Introduction

Much scientific progress has been made since the publication of the report by the APSA Taskforce on Inequality in 2004, which defines the starting point for a renewed interest in the inequality of the representational process in the United States and elsewhere. We now know more about the unequal nature of government responsiveness in the United States, as for example the seminal work by Bartels (Reference Bartels2008) or Gilens (Reference Gilens2012) document. We have further learned that the phenomenon of unequal representation of income groupsFootnote 1 is not confined to the United States and is present also in European societies (Elsässer et al Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2017; Peters & Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2015; Giger et al Reference Giger, Rosset and Bernauer2012), as well as in Latin America (Lupu & Warner Reference Lupu, Warner, Joignant, Morales and Fuentes2017).

However, important questions remain unanswered as the current literature focuses on representation of preferences almost exclusively. While certainly democracies should be judged by how well preferences of their citizens match with government policies, other aspects of representation are crucial as well. An important dimension is how issue priorities of citizens get channeled into the political system: Do governments pursue policy actions on issues that citizens consider important? Do they tackle problems that citizens conceive as salient? As Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1960) argued seminally, if certain issues are denied access to the agenda, preference incongruence might be less of a concern as individuals will not deem the government responsive to their wishes in the first place. Government officials face trade‐offs in how much attention they can devote to issues (Jones Reference Jones1994) and thus the government agenda is the result of decisions to prioritize certain issues above others.

We understand agenda representation as an important aspect of government responsiveness. We label agenda responsiveness as a government's activity that takes up salient concerns in the population (see also Jones et al. Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009; Jones & Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2004). This dimension of representation constitutes another instance where citizens potentially are treated unequally based on their social status. Biases in the prioritizing of issues can have severe consequences for citizens’ satisfaction with their government and the democratic system at large. We investigate two related questions to shed light on how unequal agenda representation is spread across European societies. First, do high‐ and low‐status citizens have different visions of what deserves the government's attention? Second, if divergent visions prevail, do governments pay more attention to issues the affluent consider a priority than to what the less affluent identify as a problem?

In our study, we compile a dataset that comprises of 10 European countries over a 13‐year period (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom). We match the coding of ‘most important issue’ questions from the Eurobarometer to the Comparative Agenda Project (CAP) coding scheme and merge information on issue priorities with information on bill introduction in the respective policy areas. Importantly, issue priorities have been separately coded for rich, middle‐class and poor citizens in order to analyse priority differences and inequality in agenda attention. We utilize three case studies (Germany, Spain and United Kingdom) where longer time series from individual country surveys enable us to assess within‐country variation in addition to the cross‐sectional sample.

While our approach for assessing the agenda representation among status groups is quite expansive and covers a larger variety of topics and cases, we necessarily also set aside some finer details of policy making in the broad picture presented here. First, we adapt a more narrow perspective on agenda representation than Bevan and Jennings (Reference Bevan and Jennings2014), for example, and consider only legislative output. We believe a focus on legislation is warranted as law making is the central arena for agenda setting. Legislation captures the priorities of policy makers (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). It is also the only available data source for our comparative approach.

Second, our approach does not allow us to investigate the ideological or policy direction of a bill. Instead, we rely on ample existing evidence showing that when governments are unequally responsive, they are taking action to the detriment of the poor (Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Peters & Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2015; Donnelly & Lefkofridi Reference Donnelly and Lefkofridi2014). Since we focus on citizens’ policy priorities rather than preferences, we cannot make claims about the concrete preferences in policy areas all citizens deem important. We argue, however, that representation of the disadvantaged can only occur if the government and parliament address policy areas that these groups consider important. Responding to policy preferences in unimportant areas should not be considered good representation.

Our descriptive findings indicate that high‐ and low‐status citizens indeed possess different agendas of what they consider important topics. An intuitive example is that less affluent consider the threat of unemployment much more a problem than more affluent citizens. Our subsequent regression estimates indicate that the most important issues of the affluent influence the government agenda to a larger degree than those of low‐status citizens, especially if priorities between high‐ and low‐status groups diverge. Our findings highlight that – already at the agenda‐setting stage of representation – the less affluent are disadvantaged.

Our study provides important updates for the way we think about unequal representation. Our results suggest that inequality in representation manifests itself in multiple forms. Our study thus highlights the importance of broadening the focus beyond inequalities of preferences. The consequences of an unequal treatment of citizens at the agenda‐setting stage of the representational process are far‐reaching if issues held important by more affluent citizens are given attention while those prioritized by the less affluent are not. Agenda denial of some segments of society effectively excludes them from expressing their preferences and having their problems solved. Combined with the evidence of unequal representation of preferences a nocuous cocktail might be served – especially if priority and preference inequality overlap and accumulate.

Representation and inequality

The classic ‘responsible party model’ (see ‘on Political Parties’, American Political Studies Association Reference American Political Science Association1950; Thomassen Reference Thomassen, E., Mann and Kent1994) describes how an ideal representational process should look like: First, citizens chose a party based on their distinct policy programmes. Second, parties that receive a sizable amount of votes are represented in parliament and finally, the most successful one(s) build(s) a government that implements the policies the parties have announced in their party programme. Thereby, it is ensured that governments enact policies that are wanted by the population and are thus responsive to what their constituencies desire. An important notion within this framework – but also more generally in theories of representation and democracy – is that all citizens should be equal and have equal voice in the democratic process: ‘a key characteristic of a democracy is the continued responsiveness of the government to the preferences of its citizens, considered as political equals’ (Dahl Reference Dahl1971: 1).

