Impact statement

Our study shows how ecosystem properties change along the encroachment gradient. As shrubs spread, individual patches become stronger “fertile islands” – the surface beneath them becomes rougher and collects more litter, and shrub size increases. However, increasing shrub cover simultaneously fragments the landscape, breaking connections between plant patches and creating a more disconnected environment. These opposing effects (better conditions beneath shrubs but reduced landscape connectivity) create significant trade-offs for the ecosystem and its inhabitants. This could include biota that operate at spatial scales consistent with the size of shrub patches. Conversely, animals needing larger open spaces (grassland specialists) or those forced to move longer distances between patches (such as mammals or some ground-nesting birds) are disadvantaged by the increased isolation and predation risk. Shrub encroachment is expected to intensify under drier, hotter conditions, amplifying this patchy landscape structure with fertile islands. Thus, the extent or encroachment is a critical consideration for managers. Moderate levels may present a balance for some benefits like biodiversity and carbon, while extensive encroachment favors shrubland species at the expense of grassland communities and overall landscape connectivity. Understanding the specific level of encroachment is therefore essential for predicting impacts and effectively managing these ecosystems under changing climates.

Introduction

Grasslands are a major biome in drylands, occupying 41% of the terrestrial area and accounting for 69% of global farmland (Suttie et al., Reference Suttie, Reynolds and Batello2005; O’Mara, Reference O’Mara2012). Grasslands support a large proportion of the world’s livestock and provide multiple ecosystem services such as climate regulation, soil conservation and biodiversity maintenance that are critical for human well-being (Bardgett et al., Reference Bardgett, Bullock, Lavorel, Manning and Shi2021). Yet, grasslands are threatened globally by increases in woody plants, largely a result of multiple interacting drivers including increasing land-use pressures, greater atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations and more varied rainfall events (Archer et al., Reference Archer, Andersen, Predick, Schwinning and Woods2017; Stanton et al., Reference Stanton, Boone, Soto-Shoender, Fletcher, Blaum and Mccleery2017; Ding and Eldridge, Reference Ding and Eldridge2024). Encroachment of woody plants into grasslands is likely to reduce not only pastoral potential but also lead to the widespread loss of critical ecosystem goods and services (Anadón et al., Reference Anadón, Sala, Turner and Bennett2014; Archer et al., Reference Archer, Andersen, Predick, Schwinning and Woods2017). Encroachment by shrubs (shrub encroachment) is globally widespread, with current estimates of 5 million km2 affected (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Bowker, Maestre, Roger, Reynolds and Whitford2011; Deng et al., Reference Deng, Li, Shi and Hu2021). However, the functional effects of shrub encroachment are highly debated, with the encroachment enhancing the quality of soil and environmental conditions for plants but regarded as a sign of grassland degradation (e.g., Ward et al., Reference Ward, Trinogga, Wiegand, du Toit, Okubamichael, Reinsch and Schleicher2018; Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Ding, Dorrough, Delgado-Baquerizo, Sala, Gross, le Bagousse-Pinguet, Mallen-Cooper, Saiz, Asensio, Ochoa, Gozalo, Guirado, García-Gómez, Valencia, Martínez-Valderrama, Plaza, Abedi, Ahmadian, Ahumada, Alcántara, Amghar, Azevedo, Ben Salem, Berdugo, Blaum, Boldgiv, Bowker, Bran, Bu, Canessa, Castillo-Monroy, Castro, Castro-Quezada, Cesarz, Chibani, Conceição, Darrouzet-Nardi, Davila, Deák, Díaz-Martínez, Donoso, Dougill, Durán, Eisenhauer, Ejtehadi, Espinosa, Fajardo, Farzam, Foronda, Franzese, Fraser, Gaitán, Geissler, Gonzalez, Gusman-Montalvan, Hernández, Hölzel, Hughes, Jadan, Jentsch, Ju, Kaseke, Köbel, Lehmann, Liancourt, Linstädter, Louw, Ma, Mabaso, Maggs-Kölling, Makhalanyane, Issa, Marais, McClaran, Mendoza, Mokoka, Mora, Moreno, Munson, Nunes, Oliva, Oñatibia, Osborne, Peter, Pierre, Pueyo, Emiliano Quiroga, Reed, Rey, Rey, Gómez, Rolo, Rillig, le Roux, Ruppert, Salah, Sebei, Sharkhuu, Stavi, Stephens, Teixido, Thomas, Tielbörger, Robles, Travers, Valkó, van den Brink, Velbert, von Heßberg, Wamiti, Wang, Wang, Wardle, Yahdjian, Zaady, Zhang, Zhou and Maestre2024). The effect of shrub encroachment also varies with its extent, with heavily encroached sites generally impossible to revert to grassland (Anadón et al., Reference Anadón, Sala, Turner and Bennett2014; Eldridge and Soliveres, Reference Eldridge and Soliveres2015). Predicted increases in climate variability are thought to stimulate shrub growth and therefore promote encroachment at the expense of grasslands (Bestelmeyer et al., Reference Bestelmeyer, Peters, Archer, Browning, Okin, Schooley and Webb2018; Deng et al., Reference Deng, Li, Shi and Hu2021). The impacts of shrub encroachment on ecosystem functions and services are intimately tied to changes in ecosystem structure. Thus, a better understanding of the response of ecosystem structure to intensifying shrub encroachment is essential if we are to effectively manage encroached grasslands under changing climates and land uses.

Despite the numerous studies of encroachment impacts on ecosystems, there is still considerable debate about the relative benefits or disbenefits of shrubs for ecosystem structure (Eldridge and Soliveres, Reference Eldridge and Soliveres2015). This uncertainty is due to the fact that their effects on ecosystem structure depend on the level of ecological processes over which they are assessed (e.g., Okin et al., Reference Okin, Heras, Saco, Throop, Vivoni, Parsons, Wainwright and Peters2015). For example, wide canopies, deep roots and branching stems of shrubs promote carbon and nutrient sequestration and hydrological function more effectively than herbaceous plants (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Eldridge and Soliveres2012; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Trinogga, Wiegand, du Toit, Okubamichael, Reinsch and Schleicher2018). The resource accumulation beneath shrub patches leads to the formation of fertile islands and biogeochemical hotspots (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Ding, Dorrough, Delgado-Baquerizo, Sala, Gross, le Bagousse-Pinguet, Mallen-Cooper, Saiz, Asensio, Ochoa, Gozalo, Guirado, García-Gómez, Valencia, Martínez-Valderrama, Plaza, Abedi, Ahmadian, Ahumada, Alcántara, Amghar, Azevedo, Ben Salem, Berdugo, Blaum, Boldgiv, Bowker, Bran, Bu, Canessa, Castillo-Monroy, Castro, Castro-Quezada, Cesarz, Chibani, Conceição, Darrouzet-Nardi, Davila, Deák, Díaz-Martínez, Donoso, Dougill, Durán, Eisenhauer, Ejtehadi, Espinosa, Fajardo, Farzam, Foronda, Franzese, Fraser, Gaitán, Geissler, Gonzalez, Gusman-Montalvan, Hernández, Hölzel, Hughes, Jadan, Jentsch, Ju, Kaseke, Köbel, Lehmann, Liancourt, Linstädter, Louw, Ma, Mabaso, Maggs-Kölling, Makhalanyane, Issa, Marais, McClaran, Mendoza, Mokoka, Mora, Moreno, Munson, Nunes, Oliva, Oñatibia, Osborne, Peter, Pierre, Pueyo, Emiliano Quiroga, Reed, Rey, Rey, Gómez, Rolo, Rillig, le Roux, Ruppert, Salah, Sebei, Sharkhuu, Stavi, Stephens, Teixido, Thomas, Tielbörger, Robles, Travers, Valkó, van den Brink, Velbert, von Heßberg, Wamiti, Wang, Wang, Wardle, Yahdjian, Zaady, Zhang, Zhou and Maestre2024) that provide refugia for plants and animals (Ochoa-Hueso et al., Reference Ochoa-Hueso, Eldridge, Delgado-Baquerizo, Soliveres, Bowker, Gross, le Bagousse-Pinguet, Quero, García-Gómez, Valencia, Arredondo, Beinticinco, Bran, Cea, Coaguila, Dougill, Espinosa, Gaitán, Guuroh, Guzman, Gutiérrez, Hernández, Huber-Sannwald, Jeffries, Linstädter, Mau, Monerris, Prina, Pucheta, Stavi, Thomas, Zaady, Singh and Maestre2018; Ding and Eldridge, Reference Ding and Eldridge2020). Such a heterogeneous distribution of resources beneath shrub patches would be expected to alter the spatial distribution of patches. For example, feedback between resource distribution and the development of shrub patches can lead to an acceleration of shrub encroachment, and a dwindling of resources in the interspaces, leading to the formation of self-perpetuating systems of resource-enriched islands within a resource-poor matrix (D’Odorico et al., Reference D’Odorico, Okin and Bestelmeyer2012). This would affect the spatial distribution of vegetation patches, which can alter the flows of energy and resources within the system, thus affecting ecosystem functions across the entire encroached system (Okin et al., Reference Okin, Parsons, Wainwright, Herrick and Fredrickson2008; Okin et al., Reference Okin, Heras, Saco, Throop, Vivoni, Parsons, Wainwright and Peters2015). However, current encroachment studies have tended to focus on finer-scale responses such as changes beneath patches (Maestre et al., Reference Maestre, Bowker, Puche, Hinojosa and Escudero2010; Eldridge and Soliveres, Reference Eldridge and Soliveres2015). The mechanisms by which ecosystem structure responds to shrub encroachment from finer (beneath patches) to coarser (between patches) levels remain poorly understood. Such a knowledge gap makes it more challenging to manage grassland functions more effectively by regulating different levels of ecosystem structure.

