Introduction

Cereal production is crucial for human and animal nutrition, driving global food security and sustainability. In Spain, 5.52 million ha of grain cereals were grown in 2024, accounting for 68% of the total area of herbaceous crops. Maize (Zea mays L.) is primarily used for animal feed and was cultivated on 267,176 ha for grain production and 96,219 ha for forage (MAPA 2024), with acetolactate synthase (ALS) inhibitors commonly used for weed control in this crop.

ALS inhibitors control weeds by blocking the ALS enzyme, which is essential for the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids valine, leucine, and isoleucine (Duggleby et al. Reference Duggleby, McCourt and Guddat2008). Since their introduction in the 1980s, ALS inhibitors have been widely used in cereal crops due to their high selectivity and efficacy at low application rates (Tranel and Wright Reference Tranel and Wright2002). However, their extensive use has contributed to the evolution of resistance (Montull and Torra Reference Montull and Torra2023). The first report of ALS-inhibitor resistance was made in rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaudin) in 1982, and 746 cases across 172 weed species have been recorded globally since then (Heap Reference Heap2025).

Target-site resistance (TSR) to ALS inhibitors results from point mutations in the ALS gene that alter the enzyme’s structure and reduce herbicide efficacy (Lonhienne et al. Reference Lonhienne, Garcia, Pierens, Mobli, Nouwens and Guddat2018). Mutations at nine key amino acid positions have been identified, with Pro-197 and Trp-574 being the most prevalent, found in 52% and 23.4% of resistant weed species, respectively (Tranel et al. Reference Tranel, Wright and Heap2025). On the other hand, non–target site resistance (NTSR) mechanisms reduce the amount of herbicide reaching the target site by modification of physiological processes, such as reduced absorption, altered translocation, vacuolar sequestration, rapid necrosis, and enhanced metabolism (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Duke, Morran, Rigon, Tranel, Küpper and Dayan2020; Mucheri et al. Reference Mucheri, Rugare and Bajwa2024).

Enhanced metabolism, mediated by the enhanced expression of herbicide-degrading enzymes like cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s) and glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), is considered the primary NTSR mechanism conferring resistance to ALS inhibitors, especially in grass weeds (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Duke, Morran, Rigon, Tranel, Küpper and Dayan2020). Management of metabolism-based NTSR populations is particularly challenging, as they may display unpredictable cross-resistance to multiple herbicide modes of action, including to herbicides with no prior application history (Bobadilla and Tranel Reference Bobadilla and Tranel2024; Shyam et al. Reference Shyam, Borgato, Peterson, Dille and Jugulam2021; Yu and Powles Reference Yu and Powles2014). Currently, 20 weed species in the Iberian Peninsula have been confirmed resistant to different ALS inhibitors via TSR and NTSR mechanisms (Portugal and Calha Reference Portugal and Calha2024; Torra et al. Reference Torra, Montull, Calha, Osuna, Portugal and De Prado2022).

Fall panicum (Panicum dichotomiflorum Michx.) is a C4 annual grass native to North America and is considered an alien species in Spain (Rotchés-Ribalta et al. Reference Rotchés-Ribalta, Álvarez, Riera, Andreu, Basnou, Melero, Fuentes, Escobar, Martínez and Pino2022). Mainly found in riparian and ruderal habitats, it is increasingly reported in maize fields (Recasens et al. Reference Recasens, Conesa and Juárez-Escario2020). A major weed in sweet corn (Zea mays L.) and sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) crops in Florida, USA (Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Raiyemo, Arneson, Rosa, Tranel and Werle2022), P. dichotomiflorum has now naturalized in several European countries, including Spain (Barina et al. Reference Barina, Molnár, Somogyi, Szederjesi, Pifkó, Rigó, Mártonffy, Virók and Dudáš2020; Csiky et al. Reference Csiky, Király, Oláh, Pfeiffer and Virók2004; Fried et al. Reference Fried, Chauvel, Munoz and Reboud2019; Maslo and Šarić Reference Maslo and Šarić2016; Nikolić et al. Reference Nikolić, Mitić, Milašinović and Jelaska2013; Sukhorukov Reference Sukhorukov2011). It grows rapidly, competes aggressively, and reaches up to 1.5 m in height (Odero et al., Reference Odero and Sellers2022). This facultative self-pollinator (Urbani Reference Urbani1996) germinates in summer, flowers from September to November, and produces 10,000 to 100,000 seeds per plant (Govinthasamy and Cavers Reference Govinthasamy and Cavers1995). Seeds exhibit strong dormancy (Taylorson Reference Taylorson1980), with germination favored by alternating temperatures of 30/20 °C and shallow burial (1 to 2.5 cm), decreasing to 5% at 7.5 cm (Fausey and Renner Reference Fausey and Renner1997). Although frost-sensitive, it tolerates drought (−0.7 MPa) and shallow flooding, although survival drops sharply beyond 10 cm of water (Chiruvelli et al. Reference Chiruvelli, Sandhu, Cherry and Odero2023; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Shim, Lee and Kang1998).

Yield losses caused by P. dichotomiflorum can reach 60% in sugarcane, 21% to 41% in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.], 25% in maize, and 5% to 10% in rice (Oryza sativa L.) (Southern IPM Center 2004; Harris and Ritter Reference Harris and Ritter1987; Kern et al. Reference Kern, Meggitt and Penner1975; Odero et al. Reference Odero, Duchrow and Havranek2016). This highlights the importance of maintaining effective chemical weed control under Mediterranean conditions. In Spain, nicosulfuron, a postemergence ALS-inhibiting sulfonylurea herbicide, is widely used in maize to control grass and broadleaf weed species. However, repeated use of ALS-inhibiting herbicides has resulted in reduced efficacy against P. dichotomiflorum in several crop fields.

In the summer of 2022, populations of P. dichotomiflorum surviving nicosulfuron applications were reported in two maize fields in Gerb (GB, Catalonia) and Sodeto (SO, Aragón), Spain, where farm records indicated a history of repeated nicosulfuron use. Seed samples were collected from both sites to confirm resistance. This study focuses on these two populations (GB-R and SO-R) with the following objectives: (1) confirm and quantify resistance to the ALS-inhibiting herbicide nicosulfuron, (2) identify known TSR mutations in the ALS gene, and (3) determine the potential involvement of NTSR through enhanced metabolism using P450 and GST inhibitors.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growing Conditions

Seeds were collected in the fall of 2022 from 15 putative P. dichotomiflorum plants that survived consecutive applications of the ALS-inhibiting herbicide nicosulfuron at the recommended field rate of 40 g ai ha–1 in maize fields located in Gerb (GB-R), Catalonia (41.853945°N, 0.831445°E), and Sodeto (SO-R), Aragón (41.889667°N, 0.252472°W). The susceptible population was obtained from seeds collected in maize fields at Torres de Segre (TS-S), Catalonia (41.538139°N, 0.512556°E), and its susceptibility was confirmed in greenhouse experiments (data not shown).

Seeds were scarified with sandpaper and sown in trays filled with moistened peat–substrate (Traysubstrat, Klasmann-Deilmann, Germany). The trays were then placed in a germination chamber (Hotcold-GL, J.P. SELECTA, Barcelona, Spain) set to 30/22 °C (light/dark) with a 12-h photoperiod and a photosynthetic photon flux density of 850 μmol m−2 s−1. Six days after germination, the seedlings were transplanted into 392-cm3 pots containing a 1:1 mixture of loamy soil and peat. Plants were grown in a greenhouse at a constant temperature of 30 °C and a 16/8-h light/dark photoperiod, and irrigated regularly for 1 wk until they reached the 5-true-leaf stage (BBCH 15), at which point herbicide treatments were applied.

Dose Response to Nicosulfuron

Two putatively resistant P. dichotomiflorum populations, GB-R and SO-R, and one susceptible reference population (TS-S) were treated with increasing doses of the ALS-inhibiting herbicide nicosulfuron (Nicteo®, 40 g L–1, SC, KARYON S.L., Spain). The tested doses for the R populations were 0, 10, 20, 40 (1X), 80, 160, 320, and 640 g ai ha–1, whereas for the S population, doses of 0, 0.63, 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 g ai ha−1 were used. The 1X dose is the recommended field rate. Herbicide treatments were applied using a stationary precision bench sprayer calibrated to deliver 200 L ha−1 at a pressure of 215 kPa and a forward speed of 0.9 m s−1 and equipped with a flat-fan nozzle (Low Drift, ISO LD-02-110-CT Yellow Syntal, HARDI International A/S, Taastrup, Denmark).

Each population was evaluated using five replicates per dose (one plant per pot = one replicate) in a completely randomized design. The entire experiment was repeated in two independent runs under identical conditions, conducted in fall 2022 and fall 2023. Twenty-eight days after treatment (DAT), plant survival was visually recorded (0 = live, 1 = dead), and aboveground biomass was harvested (cut at the substrate level) to determine fresh shoot weight reduction relative to untreated controls.

DNA Extraction

Fresh leaf tissue was collected from 10 plants of each of the GB-R and SO-R that survived nicosulfuron applications at rates above the field rate (40 g ai ha–1) and from 10 plants of the TS-S population, including individuals from untreated controls and from plants that survived sub–field rates. Samples were stored at −80 °C until genomic DNA extraction was performed. Subsequently, 100 mg of tissue per sample was used for DNA extraction using the Speedtools Plant DNA Extraction Kit (Biotools B&M Labs S.A., Valle de Tobalina, Madrid, Spain). DNA concentration and quality were measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA), and DNA integrity was assessed with agarose gel electrophoresis.

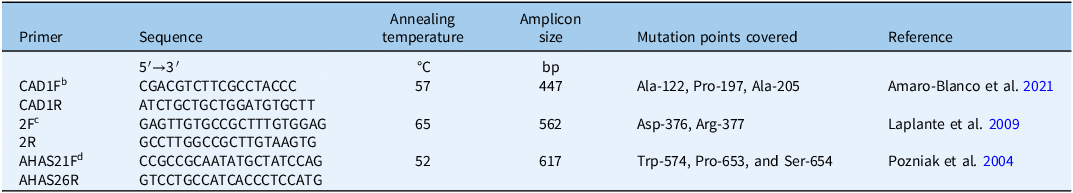

PCR Amplification and Sequencing of ALS Gene

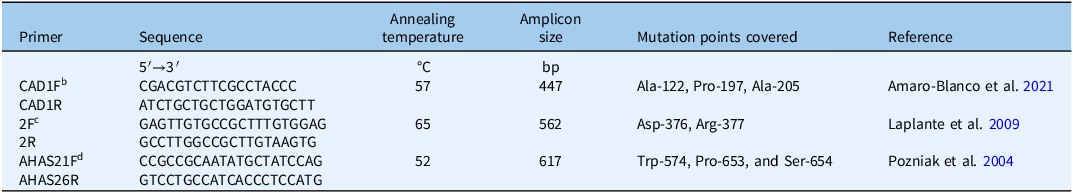

Genomic DNA extracted from resistant (GB-R and SO-R) and susceptible (TS-S) populations was used to amplify and sequence ALS gene regions corresponding to the CAD, F, and BE domains. Three sets of primers were used to target eight conserved codons commonly associated with ALS resistance (Table 1). PCR was performed using an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s of annealing (temperature specific to each primer pair; see Table 1), and 1 min at 72 °C. A final extension was carried out at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were subsequently stored at 4 °C.

Table 1. Primers used for PCR amplification and sequencing of ALS gene regions of Panicum dichotomiflorum.a

a Abbreviations: ALS, acetolactate synthase; bp, base pairs; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

b CAD domain.

c F domain.

d BE domain.

Following PCR amplification, the integrity and size of the resulting amplicons were verified by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with a nucleic acid dye. Gels were visualized under ultraviolet light (320 nm) using the ALPHA DIGI DOC Pro imaging system (Alpha Innotec Corporation, Johannesburg, South Africa). The bands corresponding to the amplicons were purified using the SpeedTools PCR Clean-Up Kit (Biotools B&M Labs S.A.). Purified PCR products were then sent to an external laboratory (STABVIDA, Caparica, Portugal) for Sanger sequencing using both forward and reverse primers.

Sequences were visualized and aligned using Geneious Prime® 2024.0.5 (Dotmatics, Boston, MA, USA) to the Panicum virgatum L. ALS gene (accession: XM_039933797.1) available in the GenBank database (National Center for Biotechnology Information, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

In Vitro ALS Enzymatic Activity Assay

ALS activity was determined by adding 100 µL of enzyme extract to 100 µL of freshly prepared assay buffer containing 1 M potassium phosphate buffer (KH2PO4/K2HPO4) at pH 7, 0.5 M sodium pyruvate, 0.1 M MgCl2, 50 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 1,000 µM flavin adenine dinucleotide, and increasing concentrations of nicosulfuron (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1,000 nM). A 0.04 M K2HPO4 solution was added to adjust the final reaction volume to 220 µL. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 µL of H2SO4, followed by heating at 60 °C for 15 min. Then, 250-µL aliquots of freshly prepared α-naphthol (55 g L−1 in 5 N NaOH) and creatine (5.4 g L−1 in distilled water) were added, followed by incubation at 60 °C for 15 min. The mixture was centrifuged for 2 min at 10,000 rpm, and the absorbance of the reaction product was measured at 520 nm with a spectrophotometer.

The maximum specific ALS activity (nmol acetoin mg−1 TSP h−1) was measured in the absence of herbicide. ALS activity data from all populations were analyzed using the same statistical procedure as in the dose–response experiments. Background absorbance was subtracted using blanks, and ALS activity was expressed as a percentage of the untreated control. The experiment was conducted twice, with three replicates per herbicide concentration and population, following a completely randomized design.

Effect of P450 and GST Inhibitors on Nicosulfuron Resistance

Metabolism-based NTSR has been indirectly detected at the whole-plant level using P450 inhibitors such as malathion, piperonyl butoxide (PBO), and amitrole, or GST inhibitors such as 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (NBD-Cl), tridiphane, and ethacrynic acid (Carvalho-Moore et al. Reference Carvalho-Moore, Norsworthy, Avent and Riechers2024).

Our preliminary tests showed that neither PBO (90%, CAS: 51-03-6, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) at 4,200 g ai ha−1 nor NBD-Cl (98%, CAS: 10199-89-0, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) at 270 g ai ha−1 caused any phytotoxic effects on the seedling growth of P. dichotomiflorum populations when applied alone (data not shown). In contrast, malathion (CAS: 121-75-5, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) applied at 1,000 g ai ha−1—a commonly used dose rate in metabolism studies—caused significant phytotoxicity, markedly reducing seedling growth compared with the other inhibitors, which led to its exclusion from the experiments (data not shown). Consequently, PBO and NBD-Cl at the specified concentrations were selected as metabolic inhibitors for this study.

Plants at the same phenological stage (BBCH 15) from the resistant (GB-R and SO-R) and susceptible (TS-S) populations were treated with or without PBO and NBD-Cl to evaluate their nicosulfuron detoxification capacity. PBO and NBD-Cl were applied, respectively, 1 h and 48 h before the full dose-response assay, using the same herbicide dose range across all populations, as previously described. Each population was evaluated using five replicates per dose (one plant per pot = one replicate) in a completely randomized design. The experiment was conducted twice. Plant survival and aboveground shoot biomass were assessed at 28 DAT, following the methodology described earlier.

Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 10.5.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA, www.graphpad.com). Dose–response and ALS enzymatic activity data were fit using nonlinear regression models. The herbicide dose required to reduce fresh weight and survival by 50% (GR50 and LD50, respectively), as well as the half-maximal inhibitory concentration for ALS activity (IC50), was estimated using a four-parameter logistic model with a variable slope (Equation 1):

$$\rm Y= Bottom + {{(Top-Bottom) \cdot X^{Hillslope}}\over {EC_{50}^{Hillslope}+ X^{Hillslope}}}$$

$$\rm Y= Bottom + {{(Top-Bottom) \cdot X^{Hillslope}}\over {EC_{50}^{Hillslope}+ X^{Hillslope}}}$$

where X is the herbicide rate; Y is the response variable (survival or fresh weight reduction, both expressed as a percentage (%) relative to untreated controls); Top and Bottom are the upper and lower asymptotes (constrained to 100 and 0, respectively); EC50 corresponds to GR50, LD50, or IC50; and HillSlope is the slope of the curve. GR90 and LD90 values were derived from the fitted four-parameter logistic model using the ECanything function. Significant differences in GR50 and LD50 values between populations and treatments were evaluated using the Compare models function, which performs an extra sum-of-squares F test to determine whether dose–response curves differ significantly in their inflection points.

The analysis was performed using individual replicate values at each dose level and for each treatment combination defined by population, herbicide, and metabolic inhibitor (e.g., PBO or NBD-Cl). Separate analyses were conducted for the dose–response experiment and the assay assessing the effect of metabolic inhibitors. Treatment comparisons were performed within each population, and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Normality was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and homogeneity of variance was confirmed using the Spearman rank correlation. The resistance index (RI) was calculated as the ratio of the GR50, LD50, or IC50 values of the R and S populations (RI = R/S).

Herbicide and Metabolic Inhibitor Interaction Analysis

Interactions between nicosulfuron and metabolic inhibitors (PBO or NBD-Cl) were assessed using the Colby equation (Colby Reference Colby1967) to determine whether effects were additive, synergistic, or antagonistic. Fresh weight data from untreated controls, plants treated with PBO, NBD-Cl, or nicosulfuron (40 g ai ha−1), and plants treated with the combination of nicosulfuron and either inhibitor were used. These data were obtained from dose–response and metabolism assays, following the methodology described by Nakka et al. (Reference Nakka, Thompson, Peterson and Jugulam2017), with minor modifications. The expected biomass reduction resulting from the interaction between the herbicide and the metabolic inhibitors was calculated using Equation 2:

where E is the expected biomass reduction (%), X is the observed reduction with PBO or NBD-Cl alone (%), and Y is the reduction with nicosulfuron alone (%). Interactions were classified as synergistic when E was significantly lower than the observed percentage of biomass reduction and antagonistic when it was significantly higher. Differences in the expected and observed values of biomass reduction were analyzed separately using t-tests, with a significance level of P < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Dose Response to Nicosulfuron

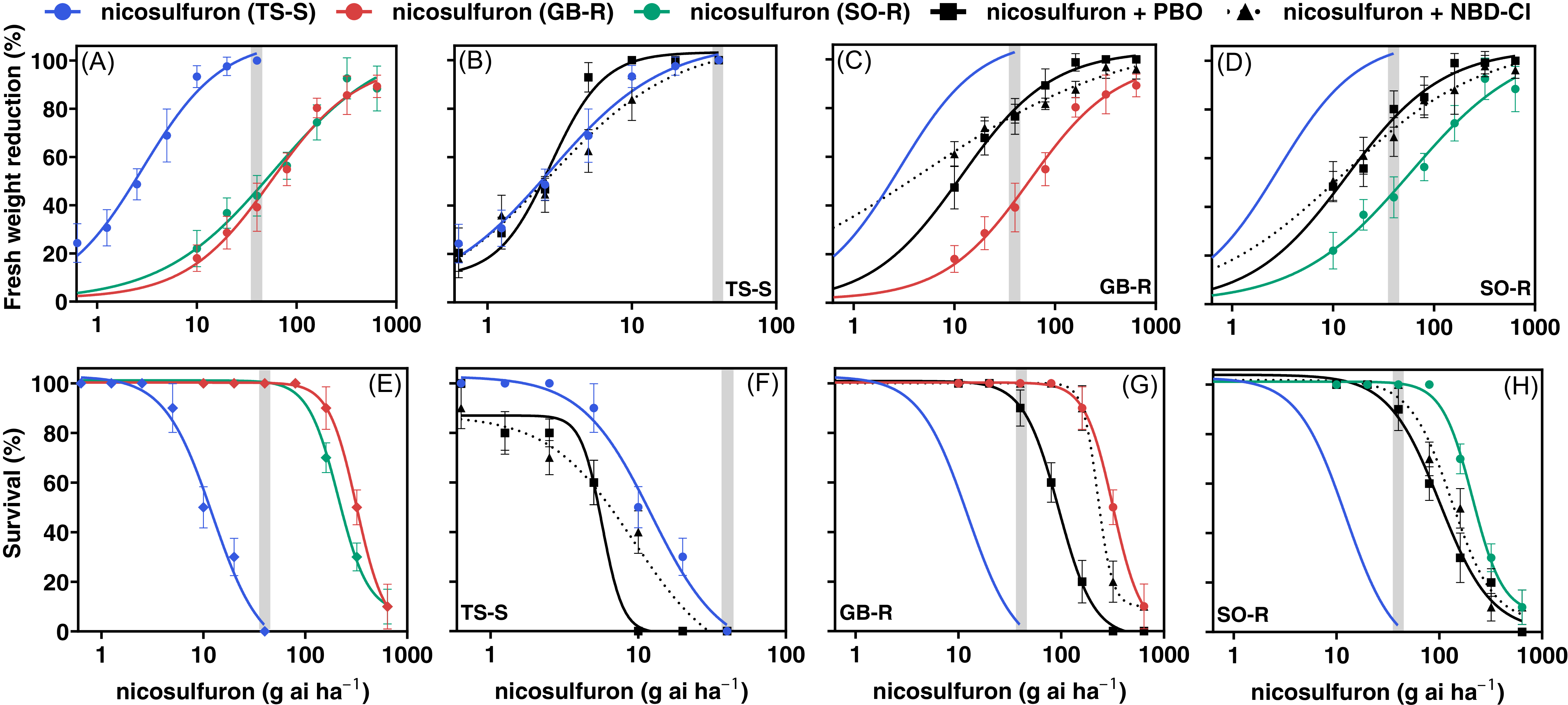

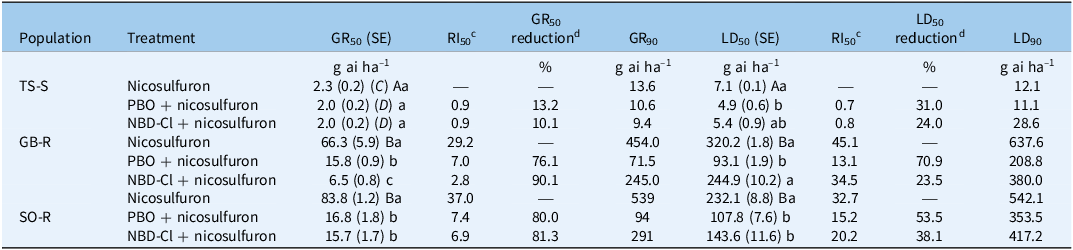

Dose–response assays showed that nicosulfuron effectively controlled the susceptible TS-S population, whereas the resistant populations GB-R and SO-R exhibited similarly high resistance (Figure 1A–E). For the GB-R population, the estimated dose rates required to achieve a 50% biomass reduction (GR50) or 50% control (LD50) were 66.3 and 320.2 g ai ha–1, respectively, which correspond to 1.7 and 8 times the recommended field rate of 40 g ai ha–1 (Table 2). For the SO-R population, the GR50 and LD50 values were 83.8 and 232.1 g ai ha–1, respectively, or 2.1 and 5.8 times the recommended field rate. In contrast, the GR50 and LD50 values of the susceptible population (TS-S) were 2.3 and 7.1 g ai ha–1, well below the recommended field rate. The nicosulfuron GR50 and LD50 RIs for GB-R were greater than 29.2-fold relative to TS-S, while for SO-R, they exceeded 32.7-fold relative to TS-S. A similar pattern was observed for the GR90 and LD90 values (Table 2).

Figure 1. Dose–response curves for fresh weight reduction and survival (%) of resistant (GB-R and SO-R) and susceptible (TS-S) Panicum dichotomiflorum populations from Spain. A and E, Nicosulfuron-only treatments for all three populations. B and F, nicosulfuron alone and following sequential application of piperonyl butoxide (PBO) or 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (NBD-Cl) for TS-S; C and G, for GB-R; and D and H, for SO-R. The solid blue line in C, D, G, and H represents the regression curve of the susceptible population treated with nicosulfuron alone (reference). The gray band indicates the field-recommended rate. Points represent treatment means, and vertical bars indicate ±SE. Curves were fit with a four-parameter logistic model with a variable slope (Equation 1).

Table 2. Summary of parameters describing fresh weight reduction and plant survival, as well as the impact of cytochrome P450 (PBO) and GST (NBD-Cl) inhibitors on nicosulfuron resistance in Panicum dichotomiflorum populations, evaluated at 28 DATa,b

a Abbreviations: P450, cytochrome P450; GST, glutathione S-transferase; DAT, days after treatment; GB-R and SO-R, resistant populations from Gerb and Sodeto, Spain; TS-S, susceptible population from Torres de Segre, Spain; GR, growth reduction; LD, lethal dose; RI, resistance index; PBO, piperonyl butoxide (4,200 g ai ha–1); NBD-Cl, 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (270 g ai ha–1).

b GR50/90 and LD50/90 are the herbicide rates reducing shoot biomass and survival by 50% and 90% (expressed in g ai ha−1). The field rate of nicosulfuron is 40 g ai ha–1. Values in parentheses are SEs. Means within each column followed by different letters are significantly different at P < 0.05. Uppercase letters indicate differences among populations, lowercase letters within populations. Dose–response parameters are provided in the Supplementary Material.

c RI50 values represent the ratio of GR50 or LD50 of resistant to susceptible populations (R/S) for nicosulfuron alone. RI50 values for inhibitor (PBO or NBD-Cl) + nicosulfuron treatments were calculated as (GR50 or LD50 with inhibitor + nicosulfuron)/(GR50 or LD50 in the TS-S population with nicosulfuron alone).

d GR50 and LD50 reduction (%) were calculated relative to nicosulfuron alone (C), compared with inhibitor (PBO or NBD-Cl) + nicosulfuron (D) within each population, using the formula [(C − D)/C] × 100.

Two cases of resistance have been reported for P. dichotomiflorum: resistance to nicosulfuron in Wisconsin, USA, conferred by an Asp-376-Glu TSR mutation (Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Raiyemo, Arneson, Rosa, Tranel and Werle2022), and resistance to atrazine (a photosystem II inhibitor, HRAC 5) in Lleida, Catalonia, associated with enhanced metabolism (De Prado et al. Reference De Prado, Romera and Menendez1995), although this herbicide has been banned in Europe since 2004 (European Commission 2004). The TSR-resistant Wisconsin population, unlike the GB-R and SO-R populations in this study, exhibited lower levels of resistance to nicosulfuron, with RI values of GR50 = 2.8 and LD50 > 12.9 (Nunes et al. Reference Nunes, Raiyemo, Arneson, Rosa, Tranel and Werle2022).

