Introduction

Crystallisation of minerals from a granitic magma buffer the activities of individual elements and progressively modifies the composition of residual fractions of the magma, thereby facilitating conditions suitable for the formation of subsequent minerals. Tourmaline is an excellent example showing that crystallisation of feldspars, quartz and other B-incompatible minerals in granitic magmas increases concentrations of B in a melt and allows crystallisation of tourmaline (London, Reference London2008). This process also commonly controls the excess of Al, which is essential for the saturation of tourmaline and other peraluminous minerals such as andalusite and cordierite.

Beryllium forms a very distinctive cation due to its strong incompatibility with major and most minor and accessory minerals resulting from the small ionic size and low charge of Be2+. This facilitates the formation of a large suite of Be minerals (Hawthorne and Huminicki, Reference Hawthorne, Huminicki and Grew2002; Grew and Hazen, Reference Grew and Hazen2014). These minerals originate during magmatic, metamorphic and hydrothermal processes over a wide range of P–T–X conditions and in diverse geological environments (Grew, Reference Grew and Grew2002; Barton and Young, Reference Barton, Young and Grew2002; Černý, Reference Černý and Grew2002; London and Evensen, Reference London, Evensen and Grew2002). Because externally imposed chemical potentials govern the stability of Be minerals (Barton, Reference Barton1986), they serve as sensible geochemical mineral indicators (Burt, Reference Burt1978; Markl and Schumacher, Reference Markl and Schumacher1997; Markl, Reference Markl2001; Černý, Reference Černý and Grew2002; Barton and Young, Reference Barton, Young and Grew2002; Franz and Morteani, Reference Franz, Morteani and Grew2002; Uher et al., Reference Uher, Chudík, Bačík, Vaculovič and Galiová2010; Novák et al., Reference Novák, Dolníček, Zachař, Gadas, Nepejchal, Sobek, Škoda and Vrtiška2023; Chládek et al., Reference Chládek, Novák, Uher, Gadas, Matýsek, Bačík and Škoda2024).

Beryllium minerals are typical minor to rare accessory phases in a variety of rocks. They include granitic to alkaline pegmatites, granites and acidic volcanic rocks, skarns, metamorphic rocks and hydrothermal veins (Martin-Izard et al., 1995; Grew, Reference Grew and Grew2002; Barton and Young, Reference Barton, Young and Grew2002; Downes and Bevan, Reference Downes and Bevan2002; Merino et al., Reference Merino, Villaseca, Orejana and Jeffries2013; Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Rao, Wang, Che, Wang, Wu, Wang and Huang2023; Chládek et al., Reference Chládek, Novák, Uher, Gadas, Matýsek, Bačík and Škoda2024). However, they occur mainly in granitic pegmatites of almost all of the classes/types as defined by Černý and Ercit (Reference Ercit2005), from abyssal (anatectic) pegmatites (Grew et al., Reference Grew, McGee, Yates, Peacor, Rouse, Huijsmans, Shearer, Wiedenbeck, Thost and Su1998; Grew, Reference Grew1998, Reference Grew and Grew2002; Cempírek and Novák, Reference Cempírek and Novák2006; Cempírek et al., Reference Cempírek, Novák, Dolníček, Kotková and Škoda2010) to rare-element pegmatites and miarolitic pegmatites of the LCT and NYF families, where beryl is by far the most abundant primary Be mineral (Černý, Reference Černý and Grew2002; London, Reference London2008; Wise et al., Reference Wise, Müller and Simmons2022). Minor to very rare primary Be minerals in granitic pegmatites, locally associated closely with beryl include: phenakite; chrysoberyl; helvine- and gadolinite-group minerals; rhodizite–londonite series; hurlbutite; beryllonite; hambergite (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Burns and Morgan1998; Černý, Reference Černý and Grew2002); and milarite-group minerals (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Cícha, Čopjaková, Škoda and Galiová2017).

Beryllium is highly incompatible in tourmaline, as is shown by very low concentrations of Be, typically ∼10 ppm only exceptionally are contents ≤ 76 ppm (Ertl et al., Reference Ertl, Henry and Tillmanns2018). In tourmaline from the Třebíč Pluton pegmatites (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011), the Be content is ≤ 31 ppm. Hence, the effect on the concentration of Be in a parental highly volatile-rich melt after its crystallisation is negligible. Tourmaline commonly accompany beryl in typically peraluminous granitic pegmatites; however, explicit genetic relationships between primary Be minerals, mostly beryl, and associated tourmaline have only rarely been reported. Such relationships in metaluminous pegmatites have been documented even less commonly (Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020).

Intra-granitic pegmatites of the euxenite-type from the Třebíč Pluton in the Moldanubian Zone represent a specific type of NYF-related pegmatite, derived from a Mg-rich ultrapotassic I-type orogenic pluton (von Raumer et al., Reference von Raumer, Finger, Veselá and Stampfli2014; Leichmann et al., Reference Leichmann, Gnojek, Novák, Sedlák and Houzar2017; Janoušek et al., Reference Janoušek, Holub, Verner, Čopjaková, Gerdes, Hora, Košler and Tyrrell2019, Reference Janoušek, Hanžl, Svojtka, Hora, Kochergina Erban, Gadas, Holub, Gerdes, Verner, Hrdličková, Daly and Buriánek2020; Kubeš et al., Reference Kubeš, Leichmann, Buriánek, Holá, Navrátil, Scaillet and O’Sullivan2022). The pegmatites contain as major primary Be minerals: beryl; helvine–danalite; and less abundant phenakite (Staněk, Reference Staněk1973; Novák and Filip, Reference Novák and Filip2010; Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020). However, primary beryl and helvine–danalite have not been found within the same pegmatite body (Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020). Moreover, primary tourmaline is abundant in the helvine–danalite pegmatites but absent or very rare in the beryl pegmatites. We examined mineral assemblages, textural relations, and the composition of tourmaline and primary Be minerals to determine the effect of early tourmaline crystallisation on the concentrations of diverse elements, principally Al and Mn, and the significance of tourmaline crystallisation for the origin and composition of the later-formed primary Be minerals.

Geological setting

Třebíč Pluton

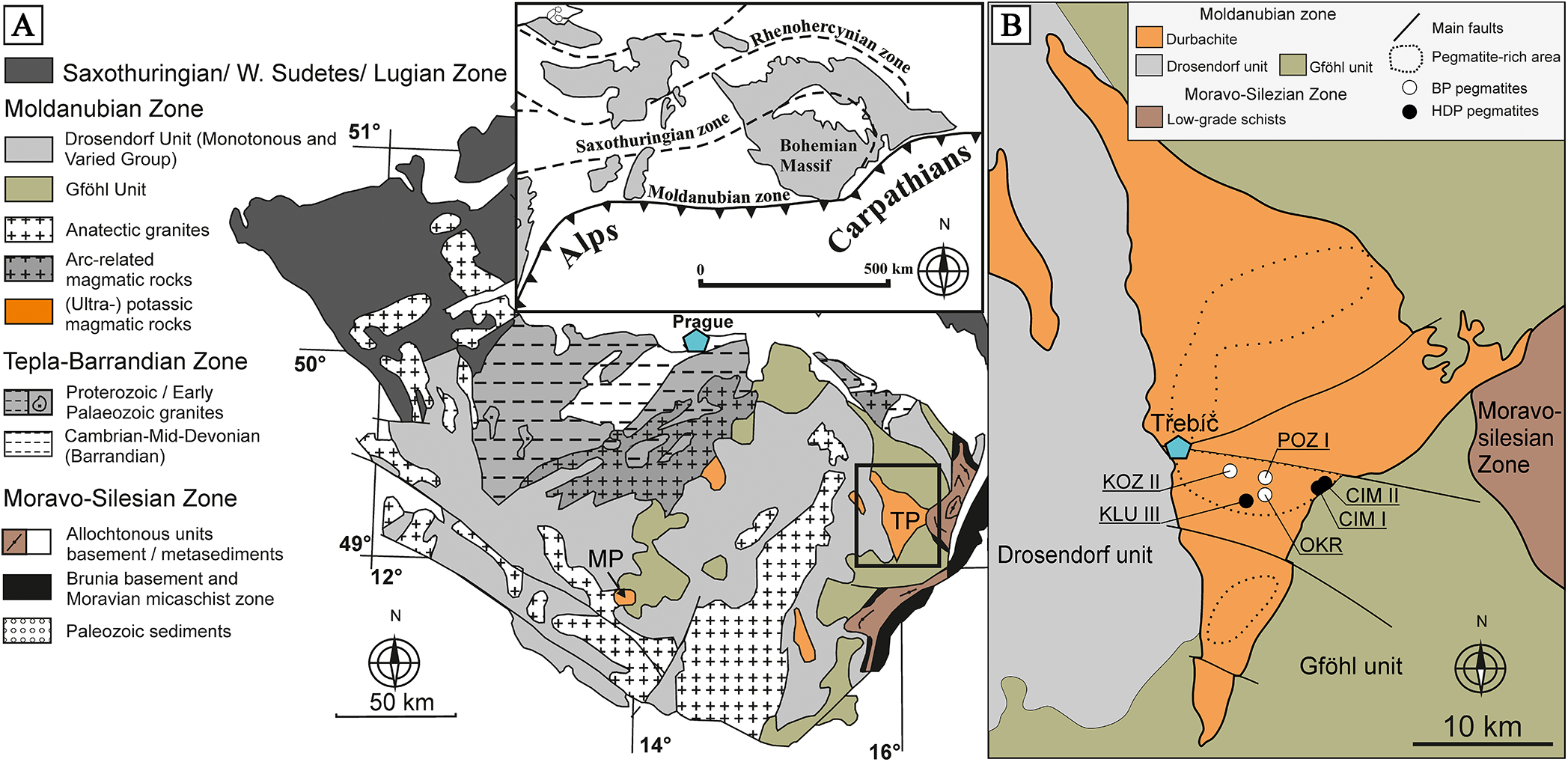

The Třebíč Pluton forms a large flat body in the eastern part of the Moldanubian Zone (Fig. 1; Leichmann et al., Reference Leichmann, Gnojek, Novák, Sedlák and Houzar2017; Kubeš et al., Reference Kubeš, Leichmann, Buriánek, Holá, Navrátil, Scaillet and O’Sullivan2022). It is of Variscan age (∼335 Ma) and consists of melagranite to melasyenite, commonly referred to as ‘durbachite’. This is dominantly coarse grained and composed of porphyritic orthoclase phenocrysts, Fe- and Ti-rich phlogopite, plagioclase (An8–40), amphibole (actinolite to rare magnesio-hornblende), and quartz in a mostly medium-grained matrix. Typical accessory minerals include fluorapatite, zircon, allanite-(Ce), titanite and sulfide minerals. The bulk composition is characterised by a metaluminous signature (ASI = 0.7–1.0), low to high SiO2 (52–69 wt.%), moderate Al2O3 (12.5–14.0 wt.%), moderate to high contents of K2O (5.2–7.0 wt.%), but rather low Na2O (1.4–2.5 wt.%), high to very high MgO (3.3–10.2 wt.%), moderate FeO (3.0–7.4 wt.%) and CaO (2.3–4.8 wt. %), high P2O5 (0.5–1.2 wt.%), Rb (330–460 ppm), Ba (1100–2470 ppm), U (7–26 ppm), Th (28–48 ppm), Cr (270–650 ppm), Cs (20–40 ppm), Be (6–9 ppm) and B (9–20 ppm). The origin of the ‘durbachite’ magma is interpreted as the result of the melting of mantle domains that were previously metasomatised by fluids derived from slabs of subducted continental crust (for more details, see Holub, Reference Holub1997; Janoušek et al., Reference Janoušek, Holub and Gerdes2003, Reference Janoušek, Hanžl, Svojtka, Hora, Kochergina Erban, Gadas, Holub, Gerdes, Verner, Hrdličková, Daly and Buriánek2020; Breiter, Reference Breiter2008; Kotková et al., Reference Kotková, Schaltegger and Leichmann2010; Kubeš et al., Reference Kubeš, Leichmann, Buriánek, Holá, Navrátil, Scaillet and O’Sullivan2022).

Figure 1. (A) Simplified geological map of the Moldanubian Zone, with an inset showing its position within the European Variscides, highlighting the ultrapotassic bodies mentioned in the text: TP – Třebíč Pluton and MP – Mehelník Pluton (modified after Schulmann et al., Reference Schulmann, Konopásek, Janoušek, Lexa, Lardeaux, Edel, Štípská and Ulrich2009). (B) Geological position of the studied pegmatites within the Třebíč Pluton.

Pegmatites

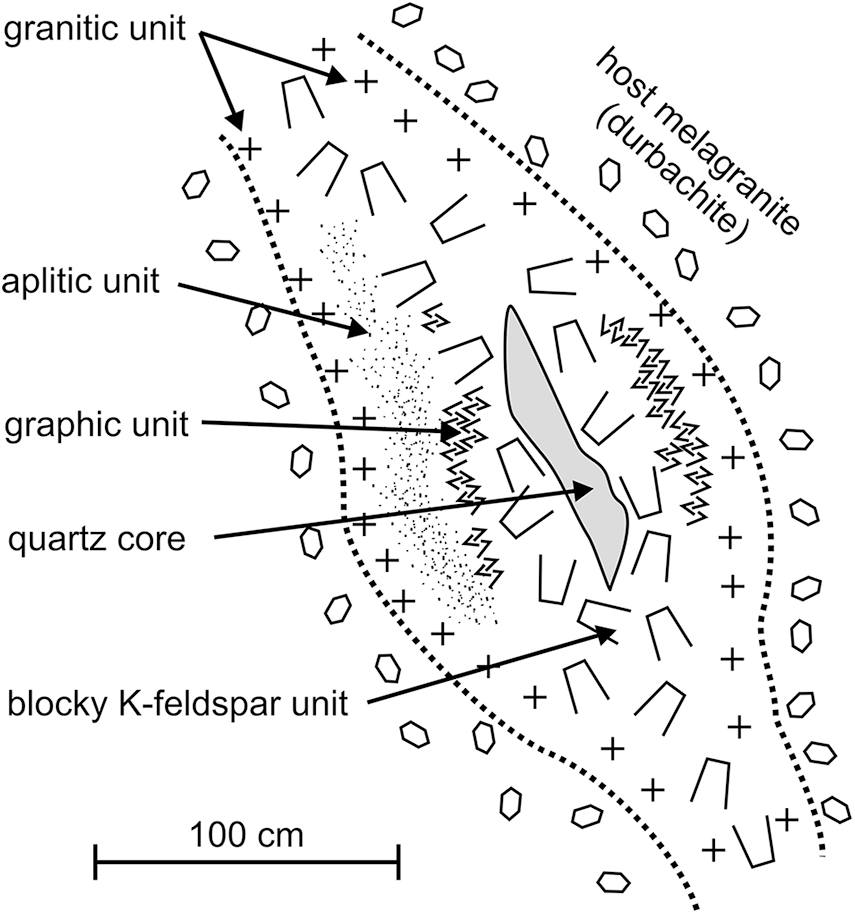

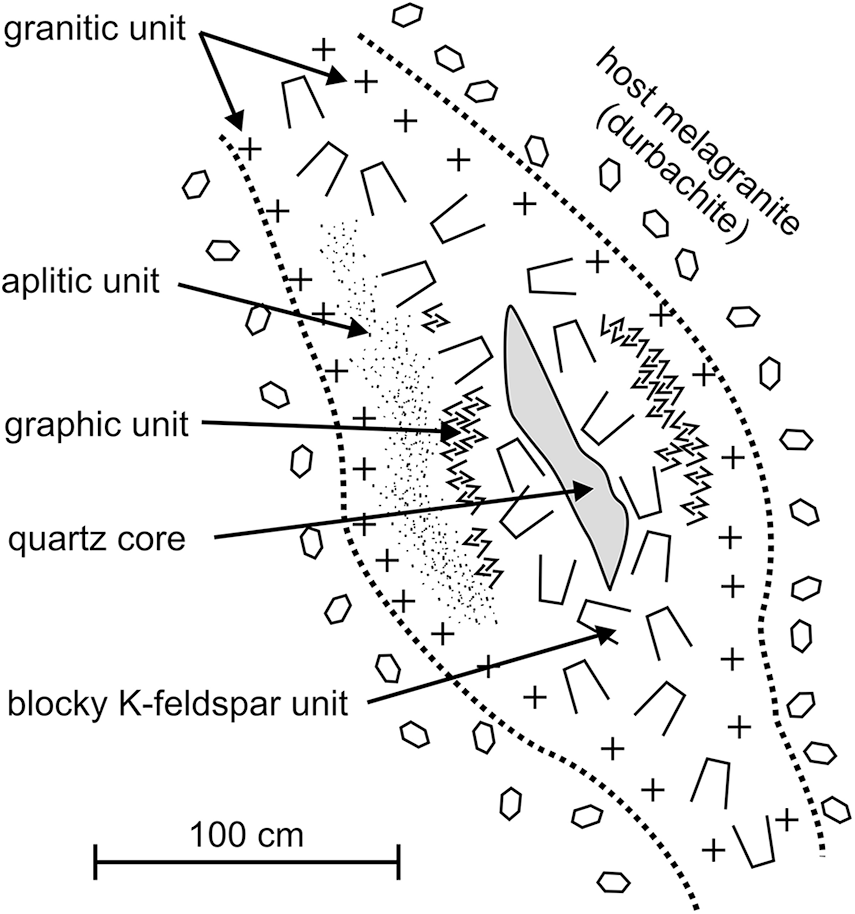

The intra-granitic pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton have been divided on the basis of their mineral assemblages, degree of geochemical fractionation and internal structure into: (i) geochemically primitive allanite-type pegmatites; and (ii) more evolved euxenite-type pegmatites (Škoda et al., Reference Škoda, Novák and Houzar2006; Škoda and Novák, Reference Škoda and Novák2007; Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Gadas, Krmíček and Černý2012; Zachař and Novák, Reference Zachař and Novák2013). The euxenite-type pegmatites correspond to the NYF family, the rare-element class and REL–REE subclass (Černý and Ercit, Reference Ercit2005). However, they are typically F-poor and locally B-rich and the rock-forming minerals commonly show a high Mg/Fe ratio; consequently, they do not entirely fit the definition of the NYF family (Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Hanson, Falster and Webber2012; Černý et al., Reference Černý, London and Novák2012). The zoned internal structure of the subvertical euxenite-type pegmatite dykes, 0.2–1.2 m in thickness, have typical textural-paragenetic units from the contact inwards of: a border zone of medium-to coarse-grained granitic unit with phlogopite ± actinolite); a graphic quartz–K-feldspar unit; a blocky K-feldspar unit (locally pale green amazonite); and a quartz core (Fig. 2). A medium- to coarse-grained albite unit is found locally in nests, up to ∼10 cm in diameter. Together with phlogopite, some pegmatites contain rare to minor black tourmaline (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011; Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013), and common to rare magmatic accessory minerals including: titanite; allanite-(Ce); ilmenite; (Nb-)rutile; zircon; REE,Nb,Ta,Ti-oxide minerals; pyrite; and arsenopyrite (Škoda and Čopjaková, Reference Škoda and Čopjaková2005; Škoda et al., Reference Škoda, Novák and Houzar2006; Škoda and Novák, Reference Škoda and Novák2007; Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013, Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová, Novák and Cempírek2015); as well as Be minerals (Staněk, Reference Staněk1973; Novák and Filip, Reference Novák and Filip2010; Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020); and Sc minerals (Výravský et al., Reference Výravský, Škoda and Novák2025).

Figure 2. Idealised cross-section of euxenite pegmatite from the Třebíč Pluton. Slightly modified from Škoda et al. (Reference Škoda, Novák and Houzar2006).

Compositions of the individual pegmatite units from several pegmatites in the Třebíč Pluton show high SiO2 (∼76–77 wt.%), moderate Al2O3 (∼13 wt.%), ASI = 1.02–1.09, dominance of K over Na (5.6–7.5 wt.% K2O and 2.6–3.3 wt.% Na2O), low MgO (0.07–0.24 wt.%), Fe2O3 (0.30–0.40 wt.%), CaO (0.10–0.78 wt.%) and very low P2O5 (0.02 wt.%), see Čopjaková et al., (Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013) for details. In comparison with the host durbachites, the trace-element concentrations of Rb (222–297 ppm), Ba (197–947 ppm), U (4–29 ppm), Th (15–32 ppm), Cs (20–40 ppm) and F (90–110 ppm) are lower, whereas Be (11–42 ppm) and B (24–68 ppm) are enriched (Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013). The pegmatites are strongly depleted in P, Mg, Fe and Ba, and enriched in Si, Be and B relative to the parental magmatic rock.

Mineral assemblages from the following pegmatites were studied: Okrašovice (OKR); Klučov III; Číměř I- II; Pozďátky I; and Kožichovice II.

Methods

Electron microprobe

The compositions of the minerals were determined using a Cameca SX100 electron microprobe in the Laboratory of Electron Microscopy and Microanalysis, Department of Geological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Masaryk University, Brno. Analyses were carried out in wavelength dispersive mode, with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV, a beam current of 10 nA and a spot size ∼5 μm. The following standards and X-ray Kα lines were used: sanidine (Si, Al, K); albite (Na); olivine (Mg); wollastonite (Ca); almandine (Fe); spessartine (Mn); fluorapatite (P); titanite (Ti); chromite (Cr); topaz (F); gahnite (Zn); SrSO4 (S); ScVO4 (V, Sc); synthetic Rb-silicate (Rb); and pollucite (Cs). The peak counting time was 10 s for major elements and 20–40 s for minor to trace elements. The background counting time was half of the peak counting time at the high- and low-energy background positions each. Raw intensities were corrected for matrix effects using the X-PHI algorithm (Merlet, Reference Merlet1994). The theoretical amount of unanalysed light elements (H, Be, B and O) was included in the matrix correction.

Raman spectroscopy

Selected Be- and B-bearing minerals analysed previously by electron microprobe were also investigated using a Labram HR Evolution Raman spectrometer connected to an Olympus BX41 microscope to confirm their structural characteristics. Spectra were excited using 473, 532, or 633 nm lasers and collected in the range of 100–4000 cm−1 with a 600 gr/mm grating, 50x objective, and a Peltier-cooled CCD detector.

Results

This study of primary Be minerals and their associated assemblages follows the previous investigations of Škoda et al. (Reference Škoda, Novák and Houzar2006), Škoda and Novák (Reference Škoda and Novák2007), Novák and Filip (Reference Novák and Filip2010), Zachař et al. (Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020) and Novák et al. (Reference Novák, Dolníček, Zachař, Gadas, Nepejchal, Sobek, Škoda and Vrtiška2023), which focused on the internal structure and geological position of the pegmatites, REE-oxide minerals, beryl and its breakdown products, and overall assemblages of Be minerals. Tourmaline compositions, textures and mineral assemblages have been examined in detail by Novák et al. (Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011) and Čopjaková et al. (Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013, Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová, Novák and Cempírek2015).

Mineral assemblages of the pegmatites

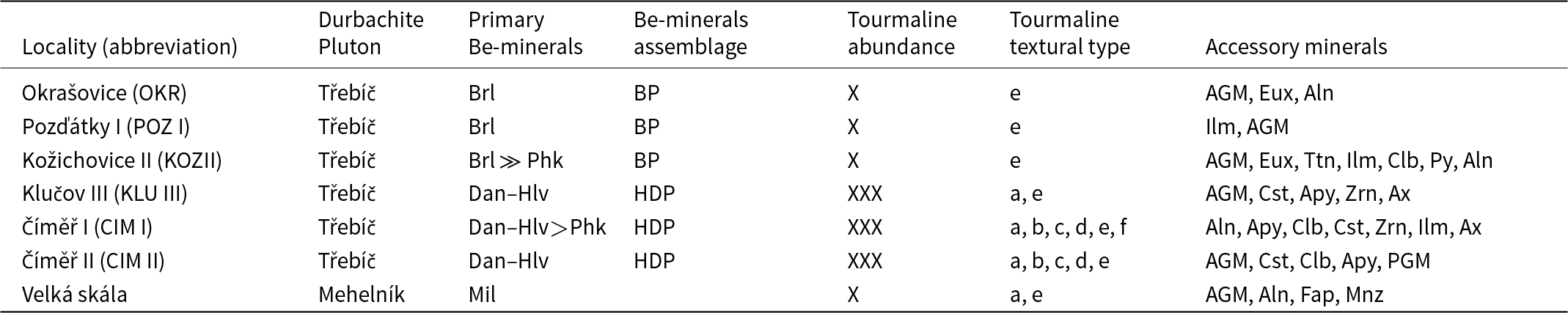

The primary Be minerals and their mineral assemblages are given in Table 1. The internal structure, shape and size of the pegmatite dykes is described above (for details see: Škoda et al., Reference Škoda, Novák and Houzar2006; Novák and Filip, Reference Novák and Filip2010; Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011; Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013; Zachař and Novák, Reference Zachař and Novák2013). Accessory REE,Nb,Ta,Ti-oxides including aeschynite-group minerals, euxenite-(Y) and allanite-(Ce) occur in the more evolved pegmatite dykes (Škoda and Novák, Reference Škoda and Novák2007) and are evidently more abundant than very rare columbite and (Nb-)rutile (Table 1). Titanite and ilmenite occur mainly in the pegmatites with scarce primary tourmaline, whereas rare primary Sn minerals (cassiterite, herzenbergite; Škoda and Čopjaková, Reference Škoda and Čopjaková2005) are typical for the most evolved, tourmaline-rich euxenite-type pegmatites (Číměř I, II, Klučov III). Fluorapatite, monazite-(Ce) and xenotime-(Y) are very rare (Table 1) and primary muscovite is absent (Škoda et al., Reference Škoda, Novák and Houzar2006; Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020), reflecting the low P content and low ASI in the melt, respectively.

Table 1. Mineral assemblages focused on primary Be minerals and textural types of tourmaline in the pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton

Notes: Textural-paragenetic types of tourmalines: (a) coarse- to medium-grained aggregates and prismatic crystals; (b) graphic intergrowths (Tur+Qz); (c) fine-grained nodules (Tur+Qz+Pl+Kfs); secondary and subsolidus; (d) tourmaline pseudomorphs after biotite; (e) interstitial tourmaline in thin fractures or intergranular spaces; (f) tourmaline replacing helvine-danalite.

Abbreviations: BP – beryl ± phenakite assemblage; HDP – helvine–danalite ± phenakite assemblage. Aln – allanite; Apy – arsenopyrite; Ax – axinite; Brl – beryl; Cst – cassiterite; Dan – danalite; Fap – fluorapatite; Hlv – helvine; Ilm – ilmenite; Mil – milarite; Mnz – monazite; Phk – phenakite; Py – pyrite; Ttn – titanite; Zrn – zircon; AGM – aeschynite-group minerals; Clb – columbite; Eux – euxenite-(Y); PGM – pyrochlore-group minerals. Mineral symbols taken from Warr (Reference Warr2021)

Tourmaline is a typical rare accessory to a minor phase in many pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011; Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013). It is usually very rare in pegmatites with common beryl, but abundant in helvine–danalite pegmatites (Table 1), as well as in some barren pegmatites. Abundance and textural types of tourmaline from the here described helvine–danalite pegmatites, are similar to those of the other tourmaline-rich euxenite-type pegmatites in this region (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011; Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013) and their composition is discussed in detail below.

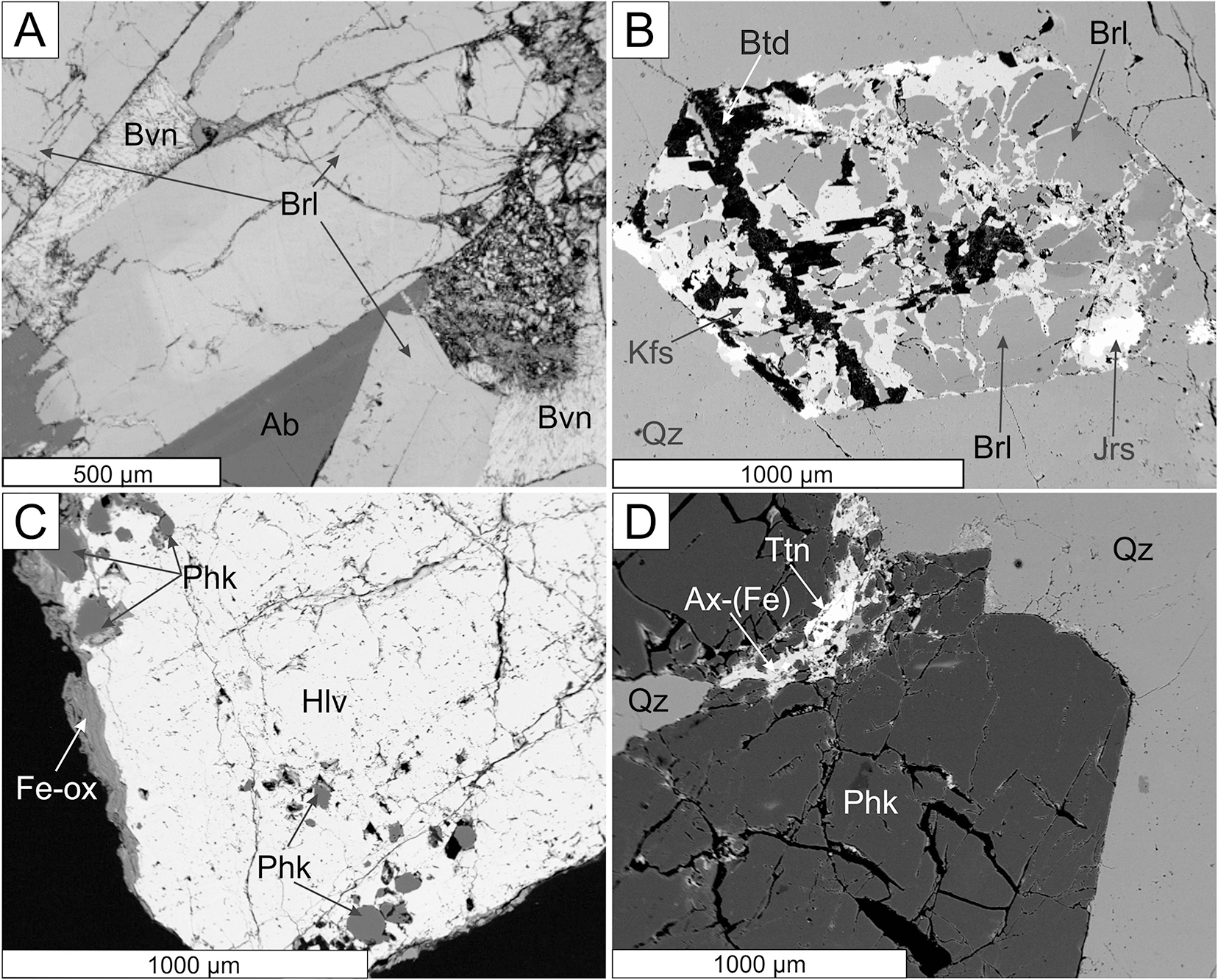

Mineral assemblages and composition of primary Be minerals

Primary Be minerals from the euxenite-type pegmatites (beryl ≈ helvine–danalite > phenakite; Table 1) were divided into two distinct assemblages (Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020): The assemblage BP (beryl ± phenakite) occurs in pegmatites with rare tourmaline, whereas the assemblage HDP (helvine–danalite ± phenakite) is typical for pegmatites with abundant tourmaline (Table 1). Primary Be minerals are commonly situated in central parts of the dykes in the coarse-grained blocky K-feldspar, massive quartz, graphic and albite unit. Pale green to yellowish prismatic crystals of beryl I, up to 5 cm in length and 5 mm in thickness, show well-developed compositional zoning in back-scattered electron (BSE) images and thin sections. Beryl is compositionally heterogeneous (Fig. 3a,b; Fig. 4a,b; Table 2), showing low and variable concentrations of Al (1.45–1.69 atoms per formula unit), substituted by Sc (<0.06 apfu), Mg (0.30–0.44 apfu; exceptionally only 0.13 apfu), Fetot (0.04–0.14; exceptionally 0.24 apfu), and channel constituents Na (0.20–0.34 apfu), Cs (<0.15 apfu), K (≤0.07 apfu) and Rb (≤0.01 apfu). The content of V ranges from 20 to 112 ppm, whereas Cr is below 5 ppm. For more details see Novák and Filip (Reference Novák and Filip2010). Evidently, less abundant long prismatic crystals, 2 cm × 0.5 cm in size, of colourless phenakite, are typically enclosed in quartz (Fig. 3d, Table 1). The composition of phenakite is very close to the ideal formula. Brown to brownish-red, Fe-rich helvine to Mn-rich danalite (Table 3) were found as subhedral to euhedral crystals, up to 5 cm in size, typically covered by black to brownish black coatings of Mn,Fe-oxides/hydroxides (Fig. 3c). They occur in coarse-grained pegmatite (blocky K-feldspar + Qz > Ab), and are also found rarely in the graphic unit (Kfs + Qz). Analytical data indicated Fe-rich helvine to Mn-rich danalite with Mn/(Fe+Mn) ≈ 0.4–0.6 (Fig. 4c) with low concentrations of Zn (0.07–0.11 apfu) and Mg (≤0.02 apfu) (Table 3, Fig. 4c). For more details, see Zachař et al. (Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020). Primary Be minerals are commonly altered to proximal or distal secondary Be minerals (bohseite–bavenite, milarite, bertrandite and bazzite). For more details, see Novák and Filip (Reference Novák and Filip2010) and Zachař et al. (Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020).

Figure 3. BSE images of primary Be minerals. (A, B) beryl pegmatites and (C, D) helvine–danalite pegmatites. (A) Zoned crystal of beryl (Brl) in albite (Ab), partially replaced by bavenite (Bvn), Kožichovice II; (B) homogeneous beryl replaced by the assemblage K-feldspar (Kfs) + bertrandite (Btd), with associated jarosite (Jrs), Okrašovice; (C) helvine–danalite (Hlv) with phenakite crystals located near the edge, Číměř I; (D) phenakite in quartz (Qz) with late axinite-(Fe) (Ax-(Fe)) and titanite (Ttn), Číměř I.

Figure 4. Compositional diagrams showing (A) octahedral-site and (B) channel-site substitutions in beryl, and (C) compositional variations across the helvine–danalite series.

Table 2. Representative compositions of beryl

* calculation based on ideal stoichiometry;

** calculation based on the premise of H2O (apfu) = 0.413 + 1.36×Na (apfu) (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Groat, Cempírek, Škoda and Holá2023)

Table 3. Representative compositions of helvine–danalite

* calculation based on ideal stoichiometry

Tourmaline and other B minerals in the pegmatites

Tourmaline and other borosilicates (tourmalines ≫ axinite > tinzenite) are typical minor to very rare accessory minerals in some euxenite-type pegmatites from the Třebíč Pluton (Škoda and Čopjaková, Reference Škoda and Čopjaková2005; Škoda et al., Reference Škoda, Novák and Houzar2006; Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011; Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013; Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020; Table 1). Axinite-(Mn) to axinite-(Fe), formed during low-temperature hydrothermal activity, and fills tectonic microfractures in some pegmatite dykes (Fig. 3d). These minerals are associated locally with the Ca–Be silicate bohseite and rarely with tinzenite (Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020). They evidently formed after the crystallisation of the primary Be minerals and are not described in detail.

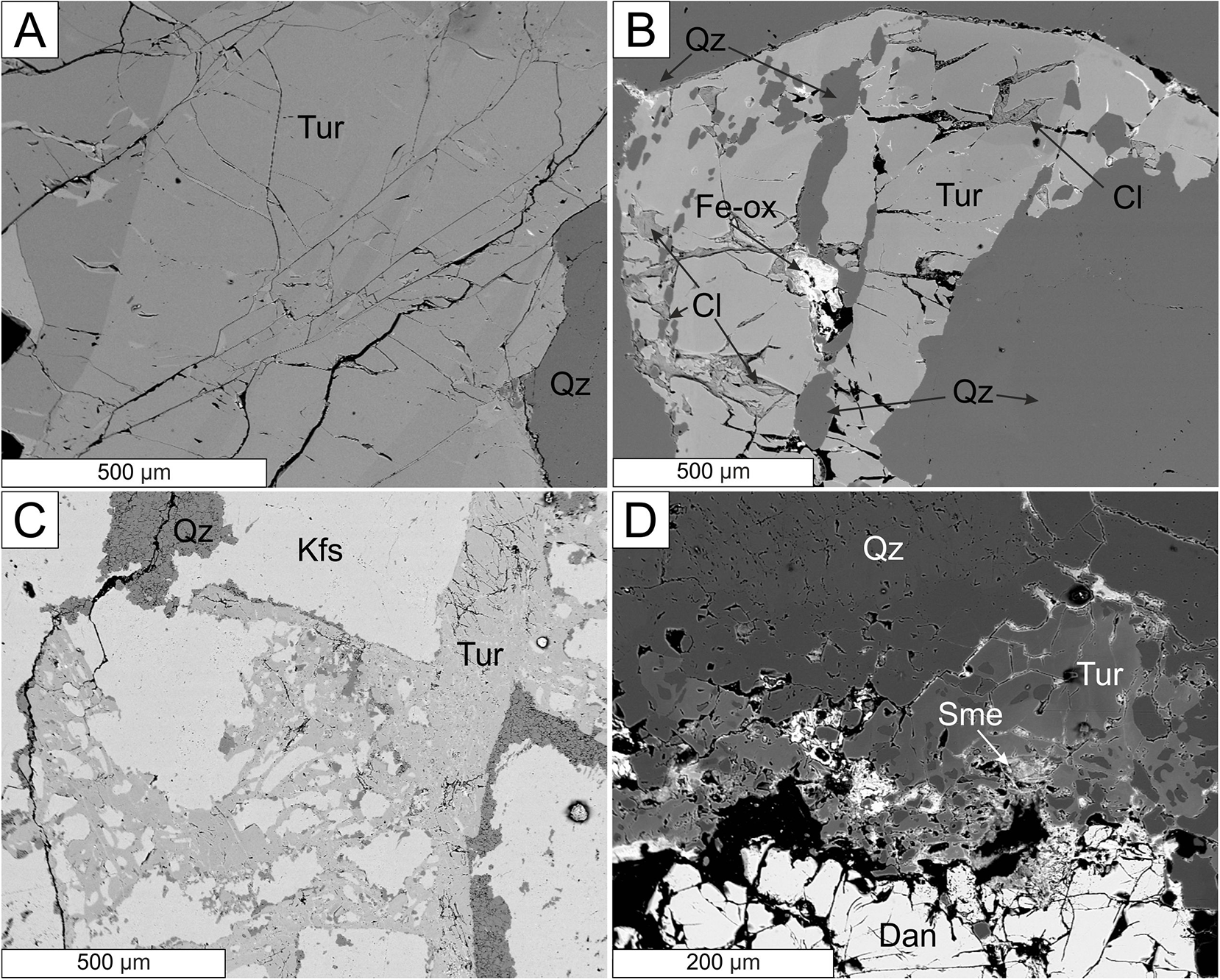

Black tourmaline from pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton occur in distinct morphological, textural and paragenetic types as defined by Novák et al. (Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011; Table 1). Type (a) is the most abundant coarse to medium grained, oval to irregular aggregates and clusters, or rarely short prismatic crystals, commonly ∼1–3 cm in size, which occur in the coarse-grained unit from euxenite-type pegmatites (Fig. 5 a,b). Type (b) are graphic tourmaline–quartz intergrowths, which are less abundant and occur in the graphic unit and in the blocky K-feldspar adjacent to the quartz core together with type (c) rare, fine-grained tourmaline–quartz–feldspar nodules, up to 3 cm in diameter. Rare tabular grains of type d tourmaline, up to 20 × 5 × 1 mm in size, are pseudomorphs after biotite. Abundant interstitial tourmaline (type e) occurs in thin fractures or intergranular spaces chiefly in K-feldspar (Fig. 5c) and in the graphic unit less commonly in albite or in the aplitic unit, though not in massive quartz. Type (f) tourmaline occurs in the HDP assemblage of the Číměř II pegmatite replacing a helvine–danalite grain along the rim (Fig. 5d). Textural relations indicate that tourmaline of types (a)–(c) are of magmatic origin, whereas tourmaline replacing biotite (type d), interstitial tourmaline (type e), and tourmaline replacing helvine–danalite (type f) are of subsolidus and metasomatic origin. Primary helvine–danalite is not in direct contact with any type of primary tourmaline although they are commonly present in the same textural-paragenetic unit.

Composition of tourmalines

Coarse- to medium-grained aggregates and associated euhedral crystals of tourmaline (a) are almost homogeneous (Fig. 5 a,b) to highly heterogeneous, locally with fine oscillatory, patchy, or sector zoning. The crystals have commonly developed a compositionally distinct core, which is slightly more Al-rich than the outer parts of the tourmaline in lessevolved pegmatites which is in contrast to more Al-enriched outer parts of tourmaline from more fractionated pegmatites (Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013). Tourmaline type (b) from graphic intergrowths varies from almost homogeneous to slightly heterogeneous with an Fe-enriched rim. Irregular to fine oscillatory zoning is a typical feature of interstitial tourmaline type (e). In general, all morphological types of tourmaline exhibit highly variable textures in BSE images (Fig. 5) from almost homogeneous to highly heterogeneous, with a combination of oscillatory and patchy irregular zoning without dependence on the degree of fractionation, expressed by Fetot/(Fetot + Mg) ratio.

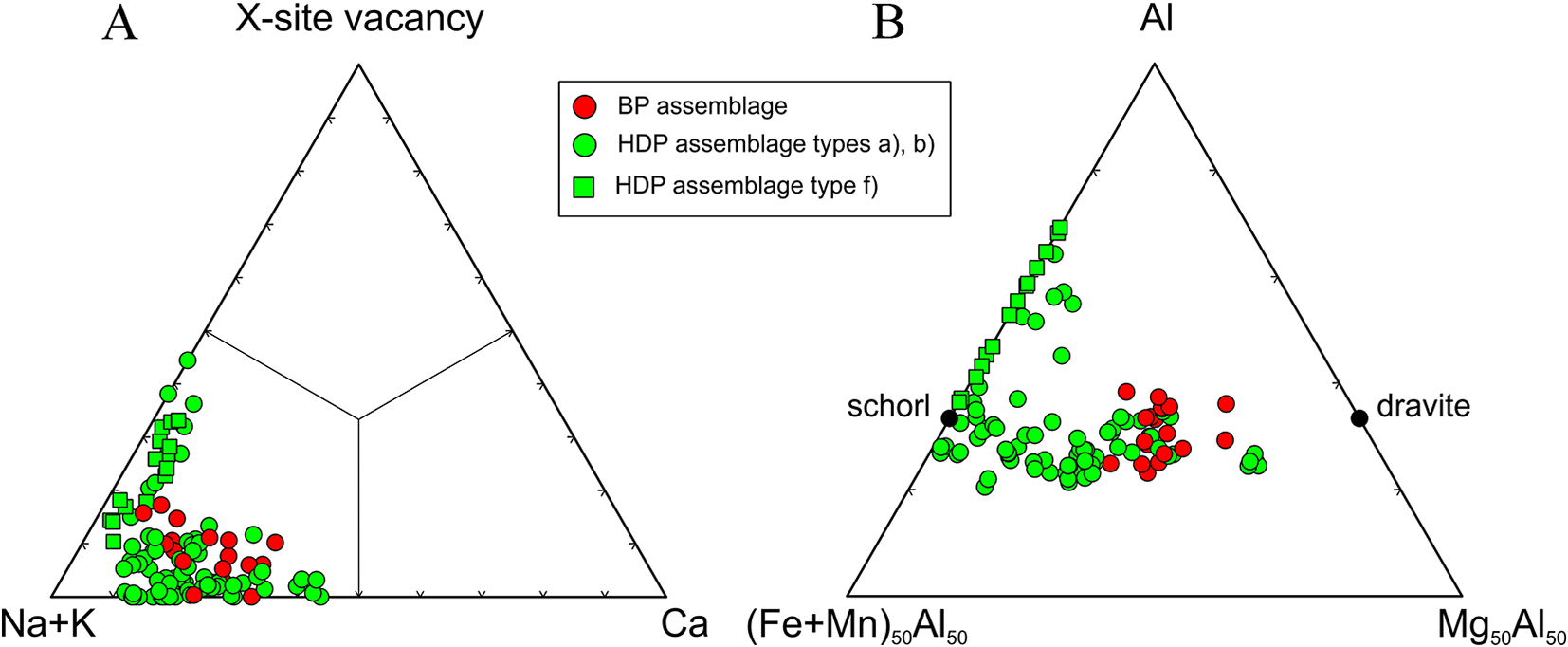

Tourmaline from the pegmatites investigated are generally Ti-rich (≤0.55 apfu) with lowto moderate Al (5.1–6.1 apfu) and variable Mg (0.1–1.8 apfu) and Fe (1.3–3.0 apfu) contents. They correspond to Ca- and Ti-rich Fe-dravite to Mg-poor schorl and to dutrowite to magnesio-dutrowite (Table 4, Fig. 6), Moderate to low Ca (0.4–0.1 apfu), low F (0.1–0.3 apfu) and very low X-site vacancy are characteristic features. They are very similar to tourmalines from the other euxenite-type pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton studied by Novák et al. (Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011), Čopjaková et al. (Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013) and Zachař (Reference Zachař2021). Some tourmaline samples from Číměř I are more evolved with moderate to high Al (5.9–7.6 apfu), low Mg (≤0.3 apfu), high Fe (0.8–3.2 apfu), low Ca (≤0.2 apfu), low to high F (0.1–0.6 apfu), and variable X-site vacancy (0.0–0.4 pfu). The composition evidently resembles more fractionated tourmaline from the evolved euxenite-type pegmatite Klučov I (Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013). The interstitial tourmaline (e), rare in beryl pegmatites and abundant in helvine–danalite pegmatites (Table 1), is Mg-rich as in other pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011). Trace element concentrations in primary tourmaline types (a), (b) and (c) obtained using LA-ICP-MS (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011; Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013) are: Li ≤ 503 ppm; Sn = 50–2019 ppm; Zn = 8–1500 ppm; Y+Ln = 12–180 ppm; and Sc = 32–514 ppm. In addition, elevated Fe3+ contents are systematically present from 0.17 to 0.26 Fe3+/Fetot (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011).

Table 4. Representative compositions of tourmaline

Notes:

† FeOtot;

# from Čopjaková et al., (Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013);

* calculated as 25% from FeOtot, estimated by Mössbauer spectroscopy in similar pegmatites (see Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011);

** calculation based on ideal stoichiometry

Secondary tourmaline (f) replacing helvine–danalite is compositionally distinct showing moderate to high Na (0.64–0.81 apfu) and Fe (0.68–2.17 apfu), high Al (6.57–7.61 apfu), Mn (0.31–0.8 apfu) and F (0.37–0.58 apfu), very low Ca (0.03–0.07 apfu) and negligible Mg and Ti (Table 4, Fig. 6). Abundant early tourmaline from the helvine–danalite pegmatites are evidently more variable in texture and paragenesis and cover the compositional field (see Fig. 6) presented by Novák et al. (Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011).

Discussion

Composition of tourmaline

Compositions of tourmaline from the pegmatite dykes with primary Be minerals fit very well with the compositions of the individual textural-paragenetic types of tourmalines from the Třebíč Pluton pegmatites, as defined by Novák et al. (Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011) and Čopjaková et al. (Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013). In the helvine–danalite pegmatites, abundant primary tourmalines (type a) have higher contents of Fe and commonly also Al compared to the primary tourmaline from other euxenite-type pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton described by Novák et al. (Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011), where low to moderate Al is typical (Fig. 6b); nevertheless, Mg-rich tourmaline was also found in Číměř II. Late fracture-filling tourmaline (e) is typically enriched in Mg, Ti and Ca in both beryl and helvine–danalite pegmatites. These compositions are unusual in granitic pegmatites due to the low Al, high Ca, Fe3+ and chiefly high Ti contents. Dutrowite is quite abundant as well as magnesio-dutrowite. Nevertheless, tourmaline, low in Al, was sufficient to decrease the concentration of Al (lower ASI) in the parental medium and to prevent crystallisation of beryl as an Al-rich mineral.

Newly discovered secondary tourmaline (f) replacing helvine–danalite has high Mn contents (5.2 wt.% MnO, 0.80 apfu) and Mn/(Fe+Mn) ratio (0.51), similar to that of the replaced helvine–danalite (0.49). The low concentrations of Mg, Ti and Ca are different from all other compositional and textural types of tourmaline and their compositions reflect the composition of the replaced mineral. Such Mn-enriched tourmaline is rather exceptional (Fowler talc belt; Ayuso and Brown, Reference Ayuso and Brown1984), as the majority of Mn-enriched tourmaline are Li-bearing and typically occur in LCT granitic pegmatites (Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Falster and Laurs2011; Bosi et al., Reference Bosi, Pezzotta, Altieri, Andreozzi, Ballirano, Tempesta, Cempírek, Škoda, Filip, Čopjaková, Novák, Kampf, Scribner, Groat and Evans2022).

Textural and paragenetic relations of tourmaline and their implications

The abundance of tourmaline, as well as their typical textural-paragenetic types as defined by Novák et al. (Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011), differ significantly between the beryl and the helvine–danalite pegmatites. Rare fracture-filling tourmaline (e) in the beryl pegmatites suggests generally low amounts of B in the parental melt, with a rather elevated activity of B occurring only locally in the residual fluids. The absence of all types of primary tourmaline demonstrates that the parental melt was not rich enough in B to produce primary tourmaline and the concentration of Al persisted as sufficiently high enough in the parental melt to sequester beryl, typically in the more evolved pegmatite units. The high abundance of primary tourmalines, type (a) > (b), in the helvine–danalite pegmatites, particularly in the Číměř I and Číměř II pegmatites is evident.

Fissure-filling tourmaline (type e) documents elevated activity of B in residual fluids as is known from many granitic pegmatites (Martin-Izad et al., Reference Martin-Izad, Paniagua, Moreiras, Acevedo and Marcos-Pascual1995; Novák et al., Reference Novák, Cícha, Čopjaková, Škoda and Galiová2017; Buřival and Novák, Reference Buřival and Novák2018; Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Prokop, Novák, Losos, Gadas, Škoda and Holá2021). Moreover, the high concentration of B in late fluids in several pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton is demonstrated by the replacement of primary phlogopite by tourmaline (type d) (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011). Secondary tourmaline (type f) replacing helvine–danalite indicates that residual fluids were B-enriched and the very low contents of Mg suggest that these fluids were not contaminated by input of external Mg-rich fluids. The abundant, fracture-filling axinite-group minerals also testify to the elevated content of B in these fluids. Moreover, the almost total absence of Mg in these minerals generated from residual fluids suggests that perhaps all Mg was consumed during crystallisation of early primary tourmaline and that at least locally Mg-free fluids occurred in an extremely Mg-rich environments (such as the host durbachite with 3.3–10.2 wt.% MgO, Mg-rich biotite and Mg-rich tourmaline in the Třebíč pegmatites).

Composition of Be minerals

Compositions of primary beryl from the euxenite-type pegmatites in the Třebíč Pluton (Table 2, Fig. 4a,b) exhibit very similar features, i.e. moderate to high concentration of Mg (≤0.44 apfu) and Fe (≤0.24 apfu) (typically Mg > Fe) and minor but characteristic contents of Sc (≤0.06 apfu) and Cs (≤ 0.15 apfu), together with very low Li (≤80 ppm) (see also Novák and Filip, Reference Novák and Filip2010; Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020). Comparing to other granitic pegmatites (e.g. Aurisicchio et al., Reference Aurisicchio, Fioravanti, Grubessi and Zanazzi1988, Reference Aurisicchio, Conte, De Vito and Ottolini2012; Černý et al., Reference Černý, Anderson, Tomascak and Chapman2003; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Che, Zhang, Zhang and Zhang2009; Přikryl et al., Reference Přikryl, Novák, Filip, Gadas and Vašinová-Galiová2014; Bačík et al., Reference Bačík and Fridrichová2021) a significant octahedral substitution chNaVIR2+ = ch□VIAl is indicated by rather low Al = 1.45–1.69 apfu and elevated Na (0.20–0.34 apfu). The composition of primary beryl from Třebíč Pluton pegmatites reaches 42% of the R+Be3AlR2+Si6O18 component (see Novák and Filip, Reference Novák and Filip2010, for details). High contents of Mg in beryl as well as in other primary minerals (tourmaline, phlogopite) from the pegmatites of Třebíč Pluton are different from these minerals in typical NYF pegmatites rich in Fe where high Fe/(Fe+Mg) ratios are characteristic (Aurisicchio et al., Reference Aurisicchio, Fioravanti, Grubessi and Zanazzi1988; Ercit, Reference Ercit2005; London, Reference London2008; Falster et al., Reference Falster, Simmons, Webber and Bodreaux2018).

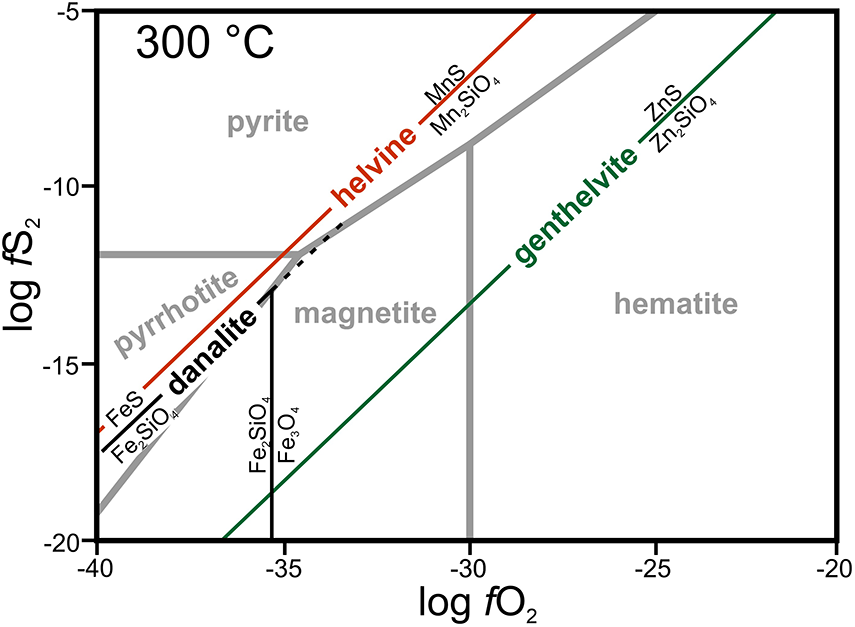

Primary Fe-rich helvine to Mn-rich danalite have low concentrations of Zn (0.07–0.11 apfu) and Mg (≤0.02 apfu) (Fig. 4c). The elevated contents of Mn, but very low Mg in helvine–danalite, are in contrast with the associated tourmaline and reflect opposite compatibility/incompatibility with Mn and Mg for tourmaline and helvine–danalite (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Novák, Hawthorne, Ertl, Dutrow, Uher and Pezzotta2011; Bosi, Reference Bosi2018; Henry and Dutrow, Reference Henry and Dutrow2018). The compositions of the helvine-group minerals shows a low to moderate degree of Mn/(Mn+Fe) fractionation and differs from most granitic pegmatites, where helvine is typically poor in Fe (Barton and Young, Reference Barton, Young and Grew2002; Černý, Reference Černý and Grew2002) and locally Zn-enriched (Hanson and Zito, Reference Hanson and Zito2019). Low concentrations of Zn in primary helvine–danalite might be due to the crystallisation of common early tourmaline, which contains up to 1500 ppm Zn (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011; Čopjaková et al., Reference Čopjaková, Škoda, Vašinová-Galiová and Novák2013). Also, low f O2 is indicated by minor sulfides (pyrite, arsenopyrite) in the pegmatites (Škoda et al., Reference Škoda, Novák and Houzar2006; Zachař et al., Reference Zachař, Novák and Škoda2020) which might have reduced the genthelvite component (Barton and Young, Reference Barton, Young and Grew2002; Lira et al., Reference Lira, Espeche, Bonadeo and Dorais2023).

Figure 5. BSE images of tourmalines (Tur) from Třebíč Pluton pegmatites. (A) Zoned tourmaline of type (a) in quartz (Qz), Číměř I; (B) zoned tourmaline of type (a) in quartz and late-stage chlorite (Cl) and ‘limonite’ (Fe-ox), Číměř I; (C) fracture-filling tourmaline of type (e) replacing K-feldspar (Kfs), Kožichovice II; (D) heterogeneous tourmaline of type (f) replacing danalite–helvine (Dan) and a late stage smectite (Sme), Číměř II.

Boron mineral assemblages in pegmatites from durbachite plutons in the Bohemian Massif

Primary Be minerals occur not only in the intragranitic NYF pegmatites from the Třebíč Pluton examined in detail, but were also found in intragranitic pegmatites from another durbachite pluton of the Moldanubian Zone, the Mehelník Pluton (Pauliš and Postbiegel, Reference Pauliš and Postbiegl1990; Novák et al., Reference Novák, Cícha, Čopjaková, Škoda and Galiová2017). The main difference in the overall mineral assemblages of the primary Be-mineral-bearing pegmatites is the abundance of tourmaline (Table 1). The BP assemblage pegmatites (Table 1) contain very rare tourmaline typically as the late interstitial textural type (e). In contrast, the pegmatites with the HDP assemblage contain rather abundant tourmaline (Table 1) mostly as the prismatic and coarse-grained type (a) as defined by Novák et al. (Reference Novák, Škoda, Filip, Macek and Vaculovič2011) which crystallised earlier than the primary Be minerals. The Velká skála pegmatite in Mehelník Pluton, with milarite–agakhanovite-(Y) as the sole magmatic Be minerals (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Cícha, Čopjaková, Škoda and Galiová2017), contains common primary (a) and interstitial (e) tourmaline, though not as abundant as in the helvine–danalite pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton (Table 1). In contrast, the pegmatites with the HDP assemblage contain rather abundant tourmaline. Crystallisation of tourmaline in Be-enriched pegmatites with a generally metaluminous signature might have lowered the concentration of Al to levels insufficient for beryl crystallisation, which resulted in the formation of Al-free primary Be minerals helvine–danalite ± phenakite and milarite from the Velká skála pegmatite (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Cícha, Čopjaková, Škoda and Galiová2017). The high Al content in most LCT pegmatites worldwide, demonstrated by the abundance of Al-rich minerals (muscovite, andalusite, cordierite, topaz, tourmaline and garnets), explains why locally massive crystallisation of tourmaline did not significantly reduce Al, and why tourmaline (schorl, oxy-schorl) is commonly closely associated with primary beryl. In contrast helvine-group minerals are rare and typically occur in miarolitic pockets (Clark and Fejer, Reference Clark and Fejer1976; Zito and Hanson, Reference Zito and Hanson2017; Raade, Reference Raade2020).

Effect of early tourmaline crystallisation on the composition of associated subsequent minerals

Detailed study of mineral assemblages of primary and secondary Be minerals from intragranitic pegmatites in the durbachite plutons (Třebíč, Mehelník) revealed that they are a useful tool for elucidating P-T-X conditions in the individual pegmatite units (Barton and Young, Reference Barton, Young and Grew2002). The assemblages of primary Be minerals from the examined pegmatites are constrained by variable activities of Al, Si, divalent cations Ca, Mn, Fe2+, Zn, and Mg, trivalent cations Fe3+, REE, Sc, and alkalinity/acidity and especially f O2 (Fig. 7; see also Barton and Young, Reference Barton, Young and Grew2002; Franz and Morteani, Reference Franz, Morteani and Grew2002; Černý, Reference Černý and Grew2002; Zito and Hanson, Reference Zito and Hanson2017). The observed assemblages of primary Be minerals (BP, HDP) evidently show how crystallisation of early tourmaline controls their origin and composition. They are poor in the elements compatible with the tourmaline structure (e.g. Al, Mg and Zn) and enriched in incompatible elements (Mn). Helvine–danalite requires low to moderate f O2 in the stability field of sulfides whereas genthelvite is associated typically with hematite and requires high f O2 (Fig. 7). High to moderate contents of Fe in most primary tourmalines and in helvine–danalite is evidence for its abundance in the system and its high to moderate compatibility with tourmalines and helvine-group minerals.

Figure 6. Ternary diagrams showing the composition of tourmaline from pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton in the X-site and Y+Z-site.

Figure 7. The stability field of helvine, redrawn from Barton and Young (Reference Barton, Young and Grew2002). The highest thermodynamic stability of the helvine, danalite and genthelvite occurs along the respective R2+S/R2+2SiO4 isolines.

A further example, which might be explained by the early tourmaline crystallisation effect, is the composition of columbite–tantalite from Li-rich complex pegmatites. In the complex (lepidolite-, elbaite-, petalite-subtype) pegmatites from the Moldanubian Zone columbite–tantalite typically occurs in albite and albite-lepidolite units and crystallised later than locally abundant black tourmaline (schorl, oxy-schorl) from coarse-grained unit (Novák et al., Reference Novák, Černý and Selway1999, Reference Novák, Povondra and Selway2004). A high Mn/(Mn+Fe) ratio commonly close to 1 is typical whereas the Ta/(Ta+Nb) ratio is mostly low (Novák and Diviš, Reference Novák and Diviš1996; Novák and Černý, Reference Novák and Černý1998, Reference Novák and Černý2001; Novotný and Cempírek, Reference Novotný and Cempírek2021). Changes in the Mn/(Mn+Fe) ratio of columbite from the French Chédeville pegmatites are also explained due to early precipitation of unspecified Fe-rich minerals (Raimbault, Reference Raimbault1998). Crystallisation of a larger volume of black tourmaline might cause the exhaustion of a significant amount of Fe from the magma. Consequently, the high incompatibility of Mn in black tourmaline very probably initiated an increase of the Mn/(Mn+Fe) ratio in the residual fractions of the magma, which is mirrored in the subsequently crystallising columbite-group minerals.

The mineral assemblages from the albite unit in the pegmatite dyke No. 4 and dyke No. 5 from the Hatě area, Dolní Bory, the Bory Granulite Massif, Moldanubian Zone (Hreus et al., Reference Hreus, Kocáb, Novák, Vašinová Galiová and Gadas2025) could serve as another example of the influence of tourmaline crystallisation on the subsequent mineral associations by incorporation of minor to trace elements. Both pegmatite dykes are very similar in their size, shape and internal structure (Duda, Reference Duda1986; Staněk, Reference Staněk1997; Kocáb, Reference Kocáb2016). The dyke No. 4, the type locality of sekaninaite (Staněk and Miškovský, Reference Staněk and Miškovský1975; Černý et al., Reference Černý, Chapman, Schreyer, Ottolini, Bottazzi and McCammon1997) contains abundant sekaninaite mainly in the albite unit and almost no primary tourmaline, whereas dyke No. 5 contains abundant primary tourmaline (foitite, oxy-foitite to oxy-schorl; Mrkusová et al., Reference Mrkusová, Škoda, Haifler, Filip and Holá2023) primarily in the albite unit and very rare sekaninaite in the outer border unit. Sekaninaite from dyke No. 4 is typically closely associated with tabular crystals of ilmenite, up to 5 cm in diameter, which are, almost absent in dyke No. 5 (Staněk, Reference Staněk1997; Hreus et al., Reference Hreus, Kocáb, Novák, Vašinová Galiová and Gadas2025). Crystallisation of the early and abundant tourmaline with 1100–3600 ppm Ti (Mrkusová et al., Reference Mrkusová, Škoda, Haifler, Filip and Holá2023) almost exhausted Ti from the system and prevented the formation of ilmenite, whereas crystallisation of sekaninaite with very low concentrations of Ti ≤ 40 ppm (Hreus et al., Reference Hreus, Kocáb, Novák, Vašinová Galiová and Gadas2025) had only negligible effects.

Summary and conclusions

Primary Be minerals occur in intragranitic NYF pegmatites of the Třebíč Pluton and, less commonly, in those of other durbachite bodies, such as the Mehelník Pluton. The assemblages of primary Be minerals (Table 1) show high variability and are represented by relatively Al-rich BP assemblages in the pegmatites with common beryl and rare phenakite to Al-poor HDP assemblage in the pegmatites with common helvine–danalite, and minor phenakite (Table 1). The Velká skála pegmatite (Mehelník Pluton) with primary milarite is similar to the HDP assemblage.

Relationships between a specific primary Be mineral and the abundance of early tourmaline in these pegmatites are evident (Table 1). In the beryl pegmatites, tourmaline is very rare and developed primarily as the late fracture filling phase type (e), which crystallised after primary Be minerals. In contrast, helvine–danalite is a common accessory phase in the pegmatites with abundant primary tourmaline, typically (a) type, which mostly crystallised in earlier, less evolved textural-paragenetic units and exhausted the magma in Al2O3 thus forming the Al-poor assemblage of Be minerals. The effect of tourmaline crystallisation on the association of Be minerals is accentuated by the metaluminous to slightly peraluminous composition of the pegmatite magma and would be weaker in the strongly peraluminous pegmatites.

The mineral assemblages of primary Be minerals in granitic pegmatites from the Třebíč Pluton illustrate very well that chemical potentials together with P-T conditions govern the stability of the primary Be minerals. Helvine–danalite is poor in Al, Mg, and Zn, elements which are compatible with previously crystallised tourmaline, and enriched in Mn, which is incompatible with the tourmaline structure. The effect of early tourmaline crystallisation might control the composition of some minerals which precipitate later in more evolved pegmatite units. In addition, the abundance of such early primary tourmaline plays a significant role.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gerhard Franz for his comments and careful manuscript handling and reviewers Peter Bačík and Lee Groat for constructive criticism that significantly improved the manuscript. We dedicate this paper to Edward Grew, whose contributions to the understanding of boron and beryllium mineralogy have inspired our research.

Financial statement

This research was supported by OP RDE [grant number CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_026/0008459 (Geobarr) from the ERDF] for RŠ and MN.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.