1. Introduction

Task-based language teaching (TBLT) argues that learners acquire second language (L2) knowledge incidentally through performing tasks (Bygate, Reference Bygate2020; Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Skehan, Li, Shintani and Lambert2020; Skehan, Reference Skehan2003), which has been adequately supported by empirical evidence (Bryfonski & McKay, Reference Bryfonski and McKay2019; Robinson, Reference Robinson2011). In light of this, researchers have also suggested bridging second language writing and TBLT scholarship to explore how writing tasks can promote language learning by investigating writing performance under various task conditions (Manchón, Reference Manchón and Manchón2011b, Reference Manchón, Byrnes and Manchón2014; Zhang, Reference Zhang2013). Abundant studies have investigated the association between cognitive writing task complexity and L2 writing performance (Ong & Zhang, Reference Ong and Zhang2010; Xu & Zhang, Reference Xu, Zhang, Johnson and Tabari2025; J. Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2025), confirming the positive role of task-based writing instruction (e.g. Kormos, Reference Kormos2011). However, not much is understood about how individual differences (IDs) influence the extent to which L2 learners use the target language through task-based writing instruction. Within the framework of TBLT, Lambert & Aubrey et al. (Reference Lambert, Gong and Zhang2023) believe that IDs play a role in all levels of cognitive processing and foster incidental language acquisition. Likewise, Kormos (Reference Kormos2012) posits that IDs influence all four interactive and recursive writing processes (i.e. planning, translating, execution, and monitoring). These arguments provide theoretical underpinnings for the role of IDs in facilitating language use in L2 writing, but more empirical evidence is needed.

Among various learner IDs, willingness to communicate (WTC) warrants closer examination to better understand its role in task-based writing instruction (L. J. Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Fathi, Mohammad Hosseini, Derakhshesh and Mehraein2025). Second language WTC is investigated as a conative variable that can indicate learners’ intention to engage in L2 communicative activities (Dörnyei, Reference Dörnyei2005; MacIntyre et al., Reference MacIntyre, Clément, Dörnyei and Noels1998). Since WTC research takes a holistic approach to exploring variables that influence L2 learners’ communicative activities, it has the potential to deepen our understanding of the interplay between learner IDs and task features alongside their effects on task performance (Aubrey & Yashima, Reference Aubrey, Yashima, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023; Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2024a). Research has revealed that L2 WTC positively contributes to learners’ willingness to initiate complex language activities and improves their performance (Dörnyei & Kormos, Reference Dörnyei and Kormos2000; MacIntyre et al., Reference MacIntyre, Babin and Clément1999; Wood, Reference Wood2016). However, L2 WTC is currently measured by language-domain-general scales, which overlooks the distinctiveness of sub-constructs of language learning (Aubrey & Yashima, Reference Aubrey, Yashima, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023). Amidst this backdrop, Zhang and Zhang (Reference Zhang and Zhang2024c) proposed the concept of L2 writing WTC, building on MacIntyre et al.’s (Reference MacIntyre, Clément, Dörnyei and Noels1998) L2 WTC model. Even though writing is a more reflective and solitary process than speaking, it still involves a writer’s readiness and intention to convey meaning to an imagined or real audience. Thus in their conceptualization, L2 writing WTC is defined as learners’ readiness to initiate and engage in written communication in the L2 for communicative purposes, even in the absence of immediate interlocutors. Their L2 writing WTC model reveals a five-factor underlying structure: writing task traits, English language ideology, writing teacher support, interest in English language, and self-perception of English language proficiency.

This study aimed to explore the independent and interactive effects of L2 writing WTC, L2 writing proficiency, and writing task complexity on L2 writing performance using decision-making writing tasks. L2 (writing) proficiency was included as it is a well-documented variable that influences L2 performance. Two groups of upper-intermediate L2 English learners participated in this research. Quantitative data were collected from them following a within-between-participant factorial design. The participants’ L2 writing WTC was surveyed using the L2 writing WTC scale developed and validated by Zhang and Zhang (Reference Zhang and Zhang2024b), while L2 writing proficiency was assessed through an IELTS writing task. Decision-making writing tasks were selected as the task type because they can elicit consistent patterns for assessing linguistic complexity and accuracy, thereby minimizing the influence of topic effects (Foster & Skehan, Reference Skehan1996). Writing task complexity was manipulated along number of elements to represent low and high cognitive demands. L2 writing performance was measured through the lens of syntactic complexity, lexical complexity, accuracy, and fluency. The data were analyzed through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and hierarchical multiple regression, among others. In doing so, we discussed how L2 writing WTC, L2 writing proficiency, and writing task manipulation influenced L2 writing performance independently and interactively, thereby offering theoretical and pedagogical implications.

2. Literature review

2.1 ID-task complexity interaction within task-based language teaching

Framed primarily within the context of oral interaction, major theories in second language acquisition (SLA) have previously downplayed the language learning potential of L2 writing. However, in consideration of the large proportion of literacy activities in language learning practice and real-world communication, researchers call for more attention to L2 learning through performing writing tasks (Manchón, Reference Manchón and Manchón2011b; Ortega & Carson, Reference Ortega, Carson, Silva and Matsuda2010). For example, Manchón (Reference Manchón and Manchón2011a) argues that individual L2 learners develop their language knowledge and skills through their engagement with L2 writing tasks. Her review (Manchón, Reference Manchón and Manchón2011b) of relevant theories and empirical evidence revealed the mediating role of task and learner variables on L2 writing. This finding echoes TBLT in essence that the interplay between learner factors (e.g. affective, cognitive, and conative) and task factors (e.g. task design features) influences L2 writing performance (Lambert & Gong et al., Reference Lambert, Gong and Zhang2023; Robinson, Reference Robinson2011). The learner IDs commonly found to mediate learners’ task performance have been grouped into four categories: affective, cognitive, conative, and sociodemographic (Li, Reference Li2024). Together, these categories provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the diverse factors that are believed to influence language learning outcomes. Thus, a better understanding of L2 writing performance may be generated within the framework of TBLT in conjunction with learner IDs (Lambert & Aubrey et al., Reference Lambert, Gong and Zhang2023; Manchón, Reference Manchón, Byrnes and Manchón2014).

To explore L2 writing performance, writing research from a task-oriented approach manipulates task design features (e.g. topic and type), task implementations (e.g. task preparation), or other task-related variables (e.g. teacher), and, therefore, examines their performance effects on linguistic (e.g. complexity, accuracy, and fluency) and discourse features (e.g. language-related episode; Aubrey & Yashima, Reference Aubrey, Yashima, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023; Lambert & Aubrey, Reference Lambert, Aubrey, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023; Skehan, Reference Skehan2009). The results, in turn, help with designing, implementing, and sequencing pedagogic tasks and the design of task-based syllabi (Long, Reference Long2015; Robinson, Reference Robinson2003). Two major theories that explain the performance effects of tasks from cognitive approaches coexist. The limited capacity hypothesis argues that accuracy and complexity compete for limited human attentional resources and, consequently, will not increase simultaneously (Skehan, Reference Skehan2009; Skehan & Foster, Reference Skehan, Foster and Robinson2001). On the other hand, the cognition hypothesis (Robinson, Reference Robinson2011) believes that L2 pedagogic tasks should be designed and sequenced in view of increases in cognitive task complexity, so as to approximate real-world task demands. In so doing, simple writing tasks consolidate existing L2 knowledge and complex writing tasks extend the L2 repertoire. Specifically, Robinson’s (Reference Robinson2011) classification of task complexity offers an operationalizable framework on the basis that L2 pedagogic tasks can be sequenced built on the increases in cognitive demands. Under this framework, increases along the resource-directing dimension lead to more complex, more accurate, but less fluent learner production. In contrast, increases along the resource-dispersing dimension result in less complex, accurate, and fluent L2 output.

