Decades on, China’s Long 1980s continues to attract academic interest. While frequently invoked to refer to a broad reform era, the term is inconsistently defined and lacks clear contours. In defence of the Long 1980s as an analytically necessary framework – rather than relying on the conventional term “1980s”Footnote 1 or the vague notion of post-Mao reforms – I address key questions that remain unresolved in the existing scholarship. Where should this period begin and end – 1976 or 1978, 1989 or 1992?Footnote 2 What defines its internal coherence and historical mainstream? In answering these questions, this paper contributes to the conceptual consolidation of the Long 1980s and offers a new perspective on how we periodize and interpret contemporary China.

Hegelian-style historicism depicts the 1980s as a pivotal moment when China, as a people and/or nation, became once again enlightened to embrace the values and dignity of humanity. Li Zehou 李泽厚 recalled that “everything was reminiscent of the May Fourth era. Enlightenment and awakening of humanity, humanism, revival of human nature … all revolving around the theme of individual liberation.”Footnote 3 While reaffirming the period’s enduring relevance in Li’s Geist-driven nostalgia, I argue that the Long 1980s could be explicitly periodized only through the complementation of a Realpolitik-based historiography with an intellectualistic one.

Borrowing Eric Hobsbawm’s term, “long 19th century” (1789–1914),Footnote 4 I refer to the period from 1978 to 1992 as China’s “Long 1980s.”Footnote 5 This periodization is anchored not in diffuse sentiments of awakening or disillusionment, but in concrete political events that marked its beginning and end. I argue for 1978, rather than 1976, as the starting point, and for 1992, rather than 1989, as its conclusion – framing the period as defined by sustained tensions between reformist and conservative impulses. Central to this period was a reformism–conservatism dichotomy that permeated Chinese life. I highlight the competing interpretations of Marxism that corresponded to this divide: on one side, a humanist interpretation of Marxism and a reformist platform advanced by liberal intellectuals and reform-minded Party officials; on the other, an orthodox interpretation of Marxism upheld by conservative Party theoreticians and officials. Among the reformists, some went beyond the scope of reform, while others remained loyal to the Party’s political monopoly; among the conservatives, some accepted the economic component of the reformist platform, marketization, which others remained against even after 1992 when it was adopted as an official course. The reformism–conservatism dichotomy retains its validity in explaining the ideological landscape and policy debates not only during China’s Long 1980s but also beyond.

Following this logic, I tentatively divide China’s Long 1980s into four chronologically distinct periods. The first ranges from the third plenum of the 11th Party Central Committee in 1978 to the debate on humanism and alienation and subsequent “anti-spiritual pollution” campaign in 1983. The second ranges from 1983 to the 1986 student protests and subsequent “anti-bourgeois liberalization” campaign in 1987. The third ranges from 1987 to the 1989 Tiananmen protests and subsequent crackdown. The fourth ranges from 1989 to Deng Xiaoping’s 邓小平 Southern Tour and the subsequent 14th Party Congress in 1992.

Prelude: The Restoration of Intraparty Hierarchy

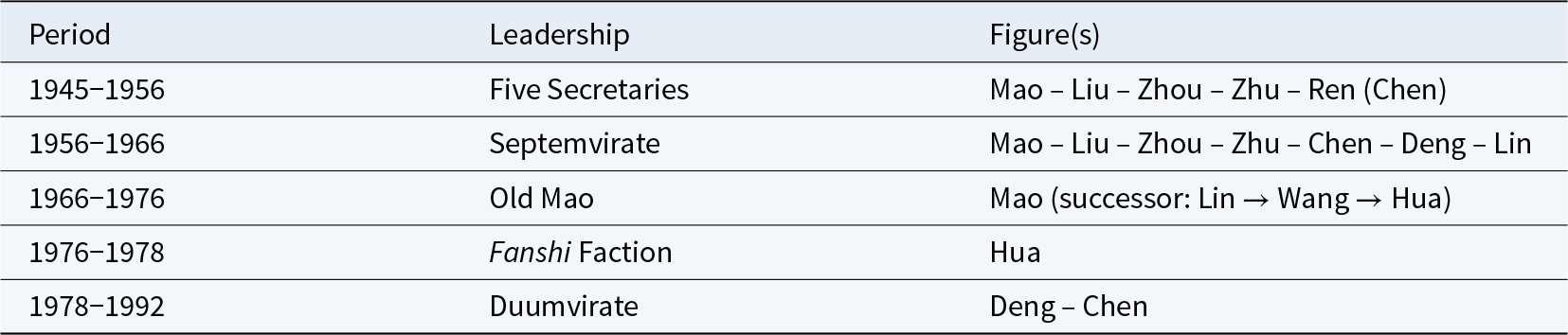

Either 1976, the year of Mao Zedong’s 毛泽东 death, or 1978, the year of the fall of his last successor, Hua Guofeng 华国锋, serves as a seemingly tenable beginning for China’s Long 1980s. However, Hua’s removal signified not only a change of power but also a restoration of the intraparty hierarchy that was crystallized in the 1940s (see Table 1).

Table 1. Party Leadership Successions, 1945–1992

Notes: Tabulation by author.

In 1945, Mao’s supreme status, which had begun to take shape a decade earlier, was formally declared at the Seventh Party Congress, along with a leadership comprising Mao at the helm and Liu Shaoqi 刘少奇, Zhou Enlai 周恩来, Zhu De 朱德 and Ren Bishi 任弼时 as secretaries of the Party Secretariat, the Party’s top decision-making body. Following his death in 1950, Ren was succeeded by Chen Yun 陈云, the top-ranked alternate secretary. The first and fifth plenums of the Eighth Party Central Committee added Deng Xiaoping and Lin Biao 林彪 to the top leadership, forming a septemvirate that remained in place until the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution. During this period, Mao grew increasingly distrustful of Liu and Deng, while placing greater trust in Lin, who always appeared to be on his side.

Official post-Mao historiography portrays 1966 as the year when Mao wrongly abandoned the organizational principle of collective leadership (jiti lingdao 集体领导). Whether or not this principle was ever genuinely practised under communist regimes, Mao’s final decade was indeed marked by tumultuous political struggles. Liu, ranked second and regarded as Mao’s designated successor, was purged and died in 1969. Lin was officially declared Mao’s successor at the Ninth Party Congress that same year. However, beneath Lin’s apparent loyalty lay his failed coup d’état attempt in 1971, after which he died in a plane crash while defecting to Moscow. Mao then appointed Wang Hongwen 王洪文, a poorly educated Shanghainese worker who was 42 years his junior, as his successor. For reasons still unclear, Mao ultimately replaced Wang with Hua Guofeng a few months before his death. The year 1976 witnessed the deaths of Zhou in January, Zhu in July and Mao in September, leaving Chen and Deng as the only surviving members of the septemvirate.

Within this context, two rival visions of legitimate succession emerged. One sought to restore the septemvirate – embodied by Chen and Deng – while the other upheld Mao’s final designation of Hua as his successor. Yet, before entering into confrontation, the two sides temporarily aligned to eliminate their shared rivals. The October 1976 coup d’état led to the arrest of Mao’s widow, Jiang Qing 江青, his nephew Mao Yuanxin 毛远新, former successor-designate Wang Hongwen, Zhang Chunqiao 张春桥 and Yao Wenyuan 姚文元, among other close allies, all accused of conspiring against Hua.

The coup consolidated Hua’s power and inaugurated a short-lived Hua era, but it also sowed the seeds of his downfall in 1978. Compared to the surviving pre-1966 Party elders, Hua was far more junior, and his legitimacy rested on the last words of a now-dead leader. To justify that Party leadership should be determined by Mao’s personal will rather than seniority, Hua’s faction advanced the “two whatevers” (liangge fanshi 两个凡是), or fanshi doctrine, which stated that they should “resolutely uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made and unswervingly follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave,” thereby underscoring Mao’s testament. In response, the anti-Hua forces countered with the slogan, “Seek truth from facts” (shishi qiushi 实事求是), or qiushi, arguing that truth derives not from prior instructions but from present realities, thus emphasizing the intraparty hierarchy.

Both factions appeared to adhere to Mao’s legacies, an indispensable part of which they themselves ironically eliminated in October 1976. The fanshi faction’s (fanshipai 凡是派) Aristotelian adherence was literal, while the qiushi faction’s (qiushipai 求是派) Platonic adherence was to Mao’s “living soul” (huo de linghun 活的灵魂). This idiom, meaning “seek truth from facts,” originates from the Book of Han (111 CE) and was famously used by Mao to justify his following a different approach from Moscow’s in the late 1930s.

The rhetorical contest between the two factions culminated in an epistemological debate, the symbolic apex of which was Hu Fuming’s 胡福明 May 1978 essay, “Practice is the sole criterion for testing truth” (Shijian shi jianyan zhenli de weiyi biaozhun 实践是检验真理的唯一标准). First published in Guangming ribao 光明日报 (Guangming Daily) and later reprinted in Renmin ribao 人民日报 (People’s Daily) and Jiefangjun bao 解放军报 (People’s Liberation Army Daily), the essay seemed to be another propagandist piece aimed at the losers of October 1976, accusing them of misinterpreting Maoism; its actual target, however, was the ruling fanshi faction. Politicians attuned to these hidden cues began issuing philosophical reflections, through which they articulated their views on Hua’s successional legitimacy.Footnote 6

From November to December 1978, the fanshi faction lost control over the Party’s political agenda. Senior leaders with real power over the military and the party-state apparatus criticized Hua, prompting him to eventually abandon the fanshi doctrine.Footnote 7 Shortly thereafter, the qiushi faction’s victory was cemented at the third plenum of the 11th Central Committee. As a result, leading fanshi members, such as Hua, Wang Dongxing 汪东兴, Wu De 吴德, Ji Dengkui 纪登奎 and Chen Xilian 陈锡联, were gradually sidelined.

The qiushi faction reached a consensus to repudiate Mao’s later years (wannian Mao Zedong 晚年毛泽东), including his designation of Hua as his successor, and to restore the pre-1966 leadership, which had by then effectively evolved into a duumvirate of the 74-year-old Deng Xiaoping and 73-year-old Chen Yun. However, there was no agreement on the economic path forward. Deng favoured a shift towards a market-oriented economy, while Chen remained committed to the Soviet-style planned economy that Mao had disrupted. Moreover, reformist leaders like Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 and Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳 within the qiushi faction began advocating not only for economic liberalization but also for political reforms aimed at democracy.

Hence, the qiushi faction, which initially formed as an ad hoc anti-Hua alliance, soon divided into what would became known as the reformist faction (gaigepai 改革派) and conservative faction (baoshoupai 保守派) throughout the Long 1980s. The division was not strictly binary, since one of the key figures, Deng, sat somewhere in between. Deng told the-then US secretary of state, George Shultz, that he was both a reformist in favour of a market economy and a conservative in defence of one-party rule.Footnote 8 Consequently, the political landscape should not be characterized solely by two factions, but rather what I call “two factions, three lines.” Dengism represented a middle line of economic liberalization without political democratization; reformists, such as Hu and Zhao, supported both, while conservatives, such as Chen and Li Xiannian 李先念, supported neither.

1978–1983: The Vicissitudes of Humanism

The post-Mao revival of Chinese humanism coalesced into a prominent trend during the 1983 debate on humanism (rendao zhuyi 人道主义) and alienation (yihua 异化) and would soon be condemned as “spiritual pollution” by conservatives in the subsequent “anti-spiritual pollution” campaign. Beneath the obscure philosophical discussions concerning alienation and praxis, which aimed at humanizing Marxism as the party-state official guideline, were competing political, economic and cultural platforms. Reformists embraced humanism as a vehicle to promote the market and democracy. Dengists held an ambivalent position: they supported the humanization of the economic sphere but not the political sphere. Conservatives rejected humanism altogether, viewing it as a threat to their autarkic, autocratic and theocratic control over China’s economy, politics and culture.

I divide the humanist revival into three categories: philosophical, aesthetic and Marxist.Footnote 9 Philosophical humanism centred on Li Zehou and his Kantian “philosophy of subjectivity,” which set the liberal tone for China’s 1980s “new enlightenment” (xin qimeng 新启蒙). Aesthetic humanism was reiterated by Dai Houying 戴厚英, Qian Gurong 钱谷融, Zhu Guangqian 朱光潜, Gao Ertai 高尔泰, and others, many of whom had previously been persecuted for their humanist writings. Meanwhile, Marxist humanists such as Wang Ruoshui 王若水, Ru Xin 汝信, Xue Dezhen 薛德震 and Xing Bensi 邢贲思 reinterpreted the party-state’s monist ideology, “Marxism,” as one that was compatible with – if not identical to – humanism, catalysing the 1983 debate on humanism and alienation.Footnote 10

Li Zehou’s Critique of Critical Philosophy primarily served as a comprehensive introduction to Kantian epistemology, ethics and teleology.Footnote 11 It was only in his later works, Four Theses on Subjectivity (1980, 1985, 1987, 1989), that he gradually unveiled his own “philosophy of subjectivity” (zhutixing zhexue 主体性哲学), which emphasized subjective agency in scientific inquiry, moral reasoning and artistic creation. His re-examination of Kantianism aimed to explore its potential contributions to contemporary Marxist philosophy – driven by an implicit ambition to Kantianize China’s state ideology by founding a new philosophy centred on subjectivity.Footnote 12

Li’s turn to Kant was not unprecedented. The Second International had already witnessed a “revisionist” movement calling for a “return to Kant,”Footnote 13 which ultimately contributed to the split between democratic socialism and communism. The Kantianizers prioritized the pluralism of truth and freedom of thought (Ding an sich) over ideological monism and determinism, due procedure and peaceful reform (deontology) over just ends and violent revolution, rule of law and separation of powers (Rechtsstaat) over ochlocracy and fusion of powers, and humanity over inhumanity.Footnote 14

In contrast to Li’s subtlety, the humanist trend in art, literature, aesthetics and literary theory was more explicit. Comparable to the literary thaw in the Eastern Bloc, which was named after Ilya Ehrenburg’s The Thaw (1954), China’s Scar Literature (shanghen wenxue 伤痕文学) took its name from Scar (Shanghen 伤痕), a short story by Lu Xinhua 卢新华, then a first-year undergraduate at Fudan University. While the story itself may have appeared sentimental, the term referred to the psychological trauma caused by earlier political persecutions, particularly during the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, the sensitive timing of its publication in August 1978 coincided with the anti-Hua trend, alluding to Hua’s reluctance to rehabilitate certain figures – such as Deng – who had been labelled as problematic by the recently arrested Gang of Four.

More works soon emerged. Zheng Yi’s 郑义 1979 short story Maple (Feng枫) portrays a young couple who end up killing each other during the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 16 Bai Hua’s 白桦 1979 screenplay, Bitter Love (Kulian 苦恋), was later adapted into the 1980 film, The Sun and Men (Taiyang he ren 太阳和人), which sparked a controversy.Footnote 17 Unlike Scar, the film did not place sole blame on the “anti-Party” Gang of Four. Instead, it appeared to question the legitimacy of the regime established in 1949 and, by extension, seemed to challenge the emerging post-Hua leadership. The final scene, showing the protagonist hiding in the reeds as a wilderness savage living on raw fish and rats and eventually dying, is reminiscent of Blaise Pascal’s words: “man is only a reed, the weakest in nature; but it is a thinking reed.”Footnote 18

The Sun and Men was generally well received by artists, intellectuals, film directors and critics. However, opinions were divided at the Central Party School, and the film received strong criticism in an article in the People’s Liberation Army Daily.Footnote 19 The China Writers Association-controlled Wenyi bao 文艺报 refused to publish the article. Reformist figures such as Hu Yaobang, Hu Jiwei 胡绩伟 and Zhou Yang 周扬 disagreed with the article, while the conservative theorist Hu Qiaomu 胡乔木 attempted to have it re-published in People’s Daily. Although Deng acknowledged the necessity of criticizing the film,Footnote 20 he considered the article to be inappropriate. He instructed the Wenyi bao to publish a moderate piece that took into account the opinions of artists and writers and directed People’s Daily to publish that article.Footnote 21

Other noteworthy works include Li Guyi’s 李谷一 1979 popular song, “Hometown love” (Xianglian 乡恋), which received unprecedented popularity for its delicate expression of romance as well as criticism for allegedly imitating Taiwanese singer Teresa Teng’s 鄧麗君 bourgeois “decadent music” (mimizhiyin 靡靡之音). Dai Houying’s semi-autobiographical novel, Human, Ah, Human! tells the story of a literature professor named Sun. To honour a promise, Sun married her childhood sweetheart Zhao instead of her university classmate He, and they eventually divorced. In 1957, He was labelled a “rightist” by the university’s Party secretary, Xi, and was sent to the countryside. There, He secretly studied philosophy and wrote a book titled Marxism and Humanism. After the Cultural Revolution, Sun and He met again, and she fell in love with him. However, Xi intervened again, this time blocking the publication of He’s book.Footnote 22

Dai Houyin had studied literature at East China Normal University in the 1950s, where one of her professors, the literary theorist Qian Gurong, was nearly labelled as a “rightist” for his 1957 article, “On literature as the study of humanity.” In 1980, Qian defended himself in a so-called “self-criticism”Footnote 23 of this article.Footnote 24 Aesthetician Zhu Guangqian, who had been criticized in 1956 for his “idealist aesthetics,” also sensed the thawing atmosphere and published the article, “On humanity, humanism, human touch, and common beauty,” in 1979 to “emancipate our minds and break through restricted areas.”Footnote 25 Another aesthetician, Gao Ertai, who had been labelled as a “rightist” in 1957 for his article, “On beauty,” re-published the piece in his 1982 collection of papers, On Beauty.Footnote 26

Aesthetic humanism gave a more concrete and vivid embodiment of humanism than Li’s euphemistic articulation of Kantian subjectivity, challenging artistic conventions and doctrines while encountering conservative obstructions. Nevertheless, the most imminent threat to party-state ideology came from reform-minded professional ideologues, namely, “theoretical workers” (lilun gongzuozhe 理论工作者). In Human, Ah, Human!, He’s Marxism and Humanism represents a discursive power, i.e. Marxist humanism, which stands in opposition to the official interpretation of Marxism.

Ru Xin, a researcher at the Philosophy Institute at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, initiated a “re-evaluation” of humanism in People’s Daily, arguing that the decades-long campaign against humanism was affirming “medieval inhumanity,” and that the label of “revisionism” imposed on humanism should be consigned to a museum.Footnote 27 The institute’s deputy director, Xing Bensi, published Humanism in the History of European Philosophy,Footnote 28 Philosophy and Enlightenment Footnote 29 and The Humanism of Ludwig Feuerbach.Footnote 30 His 1979 article, “Two great ideological liberation movements in European history,” suggested that China was now embarking on a movement akin to the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.Footnote 31 Xue Dezhen, editor-in-chief of People’s Publishing House, and Wang Ruoshui, deputy editor-in-chief of People’s Daily, co-edited two collections, Humanity as the Starting Point of Marxism and The Philosophical Discussions on the Theory of Humanity, both published by the Party-owned People’s Publishing House.Footnote 32

For those concerned about the rising tide of humanism, the ideologues’ humanist reinterpretations of Marxism appeared as a particularly dangerous Trojan horse, breaching the fortress from within. Li’s Kantianism could be dismissed as non-Marxist, but Marxist humanism contested the power to define Marxism. In the name of Marxist humanism, humanists, reformers and liberals rallied to launch a secular emancipation akin to the Reformation, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and the May Fourth movement. Meanwhile, apologists invoking (orthodox) “Marxism” resisted humanism, reform and liberalization in their efforts to preserve the ancien régime.

In summary, the Zeitgeist evidently shifted in 1978, from disputing Hua’s legitimacy to competing lines of reform, thereby opening China’s Long 1980s. Humanist tendencies in philosophy, art and literature, and Marxism – from Kantian axiology and Scar Literature on (in)humanity to theoretical revisions of philosophical Stalinism – inaugurated China’s “new enlightenment.” These efforts to humanize Chinese ideology and realities – politics, economy, society and culture – were met with conservative resistance, culminating in the 1983 debate on humanism and alienation.

1983–1987: Marx Displaced and the Dialectic of Politics

In February 1983, Zhou Yang, then the president of the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles, along with three younger intellectuals, Wang Ruoshui, Gu Xiang 顾骧 and Wang Yuanhua 王元化, gathered in Tianjin to prepare a speech for a conference at the Central Party School commemorating the 150th anniversary of Marx’s birth.Footnote 33 Entitled “Discussion on several theoretical issues of Marxism”Footnote 34 and later published in People’s Daily, the piece – particularly its final section on “The relationship between Marxism and humanism,” which elaborated on humanism and alienation – provoked a critical response from the Party’s chief conservative theoretician, Hu Qiaomu, whose rebuttal, “On humanism and alienation,” also appeared in People’s Daily.Footnote 35

Zhou’s speech served as the de facto Chinese Marxist humanist manifesto. Literary theorist Zhou rediscovered humanism through a difficult journey. Born in 1907, he joined the Party at the age of 20 and held leading roles in left-wing literary and artistic institutions. During his leadership from 1949 to 1996, the Party maintained a hostile stance towards humanism, most notably exemplified by the case of literary theorist, Hu Feng 胡风. Hu Feng and his followers, known as the Hu Feng clique, were persecuted for their literary and artistic humanism. During the Cultural Revolution, Zhou was also persecuted. After his rehabilitation, Zhou apologized to Hu Feng and began to advocate for humanism.

One member of the Hu Feng Clique, literary theorist Wang Yuanhua, was among the three younger intellectuals who drafted Zhou’s speech. Another drafter, Wang Ruoshui, had also worked with Zhou prior to the Cultural Revolution. In 1963, Zhou was instructed to lead a writing group tasked with producing a pamphlet criticizing Soviet revisionism, and Wang was responsible for two chapters – humanity and alienation.Footnote 36 Wang’s paper, “On the concept of alienation,” was written in 1964 but remained unpublished until the late 1970s.Footnote 37

In “Discussion on several theoretical issues of Marxism,” Zhou and his co-writers reconsidered these concepts in relation to Marxism and through the lens of their own life experiences, thereby questioning the long-standing condemnation of humanism:

I do not agree with subsuming Marxism under humanism, nor do I agree with reducing Marxism to mere humanism. However, we should acknowledge that Marxism encompasses humanism. We call it Marxist humanism. Humanity holds an important place within Marxism … The later developments of historical materialism and the theory of surplus value did not abandon humanism; rather, they grounded Marx’s humanism in a more scientific framework.Footnote 38

Beneath the claims that “Marxism includes humanism” and “the maturation of Marxism involves a stage of humanism” lay their practical advocacy for humanism. However, this argument could be readily refuted by referring to the difference between matured Marxism and humanism, especially the former’s dialectical sublation (Aufhebung) of the latter. This was exactly the tactic employed in Hu Qiaomu’s response:

The so-called “humanity as the starting point of Marxism” thesis typically blurs the boundaries between Marxism and bourgeois humanism, as well as between historical materialism and historical idealism … They either seek to subsume Marxism under humanism – portraying Marxism as a form of humanist worldview-historicism that is the “real,” “highest” and “most scientific” type of humanism – or to incorporate the humanist worldview-historicism into Marxist worldview-historicism, treating the former as the core, essence, starting point and end of the latter. In effect, both interpretations amount to the same thing: an attempt to humanize Marxism.Footnote 39

Indeed, Marxism cannot be reduced to humanism, and a “Marxist China” was expected to suppress “bourgeois” attempts to humanize Marxism or to replace it with humanism. However, the Achilles heel lay in Hu’s implicit assumption that there was no discrepancy between Marxism-in-theory and China-in-reality. Hu lightly sidestepped the scrutinization on whether Chinese reality was in line with Marxism, instead presuming that Marxism had already been actualized in China.

From Hu’s perspective, the lack of humanism in China was satisfactorily consistent with Marxism and should therefore be maintained, resisting the growing tide of humanization. According to Zhou and his co-writers, however, this absence did not reflect the fulfilment of Marxism but rather signified the failure to realize not only Marxism but also its foundational stage – humanism. In this context, the humanization of Chinese reality was not against Marxism, but a necessary step towards its realization. In other words, by addressing bourgeois humanist demands, China could move closer to Marx’s ideal.

The publication of Zhou’s speech in People’s Daily was approved by deputy editor-in-chief Wang Ruoshui and the paper’s president, Hu Jiwei. Under pressure from Hu Qiaomu and Deng Liqun 邓力群 – who reported the case to Deng Xiaoping and successfully advocated for a Party-wide rectification campaign – Wang was dismissed and Hu forced to resign.Footnote 40 The second plenum of the 12th Party Central Committee in October 1983 adopted a resolution to eliminate “spiritual pollution” (jingshen wuran 精神污染).Footnote 41

People’s Daily was the most prominent, although not the only, venue for the debate on humanism and alienation. Other key platforms included academic journals such as the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences’ Domestic Philosophical Trends (now Philosophical Trends), the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences’ Journal of Social Sciences and Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences). Most articles published before 1984 reflected a Marxist humanist position; however, 1984 witnessed a sweeping backlash against Marxist humanism as political struggles against spiritual pollution transcended the scope of theoretical polemics.

