Introduction

In almost all West European countries, no party wins an absolute majority in parliament. This makes coalition building, whether in the form of majority coalitions or minority governments that seek ad hoc coalitions, necessary for governing and thus a key element of politics. However, coalition building involves a dilemma for political parties: Do they compromise in order to enter coalitions, or do they stay true to their ideological positions? Crucially, parties need their electorates to support the way in which they handle this dilemma. If voters find that political parties are too compromising, they are likely to punish them at the next election. This prospect may deter political parties from entering coalitions. Coalition building thus depends on citizens having a ‘compromising mindset’ (Gutmann & Thomson, Reference Gutmann and Thompson2010), meaning that they accept that parties need to compromise and that this entails giving up some of their preferred policy positions. Without that, European democracies ultimately risk not being governed at all.

From this perspective, it is surprising how little is known about how citizens view compromise in politics. Existing studies argue that political parties are likely to be punished for compromising. Fortunato (Reference Fortunato2021, p. 45) thus states that citizens ‘equate compromise with representational failure’. In light of the increased fragmentation of many West European party systems, which exacerbates the need for compromise, this is a worrying finding. However, do citizens in Western Europe really see so little value in compromising?

In this study, we argue that citizens in West European countries – where coalition politics is often the order of the day – have developed a compromising mindset, in the sense that they expect political parties to be willing to compromise. Such a mindset does not imply unconditional support for compromise. Citizens might punish parties for compromising in specific cases. However, it does imply that citizens will not automatically see compromise as a failure. They understand that it is essential for democratic governance and actually expect political parties to compromise – and sometimes punish them if they do not.

We evaluate these theoretical claims using two different analyses: First, we compare observational data from the Austrian National Election Survey (AUTNES) to our own original survey in Denmark. These two surveys allow us to study how citizens view compromising on a comparative perspective and across different groups of voters. Second, we present results from a conjoint experiment included in the Danish survey evaluating the effect of willingness to compromise on vote choice. The conjoint experiment addresses the worry that supporting compromise in surveys is costless and driven by social desirability bias.

We find that a compromising mindset is widespread among citizens. It also covers citizens at the political extremes, who are most likely to vote for parties with a populist appeal. While they are somewhat less supportive of compromising, even the majority within these groups hold a compromising mindset. The finding of a compromising mindset is also robust to different framings of the question, that is, wording of survey questions, and we also show that it is electorally consequential, that is, citizens with a more compromising mindset are also more likely to support parties that compromise.

Citizens, coalitions and compromise

Existing studies of West European citizens have shown that they take coalition politics into account when voting. This has been found to be the case across a number of West European countries (Gschwend et al., Reference Gschwend, Meffert and Stoetzer2017; Irwin & van Holsteyn, Reference Irwin and Holsteyn2012; Marsh, Reference Marsh2010; Meffert et al., Reference Meffert, Huber, Gschwend and Pappi2011; Sohlberg & Fredén, Reference Sohlberg and Fredén2020). Citizens have coalition preferences (Debus & Müller, Reference Debus and Müller2014; Plescia & Aichholzer, Reference Plescia and Aichholzer2017) and they use coalition participation as an information heuristic (Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013) to extract information about policy positions from coalition behaviour (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Gschwend and Indridason2020; Falcó‐Gimeno & Muñoz, Reference Falcó‐Gimeno and Muñoz2017; Fortunato & Adams, Reference Fortunato and Adams2015; Hjermitslev, Reference Hjermitslev2023; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2017). From this perspective, it is remarkable how little is known about how citizens view the compromising that per definition is involved in coalition building. Do they view coalition building and the compromising involved as the ‘dark side’ of politics, driven by politicians’ wish for power and personal gains, or rather as a necessary democratic process in countries where no party wins an absolute majority in parliament (cf. Bellamy, Reference Bellamy2012)?

The most elaborate attempt at studying how citizens view coalition building and the compromising involved is provided by Fortunato (Reference Fortunato2021), who arrives at a rather pessimistic conclusion. According to Fortunato (Reference Fortunato2021, pp. 40−60), citizens compare the outcome of a coalition compromise to a counterfactual in which their favourite party is able to decide everything itself, and from that perspective compromising will almost by definition lead to disappointed citizens. Citizens equate compromise with representational failure (Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2021, p. 45) and view it as a sign of either incompetence or insincerity on the part of politicians (Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2021, p. 57). The only reason why citizens accept compromise to some extent is that they – like the ever‐disappointed sports fan – continue to hope that it will get better.

Fortunato's view on compromising might appear as an extremely pessimistic view, but it is a logical extension of studies of coalition building based on the spatial tradition that sees party supporters and citizens as ideological purists (e.g. Laver & Schofield, Reference Laver and Schofield1990, pp. 23–25: Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2020). Citizens’ only perspective is whether a compromise is too far away from their ideological ideal point, that is, Fortunato's counterfactual, to be acceptable. The need for compromising, and thus governance, plays no role in how citizens evaluate coalition compromising.

