Academic and professional conferences are mainstays of numerous disciplines and industries. These events help foster and disseminate new knowledge, offer networking opportunities, build community, facilitate training, and aid professional development. Yet not all group members participate equally in their professions’ conferences. Some may simply attend an event, whereas others present their research in a range of formats, including as invited or keynote speakers. Indeed, there is variability in the degree and kind of involvement. Numerous researchers (e.g., Casadevall and Handelsman Reference Casadevall and Handelsman2014; Hansen and Budtz Pedersen Reference Hansen and Pedersen2018; Walters et al. Reference Walters, Hassanli and Finkler2020) have documented and considered the effects of unequal participation in conferences, raising the question: Why does it matter who participates and who fills various roles?

Those in more prestigious roles gain greater visibility and can thus accelerate their careers. They can disseminate their research to larger audiences and are more likely to be asked to participate in future events. Casadevall and Handelsman (Reference Casadevall and Handelsman2014:1) note that “speaker rosters are often used as a starting point for planning other meetings, amplifying the impact of each event.” Invited speaking roles are particularly important. Such invitations offer evidence of external recognition of expertise that often factors into hiring and promotion decisions. These invitations make important statements about whose research the profession values most: invited speakers offer students, early-career scholars, journalists, and members of the public examples of what successful practitioners look and sound like (e.g., Casadevall and Handelsman Reference Casadevall and Handelsman2014; Nittrouer et al. Reference Nittrouer, Hebl, Ashburn-Nardo, Trump-Steele, Lane and Valian2018; Walters et al. Reference Walters, Hassanli and Finkler2020). Conference proceedings can also be published officially by the organization or informally by the organizers of sessions, offering an additional benefit for often-invited contributors. Critically, just as visibility can catalyze a career, invisibility can stifle it. Those not invited to speak at conferences and other events may have more difficulty establishing and maintaining research collaborations, finding publication venues, and connecting and interacting with editors, funders, and journalists (Hansen and Budtz Pedersen Reference Hansen and Pedersen2018).

Conference participation is thus usefully understood as a source of capital (Walters et al. Reference Walters, Hassanli and Finkler2020:340). Pierre Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu, Richardson and Nice1986:241–242) defined capital as a “force inscribed in the objectivity of things so that everything is not equally possible or impossible.” For Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu, Richardson and Nice1986:243), capital can be economic (money and goods), cultural (mannerisms and specialized knowledge), and social (group memberships and networks of connections). Economically, conference participation has an impact on hiring and promotion decisions. Culturally, it provides opportunities to practice formal presentations, engage with others’ research, and demonstrate competence. Socially, it offers networking opportunities. As Bourdieu has argued, these three forms of capital can convert into one another. It is thus not surprising that exclusion from prestigious and particularly invited conference roles “contributes to poorer career outcomes . . . [and] has implications for earning capacity” (Walters et al. Reference Walters, Hassanli and Finkler2020:350). Even though decisions about conference or keynote invitations may appear inconsequential, they do matter.

In this article, we consider the ways gender identities affect participation in one conference—the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology (SAA)—the flagship conference for academic and cultural resource management (CRM) archaeologists in the United States.Footnote 1 We first review the existing literature about gender-based inequalities in conferences of multiple disciplines before considering the SAA annual meeting specifically. We then present the results of our analysis of SAA annual meeting programs over a 23-year period from 2002 to 2024. We argue that gender plays a strong role in determining who occupies positions of prestige and that decisions about who is “qualified” are influenced by gender-specific notions of fit and expertise. Perhaps most notably, although women and men are similarly likely to fill self-selected leadership roles, women are less frequently invited to fill prestigious roles by their peers. Given the available literature on participation in archaeology more broadly (e.g., Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024), such exclusion is likely amplified for women with multiple marginalized identities. We conclude by recommending a series of interventions—to session organizers, session participants, and the SAA—to help redress gender-based differences in conference participation.

Previous Research on Gender-Based Inequities in Conference Participation

As described in detail in the introductory article for this themed issue (Kurnick and Fladd Reference Kurnick and Fladd2026), archaeologists have analyzed the relationships between gender identities and many aspects of archaeological practice, including publications, citations, mentorship, and hiring and retention. Researchers from multiple disciplines have also examined the relationship between gender identity and conference involvement. Despite the recognized need for an explicitly intersectional and Black Feminist approach (Sanchez et al. Reference Sanchez, Hypolite, Newman and Cole2019), the infrequent self-reporting of several aspects of identities—including race, class, and sexual orientation—has limited such analyses. Existing literature does, however, demonstrate that men often gain greater visibility at conferences and tend to benefit from their gender identities. In a consideration of the Australasian Evolution Society conference in 2013, for instance, Jones and colleagues (Reference Jones, Fanson, Lanfear, Symonds and Higgie2014) assessed the relative length of talks given by men and women at both the student and post–PhD levels. Despite roughly equal participation and interest in presenting, men were found to request longer presentation formats more often than women, resulting in 17% (for students) and 23% (for post-PhD) greater speaking time for men. In another example, Roberts and Verhoef (Reference Roberts and Verhoef2016) analyzed the ranking of individuals’ submissions to the Evolution of Language conference before and after the implementation of double-anonymous review. They found that, when authors’ gender identities were known, men’s submissions ranked higher, and women’s submissions ranked lower. Such rankings changed significantly when the authors remained anonymous.

Previous studies from other disciplines have also found that the gender identity of the conference or session organizer dramatically affects the gender identity of the participants (e.g., Isbell et al. Reference Isbell, Young and Harcourt2012; Nittrouer et al. Reference Nittrouer, Hebl, Ashburn-Nardo, Trump-Steele, Lane and Valian2018; Zaza et al. Reference Zaza, Ofshteyn, Martinez-Quinones, Sakran and Stein2021). Casadevall and Handelsman (Reference Casadevall and Handelsman2014) investigated the influence of woman “conveners” (organizers) at conference sessions run by the American Society for Microbiology: sessions organized solely by men included an average of 25% women speakers, whereas those with one or more women convenors averaged 43% women speakers. Similarly, Sardelis and Drew (Reference Sardelis and Drew2016) found a positive relationship between women organizers and women presenters for symposia sessions at both the Society of Conservation Biology (from 1999 to 2015) and the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (from 2005 to 2015). They argue that quality or ability was not the limiting factor but rather “gender-based disparities within the sciences that are based on the orientation of individuals towards others” (Sardelis and Drew Reference Sardelis and Drew2016:8; see also Corona-Sobrino et al. Reference Corona-Sobrino, Garcia-Melon, Poveda-Bautista and Gonzalex-Urango2020).

In a discipline more closely related to anthropological archaeology, Isbell and colleagues (Reference Isbell, Young and Harcourt2012) examined participation in sessions about primatology at the American Association of Physical Anthropologists meetings over the course of 21 years. The gender of a symposium organizer again significantly influenced the rate of women’s participation. When women organized symposia, the percentage of women-first-authored papers jumped from 29% to 64%. Notably, the latter number closely aligns with the 65% of women presenting on primatology at the conference in general (Isbell et al. Reference Isbell, Young and Harcourt2012:3). To account for this difference, the authors propose that homophily—a preference for interactions with those who resemble you (see McPherson et al. Reference McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook2001)—may be more significant for men than women (Isbell et al. Reference Isbell, Young and Harcourt2012:4).

Scholars have also addressed gender-based trends in participation within archaeology conferences specifically. Chen and Marwick (Reference Chen and Marwick2023) analyzed data from three such conferences held in 2018—the annual meetings of the SAA, the European Association of Archaeologists, and the Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology—to investigate the relationships between presenters’ perceived gender identities and their research topics. At each conference, there were strong correlations between women presenters and specific themes, including cultural heritage, GIS, and isotope analyses. Chen and Marwick suggest that such correlations “may result from a combination of subtle, implicit biases . . . as well as large-scale structural constraints embedded in the social milieu of archaeological practice” (Reference Chen and Marwick2023:570).

