THE TERRITORY AND ITS ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION

As a result of archaeological investigations in the extreme south-westerly part of the Republic of Albania in the early 2000s, two churches have been discovered in close proximity to one another (less than 4 km as the crow flies), which are of similar architectural typologies, and similar mesobyzantine and medieval datings (Muçaj et al. Reference Muçaj, Lako, Hobdari and Vitaliotis2004; Muçaj, Hobdari and Vitaliotis Reference Muçaj, Hobdari and Vitaliotis2005). The churches also share another characteristic, that of having contained one coin hoard each, abandoned in situ in the fourth and fifth decades of the fourteenth century. Our contribution aims at presenting and explaining this numismatic material in its archaeological and historical context.

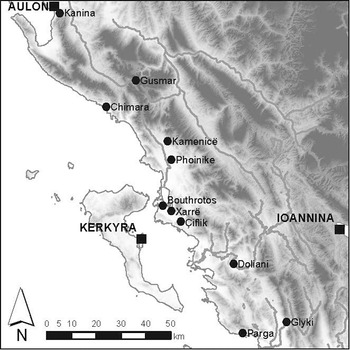

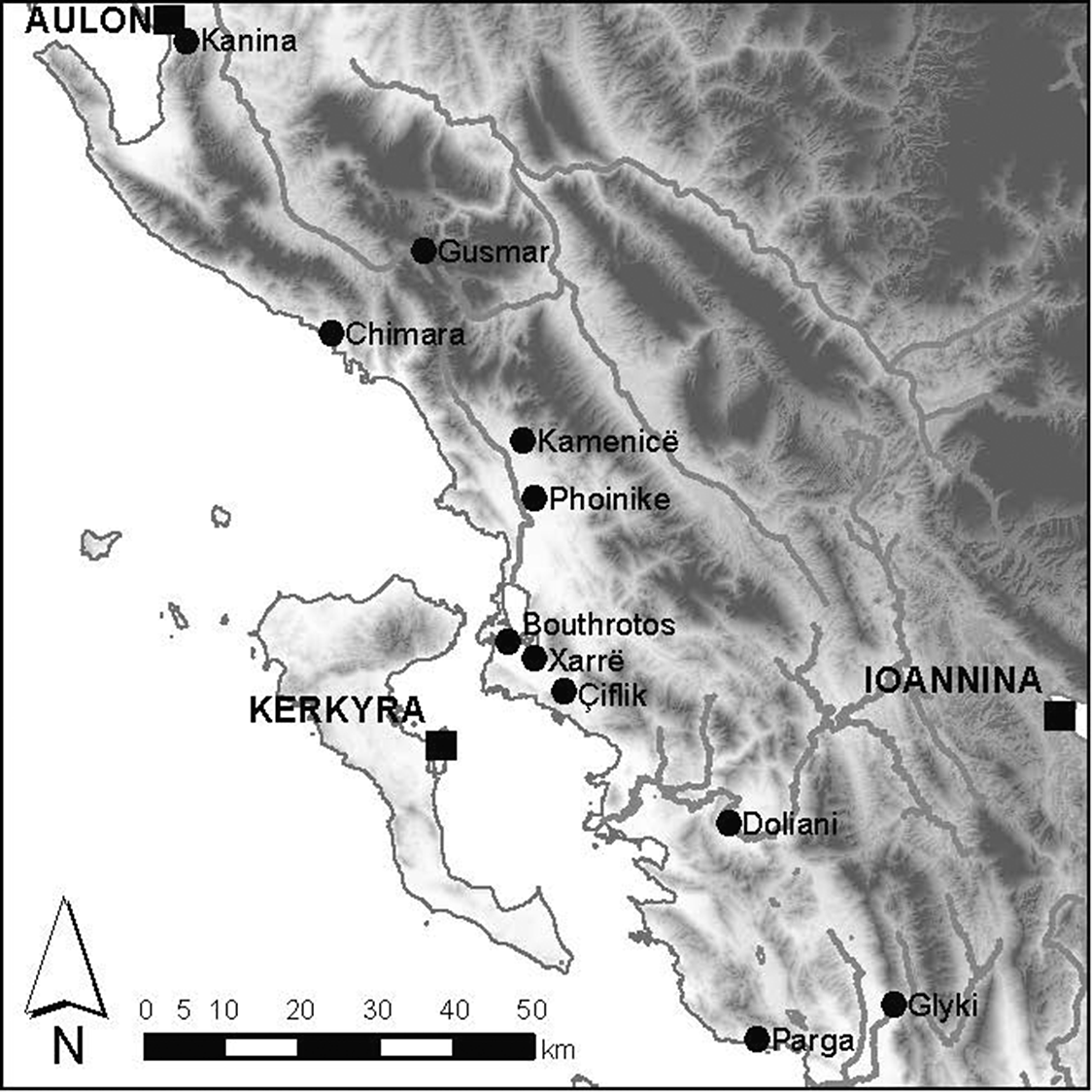

The geographical coordinates are as follows. In modern terms, the finds were made in the county of Vlorë (known in Greek as Aulon/Avlona; Valona in Italian). More precisely, after the administrative reforms of 2015, in the most westerly part of the Delvinë (Greek Delvino) Municipality, close to the town of Sarandë (Agioi Saranda/Santi Quaranta). The hoards were found during campaigns in the medieval churches of Shën Jan (that is to say St John, from which derives the modern name of the local village Shijan) and Peshkëpi in the village of Nivicë Bubar. The geographical locations are given in Figs 1 and 2. The two coin hoards are now conserved in the Numismatic Collection, Instituti i Arkeologjisë, Tirana.

Fig. 1. The immediate area of investigation with mentioned locations and positions of the two churches.

Fig. 2. The area between Aulon, Ioannina and Kerkyra, with mentioned locations.

In Antiquity, this area had known a pronounced urban development characterised by numerous towns and smaller settlements, the most important amongst which were Bouthrotos (Butrint in English, Butrinti in Albanian, Butrinto in Italian), Phoinike (Finiq in Albanian, Fenice in Italian) and Onchesmos (Onhezëm/Ankiasm in Albanian, which in medieval and modern times took the name of Agioi Saranta or Santi Quaranta, i.e. Sarandë). In mesobyzantine and medieval times, the area occupied the central coastal part of the ‘Vagenetia’, facing the great island of Kerkyra (known internationally as Corfu or Corfù, Korfuzi in Albanian). There are a number of other medieval locations around our two churches. Of these, there are two for which the contempory thirteenth- and fourteenth-century documentation is the richest: the monastery of Mesopotamon (of Shën Koll, that is to say St Nicholas) and, beyond the lake of Bouthrotos, the homonymous town. The akropolis of ancient Phoinike and the built-up area on its westerly slopes are even closer to our two churches (at respectively 2 and 6km). Nonetheless, the medieval importance of Phoinike, and indeed of the settlements in the entire area stretching from this akropolis westwards towards the Ionian Sea, remain to be defined. We can be certain that our two churches were not located within settlements, but had a rural character, maybe equidistant in medieval times to more than one modest settlement.

During the entire medieval period, even though the total number of attested settlements was perhaps much reduced when compared to earlier times, a fair quantity of churches and monasteries were constructed within a tight geographical space. Amongst these, beside the already cited Mesopotamon, Shën Jan, and Peshkëpi of Nivicë Bubar, the following can be pointed out: the late antique and medieval churches on the akropolis of Phoinike, the monastery of Kamena near Delvinë, the 12 churches of the medieval hamlet of Kamenicë, including the monastery of Jominai, and the churches of Shën Mërisë (St Mary) and Shën Mëhill (St Michael) in the hamlet of Kostar. Somewhat further away lies the town of Bouthrotos with its churches and the basilica of Çiflik.

Shën Jan

The remnants of the church of Shën Jan lie on a small hill just to the north-west of the territory of the ancient city of Phoinike, close to the banks of the river Kalasë. Close by, a new village going by the name of Shijan established itself in the twentienth century, which evidently made reference to this church, situated halfway between the main settlements of the area, Nivicë Bubar and Phoinike.

