Introduction

Most political parties have youth wings (Allern and Verge Reference Allern, Verge, Scarrow, Webb and Pogunktke2017). Given that these are ideologically aligned with their senior party, members reasonably view their political engagement as both a means of supporting the senior party and influencing it in a specific political direction. However, previous research demonstrates that the motivations for political engagement vary among different members (Bale et al. Reference Bale, Webb and Poletti2020; Bolin et al. Reference Bolin, Backlund and Jungar2023; Weber Reference Weber2020). These motivations potentially impact their view of the youth wing’s role in connection with the senior party. As researchers have only to a limited extent explored this issue empirically, this paper examines the perspectives of youth wing members regarding their organisation’s role in relation to the senior party. Specifically, it explores the extent to which members believe that the primary role of the youth wing should be to influence or support the senior party. Drawing on theoretical insights from the literature on incentives for political engagement, this study further examines whether there is a connection between members’ political and career-related motivations for their political involvement and their views of the youth wing. Empirically, the study utilises data from a survey of all Swedish parties’ youth wings. The results indicate that individuals with career-related incentives are more likely to perceive the youth wing primarily as a supportive organisation, while members who are motivated by political reasons are more likely to believe that their organisation should primarily influence the senior party.

The paper concludes with a discussion of how this study contributes to the literature on the decline in party membership by highlighting a potential gap between what young people seek from their political engagement and what existing party organisations actually offer. Since there is a structural bias in the literature on parties’ challenges in retaining and recruiting members that suggests that significant societal changes are the major cause of the long-term decline, scholars have recently called for greater emphasis on individual parties and their organisational behaviour (van Haute and Ribeiro Reference van Haute and Ribeiro2022). Assessing the extent to which parties meet the demands of their members is arguably a crucial aspect of this situation.

The paper proceeds as follows. The following section discusses the role that youth wings play in relation to the senior party before the paper proceeds to examine the potential link between members’ incentives for their political engagement and their perceptions of the youth wing’s role. Following this, there is a section that presents the study’s data and methodology before the penultimate section presents the empirical analysis. The paper concludes with a summary of the findings and a discussion on their broader implications.

The role of party youth wings

Many political parties maintain connections with various social groups. The forms of these relationships vary from being organisationally entirely independent but affiliated with the party, to being a subsidiary organisation of the party with entirely overlapping memberships. The literature primarily emphasises the parties’ relationships with external interest groups such as the social democrats’ connections to labour unions, agrarian parties’ relationships with farmer organisations and right-wing parties’ ties to the business sector (Allern and Bale Reference Allern and Bale2012). Some researchers, however, explicitly distinguish between interest organisations that exist independently of the political party from those that have been created in the realm of the party. Poguntke (Reference Poguntke, Katz and Crotty2006) thus distinguishes between external and internal collateral organisations, while Allern and Verge (Reference Allern, Verge, Scarrow, Webb and Pogunktke2017) use the terms non-party organisations and party sub-organisations.

Youth wings are the most common form of such party sub-organisations. According to the Political Party Database, as many as 78 per cent of the parties have a youth wing. The second most common sub-organisation, women’s organisations, is, by comparison, present in 41 per cent of the parties (Allern and Verge Reference Allern, Verge, Scarrow, Webb and Pogunktke2017). Despite the presence of youth wings in many political parties, research in this area remains limited. Some research focuses on young party members, but a specific focus on youth wings and their members is uncommon (but see, e.g. Ammassari et al. Reference Ammassari, McDonnell and Valbruzzi2023; Bolin et al. Reference Bolin, Backlund and Jungar2023; de Roon Reference de Roon2020; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004; Rainsford Reference Rainsford2018; Silvia and Costa 2024/25). Moreover, there remains a notable scarcity of research exploring the relationship between the senior party and the youth wing and specifically, about the role that the youth wing plays in relation to the senior party. This paper addresses this question by focusing on members’ perceptions of the youth wing’s role in relation to the senior party.

The link between parties and interest organisations operates as a mutual exchange where both sides assume they gain added value from establishing a relationship. On one hand, the interest organisation is an important provider of various goods to the senior party. In such a supporting role, the organisation helps the party to establish local foundations, integrate it into society, convey decisions throughout the party hierarchy, recruit members and provide a platform for elites (Dilling Reference Dilling2023). On the other hand, interest organisations expect to get something in return for their support. Of primary interest in this regard is gaining the possibility to influence the overall trajectory of the senior party ideologically and policywise (Røed Reference Røed2023).

The distinction between a support role and a role as an influencer is also found in the few studies that specifically deal with party youth wings. In a study of membership in Dutch youth wings, de Roon (Reference de Roon2020) suggests that these may be important in a supporting role of the senior party as a provider of linkage, recruitment and socialisation. The literature recurrently considers youth wings as supporters of their senior party by acting as a recruitment channel for future politicians and party workers. Scholars argue in the literature on party membership decline that political parties not only struggle to keep their members, but also fail to rejuvenate their memberships, as young people are even less attracted to becoming members than their older cohorts. Youth wings are hence seen as the main recruitment pool for political parties. In a similar vein, Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004) show that a large share of today’s leading politicians started their political careers as members of youth wings. Others highlight how the youth wing may support the senior party by being important for educating members in campaigning, fund-raising, communication and party organisation (Mycock and Tonge Reference Mycock and Tonge2012).