As Johnson’s (Reference Johnson2017) review reports, the most commonly manipulated task design features and conditions hypothesized to impact task complexity in L2 writing research include number of elements, reasoning demands, and the provision of planning time. The results showed that L2 writers produced more complex and accurate language in tasks that required more reasoning demands (e.g. Kormos, Reference Kormos2011). Moreover, it was revealed that the provision of planning time significantly increased syntactic complexity and accuracy of learner production within between-participants research designs (e.g. Ong & Zhang, Reference Ong and Zhang2010). Even though the manipulation of number of elements has garnered enormous scholarly attention, its performance effect on textual indices remains inconclusive. This phenomenon could be attributed to the misalignment between the metrics and the task- and learner-specific linguistic features (Johnson, Reference Johnson2017). Overall, L2 writing research within the TBLT framework has made significant achievements regarding L2 writing performance provisioned by the manipulation of task variables.

Another important consideration is how to evaluate the effects of task features and learner IDs on language performance, particularly through the quality of learner’s language production. Skehan’s (Reference Skehan1996) framework for TBLT implementation seeks to reconcile the meaning-focus of tasks with the need for attention to linguistic form. To this end, he proposed complexity, accuracy, and fluency (CAF), later expanded to CALF with the inclusion of lexis, as the three central goals in TBLT. These goals provide a useful lens for understanding how learners allocate attentional and cognitive resources among different aspects of language. Skehan also introduced a dual-processing model relating to the dynamic interplay between rule-based construction and lexicalized retrieval to lay the theoretical groundwork for the trade-offs between complexity, accuracy, and fluency. Since then, the CALF model has been widely applied to examine learners’ language performance. However, its relationship with long-term language development remains debated (e.g. Lambert & Kormos, Reference Lambert and Kormos2014; Pallotti, Reference Pallotti2009). Moreover, CALF is not inherently a measure of ID variation, and some alternative approaches have been proposed (see Lambert & Aubrey, Reference Lambert, Aubrey, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023, for a review). Despite these critiques, CALF remains a useful tool for examining performance-based reflections of ID-task complexity interaction in TBLT. For example, Lambert and Zhang (Reference Lambert and Zhang2019) explored how conative factors such as engagement might influence performance dimensions operationalized through CAF dimensions, revealing some trade-off effects for task engagement. In this light, CALF can be positioned not as measures of learner ID effects per se, but as observable outcomes that can be indirectly shaped by learner IDs during task performance, especially under cognitively different task conditions.

A wide range of metrics have been developed to measure CALF in SLA and L2 writing research (Johnson & Tabari, Reference Johnson and Tabari2025). Early research adopted large-grained metrics to assess key dimensions of syntactic complexity, including length of production unit, subordination, coordination, and phrasal structures (X. Lu, Reference Lu2010). Recent studies have also introduced usage-based (Kyle & Crossley, Reference Kyle and Crossley2018) and dependency-based (Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2024c) approaches to tap into more fine-grained and nuanced syntactic features. A typical framework for analyzing lexical complexity involves three key dimensions: lexical diversity, lexical sophistication, and lexical density (Bulté & Housen, Reference Bulté, Housen, Housen, Kuiken and Vedder2012). Lexical diversity refers to the range of productive vocabulary used in a text (Maamuujav, Reference Maamuujav2021). Lexical sophistication measures the percentage of sophisticated words (Laufer & Nation, Reference Laufer and Nation1995), while lexical density captures the ratio of content words to function words, reflecting the informational load of a text (Bui, Reference Bui2021). Accuracy measures can be divided into two categories: local measures, which examine the accuracy of specific linguistic features, and global measures, which assess overall accuracy holistically through segmentation. Johnson’s (Reference Johnson2017) review revealed that, in task-based L2 writing research, error-free T-units per T-unit and errors per T-unit were the two most commonly adopted accuracy metrics. In L2 writing research, fluency has traditionally been assessed by measures such as total words produced or words per minute (Johnson, Reference Johnson2017). Recent studies also suggest using keystroke logging and eye-tracking technologies to measure fluency more precisely (Chukharev-Hudilainen et al., Reference Chukharev-Hudilainen, Saricaoglu, Torrance and Feng2019), although their use remains limited due to restricted access to such tools.

2.2 Role of conative individual differences in task-based language teaching

Albeit well-designed and sequenced tasks are believed to offer L2 learners language learning opportunities, the degree to which learners capitalize on these opportunities varies (Lambert & Aubrey et al., Reference Lambert, Gong and Zhang2023). To account for this phenomenon, researchers have turned to IDs for insight. These are argued to influence various stages of writing, including planning, formulation, transcribing, and editing, leading to variation in learning efficiency through writing (Kormos, Reference Kormos2012). Early research explored how cognitive IDs would influence L2 writing performance with the mediation of task-related variables (Kormos & Trebits, Reference Kormos and Trebits2012; Manchón & Sanz, Reference Manchón and Sanz2023). Against the affective turn in SLA, recent studies focus on affective and conative factors whose interactions with task design features and conditions contribute to a fuller understanding of task performance (Lambert, Reference Lambert2017). However, there is a scarcity of studies that combine IDs and TBLT in L2 writing research.

Conative IDs indicate ‘learners’ direction, effort, and determination in learning the language’ (Lambert & Aubrey et al., Reference Lambert, Gong and Zhang2023). Various levels of cognitive processing in language learning can be influenced by conative factors, including comprehension, attention, encoding, and retrieval (Lambert, Reference Lambert2017; Lambert & Aubrey et al., Reference Lambert, Gong and Zhang2023). In SLA research, engagement, motivation, and WTC are three well-documented conative variables that are complementary yet independent constructs. Motivation lies at a more fundamental level, with engagement representing its observable manifestation (Yoon & Kim, Reference Yoon, Kim and Li2024), and WTC reflects the psychological readiness that precedes communicative action. In other words, learners’ motivational basis for language learning is transformed into successful outcomes through engagement (Dörnyei, Reference Dörnyei, Wen and Ahmadian2019) as well as WTC. In the realm of TBLT, motivation and engagement have been theorized in relation to task-oriented instructions (Hiver & Wu, Reference Hiver, Wu, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023). Adopting a process-centered approach, task motivation, a multi-componential construct, is proposed to capture the dynamic motivational variations during task completion (Dörnyei, Reference Dörnyei, Wen and Ahmadian2019). In a similar vein, Ellis et al. (Reference Ellis, Skehan, Li, Shintani and Lambert2020) interpret motivation in TBLT as an amalgamation of general L2 motives, attitudes toward immediate learning contexts, and task-specific motivation. Cumulative empirical evidence has shown that task motivation improves L2 learners’ engagement in tasks and task performance (see a review by Kormos & Wilby, Reference Kormos, Wilby, Lamb, Csizér, Henry and Ryan2019). Engagement in TBLT refers to learners’ involvement and commitment in tasks to activate meaningful learning (Yoon & Kim, Reference Yoon, Kim and Li2024). Task engagement is a multi-dimensional construct encompassing cognitive, social, behavioral, and affective factors (Philp & Duchesne, Reference Philp and Duchesne2016). Studies have revealed that task engagement fluctuates depending on task design features, task implementation conditions, learner-internal variables, and instructional factors (Aubrey et al., Reference Aubrey, King and Almukhaild2022; Yoon & Kim, Reference Yoon, Kim and Li2024). In marked contrast to the attention given to its counterparts, L2 WTC has been underrepresented in TBLT research.