The response of ecosystem structure to encroachment also varies with the degree of encroachment (Eldridge and Soliveres, Reference Eldridge and Soliveres2015). When shrub cover is sparse, at a low degree of encroachment, forage production could potentially be greater under encroachment due to the addition of novel niches that support a larger range of plant species (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Eldridge and Soliveres2012). As shrub cover increases, the larger canopy cover and deeper root system of shrubs would increase resource competition on herbaceous species and therefore reduce grass biomass (Brown and Archer, Reference Brown and Archer1989; Anadón et al., Reference Anadón, Sala, Turner and Bennett2014). These changes in ecosystem attributes with the degree of encroachment are thought to reflect shifts in ecosystem status (Bestelmeyer et al., Reference Bestelmeyer, Peters, Archer, Browning, Okin, Schooley and Webb2018). For example, vegetation biomass and plant richness have been shown to decline from low to medium encroachment but increase from medium to heavy encroachment, suggesting a state change from grass dominance to shrub dominance (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Li, Li, Zhang, Zhang, Li, Zhao, Jiang and Ma2013). These changes in ecological attributes arise potentially from changes in shrub community characteristics (canopy, height and size distribution) as shrubs expand (Maestre et al., Reference Maestre, Eldridge, Soliveres, Kéfi, Delgado-Baquerizo, Bowker, García-Palacios, Gaitán, Gallardo, Lázaro and Berdugo2016). However, as most studies to date have tended to focus on a particular degree of encroachment (e.g., low, medium or heavy), empirical evidence for change across a wide spectrum of encroachment is lacking (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Li, Li, Zhang, Zhang, Li, Zhao, Jiang and Ma2013; Soliveres and Eldridge, Reference Soliveres and Eldridge2013), making it difficult to manage grasslands under different levels of encroachment, particularly during the early stages of encroachment when woody removal treatment is more effective (Ding and Eldridge, Reference Ding and Eldridge2024) and financially viable.

To address these issues, we analyzed the response of ecosystem structure beneath patches (patch condition) and between patches (spatial distribution pattern of patches) along an extensive shrub encroachment gradient covering low, medium and heavy encroachment sites across Inner Mongolia, China. Regression analyses, linear models and structural equation modeling (SEM) were used to address three predictions. First, we expected that for ecosystem structure beneath patches (Figure 1a), community structural characteristics (e.g., height and canopy) would vary with the degree of shrub encroachment, and soil and vegetation condition (e.g., litter, crust stability and exposure to grazing) would become more stable in the shrub patch as shrub encroachment intensifies due to the accumulation of resources beneath shrubs. Second, we predicted that for ecosystem structure between vegetation patches (i.e., spatial distribution patterns of vegetation patches), connectivity among vegetation patches would decline with increasing shrub encroachment (Figure 1b). This is because increasing shrub encroachment would result in the aggregation of shrubs, which strengthens resource redistribution from the grassy interspaces to the aggregated shrub patches, thus leading to a more discrete and broken landscape. Third, for those mechanisms promoting ecosystem structural changes under intensified shrub encroachment, we expected that an increasing degree of shrub encroachment would elicit changes in the spatial pattern of patches. This would be expected to occur either directly or indirectly, by altering ecosystem structure beneath patches (e.g., community characteristics of shrubs such as height, canopy width and patch condition). Such effects would be enhanced under drier and hotter climatic conditions (e.g., greater aridity and mean annual temperature). This is because changes in community- and patch-level structure would alter resource redistribution at the site or landscape level, thus regulating the organization of vegetation and the effect of encroachment is known to strengthen in drier and hotter environments.

Figure 1. Hypothetical relationships between the magnitude of shrub encroachment (indicated by shrub cover) and ecosystem structure. (a) Ecological condition of patches (e.g., herbaceous biomass beneath patches and soil surface properties); (b) spatial distribution pattern of vegetation patches (e.g., distance between patches and patch brokenness).

Methods

Study area

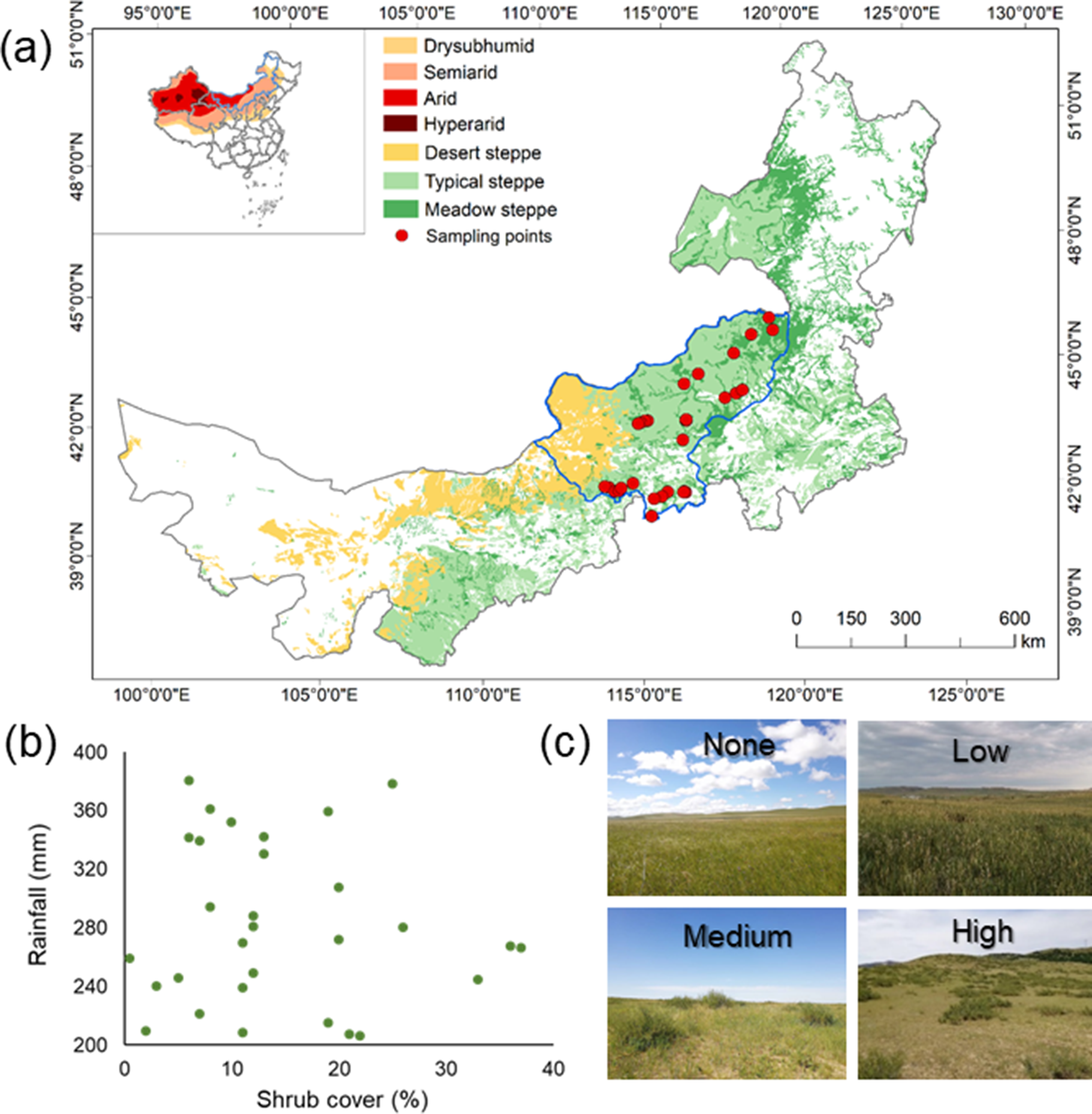

This study was conducted in Xilingol, Inner Mongolia, China, in the central part of the Eurasian steppe (Figure 2). We established an east–west transect (43.92°N ~ 46.56°N; 113.54°E ~ 119.29°E) of shrub-encroached grasslands across a typical steppe. The mean annual temperature of the study area ranges from 0 to 3 °C, and mean annual precipitation ranges from 150 to 500 mm. Soils in the area are dominated by chernozems and typical and sandy chestnut soils. The dominant grass species are Stipa baicalensis, Filifolium sibiricum, Stipa krylovii, Stipa grandis and Stipa klemenzii, and the dominant encroached shrub species is Caragana microphylla. To avoid the confounding effect from human disturbance and additional water resources, all the study sites were selected away from any towns, villages and rivers.

Figure 2. (a) Sampling sites across Xilingol, Inner Mongolia, China, and photos of different levels (none, low, medium and high) of encroachment; (b) shrub cover range of sampling sites across the rainfall gradient; and (c) the relationship between shrub abundance and shrub cover.

Field survey

Vegetation sampling

We surveyed 30 sites along the gradient of shrub encroachment across semiarid and arid areas in August 2022 (Figure 2).

In each site, we established a 30 m × 30 m sampling plot within which we measured four structural measures of 20 shrubs: 1) height (cm); 2) canopy width (cm); 3) stem diameter (cm); and 4) the number of branches. This allowed us to assess the community structural characteristics of shrubs (Hypothesis 1). Shrubs were selected randomly across the whole 30 m × 30 m plot. We counted the number of shrubs to derive a measure of shrub density and measured all shrubs at sites supporting fewer than 20 shrubs. To better capture the distribution of shrubs, shrub cover was estimated using a drone image from DJI Mavic 2 (resolution 1.4 cm; see 2.2.3 for details). In each site, we selected a 30 m × 30 m image corresponding with the field-based sampling plot and used a line intercept method to estimate shrub cover in each site. In the encroached grassland of Inner Mongolia, shrub cover peaked at ~40%, with Caragana spp. being the major encroached species (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Li, Zhang, Zhao, Zhou, Liu, Hu, Bai, Shen and Fang2015). In our study, shrub cover in the 30 sites ranged from 0.5% (low encroachment) to 37% (heavy encroachment), which spanned the entire range of encroachment in the region, covering low, medium and high degrees of encroachment. However, the range of encroachment may not be equivalent to that in other areas across the globe due to differences in woody species and ecosystem biomes (Eldridge and Soliveres, Reference Eldridge and Soliveres2015).

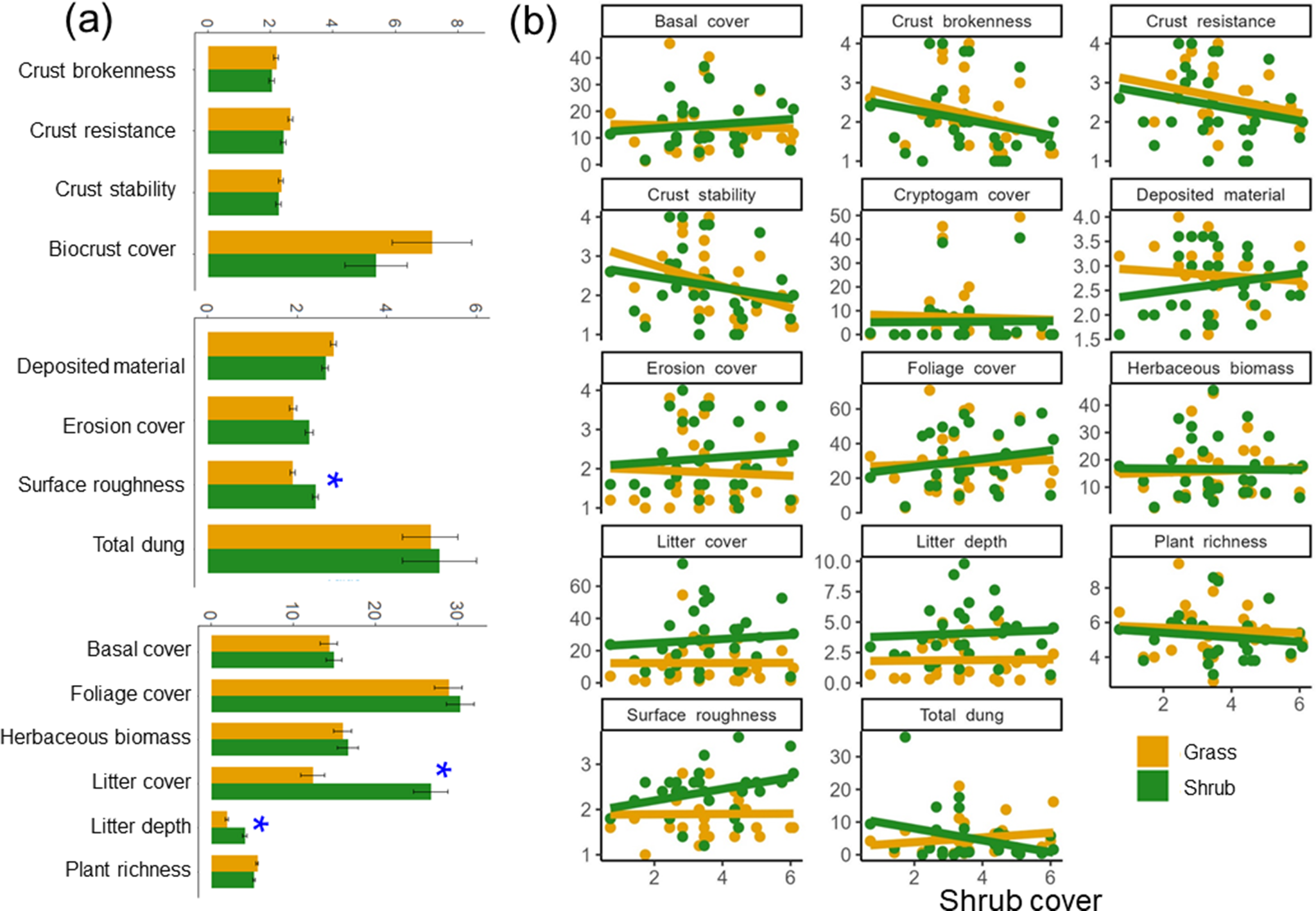

Soil surface condition assessment

To assess patch condition beneath shrubs and grasses (Hypothesis 1), we measured 13 soil surface attributes within a 0.5 m × 0.5 m quadrat beneath five replicate shrubs and within their paired grassy interspace in each plot. Soil surface condition is strongly related to ecosystem functions (e.g., infiltration, nutrient and microbial activities; Ding and Eldridge, Reference Ding and Eldridge2022; Eldridge and Delgado-Baquerizo, Reference Eldridge and Delgado-Baquerizo2018). Within each quadrat, we assessed (1) crust resistance, (2) crust brokenness, (3) crust stability, (4) the cover of biocrusts, (5) cover of deposited material, (6) erosion cover, (7) surface roughness, (8) grazing intensity, by measuring the mass of dung of different herbivores, (9) basal cover, (10) foliage cover, (11) plant richness, (12) litter cover and (13) litter depth using a modified version of the soil surface condition protocols used in the landscape function analysis (LFA) procedure (Tongway and Hindley, Reference Tongway and Hindley2004, Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Delgado-Baquerizo, Quero, Ochoa, Gozalo, García-Palacios, Escolar, García-Gómez, Prina and Bowker2020a; see details and measurements for each attribute in Table 1). After assessing soil and vegetation conditions, we clipped all of the understory plants in each 0.5 m × 0.5 m quadrat and oven-dried the material at 65 °C for 48 h to measure herbaceous biomass as a measure of forage production.

Table 1. Attributes used to assess the 13 soil surface condition (SSC) indices

Drone image processing

We used a drone to obtain high-resolution images of each site to assess the spatial distribution pattern of patches. A DJI Mavic 2 (Da-Jiang Innovations, Shenzhen, China) was used to capture high spatial resolution (1.4 cm pixels) visible color imagery in an 8-bit JPEG format of the site. Each site was flown in an area of 100*100 m in a series of parallel flight paths (designed by DJI GS Pro App) at a height of 15 m above ground level. The OpenDroneMap software program was used to process images from each field site into an 8-bit orthomosaic georeferenced GeoTiff image. OpenDroneMap is a free open-source unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photogrammetry software platform that is run in a virtualization with Docker container environment.

To assess landscape connectivity (among vegetation patches), we classified the whole site into two land-cover types, vegetation and bare ground, in ENVI 5.5 (https://envi.geoscene.cn/) using support vector machine classification based on the DJI Mavic 2 high spatial resolution image. We classified the image into vegetation and bare to assess the vegetation connectivity between patches.

Statistical analysis

Variation in the shrub community

To obtain the community characteristics of shrubs at each 30 m × 30 m plot, we calculated the mean, median, skewness (degree of asymmetry) and kurtosis (the tailedness) of the size distribution and the coefficient of variation (CV%) of canopy width, height, stem diameter and number of branches of each shrub at a site. We then fitted linear regressions between measures of community structure and the square root of shrub cover to explore how the shrub community changes with the degree of shrub encroachment.

Difference beneath patches

To assess the spatial distribution pattern of patches (Hypothesis 2), we used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the differences in soil surface condition between shrub patches and interspaces. We fitted linear regression and quantile regression (5th and 95th quantiles) between measures of soil surface condition and the square root of shrub cover to explore whether the conditions of the shrub and interspace grassy patch changed significantly with increasing shrub encroachment. Quantile regression is used widely in ecology to illustrate changes in linear relationships and to quantify the boundaries of scatter points against environmental gradients.

To assess the spatial variation in soil surface conditions at each 30 m × 30 m plot, we calculated a dissimilarity index (Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, unitless) between shrub patch and paired interspace based on the matrix of attributes (raw values) within different components of the soil surface: i) the surface crust (crust resistance, crust brokenness, crust stability and the cover of biocrusts), ii) other surface attributes (cover of deposited material, erosion cover, surface roughness and grazing intensity) and iii) plant attributes (basal cover, foliage cover, plant richness, litter cover and litter depth). We then used average dissimilarity as a measure of spatial variability at each site. The Bray–Curtis dissimilarity between vegetation patch types j and k at each site (Djk) is calculated as

$$ {D}_{jk}=\sum \limits_{i=1}^n\mid {x}_{ij}-{x}_{ik}\mid /\sum \limits_{i=1}^n\left({x}_{ij}+{x}_{ik}\right) $$

$$ {D}_{jk}=\sum \limits_{i=1}^n\mid {x}_{ij}-{x}_{ik}\mid /\sum \limits_{i=1}^n\left({x}_{ij}+{x}_{ik}\right) $$

where xij and xik are the raw values of soil attributes i in vegetation patch types j and k at each site. n is the number of soil surface attributes.

Vegetation distribution pattern assessment

To assess the spatial distribution pattern of patches, we selected eight landscape pattern indices that describe the brokenness of connectivity of vegetation patches compared to the non-vegetated patches (ecological meaning and rationale of index selection are shown in Supplementary Table S1):

-

(a) Aggregation Index (AI; %).

![]() $ {g}_{ii} $

is the number of similar adjacencies (joins) between pixels of patch type (class, vegetated cf. bare) i based on the single-count method.

$ {g}_{ii} $

is the number of similar adjacencies (joins) between pixels of patch type (class, vegetated cf. bare) i based on the single-count method.

![]() $ \mathit{\max}\to {g}_{ii} $

is the maximum number of similar adjacencies (joins) between pixels of patch type (class) i (see below) based on the single-count method. The index ranges from 0 to 100, with a greater number indicating more aggregation of the patch type.

$ \mathit{\max}\to {g}_{ii} $

is the maximum number of similar adjacencies (joins) between pixels of patch type (class) i (see below) based on the single-count method. The index ranges from 0 to 100, with a greater number indicating more aggregation of the patch type.

-

(b) Standard Deviation of Patch Area (unitless). Standard deviation of the patch area. An index >0 indicates a more variable patch size.

-

(c) Edge Density (m/m2). This is the sum of the lengths of all edge segments in the landscape, divided by the total landscape area. An index value >0 indicates greater patch brokenness.

-

(d) Landscape Division Index (DIVISION; unitless).

$$ \mathrm{DIVISION}=\left[1-\sum \limits_{j=1}^n{\left(\frac{a_{ij}}{A}\right)}^2\right] $$

$$ \mathrm{DIVISION}=\left[1-\sum \limits_{j=1}^n{\left(\frac{a_{ij}}{A}\right)}^2\right] $$

![]() $ {a}_{ij} $

is the size of patch

$ {a}_{ij} $

is the size of patch

![]() $ ij $

.

$ ij $

.

![]() $ A $

is the total landscape area. The index ranges from 0 to 1, with a greater number indicating more patch brokenness and landscape complexity.

$ A $

is the total landscape area. The index ranges from 0 to 1, with a greater number indicating more patch brokenness and landscape complexity.

-

(e) Landscape Shape Index (LSI; unitless).

![]() $ E $

is the total length (m) of edges in the landscape, and

$ E $

is the total length (m) of edges in the landscape, and

![]() $ \mathrm{A} $

is the total landscape area. An index value >0 indicates a greater degree of regularity in patch shape.

$ \mathrm{A} $

is the total landscape area. An index value >0 indicates a greater degree of regularity in patch shape.

-

(f) Largest Patch Index (%). The percentage of the area of the largest patch in relation to the total landscape area. The index ranges from 0 to 100, with a greater number indicating that the landscape is dominated by larger patches.

-

(g) Patch Density (m/m2). The number of patches of either vegetated or bare divided by the total landscape area. A greater value of the index indicates lower landscape heterogeneity.

-

(h) Percentage of Landscape (%). The percentage of the area of a particular patch in relation to the total landscape area. The index ranges from 0 to 100, with a greater number indicating a greater dominance of that patch type in the landscape.

