Introduction

Contemporary Western democracies face widespread dissatisfaction with politics: Many citizens today express scepticism and low confidence in representative institutions (ESS Round 9, 2018; Norris, Reference Norris2011). Against this backdrop, academics and practitioners increasingly examine ways of involving citizens in the political decision-making process, such as deliberative minipublics (Dryzek et al., Reference Dryzek, Bächtiger, Chambers, Cohen, Druckman, Felicetti, Fishkin, Farrell, Fung, Gutmann, Landemore, Mansbridge, Marien, Neblo, Niemeyer, Setälä, Slothuus, Suiter, Thompson and Warren2019; Escobar & Elstub, Reference Escobar, Elstub, Elstub and Escobar2019; OECD, 2020). These consist of tens or hundreds of citizens who are selected on a random basis and who assemble to learn, discuss and formulate recommendations on a political issue (Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006; Smith, Reference Smith, Geißel and Newton2014).

The question whether minipublics can address political discontent has received more and more scholarly attention (Escobar & Elstub, Reference Escobar, Elstub, Elstub and Escobar2019). While most work to date focuses on the participants in deliberative forums (e.g., Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019; Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund, Setälä and Herne2010), recent studies have started to uncover that minipublics can also boost political support among the wider public (e.g., Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018; Jacobs & Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021). This suggests that the effects of deliberative forums can be ‘scaled up’ to the public at large and points to a potentially broader role of minipublics in generating political support (Knobloch et al., Reference Knobloch, Barthel and Gastil2020; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018). Overall, previous works tend to be optimistic about minipublics’ potential to tackle widespread dissatisfaction with politics (Spada & Ryan, Reference Spada and Ryan2017; van der Does & Jacquet, Reference van der Does and Jacquet2021).

It may, however, be of major relevance to take into account how political decision makers deal with minipublics’ recommendations. The advisory nature of minipublics raises concerns that governments ‘cherry-pick’ recommendations that align with their political agenda and disregard those that do not (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Curato, Dryzek, Geißel, Grönlund, Marien, Niemeyer, Pilet, Renwick, Rose and Setälä2019; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017; Smith, Reference Smith, Geißel and Newton2014). In practice, most deliberative forums do not see their list of recommendations fully implemented (Font et al., Reference Font, Smith, Galais and Alarcon2018; OECD, 2020). This could have important ramifications for citizens’ reactions to a minipublic: When the government dismisses a minipublic's advice, citizens may become more dissatisfied with politics compared to when the government would not have asked for this input in the first place (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019; Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing, Theiss-Morse, Sullivan, Snyder and Sullivan2008; Irvin & Stansbury, Reference Irvin and Stansbury2004; Ulbig, Reference Ulbig2008).

Yet, we only have a limited understanding of the role that deliberative minipublics can play in building political support among the public at large (van der Does & Jacquet, Reference van der Does and Jacquet2021), and little is known about the possibility of the use of minipublics backfiring (Spada & Ryan, Reference Spada and Ryan2017). Specifically, it remains largely unclear what happens when we take account of differences in the impact of minipublics on political decision making. This study innovates by empirically examining whether and how the effect of a minipublic on political support among the general public varies depending on the government's adoption of the recommended policies.

We present original empirical evidence from a pre-registered online survey experiment (n = 3,102) in Belgium, a small Western-European democracy that has some experience with deliberative forums (Vrydagh et al., Reference Vrydagh, Devillers, Talukder, Jacquet and Bottin2020). The vignette presents respondents with a hypothetical, government-initiated minipublic tasked to produce recommendations in the domain of mobility – thus making respondents hypothetical non-participants. Following exposure to a condition wherein the government fully, partially or does not adopt the minipublic's recommendations, we measure respondents’ political support through judgements of the decision maker, the process and its outcome. In placebo conditions, respondents are exposed to decision making by the government on the same issue, whereby policy making took its course without input from a minipublic. This allows us to contrast respondents’ level of political support depending on variations in the adoption of a minipublic's advice and compared to a representative process. We moreover examine the effect of getting one's preferred outcome – that is, of the match between respondents’ preferences and the adopted policies.

This study adds to the academic debate on deliberative minipublics in three ways. First and foremost, this study contributes to the broader question of whether and under what conditions minipublics can address or aggravate dissatisfaction with contemporary politics (Escobar & Elstub, Reference Escobar, Elstub, Elstub and Escobar2019). Second, this study extends the scope of research on minipublics by varying whether the government adopts the recommended policies. In doing so, it takes a step towards comprehending the complexity of political decision making, in which minipublics are but one input in a broader process (Parkinson, Reference Parkinson2006; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017). Third, the empirical literature on minipublics has mostly focused on the participating citizens in deliberative forums (e.g., Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund, Setälä and Herne2010). This study ties in with recent efforts to examine to what extent minipublics can affect the attitudes of the general public (e.g., Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018; Knobloch et al., Reference Knobloch, Barthel and Gastil2020). In sum, this study takes an important step towards a better understanding of whether and how policy adoption shapes the effect of minipublics on political support among the general public.

Theoretical framework

Literature review

Deliberative minipublics are composed of tens or hundreds of citizens selected on a (stratified) random basis. The participating citizens receive information from experts and engage in facilitated small-group discussions before formulating collective judgements or recommendations on the issue(s) at stake. Well-known forms of minipublics are citizens’ juries, consensus conferences and citizens’ assemblies, among others (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Curato, Dryzek, Geißel, Grönlund, Marien, Niemeyer, Pilet, Renwick, Rose and Setälä2019; Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017; Smith, Reference Smith, Geißel and Newton2014).

Over the past years, minipublics have been on the rise (Dryzek et al., Reference Dryzek, Bächtiger, Chambers, Cohen, Druckman, Felicetti, Fishkin, Farrell, Fung, Gutmann, Landemore, Mansbridge, Marien, Neblo, Niemeyer, Setälä, Slothuus, Suiter, Thompson and Warren2019; OECD, 2020; Paulis et al., Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2020). A commonly suggested reason for this popularity is the expectation that minipublics can address public discontent with politics (Escobar & Elstub, Reference Escobar, Elstub, Elstub and Escobar2019; Font & Blanco, Reference Font and Blanco2007; OECD, 2020). This is considered as a pressing concern in contemporary Western democracies: Many citizens express low trust in representative institutions and are dissatisfied with the way democracy works (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004; ESS Round 9, 2018; Norris, Reference Norris2011). Against this backdrop, the empirical question arises whether minipublics indeed increase political support among their participants and the wider public (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018, Reference Boulianne2019; Font & Blanco, Reference Font and Blanco2007; Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund, Setälä and Herne2010; Jäske, Reference Jäske2019). It is this latter that has received more scholarly attention lately: For minipublics to play a broader role in alleviating political dissatisfaction, their effect would need to extend to the public at large (Jacobs & Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021; Knobloch et al., Reference Knobloch, Barthel and Gastil2020; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018).