At the same time, there is an expectation that the senior party exchanges benefits for the youth wing’s support. Youth wings are independent groups and important in the development of policies and as representatives of young people (Ødegård Reference Ødegård2014). As such, youth wings mobilise young people and provide ‘mechanisms for the voices of young members to be heard’ (Berry Reference Berry2008, p. 370). From this point of view, youth wings are akin to pressure groups that aim to influence the organisation, policies and strategies of the senior party. Given their organisational affinity, one might expect youth wings to have political agendas similar to those of their senior parties. However, youth wings are generally more radical than their senior parties (Bruter and Harrison Reference Bruter and Harrison2009; Russell Reference Russell2005; Weber Reference Weber2017). Further, although youth wings can potentially have a significant ideological impact (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe2004), senior parties primarily consult them on youth-related political issues and are reluctant to give them too much influence for fear of alienating older members and voters (Mycock and Tonge Reference Mycock and Tonge2012). Previous research also suggests that senior parties generally exert strong control over their youth wings, although important variations exist. Some youth wings are granted representatives in decision-making bodies in the senior parties, whereas others lack any formal power (Russell Reference Russell2005).

Of course, youth wings are not necessarily either supporters or influencers but fulfil both roles at the same time. However, to what extent their members prioritise one over the other may vary. What this variation looks like is the topic of this paper. The next section turns to what may account for variations in members’ perceptions of these roles.

An incentive-based perspective on the role of party youth wings

This study draws on the literature on the incentives that drive citizens’ engagement in politics to explore variations in how members perceive the role of the youth wings. Based on the widely used general incentives model (e.g. Whiteley and Seyd Reference Whiteley and Seyd1998), Bruter and Harrison (Reference Bruter and Harrison2009) devise a trichotomous typology that differentiates between members’ motives for their political engagement: moral-minded members, professional-minded members and social-minded members.

Bruter and Harrison (Reference Bruter and Harrison2009) conclude that ‘moral-minded’ individuals make up the greatest share of young party members. About 40 per cent of the respondents in their survey are classified in this way, echoing research which finds that citizens primarily have political motives for their party engagement (Bale et al. Reference Bale, Webb and Poletti2020; Gauja and van Haute Reference Gauja, van Haute, van Haute and Gauja2015; Heidar and Kosiara-Pedersen Reference Heidar, Kosiara-Pedersen, Demker, Heidar and Kosiara-Pedersen2019). In her study of young party members in the German Social Democrats, Weber (Reference Weber2020) finds that as many as 93 per cent became members as they wanted to ‘change something in society’ and 75 per cent stated they enrolled to ‘influence politics of the party’. The main motivation among young citizens, then, is political in nature: ‘to express and assert their newly crystallised moral beliefs’ (Bruter and Harrison Reference Bruter and Harrison2009, p. 1264) and to influence their party and change society (Silvia and Costa 2024/25; Weber Reference Weber2020). Rather than being loyal to the party, they see their youth wing as a pressure group for exerting political influence. Based on this reasoning, it is expected that:

H1 Members who engage based on political incentives are more likely to believe that the youth wing’s primary role is to influence the senior party’s policies.

While political incentives are the most common incentives among members, a fair share of members also think that material incentives are important. Bruter and Harrison (Reference Bruter and Harrison2009) found that about 26 per cent of the respondents in their study were what they referred to as, ‘professional-minded members’ who aspire to a future role in the senior party. These members are happy with the way internal democracy works and take part in activities that would benefit the senior party, such as election campaigning. Similarly, in the study of young party members in the German Social Democrats, 56 per cent of the respondents stated that improving their networks and contacts was an important motivation for their decision to join the party, whereas 35 per cent indicated that a future in party office or as an elected politician were important motivations (Weber Reference Weber2020). Finally, a recent study on Swedish youth wing members concludes that even if material incentives are less important than political and social ones, the majority of the respondents also stated that the former were important reasons for their joining the youth wing (Bolin et al. Reference Bolin, Backlund and Jungar2023). These members are thus motivated mainly by career-related incentives. They are likely to see party membership as a springboard to a future career within the senior party: Their aim is to become elected politicians or paid party workers (Bruter and Harrison Reference Bruter and Harrison2009; Fjellman and Rosén Sundström, Reference Fjellman and Rosén Sundström2021; Weber Reference Weber2020). Career-related incentives are not only important motivators for young people to join youth wings, they are also likely to bolster activism on behalf of the party organisation (Fjellman and Rosén Sundström, Reference Fjellman and Rosén Sundström2021). Whiteley and Seyd (Reference Whiteley and Seyd1996, p. 219) suggest that ‘activism can be regarded as an investment which must be made if the individual has ambitions to develop a future career in politics’. This is also in line with the findings of Webb et al. (Reference Webb, Bale and Poletti2020), which show that people who aspire to a career in politics are also those who are most motivated to engage in election campaign activities. In short, the view that members’ engagement in party politics is a way of promoting a political career is compatible with the view of party youth wings in the literature as supporters of the senior party leading to the following hypothesis:

H2 Members who engage based on career-related incentives are more likely to believe that the youth wing’s primary role is to support the senior party’s policies.

