1. Introduction

Proficiency in decoding is fundamental to literacy (Snow, Reference Snow2002), prompting educators and reading scientists to tirelessly pursue advancements in reading development for individuals across various age groups (van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Espin, McMaster, Helder, Segers and van den Broek2017). However, for Chinese, an opaque mapping between phonology and orthography requires additional scaffolding to assist children in decoding Chinese words. Specifically, unlike alphabetic languages such as English, Chinese orthography is unique in several aspects: two different scripts (simplified and traditional) and unreliable phonological cues (McBride, Reference McBride2016). Due to the unreliable phonological cues and opaque mapping from phonology to orthography, which consists of thousands of complex visual symbols (Chinese characters), it is possible that the challenging tasks of visual analysis and memorization undermine an emphasis on meaning-making in early literacy instruction. Alphabetic phonological coding systems (e.g. Pinyin, Zhuyin-Fuhao) have been developed to support decoding and meaning-making for early and less proficient readers of Mandarin. These systems use a simpler, transparent, shallow orthography as a matrix for the many more complex characters while Chinese children learn to read.

Such phonology-based coding systems have been widely implemented in China. For example, Pinyin has been devised and taught in mainland China to facilitate the reading of complex Chinese words (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Liu, McBride and Zhang2015; Lin et al., Reference Lin, McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Levin2010). Similarly, in Taiwan, an alternative phonological coding system called Zhuyin-Fuhao has been introduced in primary schools to aid children in recognizing and learning characters, particularly complex ones (Zhang & McBride-Chang, Reference Zhang and McBride-Chang2011). One of the benefits of teaching Pinyin or Zhuyin-Fuhao is to enhance phonological processing, such as phonological awareness, which in turn facilitates later reading skills (Song et al., Reference Song, Georgiou, Su and Hua2016; Zhang & McBride-Chang, Reference Zhang and McBride-Chang2010, Reference Zhang and McBride-Chang2014). Phonological skills are a foundation of reading proficiency in alphabetic languages (Bus & Van IJzendoorn, Reference Bus and van IJzendoorn1999; Torgesen et al., Reference Torgesen, Wagner, Rashotte, Burgess and Hecht1997; Wagner & Torgesen, Reference Wagner and Torgesen1987) and also in Chinese, where most characters often include semantic radicals and phonetic radicals. Radicals in Chinese characters can be broadly categorized into two types: those that convey meaning (semantic radicals) and those that provide phonological information (phonetic radicals). For example, the character 妈 (meaning “mother,” pronounced /mā/), consists of two components: 女 (/nǚ/, meaning “female”), which serves as the semantic radical indicating the character’s meaning, and 马 (/mǎ/), which functions as the phonetic radical, offering a clue to its pronunciation. Although the correspondence between orthography and phonology in Chinese is limited, it has been well established that phonetic radicals – despite their imperfect reliability – play a significant role in character recognition. Their presence helps readers activate phonological representations, thereby facilitating the processing and learning of Chinese characters (Li et al., Reference Li, Li and Wang2020). For example, Li et al. (Reference Li, Li and Wang2020) showed that regular phonetic radicals improve phonology–orthography association, and as a consequence, Chinese character reading could be facilitated. Based on the unique contribution of phonetic radicals and phonetic radical awareness in Chinese reading development, it was observed that phonological awareness could enhance Chinese reading via the mediation of phonetic radical awareness (Tseng et al., Reference Tseng, Hu, Chang and Chen2023).

Phonological awareness is defined as “an individual’s sensitivity to sound structure of oral language” (Anthony & Francis, Reference Anthony and Francis2005). Phonological awareness is usually measured by asking the child to manipulate (e.g. delete) a unit of word structure at different levels, such as syllable or phoneme (Zhang & McBride-Chang, Reference Zhang and McBride-Chang2014). It is well established that phonological awareness is a strong correlate of reading development in both alphabetic orthographies such as English (Chiappe & Siegel, Reference Chiappe and Siegel1999) and morpho-syllabic orthographies such as Chinese (McBride, Reference McBride2016; Zhang & McBride-Chang, Reference Zhang and McBride-Chang2014). A growing body of evidence substantiates the positive impact of phonology-based coding systems on phonological awareness and reading development (Lin et al., Reference Lin, McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Levin2010). The ensuing section delves into an introduction of two prominent phonetic coding systems, namely Pinyin and Zhuyin-Fuhao, elucidating their constructive roles in the context of Chinese phonological processing and reading development.