A wide range of studies confirm that on a general level, the representation process seems to work: overall, there is a fair degree of congruence between what citizens want and what they get, and governments seem rather responsive vis‐a‐vis public opinion changes (e.g., Stimson et al. Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995; Burstein Reference Burstein2003; Hobolt & Klemmensen Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2008). However, there is also mounting evidence that the principle of equal voice is violated in many democracies: wealthier citizens carry more weight in the policy‐making process. Put differently, high income individuals speak with a loud voice while the poor only whisper in the policy‐making process.

A large body of work documents how the influence of the rich prevails in the United States (e.g., Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Kelly Reference Kelly2009) as well as for a range of European countries (e.g., Donnelly & Lefkofridi Reference Donnelly and Lefkofridi2014; Peters & Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2015) while other studies fail to report a significant advantage of the affluent as the preferences of the income groups over overlap (e.g., Branham et al. Reference Branham, Soroka and Wlezien2017; Enns Reference Enns2015). Bartels (Reference Bartels2008), for example, shows that in the U.S. high income constituents predict the voting behaviour of their Senators to a much larger degree than low income citizens, who have little or no power. Gilens (Reference Gilens2012) collected thousands of opinion polls and analysed how public preferences correspond to government policies. He documents virtually no influence for the poor, while opinions of the rich are significantly related to policy outcomes. Only when the preferences of the poor and rich align, do governments seem responsive to the political opinions of less wealthy citizens. Similarly, studies on European countries have shown that political parties and governments tend to be better aligned with the interests of the rich (Giger et al. Reference Giger, Rosset and Bernauer2012), and the available evidence suggests that government policies rather reflect public preferences of the more affluent than those of the poor (Donnelly & Lefkofridi Reference Donnelly and Lefkofridi2014). While cross‐national differences exist in the degree of under‐representation, there is virtually no case where preferences of the poor are better represented than those of the rich.

What remains contested, though, are the exact mechanisms that are responsible for the unequal representation of income groups’ preferences. There seems to be some variation in the degree of under‐representation according to electoral rules, the degree of macro‐economic inequality, as well as due to the low participation rates of low‐income citizens (Rosset et al. Reference Rosset, Giger and Bernauer2013; Peters & Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2015).

In this paper, we take a different approach. Instead of analysing the representation of political preferences, we shed light on the process of representation by focusing on a different stage of policy making: agenda setting. We argue that equally important for the working of democracy is a government's agenda responsiveness, that is the question of which issues political actors pay attention to and focus on. Policy makers represent citizens also through selectively devoting attention to issues, thereby reflecting the citizens’ concerns, and dealing with political problems on their behalf, that is problem solving as coined by Adler and Wilkerson (Reference Adler and Wilkerson2013).

In most instances, agenda representation is thus a necessary condition for the occurrence of policy representation (Carmines & Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989; Jones & Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2004). Given that public concerns are widespread and government attention is a scarce good, prioritization is needed for spurring government action. Thus, the degree to which a government pays attention to the issues and problems raised by certain constituencies indicates its priorities in representing certain groups within society. Agenda representation is highly consequential for citizens and their satisfaction with the democratic process, as the work by Stefanie Reher (Reher Reference Reher2014, Reference Reher2015) demonstrates. Problem solving is one of the key attributes of electoral success: parties rated competent to tackle certain issues get a large premium from voters (Petrocik Reference Petrocik1996; Lanz Reference Lanz2020).

Agenda setting representation is the subject of a range of works that predominately focus on the American case, where governments are generally attentive to the public's priorities. Single‐country studies in European settings tend to reach similar conclusions (Bevan & Jennings Reference Bevan and Jennings2014; Bonafont & Palau Reference Bonafont and Palau2011; Lindeboom Reference Lindeboom2012), though these works treat the citizenry as one uniform body regardless of socio‐demographic characteristics. Given our interest in unequal representation and the widespread evidence of an unequal treatment of economic groups, we explore the priorities of different social groups in comparison.Footnote 2 Flavin and Franko's (Reference Flavin and Franko2017) pioneering study takes a first step in this direction by analysing how the priorities of rich and poor voters differ in the American states and how these priorities are taken up by policy makers. Their findings reveal that unequal agenda representation is widespread in the United States: state legislatures are less likely to devote attention to an issue prioritized by the poor than to one that is salient to the more affluent.

We expand the empirical scope of existing research and examine unequal agenda representation in a comparative perspective featuring 10 European countries. Not only does such a design allow to put the American findings into perspective, but we also gain leverage of the phenomenon across a range of different institutional settings, and even expand on the sample of countries for which agenda congruence across the whole population has been studied. In general, the European setting can be seen as a more challenging test for unequal agenda responsiveness since multiparty systems are seen as more inclusive and therefore open to new issues (see, e.g., Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999).

Unequal priorities and government responsiveness

In this study, we explore the unequal responsiveness of governments to citizens’ priorities. Before we examine responsiveness, we need to ask whether differences in issue priorities exist between economic groups. Do the poor and the rich differ in what they consider a salient issue in their country? Unequal representation of any kind relies on the (implicit) premise that differences in attitudes, priorities, or other evaluations exist – otherwise partial responsiveness is impossible, and policy actors are either responsive to the whole society or to no one (see also the vivid debate about this point in the literature on unequal preference representation (Soroka & Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2008; Ura & Ellis Reference Ura and Ellis2008; Gilens Reference Gilens2009). It is thus indispensable to study whether differences in priorities exist in the first place. Only in a second step can one analyse how responsive governments are in their attention to different topics.