Previous studies on young people’s motivations for engaging in politics have, in addition to political and career-related reasons, also highlighted social incentives. These socially minded members see their membership mainly as a way to engage in discussions and to meet new friends or like-minded people (Bruter and Harrison Reference Bruter and Harrison2009; Weber Reference Weber2020). Social motivations are common among party members. In the Bruter and Harrison (Reference Bruter and Harrison2009) study, the group of social-minded members is nearly as large as moral-minded members, and in the aforementioned study of young members in the German Social Democrats, 74 per cent of respondents stated that they want to meet like-minded people. Previous research indicates that socially minded members, in comparison to those primarily motivated by politics or career ambitions, are both less active and less inclined to continue their political engagement as they grow older (Bruter and Harrison Reference Bruter and Harrison2009). The relatively limited interest in both political activity and future political engagement suggests that social motivations do not significantly correlate with either a supportive or influential role for the youth wing.

Data and methods

This study evaluates the hypotheses using data from a web survey of the youth wing members of all eight Swedish parliamentary parties. Sweden offers a relevant case to test the hypotheses since all parties have a long tradition of having close ties to well-organised youth wings that are both important supporting organisations for the senior party and platforms for young people to develop and voice their opinions. Like their senior parties, most Swedish youth wings have lost members over time. However, membership figures have stabilised during the last decade. When the web survey was fielded in late 2020, there were approximately 25,000 members in the youth wings (see Appendix A1).There are about as many female members as male ones, and about two thirds of the members are younger than 23 years old (Bolin and Backlund 2021).

With only one exception, the youth wings are independent from their senior parties insofar as they are free to elect their own leaders and develop their own political platforms. Some of the youth wings have formal representation in their senior parties, although the small number of party board seats and congress delegates are primarily symbolic rather than of real significance (Bolin Reference Bolin and Hagevi2019). The Young Swedes is the only youth wing that is not independent as it is formally an intra-party section of its senior party, the radical right Sweden Democrats.

Members who were at least 15 years old and who had provided their youth wing with an email address were invited to take part in the survey.Footnote 1 In total, there were 2906 responses. The response rate of 17 per cent is similar to recent comparable studies (e.g. Kölln and Polk Reference Kölln and Polk2017). As the response rate varies between the organisations, from 5.6 to 44.6%, the analysis includes organisational membership as a control variable.

Data are not weighted since not all youth wings provided information on the distribution of gender and age in their respective memberships. For the six organisations that did provide this information, however, the respondents are largely representative in terms of gender and age. Still, caution is needed to not generalise the findings too far as it is possible that systematic differences exist between respondents and non-respondents in other respects.

Table A2 in the Appendix presents descriptive data for the variables used in the study. Influence is the first dependent variable. It is based on a survey question measuring the extent to which the respondent agrees with the following statement: ‘The most important role of the youth wing is to influence the policies of the senior party’. Four responses are possible: agree completely, agree somewhat, disagree somewhat and disagree completely. The second dependent variable is support. This variable is based on the survey question asking the extent to which the respondents agree with the statement: ‘The most important role of the youth wing is to support decisions taken by the senior party’. The response scale was the same one as for the above-mentioned survey question. The survey presented these two questions immediately following one another and on the same page to the respondents. This should provide good conditions for interpreting their respective answers as being answered in relation to each other.

The study uses two indices to test the hypotheses and measure the extent to which respondents’ political engagement is motivated by political and career-related reasons. The indices are based on similar survey questions to those that have been used in previous research to operationalize the various incentives (Bolin et al. Reference Bolin, Backlund and Jungar2023; Weber Reference Weber2020).

In the analysis, the first hypothesis is tested by an index variable political that indicates the degree to which members are motivated by political incentives. The index is based on three survey questions asking whether a respondent has remained a member of the youth wing because they (1) ‘can change something in society’, (2) ‘can make my voice heard’ and (3) ‘can influence the party’s policies’. The analysis tests the second hypothesis using an index variable career indicating the degree to which membership in the youth wing is motivated by career-related incentives. This variable is based on three survey questions asking whether a respondent has remained a member of the youth wing because they (1) ‘can improve their network and make contacts’, (2) ‘are interested in working for the party’ and (3) ‘are interested in running for office one day’. The study also includes a social incentives index based on two survey questions asking whether a respondent has remained a member of the youth wing because they (1) ‘can meet like-minded people’, and (2) ‘can participate in activities with the party’. All questions are measured on the four-grade agree/disagree scale described above, and the indices are created by combining the survey items using principal component analysis.Footnote 2 The indices are then rescaled from 0 to 10, where 10 indicates that the incentives are maximally important.

