The great screenwriter

Numerous studies have analyzed Giovanni Sartori’s influence on contemporary political science and his intellectual legacy.Footnote 1 In this article, I aim to address a more specific question concerning this unique personality, 100 years after his birth: the importance of his intellectual project, and his role in the development of an academic community. In particular, I will focus on the influence of Giovanni Sartori on those scholars, in Italy and elsewhere in Europe, who were not yet active when the discipline’s founders established its foundations but could still feel their presence.

Sartori’s case is peculiar in this respect, as most Italian scholars currently active in the scientific community—those trained and recruited since the late 1980s—did not witness him working within the Italian academic system. This was due to Sartori’s decision in the early 1970s to leave Italy for the USA,Footnote 2 a move he implemented during that decade. Consequently, many Italian political scientists belonging to what I term the “middle generation” could not engage directly with the founder of the discipline, even though he remained an active academic until the early 1990s and a vibrant public intellectual until his death on April 4, 2017.

This is not an isolated case of a European political science founder spending a significant portion of their career overseas while maintaining strong connections with their home country. The figure of Juan Linz provides another extraordinary example in this regard. In this article, I aim to emphasize the significance of such examples in the history of the discipline. Specifically, I argue that Sartori’s influence has been (and continues to be) remarkably inspiring. Italian scholars of the middle generation perceived his presence as emblematic of both intellectual leadership and academic excellence across a broad range of topics. Furthermore, through his long-standing contributions to Corriere della Sera, they witnessed an extraordinary example of a public intellectual, learning the importance of political science’s visibility in society.

My argument is that, regardless of varying sensibilities, theoretical orientations, or ideological sympathies, the entire middle generation benefited from Sartori’s extraordinary efforts to establish political science as a respected discipline in Italy. Thanks to his intellectual rigor and visionary project as a “screenwriter,” Sartori laid the groundwork for the discipline, even as he left its “direction” to others. While it would be both disrespectful and inaccurate to attribute the emergence of political science in Italy solely to Sartori, celebrating his centenary is an opportunity to rediscover the unity of a community that has now reached its fiftieth anniversary (Verzichelli 2024), accompanying the second half of Sartori’s century.

After a brief assessment of the foundation of the Italian political science community, I will demonstrate how the project inspired by the “great screenwriter” significantly shaped the discipline’s development in Italy over time. To summarize, Sartori provided a perfect blend of scientific inspiration, dedication to the discipline, and attention to real-world politics over an extended period. If we wish to preserve this legacy, we now have the responsibility to document and reflect on the personal memories and the meaning of the cultural project we have inherited. I believe this legacy should be safeguarded for future generations: those who, due to their age, could only read Giovanni Sartori’s works, discovering countless insights and reasons to engage with his writings, but who never had the chance to witness his personal journey or his contributions to the scientific community. I will therefore conclude with a brief reflection from this perspective.

The formation of the scientific community

Sartori himself (Reference Sartori1997; 2016) described in detail how he staged the screenplay of this project, through episodes in which he was the undisputed protagonist: first, the framing of the discipline within the ministerial programs of political sciences (1969) just after the difficult period, when Sartori was the Dean of the faculty of political sciences at the University of Florence. This passage was crucial in terms of institutionalization, since this set the stage for the first national competition for a few “professorships” in political science (1971).

The second fundamental event was the creation of the Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica (RISP), born in 1971 after an obstinate action that Sartori and a few young collaborators had taken with the most important publisher in the field of social science: il Mulino in Bologna.

The third event was the founding of a professional association—the political science section of the Associazione Italiana di Scienze Politiche e Sociali (1973), which was later transformed into the Società Italiana di Scienza Politica.

Sartori’s life thus marks the journey of a discipline that is still evolving today and, to some extent, under debate, since its future is tied to a delicate balance between different sensibilities and visions (Capano and Verzichelli Reference Capano and Verzichelli2023), making its trajectory increasingly fascinating but also revealing its inherent fragility. In Italy, the difficulties were particularly evident both in the academic projection of the discipline and, even more so, in its social penetration. Sartori had to face these obstacles. Nevertheless, his screenplay was brought to life, and Sartori succeeded in setting political science on an unstoppable path, built on three key elements: a modern and inclusive idea of political science; the ability to gather the necessary resources to give substance to this idea; and the ability to engage the right people to carry it forward.

This effort has already been documented (Passigli 2005; Sartori 2016; Morlino 2017; Cotta Reference Cotta2017; Pasquino Reference Pasquino2019). Here, I just want to reiterate that, in the view of all the scholars recruited through the years, Sartori is the one who understood how to sequence these elements correctly. The darkness of the Fascist regime that he lived under during the first part of his life explains the delay in the emancipation of an inherently democratic discipline. However, he could understand the persisting constraints and the rigidity of the Italian cultural system when, after the rebirth of a democratic rule, he rapidly imposed his personality as a young academic in the field of philosophy.

