Impact statement

This paper introduces an innovative approach that combines generative artificial intelligence with hydraulic models to transform how water utilities respond to rapid urban growth. By automating capacity assessments and infrastructure augmentation planning, the integrated Gen AI–hydraulic tool significantly reduces manual workload while maintaining engineering and water utility standards. This proposes a significant step-change in how water utilities implement the modelling and design of water distribution systems.

Background of WDS planning and design

Water distribution systems (WDS) are a fundamental component of urban infrastructure. It is designed to ensure communities have access to clean water with adequate pressure. For most developed countries, water infrastructure is well established since the nineteenth century (Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Miotti, Swaminathan, Klemun, Strzepek and Siddiqi2017) and continues to reliably supply customers. Planning and design of water systems to support sustainable development (i.e. housing affordability (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (2021)) and future growth in the current time, therefore, mostly focuses on identifying solutions for water network expansion. These activities primarily involve extensive use of a calibrated steady-state hydraulic model. The steady-state hydraulic model is the mathematical approximation of a real WDS, which simulates the steady condition of the flows in the network at a specific point of time (i.e. steady-state simulation) or over a period (i.e., extended period simulation) (Do, Reference Do2017). Based on two physics principles (the mass and energy conservation), the hydraulic model can estimate relatively accurately the pressure and flow of the piping network and provide insight into the WDS hydraulic conditions. Some well-known open-source steady-state hydraulic models commonly used for research purposes are the EPANET model (Rossman, Reference Rossman2000) and Water Network Tool for Resilience (WNTR) (Klise et al., Reference Klise, Bynum, Moriarty and Murray2017).

Three main types of water distribution planning and design were identified in Walski (Reference Walski2015), including master planning, capital planning and land development. The master planning and capital planning are internal studies conducted to provide long-term planning (for master plan) and short-term consideration (for capital plan) of water infrastructure upgrade. On the other hand, the land development projects are the exercises conducted to answer external requests from private developers or land rezoning authority. The level of assessment required for an individual request varies from a simple hydraulic modelling task to demonstrate the requirement of small main extension to complex modelling works aimed at providing practical and feasible solutions to the developers while maintaining service levels for existing customers. Under high growth conditions, water utilities often face a large volume of development proposals. This creates significant scaling challenges for the planning team with constrained staff and resources because planning engineers must manually configure multiple scenarios, execute hydraulic simulations and interpret results for each request. These manual steps limit efficiency and consistency in delivering timely responses. Therefore, there is a clear need for tools that enable automated interaction between planners, hydraulic models, engineering standards and utility governance requirements to support scalable planning workflows. Generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI), particularly large language models (LLM), offers a pathway to address this gap by enabling natural language interaction with engineering tools.

Advances of AI in WDS modelling and challenges in practical application

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are gaining attraction in the WDS modelling domain. Most of these works focus on improving the computational time and accuracy of hydraulic models. For example, Bonilla et al. (Reference Bonilla, Zanfei, Brentan, Montalvo and Izquierdo2022) used a graph convolutional network for pump speed estimation. Kerimov et al. (Reference Kerimov, Taormina and Tscheikner-Gratl2024) proposed a data-driven metamodel concept using edge-based graph neural network (GNN) as a surrogate for a physical-based hydraulic model. Truong et al. (Reference Truong, Tello, Lazovik and Degeler2024) used GNN to improve the estimate of pressure in WDSs. Ye et al (Reference Ye, Do, Zeng and Lambert2022) and Ye et al. (Reference Ye, Zeng, Do and Lambert2024) introduced a physics-informed ML concept for reconstructing transient pressures in pipe networks from pressure data. Although these studies demonstrated the capability of using AI to improve some specific aspects of hydraulic models within the range of training datasets, the applicability to real-world hydraulic networks with complex operational components (e.g., booster pump stations, pressure reducing valves, pressure sustaining valve, flow control valves, etc.) of these ML tools in water utilities to answer practical hydraulic questions remain challenging.

Gen AI, represented by LLMs, is a significant advancement in the AI field. Trained on vast datasets from reliable data sources, Gen AI is capable of providing general answers as well as fundamental engineering knowledge. In addition, the LLM tools, such as ChatGPT or Google Gemini, allow users to interact with specific domain knowledge by natural language, making interaction with complex systems more intuitive. Sela et al. (Reference Sela, Sowby, Salomons and Housh2025) outlined the potential benefits of Gen AI to water utilities in data analysis, preserving system knowledge and enhancing training and operational efficiency. However, the study also highlighted the uncertainty in the accuracy and reliability of LLMs in answering complicated tasks due to limited feeding context, empirical metrics and evaluation methods. Given a strict cybersecurity requirement in the water utility to protect confidential data and information, third-party LLM models are unlikely to gain access to sensitive databases or be retrained for water utility-specific applications. This poses the need for alternative approaches to incorporate LLMs into the daily WDS planning and design work within the utility environment.

Hydraulic AI agent concept for WDS planning and design

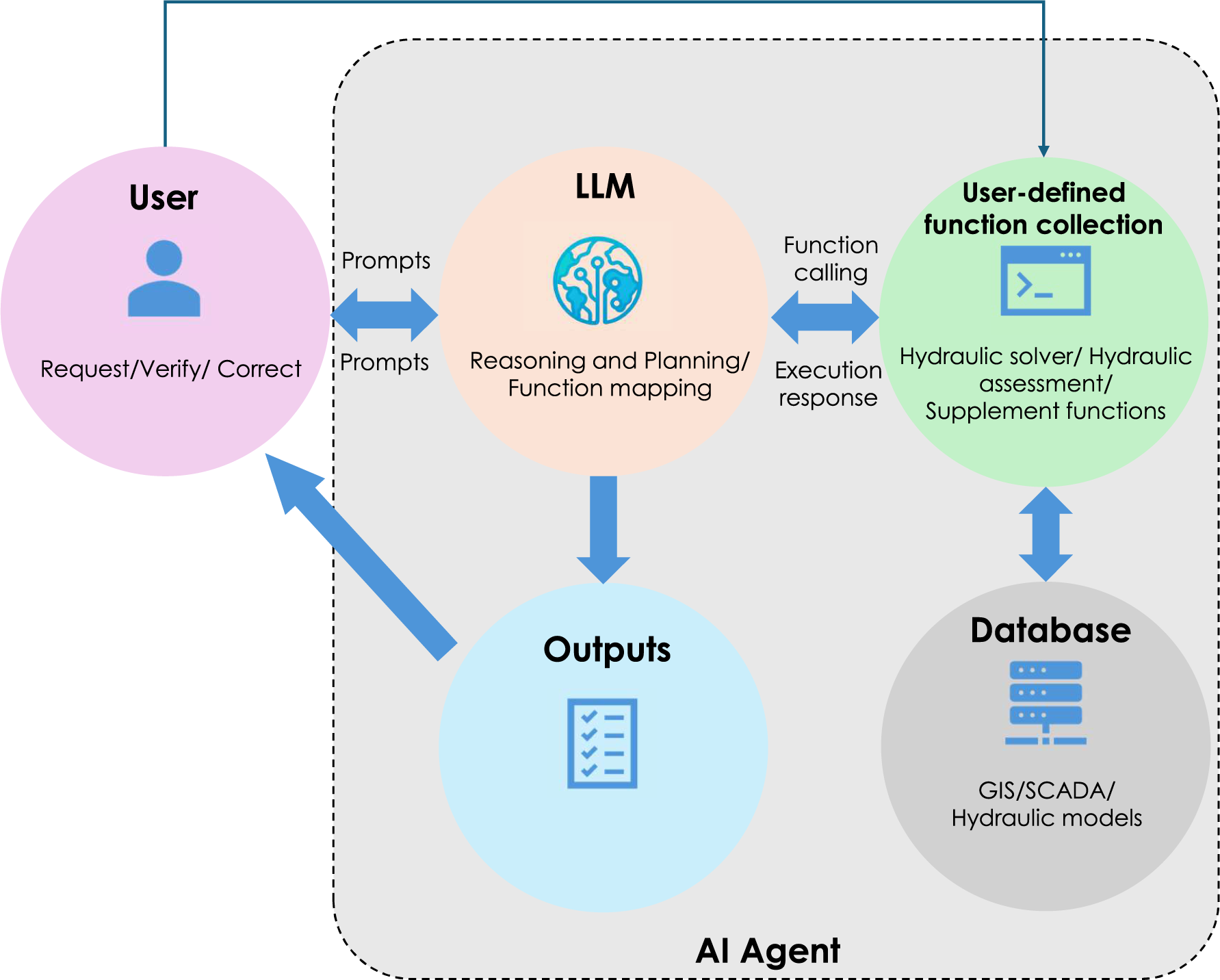

Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework of an LLM-based AI hydraulic agent that enables the automation of some WDS planning and design processes, while allowing integration with water utility systems. The concept demonstrates the interaction between four components: the user, LLM, function collections and utility databases, which can be assessed from the function collection. Unlike publicly available Gen AI tools that generate invalidated functions, the proposed approach relies on a curated library of internally developed hydraulic functions aligned with the water utility design standards and service criteria. All model calculations remain on secured utility systems, which ensures protection of sensitive WDS data while leveraging LLMs purely for automation of function selection, visualisation and hydraulic result extraction and interpretation.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of the Gen AI-based hydraulic agent.

The user is responsible for initiating requests in natural language and providing additional contexts to ensure the AI receives sufficient information to perform the task. For example, required inputs for an assessment of a land division request may include the site location, land use type, proposed number of allotments or metre sizes. Additionally, the user is also responsible for verifying the agent’s outputs or directing the AI to implement further analyses to correct the outputs.

The core of the AI agent is the LLM, which is accountable for interpreting the user request, acquiring additional data and implementing actions. It utilises two built-in features of the LLM: reasoning and planning and function calling. The LLM “reasoning and planning” feature typically involves partitioning natural language questions into chains of immediate steps and subsequently generating a series of actions to achieve the request (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Xia, Xiao, Chan, Liang, Florence, Zeng, Tompson, Mordatch, Chebotar and Sermanet2022; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Gu, Ma, Hong, Wang, Wang and Hu2023). The “Function calling” mechanism, introduced by Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Moon, Tabrizi, Lee, Mahoney, Keutzer and Gholami2024), within the context of LLM refers to its capacity to identify and execute predefined functions to deliver precise and structured outputs. This feature allows the LLM to handle complex inquiries and enables the LLM to integrate with a wide range of external systems (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang, Peng, Chen, Zhou, Gu, Zhuang, Guo, Yu, Wang and Zhao2025).

User-defined function collection is the engine of the AI agent for implementing WDS planning and design tasks. Each function is a predefined block of programming script or computational tools that takes parameters as inputs to simulate a designated result. Function collection ranges from a simple trigger to run the hydraulic solver, a script to direct where the data should be extracted, to complex programs such as tracing the hydraulic grade line (HGL) from a given node to its source at a defined time step or an optimisation tool to determine optimal augmentation. These functions require domain expertise and engineering technical knowledge to develop. In addition, as the utility databases can be assessed by the user predefined functions, this minimises the direct exposure of water utility sensitive information to the LLMs, therefore, reducing the security risk concerns.

Demonstration of an AI hydraulic agent

The agent is programmed in Python language and available from GitHub. For the LLM component, we adopted the “gpt-4o-mini-2024-2107-18” module from OpenAI via the OpenAI application programming interface. Hydraulic simulations are performed using the WNTR Python package as the hydraulic engine.

Case study 1: We used a land development service request as the first case study to demonstrate the capabilities of the AI agent. A collection of functions (listed in Table 1) was developed to assist the AI in performing land development requests. To identify if the existing system has enough capacity or which sections of the piping network need to be augmented to support future water users, a hydraulic simulation triggered by the “Run hydraulic simulation” function must be performed for two scenarios:

-

• The base scenario, representing the current hydraulic system conditions, and

-

• The future scenario, where additional water demand from the development is added by the “Add demand” function, represents the future system demand when the development is supplied from the network.

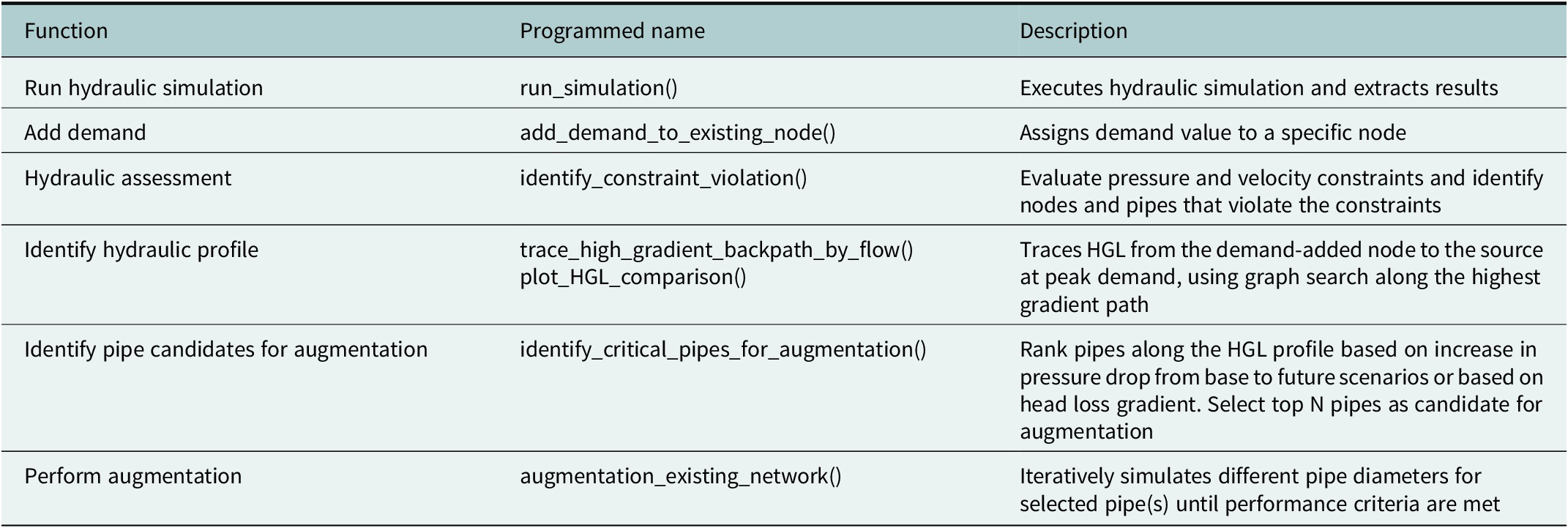

Table 1. Example of a function collection enabling WDS planning and design tasks in the AI hydraulic agent

Hydraulic performance, such as nodal pressure drop, pipe velocity, tank level, upstream and downstream pressure of a PRV, is then compared between the base and future scenarios by the Hydraulic assessment function. If any performance criteria are violated, the AI will simulate possible augmentation options and inform the user of necessary upgrades. In order to implement this process, additional advanced tools are programmed, including “Identify hydraulic profile,” “Identify pipe candidates for augmentation,” and “Perform augmentation.” Detailed descriptions of these functions are provided in Table 1.

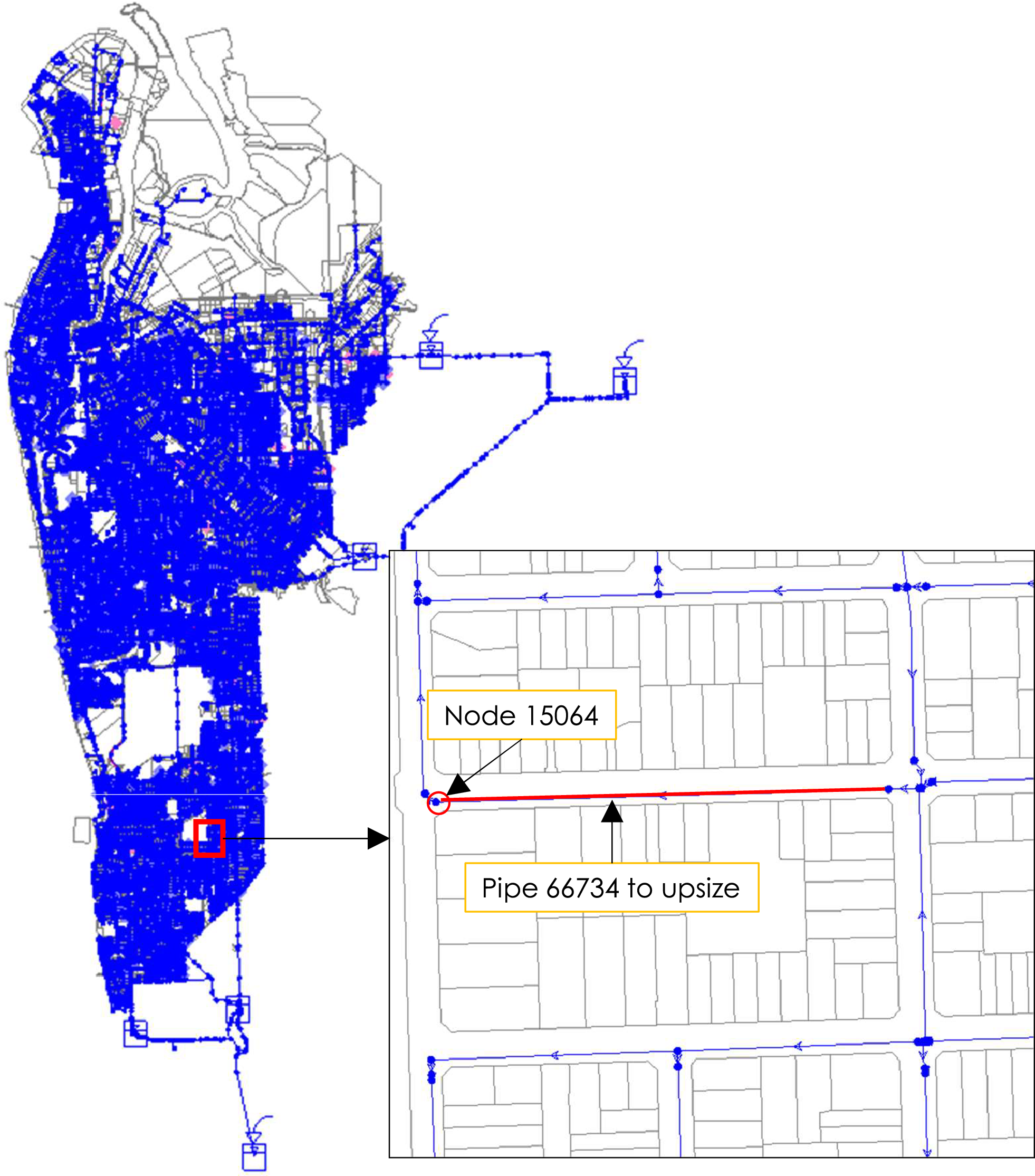

The performance of the AI agent is demonstrated through a real-world network example of a land division request in a suburban area in South Australia, Australia. The WDS network model is depicted in Figure 2, which consists of 28,985 nodes, 33,200 pipes, and supplies from multiple water sources. For this demonstration, it is assumed that 20 L/s is requested from the customer near node ID 15064 of the network. For hydraulic assessment, the following criteria are applied:

-

• Minimum service pressure ≥ 20 mH,

-

• Maximum pipe velocity ≤ 2.5 m/s,

-

• Pressure drop due to the new demand must not exceed 10% of the minimum base scenario pressure (to avoid negative impacts on existing customers).

Figure 2. Hydraulic network model and development location in Case study 1.

Figure 3 depicts the interaction between the user and the AI agent. As can be seen from the figure, a request is raised by the user in plain language: “Please add demand to node.” The LLM’s reasoning and planning capabilities identify that the demanded information is missing and respond accordingly. Once the user provides the required demand (20 L/s), the AI agent automatically executes a sequence of actions: adding the demand, running the simulation, performing a hydraulic assessment, and identifying pressure violations. In this case, the AI identified 12 nodes with pressure drops exceeding the 10% threshold. It correctly plotted the HGL profiles for both base and future scenarios at the peak demand time and identified the correct augmentation: upsizing approximately 196 m of DN100 ductile iron pipe (internal diameter 113 mm) to DN150 (internal diameter 160 mm). This result well matches the outcome of an independent assessment by a hydraulic engineer. It is noted that one of the most common reasons a system requires augmentation is excessive pressure drop caused by additional demand. Changes in minimum HGL, which is computed as ground elevation (unchanged with the increased demand) plus system pressure, and the related magnitude of headloss gradient (metres of pressure loss over the length of the pipe) indicate where the system no longer meets performance criteria and which pipes would benefit most from a diameter upsize. Increasing pipe diameter would lower flow velocity and frictional losses, thereby improving minimum service pressure at downstream nodes. Although maintaining minimum pressure is a key operational constraint, the practical output of the assessment is the required pipe augmentation (e.g., upgraded diameter and length), from which cost estimates can be derived and communicated to developers.

Figure 3. Case study 1: Demonstration of the AI agent responding to a land-division request.

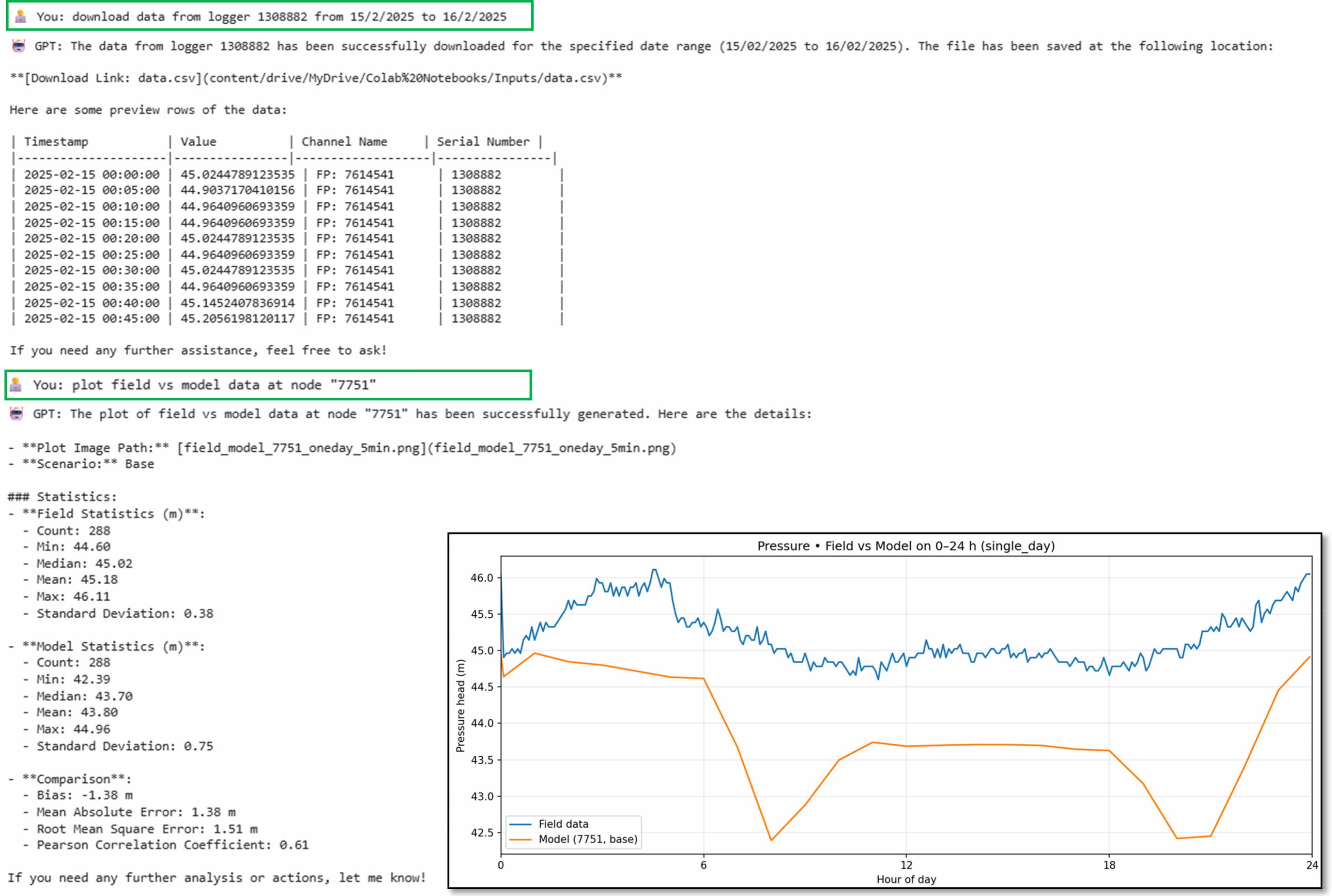

Case study 2: This second example demonstrates the agent’s role in handling field data. We provided the agent with the logger number of a pressure device and a defined time range and instructed it to download the data and compare the results with the model at a node corresponding to the logger site. As seen in Figure 4, the agent was able to retrieve and save the logger data into a specified location. In addition, the agent was also able to generate both visual and statistical comparisons between the observed data and the simulated pressure at the requested node.

Figure 4. Case study 2: Demonstration of the AI agent downloading and comparing data.

Further exploration in natural language prompts, such as asking the AI agent to execute individual tasks (e.g., adding demand at a different node, running a simulation, or plotting a hydraulic profile at a specified time), was implemented. In all cases, the agent responded accurately, highlighting the potential of LLM-based automation for WDS planning and design.

Conclusions

The application of generative AI has the potential to transform WDS planning and design by enabling automation in hydraulic model simulations and performance assessments. This is not intended to replace human expertise, rather a tool that can help save time, assist workflow scaling, improve consistency and enable engineers to focus on higher-level decision-making. The function-calling mechanism significantly enhances the capabilities of large language models, allowing them to deliver complicated, accurate outputs while interacting with external tools and data sources and is adaptable to meet the water utility’s criteria. Unlike other AI approaches that rely on statistical features or patterns from historical data, the effectiveness of this approach relies on the development of user-defined functions, which require domain-specific knowledge to ensure accurate analyses. While this work demonstrated some of the potential of generative AI in WDS applications, further work is required to quantify the benefits of using this approach on a large scale, its limitations and its potential benefits of analysing multiple scenarios to improve decision-making under uncertainty.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/wat.2025.10012.

Data availability statement

The code and data presented in this study are available on GitHub: https://github.com/NhuDoADL/HydraulicGPT.

Author contribution

N.D., P.H: Conceptualisation, N.D., AM: methodology, writing; A.M, P.H: review, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools

For this research, the “gpt-4o-mini-2024-2107-18” module from OpenAI via the OpenAI application programming interface was used in the Python code to demonstrate the integration of a Large Language model with hydraulic simulation tools.

Comments

Dear Editor,

Please find attached the manuscript ‘Accelerating Water Distribution Systems Planning and Design with Generative Artificial Intelligence Models’ by Nhu Cuong Do, Angela Marchi and Patrick Hayde, which we would like to be considered for publication in Cambridge Prism: Water as a Rapid Communication article.

Housing affordability is one of the key aspects required for sustainable development and society. However, the timely delivery of new homes is often constrained by the need to upgrade and expand essential infrastructure. For water utilities, responses to growth typically involve intensive hydraulic analysis to assess water distribution systems capacity, identify upgrade needs, and evaluate options for system extensions. This process becomes significantly complex and resource-intensive under high growth conditions.

Our paper addresses this challenge by presenting an innovative concept that integrates generative artificial intelligence with hydraulic models to form an AI agent supporting water distribution system planning and design tasks. Specifically, our approach leverages recent advances in large language models, including “reasoning” and “function calling” features, within a framework suitable for operational deployment in utility environments.

We demonstrate this concept with a real-world case study from South Australia Corporation, showing that the AI agent efficiently analyses development requests, triggers hydraulic simulations, and recommends augmentations. This framework significantly reduces manual workload while maintaining engineering and water utility standards.

We believe this framework offers immediate benefits for water utilities and provides a pathway toward more sustainable and scalable infrastructure planning.

Thank you for considering our work. We look forward to the opportunity to contribute to Cambridge Prism: Water and to the broader discussion on the future of AI in water engineering and infrastructure planning.

Kind regards,

Nhu Do