Starting from the premise that the difference between poor and rich are more than simply earnings, we argue that political priorities differ according to income (see also Flavin & Franko Reference Flavin and Franko2017). Based on social cognitive accounts of social class differences (Kraus et al. Reference Kraus, Piff, Mendoza‐Denton, Rheinschmidt and Keltner2012; Manstead Reference Manstead2018), we posit that the social context is influential not only for our preferences but also for our thinking of what the essential issues of public policy are.

First and foremost, material self‐interest is associated with different expectations about what the state should do and how the government can assist its people (Hacker & Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2002). Low status citizens concentrate their interests on a well‐developed welfare state that assists them when turning ill or losing their jobs. Such assistance is of less relevance to wealthy citizens who do not need to care about each penny and have the means to rely on private markets if needed. As a consequence, we expect poor citizens to focus their attention more on issues of poverty relief, unemployment protection or housing. Different life experience can also enter the equation from another angle, namely through social networks and shared life experiences within the neighbourhood (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Johnston and Lown2015; Thal Reference Thal2017). So living in a poor neighbourhood with a high level of unemployment, crime and social deprivation might have a direct effect on what you consider important irrespective of your own direct experience. Similarly, living in a more affluent neighbourhood affects what one considers important through social discussions with colleagues and neighbours (McPherson et al. Reference McPherson, Smith‐Lovin and Cook2001). In sum, we expect considerations about what is important to be different according to the position within the income strata. We call this discrepancy the priority gap and define it as the difference in the degree of importance between low‐ and high‐status citizens on a policy issue.

Our main research question asks whether governments are responsive to the diverging priorities of high‐ and low‐status citizens. We see government policy making as problem solving (Jones & Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2004; Adler & Wilkerson Reference Adler and Wilkerson2013). Policy making is understood as sequential and starts with the agenda‐setting stage, the struggle over preferences comes only in a later phase (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Larsen‐Price and Wilkerson2009; Klüver Reference Klüver2020). In fact, the power to set the agenda, to determine which issues are important enough to be treated by the government has long been recognized (see, e.g., Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960; Bachrach & Baratz Reference Bachrach and Baratz1962) and has been central to policy making in the seminal study by Kingdon (Reference Kingdon1984).

Governments face trade‐offs in determining which problems or priorities to consider and to devote resources and attention to. Assuming that priorities are stratified according to income as argued above, the key question becomes how public officials prioritize among topics salient for different societal groups. We argue that faced with a trade‐off, governments tend to prioritize what the more affluent consider important while devoting less attention to the priorities and problems of the less affluent. We identify three mechanisms that help us in accounting for this process. They share the assumption that legislators care for their re‐election and are thus vote maximizers.

First, different political participation rates are crucial, in particular the fact that low income is associated with lower participation and less political activism in general (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Verba and Lehman Schlozman1995; Gallego Reference Gallego2014). If low‐status citizens turn out less and contact politicians less, this makes them not only less visible (see, e.g., Griffin & Newman Reference Griffin and Newman2015) but also less important in the eyes of politicians facing re‐election. Differences in visibility skew agenda representation towards those who participate more and are more active in politics.

A second mechanism is the direct influence of money, which runs either via campaign contribution or lobby groups. Wealthier citizens are more likely to contribute to political campaigns than citizens with a low income (Schlozman et al. Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2012; Brady et al. Reference Brady, Verba and Lehman Schlozman1995). While there is little evidence that monetary contributions can directly ‘buy’ policy outcomes, it is nevertheless likely that these donors get some ‘return on their investment’. One potential return might take the form of increased attention to their problems. A second direct channel of money are interest groups which tend to be dominated by business and other professional groups that represent the interests of the wealthy rather than the poor (Gray et al. Reference Gray, Lowery, Fellowes and McAtee2004). While their direct impact might be limited (and difficult to prove), the role of interest groups as information providers enables them to be especially efficient in manoeuvring the priorities of business owners and managers into the political sphere (see, e.g., Bouwen Reference Bouwen2004). Less affluent citizens do not enjoy this advantage.

Last, socialization might be consequential. According to our argument above, social status shapes how we see the (political) world and thus influences which political issues we consider salient. The highly disproportionate share of the rich among professional politicians (Carnes Reference Carnes2013; Rosset 2016) might thus be another reason for the prioritization of affluent issues. As MPs have strong incentives to rely on their own experience and background when deciding on which topics to focus their attention (Butler Reference Butler2014), at the aggregate these priorities happen to be aligned with those of high‐status citizens.

In sum, all mechanisms point in the same direction: governments are disproportionately responsive to the priorities of high‐status citizens while neglecting what low‐status citizens consider important.

Data and methods

To test our hypotheses, we combine several datasets that include information about the priorities of high‐status and low‐status citizens, and about government activities in different policy domains in 10 European countries. The sample includes Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom. Even though the selection is constrained by data availability, we cover a variety of different regional (Scandinavia, Central Europe, Southern Europe) and institutional settings (multiparty systems and majoritarian democracies).

We present two types of analyses, a cross‐sectional longitudinal study with data between 2003 and 2016 and three single‐country studies with longer time series starting in the 1990s (United Kingdom, Spain and Germany). The time periods covered by each country in the cross‐section vary between 8 years (Belgium, the Netherlands, 2003–2009) and 15 years (Germany, 2002–2016) (depending on data available from the CAP project),Footnote 3 the single country time series data include a time period of 17, 20 and 27 years, respectively.