Landscape indices were calculated using Fragstats 4.2.1 (https://fragstats.org/). Skewness was calculated from the “moments” R package (Komsta and Novomestky, Reference Komsta and Novomestky2015). Figures were created using the “ggplot2” package (Wickham, Reference Wickham2016) in R 3.4.3 version (R Core Team, 2018).

Structural equation model

We used SEM (Grace, Reference Grace2006) to assess the mechanisms most highly related to ecosystem structure (Hypothesis 3). SEM is used to explore the direct and indirect effects of the degree of encroachment on ecosystem structure (patch condition and vegetation distribution pattern), with climate and shrub community characteristics acting as covariates to take into account other confounding factors. In the a priori model (Supplementary Figure S1), we predicted that climate would have direct effects on ecosystem structure, as well as indirect effects mediated by the degree of shrub encroachment and shrub community characteristics. We expected that the magnitude of encroachment would either directly affect ecosystem structure or exert indirect effects by altering shrub community characteristics. Overall, goodness-of-fit probability tests were performed to determine the absolute fit of the best models, using the χ 2 statistic. The best-fit model was selected with low χ 2 and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA <0.05) and high goodness-of-fit index (GFI) and R 2. Analyses were performed using AMOS 22 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) software.

Results

Variation in the shrub community characteristics and patch condition with greater shrub encroachment

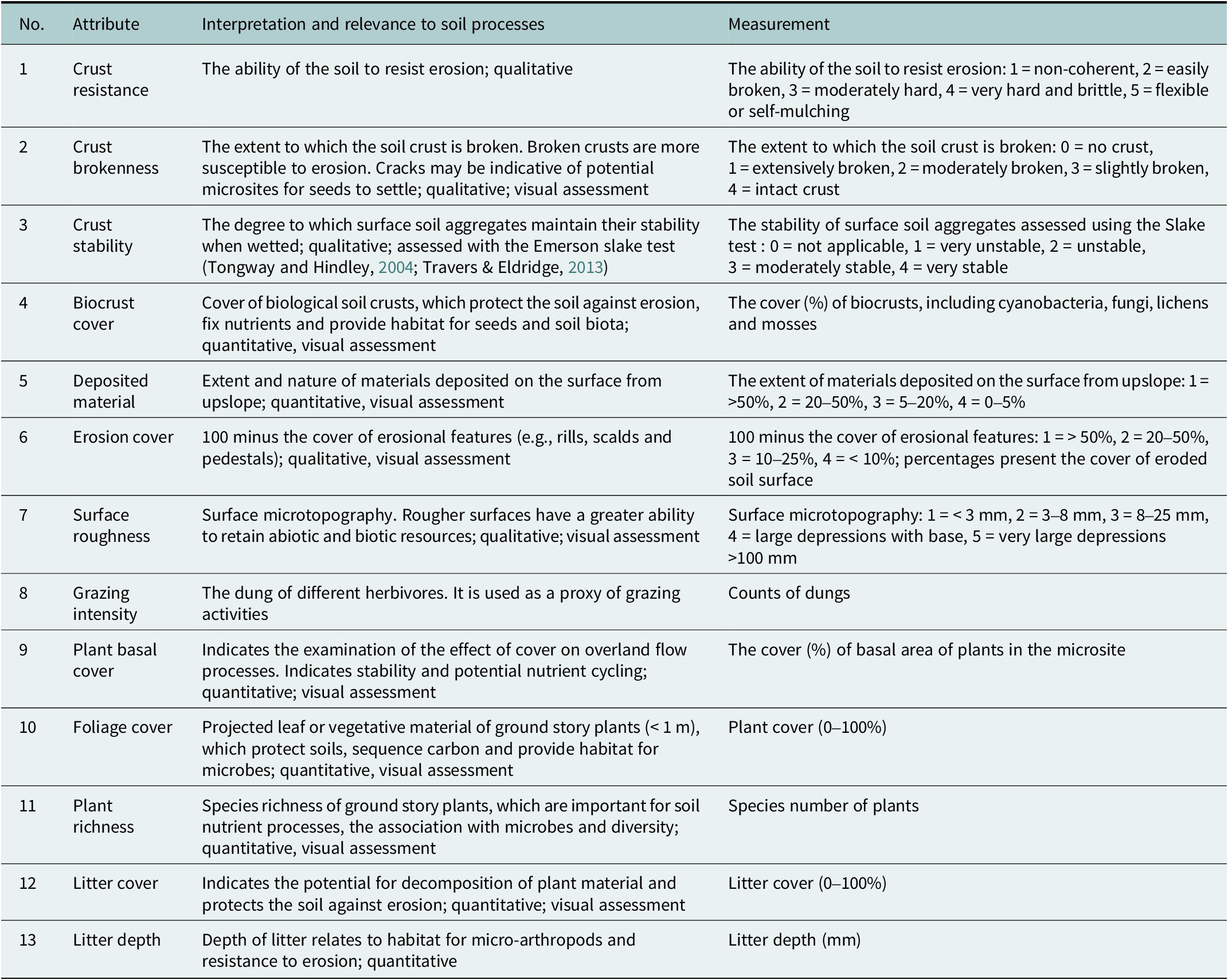

The structure and the size distribution of shrub communities varied markedly with increasing encroachment (Figure 3). Shrub abundance generally increased with shrub encroachment. Shrubs tended to be larger, characterized by taller stems, wider canopies and more branches as shrub encroachment increased (P < 0.05). Shrub size generally became more variable (canopy size and number of branches) in heavily encroached sites.

Figure 3. Variation in the shrub community characteristics (the mean, variance, kurtosis and skewness of shrub branch abundance, canopy cover [CD], DBH and shrub height [Ht]) of shrubs along shrub encroachment gradient (square root of shrub cover) and (b) the visualized summary diagram of variation in community characteristics with only significant results shown. * in (a and b) indicates significant (P < 0.05) linear relationships (Supplementary Table S2).

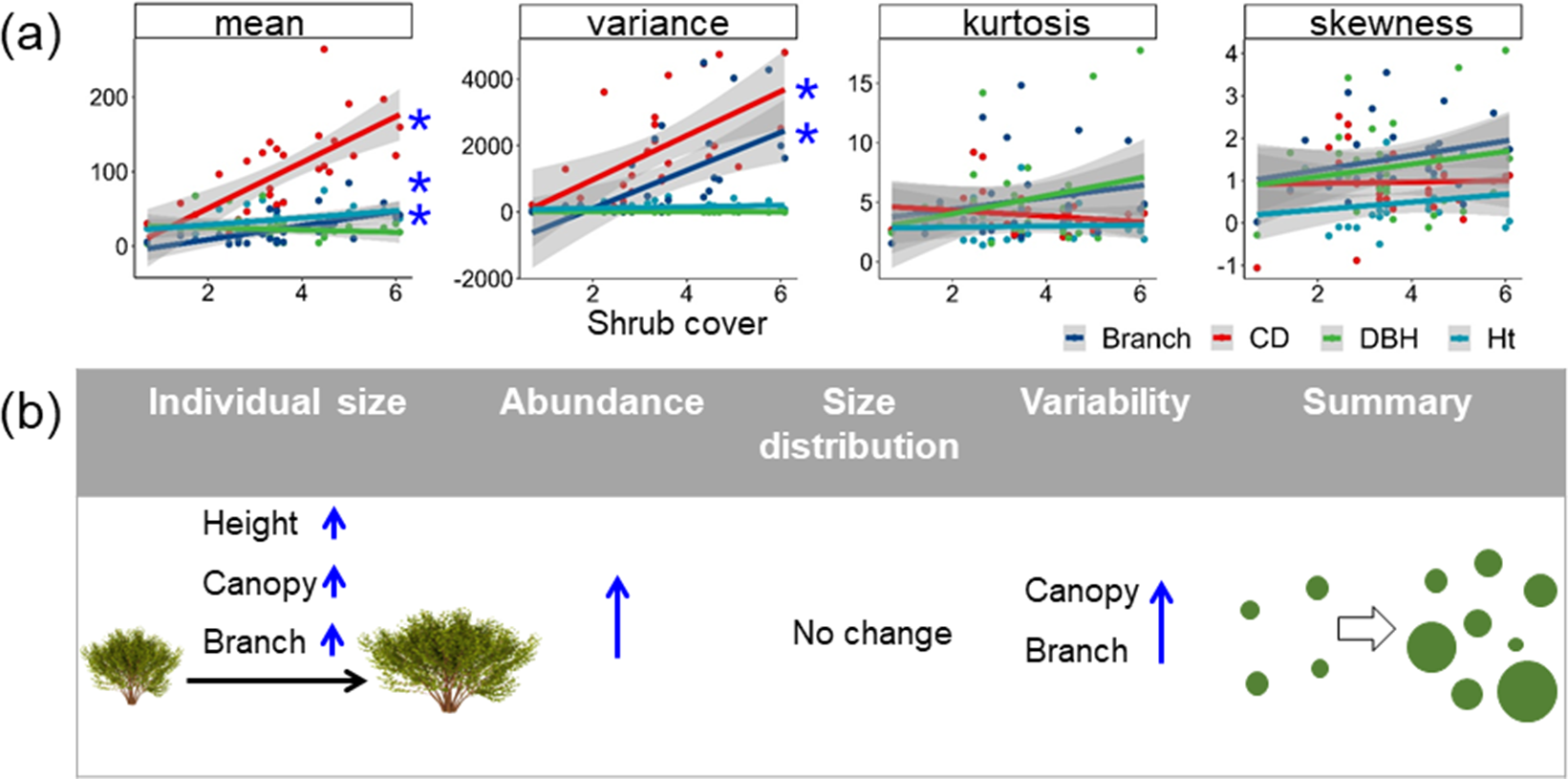

Across the encroachment gradient, the surface beneath shrubs had more and thicker litter than within grass patches (P < 0.05; Figure 4a). The soil surface was marginally rougher in shrub patches than in grass patches, which were less exposed to grazing and therefore had slightly less dung as encroachment intensified, though not significant (Figure 4b). Beneath the grass, crust stability declined markedly (P < 0.05) as encroachment intensified (Figure 4b). We found no evidence of significant dissimilarity in soil and vegetation attributes between shrub and grass patches in relation to intensifying encroachment (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 4. (a) Difference in patch condition between shrub patches (green) and interspaced grass patch (yellow) and (b) variation of patch condition in shrub patch (green) and the interspaced grass patch (yellow) along shrub encroachment gradient (square root of shrub cover) fitted with linear regression (solid line). * in (a and b) indicates significant (P < 0.05) linear relationships. Results of linear regression are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

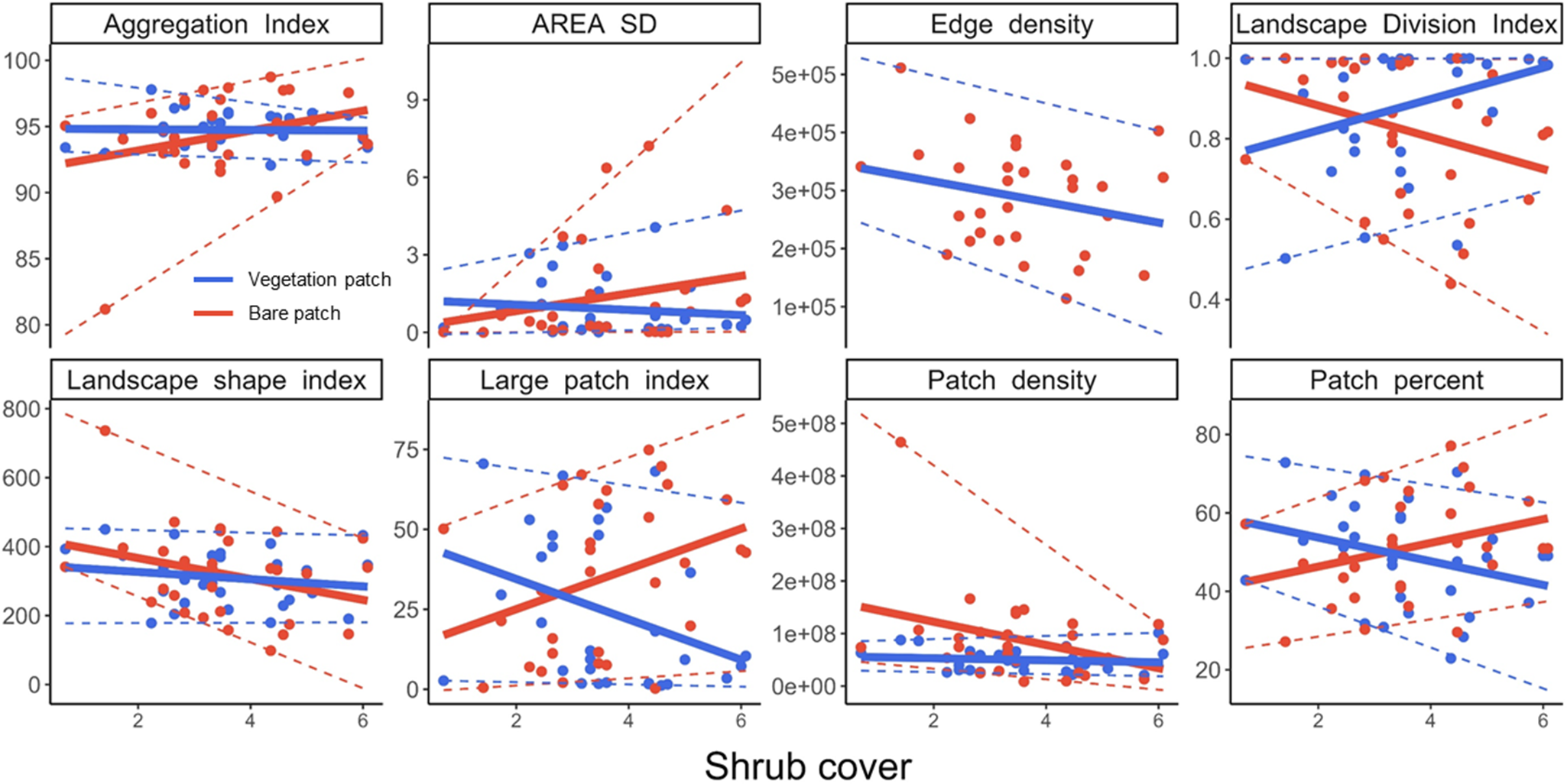

Variation in spatial distribution patterns of patches with greater shrub encroachment

The spatial organization of vegetation and bare patch varied with increases in shrub cover (Figure 5). Increasing encroachment and therefore greater shrub cover were associated with more broken vegetation patches, with greater landscape division (P = 0.062, marginally significant). Conversely, the size of bare patches increased with increasing encroachment, with declines in patch density (P = 0.059) but increases in large patch index (P = 0.063, marginally significant).

Figure 5. Variation in the spatial distribution pattern of patches along the gradient in shrub encroachment (square root of shrub cover) fitted with linear regression (solid line) and quantile regression (dotted line, 5th and 95th) for vegetation patches (blue) and bare patches (red). AREA SD, standard deviation of patch area. Results of linear regression are shown in Supplementary Table S4.

Impact of shrub encroachment on patch condition and spatial distribution pattern of patches

We further explored the mechanisms of shrub encroachment on influencing patch condition and the spatial distribution of patches (Figure 6). We found that community structure and patch condition were both related to the degree of encroachment. Greater shrub abundance was associated with reduced shrub structure (shorter and narrower plants) but enhanced soil surface roughness beneath shrub patches. Conversely, greater shrub cover or abundance enhanced shrub structure (height and canopy) but reduced patch dissimilarity among shrubs and the interspaces. Although the spatial distribution pattern of patches was not significantly related to the factor, the degree of shrub encroachment (abundance and shrub cover) and shrub community structure (canopy) were major driving factors (Figure 6b). For climate variables, mean annual temperature played an important role in driving both patch condition and spatial pattern, with higher temperature enhancing surface roughness under shrub patches, intensifying landscape brokenness (higher landscape division value) and reducing the proportion of large patches (low large patch index value).

Figure 6. (a) Mechanisms associated with patch condition and spatial distribution pattern of patches and (b) the standardized total effect. Factors are climate (aridity [AI] and mean annual temperature [TEMP]), encroachment magnitude (shrub cover [COVR] and shrub abundance [ABUN]), shrub community (shrub height [HT] and shrub canopy [CANO]), patch condition (surface roughness of soil under shrubs [SURF], grazing intensity indicated by total livestock dung under shrubs [GRAZ] and niche dissimilarity between shrubs and grasses [DISSI]) and spatial distribution pattern of patches (large patch index and landscape division index). The detailed a priori model structure is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Model fit: χ2 = 2.34, degrees of freedom (df) 10, P = 0.13, R2 = 0.26 (patch dissimilarity), 0.39 (grazing), 0.67 (surface roughness), 0.38 (large patch index) and 0.36 (landscape division index), RMSEA = 0.22, N = 30.

Discussion

Our study provides strong empirical evidence that the response of ecosystem structure to shrub encroachment varies with the degree of encroachment. As shrub encroachment intensified, the soil surface condition beneath shrub patch supported more litter and was exposed to less grazing, and the site comprised larger bare patches. Moreover, we found that both patch condition and spatial distribution pattern of patches were shaped mainly by the magnitude of shrub encroachment (cover) rather than through the changes in characteristics of shrub communities. Overall, our work reveals the response of ecosystem structure to intensifying shrub encroachment. Thus, studies of shrub encroachment and efforts to manage shrub encroachment need to be cognizant of the development stages of shrub encroachment.

Response of ecosystem structure depends on the degree of shrub encroachment

Our results indicate that the response of patch condition and spatial distribution pattern of patches significantly changes with the degree of shrub encroachment. For the condition beneath shrub patches, there are greater accumulation of litter, less exposure to grazing and dominance of a less stable soil crust as shrub encroachment intensifies. This can be explained by distinct plant traits. Shrubs are long-lived and have woody stems, wide canopies, relatively unpalatable leaves and deep roots that can make it difficult for herbivores to penetrate the clumps (Westoby, Reference Westoby1979). As encroachment intensifies, these shrubs form dense patches that are more resistant to grazing disturbance (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Soliveres, Bowker and Val2013). Moreover, shrubs have a competitive advantage over grasses as the climate becomes more variable (Knapp et al., Reference Knapp, Briggs, Collins, Archer, Bret-Harte and Ewers2008; Archer et al., Reference Archer, Andersen, Predick, Schwinning and Woods2017; Kühn et al., Reference Kühn, Tovar, Carretero, Vandvik, Enquist and Willis2021). The transfer of fine, nutrient-rich sediments from poorly vegetated grazed interspaces into shrub canopies through processes of wind and water erosion (Ravi et al., Reference Ravi, D’Odorico, Breshears, Field, Goudie, Huxman, Li, Okin, Swap, Thomas, van Pelt, Whicker and Zobeck2011; D’Odorico et al., Reference D’Odorico, Okin and Bestelmeyer2012) reinforces islands of fertility (fertile islands) beneath shrub. These biogeochemical hotspots (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Ding, Dorrough, Delgado-Baquerizo, Sala, Gross, le Bagousse-Pinguet, Mallen-Cooper, Saiz, Asensio, Ochoa, Gozalo, Guirado, García-Gómez, Valencia, Martínez-Valderrama, Plaza, Abedi, Ahmadian, Ahumada, Alcántara, Amghar, Azevedo, Ben Salem, Berdugo, Blaum, Boldgiv, Bowker, Bran, Bu, Canessa, Castillo-Monroy, Castro, Castro-Quezada, Cesarz, Chibani, Conceição, Darrouzet-Nardi, Davila, Deák, Díaz-Martínez, Donoso, Dougill, Durán, Eisenhauer, Ejtehadi, Espinosa, Fajardo, Farzam, Foronda, Franzese, Fraser, Gaitán, Geissler, Gonzalez, Gusman-Montalvan, Hernández, Hölzel, Hughes, Jadan, Jentsch, Ju, Kaseke, Köbel, Lehmann, Liancourt, Linstädter, Louw, Ma, Mabaso, Maggs-Kölling, Makhalanyane, Issa, Marais, McClaran, Mendoza, Mokoka, Mora, Moreno, Munson, Nunes, Oliva, Oñatibia, Osborne, Peter, Pierre, Pueyo, Emiliano Quiroga, Reed, Rey, Rey, Gómez, Rolo, Rillig, le Roux, Ruppert, Salah, Sebei, Sharkhuu, Stavi, Stephens, Teixido, Thomas, Tielbörger, Robles, Travers, Valkó, van den Brink, Velbert, von Heßberg, Wamiti, Wang, Wang, Wardle, Yahdjian, Zaady, Zhang, Zhou and Maestre2024) also act as refugia for plants and animals against climate extremes and physical disturbance (Dean et al., Reference Dean, Milton and Jeltsch1999; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Trinogga, Wiegand, du Toit, Okubamichael, Reinsch and Schleicher2018). Conversely, herbaceous plants in the interspaces are both grazed and abraded by aeolian sediments (Li et al., Reference Li, Ravi, Wang, Pelt, Gill and Sankey2022), thereby supporting both a less stable and more broken soil crust. These effects would likely intensify with increasing encroachment due to the lower availability of forage plants under conditions of greater shrub dominance.

Compared with the positive effect on ecosystem structure for patch condition, we found that increasing encroachment was associated with reduced landscape connectivity (i.e., the connectivity among vegetation patches) due to the heterogeneous distribution of resources that characterizes patchy landscapes. This can be explained by the self-sustaining cycling of resource redistribution driven by the interactions among hydrological and aeolian processes and fire regimes in drylands (Okin et al., Reference Okin, Heras, Saco, Throop, Vivoni, Parsons, Wainwright and Peters2015; Li et al., Reference Li, Ravi, Wang, Pelt, Gill and Sankey2022). In grasslands, erosion processes redistribute water and soil resources from grass to shrub patch, with the greater capacity of nutrient scavenging by shrubs further reinforcing such resource heterogeneity, thereby forming fertile islands beneath shrubs (D’Odorico et al., Reference D’Odorico, Fuentes, Pockman, Collins, He, Medeiros, DeWekker and Litvak2010). The dominance and coalescence of fertile islands lead to the development of a large “resource–sink” pattern (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Fu and Zhao2008). This pattern is maintained by processes of redistribution of resources driven by wind and water analogous to the fertile island phenomenon (Ying et al., Reference Ying, Haiping, Bojie and Cheng2017). Exacerbated by regional droughts, soil erosion, resource depletion and vegetation loss surrounding large woody aggregations reinforce the establishment and expansion of shrubs, forming self-sustaining cycles of resource redistribution, contributing to the irreversible transition from grass-dominated to shrub-dominated systems (Scheffer et al., Reference Scheffer, Carpenter, Lenton, Bascompte, Brock, Dakos, van de Koppel, van de Leemput, Levin, van Nes, Pascual and Vandermeer2012; Bestelmeyer et al., Reference Bestelmeyer, Peters, Archer, Browning, Okin, Schooley and Webb2018). A widely studied example of this phenomenon is embodied in the shrubland desertification paradigm of the southwestern United States (Schlesinger et al., Reference Schlesinger, Reynolds, Cunningham, Huenneke, Jarrell, Virginia and Whitford1990).