ALS Gene Sequencing and In Vitro ALS Enzymatic Activity Assay

In this study, TSR analysis was conducted at ALS positions Ala-122, Pro-197, Ala-205, Asp-376, Arg-377, Trp-574, Ser-653, and Gly-654, which are known to confer resistance to ALS inhibitors in various weed species (Murphy and Tranel Reference Murphy and Tranel2019). As expected, the susceptible population TS-S showed no mutations at any of these positions, consistent with its high sensitivity to nicosulfuron. Interestingly, neither of the resistant populations, GB-R and SO-R, carried mutations at any of the known resistance-associated positions in the ALS gene (see Supplementary Material).

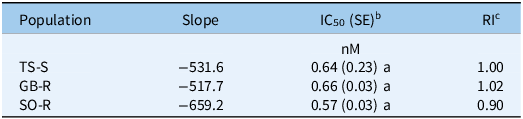

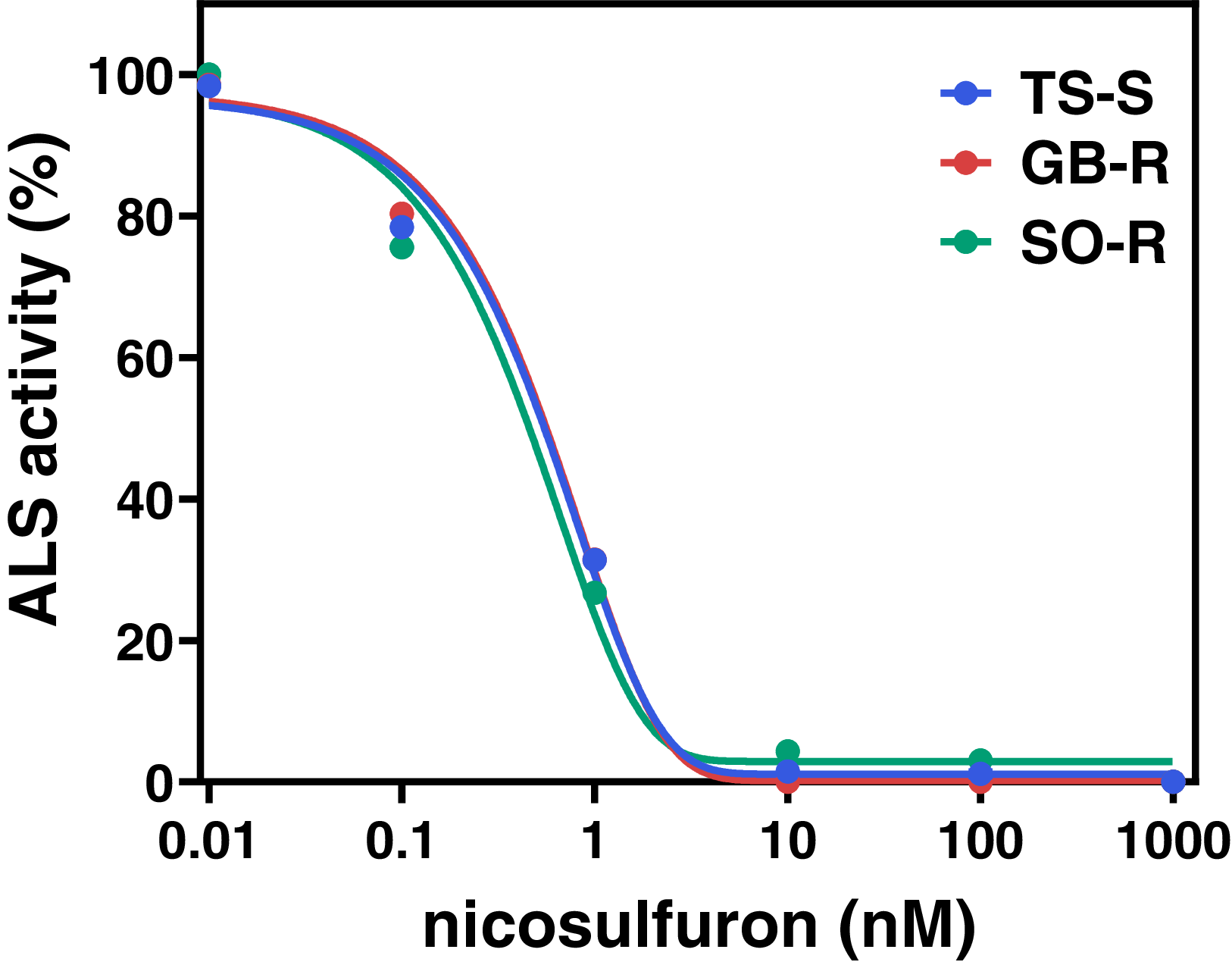

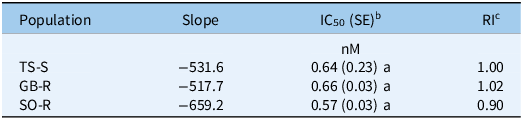

In addition, an in vitro bioassay showed IC50 values of 0.66 nM for GB-R, 0.57 nM for SO-R, and 0.64 nM for TS-S, with no statistically significant differences in basal ALS enzyme activity between the R and S populations (P > 0.05). The corresponding RI50 values, relative to TS-S, were 1.02 for GB-R and 0.90 for SO-R (Table 3). Overall, the ALS inhibition assay results were consistent with the curve-fitting model (Figure 2), confirming that in the absence of target-site mutations in the ALS gene, TSR is unlikely to be responsible for nicosulfuron resistance in both R populations.

Table 3. Estimated parameters and herbicide concentrations required to inhibit 50% of acetolactate synthase (ALS) enzyme activity in R and S populations of Panicum dichotomiflorum from Spain treated with nicosulfurona

a Means within each column followed by different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

b IC50, inhibitory concentration (in nM) required to inhibit 50% of ALS enzyme activity. Values in parentheses indicate the standard error of the mean (SE).

c RI, resistance index, calculated as the ratio of IC50 values of resistant to susceptible populations (R/S).

Figure 2. In vitro acetolactate synthase (ALS) activity in susceptible (TS-S) and resistant (GB-R, SO-R) Panicum dichotomiflorum populations from Spain treated with increasing concentrations of nicosulfuron. ALS activity is expressed as a percentage of the untreated control. Error bars were omitted due to negligible SEs. Curves were fit with a four-parameter logistic model with a variable slope (Equation 1).

Effect of P450 and GST Inhibitors on Nicosulfuron Resistance

Enhanced metabolism-based NTSR has been identified as the cause of resistance in many weed species (Guan et al. Reference Guan, Cao, Zou, Liu, Yang and Ji2023; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Bai, Zhao, Jia, Li, Zhang and Wang2018; Owen et al. Reference Owen, Goggin and Powles2012; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Bai, Bei, Zhao, Jia, Jin, Wang, Wang and Liu2022; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Abdallah, Han, Owen and Powles2009). In this study, pretreatment with PBO and NBD-Cl significantly increased the susceptibility of the GB-R and SO-R populations to nicosulfuron (Table 2; Figure 1A–E).

In the GB-R population, GR50 decreased by 76.1% (to 15.8 g ai ha−1) and 90.1% (to 6.5 g ai ha−1) following PBO and NBD-Cl pretreatments, respectively, compared with nicosulfuron alone (66.3 g ai ha−1). Similarly, in the SO-R population, GR50 decreased by 80.0% (to 16.8 g ai ha−1) and 81.3% (to 15.7 g ai ha−1) after PBO and NBD-Cl, respectively (Table 2; Figure 1C and 1D).

Regarding LD50, values also decreased after inhibitor pretreatments. In the GB-R population, LD50 declined by 70.9% (to 93.1 g ai ha−1) with PBO and by 23.5% (to 244.9 g ai ha−1) with NBD-Cl. In SO-R, LD50 decreased by 53.5% (to 107.8 g ai ha−1) and 38.1% (to 143.6 g ai ha−1) after PBO and NBD-Cl, respectively (Table 2; Figure 1G and 1H). No significant reductions in either GR50 or LD50 were observed in the TS-S population following inhibitor pretreatments (Table 2; Figure 1B–F); however, the percentage reductions in LD50 differed from those observed for GR50 (Table 2).

The GR50 parameter is more sensitive and better reflects sublethal physiological effects, because it is based on continuous biomass data, allowing detection of subtle changes such as partial inhibition of detoxification processes potentially associated with metabolism-based resistance mechanisms (Burgos et al. Reference Burgos, Tranel, Streibig, Davis, Shaner, Norsworthy and Ritz2013; Yu and Powles Reference Yu and Powles2014). In contrast, the smaller percentage reductions in LD50 observed in R populations are consistent with its binary nature (alive/dead) and reflect distinct biological thresholds, as this parameter quantifies lethality and is less sensitive, resulting in smaller proportional reductions. Nevertheless, the reduction in LD50 indicates that metabolic inhibitors decrease the herbicide dose required to control 50% or 90% of the resistant population, consistent with the GR50 results and supporting the potential contribution of metabolism to nicosulfuron resistance.

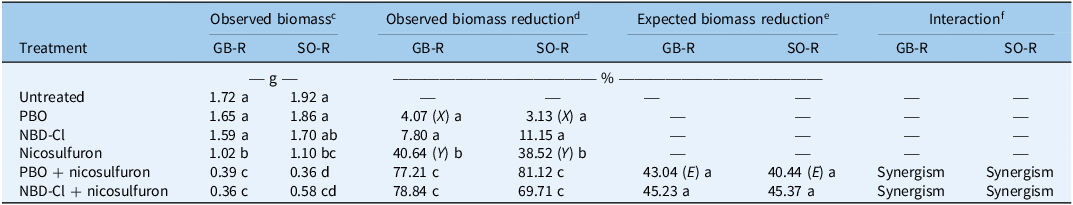

Synergistic interactions between nicosulfuron and metabolism inhibitors were further confirmed using the Colby method, as the observed biomass reduction from combined treatments (nicosulfuron + PBO or NBD-Cl) in both resistant populations significantly exceeded the expected additive effect (Table 4). For the GB-R population, observed shoot biomass reduction ranged from 77% to 79%, exceeding the expected 43% to 45%. Similarly, for the SO-R population, biomass reductions ranged from 70% to 81%, surpassing the expected 40% to 45%.

Table 4. Whole-plant response of Panicum dichotomiflorum to nicosulfuron and its interaction with the metabolic inhibitors PBO and NBD-Cl, evaluated 28 d after treatmenta,b

a Abbreviations: GB-R and SO-R, resistant populations from Gerb and Sodeto, Spain; PBO, piperonyl butoxide (4,200 g ai ha−1); NBD-Cl, 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzofurazan (270 g ai ha−1).

b Different letters within a column indicate significant differences (Tukey’s test, P = 0.05).

c Fresh weight per population and treatment, expressed in grams (g).

d Percentage (%) of fresh weight reduction for each treatment relative to the untreated control of each population.

e Expected biomass reduction (%) for nicosulfuron + PBO or NBD-Cl was calculated by Colby’s equation: E = (X + Y) − (XY/100), where X and Y are the observed biomass reduction (%) with PBO or NBD-Cl and nicosulfuron (40 g ai ha–1) applied alone, respectively.

f Herbicide + inhibitor interaction: synergism if mean value of e < d, and antagonism if e > d.

These findings highlight that enhanced metabolism, mediated by P450 and GST enzymes, may potentially underpin nicosulfuron resistance in the GB-R and SO-R populations. This is the first report of an NTSR mechanism conferring ALS-inhibitor resistance in this species.

In Spain, the natural tolerance of P. dichotomiflorum to atrazine was attributed to its ability to metabolize the herbicide through glutathione and cysteine conjugation. However, no specific resistance mechanisms were identified in the populations studied by De Prado et al. (Reference De Prado, Romera and Menendez1995). A study by Guan et al. (Reference Guan, Cao, Zou, Liu, Yang and Ji2023) suggested that enhanced metabolism, potentially involving P450s and GST enzymes, contributed to nicosulfuron resistance in a population of proso millet [Panicum miliaceum L. ssp. ruderale (Kitagawa) Tzvelev] from China. In general, NTSR in weeds results from metabolic activity that can be mediated exclusively by P450 enzymes (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Zhang, Cui, Bai, Liu and Wang2017; Palma-Bautista et al. Reference Palma-Bautista, González-Torralva, Osuna and Prado2023) or GST enzymes (Cai et al. Reference Cai, Qiu, Wu, Zhang, Jiang, Li, Wang and Liu2022; Dücker et al. Reference Dücker, Zöllner, Lümmen, Ries, Collavo, Beffa, Tranel, Neve and Gaines2020). Additionally, the independent action of both enzyme groups can mediate NTSR (Lei et al. Reference Lei, Zhang, Chen, Jia, Zhao, Wang and Liu2024; Shyam et al. Reference Shyam, Borgato, Peterson, Dille and Jugulam2021; Varanasi et al. Reference Varanasi, Brabham, Nandula, Jugulam, Nadler-Hassar, Rangani, Ribeiro, Reddy, Duke, Bond, Shaw and Burgos2018; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Qiu, Qian, Chen, Bai and Liu2024; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Liu, Wang, Bai, Zhao and Liu2023). A coordinated enzymatic detoxification pathway for xenobiotics involving P450s and phase II GSTs has been described in plants (Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Tranel and Stewart2007), and a similar coordinated process has been characterized as an evolved metabolic resistance mechanism in waterhemp [Amaranthus tuberculatus (Moq.) Sauer] (Strom et al. Reference Strom, Hager, Concepcion, Seiter, Davis, Morris, Kaundun and Riechers2021).

These findings highlight the complexity of herbicide detoxification pathways in plants. Further research on gene expression and metabolomics in GB-R and SO-R populations is critical to identify the specific genes involved in nicosulfuron resistance and to characterize the metabolites, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of the detoxification pathways involved.

In summary, this study provides the first evidence of nicosulfuron resistance in P. dichotomiflorum, associated with enhanced metabolism as a potential NTSR mechanism. Dose–response assays revealed high resistance levels in the GB-R and SO-R populations, which were significantly reduced following pretreatment with the P450 (PBO) and GST (NBD-Cl) inhibitors. Furthermore, ALS gene sequencing did not detect mutations at positions previously associated with ALS-inhibitor resistance, ruling out a TSR mechanism. These findings highlight enhanced metabolism as a key resistance mechanism in this species and underscore the need for integrated weed management strategies to prevent the spread of resistant populations in Spanish agricultural systems.

Early detection of herbicide-resistant weed biotypes is crucial for managing resistance in European agriculture. Regulatory restrictions and bans on active ingredients with low resistance risk, driven by environmental and public health concerns (European Parliament and Council 2009), have reduced chemical control options and herbicide diversity. This situation has increased reliance on high resistance risk herbicides, such as ALS inhibitors, thereby increasing selection pressure and accelerating the spread of resistant biotypes (Montull and Torra Reference Montull and Torra2023). Consequently, the implementation of integrated weed management (IWM) practices is essential, with crop rotation representing a particularly effective strategy to reduce resistant populations (Torra et al. Reference Torra, Mora, Montull, Royo-Esnal, Notter and Salas2024), thereby underscoring the importance of diversified approaches in sustainable weed management.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/wsc.2025.10072

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Isidro Cambra (Sertagro S.L.) and the Servei de Sanitat Vegetal de Lleida for providing the plant material. We are also grateful to Maria Casamitjana for her valuable technical assistance.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain and the State Research Agency (Agencia Estatal de Investigación, AEI), through the 2020 Call for R&D Projects (RTI), within the National Program for Research, Development and Innovation focused on Societal Challenges (Grant PID2020-113229RB-C42).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.