Introduction

Reducing economic development in medieval England to a gradual transition to capitalism emphasises the role of landowners, urban demand and enterprising proto-capitalist farmers and merchants, generating a singular, progressive and majoritarian narrative. This article adds complexity, using urban pottery production in the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries AD to exemplify the processes of urbanisation and commercialisation as minoritarian phenomena, through which society is transformed by undirected actions beyond institutional power. Starting from the reconstruction of pottery-marketing networks, and drawing on recent interventions in entrepreneurship scholarship, I examine the contribution of potters to economic development through their manipulation of systemic constraints on economic innovation and consider how we might account for entrepreneurship and innovation as sociomaterial processes in narratives of medieval commercialisation.

Urbanisation and economic development in medieval England

Interpretations of the progression of medieval economies towards capitalism variously foreground demographic change, class struggle and commercialisation as causal factors (Hatcher & Bailey Reference Hatcher and Bailey2001; Dimmock Reference Dimmock2014). Commercialisation—the establishment of markets and fairs and specialisation in commodity production—is a key feature of the period c. AD 1100–1350, occurring within the established structures of manors and estates. The associated process of urbanisation, the establishment of―typically small―towns, facilitated and was stimulated by commercialisation (e.g. Hilton Reference Hilton1976; Britnell Reference Britnell1996). Brenner (Reference Brenner1982: 17–18) points to divergent patterns of economic development across western Europe to propose that capitalism is not an inevitable ‘next step’ in this process, arguing that economic development is contingent upon inherited class structures and emerges through processes of social competition and collaboration which are both horizontal (i.e. within classes) and vertical (i.e. between classes). Despite substantial critique (see Aston & Philpin Reference Aston and Philpin1985; Dimmock Reference Dimmock2014), Brenner’s thesis is of value in emphasising the contextually situated character of economic change.

Rather than debating Brenner’s thesis here, I take two key points from it: that capitalism is not the inevitable outcome of ‘feudalism’, meaning that economic change can be understood as non-linear and open-ended; and that demographic and economic changes generate a creative friction that necessitates shifts to maintain capacities for social reproduction. England in the twelfth–fourteenth centuries is often referred to as ‘feudal’ in the sense that society was structured through relations of obligation between lord and tenant. This society was not monolithic; the peasantry were a socially differentiated group and a process of commercialisation, stimulated by the actions of both a seigniorial elite and the wider population, was generative of further difference (Dimmock Reference Dimmock2014: 188). Towns emerged as distinct sites of commercial exchange and commodity production, but urbanisation and commercialisation were geographically and temporally uneven, with moments of acceleration and deceleration and, critically, of progress and regression.

Teleological narratives of economic development—in which capitalism is the inevitable outcome of incremental technological change and labour efficiencies—are majoritarian, in that they foreground the role of entrepreneurial landowners, the guilds found in larger towns, and wealthy clothiers and yeomen farmers as key instigators of change after 1400. However, economic change is not a singular process; Britnell (Reference Britnell1996: 123) describes commercialisation as “the outcome of millions of separate decisions by landlords, peasants and labourers seeking to improve their lot”, fuelled by the increasing availability of untapped resources including land, materials and labour. This encapsulates a dynamic of horizontal and vertical competition; commerce posed challenges and opportunities for social reproduction, necessitating adaptation and creativity within the constraints of a persistent class structure.

My proposal is for a minoritarian understanding of economic development, focused on how the actions of peasants and artisans responded to these dynamics in creative ways that did not necessarily amount to a cumulative progression to capitalism, but created specific contextual conditions for economic change. In doing so, I follow recent literature, which has fruitfully engaged with the language of entrepreneurship in exploring medieval urbanisation.

Potters and entrepreneurs

Most entrepreneurship literature is concerned with the period after the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However, both Murray (Reference Murray, Lands, Mokyr and Baumol2010) and Casson and Casson (Reference Casson and Casson2014) convincingly argue that entrepreneurship, albeit in a contextually specific form, was a feature of medieval European society. Casson and Casson (Reference Casson and Casson2023: 284) also define the recognition and development of the potential of places for urban development as entrepreneurship, with urban entrepreneurs being those who acquired and developed urban property and those engaged in mercantile trade. Goddard (Reference Goddard2011) defines small boroughs as ‘enterprise zones’ within manors, where burgesses were granted land and rights to stimulate migration and commercialised production. Artisans and merchants are occasionally referred to, in passing, as entrepreneurs (e.g. Dyer Reference Dyer2022: 278), although without critical interrogation of the term.

Entrepreneurship has long been associated with creating rather than adapting (Schumpeter Reference Schumpeter1947: 150). Weiskopf and Steyaert (Reference Weiskopf, Steyaert, Hjorth and Steyaert2009) define entrepreneurship as an ability to create, instead of merely taking advantage of, opportunities. It is a process of creative becoming, an inventiveness that increases possibilities in life. In asking how entrepreneurship might be used in relation to the medieval economy, I focus on a specific group of artisans—urban potters—operating between c. 1200 and 1350, examining how they acted entrepreneurially within an inherited socioeconomic structure and how this behaviour was difference making. In this period, pottery production was overwhelmingly rural; industries developed in areas of abundant clay and fuel, with easy access to markets and fairs. Pottery could be traded directly or through middlemen. In some cases, potters operated in isolation, while in others, communities of potters were concentrated in specific places. Despite the ubiquity of pottery, documentary references to potters are scarce. Le Patourel (Reference Le Patourel1968: 106) concludes that in the thirteenth century rural potters were usually cottagers, meaning they held a small amount of land and typically owed light labour services to the landowner (see also Dyer Reference Dyer2022: 285–88). Evidence from the town of Woodstock (Oxfordshire) suggests that some potters accrued urban property, while at Harlow (Essex) potters held land in a suburban area known as Potterstreet, indicating the emergence of specialist neighbourhoods. Taxation records suggest that urban potters were typically at the lower end of the wealth spectrum (Le Patourel Reference Le Patourel1968: 113).

Potters operated in varying relation to landowners. In some cases, where potters had a kiln on their property, this might be limited to paying tolls for access to clay or fuel. In others, potters paid rents for kilns, as at Brill (Buckinghamshire) (Le Patourel Reference Le Patourel1968: 113–15, 117–18). Following Peacock (Reference Peacock1982), production likely ranged from household industry, where potting was a secondary source of household income, to individual or nucleated workshops, whereby it was a principal source of income. At Harlow, fourteenth-century court records indicate that, despite being recognised as potters, some households, in common with other urban artisans, maintained agricultural interests (Le Patourel Reference Le Patourel1968: 111).

The urban potters discussed here likely operated at the level of the individual or nucleated workshop, producing large quantities of pottery as their primary economic activity, as indicated by the number of kilns, diversity of wares and large quantities of kiln waste. Urban pottery industries are rare and, where they do occur, they are typically suburban. For example, at Chichester (West Sussex) (Streeten Reference Streeten1985: 281–87), Kingston (Surrey) (Pearce & Vince Reference Pearce and Vince1988: 11) and Beverley (East Yorkshire), where placenames attest to suburban pottery production in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, although archaeological evidence generally dates prior to the mid-fourteenth century (Evans Reference Evans and Gläser2006: 84–85). More unusual is Barnstaple (Devon) where production took place within the town, a phenomenon also identified through the excavation of fourteenth-century kilns at Scotch Street, Carlisle (Cumbria) (Giecco Reference Giecco2004). At Doncaster (South Yorkshire) excavated kilns dating from the eleventh–thirteenth centuries have been excavated within the town (Cumberpatch et al. Reference Cumberpatch, Chadwick and Atkinson1999), although pottery was apparently sourced from rural areas during the later thirteenth or fourteenth century (Cumberpatch Reference Chadwick2008: 95). More commonly, pottery industries were established beyond the urban limit. For example, at Lostwithiel (Cornwall) production took place on a hillside near the town (Allan et al. Reference Allan, Dawson and Mepham2018). In undertaking an industry better suited to, and strongly established within, rural areas it is my contention that these unusual urban potters can be defined as entrepreneurs who created not only pottery, but new implications for urban and commercialised life.

Pottery and commercial relations

Pottery distributions provide some of the best archaeological evidence for the commercial networks of medieval England, being a measure of both the connectivity of markets and the entrepreneurial behaviour of potters and traders. Detailed studies of pottery distribution (e.g. Vince Reference Vince1983; Streeten Reference Streeten1985; Spoerry Reference Spoerry2016) demonstrate the range of factors that influenced the movement of pottery and the organisation of its production. These include access to communication routes, local settlement patterns, the distribution of markets and fairs, and population density, although pottery could also move through a range of other, non-commercial mechanisms (Moorhouse Reference Moorhouse1983: 69–72).

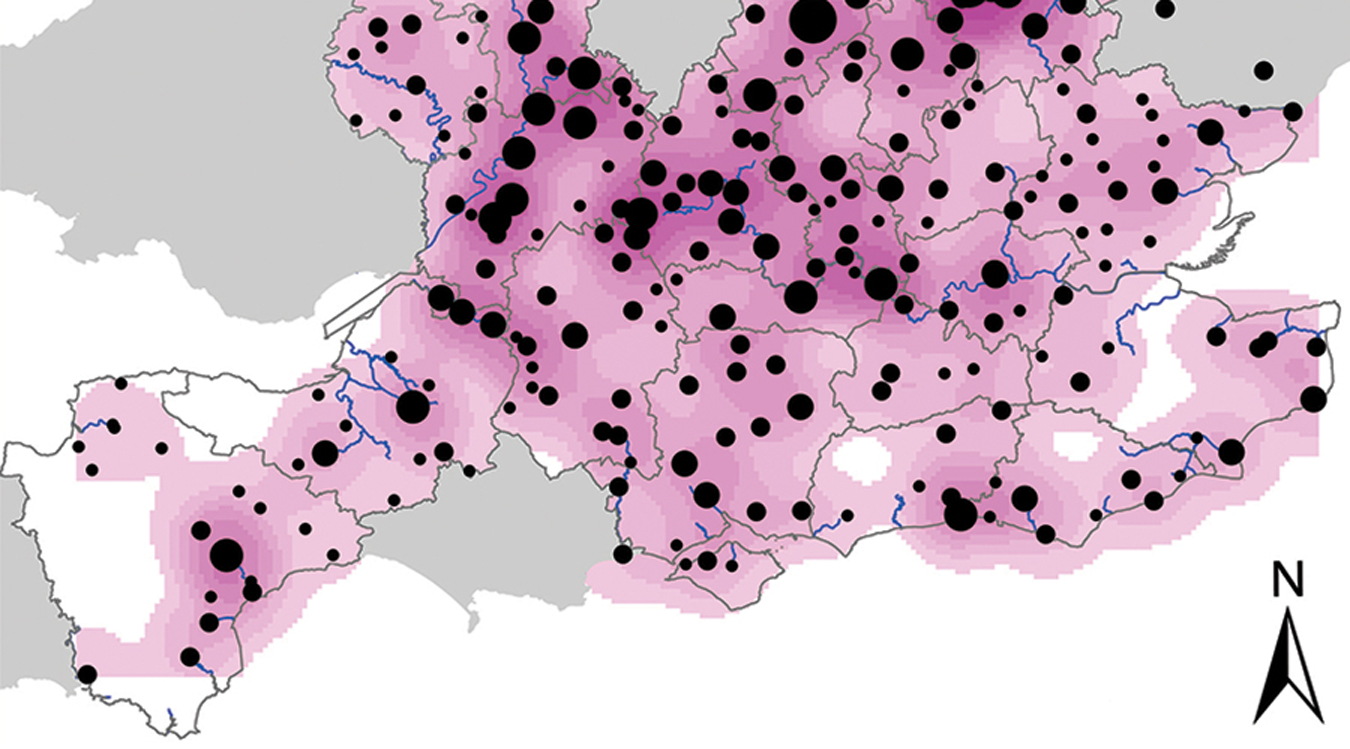

Figure 1 illustrates the pottery supply to towns in southern and midland England in the period c. AD 1200–1350, based on data derived from published and ‘grey literature’ archaeological reports. The network incorporates small towns in this region from which suitably documented pottery assemblages have been recovered, and large towns within and adjacent to this region (see online supplementary material for further details). The network comprises two sets of nodes: towns and production regions (production centres or regions producing similar wares), with the edges representing the movement of pottery. Figure 2 shows the relative density of commercial activity based on the range of pottery artefacts present. These demonstrate marked variability in the organisation of pottery marketing. Particularly diverse assemblages are present in Cambridgeshire, well connected by riverine routes, and along the Thames and Severn valleys. In other areas, assemblages are more homogeneous; in east Kent, for example, products of the Tyler Hill kilns, near Canterbury, dominate. Yet, any network is a partial representation of historical processes, limited by the scope of inquiry and the available evidence. Pottery distributions do not necessarily reflect other commercial networks, rather they are a tool for understanding specific material entanglements within the wider patchwork of the medieval economy.

Figure 1. Network graph showing flows of pottery between production regions and towns in midland and southern England. Black: towns; red: production area. Not to scale (figure by author).

Figure 2. Heatmap showing the diversity of urban pottery assemblages in midland and southern England (figure by author).

Network diagrams visualise the relations between social actors, such as communities or objects, through the flow of goods, people or information, while statistical analysis lends itself to assessments of the connectedness and centrality of nodes within a network (Brughmans Reference Brughmans2013). Knutson (Reference Knutson2021) emphasises that while networks are useful for observing phenomena, further types of analyses are required to explain the processes of transformation they capture, and advocates for the combining of network analysis with assemblage theory to achieve this. Derived from the writing of Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1984, 1987) and situated within a broader body of post-human philosophy, assemblage theory understands the world as a composition of productive relations between diverse entities. These productive assemblages are multiscalar and fluid. There are clear synergies between these approaches; both assemblages and networks are expansive and lack obvious boundaries. Both are also concerned with the relations between parts; however, the discrete nodes within a network flatten the multiscalar and dynamic relations of which they are constituted (Hodder & Mol Reference Hodder and Mol2016: 1070; Knutson Reference Knutson2021: 806). Whereas a network can be understood as representing multiple, small-scale interactions, assemblage theory allows us to understand the agentive capacity of nodes across a network (Knutson Reference Knutson2021: 813).

Following Deleuze and Guattari (1987: 11–13), we can perceive of a network graph as a tracing of relations, an attempt to produce a facsimile of what existed. The authors frame assemblage analysis as a process of mapping; an open-ended approach to studying relations as productive and transformative. These approaches exist in dialogue; we need an empirical understanding of past relations, but we also need to understand the potential implications of these relations. Mapping relations casts flows of pottery not as representative of the growth of commercial networks, but as constitutive of their emergence as the outcome of entrepreneurial behaviour, providing a means to better understand those millions of decisions that constituted commercialisation.

Assemblage theory is a process philosophy, through which we can understand the world as constituted of flows of matter, energy and knowledge that move across time and space, becoming productively entangled (or ‘territorialised’) and breaking apart (or ‘de-territorialised’). Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1984: 257–62) argue that the power structure of what they term ‘feudal’ society constrains, or ‘codes’, these flows, striating the spaces across which they move. This is analogous to the inherited class structures identified by Brenner (Reference Brenner1982). Capitalism emerges as the ‘de-coding’ of these flows, a smoothing of space, and the emergence of new institutions to constrain them. This resonates with the processes of horizontal and vertical competition identified by Brenner as drivers of socioeconomic change. This way of thinking allows us to perceive change as emerging in multiple ways, creating a space to understand capitalism as a gradual and uneven development, and for this de-coding of flows (for example through acts of resistance) to be an element of a medieval society dominated by a seigniorial elite who variously sought to simultaneously regulate and constrain these flows and stimulate their de-coding (for example by founding markets and fairs). Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1984, 1987) sought to challenge capitalist hegemony by imagining alternative forms of life, resonating with the writing of an economic history alive to the potential of capitalist entanglements, but which also seeks to understand the multiple economic potentialities that emerged through urbanisation and commercialisation.

Approaching pottery production and marketing in this way provides a new perspective on economic change, working towards what Deleuze and Guattari (1987: 122–4) would term a ‘minoritarian’ reading of economic development, opposed to a teleological narrative of inevitable capitalism emerging from the medieval economy. We can understand development as patchy and entrepreneurial behaviour as not limited to the ‘heroes’ of the teleological narrative, but as a process through which people worked with materials in social transformations.

Majoritarian narratives of institutional entrepreneurship

Religious and secular landowners (who I term broadly as ‘institutions’) acted entrepreneurially during the Middle Ages (primarily between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries) to establish a network of markets and fairs. Their behaviour freed flows of goods, materials and capital, but also sought to regulate these, to protect and further their interests. This conforms to a notion of ‘institutional entrepreneurship’, defined as “the activities of actors who have an interest in particular institutional arrangements [i.e. the reproduction of their socioeconomic position] and who leverage resources to create new institutions or to transform existing ones [i.e. by responding creatively to the impact of horizontal and vertical competition]” (Colombero et al. Reference Colombero, Duymedjian and Boutinot2021: 1).

Landholders often received rents or tolls for the extraction of clay and access to fuel, which would have risen with increased pottery production. At the town of Farnham (Surrey), for example, the Bishops of Winchester obtained regular payments from potters for clay extraction (Streeten Reference Streeten1985: 143) and at Brill (Buckinghamshire) the Crown (as lords of the manor) received rents for the use of pottery kilns and payments for clay (Farley & Hurman Reference Farley and Hurman2015: 181). The Brill potters likely benefitted from patronage, the presence of a royal hunting lodge creating periodic demand for pottery, and they were allowed to collect fuel from the royal forest (Farley & Hurman Reference Farley and Hurman2015: 180). Brill Wares also supplied Oxford and were widely traded across an area stretching from the Severn to the Wash (Mellor Reference Mellor1995: 138–40) (Figure 3A). The industry declined after the manor passed out of royal control in 1324 (Mellor Reference Mellor1995: 140).

Figure 3. Urban distribution of A) Brill/Boarstall Ware; B) Minety-type Ware; C) Bourne Ware; and D) Surrey Whiteware (figure by author).

Pottery distributions provide further hints to the relationship between potters and the entrepreneurial actions of ‘institutions’. Cirencester Abbey acted entrepreneurially in developing Cirencester (Gloucestershire) as a commercial hub, supporting its interests by not granting the town borough status and not developing subsidiary markets on its estate, allowing the abbey to exercise substantial control over commercial activity. In the fourteenth century the dominance of Cirencester Abbey was challenged by a newly established Guild Merchant, and their long-running disputes demonstrate how commercialisation developed new institutions that then required measures to be taken to secure institutional dominance (Fuller Reference Fuller1885). Cirencester’s ceramic assemblage is dominated by wares produced at Minety, a nearby manor held by the abbey, contrasting the historical evidence for Cirencester’s role as a node in far-reaching trading networks (Rollinson Reference Rollinson2011). Minety Wares were widely traded overland (Figure 3B). Regardless of whether or not the abbey exerted direct control over the industry, such as by establishing clay rents, this distribution demonstrates both the commercial reach of Cirencester Abbey and how its estate management limited opportunities for other products to penetrate the Cirencester market.

In contrast to Cirencester, Huntingdon and Swavesey (Cambridgeshire) have among the most diverse ceramic assemblages in the network because the River Great Ouse, the fenland waterways and the road network facilitated movement of ceramics over relatively long distances. One of the industries supplying these towns was at Bourne (Lincolnshire), where a major suburban industry was established. Bourne Wares are plain, utilitarian vessels, which were widely traded through fenland waterways (Spoerry Reference Spoerry2016: 67) (Figure 3C). In contrast to Cirencester, Bourne was a small market but potters exploited the wider commercial opportunities, facilitated by the actions of Bourne Abbey and other religious houses, to create markets and a connective infrastructure through Fenland management (Sayer Reference Sayer2009).

At face value, these examples illustrate a majoritarian view of economic development. The establishment of markets stimulated intensive and specialised production, offering institutions further opportunities to maximise their income through the establishment of tolls on the acquisition of materials and undertaking of commerce. Observing these industries through the lens of institutional entrepreneurship suggests that potters operated within a framework shaped by institutions, trapping them into habitual economic behaviour. Commercialisation was characterised by the purposeful manipulation of ‘taken-for-granted’ resources such as labour, clay and fuel.

Figure 1 illustrates variability in trading patterns, yet understanding the affect of material relations in creating and sustaining commercialised life requires a mapping approach, which picks apart the underpinning processes. Flows of pottery into towns highlight not only how they are ‘territorialising’ elements in commercial networks, formed of spatially concentrated gatherings of people and materials, but also how urban life is de-territorialising; urban demand created possibilities for landowners to exploit. Variability in ceramic assemblages is often linked to the role of material culture in identity work, with towns being places in which consumers made active choices (e.g. Green Reference Green2016; Jervis Reference Jervis2017). However, commercialisation was not a process shaped solely by demand-side requirements or supply-side innovation, but was a process through which institutions’ decision-making shaped and constrained possibilities for commercialisation, while market demand created spaces through which they could act entrepreneurially by forging new relations with their manors’ material and labour resources.

This narrative excludes a critical element in this process, reducing labour, materials and pottery to passive things awaiting commercialisation or urbanisation, as opportunities to be acted upon by these institutional entrepreneurs. From an assemblage perspective, these ‘institutions’ are themselves relational compositions, open to potential moments of de-territorialisation. Institutions are ‘leaky’. It is in this leakiness that Colombero and colleagues (Reference Colombero, Duymedjian and Boutinot2021) identify their potential to be breached, for resources to be drawn from this majoritarian system and creatively manipulated, which they call a process of ‘becoming’. For Weiskopf and Steyaert (Reference Weiskopf, Steyaert, Hjorth and Steyaert2009), entrepreneurship is an intensive space of creation and transformation, something performed by ‘ordinary people’ that takes them beyond the habitual, passive and docile as a process of connective creativity. Just as ‘institutions’ could abduct household labour and technological practices, so too could artisans abduct institutional resources and manipulate them through horizontal and vertical competition, acting to shape historical emergence rather than being passively taken along with it. This takes us toward an understanding of entrepreneurship performed in the minoritarian register, which sees economic change not as a predetermined event but as a processual emergence formed of breaches that might disrupt or stimulate institutional entrepreneurship but are distinct from it.

Potters as minoritarian entrepreneurs

Frieman (Reference Frieman2021: 18) critiques narratives that valorise new technologies and ‘great men’ instead of attending to innovation as an incremental, change-making process. This chimes with Colombero and colleagues’ (Reference Colombero, Duymedjian and Boutinot2021: 3) suggestion that institutional entrepreneurship and ‘becoming’ nourish each other; ‘becoming’ feeds itself with institutional resources which are broken down and recombined to create something new, while new forms of institutional entrepreneurship can emerge from breaches. Innovations are embedded within and arise from complex inter-relations, having messy and non-linear histories (Frieman Reference Frieman2021: 49–50). Understanding medieval commercialisation as a patchwork of such innovations centres the material relations constitutive of economic change. Commerce de-territorialised flows of clay by entangling them through market networks and created opportunities for the clay to be brought into contact with other materials, such as lead and copper used in glaze production. The potential afforded by this pottery, particularly in the urban contexts where it was consumed, was one vector through which hierarchical practices of display and consumption could be broken down and renegotiated (Jervis Reference Jervis2017). For example, the breadth of wares produced at Brill—where potters were dependent on the manor for access to kilns, fuel and clay—demonstrates how institutional entrepreneurship created conditions in which potters could express creativity in the production of complex and highly decorated vessels such as jugs and aquamaniles (specialised vessels for hand washing, often of zoomorphic form) (Hilton Reference Hilton1976: 18) (Figure 4). Potters were transformative not only of the materials themselves, but of the material worlds into which their products were woven, as commerce created possibilities for pottery to assume new social roles as it became incorporated into a range of practices (e.g. Green Reference Green2016). The manipulation of materials was an institutional breach through which flows could be de-coded and de-territorialised, in which potters could become active and creative participants in the transformation of medieval society, and where we understand creativity as a form of contextually situated practice (Sofaer Reference Sofaer2015: 2). It is through attending to these processes of creation that we can understand how commercialisation was shaped through a patchwork of intimate, local interactions, rather than being an abstract force produced principally through institutional endeavour and bureaucracy.

Figure 4. Examples of highly decorated pottery produced at Brill in Buckinghamshire and Kingston in Surrey. A) Brill-type Ware puzzle jug with zoomorphic decoration from Angel Inn, Oxford (BM 1893.0205.069). Height: 290mm; B) Kingston Ware aquamanile found in London (BM 1855.0512.013). Height: 135mm; C) Kingston Ware highly decorated jug from Cannon Street, London (BM 1856.0701.1566). Height: 282mm; D) Kingston Ware jug with bearded face, from London (BM 1855.1029.11). Height: 115mm (images © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence).

There were certainly conservative elements to medieval pottery; the form of simple cooking jars and functional bowls remain relatively unchanged throughout the Middle Ages. Yet, innovation is apparent in the highly decorated wares produced in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries and as various functionally specialised products began to appear in the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Blake (Reference Blake1980: 5) considers pottery to be an ‘elastic commodity’—that is, an inessential product performing a function that could be fulfilled in other materials—while Orton (Reference Orton1985) argues that innovation is a response to specific circumstances. The implication of this is that demand drives innovation. In the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, the booming economy and growing population, with increasing levels of social differentiation, provided potential for pottery to fulfil new social roles, and potters, as entrepreneurs, were able to capitalise upon this, creating not only new types of pottery but new ways for it to be used.

If we imagine goods and materials flowing through time and space, rule regimes—such as the regulation of markets and restrictions on access to clay and fuel—are one force that striates that space, constraining flows and limiting the potential for abhorrent emergences. Deleuze and Guattari (1987: 482–84) describe how smiths, through their relations with materials, puncture through striations, creating ‘holey spaces’; transitory spaces where striation bores into the smooth, or smoothness resists striations. Pottery production can be understood in the same way. As commerce freed flows of clay, creative engagement with it generated the potential to produce objects that might challenge social distinctions or stimulate new social interactions. Examples include anthropomorphic jugs, linked to new ways of performing masculinity (Cumberpatch Reference Cumberpatch2006; Green Reference Green2016), and aquamaniles depicting sheep, possibly mimicking the tableware of higher-status households (Hinton Reference Hinton, Dyer and Jones2010).

Urban pottery production was rare, but where it did occur it helped transform urban space. In the thirteenth century, Kingston (Surrey) became a major pottery production centre. As a medium-sized town it was unusual in supporting such a large pottery industry, particularly given its distance of at least eight miles (approx. 13km) from the Reading Clay outcrops used by its potters. Kingston was recognised as a borough in 1242, and its wares held a substantial share of the London market until the mid-fourteenth century (Pearce & Vince Reference Pearce and Vince1988: 16, 91). In the 1260s, Westminster Palace (the king’s principal residence at the time) ordered large quantities of Kingston pottery (Le Patourel Reference Le Patourel1968: 120). Pottery production was probably initiated by potters who migrated from closer to London (Pearce & Vince Reference Pearce and Vince1988: 82), choosing Kingston because of its connectivity and access to fuel; archaeological evidence shows the use of local heathland plants as well as wood in the firing of kilns (Davis Reference Davis, Miller and Stephenson1999).

The Kingston potters innovated by establishing an urban industry without direct access to clay. They were entrepreneurs because they took on the risk of setting up in a new location, negotiated access to resources and exploited existing opportunities for market access. They acted within a breach in institutional entrepreneurship, extracting an institutional resource—connectivity to the London market and commercial legitimacy—while having a transformative impact on urban life. The manipulation of clay and the burning of fuel did more than produce pots, it generated difference within the urban landscape. Potting, stimulated by commerce, transformed the urban landscape, and generated new ways of living in it. While urbanisation and commercialisation created possibilities for the flow of people and materials into Kingston, their creative manipulation allowed potters to both cater for and determine the needs of the London market as they developed increasingly diverse products (Pearce & Vince Reference Pearce and Vince1988: 85) (Figure 4). Innovation can be observed as potters experimented with new forms and decorative styles as they created material dependencies that flowed through wider networks, as demonstrated by the expansive distribution of Kingston-type Wares (Figure 3D). Following Knutson (Reference Knutson2021), we can understand the actions encapsulated within a particular node as having implications which resonate across a network at multiple scales. These actions could be homogenised within a generalising narrative of enterprising artisans being attracted to new towns and practising their crafts at new levels of intensity. This narrative would, however, conceal the small-scale interactions through which commercialisation surfaced and was manipulated and developed by these potters, who were able to manipulate large-scale institutional and urban demand and the institutional structures of trade to generate specific, creative and transformative moments of ‘becoming’.

A minoritarian approach recognises the multitude of ways that materials might be folded into life; there is no ‘best way’, but rather multiple forms of creative becoming (Weiskopf & Steyart Reference Weiskopf, Steyaert, Hjorth and Steyaert2009: 196). This can be seen in the range of ways in which the pottery industry responded to, and participated within, the twin processes of urbanisation and commercialisation. While industries could be integral elements of (sub)urban life, industries primarily developed in rural areas, often strategically located to exploit multiple markets. These potters created new dependencies, as urban communities came to rely on their wares and potters intensified their exploitation of materials. Intensive rural production—such as that at Olney Hyde (Buckinghamshire) where 13 probable kilns have been identified (Farley & Hurman Reference Farley and Hurman2015: 222)—shows how commercialisation seeped into the rural economy. The growth of markets, combined with the more-than-agrarian resources of rural landscapes created spaces for the diversification of rural economies. In this way, rural producers, though constrained by institutional demands, were able to create spaces through which rural industry could expand, through which difference could emerge and through which they could shape commercial growth rather than being passive pawns in its emergence. While potting likely made only meagre returns, commercialisation created opportunities for intensified production and for rural lives to be made less precarious through diversification.

Conclusions

Potters are an example of small-scale commodity producers who are typically seen as existing within a process of commercialisation. Attending to their decisions and practices allows for an alternative, minoritarian perspective on economic development to emerge. Following Deleuze and Guattari (1987: 317–21) we can understand change not as ‘molar’ but as ‘molecular’, as constituted of related intensities rather than being a singular process. Pottery distributions give a partial picture of commercial networks, but if we shift our perspective from one of tracing to one of mapping, we can explore the processes of exploitation, creativity, entrepreneurship and innovation, which were articulated through pottery making and which played a role in the constitution of the commercialising and urbanising society of medieval England. Pottery, as with most archaeological objects, is a ‘minoritarian’ material in a narrative dominated by the ‘majoritarian’ commodities of woollens and grain. While we are familiar with entrepreneurship in the context of these industries, a minoritarian perspective provides a means to understand the circumstances and effect of the millions of decisions made by peasants and town dwellers. Within medieval studies, entrepreneur is a term often used to describe those who make movements towards capitalism—for example, proto-capitalist clothiers, merchants or town founders—but if we adopt an idea of entrepreneurship as an “inventiveness that increases the possibilities of life that are not yet known” (Weiskopf & Steyaert Reference Weiskopf, Steyaert, Hjorth and Steyaert2009: 200) we can identify it in a wide variety of difference-making material interactions. Critically, this approach draws us away from teleological narratives of capitalist inevitability, instead revealing the complex and situated processes of economic change that characterise this period. Urbanisation, commercialisation and the transition to capitalism were processes composed of a multitude of everyday interactions, which had implications that extended beyond themselves. Towns were not just places where commerce and craft happened, but places that amplified the possibilities afforded by material interactions, created new potential for the breaching of the hegemony of institutions and, rather than homogenising material encounters, also created possibilities for difference.

Funding statement

This research was undertaken as a part of the project ‘Urban life in a time of crisis: enduring urbanism in medieval England (ENDURE)’, selected by the European Research Council and funded by UK Research and Innovation under grant agreement EP/X023850/2.

Data availability

Data relating to the distribution of ceramics presented in this article are available at https://doi.org/10.25392/leicester.data.28264694

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.70 and select the supplementary materials tab.