Focusing on the SAA and building on Zeder’s (Reference Zeder1997) analysis of 1994 survey data, Jo Ellen Burkholder (Reference Burkholder2006) conducted an analysis of a random sample of participants in the 2000 SAA annual meeting.Footnote 2 Her analysis revealed that conference participants were approximately 35% women and 64% men, but that women participated more often than men in poster sessions (Burkholder Reference Burkholder2006:28–29). To explain these results, she suggested that “poster sessions are viewed as less prestigious and . . . some women may have internalized messages that their work is . . . more suited to the lesser venue” (Burkholder Reference Burkholder2006:30).

Burkholder’s analysis of the 2000 SAA annual meeting also revealed that women participated more often than expected as organizers and chairs of sessions and were more likely to be sole or first authors. For Burkholder (Reference Burkholder2006:30), such results can be understood as women taking control over their work or as providing valuable service to the discipline. Although not quantified in the same way as other studies outlined earlier, Burkholder similarly found that “where women are represented in the largest numbers, they appear to be there because of their own initiative or that of other women” (Reference Burkholder2006:30).

In this article, we present the results of analyses of a 50% sample of SAA annual meeting programs over a 23-year period, from 2002 to 2024. We consider continuities and changes in participation at the SAA annual meeting over this period to address several questions. Do gender-based inequities persist in conference participation and invitation? Have they changed over time? And are they similar to those documented in other disciplines’ conferences?

Participation in the Annual Meeting of the SAA

Presentations at the SAA annual meeting are organized into different session formats, including general sessions, poster sessions, symposia, poster symposia, forums, and lightning rounds (Supplementary Material 1).Footnote 3 General sessions and poster sessions are organized thematically by the SAA Annual Meeting Program Committee and comprise papers or posters submitted individually by presenters to the conference submission portal, rather than as part of an organized session. The Program Committee designates a chair for general sessions and sometimes for poster sessions from among those who volunteer to serve that role (Supplementary Material 2). Symposia are made up of a collection of papers organized around a “well-defined theme” (Society for American Archaeology 2025), proposed and orchestrated by a symposium chair(s). Symposia chairs select and invite presenters, as well as one or more discussants, although discussants are not required. Poster symposia are similarly organized by a chair(s) and include presenters but lack discussants. Forums are interactive sessions organized around a defined theme and include discussion between and among the participants and audience. Discussants are the main participants in forums, which are organized and invited by a moderator. Lightning rounds include one hour of three-minute presentations organized around a particular topic, followed by an hour of discussion.Footnote 4 Like forums, they include discussants invited by a moderator.

There are three ways that participants in the SAA annual meeting come to fill different roles within these session formats (Table 1): they may self-select to fill a role, be assigned a role by the SAA Program Committee, or be invited by a peer. Commonly, participants can decide (self-select) to submit a paper or poster to be presented in a general session or poster session. Individuals can also self-select to organize a symposium (paper or poster), lighting round, or forum. Chairs of general sessions and poster sessions are assigned by the Program Committee, often based on calls for volunteers. Lastly, participants may be invited to fill certain roles by their peers who are in self-selected roles. These roles include both presenters and discussants in symposia or poster symposia, as well as discussants in forums and lightning rounds.

Table 1. Types of Roles at the Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology.

In short, sessions at the annual meeting of the SAA are of two types: (1) general (general sessions and poster sessions), the makeup and participation of which are decided by the Program Committee, and (2) invited (symposia, poster symposia, forums, and lightning rounds), for which the chair(s) or moderator(s) decide on makeup and participation. Self-selected roles speak to the degree to which individuals see themselves as qualified to fill different positions and their willingness to fill service roles. Roles that individuals must be invited to fill by their peers (such as a discussant invited by a symposium chair) speak to invitedness, or how one individual perceives the qualifications and prestige of their peers. As noted earlier, invited presentations are important sources of economic, cultural, and social capital. Although both general and invited sessions provide networking opportunities, name exposure, and resume/CV additions, invited opportunities demonstrate the intentional inclusion of someone based on their reputation as a scholar with a specific expertise, and to a degree that warrants their inclusion. “Invited” talks on resumes may be important in both academia and CRM, being valuable in consideration of promotion to tenure and of merit-based raises in the former, or for initial hiring or promotion in the latter.

Methods

To assess gender representation and participation in the annual meeting of the SAA, we analyzed 23 years of programs from 2002 to 2024. For each year, we recorded a 50% sample of the entire program using a random number generator to select session numbers for inclusion.Footnote 5 For selected sessions, we recorded the year, session number, session format, participant names, participant roles, authorship, and perceived gender identity (see Supplementary Material 1). We did not record titles or subject matter, although a recent study by Chen and Marwick (Reference Chen and Marwick2023) found a correlation between presenters’ perceived gender identities and their presentation topics.

Importantly, we acknowledge that gender is nonbinary and extends to include identities beyond men and women. But because SAA annual meeting programs do not include information on self-reported gender, we relied by necessity, as have several other scholars (e.g., Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Johnson, Price, Record, Rodriguez, Snow and Stocking2023:330), on the perception of an individual’s first name. For this study, the lead author assigned gender after initial data collection to minimize inter-analyst bias and variability in the perception of names. In cases that were ambiguous, the lead author verified gender using faculty web pages, online public profiles, or other online resources.Footnote 6 We recognize that this approach is notably and admittedly imperfect (e.g., Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014:526; Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019:385; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2020a:410–411). In their Gender Equity and Sexual Harassment Study survey, Vanderwarker and colleagues (Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018) found that 1% of survey respondents were transgender. Extrapolating from this finding, our dataset likely includes around 150 transgender and nonbinary individuals whose genders we wrongfully assigned. Despite the limitations of our methodology, the scale of data collection ensures that our results remain useful and meaningful.

The lack of available information about other aspects of participants’ identities excluded intersectional considerations of how different combinations of identities influence scholars’ experiences at the SAA. Indeed, it is difficult to find self-reporting of other dimensions of identity, including race, class, and sexual orientation, and these dimensions cannot reliably be assigned by others. Self-reporting through surveys and interviews is thus necessary to accurately capture the intersectionality of gender-based conference participation (see Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024), even though such surveys also suffer from limitations, including response biases and low response rates (see discussion of responses to the American Anthropological Association survey in Brodkin et al. Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011). Here, we begin to answer questions about gendered conference participation by analyzing solely publicly available data.

Data collection resulted in 34,765 data points, representing approximately 14,900 discrete individuals who participated in the annual meeting of the SAA between 2002 and 2024. Our data thus provide the largest-scale and most comprehensive study of the SAA annual meeting to date. We interrogated these data across many possible lines. In the next section, we present the patterns that emerged regarding overall participation, self-selected leadership roles, and invited roles.

Analysis and Results

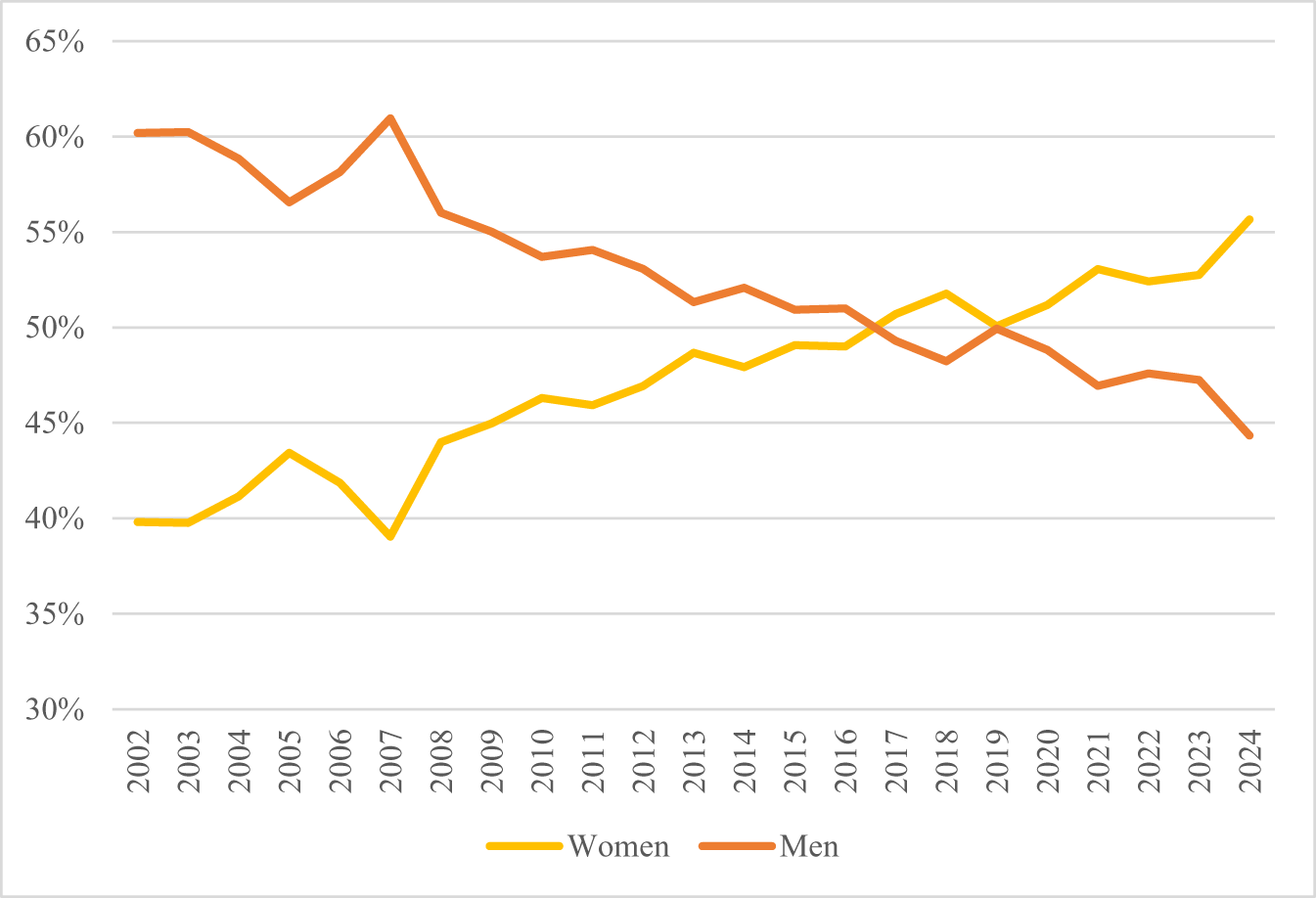

Between 2002 and 2024, women and men participated in the SAA annual meeting at an average of 48% and 52%, respectively (χ2 = 214.54, df = 2, p < 0.0001). This figure has varied by year within our sample, with women’s participation ranging from 39% to 61% (Figure 1). In 2002, the earliest year in our sample, participation was 40% women and 60% men, whereas in 2023 participation was 56% women and 44% men. It was not until 2017 that women attained or surpassed 50% representation; since then, they have been represented at parity or higher.

Figure 1. Participation of men and women in the annual meeting of the SAA between 2002 and 2024 across all session formats and all roles.

Parity, however, is not necessarily the appropriate baseline. Analyzing survey data, Cramb and colleagues (Reference Cramb, Ritchison, Hadden, Zhang, Alarcon-Tinajero and Xianyan Chen2022:373–374) suggest that the gender ratio of professional archaeologists has changed dramatically over time, with women making up approximately 28% of PhD recipients in the 1970s, 50% in the 2000s, and 64% in the 2010s. Analyzing published graduation rate data in the American Anthropological Association AnthroGuide, Speakman and colleagues (Reference Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Justin Cramb, Jones and Lulewicz2018:8) note that “since 1993, 60% of all anthropology doctoral recipients are female.” Most recently, Hutson and colleagues (Reference Hutson, Johnson, Price, Record, Rodriguez, Snow and Stocking2023:330–331), using a combination of the AnthroGuide and the National Science Foundation’s National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics Survey of Earned Doctorates, documented changing numbers of degrees awarded to men and women by year from 1976 to 2021. The percentage of doctoral degrees awarded to women range from a low of 22% in 1976 to a high of 64% in 2013.

Additionally, women’s participation in the field may be underrepresented when only considering PhD attainment, because such counts exclude archaeologists who receive bachelor’s or master’s degrees. Regional surveys conducted in California (VanDerwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018) and the southeastern United States (Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody, Wright and Dekle2018) on gender-based experiences in archaeology had respondent pools not strictly limited to those with PhDs. In each of these surveys, women made up larger proportions of respondents, including 60.6% and 65%, respectively. These numbers match well with recent findings of PhD attainment rates for women. However, women are also more likely to be earning less than $60,000 and occupy lower ranks in academia and private CRM firms (Vanderwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018:Table 5, Figure 3). These factors could both impede women’s access to the SAA annual meetings. Heath-Stout (Reference Heath-Stout2024:6) also points out that most women who have joined the discipline over the last few decades are straight, cisgender, and white. Progress on gender parity can thus overshadow concerns for greater diversity in terms of race, sexuality, and class, among other axes of identities. It is thus even more difficult to determine whether conference participation matches archaeology’s overall demographics, which themselves remain problematically narrow (see Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024:Table 1.1).

Self-Selected Leadership Roles

Although the majority of participants at every SAA annual meeting are classified as presenters, as noted earlier, there are also multiple leadership roles that individuals can choose for themselves. These include organizing a symposium or poster symposium and being its chair or organizing a forum or lightning round and being its moderator. Over the 23 years of annual meetings in our sample, 47% of self-selected leaders were women, and 53% were men. This distribution is nearly identical to women and men’s participation in the SAA overall, regardless of session format or role (48% women and 52% men).

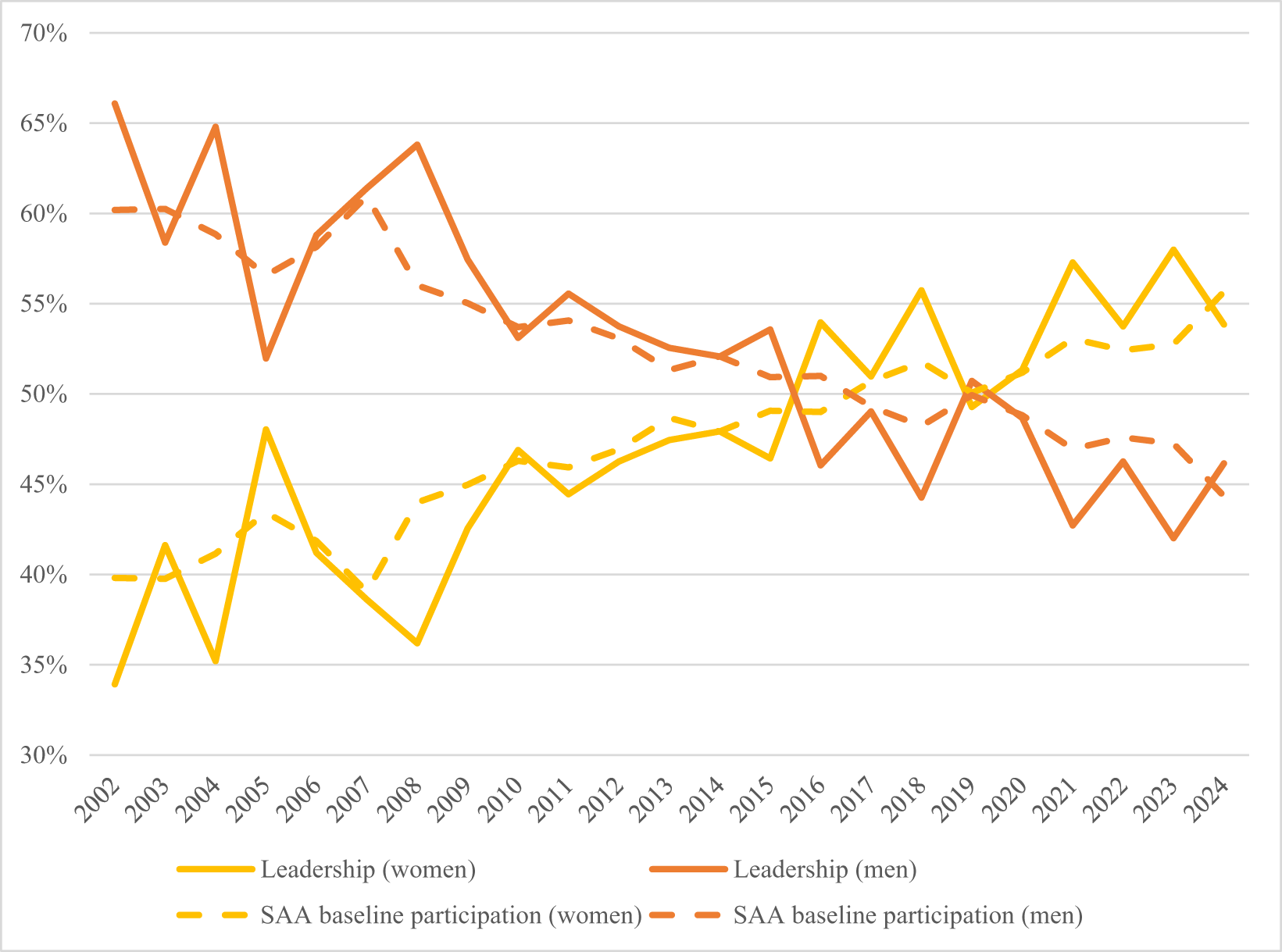

Over time, women’s representation in leadership roles ranged from 34% (2002) to 58% (2023; see Figure 2). When broken down by year, for nine of the 23 years in our sample, women were overrepresented in leadership roles compared to their overall representation in the SAA in the corresponding year. For example, in 2016, women comprised 54% of leaders compared to their overall participation in the conference at 49% that year. For 11 of the 23 years, women underselected leadership roles for themselves, and in three of the 23 years their leadership participation matched their overall participation in the SAA. In general, women’s representation in leadership roles has increased over time along with their increasing representation in the conference, and men’s has decreased over time alongside their corresponding decrease in participation relative to that of women (see Figure 2). These data suggest that broadly speaking, over time, women and men were similarly likely to choose leadership roles for themselves. However, greater nuance becomes evident when these data are positioned alongside data regarding invited roles.

Figure 2. Self-selected leadership annual data. Solid yellow line: percentage of women in self-selected leadership roles. Dashed yellow line: baseline of participation of women in the SAA overall meeting. Solid orange line: percentage men in self-selected leadership roles. Dashed orange line: baseline of participation of men in the SAA overall meeting.

Invited Roles

Chairs and moderators are positioned to invite presenters and discussants in symposia, poster symposia, forums, and lightning rounds. In selecting whom to ask to fill these roles, chairs may draw on their established social networks (see Leighton Reference Leighton2020), inviting individuals they know personally, individuals well known for related work, or both. Invited discussants are often seen as “experts” on the theme by the session chair or moderator. Inviting presenters and discussants provides important opportunities for organizers to network within the field, establish social relationships, and potentially set expectations for future reciprocity.

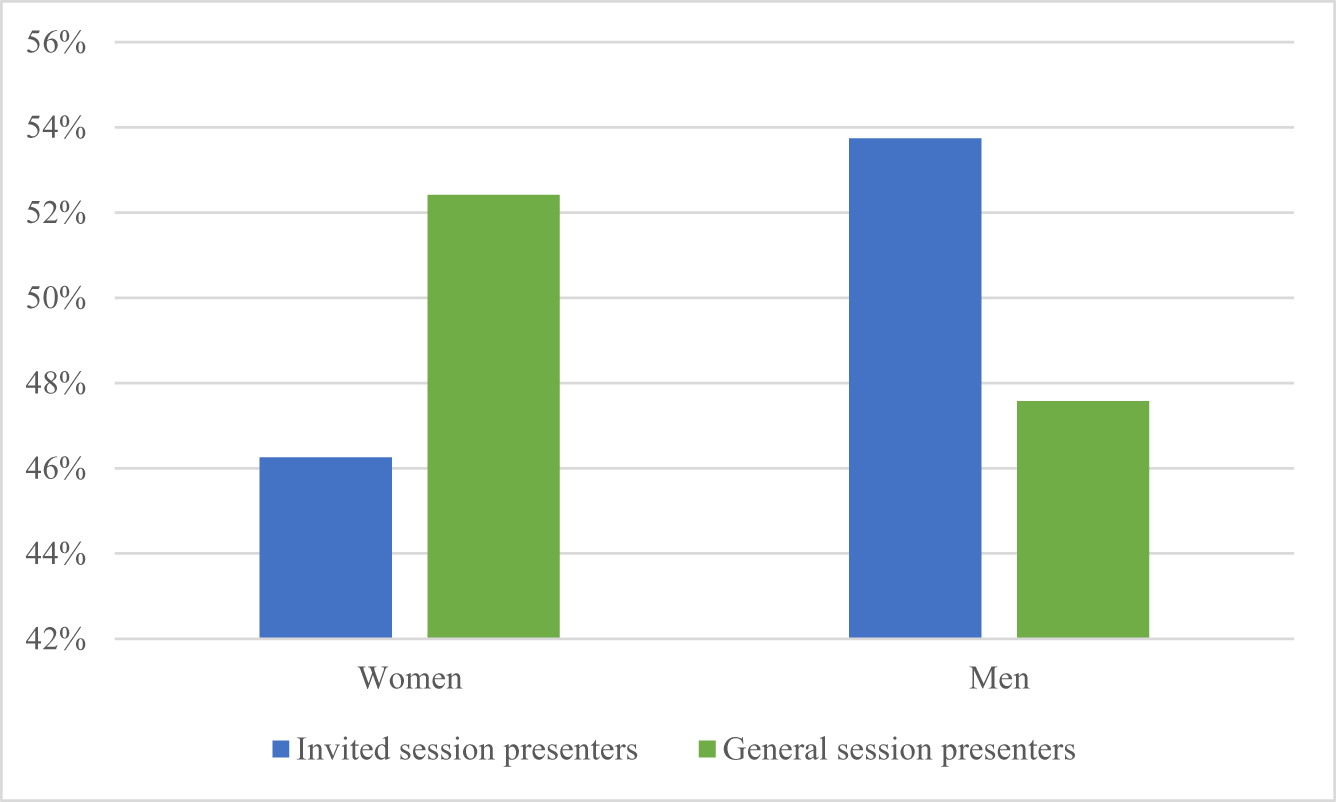

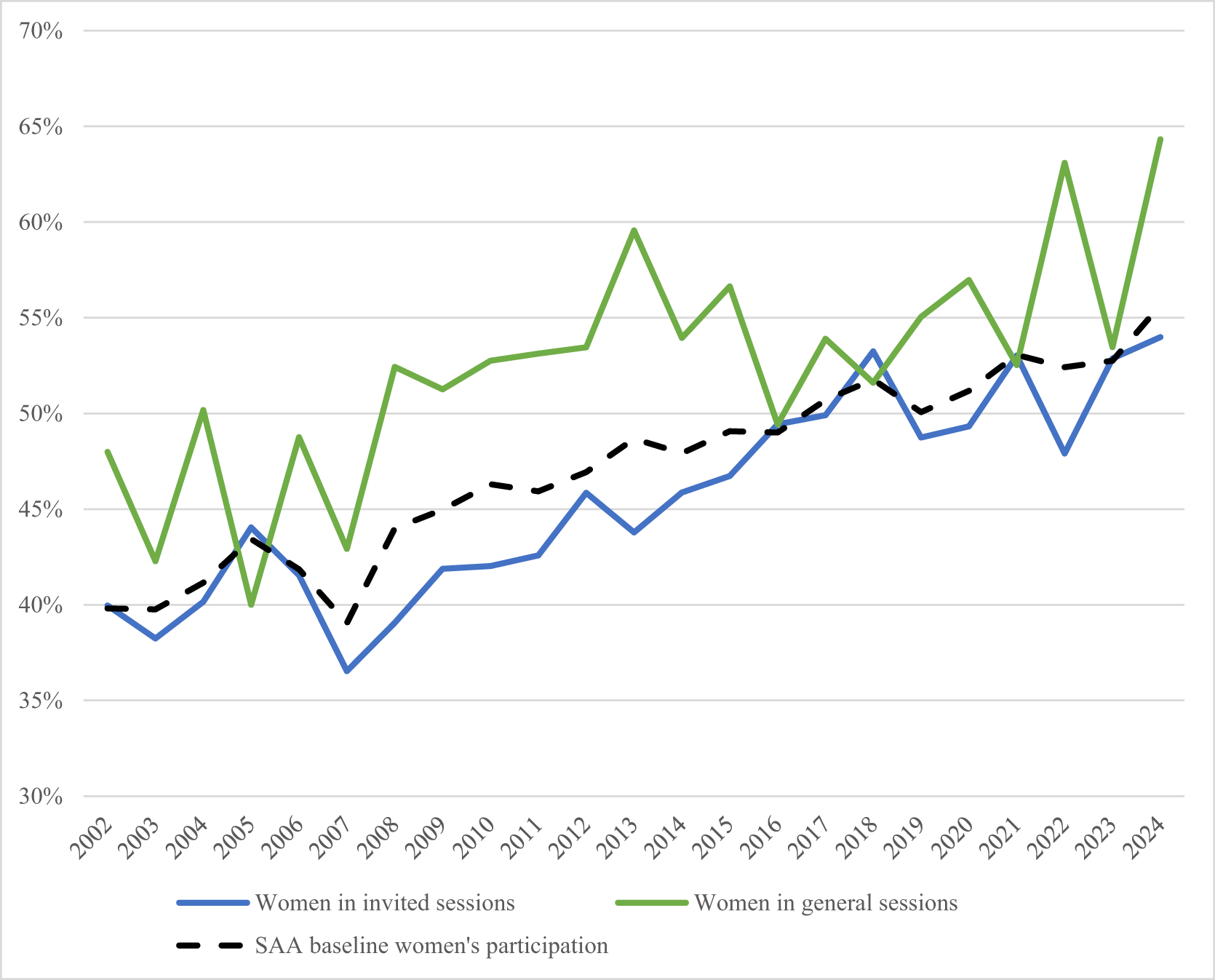

When we compare presenters in invited sessions (symposia and poster symposia) and general sessions (general sessions and poster sessions), gender-based patterns emerge. Over the 23 sample years, women made up 46% of presenters in invited sessions, whereas 54% were men (χ2 = 156.40, df = 2, p < 0.0001)). By comparison, presenters in general sessions were 52% women and 48% men (Figure 3). Women presenters were therefore slightly overrepresented in general sessions relative to invited sessions, as well as slightly underrepresented in invited sessions relative to their overall participation in the SAA. When this metric is broken down by year and compared to overall participation in the SAA for each corresponding year, the pattern persists (Figure 4). Between 2002 and 2024, women were underrepresented in invited sessions for 17 of 23 years, ranging from 1% to 5% representation below their overall conference participation for the corresponding year (χ2 = 172.41, df = 44, p < 0.0001). For five of 23 years, their participation in invited sessions matched their participation in the meeting overall, and for one year it exceeded it by 1%. The reverse is true for general sessions: women were overrepresented in general sessions for 18 of 23 years, ranging from 2% to 11% representation above their overall conference participation for the corresponding year. In four of 23 years, participation in general sessions and the overall meeting matched, and for one year, women were underrepresented (by 3%) in general sessions. These data indicate that women were consistently underinvited to participate in the more prestigious invited sessions.

Figure 3. Women and men as presenters in invited sessions versus general sessions.

Figure 4. Yearly rate of women presenters in invited sessions (blue) versus general sessions (green), relative to their overall participation in the annual meeting (black dashed).

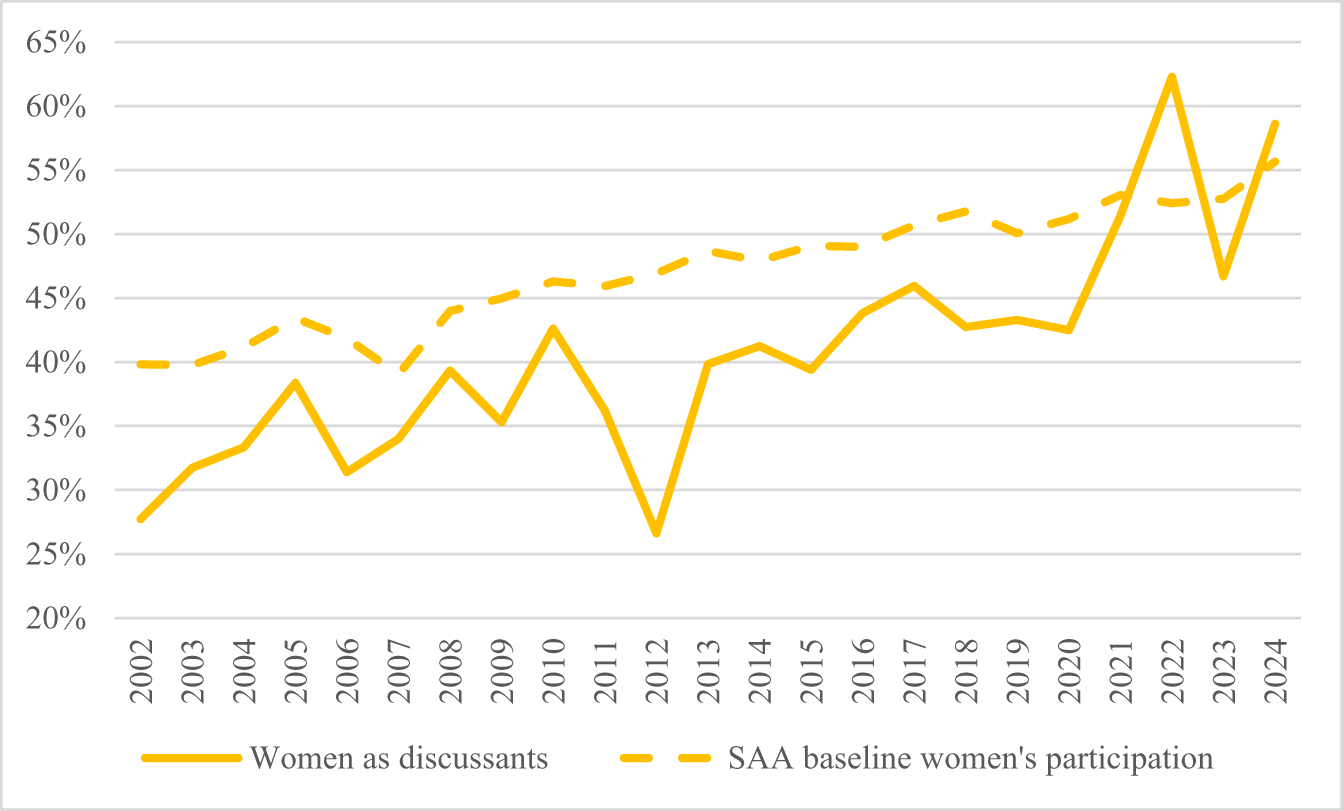

The role of discussant is an invited one in symposia, forums, and lightning rounds. Discussants across these sessions over the 23 years in our sample were 42% women and 58% men. Women, therefore, were invited to be discussants less frequently than men, and underinvited relative to their participation in the SAA (48%). This disparity is especially strong in symposia, in which women only made up 33% of discussants relative to 67% men (χ2 = 111.26, df = 4, p < 0.0001).Footnote 7 When these data are broken down by year, it is clear that women were almost always underrepresented in the role of discussant in symposia, forums, and lightning rounds (Figure 5). Between 2002 and 2024, in all years except two, women were discussants at lower rates than their participation in the conference overall (ranging from 2% to 20% lower). The two exceptions both occurred since 2020, suggesting potential improvement over time that may be due to the increasing success of women in the profession. Thus, women seem to have consistently been invited to fill the role of discussant at rates lower than their participation in the conference, and at rates much lower (as much as 47% less) than their male colleagues.Footnote 8

Figure 5. Women as discussants in symposia, forums, and lightning rounds compared to their overall participation in the conference.

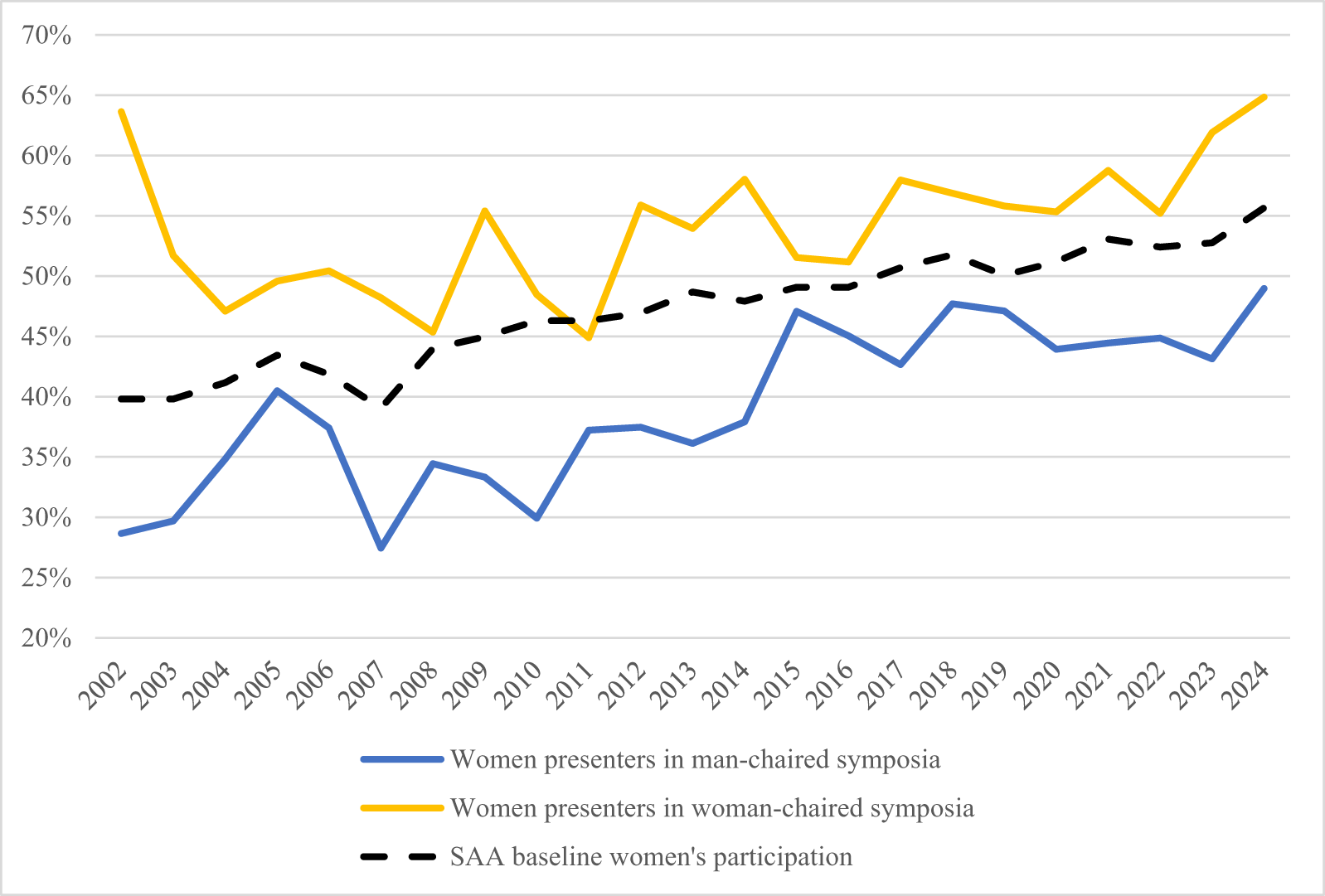

As at other disciplines’ conferences (e.g., Isbell et al. Reference Isbell, Young and Harcourt2012; Nittrouer et al. Reference Nittrouer, Hebl, Ashburn-Nardo, Trump-Steele, Lane and Valian2018; Zaza et al. Reference Zaza, Ofshteyn, Martinez-Quinones, Sakran and Stein2021), the gender identity of the session organizer dramatically affected the gender identity of the participants at the SAA annual meeting. When symposia were solo-chaired by women between 2002 and 2024, 54% of presenters and 38% of discussants they invited were women.Footnote 9 In contrast, when symposia were solo-chaired by men, 39% of presenters and only 28% of discussants were women (Table 2: presenters—χ2 = 214.54, df = 2, p < 0.0001; discussants—χ2 = 10.64, df = 2, p = 0.0049). Therefore, when men chair symposia, they consistently underinvite women relative to men. Women do this to a degree as well. When women chair a symposium, they invite a more equal representation of women and men as presenters but still underinvite women as discussants. Archaeologists thus do not credit women as experts at the same rate as they do men, regardless of their own gender identity. Such a finding is not uncommon; studies in other disciplines have shown similar results (e.g., Moss-Racusin et al. Reference Moss-Racusin, Dovidio, Brescoll, Graham and Handelsman2012).

Table 2. Women and Men in Roles as Presenters and Discussants When Men versus Women Chair Symposia.

Not only do both men and women symposia organizers seem to perceive men as experts to a higher degree than they do women, but an organizer may also feel that failure to include those perceived experts in their symposium might reduce the visible prestige of the symposium itself. In other words, the power imbalance is legible to all: symposia organizers understand that including those of perceived greater expertise (in this case, more often men) elevates the status of their symposium through name recognition by other attendees. This creates an accumulation effect over time, wherein the proclivity to assume that men are greater experts than women results in invitations being extended more frequently to men, elevating their visibility and prestige and thereby increasing the likelihood that they will be invited to fill prestigious roles again.

Patterns in the gender identities of session inviters and invitees can further be broken down by year.Footnote 10 In general, from 2002 to 2024, the representation of women presenters in symposia increased over time, regardless of whether the session was chaired by a man or a woman. However, in every year, representation of women presenters was higher in woman-chaired symposia than in male-chaired symposia. These data can also be compared to the baseline of yearly participation in the annual meeting (Figure 6). When men chaired symposia, women presenters were always underrepresented relative to their participation in the SAA in the corresponding year. By contrast, in symposia chaired by women, women presenters were almost always—with only one exception (2011)—slightly overrepresented in symposia compared to their representation in the overall SAA. When women solo-chaired symposia, women presenters were overrepresented at an average of 7% above their baseline participation in the conference. When men solo-chaired, women presenters were underrepresented at an average of 8% lower than their participation in the conference. Considering that a greater proportion of solo-chaired symposia are chaired by men (54%) than women (46%), these effects are multiply compounded. Although there is a clear preference among chairs to invite presenters who align with their gender identity (“homophily”), men do so to a higher degree than women, a pattern that is exacerbated by the overall underrepresentation of women in the SAA over the past several decades.

Figure 6. Women presenters in symposia chaired by men versus women, compared to the SAA baseline of women participation.

Articulations between Invitedness and Self-Selected Leadership

When these data and patterns are situated relative to one another and to a “historic” moment in the history of SAA annual meetings, an additional pattern emerges. At the 2017 SAA conference, women surpassed men for the first time in representation at the conference overall (51% women, 49% men), and their numbers have continued to grow. Prior to this moment, women were less likely to fill leadership roles: in 60% of the years before 2017, they filled leadership roles at rates lower than their participation in the conference. After 2017, women were more likely to fill leadership roles: in 75% of years after 2017, they filled roles at rates of parity or higher than their participation in the conference. Thus, as women have become increasingly better represented in the SAA, they have also taken on more than their share of leadership and service roles.

When invitedness is examined in the same way, the results differ. In 73% of the years before 2017, women were underrepresented in invited roles relative to their representation in the conference in those years. After 2017, their representation in invited roles, unlike in self-selected leadership roles, did not catch up: women remained predominantly underrepresented in invited roles. In 63% of years after 2017, they were represented at rates lower than their representation in the conference that year. In symposia solo-chaired by men, women were always—both before and after 2017—represented in invited roles at rates lower than their overall participation in the conference.

In other words, until 2016, women underselected themselves into leadership roles, and they were underinvited into invited roles. After the inflection point of 2017, when women’s representation reached and has continued to surpass parity in the conference overall, women self-selected into leadership roles more regularly while still being underinvited into invited roles, especially by their male colleagues. Thus, most of the name recognition and prestige that women have been building through their participation in the SAA has come more from their own initiative than from being elevated by their peers.

Not necessarily mutually exclusive with this explanation, engagement in self-selected leadership roles can also be considered through the lens of service. Although organizing a session can provide name recognition and opportunities for relationship building with other scholars, it is also in many ways a service role—requiring the issuing of invitations, sending emails, coordinating logistics, sometimes arranging a meal, and so on. As women became increasingly represented in the SAA, especially after 2017, they took on more than their share of leadership and service roles. As discussed later, other scholars have noted that women in academia perform on average more service work than men (Guarino and Borden Reference Guarino and Borden2017; Monroe et al. Reference Monroe, Ozyurt, Wrigley and Alexander2008:220–221). Women’s increased representation in self-selected leadership roles over time and their perpetual underrepresentation in invited roles may thus be influenced by multiple factors. Although women may in general be more willing to fill service roles, they may also pursue self-selected leadership roles to gain their own name recognition and prestige precisely because they are not being brought into invited positions by their colleagues at appropriate rates.

Discussion

This analysis of more than two decades of participation in SAA annual meetings reveals several insights. At a basic level, despite women’s increasing representation in both the field of archaeology and the SAA annual meeting, women continue to be underrepresented at the discipline’s flagship conference. It was not until 2017 that women attained parity in participation. Their highest representation between 2002 and 2024 was 56% (in 2024), yet according to doctoral degrees awarded, their representation should have been between 60% and 64% (Cramb et al. Reference Cramb, Ritchison, Hadden, Zhang, Alarcon-Tinajero and Xianyan Chen2022; Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Johnson, Price, Record, Rodriguez, Snow and Stocking2023; Speakman et al. Reference Speakman, Hadden, Colvin, Justin Cramb, Jones and Lulewicz2018).

Further, although women and men are in general similarly likely to fill self-selected leadership roles, women are less frequently asked to fill invited roles by their peers, perhaps reflecting differential gender-based notions of expertise. In particular, the gender of the inviters influences the gender of the invitees. Women slightly overinvite and men slightly underinvite women presenters to participate in organized symposia, an issue that is compounded by the fact that men are more likely to chair symposia in the first place. However, both men and women session chairs underinvite women as discussants, and men dramatically so. These patterns suggest that women consistently receive less credit and recognition for their expertise than do their men peers and that men are more likely than women to withhold this recognition.

Such findings are consistent with other studies demonstrating that men and women experience academia in dissimilar manners. For example, faculty members of different gender identities often experience academic field research differently (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017; see also Moser Reference Moser2007) and are frequently assigned different types and amounts of labor (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez2018; O’Meara et al. Reference O’Meara, Kuvaeva, Nyunt, Waugaman and Jackson2017). On average, women faculty perform significantly more service work than men faculty (Guarino and Borden Reference Guarino and Borden2017; Monroe et al. Reference Monroe, Ozyurt, Wrigley and Alexander2008:220–221). More specifically, O’Meara and colleagues (Reference O’Meara, Kuvaeva, Nyunt, Waugaman and Jackson2017:1176) noted, “Women received more requests to be engaged in teaching, student advising, and professional service than men.” Our study similarly suggests that men are more often invited by their peers to fill the most prestigious roles in academic conferences. As Joan Gero (Reference Gero, Bond and Gilliam1994:151) recognized more than three decades ago, “what is intolerable [about this situation] is the recognition that a sexual division of labour is actually a hierarchy of labor.”

Although these patterns are significant, the lack of access to intersectional data undoubtedly obscures important distinctions in women’s experiences at conferences (Sanchez et al. Reference Sanchez, Hypolite, Newman and Cole2019). As noted earlier, improvements in gender equity are largely confined to women not otherwise “othered” (sensu Cobb and Crellin Reference Cobb and Crellin2022). Just as we see homophily in gendered invitations to conference sessions, we suspect that a tendency to seek out those similar to oneself also occurs across other axes of identity. Given that most women in archaeology are white, straight, and cisgender (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024:6, Table 1.1), it is reasonable to assume that the majority of both women organizers and women invited speakers in symposia fit those categories as well.

Other than women’s participation in the SAA annual meeting increasing in proportion to their greater representation in archaeology overall, frustratingly little has changed in the 25 years since Burkholder’s (Reference Burkholder2006) analysis of the 2000 conference. Now, as before, women’s representation in leadership roles continues to increase largely due to “their own initiative or that of other women” (Burkholder Reference Burkholder2006:30), and the representation of women in prestige roles continues to lag significantly behind that of men. Further, the trends outlined here are not unique to archaeology. As previously mentioned, researchers in several disciplines have documented similar patterns, particularly regarding gender-based notions of competency and expertise (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Fanson, Lanfear, Symonds and Higgie2014; Roberts and Verhoef Reference Roberts and Verhoef2016) and the effect of session organizers’ identities on the identities of the invitees (e.g., Casadevall and Handelsman Reference Casadevall and Handelsman2014; Isbell et al. Reference Isbell, Young and Harcourt2012; Nittrouer et al. Reference Nittrouer, Hebl, Ashburn-Nardo, Trump-Steele, Lane and Valian2018; Sardelis and Drew Reference Sardelis and Drew2016; Zaza et al. Reference Zaza, Ofshteyn, Martinez-Quinones, Sakran and Stein2021).

Multiple factors likely contribute to continuing gender-based inequalities in conference participation across disciplines and through time. First, traditional gender-based family roles and care obligations often fall to women (Vega Varela and Moridi Reference Vega Varela and Leyly2024), which can make conference attendance and participation tricky to negotiate. Academic conferences are increasingly offering childcare, but availability is often limited, and the financial barrier of traveling with an additional person remains. Second, not all jobs provide equal access to travel and conference funds. Well-resourced institutions and individuals holding prominent positions within them receive greater support to attend conferences. Further, academics with high research workloads often receive more travel funding and generate more capital from conference participation. As noted by the SAA Task Force on Gender Disparities in Archaeological Grant Submissions (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Mills, Herr, Burkholder, Aiello and Thornton2018), women may be underrepresented in research-intensive academic positions relative to the rate at which they obtain PhDs (see also Hutson et al. Reference Hutson, Castro and Teruel2025). Women also continue to be underrepresented at the highest levels of employment and higher income brackets in both academic and private CRM settings (Vanderwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018:Table 5, Figure 3). In addition, women experience harassment and assault far too often in archaeology, which can lead to greater insecurity and less desire to remain in the field or attend conferences (Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody, Wright and Dekle2018). Taken together, men are often in positions most likely to be encouraged and rewarded for conference participation. Third, and quite simply, one is more likely to attend a conference to which one has been invited. When deciding whether to attend a conference (and considering its financial and logistical costs), incentives to attend are meaningful. The prestige of participating in an invited session undoubtedly alters the calculation of cost and encourages attendance.

Finally, many—particularly, “unburdened” archaeologists with fewer personal experiences of exclusion (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024)—may not recognize the effects of acknowledging or omitting colleagues through conference session invitations. Given the seemingly low stakes of a single presentation, organizers may be unaware of their roles in distributing economic, cultural, and social capital. For the 2003 SAA Member Needs Assessment Survey, respondents were asked the following question: “In your experience, how common is inequity in invitations to symposia, workshops, etc.?” Of the women who responded, 34% said such inequity was “common / very common,” whereas 29% thought it was “rare / very rare.” In contrast, only 6% of men indicated that inequity was “common / very common,” whereas 54% thought it was “rare / very rare” (Baxter Reference Baxter2005:7). Individuals may thus be unaware of exclusions that do not affect them personally.

Suggested Interventions

Both SAA members and organizational leaders should take steps to ameliorate gender-based inequities in conference involvement and increase women’s representation in invited roles. At a basic level, symposium, lightning round, and forum organizers should recognize the importance of conference invitations and the problematic tendency for those invitations to be based on principles of homophily, rather than achievement. They should also recognize, as do Williams (Reference Williams2023) and Smith and Garrett-Scott (Reference Smith and Garrett-Scott2021), the problematic tendency for session organizers to extend invitations to members of multiply marginalized groups, particularly women of color, to present on topics that emphasize their identities, rather than their scholarship. Organizers should strive, at a minimum, for gender parity in their sessions or, more appropriately, representation that reflects the current makeup of the field. Symposia discussants in particular need to better reflect the demographics of the discipline.

Participants in invited sessions can also effect change. They can inquire about the diversity of session participants and suggest scholars with appropriate expertise to help ensure greater representation. If organizers are unwilling to reconsider the importance of diverse voices, participants in invited sessions can refuse to participate. Doing so, however, may have disproportionate costs for early-career or marginalized archaeologists compared to senior archaeologists. Critically, the burden to initiate change should not fall only on women, people of color, and those of other marginalized identities. As Burkholder noted, “A lesson for men is that their women colleagues and students need their continued support if we are to create a more equitable playing field” (Reference Burkholder2006:30). Equally critically, straight, white, cisgender women, who are increasingly well represented in archaeology, must also leverage their privilege to support multiply marginalized individuals.

Going beyond individual interventions, the SAA itself can also take actions to improve equity at its annual meeting by continuing to help dismantle financial and logistical barriers preventing individuals from attending. The SAA has taken critical steps in this direction in recent years through the institution of a Code of Conduct and the SAA Meeting Safety Policy, provision of childcare, and providing travel awards and meeting access grants. Additional efforts could be made to better publicize these opportunities. The Collaboration e-Community—an online discussion forum helping session organizers find interested presenters and presenters to find relevant sessions—is also important in lessening the effect of homophily on session invitations and could be made more prominent and easier to access. Additionally, the SAA could make clear its equity expectations through statements on its website, in the meeting program, and elsewhere and explicitly encourage organizers to compile diverse and well-represented participant rosters. More specifically, we suggest that the SAA adopt and promote the three guiding principles of the NSF-funded Alliance to Catalyze Change for Equity in STEM Success (ACCESS): “Science quality and diversity are not mutually exclusive. . . . Avoid statistical excuses for noninclusive practices . . . [and] recognize that epistemic exclusion exists in science” (Segarra et al. Reference Segarra, Primus, Unguez, Edwards, Etson, Flores and Fry2020:2496).

Further, rather than simply issuing a general call for submissions, the SAA could seek out, support, and actively invite exceptional scholars with multiple marginalized identities to organize sessions and present on topics in their area of expertise. Other organizations, such as the nonprofit TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design), both accept applications from interested potential speakers and actively solicit speakers who may be unlikely to apply themselves. Following the lead of other organizations, the SAA could also collect and share voluntary demographic data about presenters (see also Brodkin et al. Reference Brodkin, Morgen and Hutchinson2011). Indeed, several “societies are now moving toward a model in which annual meeting abstract submission will ask presenting authors to disclose demographic information” (Segarra et al. Reference Segarra, Primus, Unguez, Edwards, Etson, Flores and Fry2020:2497). If Heath-Stout’s (Reference Heath-Stout2020a, Reference Heath-Stout2020b) recent work regarding peer review and publication is any indication, intersectional identities will also undoubtedly affect conference participation and particularly invitedness to organized sessions. Such effects, however, are difficult to assess and combat without data.

Conclusion

This study makes clear that gender plays a strong role in determining who ends up in positions of prestige at the SAA annual meeting and that decisions about who is “qualified” to fill certain roles, particularly discussant roles, are influenced by gender-specific notions of expertise. Women continue to be underrepresented at the annual meeting overall relative to their representation in the profession, but especially so in invited roles. We suggest this disparity is attributable, at least in part, to inaccurate and harmful notions of the qualifications, abilities, and expertise of men versus women. As found in a 2012 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, science faculty from research-intensive institutions asked to review student application materials “rated the male applicant as significantly more competent and hireable than the (identical) female applicant” (Moss-Racusin et al. Reference Moss-Racusin, Dovidio, Brescoll, Graham and Handelsman2012:16474). Importantly, although women continue to create more opportunities for other women, as found by Burkholder (Reference Burkholder2006) two decades ago, both men and women exhibit some degree of gender bias, and progress in overall gender representation may conceal a distinct lack of meaningful progress on making the discipline more holistically inclusive (see Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024).

Most studies about the unequal representation of women in science invoke the leaky pipeline metaphor: the idea that women passively drip out of academia at various stages of their careers, often because of historically unequal practices that have been ameliorated yet still influence the present (see Kurnick and Fladd Reference Kurnick and Fladd2026). A leaky pipeline metaphor may initially seem to explain the decreasing number of women invited to participate in organized sessions and the even smaller number of women invited to fill the most prestigious role of discussant. One could argue, for example, that few interventions are needed because there will be more women discussants over time as more women archaeologists become full or emeritus professors. Yet, as Allen and Castleman (Reference Allen, Castleman, Brooks and Mackinnon2001:156) note, the leaky pipeline metaphor is problematic, in part, because of “its failure to acknowledge the complexities of male advantage, gender power, and the gendered nature of organizational dynamics.” Indeed, in our study, such a perspective fails to acknowledge the significant effect of session organizers’ identities on the identities of session invitees. Contemporary inequality in archaeological practice is thus more than merely the legacy of historical practices. The lack of equity in conference participation may be better understood as a form of current and active—although likely unintentional and unconscious—gatekeeping, rather than passive and normal “leaking.”

The practices that lead to such gatekeeping, and specifically the rationale for invitedness, can thus be questioned and ultimately modified. An important step is an increased recognition that decisions perceived as inconsequential in fact represent the distribution of capital within archaeology. Once the consequences of inclusion and exclusion are outlined more explicitly, session organizers and presenters can be encouraged to make small changes that will, we hope, have big consequences. As Segarra and colleagues (Reference Segarra, Primus, Unguez, Edwards, Etson, Flores and Fry2020:2495) argue, “An accumulating body of evidence indicates that . . . the most effective and innovative science is performed by teams composed of individuals from different backgrounds, including diversity of gender, race, ethnicity, and career stage” (see also Vallence et al. Reference Vallence, Hinder and Fujiyama2019). The SAA annual meeting offers a venue to reconsider the distribution of capital within the discipline, thus enriching archaeology as a whole.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the many mentors, especially women, who have uplifted us and helped shape our careers. Sarah Coronna and Nora Downing assisted with data entry, and Nanda Grow provided statistical consultation and advice. We are grateful to three anonymous reviewers for their feedback.

Funding Statement

Funding from the University of Colorado Boulder Thrive Grant assisted with a portion of the data collection for the research presented here.

Data Availability Statement

All SAA programs from which data were derived for this article are available at https://www.saa.org/annual-meeting/programs/program-archives.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2025.10129.

Supplementary Material 1. Table of variables recorded in data collection.

Supplementary Material 2. Table of participant roles by session format at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology.