s interactions with these specters are mediated by Oda Mae Brown, with the unlit, blacked-out stage backdrop intensifying the colors and notions of space. Objects, such as Oda Mae’s table or the picture of a white man performing blackface (see fig. 3), as well as the characters that Oda Mae brings to the stage, are illuminated by colored lighting against the dark backdrop, creating dynamism between the forms and bodies and highlighting the spectral atmosphere of the work. As Dixa Ramírez argues in Colonial Phantoms in the Caribbean context, spectrality helps liberate an audience from the two-dimensional caricatures of antiblackness and collective amnesia around race (2018:33). These historical figures unearth the multifaceted ways in which racialization has lurked beneath the façade of dominant colonial narratives that frame Blackness in Spain as singular and static.

The play’s opening introduces Oda Mae Brown, portrayed by Sopale, who directly addresses the audience to relay the latter’s apparent absence due to budgetary constraints. While the performance draws on the character of Oda Mae Brown from Ghost, Sopale adapts this role to mediate between absent performers and present audiences. The appropriation of this recognizable figure from mainstream white cinema introduces the theme of cultural extraction and exploitation, which permeates the monolog as it unfolds. In the original film, Oda Mae Brown serves as a medium for the deceased protagonist to reach his beloved. Sopale’s incarnation as Oda Mae assumes a similar translational role. However, instead of a white romantic lead, she channels the voices of those subjected to racialization and epistemic erasure under Eurocentric cultural dominance. Rather than a conduit for individualistic white interests, this version of the archetypal “magical negro” gives voice to marginalized figures that speak of communities devastated by colonial power, as when Oda Mae channels the spirit of Saartjie (Sarah) Baartman (1789–1815), who recounts her exploitation as a colonial spectacle in Europe, and the spirit of “el negro de Banyoles,” who describes his body’s posthumous desecration and exhibition in a Spanish museum. Where the Hollywood portrayal reduces Black identity to a source of labor and a vehicle for white narratives, Sopale’s subversive adoption of the character exposes and counters the extraction driving such problematic tropes. By imbuing a familiar pop culture reference with an incisive political critique, the opening hints at the play’s broader project of exposing racist undercurrents through strategic disidentification and contesting dominant knowledge constructs and modes of cultural appropriation that obscure marginalized voices.

Just as Jones asserts, academic works have obscured and omitted Blackness with an ironic tone suited for the unknowability of facts. The play’s inquisitive analysis exposes the racial, gendered, class-based, and epistemological forces potentially lying unseen behind ambiguous events in Afro-Spanish history. Essentially, where reductive stereotypes and historical obliviousness prevail, Sopale’s ghosts unveil the diverse and concealed operations of race contained in imperialist paradigms.

Sopale’s metatheatrical techniques underscore the constructed nature of representation, epitomized by Oda Mae Brown’s repeated ruptures of the theatrical illusion through direct address, drawing attention to her performativity and role-playing. This metadramatic self-referentiality aligns with Oda Mae’s announcement to the public that they will witness an Afrofuturist short film set in 3054, portraying a matriarchal society where two Black women observe museum installations of racist historical episodes (Albert Sopale Reference Albert Sopale2021:360). The audience sees in the supposed historical installation familiar scenes from present-day society. This speculative framing highlights the discursive fabrication of racialized representations. Similarly, Sopale’s rapid shifts between characters—from Oda Mae Brown to the characters Oda Mae channels—breaks with realistic theatrical conventions, foregrounding the mediating lens of the narrative. Blackface emerges not as an isolated historical phenomenon but as an evolving representational strategy intricately implicated in racial hegemony.

Oda Mae is a conduit for processing ghosts, providing distinct perspectives on racial hegemony and violence. Rather than employing straightforward denunciations, Sopale frequently turns to humor, irony, and satire to achieve the effect of alienation, deliberately discomfiting audiences, mainly white viewers, uncertain of whether such moments permit laughter. These techniques, including strategic distancing, construct a counterpublic sphere in which racially dominant assumptions remain unsettled. The spectral scenes reveal the artificiality that underlies the naturalized fiction of race. By eschewing simplistic didacticism in favor of estrangement, the monolog foregrounds the complexities of race, compelling deeper reflection by thwarting the facile consumption or digestion of the issues explored. The result is a generative unsettling that reveals myriad interconnections between historical racial trauma and contemporary manifestations of prejudice. The resulting counterpublic performance strategically disorients the audience to encourage critical consideration of normalized attitudes and practices related to race.

Blackface y otras vergüenzas draws from these tensions in a scene featuring the first ghost, La Negra Tomasa, dressed as a maid and carrying a jar of white powder in each hand, like those participating in Santa Cruz de La Palma’s Indianos carnival celebrations.Footnote 3 Like all other characters in the play, Sopale performs La Negra Tomasa to interrogate other racialized archetypes embedded in Hispanic cultural imaginaries. This iconic figure, who is featured in songs and folklore, epitomizes the denigrating stereotypes of Black womanhood that persist in Hispanic cultural representations, particularly in contexts celebrating colonial histories and mestizaje. Her exaggerated physicality and diminished intellect construct a hypersexualized and compliant subjectivity that naturalizes colonialist tropes, as Elizabeth Farfán-Santos notes: “She is a symbol of a deeply embedded racial discrimination and denigration of the Black body and identity that makes up the foundation of the mestizo narrative throughout Latin America” (2016:ix). The photographic backdrop featuring the Tomasa character in her signature costume—with the distinctive turban and a parrot perched on the shoulder—places this demeaning archetype against the backdrop of Spanish colonial history.

The picture, hung on the black scrim, features a recurring figure from the carnival, Víctor Lorenzo Díaz Molina—a fixture at the event for over 45 years, exemplifying the normalized discursive violence behind blackface—and brings to the stage an event that glorifies the legacy of white Creole elites enriched in the transatlantic slave economy. Carnival features people dressed as the Indianos who returned to the Canary Islands from America during colonial times, who ostentatiously flaunt the wealth extracted from colonial holdings through displays of jewelry and white linen, emblems of their racial capital and domination. By situating Molina as Tomasa within this milieu, the mise-en-scène shows this characterization as both the product and perpetuator of an enduring colonialist ethos predicated on white supremacy and anti-Black subjugation. Molina noted that he began impersonating figures like Tomasa and Kunta Kinte when such racialized performances were commonplace (Pérez Duque Reference Duque2012). Sopale’s strategic deployment of Tomasa’s iconography in the play unmasks the colonialist archetypes that sustain racial hierarchies across temporal and geographic boundaries.

Tomasa plays the role of Molina’s maid—or rather, Sopale as Oda Mae channels Tomasa who plays the role of the maid—and is involved in coffee preparation. Addressing the audience, she states:

TOMASA/THE MAID: Hello, how are you? It’s good that you came! And the family, are they well? Say hello to your wife… Hello, is this the first time you come? Would you like some coffee? With sugar? Girl, look, sugar is like a drug, and it can kill you; well, there you go… Every year, more people come to enjoy our Indian Carnival. And there is no party like this in the whole world. There is no better time to welcome you than the big day in Santa Cruz de La Palma. They’re going to love the party; they’re going to feel at home, we’re going to have the time of our lives together, and I’m not going to let them out of my sight for a minute. And it’s been many years, it seems like you get used to it, but something is always missing in your heart. I would have preferred not to work today, but that’s life; today is a crucial day for the master; he needs me. (2021:342)Footnote 4

By warmly addressing the audience as if they were esteemed visitors to the annual carnival, Tomasa/the Maid seems compelled to serve, and the audience becomes embedded in the racial power dynamics critiqued by Tomasa’s characterization. As she defers to them as venerated guests, celebrating without acknowledging those who have been exploited, viewers are confronted with their own privilege and positionality, perpetuating the endemic inequalities and echoing the legacy of subjugation maintained by the festival’s pomp and grandeur. In dramatizing these issues, the play implicates the audience within the neocolonial racial order, hinting that extravagance concealing ongoing oppression relies on public complicity and willful obliviousness.

This dramatic tension escalates as the actress’s disembodied, recorded voice addresses Tomasa, beckoning her closer to the back of the stage to discuss the implications of Molina’s blackface. A voice from the dressing room, identified as Silvia (Sopale’s other character), calls to Tomasa. Their exchange unfolds through dialog between the offstage voice and Tomasa, who initially dismisses Silvia with skepticism (“What kind of actress are you?” [2021:345]) and reluctance to leave her duties (“I’m the one who doesn’t have time, I have to finish the skirt for the master” [345]). This heightens the contrast between Tomasa’s oblivious viewpoint of the behind-the-scenes reality and Silvia’s seemingly urgent need to convey revelations about portraying Tomasa onstage. Silvia clearly aims to break Tomasa’s immersion in the world of the play, but Tomasa resists passage into the realm of artistic construction and the metacommentary occupied by her actress counterpart. Eventually, the voiceover insists, “Consciousness is acquired through a long process, but due to the script’s requirement, you have a consciousness. Ya! You have Afro-awareness!” (346). This moment punctuates Tomasa’s transformation: after Silvia awakens Tomasa’s awareness of how the carnival perpetuates colonial racism, Tomasa confronts Molina’s portrait, whose defensive responses (“It’s not a massive Blackface”; “there’s no racism of any kind here”) exemplify white resistance to acknowledging racist practices (349–350).

Consciousness makes Tomasa realize her position and she becomes reproachful toward her master. The character identified in the script as “INT.” (likely short for “Interlocutor”) defends blackface, citing it as a tradition. Tomasa counters Molina’s defense of the carnival by pointing out how specific Spanish festivals perpetuate racism: “You have quite a few. October 12th, The Taking of Granada, the Moors and Christians festivals in Andalusia, Aragon, Valencia Community, the Three Kings parade in Alcoy…” (349). In response, INT. (the internalized voice of the portrait) defends blackface as a practice that expresses admiration: “For me, playing Black Tomasa is a source of pride, truly, I do it with all respect, it’s my homage to people of color” (348). Tomasa challenges this by stating that such actions can be demeaning and reduce an entire culture or race to mere costumes or stereotypes.

This metatheatrical technique reveals the normative dialogs of white fragility and evasion that emerge when white people are confronted by legacies of appropriation and racial hegemony. Tomasa explicitly denounces carnival performances as instances of cultural theft, racial objectification, and ignorance of the harmful ramifications of tradition. Likewise, Sopale excavates the discourse on blackface to reveal its roots in racist theatrical practices despite attempts by the INT. to dissociate local customs from history. The monolog underscores comparable tendencies in Spanish theatre that appropriate Blackness through reductive caricaturing. Ultimately, Sopale strategically stages this metadramatic dialog between Tomasa and INT., accentuating the need for sustained critical engagement with traditional customs in light of changing cultural perspectives. Appeals to “tradition” as unchangeable—like INT.’s defense “our traditions are sacred” and insistence that “before we become independent, we’d give up our traditions!” (Albert Sopale Reference Albert Sopale2021:347)—serve to rationalize ingrained forms of prejudice. Instead, Sopale calls on white theatregoers to be self-reflexive, stressing the importance of examining complicity in historical inequities as a vital ongoing process and emphasizing that traditions deemed innocuous or celebratory may encode problematic assumptions that require conscientious evaluation.

Similarly, Muñoz’s disidentification involves actively decoding and reshaping the exclusionary meanings embedded within dominant cultural texts. Disidentification transforms dominant narratives that erase minority identities, thus exposing and hijacking the inner workings of normative representation. Similar to Sopale’s metatheatrical emphasis on evaluating traditions, disidentification repurposes established codes as a tool to empower marginalized subjects:

Disidentification is about recycling and rethinking encoded meaning. Disidentification scrambles and reconstructs the encoded message of a cultural text in a fashion that exposes the message’s universalizing and exclusionary machinations and recruits its workings to account for, include, and empower minority identities and identifications. Thus, disidentification is a step further than cracking open the majority code; it proceeds to use this code as raw material for representing a disempowered politics or positionality rendered unthinkable by the dominant culture. (Muñoz Reference Muñoz1999:31)

Blackface exemplifies a cultural text encoded with the racist “majority code.” Its theatrical conventions contain layered racial connotations that accrued transhistorically, relying on caricatured codes of Blackness that propagate reductive stereotypes that mock people. As an encoded performance, blackface scrambles and projects the dominant gaze’s warped depiction of racialized subjects. However, disidentification allows marginalized artists and activists to expose blackface’s racist machinations from within, resignifying its codes to reveal the operations of oppression. Put differently, although rooted in denigration, blackface’s majoritarian encodings can provide the raw material for minority subjects to dismantle blackface’s racist logic and project representations of racial identity that exceed the limitations of the code.

The work provocatively suggests blackface’s potential for ambivalent deployment, not only proposing Blackness as a constitutive foil for whiteness but also appropriating the reductive stereotypes embedded in blackface to reveal their contrived nature. Blackface denaturalizes realist conventions, and Blackface y otras vergüenzas builds on this mechanism to problematize theatre as an unmediated reality, instead positioning performance as a constructive practice that either obscures or exposes the elaborate racial fiction underpinning Spanish society. The result is a counterdiscourse that defiantly relinquishes claims of authenticity to elucidate the complex discursive processes by which Black life is aesthetically circumscribed and appropriated.

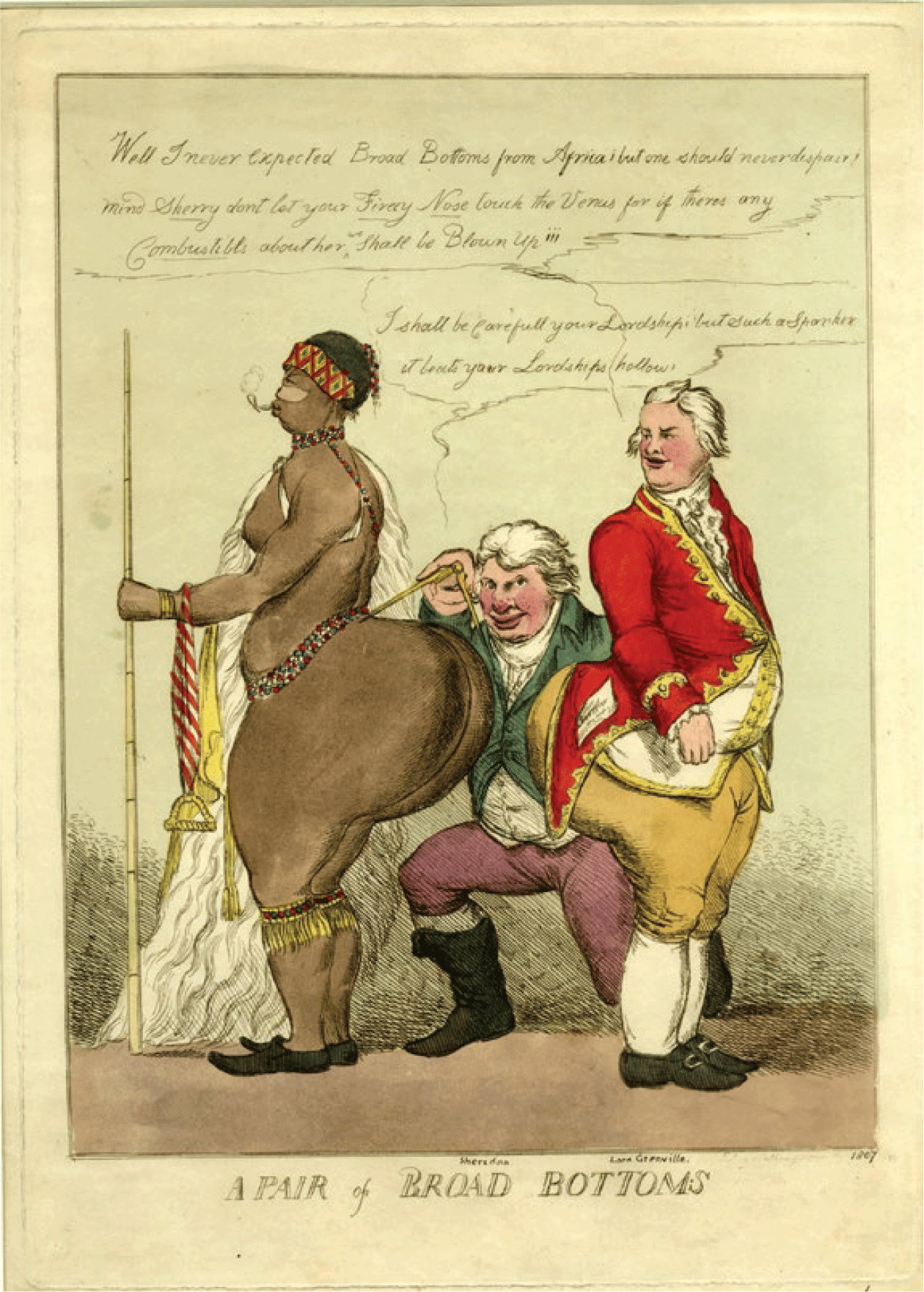

Sarah Baartman is another character who appears onstage. Baartman was put on display in 19th-century Europe under the moniker “Hottentot Venus.” Originally from the Xhosa Kingdom (today’s Cape Provinces of South Africa), her steatopygic physique, unusual in Western Europe, drew attention for its uniqueness, scientific intrigue, and erotic fascination (Parkinson Reference Parkinson2016). In October 1810, Baartman, unable to read or write, signed a deal with English ship surgeons Alexander Dunlop and Hendrik Cesars, a mixed-race businessman she worked for, to participate in exhibitions in Europe.Footnote 5 In this part of the performance, Sopale highlights the exhibitionist function that Baartman’s body fulfills—an emblem of how Black women are spectacularized. However, her ghost also speaks of the fatigue of being the object of the gaze, which is part of the social mechanism that spectacularizes differences. Her portrayal embodies the labor of Black precarity, echoing Tina Campt’s (2019) assertion that modern Black artists enact Black precocity when they reinterpret and reshape the visual records of Black fragility in an innovative and transformative manner.

In the play, the labor of precarity is compounded by the labor of an unending wake—the enduring, unresolved mourning of those lost to the violence of slavery and its legacies. Sopale reveals how Black women’s affective work remains tethered to reconciling persistent historical and communal trauma. The play asks how the emotional and physical demands placed on Black women by white society to comfort and support white others impede their own unfinished grief work. It is a painful irony: while tasked with maintaining white comfort—both psychological and physical, as demonstrated through Tomasa’s domestic labor—Black women carry the added weight of their own unresolved trauma.

Through Tomasa’s dual role—as a maid required to support her employer’s blackface performance while suppressing her own pain from its racism—the play reveals how Black women’s emotional labor is diverted away from healing their own communities’ trauma and instead forced to serve white comfort. By showing Tomasa having to smile and assist with Molina’s carnival costume while internally struggling with its racist implications, Sopale exposes how Black women’s labor and pain are exploited by racial capitalism. Campt states that:

Contemporary artists reckon with this proliferation [of images of Black precarity] by creating modalities of black visuality that challenge us to confront both sides of the dynamic of black affective labor outlined by black feminist critiques of the racialized limits of the categories of work and labor. They engage this dynamic in the domain of the visual in ways that allow us to probe how black folks’ affective labor (both for women and for men) is conscripted by racialized capitalism. (2019:29)

Blackface y otras vergüenzas delves deep into the intricate relationship between work, labor, characters onstage, and the actor representing them. By weaving together multiple manifestations of racist exploitation—from Tomasa’s forced complicity in carnival blackface to Baartman’s story of colonial objectification—the narrative reveals the enduring fatigue experienced by Black communities. Baartman symbolizes both colonial violence and resistance to it. Even after her death, her body was subjected to continued violation and mutilation through dissection, her remains displayed as museum specimens. Her organs became tools for propagating false anatomical distinctions between white and Black people, further perpetuating racial bias and stereotypical caricatures.

Rather than fading over time, these caricatures were repurposed and modernized—from the “Hottentot Venus” figure being reproduced in 19th-century medical texts and world’s fairs, to the “human curiosity” displays of Black women’s bodies in European exhibitions through the 1950s, through to the preservation and public display of Baartman’s remains in Paris’s Musée de l’Homme until 2002 (Qureshi Reference Qureshi2004:233). Amid these multifaceted narratives, the audience is introduced to Sopale speaking as Baartman, providing an intimate perspective of her experiences and sentiments:

I am tired, exhausted from being strong, the strongest, from having to carry this burden on my shoulders. I’m not that strong, I’m not, but I have no other choice, women like me have no other way out. I’m tired of pretending that things don’t matter to me, that they don’t affect me, that I don’t see, that I don’t hear. Tired of having to be prepared all the time for everything. Where can I rest? I feel a heat that takes over my body and, at the same time it burns, it keeps me alive. When will I be able to let out my sadness? I don’t want to swallow the sadness and forget about it. I am afraid of my tears and drowning in my pillow, of drowning in millions of tears, in oceans, in seas, and being forgotten like my brothers and sisters. (2021:354)

By exploring Baartman’s image, Sopale pushes audiences to consider the affective work that women still face when that figure circulates today, and when it is recreated and transformed into mainstream images that perpetuate the objectification and spectacularism of the Black body.

If blackface cannot be extricated from early modern Spanish drama’s racialized performance techniques—the combination of darkened skin, the habla de negros dialect that mocked African accents, exaggerated gestures meant to suggest “primitive” behavior, and stereotypical musical elements that reduced African culture to rhythmic chants—then the subjectivity of the Black female body emerges at the fraught intersection of these codified practices. These figures’ opaque performativity may indicate alternative ways of inhabiting prescribed tropes to counter stereotypical expectations. Their strategic manipulation of the colonial gaze hints at modes of resisting and reshaping reductive projections of the Black female form.

I propose that Sopale’s representation of Sarah Baartman joins the representations of a number of artists delving deep into history, revisiting and reshaping the visual record that has long depicted Blackness as vulnerability. This deliberate reengagement is not merely an exploration of that history but a transformative endeavor. Sopale is not just revisiting images frequently used to frame a medical discourse that contributes to narratives of Black monstrosity but also curating them, bringing to the fore the pain of their historical contexts in which the deaths of uncountable numbers of Black people have been justified or erased. The playwright opts to view these images with fresh, discerning eyes, rather than remain a passive observer. This reframing, reimagining, and reclaiming of the archive speaks to the potential for contemporary Spanish Black theatre to push boundaries and for dramatists and performers to compel themselves and their audiences to delve deeper into, understand, and confront the historical context and enduring legacy of slavery.

Muñoz conceptualizes disidentification as an indexical process that “captures, collects, and brings to play various theories of fragmentation concerning minority identity practices” (1999:31). Sopale follows Muñoz by challenging viewers to grapple with the fragile state of Black life and its historical complexities while illuminating the resilience and strength that have been hallmarks of Black communities across historical contexts. Just as Blackface y otras vergüenzas reframes archival material, disidentification captures and focuses on diverse identity practices in which the dominant structures have splintered. It serves as an indexical guide for marginalized modes of expression and knowledge production.

The “Negro of Banyoles” is another figure Sopale employs to critique the spectacularization of the Black body, by exploring affective labor and unfulfilled mourning. She introduces the story behind an embalmed man from the San ethnic group (precise origin uncertain) who was dissected and taken to Europe in the early 1830s by the French taxidermist brothers Jules and Édouard Verreaux (Westerman 2004). In 1916, this body was acquired by the Darder Museum in Banyoles, becoming a centerpiece until in 1991 the exhibit came under scrutiny. At that point, Alphonse Arcelín, a Spanish doctor of Haitian origin, voiced concerns and ignited discussions in both the global media and Spanish government circles. After much debate, the man’s remains were eventually returned to Botswana in 2000 (Molina Reference Molina2019).Footnote 6

In Blackface y otras vergüenzas, the audience meets the Negro of Banyoles as “Hombre Africano” (African Man), which indicates that the identity of this figure remains unknown. The lack of a name further dehumanizes and universalizes the Black body, which also invisibilizes its pain. In this way, the character shifts scrutiny back to the early modern theatrical milieu when racial meanings were first crafted and solidified. The play probes beyond dominant narratives to uncover the nexus of power undergirding the hidden moments in Black Spanish history, where we only have access to part of the historical narrative.

In the Hombre Africano scene, we see how this man is made indistinguishable from other Black men. Through Oda Mae Brown’s voice, we hear what Hombre Africano says in response to Alphonse Arcelín’s requests to repatriate his remains:

Look what we do with Black people like you around here Arcelín, we dissect them; that’s how you should be, that’s how all of you should be. The Black man is ours, the Black stays. If the Black man leaves, all the Black people will have to go. This is our land, and we rule here. (Albert Sopale Reference Albert Sopale2021:357)

The intention of this statement is clear: the nonidentity of “El Negro de Banyoles” represents the nonidentity of Black people in general. “If the Black man leaves, all the Black people will have to leave” indicates that the Hombre Africano’s individuality cannot be recognized—not so much because treatment must be the same for an entire community but rather because Black life anywhere in Europe is presumed and presented as lacking nuance or particularity. Even today, the museum seems to push the same rhetoric when, on its website, it says:

Despite Francesc Darder’s claims, it was not a “unique specimen” since we know of other people from the same ethnic group who, in the 19th century, a time of significant scientific collections in all parts of the world and curiosity about the unknown, had brought to Europe Bushmen or pygmies who had been shown alive in zoos. Until a few years ago, the remains of a Bushman woman were kept in the Musée del Homme in Paris. (Museus de Banyoles n.d.)

The museum uses the fact that this is not a “unique specimen” to assert that its past use of the embalmed man should not be judged without considering the practice of the time. It further justifies its argument by pointing out that this body was one among many. In Sopale’s play, disidentification through the representation of the Hombre Africano gives voice to a mummy via pop culture icon Oda Mae Brown. This does not mean identifying him or accessing his specific voice. The medium asks someone in the audience to come up with a name, and when she receives one, she points out that it is not needed. The tension between the urge to name the embalmed man and the impossibility of genuinely identifying his erased identity encapsulates the central aim of the work: to force audiences to confront the irresolution and effacement of individuality, while reclaiming these historical figures as touchpoints for recognizing a shared community and history. Here, disidentification is a collective task performed in relation to historical victims of colonial violence who continue to be invisibilized in European culture. They are anonymous beings whose anonymity is recovered to explore the violent processes that created them.

La Moreneta

The Migrant Virgin Who Crossed the Mediterranean

The Virgin of Montserrat is the patron saint of Catalonia and one of nine patrons of Spain’s autonomous communities.Footnote 7 Statues of these patron saints are ubiquitous throughout each region. The darkened skin of these statues and paintings has led to the popular nickname “La Moreneta.” Black Virgin images such as this are often associated with the so-called Black Madonnas that circulated widely throughout Romanesque Europe (Begg [Reference Begg1985] 2011:21). In the case of La Moreneta, however, this dark coloration likely resulted from varnish applied to the faces and hands, which deepened over time due to natural aging and 19th-century repainting. Although their original colors were probably different, the label “Black” attached to these images reflects a historical simplification and reduction of Black life, rooted in longstanding patterns of racialization and erasure (Heng Reference Heng2018:181).

In an effort to appeal to racialized groups with divergent spiritual practices, the Catholic Church has historically utilized the imagery of Blessed Virgins with nonwhite features. Black Madonnas and Indigenous Blessed Virgins have proven effective in engaging the nonwhite population in devotional practices. However, rather than exploring the “imaginary of the dominated,”Footnote 8 Sopale’s La Moreneta establishes a critique of this Catholic symbol by following an approach similar to that of Blackface y otras vergüenzas. In this performance, Sopale interrogates the oversimplification and invisibility imposed on Black life through dominant religious iconography. The racialized Virgin epitomizes the Church’s longstanding strategy of coopting nonwhite identities to expand its reach. However, these efforts fail to genuinely engage with the complexities of Black spiritual subjectivities outside the white Christian framework.

The performance was staged in several Spanish cities, including Madrid and Barcelona, and typically ended with an audience dialog, as is common in Sopale’s works. At the 12 June 2022 performance at the Museu Granollers in Granollers, Catalonia, the theatrical space enabled Sopale to engage the audience in an immersive staging, including visual materials displayed on a screen in the background. This iteration begins with her entering barefoot behind the attendees. She walks onto the stage, unfolds a golden emergency blanket like those given to migrants rescued from the Mediterranean, and dons it as the Virgin’s cloak. She crowns herself and sits on a throne draped with the same material. Speaking into the microphone, she says:

I am not a mother

I am not La Moreneta

I am not the Mother of God

Mothers are not Black

The Mother of God cannot be Black (in Museu Granollers Reference Granollers2022)

As Sopale layers recordings of the phrase “The mother of God cannot be Black,” the aggressive repetition creates an audio overload dominating the theatre’s acoustic space. Although the line ostensibly reiterates the denial of the dark-skinned Madonna, on further reflection, the sheer sonic saturation paradoxically drowns out and muddles the meaning itself. This aesthetic effect hints at the ultimate futility of racial gatekeeping around cultural and spiritual icons; such platitudes become meaningless noise. Instead, the sheer multiplicity of disembodied vocals chanting these words evokes the institutionalized white supremacist notions targeting sacred Black femininity. The theatrical technique engulfs the audience within these pervasive cultural currents, persistently questioning their legitimacy and worth. In another key moment in the monolog, La Moreneta explains:

The Mother of God cannot be Black

She would remain impassive

I am not the mother of God

Who would tell the story

In Monserrat

She would be locked up in a migrant center

Or dead in the Mediterranean

She would be deported

Raped

A trafficking victim (in Museu Granollers Reference Granollers2022)

In using Black womanhood to critically examine religious iconography, La Moreneta highlights the complex interplay between race and spirituality. Sopale’s appropriation of Catholic visual motifs points to efforts to diversify such imagery in the name of religious outreach as grounded in hegemonic white ideologies. However, she moves beyond deconstruction by using the symbols she critiques to offer an alternative representation of Black identity. This work highlights the one-dimensional flattening of Black spirituality inherent in the Catholic adoption of physically ethnic yet ideologically white Virgin figures. Centering on the racialized Madonna, Sopale calls attention to the need for a more nuanced and substantive representation of Black life in religious iconography and discourse.

While seemingly rejecting La Moreneta, the repeated phrase protests the constraints imposed upon Black women, who cannot inhabit sacred roles, such as the Virgin Mary. The mantra’s saturated repetition calls attention to the dominant power of white supremacist notions of purity and piety. Recloaking herself in a gold blanket, Sopale reclaims the mantle of spiritual authority. Her words establish a defiant self-identification that resists the prescribed notion of Black womanhood.

The phrase “I’m not La Moreneta” on the surface rejects La Moreneta yet protests the constraints placed on Black women, neither fully assimilating nor rejecting these ideologies, in line with Muñoz’s formulation. As the performance develops, the erasure of meaning through repetition reveals the failure of language to convey Black women’s complex experiences under racism and patriarchy. Overall, Sopale’s multilayered performance occupies a liminal space that reveals and subverts the constraints of the dominant ideology by disidentifying iterative auditory intervention.

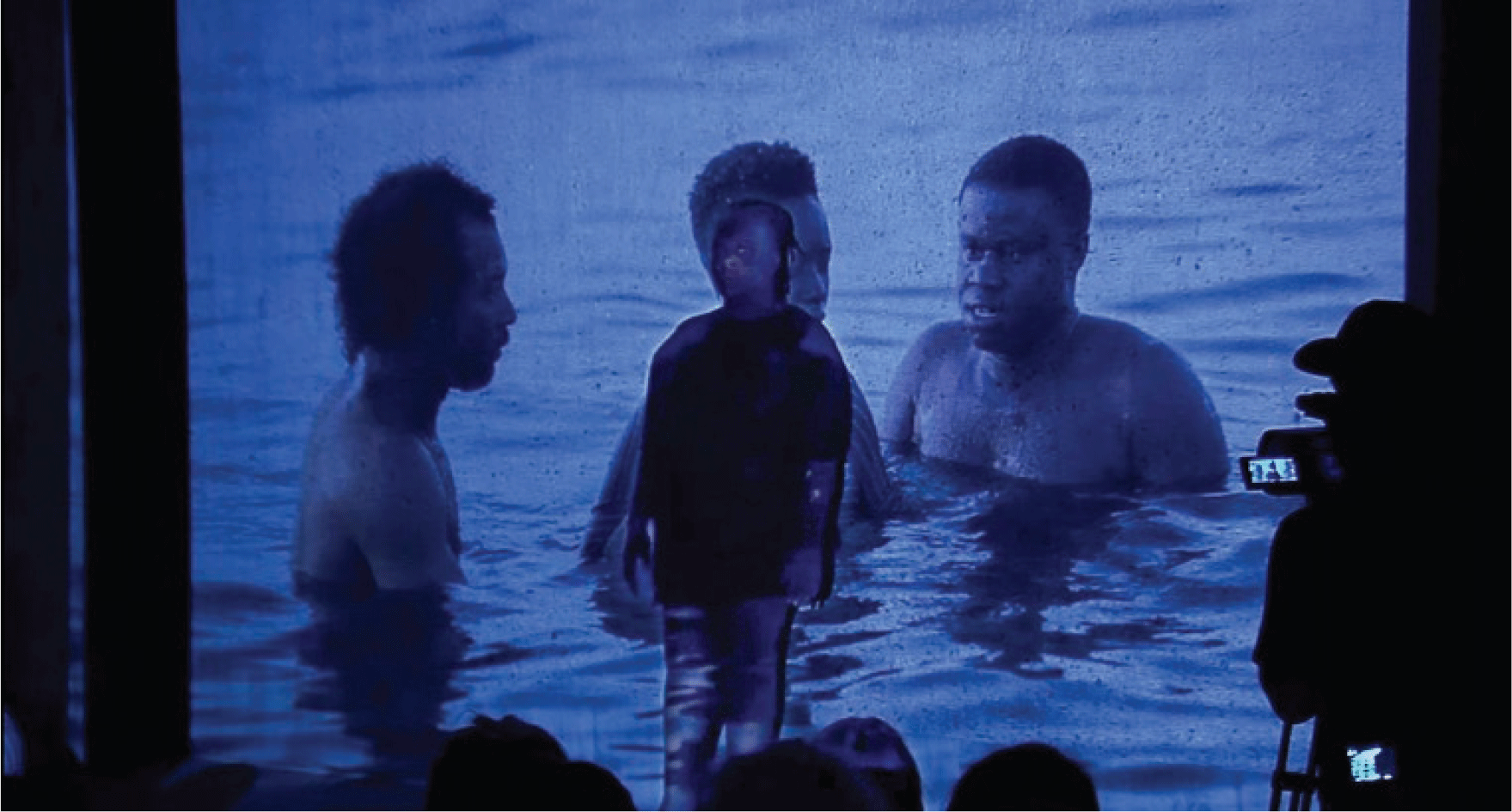

Ten minutes into the performance, the lights dim to darkness, and the voiceover transitions the scene to a new visual focus as stills from Sally Fenaux Barleycorn’s short film Unburied (2019) are projected onto the back wall. The voiceover stops. The film stills show a beachside gathering that depicts a burial ritual—in the film, a memorial for migrants lost at sea as they tried to enter Europe. They present a stark contrast to the earlier scene with the aggressive sonic repetition of “The mother of God cannot be Black” that dominates the theatrical space. Rather than depicting this overwhelming audio environment, these still images show Black individuals standing in silence, the water reaching their waists, their heads bowed, the stillness of their poses emphasized by the calm water surrounding them.

Unburied also explores disidentification by showcasing a Black woman in her twenties driving home after finishing her overnight shift. It is 6:00 a.m. in Barcelona, but the streets remain dark and deserted. The radio murmurs quietly, reciting the daily news, and her mind wanders as she drives the familiar route home: “The city council has proposed a 19 mile per hour speed limit…” the anchor announces without inflection, and in the same tone continues: “In the Mediterranean, a migrant vessel likely holding 150 to 300 passengers was found abandoned…” (Barleycorn Reference Barleycorn2019). The anchor explains that “since 1 January of this year [2019], 508 people have died attempting to cross the sea in Europe. In 2018, 2,297 lives were lost. Despite ongoing deaths, NGO rescue ships continue to be blocked from leaving ports in Spain, Greece, and Italy” (Barleycorn Reference Barleycorn2019). The young woman’s knuckles grip the steering wheel as tears fall from her eyes. She presses harder on the gas pedal as her crying escalates. Unable to contain her grief, she speeds as if on autopilot to the beach, where the camera changes focus and now stays with a solemn group of a dozen gathered at the shoreline. Darkness fades as the first hint of sunrise illuminates the horizon. The group stands silent, half-immersed in the water, clutching a tree trunk they had carved into a face. Their heads are bowed, some weeping quietly as they begin to chant prayers in Igbo. These words echo grief and reverence. When the first rays of light peak over the sea, they gently release their carved trunk into the water. It bobs softly as the current catches it, carrying the symbolic figure away from the mourners. The mourners remain, their heads turned toward the horizon, water lapping at their bodies. The hand-carved visage bound for unknown shores is a tragic monument to those who have never completed their journeys.

The last segment of La Moreneta is an example of what Christina Sharpe calls the “orthography of the wake,” a term that encapsulates the lingering effects of historical trauma on present-day Black communities (2016). The wake on the beach challenges traditional narratives, guiding us to view these images not as mere remnants of the past but as prompts in ongoing conversations on race, identity, and memory. Sharpe’s concept offers a symbolic framework for understanding how contemporary Black artists, writers, and thinkers inscribe the lingering impact of historical trauma on the form and content of their work. “Wake” evokes multiple resonances: the ritual of watching the dead, the disturbance left after a ship passes by, and awakening from sleep or ignorance. For Sharpe, the wake becomes a motif for the persistent aftermath of slavery’s unspeakable violence, the enduring echoes of brutality that shape Black life in the “afterlife” of bondage. She argues that this wake cannot be neatly contained in the past; it flows continuously into the present. Following Sharpe’s wake, La Moreneta challenges conventional linear narratives that posit the history of slavery as over and done. This performance brings to life ruptured kinships, submerged memories, and imaginings of long-denied justice, conjuring absented voices and revealing the past’s chokehold on the present.

Where Unburied centers on an individual’s emotional unraveling, the underlying grief resonates at the margins of narrative resolution. Similar to the short film, La Moreneta does not return to conventional closure; instead, it drifts into ominous rumination and pays respect beside the grievers. This requiem for lost African migrants suggests rituals echoing far from sociopolitical centrality yet pulsing with emotional integrity beneath official narratives and outside the dominant visual frequencies. Sopale’s ghostly index of unanswered trauma remains unanswered in contemporary Spain.

Sharpe proposes that postslavery Black art can be viewed as “spelling out” the reverberations of historical racial trauma into visible aesthetic form (2016:167). Likewise, the ghostly concluding images of communal mourning reflect what Tavia Nyong’o terms “lower frequencies”: obscure registers of Blackness operating in shadows, evading dominant modes of visibility. Working at lower frequencies allows for more ambiguity and opacity as a means of resistance; it privileges ciphers, rumors, illusions, and allusions over direct revelation (Nyong’o Reference Nyong’o2010:96). It demarcates spaces where alternative histories, futures, and modes of relations can be teased out. This entails a delicate strategic balance between visibility/invisibility and legibility/illegibility in these peripheral, subdominant discourses. Lower frequencies delineate a liminal zone of potentiality that resonates outside the audible spectrum and the purview of the mainstream.

La Moreneta strategically oscillates between revealing and obscuring the racialized and colonial undertones of the Blessed Virgin mythos. Sopale’s Virgin alludes obliquely to the plight of drowned migrants, hinting at connections beyond surface appearance. Likewise, her juxtaposition with images from Unburied allows the play to activate lower frequencies that transmit covert recognition of marginalized perspectives. Rather than direct revelations, these fleeting moments of visibility serve as glimpses of suppressed realities flickering at the edge of perception. La Moreneta demonstrates how lower frequencies can provide a liminal space to bring alternative histories and identities that evade the dominant culture to the surface.

Sopale’s metatheatrical techniques in Blackface y otras vergüenzas and La Moreneta estrange audiences and expose the artificiality undergirding the naturalized fiction of race. Her strategic humor and invocations of historical and cultural figures prompt a critical reflection on the objectification of Black female bodies across history. Ultimately, Sopale’s metatheatrical use of blackface serves to disidentify blackface as a problematic means of enacting symbolic violence. Her plays in performance compel audiences to confront historical racial trauma and its enduring legacies. This aesthetic approach aligns with Muñoz’s formulation of disidentification as a means for marginalized artists to hijack, expose, and reshape the racialized codes of dominant cultural texts, countering hegemonic stereotypes and envisioning empowered Afro-Spanish subjectivities.

Figure 1. Silvia Sopale plays Oda Mae Brown, the medium who facilitates the appearances of several Black historical figures in Blackface y otras vergüenzas, Barcelona, 2019. (Photo by Heidi Ramírez; courtesy of Silvia Sopale)

Figure 2. La Negra Tomasa pours white powder on herself, mirroring the actions of Indianos during the Santa Cruz de La Palma celebration. Blackface y otras vergüenzas, Barcelona, 2019. (Photo by Heidi Ramírez; courtesy of Silvia Sopale)

Figure 3. Víctor Lorenzo Díaz Molina in blackface at the Santa Cruz de La Palma celebration, 2019. (Photo by Saúl Santos; courtesy of Silvia Sopale)

Figure 4. Silvia Sopale, lit to appear dark blue, portrays Saartjie (Sarah) Baartman. Here, her nudity conveys Baartman’s lack of agency while her gaze restores agency and humanity. Blackface y otras vergüenzas, Barcelona, 2019. (Photo by Heidi Ramírez; courtesy of Silvia Sopale)

Figure 5. “A Pair of Broad Bottoms.” Saartje (Sarah) Baartman stands in profile to the left, back-to-back with Grenville, in old-fashioned court dress. Print by William Heath, 1810. (© The Trustees of the British Museum; shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International [CC BY-NC-SA 4.0] license)

Figure 6. Silvia Sopale wears an ornate golden crown and aluminum foil cape, embodying the Virgin Mary and also evoking the makeshift blankets used by migrants rescued at sea. La Moreneta, the Granollers Museum, Catalonia, 22 June 2022. (Screenshot by Marcelo Carosi)

Figure 7. Silvia Sopale superimposed onto photos of grieving migrants, referencing the muted “lower frequencies” of Black life. La Moreneta, the Granollers Museum, Catalonia, 22 June 2022. (Screenshot by Marcelo Carosi)