Introduction

Europe has recently been haunted by social crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and ongoing refugee/migration crises. These social crises are not neutral to volunteering and the organizations coordinating it. The patterns of volunteer engagement were changing, with an emergent group of spontaneous volunteers characteristic of crisis times (Yang, Reference Yang2021). One of the reasons behind this might be the social support mobilization process that occurs in response to a crisis (Kaniasty, Reference Kaniasty2020). Facing the challenges associated with witnessing others’ suffering results in a higher willingness to provide support. During the COVID-19 pandemic, online-based self-help groups and other grassroots initiatives (Nowakowska, Reference Nowakowska2023) were examples of such spontaneous mobilization, encompassing not only those previously active in volunteering. Due to the need to reconnect with others, people engaging in them could rebuild the sense of being needed and active (Kulik, Reference Kulik2022). On the other hand, a pandemic could have hindered volunteering activity (especially in the face-to-face mode) given the health-related anxieties, uncertainty, and stresses with work-life balance and family relationships, which were challenging to navigate during home office (Kulik, Reference Kulik2022).

Refugee crises can also result in different engagement patterns than in non-critical times, especially when there are emergencies connected to the situation. As the abovementioned social support mobilization theory (Kaniasty, Reference Kaniasty2020) states, emergencies may encourage compassion-driven volunteers to act for the well-being of those in need. Babula and Muschert (Reference Babula and Muschert2023) assert that social needs primarily drive volunteers, and a sense of belonging could inform more effective recruitment and retention strategies, underlining the importance of fostering a supportive and inclusive community for volunteers. However, after the crisis loosens, deterioration of the social support phase (Kaniasty, Reference Kaniasty2020) appears, and the energy might wear off. That is why some spontaneous volunteers remain only episodic and cease their activities immediately after the event that triggered their decision to join finishes (Cnaan et al., Reference Cnaan, Meijs, Brudney, Hersberger-Langloh, Okada and Abu-Rumman2022).

Social crises may encourage the popularity of temporary engagement in volunteering—also among those who have not tried it before and do not have the experience to build upon it. However, what does this mean for the organizations? Are episodic volunteers crucial to performing their activities, or is it linked to an inevitable loss of long-term volunteers?

Volunteer retention strategies may prove crucial in securing volunteer support (Hopkins & Dowell, Reference Hopkins and Dowell2022). However, only some organizations have a defined retention strategy, which can make the retention-directed activities more chaotic or less effective. It could be especially threatening to the continuity of volunteer operations during social crises.

Furthermore, informal groups may act quickly and precisely during crises to address the community's needs (Bertogg & Koos, Reference Bertogg and Koos2021), gathering the organizations’ resources and energy to be devoted to formal volunteering. Moreover, uncertain times can result in a decrease in trust toward formalized institutions in general, challenging the leaders of organizations to take action to sustain or rebuild them (Ahern & Loh, Reference Ahern and Loh2021). It can have a consequence in redirecting attention to informal groups by the volunteers and problems with recruiting new volunteers by formal organizations.

Having identified these problems regarding the organization's activities, we intend to determine how volunteer coordinators view these matters in the current study. Coordinators are underresearched in the volunteering literature despite being the leaders of the volunteer process, crucial to successful formal volunteering processes, and the first to identify the potential risks associated with social crises.

Whether people engage in voluntary activities could be a question of their motivation (Pozzi et al., Reference Pozzi, Passini, Chayinska, Morselli, Ellena, Wlodarczyk and Pistoni2022; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017). For example, basic psychological needs theory (BPNT) suggests that motivation associated with volunteering is contingent upon the degree to which it satisfies three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017). Autonomy refers to feeling a sense of agency and volition regarding volunteering. Competence is the need to feel mastery over the means to perform that activity. Relatedness is the need to feel meaningful connections to others through that activity. When those needs are satisfied through volunteering, one experiences a high degree of motivation to engage in that activity and achieves a sense of well-being as a result. BPNT can help create better experiences for volunteers and enhance their well-being, and therefore, contribute to understanding why they want to contribute to volunteering during regular or crisis times.

On the other hand, volunteerism could be understood as a kind of social exchange. Social exchange theory (SET) suggests that individuals engage in social transactions with the expectancy that the benefits will outweigh the costs (Drollinger, Reference Drollinger2010). Individuals wish to maximize rewards (both material and non-material) and minimize costs in their activities (Lowenstein et al., Reference Lowenstein, Katz and Gur-Yaish2007). Accordingly, social exchange theory suggests that in the context of their personal lives, volunteers might experience greater self-esteem and mastery when they receive more than they give (over-benefiting).

Current study

Based on the identification of problems faced by formal volunteering organizations, we wanted to find out how volunteer coordinators perceive (1) the patterns of volunteering engagement (long-term) versus episodic, in regular times and during social crises; (2) the processes of retaining volunteers during crises; (3) how they see the trust of the community toward various types of organizations during social crises; (4) the role of informal support groups in relation to the tasks of their organization. We intended to interpret the patterns of answers through the lenses of theoretical frameworks provided by BPNT and SET. In order to achieve this goal, between June 2023 and October 2023 (a post-pandemic period and at the same time, a year after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine), we conducted a study in two European countries differently affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and refugee crises: Poland and Italy. Some answers could be explained by looking at the volunteers' costs and benefits (social exchange theory) or the satisfaction or frustration of basic psychological needs (basic psychological needs theory).

In the case of the pandemic, Poland and Italy experienced similar restrictions (lockdowns, sanitary regime; Lorettu et al., Reference Lorettu, Mastrangelo, Stepien, Grabowski, Meloni, Piu, Michalski, Waszak, Bellizzi and Cegolon2021); however, they were affected to a different scale. Italy was considered a “source” of the first COVID-19 wave in Europe, resulting in a vast number of people being infected and dying from the disease (Senni, Reference Senni2020).

Regarding the refugee crisis, Poland has a relatively short story of accepting refugees/migrants. Despite the strong social support mobilization toward Ukrainians in 2022 (Nowakowska, Reference Nowakowska2024), no such large-scale support was provided by individuals and organizations to migrants or refugees from the Middle East or Africa during the 2015 (Goździak & Main, Reference Goździak and Main2020) and 2021 (Halemba, Reference Halemba2022) crises. On the contrary, Italy is a country with a long history of dealing with migrants and refugees, and their income is constant rather than episodic (Ambrosini, Reference Ambrosini2013), as it is for Poland.

Based on these facts and acknowledging the similarities and differences between the countries experiencing the recent social crises, we decided to conduct our study in the context of these territories. Given our study's pioneering and exploratory nature and the constrained target group of participants (volunteer coordinators), which does not allow for large sampling, we used a qualitative survey with multiple-choice and open-ended questions.

Through our analysis, we want to understand the role of formal volunteering during crises and the organization's motivations and barriers to cooperating with long-term and episodic volunteers and informal groups in uncertain times.

Method

Participants

Polish sample

Twenty-eight volunteer coordinators from Poland took part, 25 females (89.3%) and 3 males (10.7%), aged 25–61 (M = 39.82; SD = 9.17). Among the participants, there were 2 residents of a village (7.1%), 2 residents of a town with less than 100,000 inhabitants (7.1%), 9 residents of a town with 100,001–499,999 inhabitants (32.1%), and 15 residents of a city with over 500,000 inhabitants (53.6%). Two participants had high school education (7.1%), 3 (10.7%) Bachelor’s degree, 22 (78.6%) Master’s degree, and 1 (3.6%) a Ph.D. degree. The coordinators worked on their positions from 4 to 16 years (M = 7.29; SD = 3.40). The focus of the work of organizations represented by the coordinators was as follows (multiple answers were allowed): children—18 people (64.3%), seniors—18 people (64.3%), people with disabilities—14 (50.0%), people with chronic illnesses including cancer—5 people (17.9%), immigrants and/or refugees—11 people (39.3%), sexual minorities—2 people (7.1%), culture and art—9 people (32.1%), animals—7 people (25.0%), natural environment—5 people (17.9%), education—13 people (46.4%), religious engagement—1 person (3.6%). Twenty (71.4%) organizations engaged more long-term than episodic volunteers, and 8 (28.5%) engaged more episodic than long-term volunteers. Twenty organizations represented by the coordinators (71.4%) changed their field of activity due to a pandemic, and 14 (50.0%) changed their field of activity due to a refugee crisis.

Italian sample

Twenty-seven volunteer coordinators from Italy took part, 17 females (63.0%) and 10 males (37.0%), aged 30–75 (M = 56.22; SD = 13.27). Among the participants, there were 5 residents of a village (18.5%), 3 residents of a town with less than 100,000 inhabitants (11.1%), 8 residents of a town with 100,001–499,999 inhabitants (29.6%), and 11 residents of a city with over 500,000 inhabitants (40.7%). One participant (3.7%) had primary or secondary school education, 1 (3.7%) participant finished professional institute, 5 (18.5%) high school, 7 (25.9%) had Bachelor’s degree, 13 (48.1%) Master’s degree or had higher academic title. The coordinators worked in their positions from 4 to 40 years (M = 13.44; SD = 10.97). The focus of the work of organizations represented by the coordinators was as follows (multiple answers were allowed): children—14 people (51.9%), seniors—14 people (51.9%), people with disabilities—10 (37.0%), people with chronic illnesses including cancer—6 people (22.2%), immigrants and/or refugees—15 people (55.6%), sexual minorities—4 people (14.8%), culture and art—4 people (14.8%), animals—3 people (11.1%), natural environment—3 people (11.1%), education—5 people (18.5%), law and democracy support—3 people (11.1%), political engagement—1 person (3.7%), religious engagement—2 people (7.4%). Twenty-three (85.2%) organizations engaged more long-term than episodic volunteers, and 4 (14.8%) engaged more episodic than long-term volunteers. Fifteen organizations represented by the coordinators (55.6%) changed the field of their activity due to a pandemic, and 3 (11.1%) changed the field of their activity due to a refugee crisis.

Procedure

We recruited volunteer coordinators from across the countries. The study took place between June and October 2023. Only coordinators who started their work in 2019 or earlier were invited (due to the need to recruit people who knew about the functioning of their organization before the COVID-19 pandemic). We directly emailed regional centers of volunteering and formal organizations (we included both public and non-governmental entities) to recruit respondents. The purpose of the study was described as “the exploration of how volunteer coordinators perceive the engagement of volunteers before the COVID-19 pandemic, during it, and now, as well as how they assess the engagement of long-term and episodic volunteers”. The study was anonymous, and participants were not remunerated for participating. Before conducting the study, we obtained approval from The Maria Grzegorzewska University Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided informed consent and were assured that their information would be treated in strict accordance with data protection legislation.

Measures

We used a qualitative survey with multiple-choice and open-ended questions to answer our research questions. The wide-angle lens of qualitative research allows for capturing various perspectives, experiences, and sense-making necessary to provide thematic richness (Toerien & Wilkinson, Reference Toerien and Wilkinson2004). The open-ended questions were planned to be analyzed using the thematic analysis approach (Clarke & Braun, Reference Clarke and Braun2017). Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analyzing, and interpreting themes (meaning) within qualitative data. It can be applied within various theoretical contexts using diverse research tools (including a qualitative survey). This approach has been successfully used in recent volunteering research (McLeish & Redshaw, Reference McLeish and Redshaw2021; Stølen, Reference Stølen2022).

With the ability to answer open-ended questions in a qualitative survey, participants have more control over how they define themselves and their opinions, resulting in richer responses than in the case of multiple-choice questions (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Clarke, Boulton, Davey and McEvoy2021). Furthermore, online qualitative surveys allow for the recruitment of a more diverse sample by providing access to participants who would not normally be sampled by interview methods (e.g., due to geographic or time constraints; Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013). Apparent limitations of this method include the potential for shorter and less nuanced responses than with interview data. Nevertheless, Braun et al. (Reference Braun, Clarke, Boulton, Davey and McEvoy2021) argue that data quality does not suffer dramatically when qualitative surveys are used.

For the multiple-choice questions, we did not form any scales. Each was taken separately for frequency analysis illustrative to the thematic analysis of open-ended questions. For sample description purposes, the first questions concerned the demographic data about the participants and the data about their organizations (without giving their names to preserve anonymity). We then posed a series of questions regarding how volunteers engage during crises and how coordinators assess the role of long-term and episodic volunteers in pursuing their organization's goals. Given the pioneering nature of the project, the survey questions were originally prepared by the first and last author of the paper in relation to the study goals. The complete questionnaire and quotations are available in Open Science Framework https://osf.io/g2kas/.

Analytic strategy

We present the frequency analysis results in data from multiple-choice questions and the frequency of themes that emerged from the qualitative analysis of the open-ended questions. For open questions, we employed the thematic analysis principles (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun and Clarke2019). We performed three-level coding: the first focused on highlighting keywords to capture the sense of particular responses. The second coding concentrated on grouping the keywords into themes. The third coding regarded forming higher-order themes to be presented in the manuscript. Three coders were involved for the Polish sample and three other coders for the Italian sample. In both cases, coders were native speakers of the language of the surveys. Each coder performed the coding process separately. Krippendorff’s α coefficients (calculated using a macro for IBM SPSS; Hayes & Krippendorff, Reference Hayes and Krippendorff2007) for each of the questions exceeded 0.83 for the Polish coders and 0.84 for the Italian coders before reaching a consensus about the codes to be finally assigned. Following the recommendations of thematic analysis methodologists, we kept personal notes of all coders (Vaismoradi et al., Reference Vaismoradi, Turunen and Bondas2013). In the discussion phase, we used all of them to reach a complete consensus among coders. In case of persistent disagreement, our strategy was to assign two or more codes to specific quotations. Notably, coding was performed independently for each of the samples; we aimed to compare results at the level of interpretation of results, not their presentation.

Results

This section presents the frequencies of responses to the multiple-choice questions and the results of the qualitative analysis, organizing them into Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. For the qualitative analysis of open questions, we present the higher-order themes for each of the topics of interest or both samples separately, with comments clarifying the contents of the themes. Given that multiple arguments could have been provided in each open-question response, each quotation could have been coded with multiple themes. For clarity, in the analysis below, we omitted the unclear, null, and “I do not know" answers." All percentages in brackets refer to the whole number of participants for a particular sample.

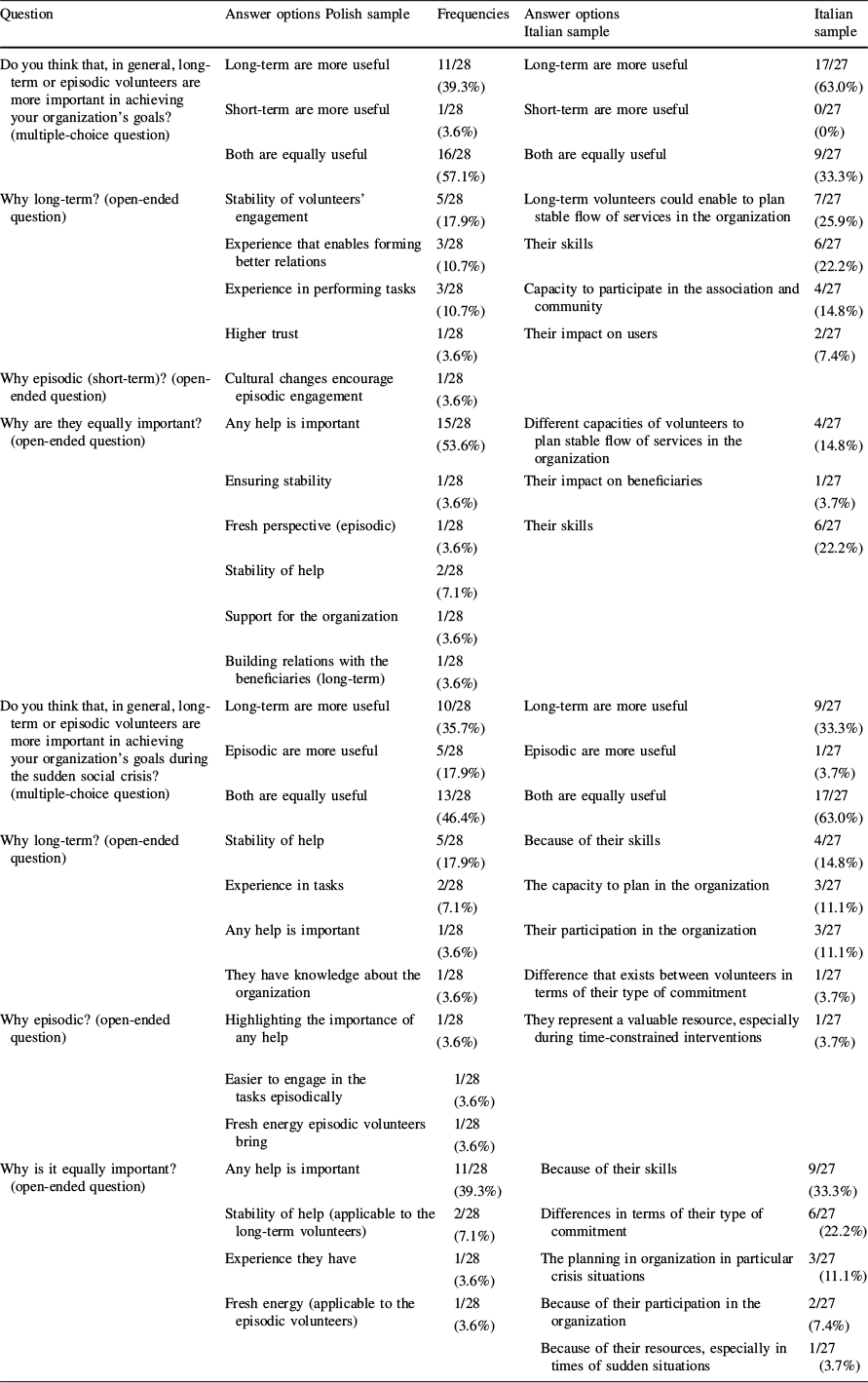

Table 1 Volunteer coordinators’ opinions about the engagement of long-term and episodic volunteers in the organization

Question |

Answer options Polish sample |

Frequencies |

Answer options Italian sample |

Italian sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Do you think that, in general, long-term or episodic volunteers are more important in achieving your organization's goals? (multiple-choice question) |

Long-term are more useful |

11/28 (39.3%) |

Long-term are more useful |

17/27 (63.0%) |

Short-term are more useful |

1/28 (3.6%) |

Short-term are more useful |

0/27 (0%) |

|

Both are equally useful |

16/28 (57.1%) |

Both are equally useful |

9/27 (33.3%) |

|

Why long-term? (open-ended question) |

Stability of volunteers’ engagement |

5/28 (17.9%) |

Long-term volunteers could enable to plan stable flow of services in the organization |

7/27 (25.9%) |

Experience that enables forming better relations |

3/28 (10.7%) |

Their skills |

6/27 (22.2%) |

|

Experience in performing tasks |

3/28 (10.7%) |

Capacity to participate in the association and community |

4/27 (14.8%) |

|

Higher trust |

1/28 (3.6%) |

Their impact on users |

2/27 (7.4%) |

|

Why episodic (short-term)? (open-ended question) |

Cultural changes encourage episodic engagement |

1/28 (3.6%) |

||

Why are they equally important? (open-ended question) |

Any help is important |

15/28 (53.6%) |

Different capacities of volunteers to plan stable flow of services in the organization |

4/27 (14.8%) |

Ensuring stability |

1/28 (3.6%) |

Their impact on beneficiaries |

1/27 (3.7%) |

|

Fresh perspective (episodic) |

1/28 (3.6%) |

Their skills |

6/27 (22.2%) |

|

Stability of help |

2/28 (7.1%) |

|||

Support for the organization |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Building relations with the beneficiaries (long-term) |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Do you think that, in general, long-term or episodic volunteers are more important in achieving your organization's goals during the sudden social crisis? (multiple-choice question) |

Long-term are more useful |

10/28 (35.7%) |

Long-term are more useful |

9/27 (33.3%) |

Episodic are more useful |

5/28 (17.9%) |

Episodic are more useful |

1/27 (3.7%) |

|

Both are equally useful |

13/28 (46.4%) |

Both are equally useful |

17/27 (63.0%) |

|

Why long-term? (open-ended question) |

Stability of help |

5/28 (17.9%) |

Because of their skills |

4/27 (14.8%) |

Experience in tasks |

2/28 (7.1%) |

The capacity to plan in the organization |

3/27 (11.1%) |

|

Any help is important |

1/28 (3.6%) |

Their participation in the organization |

3/27 (11.1%) |

|

They have knowledge about the organization |

1/28 (3.6%) |

Difference that exists between volunteers in terms of their type of commitment |

1/27 (3.7%) |

|

Why episodic? (open-ended question) |

Highlighting the importance of any help |

1/28 (3.6%) |

They represent a valuable resource, especially during time-constrained interventions |

1/27 (3.7%) |

Easier to engage in the tasks episodically |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Fresh energy episodic volunteers bring |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Why is it equally important? (open-ended question) |

Any help is important |

11/28 (39.3%) |

Because of their skills |

9/27 (33.3%) |

Stability of help (applicable to the long-term volunteers) |

2/28 (7.1%) |

Differences in terms of their type of commitment |

6/27 (22.2%) |

|

Experience they have |

1/28 (3.6%) |

The planning in organization in particular crisis situations |

3/27 (11.1%) |

|

Fresh energy (applicable to the episodic volunteers) |

1/28 (3.6%) |

Because of their participation in the organization |

2/27 (7.4%) |

|

Because of their resources, especially in times of sudden situations |

1/27 (3.7%) |

Table 2 Perceived differences in the involvement of volunteers in the organization during social crises according to volunteer coordinators

Question |

Answer options Polish sample |

Frequencies |

Answer options Italian sample |

Italian sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Do you think that volunteers in your organization get involved in a different way than usual during social crises such as a pandemic or humanitarian crisis?—1 (yes/no question) |

Yes—they observed different involvement of volunteers during social crises |

17/28 (60.7%) |

Yes—they observed different involvement of volunteers during social crises |

21/27 (77.8%) |

No—they did not observe different involvement of volunteers during social crises |

11/28 (39.3%) |

No—they did not observe different involvement of volunteers during social crises |

6/27 (22.2%) |

|

If yes, what is the difference in volunteer involvement in your organization during social crises? (open question) |

They observed higher engagement during social crises |

10/28 (35.7%) |

They observed higher engagement during social crises |

7/27 (25.9%) |

They observed lower engagement during social crises |

3/28 (10.7%) |

They observed lower engagement during social crises |

6/27 (22.2%) |

|

They changed the way they help during crises by altering the form of helping and broadening the group of beneficiaries |

2/28 (7.1%) |

They noticed an increase in personal, professional, and motivational skills |

4/27 (14.8%) |

|

The suspension of volunteering by organizations |

1/28 (3.6%) |

They noticed generational differences in approaching the service |

3/27 (11.1%) |

|

A change in the age groups that participate in volunteering |

1/28 (3.6%) |

A reduction of interpersonal skills |

2/27 (7.4%) |

|

The increase of obstacles |

1/27 (3.7%) |

|||

Why did they observe higher engagement during social crises? (open question) |

Personal qualities of volunteers play a role, among which they outlined values, responsibility, and sensitivity to harm |

6/28 (21.4%) |

Declared because of an increase in their emotional involvement |

3/27 (11.1%) |

It was a matter of overcoming hopelessness |

4/28 (14.3%) |

Increase of volunteers’ self-enhancement |

2/27 (7.4%) |

|

It was a reaction to facing a crisis |

4/28 (14.3%) |

|||

Why did they observe lower engagement during social crises? (open question) |

Health-related anxiety |

2/28 (7.1%) |

Decrease in their emotional involvement |

5/27 (18.5%) |

Negative emotions |

1/28 (3.6%) |

Due to psychological or daily life obstacles or resources |

6/27 (22.2%) |

|

Lack of volunteer support system |

1/28 (3.6%) |

Related to generational differences (i.e., the age of volunteers – elderly were more fragile than young volunteers) |

4/27 (14.8%) |

|

Faster burnout during a crisis |

1/28 (3.6%) |

Diversity among types of volunteers |

1/27 (3.7%) |

|

Suspension of the activities in an organization during the crisis |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Change of focus of volunteers and redirecting their help to those who need it more during a social crisis |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Did the engagement of volunteers increase/decrease/stay the same after COVID-19? |

Increased |

2/28 (7.1%) |

Increased |

2/27 (7.4%) |

Decreased |

10/28 (35.7%) |

Decreased |

9/27 (33.3%) |

|

Stayed the same |

16/28 (57.1%) |

Stayed the same |

16 (59.3%) |

Table 3 Volunteer retention strategies in organizations

Question |

Answer options Polish sample |

Frequencies |

Answer options Italian sample |

Frequencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Does your organization have any formal retention strategy for the volunteers to remain in the organization for longer? (yes/no question) |

Yes |

9/28 (32.1%) |

Yes |

5/27 (18.5%) |

No |

19/28 (67.9%) |

No |

22/27 (81.5%) |

|

If yes, what are the primary ways of retaining volunteers as outlined in this strategy? (open question) |

The organization offers support to volunteers through forming/maintaining relationships |

5/28 (17.9%) |

Paying attention to their volunteers' well-being |

3/27 (11.1%) |

Practical support during performing volunteering |

3/28 (10.7%) |

Training |

3/27 (11.1%) |

|

Support of competence development |

3/28 (10.7%) |

|||

Gratification system |

2/28 (7.1%) |

|||

Practical benefits offered to volunteers |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Psychological aid |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Support in general development |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Flexibility in formal agreements with volunteers |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Acknowledging their efforts |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Communication enhancement |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Offering a variety of quality tasks |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Specialist care |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Encouraging independence |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

What is the success rate of this strategy? (scale from 1—no success; to 10—full success) |

6.33 |

6.20 |

||

What could be done better to retain volunteers during crises? (open question) |

Psychological support for the well-being of volunteers |

7/28 (25.0%) |

Supporting volunteers (general) |

9/27 (33.3%) |

Improvement in communication |

3/28 (10.7%) |

Promoting their identification with the organization |

8/27 (29.6%) |

|

Protection of volunteers against burnout |

3/28 (10.7%) |

Recognizing the importance of the volunteers’ service |

3/27 (11.1%) |

|

Educational activities for volunteers |

2/28 (7.1%) |

|||

Supervision for volunteers |

2/28 (7.1%) |

|||

Periodical extra recruitments |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Enlargement of the coordinators’ staff |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Securing meals for the volunteers |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Providing more financial resources for coordinators to perform their tasks |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Openness of the organization |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Motivational systems for volunteers |

1/28 (3.6%) |

|||

Table 4 The behavior of beneficiaries during social crises, according to volunteer coordinators

Question |

Answer options Polish sample |

Frequencies |

Answer options Italian sample |

Frequencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

How do you think beneficiaries of voluntary work usually behave when there is an unexpected social crisis (pandemic, humanitarian/refugee crisis)? (multiple choice) |

Beneficiaries tend to rely on formalized non-governmental organizations during social crises |

21/28 (75.0%) |

Beneficiaries tend to rely on formalized non-governmental organizations during social crises |

13/27 (48.1%) |

They seek other forms of help, such as neighbors, local support, etc |

4/28 (14.3%) |

They seek other forms of help, such as neighbors, local support, etc |

14/27 (51.9%) |

|

They do not seek help during crises |

3/28 (10.7%) |

They do not seek help during crises |

0/27 (0%) |

|

Why do they seek formalized support? (open question) |

Trust toward non-governmental organizations |

12/28 (42.9%) |

The relational and material capacities of NGOs |

6/27 (22.2%) |

Accessibility of these organizations |

3/28 (10.7%) |

Formalized support entities are the only option |

2/27 (7.4%) |

|

Effect of word-of-mouth marketing |

2/28 (7.1%) |

The promptness in providing help |

1/27 (3.7%) |

|

Recognition of these organizations |

1/28 (3.6%) |

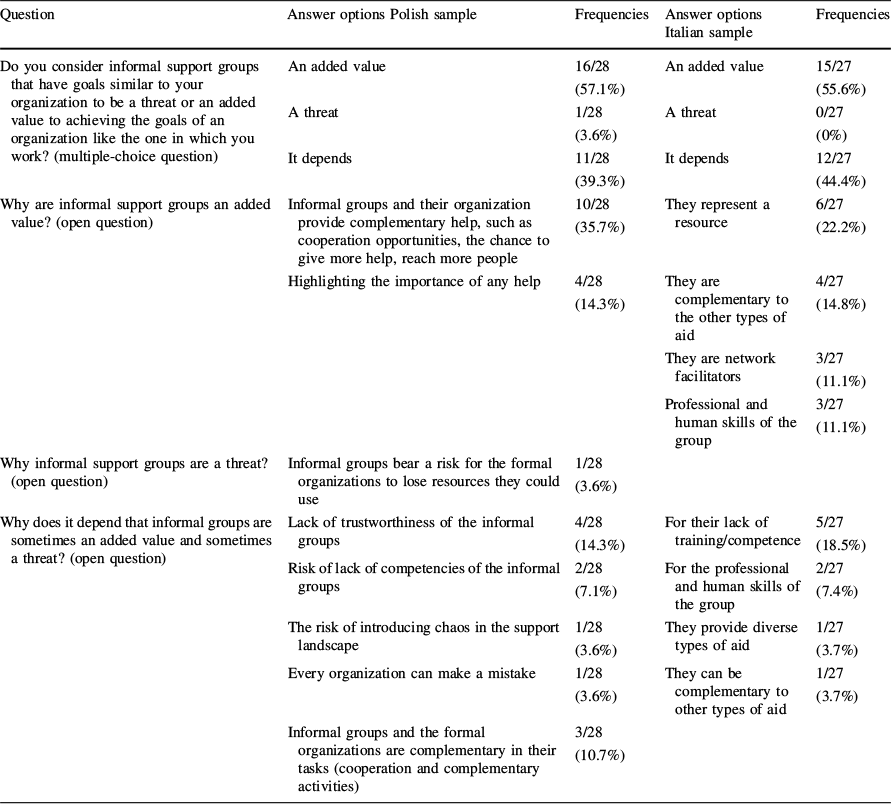

Table 5 Volunteer coordinators’ opinions about informal support groups in relation to formal organizations

Question |

Answer options Polish sample |

Frequencies |

Answer options Italian sample |

Frequencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Do you consider informal support groups that have goals similar to your organization to be a threat or an added value to achieving the goals of an organization like the one in which you work? (multiple-choice question) |

An added value |

16/28 (57.1%) |

An added value |

15/27 (55.6%) |

A threat |

1/28 (3.6%) |

A threat |

0/27 (0%) |

|

It depends |

11/28 (39.3%) |

It depends |

12/27 (44.4%) |

|

Why are informal support groups an added value? (open question) |

Informal groups and their organization provide complementary help, such as cooperation opportunities, the chance to give more help, reach more people |

10/28 (35.7%) |

They represent a resource |

6/27 (22.2%) |

Highlighting the importance of any help |

4/28 (14.3%) |

They are complementary to the other types of aid |

4/27 (14.8%) |

|

They are network facilitators |

3/27 (11.1%) |

|||

Professional and human skills of the group |

3/27 (11.1%) |

|||

Why informal support groups are a threat? (open question) |

Informal groups bear a risk for the formal organizations to lose resources they could use |

1/28 (3.6%) |

||

Why does it depend that informal groups are sometimes an added value and sometimes a threat? (open question) |

Lack of trustworthiness of the informal groups |

4/28 (14.3%) |

For their lack of training/competence |

5/27 (18.5%) |

Risk of lack of competencies of the informal groups |

2/28 (7.1%) |

For the professional and human skills of the group |

2/27 (7.4%) |

|

The risk of introducing chaos in the support landscape |

1/28 (3.6%) |

They provide diverse types of aid |

1/27 (3.7%) |

|

Every organization can make a mistake |

1/28 (3.6%) |

They can be complementary to other types of aid |

1/27 (3.7%) |

|

Informal groups and the formal organizations are complementary in their tasks (cooperation and complementary activities) |

3/28 (10.7%) |

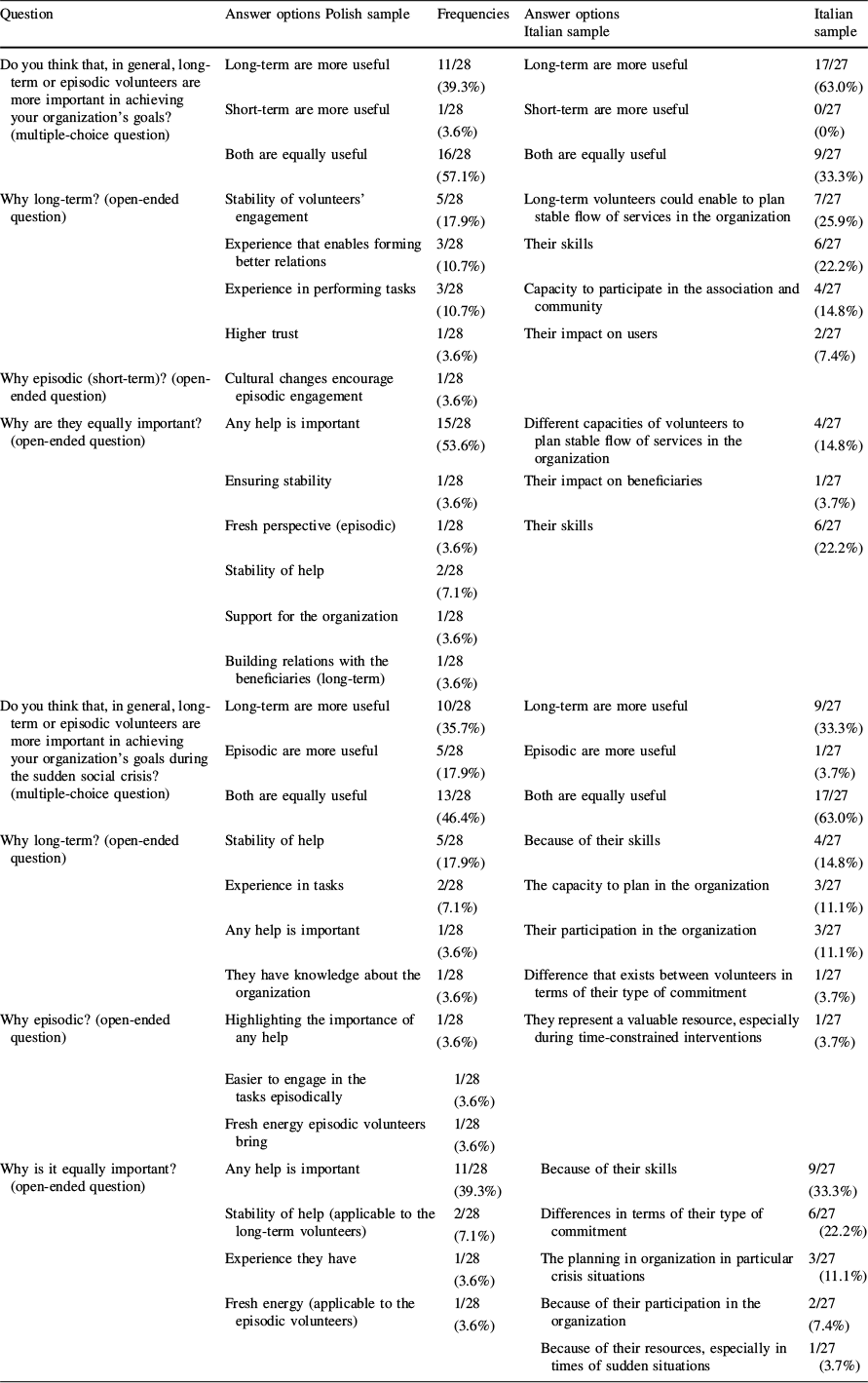

Table 1 shows the coordinators’ opinions about the engagement of long-term and episodic volunteers in the organization they worked for.

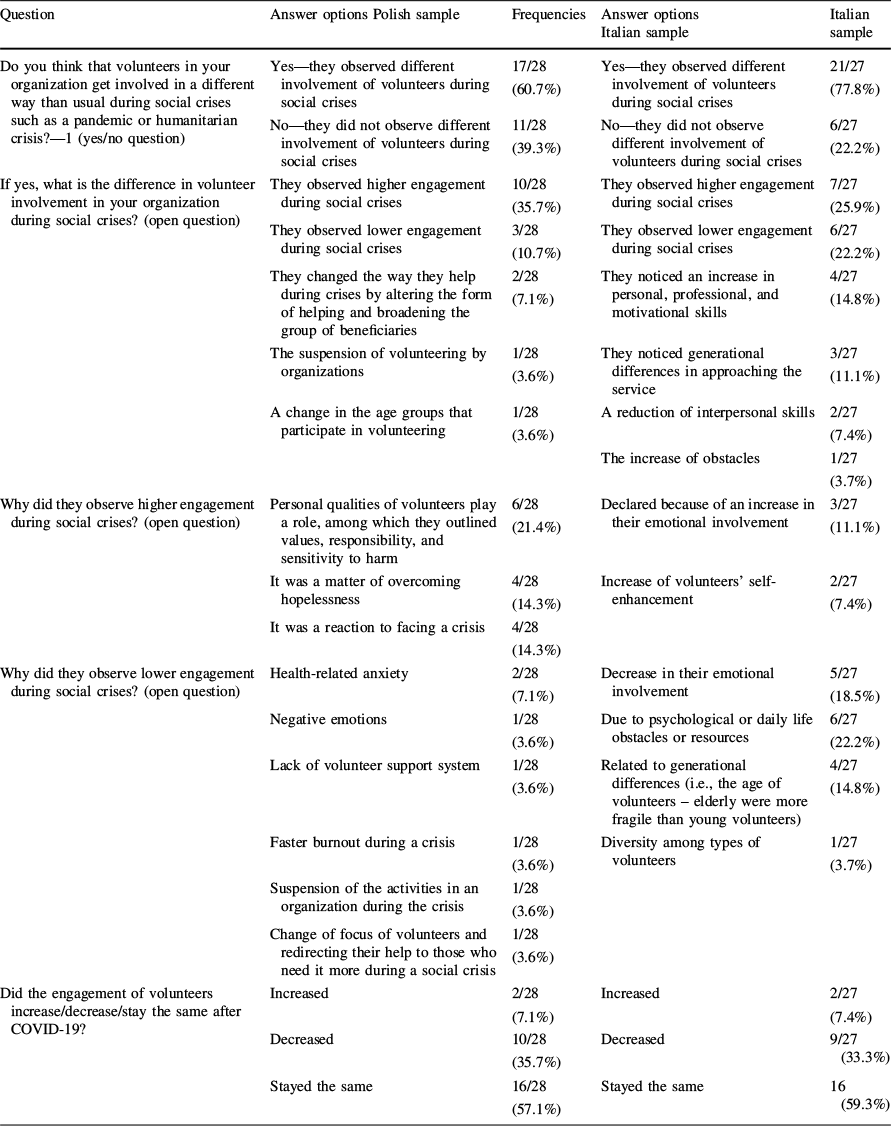

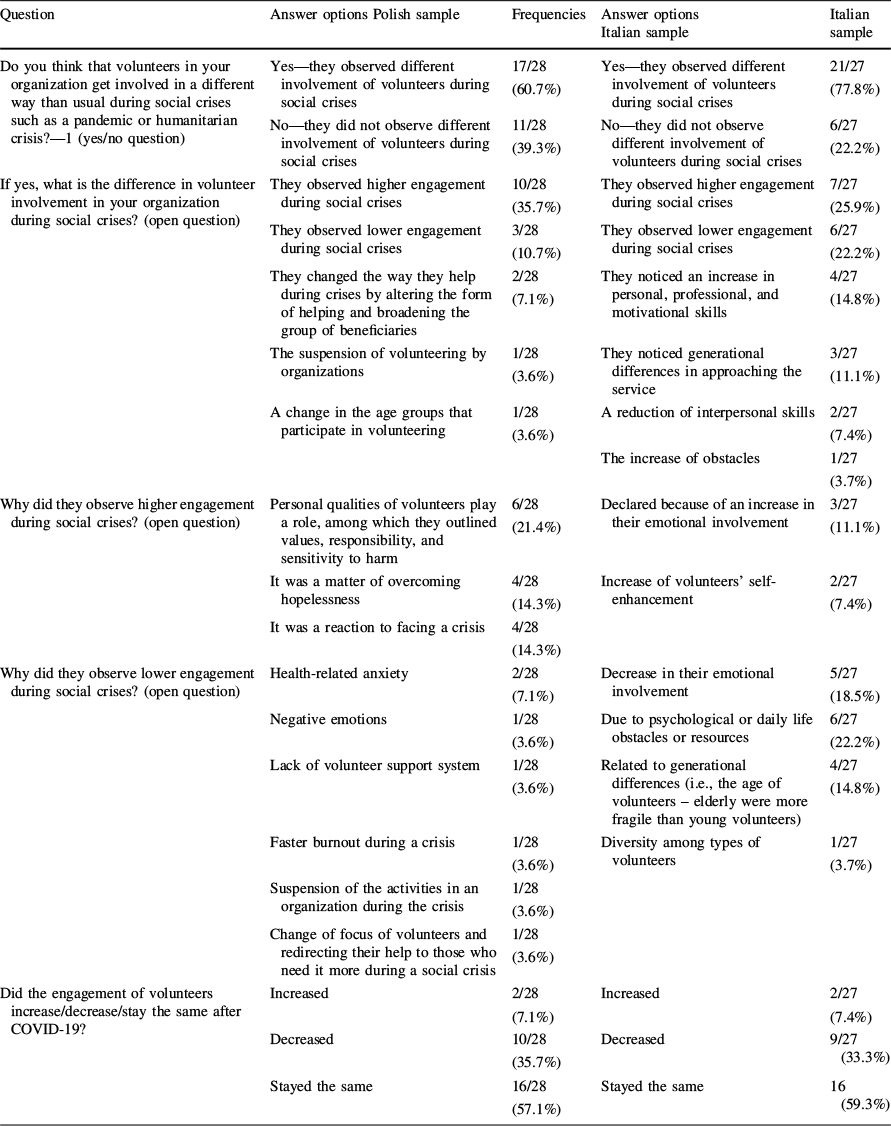

Table 2 shows the perceived differences in volunteers' involvement in the organizations the coordinators worked for during recent social crises compared to regular times.

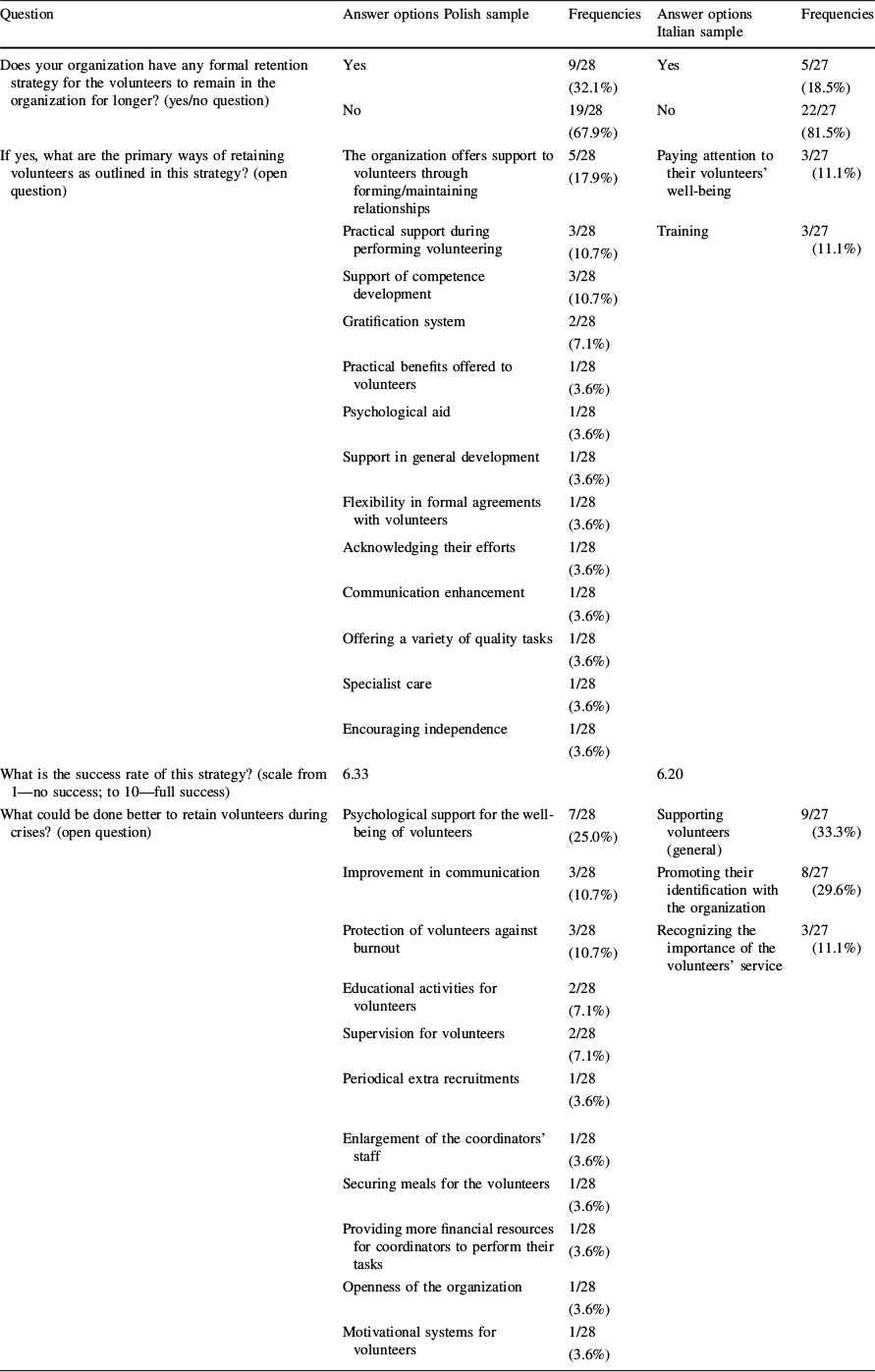

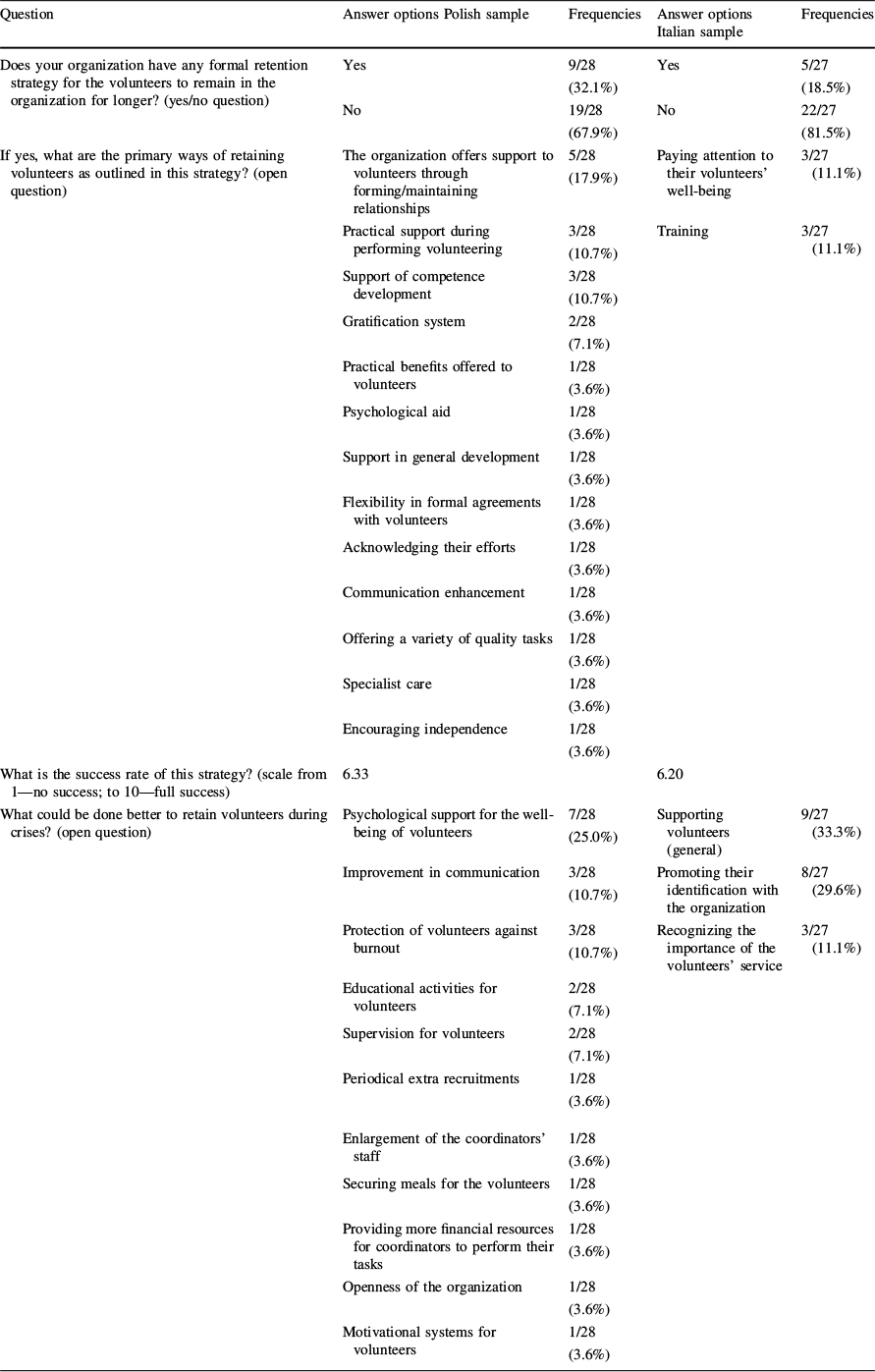

Table 3 shows the coordinators' opinions about volunteer retention strategies and ways to improve them in their organizations.

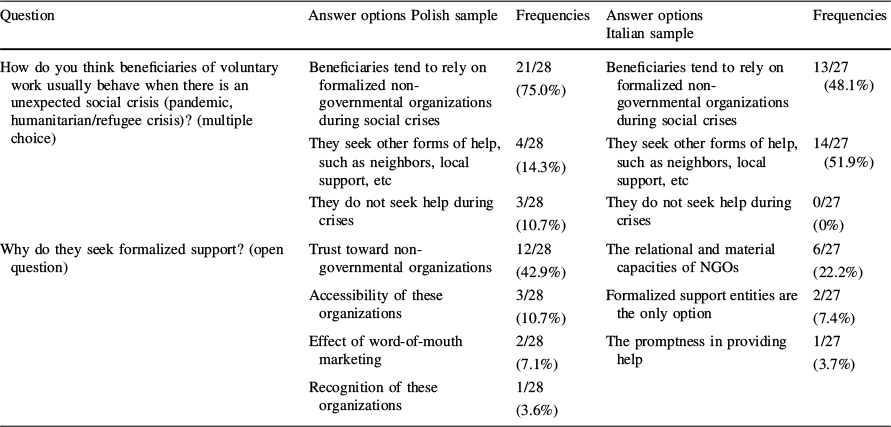

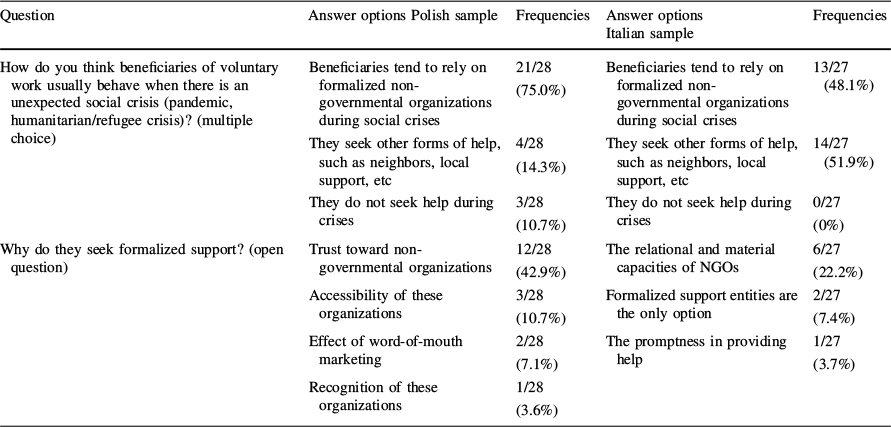

Table 4 shows how coordinators perceived the behavior of beneficiaries during social crises.

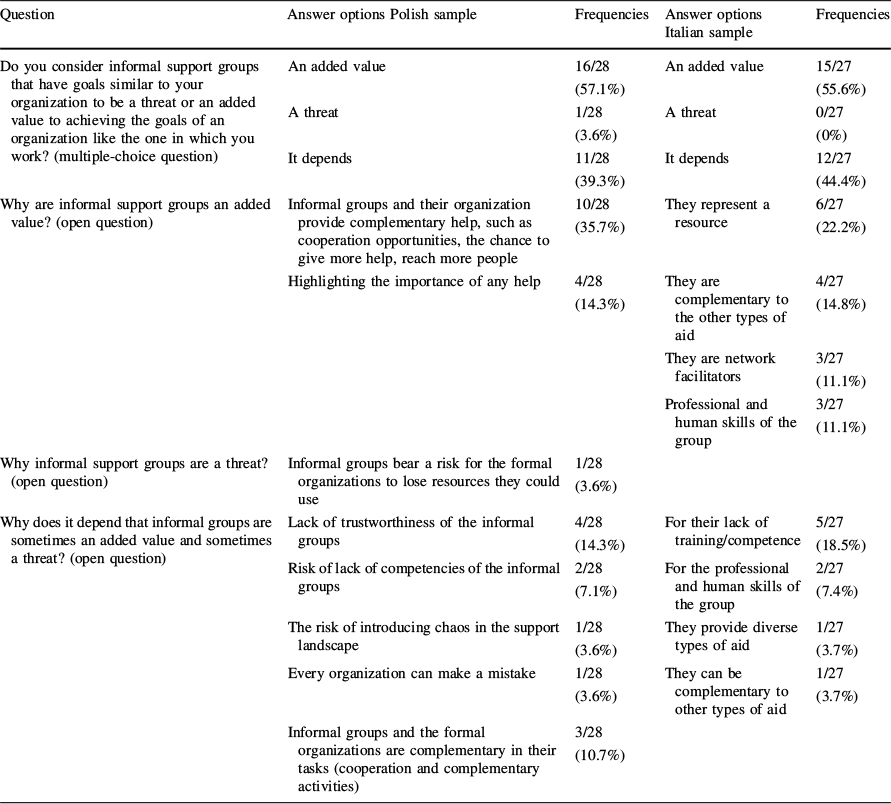

Table 5 shows the coordinators’ opinions about informal support groups in relation to the organizations they work for.

Discussion

First, we found that the majority (57.1%) of Polish participants indicated that both long-term and episodic volunteers are an asset to their organization during non-crisis times. In contrast, for Italian participants, the long-term volunteers were of the greatest importance (63.0%). For neither of the groups, the episodic volunteers were considered more crucial for the organization's regular operations than long-term volunteers. Given the critical role in the organizations’ operations (Hyde et al., Reference Hyde, Dunn, Scuffham and Chambers2014), and the difficulties retaining volunteers due to, e.g., changing patterns of paid work, organizations may perceive the long-term volunteers as a precious and increasingly rare resource. For Poland, the episodic volunteers were also considered essential. This might be due to the very popular actions in Poland, which involve many episodic volunteers alongside long-term ones (Bill, Reference Bill2022; Salwa & Zipf, Reference Salwa and Zipf2015). These seasonal actions are inclusive to new or one-time volunteers, and the engagement quality is independent of how long a person is involved. Therefore, the result might have been different from the one in Italy.

In Italy, the preference for long-term volunteers in non-crisis periods may be due to the reform affecting voluntary organizations and the third sector as a whole (done by Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali in 2017; see Fici, Reference Fici and Fici2024). This reform has affected the entire third sector and the universal civil service and still affects some changes born in non-crisis periods. We could hypothesize that the preference for long-term volunteers is due to the current adaptation of organizations to an ongoing change that already requires enormous efforts. Including episodic volunteers in this delicate phase of change requires additional efforts that could be a deterrent to their preference.

We found that in the case of social crises, the highest percentages for both groups (46.4% Polish coordinators and 63.0% Italian coordinators) indicated that long-term and episodic volunteers are equally crucial to pursuing the organization's goals. Crises are when spontaneous volunteering occurs, including people who did not engage before. Many remain active only for a particular event and cease engagement immediately when a crisis fades out (Kulik, Reference Kulik2022). The reason behind this episodic activity may be a sense of moral obligation, e.g., when witnessing the suffering of refugees and the inability to stay indifferent (Nowakowska, Reference Nowakowska2024). Looking at the phenomena from the SET perspective, volunteering during the crisis may bring more costs and fewer benefits for the volunteer, as the work is often more intense and less adjusted to the needs of the volunteer. As a result, the costs of such help outweigh the benefits (Drollinger, Reference Drollinger2010).

Most participants in both countries thought that social crises bring differences in volunteer engagement (60.7% Polish and 77.8% Italian coordinators). Most Polish coordinators declared that the change during a crisis is about increased engagement (35.7%). However, Italians declared paradoxical effects: an increase in engagement (25.9%) or a decrease in it (22.2%). For Poland, it could have been due to the visible social support mobilization during the COVID-19 (Nowakowska, Reference Nowakowska2023) and the Ukrainian refugee crisis (Byrska, Reference Byrska2023), when the civil society mobilized formally and informally to tackle the challenges related to the events. For Italy, similarly, COVID-19 encouraged a massive mobilization of mutual aid among citizens (Zamponi, Reference Zamponi2023).

Nevertheless, from the open-ended questions among Italians, we can assume that the crisis decreased emotional involvement in voluntary activities. The daily life obstacles could have also hindered it. Presumably, the lockdowns and economic struggles (Rubinelli, Reference Rubinelli2020) had a negative impact on the readiness to participate, and the disconnection from the community and pursuit of material resources could have resulted in lowered volunteering rates. This explanation is in line with BPNT, as limiting the contacts with family and friends results in frustration of the need for relatedness, and staying at home also frustrates the need for autonomy, which may result in a lack of motivation toward different types of activities, including volunteering (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017).

However, when asked what the situation looked like after the crisis pandemic, most of the coordinators declared that the volunteers engaged similarly to what was observed before (57.1% and 59.3% for Poles and Italians, respectively). The insight that the support is similar to what was observed before the pandemic is promising and shows the organizations' and volunteers' resilience in bouncing back from crisis-related adversities in both countries.

Only 32.1% of Polish and 18.5% of Italian coordinators declared that their organization has a formal strategy for retaining volunteers. These strategies were similar in both countries as they concentrated on satisfying needs (care for well-being, relationships, and competencies related to volunteering). These contents resemble the basic psychological needs satisfaction (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017). It seems to be an adequate starting point for the retention strategies, given that basic psychological needs satisfaction predicts intentions for future volunteering and turnover intentions (Haivas et al., Reference Haivas, Hofmans and Pepermans2013; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Bortree, Yang and Wang2020). Thus, organizations should give opportunities and support volunteers in being autonomous (e.g., agentic, able to put out initiatives), competent (e.g., by developing their skills or able to mentor others), and care for the positive relationships within the volunteering environment (both with the beneficiaries and with other volunteers). Similarly to motivations identified by Babula and Muschert (Reference Babula and Muschert2023), during crises, when the challenges of volunteer management intensify for formal organizations, acknowledging the primary can guide the development of support and engagement strategies that align with volunteers' intrinsic needs. Noteworthy, the average ratings of the quality of this strategy were ca. 6 (on a scale of 0–10) for both countries, suggesting moderate satisfaction with it and that more needs to be done in terms of their contents and implementation.

When questioned about how to improve retention strategies to address the challenges posed by social crises, Poles emphasized psychological support, protection from burnout, and improved communication and educational activities. The pattern of results is in line with findings that suggest mental health issues as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the increased interest in seeking psychiatric support in Poland (Bliźniewska-Kowalska et al., Reference Bliźniewska-Kowalska, Halaris, Wang, Su, Maes, Berk and Gałecki2021). Volunteer coordinators recognized this tendency, and according to it, they also tended to indicate that mental health-related support was crucial.

The Italian group also mentioned psychological support and care for well-being in relation to retention strategies, but this was not the dominant suggested strategy. Strategies of this kind are essential for volunteers to maintain mental health and prevent burnout, especially during crises (Yang, Reference Yang2021). It is worth noting that BPNT suggests that one of the most effective ways of improving well-being is to ensure that the social environment supports the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs (Ryan, Reference Ryan2009). From the perspective of SET, many of the suggestions for retention strategies may be summarized as increasing the benefits (compared with the costs) of volunteering, making people more motivated toward this form of activity (Drollinger, Reference Drollinger2010).

For the retention strategies, Italian coordinators suggested general improvements related to support, promoting the identification of volunteers with the organization, and volunteer recognition. It aligns with the Italian evidence regarding frustration and burnout in volunteer work, especially among healthcare volunteers (Chirico et al., Reference Chirico, Batra, Batra, Oztekin, Ferrari, Crescenzo, Nucera, Szarpak, Sharma, Magnavita and Yildirim2023). Greater attachment of volunteers to the organization and recognition of their efforts could help prevent such adverse effects. Nevertheless, suggestions in both countries were generally congruent with the findings by Cho et al. (Reference Cho, Wong and Chiu2020), who indicated reward, recognition, flexibility of schedule, empowerment, training, and social interactions as positive volunteer management strategies that support the intention to continue the activity.

However, Polish coordinators did not point out an important aspect that the Italian ones mentioned, which is the promotion of identification of volunteers with the organization. Role identity is one of the most important predictors of volunteer engagement (Grube & Piliavin, Reference Grube and Piliavin2000). Thanks to internalizing the volunteer role, a person could be less inclined to give up on engagement as it is an element of their self. Conversely, Italian coordinators overlooked the importance of communication between the organization and the volunteers. The differences might have resulted from cultural differences in values or dominant management styles; however, this result needs further investigation.

For the typical behaviors of beneficiaries during crises, 75.0% of Polish coordinators indicated that the beneficiaries mainly seek non-governmental organizations' support, arguing that it is a matter of trust toward them. A relatively large percentage – 48.1% of Italians also indicated non-governmental organizations as the primary source of support sought during crises, underlining the role of relations and material perception of these organizations in society. Our results are congruent with the existing literature. Trust in organizations that provide help is crucial during emergencies, and lack of transparency is considered a concern (Palttala et al., Reference Palttala, Boano, Lund and Vos2012). Non-governmental organizations provide support complementary to the one provided by the government, and they can cope with the crisis and gain public trust. They are aware of the needs of the communities.

Finally, informal support groups in both Polish and Italian samples were not considered a definite threat. A similar percentage of coordinators from Poland (57.1%) and Italy (55.6%) found them an added value to their operations. The complementarity of the provided help was a common theme.

Similar percentages of Polish (39.3%) and Italian (44.4%) coordinators also declared that it depends on whether such groups are an added value or a threat. Polish coordinators highlighted the concerns about trustworthiness among the people constituting such groups, and both groups mentioned the skills needed to help, which may vary across informal groups. Our results are congruent with the literature about the complementarity of formal and informal volunteering (Helms & McKenzie, Reference Helms and McKenzie2014). Nevertheless, despite the promising avenues for cooperation between formal and informal entities in volunteering, the credibility of provided help still needs to be cared for, and formal organizations can act as leaders and role models of credibility, trustworthiness, and high-quality help.

Study limitations

In our study, we explored the individual perspectives of the participants (and indirectly, the organizations for which they perform their work) to extend the existing body of knowledge and check whether the same patterns apply to two European countries with different experiences with social crises.

Using an online written survey did not give us control over how the coordinators responded to the survey. We also did not have the opportunity to ask for elaboration or clarification of the given answers, which is an important limitation of our study. Nevertheless, thanks to an online tool, we reached out to more coordinators and encouraged them to devote their time to participation in our study. It is essential to acknowledge that the participation of coordinators working for organizations that work for diverse causes may have introduced an unintended limitation to the study.

Future research directions

Future research should continue to explore the underresearched perspectives of volunteer coordinators, preferably using quantitative and qualitative approaches under a single research plan. It could also utilize observational studies on real-life volunteering patterns (e.g., monitoring volunteers' activity throughout a challenging time). Longitudinal approaches are therefore needed to increase the generalizability of the results and enable the monitoring of the opinions about volunteer engagement and the organization's operations over time. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to conduct comprehensive research on organizations of a homogeneous kind in terms of primary beneficiaries or volunteering themes. Future studies could focus not only on volunteer coordinators but also on how volunteers perceive the shifts in their activity during social crises and how the general society sees the value of volunteering during these challenging times.

Conclusions and practical implications

The evidence presented pertains to two selected countries: Poland and Italy. We acknowledge that collecting data in different places could have enriched or changed the results' pattern. Noteworthy, in many cases, provided explanations were similar, suggesting that at least some of the investigated phenomena exist beyond geographical borders.

The results suggested that long-term and episodic volunteers play crucial roles, given their activities' complementarity and usefulness in pursuing the organization's goals. The volunteer retention strategies are worth outlining or revisiting, as the activities they contain do not fully satisfy the needs perceived by coordinators and do not fulfil the literature-driven recommendations. Moreover, attention should be paid to the psychological support of volunteers in order to care for their well-being and mental health and prevent burnout and turnover intentions. Working on the trust toward organizations of communities and society at large can help organizations achieve their goals and encourage beneficiaries to seek their help during social crises. Collaboration with informal groups is advised, given that the goals can be achieved together, mutually using the resources provided by both types of helping entities and the potential for mutual learning. Organizations should consider broadening the scope of their operations to act faster, work for better overall support, and effectively complement the activities of informal organizations while not competing with them.

Funding

The research has been made possible by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange, Bekker programme, Agreement no. BPN/BEK/2022/1/00001, awarded to Iwona Nowakowska.

Data Availability

The materials (questionnaire) and quotations along with themes assigned in the analytic process can be accessed freely at Open Science Framework at: https://osf.io/g2kas/.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors declare conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The study materials and procedure were approved by Research Ethics Committee at The Maria Grzegorzewska University. The study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki (2001). All participants provided informed consent in accordance with Standard 3.10, Informed consent, of the APA Ethical Guidelines.