Introduction

The year 2019, with several government crises and two elections, was a busy period in Finland. The unpopular Sipilä government collapsed in early 2019 due to social services reform failure. Parliamentary elections were held as scheduled in April 2019. The ‘three big parties’ scheme was renewed, albeit with a slightly different make up, as the True Finns/Perussuomalaiset (PS; officially, the Finns Party) took the place of the Centre Party/Keskusta (KESK) in the usual threesome of the Social Democratic Party/Sosialidemokraattinen puolue (SDP) and the National Coalition/Kansallinen Kokoomus (KOK), with almost the same results. Antti Rinne (SDP) formed a five‐party centre‐left government, but by the end of the year, he had to step down, and deputy party leader Sanna Marin was elected as the world's youngest Prime Minister and the third female Prime Minister of Finland. The government acted fast to reverse some of the austerity measures of the previous government, especially those related to labour relations. In the European Parliament (EP) elections, a pro‐European Union stance was dominant: the opposition party National Coalition (European People's Party, EPP) and Greens/Vihreät (VIHR) who made history as the second largest party. The PS demonstrated that they could reach similar levels of support as before the leadership change and splinter (Palonen Reference Palonen2018, Reference Palonen2019).

Election report

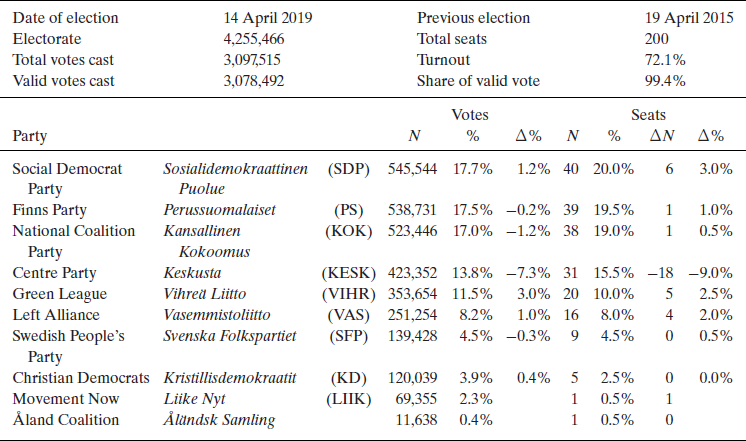

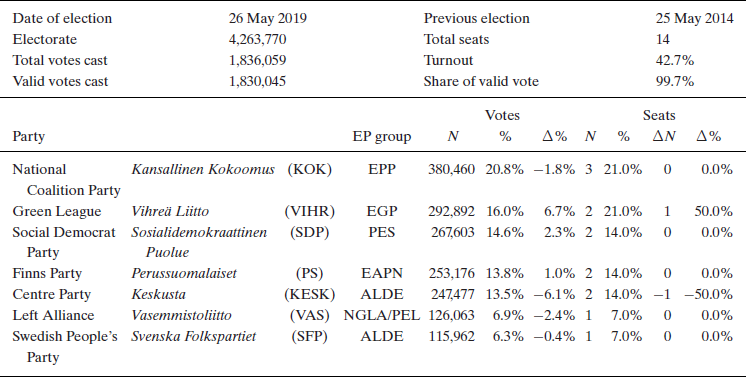

The central elections were the parliamentary elections in April. However, the EP elections were held only six weeks later in May, with quite different results. Both elections demonstrated that the traditional three big parties’ paradigm in Finnish politics had finally broken due to challenges from both the populist right and the Greens to the rotating power between the SDP, NC and Centre (Borg Reference Borg2019). The elections in 2019 demonstrated not only that the power of the SDP and Centre were not what they used to be, but also that the Finns Party, which had split in 2017 under new leadership, was able to reach its previous support levels. The Greens made their record success and confirmed nationwide presence with 11.5 per cent of the vote in the parliamentary elections (Raunio Reference Raunio2020). Both elections’ results signal a further fragmentation of the party system in a proportional electoral system traditionally dominated by three parties.