Dependent variable: governments’ legislative activities

Our dependent variable comes from the CAP and measures parliament and government activities in different policy areas.Footnote 4 More specifically, for each country/year we calculate the proportion of laws adopted in a specific policy area. Adopted legislation is an appropriate measure for responsiveness because it is the most consequential form of legislative action and affects the citizen's well‐being. Compared to bills, laws are also a more reliable measure because the definition of bills varies considerably among countries.Footnote 5

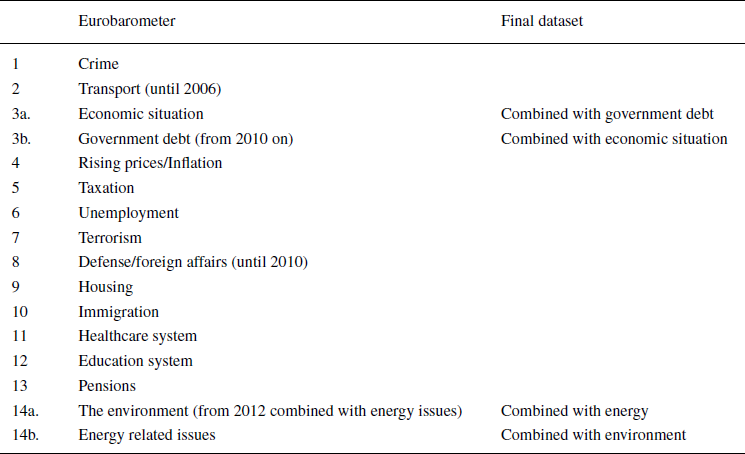

The CAP project assigns each law to one of 220 mutually exclusive minor topics in their cross‐national codebook.Footnote 6 We then matched this coding of legislative activity with the 14 issue categories in the survey data (Eurobarometer and country‐specific surveys, see Table 1), taking the latter as a starting point. Unlike the CAP data, which comprises of all government and parliament activities, questions on public priority in surveys entail only a small number of issue areas,Footnote 7 Each issue mentioned in these surveys can be addressed with several policy instruments. Therefore, we match each survey category with multiple topics in the CAP codebook. Three coders independently matched all 14 issues in the surveys with corresponding CAP minor topic codes. During this process, we paid particular attention to matching all laws, which can be interpreted as government responses to a particular problem, to the appropriate issue category. For example, the survey issue ‘unemployment’ includes not only laws coded in CAP's unemployment category but also laws concerning employment training, labour unions, low‐income assistance and fair labour standards. Coders’ disagreement on these matches were discussed and resolved in team meetings. Inter‐coder reliability for this particular coding process was close to 90 per cent.

Table 1. Most important issues: categories in Eurobarometer

Government activities without correspondence in the surveys (e.g., activities coded as ‘Intergovernmental Relations’ or ‘Gender Discrimination’) were dropped. Accordingly, our measure for the dependent variable computes the combined government/parliament output in one parliamentary year concerning the respective issues included in surveys’ ‘most important issue’ question. As a consequence of this re‐coding procedure, the combined policy output in all issue categories does not sum to 1, even though this measure is a proportion, strictly speaking. For more detailed information about the distribution of this variable, see Figure 1 in the Online Appendix.

Independent variable: political priorities of the rich and the poor

We capture priorities with aggregated answers to the ‘most important issue’ question as this is the only cross‐nationally available information. While there has been some debate on the interpretation of this measure (e.g., Wlezien Reference Wlezien2005; but see Jennings & Wlezien Reference Jennings and Wlezien2011), it remains the most accepted and widely used method to capture issue salience and problem pressure (see, e.g., Bevan & Jennings Reference Bevan and Jennings2014; Flavin & Franko Reference Flavin and Franko2017 or Jones & Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2004). We measure public priorities by aggregating the ‘Most important issue’ question in the Eurobarometer (cross‐section analysis), and in the three country surveys (time series analysis).Footnote 8

The Eurobarometer includes a fixed selection of issue categories for the respondents to choose from (varying only slightly during the 13‐year period). Table 1 shows how we used the pre‐set categories in the final dataset. For purposes of comparability, we have collapsed the open‐ended questions in Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom into the same categories.

Since surveys are fielded several times a year, we aggregate the most important issue question for each survey first, then taking the average per year (and country). Table 1 in the Online Appendix gives an overview of the 30 Eurobarometer surveys included. More specifically, we take the share of respondents who considered the respective issue important. For example, ‘housing’ is enumerated as 0.3 if 30 per cent of respondents thought housing was the most important issue in a given year (and country).

The importance that citizens assign to different issues varies considerably over time. Figure 2 in the Online Appendix depicts the varying saliency of immigration, the economic situation and unemployment in Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom. Even among these highly salient issues, the share of citizens who find the respective issues important varies by up to 60 percentage points. For instance, while less than 10 per cent of citizens considered immigration to be the most salient topic in Germany in the mid‐1990s, its share peaked at over 80 per cent in the summer of 2015.

For our analysis, we disaggregate responses by group, distinguishing between three social status groups: high‐status, middle‐status and low‐status citizens. Because income measures are notoriously biased in surveys and suffer from many missing values, and therefore not included anymore in the Eurobarometer surveys, we approximate status groups by occupation. Table 2 in the Online Appendix shows how we recoded the occupation groups in the Eurobarometer into three social status groups. For each of the 14 issues, we then calculated the share of respondents that thought the issue was most important per status group, year and country. The same procedure was applied to the time‐series data from the three individual countries, United Kingdom, Spain and Germany (see Tables 3–5 in the Online Appendix).Footnote 9

To identify the priority gap, we use two different measures of priorities. They follow a slightly different logic: the first simply counts the share of respondents within a social status group who thought the issue was important, as described above. This measure accounts for the intensity of priorities of different groups. We identify the priority gap by subtracting the share of low‐status citizens who mentioned an issue from the share of those with high status who considered the issue the most important at the time. Further, we calculate the priority gap between middle‐status and low‐status citizens, as well as between high‐status and middle‐status citizens.