The analysis also includes the following control variables. Distance measures the absolute distance between the respondent’s self-placement on a 0–10 left/right scale and the position of the senior party as estimated by the same respondent. The rationale for this variable is that members who place themselves far from the senior party are less likely to support its decisions and more likely to want the youth wing to influence the policies. Radicalism, meanwhile, measures the absolute distance from a respondent’s self-placement on the left/right scale to the midpoint of this scale (5). Here, it is expected that more radical members are less inclined to view the youth wing as a support team for the senior party and more likely to view its role as an influencer. Finally, left–right indicates a respondent’s absolute left/right self-placement, and it is included to account for potential differences in this regard.

Interest measures the degree of political interest, using the survey question: ‘On a scale from 0–10, how interested in politics would you say you are?’ Education measures the highest level of education obtained on a scale from 1 to 10.Footnote 3 Age indicates the respondent’s age in years. Gender is a dummy variable coded 0 for male and 1 for female. Lastly, the analysis includes a categorical variable Organisation to test whether the hypothesised effects can be found across different youth wings and, as mentioned above, to account for potential differences caused by varying response rates across the organisations.

A test of proportionality of odds across response categories (using the omodel command in Stata) shows a violation of the proportional odds assumption. The hypotheses are, therefore, tested using multinomial logistic regression models. They are estimated with robust standard errors to account for heteroscedasticity.Footnote 4

Empirical results

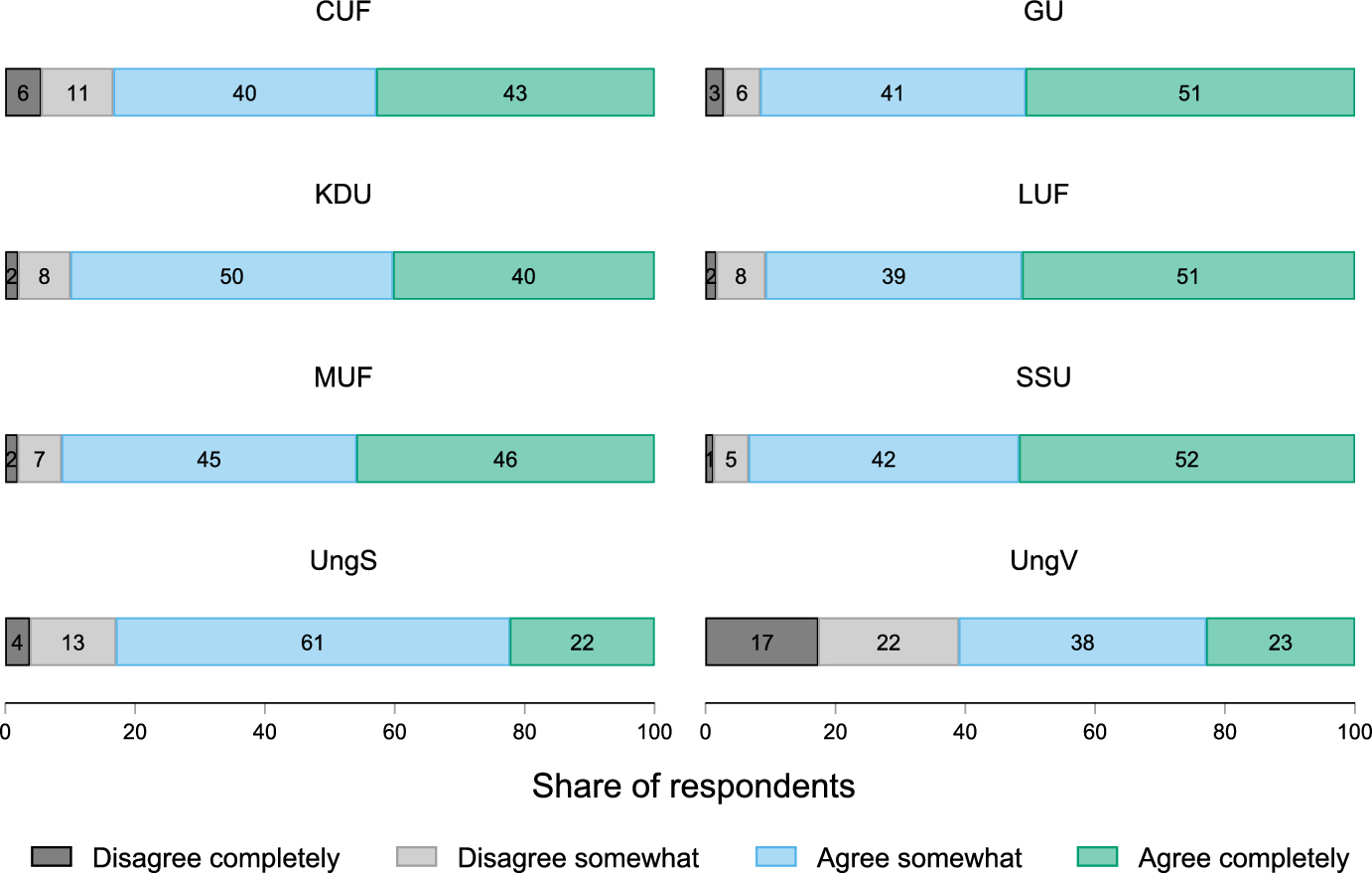

Approximately 85 per cent of the respondents either agree somewhat (44.3%) or agree completely (40.6%) with the statement that the most significant role of the youth wing is to influence the policies of the senior party, whereas about 15 per cent either disagree completely (5.0%) or disagree somewhat (10.1%) with the statement.