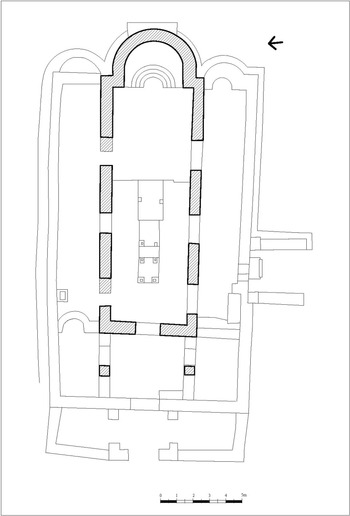

The excavation campaign of 2001–3 brought to light a rich archaeological documentation which allows a reconstruction of the various building phases and provides a general idea of the architecture.Footnote 1 The plan of the church is well preserved (Fig. 3); the construction techniques of the walls, the liturgical furnishings, the architectural sculptures, the decorative features, the wallpaintings, the paving in opus sectile, and finally the archaeological materials point in combination to four phases of construction.

Fig. 3. Plan of the church of Shën Jan.

Initially, the building was constructed as a narthexed church, but was later transformed into a three-aisled basilica (in phase two). The addition of an exonarthex defines a third phase. The demolition of a part of the church, that part directly to the north of the narthex, and the consolitation of the central part of the church into a smaller chapel represent a fourth phase. The archaeologists propose the following chronologies: ninth to tenth centuries for the first phase; beginning of the eleventh for the second phase; thirteenth century for the third. Amongst the churches of Albania, Shën Jan preserves the liturgical installations in a remarkable fashion: the synthronon, the ciborium, the parapet of the sanctuary and the ambon, arranged on an axis and connected to a soleas, are all in the tradition of Constantinople and show direct metropolitan patronage. Inside the church, and especially in the side naves, a large number of vaulted tombs dating to the early church were found. In later phases tombs there took the form of sarcophagi. The excavations of the church of Shën Jan brought to light innumerable fragments of frescoes in three different strata (Muçaj et al. Reference Muçaj, Lako, Hobdari and Vitaliotis2004, 115–17).

The ceramics, meanwhile, are rather poor and are composed principally of pithoi, amphoras, bottles, tableware, and kitchenware. In term of construction materials, apart from bricks and tiles, so-called ‘bottles’ have been found, that is to say amphoras used to improve the acoustics inside the church (Xhyheri Reference Xhyheri2013), and glazed vases with decorative usage.

The narthexed church, of rectangualar shape with a lenght of 14.50 m and a width of 4.95 m, had a semicircular apse and a monumental prothyrum in the west. The apse of the first phase had a three-stepped semi-circular synthronon leading up to a wooden platform. It is currently impossible to say whether the other internal features – the ciborium, the parapet of the sanctuary and the ambon – belonged to the narthexed church or instead to the second phase, when the church was transformed into a basilica.Footnote 2

The 12 coins of the Shën Jan coin hoard – part (1) of the catalogue contained in this contribution (nos 1–12), were found in the northern nave, below tiles in a mixed stratum, stuck to one another in a cylindrical fashion, which makes one believe that they were originally held in wax cloth. The stratum holding the hoard itself contained ash.

After the destruction of the building, which presumably occurred in short succession to the final abandonment of the coin hoard, as we shall see, the basilica was transformed into a small church and then used for a brief period within the second half of the fourteenth century. After definitive abandonment of the church, the north and south aisles were used for burials, which necessitated, amongst other things, that the paving was destroyed.

Nivicë Bubar

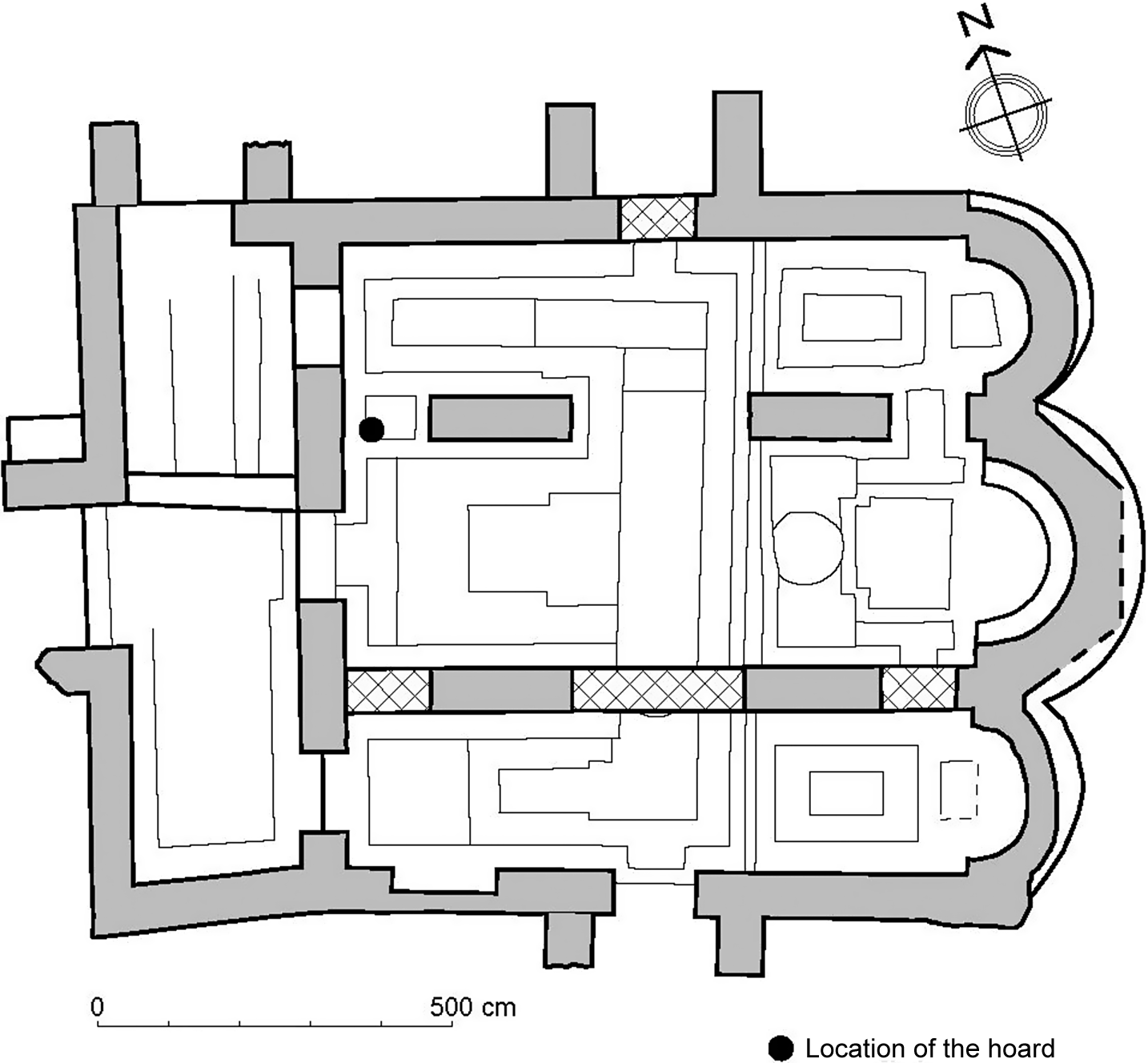

The place in which the ruins of this church are located is known to the inhabitants according to the microtoponomastic ‘Peshkëpi’, a name used in medieval times for episcopal sees and often preserved to the present day. The exact position of the site is located between the small village of Nivicë Bubar and the church of Shën Jan. The church is of basilica type with three aisles and apses, narthex, chancel, prothesis, and diakonikon. The maximum length and width, including the apses, are 16 m and 12.4 m, respectively. The central apse has a synthronon (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Plan of the church of Nivicë Bubar. Map drawn by E. Hobdari in 2004.