If coalition building and compromise are inherent features of most West European political systems, and if the need for compromise might even be increasing due to fragmented party systems, this sceptical view of compromise leaves limited room to manoeuvre for political parties and thus not much basis for optimism on behalf of West European democracies. This argument squares well with other findings that citizens punish coalition parties that they see as too compromising (Fortunato et al., Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021), especially junior parties in a coalition (Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2020; Hjermitslev, Reference Hjermitslev2020) and that they punish parties for not keeping their electoral pledges (Matthieß, Reference Matthieß2020). From this perspective, there is little evidence that citizens in Western Europe have much of a compromising mindset.

Other studies of coalition politics, however, find evidence that points more in the direction of a compromising mindset. Plescia et al. (Reference Plescia, Ecker and Meyer2022) show that Spanish voters do seem to accept compromising related to government formation. Yet, this support was conditional on the importance of the issue, on party attachment – stronger attachment to the compromising party means less willingness to compromise – and on support for a challenger party. Thus, existing studies of compromising in relation to West European party systems share the starting point that compromising is something citizens might in some cases accept, but not something they want political parties to do if they can avoid it.

However, studies of compromising in the U.S. context, where it is not tied to coalition building among political parties, offer a different perspective. Wolak (Reference Wolak2020) argues that as a result of socialization, Americans view compromise as a democratic norm that political parties should live up to. This norm exists beyond party preferences, that is, when compromising implies not fully realizing one's political preferences. This understanding of compromise is thus more far‐reaching than the acceptance of compromising due to the necessity of coalition building. According to Wolak (Reference Wolak2020), willingness to compromise is a general democratic norm that exists even in cases where a political party can implement its preferences without having to build a coalition, that is, a norm of bipartisanship. While citizens do not strictly prefer compromise in the form of bipartisan policymaking over situations where their own party wins, there is no significant difference in support (Harbridge et al., Reference Harbridge, Malhotra and Harrison2014). Even when a party concedes ‘for free’, there is widespread support for compromise in the American electorate.

The Wolak (Reference Wolak2020) perspective thus raises the question of whether Fortunato's (Reference Fortunato2021) perspective on citizens’ acceptance of compromising is in fact too narrow. If acceptance of compromising simply rested on the naïve optimism of the ever‐disappointed sports fan, as Fortunato argues (Reference Fortunato2021, p. 57), it is hard to see how West European democracies could preserve support from citizens over the course of decades. The Fortunato perspective further leads to a focus on how citizens react to political parties promising one thing before an election and then agreeing to a different thing after the election as part of a compromise. This perspective is clearly relevant but neglects that citizens also want their countries to be governed and for political parties to address policy problems through governance. Willingness to compromise has, for example, been found to be an important component of why British citizens view political parties as competent (Johnson & Kölln, Reference Johnson and Kölln2020).

This is exactly the ‘compromising mindset’ that Gutmann and Thomson (Reference Gutmann and Thompson2010) have argued is necessary for governance of democracies. This mindset, which we argue that citizens in Western Europe do have, does not imply that acceptance of compromising is in any way unconditional, that is, citizens will expect political parties to always be willing to compromise. Yet, it does imply that they understand and value the need to compromise as an important part of what is expected of political parties who govern in democracies (Gutmann & Thomson, Reference Gutmann and Thompson2010). Contrary to the Fortunato perspective, citizens’ default expectation of political parties is not that they should be unwilling to compromise because citizens see this as a betrayal of political principles. Citizens actually expect political parties to be willing to compromise in general. This leads to our first hypothesis:

H1: Citizens expect political parties to be generally willing to compromise.

The literature, however, as presented above, also highlights that this acceptance is not unconditional. Most clear is the finding that it depends on political extremity. Matthieß and Regel (Reference Matthieß, Regel, Kneip, Merkel and Weßels2020) find that German supporters of extreme parties are less supportive of compromising, and, based on Austrian data, Plescia and Eberl (Reference Plescia and Eberl2021) also find that populist attitudes are important for how citizens view coalition formation processes. Thus, we should expect a compromising mindset to be less widespread among voters who are politically extreme either to the left or right. This leads us to our second hypothesis:

H2: Politically extreme citizens are less supportive of compromising than moderate citizens.

Finally, we also expect that citizens’ view of compromising is consequential for which political parties they are willing to support. As Wolak (Reference Wolak2020) points out, compromise in the abstract is often seen as a positive thing, and it is, therefore, likely that some citizens will express support for political parties being willing to compromise while not actually valuing it when deciding which parties to support. Therefore, for citizens who have a compromising mindset, we also expect that the stronger such a mindset is, that is, the more supportive of compromising they are, the more they put emphasis on political parties being willing to compromise when deciding which party to vote for. This leads to our third hypothesis, which can be split into two related sub‐hypotheses:

H3A: Citizens prefer parties that are compromising when deciding which party to support.