Figure 1 shows that there is some variation across youth wings. Notably, members of the Left Party’s youth wing (Young Left) stand out. While the percentage of members who agree that the influence role is the most important ranges between 83 and 93 per cent for the other youth organisations, only 61 per cent of the Left Party youth wing members hold this view.

Fig. 1 Distribution of members’ views on the youth organisation’s role as influencers to the senior party

Note: Swedish abbreviations and mother party in brackets. CUF: Centerns ungdomsförbund (Centre Party); GU: Grön ungdom (Green Party); KDU: Kristen demokratisk ungdom (Christian Democrats); LUF: Liberala ungdomsförbundet (Liberals); MUF: Moderata ungdomsförbundet (Moderates); SSU: Socialdemokratiska ungdomsförbundet (Social Democrats); UngS: Ungsvenskarna (Sweden Democrats); UngV: Ung vänster (Left Party)

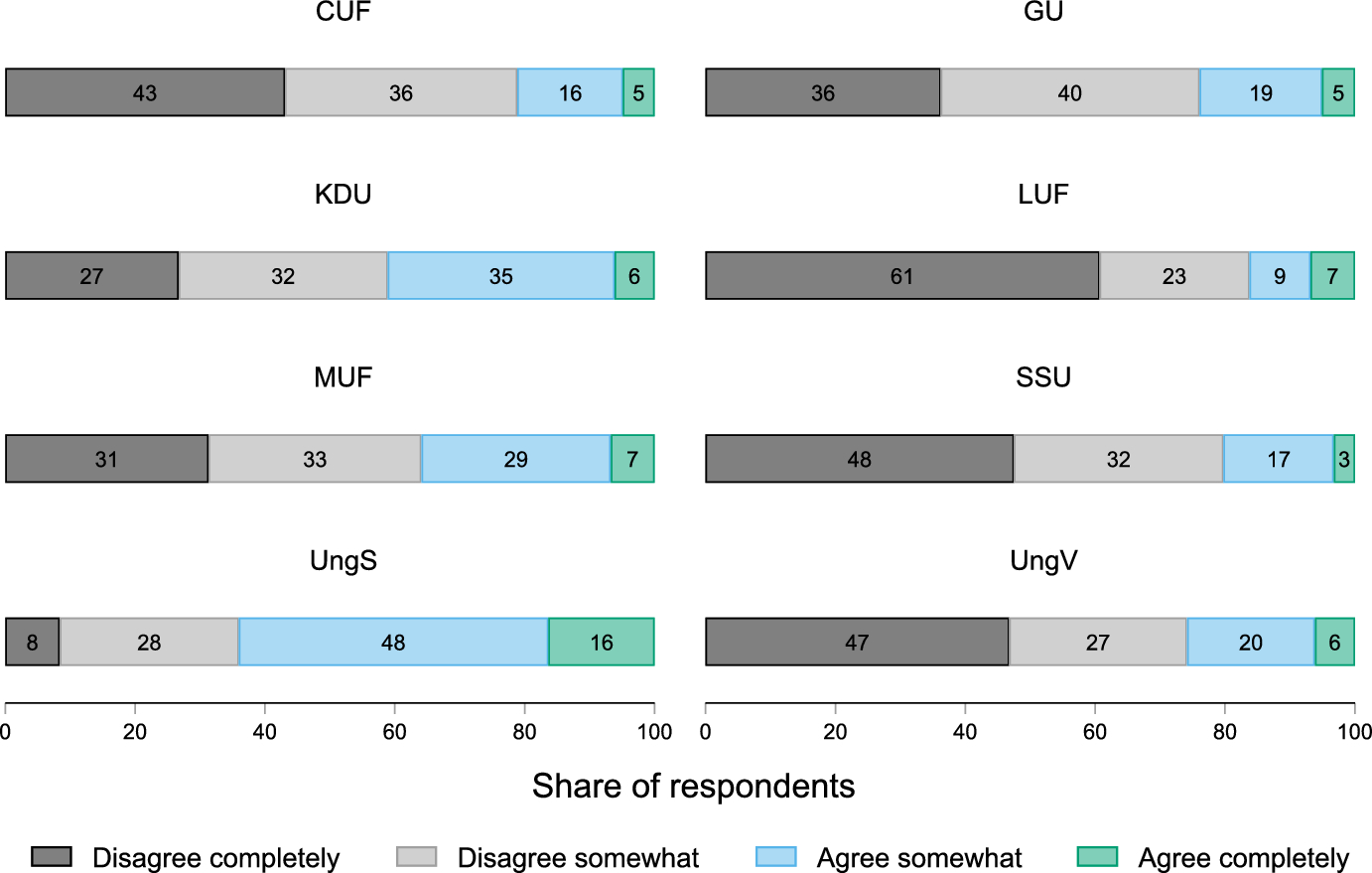

The overall trend regarding whether the youth wing should primarily support the decisions made by the senior party is almost the opposite of the distribution concerning whether the youth wing should predominantly exert influence on the senior party. Almost 70 per cent either disagree completely (37.4%) or disagree somewhat (31.2%) with the statement that the youth wing should primarily support the senior party. About 25 per cent of the members agree somewhat, whereas less than 7 per cent agree completely with the statement that the youth wing’s most important role is to support decisions taken by the senior party.

The data presented in Fig. 2 display that there are relatively large differences across the eight different youth wings. The share of members that agree to some degree (‘Agree somewhat’ and ‘Agree completely’ combined) ranges from 16 per cent for the Liberal’s youth organisation (LUF) to as many as 64 per cent for the Sweden Democrats’ counterpart (Ungsvenskarna). Even though there is some spread among the other youth wings, the Young Swedes stand out as the only one where a majority of the members supports the senior party. Given that the Young Swedes organisationally differ from other youth wings in that they are not independent of the senior party, this difference is expected.

Fig. 2 Distribution of members’ views on the youth organisation’s role as support to the senior party

Note: Swedish abbreviations and mother party in brackets. CUF: Centerns ungdomsförbund (Centre Party); GU: Grön ungdom (Green Party); KDU: Kristen demokratisk ungdom (Christian Democrats); LUF: Liberala ungdomsförbundet (Liberals); MUF: Moderata ungdomsförbundet (Moderates); SSU: Socialdemokratiska ungdomsförbundet (Social Democrats); UngS: Ungsvenskarna (Sweden Democrats); UngV: Ung vänster (Left Party)

The comparison of these distributions firmly establishes the perception that the youth wing’s most crucial role is to influence the senior party and is considerably more common than the perception that it should support the senior party. The observed differences between youth wings also strengthen the choice to include a control for this in the multivariate analysis.

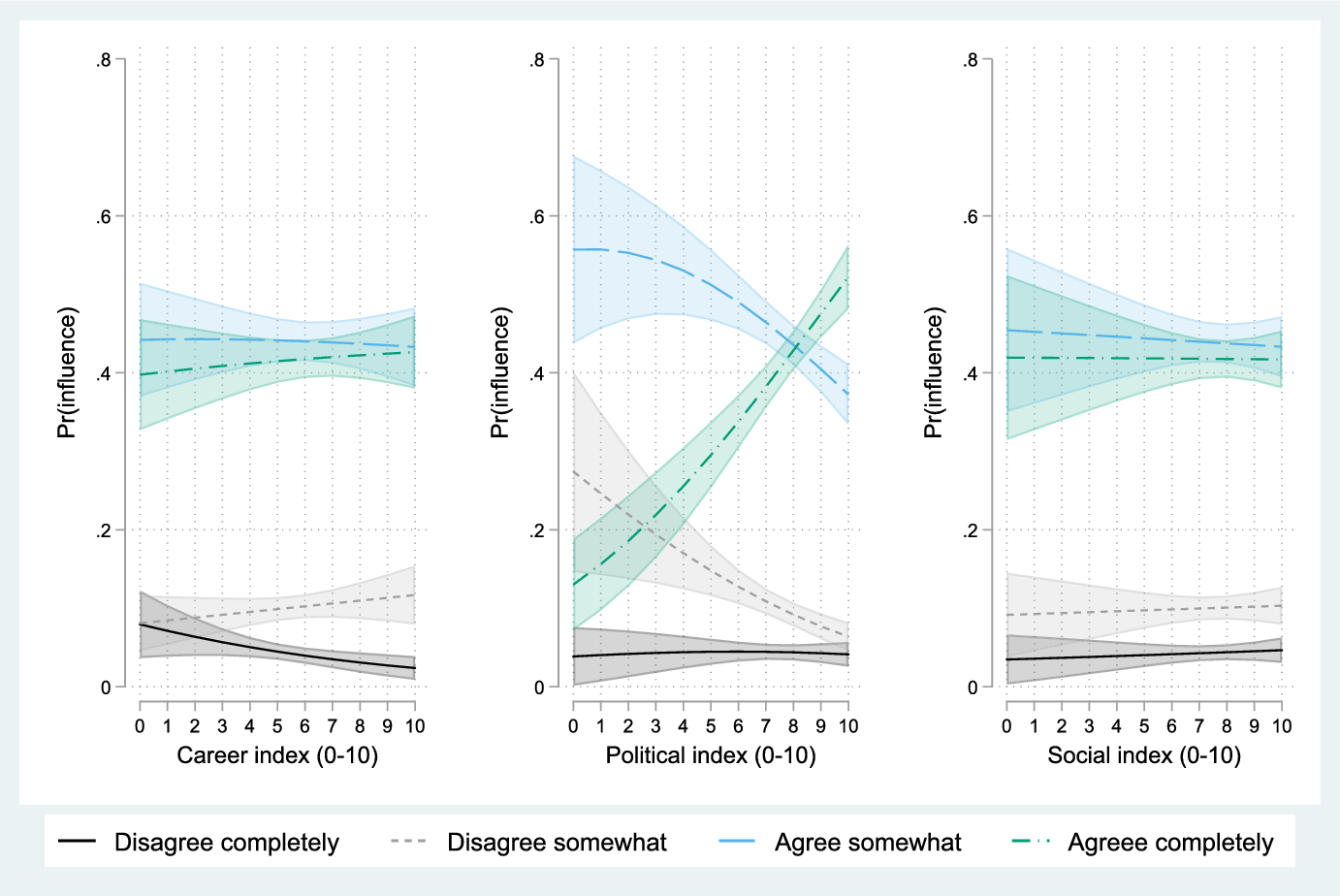

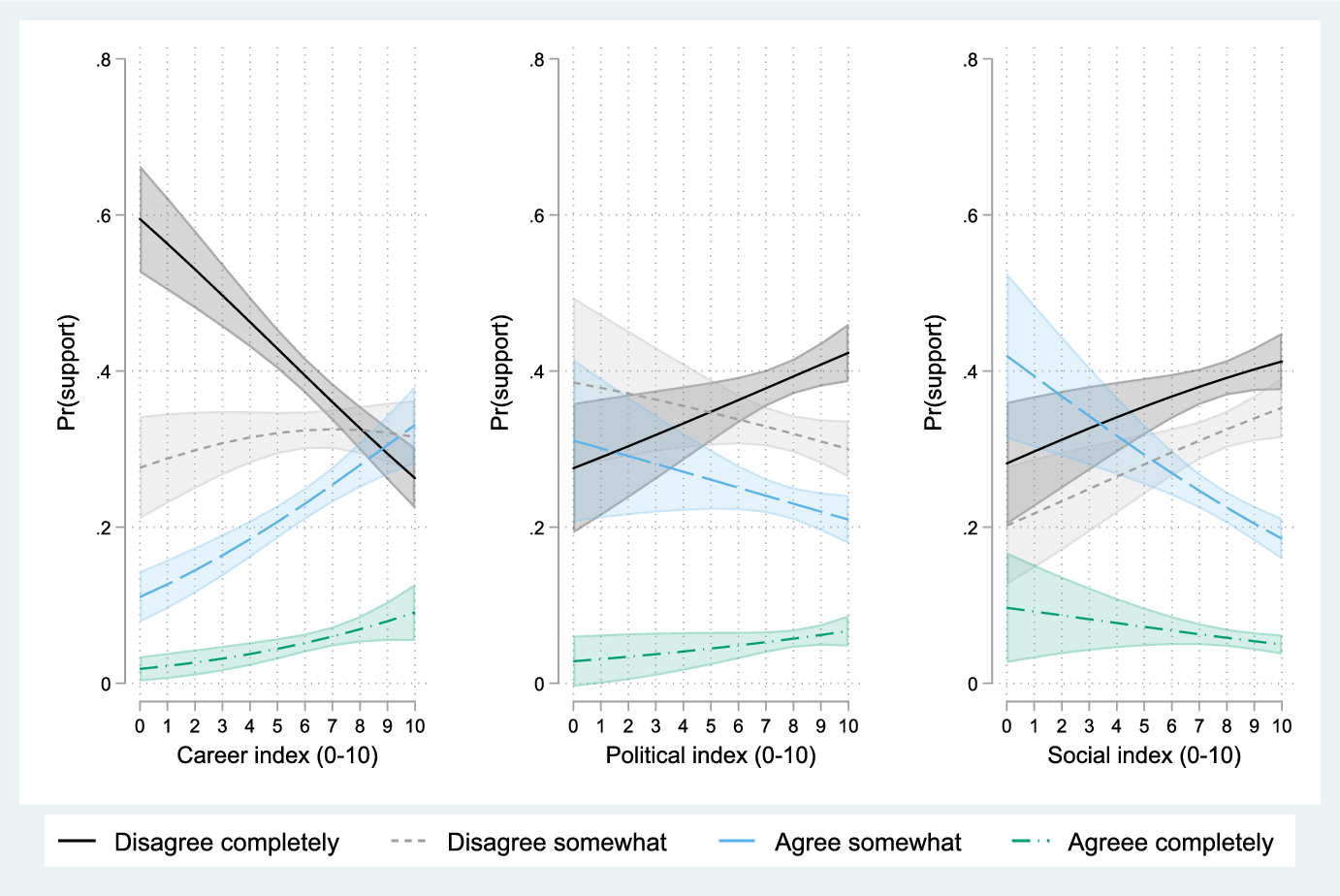

The hypotheses are assessed graphically in Figs. 3 and 4 (see also Tables A3 and A4 in the Appendix), where marginal plots indicate the probabilities of considering the youth wing’s primary roles as influencing and supporting the senior party based on different levels of agreement with the three different incentives for political engagement.

Fig. 3 Effect of members’ incentives on the role of youth organisations as influencers

Fig. 4 Effect of members’ incentives on the role of youth organisations as supporters

Figure 3 presents the effects of the three different incentives on the likelihood of considering the youth wing’s primary role as influencing the senior party. It is evident that, in accordance with Hypothesis 1, there is an effect of the political motives. The middle panel shows that the crucial dividing line is between those who agree completely with the statement about the youth wing’s influencing role and the other categories. While there are relatively few observations at lower levels of the political incentives index, it is illustrative that a shift from the lowest to the highest value on the x-axis corresponds to a fourfold increase in probability (from approximately 13% to around 52%) of 'agreeing completely' that the youth wing’s primary role is to influence the senior party.

The relatively parallel lines in the left and right panels indicate that the members’ level of career-related ambitions and social incentives does not influence their perception of the youth wing’s influencing role.

Figure 4 displays the effects of the incentive indices on the perception that the youth wing’s primary role is to support the senior party. As evident in the left panel and in accordance with Hypothesis 2, there is a positive correlation between the degree of career-related motives and agreement with the statement that the youth wing’s primary role is to support the decisions of the senior party. The stronger the career-related motives a member possesses, the higher the likelihood that the member also agrees to some extent with the statement regarding the supportive role of the youth wing.

Conversely, it is apparent that the probability of belonging to the most sceptical group, those who completely disagree with the support role, decreases substantially with increasing levels of career ambitions. The expected probability of belonging to the disagree completely category decreases by more than half (from approximately 59% to around 27%) when moving from the lowest level of political motives to the highest level. A corresponding shift along the x-axis implies a threefold increase in the probability of belonging to the 'agree somewhat' category (from approximately 11% to around 33%) and more than a fourfold increase, albeit at a very low level, for the 'agree completely' category (from approximately 2% to around 9%).

The middle and right panels show indications of negative correlations between both political and social incentives and support for the senior party. It thus appears that individuals engaging in the youth wing for political and social reasons are less likely to perceive their organisation primarily as a supporter to the senior party.

Concluding remarks

Despite most parties having youth wings, there is a lack of systematic research on the relationship between them. This paper initiates a research debate on this issue, by examining how members perceive the role of youth wings in relation to the senior party.

The analysis shows that most members do not agree with the idea that the main role of their youth wing is to support the senior party. The fact that only about 30 per cent of the respondents agree with this statement, whereas about 85 per cent see their youth wing as an influencer of the senior party are strong indications that we should problematise some of the most recurring statements in the literature on youth wings as primarily support teams. Research that suggests that youth wings ‘first and foremost are important as recruiters of members and future elected representatives to their senior parties’ (Ødegård Reference Ødegård2014, p. 135), or that this assumes that they ‘are underpinned by the dual objectives of retaining existing members and activists […] and in contributing to the parent party’s attraction of new members and activists’ (Berry Reference Berry2008, p. 370) is not necessarily wrong. It does, however, seem to be founded in a senior party's perspective, rather than that of the youth wing and its members. According to the members, we should instead view the influencing role of the youth wing as primary.

This finding has implications for the extensive debate on the decline in party membership. Much of the existing research points to how the long-term decline can be traced in significant structural changes. While this research is relevant for understanding the overall trends, it is less accurate in comprehending variations both between countries and within countries (van Haute and Ribeiro Reference van Haute and Ribeiro2022). Thus, there are strong arguments for focusing on party-internal factors. Importantly, researchers as well as party leaders should emphasise the significance of parties providing what their potential members demand. As members of youth wings primarily want influence and not just to support the senior party, it is important for parties to assess to what extent they are actually open to the opinions of youth wings, even on issues that are not specifically related to youth issues. Youth wings are a crucial recruitment channel for political parties (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Stolle and Stouthuysen2004; Kosiara-Pedersen 2024/25). However, if the parties only emphasise the supportive role of their youth wings, they risk recruiting only careerists who follow the senior party loyally without demanding any influence over politics. Although this may seem convenient, there is a risk that many young people may lack any incentive for becoming members of a political party. Even if they are politically interested, many young people choose not to become members of political parties or their youth wings. One important reason for this is that parties do not offer young people what they want (Cammaerts et al. Reference Cammaerts, Bruter, Banaji, Harrison and Anstead2014). Young people who want to get involved mainly for political reasons—to change society—might in that case turn to alternative forms of political engagement, resulting in the continued decline of party membership.

The results of this study indicate that members of relatively old and well-organised party youth wings, who have close relations to their senior parties, do not primarily see their organisations as support teams. As there is little research on young party members and youth wings outside of the long-established democracies of Northern European (but see, Alarcón González and Real-Dato Reference Alarcón González and Real-Dato2021; Dobbs 2024/25; Malafaia et al. Reference Malafaia, Menezes and Neves2018), a reasonable question for future research is to investigate whether similar patterns are present in newer democracies and/or in newly established youth wings of older parties.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-025-00527-7.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2023 annual congress of the Swedish Political Science Association. The author thanks all commentators for helpful suggestions. The author is also grateful to Daniel Stockemer as well as the anonymous reviewers of European Political Science for their helpful and constructive comments on this manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Mid Sweden University. This work was supported by the Swedish Agency for Youth and Civil Society grant number dnr: 0671/19.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest The corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.