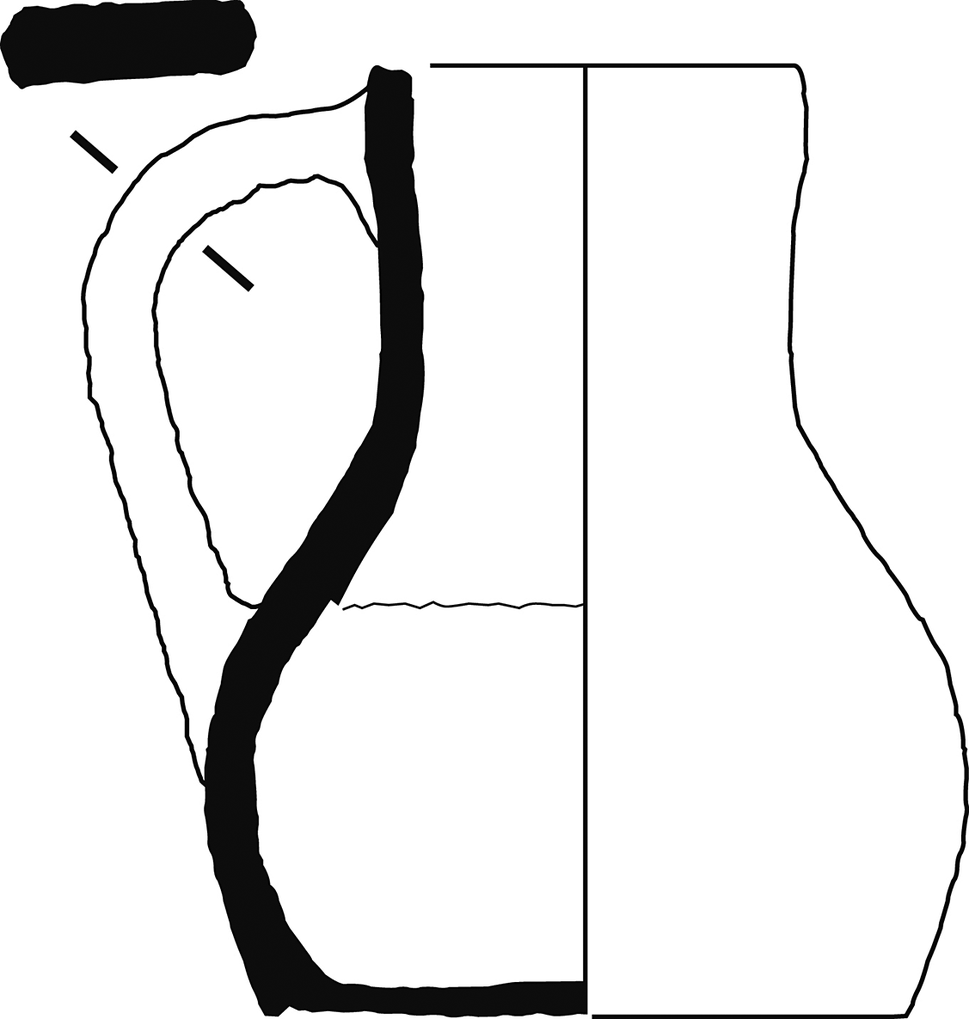

All the floors of the basilica were finished in opus sectile with geometric motifs, and the walls were frescoed. A coin hoard of 154 pieces, corresponding to part (2) in our catalogue (nos 13–166), was contained in a ceramic vessel with signs of burning. The hoard was brought to light during the 2003–4 campaign. See Fig. 5 for a view of the hoard in situ and Fig. 6 for the ceramic vessel. Stray coin finds, found in the church of Nivicë Bubar, listed under part (3) of the catalogue (nos 167–171), were found in different parts of the church and were not part of the hoard.

Fig. 5. The coin hoard of Nivicë Bubar in situ.

Fig. 6. Sketch of the ceramic vessel which contained the coin hoard of Nivicë Bubar.

Fig. 7. Coins, nos 1–33.

Fig. 8. Coins, nos 34–68.

Fig. 9. Coins, nos 69–101.

Fig. 10. Coins, nos 102–136.

Fig. 11. Coins, nos 137–171.

The data gathered during the excavations give some internal clues as to the date of construction of the church, while many architectural details also provide important chronological links to other churches of the area, such as Shën Jan,Footnote 3 Çiflik,Footnote 4 one of the churches of Kamenicë (Ristani et al. Reference Ristani, Muçaj, Xhyheri and Ruka2013; Ristani, Muçaj and Xhyheri Reference Ristani, Muçaj and Xhyheri2014), the medieval church of Phoinike (Hobdari Reference Hobdari2017), and the basilica of St Donatos in Glyki/Thesprotia (Pallas Reference Pallas1971, 250, fig. 19), all of which date between the tenth and thirteenth centuries.

Although the question of the precise chronology of the church remains open, a post quem of the late twelfth century for its construction can be given in general terms. The complicated history which characterises the area between the twelfth and fourteenth centuriesFootnote 5 does not propose an obvious period when, or motivation as to why, this small basilica might have been used by the bishop of Bouthrotos – if this indeed is the explanation for its name. More secure, however, as we shall see, is the date at which the church was destroyed and abandoned.

As an important comparative case, we must cite the settlement of Kafaraj in the county of Fier in central coastal Albania: near the cemetery of the village, traces of a late antique church can be found which evidently continued to be used in medieval times. Certain architectural finds have been made there, notably part of an iconostasis, tiles of the fifth and sixth centuries, fragments of wall painting, medieval ceramics, and two rings (one bronze, the other silver). Also, investigations in this church seem to have produced a coin hoard, namely of 131 Venetian silver grossi, the abandonment of which has been dated to the early years of the 1340s.Footnote 6

THE MONETARY DOCUMENTATION

As has already been indicated, the monetary documentation can be divided into three parts, that is to say: (1) the coin hoard of Shën Jan; (2) the coin hoard of Nivicë Bubar; and (3) the stray finds from Nivicë Bubar.Footnote 7 The total, 12 + 154 + 5 coins, is presented here as a continued numerical sequence (nos 1–171). In line with denomination, issuing authority, epigraphy, and internal typology, we have divided the coins into 19 issues (Issues 1–19). It should be stressed that these divisions and their sequence are devised in order to facilitate discussions and cross-referencing within this presentation.

With respect to the coins’ legends, we should point out that it is clear that the majority of the coins discussed here adhere to the standard legends indicated at the beginning of each issue. Whenever this is not the case – mostly for the Artan deniers tournois of group IOΓ – a note has been made in the comments.

It is of further note that the five coins of part (3), found isolated at Nivicë Bubar, all belong to issues of the mint of Arta, which are already attested in the hoard from the same location: Issues 8, 13, and 15. In terms of denominations, only two are represented, Venetian soldini of the Venice mint (nos 4–12) and deniers tournois of the mints of Clarentza for Achaia (nos 1–3 and 13–15), of Arta for Epiros (nos 16–161 and 167–171), and of unknown mints in the case of the counterfeit deniers tournois (nos 162–166).

CATALOGUE

(1) Hoard of Shën Jan

Principality of Achaia, mint of Clarentza, deniers tournois, billon

Issue 1 (1 coin)

-

William II of Villehardouin (1246–78)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1388, GV223

-

Obverse: +G PRINCE ACh, cross potent

-

Reverse: +CLARENTIA, castle

Issue 2 (1 coin)

-

Florent of Hainaut (1289–97)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1396, FHA1

-

Obverse: +FLORЄNS P ACh, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ CLARЄNCIA, castle

Issue 3 (1 coin)

-

Philip of Taranto (1304/6–13)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1409, PTA

-

Obverse: +PhS P ACh TAR D R, cross potent

-

Reverse: +D.ʹCLARЄNCIA, castle

Republic of Venice, mint of Venice, soldini, silver

Issue 4 (8 coins)

-

Francesco Dandolo (1329–39)

-

Papadopoli Reference Papadopoli1893, pl. IX:14

-

Obverse: +FRA DANDVLO DVX, kneeling doge left, holding in both hands the banner

-

Reverse: +S MARCVS VЄNЄTI, nimbate lion, rampant left, holding banner in front legs

Issue 5 (1 coin)

-

Bartolomeo Gradenigo (1339–42)

-

Papadopoli Reference Papadopoli1893, pl. X:5

-

Obverse: +BA GRADONIGO DVX, kneeling doge left, holding in both hands the banner

-

Reverse: +S MARCVS VЄNЄTI, nimbate lion, rampant left, holding banner in front legs

(2) Hoard of Nivicë Bubar

Principality of Achaia, mint of Clarentza, deniers tournois, billon

Issue 6 (3 coins)

-

Robert of Taranto (1332–64)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1423–4, RAA1

-

Obverse: +ROBT P ΛChЄ, cross potent

-

Reverse: +CLΛRЄI ICIΛ, castle, gothic N under the castle

Lord and despot in Epiros at Arta, mint of Arta, deniers tournois, billon or copper

John II of Kephallenia, Zakythos, Leukas and Ithaka (1323–36/7)

Issue 7 (1 coin)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469–70, IOA var1

-

Billon issue, legends composed from large and seriffed letters formed with multiple punches

-

I to the left of the castle. O to the right of the castle

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 8 (24 coins)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469–70, IOA var2

-

Billon issue, legends composed from large and seriffed letters formed with multiple punches

-

Three dots to the left and right of the castle. O underneath the castle

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 9 (2 coins)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469–70, IOA var3

-

Billon issue, legends composed from large and seriffed letters formed with multiple punches

-

Spur rowel underneath castle, dot to the left, a helmeted bust turned left to the right of the castle. The obverse legend ends with a dot

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 10 (2 coins)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469–70, IOA var4

-

Billon issue, legends composed from large and seriffed letters formed with multiple punches

-

S to the left or right of the castle, S in the quandrants of the large reverse crossFootnote 8

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 11 (2 coins)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469–70, IOA var5

-

Billon issue, legends composed from large and seriffed letters formed with multiple punches. The letter A has a particular shape

-

Lis to the left of the castle

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 12 (6 coins)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469–70, IOA var6

-

Billon issue, legends composed from large and seriffed letters formed with multiple punches

-

Star to the left of the castle, dot to the left: Baker Reference Baker2020, 1471, IOΓ var2 (5)

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 13 (48 coins)

-

Lambros Reference Lambros1871, 498, pl. XI:4; 1880, 13, no. 4 (Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469–70, IOA var7)

-

Billon issue, legends composed from large and seriffed letters formed with multiple punches

-

No symbols to the left and right nor underneath the castle

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 14 (1 coin)

-

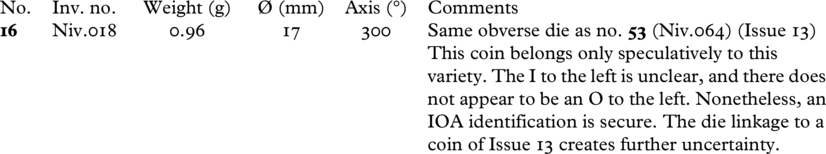

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469–70, IOB

-

Billon issue with small angulated letters, made from single punches, with a particular S-punch in the shape of an 8

-

B to the right of the castle

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 15 (46 coins)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469, IOB bis

-

Billon issue with small angulated letters, often made from single punches, with a particular S-punch in the shape of an 8. This variety of IOB often displays sporadic abbreviations (for example DΛRTΛ…) or missing letters (for example DЄPOTVS or CΛSTV/CΛTV) or erroneous lettering (for example CΛTΛTΛ). Letters are also often malformed, for example D or R in the shape of I. The big cross potent is often broad with triangular arms

-

No symbols around the castle

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 16 (7 coins)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469, IOΓ var2

-

Low-grade billon or copper issue, often with incorrect legends which resemble only vaguely +IOhS DЄSPOTVS/+DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, or devoid of any sense

Issue 17 (5 coins)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469, IOΓ var2

-

Low-grade billon or copper issue, often with incorrect legends which resemble only vaguely +IOhS DЄSPOTVS/+DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, or devoid of any sense

-

Lunettes similar to Baker Reference Baker2020, 1470, IOΓ var2 (2), but underneath the castle

Issue 18 (1 coin)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469, IOΓ var2

-

Low-grade billon or copper issue, often with incorrect legends which resemble only vaguely +IOhS DЄSPOTVS/+DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, or devoid of any sense

-

Dot to the right of the castle, uncertain symbol or merely a die break to the left

Contemporary counterfeits, uncertain issuers, uncertain mints, deniers tournois, billon or copper

Issue 19 (6 coins)

-

All coins imitate the issues of John II of Kephallenia, Zakynthos, Leukas, and Ithaka, lord and despot in Epiros at Arta (1323–36/7), mint of Arta

(3) Stray finds from Nivicë Bubar

Lord and despot in Epiros at Arta, mint of Arta, deniers tournois, billon or copper

John II of Kephallenia, Zakythos, Leukas and Ithaka (1323–36/7)

Issue 8 (1 coin)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469–70, IOA var2

-

Billon issue, legend composed from large and seriffed letters formed with multiple punches

-

Three dots to the left and right of the castle. O underneath the castle

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 13 (2 coins)

-

Lambros Reference Lambros1871, 498, pl. XI:4; Reference Lambros1880, 13, no. 4 (Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469–70, IOA var7)

-

Billon issue, legends composed from large and seriffed letters formed with multiple punches

-

No symbols to the left and right nor underneath the castle

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

Issue 15 (2 coins)

-

Baker Reference Baker2020, 1469, IOB bis

-

Billon issue with small angulated letters, often made from single punches, with a particular S-punch in the shape of an 8. This variety of IOB often displays sporadic abbreviations, or missing letters, or erroneous lettering. Letters are also often malformed, for example D or R in the shape of I. The big cross potent is often broad with triangular arms

-

No symbols around the castle

-

Obverse: +IOhS DЄSPOTVS, cross potent

-

Reverse: +DЄ ΛRTΛ CΛSTRV, castle

NUMISMATIC DISCUSSION

The monetary documentation for the churches of Peshkëpi-Nivicë Bubar and of Shën Jan is of foremost interest and importance, and indeed, in the first of these cases, unique. In combination the data demonstrate that monetisation of the area was ensured from two sources in the first half of the fourteenth century: the republic of Venice to the north and the mints of the western Epirote and Achaian seaboard to the south. The hoard from Nivicë Bubar (2) is the singlemost important and largest nucleous of coins of Arta that has to date been found and described, and it allows one to reconstruct production at that mint in a decisive fashion. The hoard from Shën Jan (1), in the meantime, offers a particularly early testimony – and this regards the entire Greco-Albanian area – for a new Venetian denomination of the 1330s (the soldino: Stahl Reference Stahl2000, 41–68), a denomination which was overvalued and therefore particularly advantageous to Venetian colonial administrations, and also to the traders of the republic.

With respect to Shën Jan, the deniers tournois present in this hoard are too early to help us establish adequately a terminus post quem of deposition (nos 1–3, Issues 1–3). On the other hand, the soldino of Doge Gradenigo (no. 12, Issue 5) dates not merely precisely to the years 1339–42, but its uniqueness and the lack of subsequent issues of Doge Andrea Dandolo (1343–54) show that numismatically, especially with later hoards in mind (for example Petsouri 1997 from the Peloponnese: Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 158), that the Shën Jan hoard was with great likelihood abandoned in the middle years of the 1340s.

In the entire Greco-Albanian area there are merely, in line with our current knowledge, two or three soldino hoards concealed earlier than that of Shën Jan: one from the modern Greek capital, Athens Roman Agora (Lytsika) 1891A (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 149), another from Phthiotis (Elateia before 1885: Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 150), both mid-1330s hoards, and a third from Messenia, which may even date a little earlier (Mesochori: Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 146). Two to four further hoards contain issues of Doges Francesco Dandolo and Bartolomeo Gradenigo and date therefore in close proximity to Shën Jan, namely Delphi 1894Γ (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 154) and Lepenou (Aitolia and Acarnania) 1981 (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 155). A lesser known and studied hoard is Sikyon 1938, probably a third such hoard (Baker Reference Baker2020, 427). Even less certain, though of great importance in the context of Shën Jan, is a hoard which is neither properly preserved nor documented, from the location of Gusmar, a small settlement belonging to Tepelenë Municipality, at a distance of c. 35 km north-north-west of Shën Jan, which also appears to have been dominated by soldini in the name of Doge Francesco Dandolo (1329–39).

From this list we can understand that the new Venetian soldino was first diffused in different locations, mostly unrelated to Venetian colonial activities (concentrated in this period in Messenia and Euboia), and more likely fostered by a coastal location and by trade routes which linked the Ionian with the Aegean, passing either via the northern Peloponnese and the Gulf of Corinth or via the more southerly connection. Also, the Shën Jan hoard needs to be understood in such a context, as we shall see in due course.

The hoard of Nivicë Bubar of 154 deniers tournois contained 145 coins of the mint of Arta (nos 16–160, Issues 7–18). Only three additional coins belong to a known mint, that of Clarentza for the principality of Achaia (nos 13–15, Issue 6). This renders the hoard of Nivicë Bubar atypical, even in the south-western Albanian context. In regular hoards the issues that usually dominate are those of the mints of Clarentza, Thebes (for the duchy of Athens), and Naupakots. The latter two are not even present at Nivicë Bubar. In the absence of these very common coins, the rather significant presence of counterfeit issues (nos 155–159, Issue 17) is additionally quite unusual. These coins appear to be in the name of John II, lord and despot at Arta, but in reality they are not from the official Arta mint and were presumably made by privates in unspecified locations in Epiros.

Our main attention is therefore devoted to the actual official issues of that mint. A couple of words of clarification regarding its issuer are required: Kiesewetter (Reference Kiesewetter, Ortalli, Ravegnani and Schreiner2006, 340–2) was the first to gather systematically the contemporary designations for the Pugliese dynasty which ruled the southern Ionian islands from the twelfth century, and which then substantially expanded its domain into the Epirote mainland in the early fourteenth. He established that the surname ‘Orsini’, often applied by modern historiography, and in fact used by all numismatists writing on the coinages in question, is fanciful and indeed incorrect. In the sources of the time, the various rulers of this dynasty are referred to (including by themselves) as being ‘of’ specific islands, usually Kephallenia and Zakynthos, sometimes with the addition of Leukas and Ithaka, in different combinations. The issuer of the coins in question should therefore be known not as ‘John II Orsini’, but as John II of Kephallenia, Zakynthos, Leukas, and Ithaka (short: ‘of Kephallenia’). In Epiros during the period 1323–36/7 he was initially lord, later despot.

The coinage of Arta has been known scientifically for more than 150 years, though has generally inspired few detailed treatments (generally, see Metcalf Reference Metcalf1979, 254, 287). Until a few years ago, the only typological discussions available were those of Lambros (Reference Lambros1871), repeated by Schlumberger (Reference Schlumberger1878) and then again by Lambros (Reference Lambros1880). The tournois of Arta had great diffusion in Bulgaria, as has been noted by historians and archaeologists in that country.Footnote 9 Only in the year 2020 has an attempt been made to consider in greater detail the extant numismatic data pertaining to the Arta coinage, to offer a broader vision as well as to make some typological divisions based on actual specimens (Baker Reference Baker2020, 1466–76). The data already assembled by Lambros proved to be important, as much as access to certain collections and finds, foremost amongst which are the hoards of Roussaiïka Agriniou 1966 (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 127), Romanos Dodonis 1963 (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 130), Ermitsa 1985A (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 140), Naupaktos 1976 (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 148), and Athens Roman Agora (Lytsika) 1891A (see above). All in all, Baker (Reference Baker2020) was able to draw on no more than 100 specimens of the Arta mint, half of which belonging to the late and inferior group IOΓ, which was hoarded in good quantities at Roussaiïka and Naupaktos. It was therefore assumed that also the current hoard of Nivicë Bubar, listed in the catalogue at the time, though without direct knowledge of the specimens (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 147), should also have been dominated by the same IOΓ. Now, after the complete examination of this hoard, which has also increased the number of Artan deniers tournois available to science by 150%, important conclusions can be drawn not merely for the hoard itself, but for this coinage as a whole.

A detailed consideration of an issue from a single mint, with a confined number of specimens, merits in ideal circumstances a complete die study. Such an exercise offers the key to the internal structure and development of the coinage, especially its chronological evolution, as well as providing quantitative information. Such a study was therefore conducted for nos 16–160. All the coins in this range were compared to one another to determine whether or not they were produced from the same die. These checks were made for the obverses and the reverses. Notwithstanding the bad production quality of the coins and the bad state of the specimens themselves, this binary choice of determining a common or different die could in each case be made without ambiguity, since enough diagnostic features were present. We can therefore conclude that the great number of coins in the hoard were made from different dies, with the exception of a few (nos 16–18, 53–61, 102–108) that were produced from at least one common die (obverse and/or reverse). This scarcity of die links, or, viewed differently, this great presence of dies featuring only once in the sample, is in itself a noteworthy discovery about the presence and usage of the coinage in the area, although this does not help the initial aim of ordering the series. The large number of dies used for the production of the Artan denier tournois coinage also demonstrates that this coinage was much larger than might have been expected.

The die and typological studies result in the following conclusions:

-

• The separation into the groups IOA, IOB, IOΓ, as proposed by Baker (Reference Baker2020), has been confirmed. The die study, that is to say the near absence of die links across groups, shows a clear and conscious separation. The divisions are qualitative and chronological. The entire coinage can be located within the years of activity of its issuer, John II, who ruled the wider Epirote region from his ‘capital’ Arta from 1323 to his death in 1336 or 1337. The fact that IOB is indeed more recent than IOA, which had been established by the sequence of hoards referred to above, can now be demonstrated by the weight profiles (see below). To date, the rather small quantity of properly studied specimens had precluded any such metrological observations.

-

• The Nivicë Bubar hoard is actually dominated by groups IOA and IOB (85 and 47 specimens), and not IOΓ (13) as one might have imagined in view of the single-type hoards from Roussaiïka and Naupaktos being mostly composed of IOΓ.

-

• Group IOA is dominated by the variety without reverse signs (Issue 13), with 46 specimens. This also comes as a surprise, since its existence had previously been considered only on the margins by Lambros and Baker (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 770, of the Ermitsa hoard, is in fact a specimen of Issue 13, but had been given a group IOA var? identification by Baker). This comparison of Ermitsa 1985A and Nivicë Bubar shows that Issue 13 must have been minted towards the end of the production period of IOA. As a continuation of the previously described varieties in Baker Reference Baker2020 (var1–var4), Issue 13 has now been given the name IOA var7. The link between no. 53 of Issue 13 (IOA var7) and no. 16 of Issue 7 (IOA var1) remains problematic, not helped by the fact that the actual identity of the latter coin is not 100% secure.

-

• Following on from the previous consideration, this group IOA var1, characterised by the I and the O next to the reverse castle, which is prominent in the collection of Lambros and in the hoard from Ermitsa, features at Nivicë Bubar merely as the one dubious coin that has just been mentioned (no. 16 of Issue 7). Also, the paucity of this variety could not have been expected. As the Romanos hoard reveals, IOA var1 is in fact with great likelihood the very first variety of John of Kephallenia’s coinage, which may well explain its petering out by the time our hoard was finally abandoned.

-

• Issues 8–10 = nos 17–44, var2–4 of IOA, are well known from the existing bibliography, and the relative distributions, in the light of the Ermitsa hoard, are also as expected at 24, 2 and 2 specimens.

-

• In turn, Issues 11 and 12 are revelations. The variety with the lily on the reverse (nos 45–46) is rare;Footnote 10 the variety with the star (nos 47–52) had previously and erroneously been considered part of group IOΓ. In this sense, the single coin from the Arta mint found in the Athens Roman Agora (Lytsika) 1891A hoard needs to be reclassified IOA from IOΓ. These varieties have been inserted into the previously established reference system: Issue 11 will be IOA var5, Issue 12 IOA var6.

-

• The most important typological revelation of Nivicë Bubar is Issue 15 (nos 53–100). This issue belongs to group IOB as described by Baker (Reference Baker2020) according to style of lettering, although the orthography and quality of execution lead it halfway to group IOΓ. Indeed, this latter group had been subdivided by Baker (Reference Baker2020) into var1 and var2 according to orthography and reverse signs. The evidence of the 49 specimens of Issue 15 at Nivicë Bubar lead one to believe that the majority of the coins considered in this previous scheme as IOΓ var1 would require reclassification into this IOB bis, or IOΓ var2. Indeed, the very existence of IOΓ var1 appears to be in doubt. The 49 coins of Issue 15 take the name IOB bis.

-

• Issues 16, 17 and 18 (nos 148–160) are in sync with our expectations. The only unexpected element within this range is the concentration (with five examples) of the coins of group IOΓ var2 bearing the lunette (Issue 17). This feature can be found underneath the castle instead of at the side, as described in the past.

-

• Finding counterfeit deniers tournois in a medieval hoard is not at all surprising (Issue 19).Footnote 11 Every single one of nos 161–166 is completely in line with what is known about such issues. Nonetheless, the special characteristics that need to be underlined here are the following. First, even though Nivicë Bubar is essentially an ‘Artan’ hoard, with the almost total exclusion of the important issues of Achaia, Athens, and Naupaktos, it still contains a certain quantity of coins not struck at the official Arta mint; indeed, 5% being counterfeits is quite high for any hoard. Second, even if these coins did not involve the official authorities in charge of the Arta mint, these supposedly private coin producers nonetheless chose the Artan issues as their prototypes. This is quite astonishing given the fact that these other much better and much more common denier tournois issues were avaiable locally. Nonetheless, counterfeiters chose Artan prototype for copying. This is noteworthy.

According to the model put forward by Baker (Reference Baker2020), a logical initial date for group IOΓ is either 1331 or 1333. Since Nivicë Bubar is dominated by the earlier IOA and IOB (Issues 7–15), at 132 coins, one might put forward the final concealment in the timeframe 1331–4. The coins of Robert of Taranto of type RAA1 contained in the hoard (nos 13–15, Issue 6) – all in fact struck from different obverse and reverse dies – would not support an early 1330s dating (Baker Reference Baker2020, 1424–5). We must look more towards the middle of the decade for the concealment of the hoard, purely from a numismatic point of view.

According to the established narrative, John II of Kephallenia began striking deniers tournois (group IOA) at Arta of median quality and quantity in 1323 or soon thereafter, and certainly before he was declared despot by the imperial authorities (1328 or a bit later). These coins then mixed themselves into the circulation stock of deniers tournois of Achaia, Athens, Naupaktos, and elsewhere, at different percentages in line with geographical criteria. The hoard from Ermitsa is a good example from the area of the Ambracian Gulf. This hoard was presumably concealed in about 1330 or 1331, with 24 Artan tournois of groups IOA and IOB, on a total of 360 deniers tournois. After this phase, with the transition to IOΓ, we find two related phenomena: first, there are denier tournois hoards from within the territory of the ‘despotate’ which contained only issues of Arta, and second, there is migration of these same issues towards the north and the north-east. The low quality of IOΓ and maybe their superior quantity are part of these same considerations. Within this panorama, the Nivicë Bubar hoard offers us something entirely new: a hoard totally dominated by Artan tournois, but of groups IOA and IOB, in a part of the ‘despotate’ in which the use of deniers tournois was long established (see below), and at a time when group IOΓ was in fact already in production.

The particularity of the Nivicë Bubar hoard finds confirmation in the stray finds from the same church (3). Numbers 167–171, the only ones found inside the church, but in completely different contexts to the hoard, all belong to issues already found in the hoard (Issues 8, 13, 15). Also, these suggest therefore a ‘closed’ circulation pattern. The historical context gives the key to this (see below).

Returning to the aforementioned die study, which is perhaps less useful for the time being to appreciate the microstructures of Artan coin production (see above), it nonetheless gives us valuable insights into its overall phasing and quantification, and above all the formation process of the hoard. Temporarily leaving aside group IOΓ, groups IOA and IOB represent a maximum of 10 years of minting at Arta (1323–33; less so if we set the beginning after 1323 and/or the transition to IOΓ in 1331). There are 132 coins of groups IOA and IOB, struck from 128 obverse and 124 reverse dies. In addition to maybe proving that the reverse (the side featuring the castle) was technically speaking the obverse, this count reveals an absolutely enormous coinage. For the maximum duraction of 10 years we observe an average of 12 reverse dies (the technical obverse) per annum, which already in itself represents a large issue. Yet it is important to underline that these are merely the dies actually seen. Ideally one would apply a formula which calculates the original number of dies from the data produced from a sample, like that of Esty (Reference Esty2006). As it stands, the number of dies is too close to the sample size to do this in a meaningful manner. That is to say, the sample would have to be increased in order to achieve more die duplication and a larger gap between total number of coins analysed and dies identified. Currently we can only say that the average original dies used per annum would have been much larger than the observed 12, but whether this was perhaps 200% or 1000% (24 or 120 dies), or indeed any other extrapolated number, is impossible to say. The interesting point to make in this context about the Nivicë Bubar hoard is that, apart from being somehow isolated from broader circulation patterns of deniers tournois of other mints, it was nonetheless composed not of one single consignment from the Arta mint, as can occur with single-type hoards, but in fact of multiple ones over about 10 years, in each case with the most recent issue of that mint. The hoard is therefore unusual in a double sense, in the constant replenishment from a mint more than 100 km away, and in the protection, in this long chronological stretch, from products from other mints.

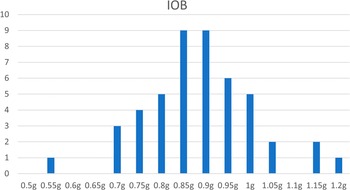

For groups IOA and IOB, the Nivicë Bubar hoard allows one to investigate for the first time the metrology of the Artan issue. We are not primarily interested in the absolute weight standards – since too many factors might have impacted on this, such as usage or conservation in situ. The modal and average weights, and the overall weight distributions, as represented in Figs 12 and 13, are quite revealing. A relatively regular pyramid in each case – especially in consideration of the relatively small total number and the otherwise sloppy aspect of the coins – is noteworthy, which gives us the confidence that extrapolations can be made from weight profiles: therefore IOA and IOB reveal themselves once more as distinct issues, with the slightly higher weights for IOB probably due either to a change of standard or its more recent mintage, or a combination of both. The somewhat irregular aspect of the curve for IOA might reveal different standards within the overall group, though the information is currently not detailed enough to explore this point further.

Fig. 12. Distributions of weights in grams for IOA issues in the Nivicë Bubar hoard.

Fig. 13. Distributions of weights in grams for IOB issues in the Nivicë Bubar hoard.

Concluding the numismatic discussion, with the hoards of Nivicë Bubar (2) and Shën Jan (1), a small part of the medieval Vagenetia saw concealments and abandonments of coin hoards in churches dating – numismatically speaking – about 10 years from each other, between the mid-1330s and the mid-1340s. The most striking additional factor is the ‘closed’ character of the first of these; and conversely the suggestion through the second of these hoards that the area was monetarily ‘open’ to the world.

ARCHAEO-HISTORICAL CONTEXTS

Our attention is focused on the peraia of the great island of Kerkyra. In medieval times, the ancient regions of Thesprotia and Chaonia took the name Vagenetia (Βαγενετία o Βαγενιτία: Soustal Reference Soustal1981, s.v. Bagenetia; Asdracha and Asdrachas Reference Asdracha, Asdrachas and Chrysos1992; this area corresponds in part also to the Albanian Çamëria), a province or thema which occupied a coastal strip along the entire length of the island, from Chimara (Albanian: Himarë) in the north to Parga in the south (Fig. 2). In an easterly direction, beyond the mountains, were other themata, those of Dryinoupolis and of Ioannina. To the north, meanwhile, could be found the important town of Aulon, capital of a katepanikion, and next to it the castle and episcopal see of Kanina (Albanian: Kaninë).

To understand the presence of the different monetary types and the formation of the hoards, and their concealments and abandonments, it will be necessary to consider in the first instance the political and strategic, and then the demographic and commercial, situations in what is now the westerly part of the modern Delvinë Municipality. Our vision relies on often quite circumstantial considerations around the scarse written and archaeological documentation.

At the end of the thirteenth century, control over Kerkyra and the Vagenetia was divided amongst the dynasties of Anjou of southern Italy and the Komnenoi Doukai of Epiros, linked after 1296 with the marriage of Philip I of Taranto and Ithamar of Epiros. Nonetheless, the Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II, issuer of a chrysobull for the see of Kanina in 1307 (Alexander Reference Alexander1940–1), and subsequently the rulers of Kephallenia, Zakynthos, etc., became ever more important protagonists in the region. In the run up to the assassination of Despot Thomas, brother of Ithamar, which was ordered by Nicholas of Kephallenia (1318), the area of Aulon/Kanina and the whole of the Vagenetia were quite unstable. In addition to imperial Byzantine and despotal areas of control, there were feudal and decentralising elements. The death of the despot simplified the power dynamics again, and the Vagenetia evidently became part of the territory of Nicholas, while Ioannina and Aulon/Kanina which surround it were (again) under imperial control (Nicol Reference Nicol1984, 69–89; Ducellier Reference Ducellier and Moschonas2003, 34). To the west, the island of Kerkyra was Angevin. The Vagenetia was therefore the northernmost part of the territory controlled by Nicholas, a thin and vulnerable strip. This is the context in which, for example, he offered the exploitation of the fisheries of the lake of Bouthrotos to Venice, obviously with the hope of military support (Soustal Reference Soustal1981, s.v. Buthrōtos; Nicol Reference Nicol1984, 90; Asonitis Reference Asonitis1999, 90). This attempt came to nothing, no doubt as a result of the geo-strategic difficulties which have just been described.

In the first months of 1323 John II of Kephallenia ordered the assassination of his brother Nicholas and took control of the area he had dominion over (Kiesewetter Reference Kiesewetter2001, 72). One of the first important developments of his rule was its extension over the town of Ioannina, first as kephalē on behalf of Emperor Andronikos II, and after the collapse of their relations as independent potentate (Asdracha Reference Asdracha1977, 169). The evident aggression and sense of purpose of Nicholas (1318–23), and especially of John II (from 1323), in the context of which one may also cite the latter’s immediate decision to coin money in his name at Arta (see above), provoked a reaction from the house of Anjou, which saw itself obliged to redefine its position vis-à-vis Kerkyra and its terraferma, and indeed its different interests in the entire Greco-Albanian area (Kiesewetter Reference Kiesewetter2001, 70–5). In this context, the new despot of Romania (since 1319), Philip II, son of Philip I of Taranto (the latter becoming nominal Latin emperor of Constantinople on the same occasion) and of Ithamar, sister of the deceased Thomas, can be found personally present on the island in 1321. The brother of Philip I, John of Gravina, became prince of Achaia in the same year, that is to say he became overlord of Nicholas and then of John II for Kephallenia. In 1324, Philip II was again on Kerkyra (Asonitis Reference Asonitis1999, 90), and in 1325 John of Gravina launched simultaneous military campaigns against the central dominions of the dynasty of Kephallenia (specifically: Leukas, Arta, Vonitsa), and against the Byzantines in the Peloponnese and in Albania, around Aulon and Bellegrada (Berat/Berati). From 1328 to 1330 Philip II can be seen preparing a significant military build-up in Kerkyra and an imminent intervention on the adjacent mainland, which came to nothing due to his death in May 1330. Walter II of Brienne, nominal duke of Athens with personal and feudal links to Philip I of Taranto both in Puglia and in Epiros/Greece (he had married the sister of Philip II in 1325), equipped with a crusader bull by Pope John XXII, departed from Brindisi in August 1331 and rapidly took control of Leukas (Soustal Reference Soustal1981, s.v. Arta, Leukas) (Philip I of Taranto himself died shortly thereafter, in December 1331). Nearby Vonitsa had remained under Angevin control since 1325, Bouthrotos became Angevin either through the actions of Captain William of Tocco (1330) or those of the Brienne a year later (Luttrell Reference Luttrell1977; Soustal Reference Soustal, Hodges, Bowden and Lako2004, 24). It is important to note that our two churches are merely 20 km from Bouthrotos.

It is evident from this account that pressure on John II of Kephallenia mounted in the course of the 1320s, and especially the early 1330s, so much so that one might surmise that already by 1330/1, this most northerly part of his dominion, i.e. the Vagenetia, must have looked unviable. Donald Nicol has remarked: ‘Even an opportunist adventurer like Despot John Orsini saw little scope in the confusion to the north of his dominion’ (Nicol Reference Nicol1984, 101). With respect to the political demarcations during this period, one may cite Alain Ducellier: ‘Deliminating, in this area, the borders of the influence of the Byzantines, the Angevins, and the despot of Epiros, is impossible’ (Ducellier Reference Ducellier1981, 351). With the death of another semi-independent local ruler, the sebastokrator Stephen Gabrielopoulos, in the autumn of 1333 and the resulting absence of a lord in the northern part of Thessaly, John took his interests eastwards (Kantakouzenos, book 2.28; Nicol Reference Nicol1984, 102).Footnote 12

The new Emperor Andronikos III, who at the beginning of his sole rule in 1328 had still viewed John with benevolence, saw these recent developments, the death of Gabrielopoulos, John’s expansionism, and the anarchy which took over in parts of ‘Albania’, with worry. For this reason, in line with the account of Kantakouzenos, he came personally to Thessaly in 1334 and received delegations of Albanians, before retreating to Thessalonike (Bosch Reference Bosch1965, 135).

In line with Asdracha’s chronology, Andronikos III began his next westerly campaign in the summer and autumn of 1337 (and not 1338, which is an erroneous conclusion based on the account of Gregoras) (Asdracha Reference Asdracha1977, 166; see also Osswald Reference Osswald2006, 342). At least two events led to this operation: the Albanian revolt in 1336, and the death of John II of Kephallenia, which would have occurred in line with this chronology towards the end of 1336 or the beginning of 1337 (Kantakouzenos, book 2.32; Frasheri Reference Frasheri1962, 162–3; Bozhori and Liço Reference Bozhori and Liço1975, 215–16, 223–6; Nicol Reference Nicol1984, 105). The Albanian insurrection was in itself the result of excessive Constantinopolitan pressure (Ducellier Reference Ducellier1981, 349), and according to Kantakouzenos there was already unrest before 1336. In his narration of the events of 1336–8, Kantakouzenos does not specify the Vagenetia explicitly. Nonetheless, important conclusions can be drawn from his History, especially the extreme violence on both sides, Albanian and Byzantino-Turkish (Kantakouzenos, book 2.32). Gregoras also highlights this violence (Gregoras, book XI.1).Footnote 13 When the troops of Andronikos and his Turkish mercenaries took from the Albanians, 300,000 cattle, 5000 horses, and 1,200,000 sheep (Kantakouzenos, book 2.32; Zachariadou Reference Zachariadou and Chrysos1992, 90), it is easy to believe that these events took place in the Vagenetia, even if the Byzantine author does not go into geographical details in this context.

In these southerly Albanian territories in medieval times, transhumance was commonly practiced. The animals wintered (the traditional dates being 26 October–23 April according to the Julian calendar) in the coastal areas of Aulon and the Vagenetia (there were no larger coastal plains between the two), and were taken to the mountainous interior in the summer. In order to have taken such great numbers of animals in one sweep (even if the figures themselves are to be taken with a pinch of salt), the incomers would have had to find them concentrated on the coast, and the immediate flat and fertile area of our two churches is a prime candidate for such events.

The monastery of Mesopotamon, only 5.5 km from Shën Jan (see above), was certainly Byzantine in the year 1337 (Soustal Reference Soustal1981, s.v. Mesopotamon; Xhyheri and Bushi Reference Xhyheri and Bushi2011, 229). At one point between 1330 and 1336/7, the dominion of the ruling dynasty of Kephallenia over our part of the Vagenetia would have disappeared completely. As a consequence, somewhere between the lake of Bouthrotos and the akropolis of Phoinike an Angevin–Byzantine frontier might have established itself, or indeed more likely a political and administrative void would have been present there for some years, filled perhaps, according to the few pieces of information we have by locals, with ‘unruly’ or ‘anarchic’ tendencies. As a consequence, one may suppose that it was actually in 1337 that Byzantine rule established itself there through a rather violent take-over.

From book 2.34 of Kantakouzenos one learns that all of the Vagenetia, from Chimara to Parga, pronounced loyalty to Andronikos III in the years 1337/8. After years of warfare and confusion, the area enjoyed stable rule. However, this was merely for about a decade, or possibly even less.

The date of the Serbian conquest of the Vagenetia is uncertain. The central Albanian coast, between the rivers Mat and Shkumbin, had already been taken by King Stephan Dušan in the year 1336 (Xhufi Reference Xhufi2006, 257.) A historical note in the codex of the monastery of Shën Jan Vladimir (Elbasan) of 1 March 1339 demonstrates that on this occasion the king took renewed control of this central Albanian area. Four years later, in 1343, the king of Serbia confirmed the ancient privileges of the inhabitants of Kruja. In these years, Stephan took the area under Serbian occupation south of the Shkumbin river, induced by the beginnings of the Byzantine conflict between John VI Kantakouzenos and John V Palaiologos. It is known that Ioannina was Serbian from 1342 (Soustal Reference Soustal1981, s.v. Ioannina). In 1342 or 1343, the southerly part of modern Albania also fell to Dušan, including Aulon (and its castle Kanina) and Bellegrada. Excavations conducted in the area show that Serbian attacks did not spare settlements and their Christian cult places, and also saw expulsions of populations as had been witnessed under Andronikos III a few years earlier. The cited hoard from Kafaraj might well have been abandoned on this occasion.

It is likely that the more southerly Vagenetia was also affected by Serbian attacks during 1342–3, even though the permanent Serbian take-over would only have taken place during 1347–8, when most of Epiros and Thessaly fell (Ducellier Reference Ducellier1981, 357–8; Nicol Reference Nicol1984, 128–9; Soulis Reference Soulis1984, 19, 35). In 1348, mainland Greek refugees are attested in Kerkyra (Asonitis Reference Asonitis1999, 92). The dating of a western Bulgarian coin, which has been found as a single piece at Doliani, suggests a thorough Serbian conquest of the Thesprotan countryside only towards the end of the decade (Baker and Metallinou Reference Baker and Metallinou2011).

The medieval Vagenetia, like other coastal parts of the so-called despotate, offered merchants primary materials and a certain ease of access, opening up as it did to the west and the Italian peninsula. In addition to the usual agricultural products, the area was known for animals and animal products. Salt and fish from the lake of Bouthrotos (see above) and minerals are also noted (Asonitis Reference Asonitis and Moschonas2003, 66). Foreign feudatories in the area are testimony to these commercial interests. We see for instance the confirmation of a feud in the southern Vagenetia for the Venetian Jacopo Contarini by Despot Thomas in the year 1303 (Nicol Reference Nicol1984, 72). Nonetheless, the described geo-political challenges rendered such commerce often difficult.Footnote 14 The Vagenetia itself did not enjoy a harbour of international importance – Venetian merchants are more readily attested at Aulon and Arta (Nicol Reference Nicol1984, 76, 91, 99–101). Nonetheless, Kerkrya, which remained Angevin througout our period, and the care taken over commercial relations by the local Venetian ambassador there (Asonitis Reference Asonitis and Moschonas2003, 66) gave the Vagenetia an extremely useful outlet for its products, should the political situation permit it. Precisely this Corfiot commerce gave the local Angevin fisc in the year 1330 10 times more profit in indirect taxation and other dues than did the exploitation of local landed resources (Asonitis Reference Asonitis1999, 161, 169–70).

From the last years of the thirteenth century onwards, all of the ‘despotate’ (including its northerly part between the Vagenetia and the adjacent thema of Ioannina) and the nascent Angevin parts of Epiros and its islands were emancipated from using the increasingly unreliable Byzantine monetary stock, in favour of feudal Greek and Venetian coins. The domination of Achaian and Athenian deniers tournois in particular is attested by different hoards: that of Shën Dimitri, found just south of Bouthrotos with a dating of c. 1320 (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 115), has the same typical composition of southern Greek hoards,Footnote 15 as does the Ioannina 1986 hoard of very similar date (Baker Reference Baker2020, no. 119), or even the cited one from Romanos Dodonis 1963, which contains additionally the first hoarded specimen from the Arta mint. In the 1290s the Angevin authorities in Kerkyra also produced deniers tournois, which provides another element in our understanding of the diffusion of this currency in our area (Baker Reference Baker2020, 1441–3). Finally, as the town of Ioannina became Byzantine again in 1318, the imperial authorities recognised its right to use local rather than Byzantine money (charagma), which has been interpreted as being the denier tournois currency (Baker Reference Baker2020, 56, 1558).

INTERPRETATION AND CONCLUSION

In medieval times hoarding was a common way of safeguarding coins. At times, and for varying reasons, these were not retrieved by their owners. In the cases of Nivicë Bubar and Shën Jan, two churches were chosen by individuals or collectives as storage places for quite menial quantities of money, no doubt with the intention of being retrieved. There is always a temporal lapse between concealment and final abandonment of a hoard. The formations of Nivicë Bubar and of Shën Jan finished respectively in about 1335 and 1345, from a numismatic point of view. Final abandonment probably took place in Nivicë Bubar in 1337–8 (less likely 1342–3), that of Shën Jan in 1342–3 (less likely) or 1347–8, both evidently in violent contexts, which are attested first hand in the examined archaeological remains. With these dates in mind, we can bring the abandonments of the hoards in line with the documented Byzantine and Serbian attacks. On the other hand, we do not know whether the decisions to hoard in these positions was taken on the same occasions, nor whether the owner(s) were present during the attacks. In general terms a church might have been regarded as a safe place for persons and valuable items alike – from an architectural or spiritual viewpoint. In these particular circumstances, however, the coins were only retrieved by archaeologists in the twenty-first century. With respect to the second of the hoards, that of Shën Jan, it should be pointed out that another circumstance might have hindered its owner from accessing it: the Vagenetia, as the rest of the European continent, would have been hit by the Black Death in these years (1346–8). We know from the relatively nearby regions of Macedonia and the Peloponnese that even rural areas were affected by the plague (Baker Reference Baker2020, s.v. Black Death). Therefore, the likelihood that it caused the non-retrieval of the hoard should not be discounted.

We do not know who the last medieval owners of our hoards were, nor the final steps which they took before abandonment. Suffice it to say that these would in all likelihood have been local regular users of coinage, maybe even the churches and their personnel themselves, since these too would have been monetised and have had a balance of payments of sorts, however small. Nonetheless, the coins in the hoards of Nivicë Bubar and of Shën Jan are distinctive enough to allow us to draw important conclusions, in a wider and more structural sense. Under John II of Kephallenia, from 1323 or shortly thereafter, a mint in Arta issued deniers tournois from a rather significant number of dies, many more than might have been imagined in the past. For a period of about 10 years, coins made from these dies were sent purposefully to our area. Nivicë Bubar is only a sample of the local currency, so we do not know whether products of all Artan dies made it to the area. Nonetheless, the selection as it stands is already remarkable for its die variety. The only way in which one can image a constant and rather lengthy transfer of coins from Arta c. 115 km northwards is by official route, that is to say as part of the administration of the Vagenetia by John. In exactly the same time, at Clarentza in the Peloponnese, under Princes John of Gravina and then Robert of Taranto, a parallel denier tournois issue was created in much larger quantities, a coinage which until 1320 or a bit later was used liberally in the same area. In the light of the Nivicë Bubar hoard (note that even the counterfeiters chose Artan models), we must surmise that this regular circulation stopped for about a decade, caused by Angevin and Byzantine pressures, or even a lack of stability induced by the local population, and that coin usage relied on these rather artificial injections of specie via official channels. From the Nivicë Bubar hoard we can also deduce that even the issues of the dynasty of Kephallenia minted at Arta ceased to arrive quite as regularly after a certain point, that is to say the early years of the 1330s, no doubt because of heightened geo-strategic challenges and then the redirection of the military interests of the despot towards Thessaly.

If the regular circulation of monetary specie was heavily compromised in our area during the entire reign of John II of Kephallenia and especially in the years leading to the Byzantine conquests of 1337/8, the subsequent period down to about 1347 or 1348 might have been quite different, if one takes the Shën Jan hoard as evidence. The most obvious interpretation would have to be that the short-lived Byzantino-Angevin power-share allowed more regular access to the area, by which way the new soldino denomination was quickly introduced into circulation at a local level. This might have had an international (Venetian) trading component. These broader tendencies shaping entirely new monetary conditions for the area, and for which the cited hoard from Gusmar is important corroborative evidence, do of course not allow us to comment on the identity of the last owner(s) of the hoard of Shën Jan, who in all likelihood would not have had a direct international commercial interest nor be foreign to the area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are thankful to the editors of the journal for their efforts in guiding this paper through the various stages; to the two anonymous readers for their helpful comments; to Anna Blomley for the creation of Figs 1–2; to Elio Hobdari for Figs 3–5; to the Instituti i Arkeologjisë, Tirana, Albania, for facilitating the study of the materials; and finally to the Craven Committee (Oxford), to Graeme Smith (Cornwall), and the Royal Numismatic Society (London), for financial support.