2.3 L2 writing willingness to communicate

Initially grounded in L1 communication research, studies on WTC aimed to enhance individuals’ engagement in communication (McCroskey, Reference McCroskey1992). Meanwhile, noticing that many L2 learners avoid communication despite advanced linguistic competence, researchers have called for inquiries into the roles of affective and conative factors (Dörnyei, Reference Dörnyei1998, Reference Dörnyei2005), such as motivation, anxiety, and WTC, in initiating and sustaining communication in an L2. Among these factors, WTC is receiving growing attention, since it is considered a key site for affective and conative variation during L2 performance, particularly from a task-oriented perspective, as evidenced by neural and physiological data (Lambert, Reference Lambert2025). Consequently, WTC was extended to L2 research to shed light on the role of learner characteristics in language learning. L2 WTC is defined as L2 learners’ ‘readiness to enter into discourse at a specific time with a specific person or persons, using an L2’ (MacIntyre et al., Reference MacIntyre, Clément, Dörnyei and Noels1998, p. 547). Research has demonstrated that L2 WTC is a complex construct shaped by multiple learner-internal factors (e.g. motivation, attitudes toward L2, language proficiency, and L2 interest; Eddy-U, Reference Eddy-U2015; Peng, Reference Peng2012; Sato, Reference Sato2023; Teimouri, Reference Teimouri2017; Yashima et al., Reference Yashima, Zenuk‐Nishide and Shimizu2004) and learner-external factors (e.g. peer, teacher, classroom environment, and task feature; Peng & Woodrow, Reference Peng and Woodrow2010; Yashima et al., Reference Yashima, MacIntyre and Ikeda2018; Zarrinabadi, Reference Zarrinabadi2014; J. Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Beckmann and Beckmann2018). Empirical studies have confirmed that L2 WTC fosters positive emotions and enhances engagement, thereby contributing to improved language performance in L2 learning (Dörnyei & Kormos, Reference Dörnyei and Kormos2000; Hiver & Wu, Reference Hiver, Wu, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023; MacIntyre et al., Reference MacIntyre, Babin and Clément1999). However, some studies have reported no significant effect of WTC on L2 performance (Joe et al., Reference Joe, Hiver and Al-Hoorie2017; Yashima, Reference Yashima2002).

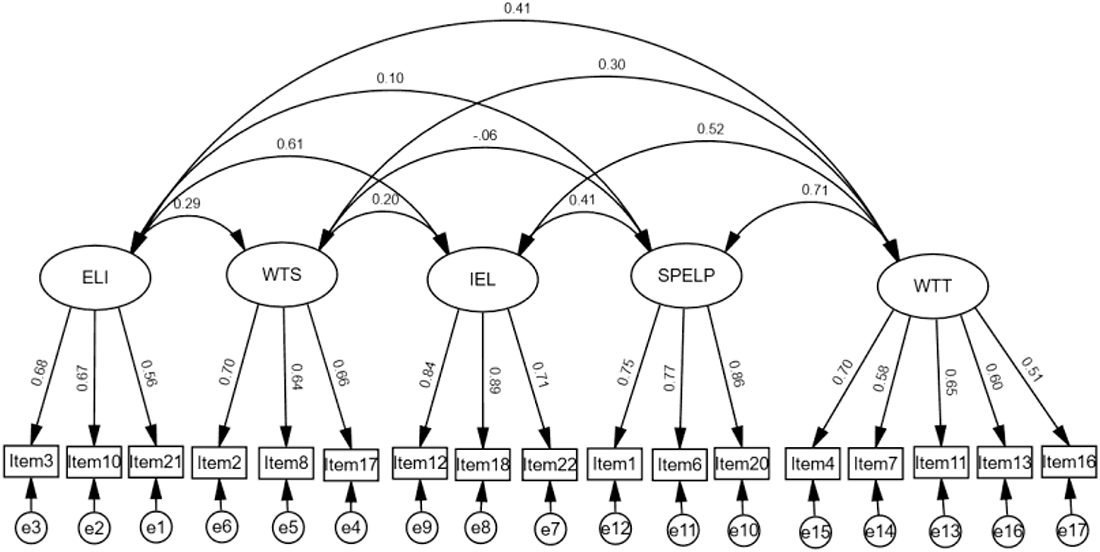

Previous L2 WTC studies were mainly conceptualized and operationalized in the context of oral communication, leaving L2 WTC in textual meaning-making activities under-explored. Although without the immediate presence of interlocutors, L2 writing retains communicative aspects (e.g. audience awareness and intention to be understood), through which writing can serve as a tool for self-expression and interaction with imagined or real audiences. While MacIntyre et al. (Reference MacIntyre, Baker, Clément and Conrod2001) and Weaver (Reference Weaver2005) extended their WTC scales to include written discourse, these scales lacked validity statistics and are now considered outdated. Moreover, although various methods, including observation, interviews, teacher ratings, and neural and psychophysiological tools (Lambert, Reference Lambert2025), have been used to measure WTC, questionnaires remain the most practical and widely adopted approach. Against this backdrop, Zhang and Zhang (Reference Zhang and Zhang2024b) theorized an L2 writing-domain-specific WTC model alongside an L2 writing WTC scale. This model was developed and validated with MacIntyre et al.’s (Reference MacIntyre, Clément, Dörnyei and Noels1998) L2 WTC model as the baseline. In this influential model, WTC was considered the last psychological step before engaging in actual communication, influenced by both situated and psychological variables. These variables included personality traits, affective-cognitive features, motivational propensities, and situational cues. However, MacIntyre et al.’s (Reference MacIntyre, Clément, Dörnyei and Noels1998) conceptualization of WTC was developed within the context of spoken interaction, emphasizing immediacy and the presence of interlocutor(s), which digresses from the typically solitary and delayed nature of L2 writing in terms of communication. Although writing is largely monologic in nature, it still involves the anticipation of an audience and the expression of intended meaning. This thus necessitates an examination of the concept of L2 writing WTC. On the basis of the relevant literature, Zhang’s and Zhang’s (Reference Zhang and Zhang2024c) model was developed and validated through a methodologically rigorous triangulation of both qualitative and quantitative data, revealing a five-factor underlying structure (see Fig. 1): interest in English language (e.g. Aubrey & Yashima, Reference Aubrey, Yashima, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023), English language ideology (e.g. Yashima et al., Reference Yashima, Zenuk‐Nishide and Shimizu2004), self-perception of English language proficiency (e.g. Peng & Woodrow, Reference Peng and Woodrow2010), writing task traits (e.g. Aubrey & Yashima, Reference Aubrey, Yashima, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023; J. Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Beckmann and Beckmann2018), and writing teacher support (e.g. Yashima et al., Reference Yashima, MacIntyre and Ikeda2018). Interest in English reflected motivational predispositions; English language ideology and self-perception of English language proficiency represented affective-cognitive features; and writing task traits and writing teacher support were classified as writing-specific antecedents, as outlined in MacIntyre et al.’s (Reference MacIntyre, Clément, Dörnyei and Noels1998) L2 WTC model. Hence, L2 writing WTC, shaped by motivational, affective, cognitive, and contextual factors, reflects learners’ readiness and motivation to express meanings in writing for communicative purposes. In Zhang’s & Zhang’s (Reference Zhang and Zhang2024c) scale, L2 writing WTC is assessed indirectly through its underlying constructs, which differs from traditional WTC scales that measure the construct directly. Compared to MacIntyre et al.’s (Reference MacIntyre, Clément, Dörnyei and Noels1998) model, the underlying factors in L. J. Zhang and Zhang’s (Reference Zhang and Zhang2024a) model exhibited more writing-domain-specific features. This model thus provides a robust means of exploring the interplay between conative IDs and writing task manipulation.

Figure 1. L2 writing WTC model.

3. The present study

Based on the literature review, we sought to investigate ID-treatment interaction in task-based writing instruction. Specifically, we explored the role of L2 writing WTC in conjunction with L2 writing proficiency in task-mediated L2 writing performance examined by syntactic complexity, lexical complexity, accuracy, and fluency. We took L2 writing proficiency into consideration, because several studies have indicated that L2 proficiency interacts with cognitive IDs to influence L2 writing performance (e.g. Manchón et al., Reference Manchón, McBride, Martínez and Vasylets2023). However, the interaction between L2 proficiency and conative IDs has not yet been investigated. Hence, we intended to answer the following two questions:

RQ1. To what extent do L2 writing WTC, L2 writing proficiency, and task complexity independently affect task-mediated L2 writing performance assessed by syntactic complexity, lexical complexity, accuracy, and fluency?

RQ2. To what extent do L2 writing WTC, L2 writing proficiency, and task complexity interactively affect task-mediated L2 writing performance assessed by syntactic complexity, lexical complexity, accuracy, and fluency?

4. Method

4.1 Research design and participants

We employed a within-between-participant factorial design to collect quantitative data, with two levels of writing task complexity as the within-participant variables and L2 writing WTC and L2 writing proficiency as the between-participant variables. The dependent variables were L2 writing performance measured by syntactic complexity, lexical complexity, accuracy, and fluency.

Participants were 151 L2 English undergraduate students (123 females and 28 males) with upper-intermediate English proficiency, recruited through convenience sampling. They all majored in English language and literature, which suggests they likely had higher WTC than students in other majors. Their first language was Chinese. The background information showed that their ages varied from 18 to 22 years (M = 19.510, SD = .639), and they had received 10.626 years of formal English instruction on average.

4.2 Instruments

4.2.1 The simple and complex writing tasks

To represent varying degrees of cognitive demands, two decision-making writing tasks (see Appendix A) were adopted from Rahimi & Zhang (Reference Rahimi and Zhang2018), which differed in number of elements. As specified in the prompts, the task-taker would assume the role of a government official responsible for allocating funds to public projects based on their importance to the local community and providing explanations for their decisions. The cognitively more demanding task asked task-takers to allocate one billion to six projects. The cognitively simpler task required task-takers to allocate 0.5 billion to three projects. According to Robinson’s (Reference Robinson and Mayo2007) triadic componential framework, the simple and complex writing tasks differed in number of elements along the resource-directing dimension. The participants were given 35 minutes to finish each task and handwrite at least 250 words.

4.2.2. The task perception questionnaire

Following previous studies on confirming differences in tasks’ cognitive demands (Révész, Reference Révész2014; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhang and Gaffney2022), this study used a writing task perception questionnaire to assess participants’ perceptions of task difficulty and other task-related feelings. Adapted from Kourtali & Révész (Reference Kourtali and Révész2020), the questionnaire was a post-task self-assessment on a nine-point response scale.

4.2.3. Measure of L2 writing proficiency

The participants’ L2 writing proficiency was measured by an argumentative writing assignment modelled after Part 2 of the writing module of the IELTS (the International English Language Testing System) Academic test. The participants were required to write an essay of at least 250 words in 30 minutes. The topic was about the differences between online education and face-to-face education.

4.2.4. L2 writing WTC scale

WTC was measured using the L2 writing WTC scale (Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2024b). This questionnaire consisted of 17 items based on a seven-point Likert scale (see Appendix B), tapping into five underlying variables: writing task traits (WTT; e.g. Item 13: ‘For every writing topic, I feel interested’), writing teacher support (WTS; e.g. Item 8: ‘Before I write, my teacher gives me good guidance’), English language ideology (ELI; e.g. Item 3: ‘English is important for my future career’), self-perception of English language proficiency (SPELP; e.g. Item 6: ‘My English proficiency is very high’), and interest in English language (IEL; e.g. Item 22: ‘I am interested in learning English writing’). To uphold methodological rigor, the development and validation of this scale followed a three-phase sequential embedded mixed-methods design, triangulating both qualitative and quantitative data from various sources. The model fit statistics generated through CFA showed that the hypothesized factor structure aligned well with the observed data, indicating satisfying validity (χ 2 = 199.052; df = 109; χ 2/df = 1.826; TLI = .938; CFI = .950; RMSEA = .062 [.048, .076]; SRMR = .062).

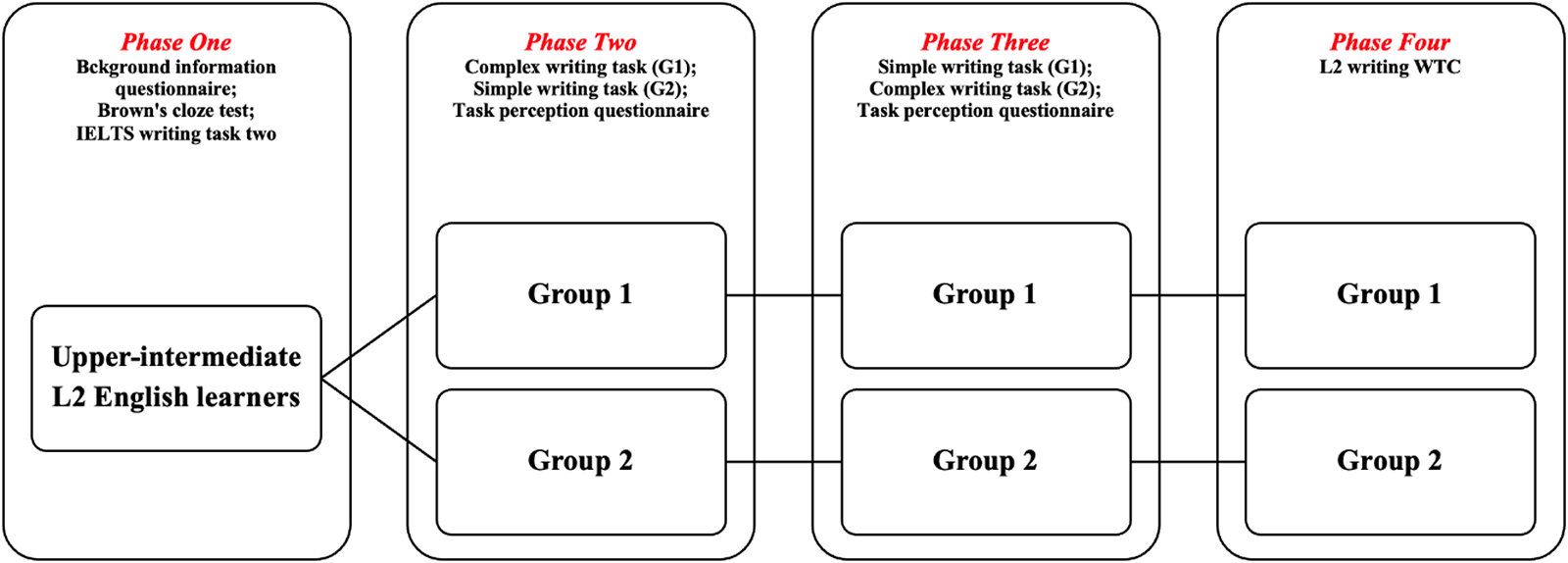

4.3 Data collection

Data were collected in four steps (see Fig. 2). Initially, target L2 English learners were approached. Their language learning and L2 proficiency information was collected by a background information questionnaire (Mackey & Gass, Reference Mackey and Gass2015), Brown’s (Reference Brown1980) cloze test, and an IELTS writing task two. Only upper-intermediate L2 English learners were recruited. They then read the participants’ information sheet and signed the consent form. In Phase Two, they were randomly divided into two groups. Group one completed the complex writing task and the task perception questionnaire, and group two completed the simple task and the task perception questionnaire. In Phase Three, each group completed the other group’s tasks in Phase Two. The two tasks were counterbalanced to avoid an order effect. In the final step, both groups finished the L2 writing WTC scale. Each phase was conducted on different but nearby dates.

Figure 2. Four-step data collection.

