Introduction

Political scientists and civil society initiatives in many established democracies are increasingly concerned with interventions aimed at reducing affective polarization, that is, animosity between partisan camps (for an overview, see Hartman et al., Reference Hartman, Blakey, Womick, Bail, Finkel, Han, Sarrouf, Schroeder, Sheeran and Van Bavel2022). Most approaches leverage insights from social psychology to correct misconceptions about out‐partisans (e.g., Ahler & Sood, Reference Ahler and Sood2018), highlight commonalities (e.g., Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2018) or facilitate conversations between people of different camps (e.g., Kalla & Broockman, Reference Kalla and Broockman2023; Voelkel et al., Reference Voelkel, Ren and Brandt2021; Wappenhans et al., Reference Wappenhans, Clemm von Hohenberg, Hartmann and Klüver2024). And, although many of these interventions are effective, they are also expensive and hard to scale. Scholars of comparative politics thus argue that reforms to political institutions like electoral systems (e.g., introducing proportional representation or multi‐member constituencies) might constitute an important avenue to change politicians' incentives and foster inter‐party cooperation, which, in turn, is argued to reduce affective polarization (e.g., Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023; McCoy & Somer, Reference McCoy and Somer2019; Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020).

The most prominent finding of this comparative literature is that coalition governments involving different parties reduce affective polarization between coalition partners (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023). Coalition governments are said to foster a ‘superordinate political identity […] and create shared incentives for policy accommodation and compromise’ (Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024, p. 71). Groups that were previously considered out‐groups begin to share an overarching identity – the one of the coalition – once they start to cooperate (Bassan‐Nygate & Weiss, Reference Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss2022). This argument is underpinned by plenty of experimental (e.g., Bassan‐Nygate & Weiss, Reference Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss2022; Ekholm et al., Reference Ekholm, Bäck and Renström2022; Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024; Wagner & Praprotnik, Reference Wagner and Praprotnik2023) and observational evidence (e.g., Bantel, Reference Bantel2023; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022; Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023).

That being said, it is puzzling that affective polarization in countries like Sweden, Denmark or Belgium – which political scientists have traditionally thought of as ‘consensual democracies’ characterized by compromise‐seeking elites and coalition governments (Lijphart et al., Reference Lijphart1999) – is about as pronounced as or even higher than in the United States (Garzia et al., Reference Garzia, Ferreira da Silva and Maye2023; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018).Footnote 1 This raises an interesting question: If consensual institutions like coalition governments mitigate partisan animosity, why is affective polarization nevertheless rampant in political systems characterized by such institutions?

In this research note, we argue that the extent to which voters are satisfied with a coalition's governing performance strongly moderates its ability to reduce affective polarization. If voters are dissatisfied with how the government is run, the positive effect of being in a coalition is significantly attenuated. We base this argument on classic work in social psychology concerned with inter‐group relations and out‐group affect (Allport et al., Reference Allport, Clark and Pettigrew1954; Brewer, Reference Brewer, Capozza and Brown2000; Pettigrew & Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006; Sherif, Reference Sherif1958), which stresses the relevance of ‘common goals and interests’ as a condition for successfully changing affect towards other social groups (for recent applications from political science, see Choi et al., Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2022, Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2023; Lowe, Reference Lowe2021; Mousa, Reference Mousa2020). With that in mind, we argue that the effect of being in a coalition with members of an out‐party in isolation is insufficient to change out‐party affect. Instead, it requires being successful in a coalition. When a coalition is perceived as performing badly, voters of coalition parties will not feel closer to their coalition partners. This is because the ‘superordinate identity’ – which was introduced through the formation of a coalition – is too weak and partisan identities too strong when coalitions are not performing well.

We test this argument with survey data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) covering 43 elections in 15 Western democracies between 2001 and 2015. This enables us to compare across as well as within countries over time and speak directly to existing comparative research on the effect of coalitions on affective polarization (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023; Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023). We find that the pronounced positive effects of being in a coalition, which previous research reports, are primarily driven by a relatively small group of voters who think that the government is doing well. The positive effects of being in a coalition are much weaker among voters who are dissatisfied with the government. In other words, being dissatisfied with the government's performance significantly attenuates the positive effects of coalition memberships. Among the sizable group of citizens who view the government's performance as bad or very bad, the depolarizing effect disappears entirely. We conclude that only when coalitions are perceived as performing well, they can successfully reduce affective polarization. Some analyses suggest that this effect is a consequence of voters' perceiving their coalition partners as ideologically closer when a government is running well, rather than a consequence of the elite cues voters receive.

This note contributes directly to an ongoing debate about potential reforms of democratic institutions to address the challenges of modern democracies (e.g., Quinn, Reference Quinn2023; Rodden, Reference Rodden2019; Santucci, Reference Santucci2022). Extant work argues that democratic institutions, like two‐party systems with winner‐takes‐all elections, contribute to ideological and affective polarization because parties, by design, are pitted against each other (e.g., Dalton, Reference Dalton2021; Drutman, Reference Drutman2020). While this is certainly true, our results demonstrate that in addition to these reforms, it also requires political parties to use such institutions to cooperate successfully in the eyes of the public. We thus caution against the idea that reforms to democratic institutions in isolation are sufficient to resolve challenges related to affective polarization.

When do coalitions succeed at reducing affective polarization?

Much research has shown that elite cooperation plays an important role in reducing affective polarization (e.g., Bantel, Reference Bantel2023; Bassan‐Nygate & Weiss, Reference Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss2022; Ekholm et al., Reference Ekholm, Bäck and Renström2022; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023; Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022; Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023; Huddy & Yair, Reference Huddy and Yair2021; Wagner & Praprotnik, Reference Wagner and Praprotnik2023). One particularly strong and institutionalized form of elite cooperation is coalition governments. Coalitions are argued to reduce affective polarization between supporters of coalition parties by creating ‘superordinate political identities […] and shared incentives for policy accommodation and compromise’ (Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024, p. 71). Groups that were previously considered political opponents (out‐groups) begin to share an overarching identity – the one of the coalition – once they start to cooperate (Bassan‐Nygate & Weiss, Reference Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss2022). This suggests that supporters re‐evaluate their own group membership as well as the composition of the group that they see as the in‐group. This, in turn, reduces affective polarization between followers of coalition parties.

Previous work discusses two routes through which coalition governments could induce such a ‘coalition identity’. First, coalition membership could be a readily available and powerful heuristic for citizens about which parties ‘play in one team’ (Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023). Citizens rely on cues provided by political elites as cognitive shortcuts to form their own perspectives and preferences (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman1991; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Including a party in a coalition demonstrates an acknowledgment and willingness of other parties to collaborate, showing a level of credibility and respect towards the party in question (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022). Second, the fact that multiple parties are governing together and thus have overlapping interests and incentives might make them appear as ideologically more similar (Fortunato & Stevenson, Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013). Wagner and Praprotnik (Reference Wagner and Praprotnik2023), for example, show that coalition signals can reduce the perceived ideological distance between supporters of two potential coalition partners. The changed perceptions of ideological distance and the elite cues that citizens receive could thus facilitate the creation of the aforementioned superordinate coalition identity.

Here, we argue that whether voters are satisfied with a coalition's governing performance significantly impacts the extent to which the coalition reduces animosities between the supporters of coalition parties. Seminal work in social psychology concerned with social identities and out‐group affect (Allport et al., Reference Allport, Clark and Pettigrew1954; Brewer, Reference Brewer, Capozza and Brown2000; Pettigrew & Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006; Sherif, Reference Sherif1958), has argued that ‘common goals and interests’ are a pre‐condition for successfully and lastingly changing affect towards other social groups. This argument is part of a much broader debate in political science and beyond about the type of contact that changes affective evaluations of out‐groups (e.g., Choi et al., Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2022, Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2023; Lowe, Reference Lowe2021; Mousa, Reference Mousa2020). We argue that when voters are dissatisfied with the coalition's governing performance, the ‘superordinate coalition identity’ is too weak to change their (strong) partisan identities. The ability of such a coalition to reduce out‐party dislike is thus clearly reduced. In other words, coalitions ought to be perceived as successful to reduce out‐party dislike meaningfully. Voters' perceptions of how the coalition is performing determine the extent to which they perceive the coalition as pursuing a common goal, which, in turn, predicts how warmly they feel towards followers of their coalition partners.

With the above discussion in mind, we explore two routes through which dissatisfaction with the government's performance could mitigate the positive effects of being in a coalition. First, it appears plausible that when a coalition is not working well, elites begin attacking each other (again). This might change the elite cues that voters receive and increase out‐party dislike. If this were the case, the depolarizing effects of unsuccessful coalitions would be particularly weak among voters who use these elite cues to form political opinions. Second, if a coalition is perceived as working poorly, it might seem to voters that parties are ideologically not aligned. Dissatisfaction with the government could thus change voters' perceptions of the ideological distance between the coalition partners, which, in turn, results in more dislike. We test these two pathways in the following analysis.

Analysis

Data

We analyse data from the CSES project covering 43 elections in 15 established Western democracies between 2001 and 2015.Footnote 2 To allow us to study levels of dislike between parties, the lowest unit of analysis is the party dyad between a respondent's ‘in‐party’ and an ‘out‐party’. As we are interested in people's satisfaction with the government's performance in the past legislature, we base our party‐dyad structures on people's vote choice in the previous election cycle, being either the legislative elections for the upper or lower house or (the final round of) the presidential elections. A voter's ‘in‐party’ therefore corresponds with the party they voted for in those legislative elections and which is considered their political ‘in‐group’, while all other parties constitute political ‘out‐groups’ and are therefore referred to as ‘out‐parties’ (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012).Footnote 3. Descriptive statistics of all variables included in the analysis are provided in the online Appendix A.2.

Estimation strategy

We compute two‐way fixed effects regressions using country and year fixed effects. To adjust for potential interdependence between error terms, we report clustered robust standard errors for country‐years throughout this analysis.Footnote 4

The outcome variable, out‐party dislike, refers to the level of dislike a respondent displays to a certain out‐party, with higher values indicating more intense dislike. Coalition partners is a binary variable which takes the value of 1 if a respondent's in‐party is in a coalition government with the corresponding out‐party and 0 otherwise. Government performance (Gov. Perf.) reflects the rating given by respondents to the governing coalition in the past legislature.Footnote 5 Answer options are very bad, bad, good and very good. When analysing three‐way interactions, however, we will report results for which the two positive and two negative categories of government performance ratings are merged as this increases statistical power and enhances legibility. All outcome variables are z‐standardized. We use a similar party‐dyadic structure and model specifications as existing comparative work on the effects of coalitions on inter‐party affective polarization (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023; Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023). In line with this research, we include a set of control variables. First, we take into account that dislike between coalition parties could be driven by how polarized these parties ideologically are (Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021; van Erkel & Turkenburg, Reference Erkel and Turkenburg2022) by controlling for the elite‐level distance on economic and cultural issues (elite economic polarization and elite cultural polarization, respectively). These scores are derived from the Manifesto Project (Lehmann et al., Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al‐Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Volkens, Weßels and Zehnter2024). Second, as out‐party dislike in multiparty systems is – in large part – driven by the presence of the radical right (Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022), we also control for whether the in‐party or out‐party belong to the radical right (in‐party radical right and out‐party radical right, respectively). Finally, as Gidron et al. (Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023) show that being in opposition together also leads to a mutual reduction in dislike, we control whether the in‐ and out‐party were in opposition together (opposition partners).

The moderating effect of perceived government performance

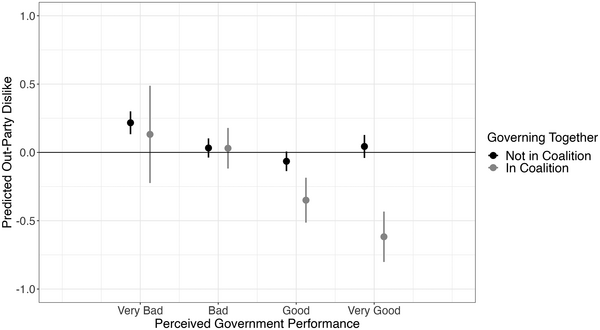

Previous work reports that a respondent's affective dislike towards an out‐party decreases significantly when their in‐party is in a coalition with that out‐party, that is, when that out‐party is a coalition partner (e.g., Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023; Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022; Wagner & Praprotnik, Reference Wagner and Praprotnik2023). To investigate to what extent voters' perceptions of the government's performance moderate this effect, we estimate the interaction effect of coalition partnership and perceived government performance on out‐party dislike. Figure 1 visualizes the predicted values of that interaction from Model A.3 in the online Appendix. Predictions for out‐party dislike are shown on the y‐axis (z‐standardized), and the four different levels of perceived government performance as included in the CSES are on the x‐axis. Predictions for party dyads in a coalition are displayed in grey and predictions for party dyads not in a coalition in black. We find that dislike towards coalition partners is significantly lower, but only among voters who view the government's performance positively. Among these respondents, predicted out‐party dislike for party dyads in a coalition (in grey) is much lower than for party dyads not in a coalition (in black). Conversely, when comparing the predictions for voters who view the governing performance more negatively, dislike towards coalition partners is not reduced. Among these respondents, predicted out‐party dislike for party dyads in a coalition (in grey) does not differ significantly from party dyads not in a coalition (in black). Indeed, once we add perceptions of the government's performance to the model, coalition membership as such is not a significant predictor of out‐party dislike anymore.Footnote 6 In other words, the depolarizing effect of governing together on out‐party dislike does not occur among voters who believe that the government performed badly. A reduction in dislike is only observed for voters who evaluate the coalition's governing performance positively.Footnote 7

Figure 1. Predicted values of out‐party dislike: Interaction effect of perceived government performance and being part of a coalition.

Note: Detailed regression results can be found in Table A7 in the online Appendix.

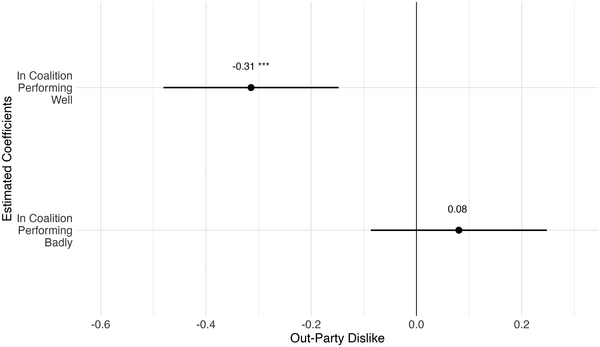

We run several robustness checks to ensure that our results are not sensitive to different model specifications, operationalizations of our central concepts or any of the control variables. As an initial test, we adopt an alternative modelling approach creating a categorical variable. This variable consists of the following three groups: (1) in‐party and/or out‐party not being in a coalition, (2) in‐party and out‐party being in a coalition that is perceived as performing (very) well and (3) in‐party and out‐party being in the coalition that performs (very) badly. Figure 2 visualizes the coefficients from Model A.4 in the online Appendix. It demonstrates that there is no significant difference in out‐party dislike between not being in a coalition (the reference category) and being in a coalition that is perceived negatively. Conversely, we find a significant and sizable decrease in out‐party dislike towards a coalition partner when that coalition is perceived as performing (very) well. These results demonstrate that our finding is robust to different specifications of the moderator.

Figure 2. Coefficient plot: Alternative specification of perceived government performance and being part of the coalition.

Note: The reference category consists of party dyads where the in‐party and/or out‐party are not part of the coalition. The two coefficients shown here include party dyads for which both parties are in the coalition and which respondents perceived as doing either (very) well or (very) badly. Detailed regression results can be found in Table A8 in the online Appendix.

One limitation of our data source is that the CSES collects data after the elections while the question with regard to perceived government performance refers to the previous (outgoing) government. This might lead to measurement error if respondents were confusing the previous (outgoing) with the new (incoming) government. To address this concern, we examine whether results are influenced by the distance between the election and the time of the interview. Importantly, 71 per cent of the sample was collected within a month after the elections making it unlikely that a new government was already in power by the time of the interview. Indeed, we do not find differences in effects conditional on the timing of the interview (see the online Appendix A.5). However, there might be other ways in which the formation of a new coalition may affect our results, for example, because the voter's in‐party that had previously joined the coalition, was not part of the new coalition after the elections. We thus test whether a voter's party staying in government or being voted out altered our proposed mechanism, but find no evidence for such an effect (see the online Appendix A.6).

We also test whether the interaction effect differs according to the strength of voters' partisan identification (see the online Appendix A.7). The attenuating effect of government performance is present at all levels of partisan strength, and, importantly, partisanship does not seem to further strengthen this interaction. In light of Horne et al.'s (Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023) finding that even past coalitions alleviate inter‐group animosity, we compute additional models which control for either the age of the respondent or past occurrences of a coalition as proxies for the frequency of a respondent's exposure to said coalition. We also ran an additional robustness check where the moderation for coalition membership takes into account whether an in‐ and out‐party have been in a coalition at any point in the past 20 years (approximately four election cycles) rather than only in the previous election cycle as in the original model. Results remain robust across different model specifications (see the online Appendices A.8 and A.9), suggesting that coalition histories do not appear to change the observed effects of perceived government performance.

In addition, we conduct two robustness checks which test whether the size and nature of a party in a coalition further moderates the interaction between government performance and coalition membership. First, we examine whether the seniority of a coalition partner matters, which we operationalize as the party holding the prime‐ministerial position. Other parties are considered to be junior parties. We find no heterogeneity in the interaction between coalition membership and perceived government performance on out‐party dislike based on whether that out‐party is considered senior or junior (see the online Appendix A10). Second, we examine the role of niche versus mainstream parties, which we operationalize by whether parties obtained less than 10 per cent of seats in parliament. In line with our findings for the seniority of a party, we find that the interaction effect of government performance on the link between coalition membership and out‐party dislike is not further moderated by whether a party is considered niche or mainstream at conventional significance levels (see the online Appendix A11).Footnote 8

The role of elite cues and ideological distance

Having established that the perception of the coalition's governing performance is an important moderator, we turn towards two avenues through which the positive effects of coalition governments on partisan animosity could be attenuated. First, we test whether the observed reduction is likely to be a consequence of citizens receiving different elite cues when a coalition is not performing well. It seems plausible that when a coalition is not performing well, elites begin attacking each other (again) which might reduce the positive aspects of being in a coalition. If this were true, we would expect to observe differences between ‘politically aware’ and ‘unaware’ voters. Building closely upon Zaller's (Reference Zaller1990) original operationalization, we use political knowledge as a proxy for political awareness.Footnote 9 The logic is that politically aware citizens are much more likely to receive and understand elite cues. We test a three‐way interaction between being in a coalition, perceived government performance and political knowledge to examine whether political awareness further moderates the interaction effect between the two former. Presented in online Appendix A.12, we do not find any evidence to support this mechanism. The effects do not differ between politically aware and unaware citizens making it appear unlikely that the attenuation effect related to poor governing performance is a consequence of the elite cues that voters receive.Footnote 10

Second, previous work has argued that voters perceive parties that their in‐party governs with as ideologically more similar, which subsequently reduces dislike between coalition parties and their supporters (e.g., Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023; Wagner & Praprotnik, Reference Wagner and Praprotnik2023). Therefore, we examine whether perceived government performance moderates the effect of being in a coalition on the perceived ideological distance from the coalition partner. Note that perceptions of ideological distance here are an alternative outcome variable, not a moderator. This, in turn, is then likely to affect voters' affective dislike towards their coalition partners.Footnote 11 We run the same models as in our main analysis and visualized predicted values in the online Appendix Figures A13 and A14. These results suggest that there is an association between perceived government performance and perceived ideological distance towards coalition partners. Particularly voters who view the government's performance as very positive, perceive significantly less ideological distance towards the other coalition parties. This pattern does not hold for those who rate government performance negatively. Thus, perceived ideological distance may indeed constitute a potential pathway through which perceptions of the government's performance moderate the effect between coalition membership and out‐party dislike. When parties govern together and their voters think that the government is doing very well, they perceive less ideological distance to the other coalition partners – and vice versa. This suggests a potential pathway for why a coalition that is perceived as unsuccessful might not be able to establish an overarching coalition identity and thus fails to reduce affective dislike.

The perception of ideological distance could also affect our results in another way: It appears possible that perceptions of government performance matter in particular for coalitions that consist of more ideologically diverse parties. This is because voters might be more forgiving towards parties perceived as ideologically close and vice versa. We thus test whether the interaction between coalition membership and perceived government performance is further attenuated by the perceived ideological distance between the in‐ and out‐party. When we test this three‐way interaction, we indeed find that the decrease in out‐party dislike as a result of being part of a successful coalition is only present towards coalition parties that are ideologically not too distant. In other words, coalitions that involve parties that are ideologically very diverse do not appear to depolarize voters much – even if they are perceived as successful (see the online Appendix A.15).

Endogeneity concerns

We observe that voters' perceptions of elite cooperation strongly moderate their affect on the group they cooperate with. A plausible concern one might have is, for example, that there are some underlying factors that drive both perceptions of the government's performance and out‐party affect. Addressing these endogeneity concerns with observational data is difficult. To raise this challenge, we include an alternative, more exogenous measure of government performance: the growth of a country's gross domestic product (GDP).Footnote 12 By testing the effect of GDP growth, a variable that should only affect citizens' perceptions of government performance and be fairly independent of voters' affective evaluations of out‐groups, we can alleviate some endogeneity concerns, albeit not all. When economic growth is low, voters should be dissatisfied with the governing performance of a coalition, and vice versa. Looking at the patterns visualized in Figures A.16 and A.17 in the online Appendix, it becomes clear that the results are remarkably similar to those observed when looking at perceptions of the government's performance.Footnote 13 That being said, these results are fairly sensitive to individual model specifications and in some models do not reach conventional significance. This was to be expected given that these factors only vary at the country‐ and year‐level and the interactions are underpowered. Nevertheless, this alternative specification points in the same direction as our main analysis and provides further evidence for our argument.Footnote 14

Discussion

The core empirical contribution of this research note is to demonstrate that the depolarizing effects of coalition governments documented by previous observational (e.g., Bantel, Reference Bantel2023; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2023; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022; Horne et al., Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023) and experimental (e.g., Bassan‐Nygate & Weiss, Reference Bassan‐Nygate and Weiss2022; Ekholm et al., Reference Ekholm, Bäck and Renström2022; Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2024; Wagner & Praprotnik, Reference Wagner and Praprotnik2023) research are conditional on citizens' perceptions of how successful such coalition governments are. Analysing CSES data, we show that the large positive effects of being in a coalition that previous research reports are primarily driven by those voters who think that the government is doing well. Among voters who think the government is not performing well, the effects are much smaller and insignificant. In other words, being dissatisfied with the government's performance nullifies the positive effects of being in a coalition. These results are robust to a variety of different specifications and hold regardless of the timing of the interview, whether one voted for a niche or mainstream party, the use of more exogenous measures of government performance, whether a voter's in‐party joined an incoming government or the strength of voters' partisan identity.

Theoretically, we build upon insights from the literature on inter‐group relations and out‐group affect (Allport et al., Reference Allport, Clark and Pettigrew1954; Brewer, Reference Brewer, Capozza and Brown2000; Pettigrew & Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006; Sherif, Reference Sherif1958), which stresses the relevance of ‘common goals and interests’. We make a contribution by arguing that when voters are dissatisfied with the coalition's governing performance, the ‘superordinate coalition identity’ is too weak to change the strong partisan identities. The ability of that coalition to change out‐party affect is thus reduced in these situations. Our analysis further examines two potential pathways through which this mechanism could operate: changing elite cues and changing perceptions of ideological proximity when coalitions are not doing well. Whereas we do not find any evidence for the former, perceived ideological distance decreases substantially between voters and their in‐party's coalition partners if they positively evaluate the government's performance.

Some exploratory analyses suggest that the depolarizing effects of elite cooperation are particularly difficult to achieve for coalitions that include ideologically diverse parties. Voters appear to be particularly unforgiving towards ideologically distant parties. Even if perceived as successful, these coalitions do not succeed at reducing out‐party dislike towards parties that are perceived as ideologically extremely distant. It is also fair to assume that these types of coalitions are more likely to be perceived negatively to begin with as it is harder for them to agree upon policy compromises (e.g., Laver & Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996; Laver, Reference Laver2003; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2008). We think this is a highly relevant finding given that mainstream parties increasingly appear to join such ‘diverse’ coalitions to keep radical right (and left) challenger parties at bay. This finding bears important implications for the debate on political and electoral potentials of coalitions in a contentious political landscape.

Relatedly, we also speak to the current political and academic debate concerned with the normalization of radical right parties through their representation in political institutions and their inclusion into governing coalitions. Especially, politicians argue that one could ‘demystify’ radical challengers by including them in coalitions and making them face the difficulties of policy‐making and governance. Scholars are overwhelmingly sceptical and have expressed concerns that radical right parties and their positions could become legitimized and normalized resulting in the erosion of democratic norms when the radical right is included in coalitions (e.g., Bischof & Wagner, Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Mendoza and Rooduijn2022; Praprotnik et al., Reference Praprotnik, Russo, Vanagt and Wagner2024; Valentim, Reference Valentim2024; Wagner & Praprotnik, Reference Wagner and Praprotnik2023). Although this research design is not optimized for analysing this question directly (mostly, due to the relatively small number of coalitions involving the radical right in our data), some of our findings suggest that this concern may be valid. We show, for instance, that niche parties – a related type of party – do profit from being part of a successful coalition government. This suggests that radical right parties once they manage to form a successful governing coalition, will likely benefit from the positive effects of coalition governments too. Previous work by Zaslove (Reference Zaslove2012) has identified several historical examples of coalitions with the radical right which have been deemed successful, such as in Switzerland, Italy and Denmark. Concerns that coalitions with radical right parties will further contribute to the normalization of extreme positions and the erosion of democratic norms thus appear to be justified.

More generally, this research note is embedded in a long tradition of work in comparative politics that is concerned with the role of political institutions in mitigating social and political conflict (e.g., Horowitz, Reference Horowitz1991; Lijphart et al., Reference Lijphart1999; Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2004). While majoritarian institutions like two‐party systems with winner‐take‐all elections are argued to provide a fertile breeding group for affective polarization because parties, by design, are pitted against each other (e.g., Dalton, Reference Dalton2021; Drutman, Reference Drutman2020), institutions that incentivize inter‐party cooperation are commonly argued to mitigate political conflict. And, although it is certainly true that political institutions do affect political culture and polarization, our results caution against the idea that by changing democratic institutions alone, societies can resolve challenges related to affective polarization. Our results suggest that it is the combination of institutions that foster successful elite cooperation and political parties that make such cooperation work that reduces polarization successfully. To put it differently, it also needs elites and parties who make such cooperation work – and voters who are willing to reward parties for it.

Despite the numerous robustness and endogeneity checks conducted, the research design employed here comes with three important caveats. First, while our findings did not find any evidence that the status of a party as mainstream or niche significantly altered our theorized mechanism, we regard it as an important task for future research to explore these cases in more detail, ideally with more fine‐grained data on radical and niche parties. Such research could – among other questions – examine whether our mechanism also holds for radical right parties or whether economic downturns exacerbate hostility toward niche parties in struggling coalitions. Second, the CSES collects data after elections while the question with regard to perceived government performance refers to the previous (outgoing) government. This might not only add noise to our data but also hide the positive short‐term effects that might occur when parties join a coalition in the first place. This component of our data could also explain why experimental studies investigating the short‐term effects of coalition signals on affective dislike paint a more optimistic picture of coalitions' depolarizing potentials than our results do. Future research should therefore look into ways of testing the observed mechanism with data collected at different points throughout the electoral cycle. Third, our observational setup does not enable us to make causal claims – despite our efforts to address potential endogeneity concerns. Taken together, these limitations all call for additional (quasi‐)experimental methods to assess when and how elite cooperation reduces affective polarization.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Ida B. Hjermitslev, Markus Wagner and the members of the PARTISAN research group at the University of Vienna for their feedback on an earlier version of this paper. We are also grateful to Ruth Dassonneville and Romain Lachat for organizing the summer school on ‘Electoral Democracy in Danger’, where this project originated. We wish to thank the four anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. This work was supported by the Einstein Stiftung Berlin (EVF‐BUA‐2022‐691) and the Belgian FNRS‐FWO EOS project NotLikeUs (EOS project no. 40007494; FWO no. G0H0322N; FNRS no. RG3139). This publication reflects the authors' views. The funding agencies are not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Data replication files are available at https://osf.io/pfgzy/

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Data S1