In the EP elections, contrary to the parliamentary ones, the NC was the largest party, with three seats and 20.8 per cent of support. In a historic result, the Greens emerged as the second‐largest party with 2 + 1 seats (referring to the seat Finland gained after the UK's Brexit) and 16 per cent of the vote (+6.7 per centage points). The candidates for NC were established MEPs, while the Greens had the most prominent candidates. Heidi Hautala, vice‐president of the EP and with MEP experience since the 1990s, and former party leader Ville Niinistö, were joined by Alviina Alametsä of the millennial generation. The SDP (14.6 percent), PS (13.8 per cent) and KESK (13.5 per cent) each received two seats. The new government parties Left Alliance/Vasemmistoliitto (VAS) and Swedish People's Party/Svenska Folkspartiet (SFP) gained one seat each. The SDP list also included a former party leader and sitting MEP. MEPs for the Finns Party on the open list were the most radical edge of the party: a former presidential candidate Laura Huhtasaari and a maverick politician from central Finland, Teuvo Hakkarainen (Palonen Reference Palonen2019). The turnout was significantly lower than in the parliamentary elections at 40.8 per cent, which explains the success of the pro‐EU parties. Before the EP elections, the #Ibizagate scandal involving Austrian FPÖ leader Heinz‐Christian Strache and Russian oligarchs highlighted Russian influence on the populist parties that the PS had strongly associated themselves with. This may have decreased the PS supporters’ enthusiasm for voting in the EP elections.

Parliamentary elections

One‐sixth of the Parliament, 35 parliamentarians of the 200 strong Eduskunta, decided not to renew their mandate in 2019 elections. There were 76 new faces in Parliament after the election, and the average parliamentarian was 46 years. The share of women set a historical record, with 93 parliamentarians being women. Three parties – SDP, PS and KOK – all made it within 17.0–17.8 per cent of the vote, and within one seat difference, the SDP receiving 40 seats. The KESK had its smallest share of the vote (13.8 per cent) in more than a century, losing 18 seats and retaining only 31. The failure of social and healthcare reform impacted the KESK's results, with elderly care in particular having been politicized, and problems were revealed in the private sector whom the government was proposing as the solution for the future growth in social and healthcare costs.

The opposition position lifted the SDP and the PS alike. The mid‐size parties Greens and VAS used their opposition position and the salience of climate on the political agenda and increased their share of the vote and seats by one‐fourth each. The anti‐climate theme was raising votes for the PS. The small parties SFP and Christian Democrats/Kristillisdemokraatit (KD) retained their seats. The Åland island independent representative was re‐elected. Movement Now/Liike Nyt (LIIK) received one seat.

Under Jussi Halla‐aho's leadership, the PS managed to generate distance from the splinter group Blue Reform/Sininen Tulevaisuus (SIN), with their five ministers including Timo Soini, the former emblematic leader of the PS. The SPD suffered a loss of credibility as Rinne returned from sick leave to take up the reins of the party (see below, Political party report): his rhetoric included a ‘tax on meat’ and on diesel cars, which were not well received outside urban centres. The PS was the only party sceptical of the need to react to climate change and it was boosted by demonization (Arter Reference Arter2020). Also, the question of sexual crimes by asylum seekers sparked by incidents in Oulu was still reflected in the PS rhetoric (Palonen Reference Palonen2019). The PS splinter Blue Reform failed in the Eduskunta elections, and did not take part in the EP elections. A new economically liberal party, LIIK, was successful in the electoral district where the former TF party leader Soini had gained a lot of personal votes in previous elections, with LIIK party leader Harry Harkimo previously an MP for KOK. His son narrowly missed election in Helsinki.

Cabinet report

In early 2019, the Sipilä government was experiencing major setbacks with its chosen key policy and consequently declining popular support both among those who supported and those who opposed the policy. The Sipilä government was determined to push through a social and welfare reform together with regional reform. The reform sought to decrease social and healthcare services costs by €3 billion. It was a very divisive issue, and as it was clear it could not be implemented before a new parliamentary term in April, Juha Sipilä resigned on 8 March. He and the ministers continued as a caretaker government until the elections and a new government was formed. One of the emblematic and, hence, unpopular ministers Anne Berner, who had sought to introduce more market logics to the field of transport, resigned to take a position in the banking sector in Sweden. Alongside the social and healthcare reforms, declining transport capacity and rising costs were also felt in the regions.

