Democratic backsliding is difficult to measure (Waldner & Lust, Reference Waldner and Lust2018), but academic and popular pronouncements about it are on the rise (Croissant & Diamond, Reference Croissant and Diamond2020; Fomunyoh, Reference Fomunyoh2020; Heller, Reference Heller2020; Kelemen & Orenstein, Reference Kelemen and Orenstein2016; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019; Lührmann & Lindberg, Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Mechkova et al., Reference Mechkova, Luhrmann and Lindberg2017; Mickey et al., Reference Mickey, Levitisky and Way2017; Norris, Reference Norris2017; Sitter & Bakke, Reference Sitter and Bakke2019). Although democratic backsliding is hard to pin down, backsliders are easily identified. In contemporary liberal democracies, the political actors most closely associated with an agenda of democratic erosion are mainly those of the radical‐right (Betz, Reference Betz and Rydgren2005; Mudde, Reference Mudde2019; Sedgwick, Reference Sedgwick2019; Shaffer, Reference Shaffer2019). The defining ideological features of the radical‐right, authoritarianism and nativism (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007), translate into platforms and policies aimed at weakening liberal democratic norms.

Studies assessing the growing success of radical‐right parties in liberal democracies typically focus on their electoral success (Mudde, Reference Mudde2019), their ability to shift the policy positions of other parties (Abou‐Chadi & Krause, Reference Abou‐Chadi and Krause2020) and their ability to push new issues onto the political agenda (Hobolt & de Vries, Reference Hobolt and de Vries2015). The ability of radical‐right movements and parties to influence politics and rise to power rests, however, on being accepted as legitimate by political players, allies, coalition partners and the public (Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019; Mudde, Reference Mudde2019; Pytlas, Reference Pytlas, Herman and Muldoon2018). Therefore, explaining the success of radical‐right movements and their illiberal, anti‐democratic agendas in incrementally moving to the political mainstream requires understanding in depth the processes by which they gain public acceptance and legitimacy.

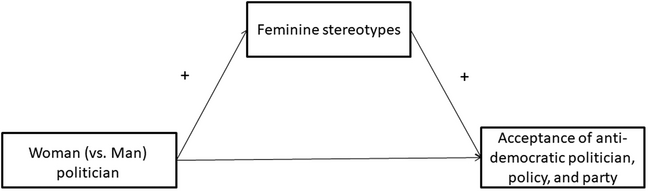

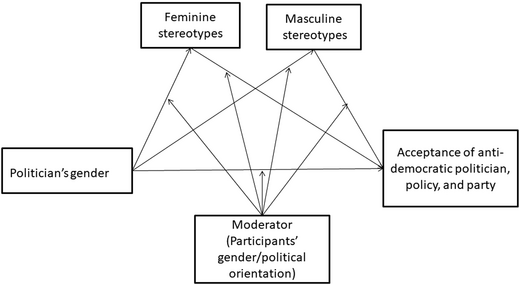

We argue that a key factor in this process is the growing visibility of women actors in anti‐democratic politics. In past years, women politicians within radical‐right movements and parties, traditionally referred to as ‘Männerparteien’ or ‘men's parties’ (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007), have been gaining leadership prominence and visibility. It has even been suggested that the growing visibility of women politicians in radical‐right politics reflects a strategic effort by these movements and parties to project a mainstream image and to soften public perceptions of their agendas (Weeks et al., Reference Weeks, Meguid, Kittilson and Coffé2022). The present research is the first to systematically examine whether women's increased visibility in radical‐right politics, whether strategic or not, affects public acceptance and legitimization of anti‐democratic policies, and to test a potential mechanism underlying this effect, across various democracy‐eroding policies and across three socio‐political contexts. Specifically, we systematically examine the gender mainstreaming model (GMM)Footnote 1of democratic backsliding, which incorporates two hypotheses: (a) citizens demonstrate greater acceptance of anti‐democratic policies, of the politicians and of the party promoting them, when these policies are advocated by a woman rather than a man politician; (b) this mainstreaming effect is explained by the attribution of feminine stereotypes to women (versus men) politicians, which softens the masculine stereotypes voters hold about radical‐right parties and their anti‐democratic policy agendas. Our model, which integrates these two hypotheses, is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hypothesized gender mainstreaming model (GMM).

This model draws on previous work by Ben Shitrit and colleagues (Reference Ben Shitrit, Elad‐Strenger and Hirsch‐Hoefler2021), which provided initial evidence for the effects of a politician's gender on support for a specific radical‐right policy, in Israel: removing the judicial review power of the Supreme Court. This study, which was conducted in the Israeli context, demonstrated that support for this policy was higher when promoted by a woman (vs. a man or gender‐neutral) politician, and that this mainstreaming effect was mediated by the attribution of warmth, but not of competence, to the politician. The current studies develop and extend these findings both theoretically and empirically: First, we directly examine a crucial assumption underlying the hypothesized mainstreaming effect – namely, that perceptions of the supporters of anti‐democratic policies and of the image of the parties promoting these policies are gendered (Studies 1a‐c). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that citizens not only attribute a masculine (versus feminine) image to radical‐right parties, but also perceive anti‐democratic policies to be supported more by men than by women. Second, while Ben Shitrit et al. (Reference Ben Shitrit, Elad‐Strenger and Hirsch‐Hoefler2021) provided initial evidence for gender mainstreaming effects concerning a specific policy reflecting executive aggrandizement, our model extends to democracy‐erosion more broadly. Specifically, our Studies 2a‐c examined the effect of politicians’ gender on public support for a wide range of policies, representing both authoritarian policies seeking to challenge democratic institutions, and civil rights eroding policies. We did so by experimentally manipulating the politician's gender, while keeping the policies constant. Alongside offering the first systematic test of gender mainstreaming across a wide range of democracy‐eroding policies, our current studies extend the initial findings in two additional ways: First, we measured the attribution of a wider range of gender stereotypes, both feminine and masculine, to the politicians, as potential mediators of the relation between politicians’ gender and public support. Second, we examined the applicability of the model across three socio‐political contexts – Israel, the United States and Germany. The variation in policies, stereotypes and contexts carries both theoretical and empirical implications. It broadens the theoretical applicability of the gender mainstreaming phenomenon and enables the examination of the potential boundary conditions of gender mainstreaming effects. This aligns with broader calls for replicability in empirical social sciences and supports the application of ‘stimulus sampling’ principles in quantitative research (see Elad‐Strenger et al., Reference Elad‐Strenger, Proch and Kessler2020; Proch et al., Reference Proch, Elad‐Strenger and Kessler2018).

We conducted our studies in Israel, Germany and the United States using nationally representative samples. These three countries share important similarities: (a) they are all considered democracies; (b) they all have experienced the growing influence of radical‐right democratic backsliding within mainstream politics; and (c) in all three countries, radical‐right women politicians have become increasingly visible. At the same time, the three countries have substantially different political systems, histories of radical‐right influence on government and trajectories of women's political representation. Despite these differences, our first set of studies (1a‐c) confirms that citizens in all three countries associate parties promoting anti‐democratic policies with masculinity as opposed to femininity, and believe that support for anti‐democratic policies is greater among men than women. Our second set of studies (2a‐c) provides experimental support for the GMM (Figure 1) in segments of society that tend to be particularly apprehensive about anti‐democratic agendas: In Israel and Germany, left‐wing participants perceived anti‐democratic policies as more legitimate and acceptable when these were promoted by a fictitious woman rather than by a fictitious man politician. In the United States, we observed the same effect among women, rather than left‐wing, participants. In all three countries, the mechanism driving the mainstreaming effect was the attribution of feminine, but not masculine, stereotypes to women politicians. We argue that these feminine stereotypes soften the masculine stereotypes that voters attribute to radical‐right parties and to their anti‐democratic policy agendas.

