1. Introduction

The phenomenon of Stokes drift implies that periodic water waves in irrotational flow induce a net Lagrangian-mean transport along their direction of propagation (van den Bremer & Breivik Reference van den Bremer and Breivik2017). Although discovered theoretically a long time ago by Stokes (Reference Stokes1847), Stokes drift has been elusive in laboratory experiments. A particular difficulty is in separating it from Eulerian-mean flows whose properties are determined by the boundary conditions of the flume itself (Monismith Reference Monismith2020), although recent investigations in wave flumes where waves (or wave groups) propagate on initially quiescent water have provided convincing evidence (Grue & Kolaas Reference Grue and Kolaas2017; van den Bremer et al. Reference van den Bremer, Whittaker, Calvert, Raby and Taylor2019).

Floating and suspended matter of small enough size, such as microplastics (van Sebille Reference van Sebille2020), oil spills (Boufadel et al. Reference Boufadel, Bracco, Chassignet, Chen, D’Asaro, Dewar, Garcia-Pineda, Justić, Katz and Kourafalou2021), plankton (Hernandez-Carrasco et al. Reference Hernandez-Carrasco, Orfila, Rossi and Garcon2018), larvae and nutrients (Röhrs et al. Reference Röhrs, Christensen, Vikebø, Sundby, Sætra and Broström2014), are transported in the oceans with the Lagrangian-mean current

![]() $\bar {u}_L$

, equal to the Eulerian-mean current,

$\bar {u}_L$

, equal to the Eulerian-mean current,

![]() $\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}(z)$

, plus the Stokes drift

$\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}(z)$

, plus the Stokes drift

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_s$

, i.e.

$\boldsymbol{u}_s$

, i.e.

![]() $ \bar {\boldsymbol{u}}_L(z) = \bar {\boldsymbol{u}}(z) + \boldsymbol{u}_s(z)$

. The importance of correctly modelling ocean transport makes prediction of the Lagrangian current a pivotal, but still open, question. For a monochromatic (nearly) linear wave of wavenumber

$ \bar {\boldsymbol{u}}_L(z) = \bar {\boldsymbol{u}}(z) + \boldsymbol{u}_s(z)$

. The importance of correctly modelling ocean transport makes prediction of the Lagrangian current a pivotal, but still open, question. For a monochromatic (nearly) linear wave of wavenumber

![]() $k_0$

and constant amplitude

$k_0$

and constant amplitude

![]() $a$

propagating in deep water the Stokes drift velocity along the direction of wave propagation is

$a$

propagating in deep water the Stokes drift velocity along the direction of wave propagation is

where the intrinsic phase velocity (i.e. in the reference system where the surface is at rest) is

![]() $c$

. The phase velocity and group velocity,

$c$

. The phase velocity and group velocity,

![]() $c_g$

, are given by

$c_g$

, are given by

where

![]() $g$

is the gravitational acceleration. A contribution to oceanic transport velocities of magnitude

$g$

is the gravitational acceleration. A contribution to oceanic transport velocities of magnitude

![]() $u_s$

can be highly significant and must be taken into account when predicting, e.g. the development of oil spills or the fate of microplastic particles (Hackett et al. Reference Hackett, Breivik and Wettre2006; Onink et al. Reference Onink, Wichmann, Delandmeter and van Sebille2019; Cunningham, Higgins & van den Bremer Reference Cunningham, Higgins and van den Bremer2022).

$u_s$

can be highly significant and must be taken into account when predicting, e.g. the development of oil spills or the fate of microplastic particles (Hackett et al. Reference Hackett, Breivik and Wettre2006; Onink et al. Reference Onink, Wichmann, Delandmeter and van Sebille2019; Cunningham, Higgins & van den Bremer Reference Cunningham, Higgins and van den Bremer2022).

The naïve approach for the modeller is to obtain the Lagrangian-mean current by adding the Stokes drift calculated from wave spectra to the Eulerian flow, which is assumed to be unaffected by waves. However, several field studies have observed that waves appear to have no discernible effect on the Lagrangian-mean current, contrary to theory (Smith Reference Smith2006; Lentz et al. Reference Lentz, Fewings, Howd, Fredericks and Hathaway2008). Smith (Reference Smith2006) found that even short wave groups experience an Eulerian-mean current, which acts to entirely cancel the Stokes drift at the surface, and that the counter-current is strongly correlated with the presence of Stokes drift – it appears only when the wave group is present and disappears once it has passed. Other observations find that the inclusion of Stokes drift does improve results, however, e.g. Röhrs et al. (Reference Röhrs, Christensen, Hole, Broström, Drivdal and Sundby2012), who used drifters in coastal waters and employ a coupled wave–ocean model.

Experiments of waves propagating on currents have also yielded results which are inconsistent with a simple addition of Stokes drift. In a careful laboratory study, Monismith et al. (Reference Monismith, Cowen, Nepf and Thais2007) found no change in Lagrangian-mean flow when waves were added, i.e. the Stokes drift is locally cancelled by an equal and opposite Eulerian flow. Moreover, reanalysis of previous experiments by Swan (Reference Swan1990a ,Reference Swan b ), Jiang & Street (Reference Jiang and Street1991) and Thais (Reference Thais1994) supported the same conclusion (the observation seems to have been made also in the PhD work of Cowen Reference Cowen1996). These results have remained something of a puzzle, as ‘[n]o existing theory of wave–current interactions explains this behaviour’ as Monismith et al. (Reference Monismith, Cowen, Nepf and Thais2007) put it. Here, we demonstrate a mechanism that could resolve this conundrum at least in part.

While being careful not to draw definite conclusions concerning the above-mentioned results, one might remark that some level of turbulence was likely to have been present alongside the waves in all these experiments. The flow of Swan (Reference Swan1990b

) passed through a honeycomb flow straightener which will have generated significant turbulence levels, and the mean shear of the flow would provide further turbulence production. Jiang & Street (Reference Jiang and Street1991) discuss wave–turbulence interactions in their experiments in detail (further detailed by Cheung & Street Reference Cheung and Street1988), as do Thais & Magnaudet (Reference Thais and Magnaudet1996) for the experiment of Thais (Reference Thais1994). The experiment of Swan (Reference Swan1990a

) did not have imposed wind or current. Since measurements were made after the wavemaker had run for many hours, one may speculate that turbulence might well have been present, created, e.g. in the oscillating bottom boundary layer (the depth was less than a third of a wavelength) or thermal convection, with which the waves would have had ample time to interact, the flume being

![]() $18$

m long. Naturally, this can be no more than speculation so long afterwards.

$18$

m long. Naturally, this can be no more than speculation so long afterwards.

There have been indications that the interaction between waves and pre-existing turbulence will result in an alteration of the Eulerian current. Waves have the effect of reorienting and intensifying the turbulence beneath, as predicted theoretically (Magnaudet & Masbernat Reference Magnaudet and Masbernat1990; Teixeira & Belcher Reference Teixeira and Belcher2002), and confirmed numerically (e.g. Guo & Shen Reference Guo and Shen2013; Tsai et al. Reference Tsai, Lu, Chen, Dai and Phillips2017; Xuan et al. Reference Xuan, Deng and Shen2019, Reference Xuan, Deng and Shen2020, Reference Xuan, Deng and Shen2024), experimentally (e.g. Bliven et al. Reference Bliven, Huang and Long1984; Cheung & Street Reference Cheung and Street1988; Thais & Magnaudet Reference Thais and Magnaudet1996; Savelyev, Maxeiner & Chalikov Reference Savelyev, Maxeiner and Chalikov2012; Smeltzer et al. Reference Smeltzer, Rømcke, Hearst and Ellingsen2023) and in field studies (Cavaleri & Zecchetto Reference Cavaleri and Zecchetto1987; Qiao et al. Reference Qiao, Yuan, Deng, Dai and Song2016). Langmuir turbulence, the disordered pattern of long rolls approximately aligned with wind and waves due to Langmuir circulation formation at sea (McWilliams, Sullivan & Moeng Reference McWilliams, Sullivan and Moeng1997), was observed by Plueddemann et al. (Reference Plueddemann, Smith, Farmer, Weller, Crawford, Pinkel, Vagle and Gnanadesikan1996) to persist for up to a day after the wind had stopped, sustained by the surface waves the wind had created.

Pearson (Reference Pearson2018) predicted with a theoretical argument that the interaction between waves and ambient turbulence would, on average, produce an Eulerian-mean current which opposes the Stokes drift near the surface. His paper has received little attention up until now, but in our theoretical work later, we shall draw heavily on his work and apply it to our own settings. Pearson’s prediction shows that the Eulerian-mean current,

![]() $\bar {u}(z)$

, is opposite and similar to

$\bar {u}(z)$

, is opposite and similar to

![]() $u_s(z)$

near the surface but changes sign beneath the wave-influenced surface layer and integrates to zero as a function of depth. Although the wave–turbulence-induced Eulerian-mean current incurs no net change in mass transport, it will partly cancel the Stokes drift at the surface, and we therefore refer to it as an ‘anti-Stokes’ current.

$u_s(z)$

near the surface but changes sign beneath the wave-influenced surface layer and integrates to zero as a function of depth. Although the wave–turbulence-induced Eulerian-mean current incurs no net change in mass transport, it will partly cancel the Stokes drift at the surface, and we therefore refer to it as an ‘anti-Stokes’ current.

The picture which emerges is that, when waves and turbulence first meet, the combined flow goes through a transient ‘spin-up’ period before a new quasi-equilibrium is reached, which includes the Eulerian anti-Stokes current. In our set-up, turbulence is created at the inlet of the mean flow and as it moves downstream towards the point of measurement it encounters waves and develops together with the velocity profile. When the time of effective interaction is short, the result of partial spin-up is captured, while turbulence moving in the presence of waves for sufficiently long could reach a quasi-steady state before it is measured. The conditions for ‘short’ and ‘long’ interaction time are satisfied in our experiments, for wave groups (Experiment 1) and regular waves (Experiments 2 and 3), respectively.

We review and extend statistical theory for both the transient and steady stages, and derive a theory based on Rapid distortion theory (RDT) which captures the underlying physics of the ‘spin-up’ period and shows that the Eulerian acceleration of the current will exhibit approximately the same depth-dependent behaviour as the resulting current that we observe. The process is intimately related to the so-called ‘CL2’ mechanism which creates Langmuir circulation (Craik & Leibovich Reference Craik and Leibovich1976). It is worth noting that the CL2 mechanism, as lucidly reviewed by Leibovich (Reference Leibovich1983), requires the presence of an Eulerian-mean flow with slope (i.e.

![]() ${\rm d}\bar {u}/{\rm d} z$

) of the same sign as that of the Stokes drift profile, whereas the anti-Stokes current induced by wave–turbulence interaction,

${\rm d}\bar {u}/{\rm d} z$

) of the same sign as that of the Stokes drift profile, whereas the anti-Stokes current induced by wave–turbulence interaction,

![]() $\bar {u}(z)$

, has opposite slope. Thus,

$\bar {u}(z)$

, has opposite slope. Thus,

![]() $({\rm d}\bar {u}/{\rm d} z)\boldsymbol{\cdot }({\rm d} u_s/{\rm d} z) \lt 0$

, which implies that the induced current tends to stabilise the combined system with respect to the CL2 instability.

$({\rm d}\bar {u}/{\rm d} z)\boldsymbol{\cdot }({\rm d} u_s/{\rm d} z) \lt 0$

, which implies that the induced current tends to stabilise the combined system with respect to the CL2 instability.

1.1. Possible previous observations

Indications are that the same physical phenomenon has been at play in wave–current experiments performed in the context of studying the bottom boundary layer in shallow wave–current flows, motivated by understanding sediment transport (thus not highlighting the significance for ocean modelling). A string of independent measurements of the mean Eulerian flow in the presence and absence of waves by van Hoften & Karaki (Reference van Hoften and Karaki1977), Bakker & van Doorn (Reference Bakker and van Doorn1978), van Doorn (Reference van Doorn1981), Kemp & Simons (Reference Kemp and Simons1982, Reference Kemp and Simons1983), Rashidi, Hetsroni & Banerjee (Reference Rashidi, Hetsroni and Banerjee1992), Klopman (Reference Klopman1994), Mathisen & Madsen (Reference Mathisen and Madsen1996) and Singh & Debnath (Reference Singh and Debnath2017), all showed that the waves caused a significant alteration of the mean flow near the surface, adding a contribution in the direction opposite to wave propagation in the near-surface region. More recent experiments also report the same (Zhang & Simons Reference Zhang and Simons2019; Peruzzi et al. Reference Peruzzi, Vettori, Poggi, Blondeaux, Ridolfi and Manes2021). In addition to making the same observation, Umeyama (Reference Umeyama2005, Reference Umeyama2009) found in his experiments that the vertical structure of the streamwise–vertical Reynolds shear stress depends strongly on the wave-propagation direction in the near-surface region.

Since these studies considered shallow currents where waves affect the bottom boundary layer, a direct comparison with our experiment in deep water is dubious, yet subsequent theoretical analysis gives reason to suspect a close connection. Nielsen & You (Reference Nielsen and You1996) and Dingemans et al. (Reference Dingemans, van Kester, Radder and Uittenbogaard1996) propose two early explanations for the difference in Eulerian-mean current; the former relies on a force balance on average including the mean stress from waves and turbulence represented by eddy viscosity, the latter on the creation of streamwise rolls due to the Craik–Leibovich vortex force due to the sidewall boundary layers, whose presence was observed by Klopman (Reference Klopman1994). Groeneweg & Klopman (Reference Groeneweg and Klopman1998) developed a more sophisticated theory based on Generalised Lagrangian Mean (GLM) theory, similar in spirit to the physical process we consider herein, but their analysis is not easy to compare with ours since it involves a set of coupled nonlinear differential equations and a complex turbulence model. Interestingly, Groeneweg & Battjes (Reference Groeneweg and Battjes2003) reconcile all three descriptions, at least qualitatively, by extending their GLM theory to three dimensions. Huang & Mei (Reference Huang and Mei2003) provided a careful theory, once more primarily concerned with the effect of waves on the bottom boundary layer, but also shedding light on the observed changes near the surface. They, too, use the simple eddy-viscosity model of turbulence. In particular, they conclude that the mean wave-induced shear stress near the free surface is opposite in direction to the wave propagation, and is ‘due largely to the distortion of eddy viscosity near the surface’. With a simple mixing-length model, Umeyama (Reference Umeyama2005, Reference Umeyama2009) as well as Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Tan, Lim and Zhang2006) find reasonable agreement with experiments. Olabarrieta, Medina & Castanedo (Reference Olabarrieta, Medina and Castanedo2010) devise a simplified numerical model to avoid the restriction of low-steepness waves, and the perturbation theory of Tambroni, Blondeaux & Vittori (Reference Tambroni, Blondeaux and Vittori2015) yields a model able to predict the Eulerian-mean velocity profile throughout the water column; both of the latter employ depth-dependent eddy-viscosity models. Crucially, all of these many model explanations depend on the simultaneous presence of waves and turbulence to explain the change in mean flow.

When reviewing previous numerical studies of waves in the presence of turbulence, one can also find evidence of the same Eulerian-mean current creation that we observe experimentally, even though the authors themselves have not discussed its significance especially. Borue, Orszag & Staroselsky (Reference Borue, Orszag and Staroselsky1995) merely remark that the change in mean current near the surface should be studied further, while Kawamura (Reference Kawamura2000) notes that the changes in current are higher the larger the Stokes drift magnitude, and discusses consequences for (Langmuir) turbulence production. Also Fujiwara, Yoshikawa & Matsumura (Reference Fujiwara, Yoshikawa and Matsumura2020) find Eulerian-mean velocity profiles under Langmuir turbulence which are qualitatively very similar to those we measure under regular waves (their figures 6a and 9a) and report in § 2.1.2, but do not discuss this point particularly.

1.2. Other wave-driven currents

Eulerian-mean flow driven by waves also occurs without pre-existing turbulence or vorticity from two separate mechanisms. First, to compensate for the divergence of Stokes drift on the group scale, Stokes drift in otherwise quiescent water must also be accompanied by an Eulerian return flow (e.g. Longuet-Higgins & Stewart Reference Longuet-Higgins and Stewart1962; van den Bremer & Taylor Reference van den Bremer and Taylor2016) for wave groups. In deep water, the depth-integrated Stokes drift and the depth-integrated Eulerian return flow are equal and opposite, and mass is preserved globally, not locally. This phenomenon is reviewed further in § 4.1. The Stokes drift profile is highly concentrated near the surface whereas the return flow varies slowly with depth. The Eulerian-mean ‘anti-Stokes’ current we observe varies rapidly with depth and cannot be explained by this mass conservation mechanism. Second, there is also surface streaming driven by viscosity confined to a thin viscous boundary layer beneath the surface, resulting from the imparting of wave momentum to the fluid as the waves decay (Longuet-Higgins Reference Longuet-Higgins1953; Craik Reference Craik1982). Tsai et al. (Reference Tsai, Lu, Chen, Dai and Phillips2017) and, recently, Fujiwara (Reference Fujiwara2024), studied how this current can also interact with waves to generate small-scale turbulence of Langmuir type via the CL2 mechanism. The viscous sub-surface layer is likely thinner than what our measurements can resolve, and, additionally, the resulting Eulerian-mean flow is directed along, not against, the direction of wave propagation. Third, the Earth’s rotation causes a wave-induced Eulerian-mean flow that can exactly cancel the Stokes drift (for periodic waves and in the absence of viscosity), which is also known as the anti-Stokes flow (Hasselmann Reference Hasselmann1970). While this rotation-induced anti-Stokes flow could explain some field observations (Lentz et al. Reference Lentz, Fewings, Howd, Fredericks and Hathaway2008; Röhrs et al. Reference Röhrs, Christensen, Hole, Broström, Drivdal and Sundby2012), it cannot explain experimental results discussed above and presented herein as our characteristic time scales are vastly smaller than Earth’s period of rotation (the Rossby number is large). Hence, neither of these three mechanisms can explain the observations just mentioned, nor those by, e.g. Monismith et al. (Reference Monismith, Cowen, Nepf and Thais2007), or indeed those we report herein.

2. Experimental methods

We report on measurements performed during three experimental campaigns in the water channel facility at NTNU Trondheim, shown in figure 1(a). A pump system circulates water through the test section of dimensions

![]() $11.2$

m

$11.2$

m

![]() $\times$

$\times$

![]() $1.8$

m

$1.8$

m

![]() $\times$

$\times$

![]() $1.0$

m (length

$1.0$

m (length

![]() $\times$

width

$\times$

width

![]() $\times$

height).

$\times$

height).

Figure 1. Experimental set-up: (a) side view of water channel with flow from left to right and field of view (FOV) indicated with a green rectangle, (b) top view of measurement region for the stereo particle image velocimetry (PIV) set-up in Experiment 1, including positions of wave probes (WPs) and laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) camera for surface detection; (c) longitudinal view of the planar PIV set-up in Experiments 2 and 3. Experiment 2 employed three stacked cameras as shown, whereas in Experiment 3, a single PIV camera was used.

An active grid at the inlet of the test section allowed the turbulence to be generated and varied. The grid consists of square wings measuring

![]() $10$

cm across the diagonal, attached to

$10$

cm across the diagonal, attached to

![]() $18$

vertically and

$18$

vertically and

![]() $10$

horizontally oriented bars, each controlled independently by a stepper motor. Several different active-grid actuation cases were investigated, listed in Appendix A. The grid wings were rotated with random rotational velocity, acceleration and period within set limits (Hearst & Lavoie Reference Hearst and Lavoie2015; Smeltzer et al. Reference Smeltzer, Rømcke, Hearst and Ellingsen2023), or in one case flapped back and forth between two positions at irregular time intervals. The instantaneous rotation frequency of the grid wings varied about a mean active-grid frequency

$10$

horizontally oriented bars, each controlled independently by a stepper motor. Several different active-grid actuation cases were investigated, listed in Appendix A. The grid wings were rotated with random rotational velocity, acceleration and period within set limits (Hearst & Lavoie Reference Hearst and Lavoie2015; Smeltzer et al. Reference Smeltzer, Rømcke, Hearst and Ellingsen2023), or in one case flapped back and forth between two positions at irregular time intervals. The instantaneous rotation frequency of the grid wings varied about a mean active-grid frequency

![]() $\overline {f_G}$

by

$\overline {f_G}$

by

![]() $\pm 0.5\overline {f_G}$

with a top-hat distribution. In Experiments 1 and 2 (see §§ 2.1.1 and 2.1.2) a surface plate was mounted from the grid that extends downstream approximately

$\pm 0.5\overline {f_G}$

with a top-hat distribution. In Experiments 1 and 2 (see §§ 2.1.1 and 2.1.2) a surface plate was mounted from the grid that extends downstream approximately

![]() $1$

m to dampen surface disturbances produced by the grid. A diagram of the set-up is shown in figure 1, and further details are given by Jooss et al. (Reference Jooss, Li, Bracchi and Hearst2021).

$1$

m to dampen surface disturbances produced by the grid. A diagram of the set-up is shown in figure 1, and further details are given by Jooss et al. (Reference Jooss, Li, Bracchi and Hearst2021).

The bottom and sidewall boundary layers are thin enough not to reach the central part of the flow. They reach a maximum of approximately

![]() $20$

cm at the point where velocity measurements were made, and are thinner upstream where waves and turbulence interact, hence essentially all turbulence which affects our experimental results has been generated by the grid and not boundary layers. The upstream distance within which waves and turbulence interact is denoted

$20$

cm at the point where velocity measurements were made, and are thinner upstream where waves and turbulence interact, hence essentially all turbulence which affects our experimental results has been generated by the grid and not boundary layers. The upstream distance within which waves and turbulence interact is denoted

![]() $L_{\textit{FOV}}$

and is tabulated in table 1.

$L_{\textit{FOV}}$

and is tabulated in table 1.

Table 1. Overview of the three experiments. Here,

![]() $h$

is the mean water depth,

$h$

is the mean water depth,

![]() $f_0$

is the wave frequency in the laboratory frame (wavemaker frequency),

$f_0$

is the wave frequency in the laboratory frame (wavemaker frequency),

![]() $f_{\textit{ac}}$

is the PIV acquisition frequency,

$f_{\textit{ac}}$

is the PIV acquisition frequency,

![]() $N_{\textit{ens}}$

is the number of repetitions per case,

$N_{\textit{ens}}$

is the number of repetitions per case,

![]() $T_{\textit{PIV}}$

is the duration of each acquisition interval and

$T_{\textit{PIV}}$

is the duration of each acquisition interval and

![]() $L_{\textit{FOV}}$

is the distance the flow travels as a free stream upstream of the measurement field of view.

$L_{\textit{FOV}}$

is the distance the flow travels as a free stream upstream of the measurement field of view.

![]() $\dagger$

: except case 1.C.2 where

$\dagger$

: except case 1.C.2 where

![]() $ N_{\textit{ens}}=20$

.

$ N_{\textit{ens}}=20$

.

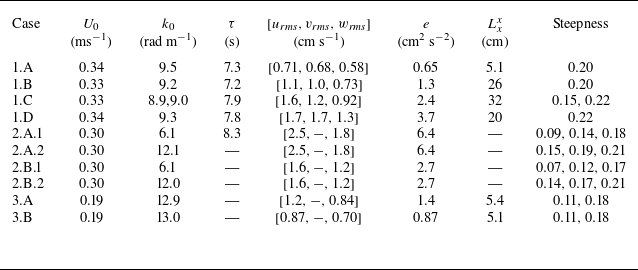

Table 2. Measured flow quantities: mean current

![]() $U_0$

, carrier-wave number

$U_0$

, carrier-wave number

![]() $k_0$

, measured group temporal width in the lab frame

$k_0$

, measured group temporal width in the lab frame

![]() $\tau$

, root-mean-square turbulent velocity components (subscript ‘rms’), turbulent kinetic energy

$\tau$

, root-mean-square turbulent velocity components (subscript ‘rms’), turbulent kinetic energy

![]() $e$

(calculated for Experiments 2 and 3 as discussed in main text), and streamwise–streamwise integral scale

$e$

(calculated for Experiments 2 and 3 as discussed in main text), and streamwise–streamwise integral scale

![]() $L_x^x$

. Steepness is given as

$L_x^x$

. Steepness is given as

![]() $k_0a_{{p}}$

for Experiment 1 where

$k_0a_{{p}}$

for Experiment 1 where

![]() $a_{{p}}$

is peak amplitude, and

$a_{{p}}$

is peak amplitude, and

![]() $ak_0$

in Experiments 2 and 3. Where several values of steepness are listed (cases 1.C and 2.A–3.B), these are referred to elsewhere as 1.C.1, 1.C.2, 2.A.1.1, 2.A.1.2, etc.

$ak_0$

in Experiments 2 and 3. Where several values of steepness are listed (cases 1.C and 2.A–3.B), these are referred to elsewhere as 1.C.1, 1.C.2, 2.A.1.1, 2.A.1.2, etc.

A plunger wavemaker at the downstream end of the test section (

![]() $10.2$

m from the active grid) was used to generate waves propagating upstream on the current. Waves with a group velocity lower than the mean flow were unable to propagate upstream, thus preventing high-frequency wave noise and unwanted free harmonics (parasitic waves) from the wavemaker from entering the test section. Wave properties were obtained from surface elevation measured by a pair of resistive wave probes (HR Wallingford) near the measurement position.

$10.2$

m from the active grid) was used to generate waves propagating upstream on the current. Waves with a group velocity lower than the mean flow were unable to propagate upstream, thus preventing high-frequency wave noise and unwanted free harmonics (parasitic waves) from the wavemaker from entering the test section. Wave properties were obtained from surface elevation measured by a pair of resistive wave probes (HR Wallingford) near the measurement position.

As indicated by the coordinate system in figure 1(a), the waves propagate in the positive

![]() $x$

-direction, while the flow is in the negative

$x$

-direction, while the flow is in the negative

![]() $x$

-direction. The mean free-surface level is at

$x$

-direction. The mean free-surface level is at

![]() $z=0$

.

$z=0$

.

2.1. Experimental campaigns

Three separate experimental campaigns were conducted between 2020 and 2023. Experiment 1 was also reported in Smeltzer et al. (Reference Smeltzer, Rømcke, Hearst and Ellingsen2023), where the focus was on the change in turbulent enstrophy and wave scattering.

The three experiments investigate essentially the same phenomenon, but with fundamental differences in experimental design and the nature of the acquired measurement data. A summary is provided in table 1.

2.1.1. Experiment 1: wave groups

Cases 1.A-1.D in tables 1–3 are from Experiment 1. Wave groups were generated that propagated upstream atop the turbulent flows. The water depth

![]() $h$

was

$h$

was

![]() $0.4$

m. The velocity field was measured using stereoscopic particle image velocimetry (SPIV), measuring all three velocity components in a plane perpendicular to the mean flow located a distance

$0.4$

m. The velocity field was measured using stereoscopic particle image velocimetry (SPIV), measuring all three velocity components in a plane perpendicular to the mean flow located a distance

![]() $8.38$

m downstream from the active grid (i.e.

$8.38$

m downstream from the active grid (i.e.

![]() $83.8$

grid units), and

$83.8$

grid units), and

![]() $L_{\textit{FOV}}=7.38$

m downstream of the trailing edge of the surface plate. Two 25-megapixel cameras were mounted on either side of the test section, viewing the field of view at

$L_{\textit{FOV}}=7.38$

m downstream of the trailing edge of the surface plate. Two 25-megapixel cameras were mounted on either side of the test section, viewing the field of view at

![]() $\pm 45^\circ$

to the

$\pm 45^\circ$

to the

![]() $x$

-axis as shown in figure 1

b). The field of view was

$x$

-axis as shown in figure 1

b). The field of view was

![]() $0.12\times 0.14$

m

$0.12\times 0.14$

m

![]() $^2$

. Particle images recorded by the two cameras were processed using a final pass of

$^2$

. Particle images recorded by the two cameras were processed using a final pass of

![]() $48\times 48$

pixel interrogation window and a 50 % overlap, resulting in a velocity vector spacing of about

$48\times 48$

pixel interrogation window and a 50 % overlap, resulting in a velocity vector spacing of about

![]() $0.8$

mm. The free-surface intersection with the SPIV plane was detected from laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) images recorded by a camera viewing the plane at an oblique angle from the air side. A small amount of rhodamine-6G was added to the water generating image contrast between the air and water regions, and the free surface was detected from the image intensity gradient. Further details can be found in Smeltzer et al. (Reference Smeltzer, Rømcke, Hearst and Ellingsen2023).

$0.8$

mm. The free-surface intersection with the SPIV plane was detected from laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) images recorded by a camera viewing the plane at an oblique angle from the air side. A small amount of rhodamine-6G was added to the water generating image contrast between the air and water regions, and the free surface was detected from the image intensity gradient. Further details can be found in Smeltzer et al. (Reference Smeltzer, Rømcke, Hearst and Ellingsen2023).

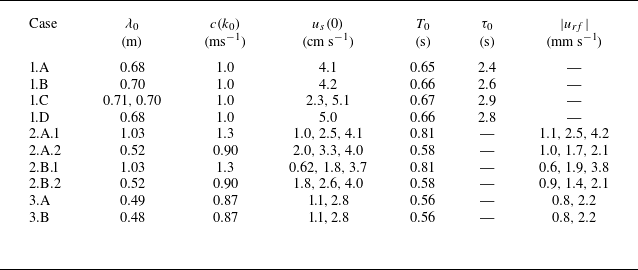

Table 3. Wave quantities derived from measured values in table 2. Here,

![]() $\lambda _0=2\pi /k_0$

is the carrier wavelength,

$\lambda _0=2\pi /k_0$

is the carrier wavelength,

![]() $c(k_0)=\sqrt {g/k_0}$

is the carrier-wave phase velocity,

$c(k_0)=\sqrt {g/k_0}$

is the carrier-wave phase velocity,

![]() $u_s(0)=(ak_0)^2c(k_0)$

is the Stokes drift velocity of the carrier wave at the surface,

$u_s(0)=(ak_0)^2c(k_0)$

is the Stokes drift velocity of the carrier wave at the surface,

![]() $T_0=\lambda _0/c(k_0)$

is the intrinsic wave period,

$T_0=\lambda _0/c(k_0)$

is the intrinsic wave period,

![]() $\tau _0$

the intrinsic group width from (3.2) and

$\tau _0$

the intrinsic group width from (3.2) and

![]() $u_{{rf}}$

is the Eulerian return flow from (4.2).

$u_{{rf}}$

is the Eulerian return flow from (4.2).

For each wave group, SPIV/LIF measurements taken during three time intervals were used: well before the group arrived, and at the leading and trailing edges of the group envelope, referred to as intervals 1, 2 and 3, respectively, as shown in figure 2

b). We consider the difference in mean velocity between intervals 1 and 3 here, with interval 2 as a check to verify that the change is indeed due to waves. Values for all three intervals in all cases can be found in the Supplementary Materials available at https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2026.11163. The duration of the measurements for each interval,

![]() $T_{\textit{PIV}}$

, was

$T_{\textit{PIV}}$

, was

![]() $10$

s and PIV and LIF were sampled at

$10$

s and PIV and LIF were sampled at

![]() $f_{\textit{ac}}=8$

Hz. After each group, residual waves from reflections were allowed to dissipate for approximately five minutes before the next wave group was generated. The above procedure was performed a total of

$f_{\textit{ac}}=8$

Hz. After each group, residual waves from reflections were allowed to dissipate for approximately five minutes before the next wave group was generated. The above procedure was performed a total of

![]() $N_{\textit{ens}}=60$

times to produce ensemble statistics, except for the case 1.C.2 which was performed

$N_{\textit{ens}}=60$

times to produce ensemble statistics, except for the case 1.C.2 which was performed

![]() $20$

times. In case 1.B, only vertically orientated bars of the active grid were actuated. For case 1.A, the grid was stationary with the wings aligned with the flow in the position of least blockage (see also Appendix A). The experimental conditions are listed in table 1.

$20$

times. In case 1.B, only vertically orientated bars of the active grid were actuated. For case 1.A, the grid was stationary with the wings aligned with the flow in the position of least blockage (see also Appendix A). The experimental conditions are listed in table 1.

Figure 2. (a) Example surface elevation of a single wave group from Experiment 1 as a function of time

![]() $t$

, measured by a wave probe at the measurement location. (b) Example from Experiment 1 of an ensemble-average group surface elevation amplitude envelope as a function of time normalised by the measured group temporal width

$t$

, measured by a wave probe at the measurement location. (b) Example from Experiment 1 of an ensemble-average group surface elevation amplitude envelope as a function of time normalised by the measured group temporal width

![]() $\tau$

for case 1.D (see (3.1)). The time intervals for SPIV measurement (1–3) are shown with vertical dashed lines. (c) Surface elevation measurements of one ensemble from Experiment 3 (cases 3.A and 3.B), which shows the onset of a regular-wave train. The red box indicates the interval used for analysis.

$\tau$

for case 1.D (see (3.1)). The time intervals for SPIV measurement (1–3) are shown with vertical dashed lines. (c) Surface elevation measurements of one ensemble from Experiment 3 (cases 3.A and 3.B), which shows the onset of a regular-wave train. The red box indicates the interval used for analysis.

The wave groups were generated with the wavemaker motion having carrier frequency

![]() $f_0 = 1.02$

Hz and a Gaussian amplitude envelope of the form

$f_0 = 1.02$

Hz and a Gaussian amplitude envelope of the form

for

![]() $0\leqslant t\leqslant T_{{wm}}$

, where

$0\leqslant t\leqslant T_{{wm}}$

, where

![]() $S_0$

is the peak stroke,

$S_0$

is the peak stroke,

![]() $\tau _{{wm}}= 6\,{\textrm{s}}$

is the group width in time as applied to the wavemaker signals and

$\tau _{{wm}}= 6\,{\textrm{s}}$

is the group width in time as applied to the wavemaker signals and

![]() $T_{{wm}} =24\,{s}$

was the duration over which the wavemaker plungers were actuated. The surface elevation for one wave group measured at the SPIV measurement location is shown in figure 2(a).

$T_{{wm}} =24\,{s}$

was the duration over which the wavemaker plungers were actuated. The surface elevation for one wave group measured at the SPIV measurement location is shown in figure 2(a).

2.1.2. Experiment 2: regular waves

Cases 2.A and 2.B in tables 1–3 are from Experiment 2. Regular waves were generated propagating upstream atop two different flows with comparable mean velocity but different levels of turbulence as controlled by the active grid. A planar PIV set-up with a light sheet, orientated in the streamwise–vertical (

![]() $xz$

) plane, measured the in-plane streamwise and vertical velocity components. The field of view was centred

$xz$

) plane, measured the in-plane streamwise and vertical velocity components. The field of view was centred

![]() $L_{\textit{FOV}}=8.5$

m downstream of the surface plate’s trailing edge (see figure 1). Three cameras stacked vertically (from the top to bottom: two 16 megapixel cameras and one 5.5 megapixel camera) covered a field of view extending over the entire water depth (

$L_{\textit{FOV}}=8.5$

m downstream of the surface plate’s trailing edge (see figure 1). Three cameras stacked vertically (from the top to bottom: two 16 megapixel cameras and one 5.5 megapixel camera) covered a field of view extending over the entire water depth (

![]() $h = 0.80$

m) of the channel, roughly

$h = 0.80$

m) of the channel, roughly

![]() $21.7$

cm wide. The parameters for Experiment 2 are listed in table 1. For both flow cases, waves of two frequencies

$21.7$

cm wide. The parameters for Experiment 2 are listed in table 1. For both flow cases, waves of two frequencies

![]() $0.94$

and

$0.94$

and

![]() $1.16$

Hz each with three different steepness values were generated. For each case,

$1.16$

Hz each with three different steepness values were generated. For each case,

![]() $2000$

PIV images were acquired at a sampling frequency of

$2000$

PIV images were acquired at a sampling frequency of

![]() $0.86$

Hz; thus the total measurement time

$0.86$

Hz; thus the total measurement time

![]() $T_{\textit{PIV}}$

was approximately

$T_{\textit{PIV}}$

was approximately

![]() $39$

min. Using a final pass with

$39$

min. Using a final pass with

![]() $48 \times 48$

pixel interrogation window and a 50 % overlap resulted in a velocity vector spacing of approximately

$48 \times 48$

pixel interrogation window and a 50 % overlap resulted in a velocity vector spacing of approximately

![]() $1.6$

mm. For both cases 2.A and 2.B, PIV measurements were also performed without wave generation to characterise ambient flow conditions, reported in table 2.

$1.6$

mm. For both cases 2.A and 2.B, PIV measurements were also performed without wave generation to characterise ambient flow conditions, reported in table 2.

2.1.3. Experiment 3: onset of regular waves

Cases 3.A and 3.B in tables 1–3 are from Experiment 3. This set of measurements was taken at the highest acquisition frequency in our study (

![]() $15$

Hz) during a

$15$

Hz) during a

![]() $25$

s interval just after the first arrival of regular waves as indicated in figure 2(c). The water depth was

$25$

s interval just after the first arrival of regular waves as indicated in figure 2(c). The water depth was

![]() $0.50$

m, and a slower mean flow of

$0.50$

m, and a slower mean flow of

![]() $U_0=0.19\, \textrm{m s}^{-1}$

was used compared with the other cases (see table 1). The two cases are separated by the different sequences for the active grid. Case 3.A is similar to case 1.B as only vertically orientated grid bars were rotated at a random, top-hat-distributed rotation speed. Similarly for case 3.B, only the vertical grid bars were actuated, made to flap over an angle of

$U_0=0.19\, \textrm{m s}^{-1}$

was used compared with the other cases (see table 1). The two cases are separated by the different sequences for the active grid. Case 3.A is similar to case 1.B as only vertically orientated grid bars were rotated at a random, top-hat-distributed rotation speed. Similarly for case 3.B, only the vertical grid bars were actuated, made to flap over an angle of

![]() $\pm 60^\circ$

about the fully open position during random time intervals of a top-hat-distributed duration between

$\pm 60^\circ$

about the fully open position during random time intervals of a top-hat-distributed duration between

![]() $0.5$

and

$0.5$

and

![]() $1.0$

seconds. (A full list of experimental conditions is found in Appendix A.) No surface plate downstream of the active grid was used in this experiment, and the field of view in the streamwise–vertical plane (see figure 1

c) was centred a distance

$1.0$

seconds. (A full list of experimental conditions is found in Appendix A.) No surface plate downstream of the active grid was used in this experiment, and the field of view in the streamwise–vertical plane (see figure 1

c) was centred a distance

![]() $L_{\textit{FOV}}=8.5$

m downstream of the grid.

$L_{\textit{FOV}}=8.5$

m downstream of the grid.

The wavemaker was actuated at

![]() $f_0=1.4$

Hz. Here, two steepnesses for each flow case are investigated, yielding four different steepness–turbulence combinations. For each of the four combinations,

$f_0=1.4$

Hz. Here, two steepnesses for each flow case are investigated, yielding four different steepness–turbulence combinations. For each of the four combinations,

![]() $32$

ensembles are measured, where the wave probe measurements of one ensemble are shown in figure 2(c). In order to avoid wave breaking at the leading edge of the wave train, the wavemaker stroke is linearly ramped up to the set amplitude over a period of

$32$

ensembles are measured, where the wave probe measurements of one ensemble are shown in figure 2(c). In order to avoid wave breaking at the leading edge of the wave train, the wavemaker stroke is linearly ramped up to the set amplitude over a period of

![]() $6$

seconds.

$6$

seconds.

For the PIV measurements, a single 25-megapixel camera was used to cover the entire water column. Using a

![]() $64\times 64$

pixel interrogation window and a 50 % overlap resulted in a final velocity vector spacing of approximately

$64\times 64$

pixel interrogation window and a 50 % overlap resulted in a final velocity vector spacing of approximately

![]() $3$

mm. The field of view is

$3$

mm. The field of view is

![]() $0.45\, {\rm m}\times 0.5$

m. PIV images were acquired at

$0.45\, {\rm m}\times 0.5$

m. PIV images were acquired at

![]() $f_{\textit{ac}}=15$

Hz. Also here, PIV measurements were performed without wave generation to characterise the ambient flow conditions, reported in table 2. For these background measurements

$f_{\textit{ac}}=15$

Hz. Also here, PIV measurements were performed without wave generation to characterise the ambient flow conditions, reported in table 2. For these background measurements

![]() $2000$

snapshots were captured at

$2000$

snapshots were captured at

![]() $1.0$

Hz.

$1.0$

Hz.

3. Experimental measurements

3.1. Flow and wave characteristics

The measured physical characteristics of mean flow, turbulence and waves are listed in table 2, and some derived quantities we will make use of are quoted in table 3 for convenience.

An assumption of deep water is well satisfied since in all our cases

![]() $k_0h\gtrsim 3.6$

hence

$k_0h\gtrsim 3.6$

hence

![]() $1\gt \sqrt {\tanh (k_0h)}\gt 0.999$

. Here, and henceforth,

$1\gt \sqrt {\tanh (k_0h)}\gt 0.999$

. Here, and henceforth,

![]() $U_0$

is the mean absolute surface speed in the absence of waves (i.e. the mean surface velocity is

$U_0$

is the mean absolute surface speed in the absence of waves (i.e. the mean surface velocity is

![]() $\boldsymbol{U}_0=(-U_0,0,0)$

) and in all our cases the velocity profile is sufficiently depth uniform that vertical shear affects wave dispersion negligibly (e.g. Ellingsen & Li Reference Ellingsen and Li2017). The wavenumber

$\boldsymbol{U}_0=(-U_0,0,0)$

) and in all our cases the velocity profile is sufficiently depth uniform that vertical shear affects wave dispersion negligibly (e.g. Ellingsen & Li Reference Ellingsen and Li2017). The wavenumber

![]() $k_0$

and the wavemaker carrier frequency

$k_0$

and the wavemaker carrier frequency

![]() $f_0$

are related approximately by

$f_0$

are related approximately by

![]() $2\pi f_0 = \sqrt {gk_0} {-} U_0k_0$

, or equivalently

$2\pi f_0 = \sqrt {gk_0} {-} U_0k_0$

, or equivalently

![]() $f_0 = (c(k_0){-}U_0)/\lambda _0$

with

$f_0 = (c(k_0){-}U_0)/\lambda _0$

with

![]() $c(k_0)$

from (1.2) and the wavelength is

$c(k_0)$

from (1.2) and the wavelength is

![]() $\lambda _0=2\pi /k_0$

. We will use the measured (as opposed to derived) value of

$\lambda _0=2\pi /k_0$

. We will use the measured (as opposed to derived) value of

![]() $\lambda _0$

and the wavenumber

$\lambda _0$

and the wavenumber

![]() $k_0$

accordingly. Values for these quantities are listed in tables 2 and 3, respectively. The time it takes for the waves to propagate from wavemaker to the edge of the surface plate is around

$k_0$

accordingly. Values for these quantities are listed in tables 2 and 3, respectively. The time it takes for the waves to propagate from wavemaker to the edge of the surface plate is around

![]() $40$

s for Experiment 1,

$40$

s for Experiment 1,

![]() $25$

s for cases 2.A.1 and 2.B.1,

$25$

s for cases 2.A.1 and 2.B.1,

![]() $56$

s for cases 2.A.2 and 2.B.2 and

$56$

s for cases 2.A.2 and 2.B.2 and

![]() $35$

s for Experiment 3.

$35$

s for Experiment 3.

The root-mean-square (r.m.s.) of the turbulent velocity fluctuation after subtracting the average is defined as

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}_{\textit{rms}}=[u_{\textit{rms}},v_{\textit{rms}}, w_{\textit{rms}}]$

representing the streamwise, spanwise, and vertical components, respectively. The turbulent kinetic energy is as

$\boldsymbol{u}_{\textit{rms}}=[u_{\textit{rms}},v_{\textit{rms}}, w_{\textit{rms}}]$

representing the streamwise, spanwise, and vertical components, respectively. The turbulent kinetic energy is as

![]() $e=({1}/{2}) |\boldsymbol{u}_{\textit{rms}}|^2$

. In cases 2.A–3.B, only

$e=({1}/{2}) |\boldsymbol{u}_{\textit{rms}}|^2$

. In cases 2.A–3.B, only

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

and

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

and

![]() $w_{\textit{rms}}$

are available, so we use instead

$w_{\textit{rms}}$

are available, so we use instead

![]() $e=({1}/{2}) (u_{\textit{rms}}^2+2w_{\textit{rms}}^2)$

, an assumption of cross-plane isotropy, as is the standard convention for grid turbulence (e.g. Comte-Bellot & Corrsin Reference Comte-Bellot and Corrsin1966; Lavoie et al. Reference Lavoie, Burattini, Djenidi and Antonia2005) and was observed for our facility by Jooss et al. (Reference Jooss, Li, Bracchi and Hearst2021). The assumption is not quite satisfied for our flow as table 2 shows for Experiment 1. However, given the inevitable anisotropy of the flow as the free surface is approached (also with no waves) and consequent depth variation of

$e=({1}/{2}) (u_{\textit{rms}}^2+2w_{\textit{rms}}^2)$

, an assumption of cross-plane isotropy, as is the standard convention for grid turbulence (e.g. Comte-Bellot & Corrsin Reference Comte-Bellot and Corrsin1966; Lavoie et al. Reference Lavoie, Burattini, Djenidi and Antonia2005) and was observed for our facility by Jooss et al. (Reference Jooss, Li, Bracchi and Hearst2021). The assumption is not quite satisfied for our flow as table 2 shows for Experiment 1. However, given the inevitable anisotropy of the flow as the free surface is approached (also with no waves) and consequent depth variation of

![]() $e$

closer to the surface than about one integral scale (the blockage layer, see, e.g. Aarnes et al. Reference Aarnes, Babiker, Xuan, Shen and Ellingsen2025), representing turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) by a single number is always a simplified picture. The precise value of

$e$

closer to the surface than about one integral scale (the blockage layer, see, e.g. Aarnes et al. Reference Aarnes, Babiker, Xuan, Shen and Ellingsen2025), representing turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) by a single number is always a simplified picture. The precise value of

![]() $e$

does not significantly affect our conclusions, and given that no simple expression for

$e$

does not significantly affect our conclusions, and given that no simple expression for

![]() $e$

in terms of

$e$

in terms of

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}$

and

$u_{\textit{rms}}$

and

![]() $w_{\textit{rms}}$

can reconcile all cases in Experiment 1, we choose to go with the conventional expression.

$w_{\textit{rms}}$

can reconcile all cases in Experiment 1, we choose to go with the conventional expression.

The mean velocity

![]() $U_0$

was calculated from averaging all streamwise velocities over the lower part of the field of view; averaging was performed over

$U_0$

was calculated from averaging all streamwise velocities over the lower part of the field of view; averaging was performed over

![]() $-12$

cm

$-12$

cm

![]() $\lt z\lt -5$

cm for Experiment 1 and

$\lt z\lt -5$

cm for Experiment 1 and

![]() $-20$

cm

$-20$

cm

![]() $\lt z\lt -10$

cm for Experiments 2 and 3. Full profiles of the Eulerian-mean velocity profiles for all experimental cases may be found in the Supplementary Materials.

$\lt z\lt -10$

cm for Experiments 2 and 3. Full profiles of the Eulerian-mean velocity profiles for all experimental cases may be found in the Supplementary Materials.

When comparing turbulent quantities for the various cases one should bear in mind that these are measured at a fixed position in space, whereas the turbulence becomes gradually weaker as it travels downstream because of dissipation. The change in Eulerian-mean current is an integrated effect of wave–turbulence interactions that occurred upstream, where the turbulence intensity is in general a little higher. This is true of all cases, but because of the lower mean velocity, the turbulence that reaches the field of view in cases 3.A and 3.B has decayed for longer. A detailed study of turbulent decay in our lab with similar flow conditions as Experiment 1 was reported by Jooss et al. (Reference Jooss, Li, Bracchi and Hearst2021). They found that for all cases, once the turbulence is fully developed TKE decays approximately as

![]() $\sim 1/x$

downstream for all cases. Thus, although the absolute values of TKE and Reynolds stresses are different at different positions, their relative magnitudes are expected to be constant. We consider only trends with respect to TKE, and ratios between Reynolds stresses which it seems reasonable to assume are well captured.

$\sim 1/x$

downstream for all cases. Thus, although the absolute values of TKE and Reynolds stresses are different at different positions, their relative magnitudes are expected to be constant. We consider only trends with respect to TKE, and ratios between Reynolds stresses which it seems reasonable to assume are well captured.

In previous experiments by Nepf & Monismith (Reference Nepf and Monismith1991) and Klopman (Reference Klopman1994, Reference Klopman1997), secondary motion in the form of a pair of streamwise rolls were measured when waves were propagated on a current, triggered by the CL2 mechanism. We could measure the cross-plane flow in Experiment 1, and while some weak in-plane mean flow was observed, of the order of

![]() $1$

cm s−1 or less, the pattern was not consistent with a coherent pair of rolls. The resulting convection, in magnitude and direction, would be insufficient to convect boundary-layer turbulence into the near-surface regions where turbulence and waves interact to any noticeable degree. During the travel from grid to measurement position, the vortex force near the boundaries has far less time to accelerate a similar amount of water as in Klopman (Reference Klopman1994) and would likely not have time to develop. It is not perhaps so surprising that secondary flows would be different given that geometrical size and aspect ratios are rather different, and the current’s travel time from grid to measurement point is less than half that in either of the mentioned flows even for our slowest flow in Experiment 3.

$1$

cm s−1 or less, the pattern was not consistent with a coherent pair of rolls. The resulting convection, in magnitude and direction, would be insufficient to convect boundary-layer turbulence into the near-surface regions where turbulence and waves interact to any noticeable degree. During the travel from grid to measurement position, the vortex force near the boundaries has far less time to accelerate a similar amount of water as in Klopman (Reference Klopman1994) and would likely not have time to develop. It is not perhaps so surprising that secondary flows would be different given that geometrical size and aspect ratios are rather different, and the current’s travel time from grid to measurement point is less than half that in either of the mentioned flows even for our slowest flow in Experiment 3.

It was found by Smeltzer et al. (Reference Smeltzer, Rømcke, Hearst and Ellingsen2023) that the turbulent integral length scale, characteristic of the largest turbulent structures, is important for wave–turbulence interactions, especially so for the scatting of waves by turbulence. An advantage of our active-grid turbulence generation is that the integral scale can be varied independently of TKE. The most pertinent integral scale is related to correlation of streamwise turbulent velocity for points separated in the streamwise direction,

![]() $L_x^x$

. Due to differences in the way the experimental data were acquired, no single method for estimating

$L_x^x$

. Due to differences in the way the experimental data were acquired, no single method for estimating

![]() $L_x^x$

can be applied to all cases. Estimating the integral length scales from experimental data uniquely and quantitatively is notoriously difficult, and the various methods in common use produce quantitatively different results. Additional challenges pertain to active-grid turbulence due to the slow spatial decay of the autocorrelation function (Puga & LaRue Reference Puga and LaRue2017; Mora et al. Reference Mora, Muñiz Pladellorens, Riera Turró, Lagauzere and Obligado2019). In Experiment 1, the integral scale was estimated with a zero-crossing method as described by Mora & Obligado (Reference Mora and Obligado2020), and we used the same method to calculate the integral scale for Experiment 3, as listed in table 2. Since the data in Experiment 2 have low time resolution the same method cannot be applied there, and using another, spatially based method would not give directly comparable numbers, so we provide no integral scale for Experiment 2. We note that integral scales are significantly shorter in Experiment 3 than in Experiment 1 at similar turbulence levels, which can be explained by the lower mean-flow velocity

$L_x^x$

can be applied to all cases. Estimating the integral length scales from experimental data uniquely and quantitatively is notoriously difficult, and the various methods in common use produce quantitatively different results. Additional challenges pertain to active-grid turbulence due to the slow spatial decay of the autocorrelation function (Puga & LaRue Reference Puga and LaRue2017; Mora et al. Reference Mora, Muñiz Pladellorens, Riera Turró, Lagauzere and Obligado2019). In Experiment 1, the integral scale was estimated with a zero-crossing method as described by Mora & Obligado (Reference Mora and Obligado2020), and we used the same method to calculate the integral scale for Experiment 3, as listed in table 2. Since the data in Experiment 2 have low time resolution the same method cannot be applied there, and using another, spatially based method would not give directly comparable numbers, so we provide no integral scale for Experiment 2. We note that integral scales are significantly shorter in Experiment 3 than in Experiment 1 at similar turbulence levels, which can be explained by the lower mean-flow velocity

![]() $U_0$

.

$U_0$

.

Several practical aspects in evaluation of the wave and flow characteristics reported in table 2 differed for the three experiments, and are described in further detail below.

3.1.1. Wave group measurements (Experiment 1)

The mean flow and turbulence statistics without waves presented in table 2 were evaluated over the first interval, where any influence from waves can be assumed to be negligible. The mean flow in the negative

![]() $x$

-direction had approximately constant (absolute) value

$x$

-direction had approximately constant (absolute) value

![]() $U_0$

, found from averaging as described above. A small spanwise and vertical mean velocity was found, everywhere below

$U_0$

, found from averaging as described above. A small spanwise and vertical mean velocity was found, everywhere below

![]() $1$

cm s−1, mostly much less, which we attribute to the channel flow conditioning not being perfect (achieving a perfectly straight and uniform flow in a channel of our size is very challenging). Notably, unlike the streamwise velocity, the cross-plane velocities did not change after the passage of the wave group, which implies that there is negligible contribution secondary flow due to wave–current interactions near the sidewalls mentioned above.

$1$

cm s−1, mostly much less, which we attribute to the channel flow conditioning not being perfect (achieving a perfectly straight and uniform flow in a channel of our size is very challenging). Notably, unlike the streamwise velocity, the cross-plane velocities did not change after the passage of the wave group, which implies that there is negligible contribution secondary flow due to wave–current interactions near the sidewalls mentioned above.

The characteristic peak wave amplitude

![]() $a_{{p}}$

and the observed group temporal width

$a_{{p}}$

and the observed group temporal width

![]() $\tau$

were estimated from the ensemble-averaged amplitude envelope of the wave groups as measured by the probes near the SPIV/LIF laser sheet as seen in figure 2(b). The average envelope was fitted to a Gaussian function of the form

$\tau$

were estimated from the ensemble-averaged amplitude envelope of the wave groups as measured by the probes near the SPIV/LIF laser sheet as seen in figure 2(b). The average envelope was fitted to a Gaussian function of the form

\begin{equation} a(t) = a_{{p}} \exp\! \left [-\frac {(t-t_{{p}})^2}{2\tau ^2}\right ]\!, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} a(t) = a_{{p}} \exp\! \left [-\frac {(t-t_{{p}})^2}{2\tau ^2}\right ]\!, \end{equation}

with

![]() $t_{{p}}$

the temporal location of the group peak. The peak wave steepness is

$t_{{p}}$

the temporal location of the group peak. The peak wave steepness is

![]() $k_0a_{{p}}$

.

$k_0a_{{p}}$

.

We define an intrinsic temporal group width

![]() $\tau _0$

, listed in table 3 as

$\tau _0$

, listed in table 3 as

with

![]() $c_g$

defined in (1.2). The intrinsic temporal group width is expressed in a reference frame without mean flow and reflects the time scale during which the ambient turbulence interacts with the wave groups.

$c_g$

defined in (1.2). The intrinsic temporal group width is expressed in a reference frame without mean flow and reflects the time scale during which the ambient turbulence interacts with the wave groups.

3.1.2. Measurements with regular waves (Experiments 2 and 3)

The ambient flow statistics were evaluated from PIV measurements acquired without waves. Similarly to Experiment 1, the mean-flow profile varied only slightly across the measurement plane, and a representative absolute value

![]() $U_0$

is given in table 2.

$U_0$

is given in table 2.

The wave steepness

![]() $ak_0$

was calculated using the average wave amplitude from the wave probe measurements in the proximity of the PIV measurement location. The amplitude of each individual wave oscillation varied slightly during the experiments, especially in cases with the highest level of turbulence, likely due to wave–turbulence interactions (e.g. Smeltzer et al. Reference Smeltzer, Rømcke, Hearst and Ellingsen2023). The variation is not of central interest to the present study, and thus only the mean steepness value is reported.

$ak_0$

was calculated using the average wave amplitude from the wave probe measurements in the proximity of the PIV measurement location. The amplitude of each individual wave oscillation varied slightly during the experiments, especially in cases with the highest level of turbulence, likely due to wave–turbulence interactions (e.g. Smeltzer et al. Reference Smeltzer, Rømcke, Hearst and Ellingsen2023). The variation is not of central interest to the present study, and thus only the mean steepness value is reported.

The regular waves were present throughout the entire test section during the experiments. The grid-generated and measured turbulence thus interacted with the waves over a length

![]() $L_{\textit{FOV}}$

as given in §§ 2.1.2 and 2.1.3, with associated interaction time

$L_{\textit{FOV}}$

as given in §§ 2.1.2 and 2.1.3, with associated interaction time

![]() $T_{\textit{int}}=L_{\textit{FOV}}/U_0$

. The frequency at which turbulence encounters waves, i.e. as seen by the moving flow, equals the intrinsic wave frequency (in Hz)

$T_{\textit{int}}=L_{\textit{FOV}}/U_0$

. The frequency at which turbulence encounters waves, i.e. as seen by the moving flow, equals the intrinsic wave frequency (in Hz)

3.2. Measured change in Eulerian-mean velocity

The measured changes in Eulerian-mean velocities presented below are of the order of millimetres per second, yet, while this is the same order of magnitude as our PIV measurement accuracy, one should bear in mind that the variance of an average from hundreds of independent measurements is far lower than that of single measurements. It is crucial that a careful analysis of errors and statistical convergence be performed in order to establish confidence that our results are accurate and reliable. In Appendix B, we report results of these tests, supported by further data in the Supplementary Materials.

3.2.1. Velocity change after the passage of wave groups (Experiment 1)

We now consider the measured Eulerian-mean velocity change for Experiment 1, i.e. cases 1.A–1.D. Vertically sheared flows in our laboratory have been found to be stable and therefore the wave-modified Eulerian-mean velocity profile remains close to unchanged throughout interval 3 (also found to be true for strongly sheared currents, see § 4 of Pizzo et al. Reference Pizzo, Lenain, Rømcke, Ellingsen and Smeltzer2023). In figure 3(a) we show as an example the mean streamwise velocity profiles for case 1.D during the three measurement intervals, denoted

![]() $U_I(z)$

for intervals

$U_I(z)$

for intervals

![]() $I = \{1,2,3\}$

(see figure 2

b). As can be seen, the mean-flow speed had increased in the direction opposite to wave propagation after the passage of the wave groups. Similar plots for all cases are provided in the Supplementary Materials. Error bars are omitted from the figure for reasons of visibility, but discussed in Appendix B. The net Eulerian-mean-flow change

$I = \{1,2,3\}$

(see figure 2

b). As can be seen, the mean-flow speed had increased in the direction opposite to wave propagation after the passage of the wave groups. Similar plots for all cases are provided in the Supplementary Materials. Error bars are omitted from the figure for reasons of visibility, but discussed in Appendix B. The net Eulerian-mean-flow change

![]() $\Delta U=U_3 {-} U_1$

is shown in figure 3(b) for flow cases 1.A–1.D as expressed in the legend. For all cases,

$\Delta U=U_3 {-} U_1$

is shown in figure 3(b) for flow cases 1.A–1.D as expressed in the legend. For all cases,

![]() $\Delta U\lt 0$

near the surface, and decays to small absolute values at depths

$\Delta U\lt 0$

near the surface, and decays to small absolute values at depths

![]() $|k_0z|\gtrsim 1$

.

$|k_0z|\gtrsim 1$

.

Figure 3. Change in Eulerian-mean current due to the passage of a wave group. The waves travelled in the positive

![]() $x$

-direction, against the current. (a) An example of mean streamwise velocity depth profile before the arrival of a wave group,

$x$

-direction, against the current. (a) An example of mean streamwise velocity depth profile before the arrival of a wave group,

![]() $U_1(z)$

, and after the group has passed,

$U_1(z)$

, and after the group has passed,

![]() $U_3(z)$

, here for case 1.D; (b) mean streamwise velocity difference

$U_3(z)$

, here for case 1.D; (b) mean streamwise velocity difference

![]() $\Delta U = U_3-U_1$

as a function of depth for the flow cases of Experiment 1. Error bars are omitted for visibility – see analysis in Appendix B; (c) the slope of

$\Delta U = U_3-U_1$

as a function of depth for the flow cases of Experiment 1. Error bars are omitted for visibility – see analysis in Appendix B; (c) the slope of

![]() $\Delta U(z)$

relative to the Stokes drift gradient (a prime denotes derivation with respect to

$\Delta U(z)$

relative to the Stokes drift gradient (a prime denotes derivation with respect to

![]() $z$

). Light smoothing (moving average with window size

$z$

). Light smoothing (moving average with window size

![]() $8$

mm) was applied to the curves in panel (c) for better visibility.

$8$

mm) was applied to the curves in panel (c) for better visibility.

Interestingly,

![]() $\Delta U$

clearly depends on the level of ambient turbulence; while the waves have approximately equal properties in cases 1.A, 1.B, 1.C.1 and 1.D, the velocity change is far higher at the highest turbulence level (case 1.D) than at the lowest level (case 1.A), with the intermediate cases 1.B and 1.C.1 in between. Moreover, comparing cases 1.C.1 and 1.C.2 where two wave steepnesses are tested on the same turbulent current indicates a positive correlation between

$\Delta U$

clearly depends on the level of ambient turbulence; while the waves have approximately equal properties in cases 1.A, 1.B, 1.C.1 and 1.D, the velocity change is far higher at the highest turbulence level (case 1.D) than at the lowest level (case 1.A), with the intermediate cases 1.B and 1.C.1 in between. Moreover, comparing cases 1.C.1 and 1.C.2 where two wave steepnesses are tested on the same turbulent current indicates a positive correlation between

![]() $k_0a_{{p}}$

and current change

$k_0a_{{p}}$

and current change

![]() $\Delta U$

. Put together, the results in figure 3(b) provide a strong indication that the change in current is due to an interaction between waves and turbulence.

$\Delta U$

. Put together, the results in figure 3(b) provide a strong indication that the change in current is due to an interaction between waves and turbulence.

We can exclude the possibility that the measured

![]() $\Delta U$

is due to the Eulerian return flow under groups of waves, as measured by van den Bremer et al. (Reference van den Bremer, Whittaker, Calvert, Raby and Taylor2019). The return flow follows the group, i.e. it is very weak in intervals 2 and 3 which lie outside the main group itself. It is also near-uniform in depth, whereas the current measured in figure 3(a) is strongly depth dependent.

$\Delta U$

is due to the Eulerian return flow under groups of waves, as measured by van den Bremer et al. (Reference van den Bremer, Whittaker, Calvert, Raby and Taylor2019). The return flow follows the group, i.e. it is very weak in intervals 2 and 3 which lie outside the main group itself. It is also near-uniform in depth, whereas the current measured in figure 3(a) is strongly depth dependent.

It is instructive to plot the ratio between

![]() ${\rm d}(\Delta U)/{\rm d} z$

and

${\rm d}(\Delta U)/{\rm d} z$

and

![]() $-{\rm d} u_s/{\rm d} z$

as a function of

$-{\rm d} u_s/{\rm d} z$

as a function of

![]() $z$

, shown in figure 3(c), because it gives some indication of how far the turbulent flow has transitioned towards a new, quasi-equilibrium state. We will later present theory and evidence that at the end of the ‘spin-up’ period, this ratio should, in the final state, be approximately equal to

$z$

, shown in figure 3(c), because it gives some indication of how far the turbulent flow has transitioned towards a new, quasi-equilibrium state. We will later present theory and evidence that at the end of the ‘spin-up’ period, this ratio should, in the final state, be approximately equal to

![]() $u_{\textit{rms}}^2/w_{\textit{rms}}^2$

nearest the surface. Since our bulk turbulence is slightly anisotropic (in the cases reported in Jooss et al. (Reference Jooss, Li, Bracchi and Hearst2021),

$u_{\textit{rms}}^2/w_{\textit{rms}}^2$

nearest the surface. Since our bulk turbulence is slightly anisotropic (in the cases reported in Jooss et al. (Reference Jooss, Li, Bracchi and Hearst2021),

![]() $1.2\lesssim u_{\textit{rms}}^2/w_{\textit{rms}}^2\lesssim 1.4$

), a final current change

$1.2\lesssim u_{\textit{rms}}^2/w_{\textit{rms}}^2\lesssim 1.4$

), a final current change

![]() $|\Delta U|\gtrsim |u_s|$

is expected nearest the surface. We shall later see that in the regular-wave cases where the equilibrium is likely reached, this relation holds well. Since none of the changes in currents in cases 1.A–1.D are close to reaching these values, it seems that the passing of the wave group has not led to a wave–turbulence interaction of sufficient duration for a final state to be reached, and the flow is still relatively early in the ‘spin-up’ stage.

$|\Delta U|\gtrsim |u_s|$

is expected nearest the surface. We shall later see that in the regular-wave cases where the equilibrium is likely reached, this relation holds well. Since none of the changes in currents in cases 1.A–1.D are close to reaching these values, it seems that the passing of the wave group has not led to a wave–turbulence interaction of sufficient duration for a final state to be reached, and the flow is still relatively early in the ‘spin-up’ stage.

There are at least two striking observations to make in figure 3(c). First, with the exception of the low-turbulence case, 1.A, the ratio between the slopes is close to constant with depth, which illustrates that

![]() $\Delta U \sim \exp (2k_0z)$

near the surface in these cases. The scaling is not perfect, particularly at the shallowest depths; this should not be surprising since the depth dependence of wave–turbulence interaction should scale not only with the wavelength, but also the turbulent integral length scale, which delimits the vertical extent of the topmost layer where the kinematic boundary condition at the surface begins to limit the vertical extent of turbulent eddies (the blocking effect, see, e.g. Teixeira & Belcher Reference Teixeira and Belcher2002). Second, while the value of

$\Delta U \sim \exp (2k_0z)$

near the surface in these cases. The scaling is not perfect, particularly at the shallowest depths; this should not be surprising since the depth dependence of wave–turbulence interaction should scale not only with the wavelength, but also the turbulent integral length scale, which delimits the vertical extent of the topmost layer where the kinematic boundary condition at the surface begins to limit the vertical extent of turbulent eddies (the blocking effect, see, e.g. Teixeira & Belcher Reference Teixeira and Belcher2002). Second, while the value of

![]() $\Delta U(z)$

after the passing of a group depends strongly on the turbulence level and steepness, there is no such trend for the relative slope (

$\Delta U(z)$

after the passing of a group depends strongly on the turbulence level and steepness, there is no such trend for the relative slope (

![]() $-\Delta U^{\prime }(z)/u_s^{\prime }(z)$

), case 1.A excepted.

$-\Delta U^{\prime }(z)/u_s^{\prime }(z)$

), case 1.A excepted.

In § 4.4 we will develop a RDT model describing the early onset of wave–turbulence interaction, which we can compare with the measurements in figure 3(b), given this evidence that the combined wave/turbulence flow is still far from fully developed in Experiment 1.

In conclusion, the evidence suggests that the change in Eulerian-mean current observed in our experiments is due to wave–turbulence interaction, and increases with increasing turbulence and increasing wave steepness.

3.3. Velocity change under regular waves (Experiments 2 and 3)

Cases 2.A–3.B all consider turbulence interacting with regular (i.e. continuous and periodic) waves. For cases 2.A.1–2.B.2, we evaluate the mean streamwise velocity in the presence of waves, and subtract off the mean velocity profile from the ambient flow case without waves. This velocity difference we define as

![]() $\Delta U(z)$

. Although the flow is wavy, the time series is long enough for the Eulerian-mean current, averaged over all

$\Delta U(z)$

. Although the flow is wavy, the time series is long enough for the Eulerian-mean current, averaged over all

![]() $2000$

PIV images, to be well converged in the sense that further measurements would affect it insignificantly. See details in Appendix B.

$2000$

PIV images, to be well converged in the sense that further measurements would affect it insignificantly. See details in Appendix B.

The turbulent current is affected by the waves during the time it takes it to traverse the test section, a distance

![]() $L_{\textit{FOV}}$

as defined in §§ 2.1.2 and 2.1.3. The interaction time is thus

$L_{\textit{FOV}}$

as defined in §§ 2.1.2 and 2.1.3. The interaction time is thus

![]() $T_{\textit{int}}=L_{\textit{FOV}}/U_0$

, approximately

$T_{\textit{int}}=L_{\textit{FOV}}/U_0$

, approximately

![]() $29$

s for Experiment 2 and

$29$

s for Experiment 2 and

![]() $46$

s for Experiment 3, the latter having a slower flow speed. This corresponds to a number of wave cycles,

$46$

s for Experiment 3, the latter having a slower flow speed. This corresponds to a number of wave cycles,

![]() $T_{\textit{int}}/T_0,$

between

$T_{\textit{int}}/T_0,$

between

![]() $36$

(cases 2.A and 3.A) and

$36$

(cases 2.A and 3.A) and

![]() $83$

listed in table 4. Due to the slower flow speed. Cases 3.A and 3.B interact for considerably longer than 2.A and 2.B, both in terms of absolute time (in seconds) and in terms of number of intrinsic wave periods

$83$

listed in table 4. Due to the slower flow speed. Cases 3.A and 3.B interact for considerably longer than 2.A and 2.B, both in terms of absolute time (in seconds) and in terms of number of intrinsic wave periods

![]() $T_0$

, i.e.

$T_0$

, i.e.

![]() $T_{\textit{int}}/T_0$

is the number of wave cycles that the turbulence has encountered.

$T_{\textit{int}}/T_0$

is the number of wave cycles that the turbulence has encountered.

Table 4. Derived wave quantities for use in RDT analysis. For cases 1.A–1.D,

![]() $T_{\textit{int}}=\sqrt {\pi }\tau _0$

is used with

$T_{\textit{int}}=\sqrt {\pi }\tau _0$

is used with

![]() $\tau _0$

from (3.2), while for cases 2.A–3.B,

$\tau _0$

from (3.2), while for cases 2.A–3.B,

![]() $T_{\textit{int}}=L_{\textit{FOV}}/U_0$

;

$T_{\textit{int}}=L_{\textit{FOV}}/U_0$

;

![]() $\beta _{{f}}(0)$

is found from (4.28) and (4.29) for groups and regular waves, respectively. Note that it is related to

$\beta _{{f}}(0)$

is found from (4.28) and (4.29) for groups and regular waves, respectively. Note that it is related to

![]() $T_{\textit{int}}$

via (4.33).

$T_{\textit{int}}$

via (4.33).

In figure 4 we show

![]() $\Delta U(z)$

for cases 2.A–3.B, where the different wave steepness values

$\Delta U(z)$

for cases 2.A–3.B, where the different wave steepness values

![]() $ak_0$