Perhaps, he had already begun to contemplate a project for political science in Italy since his period of self-exile in Florence to avoid conscription into the army of the filo-Nazi Italian Social Republic. At the time, Sartori had already delved into mostly philosophical works. However, thanks to his international connections, the young philosopher was shaping himself as a sophisticated analyst of democratic theory, capable of soon entering the orbit of important American political scientists. Between 1949 and the early 1950s, he frequently traveled to the USA, where he earned the respect of several scholars. At the same time, he deepened his study of the philosophy of language, especially drawing on A.J. Ayer and the English school. And he established friendships and collaborations with various empirical European scholars, who, along with him, would become the refounders of political science (Daalder Reference Daalder1997).

The tangible proof of Sartori’s early ability to build intellectual bridges and personal relationships within the political science field is the fact that, at just 30 years old, he was able to organize an international symposium in Florence sponsored by an association (the International Political Science Association) that could not yet have Italian members due to the complete academic absence of the discipline in the country! His own contribution to that symposium was substantively structured around the objects and mission of the discipline, (Sartori Reference Sartori1954), which clearly demonstrates that his screenplay was already written, at least in the mind of the master. In any case, the culmination of this phase would be the crystallization of a vision of political science that he would always reaffirm: an empiricist vision with a strong theoretical foundation:

“My conception of political science undoubtedly bears an American imprint. In a country where the term ‘purely empirical’ was pejorative, I argued that political science differed from political philosophy precisely because it was an empirical science” (Sartori Reference Sartori2011, 21).

Later, when introducing the reader that would be offered to the Italian public to disseminate a selection of classics (Sartori 1970a), he would clarify the exact meaning of his desire to capture American political science without, however, feeling subordinate to it:

We all recognize the undeniable merit of American political science, which, in the last 20 years, has made a qualitative leap. But learning does not mean copying. Disciplines such as political science are obviously not ‘national’ (Sartori 1970a, 26).

In short, the screenplay we have to preserve is the story of a project that brings together the old and the new, tradition and innovation, creative passion and technical application, humanities and social sciences, individualism, and collective effort. It is also a mix of Europe and the USA. A picture taken in Bellagio in 1963, showing a composed Sartori between his admired supporters Norberto Bobbio and Robert Dahl, is the perfect synthesis of such a project.Footnote 3

During the long preparation of the foundation of political science in Italy, Sartori produced some of the works that later became classics: the English version of his first volume on democratic theory (Reference Sartori1963), some fundamental essays on political science epistemology (Reference Sartori1970b; Sartori et al. 1975) and the conspicuous material later (partially) collapsed in the famous volume on parties and party system (Reference Sartori1976). However, all these works ran parallel to an ongoing discussion about the mission of political science and its relationship with philosophy or political sociology. This impressive sequence of works—ranging from theoretical to epistemological and empirical studies—would later make him, as he jokingly said, a “specialist in everything.” However, to stress the scope of the Sartorian activism, one should also mention a project that began in 1956 and culminated in a volume published (in Italian) on the Italian Parliament (Sartori Reference Sartori1963). This research is obviously relevant above all for those who would have later cultivated research interests in comparative political institutions. But, there is another element in this project—connected to the screenplay of a new disciplinary project—that deserves attention. In fact, this is the first program of empirical, group-based, and multidisciplinary analysis of the Italian political system, which precedes the sociological initiatives of the Cattaneo Institute in the late 1960s on party organizations and political culture. Incidentally, by leading this research group, Sartori also laid the groundwork for his future academic leadership: his presidency of Cesare Alfieri came shortly after (in 1969) and marked the central moment of his push toward the academic consolidation of the discipline.

Thus, Sartori’s cultural legacy stems from a balance between his incredible intellectual talent and three innovative capabilities: designing research, creating some form of social impact through knowledge, and ensuring the future of research through effective mentoring and scouting practices. The talent was innate, but the rest had to be built. This is why the “screenplay” of his project would take its final shape only after the maturation of his multifaceted academic role: indeed, Sartori had served as a professor of philosophy until 1961, when he obtained a chair in sociology in Florence.Footnote 4 He then became the first full professor of political science (1966), after having also assumed a social visibility as a public intellectual and columnist.

This legacy is unique in the Italian cultural scenario and should be discussed well beyond the confines of the political science community, as it proposes a model of modernization and intellectual growth for the scientific profession and, ultimately, for the country. However, I will stick to the “internal” impact on the discipline. The body of research areas codified with the above mentioned Antologia di Scienza politica (1970a) and the mix of Italian translations and original essays published in the early issues of the Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica (RISP) demonstrate Sartori’s care for pluralism of interests and his focus on relevance, without ever losing sight of epistemological coherence. These three aspects of the Sartorian approach were analyzed by Morlino in his thorough work on the evolution of Italian political science (Reference Morlino1991).

The only way to make political science plural, relevant, and united was to integrate and connect different schools, ensuring that no part was left out. This is why Sartori was never the sole “director” in the discipline’s development, even though he remained its first and inimitable screenwriter. From its early years, the RISP substantially expanded its scientific committee both geographically and substantively, constantly producing essays and research from various institutions and perspectives. This allowed Sartori to involve the entire emerging community of Italian political scientists. The study of the international system had already been integrated, with Umberto Gori, into a group that undeniably formed under the label of comparative politics. The involvement of scholars like Mario Stoppino (Pavia) and Paolo Farneti (Torino) was important not only for the institutions they represented but also for their vision of the discipline. RISP would soon start engaging with authors far removed from the initial 'scrum pack'Footnote 5 and very different in both research interests and theoretical paradigms. The same can be said for recruitment and academic policy. Sartori admits to having worn himself out during the critical years of putting his project into motion.

Between 1971 and 1972, exhausted from three years of battles within the university (quite harsh ones in the Italian context), I went to Stanford, where I spent a delightful and fruitful year 'on the hill' as a fellow at the Centre for Advanced Studies in the Behavioural Sciences (Sartori 2016, 14).

I have always been amused by the image of Sartori trying to reason with the’68 student activists. At the same time, these words also confirm the great modernity of this figure and his aversion to preserving academic power, perhaps the most characteristic component of the traditional “baronage”. The script is now written and tested. The direction can change hands. And indeed, Sartori emigrates. However, he will not be absent from the future evangelizing work produced by some scholars close to him. His first group of collaborators—Alberto Spreafico, who had a fundamental role in the academic institutionalization of the discipline, with Stefano Passigli, Domenico Fisichella, Gianfranco Pasquino, and Giuliano Urbani. So different in terms of political and scientific sensibilities, all these scholars remained aligned with Sartori. Close to him are also the scholars of the post-war generation: the group of young “Florentines” led by Leonardo Morlino who were involved in the Centre for Comparative Politics created in Via Laura,Footnote 6 integrated by a few scholars from Bologna. But, the project also attracted Giorgio Sola, who came from the Genoese school of political history.

Many documents and memories from those years tell of the collaboration between Sartori’s group and other institutions and leaders of the discipline—Luigi Bonanate in Turin, Antonio Papisca in Padua, and then colleagues from Milan’s State University and the Catholic University. In Bologna, Sartori joined the committee that appointed Giorgio Freddi—who, along with Beppe Di Palma and Giacomo Sani, had earned a doctorate in the United States—as professor of Public Administration. In this way, a new segment of the discipline was sanctioned, inaugurating the fruitful Bolognese school of public policy and organizational studies.

It would be interesting to partake in the lively discussions that Sartori might have engaged in with all these personalities, as well as the various points of confrontation and potential conflict. Yet, his script foresaw an evangelization that went beyond individual sensitivities and preferences. Already in 1967, as the only full Professor of political science at a conference organized in Milan on Social Sciences, University Reform, and Italian Society, Sartori (1967) codified his comprehensive vision of the discipline, plainly calling for a pluralistic presence of various fields within political science as a key to the overall growth of all social sciences in the Italian educational system. Reading this educational program alongside his reflections on the discipline’s lag in Italy and the added value of empirical research—incubated since that early essay by Bruno Leoni in Il Politico (Reference Leoni1960), somehow inspired by Sartori (Morlino Reference Morlino1991; Sola 2005)—and on the other hand, the sophisticated essays that Sartori published in the first issues of RISP—the famous piece on comparative politics, and the pair What is Politics and Politics as Science, published in sequence to address the object and subject of the new discipline—we see the project elaborated in its entirety.