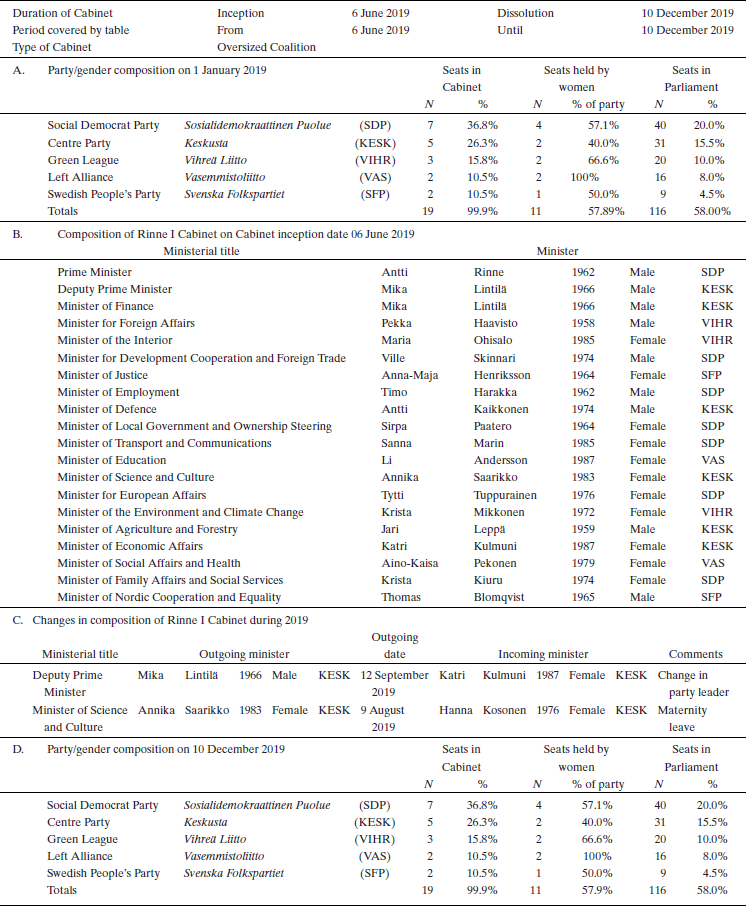

The negotiations to form the Rinne government were finally between five parties. The previous prime ministerial party Centre continued in government despite its electoral losses, enabling Rinne to form a centre‐left government with the Greens, the Left Alliance and the Swedish People's Party. The programme emphasized a ‘socially, economically and ecologically sustainable society’ and was in tune with the climate consciousness that had sparked particularly during the election spring (Valtioneuvosto Reference Valtioneuvosto2019). The new government tackled the history of austerity associated with the government of Juha Sipilä. The Rinne government promised to create 60,000 new jobs for a 75 per cent employment rate, the stability of the public economy by 2023, a decrease in inequality and difference in income, and a roadmap for an emissions‐free Finland. It further emphasized skills, education, work and enterprise, the Nordic welfare model and social responsibility. The international role of Finland was stressed. In economic policy, the government line transformed to a more progressive one, which also was politicized in Eduskunta. The Cabinet took their oath well in advance of their first hurdle: Finland's presidency of the European Union.

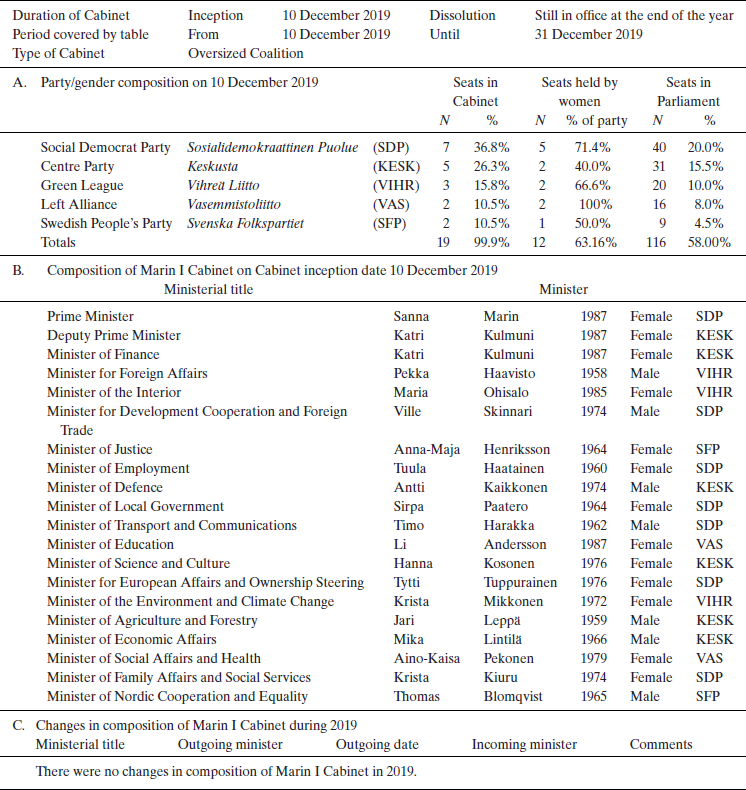

However, the government was short‐lived and before the six‐month period of presidency was over, Rinne passed the torch and the government programme to his party's vice‐chair, Sanna Marin (b. 1985). Rinne (b. 1962) had a background in the labour movement, and his leadership style had been contested. The Prime Minister and the government were becoming increasingly unpopular, just as their predecessor was before the elections in April 2019. By the end of 2019, two crises hit the government – the previous government's leading party, Centre, was at the core of this: the newly elected Katri Kulmuni (b. 1987), the Deputy Prime Minister in Marin's generation, without much further explanation, expressed the view that KESK did not trust Prime Minister Rinne.

The crisis was about the state‐owned postal services company Posti, which the previous government had sought to turn into a private enterprise model, while the basic salaries of the postal workers were to be shrunk. Although the government and the policy had changed, the company leadership pushed the previous agenda. The minister responsible, Sirpa Paatero (SDP), did not manage to veto the plans of moving from one collective labour agreement to another, but she also claimed she did not support it. For Rinne and the party, this was a problem, and the more it became his problem, the more the way in which the crisis was handled was an issue. In the first days of December, the actions of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pekka Haavisto (Greens), in relation to a situation in al‐Hol refugee camp was contested by a senior civil servant: this was a debate about the authority of a minister versus top‐ranking civil servants, as well as about the treatment of refugees, especially the Islamic–Finnish citizens, mothers and their children, in the Syrian camp. Just before this, Paatero resigned before a vote of confidence (interpellation) took place in Eduskunta. Rinne resigned a few days later, and his party started looking for a new Prime Minister.

In this government crisis situation, the courting of opposition parties to form a radically new government was short and was made public by the national broadcasters, but dismissed by the then vice‐chair Marin and Kulmuni in an emblematic encounter of the millennials and the middle‐aged opposition leaders Petteri Orpo (NC) and Jussi Halla‐aho (PS) in the national broadcasters, YLE A‐studio on 3 December 2019. The new government was formed by Sanna Marin, who won the SDP contest (see below in Political party report). Marin received support from the Rinne government partners and her government adopted the Rinne programme (Valtioneuvosto Reference Valtioneuvosto2020). Ministerial shuffles were minimal. It had, however, a huge impact on Finland's international visibility, as Marin was the world's youngest Prime Minister and led a government where the leading posts of all the parties were held by women, most of them of Marin's own generation.

Parliament report

The Finnish Parliament saw heightened debates as the outgoing Parliament discussed social and health services reform issues, and labour laws, and the new government programme involved implementing policies that also addressed previous legislation. One of the key moments in early 2019 was a parliamentary interpellation of all the opposition parties on the elderly care situation in Finland on 6 February and which also brought to the limelight the deputy leader of the largest opposition party SD, Marin, as she now received a front position and media attention amongst critics politicizing the government's key policy that would have entailed a push for private social and healthcare services. Although the government gained the trust of the Parliament (99–88), this vote encapsulated the distrust of the opposition in a reform that intertwined regional governance structure with healthcare reform, which ultimately lead to the resignation of the Sipilä government.