The second measure reflects the ranking of the issues (1 = most important, 14 = least important). This measure gives information about the relative importance, but not the intensity of priorities. In some situations, one issue is clearly the most salient. In Germany in 2005, for example, unemployment was considered the most important issue by 81 per cent of high‐status citizens and 84 per cent of those with low social status. In other situations, several issues share similar importance among the groups. For example, in 2007 the environment was the most important issue for 32 per cent of high‐status Belgians (14 per cent of low status), while pensions were mentioned by 29 per cent (18 per cent) and unemployment by 30 per cent (37 per cent). We calculate the priority gap in ranking by subtracting the rank of an issue for high‐status people from the ranking among low‐status people (as well as for the other group comparisons). Low‐ and high‐status groups might differ in the intensity of priorities (share of responses), but consider the same issues as most important in absolute terms. Identifying the priority gap by using the difference in ranking, we take this possibility into account.

We control for ideological position of the government to make sure our results are not driven by ideological leanings of the government parties. The measure is computed as the average share of left‐right government position (cabinet parties) in one parliamentary year (August–July) weighted by seat share in parliament. Data comes from the ParlGov database (Doring & Manow Reference Doring and Manow2018), ideological position is based on expert surveys (codebook: http://www.parlgov.org/documentation/codebook/).

Estimation

Model specification. In order to take into account that legislative activity takes time, we combine citizens’ priorities and government output with a time lag. Specifically, while public opinion data are aggregated by year, the dependent variable – share of laws – is computed for each legislative year, beginning in August. In other words, we compare the public's issue priorities in a specific year with the legislative output beginning after the summer break until the next summer. Since our dependent variable is the share of laws in a given year, we ran fractional logit models (Papke & Wooldridge Reference Papke and Wooldridge1996) with fixed effects for countries and years, first using the Eurobarometer data which include 10 countries over a 13‐year time span. Second, we apply the same modelling strategy to study three of the countries over a longer time span.Footnote 10

Threats and challenges. At least two potential sources of bias might distort our results. First, common shocks across all countries as well as unobserved features for specific countries might affect legislative priorities. For example, deepening European integration might affect particular policy fields in all countries (although Beyer (Reference Beyer2018) presents evidence that assimilation varies across space and time). We address this omitted variable bias by using country and time fixed effects. Legislative activity might not only respond to citizen priorities of the rich and the poor, but also influence them as well. The priority gap between rich and poor may change with new legislation. Hence, endogeneity is a second source of bias. Because no clear instrument exists in the current literature on representation and responsiveness, we mitigate this threat by carefully constructing an appropriate lag structure. For all countries in our sample, we obtained information about how much time passes between the introduction and passage of legislation. Based on that information, we lagged citizen priorities so that governments are still able to respond to citizen demands within a legislative session but also ensuring that citizen priorities antecede legislation. Practically, we compare the public's issue priorities in a specific year with the legislative output beginning after the summer break until the next summer. This temporal structure ensures that government action cannot logically cause citizens’ priorities.

Results

Issue priorities of low‐ and high‐status citizens in Europe

In a first step, we investigate and compare the priorities of citizens with different social status. If there is no priority gap, responsiveness cannot be unequal by definition – that is, governments will or will not be responsive to society as a whole. We expect priority differences between social status groups mainly based on material self‐interest resulting in different expectations about the role of the state in society. In addition, different life experiences, social contexts – such as living in a poor neighbourhood – and experiences shared via social networks may influence a person's view on what is important in a specific country at a given time.

Figure 1 shows the differences in priorities between the high‐status and low‐status groups (see Figures 3 and 4 in the Online Appendix for the difference between middle‐status and low‐status groups and between high‐status and middle‐status groups). We first calculated the share of mentions among the high‐status group minus the share of mentions among the low‐status group in each country and year. Numbers below zero indicate that the issue is more important for low‐income citizens, and positive numbers indicate higher importance for wealthier citizens. Figure 1 plots the distribution of the priority gap for each issue. It illustrates, first of all, the differences with regard to crime, unemployment, inflation and immigration: these issues are more pressing for lower‐status groups. On the other side, the economic situation, education, the environment and health issues are more important for citizens with high social status, such as managers and wealthy professionals. Given that each topic has on average around 15 per cent chance to be mentioned at any given time, these differences in the range of 5–15 percentage points are substantial and sizable.

Figure 1. Issue priority gap between high‐status and low‐status groups

As discussed above, there are several ways to calculate citizens’ priorities. Besides the share of respondents who mention a specific issue, we can also look at the ranking of priorities, which are the issues that receive the highest share, second highest, etc. of mentions. Comparing the ranking of priorities reveals a preference overlap in many cases, but there are also important differences (see Figure 5 in the Online Appendix). Unemployment is most often the number one issue among the low‐status group, and the economy ranks highest among people with high social status. Crime is often among the top three issues for lower status citizens, while health ranks among the top three much more frequently for high‐status citizens. It is striking that issues like education and the environment are almost never the top priorities for low‐status citizens.

Overall, the comparison of priorities reveals occasional agreements between the high‐ and low‐status groups, but also important and sizable priority gaps, indicating differences in material interest and life experiences. In addition, there is substantive variation on the priority gap over time (see the Online Appendix for more details). We explore, in the next step, how governments and parliaments respond to differing needs and expectations.

Unequal responsiveness?

According to the ‘responsible party model’, we would expect governments and parliaments to follow their voter's concerns and focus their policy activities on the areas that are currently most salient. In reality, a large part of government activity is of course determined by other factors – an agenda that was decided in a coalition agreement at the beginning of the legislative period, for example, or supranational politics. When comparing policy making with the citizen's priorities, we can therefore only consider a subset of laws adopted, namely in those policy areas that correspond to the public's priority categories. Figure 2 plots the share of laws concerning these issues. Ignoring unequal group priorities for now, government activities appear fairly congruent with citizen demands overall. Most laws adopted concern the economy and crime‐related issues; moreover, governments and parliaments decided on laws concerning energy/environmental issues, transport, taxes and health care. On the other hand, only a low number of laws adopted by European governments between 2002 and 2015 directly concerned terrorism, pension or inflation.

Figure 2. Share of laws in different issue areas (per year)

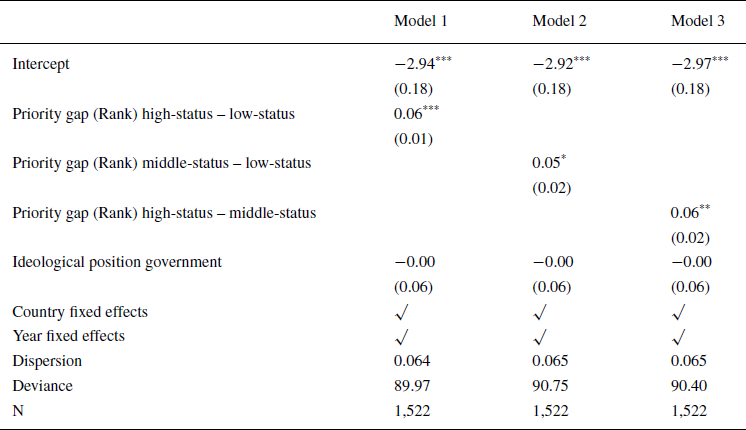

Do governments respond to citizens’ priorities in politics and if so, are some groups better represented than others? Table 2 shows the results of our statistical analyses. The dependent variable is the share of laws in a specific policy area (per year/country). The independent variables are the priorities of the three status groups, as well as the difference in priorities. Since the dependent variable is a proportion, we fit fractional (quasi‐binomial) logit models. Further, we include fixed effects for years and countries in the models.Footnote 11 The findings indicate that more laws are adopted with regard to issues that high‐status people find important (Model 1). In contrast, the priorities of the low‐status citizens are negatively related to government output, when controlling for priorities of high‐status citizens.

Table 2. Responsiveness to citizen's priorities (fractional logit; DV: share of laws per year)

*** p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

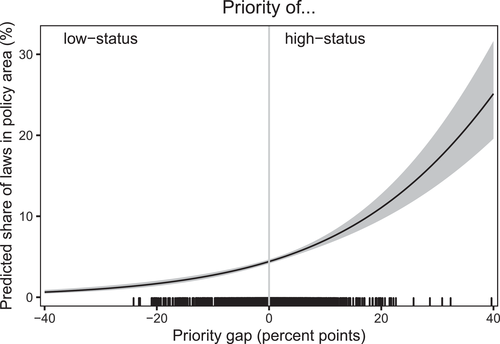

Corroborating this baseline result, we find that the priorities of high‐status citizens matter more when they differ from those of low‐status citizens (Model 4): the larger the priority gap on a specific issue, the stronger the reaction of political elites. The predicted values from Model 4 are shown in Figure 3: if both groups have the same priorities (i.e., there is no priority gap), about 5 per cent of laws are adopted on a specific policy topic. If an issue becomes more important for less affluent citizens, responsiveness decreases. This assertion is indicated by the fact that the predicted values on the left side of the graph are below the estimate of the zero priority gap.Footnote 12 If an issue becomes more important for those with higher social status, indeed, government responds with considerable legislative activity in this policy area. For example, if an issue is 20 percentage points more important to high‐status citizens than to the less well‐off, there is an estimated 15 per cent point share of legislation. In other words, under this scenario, government produces three times more legislation compared to a situation where citizens hold the same priorities. We find a similar result for the priority gap between middle‐status and low‐status citizens, and between those with high‐ and middle‐status. Our findings hold also when excluding one issue at the time, please see estimates in the Online Appendix (Figure 7).

Figure 3. Predicted values: share of laws depending on the priority gap (Model 4)

Table 3 reports the findings for our second measure of priority gap: the rank difference. Again, the results show that governments are more responsive to higher status groups, when a priority gap exists. The larger the priority gap, the higher the share of laws adopted, if an issue is more important for higher status groups and the lower the share if it is mainly important for those with low social status, such as manual workers. Figure 4 visualizes the increasing legislative responsiveness as one moves from priorities of the low‐status citizens to the affluent.

Table 3. Responsiveness to citizen's priorities: rank (fractional logit; DV: share of laws per year)

*** p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Figure 4. Predicted values: share of laws depending on rank difference (Model 1)

Overall, these findings regarding citizens’ priorities corroborate what previous studies have found with regard to political preferences. There are instances where citizens with higher and with lower social status want the same in politics, but once they disagree on issues, government listens more closely to those with higher status and more income. Government enacts laws for the priorities of the rich and less so for the poor. These results hold when controlling for government ideology. According to our findings, unequal responsiveness is not contingent on specific compositions of cabinet.Footnote 13 Governments of all ideological stripes attend to the problems of high‐status citizens.

Unequal responsiveness in Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom

As a final test, we focus on patterns of responsiveness in three selected countries where longer time series are available. The goal is to ensure that our results are not driven by pooling across many countries, but that patterns of unequal responsiveness are observable within single countries. For this purpose, we selected three major democracies from the above sample for which we had access to detailed, regular, longitudinal information on issue priorities and occupation – Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom. The countries represent three extremes regarding voter–government linkages. In addition, the saliency of different topics varies considerably between these cases (see Figure 2 in the Online Appendix).

The three countries are well suited to study responsiveness. The United Kingdom is a prime example of strong accountability of governments to voters; responsibility is clearly identifiable and voters punish governments for bad performance (Powell & Whitten Reference Powell and Whitten1993). By contrast, responsibility for policy making is lower in Spain due to its proportional system and the resulting lower clarity of responsibility, its high level of corruption and higher level of decentralization (Leon Reference Leon2011; Hobolt et al. Reference Hobolt, Tilley and Banducci2013). Germany is sometimes even seen as a consensus democracy (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999) and provides for the weakest level of direct accountability and clarity of responsibility due to its coalition governments and the strong role of parties. Soroka and Wlezien (Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010) would therefore expect the lowest levels of responsiveness in a country like Germany. Furthermore, the countries differ regarding their exposure to economic crises and the salience of economic inequality. Economic inequality is particularly high in the United Kingdom and lowest in Germany (OECD 2016); Spain was heavily affected by the financial crisis of 2008, and economic inequality became increasingly salient in this context. Comparing these three countries thus enables us to test for unequal responsiveness in various contexts.

Issue priorities of high‐ and low‐status citizens in Spain the United Kingdom and Germany

Across the three countries, clear gaps in priorities persist. The left panel of Figure 5 shows the priority gap between high‐ and low‐status citizens in the United Kingdom, Germany and Spain respectively. The emerging pattern corresponds to the comparative findings presented in Figure 1. Unemployment, and immigration are the most salient issues for low‐status citizens, whereas the economic situation, the environment and education are among the most prevalent issues for the high‐status group. While issue priorities are similar between the two groups on some topics, we discover important differences between low‐ and high‐status citizens indicating potential for unequal responsiveness. The right panel in Figure 1 presents the corresponding share of adopted laws. As for most other countries, Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom enact few laws on pensions and unemployment per se; they spend a large amount of resources on legislating on the economy and crime. In addition, energy/environment attracts considerable legislative attention.

Figure 5. Issue priority gap and share of laws in the United Kingdom (top), Germany (middle) and Spain (bottom)

Unequal responsiveness in Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom

Our three ‘case studies’ corroborate the findings of the cross‐country analysis above. The estimated effect of the priority gap on legislative activity is displayed in Figure 6 (see Tables 6–8 in the Online Appendix for regression results). As the graphs illuminate, the more important an issue is for high‐status citizens in comparison to low‐status citizens the higher the legislative activity in a particular policy domain. This finding is true regardless of the economic and institutional context and holds across all three countries. We identify the same pattern if we compare middle‐ and low‐status citizens or high‐ and middle‐status citizens, respectively. The only exception is Spain where the estimated effect does not distinguish whether governments are more responsive to middle‐status than low‐status groups. At the same time, responsiveness to high‐status citizens in Spain is higher than those to middle‐status citizens.

Figure 6. Predicted values: share of laws depending on the priority gap

The results stem from three different samples and are thus not directly comparable, yet the estimated effects are remarkable. We uncover evidence for unequal responsiveness in the highly unequal United Kingdom where politicians have high incentives to be accountable, as well as in Germany's near consensus democracy with rather low economic inequality and lower incentives to be responsive. In Spain where economic inequality became increasingly salient in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008, the same effect prevails. In substantial terms, if high‐ and low‐status citizens do not differ with regard to their issue priorities, about 5 per cent of laws are produced in a given policy area across all three countries. By contrast, if high‐status citizens find an issue 10 percentage points more important than those of low status, government legislates about 10 per cent of laws in this specific policy area in the United Kingdom and Spain, and even 20 per cent in Germany. It may seem surprising at first sight that representation is most biased towards higher status citizens in Germany. Yet, the finding is in line with recent evidence by Elsässer et al. (Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2017) on unequal representation.

The estimates also speak to the pessimistic view of Soroka and Wlezien (Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010) who predict little responsiveness in parliamentary and federal systems. Complex political institutions which provide for weak accountability and unclear responsibility may inhibit voters from punishing unresponsive governments. High‐status citizens appear to be better equipped than low‐status citizens to ensure that their priorities are represented under these conditions.

In sum, the individual analyses of these three vastly different countries offer additional assurance to our cross‐country analysis. While low‐ and high‐status citizens agree on many issues, political elites respond more strongly to the priorities of the better off if a priority gap exists. Unequal responsiveness persists across and within European democracies.

Conclusion

In this study, we observe a rarely appreciated aspect of unequal representation: inequalities in the attention that government officials devote to the salient topics of rich and poor. Priorities of social status groups overlap at times but regularly differences in their priorities exist. The less affluent, for example, devote more attention to unemployment while the more affluent think of education as a highly salient topic. When a priority gap materializes, governments tend to side with the rich and prioritize their salient issues in policy making. This finding holds not only for economic concerns but across the whole range of issues.

These findings are important in three respects: First, they update our view of the representational process, especially regarding the equality of treatment promise. Unequal representation is not confined to preferences but takes place at this early stage of policy making as well. This concern justifies our focus on priorities and at the same time begs for more research probing other aspects of representation that potentially bias against low‐income citizens. The uncovered disconnect at the early stage of the policy making process – the unequal treatment of the priorities of rich and poor – has potentially large consequences for the whole representational chain. If some segments of society are selectively excluded from expressing their preferences and having their problems solved, representational bias in governing are hard to remedy.

Second, the 10 countries included in the analysis right now cover a large range of institutional and regional differences. In combination with the three case studies, which show how consistent our findings are across contexts, our comparative tests allow us to draw some conclusions about the prevalence of context effects. As we argued earlier, the countries differ in their degree of accountability as well as in their electoral systems and type of government. Turnout rates vary also considerably across the three countries (Gallego Reference Gallego2014). These differences are noteworthy as one of the mechanisms we propose emphasizes unequal turnout as an explanation for why the less affluent enjoy little influence in politics. Given that lower turnout rates offer more potential for unequal participation, our findings suggest that turnout does not constitute the main mechanism driving unequal priority representation. Even with comparative evidence, assessing and separating the two other mechanisms – influence of money and socialization of elites – is a serious challenge. A worthy challenge that requires more targeted research in order to develop better leverage on the mechanisms of unequal representation.

Finally, these findings call for more research looking at both dimensions of representation – priorities and preferences – simultaneously. It seems plausible that the consequences of unequal agenda representation are especially harsh if the preferences of the less affluent are not taken into account on the same topics. Consequently, disadvantages in priorities and preferences overlap and potentially accumulate. For the time being, it seems reasonable to assume that priorities are turned into policies to the disadvantage of less affluent citizens – given the large body of work documenting unequal preference representation to the detriment of the less affluent. In addition, recent evidence suggests that inequality in preference representation is visible on diverse issues such as European integration or social lifestyle (Rosset & Stecker Reference Rosset and Stecker2019) and is thus not restricted to the left‐right dimension as shown by previous work (Bartels Reference Bartels2008; Giger et al. Reference Giger, Rosset and Bernauer2012).

Issue priorities and policy preferences are two independent concepts. For questions of unequal responsiveness, this distinction implies that citizens can be disadvantaged in two ways. First government does not tackle their most salient issues, and second policy making does not reflect their preferences. Unemployment exemplifies this distinction. On this issue, our study discovers little legislative action on behalf of the poor. The topic clearly is more salient among the poor than the rich, but very few policies are enacted in this policy domain. At the same time, if we see government action, it is predominantly in the form of cutbacks and retrenchment as an extant literature on social policy reforms documents (see, e.g., Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi, Hausermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015). These reforms again go against the interests of the poor. A pessimistic conclusion, therefore, might be that the situation is even worse than what is shown in our paper: little responsiveness on issues and little representation on policy.

Unequal responsiveness towards the priorities of the rich and not the poor raises the potential for increased societal discontent and the erosion of democratic legitimacy. Based on the presented research, we offer potential policy recommendation for abating divergent levels of responsiveness among social groups. Most importantly, the poor need to be well‐represented in the political process and have lobbying access. One potential solution here is to rely on the traditional representative of the poor – labour unions. Labour unions, as Becher and Stegmüller (Reference Becher and Stegmueller2020) have shown, can engage in political action that lies beyond the benefits of their members. Finally, if politicians increasingly share similar upper class backgrounds, political parties need to be aware of this shortcoming and change recruiting mechanisms. The introduction of gender quotas makes clear that strong institutional rules can be employed in this area, and that they make a difference in outcomes (Clayton & Zetterberg Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2018). All in all, to paraphrase Schattschneider, reducing unequal responsiveness requires that the heavenly chorus sings with diverse accents.

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (Ambizione Grant No. Nr.: PZ00P1_174067 / 1, PI Denise Traber)‐and the ‘Inequality in the mind’ project (100017_178980, PI Nathalie Giger). Nathalie Giger also acknowledges the support of the Unequal Democracies Program at the University of Geneva (ERC Advance Grant no. 741538, PI: Jonas Pontusson). Christian Breunig and Miriam Hänni were supported by the German Science Foundation Grant 414/16 – Conditional Responsiveness.

Earlier versions of this article have been presented at various conferences (annual meetings of EPSA, APSA, DVPW and at the CAP meeting in 2018) and workshops (ERC Unequal democracies workshop in 2019, the UCD connected lab in 2019 and departmental seminars at the Humboldt University in 2019, and at the University of Basel in 2020). We thank Lucas Leemann, Johan Elkink, Kris‐Stella Trump, Hanna Schwander, Derek Epp, Armin Schäfer, Christopher Wlezien and three anonymous reviewers for very helpful comments.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary material

Figure 1: Distribution of dependent variable

Table 1: Eurobarometer studies included

Figure 2: Development of Priorities over Time

Table 2: Eurobarometer, occupational categories: coding and validation with subjective class (percentage of respondents in two classes combined per occupation category)

Table 3: Occupation categories the United Kingdom

Table 4: Occupation categories in Spain; coding and validation with subjective class

Table 5: Occupation categories in Germany

Figure 3: Issue priority gap between middle‐status and low‐status groups

Figure 4: Issue priority gap between high‐status and middle‐status groups

Figure 5: Most important issues, ranking

Table 6: Responsiveness to citizens' priorities in the UK

Table 7: Responsiveness to citizens' priorities in Germany

Table 8: Responsiveness to citizens' priorities in Spain

Figure 6: Predicted values: share of laws depending on the priority gap for bills, laws, and unsuccessful bills in Germany

Figure 7: Robustness Tests

Table 9: Responsiveness to citizen's priorities: Government ideology (Fractional logit; DV: share of laws per year)