Introduction

Peer support has been identified as a core component of recovery-oriented mental health services. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO)’s (2021, p.9) Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan states that Peer Support Workers (PrSWs) are a ‘core service requirement’ while, more recently, Winsper et al. (Reference Winsper, Crawford-Docherty, Weich, Fenton and Singh2020) in their systematic review, identified peer support as one of the main types of recovery-oriented interventions.

Peer support is a relatively broad concept which is used to refer to many various forms of support across different types of shared experience. It can refer to: informal support provided by families and friends; informal mutual support (e.g. through groups and/or online fora); and formal peer support work provided within the context of a clearly defined role (e.g. PrSWs). However, all have in common the use of a person’s own lived experience to help support others. As Voronka (Reference Voronka2019) has highlighted, there may be complex issues of power, identity, role clarity and values tensions in this work and it may involve wider changes to the general culture and approach of services.

This rapid scoping review was commissioned by the Peer Support Five Year Strategy Working Group which was established by the Irish Health Service Executive’s Mental Health Engagement and Recovery Office to create a five-year strategic plan for mental health peer support. The Health Service Executive (HSE) provides public health and social care services to everyone living in the Republic of Ireland, which has a population of approximately 5.9 million people. The Mental Health Engagement and Recovery Office focuses on providing guidance and support for recovery approaches and meaningful engagement.

There has already been considerable work completed in the Republic of Ireland on developing and implementing peer support work. For example, in 2006, the mental health policy, A Vision for Change (Department of Health and Children 2006), highlighted a need for the further development of peer-provided services and peer support work roles across sectors and levels. The focus of this review is on peer support work but it is also relevant to note that the number of peer-provided services remains low. In 2015, Advancing Recovery in Ireland produced Peer Support Workers – A Guidance paper (Naughton et al. Reference Naughton, Collins and Ryan2015) and a programme was launched to support the appointment of PrSWs in the HSE’s mental health services. In 2017, the HSE’s National Framework for Recovery in Mental Health (Health Service Executive 2017) reinforced the recovery approach to providing mental health care and support, including the centrality of lived experience and co-production at all levels of the design, delivery and evaluation of services. Most recently, in 2020, the Department of Health’s Sharing the Vision: A Mental Health Policy for Everyone (Department of Health 2020) continued the strategic direction to further develop peer roles. By 2023, 30 PrSWs and 11 Family Peer Support Workers (FPrSWs) had been appointed (Mental Health Engagement and Recovery Office 2023).

This rapid scoping review was conducted to help inform the new strategic plan for mental health peer support. Specifically, the review focused on the literature on mental health peer support work, where the PrSW worker has their own experience of, and is supporting others with, mental health difficulties.

The specific objectives of the scoping review were:

-

1. To identify and critically appraise the available evidence on peer support workers in mental health services; and

-

2. Ascertain how such work may be best implemented.

Methods

This review was a collaboration between the Peer Support Five Year Strategy Working Group and a research team who were commissioned for this project. The research team was representative of various professional, academic/practitioner and lived experience backgrounds, all in paid positions. The Working Group and research team discussed and agreed the design of the review at each key stage. A scoping review was identified as the most appropriate approach mainly because the objectives of this work were relatively broad. According to Munn et al. (Reference Munn, Pollock, Khalil, Alexander, Mclnerney, Godfrey, Peters and Tricco2022), p. 950), a scoping review ‘…aims to systematically identify and map the breadth of evidence available on a particular topic, field, concept, or issue, often irrespective of source (i.e. primary research, reviews, non-empirical evidence) within or across particular contexts’ (p. 950). It is ideally suited to clarifying concepts, scoping a body of literature across different types of evidence, and identifying knowledge gaps (Munn et al. Reference Munn, Peters, Stern, Tufanaru, McArthur and Aromataris2018).