The elections brought in new parliamentarians for some political parties, with the PS, the Green League and VAS groups significantly expanded and renewed by newcomers. The new Parliament's speakers after the government was elected became Matti Vanhanen (KESK), a former Prime Minister and party leader (2003–10), with deputies Tuula Haatainen (SDP), a former minister, and Juho Eerola (PS). This was debated, as the PS was the second largest party in Parliament based on seats. Representative of the second‐largest governmental party, Vanhanen commented on the transformed situation in Finnish politics of having several new middle‐sized parties rather than three large parties, and proposed that a third deputy speaker could be chosen. Now KOK, as the third‐largest party, did not get a speaker role. Hate speech was discussed in the opening event, where Eerola commented that claims of hate speech could violate freedom of speech. The new Parliament for the first time positioned the Finns Party to the right‐most corner of the horseshoe format of Eduskunta’s debating chamber. As they were a successor party of the Finnish Rural Party/Suomen Maaseudun Puolue (SMP), which in turn was a splinter from the Centre party's predecessor in the 1950s, they had been seated in the centre of Eduskunta. The new seating reflected an interpretation of a loss of SMP heritage with the loss of the former leadership in 2017 and the self‐alignment with the radical right populists in the European parliamentary election campaign that was taking place at the same time. One of the politicized debates became MP Juha Mäenpää’s (PS) comment on the Rinne government programme in June where he complimented the government for taking an issue with invasive species, and likened asylum seekers to them.

Parliamentarians in the new Parliament were discussed: two PS MPs were running in the EP elections and were elected as MEPs. This had a minor effect on the composition of Parliament, but was also discussed as a problem for voters in the Finnish system open‐party lists: first, having elected someone to a national role, and then the same people would be leaving for Brussels. The biggest scandal in 2019 was related to SDP MP Hussein Al‐Taee, a politician with an Iraqi refugee background. After his election to Eduskunta, a Kurdish activist contested Al‐Taee's dated Facebook posts as pro‐Iran and anti‐Semitic. This questioned Al‐Taee's neutral role in conflict management, his background career, and was discussed widely in the press and also within the SDP, where these positions were not known. Another scandal was around Päivi Räsänen, MP for the KD, who critically tweeted of Helsinki Pride as promoting sin and shame while the Church also took part in this. Alongside Juha Mäenpää, these three cases of parliamentarians were taken for police pre‐investigation in the summer of 2019. Another text by Räsänen from 2004 was put under investigation as an anti‐gay statement in November. Freedom of speech, social media and retroactive investigations was one of the issues the Finnish Parliament faced in 2019.

The new Parliament assessed the liability of the government in matters related to labour laws initiated by KOK and actions related to the repatriation of al‐Hol refugees, initiated by the PS. The citizen initiatives discussed related to access to mental health therapy, measures to tackle alienating school experiences and daylight savings; rape, sexual crimes and mutilation; mining legislation, pyrotechnics, forestry on state‐owned land and net fishing in the Saimaa ring seal habitat.

Political party report

In political leadership, a takeover by millennial women continued: two parties in the new government changed their leaders, Centre and SDP, and followed with a millennial takeover. In this generation Maria Ohisalo (b. 1985, VIHR) in 2019 and Li Andersson (b. 1987, VAS) in 2016 had been elected as party leaders. As the SDP leader Antti Rinne fell ill in Spain after Christmas 2018 and was hospitalized for several weeks, the first vice‐chair of the party Sanna Marin took responsibility for the party leadership and the limelight in election debates in the early part of campaigning. When Rinne returned to the reins, not everyone was convinced. The party narrowly became the largest in Eduskunta.

The Sipilä government's failure had a toll on the renewed party: none of the parliamentarians had served in the role in the 1980s or before. Post‐election survey results show that while the choice of leadership was important to 31 per cent of the voters in 2015 when Sipilä led the party from the opposition to a landslide and the premiership in 2019, this was only 16 per cent (Isotalo et al. Reference Isotalo, Järvi, von Schoultz and Söderlund2019). The choice of a new party leader had been discussed already in April. One of the strong female contenders for the post, Annika Saarikko (b. 1983), then declined on the basis of her pregnancy. In September, Katri Kulmuni received 1092 votes, overtaking Antti Kaikkonen (b. 1974, 829 votes). Marin had a tighter fight, despite her popular support, and narrowly overtook the male contender Antti Lindtman (b. 1982) with votes 32–29. These tight contests that brought millennial women to power set the tone for the year.

Meanwhile, in the opposition both before and after the 2019 elections, the PS consolidated their support and position as one of the key parties in Finnish politics even under new leadership. In early 2019, they were moving tight to the European populist parties wagons, and expanded their policy positions from migration and anti‐government rhetoric to support the Finnish way of life and oppose climate measures. By December, the PS had gained a record popular support in the polls: 24.3 per cent. At that point, the KOK was the second‐largest with 18.6 per cent, Greens at 13.9 per cent and SDP at 13.2 per cent. The Marin effect did not yet affect the SDP, and Katri Kulmuni did not receive new support for her party. At her election, Kulmuni had set the target of 20 per cent support: with 10.6 per cent at the polls in December, she was up for a challenge to double it.

The newly elected LIIK registered as a party in the autumn of 2019. While the PS had been befriending Heinz‐Christian, Matteo Salvini and Marine Le Pen, the LIIK had been inviting key figures of the Italian Five Star Movement to Finland and to their campaign launch. The populist element of the KOK defecting businessman Hjallis Harkimo and sports personality was likened to ‘celebrity populism’ (Bartoszewicz Reference Bartoszewicz2019). Of other social movements in the Italian style, the Finnish equivalent of the Sardines/Sardelles was established in the end of 2019: Silakkaliike started on social media platforms from meetings with the Italian Sardines and with those disaffected with politics and emerging hate speech and climate scepticism. As with the LIIK originally, they explicitly argued that they are not a political party, but they are worth mentioning as an emerging political force and they illustrate the discursive contestation and the Finns Party's increasing support.

Institutional change report

The major policy changes of the Sipilä government would have brought regional elections and elected representatives alongside social and healthcare reform. This was discontinued in its planned format, which required private sector involvement in the process of sourcing welfare services. The removal of the earlier implemented active model of employment that required the monitoring of unemployed people's activity was to take effect from the beginning of 2020, and the Rinne government proposed an end to ‘kiky’ hours, extra unpaid hours introduced during the Sipilä government, for the union negotiations.

In 2019, the report on the use of research‐based knowledge in law‐making was published and discussed, and sought to be adapted. The parliamentarians were twinned with researchers in projects involving the Committee for Public Information and TUTKAS, the Society of Scientists and Parliament Members. Also, the development of the regulatory process was given attention. This meant moving to a rolling two‐parliamentary regulatory plan and a regulatory programme for the whole electoral cycle. The independent Finnish Council of Regulatory Impact Analysis established in 2016 was chosen for the second term, covering the electoral cycle in April.

Issues in national politics

Besides social and healthcare reforms and the regions, emerging issues were racism, homophobia and sexual crime, linked with the particular scandals related to parliamentarians, but also with some other scandals linked to men in power. Rinne took part in the Helsinki Pride as the first Prime Minister in Finland to do so. Russian influence, particularly cyber influence, became palpable through both legislation related to personal information and the politicized EP 2019 elections. A major issue in Finnish politics was the climate, as the Greta Thunberg effect was palpable in Finland in the election in the spring of 2019 and reflected in both new governments’ programmes. On a more practical level, the mining rights of foreign companies were discussed, and the conflict between the use of land for mining versus tourism emerged as one of the keys as the discussions related to Lapland and the Saimaa lake area in eastern Finland (Suopajärvi & Kantola Reference Suopajärvi and Kantola2020). The Sami issue in a country lacking International Labor Organisation's (ILO) Convention No. 169 recognition was becoming palpable also through this case, and through a planned rail link to the North Sea across the traditional Sami lands in the north (Joona Reference Joona2020). This contestation contributed to the emerging support even if not yet the electoral success of the VIHR in Lapland in the 2019 national elections. As the new governments were committed to carbon‐free growth, fast rail links became a competition between Turku and Tampere – two key urban centres outside Helsinki. These themes of climate and global responsibility also linked to Finland's presidency of the European Union. This time the programme was relatively low key and focused on Helsinki rather than touring different parts of the country. What was toured in the end of 2019 was the premiership of Marin, which was globally recognized as a sign of a new generation and of women in power.

Table 1. Elections to Parliament (eduskunta/riksdag) in Finland in 2019

Note: Electorate figure is for Finnish citizens entitled to vote and resident in Finland.

Source: Statistics Finland (2019).

Table 2. Elections to the European Parliament in Finland in 2019

Note: Electorate figure is limited to Finnish citizens living in Finland. It does not include citizens of other European Union countries entitled to vote living in Finland.

Source: Statistics Finland (2019).

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Rinne I in Finland in 2019

Source: Finnish Government (2019).

Table 4. Cabinet composition of Marin I in Finland in 2019

Source: Finnish Government (2020).

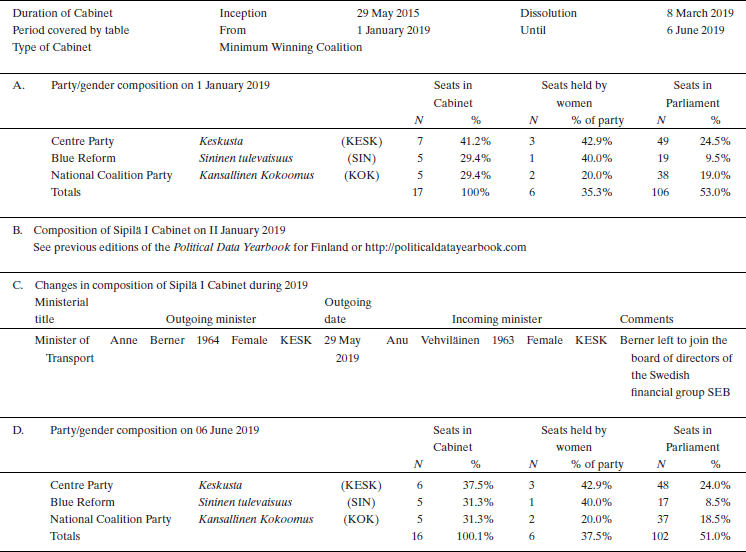

Table 5. Cabinet composition of Sipilä II in Finland in 2019

Source: Finnish Government (2019).

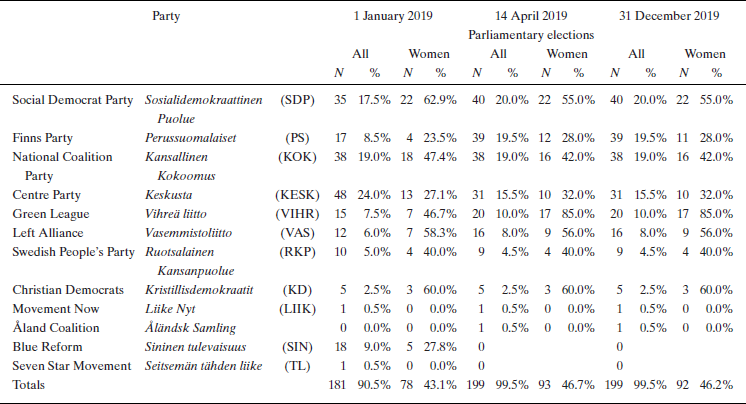

Table 6. Party and gender composition of Eduskunta in Finland in 2019

Note: Laura Huhtasaari and Teuvo Hakkarainen were also elected to the European Parliament.

Source: Palonen Reference Palonen2019, Parliament of Finland (2020).

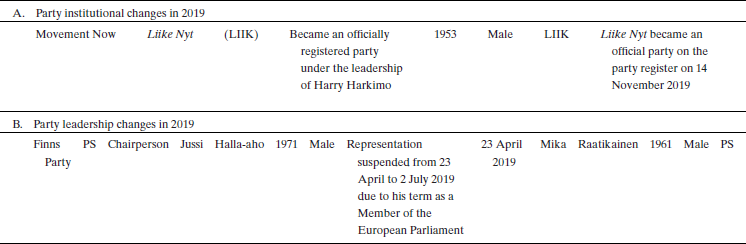

Table 7. Changes in political parties in Finland in 2019

Source: Parliament of Finland (2020).