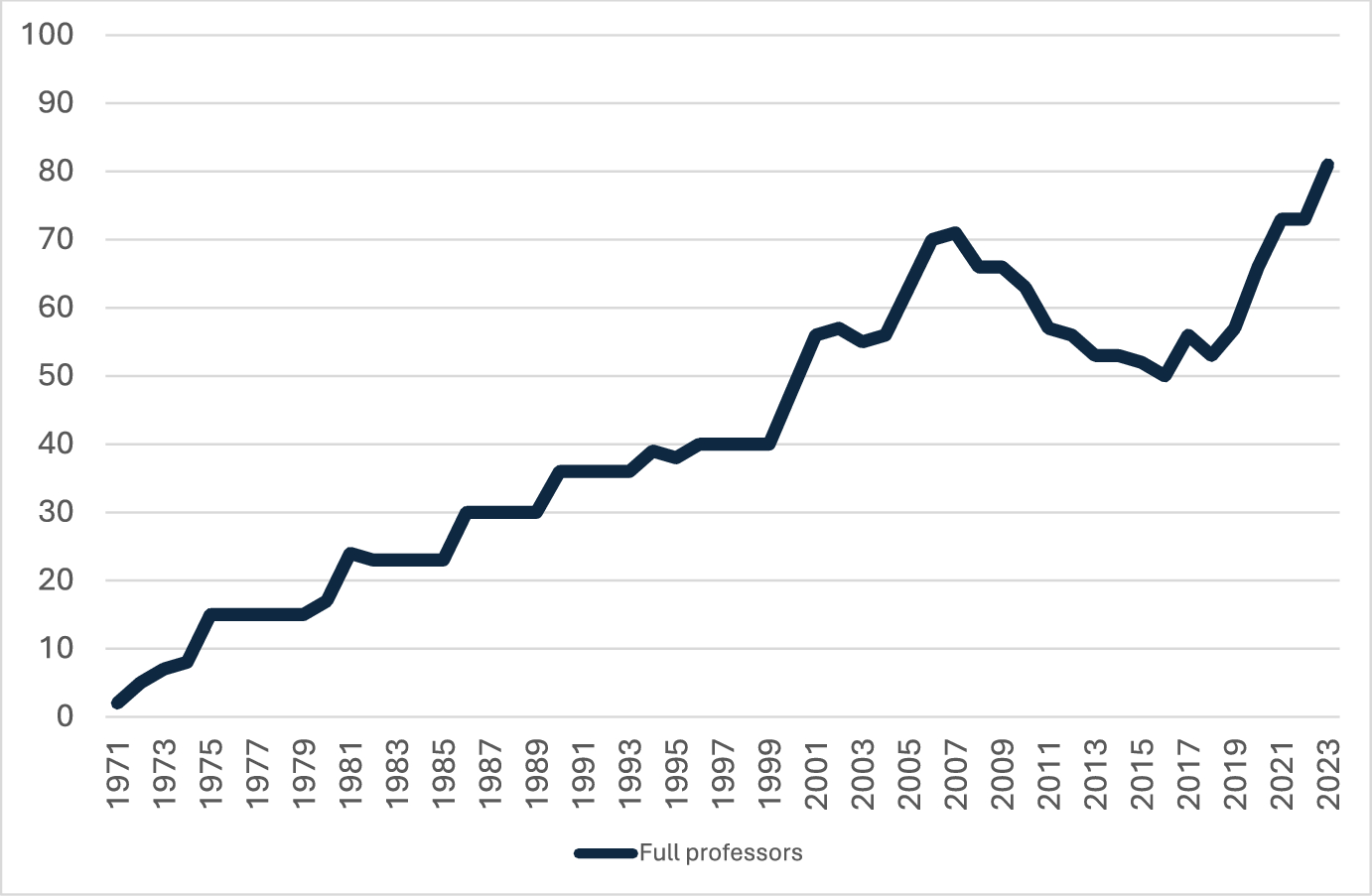

The reform of the university system, approved a couple of years after the aforementioned conference, allowed political science to debut in the program planning of many faculties of political sciences. The first significant result of this evangelization can be seen in the curve of full professorships (Fig. 1), which began to rise in 1970s reaching a first important acceleration during the following decade (Morlino Reference Morlino1989).

Fig. 1 Full professorships in political science in Italy, 1970–2024.

The figure clearly shows that the “Sartorians” who became full professors during the academic consolidation of the discipline, roughly up to 1990, numbered no more than thirty. However, in the two subsequent decades, at least twice as many scholars managed to attain professorships. This is the first indication of the strength of the academic legacy of the great theorist. However, the institutionalization of political science in academia—in Italy as well as elsewhere in Europe—has not depended solely on numerical growth but also on the shared capacity building within the universities. This capacity evidently permeated the first generation of scholars, who were able to train and subsequently bring into the system the middle generation. This latter cohort benefited from a second substantial increase in positions, interrupted only by the depressive effect of financial crises and budget cuts at the beginning of the 21st century, an effect which proved to be dramatic on the entire Italian academic system.

This does not mean that the fight for the institutionalization was won. Other critical issues persisted, such as the fact that political science was almost entirely male-dominated—again, a general problem, in Italy—and the clear geographic imbalance between the Central-Northern area and the South (Bolgherini and Verzichelli Reference Bolgherini and Verzichelli2023; Carrieri and Raniolo Reference Carrieri and Raniolo2024). However, the pace of growth remained evident and the role of Sartori, even during 1980s, remained crucial: he was active in the evangelization, formally directing RISP and participating in the activities of the first Italian doctoral program in political science. Indeed, his influence facilitated the emergence of a national consortium led by Florence, that would, for years, bring together the most significant institutions in political science.

As mentioned, another peculiar aspect of the persisting role of Sartori for the formation of the middle generation of scholars was his continual presence in public debates and controversies on politics or political science. This certainly led him to some positions that were debated and somehow criticized even within the community of scholars. Yet, these positions reflect an unrelenting interest in the fate of political science and its consolidation as a social force. Gianfranco Pasquino has written extensively on this (Reference Pasquino2005b, Reference Pasquino2019). His attachment was that of a protagonist and militant intellectual, as is often noted in writings about him. But what the younger scholars learned from Sartori (far more than from other public intellectuals) is that his hubris, however apparent, never overshadowed his metis and never sidestepped the collective cause that inspired the script for his political science project. The symbolic date marking the definitive codification of this project is 2004, when RISP ownership transferred to the Italian Political Science Association (SISP), and the directorship—Sartori had never vacated this role, instead appointing four co-directors—was handed to an Editor-in-Chief selected from within the discipline.

The development of the discipline as a cultural project

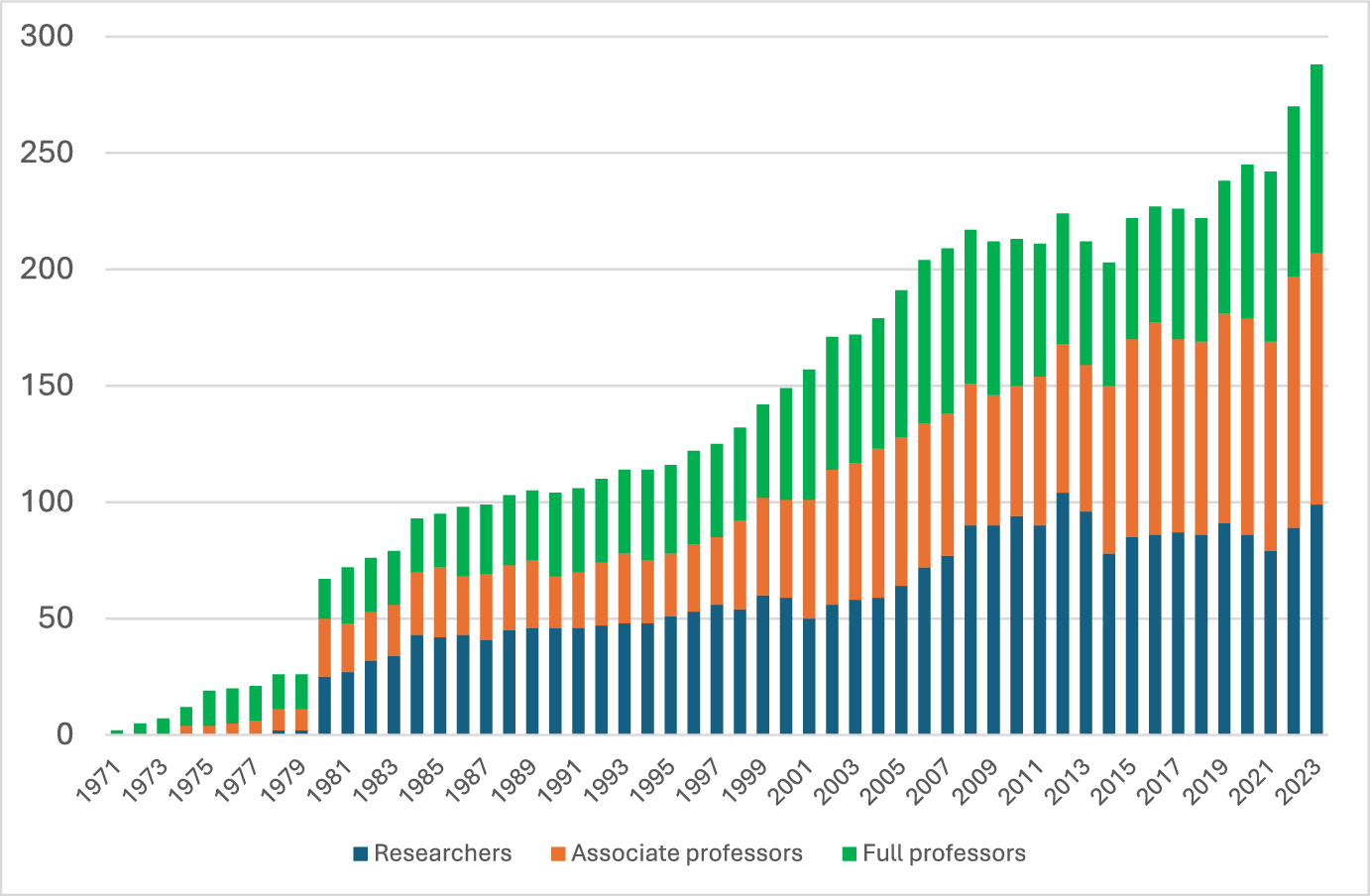

Let us return to our data, where we left off in 1980s, when the first “scrum pack” of full professors was joined by former fellows from the school of via Laura and other scholars, bringing the number of tenured positions above 50 right after 1980 (Fig. 1). Sartori was rightly pleased that most of these full professors were recruited from his school. But what’s even more important to observe today is these scholars' ability to stage the script in other venues and over time. Sartori, now in the USA, still saw Florence remain the political science capital of Italy. However, a good number of political science positions were advertised in many other universities, using the new “tenure” model for university researchers. This allowed the number of positions in the discipline to surpass one hundred before 1990 (Fig. 2), a figure that would double in about 10 years, thus opening the Italian academia to new generations of political scientists. The last cohort of the Sartorians was composed by scholars born in the early fifties, who had been still somehow directly connected to the original design of the maestro. Among them, Maurizio Ferrera (future RISP co-editor), Luciano Bardi (future ECPR chair), and Stefano Bartolini (then Professor and Director of the Schumann Centre at the European University Institute in Florence). During the 90s, the middle generation of political scientists reached the academia, bringing a significant series of innovative approaches and themes—as the same that Sartori had wished for—harmonizing their voices with the previous ones. It is hard to propose an illustration of this powerful but coordinated increase of competences without omitting some relevant names. I will just name in this cluster of scholars a future chair of the Italian Political Science Association (Pietro Grilli di Cortona), a well-known scholar in the field of social movements (Donatella della Porta) and a few scholars recruited in the Italian academic system after significant experiences abroad (for instance, the future first female chair of ECPR, Simona Piattoni and Fabio Franchino).

Fig. 2 Total number of positions in the field of political science (1971–2024).

Thus, despite its growth, the Italian political science community remained sufficiently cohesive. Collaboration around RISP was echoed in doctoral programs, particularly in the consortium led by Florence, which became the primary training ground for all the scholars. Then, it came a first textbook in Italian, published by Mulino in 1986 (Pasquino Reference Pasquino1986), strongly inspired by Sartori’s experience, which has been adopted for years in all the entry-level courses of political science in Italy.

After the above-mentioned turning point of 1990s, both the size and the geographic reach of the discipline expanded, as did its impact on educational pathways. It is not necessary to delve into detailed analyses of this dynamic, as they have been addressed even recently.Footnote 7 Here I just want to highlight two key points.

The first piece of evidence is related to geographic growth. Political science academics are now spread out throughout Italy, with significant footholds even in southern regions like Campania and Calabria, once entirely isolated. New areas of the discipline have strengthened, and the represented institutions have multiplied: at the end of 2024, 56 universities have at least one tenured political scientist!

The second finding concerns the completion of a research experience, which is also linked to a teaching specialization highlighted by SISP data. A recent study on the profiles of Italian research: the Sartorian “core” is still strongly represented five decades after its founding (Verzichelli and Zucchini 2024). Yet, there is a clear need to progressively shift the agenda in other directions. In the 1990s, contributions in public policy and European studies strengthened, while after the millennium turn the importance of various segments within the complex field of international relations increased.

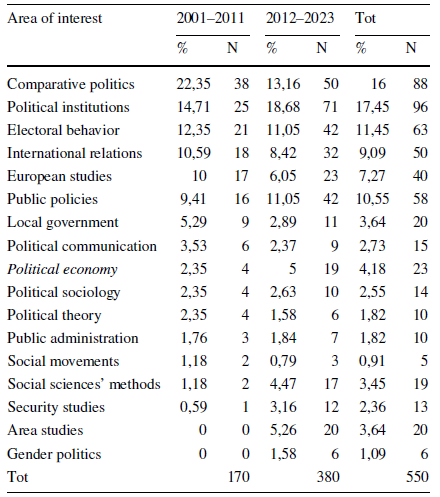

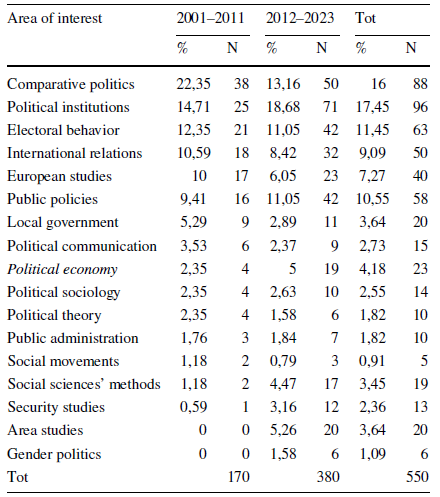

The shift in the focus of Italian political science research appears incremental and driven by the complexity of contemporary politics. A further analysis of publications by Italian scholars in RISP/IPSR—as a proxy for the representational capacity of the research—reveals growth in methodological skills, the number of inferential techniques used, an increase in the average number of co-authors, and a slight rebalancing in the gender distribution of authors (Verzichelli and Zucchini 2024). Looking at the disciplinary profiles of the empirical studies published (Table 1), we observe a persistent “empirical relevance” that unfolds with increasing thematic variety. Certainly, the dual dilemma of relevance/irrelevance and fragmentation/unity remains—and in some ways, is reinforced. It is a dilemma that accompanies us because it must.

Table 1 Relevance of areas of interest in “empirical” articles published in IPSR/RISP by authors affiliated with Italian institutions (2001–2011 and 2012–2023)

Source: adapted from Verzichelli and Zucchini (2024)

A closer look at the table reveals that the composition of Italian research—here assumed to be represented by the production of articles in the discipline's leading national journal—does not deviate significantly from the original Sartorian vision. Nevertheless, the body of literature, once focused primarily on institutionally oriented comparative politics, has expanded to include areas of research that were previously absent (such as gender studies). Similarly, the field of international studies has not stagnated within the traditional (still relevant) sector of International relations, but has instead expanded, with the emergence of new areas like area studies, international political economy, and security studies.

The effective number of areas of interest, calculated using the well-known Laasko and Taagepera index for parties and based on the categories used by Capano and Verzichelli (Reference Capano and Verzichelli2023), shows a significant increase (from 8.11 to 10.14) across the two decades considered.

Consolidating knowledge. Embracing doubt

Thus, the original structure of the Italian political science community endures, but it grows and is enriched by the introduction of new themes and ideas, making Sartori a mentor to projects often distant from his original scope. This, too, was written into the Sartorian screenplay.

The exchange of ideas within research agendas and the convergence in teaching have allowed the discipline to move as united, even as the community has grown significantly. The scholars from the middle generation encountered an already established project in many institutions. They admired the interventionist skills of those inspired by Sartori, who also taught the value of direct engagement—it is worth noting the high profile achieved by the few of Sartori’s followers who have pursued prestigious political careersFootnote 8—and the ability of all the components of his team to maintain focus on the rigor and mission of the discipline. Those who remained committed to the academic institutions, then achieved an impressive impact in terms of research outcomes and also in terms of organizational responsibilities.Footnote 9

This is not the right place to systematize the historical impact of the generations of scholars who followed Sartori’s traces. This task has been carried out by the SISP which has already produced publications (Pasquino et al. Reference Pasquino, Regalia and Valbruzzi2013; Verzichelli 2024), a digital historical archive and video-interviews.Footnote 10 It worth remembering, however, that protecting the memory of the discipline means staying consistently “on the ball,” reading widely, and remaining curious even about research that seems “distant.” Curiosity and passion for accumulating knowledge are, in the end, the true hallmarks of Sartori’s project and those who worked alongside him.

This institutional building capability of Sartori is somehow connected to his attitude to change theoretical targets in his research. In the end, he seems to suggest to all of us—children and grandchildren—that anyone curious will inevitably find themselves doubtful at times. This may seem strange for an assertive polemicist like Sartori, but fundamentally, his refusal to serve any single approach means acknowledging that, under certain conditions, all approaches are, in principle, worth exploring. Sartori’s judgment of the recent American political science—which initially inspired and later welcomed him—is a provocative and debatable argument, but even an extraordinary manifesto of open-mindedness and doubt:

I must conclude. Where is political science going? In the argument I have offered here, American-type political science (to be sure, the “normal science” for intelligent scholars are always saved by their intelligence) is going nowhere. It is an ever growing giant with feet of clay. (Sartori Reference Sartori2004, 786)

Hence, one of the defining characteristics of Sartori’s approach to his team was the courage to change agendas. One should notice that, since the early days of the Centre for Comparative Politics in Via Laura, each scholar would select at least a couple of broad research areas in which to try to build robust explanations, changing the subject and, if necessary, the method if a research agenda proved fruitless.

It is not for me to say whether this autonomy has resulted in good research. I can say that our data show that the necessary pluralism has remained with us, and that we have not feared changing research agendas. The profiles of members of the political science community have grown, always keeping an eye on international discourse. We have continued to invest in quantitative research, which Sartori often kept at arm’s length (when quantitative methods were unnecessary) but still encouraged us to understand, if only to critique it:

…we have welcomed both the theorizing political scientist and the mathematizing one with equal favor, though always curbing excesses and ensuring an identity for the discipline we profess. (Sartori Reference Sartori1980, 4).

In any case, what we can define as the “Via Laura atmosphere” is something that survived in the actual time and place of Sartori’s experience, permeating several places. This is, at least, what I felt—as one of the scholars of the middle generation—when I have somehow imagined to have personally attended those Florentine seminars that were counted on by Sartori’s followers and somehow replicated in several academic venues.Footnote 11

Why we cannot yet be satisfied

This article has revisited stories that have already been told, at least within the Italian context. Nevertheless, I hope that it underscores the importance of remembering the development of a discipline and the individuals who made such progress possible. Giovanni Sartori’s journey is emblematic in this regard. His story reflects the enduring influence of a personality whose legacy persists even as the personal memories of those who worked alongside him during the discipline’s foundational phase have been replaced by the collective awareness of those who, though they never knew him, still regard themselves as his “successors.”

This sense of continuity does not hinder substantial renewal in the research agenda or a broader methodological and thematic pluralism within the community. On the contrary, the shared sense of a strong disciplinary identity—thanks to the cultural project of its “screenwriter”—fosters a virtuous dialog and provides guidance for future generations of political scientists. My conclusions echo Marco Giuliani’s recent statement (2025) on Sartori’s epistemological contribution: we cannot help but consider ourselves Sartorian.

Yet, while others may (and must) lead new projects for political science, Sartori remains a model for multiple generations precisely because of the depth of his insights into the complexity of political science and the multifaceted role of political scientists. However, I must add that we cannot be satisfied with merely being Sartorian. Certainly, the Italian political science community is (relatively) large and continues to be influenced by Sartori’s project, even as our research agendas evolve to reflect changes in politics. The Italian community is also significant within the European and global discipline, contributing through research achievements, leadership roles in associations, publishing, and scientific dissemination.

So why can we not yet be satisfied despite these accomplishments? I see three reasons, which I will outline briefly by revisiting the three components of the “screenplay” written by Sartori: scouting, academic impact, and research relevance.

Regarding the ability to recognize and recruit talent, I see the risk of diminishing attention. The Sartorians who shaped the middle generation (not only in Italy) established recruitment rules and practices, created a competitive yet collegial environment, and exhibited a zeal for engaging with every line of research, even those far removed from their own interests. Today, this level of attention seems to be waning, partly due to the various distractions of modern academic life: hyper-specialization, the relentless pace of submissions, and the predatory nature of the publishing market.

However, I also detect a certain negligence that leads to the approval of immature work and a decline in rigor as referees. There are neo-endogamous risks, where scholars focus solely on niche research areas—important as they may be—and engage only with those working on precisely the same topics. There is too little effort to establish robust linkages between concepts, terms, and references. Using Sartori’s own words, I advocate for a path we risk forgetting: a middle way that avoids both ultra-specialization and dilettantism while rejecting what is excessively minute or overly generic.

On institution-building, I have addressed the challenges elsewhere (Capano and Verzichelli Reference Capano and Verzichelli2023). To summarize briefly, Sartori taught us that the hubris of the fighter is important and sometimes necessary. However, his vision for political science also embraced metis—the humility of those who understand that realizing a project transcends individualism and personal ambition. This requires “getting one’s hands dirty” in academic politics. Only by standing among others can we fully understand what political science—and science more broadly—serves in society.

Sartori’s most significant legacy in this regard is the strong awareness he instilled in future leaders of the discipline about the importance of its boundaries and methods. This awareness was also reflected in his foundational educational goals. He advocated for a multi-faculty institute—falling short of an ideal Anglo-Saxon “political science department”—as the minimum realistic objective for a discipline aspiring to a meaningful place within a university concerned with the social sciences.

Today, this attention remains insufficient. We risk becoming incapable of defending our collective role, neglecting our place in institutions, our methods, and our role in curricula. At times, we even forget our own “name.” To this day, it is not uncommon to encounter interlocutors who perceive “political science” as a singular, vague concept—a sort of oxymoron held by general intellectuals without a specific scientific home. We are lucky if we’re not labeled as professors of “political sciences,” as was the case with Sartori a decade after the founding of RISP:

If a newspaper or magazine cited me, I would inevitably become “professor of political sciences”…no matter how annoyed I was or how much I explained, there was always some zealous editor or proofreader who would rephrase it—maybe at the last minute—in the plural (Sartori Reference Sartori1980, 3).

Perhaps, we too should once again bristle at these details. It might serve Sartori better, as well as the new talent we seek to recruit to improve our universities and society. To avoid all these risks, we must continue to remain relevant and sometimes have the courage to change our agendas and our tone. Sartori discussed these contradictions of ours, sometimes with a deeply pessimistic tone. Personally, I am less pessimistic, since I think we are still reasonably protected by the robustness of his project and the example of many other excellent mentors. But, I am also unwilling to settle for what we have achieved. Therefore, I believe that we should keep in mind Sartori’s warnings and even his notes of pessimism, for a long time to come.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Siena within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.