1.1. Universal phonological principle and the positive effect of Pinyin and Zhuyin-Fuhao on Chinese phonological awareness and reading development

The universal phonological principle provides a theoretical basis for understanding the role of phonetic systems such as Pinyin and Zhuyin-Fuhao in Chinese reading development (Lin et al., Reference Lin, McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Levin2010). This principle posits that “contact with printed words in any writing system automatically activates the phonological properties associated with those words” (Perfetti et al., Reference Perfetti, Zhang and Berent1992). As Perfetti et al. (Reference Perfetti, Liu and Tan2005) argue, all writing systems fundamentally represent phonological units, a claim that can be extended to Chinese. Some Chinese characters incorporate phonetic radicals that serve as pronunciation cues – take 青 (/qing1/) in 请 (/qing3/) as an example. Here, the numbers (1, 3) following the Pinyin transcriptions indicate Mandarin Chinese tone values. The numeral “1” denotes the first tone (traditionally termed the “high level tone”), characterized by a steady, unwavering high pitch maintained throughout the syllable’s duration. In contrast, “3” marks the third tone (referred to as the “falling-rising tone”), which follows a distinct pitch contour: it begins at a mid-low pitch, dips slightly lower, and then rises back to a mid-high level. For these two characters, while their tone values differ, their underlying segmental structure (i.e. consonant /q/ and vowel nucleus /iŋ/) remains identical. Consider 晖 (/hui1/), which consists of 日 (/ri4/) and 军 (/jun1/), neither of which is phonologically related to the character itself. Given the growing body of evidence indicating that skilled readers across languages access phonological representations early in the reading process (Shankweiler & Fowler, Reference Shankweiler and Fowler2019), it becomes evident that beginning Chinese readers would benefit from an auxiliary phonetic coding system such as Pinyin or Zhuyin-Fuhao.

The Chinese Pinyin system comprises 21 onsets, 4 lexical-tone representations, and 35 rimes (Lin et al., Reference Lin, McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Levin2010). In mainland China, Pinyin has been widely adopted, while Taiwan utilizes Zhuyin-Fuhao, another phonetic system. These two phonological coding systems differ in their graphemes. Unlike the Latin alphabet used in Pinyin, Zhuyin-Fuhao employs components of ancient Chinese characters (Hayes-Harb & Cheng, Reference Hayes-Harb and Cheng2016), featuring 37 symbols. Consequently, Zhuyin-Fuhao can represent every Chinese character using four symbols or fewer per character (Stevenson et al., Reference Stevenson, Stigler, Lucker, Lee, Hsu and Kitamura1982). Both Pinyin and Zhuyin-Fuhao enable children to read connected text while they are still in the process of memorizing the full inventory of Chinese characters.

Despite these distinctions, both Pinyin and Zhuyin-Fuhao exhibit positive associations with phonological skills and reading (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Liu, McBride and Zhang2015; Hayes-Harb & Cheng, Reference Hayes-Harb and Cheng2016; Huang & Hanley, Reference Huang and Hanley1997; Lin et al., Reference Lin, McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Levin2010; Siok & Fletcher, Reference Siok and Fletcher2001; Wang & McBride, Reference Wang and McBride2017). One mechanism by which Pinyin improves pronunciation, naming, and recognizing unfamiliar words may be enhanced phonological awareness (Lin et al., Reference Lin, McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Levin2010). For instance, in a longitudinal study with 296 Chinese children, Lin et al. (Reference Lin, McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Levin2010) showed that invented Pinyin spelling skill was positively related to syllable deletion, phoneme deletion, letter-name knowledge, and Chinese character reading. More importantly, invented Pinyin spelling skill (time 1) predicted Chinese reading 12 months later (time 2), implying that Pinyin skill was a robust and unique predictor of Chinese character reading over time, outperforming traditional phonological skills like phonological awareness (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Liu, McBride and Zhang2015). Wang and McBride (Reference Wang and McBride2017) demonstrated that a combined intervention of copying and Pinyin knowledge enhanced children’s invented Pinyin spelling skills and overall character reading development. Huang and Hanley (Reference Huang and Hanley1997) illustrated that a 10-week Zhuyin-Fuhao instruction increased phonological awareness, a fundamental cognitive ability for Chinese reading (Song et al., Reference Song, Georgiou, Su and Hua2016). Though Pinyin and Zhuyin-Fuhao differ in symbols used, both offer transparent orthographies to beginning readers of Chinese. There is generally strong (but not universal, see Wang et al., Reference Wang, McBride-Chang and Chan2014) evidence that learning either of these two systems predicts performance on phonological awareness tasks in Chinese (Huang & Hanley, Reference Huang and Hanley1997; Lin et al., Reference Lin, McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Levin2010), as well as Chinese character recognition (Huang & Hanley, Reference Huang and Hanley1997). As previously contended, phonological awareness and phonetic radical awareness can facilitate Chinese reading. However, for developing children who are not yet acquainted with the Chinese writing system and characters, Pinyin and Zhuyin-Fuhao construct a framework that enables children to self-teach when reading aloud. Pinyin and Zhuyin-Fuhao explicitly break down the syllables into initials, finals, and tones. Here, initials are consonants at the beginning of syllables, whereas finals are the remainders of the syllables after the initials, including vowels and codas. For example, the character 成/cheng2/ (meaning “to become”) is written in Pinyin chéng. Children learn this represents the sound ch(initial) + eng(final) + rising tone (second tone é). The character, such as 成, could also serve a phonetic radical for a more complex character, such as 城, to help children access the phonology of the character. Specifically, by using Pinyin of chéng, children would likely become familiar with phonetic radicals, such as 成/cheng2/, meaning “success.” Subsequently, when they encounter complex Chinese characters, such as 城/cheng2/, meaning “city,” which contains that particular phonetic radical 成, children could establish a connection between the phonetic radicals and the new characters. As a result, a relatively potent contribution of phonological awareness to reading in Chinese can be observed.

1.2. Absence of phonetic coding system teaching in Macau

While Pinyin and Zhuyin-Fuhao have been implemented in mainland China and Taiwan to enhance children’s reading development, there has been a notable absence of such phonetic systems in kindergartens or primary schools in Macau and Hong Kong. This absence has implications for children’s reading development, as evidenced by studies showing that children who learned Zhuyin-Fuhao performed better in character reading than those without such instruction (Chen & Yuen, Reference Chen and Yuen1991). One potential reason for the absence of a phonetic coding system integrated into language teaching and learning in Macau and Hong Kong is that these regions predominantly speak Cantonese as the mother tongue, which is more complex in both segmental phonology and tones than Mandarin (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Meng, Tong, Yuan and Wu2018, Reference Zhang, Meng, Wu, Xiang and Yuan2019).

However, the absence of a phonological coding system in schools does not imply the absence of such systems for Cantonese. In fact, several phonology-based coding systems have been proposed, including Yale Romanization, Government Romanization, Wong’s scheme, Institute of Language in Education scheme, and Jyutping, developed by the Linguistic Society in Hong Kong (LSHK). Each system possesses its unique characteristics with associated advantages and disadvantages (Cheng & Tang, Reference Cheng, Tang, Chan and Minett2016). While Jyutping is occasionally taught in local universities due to its inclusiveness and simplicity, the majority of Hong Kong residents are not exposed to these notations in their school education (Cheng & Tang, Reference Cheng, Tang, Chan and Minett2016). Similarly, Jyutping has not been taught in Macau either. Since it has been shown that teaching the phonetic coding system is beneficial to Chinese reading development, it is worth investigating whether an intervention of teaching Jyutping could improve Chinese phonological awareness and reading development for children speaking Cantonese in Macau.

1.3. Phonological awareness in L1 and L2: Can Jyutping training facilitate L2 phonological awareness?

In addition to investigating the impact of Jyutping training on phonological awareness in the first language (L1), it is equally valuable to explore its effects on phonological awareness in the second language (L2), particularly in a context like Hong Kong/Macao, where children all formally learn English starting in elementary school. Previous research has demonstrated that phonological awareness acquired in L1 can be transferred to L2 learning (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Liu, McBride, Fan, Xu and Wang2018; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Cooc and Sheng2017; Zhang & McBride-Chang, Reference Zhang and McBride-Chang2014). For instance, Zhang and McBride-Chang (Reference Zhang and McBride-Chang2014) discovered that phonological awareness in L1 significantly predicted reading proficiency in English (L2) among Cantonese-English bilingual Hong Kong Children. Furthermore, a meta-analysis conducted by Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Cooc and Sheng2017) provided additional evidence suggesting that common linguistic features between Chinese and English facilitated the transfer of learning between the two languages. Notably, L1 and L2 phonological awareness exhibited a moderately positive correlation (r = 0.46). Based on this shared underlying mechanism of phonological awareness in L1 and L2 and shared orthography in L1 Jyutping and L2 English letters, it is hypothesized that Jyutping training could similarly enhance phonological awareness in the L2 (Cantonese) context. This prediction will be further investigated in the present study.

1.3. The present study

Building on the observed positive impact of phonetic coding training on the literacy development of Mandarin speakers, the present study sought to investigate whether the acquisition of Jyutping, a phonology-based coding system for Cantonese, could enhance phonological skills (i.e. phonological awareness) in Macau children. Despite the existence of multiple phonetic coding systems in Cantonese, Jyutping stands out for its simplicity and its occasional use in university teaching. Jyutping has been integrated into certain university courses to familiarize students with Cantonese pronunciation. Therefore, the present study adopts Jyutping as the intervention content for Cantonese phonology-based coding. Jyutping comprises 20 initial segments, like “b” (/b/, like 包, meaning “bag”) and “ng” (/ŋ/, like 五, meaning “five”), 51 final segments (including vowels and combinations of vowels), like “aai” (/aːi/, like 絲, meaning “silk”) and “aau” (/aːu/, like 手, meaning “hand”), and 6 tones, for instance, the first tone (媽 /maː1/, meaning “mom”) and the sixth tone (就 /jiu6/, meaning “then”). It is hypothesized that a brief training in Jyutping could improve Macau children’s phonological awareness in their L1, Cantonese, as well as their L2, English.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Sixty-seven kindergarten students enrolled in a local institution in Macao participated in our Jyutping intervention programme. The participants were divided into two groups: the intervention group comprised 34 children (mean age 5.85 years), while the control group consisted of 33 children (mean age 5.76 years).

All participants were native Cantonese speakers (mother tongue) with no prior exposure to Jyutping spelling in Cantonese. They had limited exposure to Chinese character reading (approximately 50 characters) through their kindergarten curriculum. All participants began learning English uniformly through the kindergarten curriculum, with no significant variation in English exposure at home.

Ethical approval for the programme was obtained from the University Committee for the Protection of Human Research (approval ID: BSERE21-APP019-ICI-01). Prior to the commencement of the study, written consent was acquired from the legal guardians of the participants, as well as from each individual child.

2.2. Procedure

The study employed a pre-test/post-test design. In the first session, all participants completed pre-test assessments of phonological awareness in both Cantonese and English. Following this, the intervention group received the Jyutping training over three consecutive days, while the control group continued with regular kindergarten activities. Immediately after the final intervention session, all participants completed post-test assessments using identical measures as those used in the pre-test. The study utilized a within-subject design for pre-test–post-test comparisons, which effectively controls individual differences, including potential socioeconomic variations.

2.3. Measures

Initial syllable deletion (Chinese). In this study, we employed an initial syllable deletion task to assess the cognitive abilities of young children in recognizing and manipulating Cantonese syllables. A similar task has been successfully utilized in prior research among Chinese-speaking children (e.g. Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, McBride-Chang, Wagner and Chan2014). This task required children to articulate the remaining parts of a Cantonese phrase or word by omitting the first syllable after hearing the phrase. For instance, upon hearing the Cantonese phrase “/Hung4 dau2 saa1/” (紅豆沙, “red bean dessert”), children were instructed to pronounce only the remaining part “/dau2 saa1/” (豆沙) and not the first syllable “/Hung4/” (紅). The task comprised a total of 12 items, including both real and nonsense three-syllable phrases, with one point awarded for each correct answer; otherwise, zero points were assigned. If a child answered a cumulative total of five questions incorrectly, the test would be halted immediately. The internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) of this task in the current study was 0.82.

Phoneme onset isolation (Chinese). We administered the phoneme onset isolation test adapted from the study of Lin et al. (Reference Lin, McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Levin2010) to evaluate children’s phonological awareness of Chinese at the phoneme level. The test comprised 17 monosyllables. In each trial, children were initially prompted to repeat a given Cantonese syllable and subsequently guided to produce only the initial sound. For instance, children followed the experimenter by articulating /baan1/ and then only the initial sound /b/. All onsets in this task were either singleton consonants (e.g. /b/, /d/, /m/) or consonant clusters (e.g. /gw/) that occur naturally in Cantonese. One point was awarded for each correct answer, with a maximum achievable score of 13 points. Additionally, the task concluded if a child accumulated a total of five incorrect responses. The internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) of this task in the current study was 0.92.

Syllable deletion (English). This task was employed to evaluate children’s proficiency in recognizing and utilizing syllables in English. In the English syllable deletion task, children were guided to repeat specific English words and then prompted to randomly omit a syllable from each word, presenting only the remaining syllable. For instance, the experimenter presented the word “Sunday” and the children echoed the word. Subsequently, the experimenter instructed them to exclude the last syllable “day” and articulate only the remaining syllable, in this case, “Sun.” The task included 12 items featuring two-syllable words (e.g. “mailman,” “sandbox”) and three-syllable words (e.g. “umbrella,” “crocodile”). Children earned one point for each correct answer, with testing discontinued after four consecutive incorrect responses. A previous study with kindergarten children in Hong Kong employed a similar task (McBride-Chang et al., Reference McBride-Chang, Cheung, Chow, Chow and Choi2006). The internal reliability (Cronbach’s α) of this task in the current study was 0.72.

Phoneme deletion (English). We utilized an English phoneme deletion task, adapted from the study of McBride-Chang et al. (Reference McBride-Chang, Cheung, Chow, Chow and Choi2006), to assess children’s phonemic awareness of English. The task comprised eight English items, with four of them requiring children to delete the initial English phoneme in a syllable. For instance, children were instructed to articulate “at” after omitting /m/ from “Mat.” Additionally, four items prompted children to delete the final phoneme. For example, they were asked to pronounce “boa” after eliminating /t/ from “boat.” All test items contained 3–5 phonemes and followed common English phonological patterns. Each correct answer earned one point, and testing was discontinued after four consecutive incorrect responses. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of this task was 0.74.

2.4. Intervention: Jyutping course

The research assistants (RAs) from our team designed and customized the Jyutping programme for the local kindergarten, utilizing the Jyutping system developed by the LSHK. Following a review of the K3 textbook used in local kindergartens, we identified the most commonly used consonants (initials) and vowels (finals). Based on this analysis, we selected 12 initials (b, p, m, f, d, t, g, k, h, z, c, and s) and 6 finals (i, yu, u, e, o, and aa) in accordance with the Jyutping system for instructional purposes. These selections represent approximately 60% of the consonants and 40% of the vowels in the complete Jyutping system, chosen based on their frequency in children’s early vocabulary. Due to time constraints on the intervention, we focused exclusively on teaching the first tone (i.e. aa1, baa1, faa1, maa1) of Jyutping.

Two trained local kindergarten teachers facilitated the intervention following a three-day training session conducted by the research team. The programme, comprising five 50-minute sessions, was delivered to the K3 intervention group as an extracurricular class over three days. Specifically, the experimental group engaged in Jyutping courses twice a day for 50 minutes, totalling 100 minutes, over the first two days and then attended a single 50-minute session on the last day. The three-day intervention period was determined by practical constraints of the kindergarten’s schedule during the study period. The control group adhered to the kindergarten’s regular extracurricular activities, while the intervention group attended the training sessions.

The intervention included three main components: learning Cantonese initials, learning Cantonese finals, and practising combining initials and finals in a spelling game. Each component received approximately equal instructional time across the five sessions. During the session on learning Cantonese initials, children were taught the graphemes of the initials using memory strategies. They followed the teacher’s tongue twisters to grasp the pronunciation of each initial and practised spelling familiar words (e.g. initial “b” has a round belly, b aa1 = baa1, b、b、b aa1 = baa1, 爸爸, 我愛我爸爸 meaning “Dad, I love my dad”). This approach used visual mnemonics and phonological awareness activities to help children associate the written symbols with their corresponding sounds. The teaching process for Cantonese finals mirrored that of initials. An example of the PowerPoint of the teaching process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. An example of the Cantonese initials learning. The teaching materials use child-friendly illustrations to facilitate learning of Jyutping components. This example shows how the initial “b” combines with the final “aa” and tone “1” to form “baa1” (爸/父, meaning “father”). The teaching approach uses visual analogies where initials (like “b”) form the foundation, finals (like “aa”) create the structure, and tones (like “1”) complete the syllable, similar to building blocks that children can easily understand and remember.

The final component involved interactive application of learned skills. Contextual games were employed for Cantonese spelling practice, where children randomly practised their spelling using word initials and finals they had learned. For instance, in the “Initials and Finals Finding Friends!” game, children paired initials and finals, pronouncing Jyutping correctly to become “best friends” and win the challenge.

3. Results

The four tasks administered in the present study evaluated children’s Chinese syllable awareness, Chinese phoneme awareness, English syllable awareness, and English phoneme awareness. Table 1 provides the means and standard deviations in each task for both the intervention and control groups.

Table 1. Pre-test and Post-test scores for intervention and control groups (values represent means with standard deviations in parentheses)

To mitigate potential confounding effects of participants’ prior phonological awareness in our intervention results, we conducted independent t-tests to compare pre-intervention phonological awareness between the intervention and control groups. The results revealed no significant differences in pre-test phonological awareness between the intervention and control groups (Chinese syllable awareness: t(65) = 0.56, p = 0.58; Chinese phoneme awareness: t(65) = 1.41, p = 0.16; English syllable awareness: t(51) = 1.57, p = 0.12; English phoneme awareness: t(65) = 1.54, p = 0.13). These findings indicate that our intervention and control groups were well matched on phonological awareness before the intervention.

For all four tasks, we conducted repeated measures ANOVA with a 2 (group: intervention versus control) × 2 (test: pre-test versus post-test) design to assess the impact of Jyutping training on phonological awareness. Detailed statistical results are presented in Appendix A.

3.1. Chinese initial syllable deletion

For Chinese syllable awareness, the main effect of the test is significant (F(1, 65) = 5.97, p < 0.05), while the interaction effect was not significant. This could be attributed to a ceiling effect observed in both the intervention and control groups’ Chinese syllable awareness, as indicated by the high pre-test scores (intervention: M = 10.76, SD = 2.51; control: M = 11.03, SD = 1.34), thus hindering the demonstration of the true efficacy of our intervention in the assessment results. Subsequent post hoc analysis using paired t-tests (with LSD correction) revealed significant improvements in Chinese syllable awareness among children from the pre-test to the post-test assessments (t = 2.12, p < 0.05) in the intervention group. However, there was no significant difference in test scores among children in the control group before and after the intervention period (t = 0.56, p = 0.0581).

3.2. Chinese phoneme onset isolation

For Chinese phoneme awareness, an interaction effect was observed between the pre-test and post-test scores, contingent on the grouping variable (intervention group or control group) (F(1, 65) = 8.98, p < 0.01). Furthermore, a significant main effect of test was detected in the analysis (F(1, 65) = 7.48, p < 0.01). Subsequent post hoc analysis unveiled noteworthy improvements in phonological awareness from pre-test to post-test (t = −3.741, p = 0.001) among students in the intervention group, with a mean improvement of 1.94 points (SD = 2.98). In contrast, the control group exhibited no significant changes in their Chinese phoneme awareness (t = 1.410, p = 0.163).

3.3. English initial syllable deletion

For English syllable awareness, a notable interaction effect was observed between test (pre-test versus post-test) scores and the grouping variable (F(1, 65) = 5.98, p < 0.05), and a significant main effect of test (F(1, 65) = 13.13, p < 0.05). Following post hoc analysis, substantial enhancements were identified in this aspect of phonological awareness among students from pre-test to post-test (t = −3.136, p < 0.01) in the intervention group, with a mean improvement of 0.91 points (SD = 1.67). Conversely, the control group exhibited no significant changes in their English syllable awareness (t = 1.585, p = 0.118).

3.4. English phoneme deletion

For English phonemic awareness, there was a significant interaction between the test time and the grouping factor on the assessment scores (F(1, 65) = 4.27, p < 0.05), suggesting variations in the intervention’s impact between the groups over time. Additionally, we observed a significant main effect of the test condition (F(1, 65) = 5.40, p < 0.05). Subsequent post hoc analysis uncovered significant improvements in phonological awareness among participants in the intervention group, with a substantial enhancement observed from pre-test to post-test scores (t = −3.156, p < 0.05), with a mean improvement of 1.00 points (SD = 1.82). However, participants in the control group exhibited no significant changes (t = 1.537, p = 0.129).

Overall, these results highlight a substantial improvement in students’ phonological awareness following the completion of the intervention programme, particularly for phoneme-level processing in both languages and for English syllable awareness.

4. Discussion

Chinese, with its opaque orthography–phonology mapping, presents a tremendous challenge for children to understand how visual symbols are connected to oral speech (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Chung, Wang and Liu2021). Accordingly, it is suggested that children are required to develop phonological awareness in order to recognize, identify, and manipulate phonological units within words (Tseng et al., Reference Tseng, Hu, Chang and Chen2023), thereby facilitating Chinese character recognition and reading (Tseng et al., Reference Tseng, Hu, Chang and Chen2023). In view of the significance of phonological awareness in Chinese reading, Tseng et al. (Reference Tseng, Hu, Chang and Chen2023) further proposed that in Chinese instruction, there should be a provision of additional training on phonological coding systems, such as Pinyin, Zhuyin-Fuhao, or Jyutping. The facilitation effect of the former two coding systems on phonological awareness has been validated in previous studies; however, there have been no prior studies on how Jyutping training might impact. Thus, the current study implemented a targeted intervention focusing on Jyutping to support phonological awareness and reading development among children in Macau who lack exposure to any phonology-based coding system in their L1. The findings robustly demonstrated the efficacy of a brief Jyutping training in enhancing children’s skills in manipulating syllables and phonemes in both Chinese (L1) and English (L2). Specifically, the intervention led to significant improvements in phonological awareness at both the syllable and phoneme levels. Children in the intervention group, who received Jyutping training, exhibited superior improvement compared to their counterparts in the control group across measures of phonological awareness in both L1 and L2.

Consistent findings from previous research have highlighted the predictive role of Pinyin skills in children’s reading development (Lin et al., Reference Lin, McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhang, Li, Zhang and Levin2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, McBride-Chang and Chan2014). The present study was the first to evaluate the effect of Jyutping training in Cantonese-speaking children. We empirically confirmed a positive association between phonology-based coding system training and phonological awareness. Jyutping is rarely taught in primary education in regions like Hong Kong and Macau. Our findings of enhanced phonological awareness in the group that had received Jyutping training not only supported a correlation between skills/knowledge in phonology-based coding systems and phonological awareness but also experimentally validated that phonological awareness could be enhanced by improving skills/knowledge in phonology-based coding systems, a finding previously reported for both Pinyin (Wang & McBride-Chang, Reference Wang and McBride2017) and Zhuyin-Fuhao. It is noteworthy to mention the contrasting findings of Wang et al. (Reference Wang, McBride-Chang and Chan2014), who identified no significant relationship between syllable awareness and invented Pinyin skills and knowledge. The discrepancy in findings was attributed to the nearly ceiling-level scores for syllable deletion in Wang et al.’s study. Furthermore, their research indicated that syllable awareness did not correlate with Chinese character reading and writing abilities, suggesting a lack of sensitivity in assessing syllable awareness. In the light of these findings, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, McBride-Chang and Chan2014) advocated for future studies to incorporate phonological awareness tasks at lower levels, such as phonemes, and to enhance task difficulty and measurement sensitivity. Taking heed of this suggestion, our study included phonological awareness tasks at both syllable and phoneme levels. The augmentation of Jyutping training aimed at improving phonological awareness at both levels underscores the heightened sensitivity of phonological awareness measurements. This approach not only addresses the limitations identified by Wang et al. (Reference Wang, McBride-Chang and Chan2014) but also enriches our understanding of the nuances of phonological awareness in reading development.

Furthermore, our study contributed additional evidence demonstrating that phonology-based coding system training in L1 could enhance phonological awareness not only in L1 but also in L2. A recent meta-analysis showcased clear cross-linguistic transfer for Chinese-English bilingual children (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Cooc and Sheng2017), with phonological awareness in Chinese and English exhibiting transferability and a moderate positive correlation between them (r = 0.46). However, the studies reviewed in that meta-analysis were correlational. Our experimental study filled this gap by showing that Jyutping training improved phonological awareness in both L1 (Chinese) and L2 (English), confirming a relationship between L1 and L2 phonological awareness. These results suggest an educational implication: phonology-based coding system training could benefit children learning either Mandarin or Cantonese, and even a short training period can enhance phonological skills development, laying a foundation for subsequent reading and writing development. Based on this brief training, children are furnished with a potent instrument of phonological recoding. Consequently, children are able to read aloud independently with the aid of a phonological coding system, such as Jyutping. This enables children to engage in self-teaching and learning and to utilize the phonological coding system when it is required. Furthermore, the facilitation of such self-teaching can persist for up to 7 days (Li et al., Reference Li, Li and Wang2020). In this respect, the training of the phonological coding system, even just once, can have a lasting effect. Moreover, as argued in Introduction, when children are equipped with this capability of phonological recoding, they would be familiar with some sample characters as phonetic radicals and further use phonetic radicals to establish a connection with phonology and orthography for Chinese characters (such as phonetic radical of 灰 [/hui1/, meaning “grey”] for恢 [/hui1/, meaning “disappointed”]). However, this speculation could be examined in future studies.

Several limitations and other future directions warrant consideration. First, our study provided only a short period of training. Therefore, while the efficacy of Jyutping training for improvements in phonological awareness was established, longer training durations could be explored to assess the training effect on other literacy-related skills, such as phonetic radical awareness, morphological awareness (McBride-Chang et al., Reference McBride-Chang, Shu, Zhou, Wat and Wagner2003), decoding skills (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Cooc and Sheng2017), and word recognition (Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Segers and Verhoeven2022). Secondly, the present study does not expand our understanding of how this training may influence reading development longitudinally. Thus, future studies could collect longitudinal data to examine the lasting effects of Jyutping training on phonological skills and reading development.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the University of Macau (MYRG2022–00055-FED). Artificial intelligence: No artificial intelligence-assisted technologies were used in this research or the creation of this article. Ethics: Ethical approval for the programme was obtained from the University Committee for the Protection of Human Research (approval ID: BSERE21-APP019-ICI-01).

Competing interests

All authors declare none.

A. Appendix A: Detailed statistical results for phonological awareness tasks

Table A1. Repeated measures ANOVA results (*p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01. For paired samples t-tests, negative t-values indicate improvement from pre-test to post-test. For independent samples t-tests on improvement scores, negative t-values indicate greater improvement in the intervention group compared to the control group)

Table A2. Paired samples t-test results (within-group comparisons) (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. For paired samples t-tests, negative t-values indicate improvement from pre-test to post-test. For independent samples t-tests on improvement scores, negative t-values indicate greater improvement in the intervention group compared to the control group)

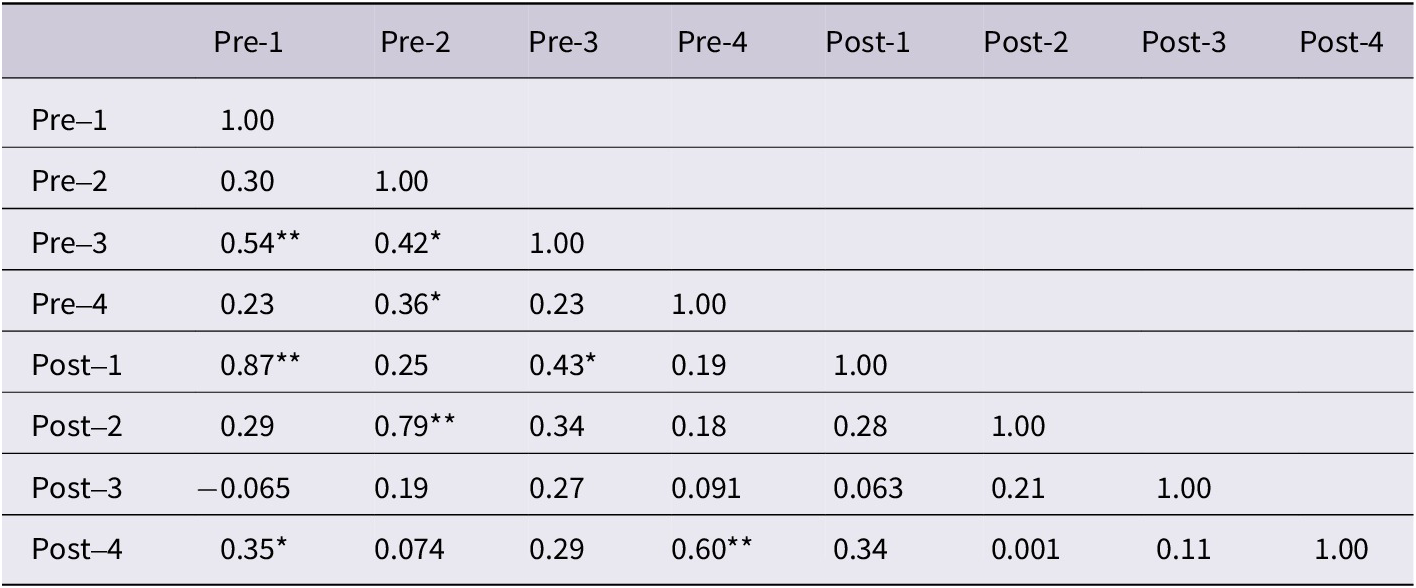

Table A3. Pearson correlation matrix of intervention group between pre-test and post-test measures (N = 33) (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. 1 = Chinese initial syllable deletion; 2 = Chinese phoneme onset isolation; 3 = English initial syllable deletion; 4 = English phoneme deletion)

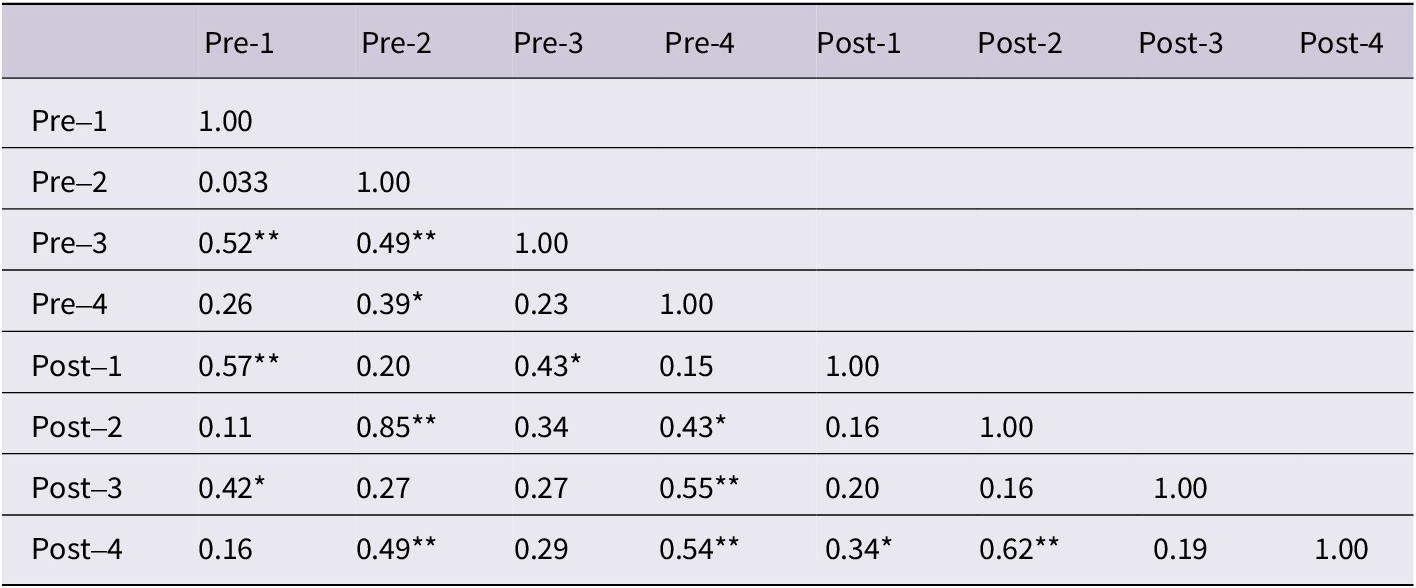

Table A4. Pearson correlation matrix of control group between pre-test and post-test measures (N = 34) (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. 1 = Chinese initial syllable deletion; 2 = Chinese phoneme onset isolation; 3 = English initial syllable deletion; 4 = English phoneme deletion)