Introduction

In recent years, radical right parties have secured increasing public support in many advanced democracies and gained electoral ground, following political campaigns that exploited public anxieties around globalization and migration (e.g., Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). At the same time, several countries have experienced political violence motivated by extremist right-wing ideologies (Piazza, Reference Piazza2017; Ravndal, Reference Ravndal2018). Whereas these two phenomena are certainly distinct – and radical right parties use conventional democratic means to influence politics whereas extremists openly reject democracy (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Ravndal, Reference Ravndal2018) – violence on the right often intersects with traditional politics. For one, the two groups embrace the same rhetoric characterized by frustration with the political establishments, support for authoritarian values, concerns about a dilution of national identity, as well as prejudice and intolerance towards ethnic and racial minorities (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Ravndal, Reference Ravndal2018).

Although political activists seldom engage in actual violence and often condemn violent methods (Bjørgo & Gjelsvik, Reference Bjørgo and Gjelsvik2017), little is known about the extent to which radical right political violence favours or hinders public support for the ideas they advance. Extremist individuals engaging in such activities often believe that their views are enjoying growing social legitimacy and acceptance (Perliger, Reference Perliger2017); and far-right movements express anti-immigrant and culturally protectionist positions that are often popular among moderate sectors of the electorate and promoted by mainstream conservative parties (Abou-Chadi & Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2018; Van Spanje, Reference Van Spanje2010; Wagner & Meyer, Reference Wagner and Meyer2017).

We ask whether right-wing terrorism affects political orientation and the support for ideas that are shared to varying degrees by mainstream conservative parties. Recent studies have investigated how terrorism affects public opinion and have demonstrated that terrorist incidents lead to more support for right-wing parties (see, e.g., Aytaç & Çarkoğlu, Reference Aytaç and Çarkoğlu2019; Berrebi & Klor, Reference Berrebi and Klor2008; Getmansky & Zeitzoff, Reference Getmansky and Zeitzoff2014; Kibris, Reference Kibris2011). Yet, with the exception of studies on the 2011 terrorist attack in Norway (e.g., Fimreite et al., Reference Fimreite, Lango, Lægreid and Rykkja2013; Jakobsson & Blom, Reference Jakobsson and Blom2014; Solheim, Reference Solheim2018), they have largely focused on Islamist extremism or assumed homogeneity in the characteristics of perpetrators and their driving goals.

The perpetrators of radical-right violence often express ideas that are becoming prevalent within some sectors of wider society. If anything, diluted or more moderate versions of their ideology are shared by some segments of the public, such as a decreasing tolerance towards immigration or increasing concerns for the protection of national identities (Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018). Yet, there is an important moral dimension associated with violence; that is, its incompatibility with the values and needs of the general population. Violent tactics make it more likely that movements and political actors are perceived as unreasonable by citizens, who identify less with, and ultimately support less, the ideas they promote (Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Willer and Feinberg2018). Violence is particularly unlikely to resonate well in democracies, even when some of the demands may be considered legitimate by a segment of society (Muñoz & Anduiza, Reference Muñoz and Anduiza2019). As such, negative views of the attack may lead people to dissociate not only from the terrorist but also from their ideas (Jakobsson & Blom, Reference Jakobsson and Blom2014; Solheim, Reference Solheim2018). This simple argument leads to the theoretical expectation that right-wing extremism pushes the public to distance itself from the attack and the perpetrator and thus makes it less likely to support far-right ideologies.

We investigate whether right-wing extremism affects citizens’ political orientation in the United Kingdom, an interesting and timely case study as a third of all terror plots since 2017 were driven by extreme-right causes. In December 2016, the UK Home Secretary proscribed the first extreme right-wing group, National Action, under the Terrorism Act 2000 (UK Home Office, 2018). And in 2019, ‘extreme right-wing’ terrorism has been included in official threat-level warnings for the first time. We leverage four waves of the British Election Study (BES) (Fieldhouse et al., Reference Fieldhouse, Green, Evans, Schmitt, van der Eijk, Mellon and Prosser2018) and employ a quasi-experimental approach that exploits the occurrence of an unexpected event (terrorism) during the fieldwork of a survey to assign respondents to treatment and control groups as good as randomly (Balcell & Torrats-Espinosa, Reference Balcells and Torrats-Espinosa2018; Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020). We complement this strategy by exploiting the panel dimension of the data and controlling for individual baseline information to further address issues of unobserved confounding factors and differential response rates (Nussio, Reference Nussio2020).

We focus on two well-known incidents that were incited by extreme-right propaganda: the 2016 murder of MP Jo Cox by a 53-year-old gardener with far-right views and links to British and American far-right political groups; and the 2017 Finsbury Park attack, when Muslim worshippers were attacked in north London by a man influenced by the propaganda of far-right anti-Muslim organizations, such as the English Defence League.

We find that exposure to far-right terrorism shifts citizens' ideological positions away from the ‘right’ ideology; that is, following these incidents, individuals are less likely to place themselves at the right end of the political spectrum. We also show that respondents are less likely to report nationalistic attitudes that have been shown to affect radical right voting, such as national identification and immigration skepticism (Lubbers & Coenders, Reference Lubbers and Coenders2017; Rydgren, Reference Rydgren2008). This result suggests that there are some genuine shifts in the underlying attitudes typically associated with far-right electoral support, to the extent that these attitudes are less prone to social desirability bias. To lend further credibility to our causal claims, we implement Muñoz et al. (Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020)'s best practices in the form of falsification tests, placebo treatments and several other sensitivity and robustness checks, and the results carry over.

Data and methodology

We employ individual-level data from the BES – an internet panel survey with a stratified random probability sample of citizens living in England, Scotland and Wales. BES includes questions about the respondents' socio-demographic attributes and political preferences, as well as questions designed to capture their attitudes on key issues, such as immigration and national identity. Exploiting information from the survey waves that coincide with terrorist attacks allows us to examine the causal effect of terrorism on people's responses based on an ‘Unexpected Event during Survey Design’ (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020). Our identification strategy relies on the assumption that the timing of attacks is exogenous (unexpected) and largely randomly assigned relative to that of the interviews, and thus individuals interviewed after the attack can be defined as the ‘treatment’ group whereas those interviewed before the attack can be defined as the ‘control’ group.

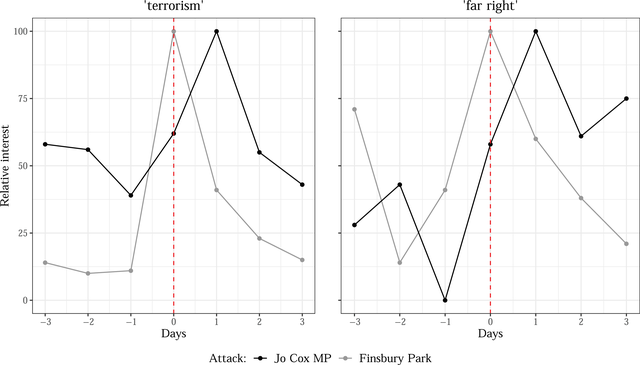

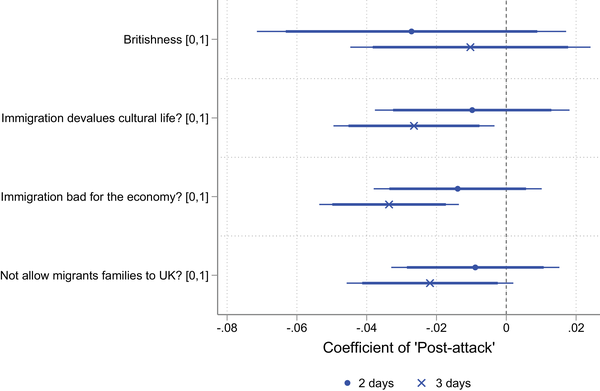

We consider two terrorist attacks that were motivated by far-right extremism: the murder of MP Jo Cox (16 June 2016) and the Finsbury Park attack (19 June 2017). Both attacks overlapped with recent BES waves (8 and 13, respectively) and received widespread coverage in national media outlets, which makes them particularly salient and impactful. The latter ensures that, regardless of where each attack occurred, individuals from all over the United Kingdom were potentially exposed to them. Indeed, as captured by Google Trends (Figure 1), the relative search volume for the term ‘terrorism’ went drastically up 24 to 48 hours after the two attacks, suggesting a notable nationwide interest in these events. The similar patterns of the relative search volume for the term ‘far right’ also indicate that the two attacks were correctly classified – and perceived by the large audience – as far-right terrorism.

Our empirical model specification takes the following form:

Figure 1. Relative Google search volume. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The figure reports Google Search intensity for the keywords ‘terrorism’ and ‘far right’ within the United Kingdom 3 days before and after each event. Relative interest is comparable within each keyword and attack. The day with the highest search intensity takes the value 100, and all other points in the series are relative to this value. Source: Google Trends https://trends.google.com/trends/

where

![]() $\text{`Right Orientation'}_{irw}$ is a binary indicator capturing ideological self-placement at the right end of the political spectrum (values 8 or more on the 0–10 left–right scale) for individual i, living in the region (government office region) r and interviewed in survey wave w;

$\text{`Right Orientation'}_{irw}$ is a binary indicator capturing ideological self-placement at the right end of the political spectrum (values 8 or more on the 0–10 left–right scale) for individual i, living in the region (government office region) r and interviewed in survey wave w;

![]() $\text{`Post-attack'}_{irw}$ is a binary indicator that takes value 1 if the individual was interviewed after the day of the attack, and 0 before the day of the attack;

$\text{`Post-attack'}_{irw}$ is a binary indicator that takes value 1 if the individual was interviewed after the day of the attack, and 0 before the day of the attack;

![]() $\mathbf {Z}_{irw}$ is a vector of variables that includes gender, age, age squared, level of education (low, medium, high) and employment status (employed, retired, student, and not working);

$\mathbf {Z}_{irw}$ is a vector of variables that includes gender, age, age squared, level of education (low, medium, high) and employment status (employed, retired, student, and not working);

![]() $\lambda _{rw}$ represents region-by-wave fixed effects; and,

$\lambda _{rw}$ represents region-by-wave fixed effects; and,

![]() $u_{irw}$ is an error term, clustered at the region level. Our parameter of interest, γ, measures the effect of terrorism on political orientation, with a negative value indicating that exposure to terrorism drives the population away from a ‘right’ political stance. We employ short-range time windows before and after the attack (1–3 days' bandwidths) to substantiate the as-if random treatment assignment assumption and to minimize the possibility of other events driving the estimated effects (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020; Nussio et al., Reference Nussio, Bove and Steele2019, Reference Nussio, Böhmelt and Bove2021).

$u_{irw}$ is an error term, clustered at the region level. Our parameter of interest, γ, measures the effect of terrorism on political orientation, with a negative value indicating that exposure to terrorism drives the population away from a ‘right’ political stance. We employ short-range time windows before and after the attack (1–3 days' bandwidths) to substantiate the as-if random treatment assignment assumption and to minimize the possibility of other events driving the estimated effects (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020; Nussio et al., Reference Nussio, Bove and Steele2019, Reference Nussio, Böhmelt and Bove2021).

An important identification concern is that our γ estimate captures pre-existing trends in political preferences, which are unrelated to the two terrorist attacks. To address this possibility, we focus on the sub-sample of survey participants who are interviewed twice (once during the attack's survey wave and once more during the previous wave) and augment Equation (1) with the lagged value of the dependent variable; that is, individuals' right orientation as observed in the previous wave. This set-up enables accounting for the baseline level of our outcome variable (similar to a difference-in-differences design) and also controls for biases arising from the potential omission of unobserved characteristics (Bove et al., Reference Bove, Efthyvoulou and Pickard2021; Nussio, Reference Nussio2020). This also means that our estimates are relatively more conservative as a lot of variation in the outcome variable is absorbed by the lagged value.

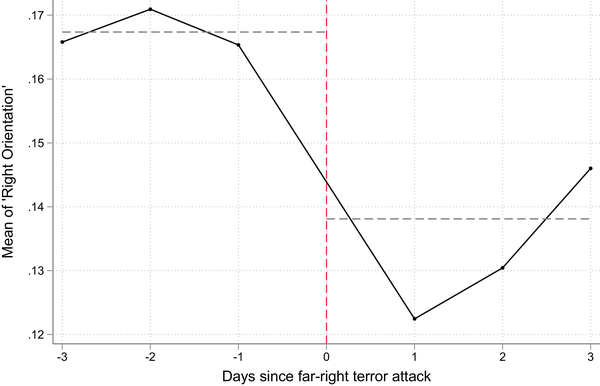

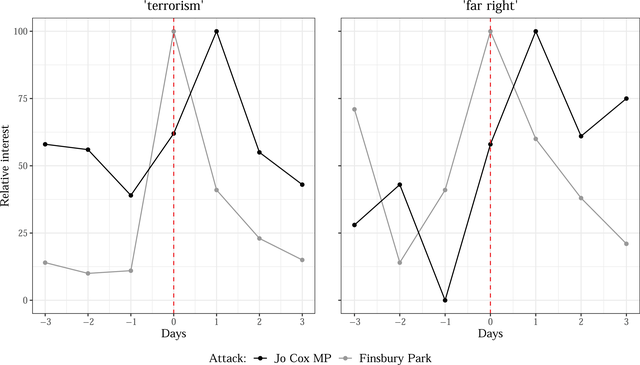

Figure 2 shows the share of respondents classifying themselves as ‘right’ (based on the definition above) before and after our sampled far-right terrorist attacks. A visual inspection of this figure provides some first evidence that, after this type of attack, people are more likely to distance themselves from the ‘right’ ideology. We now turn to a more systematic analysis of the causal relationship.

Figure 2. Share of respondents classifying themselves as ‘right’. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The figure reports the daily mean of ‘Right Orientation’ before and after the two sampled attacks.

Empirical findings

Main results

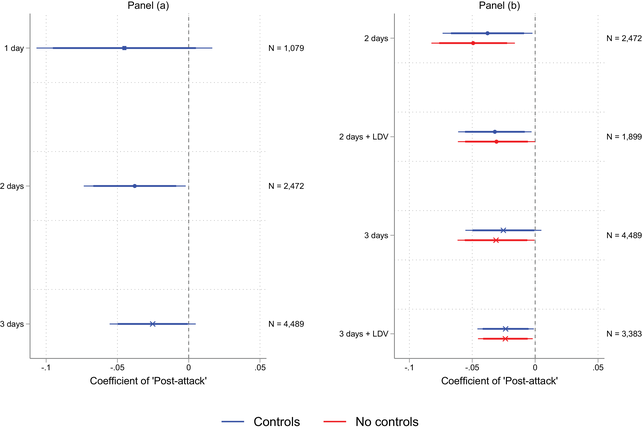

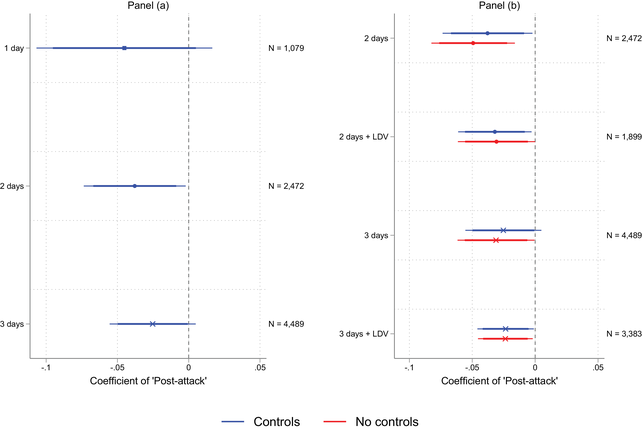

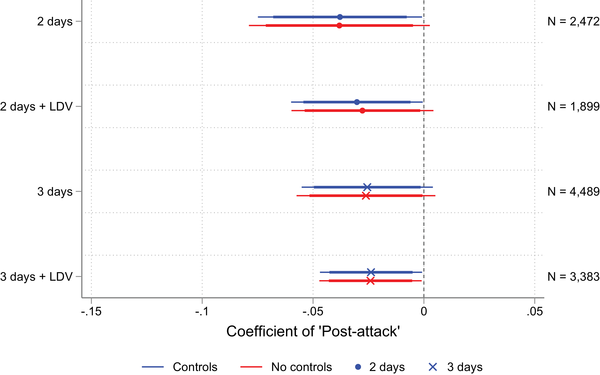

Panel (a) of Figure 3 presents the results from estimating Equation (1) using a linear probability model, based on 1, 2 and 3 days' bandwidths; that is, when we compare individuals interviewed within 1 day, 2 days and 3 days after the attacks with those interviewed within 1 day, 2 days and 3 days before the attacks, respectively. The results confirm that exposure to far-right terrorism shifts citizens' ideological self-placement away from the ‘right’ ideology. Specifically, the point estimates suggest that, after the attacks, ‘Right Orientation’ decreases by 0.02 to 0.04 points on a 0–1 scale; that is, a decrease that amounts to 10 per cent of the standard deviation of the variable. As expected, the estimates are less precisely estimated for the 1-day set-up due to the small sample size (low statistical power), which is one of the downsides of using very narrow bandwidths (Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020). For this reason, and also to account for the fact that the terrorism effect may take more than 24 hours to unfold, our inferences are based on the 2- and 3-days' bandwidths. Panel (b) of Figure 3 investigates the sensitivity of these (baseline) results to excluding the control variables in vector

![]() $\mathbf {Z}_{irw}$, and augmenting Equation (1) with the lagged dependent variable (LDV). The effect of terrorism remains negative, statistically significant, and stable in size across specifications, which is quite reassuring as regard to biases arising from pre-existing trends and the omission of unobserved characteristics.

$\mathbf {Z}_{irw}$, and augmenting Equation (1) with the lagged dependent variable (LDV). The effect of terrorism remains negative, statistically significant, and stable in size across specifications, which is quite reassuring as regard to biases arising from pre-existing trends and the omission of unobserved characteristics.

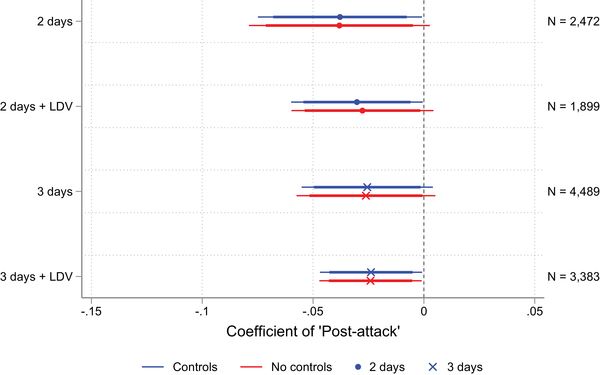

A threat to our identification strategy is that individuals with specific characteristics may respond to the survey at different points in time, and these characteristics may be predictive of the outcome. To further support our causal claims, we rely on entropy balancing to pre-process the data and produce covariate balance between the treatment and control groups (Hainmueller, Reference Hainmueller2012). As shown in Figure 4, re-weighting the sample through entropy balancing produces similar main results as in Figure 3 (panel (b)).

Figure 3. The effect of far-right terrorism on people's right orientation. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The dependent variable is ‘Right Orientation’. All specifications include region-by-wave fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the region level. Thick (thin) lines signify the 90 per cent (95 per cent) confidence interval.

Figure 4. Entropy balancing. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Estimates are balanced using entropy weights that match the mean, variance and skewness of covariates across the treatment and control units. (See also notes of Figure 3.)

Further insights

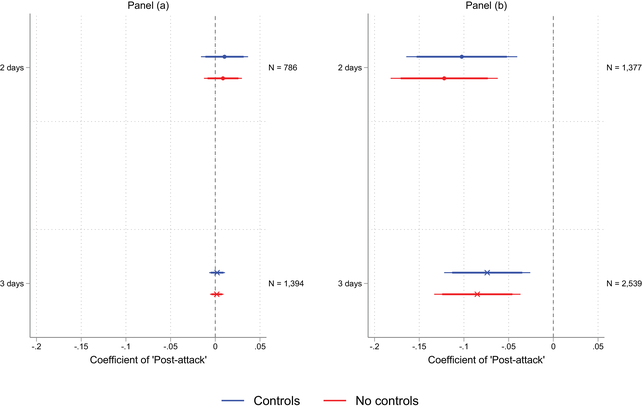

Our theoretical expectation in Section 1 relies on the argument that individuals of right-wing ideology share some diluted versions of the same ideas promoted by far-right terrorists. As such, the (observed) terrorism-induced effect on ‘Right Orientation’ should be exclusively driven by individuals with broader right-wing positions. In order to test for this, we split the sample of respondents into a left-wing constituency and a right-wing constituency (values 0–4 and 6–10, respectively, on the left-right scale), and run the same regression set-up as in Equation (1). To ensure that the results are not subject to post-treatment bias, we create the two groups based on information from the previous survey wave. The corresponding evidence, presented in Figure 5, lends support to the above interpretation: the treatment estimates for the right-wing constituency (panel (b)) are highly statistically significant and twice as large (compared to the baseline results), whereas those for the left-wing constituency (panel (a)) are very close to zero and fail to reach statistical significance.

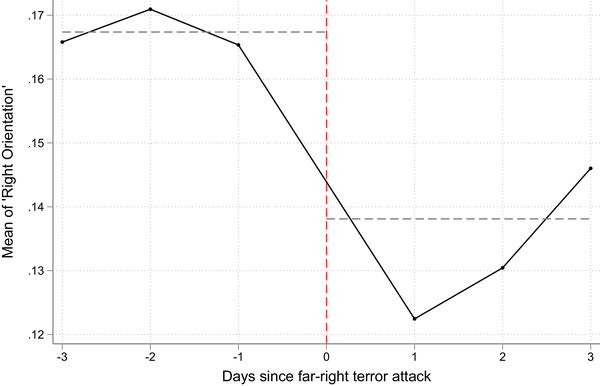

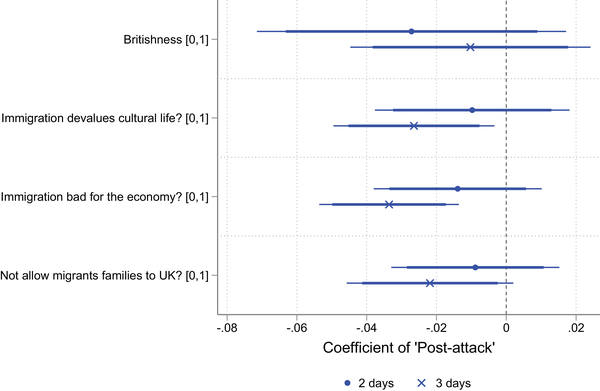

We next examine the impact of far-right terrorism on attitudes which are typically associated with far-right electoral support. To do so, we exploit information on the respondents' self-placement on a 1–7 ‘Britishness’ scale and their views towards immigration, as captured by their answers to ‘whether immigration enriches or undermines cultural life’, ‘whether immigration is good or bad for the economy’ and ‘whether the families of immigrants should be allowed (or not be allowed) to come to the UK’ – ranging from either 1 to 7 or 1 to 10, with higher values indicating more pro-immigration attitudes. We then construct four binary indicators of right orientation – taking value 1 for the top 25 percentile of the responses in the ‘Britishness’ question and the bottom 25 percentile of the responses in each one of the immigration questions – and run the same analysis as before. The corresponding results, reported in Figure 6, suggest that exposure to far-right terrorism does not only affect individuals' self-positioning towards the right end of the political spectrum but also makes them less likely to attest strong national identity and to report immigration scepticism. These results run counter to previous studies on how (Jihadi-inspired) terrorism generates negative perceptions of immigrants (see, e.g., Böhmelt et al., Reference Böhmelt, Bove and Nussio2020; Ferrín et al., Reference Ferrín, Mancosu and Cappiali2020; Legewie, Reference Legewie2013). Given the ‘tendency in academic scholarship, just as in popular discourse, to focus on negative attitudes towards immigrants’ (Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Simon, Hudson and VanHeerde Hudson2019, p. 18), our findings here highlight some of the conditions under which attitudes towards immigrants can actually become less hostile.

Figure 5. The effect of far-right terrorism on people's right orientation: left-wing versus right-wing constituencies [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Panel (a) shows the effects for the left-wing constituency (values 0–4 on the left-right scale) and panel (b) for the right-wing constituency (values 6–10 on the left-right scale). (See also notes of Figure 3.)

Figure 6. The effect of far-right terrorism on people's perceived national identity and attitudes about immigration. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: The dependent variable is listed on the vertical axis. All specifications include region-by-wave fixed effects and controls. The 2-day (3-day) sample sizes (from top to bottom) are 2,014 (3,372); 4,095 (7,185); 4,056 (7,123); and 3,919 (6,881). Standard errors are clustered at the region level. Thick (thin) lines signify the 90 per cent (95 per cent) confidence interval.

The results in Figure 6 can also address, to some extent, the possibility that our key outcome variable is susceptible to misreporting; that is, survey participants falsify their preferences after the attacks to look as if they don't hold a far-right political identity. Even though it is not possible to distinguish between ‘honest’ and ‘dishonest’ answers – and rule out the possibility of social desirability being one potential mechanism – the fact that we find consistent effects across a range of different outcomes suggests that there are at least some genuine shifts in citizens' ideological stance following the attacks. This is also corroborated by the fact that we employ data from an online survey, a survey mode that has been shown to reduce social desirability bias in responses on sensitive topics compared to face-to-face interviews (Blinder et al., Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2019; Kreuter et al., Reference Kreuter, Presser and Tourangeau2008).

Finally, one may ask whether exposure to far-right extremism can affect ideological scores through other channels. For instance, one may argue that, in the wake of the attacks, citizens move away from both extremes of the political spectrum and take more moderate positions – and thus converge towards more centrist attitudes. In Section C.1 of the online Appendix, we experiment with alternative specifications of the outcome variable to test for the existence of other types of terrorism-induced shifts in political orientation. The estimates of ‘Post-attack’ fail to reach statistical significance when we employ a binary indicator capturing ideological self-placement at the left end of the political spectrum and when we consider the continuous version of the outcome variable based on the full left-right scale. This suggests that neither the effect is ‘across-the-board’ – that is, far-right terrorism causing similar shifts within the entire political spectrum – nor there seems to be evidence of ‘deradicalization’ with individuals on the left taking more moderate positions.

Additional analyses and robustness checks

Online Appendix C presents additional analyses and robustness checks. In Section C.1, we show that our inferences do not change when ‘Right Orientation’ is re-coded to reflect more extreme right positions. In Section C.2, we employ the same empirical design to examine the impact of attacks motivated by Jihadi extremism. The results reinforce the argument that the two types of terrorism (far-right vs. Jihadi-inspired) elicit changes in ideological positions in the opposite direction. In Section C.3, we explore the conditionality of the effects on geographic distance. We find that the reported terrorism-induced shift in right orientation is relatively stronger for individuals living nearby targeted areas. In Section C.4, we re-estimate Equation (1) separately for each of the two far-right attacks. In both cases, we find that individuals are less likely to report a ‘right’ ideological score after being exposed to an attack; even though the effects appear to be shorter-lived for the murder of MP Jo Cox (see also online Appendix A.2 for a discussion). In Sections C.5 and C.6, we perform placebo tests based on alternative outcomes and alternative attack dates. None of the placebo tests return statistically significant estimates, providing further credibility to our results. Finally, in Sections C.7 and C.8, we show that the reported effects persist when we use a probit model, and when we employ matching techniques as an alternative approach to deal with imbalances in the treatment and control groups.

Conclusions

Does extreme right-wing terrorism cause ideological shifts? If so, in which direction? Given the incidence of far-right terrorism and the success of radical right parties and actors in many democracies, this research shows that far-right extremism does elicit changes in political views among the domestic audience but perhaps not in the intended direction: we find that far-right terrorism causes shifts away from ideological positions at the right end of the political spectrum. At the same time, it does not affect the political orientation of individuals on the left. One popular theoretical perspective on how terrorism affects political beliefs is offered by the terror management theory. This theory predicts that death-related threats motivate individuals to seize upon whatever political ideology has served their needs in the past, be it liberal or conservative, thus reinforcing extant political beliefs. Our results do not seem to offer empirical support to this perspective.

As the general public has moral issues with violence tactics and is unlikely to justify violence, we argue that citizens are expected to be less likely (after the attacks) to support or identify with the goals of the perpetrator. As such, the use of violent tactics can erode the popular support for the ideology associated with the perpetrator of violence. If this is the case, citizens should also distance themselves from some of the core values of the perpetrators and their political views. As radical right-wing movements claim that non-native elements are threatening the homogeneity of the nation state, we show that terrorist violence can actually decrease nationalistic attitudes and trigger more tolerance, rather than more hostility, towards out-groups. Previous studies have usually focused on one attitude and shown that (Islamic) extremism benefits conservative parties, increases nationalism or leads to more negative attitudes towards immigration. We find effects in the opposite direction, and following a far-right terrorist incident, respondents are more likely to voice political views in opposition to those of the perpetrator. In other words, far-right political violence leads to a relatively wide reduction in support for key right-wing extremist attitudes. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the characteristics of perpetrators and their driving goals cannot be ignored for a more nuanced understanding of the audience's reception and consequences of terrorist attacks.

Important avenues for future research can emerge out of our work. For one, the United Kingdom lacks a viable far-right party as the radical right has traditionally been associated with failure. As this might point towards some sort of the uniqueness of the UK case, it would be interesting to investigate whether the results would be similar in countries with more successful far-right parties, like France or Germany. Our study suggests that far-right political violence could actually provoke positional shifts away from some of the most contentious political views associated with popular parties, such as the National Front in France. There are specificities to the UK case, as in all single-case studies, and we hope that future studies will be able to leverage a more extensive dataset and embed a quasi-experimental approach in a comparative design, so as to increase external validity.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC Grant number: ES/V002333/1). For the purpose of open access, the authors have applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising. The authors wish to thank Selim Erdem Aytaç, Jessica Di Salvatore, Marco Giani, Albert Falcó-Gimeno, Arzu Kibris, Devorah Manekin, Enzo Nussio and Andrea Ruggeri for helpful comments and suggestions. We are also indebted to the participants of the Empirical Studies of Conflict Project (ESOC) Annual Meeting, the Annual Jan Tinbergen European Peace Science Conference and the workshop on “The effects of terrorism and violence in political behaviour” at the University of Barcelona. The usual disclaimer applies.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Figure B.1: Terrorist attacks in Great Britain, 2006–2018

Figure B.2: Timeline of events

Figure B.3: Newspaper front pages from the day after the attacks

Figure B.4: The effect of far-right terrorism on people's perceptions about the ‘most important issue'

Table B.1: Summary statistics (3-day sample) and definitions for all model variables

Figure B.5: Ideological self-placement on the left-right scale of the political spectrum

Table B.2: Covariate balance

Table B.3: Covariate balance after entropy weighting

Table B.4: Full regression results for panel (a) of Figure 3

Table B.5: Full regression results for panel (b) of Figure 3

Figure B.6: The effect of a far-right terrorism on people's beliefs about traditional British values

Figure C.1a: The effect of far-right terrorism on people's right orientation: alternative definition

Figure C.1b: The effect of far-right terrorism on people's left orientation

Figure C.1c: The effect of far-right terrorism on people's left-to-right orientation: continuous variable

Figure C.2: The effect of Jihadi-inspired terrorism on right orientation

Figure C.3: The conditional effect of distance

Figure C.4: The effect of far-right terrorism on people's right orientation: individual attacks

Figure C.5: The effect of far-right terrorism on placebo outcomes

Figure C.6: The effect of far-right attacks on people's right orientation: placebo attack dates

Figure C.7: The effect of far-right terrorism on people's right orientation: probit estimation

Figure C.8: The effect of far-right terrorism on right orientation: coarsened-exact matching

Supplementary material