H3B: Citizens who are more supportive of compromising put more emphasis on political parties being willing to compromise when deciding which party to support than citizens who express less support.

Data

In the following, we investigate our hypotheses using two data sources, namely the 13th wave of AUTNES (Aichholzer et al., Reference Aichholzer, Partheymüller, Wagner, Kritzinger, Plescia, Eberl, Meyer, Berk, Büttner, Boomgaarden and Müller2020) and a survey conducted in Denmark in 2021. Combining data from Austria and Denmark allows us to investigate how citizens view compromising in two rather different cases of coalition politics in Western Europe, thus assuring us that the existence of a compromising mindset is not related to the particular form of coalition politics that citizens have been exposed to. Coalition politics in Austria has traditionally been dominated by grand majority coalitions between ÖVP and SPÖ. Until an ÖVP/Green coalition was formed in 2020, the only alternative majority coalition was an ÖVP/FPÖ coalition (Müller, Reference Müller, Bergman, Bäck and Hellström2021). Denmark, on the other hand, has until 2022 almost exclusively been governed by minority governments, typically coalitions, but sometimes also single‐party governments that then build majorities on a more ad hoc basis. Governing parties rely on a ‘bloc majority’ that secures the stability of the government, but at the same time they make agreements and thus compromise with a broad range of parties in parliament around specific bills (Christiansen, Reference Christiansen, Bergman, Bäck and Hellström2021).

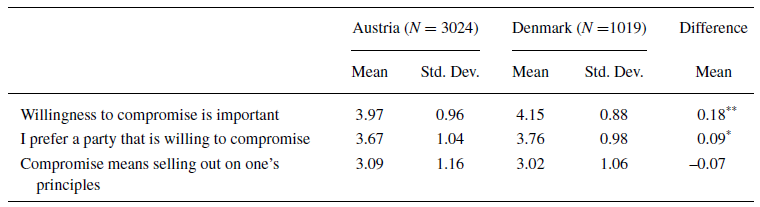

The surveys in both countries included three identical statements on compromising, with which respondents could either agree or disagree: (1) ‘Openness to the views of others and the willingness to compromise are important for politics in our country’, (2) ‘I prefer a party that is willing to compromise to make things happen over a party that always sticks to its principles, no matter what’, and (3) ‘What people call compromise in politics is really just selling out on one's principles’.Footnote 1 These items allow us to evaluate H1.

To evaluate H2, we differentiate between two types of political extremity. We code respondents who self‐place between 0 and 2 on the left‐right scale as ‘left extremists’ and respondents who self‐place between 8 and 10 as ‘right extremists’. As a robustness check, we present the same analyses with unmanipulated ideology and squared ideological distance from the mean in Tables E and F in online Appendix A. Extreme parties further tend to be small, although perhaps less so in Austria and Denmark than other West European countries, and since supporters of small parties might see compromise as inevitable, we also control for the seat share of the party that the respondent supports. This confounder might otherwise cause us to underestimate the true effects of extremity. The variable is based on the so‐called ‘Sunday question’, which asks voters whom they would vote for if elections were held tomorrow. Abstainers and undecided voters are excluded from the analysis.

Finally, the analysis also includes political interest and education levels as control variables. Self‐reported political interest is measured on a four‐point scale from ‘Not at all interested’ to ‘Very interested’. For Denmark, education is measured using six educational categories. The Austrian data, however, has only four educational categories, which are not directly comparable. The specific coding is described in Table B online Appendix A. We present separate analyses for the two countries.

To evaluate H3A and H3B, we make use of a conjoint experiment conducted as part of the Danish survey. The conjoint experiment allows us to investigate the relative importance of support for compromising in comparison with other factors, especially ideology, that matter for which parties citizens support.Footnote 2 Further, the findings of the survey can be combined with answers to the questions on compromising, thus allowing us to investigate observationally whether support for compromise in the abstract also materializes in connection with (hypothetical) vote choice.

The 13th wave of the AUTNES 2017–2022 panel study was fielded on January 10th−24th 2020, while the Danish survey was fielded on October 29th – November 10th 2021. Both surveys have samples that are representative of the general population,Footnote 3 but we also apply survey weights calculated based on key socio‐demographics to ensure that differences in the results are due to genuine differences among the two populations and not a consequence of the survey sampling.Footnote 4 For all three questions, the answers were provided on a five‐point scale from ‘Completely agree’ to ‘Completely disagree’, which was coded such that a high value on all three questions means that the respondent is supportive of compromise.

In sum, our data provide a strong foundation for testing the idea of a ‘compromising mindset’. The comparative survey data are strong in terms of external validity, whereas the conjoint experiment is strong in terms of internal validity.

Do citizens have a compromising mindset?

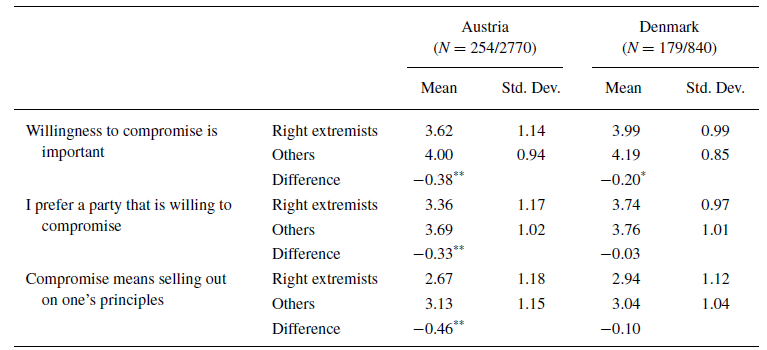

Table 1 shows that both Austrian and Danish voters are predominantly positive towards compromise when presented in the form of the three statements described above. When looking at the first two questions, the average in both countries is close to the value indicating ‘Agree’. In the third item, compromising is presented as a matter of ‘selling out’ one's principles.Footnote 5 Even in this situation when the question is framed as a representational failure, that is, along the lines suggested by Fortunato (Reference Fortunato2021), citizens in Denmark and Austria are not unsupportive of compromise.Footnote 6 Acquiescence bias in the sense that citizens tend to agree more with any statement than disagree is a worry in terms of these two items. Yet, this logic would point in the opposite direction with regard to the third item, which also has the lowest average support for compromising. The first two items might thus overestimate the support for compromising due to acquiescence bias. Still, overall based on the survey questions reported in Table 1, citizens in Denmark and Austria do seem to value compromising and to some extent expect political parties to be willing to compromise. As can be seen from Table 1, Danes in general, seem a bit more positive towards compromising than Austrians, but the difference is minor.Footnote 7

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of compromise items in the AUTNES (2020) and original Danish survey (2021) (1–5 scale).

Note: *p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01, based on the t‐test for difference in means.

For further analysis, we constructed a willingness to compromise index based on respondents’ average scores on the first two questions presented above: higher values thus mean more support for willingness to compromise. The decision to include only the first two is based on a factor analysis reported in Table C in online Appendix A. The third survey item on ‘selling out’ did not load as strongly on the same factor, and there is a considerable share of respondents who support willingness to compromise, but who are nevertheless sceptical of parties’ intentions.Footnote 8

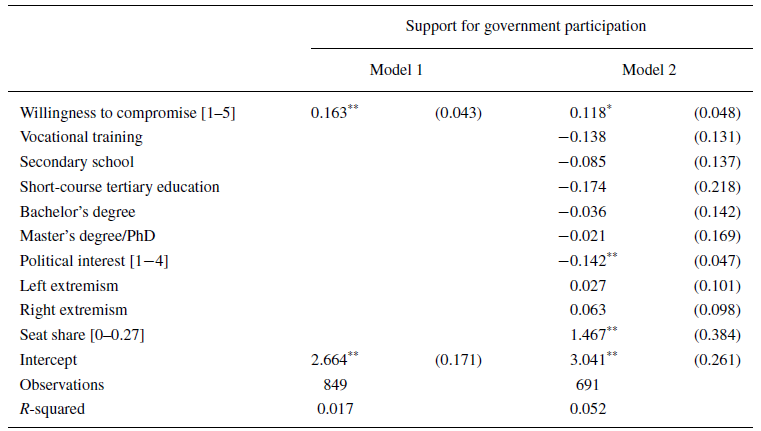

Overall, the findings support the argument that citizens have a compromising mindset, that is, they see compromising as an important trait of the political parties they are willing to support. However, as argued above, this does not mean citizens are always supportive of compromising in all situations. To see how willingness to compromise might affect attitudes towards compromise under specific conditions, we further examine a question in the Danish survey where citizens were asked whether they think parties should be willing to enter into government and, by implication, run the risk of supporting and implementing political decisions they disagree with, or rather stay out in order to avoid supporting such decisions.Footnote 9 Table 2, Model 1 shows that citizens who are more supportive of compromising in general are also more supportive of government participation. Yet the effect is not particularly strong. Thus, the more supportive citizens are of compromising, the more they also indicate support for parties that seek influence; but there is far from a 1:1 relationship between the two. The finding is the same when we introduce the variables discussed above as controls in Model 2.

Table 2. OLS regression results predicting attitudes towards government participation in Denmark 2021.

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

* p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01.

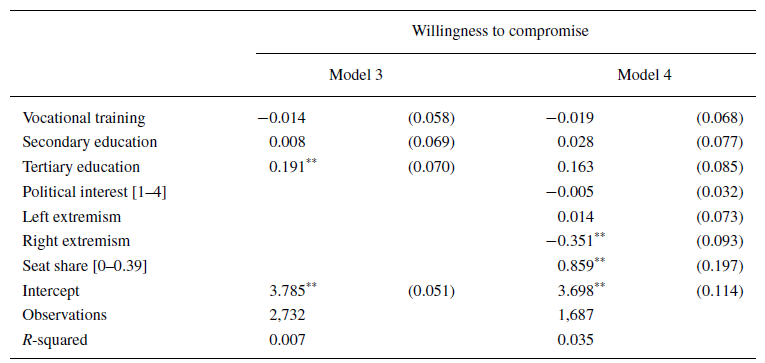

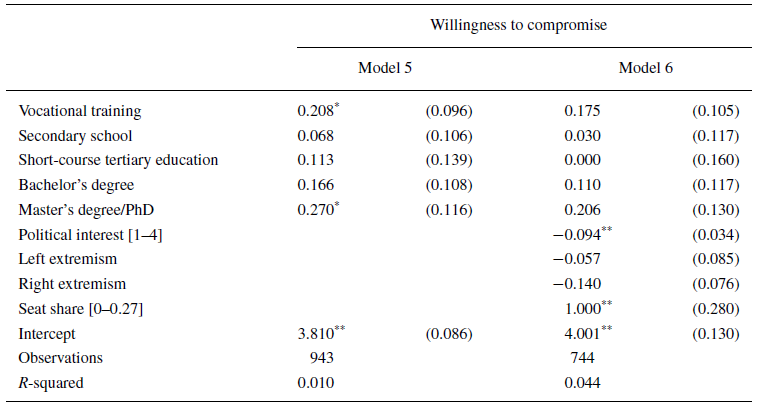

To evaluate H2, we then analyse whether political extremity, as measured above, matters for attitudes towards compromising, that is, the willingness to compromise index when controlling for education, political interest and seat share.

The tables above thus display the results of an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression on the Austrian (Table 3) and the Danish (Table 4) data. We can generally reject H2, which states that politically extreme citizens are less supportive of compromise. For Denmark, there is only a small and insignificant effect of right extremism. This result is very robust to the other operationalizations of extremity shown in Table F of the online Appendix. In Austria, there is a substantial negative effect of being right extremist, but also a general negative effect of being more right‐wing (please refer to Table E in online Appendix A for the results), while there is no effect of left extremism and squared ideological distance from the mean. Thus, only politically extreme citizens on the right in Austria can be considered less supportive of compromise.

Table 3. OLS regression results predicting compromise attitudes in Austria 2020.

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses.

* p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01.

Table 4. OLS regression results predicting compromise attitudes in Denmark 2021.

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

* p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01.

In Denmark, there is a significant negative effect of political interest and a small negative effect of vocational training, but the latter only in the model that includes only educational control variables. In Austria, there is a small positive effect of completing tertiary education but only in the model that includes only educational control variables.Footnote 10 Thus, the more general conclusion is one of widespread support for compromising among both Austrian and Danish citizens. Differences across political interest and educational levels are minor, and it is also worth noting the small R 2 values in Tables 3 and 4, which testify to the weak explanatory power of these variables. In both countries, there is a strong and significant effect of seat share – voters that support larger parties are generally more positive towards compromise.Footnote 11

To further investigate the role of political extremity, Table 5 shows the answer to the three questions about compromising for the right extremists in both countries compared to the rest of the population. In Austria, there is a significant difference between how the right extremists and the rest of the sample answered all of the three compromise questions. Only for the question concerning preferences for compromising parties is there a significant difference in attitudes between right extremists and everyone else in Denmark. Politically extreme citizens on the right might thus be somewhat less positive towards compromising than the rest. Yet, the differences are minor, and the mean values for the right extremists presented in Table 5 show that even among this group, support for compromising is widespread.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics of compromise items in the AUTNES (2020) and original Danish survey (2021) for the 10 percent most ideologically extreme and 90 percent least extreme.

Note: *p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01, based on the t‐test for difference in means.

Effects of compromise willingness on vote choice

The observational analysis provided strong support for H1: Citizens do expect political parties to be generally willing to compromise. The weakness of investigating citizens’ attitudes towards compromising through survey questions, such as the three discussed above, is clearly that it is ‘costless’ for citizens to support compromise in the abstract. On the contrary, it might be considered socially costly to flat‐out reject any compromise, and thus the answers could be affected by social desirability bias. Answers to such survey items thus do not give us a clear measure of the relative importance of attitudes towards compromising when push comes to shove. However, using a conjoint experiment – a survey‐experimental methodology that is useful for evaluating trade‐offs in decision‐making – we can evaluate the causal effect and relative influence of willingness to compromise (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). Because respondents are not asked to evaluate each attribute in isolation, but merely the profile in its entirety, they do not have to admit or acknowledge that compromise willingness is contributing to a negative evaluation. This way respondents can hide potentially socially undesirable attitudes from others and themselves. The abstract character of the choice situation in the conjoint experiment is further well‐suited for trying to capture citizens’ ‘default view’ of compromising. If citizens are asked to evaluate more specific cases of compromising, it is difficult to disentangle their general views from their evaluations of the specific case. The conjoint experiment was embedded in the Danish survey presented above.

In four trials, survey participants were asked to make a forced choice between two hypothetical parties. The forced choice mimics the actual decision‐making process in an electionFootnote 12 and motivates respondents to think more carefully about trade‐offs. The tasks are introduced with the following description: ‘We will now present you with four pairs of hypothetical parties. The parties have different political views and alliances. For each of the four pairs, we will ask you to tell us whether you would prefer to vote for Party A or Party B’. Each specific task then reads, ‘Imagine there is an upcoming election. We will now show you hypothetical examples of parties that could compete in this election. Based on the description below, which party would you be more likely to vote for?’ The instructions vary slightly from task to task, but only enough to indicate that the respondent is making progress. The exact text in Danish is presented in online Appendix B.

The two‐party alternatives are characterized along four attributes, which were made orthogonal through randomization. The dimensions include ideology (far left, centre‐left, centre‐right far right), size (polling at 3 percent or 7 percent),Footnote 13 endorsements of a prime minister (social democratic, liberal or none) and compromise (willing or unwilling). Each level was displayed with equal probability. The attribute levels were randomized independently across respondents, across tables and across attributes. The order of the attributes was also randomized but fixed for each respondent to minimize confusion. This random assignment allows us to estimate the average marginal component effect (AMCE) using OLS regression. The AMCE is an average over the distribution of other attributes, which implies that it is directly interpretable as the causal effect of an attribute on the party's expected vote share after taking into account the possible effects of other attributes. When we evaluate the AMCE of an attribute, the remaining attributes become randomly assigned covariates, which can simply be added to the infinite list of pretreatment covariates (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2023).Footnote 14

However, some of the attributes have been translated from the levels displayed in the forced choice into variables that measure whether the party matches the respondents’ stated preferences. The transformation of the ideological affinity variable follows the same logic as applied in Schneider (Reference Schneider2019): Respondents who self‐place in the same general area as the party obtain a 1, respondents who self‐place one step removed obtain the value 0.67, respondents who self‐place two steps removed obtain the value 0.33, and respondents who self‐place three steps removed, the maximum distance, obtain a 0. The specific coding rules are detailed in the online Appendix. Similarly, we recode the prime minister endorsement into three categories: either the party endorses the voter's preferred prime minister, it endorses the opponent prime minister, or it endorses no one. For respondents who selected ‘other’ as their preferred prime minister, both the social democratic and liberal prime ministers were coded as the opponents. It is important to note that this manipulation breaks with the logic of random assignment and this implies that the groups can no longer be assumed to be equivalent in expectation (Kam & Trussler, Reference Kam and Trussler2017). This should not be a problem for the compromise attribute, which remains unmanipulated, and we can still calculate an unbiased estimate of the AMCE of this key variable.

As stated in H3A, we hypothesize that when a party expresses willingness to compromise this will have a positive effect on the probability of voting for the party. To evaluate this hypothesis, we run linear regressions with clustered standard errors at the level of respondents. We evaluated this with a linear probability model (OLS regression), as is conventional in experimental designs with a dichotomous outcome (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014).Footnote 15 We do not apply survey weights to the analysis of the experiments, as it is recommended to always report the sample average treatment effect (Franco et al., Reference Franco, Malhotra, Simonovits and Zigerell2017).Footnote 16 Furthermore, H3B suggests an interactive effect such that the positive impact of the party's compromise willingness is larger for citizens who themselves are more supportive of compromise.

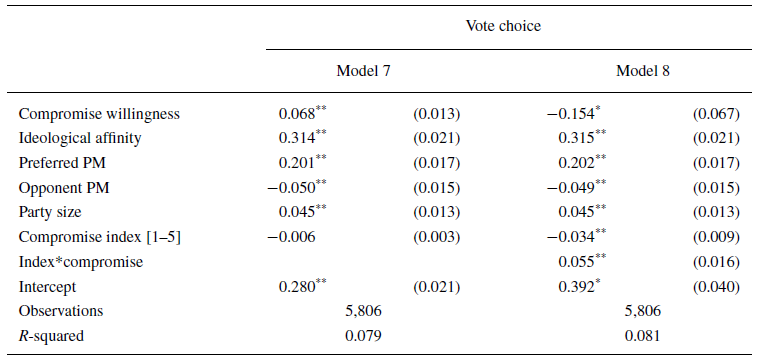

Our main focus is on the compromise attribute. Here, we see a medium‐sized positive effect of being able and willing to compromise. There is a 7 percentage point increase in the probability of choosing a party if it is willing to compromise compared to when it is not. While this effect is clearly not as large as that of ideology, it surpasses both the effect of party size and of endorsing the opponent. Furthermore, the fact that voters express a clear preference for compromise even when controlling for ideology provides support for Hypothesis 3A. Party choice is, as one should expect, clearly driven by ideology and choice of prime minister, but parties’ willingness to compromise has a clear positive effect even when taking these other factors into account. The coefficient estimates are very robust to different model specifications (please refer to online Appendix A).

