Introduction

Recent research suggests that synchronous computer-mediated communication (SCMC) can strongly mediate L2 engagement in spoken tasks (Smith & Zeigler, Reference Smith, Zeigler, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023). Among the various SCMC modes, video-based SCMC (SvCMC), which utilizes online video conferencing software, has increasingly been adopted in language classrooms but remains the least understood (Kohnke & Moorhouse, Reference Kohnke and Moorhouse2022). While some studies investigating L2 task performance suggest that SvCMC can facilitate cognitive engagement more than face-to-face (FTF) interaction (Qiu, Reference Qiu2024; Qiu & Bui, Reference Qiu and Bui2022), others have found the opposite, describing SvCMC spoken collaboration as less engaging, influenced by diminished feelings of ‘social presence’ that dampen positive emotions and reduce affiliative behavior (Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2023; Yamada & Akahori, Reference Yamada and Akahori2009). Furthermore, despite a strong rationale that suggests task engagement drives learning processes (Hiver & Wu, Reference Hiver, Wu, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023), there is little evidence that links engagement to future task outcomes. The current study aims to first investigate the differences in cognitive, social, and emotional engagement as learners collaboratively conceptualize content in SvCMC and FTF modes while planning for an oral monologic task. It then explores differences in L2 semantic content used in follow-up monologic task performances. Finally, it examines whether engagement dimensions in planning predict task performance. Our findings contribute to a better understanding of the benefits of SvCMC and FTF modalities in terms of both engagement and subsequent L2 learning.

Task engagement and L2 learning

Learner engagement is associated with heightened attention, active participation, and meaningful involvement (Fredricks et al., Reference Fredricks, Reschly and Christenson2019). In task-based language teaching (TBLT), investigating engagement is important for understanding how L2 learners take advantage of learning opportunities afforded to them by a task (Hiver & Wu, Reference Hiver, Wu, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023). Research in this domain draws on Philp and Duchesne’s (Reference Philp and Duchesne2016) multidimensional model, which specifies four interrelated dimensions of task engagement. First, behavioral engagement indicates learners’ task participation, measured by words or turns produced or time on task (Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2023; Qiu, Reference Qiu2024). Second, cognitive engagement pertains to the mental effort learners invest in the task, often assessed by the extent to which meaning is negotiated (Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Phung and Reinders2021) or content is elaborated (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Philp and Nakamura2017). Third, social engagement concerns learners’ affiliation (Svalberg, Reference Svalberg2018), demonstrated by learners’ acknowledgements of each other’s contributions or their efforts to provide mutual support (Lambert & Zhang, Reference Lambert and Zhang2019). Finally, emotional engagement reflects affective aspects of interaction, manifesting in positive “task-facilitating” emotions, such as enjoyment, or the absence of negative “task-withdrawing” emotions, such as anxiety (Reeve, Reference Reeve, Christenson, Reschly and Wylie2012, p. 150). Engagement thus enhances learning by fostering motivated, active participation that provides opportunities for negotiation, noticing, and deep processing (Leow, Reference Leow and Leow2019) and by minimizing negative emotional arousal that can hinder cognitive function (Cheie & Visu-Petra, Reference Cheie and Visu-Petra2012; Eysenck & Keane, Reference Eysenck and Keane2020).

Most TBLT research so far has treated task engagement as an outcome of interaction (Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2023; Lambert & Zhang, Reference Lambert and Zhang2019; Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Phung and Reinders2021), providing little empirical evidence that engagement leads to L2 learning (for exceptions, see Dao & Hiver, Reference Dao and Hiver2025; Lambert & Aubrey, Reference Lambert and Aubrey2025). Continued research from a multidimensional perspective is necessary to understand how socially and emotionally enhanced task conditions can improve both engagement and subsequent learning.

Engagement in SvCMC and FTF modes

SvCMC has seen rapid adoption in L2 learning environments since the COVID-19 pandemic, often used as a direct substitute for FTF interaction (Kohnke & Moorhouse, Reference Kohnke and Moorhouse2022). Unlike other SCMC modes (e.g., text-chat), SvCMC allows for the transmission of paralinguistic cues, such as eye contact, smiling, and head nodding, through both verbal (audio) and non-verbal (video) sensory input (Smith & Zeigler, Reference Smith, Zeigler, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023). This can contribute to a sense of “social presence” during communication, characterized by immediacy (feeling physically close), intimacy (feeling understood), and sociability (feeling connected). According to social presence theory (Lowenthal, Reference Lowenthal2009), communication mode is effective when it provides the necessary level of social presence required for the engagement demanded by a task.

Despite its advantages over other SCMC modalities, research has consistently shown that learners using SvCMC encounter difficulties in perceiving non-verbal cues compared to FTF mode, resulting in reduced social/emotional engagement as they struggle to establish social presence (Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2023; Qiu, Reference Qiu2024; Qiu & Bui, Reference Qiu and Bui2022). It should also be noted that existing research is limited to a few classroom-based studies that have produced mixed findings regarding cognitive engagement. For example, Aubrey and Philpott (Reference Aubrey and Philpott2023) found that decision-making SvCMC tasks performed in a computer classroom led to fewer instances of negotiation of meaning and language-related episodes than FTF performances in a regular classroom. However, the authors acknowledged that external factors unique to each mode (e.g., distractions from other students in the FTF classroom and technical/logistical challenges in the computer classroom) likely put additional demands on learners’ attention. Also using decision-making tasks, Qiu and Bui (Reference Qiu and Bui2022) compared SvCMC (conducted at home) and FTF modes (conducted in a classroom). Unlike Aubrey and Philpott, they found that SvCMC elicited more instances of negotiation of meaning than FTF. In a follow-up study, Qiu (Reference Qiu2024) found a trade-off between two measures of cognitive engagement: While learners negotiate meaning in SvCMC more, they tend to produce more content elaborations in FTF. Qiu (Reference Qiu2024) speculated that negotiation was enhanced in SvCMC mode because learners sought to compensate for the lack of non-verbal cues in their collaborations. Given that cognitive engagement might lead to deeper processing, further research—especially in a laboratory setting that controls for extraneous contextual factors—may consolidate insights on the potential learning value of each mode.

Engagement in planning tasks and use of planned L2 content

Strategic planning tasks are carried out, either individually or collaboratively, with the goal of generating and committing to memory the L2 content necessary for use in a follow-up task performance (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Aubrey and Leeming2021). The benefits of planning can be explained by Levelt’s model of speech production (Reference Levelt1989), which posits that a speaker first conceptualizes ideas, then formulates or encodes those ideas with language, and finally articulates by mapping a phonological plan onto the message. Strategic planning is considered useful for “booting up reserves of ideas” prior to a performance (Bygate & Samuda, Reference Bygate, Samuda and Ellis2005, p. 40), and thus primarily supports the conceptualization stage. With reduced cognitive load during task performance, learners who plan task content can focus their attention on producing more fluent and semantically richer task performances (Aubrey et al., Reference Aubrey, Lambert and Leeming2022; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Aubrey and Leeming2021).

Collaborative pre-task planning research aims to understand learners’ planning processes and the extent to which planned L2 content transfers to performances. Several descriptive case studies have revealed that collaborative planners are motivated to maintain cooperative relationships during planning, driving them to pool linguistic resources and scaffold each other to co-construct content (Lee & Burch, Reference Lee and Burch2017; Leeming et al., Reference Leeming, Aubrey and Lambert2022). However, transferring plans to performance can be challenging for learners as it necessitates storing pre-planned information in memory and retrieving it for later use (Aubrey, Reference Aubrey2025; Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2025). Exploring this issue, Truong and Storch (Reference Truong and Neomy2007) analyzed the content planned by learner groups and used in individual presentation tasks. They operationalized L2 content as idea units, or meaningful discourse chunks that provide a measurable indication of conceptualization (Ellis & Barkhuizen, Reference Ellis and Barkhuizen2005). Their findings revealed that learners used between 42% and 88% of planned idea units in their task performances. Similarly, both Aubrey et al. (Reference Aubrey, Lambert and Leeming2022) and Aubrey and Philpott (Reference Aubrey and Philpott2025) found that L2 learners who collaboratively generated ideas to solve a problem transferred on average only about half of their ideas to a monologic task performance. They speculated that learners with higher proficiency were better equipped to use planned ideas as they could encode them more efficiently with the L2 during the task. However, learners might also forgo planned ideas in favor of spontaneous conceptualization during a task (Bui & Teng, Reference Bui and Teng2018), suggesting that their emotional attachment to ideas could influence the transfer process.

Despite indications that social, cognitive, and emotional aspects of planning are important, no research has explored engagement in planning from a multidimensional perspective. Such research is important as it could elucidate how L2 content pre-conceptualized in SvCMC and FTF modes supports speech production in follow-up task performances. Furthermore, it may shed light on whether engagement in planning predicts the use of L2 content in tasks, thereby linking engagement and learning without the need for decontextualized tests of recall (Lambert & Aubrey, Reference Lambert and Aubrey2025).

The current study

This study adopted a between-groups experimental design in which participants formed pairs to complete collaborative pre-task planning in either FTF (n = 64) or SvCMC (n = 64) planning mode in preparation for a monologic problem-solving task performance. We adopted Philp and Duchesne’s (Reference Philp and Duchesne2016) multidimensional framework of task engagement to address the following research questions:

-

1. To what extent does communication mode (FTF, SvCMC) affect learner engagement in pre-task planning for oral problem-solving tasks?

-

2. To what extent does communication mode (FTF, SvCMC) in pre-task planning affect the L2 content used in subsequent oral problem-solving task performance?

-

3. To what extent do L2 proficiency and learner engagement in pre-task planning predict the L2 content used in subsequent oral problem-solving task performance?

For Research Questions 1 and 2, the independent variable was communication mode with two levels (FTF, SvCMC), and the dependent variables were the five measures of cognitive, social, and emotional engagement in pre-task planning and the two measures of L2 content used in task performance (i.e., planned and unplanned idea units used). For the predictive relationship that is the focus of Research Question 3, the independent variables (i.e., predictors) were the measures of engagement in pre-task planning and L2 proficiency, while the dependent variables (i.e., outcomes) were the measures of L2 content used in task performance.

Method

Participants

One hundred twenty-eight undergraduate students from a university in Hong Kong (age: M = 18.82; SD = 1.24) who spoke Cantonese as their first language and English as their L2 voluntarily participated in this study. They were either first-year (n = 99) or second-year (n = 29) students majoring in subjects other than English. Participants scored either “3” or “4” in the English language subject of the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary School Exam, placing them at an intermediate proficiency level (benchmarked to IELTS 6.02 to 6.36, approximately B2 CEFR level). In anticipation of the collaborative planning, recruited participants were asked to partner with a friend who also met the selection criteria. This minimized confounding interlocutor familiarity effects, which have been shown to affect task performance (Leeming et al., Reference Leeming, Aubrey and Lambert2022). An a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1.9 (Faul et al. Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) determined that a sample size of 128 was sufficient to perform the intended statistical analyses with a medium effect size.

Materials

Task

The task used in this study was a monologic problem-solving task. Specifically, participants were told they were hired as consultants for the university to propose a replacement for an unpopular university mascot. During their 3-minute speech, they needed to (1) suggest three possible mascots and describe how they represent the school, (2) recommend one, and (3) give reasons for their choice. To prepare for the monologue, participants engaged in 10 minutes of pre-task planning in pairs, where they collaboratively discussed solutions to the problem while referring to a worksheet with prompts/questions to guide them (see Supplementary Material).

Idiodynamic rating software

To measure emotional engagement, participants rated their per-second anxiety and enjoyment levels while watching a video recording of their planning using idiodynamic software (Ducker, Reference Ducker2024). Whereas past task-based studies have typically used post-task questionnaires (Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2023; Nakamura et al., Reference Nakamura, Phung and Reinders2021) or interviews (Qiu, Reference Qiu2024; Qiu & Bui, Reference Qiu and Bui2022) to gauge learners’ emotions, the idiodynamic method was adopted because the video stimulus helps mitigate memory bias, offering a more reliable measure of learners’ task experience (MacIntyre, Reference MacIntyre, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023).

C-test

A C-test (adapted from Babaii & Ansary, Reference Babaii and Ansary2001) was administered to all participants as a measure of integrated English language proficiency. The C-test consisted of four passages and 69 blanks. Participants were given 20 minutes to complete the test. Cronbach’s alphas for the 69-item C-test were .840 (FTF) and .824 (SvCMC), suggesting good reliability.

Procedures

Data collection sessions took place separately for each of the 64 pairs in a laboratory setting. Pairs were randomly assigned to complete planning in either FTF or SvCMC mode.

To begin, the researcher explained the purpose of the task, informing participants that they would complete 10 minutes of planning in English. In the FTF condition, learners in each pair sat across from each other at a table. To facilitate collaboration, they were provided with one worksheet and one pencil, which were collected after the planning session. In the SvCMC condition, the same procedures were followed, but learners utilized the online conferencing software, Zoom, with each participant working from different computers in adjacent rooms. Zoom was chosen as it is the university’s standard SvCMC software, and all participants were familiar with it. The audio was set to 80%, and a live video feed was positioned at the top center of the screen so that partners could see each other. The planning worksheet was converted into a Google Document, and screen-sharing was enabled to ensure that written notes were visible to both participants. Immediately after planning, each participant, regardless of planning mode, was taken to separate rooms to perform the 3-minute monologue task. Task performances were audio-recorded and planning interactions were video- and audio-recorded.

Immediately after the task, participants completed their idiodynamic ratings. Following established guidelines (MacIntyre, Reference MacIntyre, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023), they viewed the video of their 10-minute planning discussion while completing per-second emotion ratings by pressing the up and down keys, which recorded their level of emotion from 0 to 10 (see Figure 1). This procedure was repeated with the second emotion (anxiety or enjoyment), the order of which was counterbalanced across participants to avoid practice effects. To ensure data quality, the participants discussed the meaning of enjoyment and anxiety with the researcher before practicing using the software with an example video (for the full training protocol, see Aubrey, Reference Aubrey2025).

Figure 1. Screenshot showing the idiodynamic software interface used for emotion ratings.

Finally, participants completed the proficiency test (i.e., the computerized C-test) within the maximum allotted time of 20 minutes.

Data coding and analysis

Data consisted of 64 planning recordings, 128 monologic task performances, and 128 enjoyment and anxiety self-ratings. In preparation for coding and analysis, recordings were transcribed and pruned versions of the transcripts were created, which excluded filled pauses, false starts, hesitations, and reformulations (Ellis & Barkhuizen, Reference Ellis and Barkhuizen2005).

Engagement in pre-task planning

Although Philp and Duchesne (Reference Philp and Duchesne2016) specify behavioral, cognitive, social, and emotional aspects, we did not include separate measures of behavioral engagement in our analysis for two reasons. First, some previous studies have excluded this measure (e.g., Dao et al., Reference Dao, Nguyen, Duong and Tran-Thanh2021) because words and turns can be seen as already reflected in measures of social and cognitive dimensions (Oga–Baldwin & Nakata, Reference Oga-Baldwin and Nakata2017). Second, there was no variation in planning time as all pairs were told to stop after 10 minutes. In total, we measured five indicators of cognitive, social, and emotional engagement, as described below.

Pre-task planning transcripts were coded for engagement indicators, using coding procedures adapted from prior research (for a summary of common measures, see Lambert & Aubrey, Reference Lambert, Aubrey, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023). First, cognitive engagement was measured by instances of negotiation of meaning and semantically engaged talk. Negotiation of meaning is defined as “conversational exchanges that arise when interlocutors seek to prevent a communicative impasse occurring or to remedy an actual impasse that has arisen” (Ellis & Barkhuizen, Reference Ellis and Barkhuizen2005, pp. 166–167). Indicators in this study included confirmation checks, comprehension checks, and clarification requests. Whereas negotiation of meaning captures learners’ effort to resolve communication problems through interaction, semantically engaged talk is concerned with an individual learner’s cognitive processing around the pre-task content (Dao et al., Reference Dao, Nguyen, Duong and Tran-Thanh2021; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Philp and Nakamura2017). In other words, semantically engaged talk taps into the quality of the pre-task discussion and contribution to planning for the task. Following Dao et al. (Reference Dao, Nguyen, Duong and Tran-Thanh2021), semantically engaged talk was operationalized as instances when learners generated new ideas, provided reasons to support or oppose the inclusion of ideas, and expanded on/added to ideas related to planning. Second, social engagement was operationalized as affiliative responses (Lambert & Zhang, Reference Lambert and Zhang2019), which included laughter, expressions of sympathy and surprise, and enthusiastic agreements. Examples of cognitive and social engagement indicators are shown in Examples 1–9 of Supplementary Material. Third, emotional engagement in planning was measured by per-second enjoyment and anxiety ratings, which were averaged for the 10-minute planning period.

To check coding reliability of cognitive and social engagement indicators, 25% of planning transcripts were coded by the first author. The second author then used a coding scheme developed by first author to code the same 25% of transcripts independently. Percentage agreements were 86.8% (negotiation of meaning), 92.3% (semantically engaged talk), and 88.0 % (affiliative responses). Disagreements were resolved through discussion. The second author then coded the remaining transcripts. Recognizing that mode can impact participants’ contributions to a task (Dao et al., Reference Dao, Nguyen, Duong and Tran-Thanh2021; Qiu & Bui, Reference Qiu and Bui2022), we controlled for language production by computing the ratio of negotiations, semantically engaged talk, and affiliative responses per 100 words as determined from the pruned discourse.

L2 content in task performances

Task performance transcripts were coded for L2 content used, guided by previous coding procedures (Aubrey, Reference Aubrey2025; Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2025; Truong & Storch, Reference Truong and Neomy2007).

The first step involved identifying and removing all task-irrelevant content from the transcripts, such as greetings (e.g., “good afternoon”) or other talk aimed at the researcher (e.g., “Okay, I think I’m finished”). Following this, discourse was segmented into distinct idea units, which Ellis and Barkhuizen (Reference Ellis and Barkhuizen2005) define as a topic and comment with a focus on semantic content. In the data, idea units emerged as self-contained chunks of speech that could be understood on their own, such as proposals for new mascots (e.g., “Firstly I decided a mascot that is called Bobo”), descriptions of mascots (e.g., “Its look is a book”), final recommendations (e.g., “I highly recommend Fifi as the mascot”), and reasons (e.g., “because there are many cats that can find in school”). At this stage, further exclusions were made for incomprehensible/unfinished ideas (e.g., “It’s good for…”) and repeated ideas (e.g., “the gown is yellow and purple colour”/“clothes was yellow and purple”).

Idea units were then cross-checked with planning transcripts and scored on a 3-point scale to reflect any semantic features that differed from planning (for similar partial scoring of idea units, see Aubrey, Reference Aubrey2025; Shin et al., Reference Shin, Lidster, Sabraw and Yeager2016). Idea units scored “1” indicate that all semantic elements in the task performance could be identified in planning. Idea units that were scored as “0.5” could be traced back to the planning discourse, but important semantic elements were missing or changed. Finally, idea units scored “0” would indicate that no semantic elements could be found in planning, suggesting that the idea used is unplanned. Examples of identification and scoring of idea units are demonstrated in Examples 10–13 of Supplementary Material.

To ensure coding reliability, 25% of the performance transcripts were independently coded by the first and second author, resulting in 91.5% agreement (total idea units identified) and 91.0% (scored idea units). For each task performance, two measures were obtained: planned L2 content used was calculated by summing the scores of idea units, while unplanned L2 content was calculated by subtracting this sum from the total number of idea units.

Statistical analysis

Data were first screened for outliers. This resulted in the exclusion of data from four FTF participants and one SvCMC participant, each having Z scores on at least one variable above +3.0 or below −3.0. To check for normality, Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were conducted and histograms were inspected. Although the planning discourse measures (negotiation of meaning, semantically engaged talk, and affiliative responses) were negatively skewed, these distributions could be corrected through log10 transformations. All other measures were normally distributed.

The C-test scores from participants in each planning mode were compared. An independent samples t-test showed no significant difference between the two groups, t = .848; p = .684; d = .153. Given this result, we examined the effect of mode on engagement (RQ1) using a one-way MANOVA, rather than opting to control for L2 proficiency using a MANCOVA. A one-way MANOVA was also conducted on the two L2 content measures to determine the effects of planning mode on task performance (RQ2). For each MANOVA, the assumption of homoscedasticity was met as demonstrated by non-significant results for Box’s Test of Equality of Covariance Matrices (engagement: F =1.245; p =.229; task performance: F = 2.374; p = .068) and Levene’s Test of Equality of Error Variances (p > .05 for all dependent variables). MANOVAs were followed by univariate tests with Bonferroni correction to identify significant effects. To investigate the relationship between engagement in planning and content of task performance (RQ3), Pearson correlations were first performed between the engagement measures (predictors) and task performance measures (outcome variables) to ensure linear relationships between predictors and outcome variables. The “enter” method was used for inputting the predictors into the multiple regression model. SPSS (version 29) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

To address the first research question, descriptive and inferential statistics for engagement measures were calculated (Table 1). MANOVA (Wilks’ Lambda) results yielded a significant main effect in favor of FTF, F(5,117) = 3.270; p = .008; η p2 = .123. Follow-up univariate tests showed that in comparison with SvCMC mode, FTF mode generated significantly more semantically engaged talk (p = .025; η p2 = .040) and affiliative responses (p = .002; η p2 = .078), with small and medium effect sizes respectively; in contrast, SvCMC led to significantly higher anxiety (p = .029; η p2 = .038), with a small effect size. No significant differences were found for enjoyment (p = .57, η p2 = .003) or negotiation of meaning (p = .058, η p2 = .029), though the latter showed a small effect in the direction of FTF mode. These results suggest an advantage of FTF mode over SvCMC in promoting aspects of cognitive (i.e., increased semantically engaged talk), social (i.e., increased affiliative responses), and emotional engagement (i.e., reduced anxiety) in pre-task planning.

Table 1. Follow-up univariate results: pre-task planning.

Note: *p < .05. **p < .01; AR = affiliative response; NoM = negotiation of meaning; SET = semantically engaged talk.

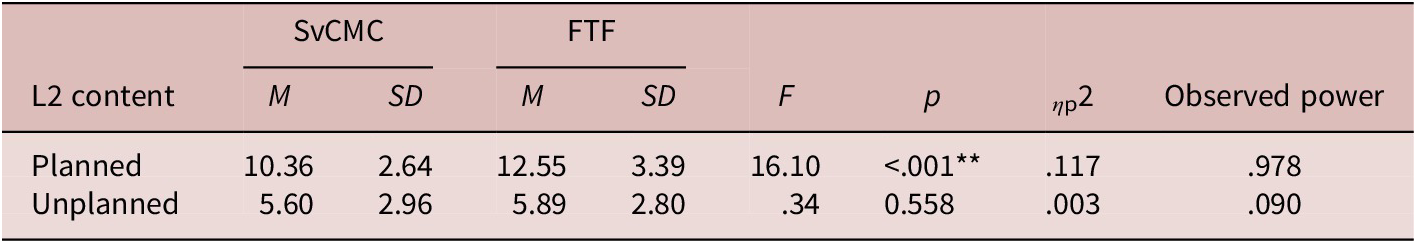

To address the second research question, descriptive and inferential statistics for the two measures of task performance, planned and unplanned L2 content, are provided in Table 2. The effect of planning mode on task performance was determined by a one-way MANOVA (Wilks’ Lambda), yielding a significant main effect, with a large effect size in favor of FTF, F(2,120) = 9.226; p < .001; η p2 = .133. Follow-up univariate tests showed that task performances after FTF planning contained significantly more planned L2 content used than task performances after SvCMC planning (p < .001; η p2 = .117), with a large effect size; additionally, FTF planning resulted in more unplanned content used, but the difference was non-significant, with a negligible effect size (p = 0.558; η p2 = .003). In sum, these results indicate that, compared to SvCMC mode, FTF planning improves the semantic richness of task performance, primarily through greater use of planned L2 content.

Table 2. Follow-up univariate results: task performance.

Note: *p < .05. **p < .01

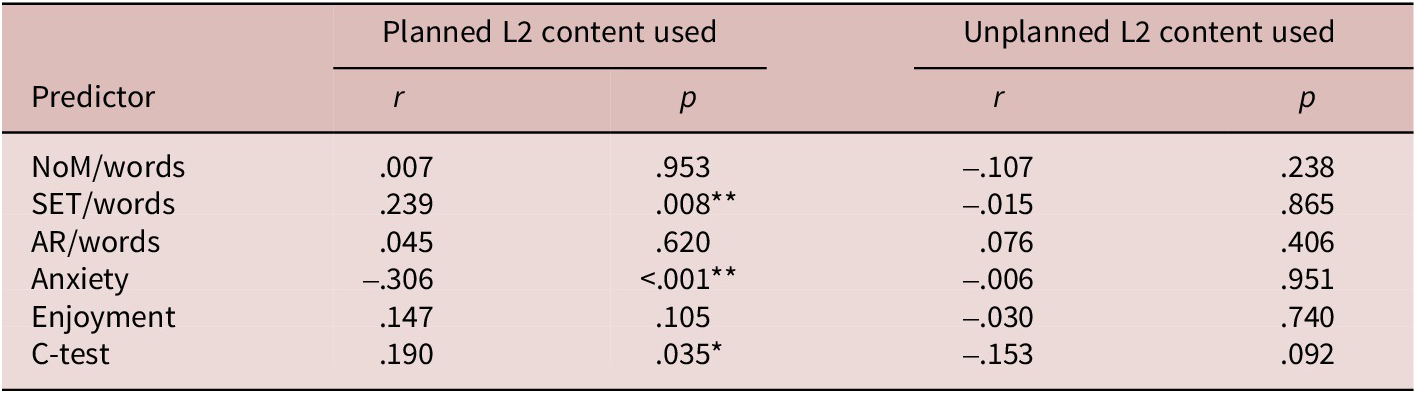

To answer the third research question, we conducted correlations between the five measures of engagement and C-test scores and the two measures of task performances. These correlations identified which predictors were significantly associated with the outcome variables. Table 3 shows that semantically engaged talk, anxiety, and C-test scores were significantly correlated with planned L2 content used. No predictors correlated with unplanned L2 content used.

Table 3. Pearson correlations between predictors and outcome variables.

Note: *p < .05. **p < .01; AR = affiliative responses; NoM = negotiation of meaning; SET = semantically engaged talk.

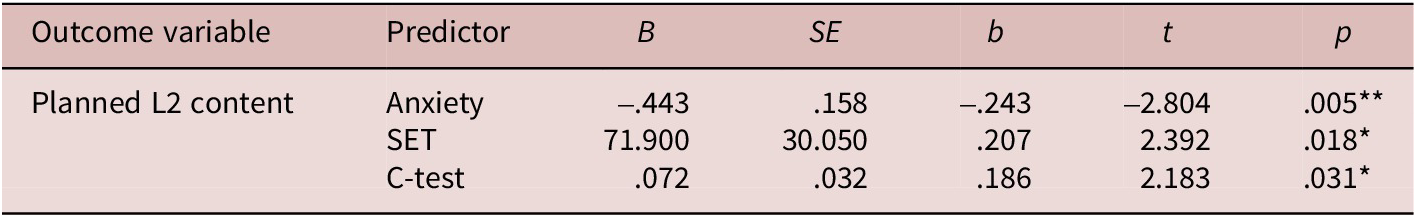

A multiple linear regression was then performed on planned L2 content used in the task (the outcome variable), with semantically engaged talk, anxiety, and C-test scores (the predictors) entered into the regression model. Predictors did not reveal multicollinearity problems as indicated by the variance inflation factors that were below 2 and tolerance levels that were above .9. The results of the regression analyses are summarized in Table 4. The model was statistically significant, F(3,119) = 8.18, p < .001, and accounted for 16% of the variance of the outcome variable (R2 = 0.159; adjusted R2= 0.138). The findings indicate that L2 proficiency (C-test scores) and one indicator of cognitive engagement in planning (semantically engaged talk) positively predicted learners’ use of planned content during task performances, with anxiety during planning emerging as a negative predictor.

Table 4. Multiple Regression Model: Planning engagement and task performance.

Note: *p < .05. **p < .01; SET = semantically engaged talk.

Discussion

Regarding engagement in planning, our results revealed that mode significantly affected engagement levels overall, with FTF interactions yielding significantly higher cognitive engagement (semantically engaged talk), social engagement (affiliative responses), and emotional engagement (lower anxiety) compared to SvCMC mode. This supports the notion that social presence is crucial for fostering engagement (Lowenthal, Reference Lowenthal2009) in the context of collaboratively preparing for a monologue. Previous research has shown that learners using videoconferencing tools often struggle to interpret non-verbal cues from their partner, leading to diminished social presence (Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2023; Qiu, Reference Qiu2024; Qiu & Bui, Reference Qiu and Bui2022). This was evident in this study as well, as fewer affiliative responses, such as laughter, expressions of sympathy and surprise, and enthusiastic agreements, were observed. Moreover, learners in the SvCMC mode experienced significantly higher anxiety. A plausible explanation for this is that anxiety during planning was exacerbated by the reduced availability of visual cues in SvCMC mode, which has been shown to limit learners’ ability to both express their emotions (Caspi & Etgar, Reference Caspi and Etgar2023) and interpret their partner’s message (Aladsani, Reference Aladsani2022). Although this interpretation is speculative due to the absence of direct evidence, alternative explanations for elevated negative emotions, such as a diminished classroom atmosphere (Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2023) or technical disruptions (Qiu & Bui, Reference Qiu and Bui2022), are less convincing given the controlled conditions of the present study. While heightened anxiety in SvCMC has primarily been discussed while interpreting qualitative measures of emotional engagement (Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2023; Qiu, Reference Qiu2024; Qiu & Bui, Reference Qiu and Bui2022; Yamada & Akahori, Reference Yamada and Akahori2009), our findings show that the idiodynamic method may serve as a more sensitive tool for assessing anxiety (MacIntyre, Reference MacIntyre, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023; Lambert & Aubrey, Reference Lambert, Aubrey, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023). Furthermore, SvCMC elicited significantly less semantically engaged talk than FTF interactions, aligning with Qiu’s (Reference Qiu2024) findings. The elevated anxiety in the SvCMC mode may have had a cognitive-depleting effect on learners (Cheie et al., Reference Cheie and Visu-Petra2012), resulting in fewer attentional resources available for reasoning and elaborating on initial ideas. Interestingly, instances of negotiation of meaning were minimal in both modes, and the differences were non-significant, which contradicts previous findings that significantly favored either FTF (Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2023) or SvCMC (Qiu, Reference Qiu2024; Qiu & Bui, Reference Qiu and Bui2022). Negotiation of meaning, which necessarily requires interaction, may have been somewhat muted in this study due to learners’ focus on planning for a distinctly non-interactive (i.e., monologic) task.

As for differences in follow-up task performances, FTF planners produced significantly more semantic content overall (i.e., total idea units) during task performances than SvCMC planners in the follow-up task. This was primarily because of FTF planners’ significantly greater use of planned L2 content (as opposed to unplanned content). From the perspective of Levelt’s (Reference Levelt1989) model of speech processing, this suggests that FTF planning supports the conceptualization stage of speech production to a greater extent than SvCMC planning. It may also indicate that FTF planners were better able to store in memory and recall planned ideas for use in the task. In terms of unplanned content specifically, although the difference in unplanned ideas used between the two conditions was non-significant, both groups showed a non-negligible incorporation of unplanned ideas in their performances (FTF: 31.94%; SvCMC: 35.09%), suggesting that some real-time conceptual elaboration during the task was necessary (Aubrey & Philpott, Reference Aubrey and Philpott2025; Bui & Teng, Reference Bui and Teng2018). These findings also align with the Limited Attention Capacity Hypothesis (Skehan, Reference Skehan and Bygate2015), which suggests that learners have finite attentional resources and that task-related cognitive load determines how these resources are distributed. In this study, the higher engagement during planning among FTF planners likely reduced the cognitive demands of the subsequent task performance. This reduction enabled them to allocate attention not only to incorporating pre-conceptualized content but also to generating ideas spontaneously during performance at a level comparable to SvCMC planners.

The third focus of the study was on exploring the association between engagement in planning and L2 content of task performances. The regression analysis revealed that higher levels of cognitive engagement (semantically engaged talk) and emotional engagement (lower anxiety) in planning as well as higher L2 proficiency (C-test scores) predicted planned L2 content used in task performances. This is evidence that engagement is conducive to learning in general (Fredricks et al., Reference Fredricks, Reschly and Christenson2019) and task performance in particular (Philp & Duchesne, Reference Philp and Duchesne2016). Participating in semantically engaged talk during pre-task planning likely had the effect of deepening processing (Leow, Reference Leow and Leow2019), which, in turn, promoted recall of planned content during the task performance. Additionally, the findings suggest that lower anxiety in pre-task planning was associated with better use of planned content in the task. This supports the notion that anxiety can hinder language acquisition (Dewaele & MacIntyre, Reference Dewaele and MacIntyre2014) and that L2 content processed in anxious states can negatively affect memory encoding and retrieval (Eysenck & Keane, Reference Eysenck and Keane2020). A similar finding was reported in Lambert and Aubrey’s (Reference Lambert and Aubrey2025) case study where learners were tested on their ability to recall L2 content after an interactive task. The significance of our finding is that this association was found when learners recalled L2 content for use in a communicative context (i.e., a monologic task). Finally, C-test scores were also a significant predictor of use of planned content. This is likely because, after learners recalled pre-planned ideas, sufficient L2 knowledge was required to enact the formulation stage of speech production (i.e., to encode ideas with language for use in the task) (Levelt, Reference Levelt1989). This points to the importance of encouraging learners to prepare for both content and language during planning tasks (Aubrey et al., Reference Aubrey, Lambert and Leeming2022).

Conclusion, limitations, and future directions

This study investigated the impact of SvCMC on cognitive, social, and emotional engagement in planning and subsequent task performance. The results suggest that compared to SvCMC, FTF was more facilitative of learner engagement and better supported the conceptualization stage of speech production in planning. Additionally, learners’ proficiency, cognitive engagement, and emotional engagement, as measured by a C-test, semantically engaged talk, and anxiety, predicted learners’ recall and use of planned L2 content in performances. The findings align with theoretical perspectives that predict social presence enhances engagement (Lowenthal, Reference Lowenthal2009), which subsequently facilitates learning (Hiver & Wu, Reference Hiver, Wu, Lambert, Aubrey and Bui2023).

In terms of limitations, although a sample size of 64 for each group is large compared to other task engagement studies, a larger sample would have provided opportunities to investigate more predictor variables (e.g., working memory). Additionally, only one type of task was used. Performances with other task types could interact with the SvCMC mode to produce different engagement effects. Furthermore, while the study was conducted in a laboratory setting to allow for more direct attribution of differences to mode, its ecological validity is limited.

In addition to addressing the limitations mentioned above, future research should aim to strengthen the connection between engagement and learning outcomes in TBLT. This could begin with the use of more precise methods for measuring engagement, such as qualitative discourse analysis to uncover emergent themes (e.g., Lambert & Zhang, Reference Lambert and Zhang2019), or the triangulation of idiodynamic ratings with objective biometric indicators of cognitive and emotional engagement, using tools such as facial expression analysis (Lambert & Aubrey, Reference Lambert and Aubrey2025) and electroencephalography (Lambert, Reference Lambert2025). Such measures could then be related to the incidental language learning that occurs during task performance across discoursal, grammatical, lexical, and phonological levels (e.g., Hiver & Dao, Reference Hiver and Dao2025), which would potentially offer richer insights into the role of engagement in second language acquisition.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263126101545.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Research Grants Council, General Research Fund, Hong Kong, grant number: 14604423.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.