The Peters et al. (Reference Peters, Marnie, Tricco, Pollock, Munn, Alexander, McInerney, Godfrey and Khalil2021) framework for completing scoping reviews was used here and involves the following steps: defining and aligning the objectives and questions; developing and aligning the inclusion criteria with the objectives and questions; describing the planned approach to evidence searching, selection, data extraction and presentation of the evidence; searching for, selecting, extracting and analysing the evidence; presenting the results; summarising the evidence in relation to the aims of the review, making conclusions and noting any implications of the findings. The scope of the review was very broad and so a rapid scoping review approach was adopted. This approach, sometimes referred to as a Big Picture Review, is appropriate when: there is considerable, relevant research; time and resources are limited; and the aim is to provide an overview of the existing literature (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Sutton, Pollock, Garritty, Tricco, Schmidt and Khalil2025). This approach, in contrast to a conventional scoping review, offers greater flexibility with some aspects of the process, including, for example, the extent to which data extraction and reporting can be tailored and limited to address the objectives of the review within the available resources.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were decided in line with the population, concept and context model as recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute’s Manual for Evidence Synthesis. The main population inclusion criteria were PrSWs (with experience of mental health problems) and FPrSWs (with experience of caring for someone with mental health problems). The focus was on formal, employed (paid or unpaid) roles and not on informal peer and family peer support. The main concept inclusion criteria were the definition, role, implementation and development of mental health peer support and family peer support work. The main context inclusion criterion was mental health peer support work and mental health family peer support work across all sectors, all settings (community, inpatient, specialist) and all countries. The types of literature included were primary research studies, reviews, guidelines and policy documents.

The databases identified as most appropriate were: Social Sciences Citation Index, PsycINFO, MEDLINE and Social Policy and Practice. Hand searches of grey literature and relevant website searches, identified by the Peer Support Five Year Strategy Working Group and through interviews with key national and international experts, were also conducted to identify other relevant policies, guidelines, reports and evaluations. The search terms included:

“peer support” or “peer worker*” or “consumer worker*” or “lived experience worker*” or “expert by experience” or “family peer support” or “peer led support”

AND

“mental health” or psychiatric or “mental illness*” or CAMHS or “child and adolescent mental health service*” or “forensic psych*” or “specialist mental health service*”.

Searches were restricted to literature from 1990 onwards, when developments in peer support really started to accelerate. They were also restricted to literature in English.

Screening was conducted independently by two members of the research team; this initially involved screening by titles and abstracts and then full texts. Any differences during the double screening were resolved by a third member of the team. The database searches identified a high number of potentially eligible sources. These were then organised into themes which were identified independently by the three members of the research team who had been involved in the screening process, then agreed through discussion. Within each theme, the most informative, relevant and representative literature was then selected. In addition, the identified themes were also checked and further explored in the series of interviews with key national and international experts.

Results

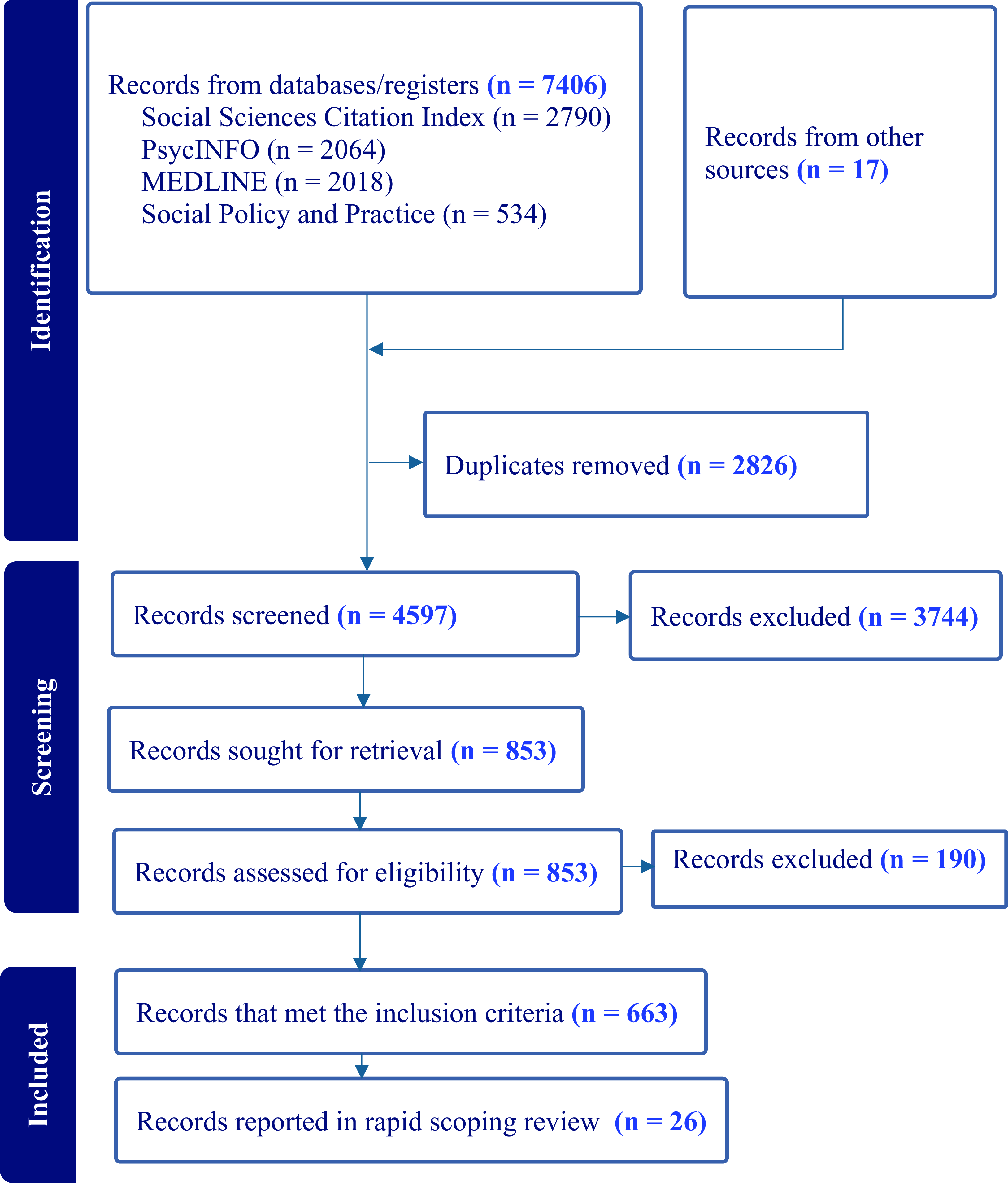

A total of 663 of the original 7406 potentially eligible records were identified as meeting the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were deliberately broad to provide an overview of the existing literature, but it would have not been feasible to report on each of the 663 within the time and resource constraints. These were then organised into the main, albeit overlapping, topics to be explored in the review: definitions; values and principles (n = 82); the role of the Peer Support Worker (n = 188); development and implementation (n = 85); experiences of Peer Support Workers (including perceptions of others) (n = 124); recruitment of Peer Support Workers (n = 9); training (n = 33); and effectiveness (n = 142). Based on discussion within the research team, the sources that were considered most informative and useful were then selected (n = 26) with a specific prioritisation of existing reviews of the research evidence (n = 7). The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram (Fig. 1) presents the main stages of the review. The findings are presented below in a number of sections.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Definitions

An influential perspective on peer support, referred to as ‘Intentional Peer Support’, was developed in the 1990s by Shery Mead in the US and others. ‘Intentional’ refers to having the specific purpose of communicating ‘in ways that helps both people step outside their story…It means that in real dialogue, we are able to step back from our truth and be very deeply open to the truth of the other person while also holding onto our own. When this type of dialogue occurs, both of us have the potential to see, hear, and know things in ways that neither of us could have come to alone’. (Mead Reference Mead2014, pp. 7–8). Stratford et al. (Reference Stratford, Halpin, Phillips, Skerritt, Beales, Cheng, Hammond, O’Hagan, Loreto, Tiengtom, Kobe, Harrington, Fisher and Davidson2019, p. 630) used an international consortium of peer leaders to develop an international charter on mental health peer support which defined peer supporters as ‘people who have experienced mental ill health and are either in or have achieved recovery…[and] they use these personal experiences along with relevant training and supervision, to facilitate, guide, and mentor another person’s recovery journey…’.

More recently, Davidson et al. (Reference Davidson, Chinman, Sells and Rowe2006) identified three main forms of peer support: (1) naturally occurring mutual support groups; (2) consumer-run services; and (3) the employment of consumers as part-or full-time providers (with clearly defined roles) within clinical and rehabilitative settings. The last of these was the focus of this review.

Values and principles

In relation to the values and principles of peer support work, the National Framework for Recovery in Mental Health (Health Service Executive 2017) identified four principles for all recovery and recovery-oriented services in Ireland. While these apply more generally than to peer support work alone, they are still directly relevant and also important for the organisational context: These refer respectively to: the centrality of the service user lived experience; the co-production between all stakeholders of recovery-promoting services; an organisational commitment to the development of recovery-oriented mental health services; and supporting recovery-oriented learning and practices across all stakeholder groups.. Likewise, Repper (Reference Repper2013), in the UK, identified eight core principles of peer support which included: mutuality, reciprocity, a non-directive approach, a recovery-focus, strengths-based, inclusive, progressive and safe. As mentioned earlier, Mead (Reference Mead2014) highlights the importance of ‘authenticity’ as a key principle, which involves honest, transparent and sincere acts of mutual sharing and learning from lived experiences.

The role of the peer support worker

Watson (Reference Watson2019) provides a useful overview of the ways in which peer support can be provided across settings whilst also highlighting a need for greater clarity about the responsibilities of the role. For example, she cautions that in more formalised roles, such as PrSWs in mental health services, the key peer support values of mutuality and reciprocity may be compromised. Both of these values are repeatedly highlighted in the literature to be key aspects of the distinctive contribution of peer support work but also, possibly, aspects of peer support work that can help inform and change more traditional approaches to mental health support across professions. Involvement in this type of work (e.g. recovery training for staff) may help bolster the role of PrSWs by making positive connections with staff whilst also helping to clarify the benefits of peer support in recovery.

Development and implementation

There are a number of sources of guidance and toolkits for the development and implementation of peer support (e.g. Repper Reference Repper2013; Kent Reference Kent2019; Health Education England 2020; Mental Health Engagement and Recovery Office 2020; Watson & Repper Reference Watson and Repper2022; Scottish Recovery Network 2023). Together, these guidance documents and toolkits provide very helpful direction on the wide range of issues that need to be considered in developing, recruiting and supporting PrSWs.

A number of reviews have been conducted in order to investigate the development and implementation of peer support work in mental health services. For example, Ibrahim et al. (Reference Ibrahim, Thompson, Nixdorf, Kalha, Mpango, Moran, Mueller-Stierlin, Ryan, Mahlke, Shamba, Puschner, Repper and Slade2020) conducted a systematic review comprising 53 papers which focused on identifying facilitators and barriers to implementation. These included: organisational culture; training; role definition; staff willingness to work with PrSWs; resource availability; financial arrangements; support for PrSWs’ wellbeing; and PrSWs’ access to a peer network.

More recently, Mutschler et al. (Reference Mutschler, Bellamy, Davidson, Lichtenstein and Kidd2022) conducted a systematic review (19 studies) focused on the implementation process, the findings of which were organised into several domains using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. These included ‘innovation’ (in this case peer support work); ‘the outer setting’ (i.e. policy, population and wider context); ‘the inner setting’ (i.e. organisation and culture); the roles and characteristics of the individuals involved at all levels; and the implementation process. With regard to the innovation domain, the authors reported that while the evidence base for peer support work was well established, it needs to be continuously articulated as many non-peer staff still had misconceptions about the role. Within the outer setting, the need for clear, precise and accessible policy was highlighted, while with regard to the inner setting, a positive and accepting organisational culture is needed, coupled with appropriate resources, leadership and support for implementation of recovery-oriented approaches including peer support work. The individual domain includes the PrSWs themselves, but also the support, engagement and education of all staff and across levels. Finally, the importance of initial and ongoing training for all was reinforced as central to the implementation process.

The findings also highlight some interesting variations across the world. For example, Ong et al. (Reference Ong, Yang, Kuek and Goh2023) completed a scoping review on the implementation of peer support services in six countries in Asia, the findings of which highlight the importance of political and cultural factors and contexts. For instance, the focus on the family as the central means of support in China, may inhibit implementation, whilst in Singapore, and Israel, there may also be less openness to peer support services due to the dominance of the biomedical model in these countries.

Experiences of peer support workers (including perceptions of others)

The experiences of PrSWs are important to the development, implementation and effectiveness of their work. For example, Scanlan et al. (Reference Scanlan, Still, Radican, Henkel, Heffernan, Farrugia, Isbester and English2020) found that PrSWs’ (n = 67) self-ratings of job satisfaction, turnover intention and burnout were not significantly different from other staff in the mental health workforce. In terms of motivation, they reported that PrSWs were keen to use their lived experience to support others, improve mental health services and make a difference. They highlight the positive impact of strong team culture and relationships, but conversely, the negative impact on PrSWs when they do not feel valued by other employees, thereby suggesting an ongoing need for education and training for non-peer staff. Gillard et al. (Reference Gillard, Foster, White, Barlow, Bhattacharya, Binfield, Eborall, Faulkner, Gibson, Goldsmith, Simpson, Lucock, Marks, Morshead, Patel, Priebe, Repper, Rinaldi, Ussher and Worner2022) used a longitudinal mixed methods design to explore the impact of working as a peer worker in mental health services in the UK (n = 32). The findings suggest that PrSWs have levels of wellbeing comparable to the general population. While there were some decreases in wellbeing at four months, these were largely not maintained at 12 months. They reported that there were positive impacts of working in the peer support role which included feeling valued, empowered and connected. Positive pay and working conditions were also associated with satisfaction. Some also report that the work could be emotionally and practically difficult. Likewise, Edwards & Solomon (Reference Edwards and Solomon2023) found that key factors related to job satisfaction among mental health PrSWs in the US (N = 645) were co-worker support, perceived organisational and supervisor support, and job empowerment.

A key theme identified within the peer support development and implementation literature is the importance of the readiness and response of other staff in mental health services. For example, Korsbek et al. (Reference Korsbek, Vilholt-Johannesen, Johansen, Thomsen, Johansen and Rasmussen2021) identified three main factors to be important in this regard in their study of the views and experiences of non-peer mental health providers on working with peer support colleagues in Denmark. The first of these related to how the relationship between the peer and non-peer workers was perceived, with the non-peer workers identifying and valuing the additional contribution of the peer workers (i.e. as an equal colleague but with a different and positive role in the service). The benefits of working with peers were also highlighted especially in relation to giving hope and providing a bridge between service users and services. There were some concerns identified, especially early in implementing peer roles, about issues of confidentiality and information sharing, different working conditions and the nature of relationships between peer workers and service users, especially in relation to boundaries and self-care. It is interesting to note that these concerns were, to some extent, related to aspects of the flexibility and benefits of peer support work. Likewise, in Australia, Parker et al. (Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Wyder, Pommeranz, Walgers and Meurk2023) used a grounded theory approach to better understand the experiences of staff during the process of implementing PrSW roles in a community-based rehabilitation service. They highlighted some of the positive impacts of this integrated staffing approach with both peer and non-peer staff reporting that the PrSWs’ role and experience were valued but that it had been a steep learning curve for all involved.

Recruitment of peer support workers

The process of recruiting PrSWs is an important aspect of the available guidance and toolkits on peer support work while there are also some helpful accounts of the relevant issues in the research literature. In the UK, Simpson et al. (Reference Simpson, Flood, Rowe, Quigley, Henry, Hall, Evans, Sherman and Bowers2014) completed an evaluation of the selection, training, and support of PrSWs in a service to support people discharged from inpatient care. The recruitment and selection process included a role description and person specification, advertising the opportunities and a two-stage selection process involving a telephone interview and an open day. The training was delivered one day a week over twelve weeks and was evaluated using the Nottingham Peer Support Training Evaluation Tool. Overall, the findings were positive, including the content and role-plays, although some felt they could have been better prepared for the level of emotional impact involved in the work including, for example, the process of ending peer support, and the need for more preparation to work with families. The individual supervision and group support provided, were viewed very positively.

In Germany, Lammers et al. (Reference Lammers, Dobslaw, Stricker and Wegner2023) explored the motives of 23 PSWs, all of whom were volunteers. They identified a number of aspects relevant to the recruitment and motivation of prospective PrSWs including: developing their own understanding, competence and skills; expressing their values through helping people and reciprocating for some of the support they had received; and developing their careers and improving their self-esteem and confidence. More specifically, most of the participants identified the importance of their own experiences in providing expertise and potential benefits to others and to promote wider change within services.

Training

The importance of training for PrSWs and guidance for all other staff about the role, has been repeatedly identified in the guidance and research literature. For instance, Opie et al. (Reference Opie, McLean, Vuong, Pickard and McIntosh2023) conducted a rapid review of the content and outcomes of training for PrSWs. They included 36 studies, and identified 22 topics across the content of the courses including, for example, communication skills; help-seeking pathways/referrals; information about mental health; peer helping/peer advocacy principles; personal recovery; self-disclosure; the care/treatment/service system. They also reported the combination of methods of teaching used which included: group/peer support; role play/experiential practice; scenarios; and sharing personal experiences.

Effectiveness of peer support work

The question of the effectiveness of peer support is an important one in terms of identifying the types of interventions, approaches and services that work best for whom and under what circumstances. There are obvious challenges here because, peer support is not a single intervention, but instead, refers to a broad range of work and concepts. Walker & Bryant (Reference Walker and Bryant2013) carried out a meta-synthesis of qualitative research, findings, the results of which showed that, in general, service users tend to view the role of peer workers very positively, with reported experiences and feelings of increased hope, motivation and better social networks. The study findings also imply that service users can build rapport with peer workers more easily than other types of staff. The review does note, however, that a minority of service users held negative views of peer workers due to their perceived lack of formal training and their own diagnosis of a mental health problem. It is also worth noting, from this study, that non-peer staff had positive views of peer workers whom they felt were instrumental in increasing empathy and understanding toward service users in general.

A more recent ‘umbrella’ review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Yim et al. Reference Yim, Chieng, Tang, Tan, Kwok and Tan2023) (or ‘review of reviews’), based on a total of 13 reviews, concluded that peer support work is generally effective, particularly with regard to recovery-oriented, as opposed to clinical and psychosocial, outcomes. With regard to the first of these, increases in empowerment, self-efficacy and hope were the most frequently reported positive outcomes. For instance, 8 of the 13 reviews showed that peer support was important in increasing hope and empowerment.

Although family peer support was included in the searches, there was very limited literature identified specifically on these types of roles. This may have been a limitation of the search strategy which used very specific terms for family peer support work. The research and anecdotal evidence that was identified suggests that family peer support is beneficial by helping to alleviate carer burden, increase wellbeing and contribute to improved outcomes but there is a lack of good quality data (e.g. Hopkins et al. Reference Hopkins, Kuklych, Pedwell and Woods2021).

The research on the cost-effectiveness of peer support (as with much of the field of mental health interventions) is very limited and only a very small number of studies have included economic evaluations. An interesting, albeit now 10-year-old, report by the UK-based Centre for Mental Health (Trachtenberg et al. Reference Trachtenberg, Parsonage, Shepherd and Boardman2013) identified six studies in this field that examined the associations between the employment of PrSWs and inpatient bed usage. The weighted average cost benefit ratio was 1:4.76; that is, for every £1 spent on peer support, £4.76 was saved on bed usage.

In summary, the general effectiveness literature on peer support, while far from conclusive, provides some promising findings. There is, however, a need for studies which identify key aspects of peer support work and test their effectiveness (and cost-effectiveness) compared to some form of control group. It is also important to remember that ‘current gaps in implementation and limitations in the evidence base should be viewed not as obstacles to its adoption, but as building blocks for more consistent service integration and thoughtful empirical research’ (Yim et al. Reference Yim, Chieng, Tang, Tan, Kwok and Tan2023, p.17).

Discussion

The overarching aim of this review was to examine the role of PrSWs and the implementation of peer support across the world. Notably, the review was conducted by a team representing a range of professional, academic/practitioner and lived experience backgrounds. The findings reported here have a number of important implications for the further development of peer support work and family peer support work in Ireland and elsewhere. While there are several helpful definitions of peer support, peer support work and family peer support work in the literature, the roles of PrSWs and FPrSWs are still developing. In addition, although lived experience is a central component of both roles, the evidence reported here, suggests that these roles also require specific training, knowledge, skills and values.

The findings, especially from the guidance and toolkit documents, also suggest a need to consider carefully the ways in which individuals can be encouraged and supported to become PrSWs/FPrSWs. These may include providing: introductory courses; reasonable adjustments for all forms of disability; financial support for initial training, initial training as part of the role; and identifying and addressing potential barriers to becoming a PrSW or FPrSW, including for specific, underrepresented groups. The recruitment process for specific roles also needs to be carefully considered, with a focus on motivation, values and skills, especially interpersonal skills, so effective ways to assess these should be developed and utilised. In addition to initial training, there is a need for ongoing specific training for PrSWs and FPrSWs (including accredited qualifications at all levels) as well as access to all relevant general, multi-disciplinary and inter-agency training. The focus of this review is on formal, employed roles, but it may also be important to consider how these roles may interact with, and complement, the spectrum of informal caring roles in services, across sectors, communities and families.

A key message from the literature on the development and implementation of peer support work is the need for training for all professions to help them understand the role of PrSWs and FPrSWs. This training should be co-produced and consideration given as to for whom this should be mandatory. Arguably, training at some level, is needed for all staff involved. Assessment of the readiness of multi-disciplinary teams and services to adopt PrSW roles is recommended and should include training, support and supervision arrangements. Access to peer supervisors as well as line management supervision, is also highlighted as an important component of the effective implementation of peer support work and family peer support work and there may be possible attendant training needs for peer supervisors.

The development and implementation literature also identified the importance of a clear career structure for these roles, including more senior roles in the direct provision of support as well as supervisory and leadership roles at all levels, including in senior management. The research literature also repeatedly identifies the need to protect PrSWs from isolation. The literature also reports ongoing issues of power imbalances, stigma and discrimination. Training, ongoing support, supervision and supportive networks may help to address these issues.

The collective findings reported here can help inform and support the further development of PrSW and FPrSW roles in mental health services in Ireland and the wider transition to more recovery-oriented services. We have highlighted a need for further rigorous, co-produced research on the effectiveness of peer support work and family peer support work as components of recovery-oriented services. This should include conventional research designs, such as randomised controlled trials focused on outcomes for service users, but there is also a need for further exploration of the complex and distinctive aspects of peer support work, such as the potential value and effectiveness of a worker who is clearly and positively identified as a peer and what this may symbolise and enable for anyone receiving the support. Further research should also further explore, from all relevant perspectives, the barriers and enablers for the effective implementation of authentic peer-support work such as service culture, structures, leadership and support. Peer support workers may also provide important perspectives on how other aspects of mental health services could develop.

Overall, the research literature included in this review is largely positive about the impact of these roles, but the service evaluation studies are based mainly on qualitative data. While these are important and useful findings, research designs which include comparison groups, and ideally randomisation, would more convincingly establish the effectiveness of peer support work and family peer support work, including exploration of specific aspects of these roles. There is also a need for well-designed research on the cost-effectiveness of these roles both in Ireland and elsewhere. There is a need to continue this exploratory endeavour to build on the foundations from which the validity of peer support has been built. In the spirit of co-production, the lived experience should continue to be recognised as a credible source of knowledge, the potential for its contributory efforts for improvements to the world of mental health, policies and practices furthered.

Financial support

This work was commissioned by the Peer Support Five Year Strategy Working Group of the Mental Health Engagement and Recovery Office which is part of the Health Service Executive in the Republic of Ireland.

Competing interests

Michael John Norton, Paul Clabby, Belinda Coyle, Julie Cruickshank, Martina Kilcommins, Emma McGuire, Mary O’Connell-Gannon and Derek Pepper are members of the Peer Support Five Year Strategy Working Group which commissioned this report.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.