In addition, Table 6 shows expected effects of ideological affinity and support for a particular prime minister. Voters prefer parties that are ideologically similar to parties that are ideologically distant. Respondents are 30 percentage points more likely to choose a party that is ideologically similar (i.e. within two units of the respondent's self‐placement on the left‐right scale) than they are to choose a party that is on the complete opposite end of the ideological spectrum. Similarly, we find that voters are 20 percentage points more likely to select a party that endorses their preferred prime minister compared to not endorsing anyone, but ‘only’ 5 percentage points less likely to select a party that endorses the opposing prime minister. This suggests that not endorsing someone, or being unclear or vague about your prime ministerial preference, is almost as bad as endorsing the opponent.

Table 6. Average conditional marginal effects of factors predicting vote choice.

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

* p < 0.05,

** p < 0.01.

We also see that respondents are four percentage points more likely to support a medium‐sized party (7 percent), which is sure to gain representation in parliament, compared to smaller parties (3 percent) that are at a considerable risk of not passing the 2 percent electoral threshold. One might speculate about the effect of compromise for larger parties polling around 20 percent or 25 percent; however, we abstained from including this level of the attribute because, in the Danish context, it would clearly lead voters to think about the Social Democrats. We tested the attribute–attribute interaction between party size and compromise willingness and found no significant effect. Thus, voters are no more sceptical of a medium‐sized party compromising than a small party. Results are presented in Table L and Figure B in online Appendix A.

The embedding of the conjoint experiment in the survey further allows us to link the answers to the survey questions included in the compromising index with the responses in the experiment, that is, test H3B. We can thus investigate whether respondents’ attitudes towards coalition formation and compromise in the abstract have any significant effect on how they evaluate the compromising attributes in the experiment. Yet, it is important to be aware that these compromising attitudes are observed, not randomly assigned and, therefore, the results should not be interpreted as a claim that these attitudes are casually related to party preferences in the experiment, but rather as a prescription of conditional AMCEs (Kam & Trussler, Reference Kam and Trussler2017).Footnote 17

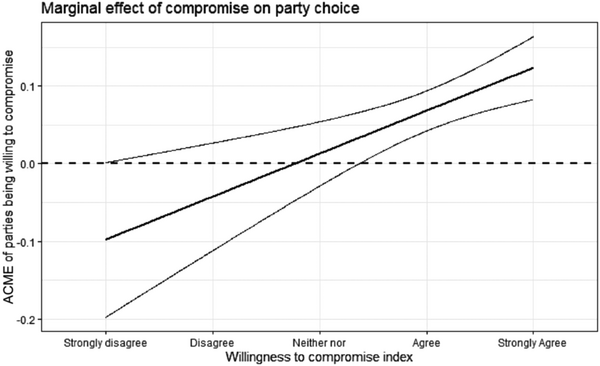

In Model 2 of Table 6, we interact these pre‐treatment attitudes with the choice attributes of the experiment. The results are further presented in Figure 1. In the two questions included in the index, respondents were asked whether the willingness to compromise was important for the country and something they valued in a party. For respondents who completely disagree with both statements, there is a 10 percentage point decrease if the party is able and willing to compromise, but this effect is not statistically significant at the conventional 0.05 level. However, if the respondent agrees more with the statement, the effect of compromise increases significantly and becomes a net positive. For respondents who completely agree with both statements, there is a statistically significant 12 percentage point increase in the probability of selecting a party that is willing to compromise. In Table K and Figure A Appendix A, we show the marginal effects of compromise by agreement with ‘compromise means selling out on one's principles’ and arrive at the same conclusion. This provides strong support for H3B. Thus, support for compromise as an abstract norm seems more than just cheap talk. The respondents who express strong support for compromise as a democratic norm are also significantly more likely to indicate preferences for a party that puts an emphasis on compromising.

Figure 1. Average conditional marginal effect of compromise by levels of the compromise index.

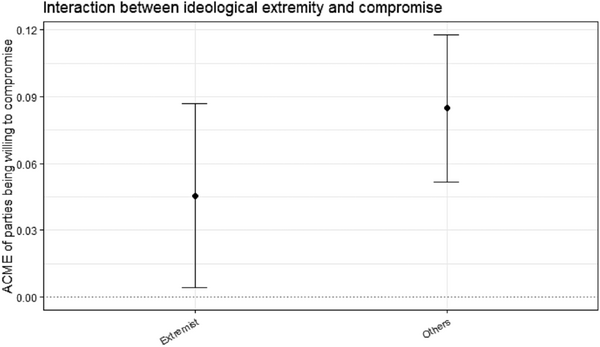

Returning to the question of political extremity, Figure 2 displays the marginal effect of the compromise attribute for left or right extremists (grouped together) and all others.Footnote 18 There is a slight negative interaction effect, meaning that there is less of a positive effect of compromise for the ideological extreme, but the effect is nowhere near significant. Again, we conclude that there is widespread support for inter‐party compromise.

Figure 2. Average conditional marginal effects of compromise by ideological extremity.

Conclusion

Do citizens in Western Europe equate compromise with representational failure? If the answer is yes, as recently claimed by Fortunato (Reference Fortunato2021, pp. 40−60), one should be seriously worried on behalf of the many West European countries where coalition formation is vital for stable governance. A confirmatory answer would be even more worrying in light of the increased fragmentation of almost all West European countries, which exacerbates the need for compromising in order to form viable coalitions.

This paper, however, provides evidence in support of a different answer. Citizens in Western Europe seem to have a ‘compromising mindset’ (Gutmann & Thomson, Reference Gutmann and Thompson2010). It is well‐documented that vote choice, as also found in the conjoint experiment, is strongly driven by ideology (citizens vote for a party that is ideologically close to their own views) and preferences around the ideological profile of the prime minister – but citizens also put emphasis on a party's willingness to compromise. Further, this support for compromising appears to be relatively independent of specific forms of coalition politics, as it was found in both Austria and Denmark and also to be widespread among citizens, notably including the politically extreme.

Our focus on Austria and Denmark naturally raises the question of generalization. Our focus is on Western Europe, where coalition politics often is the norm. Here, our focus is on two rather different forms of coalition politics. Austria most often has majority coalitions and Denmark typically has minority governments. These two cases thus provide enough variation to make a generalization to most countries in Western Europe warranted. Yet, the compromising mindset may not exist in a country like the United Kingdom with a limited tradition for coalition politics or Spain where coalition politics has only more recently become the norm. The question of generalizability is further closely linked to the question of what generates the compromising mindset. Wolak's (Reference Wolak2020) study of the United States argues that citizens’ expectations of political parties to be willing to compromise stems from socialization into democratic norms and could thus be expected to be generalizable to democracies broadly. Yet, an alternative mechanism would be that the compromising mindset is due to citizens’ experience of coalition politics and thus compromising is conducive to an effective political system. Such a mechanism would imply a much more limited potential for generalizability to primarily West European countries with a long tradition of coalition politics.

Austria and Denmark further share a common experience with extreme parties. Large successful radical right‐wing parties, FPÖ in Austria and the Danish People's Party, have gained substantial policy influence through government participation or support party status. This experience might have shaped how especially extreme right voters view compromising. Thus extreme right voters in countries where extreme right parties have not gained much influence may be more sceptical of compromising. This question can only be answered by studies of additional contexts and again focused on the question of whether a compromising mindset stems from democratic socialization or past experience with compromising among political parties. The fact that extreme right voters in Austria were found to be less accepting of compromising than extreme right voters in Denmark would further indicate that the specific experience with radical right‐wing parties gaining influence matters.

The most important implication of our finding of the existence of a ‘compromising mindset’ (Gutmann & Thomson, Reference Gutmann and Thompson2010) is the need to not just focus on whether citizens either accept or react negatively to compromises being made, that is, the costs of compromising (Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2021, pp. 61−90). A compromising mindset implies that citizens actually expect political parties to compromise and might also react negatively when they do not do so. For instance, citizens might react negatively when political parties do not enter government and thus do not contribute to governance. For vote‐seeking political parties, compromising is thus not only a matter of avoiding potential blame. When citizens expect political parties to compromise and they actually do so, political parties may also have opportunities for credit‐claiming. This does not necessarily make life simpler for vote‐seeking political parties – they risk being punished both when they compromise and do not compromise – but contains good news for countries with fragmented party systems where coalition politics and compromising is a must for governance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Thomas Meyer, Carolina Plescia, Rune Slothuus, Rune Stubager, Mathias Tromborg, and the participants in the Department of Government Monday Seminar at the University of Vienna for their constructive criticism of earlier versions of the article. The authors thank the Department of Political Science, Aarhus University, who generously funded the collecting of survey data in Denmark. The authors are also grateful for the comments and suggestions of two anonymous reviewers, which undoubtedly helped to improve the manuscript.

Data availability statement

This article relies on both secondary and original data sources. The secondary data sources can be acquired at https://cses.org/data‐download/cses‐module‐5‐2016‐2021/ and https://data.aussda.at/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.11587/QDETRI. The original survey data was collected by YouGov between 29 October and 10 November 2021. This data file, along with the questionnaire/codebook, and all replication files are available through EJPR's website.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: