Middle-income countries face the challenge of industrial upgrading amidst two significant forces: global production fragmentation and domestic decentralization. Notably, industrial policy has expanded since 2010 after several decades of criticism.Footnote 1 While states at the national level still play a prominent role in designing and funding upgrading efforts, policy implementation and its results increasingly depend on subnational dynamics between local stakeholders and international actors. This paper tackles the following questions: Under what conditions are subnational units more likely to embrace national industrial upgrading policies? More specifically, how do local political economy coalitions of firms and governments shape national industrial policy implementation and use it as leverage to upgrade?

Since the 1990s, middle-income countries like Mexico have undertaken thorough decentralization measures, generating new policy-making settings with various actors and goals. Decentralization has also made implementing national-level programs more complex because subnational units have the leeway to decide whether to support federal plans (Eaton Reference Eaton2017; Niedzwiecki Reference Niedzwiecki2018; Samford Reference Samford2022). This is the case with Prosoft, launched by the Mexican Ministry of Economy (MoE) in 2004 to boost the IT sector across Mexican states. Subnational governments could opt-in, and most did, albeit with varying levels of commitment. The program provided cash grants covering 50 percent of total project costs, with the firm covering the remaining 50 percent or splitting it into 25 percent each if the subnational state agreed to allocate resources for the strategy. Subnational governments also acted as intermediaries, through the regional ministries of economy, firms submitted their proposals. Each state was responsible for evaluating and approving projects.Footnote 2 Funding could cover training and certification, software and equipment, R&D, technology transfer and royalties, supplier development, and tailor-made university programs. By 2008, 23 out of 32 states had opted into Prosoft, but funding levels and outcomes varied widely.Footnote 3 Prosoft did not target a specific stage in the software GVC, instead, firms, depending on their goals decided whether they wanted to focus on activities related to higher-value-added like R&D or on lower-value-added tasks like helpdesk and support.

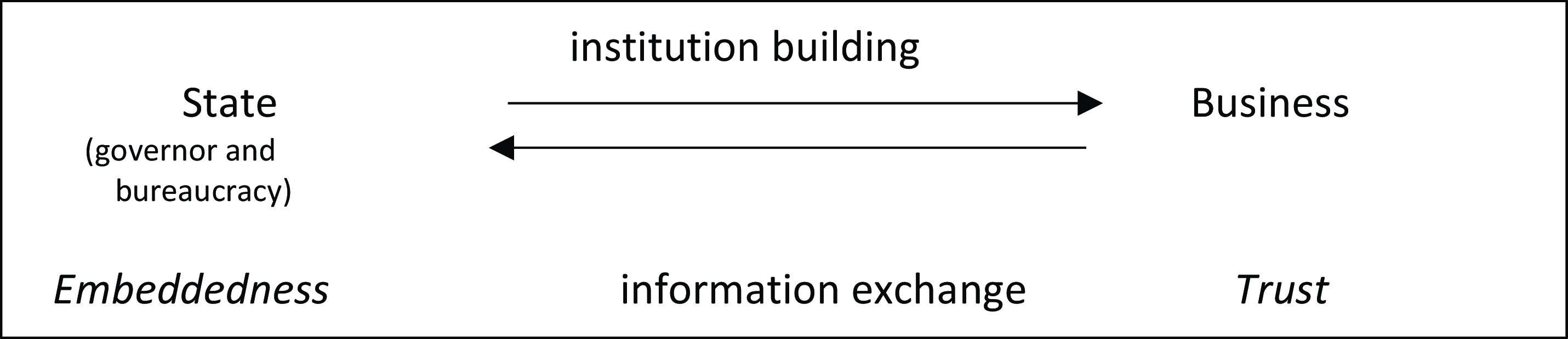

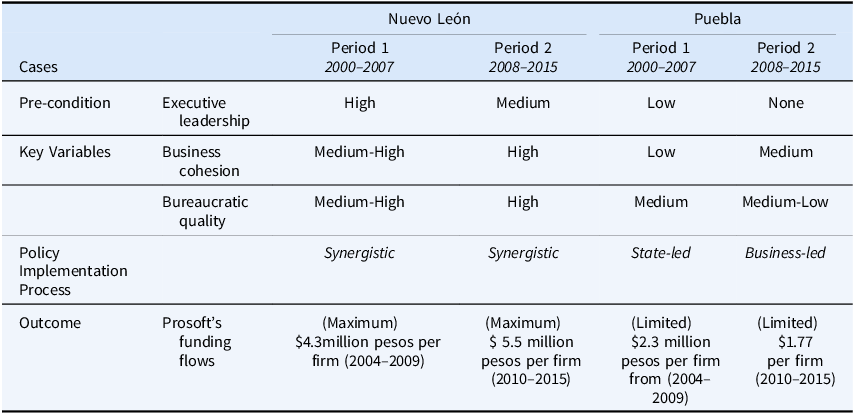

This paper presents a theory to explain industrial policy implementation which is tested and refined through a most-similar case comparison of Prosoft in two Mexican states: Nuevo León and Puebla. When Prosoft launched, these two states had similar levels of innovation potential, both ranking high, Nuevo León in 3rd place and Puebla in 6th place.Footnote 4 Puebla even outpaced Nuevo León in the number of universities offering IT systems (45 vs 13) and researchers (455 vs 303) and had similar numbers of students enrolled in computer and systems programs (9,000). Nonetheless, the total amount of funds each state attracted from Prosoft differed substantially. Nuevo León secured MX$4.3 million per firm from 2004 to 2009, while Puebla attracted only MX$2.3 million per firm. By 2015, the difference widened further; Nuevo León received MX$5.5 million per firm compared to Puebla’s MX$1.7 million.Footnote 5 The analysis shows that despite having initial innovation capabilities that offered perfect conditions for industry development in both states, their governments and business communities embraced Prosoft with very different patterns, leading to divergent outcomes.

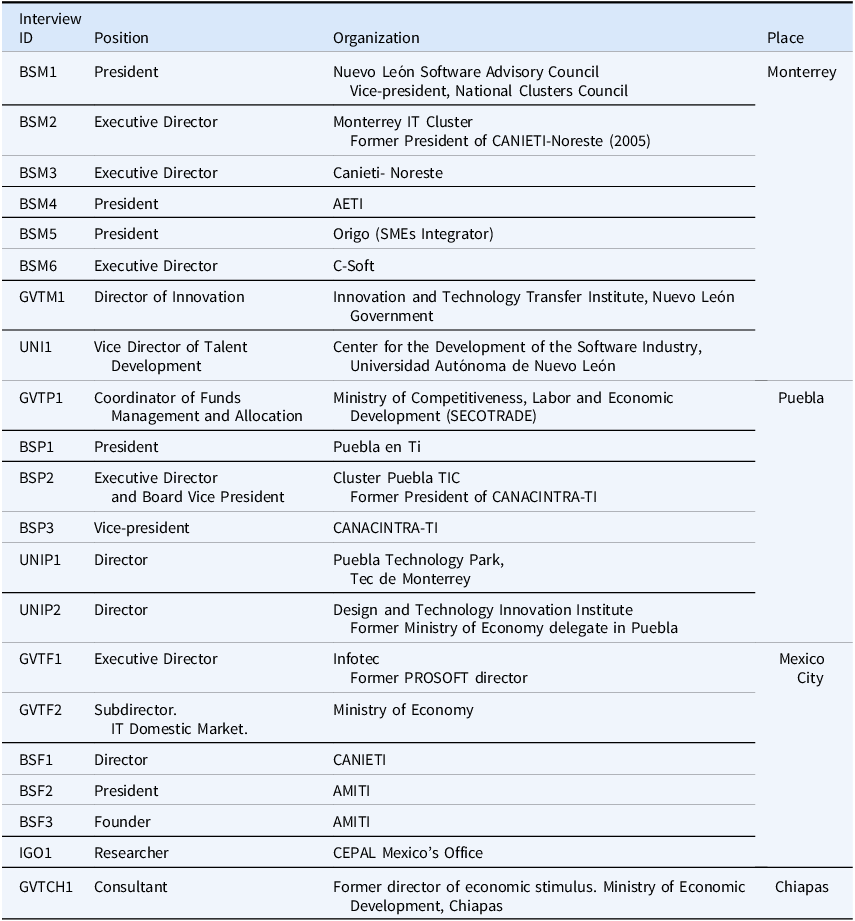

By dividing the cases into two periods, the analysis also process-traces how variables in the model impact industrial upgrading policy from 2000 to 2015. The information comes from twenty semi-structured interviews with key actors in Monterrey, Puebla, and Mexico City, as well as secondary sources such as official economic development plans, program presentations, organizations’ websites, and local newspapers.Footnote 6

This paper refines the current understanding of industrial upgrading in the context of Global Value Chains (GVCs). It challenges the predominant focus on national industrial policies found in most Middle-Income Trap (MIT) literature, which often assumes uniform policy implementation.Footnote 7 Instead, the analysis shows how state actors and firms shape program deployment at the subnational level. Thus, it adds to the study of regional industrial policy strategies which are still in their infancy (Bulfone Reference Bulfone2023, 35). Moving beyond the traditional attention to manufacturing which prevails in MIT analyses, this paper highlights the services sector which has become increasingly essential but remains understudied since Evan’s (Reference Evans1995) seminal analysis of the IT sector in Kerala. It also reveals that the institutionalization of public-private coordination spaces contributes to sustaining subnational industrial policies over time beyond the initial conditions that promoted them.Footnote 8

The paper is organized into six sections. Section one reviews the literature and introduces the theory of industrial upgrading policy processes. Section two explains the methods and case selection criteria. Section three examines the case of Nuevo León, and section four analyzes the case of Puebla. Section five compares the two cases and considers alternative explanations. Section six presents the conclusions.

Business-state relations and industrial upgrading policy

A vast literature on industrial upgrading policies explores the different levels and actors involved in policy design and implementation processes. First, developmental state, varieties of capitalism, and middle-income trap scholarship primarily focus on the national level. While developmental state literature underscores the state’s role and its “embedded autonomy” as critical for successful industrial policy, middle-income trap literature focuses on how national business-state coalitions shape the prospects of upgrading. Second, there is a rich collection of studies considering the role of political variables in industrial policy at the subnational level. These studies mainly center on the state, with cases from the agriculture and manufacturing sectors. They examine state-business interactions from the public sector side, leaving the business side undertheorized. I argue that private sector configuration is critical in adopting and implementing industrial policies. Thus, at the end of this section, I propose a theory that considers industrial policy implementation as a process shaped by government and business capacities at the subnational level.

National-level analyses of industrial policy

Developmental state authors have revealed how purposeful state action stimulates industrialization mainly at the national level. Evans’s (Reference Evans1995) seminal work demonstrates that with “embedded autonomy”, the state can facilitate the structural transformation of businesses and promote the emergence of new productive activities. He even explored the subnational dimension through the case study of Kerala in India. Meanwhile, neo-developmental state authors offer insights into the emergence of high-tech industries through the creation of specialized, flexible agencies in small countries (Breznitz, Reference Breznitz2007; O’Riain, Reference O’Riain2004). While these contributions are valuable, they leave room for further analysis of subnational-level industrial policy in developing economies within the context of GVCs.

Placing firms at the center, the varieties of capitalism literature highlight the relevance of firms and their associations in upgrading, generating vocational training, and conducting research and development through institution building in countries and regions of advanced economies (Busemeyer Reference Busemeyer2012; Busemeyer, Carstensen & Emmenegger Reference Busemeyer, Carstensen and Emmenegger2022; Crouch, Colin and Voelzkow Reference Crouch, Colin and Voelzkow2009; Culpepper Reference Culpepper2003; Thelen Reference Thelen2004). However, fewer studies have examined how business associations shape and are shaped by industrial upgrading policy processes in subnational regions of developing countries (Doner and Schneider Reference Doner and Schneider2016; Fuentes and Pipkin Reference Fuentes and Pipkin2023; Kahn Reference Kahn2019; Madariaga and Rangel-Padilla Reference Madariaga and Rangel-Padilla2025).Footnote 9 Recent middle-income trap analyses concentrate on the national level.Footnote 10 A central explanation for upgrading failure is that national production systems in Latin America and Eastern Europe constitute hierarchical market economies or dependent market economies characterized by an overall lack of collaboration and pervasive institutional weaknesses.Footnote 11 Doner and Schneider (Reference Doner and Schneider2019) acknowledge that countries and regions able to buck this trend and encourage high levels of skill formation have one common feature: government actors, backed by strong parties with lengthy periods in power, who managed to overcome weak societal demand. These public actors generated strong programs, mostly top-down through the formation of coalitions. Brandt and Thun (Reference Brandt and Thun2016) found that in large emerging markets, government policy influences the opportunities for upgrading not only through their effect on the availability of know-how, inputs, and resources required for industrial upgrading (the supply side) but also through their impact on the incentives for upgrading (the demand side). Meanwhile, Andreoni and Tregenna (Reference Andreoni and Tregenna2020) study of subnational governments in industrial upgrading and GVCs insertion, showed how Chinese provincial leaders played a critical role. While both studies are highly relevant, the nature of the political regime in China makes it hard to extrapolate to contexts where a substantial degree of democracy exists and local governments are subject to electoral cycles, leaving ample room for additional analysis.

The subnational political economy of industrial upgrading

A rich body of literature on the political economy of industrial upgrading policies in developing countries examines the subnational level, underscoring the crucial role of political variables and business-government coalitions in regional upgrading.Footnote 12 However, the characteristics of business configurations that facilitate synergies have not yet been explored.

In his seminal study, Montero (Reference Montero2002) assessed the importance of political factors for the emergence of synergy for industrial upgrading in Brazilian and Spanish provinces. The author found that delegation from elected politicians to bureaucratic agencies is a necessary but insufficient condition for producing synergy. He highlights the government characteristics required: horizontal ties, close contacts between policy-making agencies, and vertical ties between firms and public agencies (a.k.a. embeddedness) to create productive patterns of cooperation.Footnote 13 In a synergistic setup, state-business actors co-produce essential public goods, such as education and infrastructure, by leveraging federal-level policies.

Along similar lines, other qualitative studies have shown how different political approaches to reform, shape the ability of societies to build new institutions for economic upgrading. For instance, McDermott (Reference McDermott2007), in a comparative, longitudinal analysis of the wine industry in two Argentine provinces identified two main approaches: the “depoliticized” approach, where a powerful, insulated government imposes arm’s-length incentives, exacerbating social fragmentation and impeding upgrading; and the “participatory restructuring” approach, where states promote the creation and maintenance of new public-private institutions for upgrading via rules of inclusive membership and multiparty, deliberative governance. McDermott and Rocha (Reference McDermott and Rocha2010) also argue that governments can facilitate upgrading by developing institutions with private actors to improve local firms’ access to various knowledge resources.

Analyses of Mexican states’ economic development have explored how the evolution of local political institutions impacted the possibilities for structural transformation. Kahn’s (Reference Kahn2019) most similar case study of Puebla and Querétaro concluded that despite initially sharing factors like location, human capital stocks, infrastructure, and industrial development levels, the two regions’ trajectories diverged because of political interactions. Differences in the patterns of interaction among government, business, and (to a lesser extent) labor explain the states’ divergent economic outcomes during and after Mexico’s economic and political reforms in the 1990s. In the case of Querétaro, local elites cooperated through regular tripartite consultation, norms of compromise and conciliation, and the inclusion of top business leaders in key posts within the state bureaucracy. By contrast, in Puebla, confrontation and co-optation between local governments and organized business prevailed. While the analysis is a relevant point of departure, it does not fully grasp the potential value of sectoral business organizations and the emergence of a capable bureaucracy.

An in-depth longitudinal study of Querétaro by Fuentes and Pipkin (Reference Fuentes and Pipkin2023) revealed how this state was able to foster industrial upgrading through “partial” coalitions, groups of actors from the state, private firms, and civil society organizations such as labor unions that participated in industry-level decision-making. Meanwhile, Tijerina’s (Reference Tijerina2019) study points to the multileveled nature of industrial upgrading where federal and local initiatives coexist and shape each other.

Finally, Samford’s (Reference Samford2022) quantitative study of SME Fund implementation in Mexican states, found that governments tend to use horizontal and passive interventions that address the immediate, short-term needs of local firms, rather than the targeted, risk-mitigating, conditional interventions that were historically effective for developmental states. This quantitative study explored a horizontal policy. Therefore, it leaves room for further exploration of the causal processes paying special attention to how local states and firms’ interactions shape program deployment over time.

A dynamic framework: state-business interactions for industrial policy implementation

Decentralization has allowed subnational units to generate their objectives and programs thus, their economic development plans might align or differ from those devised at the federal level.Footnote 14 Today, subnational actors can influence the adoption and implementation stage of the national policy-making process by obstructing, delaying, or modifying national policies.Footnote 15 Moreover, considering that governments in many middle-income trap countries are elected in a relatively competitive context (despite varying degrees of democracy), subnational authorities have increasingly tried to design, implement, and, if necessary, defend subnational policy regimes that deviate ideologically from the content of national policy regimes.Footnote 16

In this context, I posit that three variables play a crucial role in industrial policy implementation: executive leadership, bureaucratic quality, and business cohesion. The guiding hypothesis is that these three factors are necessary but not individually sufficient to implement a synergistic subnational industrial policy.

Executive leadership has been identified as a necessary pre-condition for policy implementation.Footnote 17 It entails the president/governor’s support towards specific policies and/or sectors in public acts, declarations, and official actions. In federal and/or decentralized contexts governors can choose whether they implement or not a national by opting in, providing supplementary resources, or ignoring/blocking it. Moreover, governors have an important impact on decision-making in contexts where bureaucratic quality is low.Footnote 18 Before moving forward, it is important to clarify that executive leadership is different from partisanship, a common explanation offered by scholars who consider that governors whose party aligns’ with that of the president will tend to support or benefit more from national-level policies.

Bureaucratic quality comprises the resources of administrative agencies to carry out policies chosen by politicians. It specifically relates to the human resources. Developmental state works demonstrated that bureaucratic quality, based on meritocratic recruitment and long-term career prospects, is a government-related variable essential for achieving industrial upgrading.Footnote 19 Embeddedness and informational capacity, the ability of bureaucracies to interact with and exchange information with the private sector, are particularly important (Juhasz and Lane Reference Juhasz and Lane2024, 14). Nonetheless, at the subnational level, most bureaucracies have shorter tenure times raising a challenge for industrial policy implementation. In sum, from the state side, executive leadership and bureaucratic quality are expected to be key variables in shaping the outcomes. Moreover, states can lead the creation of business coordination mechanisms. Prior studies show that state actors often help in the creation of sociopolitical associations.Footnote 20

Assessing firms’ role in industrial upgrading policy implementation is critical. As noted in the previous section, studies show that businesses can promote, block, or shape policy. I posit that at the subnational level, firms should have enough coordination capacity and business cohesion, to enhance the prospects of successful implementation of programs targeted at them. Business cohesion involves the existence of a well-organized group of firms with dense ties and resources benefiting the informational capacity of states and their embeddedness, especially in those states globally exposed to a broad variety of firms by size and origin. This argument challenges the mainstream view which considers dense associative ties produce dangers facilitating rent-seeking.Footnote 21 Instead, it highlights the potential benefits that business sectoral associations may bring.Footnote 22

I expect the following sequence in the processes of industrial upgrading at the subnational level. First, governors at the subnational level act as a veto or a catalyst for national policy implementation. While they may opt-in and channel resources, they can go further by actively leading. Though executive leadership is a necessary condition it is not individually sufficient, it requires some minimum levels of business cohesion and/or bureaucratic quality.

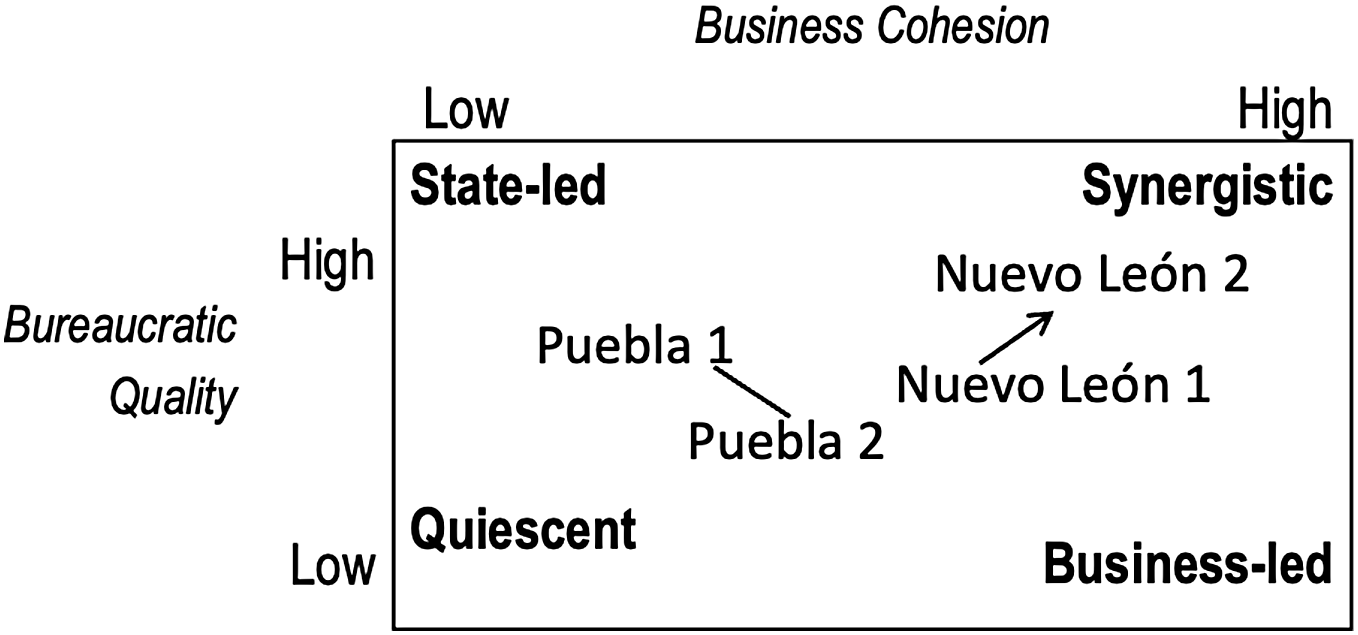

When policies are deployed, bureaucratic quality and business cohesion generate varied patterns of implementation: synergistic, state-led, business-led, or quiescent (Figure 1). These patterns lead to distinct outcomes in which synergistic processes will result in maximum benefits, whereas state-led and business-led patterns will produce moderate results. Finally, the quiescent pattern will lead to a failed implementation and thus minimum benefits.

Figure 1. Industrial policy implementation patterns and outcomesFootnote 25.

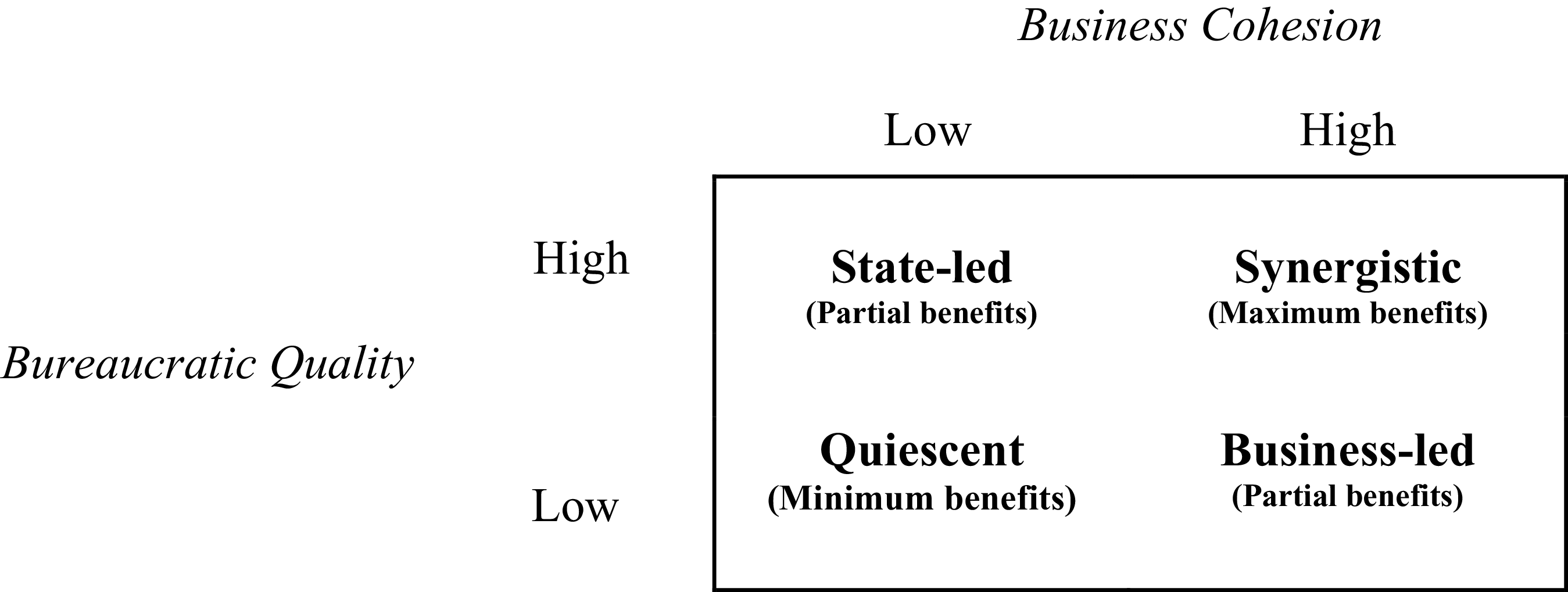

This framework is dynamic. State and business may shape each other over time (see Figure 2). The state, either through executive leadership or bureaucratic quality can foster firms’ cooperation and higher business cohesion through institution building. Meanwhile, business cohesion creates trust amongst firms in the sector increasing information sharing and coordination efforts in their interactions with the state. The information generated will be more complete as firms, once they have achieved trust, are willing to provide data, lobby, and jointly build programs to aid sectoral development. Business cohesion is also beneficial for embeddedness because bureaucrats can coordinate with institutions with long-run horizons and professionals. Studies reveal a revolving door mechanism whereby bureaucrats move between business organizations and state agencies accumulating know-how and contacts that might be channeled into common goals.Footnote 23

Figure 2. States-business interactions.

The following section specifies the methods and case selection that will be used in the empirical analysis.

Methods and case selection

To test and refine the theory this paper undertakes a subnational comparison of two cases in Mexico: Nuevo León and Puebla in a similar case design. Mexico is an ideal country to study with a market-led development model and a robust exporting profile. Despite its GVCs integration, it remains stuck in the middle-income trap. In the 2000s the national government devised some industrial policies to foster strategic sectors like IT, aerospace, and automotive. In the case of the software sector, the Prosoft federal program launched in 2004 aimed at inserting Mexican regions into the IT GVCs. By 2008, 23 out of 32 states displayed some effort to support the software sector and varied implementation outcomes.

Prosoft took off in 2004, when Nuevo León and Puebla had akin levels of innovation potential, with a strong capability of creating value-added activities in the IT sector (see Map 1).Footnote 24 In the political realm, the federal executive was governed by the PAN (a business-friendly party), and a PRI governor ruled both states, and the two were eligible for Prosoft’s federal funds. While there could potentially be a negative effect given the lack of partisan alignment, both states should be equally affected. These similar characteristics control for unobserved factors. The geographic position is less important for IT services activities than for manufacturing since the outputs flow through digital networks and not physical infrastructure.

Map 1. Cases background information: innovation potential ranking. Source: Ruiz-Durán (Reference Ruiz-Durán2008).

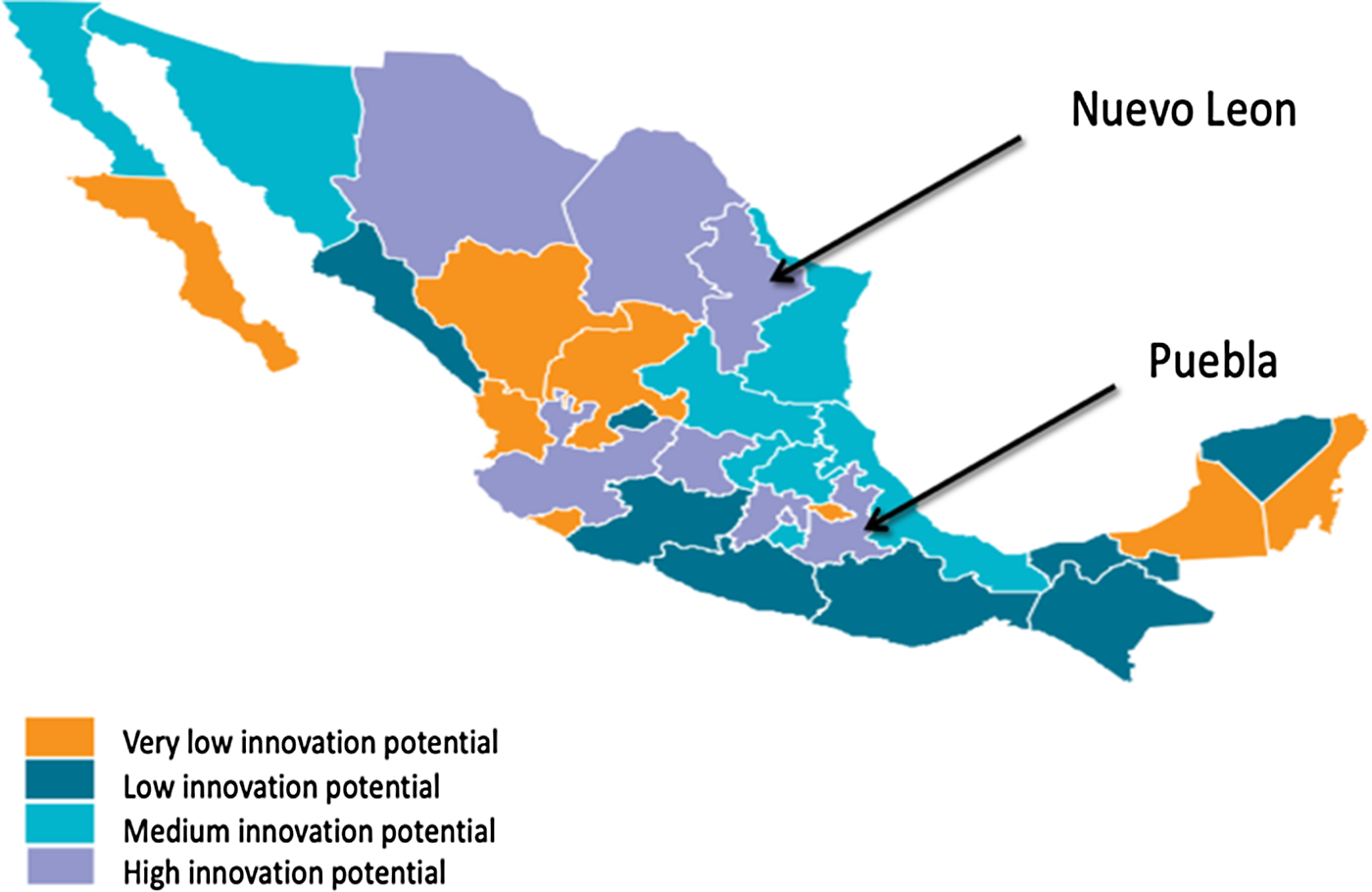

Despite initial similarities, Puebla and Nuevo León took different paths in implementing Prosoft IT sectoral policies. Map 2 illustrates this divergence by showing the accumulated amount of funds by state in 2015, the last year for which information is available. Nuevo León profited largely from funding, it became the top 2nd recipient, while Puebla lagged.

Map 2. Regional variation of Prosoft’s implementation, accumulated funds by state millions of Mexican Pesos, 2015. Source: Author’s elaboration with data from Prosoft (2018).

This preliminary correlational vision gives an initial sense of the importance of state-business dynamics countries’ attempts to upgrade and link to GVCs. Endogeneity is a threat to the validity of this study because industrial upgrading policy processes may shape the levels of business cohesion. The cases are divided into two periods 2000–2007 and 2008–2015.Footnote 26 This specific temporal setup considers changes in ruling party configuration at the federal and at the subnational levels which the theory points to as a main alternative explanation. In other words, if partisanship could explain the outcome of interest rather than my three-part explanation, then this should be apparent because of the use of partisan configurations as the dividing line between the two periods. Through process tracing techniques I identify the sequencing of the key variables and the outcomes: how executive leadership, bureaucratic quality, and sectoral business cohesion, shaped the industrial upgrading policy implementation of a federal program.Footnote 27

Independent variables are assessed as follows. Executive leadership is the level of a governor’s involvement in sector development: whether he makes declarations to endorse the policies, personally participates in committees, allocates budget, and/or instructs bureaucrats to materialize policies. Bureaucratic quality gauges administrative professionalism by looking at the education levels of public servants in regional economic development ministries, the length of their tenure, and whether a specific unit to support high-tech sectors exists. Business cohesion captures the existence of sectoral association(s) and/or organizational clusters, and membership levels in these types of associations. Unfortunately, most associations do not have a historical membership record, so interviews with former directors and secondary sources provided the necessary information.

The dependent variable, policy implementation, will be assessed through the total amount of funds allocated by the program under study to the state measured in absolute terms, and as a ratio per firm. A low amount of funds signals that a particular state did not opt-in, that is the quiescent policy implementation, leading to minimum benefits. If there is not enough collaboration in policy implementation from either the local business sector (state-led) or the state government (business-led) the result will be partial benefits. The synergistic policy implementation, with high levels of business cohesion and bureaucratic quality, will generate maximum benefits, that is higher levels of the total amount of funds by state (see Figure 1).

Case studies are based on twenty semi-structured interviews with key Monterrey, Puebla, and Mexico City actors and secondary sources including official economic development plans; program presentations; organization’s websites; and a thorough analysis of local newspapers.Footnote 28

Nuevo León: institutionalization for upgrading with federal resources

Nuevo León’s software industry emerged in the 1980s when local small and medium enterprises (SMEs) appeared to cater to a growing IT demand. Alongside, Mexican conglomerates based in Monterrey like CEMEX, VITRO, and ALFA created their IT areas to facilitate frontier technologies adoption in their operations. In 2004 there were approximately 200 firms in the state, primarily focused on the domestic market. By 2010, the panorama had changed. MNCs like Oracle, Infosys, and Tata had set shop to export or nearshore services to global markets. Some even specialized in niche markets (Contreras et al. Reference Contreras, Kenney, Mullan and Rangel-Padilla2008).

First period (2000–2007): attempts to encourage the software sector and prosoft

Medium-high business cohesion

In the early 2000s, the software sector in Nuevo León included 210 firms and three sectoral associations: the National Association of Computer Retailers (ANADIC-Monterrey) founded in 1998 by retailers of computer equipment and packaged software; the National Chamber of Electronics and Information Technology (CANIETI-Noreste) which opened its regional office in 2001; and the IT Entrepreneurs Association (AETI), founded in 2002 by sixteen local software entrepreneurs.

During Fernando Canales’s administration (1997–2003), association leaders, inspired by the Indian and Irish cases, lobbied the regional government for support. They contacted the regional Ministry of Economic Development (SEDEC) to explore collaboration possibilities, but these efforts were unfruitful.Footnote 29 In May 2003, business associations formally presented their demands to the two main gubernatorial candidates: Natividad González-Parás (PRI-center) and Mauricio Fernández (PAN-right).Footnote 30 The following years would be crucial for achieving their plans.

Executive leadership

Nuevo León had no IT sectoral policies before 2004 but a broader initiative was launched that year by the newly elected governor González-Parás. The Monterrey City of Knowledge project aimed to promote the emergence of knowledge-economy activities in the state. Though initially, it did not consider the software industry, sector leaders advocated for its inclusion.Footnote 31

González-Parás created the Software Industry Advisory CouncilFootnote 32 housed at the Ministry of Economic Development to promote software industry consolidation through the analysis of proposals stemming from the public, private, and academic sectors. It had 28 members representing regional and federal levels, firms, and the three largest universities. The three sectoral associations were incorporated too. Softtek’s CEO the main Mexican IT firm led it.Footnote 33 A well-known industry leader acknowledged that in achieving their goals: “Three elements coincided: the Monterrey City of Knowledge project, González-Parás creation of civic councils, and our sectoral program demands”.Footnote 34 Executive leadership was a necessary pre-condition and encouraged synergistic cooperation. Furthermore, Prosoft was launched in 2004, making federal funding available for the sector. Over time, a group of skilled bureaucrats in the regional Ministry of Economic Development embraced the implementation of federal Prosoft and supplemented it with specific strategies.

Medium-high bureaucratic quality

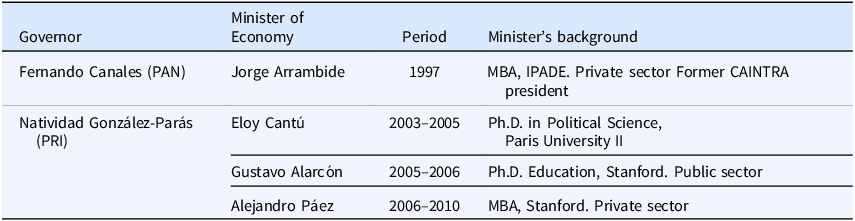

Nuevo León’s Ministry of Economic Development had medium-high bureaucratic quality by comparative Mexican standards in the early 2000s. All its directors held postgraduate education and prior business sector or government experience (see Table 1). Meanwhile, medium rank positions held bachelor’s in International Trade, Law, Economics, and International Relations. However, frequent leadership changes undermined such quality causing high turnover rates in the medium and lower ranks.Footnote 35

Table 1. Bureaucratic quality, Nuevo León 1

Source: Author’s elaboration.

A crucial decision strengthening bureaucratic quality was the creation of a dedicated area within SEDEC, the New Economy Unit, in 2005, to deal with firms in high-tech sectors. It gathered six persons with issue expertise. Rogelio Flores’, a lawyer with an MPA, appointment as unit director from 2005 to 2013 was pivotal. He had been a delegate of the national Ministry of Economy in Nuevo León; he knew federal and subnational levels needed coordination. An early Prosoft evaluation concluded: “Flores knew Prosoft’s goals deeply and was aware of the importance of fostering the IT industry in the state.”Footnote 36 The unit survived the governor and SEDEC’s leadership changes.

Assessment

Nuevo León’s software sector developed synergistic business-government collaboration under the Gonzalez-Parás administration. Amongst the emerging initiatives were the Nearshore Application Outsourcing program, the establishment of a formal software cluster, and the construction of a building for IT firms at the Technology and Innovation Park.

The Nearshore Application Outsourcing program emerged in 2004 to stimulate the sector with private and academic input. According to experts “It had clear goals: to increase the number of software companies by ten; raise the sales from 120 to 2000 million dollars by 2010; train software development skills; and promote firms’ quality certification processes. Finally, it proposed the creation of an organization to promote exports to the United StatesFootnote 37. The original Technology and Innovation Park project did not consider space for software firms, but business associations advocated for state-subsidized land and building construction to host SME firms.Footnote 38 The governor agreed to grant the land with two conditions: firms had to register as an organization and assume construction costs. The “Monterrey-IT Cluster” was formed with forty members, sharing construction costs and Prosoft funded the IT infrastructure (Villarreal Reference Villarreal2009). Finally, the Software Industry Advisory Council channeled business-government cooperation and shaped sectoral evolution in the following years.

In sum, this first period reveals how executive leadership enabled Prosoft’s deployment and medium-high levels of business cohesion with medium bureaucratic quality, generating a synergy facilitating policy implementation. Governor leadership was crucial. González-Parás promoted the idea of the triple helix where business, state, and academia would join. He participated in several public events endorsing such collaboration. IT firm’s organization into associations eased public-private dialogue and coordination. By 2007 business associations’ affiliation rates were high, with 75 percent of firms in the sector enrolled in one of them. ANADIC-Monterrey had 55 members. CANIETI-Noreste had 40 and AETI had 67 members. The three consolidated into a single association. Medium-high quality bureaucracy at the sub-national level was essential. The private sector met with a government counterpart who carefully assessed the proposals and channeled funds toward projects that could spill over to the industry. Bureaucratic quality increased over time with the creation of the New Economy unit.

Second period (2008–2015): with and beyond prosoft

High business cohesion

Business associations played a critical role in gathering industry information. Including SMEs in these associations increased cohesion. In 2008 AETI merged with CANIETI-Noreste. They “set a common agenda and the fusion increased the business sector leverage vis-à-vis the government.”Footnote 39 CANIETI-Noreste channeled benefits like training and events to their members, primarily SMEs. It also hired a person to advise firms on Prosoft’s funding application process. The chamber ensured that government plans prioritized the IT sector. They lobbied when plans to reduce funding appeared. Another critical role of this organization was to generate a database of sector firms and host monthly networking events. It also sponsored a survey of wages to offer firms a salary benchmark to prevent employee poaching.

Executive leadership

Nuevo León held gubernatorial elections in 2009. Voters favored continuity. PRI candidate Rodrigo Medina won 49 percent of the votes followed by PAN’s candidate Fernando Elizondo with 43.4 percent. Othón Ruiz, former director of the largest Mexican-owned bank (Banorte), was appointed head of SEDEC. The new administration went through a learning curve to understand the strategic sectors (including software). But after that phase, the governor backed the IT sector.Footnote 40 Executive leadership decreased as Medina did not actively promote C-Soft’s activities. His support was indirect through SEDEC. Still, the administration funded Prosoft uninterruptedly from 2009 to 2015. The SEDEC, in coordination with business associations, continued guiding firms’ funding applications. As a result, Nuevo León remained the third top recipient of Prosoft funds.

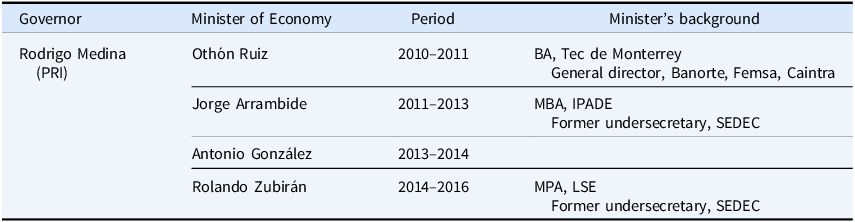

High bureaucratic quality

The profile of the regional ministers of economic development was similar to those from 2000 to 2007 (see Table 2). Ministers changed frequently. Nevertheless, the New Economy Unit had stable mid-level ranks with accumulated knowledge, facilitating information gathering and the evaluation of software sector initiatives. This assessment aligns with a qualitative analysis of Mexican states’ implementation of Prosoft in 2012 which concluded that the staff related to the IT programs in Nuevo León had extensive experience and had established procedures to promote stakeholder collaboration.Footnote 41 Nuevo León earned 8 points out of 10, the highest score assigned to any state. Jalisco also received 8 points. Meanwhile, Puebla scored 3 points, alongside sixteen other states.Footnote 42

Table 2. Bureaucratic quality, Nuevo León II

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Assessment

Higher levels of business cohesion and bureaucratic quality facilitated regional Prosoft’s policy continuity. Most policies developed during the second period consolidated initiatives launched in the mid-2000s. Prosoft’s federal funding stability was also beneficial, providing much-needed financial resources. Public initiatives towards the software sector increased business cooperation and spurred synergistic processes.

In 2008, the synergy was institutionalized with the transformation of the Software Industry Advisory Council into the C-Soft cluster.Footnote 43 Rather than being merely advisory, the C-Soft, sponsored by the regional government through the Law of Economic Development, acquired a permanent staff, office space, and a director. For every peso they spent, the regional government would contribute another.Footnote 44 C-Soft set an advisory board membership fee to raise additional funds and offered training courses.

C-Soft has promoted business cohesion with three priorities: human capital formation, stimulating innovation, and firm financing. It organizes industry events and has developed major collaborative skill-formation projects with local universities and firms. Many other informal linkages and exchanges have also emerged.Footnote 45

The C-Soft created the IT Talent Development Institute in 2008 to increase local human resources stock. Five universities supported the program (UDEM, UANL, Tec de Monterrey, U.R., and Tec-Milenio), coordinating their curriculum design with firms. Mexico First, a World Bank-federal Ministry of Economy initiative, partly funded the program. Another outcome of business-government collaboration and Prosoft’s funding was the completion of the MTY IT-Cluster a 14,700-square-meter building at the Innovation and Technology Park in 2013. Thirty-five firms shared office space and infrastructure in it.Footnote 46

The second observation of Nuevo León’s case reveals that high business cohesion is a necessary condition for the implementation and survival of industrial upgrading policies. When executive leadership decreased, bureaucratic quality became decisive. Over time, the creation of institutions preserved the synergistic business-state collaboration. The real test came in 2016 when the PRI lost the gubernatorial elections to an independent candidate. However, the level of institutionalization of business-government cooperation through C-soft ensured the survival of the programs despite political alternation. The new administration continued its support for the software industry and included this sector in the State Development Plan.Footnote 47 Rodríguez also visited India in June 2017 to attract additional IT-sector foreign investment from that country.

Puebla: lost opportunities for the IT sector

The origins of the software sector in Puebla date back to the 1990s when firms emerged or arrived to cater to manufacturing activities in the region. The state has a significant agglomeration of auto parts firms attracted by the longstanding presence of Volkswagen. One of the oldest and most influential companies in the evolution of the software sector is the multinational company T-Systems,Footnote 48 which set up its Mexican headquarters in Puebla in 1995. Initially, it provided IT services exclusively to Volkswagen. Eventually, the company developed other customers throughout Mexico and Latin America.Footnote 49 The rest of the firms were domestically owned SMEs. In 2004, there were approximately eighty firms.Footnote 50 The state hosted around 5% of the total Information Technology college-level students in Mexico, and 45 universities offered IT degrees.Footnote 51

First period (2000–2007) efforts to Spur the IT sector and prosoft’s implementation

Low business cohesion

Software firms in Puebla displayed low business cohesion in the early 2000s. The only sectoral association was ANADIC-Puebla, which had a limited scope because it only represented the interests of computer equipment distributors. Businessmen recall software firms trying to organize a branch called ANADIC-Soft, but the effort did not consolidate.Footnote 52 CANIETI could have helped in coordinating software firms, as it did in other states through its regional offices; nevertheless, it did not set up one in Puebla.

Instead, firms organized within the encompassing association CANACINTRA-PueblaFootnote 53. There, software entrepreneurs created the CANACINTRA-TI branch to coordinate their efforts, especially in training and later, cluster creation. They held monthly meetings, organized business trips, and generated an IT services yearbook. While this alternative allowed them to lobby through a well-known encompassing association, they were subject to the policies and, especially, the politics of CANACINTRA.Footnote 54 Since IT was an emerging sector, its voice was weaker than other well-established sectors like textiles and automotive.

Firms in Puebla’s IT sector attempted to institutionalize their cooperation through the ‘cluster’ concept several times but their attempts were unfruitful.Footnote 55 Businessmen acknowledged that their main challenge was to increase collaboration levels through sectoral associations: “In Puebla, we need associations like CANIETI that can help to develop the sector”.Footnote 56An early effort in 2005 was the CANACINTRA-TI cluster legally constituted by the fifty-two members in this section.Footnote 57 Nevertheless, it did not mature because of low trust and decreased membership levels.Footnote 58 Another failed attempt was Puebla en TI, which grouped twenty small local companies and a few universities.Footnote 59 However, it was not recognized by the Federal Ministry of Economy and eventually dissolved. T-Systems, the largest firm (foreign-owned) in the state, did not join any cluster. Instead, the MNC negotiated directly with authorities and universities.

Low executive leadership

The PRI ruled Puebla when the federal government launched policies to stimulate the software sector. Melquíades Morales governed from 1999 to 2005 and Mario Marín from 2005 to 2011. Both administrations implemented Prosoft funding with 25 percent of the total amount of resources from 2004 to 2011 every year except for 2005. In 2006, there was a lack of participation from the regional government, which Canacintra-Puebla president Charles Mtanous quickly criticized. He publicly requested that the governor continue funding the IT sector. The Minister of Economic Development (SECOTRADE) promised to allocate 20 million pesos that year.Footnote 60 From then until 2010, funding was available in Puebla every year.

However, neither Morales nor Marín assumed a leading role, supported the creation of administrative areas, or sent a message of collaboration to stimulate Puebla’s software sector. Archival searches in Puebla’s newspapers do not reveal any special declarations or commitments to generate institutions or programs. A review of Puebla’s Development Plans for 2000– 2008 reveals that the software sector was not considered strategic. In sum, the executive did not foster public-private collaboration projects.

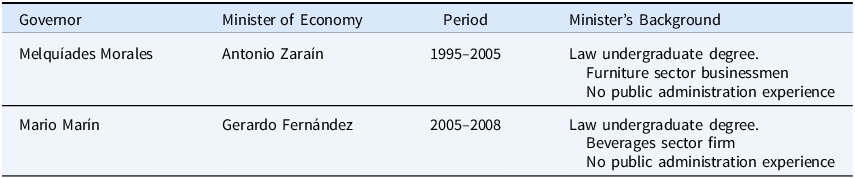

Medium bureaucratic quality

Puebla’s ministers of Economic Development had private sector experience and undergraduate degrees. However, none held graduate education or public administration training like their counterparts in Nuevo León (see Table 3).Footnote 61

Table 3. Bureaucratic quality, Puebla I

Source: Author’s elaboration.

SECOTRADE did not create a specific unit to stimulate high-tech sectors. Other ministries, like the Ministry of Education, hosted most IT sector-related programs. Its head Darío Carmona, held an MPA and had been Marin’s campaign coordinator, suggesting political motivations underlying bureaucratic appointments.

Assessment

From 2000 to 2007, Puebla’s government announced various programs to stimulate the software sector, but none were consolidated. Some of these programs attempted to generate business-government collaboration, but they were relatively shallow and did not persist. No specific council or formal body emerged to foster public-private cooperation. As a result, Puebla lost a valuable chance to link to the IT services GVC despite its favorable ecosystem.

One of the first initiatives to promote Puebla’s software industry development was set up unilaterally by Puebla’s Ministry of Education in 2002, the Program to Stimulate the Software Industry (FISEP). Its goal was to train technicians to supply the market’s needs for skilled labor. The program offered grants to university students participating in a competitive process yearly. Microsoft contributed MXN $2.5 million (US$250,000) for software.Footnote 62

Puebla’s government launched the Center for Innovation and Information Technologies (CITIP) in 2006. But it is unclear which bureaucrats were involved. Housed in the Ministry of Education, CITIP was funded by Microsoft Mexico and Puebla’s Council for the Development of Industry, Trade, and Services. Its goals were: “articulate business, academia, and government to spur innovation and technology development in the state”.Footnote 63 CITIP encompassed several initiatives including training through FISEP, attracting foreign projects through development centers, and supporting the professionalization of local IT firms. The center would be the first to focus on developing software for mobile technologies and provide training, certification, and IT consulting to firms, students, and government.Footnote 64 The CITIP disappeared in 2011 with the Moreno-Valle administration. Some firms engaged in the project decided to create a cluster without regional government participation or support.Footnote 65

This first observation of Puebla reveals the outcomes of low cohesion in the business sector, low executive leadership, and medium bureaucratic quality. The business sector could not overcome differences and failed to create an organization to voice its demands. While they did gather within CANACINTRA, their power was diminished by broader concerns or disputes. Though the PRI governors agreed to implement Prosoft and even allocated state funds, they did not encourage the institutionalization of public-private collaboration. Bureaucrats at the Ministry of Economic Development had private sector experience but did not develop a coordinating capacity. This combination of factors left the software sector vulnerable, as will be evident in the next observation.

Puebla 2 (2008–2015): business-led policy implementation without subnational government support

From 2008 to 2011 Puebla was still ruled by Mario Marín, who maintained his tepid support for the sector via Prosoft. Still, there was no attempt to formalize business-government collaboration for industrial upgrading policies. In 2010, CANACINTRA-TI’s president rebuked Marín’s administration for not giving enough support to the IT sector and not meeting its commitment to create an industrial park for IT firms. He said such unmet promises hindered the growth of Puebla’s software firms and urged the newly elected governor to back the sector.Footnote 66 Still, most public programs did not survive the change of administration in 2011. During Rafael Moreno-Valle’s (PAN) administration, regional funds for Prosoft dropped to zero. Facing this scenario, some businessmen led efforts to increase coordination and secure federal support.

Medium business cohesion

The Puebla-TIC cluster was created in 2007 by thirteen firms from Puebla’s CANACINTRA-TI and the CITIP (the initiative led by Puebla’s regional government). Despite initially being a government-business and university coalition, Puebla-TIC evolved into a firm-university cluster, leaving public authorities out in 2011. Puebla-TIC’s goal was to increase members’ commitment levels and participate in Prosoft. In 2013, it inaugurated an office space and was staffed with five persons. Cluster associates and the Federal Ministry of Economy launched a software factory for Puebla.Footnote 67 In 2016, Puebla-TIC leaders decried not receiving the promised state support to build a technology park, claiming that its construction could have promoted sectoral consolidation.

Meanwhile, T-Systems, the largest multinational firm in the state, did not join business collaboration efforts in this second period either. Instead, it applied directly to Prosoft via national CANIETI. In 2015 it won MXN$4,249,908, representing 90% of the total funds allocated to Puebla that year.Footnote 68

Low executive leadership

Official SECOTRADE documents show an IT strategy on paper for the 2011– 2017 term. The main objective was to “generate strategic alliances to create high value-added projects by strengthening human capital, funding, research and development, intellectual property rights, technology infrastructure, and commercialization. Planned actions included fostering a public-private agenda to boost entrepreneurship in the IT sector, encouraging collaborative innovation projects, and signing research and development agreements with universities.Footnote 69

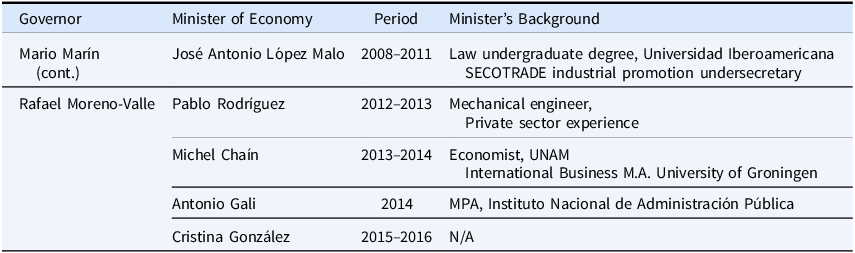

However, field research revealed that none of the actions were executed. Interviewees noted that the regional state decided not to invest in the IT sector. There are no news reports or statements from the minister of economic development or the governor supporting the program. Evidence shows state neglect: the regional share of Prosoft’s funds dropped to zero after the Moreno-Valle administration took over in 2011 (see Table 4). A report commissioned by the Federal Ministry of Economy in 2012 echoes these conclusions, noting that “in Puebla, there was a lack of commitment from top decision-makers and poor communication among different actors to achieve sector goals”.Footnote 70

Table 4. Bureaucratic quality, Puebla II

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Medium-low bureaucratic quality

Bureaucratic quality in Puebla had a medium-low level from 2008 to 2015 with high turnover rates (five ministers in six years, see Table 4). Some analysts criticized it for being understaffed and because other ministries were transferred some of its duties. During the Moreno-Valle administration, SECOTRADE was led by Pablo Rodríguez from 2011 to 2013, but he resigned to run for a congressional seat. Business representatives declared that after Rodríguez exit, “the private sector lost contact with SECOTRADE”.Footnote 71 The regional government funding for Prosoft vanished.Footnote 72 For ten months, the ministry lacked a director. Finally, Michel Chaín was appointed, though he resigned ten months later. Antonio Gali, the Business Promotion undersecretary, was named minister in 2014. Two additional changes occurred in the following years.

By 2014 only one bureaucrat, Manuel Herrera, who held an M.A. in political communication and governance from George Washington University, was assigned to provide information about Prosoft and refer potential applicants to the federal Ministry of Economy delegate in Puebla. Since the state was not supplementing funds, firms presented their projects through other authorized organizations, like CANIETI.

Private sector representatives in Puebla asserted that SECOTRADE “bureaucrats did not have experience with either the IT sector or with the procedures to facilitate the relationship between different actors” and “there was a lack of personnel with the vision and knowledge to promote IT sector development”.Footnote 73 Analysts also warned about the low capacity to coordinate with the private sector and universities. Stezano and Padilla-Pérez noted: “Puebla’s regional government organizations’ capabilities are still feeble and respond to an exogenous factor (the increased flow of resources coming from federal programs) and not from the state-level development of priorities that allow them to generate their policies or programs… we observe a low organizational capacity to diagnose its industrial priorities through studies and assessments of innovation capacities and to develop policy planning with the participation of multiple actors”.Footnote 74

Assessment

Puebla experienced a power alternation in 2011. Theoretically, a PAN governor would align better with the PAN-led federal government and with the business sector. However, the business-government relationship worsened. Puebla’s contribution to Prosoft’s dwindled from 2011 to 2015 (See Table 4). The official reason was budget pressures. A key bureaucrat at SECOTRADE declared that despite being strategic, the IT sector in Puebla “has been very problematic, very politicized”.Footnote 75 Additionally, he expressed distrust: “We believe entrepreneurs aim to secure funds for personal benefits rather than sectoral growth”.Footnote 76

A subnational evaluation concluded Puebla had a “disarticulated process of defining sectoral plans between the government and the IT cluster with limited participation from academia and other private sector actors who develop their plans independently. There are no shared strategies or goals, tied to state development plans”.Footnote 77 This view aligns with another study: “In Puebla, innovation and competitiveness activities are disjointed…Prosoft has had little relevance. After difficulties operating some projects, the state government ceased being a promoting organization, leaving CANIETI to operate the program in the state”.Footnote 78 Similarly, in 2014, a journalist described the IT sector in Puebla as “merely watching government actions from afar, without participating in projects to strengthen the firms and the local economy”.Footnote 79

This second observation reveals how Puebla’s IT sector could not fully benefit from Prosoft funding due to medium business cohesion, low bureaucratic quality, and lack of governor leadership, resulting in scant public-private collaboration. The chances of moving into a synergistic state-business relationship vanished. Interviewed software sector leaders claimed the governor never met with them. Others stated there was “moral” support but no resources because firms had misused public funds in prior administrations. In summary, despite Puebla’s potential for the software sector, it became a business-led case with many lost opportunities.

Cross-case comparison and alternative explanations

The case study observations show that firms in Nuevo León created synergy with the subnational government and tapped federal IT sector resources, aiding industrial upgrading. Meanwhile, Puebla lacked coordination among its business community, the dominant IT multinational, and the local government, hindering sectoral development. Despite having similar innovation potential and the opportunity to access federal funding through Prosoft, Nuevo León and Puebla displayed different trajectories in the software sector from 2000 to 2007 and 2008 to 2015 (See Table 5 and Appendix 2).

Table 5. Case studies overview

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Nuevo León, started with a medium-high level of business cohesion, medium bureaucratic quality, and an executive that encouraged innovation-intensive activities. In this scenario, business organizations were able to lobby and work with a government that created formal spaces to discuss proposals at the Advisory Council for the Software Industry. The synergistic process was institutionalized. Even though executive leadership fell from high to medium in the second period, business cohesion and bureaucratic quality remained high due to such institutionalization. The C-Soft brought state and businesses closer, generating multiple joint initiatives, and surviving governor changes. In general, Nuevo León has linked to GVCs by attracting FDI into this sector, and local firms have found higher value-added export niches.Footnote 80 Whereas in Puebla, GVC insertion is limited and has tended to be in lower value-added activities such as customer support.

Puebla displayed low executive support, low business cohesion, and medium bureaucratic quality. No synergistic processes appeared. The state-led some initiatives through the Ministry of Education, but these were short-lived. In the first period 2000–2007 and until 2011, Puebla provided funds for Prosoft. However, public–private cooperation was not institutionalized. In the second period, Puebla’s governors did not lead any special initiatives for this purpose either. Local firms and the federal government tried to increase business cohesion through the Puebla-TIC cluster, but bureaucratic quality and executive leadership remained low. The outcome is limited, a case of lost opportunities.

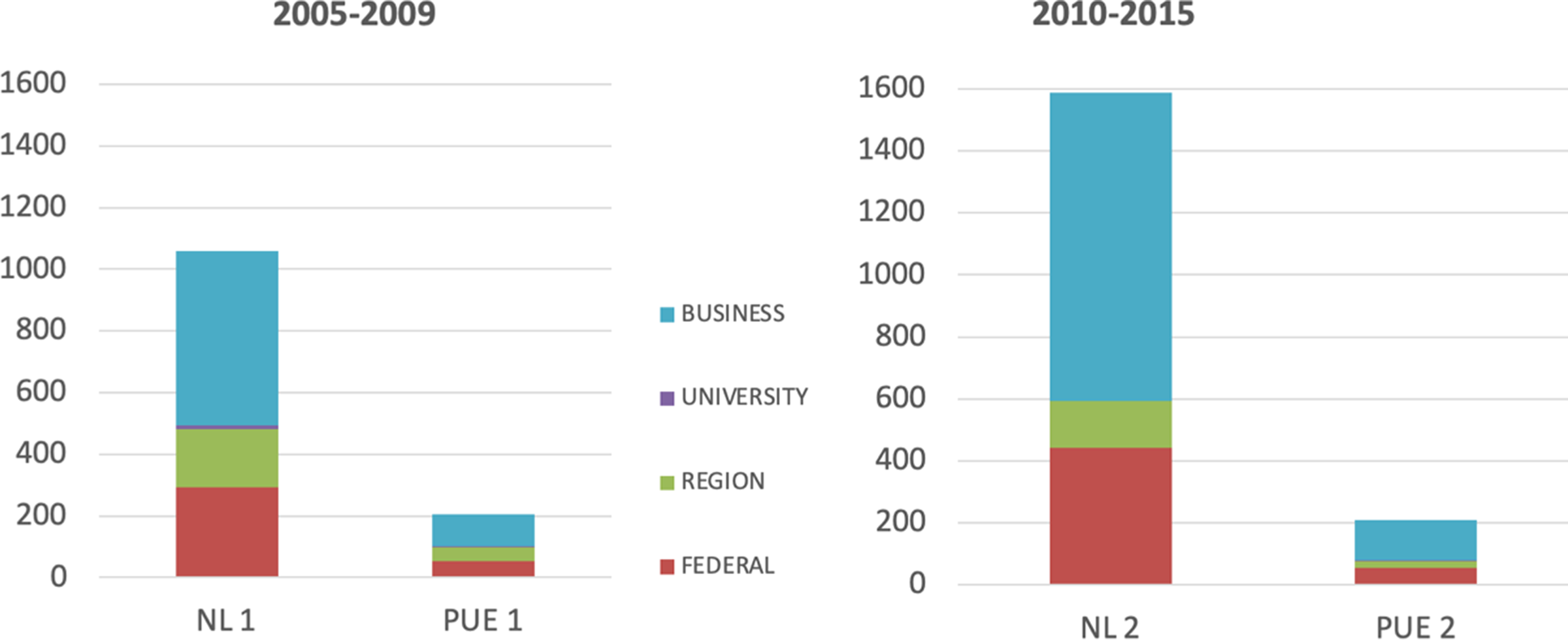

Figure 3 presents Prosoft’s total funds for each state by stakeholder type. It shows how state-business synergies led to higher investment amounts in Nuevo León. From 2005 to 2009, Nuevo León received MXN$1,070 million, while Puebla received MXN$215 million. And for 2010–2015, the former gathered MXN$1,587 million, and the latter MXN$208 million. Regarding total gross production of the IT sector, Nuevo León held its 2nd place nationwide since 2003. Meanwhile, Puebla fell from being the 5th largest producer of IT services in 2003 to 12th place in 2013 INEGI (2014).

Figure 3. Prosoft funds distribution by Stakeholder Mexican million pesos. Source: Author’s elaboration. Ministry of Economy data.

In sum, empirical cases reveal that executive leadership, bureaucratic quality, and business cohesion are necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for a synergistic outcome. This in turn maximizes program implementation benefits, especially when institutions are inexistent or young. Individually, executive leadership, bureaucratic quality, or business cohesion can foster policy implementation through state-led or business-led processes, but with limited or minimum results (see Table 5). Once institutions have consolidated, as was the case in Nuevo León (2008–2015) high levels of business cohesion or bureaucratic quality can partially compensate for lower levels of executive leadership.

Regarding the generalizability of the theory, a recent interview with a former bureaucrat in charge of Prosoft’s implementation in Chiapas (a state in southern Mexico that could be considered in the quiescent quadrant of the typology) noted that the governor had a significant influence in deciding whether to include the program in his agenda. Encompassing business organizations were not interested in it because their members were mostly in the traditional services sector (i.e. tourism) and they prioritized their immediate needs. In the early 2000s, two dozen software firms in Chiapas attempted to organize a sectoral association but failed.Footnote 81

Prosoft could not take off in that state despite bureaucrats’ enthusiasm in trying to generate projects using available federal funding because executive support changed with administrations, and there were no career bureaucrats nor cohesive businesses to act as partial substitutes. Chiapas’ first year gathered MXN$9.16 million pesos and accumulated only MXN$53.39 million in funds in 2015, representing one-eight of those accumulated by Puebla. A promising avenue of research would be quantitatively testing the theory or applying it in other MIT national contexts.

An alternative explanation for divergent policy implementation often found in the subnational policy literature is partisan alignment: whether the federal executive and the regional governor belong to the same party or not.Footnote 82 The argument is that in the absence of partisan alignment, governors are reluctant to implement national policies, especially if there is clear attribution. However, Nuevo León and Puebla were both ruled by the PRI in the first period of observation. Yet, Nuevo León largely benefited and actively participated in the program designed by the PAN-governed federal government. In the second period of observation, it is paradoxical that even if Puebla was ruled by the PAN, thus fully aligned with the PAN-led federal government, the state did not fund any Prosoft projects.

Another potential explanation relates to intraregional competitionFootnote 83 which claims that intense intraregional political competition leads to a delegative government making industrial policy implementation more likely. However, Puebla’s electoral margin of victory was lower than Nuevo León’s. In 2004, Marín (PRI) won the election with 49.6 percent of total votes and his closest rival from the PAN, 35.97 percent. Meanwhile, in Nuevo León, González-Parás (PRI) won 56.6 percent in 2003 against PAN which got 33 percent. Theoretically, this implies stronger competition in Puebla, deriving in a delegative government. Likewise, in 2010 Rafael Moreno PAN won with 50%, and the rival PRI obtained 45.07%, whereas in 2009 in Nuevo León PRI won 49.0% and PAN received 43% of total votes. However, a delegative government did not emerge in Puebla.

The structure of the sector does not seem to have a clear impact on the outcomes either but opens an interesting research avenue. Small and micro firms comprised 72% of the total in Nuevo León and 73% in Puebla.Footnote 84 Both states also had a few large firms oriented toward international markets. In Puebla T-Systems (Germany), Microsoft (United States.), and in Nuevo León Softek (Mexican), Oracle (United States), and other Indian-based firms. The division between foreign-owned against Mexican-owned MNCs may have an impact on business cohesion. Mexican-owned MNCs might be better embedded in associations and have closer relations with local politicians and bureaucracies. Still, other cases reveal that foreign-owned firms collaborated with the Mexican authorities at the federal level in Prosoft’s design (Rangel-Padilla Reference Rangel-Padilla2021). In Querétaro, Canadian-based Bombardier has also encouraged public–private collaboration leading to the creation of an aerospace cluster.

Finally, geographic location, specifically sharing a border with the US, is a frequent explanation for Nuevo León’s success. However, in the case of IT services physical proximity is not a decisive factor. Moreover, Jalisco which is not a border state, accumulated even more funds than Nuevo León.

Conclusions

The interplay between business cohesion and bureaucratic quality fundamentally shapes industrial upgrading in today’s globalized, decentralized economy. This paper’s main contribution is to build and test a theory to explain industrial policy implementation in middle-income countries. Through a detailed examination of two Mexican states, Nuevo León and Puebla, this analysis reveals how governors, local business organizations, and bureaucrats can either catalyze or constrain industrial transformation. When business communities are cohesive, they successfully lobby executives, build enduring partnerships with bureaucrats, and sustain long-term development initiatives. Without such cohesion, governors become decisive veto players, demonstrating how subnational political dynamics critically determine industrial policy success even in globally integrated markets.

This subnational comparative approach advances our understanding of industrial policy implementation by controlling for national-level variables that often confound cross-country studies. By highlighting how executive leadership, bureaucratic quality, and business cohesion shape policy outcomes across regions with similar institutional frameworks, the findings offer crucial insights for both scholars and practitioners seeking to understand when and why industrial upgrading succeeds or fails.

Lastly, the persistence of gubernatorial discretion over industrial policy implementation in Mexico and across the Global South reveals the limits of bureaucratic quality and business cohesion alone. Yet this analysis points to a promising path forward: the institutionalization of public-private coordination spaces. When properly structured, these forums can anchor industrial upgrading initiatives beyond electoral cycles, transforming temporary political commitment into durable development partnerships.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank participants in several conferences and workshops for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper. This includes REPAL, APSA and SWMMR conferences in 2019, the Fundar-MIT Workshop, the Graduate School of Government and Public Transformation Seminar, and the Political Science Department Seminar at Tecnológico de Monterrey in 2024. I am also grateful to Alberto Fuentes, Carlos Freytes, Tomás Bril-Mascarenhas, Gerardo Munck, Richard Doner, Agustina Giraudy, Sebastián Mazzuca, María Paula Saffon, Richard Snyder, the editor, and two anonymous reviewers at Business and Politics for their constructive feedback and suggestions, which helped sharpen the manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared.

Appendix

Appendix 1. Interview list.

Appendix 2. Case trajectories