The term “spiritual pollution” was coined by Deng Liqun, the conservative theoretician who initiated the “anti-spiritual pollution” campaign.Footnote 42 While its immediate target was the philosophical movement of Marxist humanism, the term quickly expanded to encompass a wide range of cultural expressions, including popular hairstyles, bell-bottom trousers among youths, science fiction, Jenny Marx’s portrait, and the Florentine humanist magnum opus, Decameron.Footnote 43 This conservative backlash in culture was accompanied by attacks on the “commodity economy” (shangpin jingji 商品经济) promoted by reformist economists,Footnote 44 including the work, The Third Way, by the Czechoslovak reformist Ota Šik.Footnote 45

Owing to the intervention by General Secretary Hu Yaobang, this return-to-the-medieval campaign lasted less than a month.Footnote 46 Its end signalled a broader shift in the political atmosphere, with the balance of power once again swinging towards reformism. Deng’s early 1984 Southern Tour demonstrated his determination to advance economic liberalization, despite growing opposition led by Chen Yun. During this surprise trip, 80-year-old Deng visited major cities such as Guangzhou, Shenzhen 深圳, Zhuhai 珠海, Xiamen 厦门 and Shanghai on the south-east coast, where a series of special economic zones (SEZs) had been established since 1979 and were emerging as China’s “blue states” in contrast to regions more reliant on natural endowments. Subsequently, in March, the central government approved the opening of 14 additional coastal cities, marking an unprecedented expansion of SEZs.

Conservative leaders such as Chen Yun and Deng Liqun consistently opposed the establishment of SEZs, as well as free trade, globalism and openness.Footnote 47 They feared that the Sino-foreign exchanges facilitated by SEZs would increase the political risks to the regime. Although the SEZs were designed for economic purposes, they also served as windows through which the Chinese could engage with the broader world. It is no coincidence that Southern Weekly was founded in Guangzhou in the same year and would later become China’s “most influential liberal newspaper,” according to its US counterpart.Footnote 48

The domestic dimension of “Dengonomics” was transforming China from a planned economy to a market economy. The “Decisions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on economic system reform,” adopted in 1984, was preceded by heated debates. Prior to its passage, Chen Yun publicly defended the planned economy and criticized the reformist economist, Xue Muqiao 薛暮桥.Footnote 49 During the drafting process, reformist economist Gao Shangquan 高尚全 – whose 2021 funeral was attended by former Premier Wen Jiabao 温家宝, the most outspoken reformist politician in post-1989 China – frequently clashed with Party theoretician Wang Renzhi 王忍之. Wang would later play a key role in the 1989–1992 backlash that sought to roll back the economic liberalization of the 1980s.Footnote 50 Ultimately, with the backing of the reformist general secretary, Hu Yaobang, and Premier Zhao Ziyang, the the third plenum of the 12th Party Central Committee officially adopted the concept of a “planned commodity economy” (youjihua de shangpin jingji 有计划的商品经济),Footnote 51 marking a milestone in China’s economic reform agenda.Footnote 52

Owing to the time lag between writing and publication, 1984 witnessed a peak in criticism of the Marxist humanist literature that had been written during the 1983 “anti-spiritual pollution” campaign. In contrast, 1985 saw a moderate recovery of Marxist humanist literature, reflecting the reformist sentiment of 1984. This resurgence foreshadowed the larger reformist wave in 1986, which would later be denounced as “bourgeois liberalization” (zichanjieji ziyouhua 资产阶级自由化).

Starting in June 1986, Deng Xiaoping began to publicly advocate for “political reform” (zhengzhi tizhi gaige 政治体制改革), stating that it “was proposed as early as 1980 but has not been materialized; now it should be put on our agenda.”Footnote 53 For Deng, the move was a double-edged sword directed at anti-capitalist conservatives – rather than at himself. He made it clear that his vision was not focused on democratization per se but was instead a necessary means to advance his economic reforms by removing the man-made obstacles and people opposing his agenda.Footnote 54 Gorbachev faced a similar situation: when economic reform stalled, he, too, turned to political reform.

Deng’s “new political thinking” inspired a wave of liberalization. Wang Ruoshui published his anthology, A Defense of Humanism,Footnote 55 while Liu Zaifu 刘再复 applied Li’s philosophy of subjectivity to literary theory and published an article in People’s Daily calling for “socialist humanism.”Footnote 56 Meanwhile, conservative theoreticians launched Theory and Criticism of Literature and Art as a countermeasure to “criticize” the humanist-liberal trend, particularly targeting Theoretical Studies in Literature and Art, edited by Qian Gurong.

The situation soon spilled onto the streets. Three Party members played a critical role in “inciting” the student protests between late 1986 and early 1987: Fang Lizhi 方励之, vice-president of the University of Science and Technology of China; Liu Binyan 刘宾雁 and Wang Ruowang 王若望, respectively vice-chairman and councilman of the Chinese Writers Association. At a rally on 4 December 1986, Fang declared: “we have been talking about political reform for a long time. A lot of people wonder where the breakthrough will be … Democracy is not given from top to bottom; it must be earned by oneself.”Footnote 57 These words encouraged students to take to the streets the very next day, 5 December, which marked the beginning of the 1986 Chinese student demonstrations (baliu xuechao 八六学潮) that lasted until 2 January 1987. The protests began on the campus of the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei and quickly spread to as many as 28 cities, including Shanghai, Wuhan, Shenzhen and Beijing.Footnote 58

The reformist general secretary, Hu Yaobang, sought to engage the students in dialogue. In contrast, the temperamental conservative general, Wang Zhen 王震, threatened to mobilize “three million” troops against “three million” students and to “chop off a bunch of f*cking heads!”Footnote 59 A similar divergence within the leadership would be observed two years later. Nevertheless, the 1986–1987 protests ended peacefully, with all detained students released on 2 January 1987.

Yet, not only had conservative discontent with Hu reached its climax, but Deng, who had appointed Hu as general secretary and designated him as his successor, also came to view Hu as too “weak” in his handling of the student protests. On 16 January 1987, Hu was forced to resign. Meanwhile, Wang Ruowang, Fang Lizhi and Liu Binyan were expelled from the Party. On 28 January, the Party Central Committee issued a “notice” officially launching the “anti-bourgeois liberalization” campaign.Footnote 60

1987–1989: The Ephemeral Zhaoism

In many respects, the new campaign mirrored the “anti-spiritual pollution” campaign. As Deng Liqun put it, “bourgeois liberalization” and “spiritual pollution” were “two ways of saying the same thing.”Footnote 61 During the “anti-bourgeois liberalization” campaign, Wang Ruoshui, the flag bearer of Marxist humanism, was expelled from the Party. Like-minded theoreticians such as Su Shaozhi 苏绍治, then the director of the Institute of Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought (now the Academy of Marxism) at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, were dismissed from all posts. Zhang Xianyang 张显扬, a researcher at the same institute, was also expelled from the Party.

Like the “anti-spiritual pollution” campaign, the new campaign did not last long. In 1983, it was Hu Yaobang, and in 1987, it was Zhao Ziyang, whose resistance to the “anti-bourgeois liberalization” campaign became intertwined with the political struggle for the next general secretary. On the day of Hu’s resignation, Zhao succeeded him as the acting general secretary. During his premiership, Zhao had demonstrated his allegiance to Dengonomics. Meanwhile, conservative elders favoured Deng Liqun as the next general secretary at the upcoming 13th Party Congress; reformists, however, were wary of his political ambitions. In a letter to Deng Xiaoping, Li Rui 李锐 expressed concerns over Deng Liqun and suggested that “he must not be allowed to remain in the top leadership after the Congress.”Footnote 62 Chen Yun later blamed Deng Liqun’s failure on the “intrigues” of Li Rui and Zhao’s secretary, Bao Tong 鲍彤.Footnote 63

Nevertheless, regardless of what letters Deng received, the final decision rested with him alone. In the version of the “Notice on several issues concerning the current anti-bourgeois liberalization campaign” drafted by Deng Liqun, the concept of “bourgeois liberalization” was broadly defined, “ranging from politics to economy, culture, technology, education, and all realms of urban and rural social life.”Footnote 64 In contrast, the version drafted by Zhao’s secretary, Bao Tong, which was ultimately adopted on 28 January 1987, limited the campaign’s scope to “the Party, especially the realm of political thought.”Footnote 65

Zhao also held a “thorough conversation” with Deng Xiaoping, during which he convinced Deng that conservatives were utilizing the campaign as a pretext to reverse reformist policies. With Deng’s support, Zhao delivered a speech on 13 May 1987 that brought the campaign to an end.Footnote 66 What followed was the high point of China’s 1980s “new enlightenment,” both in theory and practice, lasting from mid-1987 to mid-1989 under Zhao’s reformist general secretaryship.

During the 13th Party Congress, held from 25 October to 1 November 1987, Deng Liqun not only failed to become the general secretary but also failed to be elected as a member of the Central Committee, which effectively ended his political career.Footnote 67 Faced with the overwhelming reformist sentiment within the Party, he was deemed unsuitable even for the Central Committee, let alone the Central Committee’s Politburo, the Politburo’s Standing Committee, or, ultimately, the position of the Politburo Standing Committee’s general secretary.

Policy-wise, Zhao’s political report at the 13th Party Congress – which designated “economic construction” (jingji jianshe 经济建设) as the Party’s top priorityFootnote 68 – marked another victory for the reformists. For conservatives, by contrast, the top priority was preserving the party-state and their associated privileges, even at the expense of economic development, as human freedom and prosperity are often in tension with the economic monopoly or the “material foundation” (wuzhi jichu 物质基础) of regime security. For instance, while the SEZs promoted economic growth, the accompanying free flow of information and international mobility posed risks to the regime’s control over the population and ultimately weakened the ruling status of the party-state. These concerns underpinned the conservative reluctance or opposition to reform.

Zhaoism found spectacular expression in the six-episode documentary, River Elegy (Heshang 河殇), which premiered on 11 June 1988. One of its authors, Yuan Zhiming 远志明, was a prominent proponent of Marxist humanism.Footnote 69 The documentary centred around an analogy contrasting the river-based “yellow civilization,” characterized by mystery, arbitrariness and autocracy – emblematic of conservative premodernity – with the ocean-based “blue civilization,” associated with transparency, science and democracy, representing reformist modernity. It argued that China’s economic reforms marked a shift from closedness to openness, and that the anticipated political reforms would further transition the nation from opacity to translucency. The documentary suggested that the Yellow River was “destined to pass through” and eventually “merge into the blue ocean,” overcoming its fears and sustaining its “indomitable impulse.”Footnote 70

The reformist platforms of economic liberalization and political democratization expressed in River Elegy broke free from the confines of “(anti-)Marxist” discourses and instead adopted the discourses of (anti-)modernity, revealing the real opposition of reformism – at the core of the orthodox interpretation of Marxism was the conservative defence of China’s traditional, agrarian civilization – symbolized by the Yellow River. Thus, the self-identified “socialists,” “anti-revisionists” and “orthodox Marxists” defending the “yellow river” occupied an extremely reactionary position, rather than any rhetorically revolutionary one. A parallel can be seen in debates over the SEZs: while the reformist–conservative struggle appeared to be centred on capitalism versus socialism or Marxian economics, it in fact echoed a much older conflict – whether China should open its ports to foreign trade. This debate dates back to the country’s early encounters with external modernity in the mid-19th century. Just as East Asian rulers then, Chinese conservatives in the 1980s, and North Korean leaders today have viewed foreign trade as a threat to domestic order.

Also in 1988, the New Enlightenment Series was launched, chiefly edited by Wang Yuanhua, one of the three drafters of Zhou Yang’s 1983 speech. Another co-author of the Chinese Marxist humanist manifesto, Wang Ruoshui, was also among the initiators,Footnote 71 while the Marxist humanist aesthetician Gao Ertai served as one of the two deputy editors.Footnote 72 The title New Enlightenment draws a parallel between the New Cultural movement (1915–circa 1923) – often referred to as China’s Enlightenment – and the Long 1980s intellectualism, signifying a re-Enlightenment of the still-unenlightened Chinese conditions.

From 1988 to 1989, the New Enlightenment Series published four volumes: Time and Choice, Crisis and Reform, On the Concept of Alienation and Lessons from the Lushan Conference. Wang Ruoshui contributed two articles – “On human nature and social relations” and “Does not alienation exist in socialist societies?” – as overdue responses to Hu Qiaomu’s “On humanism and alienation.”Footnote 73 In addition to Wang Yuanhua and Wang Ruoshui, many contributors were associated with Marxist humanism, yet their demands would now become much more explicit and without the rhetorical camouflage of Marxism. Their intellectual consciousness remained consistent from the debate on alienation and humanism to the New Enlightenment Series. Wang Ruoshui recalled that their motivation for the book series was to remove the “absolutist authority that reigned above” people and to encourage them to “open their eyes, break the illusion, and take control of their own destiny”Footnote 74 – that is, sapere aude.

The most momentous events of China’s Long 1980s unfolded between the sudden death of Hu Yaobang on 15 April 1989 and the military crackdown on pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square on 4 June 1989. Within less than two months, the ideals of River Elegy and the New Enlightenment Series were both vividly realized and violently crushed.

The initial mourning for Hu showcased widespread recognition of his reformist role – from the debate on humanism and alienation to the 1986 student protests – and popular discontent towards the conservatives who ousted him and hindered reform. As time went by, the movement escalated into large-scale demonstrations, hunger strikes and increasingly explicit demands for liberal democracy.

The general secretary, Zhao Ziyang, was presented with a dilemma similar to that faced by Hu Yaobang in 1986: whether to crack down on the protests or engage in dialogue with the students. For the reformists, the protests – triggered by the mourning for the reformist icon Hu – presented a precious opportunity to challenge, if not unseat, the conservatives in power and push for further reform. In contrast, conservative premier, Li Peng 李鹏 – whose resignation the protesters demanded – issued hardline statements calling for swift military suppression. Within the five-member Politburo Standing Committee, third-ranked Qiao Shi 乔石 abstained, fourth-ranked Hu Qili 胡启立 sided with Zhao, and fifth-ranked Yao Yilin 姚依林 backed Li.Footnote 75

History repeated itself with grim familiarity: just as he had done with Hu in 1986, Deng grew disillusioned with Zhao’s conciliatory stance and ultimately sided with the conservatives in favour of military intervention. On 20 May, the central government declared martial law. Tanks rolled into Beijing, resulting in a two-week standoff that ended in the violent crackdown on 4 June 1989 in the name of “quelling counterrevolutionary riots” (pingxi fangeming baoluan 平息反革命暴乱).Footnote 76

1989–1992: Reaction and Realignment

Following the bloodshed of 4 June, Zhao was replaced by Jiang Zemin 江泽民 at the subsequent fourth plenum of the 13th Party Central Committee and placed under house arrest until his death. Reformists who opposed the military crackdown were mostly dismissed from office, and many student leaders and liberal intellectuals were forced into exile abroad. River Elegy, produced to celebrate the Party’s reform, was now condemned by the Party, marking a significant shift in power towards conservatism.

Modelled on the campaigns against spiritual pollution and bourgeois liberalization, the “anti-peaceful evolution” (fan heping yanbian 反和平演变) campaign was launched by Chen Yun-led conservatives in 1989.Footnote 77 This time, neither Hu nor Zhao remained in power to contain it. The conservative agendas advanced unimpeded – until Deng saw the need to recalibrate the Party’s line.

Deng believed that the economic reforms, to which Zhao had greatly contributed, should continue following the restoration of order. In contrast, Chen Yun and other conservative leaders were of the view that the protest was the result of the Dengist reforms and liberalization measures implemented by his protégés, Hu and Zhao. To prevent such unrest from happening again, they argued, the prioritization of economic construction at the 13th Party Congress should be revised to prioritize both economic construction and the fight against “peaceful evolution” – a pejorative term for democratization through trade and openness.Footnote 78 According to modernization theory, as a country develops economically, individuals become more independent and autonomous, socio-culture more secular and diverse, and international exchanges more frequent and extensive. This process tends to give rise to the emergence of a middle class (bourgeoisie), the expansion of human and civil rights and the formation of civil society (bürgerliche Gesellschaft) – rendering democratization an eventual outcome. This vision of “peaceful evolution” both justified the West’s post-1989 rapprochement with China and reinforced conservative arguments for rolling back the reforms implemented under Hu and Zhao.

The official historiography highlights the 1990–1992 debate on whether a market economy “is socialist or capitalist” (xingshe xingzi 姓社姓资), concluding that a market economy is not necessarily capitalist. The substance of the debate, however, was not about definitions, as it may have seemed, but about policy – specifically, whether China should adopt a market economy. The rhetoric of politically incorrect “capitalism” and politically correct “socialism” served only to (de)legitimatize competing policy propositions.

In early 1991, Deng visited Shanghai and called for further economic reforms. His remarks were published pseudonymously as commentaries in Jiefang ribao 解放日报, the official newspaper of the Party’s Shanghai committee, under the auspices of reformist Shanghai Party secretary, Zhu Rongji 朱镕基. The Party’s mouthpieces in Beijing, such as Qiushi 求是 magazine and People’s Daily, published tit-for-tat commentaries rebuking Jiefang ribao.Footnote 79 These pieces were orchestrated by conservatives such as Chen Yun, Deng Liqun, Wang Renzhi and Gao Di 高狄, who took over the editorial leadership of People’s Daily after 4 June 1989, replacing the previous reformist editorship that had sympathetically covered the protests.Footnote 80

Similar to his 1984 tour following the 1983 “anti-spiritual pollution” campaign, Deng, then 88 years old, embarked on his 1992 Southern Tour, visiting cities such as Wuhan, Changsha, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Guangzhou, Shanghai and Nanjing. While some of his remarks remain undisclosed owing to their explicitness, the carefully edited versions of his speeches urged mainland China to learn from the developmental models of Japan and the Four Asian Tigers – Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.Footnote 81 Deng’s call coincided with the emergence of fully fledged democracies in South Korea and Taiwan, electoral reforms in Hong Kong, and the ending of the decade-long conservative governance in Japan and Lee Kuan Yew’s authoritarian rule in Singapore. The timing of his remarks suggested a distant prospect for democratization in China.Footnote 82

As The New York Times noted in its obituary: “even after his formal retirement in 1989, Mr. Deng remained an all-powerful patriarch, ordering a purge of the military leadership in 1992 and rescuing his economic reform program from a conservative backlash.”Footnote 83 Deng, along with two deputy chairmen of the Central Military Commission, attended a low-profile military conference in Zhuhai. Without any formal military capacity, Deng remained the ultimate authority to whom the military pledged allegiance. The conference, which was held without the knowledge of Jiang, who had nominally succeeded Deng as the chairman of the Central Military Commission, was arguably a quasi-coup d’état. The military subsequently declared its determination to safeguard (baojia huhang 保驾护航) Deng’s reforms, implying that it would replace the Jiang leadership with a reformist one if necessary.Footnote 84

The appointment of Jiang was a compromise between Deng and Chen. Not only did Jiang lean towards conservative elders, but he also allowed attacks on Dengonomics during the debate on the market economy. As Deng’s intentions became increasingly apparent during his tour, observers began speculating about who might soon replace Jiang and the conservative premier Li Peng. Among the leading candidates were Qiao Shi – who abstained from voting on the use of force in 1989 and chaired Deng’s Zhuhai Conference (Zhuhai huiyi 珠海会议)Footnote 85 – and Zhu Rongji, an unequivocal proponent of Dengonomics.Footnote 86

During the 14th Party Congress and the first plenum of the 14th Party Central Committee in October 1992, while Jiang and Li retained their positions, there were a number of consequential personnel moves. First, Zhu Rongji, previously an alternate member and not even a member of the Party’s Central Committee, was elevated to the Politburo Standing Committee, bypassing both the Central Committee and Politburo. In early 1993, he became the first-ranked deputy premier and effectively assumed responsibility for the Chinese economy. He succeeded Li Peng as premier in 1998 and came to be recognized as the engineer of China’s economic liberalization, which culminated in its long-anticipated accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001.

Second, Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 – a protégé of Hu Yaobang – joined the Politburo Standing Committee. At only 50 years old, he was notably younger than the other six members, whose average age was 66. Although it was never officially announced, Hu was widely regarded as Deng’s designated successor to Jiang. Hu succeeded Jiang in 2002 and served two five-year terms, thereby extending Deng’s political legacy well beyond his death in 1997.

Third, based on the stance they took during the debate on the market economy, conservative theoreticians such as Deng Liqun, Wang Renzhi and Gao Di were either demoted or marginalized, while reformists such as Hu Qili and Wang Yang 汪洋 were either (partially) reinstated or promoted.

The 1992 Party Congress elevated Dengism, i.e. “Deng Xiaoping Theory on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” (later shortened to “Deng Xiaoping Theory” in 1997), including the so-called “socialist market economy” (shehui zhuyi shichang jingji 社会主义市场经济), to the status of official Party ideology.Footnote 87 This move marked Deng’s final victory over Chen and brought China’s Long 1980s to a close. After Chen died in 1995, the Party’s official obituary described him as an “outstanding” (jiechu de 杰出的) Marxist, rather than a “great” (weida de 伟大的) one. This coded distinction in the Party’s lexicon acknowledged the eclipse of his conservative vision by Deng’s reformist legacy.Footnote 88

Conclusions

This paper presents a historiographical periodization of China’s Long 1980s, a period characterized not by the struggle over the legitimacy of political succession – as witnessed in the post-Mao transitional years from 1976 to 1978 – but by competing visions and enduring tensions between reformism and conservatism from 1978 to 1992, rather than ending in 1989. These ideological and policy dynamics shaped the trajectory of China’s Long 1980s, which unfolded across four distinct phases: 1978–1983, 1983–1987, 1987–1989 and 1989–1992.

Marxist humanism emerged from symbolic reflections on the Mao era. When the 1983 “anti-spiritual pollution” campaign was launched, Der Spiegel noted that: “The Chinese cannot live without an emperor.”Footnote 89 Mao was perceived not as a revolutionary but as a reactionary – an “emperor” whom the revolution was supposed to overthrow, representing not socialist futurity but feudalist historicity. The conservatives seemed to defend Mao as China’s Maximilien Robespierre of the Reign of Terror; in fact, they framed Mao more as China’s Louis XVI and a symbol of the ancien régime. On one hand, Marxist humanism distanced itself from Marx’s critique of modernity, aligning instead with “bourgeois” liberalism; on the other hand, the application of Marx’s critique of modernity in the orthodox interpretations of Marxism was a conservative appropriation in defence of premodern conditions. Neither side represented Marxism as the “ism” of Marx.

Throughout Deng’s 1984 Southern Tour, the 1986–1987 student protests and subsequent “anti-bourgeois liberalization” campaign, the obfuscating rhetoric of “Marxism” gradually gave way to the explicit discourse of modernity and/or modernization. This shift was manifested in River Elegy and the New Enlightenment Series. Within this context, humanist and orthodox interpretations of Marxism corresponded to reformist and conservative factions within the Party. Reformist humanists advocated for a market economy, democratic governance, avant-garde expression, an open society and cosmopolitan nationalism. In contrast, orthodox conservatives favoured precapitalist autarky (biguan suoguo 闭关锁国), authoritarian politics, traditional culture, closed society and particularistic nationalism.

The factional struggles that took place between 1989 and 1992 led to the unprecedented consolidation of Deng’s modernization programme, steering China away from the trajectory of a larger North Korea, characterized by hereditary succession and Soviet-type conservatism.Footnote 90 The dynamics of reformism and conservatism during China’s Long 1980s had two ends: 1989 marked the end of the contestations over political reform, while 1992 concluded those regarding economic reform. Together, what I refer to as the “1992 system”Footnote 91 was established – a technocratic caretaker government that would oversee authoritarian capitalism for the next two decades.Footnote 92

In conclusion, the 1978–1992 periodization of China’s Long 1980s offers the most coherent framework for capturing the trajectory of the reformism–conservatism dichotomy: 1976 was too early for the debate to have emerged fully, while 1989 was too early for it to have been resolved. This dichotomy retains its explanatory validity in post-1992 China, as seen, for example, in the (anti-)reforms during Zhu Rongji’s premiership and the debates on universal values during Wen Jiabao’s premiership. However, the ideological intensity during this period is no longer comparable to the Long 1980s, as two firewalls were forcefully established – one by political dictatorship through a military crackdown on 4 June 1989 and the other by the quasi-coup d’état during Deng’s 1992 Southern Tour, which cemented the market economy.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for the thoughtful engagement and intellectual stimulation provided by various scholars, especially Trencsényi Balázs, Michael Ignatieff, Karl Hall, Marko Faber, Mehti Mahmudov and Marta Haiduchok at CEU Vienna, as well as Jan Kiely (IHEID), Jason Wu (Indiana), Timothy Cheek (UBC), Yicheng Zhou (Fudan), Ying Qian (Columbia), Rüdiger Frank (Vienna), Hang Tu (NUS) and Clyde Wang (W&L). The author is also deeply indebted to the anonymous reviewers, whose extensive and constructive feedback played a defining role in shaping the final version of this paper.

Competing Interests

None.

Letian LEI is an associate instructor in the department of political science at Indiana University Bloomington. He specializes in political theory and the intellectual history of (post-)communist societies from a comparative perspective. He has published in the Journal of Political Ideologies and Waiguo zhexue, among others.