Walter Scott Moves On from Ossian

By 1803, Macpherson’s Ossian was thoroughly discredited as a rank forgery. In English culture, the position of ‘Bard of the Nation’ had fallen vacant and was now increasingly allocated to Shakespeare. North of the Scottish border, however, Walter Scott was beginning his literary rise. He edited ancient ballads from the Scottish–English borderlands (Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, 1803) and on that basis created an original narrative ballad, ‘The Lay of the Last Minstrel’ (1805). Although the setting is late-to-post-chivalric rather than primitive antiquity, and the poet figure is a ‘minstrel’ rather than a ‘bard’, the stage is still set in the Ossianic mode: we are at the tail-end of an era. The profession of minstrelsy has lost its standing, and the minstrel himself is old and decrepit. Indeed, as Scott himself phrases it in Ossianic diction, ‘the last of all the Bards was he’: a relic of the past.1

The wandering poet is invited to perform for the noble Buccleugh family, for whom he, quite literally, channels the past in rapturous, Ossianic inspiration (not unlike the guslar on the Karadžić frontispiece, Figure 5.1):

Again, that fixed stare into a space of inspiration, as with Ossian and the Serbian guslar. The minstrel recalls the past, and whatever is not solid memory is supplied by the imagination.

What then follows is the tale of a baronial feud of bygone days; but at the ending we return to the frame story and the aged performer. The fate of this wandering bard is much more cheerful than that of Ossian. The grateful duchess provides him with a little cottage under the castle walls to live out his days, and here he performs his ancient songs for appreciative passers-by.

Scott’s minstrel both echoes and bypasses Ossian, and that in two ways. To begin with, as Ann Rigney has noted, the minstrel manages to turn his pastness into gainful employment, in almost a prefiguration of what Scott was to become himself: a voice from the past, recalling bygone deeds but with a huge appeal to present-day audiences. Antiquity becomes historicism: pastness obtains a function in the present.3

The other innovation that Scott introduces is his deft use of a layered perspective. The frame story is already set in the past (somewhere in the later seventeenth century) and at this past moment the minstrel recalls an even earlier historical episode: we approach the past telescopically, through a frame story containing a ballad relating the past events. This is an early sign of Romantic historicism: unlike antiquaries, the historians of Scott’s generation were acutely aware of their source dependency, the fact that they gained access to the past by way of sources that were themselves part of the past. A few decades later, the historian Leopold von Ranke would turn this awareness – how to cope with one’s source dependency – into a keystone of his scholarly method. He devised an entire methodology of ‘source criticism’ (Quellenkritik) and in addition fixed a cognitive point on the horizon: to get an ‘immediate’, umediated sense of the past as it had actually been experienced at the time, liberated from its im-mediation in third-party informants.Footnote * This approach parallels the philological attempt to critically compare different manuscript variants to arrive at a putative Urtext, the text as it must have been imagined at the moment of its creation.4

For academic scholars (historians such as Ranke, philologists of the Lachmann school), this source dependency is a problem to be dealt with; Scott, however, turns it into a virtue, an attractive narrative strategy. Paradoxically, he makes his evocation of the past more realistic by explicitly evoking the tunnelling trajectory one has to perform between Now and Then, the many generations and transitions that separate us from a receding Long Ago. In Old Mortality (1816), the days of the Covenanting wars (1679) are approached through a survivor (nicknamed ‘Old Mortality’) who maintains the graves of the fallen, striving to stave off their oblivion. This stratagem renders the past truly exotic: alien and alluring at the same time, something approached in an enticing game of disclosure and deferral.

Scott does the same for Scotland itself. He always approaches the most colourful destinations in that country from a starting point of familiar domesticity and reaches them by way of successive stages, each with increased exotic strangeness. In Rob Roy (1818), the English narrator moves first to the mansion of his rough-hewn relatives in Northumberland; then, in a daring escape, across the border to the unknown and adventurous setting of Glasgow; and finally to the haunts of the wild Highlander, Rob Roy McGregor himself, around the shores of Loch Katrine. The mechanism is most noticeable in the novel that turbocharged Scott’s literary career, Waverley (1814). It marked Scott’s transition from dramatic poems set in the past (The Lay of the Last Minstrel, Marmion, The Lady of the Lake) to the genre of historical prose fiction. Scott had become a celebrity as a poet and was in 1820 given the title of baronet. He sought to avoid the stigma of being a mere novelist (the novel was at that time considered a trivial pastime, and not serious literature at all), so that Waverley was published anonymously, and subsequent novels were stated to be ‘by the author of Waverley’. It was only after those ‘Waverley novels’ had become a literary sensation, and well and truly redeemed from the stigma of triviality, that Scott owned up to his authorship in 1827. Those novels had meanwhile also become considerable money-spinners; Scott was the first bestseller author in history, turning writing into a business model.

The title hero of Waverley also approaches Scotland, and the Scottish Highlands (where the core of the action is located), in telescoping stages. He is sent from his native England to Dundee and stays with a family friend in Perthshire, close to the Highlands. From there he accompanies Highlanders to their home north of Stirling, and it is here, at the residence of the MacIvor clan, that he encounters the true heart of Scottish exoticism. The acme of that exoticism is reached in Chapter XXII, entitled ‘Highland Minstrelsy’: the attractive sister of his Highland host, Flora, takes him to a wild and remote glen. There, near a picturesque waterfall, she plays the harp for him and performs an ancient Scottish ballad. Waverley’s progress up the glen, following Flora, is a transition from reality into romance: the countryside becomes wilder and more sublime at each turn and step, and the hero, who feels like a ‘knight of Romance’, falls under the spell of the almost supernatural (quite literally ‘enchanting’) Flora. It will not surprise the reader that what Flora finally delivers is Ossian pure and simple: a ballad by ‘Rory Dall, one of the last Highland bards’, beginning ‘Mist darkens the mountain, night darkens the vale, but more dark is the sleep of the son of the Gael!’5

This is how Scott latches onto the Ossianic legacy. As Waverley, starting out from ‘life as we know it’, ventures into the world of Highland minstrelsy, he also moves out of modernity. Scott hammers this message home in the urgent topicality of the novel’s politics. Its subtitle, ’Tis Sixty Years Since, recalls a moment still within living memory for its readers: Waverley is set during the 1745 coup d’état of the exiled pretender to the British throne, Bonnie Prince Charlie (scion of the ousted Stuart dynasty), supported by his adherents in the Scottish Highlands. This 1745 Rebellion posed, briefly, a threat to the Hanover dynasty, established on the throne only since 1715; its failure and bloody suppression broke the political power and independence of the Scottish Highland clans. Like any civil war, it left traumatic memories, unresolved conflicts and divided loyalties in its wake. It is at this critical historical juncture that Scott sets his Waverley. The political divisions between Hanover and Stuart are superimposed on the novel’s oppositional scheme between Now and Then, familiar and exotic, England and Highlands, Anglo-Saxon and Celtic, reality and romance. Waverley is a junior officer in the British army, the MacIvor clan and Flora are adherents of the Stuart pretender. The enchantment that Flora exercises over Waverley makes him join the rebels and their doomed cause, with potentially tragic results.