Recent studies tend to show that minipublics can boost political support among the general public, although effect sizes are mostly modest (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018; Jacobs & Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021; Jäske, Reference Jäske2019; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018). In doing so, the existing literature has delineated particular elements within the concept of political support that may change when deliberative forums are used (Dalton, Reference Dalton2004; Easton, Reference Easton1975). Specifically, hearing or reading about a minipublic can lead citizens to report higher levels of domain-specific trust in government (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018), to perceive the decision-making process as more fair (Jacobs & Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021; Jäske, Reference Jäske2019) and to be more willing to accept the resulting policies (Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018).

One important caveat is that these previous works either look at the effects of deliberative forums without taking into account differences in their impact on political decision making (Jäske, Reference Jäske2019) or examine a scenario wherein the decision makers adopted the minipublic's recommendations (Jacobs & Kaufmann, Reference Jacobs and Kaufmann2021; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018). Yet, this overlooks the complexity of political decision making and presents a one-sided view of minipublics’ impact on the broader political process (OECD, 2020; Spada & Ryan, Reference Spada and Ryan2017).

In practice, the political ‘uptake’ or impact of minipublics seems to vary case by case (Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017). The outcomes of deliberative forums are generally not binding and, instead, have an advisory nature – that is, actual decision making is left to elected representatives (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Curato, Dryzek, Geißel, Grönlund, Marien, Niemeyer, Pilet, Renwick, Rose and Setälä2019; Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017; Smith, Reference Smith, Geißel and Newton2014). Several scholars point out the possibility of governments ‘cherry-picking’ the recommendations that accord with their own political agenda and disregarding those that do not suit them well (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Curato, Dryzek, Geißel, Grönlund, Marien, Niemeyer, Pilet, Renwick, Rose and Setälä2019; Font et al., Reference Font, Smith, Galais and Alarcon2018; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017; Smith, Reference Smith, Geißel and Newton2014).

A few studies have mapped the impact of deliberative forums on policies. The OECD (2020) reports that about 4 in 10 minipublics saw all of their recommendations implemented, 5 in 10 saw part of them implemented and 1 in 10 saw none of them implemented (based on 55 cases). Focusing on citizen participation more generally, Font et al. (Reference Font, Smith, Galais and Alarcon2018) observe that the full list of recommendations was implemented for 1 in 10 cases, part of it was implemented for 8 in 10 cases and none of the recommendations were implemented for 1 in 10 cases (based on 39 cases in Spain). Although these works look at policy implementation specifically, this suggests that political decision makers do not fully follow through on minipublics’ advice in a considerable number of cases.

However, to date it remains largely unclear whether and how impact on political decision making shapes the effect of minipublics on political support among the public at large.

Why could minipublics build political support among the general public?

Different strands of literature suggest that providing citizens with the opportunity to express their viewpoints and interests to decision makers generates higher levels of political support. Participatory democrats argue that citizens should participate widely in decision making and that this elevates their willingness to accept decisions (Morrell, Reference Morrell1999). Procedural fairness scholars posit that having a voice in the decision-making process boosts citizens’ procedural fairness judgements and, in turn, their acceptance of decisions and support for political institutions (Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988; Thibaut & Walker, Reference Thibaut and Walker1975; Tyler, Reference Tyler1990; Tyler et al., Reference Tyler, Rasinski and McGraw1985; see MacCoun, Reference MacCoun2005 for a review).

This ‘voice effect’ is not necessarily limited to instances where citizens are in direct contact with decision makers themselves, and it may also occur when others do the speaking on their behalf (e.g., by lawyers in legal settings; Thibaut & Walker, Reference Thibaut and Walker1975; see also Gangl, Reference Gangl2003; Ulbig, Reference Ulbig2008). This is particularly relevant for minipublics, because by design these are limited in scale: Only a small number of citizens is selected to personally take part in a deliberative forum (Parkinson, Reference Parkinson2006).

Some scholars suggest that participants inside minipublics can be seen as ‘citizen representatives’ for those outside the forum (Warren, Reference Warren, Warren and Pearse2008). Minipublics are composed of citizens who are selected on a (stratified) random basis, so they broadly reflect the population at large (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Curato, Dryzek, Geißel, Grönlund, Marien, Niemeyer, Pilet, Renwick, Rose and Setälä2019; Smith, Reference Smith, Geißel and Newton2014). The wider public may therefore perceive the minipublic participants to be ‘ordinary’ citizens and ‘people like me’ (Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Johnston, Carty, Blais, Patrick, Warren and Pearse2008; Gastil et al., Reference Gastil, Rosenzweig, Knobloch and Brinker2016; Pow et al., Reference Pow, van Dijk and Marien2020). This perceived likeness is found to influence citizens’ support for minipublics and their willingness to accept the outcomes (Pow et al., Reference Pow, van Dijk and Marien2020). What is more, due to minipublics’ learning and deliberative phases, the wider public may consider that the participants take the time and effort to become well-informed as well as to discuss and reflect on the issue(s) at stake (Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Johnston, Carty, Blais, Patrick, Warren and Pearse2008; MacKenzie & Warren, Reference MacKenzie, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012; Warren & Gastil, Reference Warren and Gastil2015). Taken together, citizens outside the forum may identify with the participants (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018) and/or trust them to come up with good recommendations on their behalf (Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Johnston, Carty, Blais, Patrick, Warren and Pearse2008; MacKenzie & Warren, Reference MacKenzie, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012; Warren & Gastil, Reference Warren and Gastil2015). The wider public may, therefore, react to minipublics as an indirect, non-personal opportunity for having a voice in political decision making.

Why could having a (non-personal) voice boost citizens’ political support? According to procedural fairness scholars, citizens base their fairness judgements to a large extent on how they feel treated by decision makers (Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988; Tyler, Reference Tyler1990; see also MacCoun, Reference MacCoun2005). This ‘relational’ or ‘value expressive’ strand argues that citizens appreciate decision makers who are honest, respectful, caring, polite and benevolent (Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988; Tyler, Reference Tyler1990). As argued by Werner and Marien (Reference Werner and Marien2018), minipublics could send informational cues to the general public about how the government behaves towards citizens. More precisely, when the government makes the effort and costs to set up a deliberative forum, this may be perceived as a signal that the government values and cares about citizens and their input. It is this signal that could bring about a boost in political support among the general public (Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018).

In short, hearing or reading about a deliberative minipublic may increase political support among the public at large.

Minipublics and their impact on political decision making

However, for deliberative forums to build political support, it may not suffice that they provide input in the political decision-making process. On the contrary, what happens after the minipublic presented its recommendations could be of major importance (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019). As Ulbig (Reference Ulbig2008) puts forward, ‘[i]t takes more than just having a say’ (p. 535) and it may be crucial that voice and input are coupled to influence and impact (see also Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing, Theiss-Morse, Sullivan, Snyder and Sullivan2008; Smith & McDonough, Reference Smith and McDonough2001). A lack of impact on political decision making may fundamentally change the public's reactions to a minipublic in terms of political support (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019; Irvin & Stansbury, Reference Irvin and Stansbury2004).

The impact of a minipublic on political decision making could be perceived by the wider public as another informational cue about the way the government behaves towards citizens. First, a minipublic's impact on political decision making may be related to public perceptions of the honesty and sincerity of the decision maker, that is, of the government being genuine rather than strategic in its motives and intentions when asking for a minipublic's input (Cohen, Reference Cohen1985; Tyler, Reference Tyler1990). Second, the impact of a deliberative forum on political decision making could also be perceived by citizens as a signal about whether they are being treated with consideration, dignity and respect (Lind & Tyler, Reference Lind and Tyler1988; Tyler, Reference Tyler1990). When the government disregards a minipublic's advice, this may evoke a sense of disrespect and indifference towards citizens (Smith & McDonough, Reference Smith and McDonough2001). Taken together, a minipublic's (lack of) impact on political decision making could be of major relevance for the wider public's reactions to a deliberative minipublic in terms of political support.

Citizens will likely attach importance to the political ‘uptake’ of minipublics. In their study of Spanish cases, Font and Blanco (Reference Font and Blanco2007) indicate that participants wanted the government to take their concerns seriously and engage with their input (see also Smith & McDonough, Reference Smith and McDonough2001). This we foresee to apply to the public at large as well. We therefore expect that the effect of a minipublic on political support among the wider public will vary depending on the impact of its advice on political decision making.

Here, it is important to add that the political ‘uptake’ or impact of minipublics can manifest itself in various ways: Ranging from, for instance, its recommendations concretely being implemented to diffusely influencing the way political decision makers and/or citizens think about a particular issue (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Curato, Dryzek, Geißel, Grönlund, Marien, Niemeyer, Pilet, Renwick, Rose and Setälä2019; Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006). The focus of this study is on policy adoption, because it is a straightforward way in which impact can be attached to, or detached from, input (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017). This, in turn, does not reduce to the recommendations either being fully adopted or completely disregarded. In practice, for example, governments can adopt part, but not all, of the recommended policies (Font et al., Reference Font, Smith, Galais and Alarcon2018; OECD, 2020). In what follows, we therefore differentiate between full, partial and no adoption of a minipublic's recommendations by the government.

H1: When the recommendations of a deliberative minipublic are fully adopted, this results in higher political support than when the recommendations are partially adopted, which in turn results in higher political support than when the recommendations are not adopted.

A boost or blow to political support?

When the government adopts a minipublic's recommendations, this speaks to the argument that the organisation of a minipublic and the subsequent political follow-up convey to citizens that political decision makers respect and care about them and their input (Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018). Here, we expect citizens to become more supportive of the decision maker, the process and its resulting policies. Citizens are, hence, hypothesised to report higher levels of political support when they hear or read about a minipublic whose recommendations were fully adopted by the government, compared to a representative decision-making setting.

H2a: Taking notice of a deliberative minipublic whose policy recommendations are fully adopted by government leads to higher levels of political support compared to a representative decision-making process.

When the government disregards a minipublic's recommendations, this may have opposite effects on political support. The decision not to follow a minipublic's advice may signal to the wider public that the government is insincere, disrespectful and indifferent towards citizens (Cohen, Reference Cohen1985; Smith & McDonough, Reference Smith and McDonough2001). What is more, the organisation of a minipublic arguably ‘increases the stakes’ (Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing, Theiss-Morse, Sullivan, Snyder and Sullivan2008, p. 136). Despite their advisory format, the effort and costs made by the government to initiate a deliberative forum can be interpreted by citizens as an indication that it intends to listen to the recommendations (Font & Blanco, Reference Font and Blanco2007; Jäske, Reference Jäske2019; Knobloch et al., Reference Knobloch, Barthel and Gastil2020). Although the government does not de jure break the rules of the game when it dismisses a minipublic's advice, this may be viewed differently by the general public, who may perceive a de facto violation of what they perceive as the government's promise to listen to a minipublic's input. When expectations are not fulfilled, this is understood to generate dissatisfaction (e.g., relative deprivation theory in Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marien and Oser2017; or the expectancy-disconfirmation model in Seyd, Reference Seyd2015). Specifically, the increased expectations and subsequent failure to live up to them is suggested to bring about a ‘frustration effect’ whereby citizens become more discontent (Cohen, Reference Cohen1985; Folger et al., Reference Folger, Rosenfield, Grove and Corkran1979; Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing, Theiss-Morse, Sullivan, Snyder and Sullivan2008; Ulbig, Reference Ulbig2008).

This argument resonates with the findings of Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing, Theiss-Morse, Sullivan, Snyder and Sullivan2008). They conducted an experiment in which respondents are subjected to a money game. The decision maker gets to decide how to divide $20 amongst himself and the respondent, and the outcome is held constant at $17/$3, respectively (with the role of decision maker being pre-assigned to an associate rather than randomly allocated, as the respondents were led to believe). Respondents were randomly divided into two experimental groups, varying whether they could say something before the decision was made. Their findings indicate that citizens who had a voice opportunity react more negatively than those who did not: Respondents in the former experimental condition perceived the decision maker as less fair and were less satisfied with the decision. This leads Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (Reference Hibbing, Theiss-Morse, Sullivan, Snyder and Sullivan2008) to conclude that having a voice is ‘not just neutral, it is deleterious’ (p. 136) in a situation in which it is seemingly being ignored by a self-interested decision maker.

This ‘backfire’ hypothesis is echoed in the literature on deliberative minipublics. Various scholars suggest that when the government disregards a minipublic's recommendations, this may lead to disappointment and possibly more dissatisfaction compared to the government not asking for this input in the first place (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019; Font & Blanco, Reference Font and Blanco2007; Irvin & Stansbury, Reference Irvin and Stansbury2004; Setälä, Reference Setälä2017). While these studies often indicate this effect to occur among participants in the deliberative forum, we foresee it to apply to the general public. We therefore hypothesise that citizens report lower levels of political support when they hear or read about a minipublic whose recommendations were not adopted by the government, compared to a representative decision-making process.

H2b: Taking notice of a deliberative minipublic whose policy recommendations are not adopted by government leads to lower levels of political support compared to a representative decision-making process.

As previously mentioned, the impact of minipublics on political decision making does not reduce to a dichotomy: the government can also partially adopt the recommendations (Font et al., Reference Font, Smith, Galais and Alarcon2018; OECD, 2020). While one may argue this could boost political support because a minipublic's input is followed to some extent, the reverse can also be said. So, we will explore to what extent taking notice of a minipublic whose policy recommendations are partially adopted leads to different levels of political support compared to a representative decision-making process.

The role of outcome favourability

So far, we have focused on processes of political decision making. Yet, this is not to say that the resulting outcome can be put aside: It is important to consider whether deliberative forums affect political support irrespective of the favourability of decisions (Arnesen, Reference Arnesen2017; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2019; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2020). Multiple studies show that the way in which political decisions are arrived at matters both to winners and losers, and process effects can operate at least partially independent of outcome effects (Gangl, Reference Gangl2003; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2020). We therefore expect the previously hypothesised differences in political support to occur irrespective of the extent to which the adopted policies align with citizens’ preferences (i.e., across varying levels of outcome favourability).

H3: The hypothesised differences in political support levels depending on the use of a minipublic and its subsequent policy adoption will hold regardless of the extent to which respondents see their preferred policies adopted.

Data and methods

Research design

We conducted an online, between-subjects survey experiment in Belgium. The design was preregistered on AsPredicted.org (click here to access the preregistration; and see Appendix A of the Supporting Information for a description of minor deviations).

Respondents were randomly assigned to one of five experimental conditions. In the three treatment conditions, respondents were exposed to a scenario of a deliberative minipublic, subsequently differentiating the adoption of the recommended policies (full, no or partial policy adoption). In the two placebo conditions, respondents were exposed to representative decision making, without reference to citizens being directly involved in the process. The two placebo conditions vary in whether or not a broad round of consultation preceded the decision making, thereby enabling us to compare the minipublic conditions to representative decision-making processes with varying degrees of consultation.

To enhance the external validity of our experimental design, the stimulus material was designed in the format of newspaper articles. This is arguably a typical medium via which the wider public learns about a minipublic happening in their region or country (treatment conditions) or about the government having decided on policy measures (placebo conditions).

Sample

We used a convenience sample consisting of Flemish citizens from an ongoing opt-in panel coordinated by the University of Antwerp. Panel members participate in maximum four surveys per year to avoid overburdening them. Flanders is the largest region of Belgium, a Western-European consensus democracy with highly devolved powers to its regions (Deschouwer, Reference Deschouwer2012). The survey experiment was fielded in Qualtrics between 8 June and 13 July 2020, and 5,906 panel members were successfully invited via email.Footnote 1 In total, 3,102 respondents completed the surveyFootnote 2 and 2,122 of them complied with the experimental treatment (compliance rate = 68.4 per cent).Footnote 3

The sample, and the panel in general, over-represents male, older, higher educated and politically interested citizens (see Appendix B of the Supporting Information for a comparison of the sample and the Flemish population on gender, age and education level). Despite observed biases, our sample is composed of a relatively diverse set of respondents. A probability-based sample that is representative of the Flemish population would allow for a more comprehensive test, especially with regards to heterogeneous treatment effects and the uncertainty whether certain subpopulations react differently (Coppock, Reference Coppock2019; Mullinix et al., Reference Mullinix, Leeper, Druckman and Freese2015). Still, our sample offers sufficient variation across demographics to allow a test of whether deliberative forums can boost political support among the general public as well as to take a first step towards uncovering whether the use of minipublics can backfire.

Topic and setting

We chose mobility as a theme for the hypothetical minipublic for the following reasons. Firstly, judging from the 2019 election programmes, Flemish political parties seem to agree on the importance of measures towards a more efficient and better performing mobility in its entirety. This is also reflected in the Flemish coalition agreement.Footnote 4 Second, despite these pledges, mobility has been a concern for years in Flanders (Vanparijs et al., Reference Vanparijs, Int Panis, Meeusen and de Geus2016; Wolf & Van Dooren, Reference Wolf and Van Dooren2018). This, in combination with an actual citizens’ panel on mobility in Brussels in 2017 (Vrydagh et al., Reference Vrydagh, Devillers, Talukder, Jacquet and Bottin2020), makes the hypothetical decision of the Flemish government to engage citizens on this issue more realistic. Third, mobility is a policy domain on which decisions tend to have a tangible impact on citizens’ everyday lives. For example, car-free zones in city centres, expansion of the public transport offering, investments in road infrastructure for bicycles and cars (and the accompanying road works) are experienced directly by citizens. As such, mobility is a highly obtrusive issue, increasing the possibility that citizens can make informed assessments amongst policy alternatives. Finally, competences on mobility have been decentralised to the regions, enabling us to present a policy setting that can feasibly be dealt with within the Flemish region.

Case

Belgium, and Flanders specifically, has some experience with deliberative minipublics (Vrydagh et al., Reference Vrydagh, Devillers, Talukder, Jacquet and Bottin2020). A well-known example is the G1000, a bottom-up initiative organised in 2011 comprised different deliberative elements, including a national citizen summit (Caluwaerts & Reuchamps, Reference Caluwaerts and Reuchamps2018). More recently, minipublics have been used at the regional level, in particular in the Walloon and Brussels region and the German-speaking community (Vrydagh et al., Reference Vrydagh, Devillers, Talukder, Jacquet and Bottin2020). In Flanders, this remains at fewer instances (Vrydagh et al., Reference Vrydagh, Devillers, Talukder, Jacquet and Bottin2020) and a concrete proposal for bottom-up minipublics was rejected by the Flemish parliament in 2018 (Van Crombrugge, Reference Van Crombrugge2020). From a comparative perspective, the number of minipublics in Belgium falls below that of those at the vanguard in Europe such as Ireland or the United Kingdom, yet it is higher than in several other countries (OECD, 2020; Paulis et al., Reference Paulis, Pilet, Panel, Vittori and Close2020).

Experimental design

The survey experiment was structured as follows. In the pre-treatment stage of the survey, we asked respondents several questions including their gender, age, education level and region of residence (see Appendix C of the Supporting Information for item formulations; Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery, Nyhan and Torres2018). We also introduced the topic of mobility to respondents, stating it has been subject to debate in Flanders in recent years. Respondents were told that different policy measures can be taken in this domain, but not all can be carried out because of, for instance, budget restraints. We then presented respondents with a list of eight policy measures in randomised order (e.g., investing in bicycle lanes, train infrastructure, etc.) and asked them which policies they would prefer. Respondents were instructed to rank the policy measures from most to least preferred (see Appendix C of the Supporting Information for the full list of policy measures). Independent of respondents’ answer to this drag-and-drop question, the eight presented policy measures constituted the pool from which the vignettes randomly drew policies.

Next, respondents were randomly assigned to one of five experimental conditions (see Appendix C of the Supporting Information for the vignettes). In three treatment conditions, respondents read about a hypothetical government-initiated minipublic that had recently taken place in Flanders on the theme of mobility. In a newspaper article format, respondents were informed about (a) the gathering of 50 randomly selected Flemish citizens, (b) initiated by the Flemish government, (c) to discuss how to spend €10 million extra budget reserved for this year to be additionally invested in mobility, (d) in different sessions consisting of expert presentations, small-group discussions and an anonymous vote, (e) resulting in a recommendation of two policy measures to be presented to the Flemish government. It is, moreover, stated that the minipublic's recommendations are not legally binding and that the government is not obliged to adopt them. Two mobility measures, randomly drawn from the pool of eight policy measures, were selected and shown as being recommended by the minipublic.

Subsequently, respondents were informed about the minipublic's impact on political decision making, again in a newspaper article format. They were told that the government decided to either follow both recommendations of the minipublic (full policy adoption; condition 1), not to follow the recommendations and instead opted for two different policy measures (no policy adoption; condition 2) or to follow one of the two policies proposed by the minipublic and decided on one alternative policy measure (partial policy adoption; condition 3). Further combinations of mobility measures were thus shown to respondents. For example, in condition 3, one of the two recommended policies was randomly presented as being adopted and the other, alternatively adopted policy was randomly drawn from the pool of six non-recommended measures.

In two placebo conditions, respondents read a hypothetical newspaper article about a representative process, wherein no reference was made to a minipublic (i.e., the government decided on policy measures). The two placebo conditions differed in the extent of consultation. Respondents were told that either the government internally discussed the policy measures (low consultation; condition 4), or that a broad round of consultation with experts and interest groups preceded the decision (high consultation; condition 5). The underlying reason for differentiating two placebo conditions is to avoid creating a false dilemma between a minipublic engaging in deliberation preceding their advice and the government merely reaching a decision (without explicating a consultation phase, including the involvement of experts). By explicitly stating the consultative phase in one of the placebo conditions, we can more confidently reach conclusions on the effect of a minipublic compared to ‘politics-as-usual’ rather than of the former's deliberative nature only.

Measurements

In both treatment and placebo conditions, respondents were then asked a set of questions to measure their level of political support. We measure political support using several indicators, presented in a randomised order. Respondents were asked to evaluate (i) the concerned decision maker, (ii) the decision-making process and (iii) its outcome.

Trust in the decision maker was specified to the Flemish government. We included a general measure asking ‘Could you indicate how much you trust the Flemish government?’. Additionally, we asked a domain-specific measure of trust in government by adding ‘…to take good decisions about mobility?’ to the previous formulation (1 = ‘No trust at all’; 7 = ‘Complete trust’; adapted from Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018; ESS Round 9, 2018). This allows us to see whether a one-instance decision-making process can have effects on government trust related to the policy domain as well as on more general levels of trust in government.

We use the following question to tap into respondents’ procedural fairness judgements: ‘If you think about the way in which the decision on the mobility measures was taken, to what extent do you think the decision-making process was… Fair/Good/Unjust/Inappropriate/Transparent?’ (1 = ‘Not at all’; 7 = ‘Very much so’) (adapted from Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2020). The items were presented in a randomised order. We reversely coded the negatively phrased items and created an index (Cronbach's alpha = 0.83).

Respondents’ willingness to accept the decision was asked as ‘How willing are you to accept the decision of the Flemish government on the mobility measures?’ (1 = ‘Not at all willing’; 7 = ‘Very willing’) (adapted from Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Persson, Gilljam and Lindholm2019).

The moderator outcome favourability was measured using the above described rank order question. We matched respondents’ answers to this question to the policies presented to them as adopted by the government in the hypothetical newspaper article. We recoded this score from 1 (the least favourable outcome possible) to 13 (the most favourable outcome possible).

Manipulation checks

Factual manipulation checks were included after respondents answered questions on political support (Kane & Barabas, Reference Kane and Barabas2019). To assess whether the experimental stimuli worked well, we computed independent samples t-tests (p < 0.05) comparing the experimental conditions. The manipulation checks proved successful (Table C1 of the Supporting Information), suggesting that respondents accurately perceived the presence of a minipublic (manipulation check 1), differences in the adoption of the minipublic's recommendations by the government (manipulation check 2), and differences between the level of consultation in the placebo conditions (manipulation check 3).

Methods

We use ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models. The results using the low consultation placebo condition are reported in the main text, and those using the high consultation placebo condition in Appendix D of the Supporting Information. Furthermore, the results for the full sample are included in the main text (intent to treat effects; Gerber & Green, Reference Gerber and Green2012; Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery, Nyhan and Torres2018). The effects for compliers only (complier average causal effects; CACE) can be found in Appendix E of the Supporting Information.

Results

A differential effect of a minipublic on political support

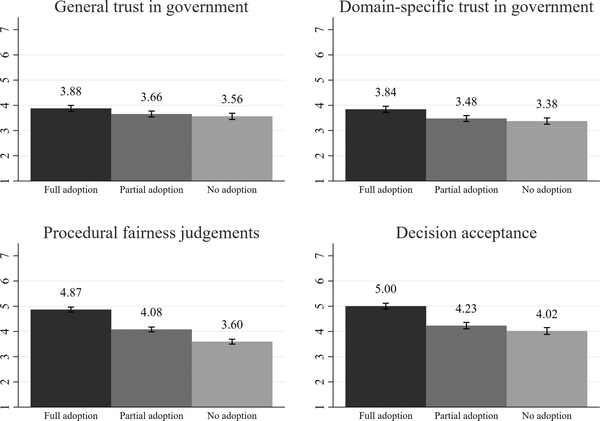

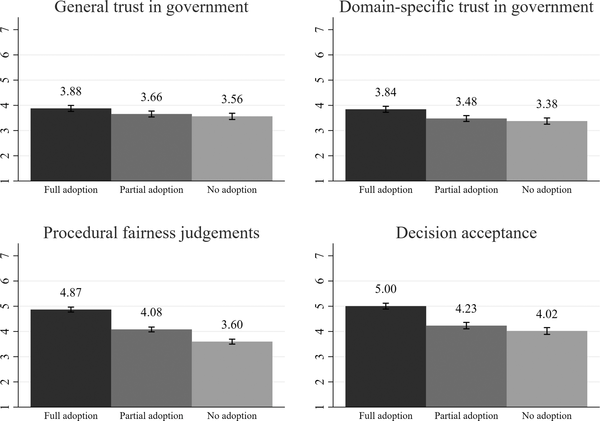

We begin by plotting the mean political support scores in the treatment conditions to see to what extent variations in the government's adoption of a minipublic's recommendations bring about different levels of political support (H1; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Political support across treatment conditions.

Note: Mean scores for political support (with 95 per cent confidence intervals in error bars). N = ∼620 per experimental condition.

When the government fully adopts the policies advised by the minipublic, this leads to higher levels of political support than when it does not or only partially follows the recommended policies. According to regression analyses, these differences are statistically significant (Table D1 of the Supporting Information). While they appear most outspoken for our process- and decision-specific measures, the effects on general and domain-specific trust in government are statistically significant as well.

Moreover, there is a difference between partial and no adoption of the minipublic's recommendations by the government. When the government does not adopt a minipublic's recommendations, this leads to lower levels of political support than when it partially follows its advice. Regression analyses confirm these differences to be statistically significant for procedural fairness judgements and decision acceptance, but not for either of our measures of government trust (Table D2 of the Supporting Information).

Hence, in line with our first hypothesis, differences in the adoption of a minipublic's recommendations bring about varying levels of political support. Full policy adoption leads to the highest levels of political support and no policy adoption to the lowest. Besides, partial policy adoption tends to lead to in-between levels of political support.

Compared to ‘politics-as-usual’

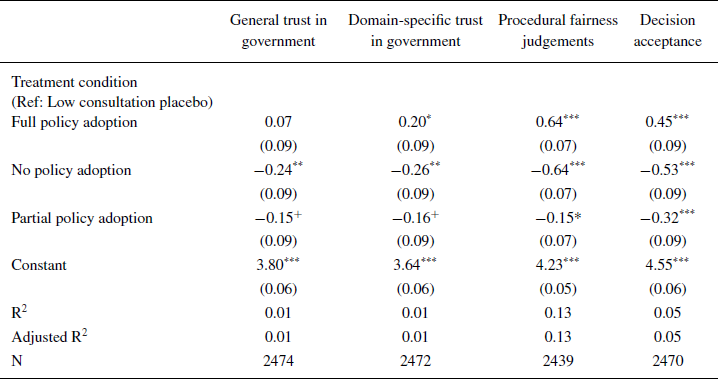

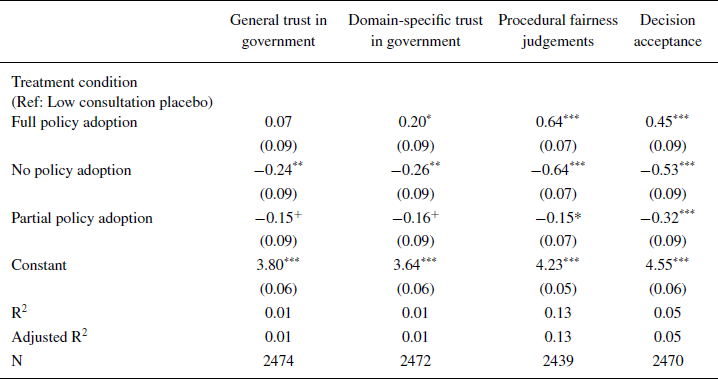

We now turn to the effect of a minipublic on political support compared to a setting wherein representative decision-making took its course without input from a deliberative forum (H2a and H2b; Table 1).

Table 1. OLS regression models of political support across experimental conditions

Note: Non-standardised regression coefficients, standard errors between parentheses. +p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Compared to a representative setting, a minipublic generates higher levels of domain-specific trust in government when its recommendations are fully adopted. This effect is modest in size: 0.20 points on a seven-point scale. The effects seem to be somewhat larger when looking at procedural fairness judgements and decision acceptance. A minipublic with full policy adoption leads respondents to perceive the process as fairer and to be more willing to accept the resulting policies compared to a representative decision-making process (by 0.64 and 0.45 points respectively, on seven-point scales). Although the direction of the results is as expected for general trust in government, this does not reach statistical significance.

The results are starkly different when examining a minipublic whose recommendations are not adopted by the government. When the government disregards its recommendations, a minipublic generates lower levels of general and domain-specific trust in government compared to representative decision making. These effects are, again, modest in size (0.24 and 0.26 points for general and domain-specific trust respectively, on seven-point scales). The effects appear somewhat more outspoken with regards to process- and decision-specific measures. When the government initiates a minipublic but does not follow its recommendations, this leads respondents to perceive the process as less fair and to be less willing to accept the final policies compared to a representative decision-making setting (by 0.64 and 0.53 points, respectively, again on seven-point scales).

When exploring what happens when the government adopts one of two policies recommended by the minipublic, there seems to be a modest effect on political support. When the government partially follows its advice, it appears that a minipublic brings about lower levels of political support compared to a representative decision-making process (by between 0.15 and 0.32 points on a seven-point scale). Due to the exploratory nature of this analysis, we have to be cautious in interpreting the significance levels (Smela, Reference Smela2019; Wagenmakers et al., Reference Wagenmakers, Wetzels, Borsboom, van der Maas and Kievit2012).

Finally, we look at our high consultation placebo condition as the reference category. When the representative decision making explicitly includes a broad round of consultation, the results are highly similar (Table D3 of the Supporting Information). One noteworthy difference, however, arises when looking at a minipublic with full policy adoption: Its effect on domain-specific trust in government is no longer statistically significant when we compare it to a representative setting with an explicit consultation phase.

In sum, in line with our second hypothesis, a deliberative minipublic tends to have positive effects on political support among the public at large when its recommendations are fully adopted. Compared to a representative setting, a minipublic with full policy adoption leads to higher levels of perceived procedural fairness, decision acceptance and, possibly, domain-specific trust in government. When it (partially) lacks policy adoption, however, a minipublic seems to have negative effects on political support among the wider public. Compared to representative decision making, a minipublic whose recommendations are not followed brings about lower levels of perceived procedural fairness, decision acceptance as well as general and domain-specific trust in government.

Process over outcome?

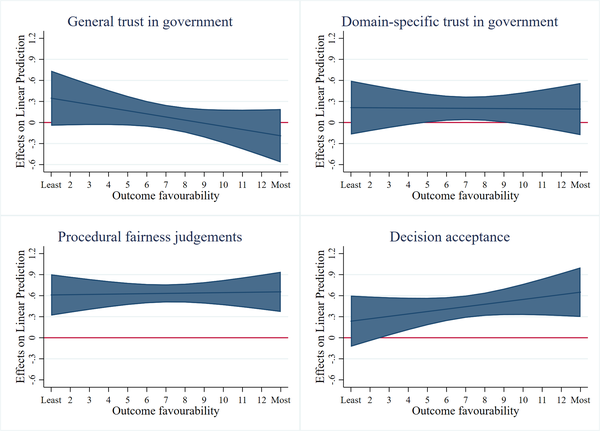

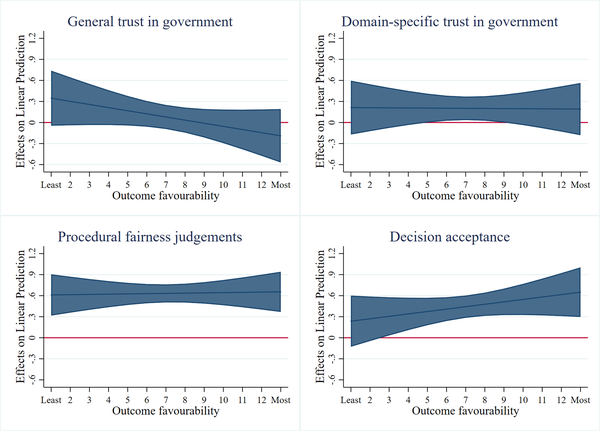

In a next step, we test whether the observed differences between experimental conditions occur irrespective of outcome favourability – that is, of the extent to which respondents’ preferred policies are adopted by the government (H3). To do so, we interact the experimental condition variables with the outcome favourability variable (see Appendix D of the Supporting Information for all interaction models).

We first turn to the effects of a minipublic with full policy adoption compared to representative decision making, per level of outcome favourability (Figure 2). For general trust in government, the effect of a minipublic is not statistically significant regardless of the favourability of the adopted policies to the respondent (confidence interval does not escape the horizontal zero-line). For domain-specific trust, the effect of a minipublic with full policy adoption is not statistically significant among respondents who receive either an unfavourable or a favourable outcome. For decision acceptance, the effect remains positive but is not statistically significant among respondents who face highly unfavourable policies. For procedural fairness judgements, moreover, the positive effect of a minipublic with full policy adoption is statistically significant across the range of outcome favourability.

Figure 2. Conditional marginal effects of low consultation placebo vs. full policy adoption conditions (with 95 per cent CI). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

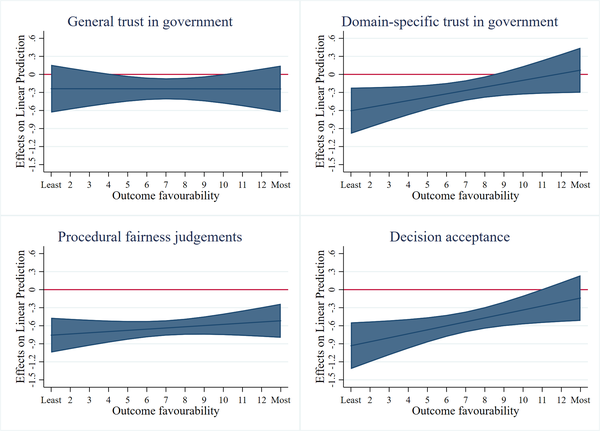

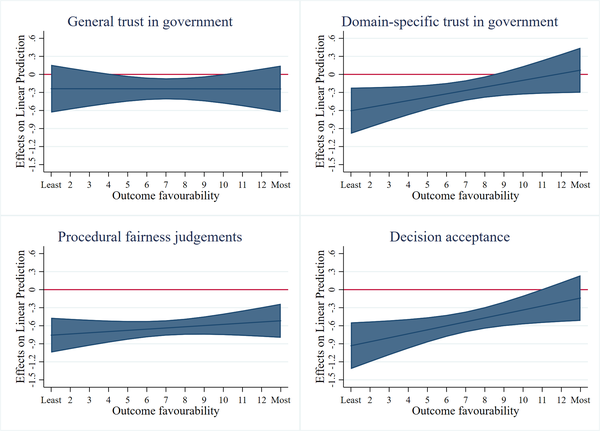

We next look at the role of outcome favourability for the effect of a minipublic without policy adoption compared to a representative process (Figure 3). For general trust in government, the effect is not statistically significant among respondents who receive either an unfavourable or a favourable outcome. For domain-specific trust and decision acceptance, the effect of a minipublic without policy adoption generally remains negative but is not statistically significant among respondents who are (very much) in favour of the adopted policies – which are, in this experimental condition, different from the ones proposed by the minipublic. For procedural fairness judgements, furthermore, the negative effect is statistically significant across the board of outcome favourability.

Figure 3. Conditional marginal effects of low consultation placebo vs. no policy adoption conditions (with 95 per cent CI). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In very general terms, we find that the difference between a decision-making process with or without a minipublic on political support is sometimes not statistically significant among respondents who face (highly) favourable or, conversely, (highly) unfavourable outcomes. A similar conclusion can be reached when looking at the interactions between the three treatment conditions and outcome favourability (Figures D1–D3 of the Supporting Information) as well as when using the high consultation placebo as the reference category (Figures D4–D5 of the Supporting Information). We thus do not find consistent support for our third hypothesis, stating the effect of a minipublic on political support among the wider public to be present across the range of outcome favourability.Footnote 5

Robustness checks

To assess the robustness of our results, we analyse the subset of respondents who complied with the experimental stimulus (CACE effects). When doing so, we come to similar conclusions. As can be expected, the observed effects are somewhat larger for compliers than for the full sample (Appendix E of the Supporting Information).

Conclusion

Recent years have seen an upsurge in the use of deliberative minipublics (OECD, 2020). One reason for this popularity, that is often put forward, is the expectation that minipublics can address widespread dissatisfaction with contemporary politics (e.g., Font & Blanco, Reference Font and Blanco2007). Recent studies indicate that hearing or reading about a minipublic can boost political support among the public at large (e.g., Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018; Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018). Yet, several scholars suggest that the government's response to a minipublic's advice could be of fundamental importance for citizens’ reactions to a minipublic: When the government disregards its recommendations, a minipublic may generate more political dissatisfaction than a ‘normal’ representative decision-making process (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019; Hibbing & Theiss-Morse, Reference Hibbing, Theiss-Morse, Sullivan, Snyder and Sullivan2008; Irvin & Stansbury, Reference Irvin and Stansbury2004; Ulbig, Reference Ulbig2008). However, we lack empirical insights into whether and when the use of minipublics may backfire.

In this study, we used an online survey experiment (n = 3,102) to examine the effect of a deliberative minipublic on political support among the general public when varying the government's adoption of the recommended policies. To begin with, our results indicate that a minipublic brings about higher political support when the government fully adopts its recommendations compared to partial or no adoption. Furthermore, when its advice is fully adopted by the government, we find that a minipublic leads to higher levels of perceived procedural fairness, decision acceptance and, possibly, domain-specific trust in government compared to a representative decision-making process. On the contrary, when the government does not adopt its recommendations, we observe that a minipublic generates lower levels of perceived procedural fairness, decision acceptance as well as general and domain-specific trust in government compared to a representative process. The observed effects seem modest in size for trust in government, while somewhat more outspoken for our process- and decision-specific measures of political support. Exploratory analysis indicates that when the government partially adopts a minipublic's recommendations, this likewise appears to bring about lower political support. Finally, when looking at outcome favourability, we find that the observed differences are sometimes statistically insignificant among respondents who face a (highly) (un)favourable outcome. Overall, this study indicates that the effect of minipublics on political support among the public at large varies depending on the government's adoption of its recommendations.

The implications of the presented findings are twofold. First, in line with earlier research, this study shows that hearing or reading about a minipublic can have effects on political support among the wider public. Even though they did not take part themselves, citizens outside the forum may adjust their level of political support in response to information about deliberative minipublics happening in their region or country. Second, the findings of this study demonstrate the importance of taking account of the broader context in which minipublics are embedded when studying their effects on political support (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2019; Font & Blanco, Reference Font and Blanco2007). Our study builds on the argument that the wider public considers how minipublics are dealt with by the government, as this conveys a signal whether political decision makers care about citizens and their input (Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018). Our finding that the ‘uptake’ of minipublics’ advice brings about variations in citizens’ political support underlines the importance of studying minipublics in relation to the broader context in which they take place.

Of course, our study has several limitations. The experimental design implies that our setting is, by definition, artificial and a simplification of both the complexity of minipublics as well as their connection to the political decision-making process. Non-experimental studies would substantiate our findings and could additionally shed light on, for instance, the durability of a minipublic's effect on political support over time. Furthermore, we use a convenience sample and, despite its diversity across demographics, this has several drawbacks. We invite future studies to use a probability-based sample and, amongst other things, tease out whether the observed effects of deliberative forums on political support occur across different subgroups in society (Coppock, Reference Coppock2019; Mullinix et al., Reference Mullinix, Leeper, Druckman and Freese2015). Another limitation is that we test our argument on the single issue of mobility and its recommendations are about how to spend an additional budget. We encourage future work to not only test our argument across different issues, but also to shed light on the generalisability of our findings across different countries and contexts. For instance, it would be interesting to examine effects on political support in countries where the government assigns minipublics on a more regular basis or in instances where a deliberative forum is initiated by civil society actors or as part of an academic research project (Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2018). Finally, a qualification of our findings – and of research into the effects of deliberative forums on the wider public in general – is that they are conditional on citizens being aware of a minipublic happening in their region or country. While the media are oftentimes referred to as a transmitter of such information, we should take into account that media attention and framing follow certain logics of themselves (Parkinson, Reference Parkinson2006).

Our findings suggest several avenues for future research. We welcome studies that add further nuance and complexity in studying the role of minipublics in relation to broader political decision-making processes. While this study takes a step by looking at policy adoption, this is one of many forms in which minipublics can have an impact on political decision making (Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006). We also encourage future work to examine the role of explanation and justification of policy decisions, thereby taking a broader outlook on responsiveness to minipublics’ advice (de Fine Licht et al., Reference de Fine Licht, Agerberg and Esaiasson2022; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017; Font & Blanco, Reference Font and Blanco2007). In doing so, these could pay attention to reasons for which the public would find it (un)acceptable that a minipublic's advice is not being followed. Future studies could also elaborate on the mechanisms of why minipublics can have effects on political support among the general public (Werner & Marien, Reference Werner and Marien2018). To date, we have limited knowledge of why citizens outside the forum who hear or read about a minipublic may adjust their level of political support. Finally, future research could disentangle the interplay between process and outcome evaluations in the context of minipublics, for example, across different political issues (e.g., controversial vs. non-controversial). We leave it to future studies to tackle these challenges.

Overall, this study presented novel insights into the role of policy adoption in shaping the effect of a minipublic on political support among the public at large. In doing so, this study contributes to a better understanding of whether, and under what conditions, the use of deliberative minipublics may alleviate or aggravate political dissatisfaction.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants in the 2020 ECPR General Conference (virtual) and the 2020 TrustGov Digital Conference ‘Political Trust in Crisis’ as well as to the three anonymous reviewers for their valuable and inspiring feedback. We would also like to thank the Democratic Innovations and Legitimacy Research Group at the KU Leuven for their constructive and cheerful support at various stages of this project.

Author Contributions

The author order reflects the relative contribution of the authors. Both authors contributed equally to the original idea and the empirical research design, while Van Dijk developed most of the paper's theoretical framework and took the lead in the writing process and data analysis.

Ethics Statement

This project has received ethical approval from the KU Leuven (file number: G-2020-1642).

Funding Information

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement no. 759736). This publication reflects the authors' view and that the Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. This project (G0F0218N) has received funding from the FWO and F.R.S.-FNRS under the Excellence of Science (EOS) programme.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix

Supplementary material