4.4 Measurement of L2 writing performance

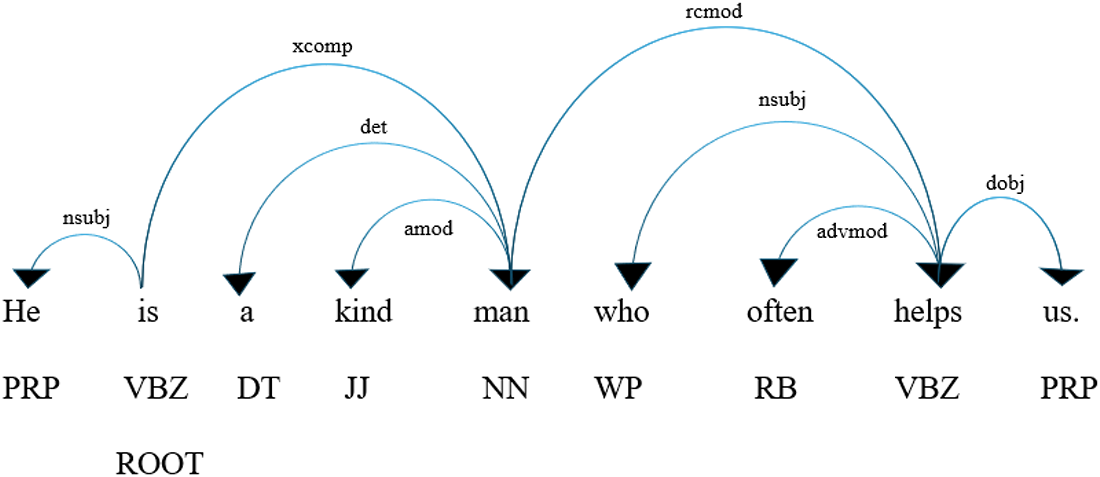

We assessed L2 writing performance using measures of syntactic complexity, lexical complexity, accuracy, and fluency, as summarized in Table 1. As for syntactic complexity, we adopted four indices that could indicate task-mediated syntactic performance in our target population. The main target syntactic structures were noun phrases and prepositional phrases, two structures illuminated in the literature as predictors of intermediate-to-advanced syntactic performance (Biber et al., Reference Biber, Gray and Poonpon2011; Mazgutova & Kormos, Reference Mazgutova and Kormos2015). To calculate the frequencies of these structures, we used dependency parsing and self-compiled learner corpora (see an example from Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2024b). The collected writing data were compiled into two dependency-annotated learner corpora. Dependency parsing, which defines syntax as binary and asymmetric relations between two words (Liu, Reference Liu2008; Tesnière, Reference Tesnière1959), is widely recognized as a robust approach to representing syntactic structures. It is less sensitive to word order and provides a transparent and straightforward representation of predicate-argument structures (De Marneffe & Nivre, Reference De Marneffe and Nivre2019). This method has gained traction in SLA for measuring syntactic complexity (e.g. Kyle & Crossley, Reference Kyle and Crossley2018). Figure 3 demonstrates the dependency relations in an example sentence. Additionally, mean length of T-unit (MLT) was included as a general indicator of syntactic performance and was calculated by the L2 Syntactic Complexity Analyzer (L2SCA; X. Lu, Reference Lu2010).

Figure 3. Example of a dependency-annotated sentence.

Table 1. Summary of performance measures

Lexical complexity was subdivided into three components: lexical diversity, sophistication, and density. Lexical diversity refers to the range of vocabulary used; lexical sophistication indicates the percentage of sophisticated words; and lexical density reflects the proportion of content words to function words. These components were measured by three indices: MTLD for lexical diversity, COCA academic frequency for lexical sophistication, and content types per type for lexical density. The calculations were performed using the Tool for the Automatic Analysis of Lexical Diversity (TAALAD; Kyle et al., Reference Kyle, Crossley and Jarvis2021) and the Tool for the Automatic Analysis of Lexical Sophistication (TAALES; Kyle & Crossley, Reference Kyle and Crossley2015). Accuracy was measured using a global index: errors per T-unit, a metric widely adopted in L2 writing performance research (Johnson, Reference Johnson2017). Errors were coded by the first author and a research assistant, guided by a self-developed error-coding manual on the basis of previous studies. The manual identified errors at two levels: lexis (ten types, including spelling, word choice, capitalization, and singular/plural forms, among others) and syntax (12 types, including redundancy, missing components, and word order, among others). Before starting the coding process, both coders studied the coding manual together and resolved any ambiguities through discussion. The first author coded all the data, and 40% of the dataset was randomly chosen for double coding by both the first author and the research assistant. The coding achieved high reliability, with intra-coder reliability at 96% and inter-coder reliability at 94%. We measured fluency by counting the total number of words per text, as suggested by previous research (Johnson, Reference Johnson2017).

4.5 Data rating

The writing samples were assessed against Jacobs et al.’s (Reference Jacobs, Zinkgraf, Wormuth, Hartfiel and Hughey1981) analytical writing scheme. This rubric consists of five categories: content (30 pts), language use (25 pts), organization (20 pts), vocabulary (20 pts), and mechanics (5 pts). The two raters were English instructors in tertiary educational institutions with writing scoring experiences. They received a training session before the rating began, which aimed to help them become familiar with the writing topics and rating criteria. During this session, they were asked to read and discuss the rating rubric together. Later, they rated ten samples independently and negotiated discrepancies in scores. In the rating, the final score was calculated by averaging two scores. If two holistic scores for one sample differed by more than ten points, the score given by a third rater was final.

4.6 Data analysis

Quantitative data analyses were divided into three parts. Firstly, to prepare our analyses for the research questions, we 1) tested the model fit of the L2 writing WTC scale through CFA, 2) generated descriptive data of our independent and dependent variables, and 3) examined the means of task difficulties and performance measures between the simple and complex tasks using paired sample t-tests. Secondly, we performed correlation analyses between independent variables (i.e. L2 writing proficiency and L2 writing WTC) and dependent variables (i.e. performance measures) in simple and complex tasks. Thirdly, we conducted several rounds of hierarchical multiple regressions, in which the outcome variables were performance measures that showed significant correlations, and the independent variables were L2 writing proficiency, L2 writing WTC and its sub-components, and the interaction measures between L2 writing proficiency, L2 writing WTC, and its sub-components. The interaction measures were created by first standardizing the variables and then multiplying the standardized scores. In these regression analyses, models were entered in a stepwise fashion to examine the incremental contribution of new variables to the explanation of variance in the outcome variable. Based on the correlation results, WTC variables were entered first, followed by writing proficiency and then their interaction terms. Each model tested whether the additional predictor significantly improved the model’s explanatory power by comparing model fit indices (i.e. R2, adjusted R2, and ΔR2) and F-tests.

5. Results

5.1 Preliminary analyses and independent effects of L2 writing WTC and L2 writing proficiency on L2 writing performance

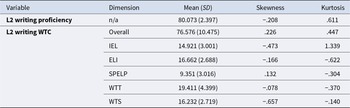

Before revealing the main results, we present the prerequisite statistics necessary for the subsequent investigation of the research questions. First, the underlying model of L2 writing WTC was examined through CFA, as shown in Figure. 4. The model fit indices were: χ 2 = 263.995; df = 109; χ2/df = 2.422; TLI = .801; CFI = .840; RMSEA = .097; SRMR = .078; and GFI = .984. Notably, χ2/df (2.42) and SRMR (.078) fell within acceptable bounds, and GFI (.984) suggested strong overall model fit (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). Among them, SRMR is less sensitive to sample size and is considered a more stable indicator. However, TLI, CFI, and RMSEA were below ideal thresholds. The reason is that they are sensitive to sample size and are known to overestimate misfit in small samples, such as in this study (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Kaniskan and McCoach2015; Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Hau and Wen2004). Taken together, these indices suggested that the model fit was acceptable. Furthermore, factor loadings of all items were above the acceptable level (> .50) and eight items reached the ideal threshold (> .70; Hair et al., Reference Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham2006). In addition, Marsh et al. (Reference Marsh, Hau and Wen2004) caution against strict cut-offs for fit indices and emphasize a holistic theory-based evaluation of model fit. This instrument is based on the previously validated L2 writing WTC scale developed in Zhang and Zhang (Reference Zhang and Zhang2024b), which demonstrated good model fit. Our use of the same instrument ensures theoretical consistency and allows for meaningful comparisons. Consequently, the model was retained for subsequent analyses. Next, in Tables 2 and 3, we display the descriptive statistics for variables in our research, namely L2 writing proficiency, L2 writing WTC, task difficulty, and performance measures in the simple and complex tasks. No multi-collinearity was detected among the performance measures. Finally, we show the differences in task difficulty and performance measures between the simple and complex tasks. The results (see Table 4) revealed significant differences between the two writing tasks in all nine measures.

Figure 4. The five-factor model of L2 writing WTC emerged in the CFA analysis.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for L2 writing proficiency and L2 writing WTC (n = 151)

Note: IEL refers to interest in English language, ELI refers to English language ideology, SPELP refers to self-perception of English language proficiency, WTT refers to writing task traits, WTS refers to writing teacher support.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for task difficulty and writing performance in the simple and complex tasks (n = 151)

Table 4. Effects of task complexity on task difficulty and performance measures (n = 151)

The summary of correlations between the performance measures, L2 writing proficiency, and L2 writing WTC indicated that L2 writing proficiency was not significantly correlated with the participants’ writing performance either in the simple or the complex task. In contrast, L2 writing WTC and its sub-components were correlated significantly with several performance measures. In the simple task, L2 writing WTC (r = .163, p < .05) and interest in English language (r = .238, p < .01) were positively correlated with post-prepositional phrases per clause, and self-perception of English language proficiency (r = .195, p < .05) was positively correlated with total number of words per text. However, writing teacher support (r = − .268, p < .001) was negatively correlated with errors per T-unit. In the complex task, L2 writing WTC (r = .260, p < .01), self-perception of English language proficiency (r = .235, p < .01), and writing task traits (r = .208, p < .05) were positively correlated with total number of words per text, interest in English language (r = .230, p < .01) was positively associated with post-prepositional phrases per clause, self-perception of English language proficiency (r = .201, p < .05) was positively associated with adjective/relative clauses per clause, and writing teacher support (r = − .214, p < .01) was negatively associated with errors per T-unit. We also noted that the size and nature of several comparisons differed in the simple and complex tasks, though they were insignificant (e.g. between L2 writing WTC and noun phrases per clause, between English language ideology and adjective/relative clauses per clause).

5.2 Interactive effects of L2 writing WTC and L2 writing proficiency on L2 writing performance in the simple task

In the following part, we report the results of hierarchical regressions. In these regression analyses, the outcome variables were the complexity, accuracy, and fluency measures that showed significant correlations, and the predictors were L2 writing proficiency, L2 writing WTC, and its sub-components, as well as their interaction terms. In the simple task, the results (see Table 5) showed that interest in English language significantly predicted post-prepositional phrases per clause (Model 1: β = .022, p < .01). Models 1, 2, 3 and 4 were significant, suggesting that the set of their predictors as a whole significantly predicted post-prepositional phrases per clause. However, a further ANOVA test revealed that the additional predictors in Models 2, 3, and 4 did not provide a significantly better fit than Model 1. Model 1 explained 5% of the variance in post-prepositional phrases per clause, F (1, 149) = 8.971, p < .01. As for errors per T-unit, the results (see Table 6) showed that writing teacher support was a significant predictor of errors per T-unit (Model 1: β = − .042, p < .001). All three models significantly predicted errors per T-unit. The follow-up ANOVA test indicated no significant improvement in model fit. Model 1 explained 6.6% of the variance in errors per T-unit, F (1, 149) = 11.550, p < .001. With regard to the total number of words per text, it was significantly predicted by self-perception of English language proficiency (Model 1: β = 2.735, p < .05; see Table 7). All three models significantly predicted total number of words per text, with Model 2 explaining 4.5% of the variance in total number of words per text, F (2, 148) = 4.505, p < .05. The percentage of variance explained by L2 writing WTC and its sub-components was significant but relatively small. This is understandable, as each performance measure adopted in this study taps into a local and specific aspect of L2 writing performance.

Table 5. Hierarchical regression analysis predicting post-prepositional phrases per clause in the simple task (n = 151)

* Note: p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Table 6. Hierarchical regression analysis predicting errors per T-unit in the simple task (n = 151)

* Note: p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Table 7. Hierarchical regression analysis predicting total number of words per text in the simple task (n = 151)

* Note: p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

5.3 Interactive effects of L2 writing WTC and L2 writing proficiency on L2 writing performance in the complex task

In the complex task, the frequency of post-prepositional phrases per clause was significantly predicted by interest in the English language (Model 1: β = .024, p < .01; see Table 8). All three models significantly predicted post-prepositional phrases per clause, with Model 1 explaining 4.7% of the variance in post-prepositional phrases per clause, F (1, 149) = 8.323, p < .01. As for adjective/relative clauses per clause, it was significantly predicted by self-perception of English language proficiency (Model 1: β = .005, p < .05; see Table 9). Model 3 explained 3.9% of the variance in adjective/relative clauses per clause, F (3, 147) = 3.021, p < .05. With regard to errors per T-unit, it was significantly predicted by writing teacher support (Model 1: β = − .044, p < .01), as shown in Table 10. Models 1, 2, and 3 were significant, with Model 2 explaining 4.8% of the variance in errors per T-unit, F (2, 148) = 4.777, p < .01, as indicated by ANOVA. When it came to total number of words per text, it was significantly predicted by no variable (see Table 11). All seven models predicted total number of words per text, but Model 2 had the biggest explanatory power, with 6.5% of the variance in total number of words per text explained by it, F (2, 148) = 6.189, p < .01.

Table 8. Hierarchical regression analysis predicting post-prepositional phrases per clause in the complex task (n = 151)

* Note: p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Table 9. Hierarchical regression analysis predicting adjective/relative clauses per clause in the complex task (n = 151)

* Note: p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Table 10. Hierarchical regression analysis predicting errors per T-unit in the complex task (n = 151)

* Note: p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Table 11. Hierarchical regression analysis predicting total number of words per text in the complex task (n = 151)

* Note: p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

6. Discussion

6.1 Independent effects of L2 writing WTC, task complexity, and L2 writing proficiency

Overall, L2 writing WTC and most of its sub-components had significant effects on various aspects of L2 writing performance under different task complexity conditions, with the exception of lexical complexity. These results indicate that L2 writing WTC and its sub-constructs played an active role in influencing variations in task-mediated L2 writing performance. Compared to findings from previous studies, this finding suggests that conative IDs might have a more prominent effect on L2 writing than cognitive IDs. For example, following a similar research design, Manchón et al. (Reference Manchón, McBride, Martínez and Vasylets2023) found that working memory did not significantly affect L2 writing performance among similar participants (i.e. university students). Writing, as a recursive and process-oriented meaning-making activity, allows for sustained planning and revision, making it less dependent on real-time cognitive processing. However, conative traits related to persistence and effort could motivate or demotivate learners to invest greater cognitive efforts in their writing, leading to various performances. That said, this comparison should be interpreted with caution, and future studies are encouraged to include both conative and cognitive variables to enable direct comparisons of their relative influences on L2 writing performance.

Such an observation differs from the results found in Joe et al. (Reference Joe, Hiver and Al-Hoorie2017) and Yashima (Reference Yashima2002), which reported no associations between WTC and L2 performance. This discrepancy could be attributed to different measures of WTC and L2 performance. Both of their measures were initially used to assess WTC among L1 learners. In contrast, the L2 writing WTC scale used in this study was developed on the basis of MacIntyre et al.’s (Reference MacIntyre, Clément, Dörnyei and Noels1998) L2 WTC model. Furthermore, they used self-reported proficiency and overall L2 achievements as performance, while this research assessed L2 writing performance through the lenses of comparatively more local metrics, namely syntactic complexity, lexical complexity, accuracy, and fluency.

Zooming in on the interrelationships among the sub-constructs of L2 writing WTC, we found that, compared to affective, cognitive, and writing-specific features, the motivational predisposition turned out to be a more prominent moderator of L2 writing performance. This indicates that motivational factors may have more stable and enduring effects on L2 writing performance, whereas other sub-components, such as emotional states or task-specific perceptions, may fluctuate more readily in response to situational factors. These findings call for longitudinal designs to trace the stability and long-term predictive power of motivational predispositions across different writing contexts. Moreover, experimental methods could be used to better understand how dynamic components of WTC interact with motivational factors during L2 writing tasks. Investigating these temporal dynamics can deepen our understanding of how to effectively tailor instructional strategies within an ID-informed TBLT framework.

The correlation and hierarchical regression analyses both indicate that the explanatory power of WTC and its sub-components on L2 writing performance was small, though statistically significant. This is likely reasonable, given that the metrics used to assess L2 writing performance in this study focused on specific and micro-level aspects of this multi-faceted construct. Likewise, previous studies have reported that the correlations between aspects of L2 writing performance and affective IDs were significant but not strong (e.g. Abdi Tabari et al., Reference Abdi Tabari, Farahanynia and Botes2025). However, the results also suggest that, while WTC was important, other variables might have a more significant impact on L2 writing performance. They likely operated in concert with WTC to influence L2 writing outcomes, which warrants further investigation to advance a more comprehensively ID-informed approach to task-based writing instruction. Another possible explanation could be the measurement of L2 writing WTC. In this study, we operationalized WTC as a trait-like ID. This left out its task-specific features, which could significantly influence the fluctuation of WTC. Thus, a fuller account of its impact on L2 writing performance can be kept by measuring task-specific WTC on a moment-to-moment basis (Aubrey & Yashima, Reference Aubrey, Yashima, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023; Lambert, Reference Lambert2025).

The associations between WTC and L2 writing performance mostly happened in post-prepositional phrases per clause, errors per T-unit, and total number of words per text, indicating that WTC moderated the frequency of prepositional phrases, accuracy, and fluency in our participants’ writing. The use of prepositional phrases was a fast-developing syntactic feature among our participants, whose English proficiency was at the upper-intermediate level (Biber et al., Reference Biber, Gray and Poonpon2011; Mazgutova & Kormos, Reference Mazgutova and Kormos2015). This finding shows that the effects of WTC on L2 syntactic performance might be on syntactic features that aligned with their syntactic developmental stages. A surprising finding was that writing teacher support was negatively correlated with accuracy in the simple and complex tasks. One interpretation could be that high levels of teacher support might result in an over-reliance on external help rather than assisting L2 writing performance. Lastly, participants with higher WTC performed better in text generation. Probably, high WTC helped them engage better in the writing tasks, enhancing their automaticity and retrieval speed in language production. Also, when WTC is high, L2 learners could be more focused on meaning-making rather than form-monitoring, leading to more continuous language generation. However, WTC had no effect on L2 lexical performance. This indicates that high-WTC participants might prioritize message delivery rather than lexical variation and sophistication, relying on familiar and frequently used words for ease of communication. Alternatively, lexical performance may be more dependent on exposure and vocabulary learning than conative IDs. Together, the results suggest that L2 writing WTC had significant yet different impacts on various dimensions of L2 writing performance. These findings underscore the multifaceted role of WTC in shaping writing performance and highlight the need to consider how different components of WTC may uniquely influence distinct features of L2 written production.

Our results reveal that participants demonstrated significantly greater syntactic complexity, lexical complexity, and fluency in the complex task, but lower accuracy. These results support Skehan’s (Reference Skehan2009, Reference Skehan, Foster and Robinson2001) claim that trade-offs occur among complexity, accuracy, and fluency in performing tasks. Under increased cognitive demands, L2 learners reallocate attentional resources among linguistic domains, prioritizing one aspect at the expense of the others to facilitate their language use. In our study, participants allocated more cognitive resources to complexity and fluency, leading to reduced accuracy. This trade-off pattern diverges from the prediction of Robinson’s (Reference Robinson2003) cognition hypothesis, which anticipates simultaneous gains in complexity and accuracy under more complex task conditions along the resource-directing dimension. This discrepancy points to the need to further examine how IDs, such as (task-specific) WTC, interact with task demands to influence writing performance. Our study suggests that conative IDs may shape how learners engage with cognitively demanding tasks, highlighting the value of incorporating conative constructs into task-based L2 writing frameworks. Future research should investigate whether such trade-offs are stable across different learner groups and task types to clarify the theoretical boundaries of the current task complexity framework.

This finding also calls for a closer examination of how to measure L2 writing performance. In the previous studies of TBLT research, the effect of number of elements on L2 writing performance was inconclusive (Johnson, Reference Johnson2017). For example, researchers have found that the manipulation of number of elements had positive, negative, and no effects on L2 writing lexical complexity and accuracy, respectively (i.e. Kuiken & Vedder, Reference Kuiken and Vedder2008; Rahimi & Zhang, Reference Rahimi and Zhang2018; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Zhang and Gaffney2023). Such discrepancies could be attributed to variations in the metrics used to assess L2 writing performance. In particular, the measurement of syntactic complexity may not adequately reflect the linguistic features most relevant to specific tasks or learner populations. For example, examining the effect of task complexity through coordination among advanced L2 learners is inappropriate, since coordination mainly develops at an early stage of syntactic acquisition (Mazgutova & Kormos, Reference Mazgutova and Kormos2015). In contrast, more developmentally appropriate metrics can offer greater sensitivity to the syntactic growth trajectory of learners at higher proficiency levels. In this study, the syntactic complexity measures targeted noun phrases and prepositional phrases, which aligned with the participants’ developmental stage of English proficiency, thereby enhancing the validity of the findings. Consequently, the results more accurately reflect the effects of task complexity within this learner profile.

Our data shows no significant effects of L2 writing proficiency on L2 writing performance. This result suggests that, compared to WTC and task complexity, L2 writing proficiency played a more peripheral role in mediating L2 learners’ writing performance. Few studies have linked L2 writing proficiency with L2 writing performance. Manchón et al.’s (Reference Manchón, McBride, Martínez and Vasylets2023) study showed a significant relationship between L2 proficiency and L2 writing performance in syntactic complexity, lexical complexity, accuracy, and fluency. However, their findings do not contradict ours. L2 proficiency in their study was measured by the Oxford Placement Test (OPT) aiming to capture L2 learners’ general language ability, while our L2 writing proficiency assessed by an IELTS writing task only showed the participants’ writing ability, which should differ from general language ability. Besides, their study allowed greater variation in L2 proficiency, whereas, in this study, L2 proficiency was restricted to the upper-intermediate level to minimize participant heterogeneity. More importantly, the collective results call for a more systematic study on the influence of L2 (writing) proficiency on L2 writing performance.

6.2 Interactions of L2 writing WTC, task complexity, and L2 writing proficiency

Our results did not observe interactive effects between L2 proficiency and WTC on L2 writing performance either in the simple or the complex task. This suggests that the two variables did not work mutually to influence L2 writing performance. Previous research has not specifically investigated the interactive effects between L2 writing proficiency and conative IDs, whereas studies have explored the interactive effects between L2 proficiency and cognitive IDs such as working memory (e.g. Y. Lu, Reference Lu, Wen, Mota and Mcneill2015; Manchón et al., Reference Manchón, McBride, Martínez and Vasylets2023). In general, they revealed an absence of interactive effects between the two variables on L2 writing performance. Collectively, these results may indicate that conative/cognitive IDs and L2 proficiency operate independently rather than in a mutually reinforcing manner in relation to L2 writing performance. Therefore, future research may benefit from investigating task-sensitive WTC without necessarily considering L2 proficiency as a mediating factor.

Alternatively, this finding could be attributed to the homogeneity of the participants’ English proficiency. Since the participants’ L2 (writing) proficiency was limited to the upper-intermediate level, their writing performance might already be strong, reducing the opportunity for WTC to interact with proficiency in a way that would produce a significant difference. If many participants were highly proficient in L2 writing, their performance might have already been near the upper limit. Thus, this result does not eliminate the possibility of an interactive effect between L2 writing WTC and proficiency at other proficiency levels that leads to variations in complexity, accuracy, and fluency. This speculation calls for future research that investigates the effects of L2 writing WTC on L2 writing performance across proficiency levels.

The effects of L2 writing WTC on L2 writing performance differed in the simple and complex writing tasks, suggesting a complex interaction between L2 writing WTC and writing task complexity. Specifically, the results show that the associations between L2 writing WTC and syntactic and fluency performance were stronger in the cognitively more demanding task. Such an observation supports Robinson’s (Reference Robinson2003) claim that IDs increasingly differentiate performance on tasks that make greater cognitive demands on learners. According to this claim, complex tasks induce greater language processing, which could potentially amplify IDs such as WTC. Robinson made this argument based on empirical evidence investigating the relationship between cognitive IDs and L2 performance. Our result indicates that the same situation applies to conative IDs. This result underscores the idea that, in TBLT, task design and implementation should be sensitive to learner IDs, as they may either enhance or suppress the expression of learners’ linguistic potential. Therefore, investigating the interface between learner variables and task features holds significant promise for facilitating the effectiveness of task-based instruction. On the other side, this result also supports the need for a task-specific framework for L2 WTC (Aubrey & Yashima, Reference Aubrey, Yashima, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023). Such a framework will more effectively promote learners’ WTC by accounting for the roles of task modality and task difficulty.

One possible explanation to this result is related to the synergy between cognitive resources and conative predispositions. Complex writing tasks impose higher cognitive demands, thus requiring greater attentional resources (e.g. executive control and linguistic processing; Robinson, Reference Robinson2003; Skehan & Foster, Reference Skehan, Foster and Robinson2001). Conative IDs may become influential in maximizing performance by helping allocate these resources more effectively. Consequently, L2 learners with higher WTC are more engaged, motivated, and capable in their writing process when the task is more cognitively demanding, allowing them to take advantage of the complexity by fully utilizing their syntactic repertoire and maintaining fluency. However, in simple tasks, L2 learners may not need to draw heavily on their motivational and communicative predispositions to produce language, leading to less variability in syntactic performance and less language production. This finding suggests that high WTC might contribute to better performance in complex tasks where the competition for attentional resources was more fierce.

Another possibility is linked to WTC-induced immediate affective variables. The trait-like WTC measured in this study might trigger specific immediate affective responses in learners when faced with particular tasks, depending on task features (i.e. task complexity). Learners with high WTC may have enhanced writing engagement and approach complex tasks more confidently, leading to more sophisticated sentence structures and faster idea generation. This claim can be substantiated by measuring task-specific WTC on a moment-to-moment basis (Aubrey & Yashima, Reference Aubrey, Yashima, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023; Lambert, Reference Lambert2025). Such real-time measurement allows researchers to record dynamic fluctuations in learners’ WTC and examine how these variations link to task performance. To support this endeavour, methodological approaches such as idiodynamic method have been developed to track WTC changes in real time while minimizing disruption to learners’ task engagement (Lambert, Reference Lambert2025).

We also notice the asymmetry of the associations between L2 writing WTC and lexical and accuracy measures were not noticeably different between the tasks. This could be attributed to another level of the trade-off effect between attentional resources, influenced by conative IDs, or distinct cognitive mechanisms underlying lexical complexity and accuracy, which warrants future investigation. In general, these results confirm that L2 learning (through writing) is propelled by a complex mechanism with the active involvement of conative IDs and task features (Lambert & Aubrey et al., Reference Lambert, Gong and Zhang2023; Manchón, Reference Manchón and Manchón2011b).

Apart from the findings directly related to our research questions, the measurement of conative variation in writing and the potential relationship between this variation and language learning are also worth discussion. Although CALF is a direct measure of language performance instead of learning, trade-offs among CALF components during L2 performance can offer insights into language development in TBLT (Lambert & Zhang, Reference Lambert and Zhang2019; Skehan, Reference Skehan1996). For example, cognitively simple tasks help L2 learners consolidate and automatize existing linguistic resources, whereas tasks with increased cognitive demands encourage them to restructure their language systems and expand their L2 repertoire (Lambert & Zhang, Reference Lambert and Zhang2019). From this perspective, the fluctuations in CALF measures observed in our study indicate that WTC dynamically interacts with task complexity conditions to shape the trajectory of L2 learning. This interpretation is supported by recent conative-focused research in TBLT that employed diverse methodological approaches (Hiver & Dao, Reference Hiver and Dao2025; Lambert & Aubrey, Reference Lambert and Aubrey2025; Lambert & Gong et al., Reference Lambert, Gong and Zhang2023; Qahl & Lambert, Reference Qahl and Lambert2025). Despite using different analytic tools, such as engagement in language use, these studies consistently indicate the connections between conative variables and L2 learning outcomes.

7. Conclusion

This article explored the ID-task interaction within task-mediated L2 writing performance, aiming to shed light on their theoretical and pedagogical contributions to TBLT and SLA. Specifically, we investigated how the interactions between L2 writing WTC, L2 writing proficiency, and cognitive task complexity would influence L2 writing performance. We strived for methodological refinements by adopting a newly developed and well-validated L2 writing WTC scale and measured writing performance by gaining insights from corpus linguistics, theoretical linguistics, and SLA. The results confirm the independent and interactive effects of L2 writing WTC, its sub-components, and task complexity on L2 writing performance. While WTC has traditionally been considered crucial for oral tasks because speaking is spontaneous and requires overcoming hesitation, its positive role in writing, an activity that allows for more planning and revision, is overlooked. Our study provides evidence that L2 WTC significantly influences L2 writing performance, with its impact varying based on task complexity conditions, indicating a more prominent role of conative IDs than cognitive IDs in mediating L2 use.

Theoretically, our results yielded evidence of the interplay between IDs and task features in L2 writing performance (Kormos, Reference Kormos2012; Lambert & Aubrey et al., Reference Lambert, Gong and Zhang2023; Manchón, Reference Manchón and Manchón2011b). We highlighted WTC as a promising factor moderating L2 writing and brought the different roles its sub-components played to scholars’ attention. Previous writing models primarily emphasize cognitive traits related to learners’ processing speed in writing tasks. However, our results suggest that incorporating conative predispositions into theoretical writing models may provide a more accurate and comprehensive account of how learners engage with writing tasks. Our findings also have some pedagogical implications. Teachers can help improve students’ writing performance through the improvement in WTC, especially its motivational components, but they should be cautious about providing excessive teacher support. Besides, L2 learners with different individual features may benefit from differential instructional conditions (Kormos, Reference Kormos2012). For instance, complex tasks may help L2 learners with high WTC in leveraging their communicative willingness to enhance L2 writing performance. Also, additional support, scaffolding, or instructional strategies should be provided in cognitively complex L2 pedagogic tasks to help all students, regardless of their WTC levels, manage their cognitive loads. Additionally, to inform more effective task-based teaching practices, the design of L2 pedagogical tasks should consider the interplay between different IDs. This study also has limitations. Our investigation of L2 performance focused on a narrow scope (i.e. complexity, accuracy, and fluency). Future research can examine the role of WTC in other aspects of L2 writing performance to draw a fuller picture. Also, we adopted a static and trait-like measure of L2 WTC, thus leaving its situated and dynamic nature behind. In the future, researchers can examine task-takers’ task-specific WTC to reveal a moment-to-moment interaction between L2 WTC and pedagogic tasks. Furthermore, the relatively small variance explained by WTC and its components suggests that L2 writing performance is the outcome of a complex interaction of conative IDs, task features, and other factors that require future investigation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444825101110

Yujie Zhang is a faculty member of the School of Foreign Studies, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China. He has received his Ph.D. degree in Education (Applied Linguistics and TESOL) from the Faculty of Arts and Education, University of Auckland, New Zealand. His research interests include second language writing, learner individual differences, language teacher education, and writing assessment. His publications have appeared in Assessing Writing, Language Teaching Research, and TESOL Quarterly.

Lawrence Jun Zhang, Ph.D., is Professor of Applied Linguistics and Associate Dean, Faculty of Arts and Education, University of Auckland, New Zealand. His major interests are psychology of language learning and teaching, learner metacognition, the acquisition of L2 written language, and most recently, teacher AI literacy and emotions. His publications appear in Applied Linguistics, Applied Linguistics Review, Assessing Writing, Discourse Processes, Journal of Second Language Writing, Language Teaching Research, Learning and Individual Differences, Metacognition and Learning, Modern Language Journal, RELC Journal, System, TESOL Quarterly, among others. He has worked as Co-Editor-in-Chief for System. In 2016 he was honoured with the recognition by the TESOL International Association (USA) with the award of ‘50@50’, which acknowledged ‘50 Outstanding Leaders’ around the globe in the profession of TESOL at TESOL’s 50th anniversary celebration. In the Stanford University Academic Impact Rankings, he has been listed in the top 2% of most-cited linguists in the world.