This makes the novel also a political allegory. Waverley’s escape from his rebellious Stuart entanglement is a return from poetry and romance to a more prosaic form of realism – a dis-enchantment. (He marries a woman of an altogether more sensible disposition than the firebrand revolutionary Flora.) We now usually see the concept of disenchantment in Weberian terms, as a rationalization and secularization process working in tandem with modernity; but enchantment is not exclusively a religious principle, and it makes sense to see Romanticism, an anti-rationalist and anti-Enlightenment paradigm in cultural history, as an attempt to salvage the forces of enchantment; a cultural re-enchantment.Footnote *

Scott balances the contradictory impulses of disenchantment and (re-)enchantment, the coming-of-age novel and the historical romance. Waverley’s predisposition to headlong romantic enchantment is a symptom of his immaturity, and he needs to outgrow it. And with that, Scott also gives his verdict on the 1745 rebellion, still a very precarious topic in Scottish public affairs. The Stuart rebels had romance and poetical allure on their side, with their chivalry, courageous loyalty and colourful traditions; but they were also linked to Scotland’s past rather than to its future. Progress and a sense of practical realism demanded an accommodation with the new, Hanoverian dispensation. Thus, while the interest of the characters and the action undoubtedly lies with the Highlanders and Stuart rebels, the narrator firmly endorses the Hanoverian status quo.

What Scott created, then, was a hybrid genre, uniting the excitement of the romance and the realism of the novel. He reflected on this himself in his article on ‘Romance’ for the 1824 Encyclopaedia Britannica. The central action of Waverley is firmly of a ‘romantic’ nature, evoking medieval chivalric romance, featuring passionate characters and exciting incidents in colourful settings, exotic because of the distance both in time and in space. The authorial voice (the narrator), however, and the framing of the action, are much more in the mode of psychological realism, following the genre of the novel (rather than the romance) as it had been practised by Samuel Richardson and Jane Austen, establishing a rapport between narrator and reader on the basis of of shared (modern, middle-class, sensible) values and experiences. Scott wraps a romance into a novel. In the opening chapters of Waverley, Scott admits in so many words that he had been inspired by Cervantes, realistically evoking a romantic, starry-eyed hero: the delusional Quixote, and the impressionable young Waverley.6

Scott is a master at setting up strong, almost overdetermined binary polarities and then mediating between them: between Scotland’s fond clannish memories and its British, Hanoverian present; between heart and head; between first-love infatuation and mature married life; between enchantment and realism, romance and novel. He also mediated, uniquely, in the relationship between past and present. On the one hand the past is relatable, something where the modern reader is delighted to find points of familiarity or continuity; on the other hand the past is deeply alien, something that requires an act of the imagination to engage with. In Ivanhoe (1819) with its chivalric-medieval setting, points of recognition across the intervening centuries involve the history of dining, its changes and continuities. Scott explains the origin of the still common phrase ‘seated above/below the salt’. He alerts the reader to the lexical dichotomy between livestock and the meat dishes prepared from them (oxen and cows are turned into beef, sheep into mutton, swine into pork), and he points out the ethnic and class associations of such words: Saxon/peasant for the farm animals, Norman-French/aristocratic for the company at the dinner table (boeuf, mouton, porc). Such things create a sense of familiarity across time. On the other hand, the novel revolves around thrilling scenes of lawlessness that render the chivalric Middle Ages truly alien territory: the armchair time-traveller encounters trial by combat, knights jousting, women to be burnt at the stake on the accusation of witchcraft, brigands laying siege to a castle. (Even so, Scott titillates the reader by hinting that the head of these brigands is none other than the familiar folk figure Robin Hood.)

In the hybridity of this genre, Scott can have it both ways: his evocation of the manners and customs of yesteryear has all the authority of the well-informed historian, but his narration of heroes and heroines trying to come to terms with challenging circumstances is pure fiction. This is, as Ranke would call it, the ‘immediate’, non-mediated experience of the past. The modern reader, through the power of the stimulated imagination, senses how it must have felt for Edward Waverley to have to choose between Rose Bradwardine and Flora MacIvor, or for Wilfred of Ivanhoe to reconcile his dutiful loyalty to his Saxon father with his fealty to his Norman liege lord, Richard the Lionheart; or his love for the fair Rowena with the undeniable but impossible chemistry between him and the beautiful, healing Rebecca. The emotional dilemmas and the exciting cliffhangers are such that any reader will breathlessly turn the pages and mentally engage with a bygone age vividly rendered, alive and present. In the process, the arresting anecdotes and glimpses of social manners provide an intellectually stimulating encounter with life as it was long ago. Readers immerse themselves in a history that is both past and present – and that may stand as a definition of Romantic historicism.

Between History and Legend: Facts, Fiction and Fakes

It is well known that not only leisure-time readers but also an entire generation of historians took inspiration from Scott. These Romantic historians show a specific set of characteristic traits. In their writing style, they deliberately emulated Scott’s powers of ‘bringing the past to life’. As a result, they deployed a variety of techniques that strictly speaking were proper to narrative fiction and that were a novelty for the historian’s craft. These narrative strategies involve shifts of perspective, relating the events sometimes in the voice of an omniscient narrator, sometimes focused through the experiences of participants (deliberately selected by the historians as points of sympathetic identification). Also noticeable is an alternation between ‘spectacle’ and narrative. Spectacular writing evokes a scene or situation for the mind’s eye, often even asking the reader to accompany the author’s imagination into a situation that is then described as a tableau, with elements arranged in a quasi-visual, panoramic style. The panorama is static; the account is not about events or occurrences but a stage being set. The description of the successive events then becomes a narrative, and here literary techniques are used such as shifting focuses, back-and-forth juxtapositions between concurrent actions in different locations (the ‘Meanwhile, back at the ranch’ mode), and a dramatic characterization invoking stock characters calculated to evoke sympathy or antipathy: family fathers, haughty courtiers, calculating Jesuits, innocent maidens, stalwart young idealists. Those techniques are, properly speaking, dramatic, theatrical; but this turn towards the dramatic (the melodramatic, even) was made by historians under the novelistic influence of Walter Scott, and it later earned them the qualifications ‘narrative’ and ‘Romantic’ at the same time.7

Yet for all that, these authors were historians, and they took the scholarly part of their calling seriously. They, like the philologists, were living through a sea-change. History writing had been a genre of philosophical disquisition, dominated by the examples of Hume’s History of England and Voltaire’s Siècle de Louis XIV. History was, as the phrase had it, ‘philosophy teaching by example’: the past was studied as a dataset from which to distil what circumstances and decisions had led to the glories or failures of royal reigns or military campaigns. After 1790, the overhaul of libraries and archives and the Napoleon-induced crisis of universities affected this field of learning as much as literary studies. The newly assembled or reorganized archives made different perspectives on past events available, and the study of archival material became the historian’s primary technique. Historians such as Augustin Thierry and Jules Michelet gained their professional experience in the Arsénal and other archives. At the University of Berlin, where Ranke used the Seminar as a dialogic training workshop for history students, a methodology of source criticism was instituted that privileged original archival sources above later-established accounts. Historians became professionally defined by their Rankean Quellenkritik or source criticism and by their reliance on archival, rather than secondary, material. This set them apart from the novelistic liberties that Scott, much to their envy, could take, but it also defined their calling as what was now becoming a profession and an academic discipline rather than a literary–philosophical pursuit. And in subsequent decades, like the professionalizing philologists, the historians, as civil servants in public employ, would write in the service of the nation-state.8

Meanwhile, on the far side of literary fiction, forgery was rife. As we saw in Chapter 4, the archives in these decades yielded unexpected treasures documenting the nation’s forgotten vernacular literary history. These authentic relics of the past were highly prized and in great demand. Philologists competed, as in a gold rush, for the ancient materials that were coming to light: discoveries spoke to the imagination, could make careers, and provided the readers with a sensational feeling of connectedness with the national past. With such high value being set on ancient documents, is it to be wondered at that some of these were manufactured in order to meet the demand? Macpherson was remembered above all as a forger – not altogether fairly, but not quite unjustly either – and as a forger, too, he became a role model. The most egregious of all the forged ‘ancient documents’ that came onto the market were the ‘Bohemian manuscripts’, with the celebrated Czech philologist and antiquary Václav Hanka playing a key role. Found in the localities known as Königinhof/Dvůr Kralové and Grünberg/Zelená Hora, they contained legendary and literary material from medieval Bohemia, purportedly from the thirteenth and even the eighth/ninth centuries. Those materials furnished the Czech readership of the Romantic period (which was just beginning to develop a national self-awareness) with tales of epic, gratifying victories. Now subordinated under the Habsburg crown, Czechs were invited to look back on a proud and authentically Slavic history. The manuscripts dovetailed with legends and myths that had been written down in earlier chronicles and helped flesh out a glorified image of early Czech history. In particular the story of the founding of Prague, invoking legendary ethnic ancestors such as Krok, Cech and the princess/prophetess Libuše, was expanded with additional episodes and characters. In the years when Beowulf, the Nibelungenlied, the Chanson de Roland and the Lay of Prince Igor’s Campaign were drastically realigning the literary–historical landscape of Europe, an additional discovery from the Czech lands was not in itself implausible, and Czech historians such as Palacký actually relied on these manuscripts for the medieval portions of their national histories. The sculptor Myslbek took inspiration from them for some of his public statues, and nationally minded writers such as Čelakovský and Erben also stood by the manuscripts. Philologists, however, habitually fixated on sources and provenance and mindful of the Ossianic imbroglio, were sceptical; there was considerable mistrust around the Bohemian manuscripts, which by some were denounced as fakes. The result was a decades-long controversy. Even when scholars argued, on the evidence, that the manuscripts were fakes, people rallied behind the revered figure of Václav Hanka and doubled down on their belief in the authenticity of the contents; all the more so since the Habsburg authorities had clamped down on Slavic–Czech nationalism after the fateful 1848 revolution (in which intellectuals including Palacký and Hanka himself had played an active part as participants in Prague’s Slavic Congress).9

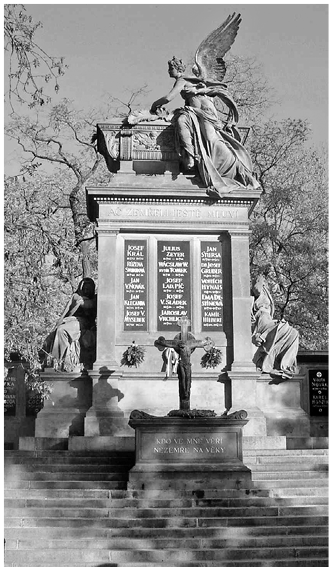

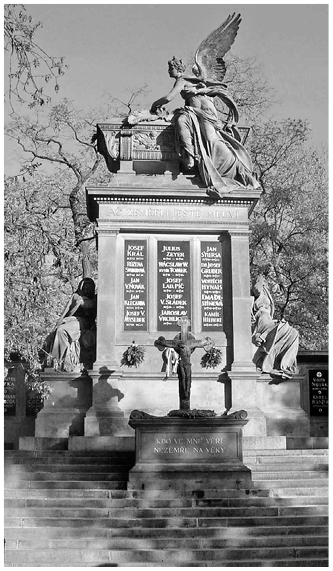

Following Hanka’s death in 1861, his funeral helped to instil the legendary and romantically imagined past into the very cityscape of the Czech capital. Occurring as it did in the repressive post-1848 atmosphere, the funeral provided a rare occasion for a public demonstration of Czech patriotism. It became a mass event; Hanka was laid to rest on the Vyšehrad hill overlooking the river Vltava. Vyšehrad was the site where the mythical Krok, at the behest of his daughter, the prophetess Libuše, had established the castle of the primordial Czech royal lineage and where Libuše had foretold the rise of a great future city (Prague). Already in 1836 the nationalist-Romantic poet Karel Hynek Mácha had been buried here. Following the interment of Hanka in the same spot, Vyšehrad began to emerge as a patriotic pantheon, a shrine infused by the spirit of Libuše herself; re-enchanted in the here and now. As in so many other countries, nationalism was to some extent a cult of the dead, with public funerals providing rare instances of national demonstrations in an atmosphere where the public assembly was not yet an acknowledged part of civil liberty. Certainly in the case of nationalist leaders, whose death could be construed as a form of martyrdom, their funerals fulfilled a strong propagandistic purpose. The Czech poetess Božena Němcová placed what may have been a bouquet of flowers, a laurel wreath or a crown of thorns on the coffin of the persecuted nationalist poet Karel Havliček Borovský in 1856; she herself was buried at Vyšehrad in 1862. A central monument called Slavín was erected there in 1880 (Figure 7.1), and even under the shadow of the Nazi occupation, Alphonse Mucha, like so many other great Czech artists and public figures before and after him, was buried there in 1939.

Figure 7.1 Slavín memorial in the Vyšehrad cemetery, Prague.

Vyšehrad thus became ‘hallowed ground’: a site where medieval legend and modern nationalism meet, in a sort of timeless time-share. Figures of Romantic legend, poets, artists and historians (Libuše, Hanka, Němcová and Mucha) are all stakeholders in this lieu de mémoire (and as Pierre Nora pointed out in coining that phrase, a lieu de mémoire typically condenses a maximum of historical meanings and evocations into a single symbolic unit.) What nineteenth-century historicism brought back to life, that past ‘on its own terms’ as it was actually experienced, was not necessarily the past that was demonstrably, archivally factual. What was resuscitated was in many cases a legendary past, and those legends and myths are, as we have seen, fluid in their provenance. They can be medieval, recently invented, or somewhere between the two (heavily reworked, or elaborated with additional incidents, side characters or episodes).10

The legends that appealed to the taste of Romantic historicism often negotiated the borderline between life, death and afterlife. Prevalent tropes were the ‘last of the race’ (Ossian’s successors include Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans and Scott’s Last Minstrel11), and the ‘pagan princess at the dawn of history’ – for example Libuše. Her legend was known from medieval sources even before the discovery of the forged manuscripts and had been given literary treatment, initially by German Romantics (Brentano, Die Gründung Prags, 1812; Grillparzer, Libussa, 1844). After 1848, she was reappropriated by the Czechs with a vengeance. Smetana’s opera Libuše, used to celebrate the opening of Prague’s opera house in 1881, culminates in her foretelling of Prague’s greatness and has become the Czech national opera. The figure of Libuše became a favourite for paintings, statues and tile tableaux, and as a national icon her ontological status (non-historical, legendary) does not make the slightest difference. What was operative was the combination of feminine grace and lofty symbolism. The national-Romantic imagination is full of female characters combining historical stature and maidenly charm. Scott’s heroine Flora MacIvor, ‘last of the Jacobites’, who beguiles Waverley with her Highland minstrelsy, is an example: that almost preternaturally alluring femme fatale with her harp at a wild waterfall, who is among the last diehard loyalists to support Bonnie Prince Charlie. The opera composer Bellini created the figure of Norma, a Gaulish priestess, depicted at the moment when Christianity was about to drive out paganism. The princess Bogomila in France Prešeren’s Baptism at the Savica is in a similar transitional position from paganism to Christianity, as is Libuše in Brentano’s Die Gründung Prags. We could add the Lithuanian Princess Birutė (last of the pagan priestess-princesses, again), the Polish princess Wanda, the proto-Dutch Batavian heroine of Hermingard van de Eikenterpen (by Aarnout Drost, 1832) and Amaya, last descendant of the tribal god Aitor, in Francisco Navarro Valloslada’s Amaya o los vascos en el siglo VIII (1879).12 Some of these are purely fictional creations (Norman, Flora MacIvor, Hermingard, the Ossianic prototype Malvina); the others are legendary figures, whose true rise to fame occurred when they were reworked by nineteenth-century Romantics. Many of them became the pagan patron saints of popular girls’ names: Aino in Finland, Milda in Lithuania, Wanda in Poland, Linda in Estonia, Maeve, Gráinne and Deirdre in Ireland, Angharad in Wales, Gudrun in Germany and its neighbouring countries, and even the Spanish-Argentinian name for the Falkland Islands, Las Malvinas: they all testify to the power of the past to re-enchant the present.

But the fact that this pattern was so obviously transnational and pan-European, like the influence of Scott or Romanticism itself, should not make us forget that the remembered past was always a specifically national past, a history dominated by the theme of the nation at crisis moments in its own particular existence. What Scott and the Romantic historians bequeathed to the succeeding generations was an overriding sense of history as, precisely, national history, recounted in episodes that were emblematic of the history of the nation’s own, distinct identity and character.

The Long Tail of the Historical Novel: Epic, Sentimental, Juvenile

The historical novel has been described as history faute de mieux – an ersatz history writing for situations where the real thing was not a feasible option, much like Scott’s Last Minstrel using ‘glowing thought’ to supplement the blanks in his memory. The novel could make up for gaps in the historical documentation with a fictional supplement, and as such was a particularly suitable stop-gap medium for scantily documented topics.13 This played into an interest in the medieval period, not only in long-standing sovereign states such as Holland, Portugal or France, but equally for countries such as Flanders, Poland and Hungary (and of course Scotland), now subordinate under a higher crown but keenly aware of their erstwhile feudal, chivalric autonomy.

Novelists in the Scott tradition from those countries did important memory work (history faute de mieux) to recall and celebrate former glories, and their novels have become enshrined in their nations’ literary histories. Like the Waverley novels, their evocations of the past became revered classics. Hendrik Conscience is proverbially known in Flanders as ‘the man who taught his nation to read’. His historical novels have all become formative launching pad for powerful lieux de mémoire. Public statues in Flemish cities commemorate the medieval heroes that his novels rendered famous: Breydel and De Koninck in Bruges, Artevelde in Ghent. Most importantly, Conscience’s evocation of the Battle of the Golden Spurs of 1302 rendered that Flemish victory over the French army at Courtrai a national high point par excellence; the heraldic emblem that furnished the novel’s title (De Leeuw van Vlaenderen, ‘The Lion of Flanders’) is now the official flag of the Flemish region in Belgium, a song of that title is the Flemish Community’s official anthem, and the battle’s date, 11 July, is now a Flemish feast day and an occasion for nationalist manifestations. Something similar (familiar to us nowadays from the movie Braveheart) was at work for Henryk Sienkiewicz’s evocation of the Battle of Grünwald, which forms the culmination point of his novel Krzyżaci (1900, ‘The Knights of the Cross’, i.e. the Teutonic Order). The novel evokes the long, bitter oppression inflicted by those feudal German tyrants until finally a glorious Polish-Lithuanian army defeats them in 1410. Much as Conscience’s novel was itself inspired by a huge, historical painting of the Battle of the Golden Spurs (by Gustaaf Wappers, 1836), so too Sienkiewicz’s novel was inspired by the vast history painting by Jan Matejko (1878). In another parallel to the Flemish case, the novel prepared the ground for turning the medieval battle into a galvanizing commemorative event. The 500-year commemoration in 1910 became a vast, fervently nationalistic festivity, followed by the erection of statues in diverse places and ultimately an equally fervent mass event at the next centenary in 2010. The other historical novels of Sienkiewicz (the ‘Trilogy’, 1884–1887, evoking the seventeenth-century wars against Cossacks, Swedes and Turks) remained fixed on school reading lists throughout the twentieth century.14

Conscience and Sienkiewicz (and the many other Scott adepts from Central Eastern Europe) diverged in one crucial aspect from their Scottish prototype. Scott was keenly aware of the ongoing dialectics of history and usually resolves the conflicts in his novels in a Hegelian type of ‘sublation’: the conflict, while being recalled and indeed enshrined, ensuring its availability for future recall, is at the same time seen as something that ultimately had to be overcome, with history providing a transcendence of the old enmities into a higher unity. (That is what the Hegelian term Aufhebung, sublation in its threefold meaning, stands for: to enshrine something for safe keeping; to abolish it as an active agency; and to lift it to a higher plane.) Ivanhoe marries his fair Saxon lady Rowena, but he will, as a courtier of the Plantagenet King Richard, be part of the merger of Saxon and Norman groups into a new, English identity. Waverley will marry Rose Bradwardine and, while wistfully mindful of the romantic memories of Flora and the Jacobite cause, point the way towards a viable Scottish participation in the United Kingdom. Scott personally helped perform that integration when he stage-managed the 1822 visit of George IV to the Scottish capital following his coronation. It was the first Hanoverian royal visit to Scotland, and there was a sense of awkwardness about the fraught historical relations between the Scots and the Four Georges. Walter Scott, entrusted with the organization of the event, sublated that tension by enshrining Highland culture into the very heart of the festivities, calling on all Highland chiefs to be present with all their traditional retinue and their accoutrements of kilts and bagpipes. Kilts and tartan (until then the uncouth dress of the delinquent, disaffected Highlanders, and frequently banned by law) were to be worn by the Edinburgh socialites as well, and even George himself was dressed up in that ultra-Scottish finery. It marked the beginning of the British royals’ love affair with Scotland and its Highland culture: young Queen Victoria, George’s successor, acquired Balmoral Castle around 1850, festooned it with neo-Gothic turrets and battlements, and turned it into a Romantic Highland theme park for the royal family.15

Scott, politically a conservative and no radical, opts for reconciliation between the parties whose historical conflicts he evokes. No such reconciliation can be found in Conscience or Sienkiewicz. For them, history is in the most fundamental sense unfinished business, and the ancestral battle against the oppressors is evoked to inspire its renewal in the present. Conscience concludes his Lion of Flanders with this clarion call to his readers: ‘You, O Fleming, who have been reading this book, reflect (considering the glorious deeds which it contains) what Flanders used to be, what it is now, and especially, what shall become of it if you should forget the sacred examples of your forefathers!’16 This is activist writing. Conscience’s book is one of the trigger moments of the Flemish national movement, which came to see modern-day Belgium as a re-run of the medieval conflict between freedom-loving Flemish burghers and a haughty French (or French-speaking) elite. No sense of letting bygones be bygones, or moving on from the past: the past, on the contrary, is held up as an enduring model for the present, and the modern, novelistic side of Scott is abandoned for blood-and-guts epic. We have in Chapter 4 seen newly produced epic poems by Romantics such as Prešeren, Mickiewicz or Shevchenko complementing the ancient ones that had been philologically retrieved from oblivion or noted down by folklorists from oral-traditional performers. To that mix we can now add a third element: the historical novel-as-epic, prose fictions of ancient battles and heroism. The epic-heroic past as an inspiration for modern nationalism: that ran directly counter to what Scott had intended to achieve with his work, and it threw a long shadow over the twentieth century. In Slovenia in 2014, the controversial politician Janez Janša (his chequered career is a matter of record, as is his sympathy with far-right nationalism) published a historical romance Beli panter (‘The White Panther’) charting the mythical-heroic rise of a primordial Slovenian state, ‘revealing the secret of the Slovenes’ ethnic origins’. In 2021 Janša, back in power as Prime Minister after a spell in jail, was reported as using the panther symbol, which by then had become a trademark of extreme far-right groups in Slovenia, as a national ‘brand’ on cufflinks to be given out as diplomatic presents during the country’s tenure of the EU presidency.17

Janša’s ‘White Panther’ is closer to pulp fiction, closer to epic fantasy such as Conan the Barbarian or Game of Thrones, than to Waverley; it lacks any of the novelistic subtlety of Scott, or of Scott’s successors in the literary genre of the historical novel (Manzoni, Tolstoy, Eco, Ghosh). If one were to point out a more congenial model, it would be Felix Dahn’s Ein Kampf um Rom (1876), set among the Ostrogothic tribal kingdoms of Italy during the migration period, epic-heroic in spirit and breathing a fervent Germanic ethnic nationalism. The author was a highly regarded historian of the migration period, a leading academic, popularizer of Germanic myth, nationalist versifier and founding member of the völkisch Alldeutscher Verband. Ein Kampf um Rom became successful mainly as a juvenile novel, avidly read by adolescent and young-adult boys, many of whom would carry the Ostrogothic warrior ethic of Dahn’s book into their post-1918 political careers.18

This appeal to young readers signals another mutation of the historical novel in its post-Scott afterlife. Its demise as a prestigious literary genre was repeatedly announced, and its dominance in the literary field was taken over by realistic and naturalistic novels set in the here-and-now; but the genre continued its tenacious existence in the margins of the literary marketplace, in unprestigious writing aimed at unprestigious readers such as women and boys.19

For women, there were ‘bodice-rippers’ from Georgette Heyer to the Angélique series by Serge and Anne Golon, reverting back firmly from the register of the novel to that of the romance. The light-entertainment historical romance, targeted specifically at female readers, still thrives, a prominent example being the Scott- (or at least Scottish-) inspired Outlander series by Diana Gabaldon. This feminine inflection of the historical novel tends to eschew national/patriotic affect, and significantly its locations and settings are less fixated on the author’s or reader’s own nationality – witness the many romancified recyclings of Jane Austen as rom-com costume drama, even in Californian or Indian settings, or the cheerfully heedless counterfactuality of Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton romances (2000–2006) in their multiracially cast Netflix adaptation. Worthy of mention also is the remarkable genre of high-gloss romance featuring (historical) female royals as protagonists. The identificatory frame is largely that of gender, with a national-patriotic element being at best in the ambient background. At most, the historical-Romantic treatment of Queen Louise of Prussia and Empress-Queen Elisabeth of Austria-Hungary (Sissi) has played on their nationally inspirational value for their German and Austro-Hungarian subjects; but within Europe the genre on the whole tends to play into the monarchy as a glamorous institution rather than the nation as a political motivator.20

For boys, historical fiction was continued in an altogether more heroic and national vein. In the wake of Robert Louis Stevenson (Kidnapped, 1886; The Black Arrow, 1888) many adventure romances were set in the exciting glory days of the national past featuring increasingly juvenile heroes. The masculinity code for such boy-heroes firmly echoed the pedagogy of ‘pluck’, cheerful optimism and undaunted self-discipline, which would later find its most potent expressions in Rudyard Kipling’s Kim (1901) and the Boy Scout movement partly inspired by that book. G. A. Henty (1832–1902) has become proverbial as an author for nationalist (or rather, imperialist) boys’ fiction in English; his titles total well over 100 and range from The Young Buglers, A Tale of the Peninsular War (1880) to By Conduct and Courage: A Story of Nelson’s Days (1905). In the Netherlands, there were tales of young boys joining the celebrated nation-building seamen of the ‘Golden Age’ as shipmates.21 How tenacious this ethos was became clear in a parliamentary exchange in 2006 when the centre-right prime minister of the Netherlands, Jan-Peter Balkenende, championed a can-do mentality that he called a VOC-mentaliteit, an ‘attitude like that of the East India Company’: ‘I fail to see why you are being so negative. Let’s take heart from each other! Let’s be optimistic! Let us say: Holland can do it again! That VOC mentality, looking beyond our frontiers, dynamism. No?!’22 To invoke that colonial trading company as a role model was, to say the least, awkward; the incident has become notorious. The Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC, United East India Company, founded in 1602) had been the main entrepreneurial driving force in the establishment of Holland’s colonial empire and had helped finance the country’s war of independence against Spain. While its track record is now seen to have been mired in violent conquests, slave labour and slave trade, and a ruthlessly oppressive extractive economic colonial system, it was, during the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth (when colonialism was nothing to be ashamed of), a proud symbol of the country’s political and economic rise to power – its so-called Golden Century. This is the memory that obviously came through here: a belated echo of Balkenende’s conservative Protestant upbringing in the 1960s, when songbooks and juvenile fiction still unproblematically, unpolitically extolled the stalwart masculinity of colonial seafarers.

Besides the material aiming to instil a spirit of feisty, patriotic masculinity in the boys of the nation, there were also historical novels that had initially been targeted at an adult readership but that became, in the course of their subsequent career, juvenile or school reading. Besides Dahn, Scott and Sienkiewicz, this juvenile retargeting is also noticeable in Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. We shall note in Chapter 12 how historical fiction post-Scott was also given a fresh lease of life in cinematic form. All this helped to maintain historical fiction as a powerful and popular frame for bringing the past (and by default that meant the national past) to life as an immersive and inspiring environment.Footnote *

National History, National-Historical Myths, National Memory

Scott had shown the historians of this generation how to turn away from the palace-and-battlefield focus of earlier practitioners. Antiquarians had always been more inclusive in their interests: anything that might illustrate ancestral manners and customs was grist to their mill. That more societal focus was now also becoming the primary concern of historians; but what we would call ‘society’ they called ‘the nation’. Not kings or generals, but the nation was the main actor in their narratives (as indeed it was for Scott, although he used fictional protagonists as proxies through which to focus the collective experience of ‘national’ crisis moments).

Friedrich Schlegel had, earlier in the century, seen philology as a twin specialism to Völkergeschichte, the history of peoples. He used that term still in an older sense, to refer to pre-state antiquity studied in a wide geographical ambit. The implied notion of Volk became more focused when the historian Leopold von Ranke applied it. His main analytical frame for the European past was the contentious coexistence of two ethnocultural spheres that he identified in his Geschichten der germanischen und romanischen Völker of 1824. Jacob Grimm echoed Ranke’s view in his 1844 account of a voyage to early-Risorgimento Italy:

All of Europe consists of only two Völker, Germans and Italians, whose external powers had been sundered from the earliest time on. The reasons for that split must be sought directly in their nature and temperament [Sinnesart] as well as in their history. … These two Völker, whose destinies have been so tightly entwined, have long harmed one another, and the two now need to reconcile.23

As we saw in Chapter 6, Völkergeschichte was used by Arndt and Grimm to vindicate German claims on disputed borderlands, notably Schleswig-Holstein and Alsace, but also the Low Countries. It was philologically and archaeologically argued that at some point in history those territories had been settled by populations whose language or ethnicity could be qualified as Germanic. That in turn was invoked as scientific proof that the areas in question should legitimately be reunited with Germany (or annexed by it, as would be the fate of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871; see Chapter 11).

‘Ethnohistory’ was more generally widespread. Everywhere, history was focused on the nation (an ethnic community) as the experiencing subject of temporal change, rather than on states or institutions. Scott himself had set the tone in Ivanhoe, which saw medieval English history as a long ethnic conflict between Saxons and Normans. Ivanhoe’s Europe-wide fame ensured that this ethnohistorical frame was adopted in other countries as well: the Scott fan Augustin Thierry applied it to France, which he saw as the battleground between Gaulish, Roman and Frankish ethnic traditions (Lettres sur l’histoire de France, 1827) – to the point even that cranial measurements were taken to see which ‘race’ had left its traces where in the nation’s past. Taking Thierry’s cue, the Belgian Flemish historian Joseph Kervyn de Lettenhove traced a long ethnic struggle between the Flemings and their neighbouring French-francophone hegemons (Histoire de Flandre, 1847–1850). Although Thierry and Kervyn influenced later popularizing raconteurs such as Henri Martin (Histoire de France, 1833–1883), Eugène Sue (Les mystères du peuple, 1849–1856) and Hendrik Conscience (De Kerels van Vlaanderen, 1870), this type of ethnohistory drifted away from the academically professionalizing historical discipline after 1850.

As history becomes, almost by default, national history, the nation as seen by historians both enacts and experiences the challenges of the changing times. Wars, catastrophes and revolutions are described as affecting the national collective; defeats in war are described as national tragedies, victories as glories that the entire nation can rejoice in. More than that: since historians usually narrate the history of their own nation, the collectivity of the nation unites both the nation in the past and the nation in the present – the historian’s readership, that is. Readers are meant to identify with the nation whose past tragedies and triumphs are being held up to them. Libuše speaks to modern Czechs. Michelet, after relating a key moment of the French Revolution (the abolition of feudalism and estate privileges on 4 August 1789), cannot help himself from exclaiming ‘Vive la France!’ – like Madeleine Lebeau in Casablanca a century later.

The night grew late, it was two o’clock. That night took away the immense and painful spell of the Middle Ages. The approaching dawn was that of liberty. After that marvellous night there were no more classes, but French people; no more provinces, but one France. Vive la France!24

There is a civic pedagogy at work here. In narrating to their readers the glories and tragedies of their ancestors, historians became instructors of the public concerning what was now their history, enacted and experienced by their ancestors. The opening phrase of the French schoolbook, evoking ‘Nos ancêtres les Gaulois’ à la Henri Martin and Ernest Lavisse, has become proverbial in this respect (to the point of being gently lampooned at the opening of each Astérix album). The educational implications of this shift came soon enough: history was made a school subject in most European countries in the course of the nineteenth century, and it was aimed specifically at instilling in young pupils a sense of moral-cum-civic identification with the fatherland.

As national history was given a place in school curricula, university departments now had the task of training not only young historians in the craft of archival fieldwork and source criticism, but also future history teachers at secondary and primary schools, and inspiring or helping to prepare the textbooks that were to be used at those schools. Historians became public intellectuals and opinion leaders, even maîtres à penser – witness the tumultuous scenes around Michelet at the Collège de France on the eve of the 1848 revolution. Many a historian became a ‘nation-builder’, such as Alexandre Herculano in Portugal or František Palacký in Bohemia. In Ireland, the most vehement ideological battles were fought over the past, with poets and activists (Tom Moore, Thomas Davis, John Mitchel) writing fiery anti-English popular histories in the teeth of the professional and professorial mainstream. In the Netherlands, conflicting Protestant and Catholic interpretations of the revolt against Spain led to confessional frictions. This friction intensified as the events of that revolt, which had unfolded in the 1570s and 1580s, were commemorated on their successive tercentenaries in the 1870s and 1880s. The battle over the moral meaning of the foundational Dutch Revolt for the present Netherlands fed into the establishment of separate school systems for the country’s different denominations and a deep societal split along confessional lines that lasted into the 1950s. The past mattered.25

The outreach of Romantic history writing was noticeable everywhere. Commemorative events and public holidays, the placement and presence of public statues, the historical branding and ornamentation of public spaces (indoors and outdoors) in statuary, tile tableaux, reliefs, murals and paintings, not to mention street names: all of this drew on the colourful, immersive stories of the past that historians had learned to narrate and evoke – indeed, had brought to life, and with a vengeance – in the wake of Sir Walter Scott.

To be sure, the literary influence of Scott was on the wane. The canonicity of Scott was frequently asserted to be a thing of the past, but the decline was in fact much slower than those who tried to ‘get over Walter Scott’ would like to believe. Scott’s afterlives lingered tenaciously in odd corners of the cultural field: tourism, historical re-enactment, the ambient taste for Romantic historicism as it percolated into the decorative arts, product design and popular culture. The historical novel lost its literary primacy but seeded traces of Romantic historicism all over the public spaces of Europe.26

Historians, too, tried to ‘get over Scott’. They came to disavow their envy of Scott’s narrative and evocative powers, and indeed disavowed Romantic history writing altogether. Figures such as Michelet and Thierry, Palacký and Herculano, became a bit of an embarrassment for their successors, were considered mere littérateurs rather than proper ‘serious historians’. The real, ‘serious’ historians were now embarked on a rapid process of academic professionalization, consolidated into university departments, and developed a professional ethos privileging archival (unpublished) sources. As the archives themselves became state-curated records of public policies, historians became state historians, or else social historians, rather than the ‘national historians’ they had been heretofore – they chose to be ‘national’ no longer, either in their working frame or in their audience appeal. Post-Romantic historians mistrusted the rhetoric and enthusiasm, and indeed the entire taste for drama or narrativity, that had characterized the Romantic generation, and they pursued their professionalism in austere factualism, in quantitative methods in the mode of the developing science of sociology, and in debunking the over-interpretations of their immediate forerunners. A positivistic professional ethos of anti-enthusiasm set in, and a distrust of appearances and generalizations took hold of the profession. This positivistic habitus has continued to dominate history departments, although leftist historians have returned to a Romantic sense of empathy when describing the historical struggles of class, race, gender and other subaltern identities.

That shift towards scientism, positivism and factualism, and away from pathos, imagination and narrativity, occurred in the second half of the nineteenth century; it was marked by books such as Louis Bourdeau’s L’histoire et les historiens: Essai critique sur l’histoire considérée comme science positive (1888). Ranke’s historicism now hardened into a precept of dispassionate exactitude and strict reliance on attested facts. The narrative evocation of ‘the story of the nation’ was left to popularizers and school textbooks. These were usually not based on fresh archival research and hence failed to qualify as serious history writing, instead seen as recycling yesterday’s news. But while they were ignored by the historical profession, they kept the Romantic legacy alive among the public at large. Michelet, Palacký and Mitchel were reprinted in popular editions, as was Walter Scott, throughout the century and beyond, while the historical profession began to publish more and more for an academic peer group. Writing history for a larger or indeed ‘national’ audience was, at best, popularization. Historians claiming to be both professional and ‘national’, such as Treitschke, would pursue the latter role in their journalistic and controversial writings, as public intellectuals, rather than in their historiography.

In this development towards academic professionalization, historians lost their grip on the public imagination, and the public imagination continued to feel the allure of the Romantics. This was in part because Romantic history writing had broadcast and canonized stirring, heroic episodes of the past: things that became, properly speaking, myths – in the common modern sense of that word. These were key episodes from the nation’s history, frequently retold, widely remediated into visual imagery, into popular landmarks and narratives. The German landscape in the course of the century became dotted with huge monuments that as tourist attractions kept the myths of their dedicatees alive: the huge Arminius monument near Detmold recalling the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, the equally huge Kyffhäuser monument recalling the myth of Barbarossa as the Once and Future German emperor, Cologne Cathedral as a monument to the continuity from the medieval to the modern Empire.27 France had its walk-in history book in the Panthéon, with its statues, murals and graves, the many landmarks restored by Viollet-le-Duc, Napoleon’s tomb in the Invalides and the many, many statues of Joan of Arc. Here and there tourists could visit in-the-round panorama paintings recalling the heroic occasions of glorious battles: Waterloo, Sebastopol, the arrival of the Magyars in Hungary.28 The Netherlands combined feudal-medieval and seventeenth-century bourgeois cultural history in its Muiderslot near Amsterdam. The Risorgimento told its story in the gigantic monument to Vittorio Emmanuele in central Rome. And so on, and so on. With all those landmarks and tourist attractions dotting the landscape, the narrative highlights of national history – national myths – had solidified themselves in the public mind without needing to rely on the archival research or textual production of card-carrying historians.

It is difficult to think of post-Romantic academic historians enjoying the same cultural stature as their Romantic forerunners – Michelet, Alexandre Herculano, František Palacký, Carlo Cattaneo, Alexandros Rangavis or Joachim Lelewel. Indeed, all the scholarly corrections made by professional academic historians on the basis of painstaking archival research failed to inspire or even instruct the public at large to the same extent as their heedlessly Romantic predecessors had done in their own, almost literary writings or through their general culture-historicist outreach. Indeed, as academic historians introduced non-national topics into school curricula after 1945 (world history, social and economic history) those changes provoked a slow-burning backlash. National feeling had placed national history on school curricula in the 1850s, and history could not discard national feeling with impunity in the 1980s. Policy makers and public intellectuals at the national conservative end of the political spectrum periodically issued calls to bring national narrative historicism back into the school curricula. The UK prime minister John Major stressed the importance of teaching Shakespeare; Michael Gove, a British Conservative politician, spoke as follows at the Conservative party Conference of 2010:

One of the under-appreciated tragedies of our time has been the sundering of our society from its past. Children are growing up ignorant of one of the most inspiring stories I know – the history of our United Kingdom. Our history has moments of pride, and shame, but unless we fully understand the struggles of the past we will not properly value the liberties of the present. The current approach we have to history denies children the opportunity to hear our island story. Children are given a mix of topics at primary, a cursory run through Henry VIII and Hitler at secondary and many give up the subject at 14, without knowing how the vivid episodes of our past become a connected narrative. Well, this trashing of our past has to stop.29

In the Netherlands, a National Canon was drawn up in 2006, and a National History Museum proposed, with the avowed aim to bring society together around a shared set of narratives. A similar canon had been drawn up in Denmark; Flanders followed suit in 2021. Although academics were involved in the canons’ elaboration, many professional historians voiced reservations.30 There were flanking initiatives to recycle and publicize this new national historicism. In Denmark, the Netherlands and Flanders (the three countries that had defined national canons), there were television series (Historien om Danmark, 2017; Het verhaal van Nederland, 2022; Het verhaal van Vlaanderen, 2023) with explicitly national-narrative titles and, in Flanders, a nationalist conservative politician endorsing ‘the logic of promoting Flemish identity’.31 Public and commercial media such as cinema, television and musicals have since 2000 continued to recycle canonical national figures. Quiz election shows on ‘the nation’s greatest figure in history’ were held in many European countries: in the UK (2002, ‘100 Greatest Britons’), in Germany (2003, ‘Die größten Deutschen’), in Finland and the Netherlands (2004, ‘Suuret suomalaiset’ and ‘De grootste Nederlander’), in Portugal (2007, ‘Os grandes portugueses’), in Greece (2009, ‘Megali Ellines’), and in Italy (2010, ‘Il più grande italiano di tutti i tempi’).

What fed that populist mass-media historicism? The answer must be sought in the lingering legacy of Romanticism. The Romantics, obsolete among their professional successors, continued to be read as littérateurs, and their thrilling narratives could continue to be reworked: not only in middlebrow historical fiction and tourist landmarks, but also in the decorative arts that proliferated across cities’ public spaces in the second half of the nineteenth century to leave nostalgic traces deep into the twentieth. The historical murals that embellished the interiors of Europe’s great public and historical buildings all depicted narrative episodes rendered famous in the Romantic national histories of the early part of the century. Schoolrooms in the Netherlands and other countries had been decorated with colourful lithographed posters: cheap, portable murals, intended to render the national histories taught in the classroom more vividly imaginable. Patriotic songs cherished the memories of the key scenes and actors of Romantic-historical vintage. And as soon as new media cropped up, these activated that same old repertoire of nationally canonical figures and episodes, the canonicty of which has been established by those Romantic historians now dismissed by their academic successors. New media: book illustrations and the revived art of the mural; grand opera (I Lombardi, Les vêpres siciliennes, Libuše); decorated household ware (Figure 7.2); waxworks; panoramas; and, as the century drew to a close, film, to be followed in the twentieth century by TV serials, musicals, graphic novels, re-enactment societies and theme parks.

Figure 7.2 Memory into memorabilia: souvenirs in the tourist gift shop at the Regensburg Walhalla; the Walhalla was established in 1842 by the Bavarian king Ludwig I to honour ‘great historical personalities of the German nation’.

Thanks to this widely diffused presence, the ingrained repertoire of the nation’s history and heroes is both canonical and banal. Firmly Romantic in rhetoric and provenance, it has remained solidly part of a generalized cultural memory and continues to underpin a historicist sense of the nation’s inner authenticity and outer distinctness. Under the twin pressures of international entanglement and demographic multiculturalization, that national-historical repertoire seems to be used increasingly as part of a nativist political agenda: the nation, following Michael Gove’s ideal, as having an internally connected narrative and being externally an island.

In recent years we have tended to twin the concepts of history and memory. How the two relate to each other is a complex and interesting question; but the two both belong to a wider sense of history, memorably defined by Johan Huizinga as the ‘mental form in which a cultural community takes account of its past’. Within that wider field of ‘taking account of the past’, the term ‘history’ has been given a more restricted, professional meaning as ‘history proper’, as it is studied by academics in university departments, and with a gravitation towards the archive-based investigation of political and social topics. There, the legacy of Romantic historicism has been put aside. But there are other ways of taking account of the past: outside the university, people recall the past on the basis of what they encounter informally in the field of culture or what they remember from hearsay. All that gravitates towards a field now usually seen as collective or cultural memory. In that bifurcation between history and memory, the national narratives of Romantic vintage were abandoned by ‘history proper’ but continued in force as an informing presence in memory.32