Contrary to our third hypothesis, we failed to detect any evidence of an impact of shrub encroachment on the spatial distribution pattern of patches via influencing patch condition. This could potentially be due to interactions with endogenous drivers between patches. For example, declines in forage availability can lead to more concentrated grazing of limited herbaceous material in an effort to compensate for the loss in livestock production (van de Koppel et al., Reference van de Koppel, Rietkerk, van Langevelde, Kumar, Klausmeier, Fryxell, Hearne, van Andel, de Ridder, Skidmore, Stroosnijder and Prins2002). Furthermore, reductions in grasses in the interspaces under grazing and drought would disconnect herbaceous fuel pathways, thus reducing fire frequency in grasslands and favoring the expansion of shrubs (Hodgkinson, Reference Hodgkinson1998). Consequently, a continuous grassland landscape is replaced by a mosaic of shrub patches, which reduce the structural connectivity of the landscape and therefore the transfer of material among landscape elements (Larsen et al., Reference Larsen, Choi, Nungesser and Harvey2012; Turnbull and Wainwright, Reference Turnbull and Wainwright2019). Such an effect would be strengthened under hotter climatic conditions, with higher mean annual temperature exacerbating the fragmentation of vegetation patches (higher landscape division value) and reducing the proportion of large patches. Hotter conditions would promote evapotranspiration and reduce water availability, which would give shrubs competitive advantages over grasses due to their deeper root systems (Deng et al., Reference Deng, Li, Shi and Hu2021). This would lead to an intensification of shrub expansion and produce a more fragmented landscape.

Management implications

Increasing shrub encroachment changed vegetation structure beneath patches (e.g., greater fertile island effect) but resulted in reduced landscape connectivity by increasing patch isolation. Such contrasting effects are likely to have important impacts on shrubland- and grassland-dependent biota. For example, arthropods such as spiders that move and feed beneath patches in mixed grassland–shrubland systems would benefit from the edge effects that produce distinct foraging habitats (Webb and Hopkins, Reference Webb and Hopkins1984; Daryanto and Eldridge, Reference Daryanto and Eldridge2012). Shrub consolidation into larger patches will likely disadvantage these taxa by reducing surface heterogeneity within vegetation patches. Community composition of spiders has also been shown to vary with broader changes in land-use change (e.g., forest converted to farmland; Major et al., Reference Major, Gowing, Christie, Gray and Colgan2006). Plant communities with diverse structures such as those with a greater variation in patch size or internal structure (height and configuration) provide a greater range of habitat, potentially favoring a wider species pool of spiders (Klimm et al., Reference Klimm, Bräu, König, Mandery, Sommer, Zhang and Krauss2024). These beneficial effects from shrub patches would ensue with increasing shrub cover, consistent with studies showing that ant and beetle diversity increases with increasing shrub encroachment to at least 20% shrub cover (Blaum et al., Reference Blaum, Seymour, Rossmanith, Schwager and Jeltsch2009, Eldridge and Soliveres, Reference Eldridge and Soliveres2015). Yet, shrub encroachment is unlikely to benefit biota that operate at intermediate scales greater than shrub-interspace distances, with higher predation costs for animals that need to move between shrubby and open habitats (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Kotler and Valone1994). Further, there are likely to be major trade-offs when evaluating the encroachment effect at the broader level, with encroachment sites favoring shrubland obligate at the expense of grassland-obligate taxa (Coffman et al., Reference Coffman, Bestelmeyer, Kelly, Wright and Schooley2014).

Moreover, the effect of encroachment on ecosystem structure depends highly on the degree of encroachment, with greater encroachment associated with healthier patch conditions but less connectivity among patches. The “regime shift hypothesis” suggests that as shrub encroachment intensifies, grassland ecosystems transition from a stable herb-dominated state to a shrub-dominated state, which alters ecosystem functions by altering ecosystem structure (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Li, Li, Zhang, Zhang, Li, Zhao, Jiang and Ma2013). Empirical studies reveal that moderate encroachment supports a greater species and functional diversity (Ding et al., Reference Ding and Eldridge2020). Furthermore, synthesis studies reveal that ecosystem productivity peaks at ~15% shrub cover, while carbon sequestration peaks at ~30% cover (Eldridge and Soliveres, Reference Eldridge and Soliveres2015). Thus, the extent of encroachment is critically important and will determine the options available for shrub removal and the likely impacts of shrubs on ecosystem functions.

Conclusion

Our study provides novel evidence that the response of ecosystem structure to shrub encroachment depends on the degree of encroachment. The soil surface beneath shrubs was rougher and had more litter, and the shrubs were typically larger as encroachment expanded. Conversely, connectivity collapses under shrub aggregation, resulting in a more fragmented landscape. Furthermore, our study demonstrates that either the patch condition or the spatial distribution pattern of patches is regulated by the magnitude of shrub encroachment rather than by shrub community changes. This indicates that the magnitude of encroachment is crucial in regulating changes in ecosystem structure and therefore needs to be taken into account when making decisions regarding shrub management. Under predicted drier climates, shrub encroachment is likely to intensify, resulting in a more heterogeneous landscape characterized by a shrub community forming a patchwork of fertile islands. Such structural changes will likely alter ecosystem services provided by woody plants and affect the well-being of biotic and abiotic systems.

Open peer review

For open peer review materials, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/dry.2025.10010.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/dry.2025.10010.

Author contribution

J.D. designed the research. J.D., Y.H., X.G. and Y. Y. collected the data. J.D., Y.H. and Y.W. performed the statistical analyses. J.D. wrote the first draft, and W.Z., J.H. and D.E. critically revised the manuscript.

Financial support

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Project (grant nos. 32201324 and 42571061 to J.D. and 42007057 to J.H.), the Young Elite Scientist Sponsorship Program by CAST (YESS2024005 to J.D.), the Outstanding Research Cultivation Project of the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Beijing Normal University (2253200003 to J.D.) and the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2024NSFSC0106 to J.H.). D.J.E. is supported by the Hermon Slade Foundation.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Comments

Cambridge Prisms: Drylands

Dear Editor

We would like you to consider the manuscript “Does scale matter: the response of ecosystem structure to shrub encroachment varies with spatial scale in a semiarid grassland” as a Research paper contribution to Cambridge Prisms: Drylands.

Grasslands are a major biome in drylands, supporting forage production and multiple ecosystem functions. However, under global climate change and intensified human activities, expansion in shrubs are encroaching grasslands worldwide. Shrub encroachment can largely alter ecosystem structure from multiple scales such as the structure of plants, communities and landscape patterns, which will change the function and services of grassland. However, the mechanisms by which ecosystem structure responds to shrub encroachment from finer to coarser scales remain poorly understood. Such a knowledge gap makes it more challenging to manage grasslands under different levels of encroachment, particularly during the early stages of encroachment when treatment is more effective.

To solve this issue, we sampled niche conditions beneath individual shrubs (plant scale) and the size distribution of shrubs (community scale) and extracted landscape indices (landscape scale) using drone data along an extensive shrub encroachment gradient in a semiarid grassland in Inner Mongolia, China. Our results show that as shrub encroachment intensifies, the soil surface beneath shrubs supported more litter, was exposed to less grazing, the shrub community became more variable in size, and the landscape comprised larger bare patches. Moreover, landscape pattern was shaped mainly by the magnitude of shrub encroachment (cover, abundance) rather than either community structure or the condition of the soil surface beneath shrubs.

Together, these data provide novel evidence that the response of ecosystem structure to shrub encroachment depends on the spatial scale under consideration, indicating that shrub management need to be cognizant of the scale at which encroachment is operating. This makes our work highly appealing to ecologists, land managers and policy makers involved in the management of shrub encroachment and restoration of drylands, and therefore readers of Cambridge Prisms: Drylands.

All authors have read and agree with the contents of the manuscript, and there are no any actual or potential conflict of interest among all authors. We certify that this submission is an original work, and it is not under review at any other publication.

Yours sincerely

Jingyi Ding

August, 31th 2024