Introduction

While it is beyond the scope of this article to review all the evidence supporting the relative benefits of selecting an LAI formulation instead of its antipsychotic counterpart, I will present a study published a few years ago in Schizophrenia ResearchReference Taipale, Mittendorfer-Rutz and Alexanderson 1 to make a point that even strong evidence that LAIs are associated with major outcome benefits compared to the very same oral antipsychotic will languish and for the most part remain ignored and unknown among practitioners and mental health advocates. The authors used the Swedish national health database whose data cover the entire population of Sweden and took a close look at the subpopulation of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. They were able to link mortality data with very granular antipsychotic prescription data at an individual patient level between 2006 and 2013. This made it possible to link exposure times for specific antipsychotic medications prescribed to the risk of death during the prescription interval. These data allowed researchers to compare relative mortality risk for specific antipsychotics that were available as either an oral tablet or an LAI injection.

The results were stunning. Being on LAIs reduced mortality by one-third compared to the oral version of the same medication. Every individual oral/LAI comparison showed a lower death rate associated with LAI exposure, but taken individually, these differences in mortality were not significant. But, when all individual oral/LAI pairs were aggregated into two groups based on oral vs LAI status, then “LAIs … were associated with 33% lower mortality than equivalent orals.” Equally stunning, at least to me, was the lack of interest in this finding after publication. Think about what that means when a publication shows a treatment that might lower morality by one-third with medications available today that are the same moiety as their oral counterparts. One might be tempted to invoke the uncertainty of any specific study as an explanation for the inertia despite such evidence. But I believe that there are other factors at play that, if true, would provide an explanation for the snail’s pace of change. On some level, I believe many patients and providers are afraid of what will happen to their treatment relationship and what might happen to the therapeutic relationship. This fear can then be traced to unrealistic expectations concerning medication adherence as a requirement for a good working alliance. As covered below, this paper will get into the evidence supporting this theory. Before turning to LAIs, let us discuss the vital role of accurate treatment information to achieve best outcomes, and the extent to which missing or misleading information is a major impediment to achieving recovery goals.

The problem of poor information

Many of the hypotheses that follow have to do with missing information or misinformation as being a major barrier limiting outcomes in schizophrenia. Remember that the nature of schizophrenia makes it unlikely that the initial medication regimen addresses all symptoms and has no side effects. Instead, over the course of the illness, patients will try different medications, and the outcomes from these experiences provide an individualized information platform that can be used for subsequent treatment decisions. Likewise, another information platform is developed based on behavioral patterns exhibited in the person’s coping styles, including complications like rejecting medications or continued use of substances that attenuate efficacy of prescribed medications. Knowledge gained about the individual will evolve and grow over time. If known and communicated, this knowledge can be used to inform current and future medication recommendations. Invoking Bayes theorem to justify using a priori information to improve probability of favorable outcome is a technical way of saying that our future treatment results depend in large part on what is learned from past treatment outcomes. The ideal scenario is to have a comprehensive information base covering the treatment history, including dosage, duration, response, and tolerability, along with information on complicating behavioral factors such as medication adherence. The latter information is incredibly valuable when assessing whether the poor response is from inherent efficacy limitations of the medication or is better explained by other factors such as undisclosed nonadherence. The problem is that within the context of US treatment services, this kind of information is rarely accessible. It is lost, incomplete, or scattered, making it unusable for future treatment planning. The clinician or team will usually have a medication plan that is deemed acceptable and tends to be the automatic “go to” medication choice. This is understandable but limits the opportunities to choose therapies based on prior learnings for that individual patient. When this keeps happening again and again with the same patient, it feels like watching the movie Ground Hog Day, where the character wakes up on the same day over and over.

What is holding back LAIs to be default treatment approach for schizophrenia?

As LAI options and formulations have advanced, it becomes much easier to place LAIs as the default way to treat schizophrenia, especially when it is an option instead of the oral counterpart. This shift in making the LAI the default has not happened, and this section will present hypotheses that may explain some of the headwinds in LAI adaptation.

Hypothesis 1: Complacency about lack of information

Missing or fragmented information about treatment history is the rule not the exception when treating schizophrenia. Starting medication without prior knowledge despite years of prior treatments is a status quo practice, resulting in lost opportunities to have the knowledge base needed to help guide strategic medication decisions. Busy clinicians will lean toward choosing among a handful of default oral antipsychotic options and leaving it at that. On a day-to-day workload basis, there is little incentive to lean into embracing the information advantages from changing the default formulation from the routine use of oral to the routine use of its LAI counterpart. This is one of many examples of the lost opportunities to use prior information to inform current and future medication recommendations.

While missing information is bad enough, misinformation is even worse. Misinformation is defined in the context of this discussion to be the result of a decision on the patients’ withholding key information (usually nonadherence) between what was prescribed and what was actually taken. The clinical team then acts on the incorrect assumption that the medication was taken as prescribed and use this misinformation to guide treatment recommendations. Using an analogy of driving to a new location with your phone’s GPS illustrates the difference. A GPS that stops working because of a dead battery is annoying but not misleading. A GPS program that looks like it is working but has programming errors that send you in the wrong direction is misleading. Misinformation leads to poor decisions; applied to treatment of schizophrenia, it can result in choosing the wrong medication or wrong dose. Unfortunately, there are strong incentives for both patients and clinicians to interact in ways that perpetuates misinformation, which is covered in detail in Hypothesis 3.

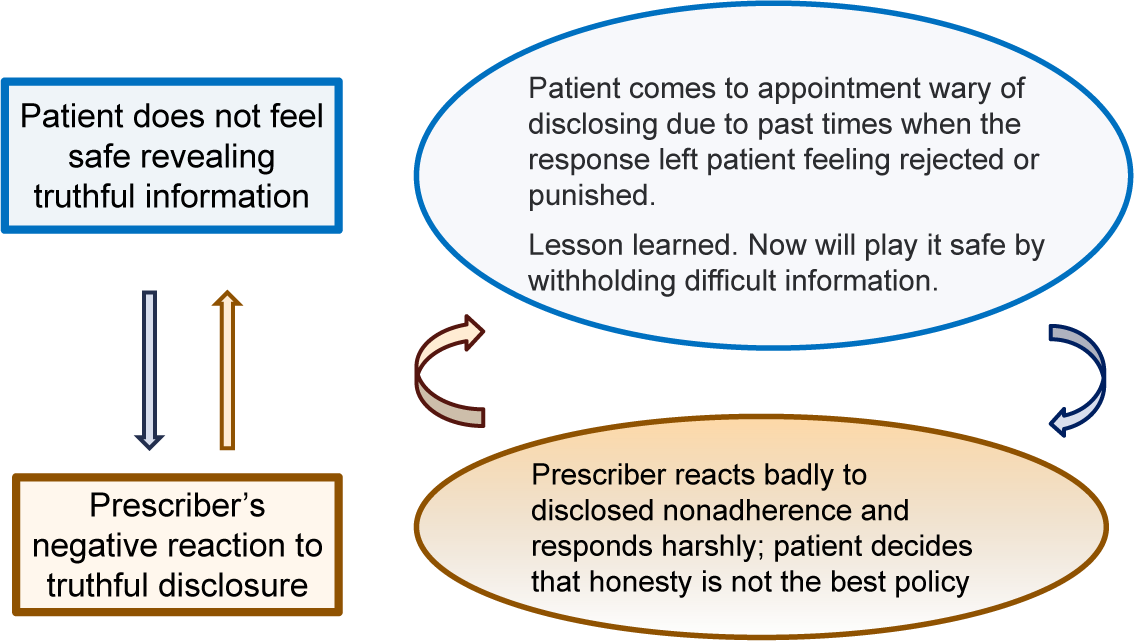

Hypothesis 2: LAIs are oversold as adherence interventions

For generations of clinicians, the primary reason to use LAIs over oral antipsychotic was as an adherence intervention.Reference Herz, Liberman and Lieberman 2 Since then, the concept of uses of LAIs has broadened,Reference Keepers, Fochtmann and Anzia 3 but many practitioners still hold on to the older concept of reserving LAIs to patients identified as nonadherent to oral therapies. In fact, even now, many educational programs on LAIs continue to highlight their potential as adherence interventions. For example, an excellent CME overview published in the 2024 discussed LAIs as follows; “Given the high frequency of nonadherence in schizophrenia… long-acting injectables have obvious advantages for long-term treatment …”.Reference Leucht, Priller and Davis 4 Such a statement can be understood as saying that LAI’s benefits come straight from better adherence, an assumption that oversells LAIs as adherence “fixes.” Clinicians who are not very experienced in LAI might interpret these statements that LAIs will solve adherence problems for patients who do not accept (oral) medication. The reality is very different. As shown in clinical insert #1, overselling LAIs at the front end of training may lead to abandoning LAIs out of disappointment. Figure 1 provides an alternative visual model that emphasizes information advantages of LAIs. I believe that this model is more realistic and clinically useful. Understanding LAIs as superior to oral as an information platform is more accurate and makes it easier to match the objective of starting an LAI to the specifics of the individual patient. As implied by Figure 1, LAIs are always better than oral medications on quality of information but only sometimes improve adherence.

Figure 1. Advantages of LAI: information versus adherence.

Case vignette 1: LAIs are more likely to succeed as information platforms

Case history: An acute inpatient unit decided to initiate LAIs before discharge for their “revolving door” patients in the hopes of lowering 1-month readmission rates. After staff training, the first patient started on an LAI before discharge was someone well-known to staff due to multiple readmissions. He accepted his first LAI a day before discharge and was scheduled for his second LAI to be given at the time of his outpatient appointment 4 weeks later. He did come for his outpatient intake and but did not receive his second injection and then was lost to follow-up until coming back to the inpatient unit.

Was the LAI a success or failure? If the expectation was that he’d stay on his LAI long-term, then the LAI intervention was a failure. If expectation was to use LAIs to help transition to outpatient care while getting him started on a new treatment approach, then the LAI intervention was a success.

Hypothesis 3: Fear of disclosure causes and perpetuates misinformation

Everyone Lies Greg House from TV Series House, MD.Reference Summerfield 5

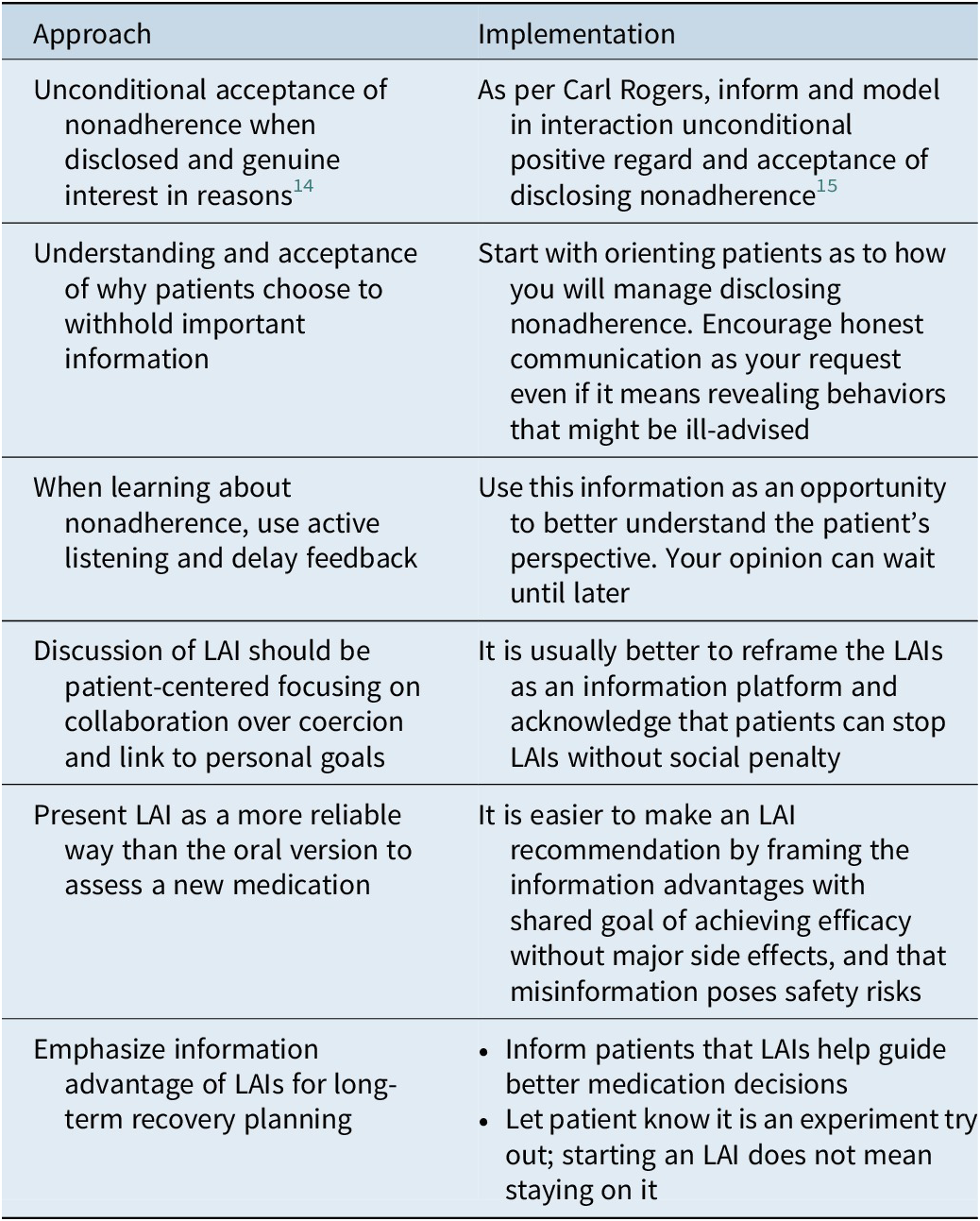

Why do patients lie about their adherence? In the long run, it is not in their own best interest given the likelihood that misinformation might jeopardize the effectiveness of subsequent treatments. When phrased this way, one answer is that most patients are not thinking about how this may impact their future treatment plan. It is much more likely that “withholding” or “lying” is based on social norms that are in play with the clinical team. Disclosing nonadherence risks disapproval or worse. This issue was hard to find in research literature specific to schizophrenia disease states but can be found for other disease areas. One study found that patients often failed to disclose the reality of what they were taking primarily because of the desire for social approval (being seen as a “good patient”) or the fear of social consequences (eg perceived or actual rejection or social disapprovals).Reference Tugenberg, Ware and Wyatt 6 Given the challenging life circumstances among people with schizophrenia, it would seem likely that the social penalties of disclosing information that might annoy their clinicians would on average be greater than medical conditions. Based on my clinical research in this area, many patients with schizophrenia have learned the hard way that nothing good comes from truthful disclosure of unwelcome information such as nonadherenceReference McCabe and Priebe 7 –Reference McCabe, Healey and Priebe 9. Also, the same qualitative research found that a common response of well-meaning clinicians when first learning of nonadherence from their patient is to immediately go into reciting reasons why stopping medication is a bad idea. Unfortunately, this response preempts the opportunity to actively listen to the patient to better understand the patients’ perspectives on medication. Although well-meaning, going into lecture mode will likely be experienced as the clinician being out of touch with what matters to the person. Figure 2 is a visual depiction of how these interactions can devolve and exacerbate the disclosure problem as the discussion is unpleasant to all. The quick fix is for the patient to withhold the truth and for the clinician to turn a blind eye to what is really happening. Accurate information is sacrificed and eventually the patient pays the price of misinformation that compromises future medication decisions.

Figure 2. How clinical interactions lead to misinformation.

Putting these together

The above hypotheses, taken together, may help explain some of the reluctance to adapt LAIs in routine practice. Patients who decide to stop antipsychotic medication do not want to be lectured, scolded, or ignored from honest disclosure of their decision. Instead, they hope that just this time they can keep it all under wraps, and maybe, this time they will be fine without medication. It follows that the desire to bury honest disclosure is the main reason to reject LAIs out of hand. The same reluctance in LAI use might be more likely for clinicians who do not want to deal with nonadherence or would rather not know about the extent to which undetected nonadherence is happening on their clinical caseload. If true, it may feel self-righteous to criticize these clinicians for their passivity. But there is another side to this story. Some educational programs on LAIs can seem to come down harshly on practitioners who avoid LAIs. In my opinion, a better strategy is to detoxify the topic of adherence and to teach practitioners more effective ways to work with their patients on these issues without poisoning the topic or the therapeutic relationship. It is my belief that paying attention to these issues will help move the field to accept LAIs as the default approach instead of orals. Implementation of LAIs would likely come after—not before—we change the way we work with our patients on their adherence concerns within the broader framework of nurturing the therapeutic relationships.Reference Hassan, McCabe and Priebe 10 Continuing with the status quo will fail as the status quo perpetuates these dysfunctional interactions between patient and clinician. The next section proposes three action items for consideration as action items for the field.

Action item 1: Focus more on the need for accurate information

Many clinicians have become so accustomed to missing and misinformation that they forget about the potential to improve outcomes. It seems to me that the field has not adequately identified this as a key target for quality improvement. Admittedly this topic might not be as exciting as discussing new medications and new mechanisms. But the tedious task of accurate information is a foundation forgetting best outcomes with our medications. In context, it seems to me that information platforms are even more important than ever as new therapies become available. Emphasizing the need to support accurate information platforms is a natural starting point for discussing the use of LAIs. In fact, it seems to me that the argument for routine use of LAIs is, in many ways, part of the broader need to improve access and accuracy of treatment information for any person facing a long journey of recovery from schizophrenia.Reference Adeniyi, Arowoogun, Chidi, Okolo and Babawarun 11 It seems that the barriers to accessing medical records on digital platforms such as EPIC can be modified for persistent severe psychiatric disorders.Reference Tapuria, Porat, Kalra, Dsouza, Sun and Curcin 12 LAIs are an important tool in such efforts, but their use will be more effective with coordinated efforts to improve other methods to support information platforms. Shifting the spotlight away from adherence benefits to the broader case of supporting better information platforms makes it easier to make the case for LAI versions to take first position before their oral counterparts.

Action item 2: Change interactions in ways that remove incentives to lie

LAIs will never become mainstream as long as patients remain incentivized to lie and clinicians remain stuck in taking nonadherence personally. Whatever you call it—lying, withholding, nondisclosure—absolutely needs to be de-toxified in a way that patients will feel free to openly disclose nonadherence without having worry about the consequences of honesty. Clinicians need to better understand the immediate and lasting damage that come from reacting to nonadherence in a way that puts distance between the patient and the clinical team.Reference Weiden 13 , Reference Weiden 14 Instead of reacting with irritation or going into pedantic lecture mode, it is much better to make this a point of discussion where the clinician learns from the patient more about the experience and show gratitude that the patient felt safe enough to take the emotional risk of disclosing such information. Insert 2 presents a dramatic example of what can happen when the clinician inadvertently gave a patient a strong incentive to lie about adherence after it happened.

Insert 2: How relationships matter when using or eschewing LAIs

Feedback on why LAIs would threaten a therapeutic relationship

After a talk on LAIs given in a weekly PGY3 psychopharmacology course, a resident told me of a major concern she had with LAIs and why she did not use them in her medication clinic. She admired the work of Carl Rogers and the principles of client-centered therapy, which is based on what Rogers called “unconditional positive regard” for all patients. She felt that the principle of unconditional positive included showing trust and this trust included being able to truthfully inform her of any problems, including going off medications. Her perspective was that offering LAIs would be a signal to her patients that she did not trust regarding medication management issues or disclosing adherence problems.

Follow-up on a relapsing patient

A few months later, she told me about one of her cases that helped her re-evaluate her concept of trust. One of her schizophrenia outpatients was admitted with acute psychotic symptoms and eventually told the inpatient team that he had stopped his medication a few months back. This happened after experiencing sexual side effects. He planned to tell his doctor but held back and then avoided it completely so he would not “hurt her feelings.” He asked the inpatient resident to tell her what happened and hoped that she would continue to see him even though he was a “bad patient.”

Lessons learned

In many ways, this resident was to be commended for her dedication and willingness to learn. It seemed to that in hindsight, the failure to report stopping medication was not due to the therapeutic relationship directly but rather the undue focus on “trust” as a requisite for a positive therapeutic relationship. Although she set criteria for herself (eg no LAIs), the focus on “trust” made it harder for the patient to disclose stopping medication in a timely manner. At first, he did not feel comfortable disclosing sexual side effects. But after he hesitated, it was worry about “trust” that was the main cause of remaining silent about going off his medication.

Action item 3: Focus on LAIs as superior information platforms

As stated above, if most of the benefits favoring LAIs can be linked to information advantages, would it not make more sense to present the use case for LAIs this way. Current practice often leaves clinicians searching for ways to recommend LAIs, and they frequently “choke.” Unlike the 2007 APA guidelines for treatment of schizophrenia that emphasized LAIs for adherence, the 2020 APA treatment guidelines broaden the use case to other possible benefits that go well beyond adherence to include using LAIs as a preferred method to determine true pharmacologic treatment-resistance from other causes of persistent symptoms. An LAI trial, if accepted, eliminates the risk of misinformation of undetected poor adherence to oral medication, making the LAI trial a safer way to accurately recommend clozapine. It seems this rationale for clozapine selection can generalize to many other situations, and it shifts the LAI discussion away from “we are recommending this LAI to help your adherence” to “we are recommending an LAI to give us much better information about what medication might be best for you.” Table 1 summarizes some approaches to detoxifying adherence discussions to make them much more collaborative than what is often practiced today.

Table 1. Achieving psychological safety in adherence or LAI discussions

Summary

This article attempts to address why LAIs continue to be a second thought while oral formulations continue to be the default approach to treat schizophrenia. The argument that not all orals are available as LAIs, while true, cannot explain why LAI use still lags behind orals when both are available.

The first is the misconception that the main use of LAIs is to improve medication adherence. This overplays LAIs as some kind of automatic adherence fix. It misses the broader concept that when LAIs do improve adherence, it is often by providing better information than would be possible with orals. The second issue covered is the damage done by misinformation that comes from withholding information about nonadherence.Reference McCabe, Heath, Burns and Priebe 16 –Reference Priebe, Richardson, Cooney, Adedeji and McCabe 18 The root cause for misinformation is that patients prioritize the therapeutic relationship and want to avoid the possible consequences of being a “bad patient.” Clinicians may also tacitly accept nondisclosure to avoid dealing with being blindsided by this information. In doing so, both patients and providers interact in ways that show that being seen as a “good patient” is a priority.Reference Quirk, Chaplin, Hamilton, Lelliott and Seale 19 , Reference Stavropoulou 20 Left on the back burner is the fallout of misinformation that jeopardizes future outcomes.

The answer to these barriers is easier once identified. Better education on how information can help or harm outcomes is needed, as is training on how the therapeutic relationship can help or hinder LAI acceptance. Most important is to move away from the problems caused by focusing only on adherence while ignoring the broader issues. It is my opinion that LAI implementation will be much easier once the toxic effects of adherence as bad behavior are banned from clinical interactions. Addressing these issues may help clear a path toward shifting from an oral antipsychotic to its LAI counterpart as the default approach.

Data availability statement

This article is based on previously published studies and does not report any new data. Therefore, no data sets were generated or analyzed.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: P.J.W.

Financial support

Funding of this paper was provided by the Neuroscience Education Institute through unrestricted educational grants from Alkermes, Inc.; Johnson and Johnson; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; and Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Competing interests

P.J.W.: Consultant: Alkermes, Abbvie, Anavex, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Delpor, Luye, Maplight Therapeutic, Serina Therapeutics, Teva, and Vanda.

Speaker: Alkermes, Bristol Myers Squibb, Luye, Neurocrine, Teva, and Vanda.

Stock Options: Delpor.

CNS SPECTRUMS

CME Review Article

Lies and LAIs: Why Accuracy of Information Is the Key to Understanding the Benefits and the Resistance to Using Long-acting Formulation

This CME activity is provided by HMP Education and Neuroscience Education Institute (NEI).

CME/CE Information

Target Audience: This activity has been developed for the healthcare team or individual prescriber specializing in mental health. All other healthcare team members interested in psychopharmacology are welcome for advanced study.

Learning Objectives: After completing this educational activity, you should be better able to:

-

• Address potential adherence challenges in ways that enhance rather than threaten therapeutic relationships

-

• Apply patient- and family-centered approaches to specialty psychopharmacology education on the use of LAIs as a first-line alternative to oral, including discussions about newer indications for bipolar I disorder

-

• Answer common questions asked by patients and families on the differences between specific LAI formulations and their corresponding oral counterparts

Accreditation: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by HMP Education and Neuroscience Education Institute (NEI). HMP Education is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Accreditation: In support of improving patient care, this activity has been planned and implemented by HMP Education and Neuroscience Education Institute (NEI). HMP Education is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), and the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), to provide continuing education for the healthcare team.

Activity Overview: This activity is best supported via a computer or device with current versions of the following browsers: Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, or Safari. A PDF reader is required for print publications. A post-test score of 70% or higher is required to receive CME/CE credit.

Estimated Time to Complete: 1 hour.

Continuing Education credit will be available for 3 years from the publication date of the associated article. Please visit https://nei.global/cnsspectrums2025 for additional information and to access the CE activity.

*NEI maintains a record of participation for 6 years.

Instructions for Optional Posttest and CME Credit

-

1. Read the article

-

2. Successfully complete the posttest at https://nei.global/CNS/LAI-03

-

3. Print your certificate

Questions? Email customerservice@neiglobal.com.

Credit Designations: The following are being offered for this activity:

-

• Physician: ACCME AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™

-

○ HMP Education designates this enduring material for a maximum of 1.00 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

-

-

• Nurse: ANCC contact hours

-

○ This continuing nursing education activity awards 1.00 contact hour. Provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, Provider #18006 for 1.00 contact hour.

-

-

• Nurse Practitioner: ACCME AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™

-

○ American Academy of Nurse Practitioners National Certification Program accepts AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ from organizations accredited by the ACCME.

-

○ The content in this activity pertaining to pharmacology is worth 1.00 continuing education hour of pharmacotherapeutics.

-

-

• Pharmacy: ACPE application-based contact hours

-

○ This internet enduring, knowledge-based activity has been approved for a maximum of 1.00 contact hour (.10 CEU).

-

○ The official record of credit will be in the CPE Monitor system. Following ACPE Policy, NEI and HMP Education must transmit your claim to CPE Monitor within 60 days from the date you complete this CPE activity and are unable to report your claimed credit after this 60-day period. Ensure your profile includes your DOB and NABP ID.

-

-

• Physician Associate/Assistant: AAPA Category 1 CME credits

-

○

HMP Education has been authorized by the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) to award AAPA Category 1 CME credits for activities planned in accordance with the AAPA CME Criteria. This internet enduring activity is designated for 1.00 AAPA Category 1 credit. Approval is valid until February 11, 2028. PAs should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation.

HMP Education has been authorized by the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) to award AAPA Category 1 CME credits for activities planned in accordance with the AAPA CME Criteria. This internet enduring activity is designated for 1.00 AAPA Category 1 credit. Approval is valid until February 11, 2028. PAs should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation.

-

-

• Psychology: APA CE credits

-

○

Continuing Education (CE) credits for psychologists are provided through the co-sponsorship of the American Psychological Association (APA) Office of Continuing Education in Psychology (CEP). The APA CEP Office maintains responsibility for the content of the programs. This activity awards 1.00 CE Credit.

Continuing Education (CE) credits for psychologists are provided through the co-sponsorship of the American Psychological Association (APA) Office of Continuing Education in Psychology (CEP). The APA CEP Office maintains responsibility for the content of the programs. This activity awards 1.00 CE Credit.

-

-

• Social Work: ASWB-ACE CE credits

-

○ As a Jointly Accredited Organization, HMP Education is approved to offer social work continuing education by the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB) Approved Continuing Education (ACE) program. Organizations, not individual courses, are approved under this program. Regulatory boards are the final authority on courses accepted for continuing education credit. Social workers completing this internet enduring course receive 1.00 general continuing education credit.

-

-

• Non-Physician Member of the Healthcare Team: Certificate of Participation

-

○ HMP Education awards hours of participation (consistent with the designated number of AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™) to a participant who successfully completes this educational activity.

-

Peer Review: The content was peer-reviewed by an MD, LFAPA specializing in psychiatry, forensic, and addiction—to ensure the scientific accuracy and medical relevance of information presented and its independence from commercial bias. NEI and HMP Education take responsibility for the content, quality, and scientific integrity of this CME/CE activity.

Disclosures: All individuals in a position to influence or control content are required to disclose any relevant financial relationships. Any relevant financial relationships were mitigated prior to the activity being planned, developed, or presented.

Faculty Author/Presenter Peter Weiden, MD

Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, SUNY Stony Brook, New York, NY

Consultant/Advisor: Bristol Myers Squibb, Boeringer Ingelheim, Deplor, Lyndra, Kuleon, MapLight, Teva, Alkermes

Speakers Bureau: Bristol Myers Squibb, Neurocrine, Teva, Alkermes

Stock: Deplor, Karuna Therapeutics

The remaining planning committee members, content editors, peer reviewer, and NEI planners/staff have no financial relationships to disclose. NEI and HMP Education planners and staff include Meghan Grady, Caroline O’Brien, MS, Ali Holladay, Moriah Carswell, Andrea Zimmerman, EdD, CHCP, Brielle Calleo, and Bahgwan Bahroo, MD, LFAPA.

Disclosure of Off-Label Use: This educational activity may include discussion of unlabeled and/or investigational uses of agents that are not currently labeled for such use by the FDA. Please consult the product prescribing information for full disclosure of labeled uses.

Cultural Linguistic Competency and Implicit Bias: A variety of resources addressing cultural and linguistic competencies and strategies for understanding and reducing implicit bias can be found in this handout—download here.

Accessibility Statement.

For questions regarding this educational activity, or to cancel your account, please email customerservice@neiglobal.com.

Support: This activity is supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Alkermes, Inc., Teva Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson Innovative Medicine, and Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.

HMP Education has been authorized by the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) to award AAPA Category 1 CME credits for activities planned in accordance with the AAPA CME Criteria. This internet enduring activity is designated for 1.00 AAPA Category 1 credit. Approval is valid until February 11, 2028. PAs should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation.

HMP Education has been authorized by the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) to award AAPA Category 1 CME credits for activities planned in accordance with the AAPA CME Criteria. This internet enduring activity is designated for 1.00 AAPA Category 1 credit. Approval is valid until February 11, 2028. PAs should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation. Continuing Education (CE) credits for psychologists are provided through the co-sponsorship of the American Psychological Association (APA) Office of Continuing Education in Psychology (CEP). The APA CEP Office maintains responsibility for the content of the programs. This activity awards 1.00 CE Credit.

Continuing Education (CE) credits for psychologists are provided through the co-sponsorship of the American Psychological Association (APA) Office of Continuing Education in Psychology (CEP). The APA CEP Office maintains responsibility for the content of the programs. This activity awards 1.00 CE Credit.