Introduction

An essential prediction of spatial models of party competition is that party elites respond to changes in the distribution of voter preferences by updating their policy strategies (Downs, Reference Downs1957; Enelow & Hinich, Reference Enelow and Hinich1984). Empirical studies on party policy shifts consistently find support for such proposition (Adams, Reference Adams2012; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004; Erikson et al., Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson2002; Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995). However, there is weak and inconsistent evidence that voters react to such policy shifts, and notably that they notice whether parties change their policy positions (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Ezrow and Somer‐Topcu2014; Fernandez‐Vazquez, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez2014; Fernandez‐Vazquez & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Fernandez‐Vazquez and Somer‐Topcu2019). This is an important puzzle in the study of party–voter linkages as it challenges not only a logical assumption of spatial models but also the normative foundations of representative democracy (Adams, Reference Adams2012).

An underexplored explanation for such a puzzle can be ascribed to the actions of party elites themselves. We argue that political parties, even if pushed to change their policy positions in response to changes in public opinion, may have an incentive to hide their stances by deemphasizing the issues on which they respond to the public. After all, changes in policy positions are risky as they may signal a lack of commitment (Enelow & Hinich, Reference Enelow and Hinich1984; Tomz & Van Houweling, Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2012), dilute a party's brand and alienate its support base (Lupu, Reference Lupu2014) or jeopardize future coalition arrangements (Van de Wardt et al., Reference Van de Wardt, De Vries and Hobolt2014). These risks are especially high in the case of ‘wedge issues’ that cross‐cut the dominant dimension of political competition (Carmines & Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1986; De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020).

Previous studies have so far analysed the linkage between parties and voters mostly in terms of policy positions. Yet, parties can respond to public opinion by changing both the positions and the salience of their policy agenda (Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2019). In this article, we analyse party responsiveness to public opinion by taking into account both the positions that parties take on an issue and the emphasis they attach to it. We argue that when parties struggle to deal with an issue, they may respond to changes in public preferences, on the one hand, and, on the other, deemphasize the issue as the public moves away from their positions.

We test our argument in a study of mainstream parties’ positions on European integration, an issue on which public opinion has substantially shifted over the last decades. As vote‐maximizing actors motivated by winning governmental positions, mainstream parties are pushed to change their positions on European integration in response to changes in public opinion. Yet, mainstream parties struggle to respond to an increasingly Eurosceptic public for several reasons. First, European Union (EU) issues are hard to reconcile within their historical profile (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). Second, their constituencies are internally divided over the issue (Hobolt & Rodon, Reference Hobolt and Rodon2020; Van de Wardt, Reference Van de Wardt2014). Third, the very fact of governing within European institutions constrains their ability to cater to voter demands (Mair, Reference Mair2013). How do parties respond to public opinion in such a difficult context?

To answer this question, we need to reconstruct the political discourse on European integration as it has evolved over time since parties are expected to anticipate electoral repercussions. Parties dynamically adapt the salience of their discourse between elections in response to political events and the strategies of their competitors (Gessler & Hunger, Reference Gessler and Hunger2022). Moreover, there is causal evidence that public opinion affects political speech right after the dissemination of opinion polls among politicians (Hager & Hilbig, Reference Hager and Hilbig2020). Yet, existing literature on party responsiveness tends to focus on the electoral connection between voter preferences and party positions. Therefore, we still know little about the temporal dynamics of party responsiveness as they unfold continuously between and across elections.

The investigation of these dynamics requires fine‐grained data on both the supply side and the demand side of electoral politics. Therefore, we collected original time‐series data on both party discourse and voter preferences at the semester level over 25 years (1992–2016) in three countries. We reconstructed the political discourse of six mainstream parties in France, Great Britain, and Italy, by means of 11,000 hand‐coded newswires as well as the latent public support for European integration by merging 600 survey marginals in each country via the dyad‐ratio algorithm (Stimson, Reference Stimson1999). Thanks to such data collection, we can analyse how public opinion on European integration has affected the political discourse of mainstream parties from the adoption of the Maastricht Treaty to the aftermath of the Brexit referendum. The selection of three countries with very different institutional rules and party system dynamics may allow us to draw some preliminary conclusions about mainstream parties’ responses to public Euroscepticism.

Results show that, in the period under study, mainstream parties have adapted their positions to the tides of public opinion by moving to less Europhile positions when the public grew Eurosceptic. At the same time, mainstream parties have responded to the increasing Euroscepticism of their electorates by changing the salience of their political discourse on Europe: they deemphasized EU issues as the public grew Eurosceptic. Finally, mainstream parties did not promote their stances on European integration even when they changed those stances to follow the public mood. Although we find that, vis‐à‐vis an increase in public Euroscepticism, mainstream parties speak more about Europe when their positional changes are responsive to voters’ opinions, this difference does not compensate for the strong negative effect of public Euroscepticism on parties’ issue salience.

These results show the importance of analysing parties’ positions and issue salience together in studies of democratic responsiveness, an endeavour that despite many advocates (Basu, Reference Basu2020; Meyer & Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2019; Steenbergen & Scott, Reference Steenbergen and Scott2004) has found little echo in political science. Our findings also contribute to a growing literature that analyses party competition between elections (Gessler & Hunger, Reference Gessler and Hunger2022; Gilardi et al., Reference Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller2022), by showing the relevance of public opinion in the strategic behaviour of parties. Relatedly, the paper contributes to our understanding of the strategies that parties can deploy to hide their positions on issues that they struggle to deal with (Han, Reference Han2020; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Hagemann and Hobolt2021; Koedam, Reference Koedam2021; Rovny, Reference Rovny2012). Finally, the results of this paper speak to debates on the future of European integration, at times when depoliticization does not seem to be any more a feasible option (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016).

How parties respond to changes in public opinion

Party elites may change their policy positions for several reasons, such as prior election outcomes (Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2009; Somer‐Topcu & Zar, Reference Somer‐Topcu and Zar2014), competing parties’ policy shifts (Adams & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Adams and Somer‐Topcu2009) and electoral success (Abou‐Chadi & Krause, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Krause2020) or changes in economic conditions (Haupt, Reference Haupt2010; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Ezrow and Dorussen2011). However, a key prediction of spatial models of party competition is that party policy positions are constrained by the distribution of voter preferences, so that when public opinion changes, parties are expected to adapt their stances accordingly.

Previous research has provided ample evidence that political parties change their positions in response to shifts in public opinion (Adams, Reference Adams2012; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004; Erikson et al., Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson2002; Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995). These studies test whether party positions reflect the opinion of the majority of the electorate (the median voter).Footnote 1 To be sure, parties may also respond to their own supporters and the pivotal actor in electoral contests may not be necessarily the median voter. However, many studies have proved that, independently from the electoral system, mainstream parties, that is parties that regularly alternate in government and have a broad electoral appeal, consistently respond to the median voter (Adams & Somer‐Topcu, Reference Adams and Somer‐Topcu2009; Bischof & Wagner, Reference Bischof and Wagner2020; Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, De Vries and Vis2013).

This type of research assumes that all positional shifts have the same value independently from the importance that parties attach to them. From voters’ perspective, however, a substantial repositioning may go unnoticed if hardly communicated, while even a small policy adjustment may signal a good deal of responsiveness if strongly emphasized. While spatial theorists assume that the salience of an issue remains fixed during party interactions, research on party strategies shows that political parties compete by altering both policy positions and their salience (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). Parties can selectively emphasize issues that are beneficial to them given their reputation among voters (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996; Sides, Reference Sides2006). Likewise, they can deemphasize issues that could jeopardize their support base. In particular, mainstream parties are typically expected to refrain from politicizing ‘wedge issues’, that is issues that would alter the pattern of political competition (Carmines & Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1986; De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020).

Issue salience has long been recognized as an important element of how parties respond to voters. For example, we know that parties respond to public opinion's priorities by emphasizing those issues that are deemed important by the voters (Klüver & Sagarzazu, Reference Klüver and Sagarzazu2016; Sides, Reference Sides2006; Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2014). Yet, although many scholars see spatial and salience theories of party competition as complimentary rather than as rival models (Basu, Reference Basu2020; De Sio & Weber, Reference De Sio and Weber2014; Koedam, Reference Koedam2022; Wagner, Reference Wagner2012), little attention has been paid to how parties strategically combine changes in policy positions and issue salience in response to changes in voter preferences.

Combining spatial and salience theories in the study of party responsiveness

Party elites face a trade‐off when confronted with opinion polls. On the one hand, they risk to lose voters if they do not follow the public. As vote‐maximizing actors motivated by winning governmental positions, parties are sensitive to the potential electoral sanction that a substantial incongruence with the preferences of the median voter could provoke. On the other hand, parties may find it difficult to change their policy positions, as they are especially constrained by past policy commitments and by their reputation and ideological profile (Adams, Reference Adams2012; Meyer, Reference Meyer2013; Somer‐Topcu, Reference Somer‐Topcu2009). Moreover, they risk to upset their core supporters if they drastically deviate from their platform (Ferland, Reference Ferland2020).

How can parties solve this dilemma? Parties can compete both by shifting their positions on an issue and by emphasizing different political issues. The two expectations are based on a fundamental distinction (Elias et al., Reference Elias, Szöcsik and Zuber2015; Steenbergen & Scott, Reference Steenbergen and Scott2004). According to positional theories, parties compete with one another by shifting their stance on issues. This model considers issue salience to be exogenous to competition and party stances to be endogenous. According to salience theories, parties compete with one another by selectively emphasizing issues beneficial to their success. In this case, issue salience is endogenous to competition, while party positions are exogenous. As Steenbergen and Scott (Reference Steenbergen and Scott2004, p. 167) note, ‘in reality, party competition involves strategic choices on both issue salience and issue positions, and a fully specified analysis should treat both of these elements as endogenous’.

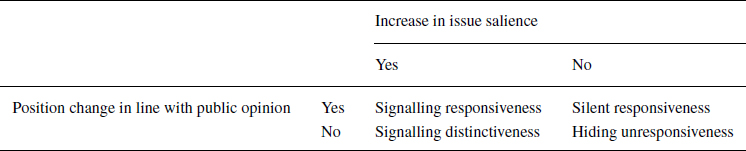

This raises the question of how parties combine positional and salience strategies. Table 1 summarizes the four potential scenarios. We could hypothesize that parties would increase the emphasis on an issue when they change position in accordance with public opinion (signalling responsiveness) and would decrease it in case their positional change is at odds with the public (hiding unresponsiveness). In these most likely and intuitive scenarios, positional responsiveness and issue emphasis are complementary strategies: party elites would only be willing to talk about an issue when their position is electorally advantageous and would silence it otherwise (De Sio & Weber, Reference De Sio and Weber2014). However, we should consider two additional scenarios where positional responsiveness and issue emphasis function as substitutable strategies.

Table 1. Positional responsiveness and salience strategies

First, party elites, rather than following the public, could stick to their position and try to convince voters of the merits of such a position (signalling distinctiveness). In this case, they would decide to emphasize their position even if it is not in line with the public mood. This might be a risky strategy electorally, but a coherent one if policy‐seeking motivations are dominant or if parties want to signal their distinctiveness. Indeed, such a strategy is more likely to be employed by smaller parties (Basu, Reference Basu2020).

Second, party elites may decide to silence their position even when they adapt it to changes in public opinion (silent responsiveness). They would adjust their position with the aim of gaining some immediate electoral advantages or out of fear of being found unresponsive should the issue gain prominence in the party system agenda. Yet, while aligning their positions with evolving public opinion dynamics, party elites may strive to minimize the salience of their adjustments.Footnote 2 This ‘discreet’ approach is motivated by a twofold concern: first, the risk of compromising their credibility with the party's core supporters, potentially leading voters to defect to rival parties; and second, the recognition that a focus on alternative, less divisive policy dimensions presents more viable prospects for electoral success. After all, issue salience is a limited resource that a party can spend, and parties benefit electorally if the debate centres on issues that do not divide their electoral base. Therefore, we argue that this strategy is more likely to be employed by mainstream parties and in the case of ‘wedge issues’, that is issues that cut across the existing line of competition. In such situations, mainstream parties do not just risk to impair their credibility when they deviate from their agenda to follow the median voter. If wedge issues come to dominate the political debate and change the main logic of competition, mainstream parties risk to lose their dominant position in the party system (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020).

How mainstream parties respond to public opinion on European integration

European integration has long been a fundamentally elite‐driven process, and the EU has always been considered an unlikely case to find elite responsiveness to public opinion (Meijers et al., Reference Meijers, Schneider and Zhelyazkova2019). Since the beginning of the 1990s, however, the delegation and pooling of national competences at the EU level have increased demands for public justifications (De Wilde & Zürn, Reference De Wilde and Zürn2012; Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). While Euroscepticism has increased in all countries, most mainstream parties tend to have favourable views of the EU and the integration process (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). Such a representation gap represents a threat not just for democratic legitimacy in the EU but for the electoral prospects of mainstream parties as well. As Hooghe and Marks noted, party elites ‘must look over their shoulder when negotiating European issues. What they see does not reassure them’ (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009 p. 5).

Previous research on party responsiveness to European integration has provided mixed evidence. While some studies show that an ‘electoral connection’ exists between the preferences of the general electorate and party positions in Europe (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Sapir and de Vries2012; Carrubba, Reference Carrubba2001), others have found no evidence of party responsiveness to public opinion across elections (Mattila & Raunio, Reference Mattila and Raunio2012; Rohrschneider & Whitefield, Reference Rohrschneider and Whitefield2016). Still others find that party responsiveness is conditional upon some party characteristics, such as their size (Williams & Spoon, Reference Williams and Spoon2015) or their degree of internal dissent (Spoon & Williams, Reference Spoon and Williams2017). These findings suggest that mainstream parties might be more likely than others to follow the public. They tend to win more votes and are at the same time internally divided on the issue of European integration (Van de Wardt, Reference Van de Wardt2014). Moreover, with few notable exceptions, Europe has hardly played a role in election campaigns (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). European integration remains a typical ‘government issue’, such that the agenda‐setting process is mostly driven by government actions like treaty negotiations or EU summits (Boomgaarden et al., Reference Boomgaarden, Vliegenthart, De Vreese and Schuck2010). Indeed, there is growing evidence that incumbent party elites respond to the preferences of their electorates when they negotiate at the EU level (Hagemann et al., Reference Hagemann, Hobolt and Wratil2017; Schneider, Reference Schneider2019).

At the same time, mainstream parties may struggle to respond to an increasingly Eurosceptic public for several reasons. First, European integration is a typical ‘wedge issue’ that cross‐cuts the traditional left–right alignment and potentially disrupts voter coalitions within and between parties.Footnote 3 As such, it is hard for mainstream parties to reconcile it within their historical ideological profile (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005; Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). Second, mainstream party supporters are internally divided over the issue of European integration (Hobolt & Rodon, Reference Hobolt and Rodon2020; Van de Wardt, Reference Van de Wardt2014). Third, mainstream parties, when in government, participate directly in the EU decision‐making process. Therefore, their capacity to follow public demands may be severely constrained (Mair, Reference Mair2013). According to some scholars, it might be easier for parties to respond to public opinion shifts by altering the emphasis they put on EU issues in their discourse (De Sio et al., Reference De Sio, Franklin and Weber2016). Previous research shows that parties that are more distant from the median voter tend to be more silent on EU issues (Steenbergen & Scott, Reference Steenbergen and Scott2004) and that MPs tend to emphasize EU issues less, the more public opinion sees EU membership as ‘a bad thing’ (Rauh & De Wilde, Reference Rauh and De Wilde2018).

Previous studies of party position and salience strategies thus present us with a puzzle. When the public becomes more Eurosceptic, according to some scholars, mainstream parties are expected to change their positions in line with voter preferences; according to others, they are likely to deemphasize their positions. The current literature would see these two responses as alternative strategies. Facing an increasingly Eurosceptic public, mainstream parties would choose either to change position or to decrease salience. However, as argued above, parties are likely to change both position and salience in response to public opinion. When mainstream parties become more critical of European integration in line with a Eurosceptic turn of public opinion, they could decide to emphasize the issue of European integration to signal their responsiveness. This strategy could be electorally rewarding as it would cater to the demands of the median voter. Yet, it is not a strategy without risks and not only because making visible a change in position could harm the party's credibility. Making EU issues salient would alter the existing dimension of competition thus challenging the dominant position mainstream parties enjoy in the party system. Mainstream party elites will avoid to emphasize their more Eurosceptic positions, even if they are in line with the public mood. Therefore, we expect that mainstream parties do not increase the salience of EU issues, even when they become more critical of the EU after an increase in public Euroscepticism.

Data

In the study of mass‐elite linkages on European integration, research has mainly relied on four sources to measure party positions: party manifestos, expert surveys, hand‐coded campaign articles and voters’ perceptions as measured in post‐election surveys. While each of these measurement strategies has its own merits depending on the research questions, all these sources are limited in that they are discrete measurements with a significant distance between two consecutive time points. In studies of mass‐elite linkages that look at the temporal dynamics between parties and voters, this limitation is problematic. Researchers have to assume that in the years between two consecutive elections, or between two consecutive expert surveys, nothing has occurred in the relationship between voters and parties. Moreover, while alternative measures of different parties’ positions are strongly correlated, Adams and colleagues (Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2019) find no meaningful correlation between alternative measures of party position shifts.

The main innovation of this project lies in the collection of fine‐grained data on party positions on European integration and their salience at the semester level. We collected and coded all public statements of six political parties on EU issues that were reported in national newswires. Newswires have two key advantages over other sources. First, they are short texts meant to report party positions as they unfold over time. Therefore, the resulting time series capture how parties dynamically position themselves on European integration in relation to concrete issues, debates and events that inform the evolution of the EU. Second, they constitute a middle ground between the controlled communication of the parties (press releases or manifestos) and the framed reports of the media, constrained by editorial requirements. As such, they give a more realistic picture of the actual salience of EU issues in a party's discourse.

We collected data on the positions and issue salience of the two main parties in three countries: France, Italy and the United Kingdom. Those are among the largest European countries, which offer very different institutional rules, party system dynamics and public Euroscepticism trajectories. The United Kingdom can be considered a ‘two‐and‐a‐half party system’, in which the predominance of the two larger parties remains quite strong. On the contrary, France and Italy are multi‐party systems. However, while the French majoritarian system has favoured for a long time – and at least until the end of the period we study – the two main parties on the left and the right, the mixed electoral systems that governed Italian elections led to the emergence of a fragmented system where larger parties are more strongly encouraged to form pre‐electoral coalitions. These differences in party systems dynamics mean that the mainstream parties under study vary with respect to several important factors that may influence their responsiveness to the public. They are of varying sizes (relative to their competitors), display varying levels of intra‐party and intra‐coalition dissent on the issue of European integration and experience varying levels of threat from Eurosceptic parties.

We collected our corpus of newswires from three main national news agencies: Reuters in the United Kingdom, Agence France Presse (AFP) in France and Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata (ANSA) in Italy.Footnote 4 To collect our newswire corpus, we adopted a stratified sampling strategy both at the party level and at the party leader level. We first compiled a list of keywords to identify newswires related to the issue of European integration. Then, for our list of keywords we ran separate searches for each party, and within each party, for each leader's term.Footnote 5 We selected two mainstream parties, one from the left and one from the right, in each of the three countries, and we collected data for a period that goes approximately from the Maastricht treaty to the aftermath of the Brexit referendum (1992–2016).Footnote 6

In total, around 18,000 newswires were collected and 11,000 were coded. Five coders were trained for this effort until they achieved very good levels of intercoder reliability.Footnote 7 Each newswire was coded manually by means of a core‐sentence analysis (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). This approach is a relational method of analysis that reduces each grammatical sentence to a ‘core sentence’ structure that includes only a subject (a political actor), an object (an issue) and a relation between the two. In this study, we code the relationship between a party (or its leaders and politicians) and an EU‐related object (e.g., a treaty, an institution, a policy or the EU in general).Footnote 8 As a newswire is a short text that exposes the essential information, for each newswire, we coded a maximum of three core sentences, including the title. We used a three‐point scale ranging from −1 to +1 to code the direction of the relationship between the actor and the issue. −1 indicates a negative evaluation of the object by the subject, or a criticism, whereas +1 indicates a positive evaluation. 0 indicates a neutral or ambivalent position. We aggregate the coded information at the semester level by averaging the scores of all core sentences in a semester. In the Online Appendix, we cross‐validate our measure of party positions with three existing data sets: the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Jolly et al., Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022), the PolDem data based on hand‐coding of newspaper articles (Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi2020) and the manifesto data produced by the MARPOR project (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Lewandowski, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Werner2017).

We define a party's issue salience as the importance that the party attaches to the issue in the public debate. We measure the salience of European integration for each party as the proportion of EU‐related newswires over the total number of newswires that mention the party or its leader in the title. To get these totals, we ran the same search that we used to collect our corpus, but without the EU‐related keywords. For each party, we thus scraped the title and date of all the newswires that contained the name of the party, its abbreviation or the surname of its leader and we aggregated the count at the semester level. These totals constitute the denominator of our salience measure, while the nominator is given by the number of coded newswires in each semester.Footnote 9

For our main independent variable, we introduce an original measure of public opinion's ‘mood’ on European integration that provides a measure of the median voter's position.Footnote 10 This is based on the dyad‐ratios algorithm proposed by Stimson (Reference Stimson1999) to reconstruct time series with interruptions.Footnote 11 It creates a continuous regular time series from scattered survey marginals. By aggregating answers to many questions, this procedure allows us to capture the shared variation of different series. Our mood series extracts the latent dimension of different survey questions and neutralizes the bias often produced by analysing single survey questions. To implement our ‘European integration mood’, we collected survey marginals of thirty survey questions asked at least twice between 1992 and 2016.Footnote 12 We collected questions from the Eurobarometer, the European Social Survey, the European Election Studies, the European Values Survey and the Transatlantic Trends, for a total of around 600 survey marginals in each country.

Methods

Thanks to our data collection we obtained six time series of party positions and six time series of parties’ issue salience where the temporal unit is the semester. In order to decide how to best model our time series, we analysed their properties by means of unit root tests with two multiple bootstrapping testing methods: the sequential testing procedure (Smeekes, Reference Smeekes2015) and the false discovery rate controlling approach (Moon & Perron, Reference Moon and Perron2012; Romano et al., Reference Romano, Shaikh and Wolf2008) (see Table B1 in the Online Appendix). These tests suggest that the public opinion series and the position series all contain a unit root. There is some evidence that the salience series might be non‐stationary as well. However, when we employ the Kwiatkowski‐Phillips‐Schmidt‐Shin (KPSS) test, which has a null hypothesis of stationarity, we cannot reject the possibility that the salience series is indeed stationary. Below we present a model where the salience series is differenced, but we replicate all analyses with the salience in levels in the online Appendix.

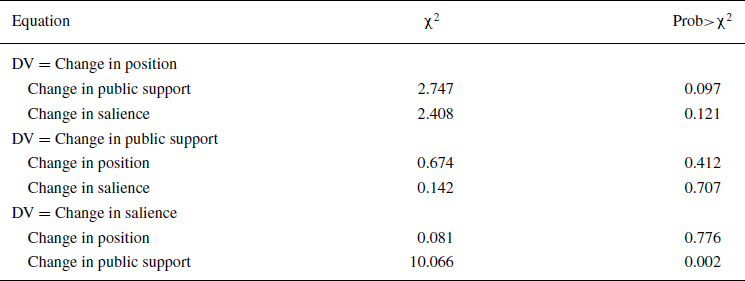

Next, we address the potential endogeneity of public opinion, party positions and issue emphasis, by presenting Granger causality tests based on panel vector autoregression (PVAR) models. PVAR models allow us to simultaneously estimate the relationship between our three variable interests by treating them as endogenous and interdependent. We also include some exogenous variables as controls (the same that we use in the main models presented below). Based on these models, we test whether we can reject the null hypothesis that each variable does not Granger‐cause the other. According to the results in Table 2, we can reject the hypothesis that public opinion does not affect party positions and issue salience. At the same time, we cannot reject the hypotheses that public opinion is not affected by party positions or issue salience, or the hypotheses that party position and issue salience do not influence each other. These results imply that we can model the effect of public opinion on party positions and issue salience without reverting to simultaneous equations to account for reverse causality.

Table 2. Panel Granger causality tests

Note: Tests based on the PVAR model A2 in Table C1 in the online Appendix.

Abbreviations: PVAR, panel vector autoregression.

Given these results, we decided to model our data via auto‐distributed lag models. First, we model whether current and previous changes in public opinion affect current changes in party positions, controlling for previous changes in party positions. Second, we model whether current and previous changes in public opinion affect current levels of issue salience, controlling for previous levels of salience. Next to these baseline models, we present models that control for a number of important variables. First, as parties in government might be more likely to adopt pro‐EU positions and might be more likely to discuss EU issues (Williams & Spoon, Reference Williams and Spoon2015), we control for government status, measured as a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 for the semester when the party is in office and 0 otherwise. We further include some dummy variables for national and European elections, and for political events that marked an integration step, such as the signing of EU treaties or EU referendums (see Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). Finally, we control for the current and previous presence of radical right parties in the political discourse in Europe, measured as the number of hand‐coded newswires where these parties talk about EU issues in each semester. This is an important control as some have argued that mainstream parties might respond more to the rise of Eurosceptic parties rather than to public opinion (Meijers, Reference Meijers2017). We also interact the presence of the radical right with a dummy that distinguishes whether the mainstream party under study is a left‐wing or a right‐wing party because of the different incentives for accommodation (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005). In the online Appendix, we present additional models that control for government popularity and its interaction with government status of the party, and for changes in the economic sentiment indicator. Governing parties might be more likely to talk about EU issues to hide a negative performance (De Vries & Solaz, Reference De Vries and Solaz2019).

Empirical analyses

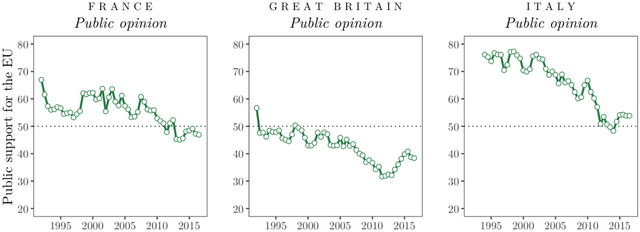

This paper investigates whether mainstream parties respond to shifts in public opinion on European integration, by altering their position on the EU and the salience they attach to it. Our data confirm that public support for European integration has declined in all the three cases under study, although with different timings (see Figure 1). The British electorate has historically exhibited a higher scepticism towards the benefits of EU membership. After a drop following 1992 and then a period of relative stability in the early nineties, a downward trend started at the turn of the century and accelerated from 2005 to 2012, after the failure of the Constitutional Treaty and during the economic crisis. Since then, public support for European integration has increased again, even though it remains lower than in the other two countries. France, in contrast, shows higher levels of support. After an initial drop at the time of the referendum on the Maastricht Treaty, support for integration increased again by the end of the nineties, only to collapse during the financial and the migration crises. The history of the Italian public is one of great support until the mid‐2000s. The double‐dip economic and financial crises that paralyzed the European economy definitely undermined the already declining confidence of Italian citizens in the institutions of the EU. However, in spite of this sharp decrease in support for European integration, the Italian public remains for the most part quite favourable to the integration project.

Figure 1. Public support for European integration.

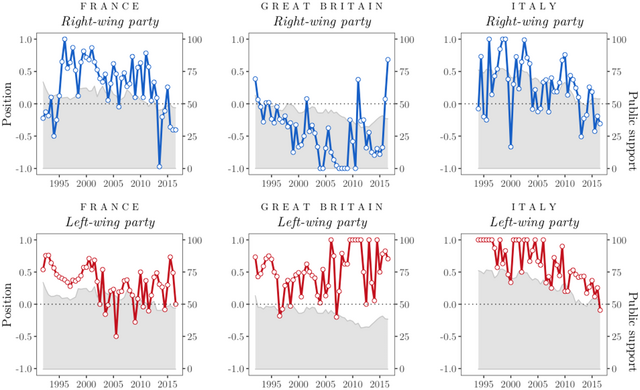

How have mainstream parties responded to such declining support for the EU? In terms of position (Figure 2), out of the six parties under study, only the British Conservatives hold a Eurosceptic stance over time. After John Major's moderate positions, the party took a clear Eurosceptic turn during the 13 years of opposition (1997–2010). The election of David Cameron, first as secretary and then as Prime Minister, meant a return to more moderate positions. On the contrary, the Labour party shows a pro‐EU stance overall, especially during the opposition years. Quite surprisingly, Tony Blair's years were characterized both by moderate pro‐EU positions and significant variations once he arrived in government. This illustrates the ambivalence of the New Labour towards the Union, as the European commitment of the party was often trumped by electoral considerations (Schneider, Reference Schneider2019, pp. 174–181). In France, both mainstream parties hold similar pro‐EU positions characterized by an overall downward trend. This could be partly explained by the divisions inside the parties. For example, the division of the Socialist Party during the campaign for the referendum on the Constitutional Treaty in 2005 translated into its strongest Eurosceptic point over the whole period under study. While mostly pro‐EU until 2004–2006, both parties show some variation in their EU positions during the economic crisis. As for the right, it started as a Eurosceptic party in the years following the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty, before shifting to a pro‐European position. It, then, took again an anti‐EU turn in 2014, during the migration crisis. The Italian left is the most pro‐European party under study. It holds favourable views of European integration over the whole period, especially during the first half (from 1994 to 2006). From 2006 onwards, its pro‐EU position weakened during the Eurozone crisis and then the migration crisis, although the party remains overall supportive. The Italian right demonstrates more ambivalence towards the EU. Despite some sharp anti‐EU peaks in 1995 and 2000, the Italian right exhibited pro‐European positions from 1994 to 2004, and again during most of the economic crisis, before an important drop at the end of the period under study.

Figure 2. Mainstream parties’ positions on European integration. The lines show the average party position in each semester (left‐wing axis). The shaded area shows public support for European integration (right‐wing axis).

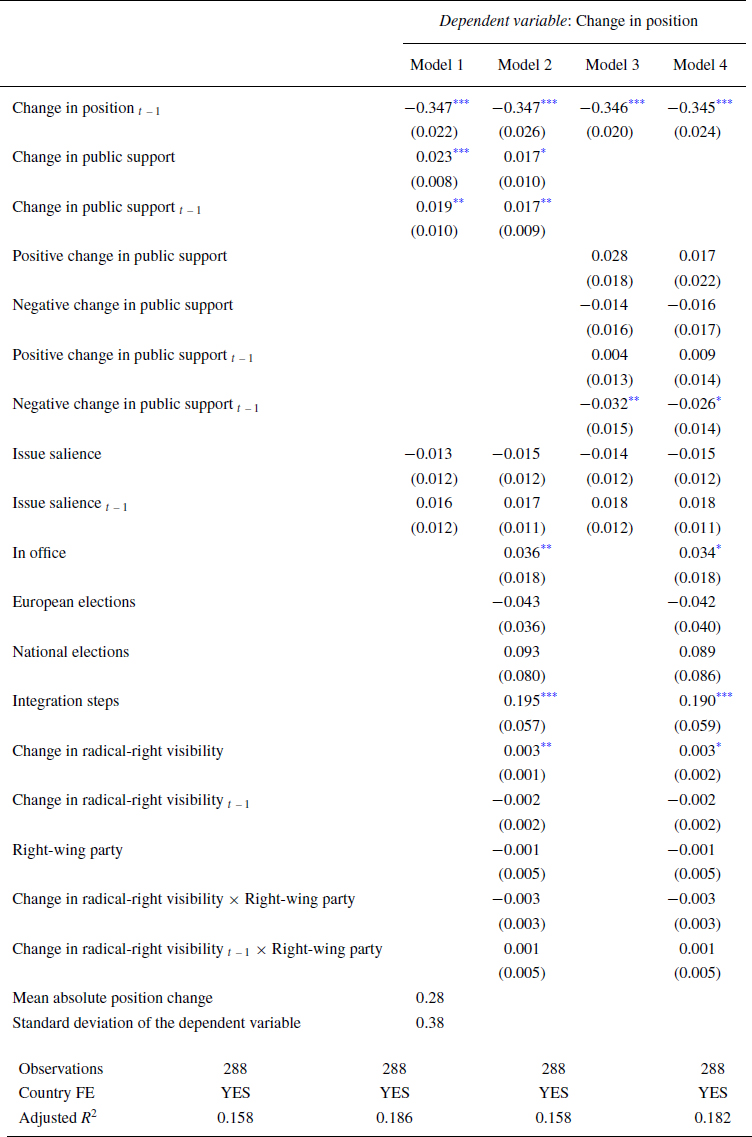

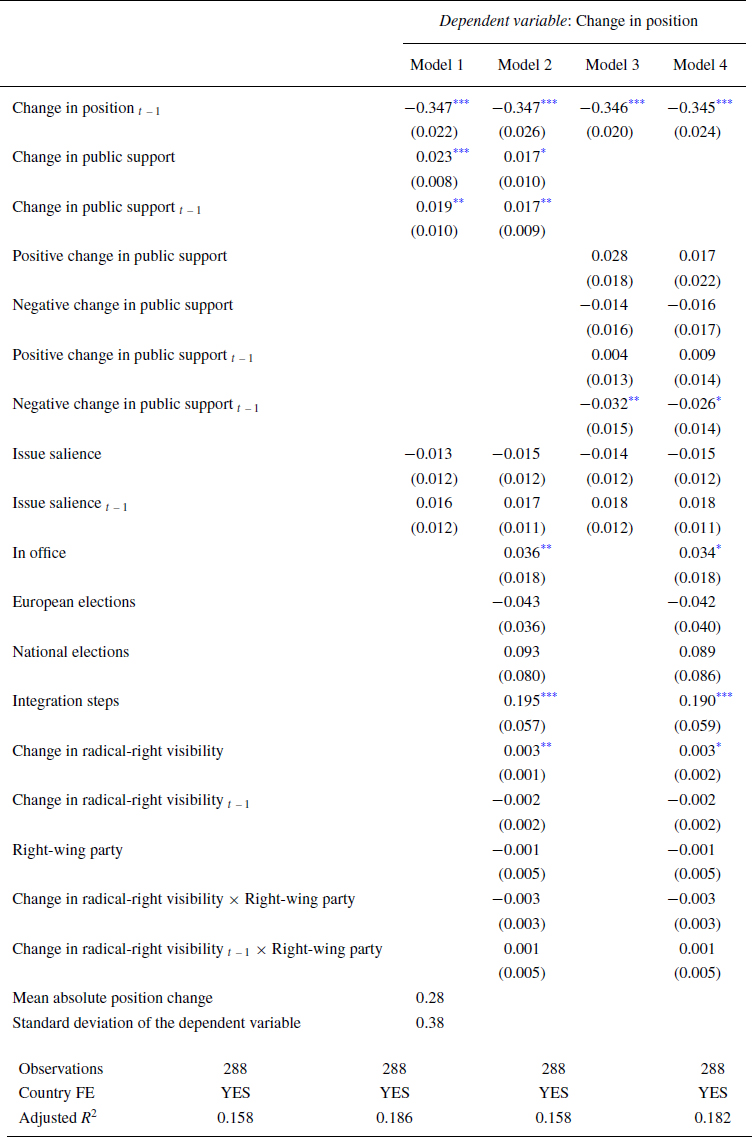

The models in Table 3 analyse the effect of public opinion on mainstream parties’ positions on European integration. Models 1 and 2 show that mainstream parties adjust their EU positions in line with previous and current changes in public opinion. A one‐point increase in support for the EU makes parties more supportive by 0.02 points. This represents roughly two‐thirds of the mean absolute change in party position (about half of a standard deviation). Models 3 and 4 further investigate what type of public movements parties are more likely to respond to. The results clearly show that mainstream parties tend to respond to Eurosceptic changes in public sentiment. This confirms that parties respond to public opinion out of fear of electoral repercussions. When the median voter moves closer to the party's position, adjusting the positions in the same direction would get the party closer to its ideal policy stance but away from the public's. Such policy‐seeking behaviour would not increase representation (Wolkenstein & Wratil, Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2021). Instead, if vote‐seeking motivations predominate, as in the case of mainstream parties, a party is expected to move towards the median voter when the latter moves away from the party position (Ferland, Reference Ferland2020).

Table 3. The effect of public opinion on party positions

Note: Standard error in parentheses clustered at the party level. The unit of analysis is a party's position in a semester.

Abbreviations: EE, fixed effects.

* p < 0.1;

** p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.01.

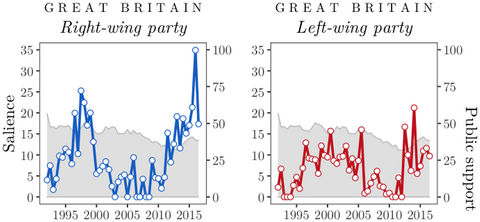

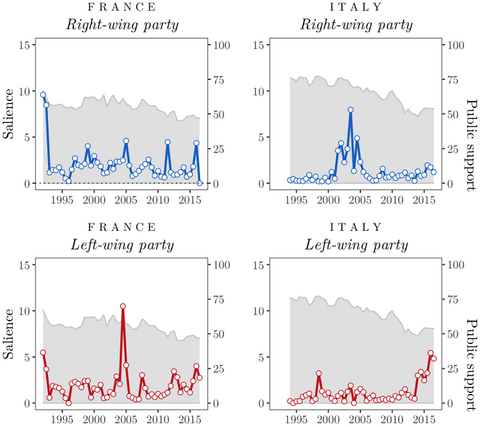

We have argued that parties can respond to changes in public support for European integration not only by changing their positions but also by altering the salience they attach to the issue. The three countries under study show significant variation with regard to the overall salience of EU issues in the public debate (see Figures 3 and 4). Our data confirm the high salience of EU issues in the British debate, with a steady increase in the years preceding the Brexit referendum. European integration also gained salience during the early years of the New Labour government. On the contrary, the salience of European integration in France and Italy is rather low and follows a pattern of intermittent politicization (Hutter et al., Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016). In France, the two referendums held in 1992 and 2005 significantly increased the salience of EU issues in the public debate, on both sides, although the right especially emphasized the EU at the time of the Maastricht referendum, while the left increased the salience of the EU more when the referendum on the Constitutional Treaty took place. Similarly, in Italy, EU issues became prominently covered in the political debate during the treaty negotiations that preceded the signing of the Constitutional Treaty. In all the three countries, we observe an increase in the salience of European integration during the recent financial crisis that put at risk the survival of the monetary union.

Figure 3. Mainstream parties’ emphasis on European integration (United Kingdom). The lines show the average party salience in each semester (left‐wing axis). The shaded area shows public support for European integration (right‐wing axis).

Figure 4. Mainstream parties’ emphasis on European integration (Italy and France). The lines show the average party salience in each semester (left‐wing axis). The shaded area shows public support for European integration (right‐wing axis).

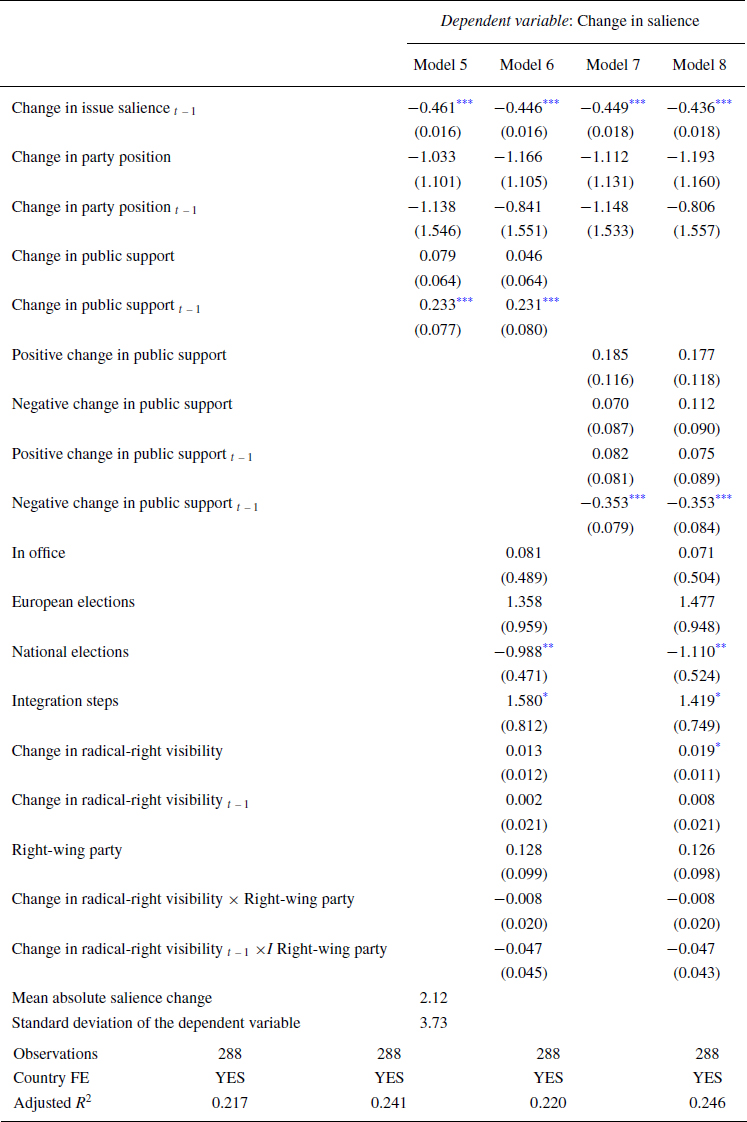

How did changes in public opinion affect the salience of EU issues in mainstream parties’ discourse? Models 5 and 6 in Table 4 provide evidence that mainstream parties have changed the salience they attach to EU issues in line with changes in public opinion. They deemphasized European integration when the public grew Eurosceptic and emphasized it when it occasionally became more supportive. We can calculate the effect size as a percentage of the average salience. The effect is equal to 11 per cent of the mean absolute salience change. Again, we can test whether mainstream parties are more likely to change the salience of EU issues in response to positive or negative changes in public support for the EU. Models 7 and 8 show that mainstream parties typically deemphasize EU issues when the public has previously become more Eurosceptic. The decrease in salience is equal to 17 per cent of the mean absolute salience change. We only find some evidence that parties increase the salience of EU issues when the public becomes more Europhile if we model the salience series in levels (see models A11 and A12 in Table D3 in the online Appendix).

Table 4. The effect of public opinion on parties’ issue salience

Note: Standard error in parentheses clustered at the party level. The unit of analysis is a party's EU issue salience in a semester.

Abbreviations: EE, fixed effects.

* p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

We have found evidence that parties respond to public opinion on European integration by adapting their policy positions. At the same time, we have found that parties have deemphasized EU issues as the public became predominantly more Eurosceptic. This raises the question of whether parties have signalled their responsiveness to voters: Have parties emphasized Europe in their discourse when they adapted their positions to the tides of public opinion? To answer this question, we constructed a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 in those semesters when parties were positionally responsive and 0 otherwise. We then interacted with this dummy variable with our public opinion series. The models presented in Table 5 are, therefore, the same as those presented in Table 4, with the additional inclusion of such an interaction.

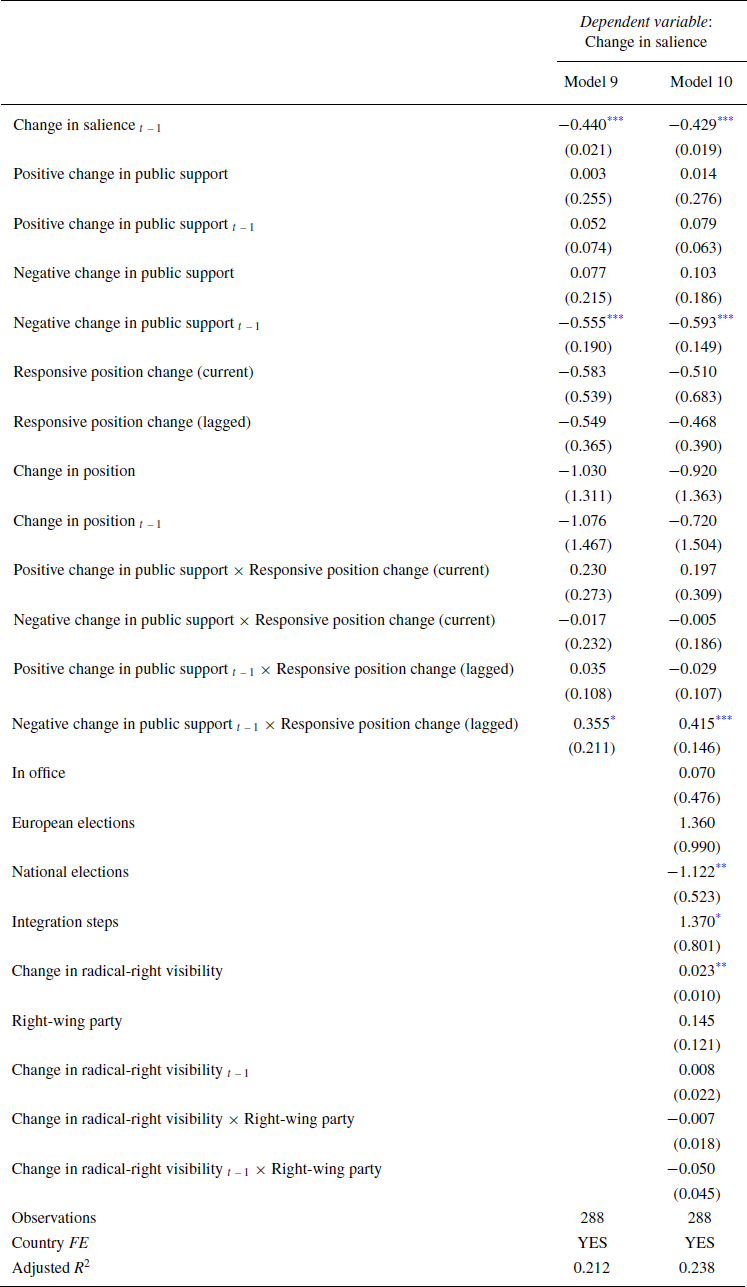

Table 5. The effect of public opinion on issue salience conditional on positional responsiveness

Note: Standard error in parentheses clustered at the party level. The unit of analysis is a party's EU issue salience in a semester.

Abbreviation: EE, fixed effects.

* p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

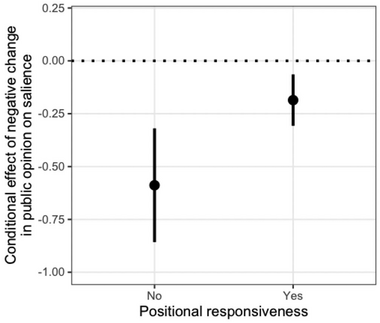

The results in Table 5 reveal an interesting pattern. Models 9 and 10 show a significant interaction effect between previous negative changes in public opinion and the dummy variable that indicates the ‘responsive’ semesters. This means that parties do talk more when they are positionally responsive to previous increases in Euroscepticism compared to when they are not. However, if we take into account the strong negative effect of those increases in public Euroscepticism, the total effect on issue salience remains clearly negative (see Figure 5).Footnote 13 When public Euroscepticism increases, mainstream parties deemphasize EU issues even when they are positionally responsive to public opinion, just a bit less compared to when they are not responsive. Mainstream parties do not only hide their unresponsiveness to public opinion but also their responsiveness.

Figure 5. The effect of negative changes in public support on parties’ issue salience is conditional on positional responsiveness. A graph based on Model A16 is in Table D5 in the online Appendix. The model additionally controls for the economic sentiment indicator and government approval interacted with government status.

Conclusion

How do mainstream parties respond to the increasing Euroscepticism of their electorates? Does party discourse on European integration respond to public opinion? We have argued that to answer these questions, we need to take into account both the positions that parties take on an issue and the emphasis they attach to it. Our results show that, in the period under study, mainstream parties have adapted their positions to the tides of public opinion. These results confirm the existence of an ‘electoral connection’ (Carrubba, Reference Carrubba2001) also between elections and provide additional evidence of a bottom‐up process in mass‐elite linkages on European integration (Steenbergen et al., Reference Steenbergen, Edwards and de Vries2007). Our findings also show that the decreasing support of mainstream parties for the European project is not just the result of the success of Eurosceptic parties (Meijers, Reference Meijers2017) but also a direct effect of changes in public support. At the same time, we also found evidence that mainstream parties have responded to the increasing Euroscepticism of their electorate by changing the salience of their political discourse on Europe in line with previous studies (De Sio et al., Reference De Sio, Franklin and Weber2016; Steenbergen & Scott, Reference Steenbergen and Scott2004). They emphasized EU issues more when the public became occasionally more supportive and deemphasized them as the public grew Eurosceptic. In contrast with the previous literature, we find that these strategies of position changes and salience changes occur dynamically semester after semester. Most importantly, we find evidence of both strategies while taking them into account at the same time – either in a vector autoregression model or as control in separate models. This is an important step in bridging salience and positional theories of party competition (Basu, Reference Basu2020; De Sio & Weber, Reference De Sio and Weber2014; Wagner, Reference Wagner2012).

Before an increasing Eurosceptic public, did mainstream parties at least emphasize EU issues when they adapted their positions to follow the public sentiment? We did not find evidence that mainstream parties signalled their responsiveness to voters. Although they talked more about European integration when they were responsive than when they were not, they still predominantly tried to silence the issue as the public grew Eurosceptic. The fact that mainstream parties decided to silence their positions even when they were responsive to the median voter, confirms the difficulty to deal with an issue that cross‐cuts the traditional alignment of party competition and that has the potential to divide, internally, parties and their electorates. Of course, the limited salience mainstream parties decided to accord to European integration might be in line with the little importance voters attach to the issue. However, our findings suggest that conceiving of democratic responsiveness only in terms of positional adjustment may give a very partial view. Pushed to respond to an increasingly Eurosceptic public, parties have softened their support for the EU and have occasionally taken more sceptical stances. Yet, they have not communicated nor justified their policy shifts to voters. From a normative perspective, such a type of responsiveness may corrode the representation process and may boost feelings of discontent. These results could help explain one of the main puzzles in the literature on party responsiveness to public opinion, namely the fact that while parties have been found to follow the opinions of their electorates, voters did not seem to notice such shifts (Adams, Reference Adams2012). In this regard, the paper also contributes to our understanding of the multiple strategies that parties can deploy to hide their positions on issues that they struggle to deal with (Han, Reference Han2020; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Hagemann and Hobolt2021; Koedam, Reference Koedam2021; Rovny, Reference Rovny2012). Future studies could test whether the strategy of ‘silent responsiveness’ we have identified also applies to mainstream party discourse on other wedge issues such as, for example, immigration. Moreover, and in line with previous studies (Basu, Reference Basu2020), more research could uncover how non‐mainstream parties mix positional responsiveness and issue emphasis, and test the generalizability of the four scenarios we have delineated.

Taken together, these findings also have important implications for theories of European integration. On the one hand, the evidence on parties’ positional responsiveness confirms one core assumption of post‐functionalist theories of European integration, namely that public dissent has come to exert a constraining effect on mainstream party elites (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). On the other hand, our results seem to vindicate new inter‐governmentalist explanations. Mainstream parties’ salience strategies seem to have provided a useful tool to circumvent the public dissent in a period of intensified cooperation at the EU level (Hodson & Puetter, Reference Hodson and Puetter2019). This could have let mainstream parties maintain some room for manoeuvre at the European level. Yet, a clear consequence of the strategy of ‘silent responsiveness’ is to have left the public debate to the rhetoric of Eurosceptic political entrepreneurs. Given the importance of domestic discourse for the legitimacy of EU institutions, this is likely to have only deepened the crisis of the European project.

Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to thank Elias Dinas, Sarah Engler, Peter Enns, Sara Hobolt, Jelle Koedam, Hanspeter Kriesi, Jon Slapin, Jim Stimson, Laura Stoker, Stefanie Walter and Théoda Woeffray for their very helpful feedback. This work was supported by the European Research Council: project no. 338875 (POLCON) and project no. 817582 (DISINTEGRATION).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

A. Data collection

B. Unit root and stationarity tests

C. Panel Vector Autoregression models and Granger causality tests

D. Robustness tests

Supporting DATA