This research sheds new light on the intersection between gender and anti‐democratic backsliding. It is the first to empirically demonstrate that voters perceive support for democracy‐eroding policies as gendered, attributing it more to men than to women, and perceive the image of parties promoting such policies as more masculine than feminine. It is also the first to systematically demonstrate the effect of politicians’ gender on public support for democracy‐eroding policies and parties, across a variety of policies and in three socio‐political contexts, using an experimental design which ‘isolates’ the effects of the politician's gender from specific characteristics of any given politician. Furthermore, it systematically demonstrates the role of feminine gender stereotypes in mediating this effect, that is, in mitigating the apprehension of voters regarding the anti‐democratic policies of the radical‐right. Finally, it shows that across socio‐political contexts, the audiences susceptible to gender mainstreaming are precisely those that are often particularly repelled by radical‐right agendas and their masculine image: left‐wing voters and women.

Democratic backsliding and gender

Democratic backsliding is broadly defined as the ‘discontinuous and incremental erosion of democratic attributes’ and the ‘deterioration of qualities associated with democratic governance’ (Waldner & Lust, Reference Waldner and Lust2018, pp. 95 and 109). Consistent with a conceptualization of democracy that ties democracy to freedom, backsliding has also been described as ‘any change of a political community's formal or informal rules which reduces that community's ability to guarantee freedom of choice, freedom from tyranny, or equality in freedom’ (Jee et al., Reference Jee, Lueders and Myrick2022, p. 755). Democratic backsliders typically target two features of liberal democracy: checks on executive power, which they seek to weaken by promoting executive aggrandizement (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016), and civil rights, which they seek to restrict. The restriction of civil rights is often characterized by attacks on ‘equality in freedom’ (Jee et al., Reference Jee, Lueders and Myrick2022, p. 755) targeting minority groups, whether native or immigrant (Vachudova, Reference Vachudova2020). By pushing for authoritarianism and nativism, which are considered as its defining features (Mudde, Reference Mudde2019), the radical‐right gradually nudges liberal democracy toward an ‘illiberal democracy’.

Scholars examining backsliding through a gender lens have focused mainly on the effect of democratic backsliding on gender equality. This literature has identified parallel trends where the backsliding of democratic norms or erosion of democratic governance is accompanied by a backlash against gender equality, often leading to backsliding in this area too (Aksoy, Reference Aksoy2018; Arat, Reference Arat2021; Biroli, Reference Biroli2019; Lombardo et al., Reference Lombardo, Kantola and Rubio‐Marin2021; Paternotte & Kuhar, Reference Paternotte and Kuhar2018; Roggeband & Krizsán, Reference Roggeband and Krizsán2020; Verloo & Paternotte, Reference Verloo and Paternotte2018). It may be argued that erosion of gender equality and women's rights should in itself constitute a key indicator of democratic backsliding, as the actors that pursue democratic erosion often also promote policies that undermine women's equality (Chenoweth & Marks, Reference Chenoweth and Marks2022).

But research has paid much less attention to the effect of gender politics on democratic backsliding. A paradoxical aspect of this backlash against gender equality is that in liberal democracies, women are becoming increasingly visible within the ranks of radical‐right parties (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2018; Och & Williams, Reference Och and Williams2022). Yet, their growing inclusion and visibility did not significantly moderate these parties’ tendency to advance policies that erode gender equality. What, then, does this increased visibility of women in radical‐right politics achieve? Recent evidence suggests that the rise in the representation of women in higher positions in radical‐right parties has been a strategic move to gain public support (Chrisafis et al., Reference Chrisafis, Connolly and Giuffrida2019; Gutsche, Reference Gutsche2018). Weeks and colleagues (Reference Weeks, Meguid, Kittilson and Coffé2022) demonstrated that radical‐right parties increase women's representation when these parties perform poorly electorally and when the gender gap in their voters is particularly large (i.e., when women are much less likely to vote for them than men).

The strategic use of women's descriptive representation is not new (Park & Liang, Reference Park and Liang2021). In their adoption of this strategy, democratic backsliders have taken a page out of the authoritarian playbook. For example, Tripp (Reference Tripp2019) has shown that Arab autocracies have historically used women's rights and representation to improve their image at home and abroad, without necessarily making significant democratic reform. Tripp (Reference Tripp2013) also demonstrated that authoritarian regimes in Africa have adopted women's quotas to the same degree as democracies have. Additional studies provide further evidence of strategic descriptive representation under electoral authoritarianism (Dahlerup, Reference Dahlerup2007; David & Nanes, Reference David and Nanes2011; Kroeger & Kang, Reference Kroeger and Kang2022) and have termed the phenomenon ‘autocratic gender‐washing’ (Bjarnegård & Zetterberg, Reference Bjarnegård and Zetterberg2022). New evidence suggests that this strategy has been effective in authoritarian contexts. In large‐scale experiments, Bush and Zetterberg (Reference Bush and Zetterberg2021) found that larger quotas for women's representation in parliament in electoral autocracies enhance these countries’ international reputations for democracy.

The question whether women's heightened visibility within the contemporary radical‐right in liberal democracies also constitutes a deliberate strategy employed by democratic backsliders is a matter open to debate. Nonetheless, the question whether this increased visibility affects public acceptance of democratic backsliders in liberal democracies, and if so, why, remains largely unexplored.

Gender stereotypes, parties and policies

Vast research attests to the fact that gender stereotypes play a role in people's evaluation of women and men. While being ‘harsh,’ ‘strong,’ a ‘leader’, having ‘high abilities,’ and ‘high self‐esteem’ are typically considered masculine traits, being ‘warm,’ ‘sensitive,’ ‘likeable,’ ‘moral,’ ‘trustworthy’ are typically considered feminine traits (e.g., Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Fiske and Glick2008; Huddy & Terkildsen, Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993). Like women in general, women politicians tend to be attributed more feminine stereotypes than men politicians, by both men and women (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Bracken, Gidron, Horne, O'Brien and Senk2022; Barnes & Beaulieu, Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2014; Bauer, Reference Bauer2017; Benstead et al., Reference Benstead, Jamal and Lust2015; Dolan, Reference Dolan2014; Huddy & Terkildsen, Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; Koch, Reference Koch2000; Koch, Reference Koch2002; Matland & Tezcür, Reference Matland and Tezcür2011; McDermott, Reference McDermott1997; Sanbonmatsu, Reference Sanbonmatsu2002). In fact, given the strong link between masculinity and political leadership, women politicians who are perceived as displaying typical ‘feminine’ traits but lacking the typical ‘masculine’ attributes often face penalties. Consequently, they sometimes feel compelled to counteract gender stereotypes held by voters by emphasizing their ‘masculine’ qualities (Bauer & Sintia, Reference Bauer and Santia2022; Huddy & Terkildsen, Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993). Paradoxically, this effort can also subject them to criticism for being excessively masculine and insufficiently feminine (Cassese & Holman, Reference Cassese and Holman2018). Such a ‘double bind’ dilemma frequently forces women politicians to navigate both feminine and masculine expectations (Bauer & Sintia, Reference Bauer and Santia2022). Although gender stereotypes may seldom directly impact voter decision making, particularly when voters are well‐informed about the politicians (Brooks, Reference Brooks2013), it is evident that these stereotypes influence how women politicians’ strategic messages are perceived (Bauer & Santia, Reference Bauer and Santia2022; Kanthak & Woon, Reference Kanthak and Woon2015).

Research further suggests that voters may also evaluate parties, not only politicians, through the lens of gender stereotypes. Studies have found that right‐wing parties are often identified by both the public and the media with masculine stereotypes, and left‐wing parties with feminine stereotypes (Köttig et al., Reference Köttig, Bitzan and Petö2017; Rashkova & Zankina, Reference Rashkova and Zankina2017; Winter, Reference Winter2010). In the case of radical‐right parties, extant research has demonstrated the central role that masculinity has historically played in their self‐image and agendas (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2012; Blee, Reference Blee, Köttig, Bitzan and Petö2017; Engelberg, Reference Engelberg2017; Gökarıksel et al., Reference Gökarıksel, Neubert and Smith2019; Ralph‐Morrow, Reference Ralph‐Morrow2022; Snipes & Mudde, Reference Snipes and Mudde2020), so much so that they have been referred to as Männerparteien, or men's parties (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007). Indeed, women have traditionally been underrepresented in the leadership ranks of both radical‐right and traditional right‐wing parties in comparison to left‐wing parties (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2018, Och & Shames, Reference Och and Shames2018). Radical right parties often advocate conservative or neo‐conservative gender ideologies (Ben Shitrit, Reference Ben Shitrit2015, De Lange & Mügge, Reference De Lange and Mügge2015) and tend to focus on policy areas considered ‘masculine’ (for example immigration and law and order). Women have also tended to vote in lower numbers for radical‐right parties than have men, a phenomenon that has been termed “the radical‐right gender gap” (RRGG) (Donovan, Reference Donovan2022). Explanations for the RRGG include gender differences in socio‐economic experiences and populist attitudes, but also public stigmatization, prejudices and the style and ideological extremism of radical‐right parties (Coffé, Reference Coffé2018; de Bruijn & Veenbrink, Reference De Bruijn and Veenbrink2012; Deshpande, Reference Deshpande2009; Finnsdottir, Reference Finnsdottir2022; Givens, Reference Givens2004; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Van Der Brug, Dahlberg and Kokkonen2015; Immerzeel et al., Reference Immerzeel, Coffé and Van der Lippe2015; Norris, Reference Norris2005; Spierings & Zaslove, Reference Spierings and Zaslove2017).

Radical‐right democratic backsliders appear to be aware of their masculine image (Blum, Reference Blum, Köttig, Bitzan and Petö2017; Ralph‐Morrow, Reference Ralph‐Morrow2022), which may repel not only women but also left‐leaning voters. Can the increased visibility of women politicians in their ranks help radical‐right parties counter these prevailing gender stereotypes? In our three case studies, prominent radical‐right politicians such as Ayelet Shaked of the Yamina party in Israel, Alice Weidel of AfD in Germany and Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert in the United States Republican party have become familiar faces. Together with other prominent figures, such as Marine Le Pen in France, Georgia Meloni in Italy, Siv Jensen and Sylvi Listhaug in Norway, women increasingly occupy leading roles in radical‐right parties in many liberal democracies. We argue that women's increased visibility in radical‐right politics may not necessarily garner more votes from constituencies that tend to object to the radical‐right, that is, left‐wing voters and women, but it may soften these audiences’ apprehensions about the radical‐right. Viewing women politicians through the lens of feminine stereotypes may serve to counteract the historically attributed masculine image of radical‐right parties and policies, especially among those audiences who find this image particularly unappealing. In other words, the presence of women within radical‐right parties might moderate these audiences’ aversion to the radical‐right ideology and its policies.

The current studies

We examined the gender mainstreaming model of democratic backsliding (GMM) in three countries: Israel, Germany and the United States. All three countries are liberal democracies, where illiberal, anti‐democratic ideas and parties have been mainstreamed and normalized to various degrees. Traditionally, in Germany, radical‐right parties have not enjoyed significant support, failing to cross the 5 per cent electoral threshold at the national level. This changed in 2017, with the first‐time success of the radical‐right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) (Valentim & Widmann, Reference Valentim and Widmann2021). In the United States, radical‐right factions within the Republican party have come to dominate much of the GOP agenda, culminating in the ascendance of Trumpist or Trump‐like voices (Moreau, Reference Moreau2018). In Israel, over the past decades, there has been a steady rise in support for radical‐right agendas, especially with the largest right‐wing party, the Likud, increasingly forming alliances with parties promoting explicitly anti‐democratic agendas since 2009 (Elad‐Strenger et al., Reference Elad‐Strenger, Fajerman, Schiller, Besser and Shahar2013, Reference Elad‐Strenger, Halperin and Saguy2019, Reference Elad‐Strenger, Hall, Hobfoll and Canetti2021; Kremnitzer & Shany, Reference Kremnitzer and Shany2020; Shinar, Reference Shinar2021).

Because contextual features shape the variations in political conditions, structures and practices, and in gender stereotypes, we selected countries that would allow us to investigate the GMM in (a) different geographic and cultural contexts (North America, Europe and the Middle East); (b) different patterns of national and political identity formation and their relations to culture‐specific gender constructions; (c) different institutional structures (e.g., multiparty vs. two‐party systems); (d) different levels of conflict with perceived out‐groups; and (e) different degrees of the penetration of democracy‐eroding agendas into the political mainstream.

We conducted two sets of studies in each country during the second half of 2021. Pilot Studies 1a‐c (1a: Israel, 1b: Germany, 1c: the United States) set out to examine the basic assumption underlying GMM: that the public holds gendered perceptions of democracy‐eroding policy support, and of the image of the parties promoting these policies. Based on the pilot studies, we chose the radical‐right policies used in Studies 2a‐c (2a: Israel, 2b: Germany, 2c: the United States), in which we examined the hypothesized mediation model (GMM; Fig. 1). In Studies 2a‐c, we experimentally manipulated the gender of the politician advocating democracy‐eroding policies (woman/man) and examined the effects of the politician's gender on citizens’ acceptance of the politician, their policy and party they represent, through the attribution of feminine gender stereotypes to the woman/man politician. To conduct a robust test of our hypothesized mediation model, we also considered the attribution of masculine stereotypes as an alternative mediator in the relation between the politician's gender and acceptance of the politician, policy and party. Previous literature on gender stereotypes suggests that professional women are generally perceived as more masculine than women in ‘traditional’ roles (Fiske, Reference Fiske2010). Furthermore, political office is perceived as a predominantly masculine occupation (Huddy & Terkildsen, Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; Rosenwasser & Dean, Reference Rosenwasser and Dean1989). To ensure that it is the attribution of feminine, but not masculine, stereotypes that drive the hypothesized effect, Studies 2a‐c measured the attribution of stereotypes associated with both masculinity and femininity. Finally, we examined whether participants’ own gender or political orientation qualified the hypothesized effects. Consistent with the literature reviewed above, we expected the hypothesized mainstreaming effect to be particularly impactful among women and left‐wing citizens because these may be more cognizant of the masculine image of parties promoting anti‐democratic policies and more deterred by it.

All studies were conducted online using samples that were nationally representative of age, gender, political orientation and geographic region. Participants in these studies were recruited by local professional survey companies (Midgam panel and ipanel in Israel, Respondi in Germany and Dynata in the United States), who provided participants with an anonymized link to the survey. Participants participated in our study in exchange for monetary compensation, which was determined by each company based on the length of the survey. All surveys were administered using the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics.com), such that the three studies within each set of studies (Studies 1a‐c and Studies 2a‐c) were identical in length, text layout and design. Participants spent on average 15 minutes completing Studies 1a‐c, and 9 minutes completing Studies 2a‐c. All datasets and syntax used for analyses in all studies are available at https://osf.io/apk6r/?view_only=a58dda0362b645d786c49cde5262f77c.

Pilot studies 1a‐c

In these studies, Israelis (Study 1a), Germans (Study 1b), and Americans from the United States (Study 1c) read several short paragraphs, each describing a radical‐right policy that was recently proposed by local politicians or was broadly discussed in the local media. The policies were chosen with the help of local expertsFootnote 2, such that they promote authoritarian agendas which seek to challenge democratic institutions through executive aggrandizement or civil rights eroding policies, often with a nativist/anti minority flavour.Footnote 3 None of these policies address explicit women's issues (for example reproductive rights, gender, women's equality). In addition, none of these policies pertain directly to areas that are considered ‘feminine’ issues in the literature, such as increased social spending on welfare, education, health, etc. (Lizotte, Reference Lizotte2020). Rather, they all fall under ‘masculine’ categories such as security, terrorism, immigration, race and executive power (Eichenberg, Reference Eichenberg2019). Selecting these policies allowed us to meet the central goal of the pilot studies: to examine the extent to which radical‐right policy support and the image of the parties promoting such policies are viewed through a gendered lens by the Israeli, German and United States publics. Based on the literature reviewed above, we hypothesized that when presented with anti‐democratic policies:

(H1a) The more participants rate the policy as right‐wing/conservative (vs. left‐wing/liberal), the more they perceive it as supported primarily by men (vs. primarily by women).

(H1b) The more participants rate the policy as right‐wing/conservative (vs. left‐wing/liberal), the more they perceive the party promoting it as masculine (vs. feminine).

The second goal of the pilot studies was to choose the policies that were clearly perceived by the public as right‐wing/conservative, for use in Studies 2a‐c to test the GMM of democratic backsliding.

Samples

Study 1a was based on a sample of 501 Jewish‐Israelis (50.8 per cent women, 48.6 per cent men and 0.6 per cent ‘other;’ Mage [SD] = 42.70[15.83]; Mideology [SD] = 3.29[1.39] on a scale ranging from 1[right] to 7[left]). Study 1b was based on a sample of 992 Germans (51 per cent women, 49 per cent men; Mage [SD] = 43.81[14.31]; Mideology [SD] = 4.22[1.07] on a scale ranging from 1[right] to 7[left]). Study 1c was based on a sample of 1,009 US Americans (48.6 per cent women, 51.0 per cent men, 0.4 per cent ‘other’; Mage [SD] = 44.26[17.41]; Mideology [SD] = 3.68[1.90] on a scale ranging from 1[conservative] to 7[liberal]).

Procedure and measures

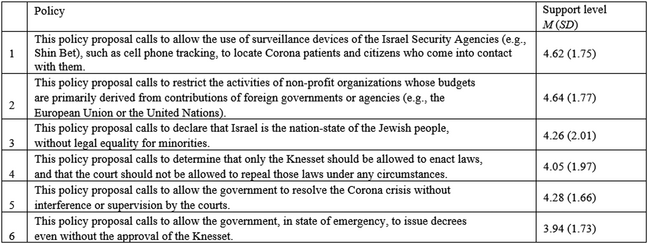

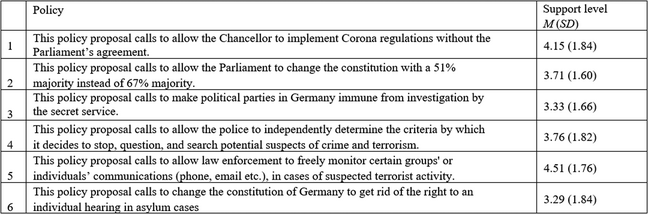

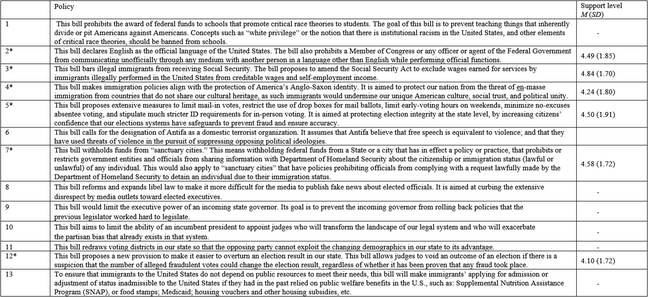

Participants first completed a demographic survey, including items assessing their gender (1 = man, 2 = woman, 3 = other), and their political ideology (1 = extreme right/conservative, 7 = extreme left/liberal). They were then told the following: ‘You will now be presented with a list of bills proposing policies in various domains. You will be asked to answer several questions relating to each of these policies’. Participants were then presented with 6–13 radical‐right policy proposals, in random order. Figures 2–4 list the policies for each country, which vary in number and substance, reflecting the most salient issues in each country at the time. Regarding each policy, participants were asked to answer the following items: (a) ‘To what extent do you think this policy reflects a right‐wing/conservative (7) vs. a left‐wing/liberal (1) worldview?’; (b) ‘Do you think this policy is mostly supported by men or by women? (1 = mostly by women, 4 = men and women equally, 7 = mostly by men)’; and (c) ‘To what extent would you define a party that promotes such a policy as ‘feminine’ (1) versus ‘masculine’ (7)?’.

Figure 2. Policies presented in Israel (Studies 1a&2a), and mean levels of support for each policy (Study 2a).

Figure 3. Policies presented in Germany (Studies 1b&2b), and mean levels of support for each policy (Study 2b).

Figure 4. Policies presented in the US (Studies 1c&2c), and mean levels of support for each policy (Study 2c).

Note. Policies used in Study 2c are marked with an Asterix (*), the rest were only presented in Study 1c.

Results and siscussion

To test hypotheses H1a and H1b, we examined the zero‐order correlations between the key variables in each study, for each policy separately (means, standard deviations, and zero‐order correlations are presented in Tables A1‐3 in the Supporting Information). Consistent with H1a, the more the policies were perceived as conservative/right‐wing, the more they were perceived as supported primarily by men rather than women (Study 1a: 0.21 ≤ r ≤ 0.42, ps < 0.001; Study 1b: 0.24 ≤ r ≤ 0.39, ps < 0.001; Study 1c: 0.27 ≤ r ≤ 0.40, ps < 0.001). Consistent with H1b, the more the policies were perceived as conservative/right‐wing, the more the parties promoting them were perceived as masculine rather than feminine (Study 1a: 0.21 ≤ r ≤ 0.43, ps < 0.001; Study 1b: 0.30 ≤ r ≤ 0.40, ps < 0.001; Study 1c: 0.31 ≤ r ≤ 0.41, ps < 0.001). All correlations remained significant when controlling for demographics (age, gender, religiosity,Footnote 4 income, education and political orientation; see Supporting Information, Tables A4‐6). These findings suggest that the more the policies were perceived to be conservative/right‐wing, the more they and the parties that espoused them were attributed a masculine rather than feminine image.

Because Studies 2a‐2c aimed to examine the effect of the politician's gender on the acceptance of the politician, policy and party by the public, we intended to use only those pilot‐tested policies that were clearly perceived as conservative/right‐wing (rather than centrist or liberal/left‐wing) by participants in Studies 1a‐c. To identify the policies that met this criterion, we conducted a series of one‐sample t‐tests in which we examined whether participants’ ratings of the ideological positioning of each policy significantly differed from ‘4’ (representing the midpoint on a 1 [extreme left/liberal] to 7 [extreme right/conservative] scale). Full results are shown in Tables A7‐9 in the Supporting Information. In Studies 1a and 1b, the ideological positioning ratings of all policies were significantly higher than 4 (Study 1a: Ms ≥ 4.66, ps < 0.001; Study 1a: Ms ≥ 4.39, ps < 0.001), indicating that they were all perceived as right‐wing. Therefore, all six policies in each of these studies were chosen to be used in Studies 2a‐2b. In Study 1c, 9 of 13 policies were rated as conservative (significantly higher than 4; Ms ≥ 4.40, ps < 0.001). Of the four remaining policies, three were considered neither conservative nor liberal (i.e., not significantly different from 4), and one was considered, on average, liberal (M = 0.81, p < 0.001). Based on these results, and to ensure consistency across the experimental studies, we chose the 3 authoritarian policies and 3 civil‐rights eroding policies that were perceived as most conservative for Study 2c (see Tables A7‐9 in the Supporting Information). Policies chosen to be used in Study 2c are marked with an asterisk in Figure 4.

Studies 2a‐c

Studies 2a‐c examined the GMM (Figure 1) in Israel, Germany and the United States. We investigated whether public acceptance and legitimacy of a radical‐right politician, the policy, and the political party change as a function of the politician's gender. Participants in all studies were randomly assigned to read a fictitious Facebook/Twitter post supposedly written by either a woman or a manFootnote 5 politician, advocating one of six possible democracy‐eroding policies (chosen based on the results of our Pilot Studies 1a‐c)Footnote 6. Although the politician's gender was explicitly referred to (e.g., congressman/congresswoman), their name and photo were anonymized, and their party was not mentioned.

Consistent with the GMM, we hypothesized that (H2a) respondents report higher acceptance of the radical‐right politician, her policy, and her party when the politician is a woman rather than a man. We further hypothesized that (H2b) the effect of the politician's gender on acceptance of the politician, policy and party is mediated by the attribution of feminine and not masculine stereotypes to the politician. Specifically, we hypothesized that the radical‐right woman politician is perceived as more feminine than the radical‐right man politician, and that the attribution of feminine stereotypes in turn increases acceptance of the woman (vs. man) politician, policy and party. Because we manipulated the effect of the politician's gender on acceptance of policies associated with the radical‐right, we used the participants’ own gender and political orientation as potential moderators of the hypothesized effects. Based on previous literature (see Ben Shitrit et al., Reference Ben Shitrit, Elad‐Strenger and Hirsch‐Hoefler2021), we expected the gender mainstreaming effect to influence particularly leftists and women participants.

Samples

We conducted a priori power analyses using G*Power (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009) for the sample size needed to detect a small effect (f = 0.10) in an ANOVA based on standard alpha (0.05) and 90 per cent power.Footnote 7 The analysis yielded an estimated sample size of 2,063 participants for each study. To account for potential dropouts and for the exclusion of participants based on a priori criteria (participants aged below 18 years or those who did not identify themselves either as a man or a woman),Footnote 8 we aimed to recruit 2,400 participants for each study.

The original sample used in Study 2a (Israel) included 2,404 Jewish‐Israelis. After excluding seven participants who were younger than 18 (no participants identified as ‘other’ on the gender item), our final sample included 2,397 participants (51 per cent women and 49 per cent men; age 18–71; Mage[SD] = 40.62[14.60]; Mideology[SD] = 3.21[1.28] on a scale ranging from 1 [right] to 7 [left]). The original sample used in Study 2b (Germany) included 2,419 Germans. After excluding three participants who were younger than 18 and six participants who identified as ‘other’ on the gender item, our final sample included 2,410 participants (51 per cent women and 49 per cent men; age 18–90; Mage[SD] = 44.19[14.40]; Mideology[SD] = 4.21[1.08] on a scale ranging from 1 [right] to 7 [left]). The original sample used in Study 2c (US) included 2,410 Americans from the United States. After excluding five participants who were younger than 18 and nine participants who identified as ‘other’ on the gender item, our final sample included 2,396 participants (50 per cent women and 50 per cent men; age 18–93; Mage[SD] = 43.94[16.23]; Mideology[SD] = 4.12[1.84] on a scale ranging from 1 [conservative] to 7 [liberal]).

Procedure and measures

After completing a demographic questionnaire that included items assessing gender (1 = man, 2 = woman, 3 = other) and political orientation (1 = right/conservative, 7 = left/liberal), participants were randomly assigned to read a fictitious Facebook (Israel and the United States)/Twitter (Germany) post by an anonymous local politician advocating one of the six possible radical‐right policies (Figures 2–4 present the lists of policies, mean levels of support for each policy in Studies 2a‐c; see Supporting Information p. 12 for sample posts). In all three studies, participants were informed that the post was written by a local politician, which was presented as either a man or a woman (in the United States, a congressman/congresswoman), while concealing the candidate's name, profile picture and party affiliation to avoid any confounding information (full wording of instructions to participants is presented in the Supporting Information). All subsequent questions relating to the politician were framed in gender‐appropriate terms, to further strengthen the gender manipulation.Footnote 9

After reading the post, participants were asked to ‘rate the extent to which you would attribute the following characteristics to the politician’, and then presented with eight traits that are considered typically feminine or masculine (see Cuddy et al., Reference Cuddy, Fiske and Glick2008; Huddy & Terkildsen, Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993): four representing feminine stereotypes (likable, moral, trustworthy, sensitive; Study 2a: α = 0.88; Study 2b: α = 0.92; Study 2c: α = 0.95), and five representing masculine stereotypes (harsh, strong, high abilities, high self‐esteem, leader; Study 2a: α = 0.73; Study 2b: α = 0.66; Study 2c: α = 0.80). Following Ben Shitrit and colleagues (Reference Ben Shitrit, Elad‐Strenger and Hirsch‐Hoefler2021), items were written in the form of 8‐point scale bipolar adjectives (1 = weak, 8 = strong; see Supporting Information for exact wording of the traits) and were administered in random order. Among these traits, we embedded a manipulation check item, in which participants were asked to rate the extent to which they think the politician is ‘female’ (8) versus ‘male’ (1).

Finally, participants rated their acceptance of the politician, policy and party based on 6–9 statementsFootnote 10 (see Supporting Information p. 13 for a full list of statements, e.g., ‘I support the policy promoted by this politician,’ ‘I think politicians like this politician threaten the future of the [country]’ reverse coded). Statements were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 8 (to a great extent). The scales demonstrated high internal consistency in all countries (Study 2a: α = 0.94, Study 2b: α = 0.94, Study 2c: α = 0.83). At the end of the survey, participants read a debriefing form explaining the goals and rationale of the study, the nature of the manipulation and the importance of using this type of manipulation in this type of study. The form clarified that the posts used for the manipulation were written especially for these studies.

Results and discussion

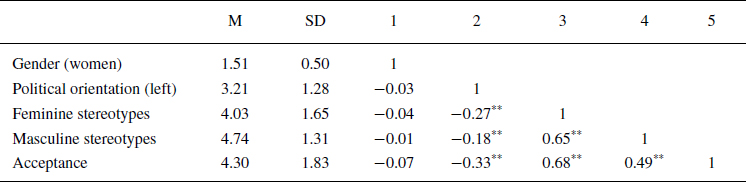

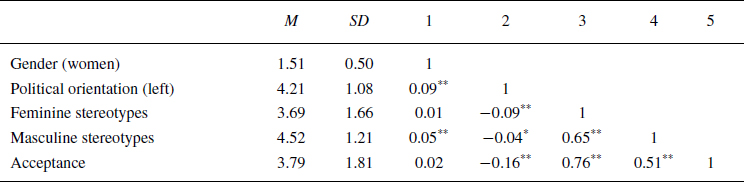

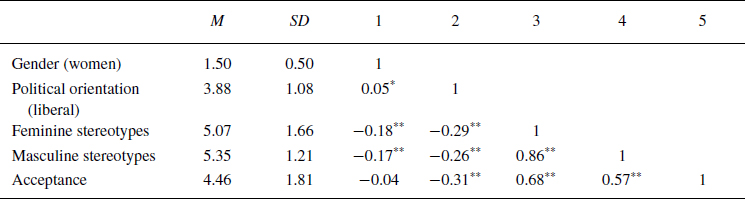

Tables 1–3 show the means, standard deviations and correlations between the main variables assessed in Studies 2a‐c. In all studies, participants’ left‐wing political orientation was negatively associated with acceptance of the radical‐right politician, policy and party. Feminine and masculine stereotypes were positively correlated, and both were positively correlated with acceptance across experimental conditions.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations between the variables of Study 2a (Israel), across experimental conditions

Table 2. Means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations between the variables of Study 2b (Germany), across experimental conditions

Table 3. Means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations between the variables of Study 2c (United States), across experimental conditions

Manipulation check

We performed an ANOVA for each study, with the politician's gender as the predictor, policy (6), participants’ gender (woman/man) and participants’ political orientation (right‐conservative/left‐liberal, median‐split) as moderators, and the extent to which participants saw the politician as female versus male as the dependent variable.

In Study 2a (Israel), the analysis revealed a main effect for the politician's gender (F(2,2325) = 68.61, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06), which was not qualified by participants’ gender, political orientation or policy. All participants rated the woman politician as more female (M[SD] = 4.64[0.06]) than the man politician (M[SD] = 3.64[0.06], p < 0.001). Similarly, in Study 2b (Germany), the analysis revealed a main effect for the politician's gender (F(2,2338) = 132.83, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10), which was not qualified by participants’ gender, political orientation or policy. All participants rated the woman politician as more female (M[SD] = 4.97[0.08]) than the man politician (M[SD] = 3.24[0.08], p < 0.001).

In Study 2c (United States), the analysis revealed a main effect for the politician's gender (F(2,2324) = 26.68, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02), which was qualified by a significant politician's gender × participants’ gender interaction (F(2,2324) = 4.02, p = 0.018, ηp2 = 0.003). Both men and women participants rated the woman politician as more female (women: M[SD] = 0.17[0.10], men: M[SD] = 0.12[0.11]) than the man politician (women: M[SD] = 4.14[0.10], p < 0.001; men: M[SD] = 4.61[0.11], p = 0.001).

These findings confirm that participants in all studies were cognizant of the politician's gender and perceived the woman politician as more female than the man politician.

The effects of the politician's gender on acceptance of the politician, policy, and party (H2a)

To examine H2a, we performed an ANOVA for each study, with the politician's gender as the predictor, policy (6), participants’ gender (woman/man) and participants’ political orientation (right/left, median‐split) as moderators, and acceptance of the politician, policy and party as the dependent variable.

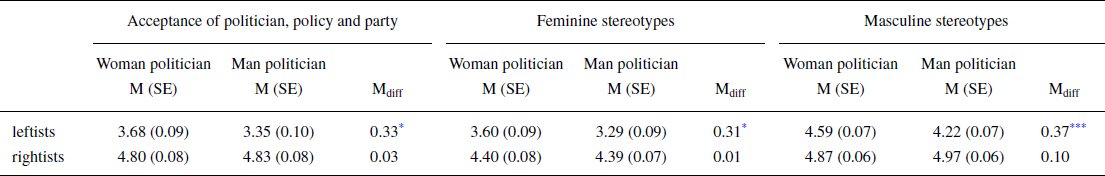

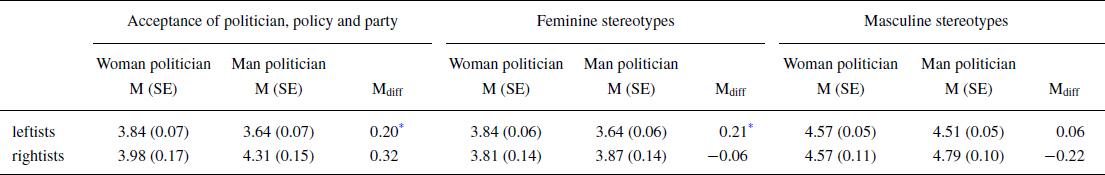

In Studies 2a (Israel) and 2b (Germany), the analyses revealed a significant politician's gender × participants’ political orientation interaction (F(2,2325) = 3.81, p = 0.022, ηp2 = 0.003; and F(2,2338) = 3.06, p = 0.047. ηp2 = 0.003, respectively), which was not moderated by policy (F(10,2325) = 0.27, p = 0.987. ηp2 = 0.001; and F(10,2338) = 0.72, p = 0.702. ηp2 = 0.003, respectively)Footnote 11. Means and standard deviations for these analyses are presented in Tables 4 (Israel) and 5 (Germany). As shown in Tables 4–5, Israeli and German leftists accepted the politician, policy and party more when the politician was a woman than when he was a man (p = 0.014 and p = 0.042, respectively). Israeli and German rightists’ acceptance of the politician, policy and party was not significantly affected by the politician's gender.

Table 4. Means and standard deviations for acceptance (dependent variable) and attribution of feminine and masculine stereotypes (mediators) as a function of a participant's political orientation (left/right) and the politician's gender (woman/man), for study 2a (Israel)

Note. Mdiff = Mean difference; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (two‐tailed significance).

Table 5. Means and standard deviations for acceptance (dependent variable) and attribution of feminine and masculine stereotypes (mediators) as a function of a participant's political orientation (left/right) and the politician's gender (woman/man), for study 2b (Germany)

Note. Mdiff = Mean difference; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 (two‐tailed significance).

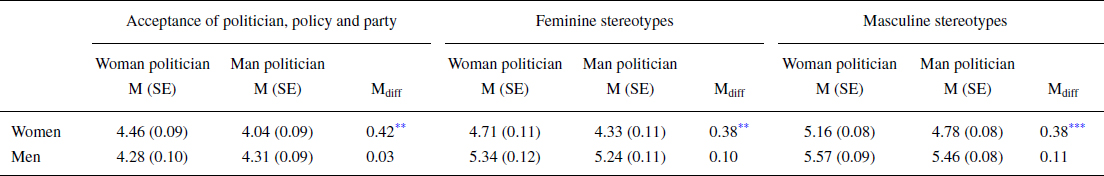

In Study 2c (United States), the analysis did not reveal a significant politician's gender × participants’ political orientation interaction (F(2,2324) = 0.31, p = 0.736. ηp2 < 0.001), but rather a significant politician's gender × participants’ gender interaction (F(2,2324) = 3.26, p = 0.038. ηp2 = 0.003). This interaction was also not moderated by policy (F(10,2324) = 1.64, p = 0.090. ηp2 = 0.007)Footnote 12. Means and standard deviations for this analysis are presented in Table 6. As shown in Table 6, US women accepted the politician, policy and party more when the politician was a woman than when he was a man (p = 0.001), whereas US men's acceptance of the politician, policy or party was not significantly affected by the politician's gender.

Table 6. Means and standard deviations for acceptance (dependent variable) and attribution of feminine and masculine stereotypes (mediators) as a function of a participant's gender (woman/man) and the politician's gender (woman/man), for Study 2c (US)

Note. Mdiff = Mean difference; ***p < .001, ** p <.01, *p < .05 (two‐tailed significance).

In sum, consistent with H2a, acceptance of a radical‐right politician, her policies and her party was higher when she was a woman than when he was a man, regardless of the type of policy. This finding, however, was qualified by participants’ demographics: in Studies 2a‐b (Israel and Germany), the gender manipulation affected primarily leftist participants, and in Study 2c (US) it affected primarily women participants.

The mediating role of gender stereotypes (H2b)

Having established the effect of the politician's gender on acceptance of the politician, the policy and the party by Jewish‐Israeli and German leftists (Studies 2a‐b), and by US American women (Study 2c), we proceeded to examine whether this effect is mediated by gender stereotypes (feminine or masculine). As a first step in testing H2b, we conducted a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) in each study, with the politician's gender as the predictor, policy (6), participants’ gender (woman/man) and participants’ political orientation (right‐conservative/left‐liberal, median split) as moderators, and the attribution of gender stereotypes (feminine and masculine) as dependent variables.

In Study 2a (Israel), the analysis revealed a significant multivariate effect of the politician's gender × participants’ political orientation interaction on the attribution of feminine and masculine gender stereotypes (F(4,4650) = 4.11, p = 0.003. ηp2 = 0.004), which was not moderated by policy (F(20,4650) = 1.09, p = 0.355. ηp2 = 0.005). Means and standard deviations for this analysis are presented in Table 4. As shown in Table 4, Jewish‐Israeli leftists attributed more feminine stereotypes to the woman than to the man (p = 0.012) and more masculine stereotypes to the woman politician than to the man politician (p < 0.001). Rightists did not differ in their attribution of feminine or masculine stereotypes to the woman compared to the man.

In Study 2b (Germany), the analysis revealed a significant multivariate effect of the politician's gender × participants’ political orientation × participants’ gender interaction on the attribution of feminine and masculine gender stereotypes (F(4,4676) = 2.51, p = 0.040. ηp2 = 0.002), which was not moderated by policy (F(20,4676) = 1.29, p = 0.174. ηp2 = 0.005). For German leftists, similarly to Jewish‐Israeli leftists, the politician's gender had a significant multivariate effect on the attribution of gender stereotypes (F(4,3832) = 0.72, p = 0.005. ηp2 = 0.004), which was not moderated by the participants’ gender (F(4,3832) = 1.21, p = 0.302. ηp2 = 0.001). Means and standard deviations for this analysis are presented in Table 5. As shown in Table 5, German leftists attributed more feminine stereotypes to the woman politician than to the man (p = 0.021) but did not differ in their attribution of masculine stereotypes to the woman and to the man politician (p = 0.390). For rightists, there were no significant multivariate effects for either the politician's gender (F(4,844) = 0.66, p = 0.616. ηp2 = 0.003) or the politician's gender × participants’ gender interaction (F(4,844) = 1.51, p = 0.198. ηp2 = 0.007).

In Study 2c (US), the analysis revealed a significant multivariate effect of the politician's gender on the attribution of gender stereotypes (F(4,4648) = 2.83, p = 0.023. ηp2 = 0.002), which was not moderated by participants’ political orientation (F(4,4648) = 0.17, p = 0.956. ηp2 < 0.001), by the participants’ gender (F(4,4648) = 0.71, p = 0.583. ηp2 = 0.001), or by policy (F(20,2324) = 0.71, p = 0.820, ηp2 = 0.003). Means and standard deviations for this analysis are presented in Table 6. As shown in Table 6, participants (regardless of their gender or political orientation) attributed more feminine stereotypes to the woman than to the man politician (p = 0.027), and more masculine stereotypes to the woman than to the man politician (p = 0.003).

Notwithstanding these country differences, our findings suggest that in all three countries, those segments of society whose acceptance of the radical‐right policy, politician and party was higher when the politician was a woman rather than a man (leftists in Israel and Germany, women in the United States), also attributed stronger feminine stereotypes to the woman than to the man. Because leftists in Israel and women in the United States also attributed more masculine stereotypes to the woman than to the man politician, we examined both types of gender stereotypes as alternative mediators in our hypothesized model.

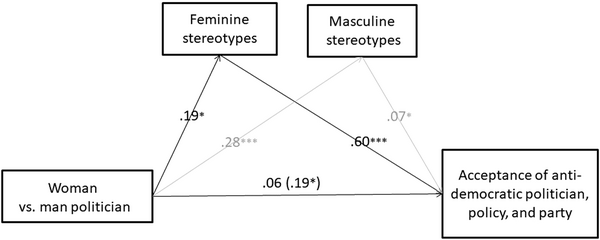

To examine whether the effect of the politician's gender on acceptance of the politician, policy and party is mediated by feminine (or masculine) gender stereotypes, we conducted moderated mediation analyses using Hayes’ (Reference Hayes2017) PROCESS Macro (Model 59; see Figure 5 for a conceptual diagram of the model), with the bootstrapping command set to 5,000 iterations. In Studies 2a‐b, the politician's gender was set as a predictor,Footnote 13 participants’ political orientation as a moderator (left/right), feminine and masculine stereotypes as simultaneous (competing) mediators, acceptance of the politician, policy and party as the dependent variable and participants’ gender (woman/man) and policy (dummy‐coded) as covariates. In Study 2c, the politician's gender was set as a predictor, participants’ gender as a moderator (woman/man), feminine and masculine stereotypes as simultaneous (competing) mediators, acceptance of the politician, policy and party as the dependent variable and participants’ political orientation (left/right) and policy (dummy‐coded) as covariates.

Figure 5. Conceptual diagram of moderated mediation model (Studies 2a‐c).

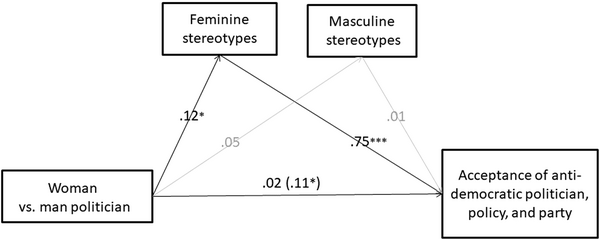

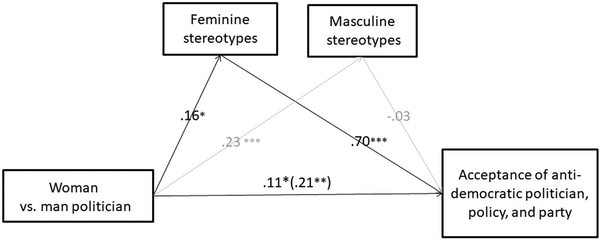

In Studies 2a and 2b, the indirect effect of the politician's gender (woman vs. man) on acceptance of the politician, policy and party through the attribution of feminine stereotypes was significant among leftists (2a: effect = 0.19, SE = 0.08, 95 per cent CI [0.04, 0.34]; 2b: effect = −0.16, SE = 0.07, 95 per cent CI [−0.30, −0.02]) but not among rightists (2a: effect = 0.01, SE = 0.07, 95 per cent CI [−0.13, 0.14]; 2b: effect = 0.08, SE = 0.16, 95 per cent CI [−0.25, 0.40]). The indirect effect of the politician's gender (woman vs. man) on acceptance of the politician, policy and party through the attribution of masculine stereotypes was not significant either for leftists (2a: effect = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95 per cent CI [−0.001, 0.08]; 2b: effect = 0.001, SE = 0.003, 95 per cent CI [−0.004, 0.01]) or for rightists (2a: effect = −0.02, SE = 0.01, 95 per cent CI [−0.05, 0.01]; 2b: effect = 0.01, SE = 0.02, 95 per cent CI [−0.02, 0.06]). These findings support H2b (standardized coefficients of the mediation model for Jewish‐Israeli leftists are presented in Figure 6 and for German leftists are presented in Figure 7).

Figure 6. The role of feminine and masculine stereotypes in mediating the relations between the politician's gender (man/woman) and acceptance of the politician, party, and policy, among Jewish‐Israeli leftists (Study 2a).

Note. This figure presents standardized coefficients, which were obtained using Model 4 of the PROCESS Macro. Non‐significant indirect paths are marked in grey (although the path leading from masculine stereopyes to acceptance were significant, the indirect path was nonsignificant). *p < 0.05, *p < 0.01, *p < 0.001

Figure 7. The role of feminine and masculine stereotypes in mediating the relations between the politician's gender (man/woman) and acceptance of the politician, party, and policy, by German leftists (Study 2b).

Note. This figure presents standardized coefficients, which were obtained using Model 4 of the PROCESS Macro. Non‐significant indirect paths are marked in grey. *p < 0.05, *p < 0.01, *p < 0.001

In Study 2c, the indirect effect of the politician's gender (woman vs. man) on acceptance of the politician, policy and party through the attribution of feminine stereotypes was significant for women (effect = 0.22, SE = 0.09, 95 per cent CI [0.04, 0.40]) but not for men (effect = 0.07, SE = 0.08, 95 per cent CI [−0.09, 0.24]). The indirect effect of the politician's gender (woman vs. man) on acceptance of the politician, policy and party through the attribution of masculine stereotypes was not significant either for women (effect = −0.02, SE = 0.02, 95 per cent CI [−0.06, 0.02]) or for men (effect = −0.003, SE = 0.01, 95 per cent CI [−0.02, 0.01]). These findings also support H2b (standardized coefficients of the mediation model for US women are presented in Figure 8).

Figure 8. The role of feminine and masculine stereotypes in mediating the relations between the politician's gender (man/woman) and acceptance of the politician, party, and policy, by US women (Study 2c).

Note. This figure presents standardized coefficients, which were obtained using Model 4 of the PROCESS Macro. Non‐significant indirect paths are marked in grey. *p < 0.05, *p < 0.01, *p < 0.001

To conclude, our findings provide support for H2b: in all countries, the effect of a politician's gender on acceptance of the radical‐right politician, policy and party was mediated by the attribution of feminine but not of masculine gender stereotypes. Specifically, Jewish‐Israeli and German leftists, and US women, attributed more feminine stereotypes to the radical‐right woman politician than to the radical‐right man politician, which in turn increased their acceptance of the politician, policy and party. Jewish‐Israeli leftists and US women also attributed more masculine stereotypes to the radical‐right woman politician compared to the man politician, consistent with previous literature of the attribution of stereotypes to professional women (Fiske, Reference Fiske2010). As expected, however, the attribution of masculine stereotypes did not increase acceptance of the politician, policy and party because masculine stereotypes do not counteract or soften the masculine image of radical‐right policies and parties.

General discussion

Studying women's visibility and gender stereotypes as crucial factors in the mainstreaming of democratic backsliding is a unique approach shedding light on largely neglected but decisively important aspects of the effects of descriptive representation. This research offers an in‐depth understanding of some of the mechanisms that help anti‐democratic agendas to move from the margins to the mainstream of society. This study enriches theory on the gendered image of the parties promoting these agendas and has important implications for both policy and political actors who seek to address global patterns of democratic backsliding. The research examined the GMM, according to which the visibility of women politicians as representatives of radical‐right agendas and the femininity attributed to them blunts the masculine image of these agendas and the parties promoting them, making these politicians, their policies and parties more acceptable. Our study is the first to provide cross‐country systematic experimental support for this hypothesis, covering a range of democracy‐eroding policies in three countries: Israel, Germany and the United States.

The pilot Studies 1a‐c show that in all three countries, participants associated democracy‐eroding radical‐right policies with masculinity (versus femininity), and support for democracy‐eroding policies with men (versus women). Studies 2a‐c demonstrate that in all countries, participants were more likely to accept a radical‐right politician, her anti‐democratic policies and her political party, as legitimate, if that politician is a woman rather than a man, although the anti‐democratic policies promoted by the man and the woman were identical. Our findings also suggest that participants tended to ascribe stronger feminine stereotypes to the radical‐right woman politician than to the man, and that this attribution of feminine stereotypes was what mediated the effect of a politician's gender on acceptance of her policies and her party.

Importantly, participants also attributed stronger masculine stereotypes to the woman politician than to the man (in US and Israel). This is consistent with previous research indicating that women politicians often feel compelled to counteract gender stereotypes held by voters by emphasizing their ‘masculine’ qualities (Bauer & Santia, Reference Bauer and Santia2022; Huddy & Terkildsen, Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993). It is interesting to note, however, that in Germany, women politicians were not perceived as more masculine than the men. This could stem from the fact that in recent years, only Germany (but not the United States or Israel) has had a woman as a state leader, which may have blunted the ‘over‐masculine’ image of women politicians in Germany. Although it was the attribution of feminine traits, rather than of masculine traits, that was associated with the observed gender mainstreaming effect, we encourage future studies to further examine cross‐country differences in the attribution of masculine traits to women versus men politicians.

In all three countries, mainstreaming effects were observed among participants who are typically most repelled by the radical‐right and its masculine image: leftists and women. Indeed, being a ‘woman’ and a ‘leftist’ tended to be strongly correlated in our three studies, consistent with previous research showing that women in many countries are more likely than men to support left‐wing parties (Ben Shitrit et al., Reference Ben Shitrit, Elad‐Strenger and Hirsch‐Hoefler2017; Emmenegger & Manow, Reference Emmenegger and Manow2014; Seltzer et al., Reference Seltzer, Newman and Leighton1997). Hence, the observation that susceptibility to the gender mainstreaming effect was more prominent among leftists in Israel and Germany, while in the United States it was mainly noticeable among women, could potentially be attributed to statistical confounds rather than implying a significant variability in susceptible target audiences. Importantly, the cross‐country variation in susceptible target audiences and the fact that this effect was explained by the attribution of feminine stereotypes in all three contexts suggest that gender mainstreaming does not merely reflect a homophily (gender affinity) effect, with women tending to support women in politics more than men (see also Ben Shitrit et al., Reference Ben Shitrit, Elad‐Strenger and Hirsch‐Hoefler2021). Rather, it is the intersection of the stereotypes applied to radical‐right politics that generates this mainstreaming effect and the countervailing gender stereotypes applied to a political actor. Indeed, it is possible that the gender affinity effect, which has found support particularly in the United States (Badas & Stauffer, Reference Badas and Stauffer2019; Brians, Reference Brians2005; Dolan, Reference Dolan2014), may be driven by positive feminine stereotypes held by women about women rather than by mere gender identification. Future research, expanding the examination of this model to additional socio‐political contexts, can shed further light on this cross‐country variation.

While our findings support the role of gender stereotypes, rather than of gender affinity, in underlying the gender mainstreaming effect, an important question remains: Is this effect limited to democracy‐eroding policies, or can it be generalized to any policy? Notably, previous studies indicate that women's equal involvement in political decision making enhances citizens' perceptions of procedural legitimacy, irrespective of the decision itself (Clayton et al., Reference Clayton, O'Brien and Piscopo2019). One could argue that any policy would garner greater acceptance from the public when promoted by women politicians. However, Ben Shitrit and her colleagues (Reference Ben Shitrit, Elad‐Strenger and Hirsch‐Hoefler2021) present initial evidence suggesting that the gender of the political actor does not impact citizens’ support for democracy‐promoting or radical left‐wing agendas. According to the authors, as left‐wing politics are not typically associated with masculine stereotypes (Köttig et al., Reference Köttig, Bitzan and Petö2017), and as women's presence constitutes the norm in left‐wing politics rather than an anomaly (Devroe & Wauters, Reference Devroe and Wauters2018), women actors on the political left do not present a counterstereotype to leftist policies or parties. Nevertheless, more research is needed to systematically explore the applicability of gender mainstreaming effects across a broad spectrum of democracy‐promoting policies and those lacking a gendered image. Additionally, while Studies 1a‐c demonstrate a positive correlation between the perceived ‘right‐wingness’ of a policy and the extent to which it is supported by ‘men’ and promoted by ‘masculine’ parties, future studies are encouraged to examine the generalizability of gender mainstreaming effects in contexts where support for left‐wing agendas is not necessarily attributed to women more than to men or to ‘feminine’ parties.

Relatedly, future studies should further investigate the causal role of gender stereotypes in underpinning the observed mainstreaming effects. Although our studies provide support for the hypothesis that attributing feminine gender stereotypes to the politician, rather than attributing masculine ones, is related to increased support and acceptance of democracy‐eroding policies, our ability to establish their causal role in driving increased support for democracy‐eroding policies and parties is limited, as we did not directly manipulate gender stereotypes (see Pirlott & MacKinnon, Reference Pirlott and MacKinnon2016). Therefore, future studies could examine the effects of manipulated politicians’ gender stereotypes (both masculine and feminine) on policy support, independently of the gender of the politician, and to explore their interactive effects with a manipulated politician's gender.

Finally, this study is only the first step in a new research agenda we put forth for other scholars. Alongside the above suggestions for future research, we also encourage scholars to inquire both experimentally and empirically into the intersections of a politician's gender and various other markers – for instance, ethnicity, class, age, incumbency– as well as contextual differences between countries, that may impact and modify our gender mainstreaming model of democratic backsliding. For example, could the fact that it was left‐leaning respondents in Germany and Israel who were affected by the GMM, but women rather than leftists in the United States, be explained by stronger partisanship in the US context? In a sharply polarized electorate, even pro‐democratically minded voters may act as partisans first and democrats only second (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020). Specifically, studies show a close connection between ideological and affective polarization in the United States. Notably, although Americans’ feelings about their party have changed very little, their feelings about the opposing party have become much more negative (Webster & Abramowitz, Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017). We believe our study is just a first step in unpacking the possible effects and mechanics of the GMM across the globe.

To summarize, our findings contribute to the understanding of processes of democratic backsliding and of the interaction of gender and radical‐right politics, by demonstrating that the gender of democratic backsliders affects the public acceptance of their agendas, even if the agendas themselves remain the same and even if their agendas are unrelated to gender issues. These findings suggest that a gendered lens can clarify some of the causes of the current and possibly future ascendance of democratic backsliders and the mainstreaming of their democracy‐eroding tendencies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to Mabelle Kretchner and David Azory for excellent research assistance for this project, and to Gabriel Lanyi for his helpful comments and suggestions.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

All datasets and syntax used for analyses in all studies are available at https://osf.io/apk6r/?view_only=a58dda0362b645d786c49cde5262f77c.

Ethics approval statement

All studies received IRB approval.

Funding Statement

This research was made possible, in part, by grants from the Israel Science Foundation (2623/21) and the program on democratic resilience and development (PDRD) at the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy and Strategy, Reichman University (IDC) Herzliya.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix