Introduction

It is a long-standing claim in political science that economic inequality leads to dissatisfaction with democracy and concomitant distrust in politicians and the state (Anderson & Singer, Reference Anderson and Singer2008) – what may broadly be labelled ‘political system support’. In short, the argument is that high economic inequality is a signal that the democratic system does not deliver on an equal distribution of resources, which in turn fosters the perception, among large segments of society, that the government – and the political system more broadly – does not work for them (Anderson & Singer, Reference Anderson and Singer2008; Bartels, Reference Bartels2017; Solt, Reference Solt2008). In response, citizens become less supportive of democracy as a form of governance, as well as less trustful of its central institutions and representatives. Extending this reasoning, it may be argued that those to whom inequality is the biggest disadvantage – that is, those on the bottom of the income distribution – should be more disapproving of the system and those who run it when confronted with inequality. Conversely, those on top of the income distribution, whose preferences are to a larger degree reflected in the enacted policies (Bartels, Reference Bartels2017; Gilens, Reference Gilens2005), should be more favourable to the system and its stewards.

In line with this theoretical conjecture, empirical research has documented a negative relationship between economic inequality and citizens' support for the political system across a range of indicators, including satisfaction with democracy (Anderson & Singer, Reference Anderson and Singer2008; Andersen, Reference Andersen2012; Krieckhaus et al., Reference Krieckhaus, Son, Bellinger and Wells2014), institutional trust (Anderson & Singer, Reference Anderson and Singer2008; Lipps & Schraff, Reference Lipps and Schraff2021; Rahn, Reference Rahn2005), political trust (Zmerli & Castillo, Reference Zmerli and Castillo2015; Rahn, Reference Rahn2005; Bienstman et al., Reference Bienstman, Hense and Gangl2024) and external political efficacy (Norris, Reference Norris2015; Bienstman et al., Reference Bienstman, Hense and Gangl2024). Conversely, there is limited evidence suggesting that the negative relationship between inequality and political system support is stronger among the economically disadvantaged (Andersen, Reference Andersen2012; Goubin & Hooghe, Reference Goubin and Hooghe2020) – if anything, the relationship is weaker among the poor (Krieckhaus et al., Reference Krieckhaus, Son, Bellinger and Wells2014; but see Solt (Reference Solt2008) for a confirmatory finding regarding political engagement).

However, common for all previous studies is the focus on inequality at a very aggregate level – nations or larger regional units such as US states. This is problematic for the reasons encapsulated in the following quote from a widely cited study regarding the broader effects of inequality (see also Loveless & Whitefield (Reference Loveless and Whitefield2011); Bartels (Reference Bartels2017); Norton & Ariely (Reference Norton and Ariely2011) on this point):

Most such arguments crucially assume that ordinary people know how high inequality is, how it has been changing, and where they fit in the income distribution. […] we show that, in recent years, ordinary people have had little idea about such things. What they think they know is often wrong. Widespread ignorance and misperceptions emerge robustly, regardless of data source, operationalisation and measurement method. (Gimpelson & Treisman, Reference Gimpelson and Treisman2018, p. 27).

There is thus little to suggest that people have an accurate understanding of inequality at the national level or highly aggregate regional levels, which in turn challenges claims about its negative effects. The lack of correspondence between national-level inequality and people's perception of inequality likely reflects that highly aggregate contextual measures are poor measures of people's everyday experiences due to, inter alia, segregation along income lines (Reardon & Bischoff, Reference Reardon and Bischoff2011). By contrast, local-level measures capture palpable everyday experiences with inequality. From related research, we know that people use such local experiences as a heuristic when making inferences about societal economic aggregates (Bisgaard et al., Reference Bisgaard, Dinesen and Sønderskov2016) and when forming opinions about redistribution (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Dinesen and Sønderskov2024; Sands & de Kadt, Reference Sands and de Kadt2020) and out-groups (Enos, Reference Enos2017). Correspondingly, we expect people's support for the political system to be partly informed by their local experiences of economic inequality.Footnote 1

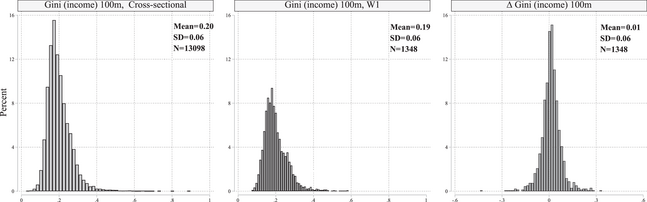

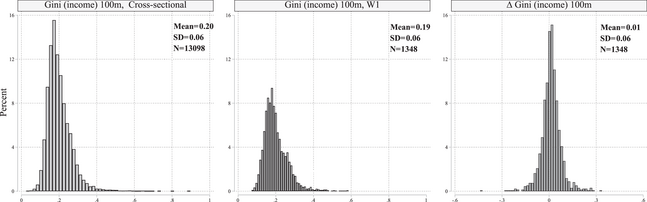

In short, previous research has uncovered a negative relationship between inequality and political system support, but auxiliary research has strongly questioned the premises of these analyses. This suggests that to provide a stronger test of the relationship between economic inequality and disaffection with the political system, one may study inequality at the local level, where it is palpable and therefore likely consequential. This is what this paper sets out to do by linking several large geo-referenced public opinion surveys to granular registry data in Denmark; a country with a relatively equal distribution of income (albeit not of wealth) at the national level – as we show in Appendix C.2 in the Supporting Information – but with a large variation in local-level inequality as illustrated in Figure 1. The variation is essential for rigorously testing the relationship between local inequality and political system support. The setup enables us to create a range of measures of income inequality in the immediate residential ‘micro-context’ – where inequality is experienced firsthand – and subsequently relate them to indicators of political system support.

Figure 1. Distribution of the Gini coefficient based on income for the cross-sectional sample (left panel), wave 1 of the panel sample (middle), and the change between wave 1 and 2 of the panel sample (right).

Note: Descriptive statistics based on the sample for the main models with trust in state institutions as the outcome. The left panel shows the distribution of the cross-sectional sample (cross-sectional); the middle panel shows the distribution of inequality in the first wave of the panel (W1) and the right panel presents the change between the two waves of the panel (

![]() $\Delta$).

$\Delta$).

In addition to the local focus, the paper also contributes by being the first to bring individual-level panel data to bear on the question of the connection between local economic inequality and measures of political system support. Supplementing cross-sectional (between-individual) analyses with longitudinal (within-individual) analyses significantly strengthens the potential for ruling out confounding by holding constant stable individual characteristics (e.g., personality or early-life socialisation). This parallels work on the effects of personal economic shocks on indicators of political system support and political engagement, which has increasingly turned to longitudinal individual-level data to strengthen causal identification (Jungkunz & Marx, Reference Jungkunz and Marx2022; Margalit, Reference Margalit2019).

To preview, we find no consistent evidence for a relationship between a range of measures of local economic inequality and various indicators of political system support (satisfaction with democracy, trust in state institutions and trust in politicians). This result challenges extant claims about the negative consequences of inequality for political system support.

Research design, data and measurement

We study the relationship between inequality and political system support in a combination of a longitudinal and a cross-sectional research design using data from Denmark. The crux of our approach is linking geo-referenced survey data, containing various indicators of political system support, with population-wide individual-level administrative data.

Specifically, we use data from a two-wave panel survey (the Social and Political Panel Study) in which the European Social Survey (rounds 1, 2 and 4) served as wave 1, with wave 2 collected in 2011/2. This amounts to between 863 and 1372 individuals in our primary panel data models. In addition, we utilise several cross-sectional surveys (collected between 1999 and 2017) that collectively provide for a large cross-sectional sample (between 11183 and 44395 depending on the specification). See Appendix A in the Supporting Information for more details about the survey data.

As dependent variables, we analyse three types of political system support (specifically, evaluations of regime performance, regime institutions, and political actors), building on Norris' (Reference Norris1999) typology, going from diffuse to more specific support. This enables us to assess whether inequality is related to support for the political system writ large, or only to more specific aspects. We use the following survey items as indicators of the three types of political system support (the exact wording varies slightly across surveys and it is presented in Table B.1 in the Supporting Information):

-

• Regime performance: Measured by a standard question of satisfaction with democracy asking ‘On the whole, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in Denmark?’.

-

• Regime institutions: Measured by three questions about trust in state institutions, asking ‘how much trust do you personally have in (i) the legal system, (ii) the police and (iii) parliament?’ (a composite measure calculated as an average of the three items).

-

• Political actors: Measured by a question about trust in politicians: ‘how much trust do you personally have in politicians?’.

Figure B.1 and Table B.3 in the Supporting Information present descriptive statistics for these outcomes, indicating relatively high levels of support for the political system in Denmark – also from a comparative cross-country perspective as shown in Appendix C.1 in the Supporting Information – while at the same time displaying substantial variation both between and within individuals over time.

The administrative registries contain extensive sociodemographic information as well as the geographical location of the place of residence for all individuals residing in Denmark. In combination, this enables us to construct measures of local inequality in individualised circle-shaped residential contexts of any given radius with the respondent in the centre. We calculated inequality measures for small ‘micro-contexts’: circles with a radius of 100, 250 and 1000 m. These are ideally suited for capturing everyday experiences with inequality – the focus of our study – in the residential context. By contrast, more aggregate contexts, including politico-administrative units sometimes used in work on contextual effects on political attitudes, are noisier measures of such everyday experiences because they cover larger areas and/or do not locate individuals within those areas (e.g., they could live on the edge of an administrative unit) (Bisgaard et al., Reference Bisgaard, Dinesen and Sønderskov2016; Dinesen & Sønderskov, Reference Dinesen and Sønderskov2015). We present results based on micro-contexts of three different sizes to probe the sensitivity of the results to the specific choice of context (i.e., to address the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (Wong, Reference Wong, Janelle, Warf and Hansen2004)). See Appendix B.3 in the Supporting Information for details about the contexts.

We take advantage of the richness of the registry data and measure inequality in several ways to provide for an exhaustive test of the hypothesis that local inequality is negatively associated with political system support. Inspired by the focus of the macro-contextual studies that are the backdrop of this study, we use the Gini coefficient of the local income distribution as the main measure of inequality. Figure 1 displays the variation in the Gini coefficient based on income, both cross-sectionally (left and middle panel) and longitudinally (right panel). The observations are relatively tightly clustered around the mean, but we still observe significant local variation in income inequality cross-sectionally and longitudinally. We supplement this measure with the Gini coefficient based on the local wealth distribution to examine the possibility that it is the wider distribution of economic resources that matters for political system support. We also explore the possibility that particularly visible signs of economic privilege are consequential by using the Gini coefficient based on the values of cars owned by residents in the context as an alternative measure of local economic inequality. Appendix B.4 in the Supporting Information provides further details and descriptive statistics regarding the inequality measures.

To explore the proposition that the relationship between local inequality and political system support varies by the personal economic situation (e.g., is negative for low-income individuals), we allow for heterogeneous effects across individuals' income relative to the national income distribution. Specifically, we distinguish between incomes in the 20th percentile and below, between the 20th and 80th percentile and above the 80th percentile (in the panel data, we use the individual's income position in the first wave).

In robustness analyses, we furthermore assess the possibility of delayed effects of changes in inequality and test whether local inequality is connected to political engagement, a possible implication and behavioural consequence of political system support. We also perform additional robustness analyses, which we describe below.

We analyse the relationship between local income inequality and support for the political system both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. The longitudinal analyses are based on individual-level panel data and include two-way (individual and wave) fixed effects, which implies that we analyse the relationship between within-individual changes in inequality and political system support while accounting for general changes in political system support. By focusing only on within-individual changes, we hold constant individual-level time-invariant factors that may likely confound the relationship between local inequality and political system support (e.g., personality traits or early-life socialisation that simultaneously influence the choice of place of residence as well as political system support). Compared to previous analyses based on cross-sectional data, the longitudinal analysis is a clear improvement vis-a-vis the ability to rule out confounding from stable individual and contextual characteristics. To minimise the risk of confounding from unobserved time-varying factors, we also include the following control variables, measured at the individual and contextual level, respectively: years of education, citizenship, employment status, marital status, cohabitation and time lived at the address (individual level), population density, unemployment share, ethnic heterogeneity, the concentration of single-parent households, median income, age variation and residential turnover (contextual level, all measured in the same contextual unit as inequality). In the cross-sectional analyses, we also include the following time-invariant control variables: sex, age and country of origin. All control variables are measured using data from the registries (see Appendix B in the Supporting Information for details about measurement). Standard errors are clustered on individuals in the panel analysis.

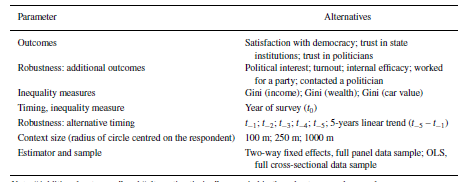

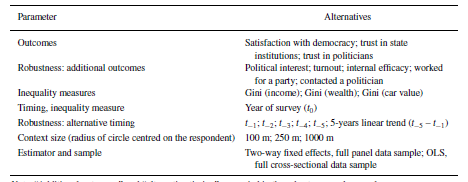

In sum, our data allow for a strong test of the relationship between local inequality and political system support. Table 1 summarises the various operationalisations and specifications used in the primary and robustness analyses.

Table 1. Parameters varied across models

Note: “Additional outcomes” and “alternative timing” are varied in the robustness analyses only.

Results

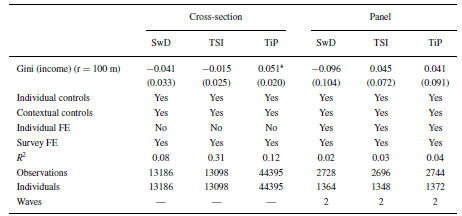

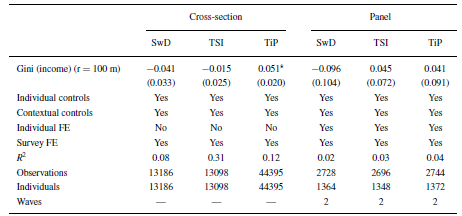

Does local economic inequality erode political system support? In the following, we report the results of a series of analyses to investigate this question. To give a feel for the results, we first report, in Table 2, analyses of the relationship between our three primary outcomes (satisfaction with democracy, trust in state institutions and trust in politicians) and income inequality (the Gini coefficient based on income measured in local residential contexts with a radius of 100 m) using panel data as well as cross-sectional data.

Table 2. The relationship between economic inequality (Gini) and political system support (satisfaction with democracy (SwD), trust in state institutions (TSI) and trust in politicians (TiP))

Note: The outcomes are rescaled to range from 0 to 1. Unstandardised regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses. See Table F.1 in Appendix F in the Supporting Information for the full results and Tables B.13 and B.10 in the Supporting Information for the list of covariates.

![]() $^{*}$

$^{*}$

![]() $p<0.05$; other p-values are above 0.20.

$p<0.05$; other p-values are above 0.20.

Counter to the expectation based on previous work in more aggregate contexts, the results reported in Table 2 suggest that there is no systematic negative relationship between income inequality, measured highly locally (within 100 m of the individual), and political system support. Three of the estimated relationships are negative and three are positive. The only statistically significant result – a positive connection with local income inequality – emerges for trust in politicians, which is based on the cross-sectional data and a much larger sample than the other outcomes.

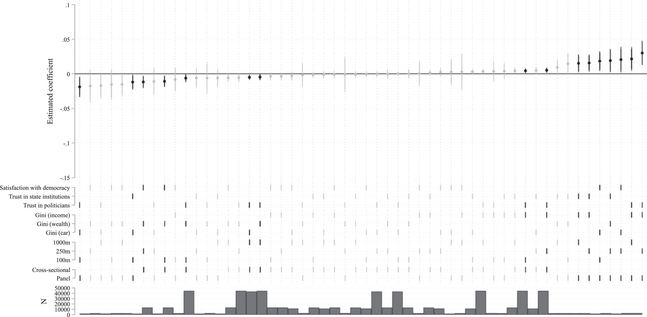

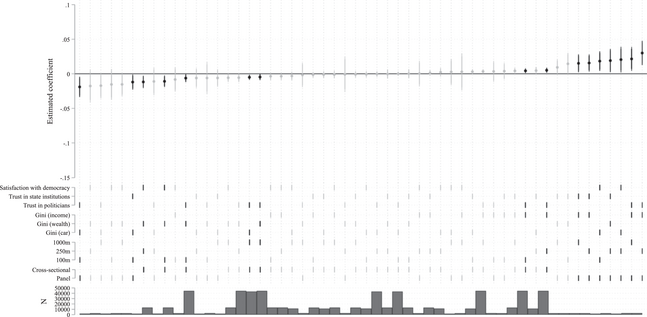

However, the inconsistent results could be an idiosyncratic reflection of the type of inequality studied or the chosen local context size. In the following, we report the results of analyses in which we systematically varied the parameters shown in Table 1. To present these efficiently and transparently, we report the coefficients and accompanying confidence intervals as well as the specifications of these models as multiverse plots in Figure 2 (54 main specifications) and in Appendix D (specifications for the analyses subset by income groups) and Appendix E (specifications for the robustness analyses) in the Supporting Information. The estimates are arranged from most negative to most positive in the upper part of the figure, where black dots signify statistically significant relationships. The middle part of the figure shows the specification of each model (indicated by vertical lines), while the bottom bar plot indicates the number of observations of each model. Hence, in addition to showing the distribution of coefficients, Figure 2 helps determine – by displaying variations in the coefficients resulting from the multiverse of different combinations of the noted features – whether a significant relationship (in either direction) is more likely to emerge for different outcome variables, inequality measures, context sizes and estimators/samples.

The primary finding standing out from Figure 2 is that the majority of the estimated relationships (38 out of 54) are statistically insignificant. Hence, contrary to expectations, there appears to be no negative effect of local economic inequality on political system support on average. Interestingly, 9 out of 16 statistically significant relationships are positive – of which 7 are based on the panel data, holding more causal leverage. There are thus indications that, if anything, local inequality is positively associated with political system support. One potential explanation for this pattern might be system justification – that is, the ‘process by which existing social arrangements are legitimised, even at the expense of personal and group interest’ (Jost & Banaji, Reference Jost and Banaji1994, p. 2; Trump, Reference Trump2018; Jost et al., Reference Jost, Banaji and Nosek2004). Yet, given the inconsistency of the overall pattern, we do not want to overstate the estimated significant positive relationships. The clear majority of insignificant coefficients – paired with potential issues of multiple testing – speak against this, and so does the fact that all estimated relationships are substantively weak. The average coefficient size is smaller than 0.001, that is, essentially zero, and the largest coefficient predicts that a one-standard-deviation change in local inequality corresponds to an increase in political system support by around 3 percentage points of the entire outcome range.

Figure 2. Multiverse presenting 54 models estimating the relationship between local inequality and political system support in different specifications.

Note: The outcomes are rescaled to range from 0 to 1; all measures of inequality are standardised to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 (based on the distribution of the entire sample). This implies that the coefficients display the predicted change in the dependent variable on a scale from 0 to 1 from a standard deviation change in the independent variable. Statistically significant (at the 5 per cent level) estimates are in black and statistically insignificant estimates are in light grey.

We further probed our findings in various ways, generally showing that they are fairly robust to alternative specifications. First, we used the three individual items composing the measure of trust in state institutions. The results, reported in Figure E.1 in the Supporting Information, are very similar to those reported above. Second, based on the idea that ultra-local areas might differ from the wider local areas (Adler & Ansell, Reference Adler and Ansell2020; Bisgaard et al., Reference Bisgaard, Dinesen and Sønderskov2016), we addressed the possibility that inequality in the neighbouring local area shapes political system support (see Appendix E.2 in the Supporting Information for details). The results reported in Figures E.2 and E.3 in the Supporting Information indicate that this is not the case. Third, we employed alternative time frames for our inequality measures to allow for delayed effects or effects based on longer-term trends in inequality. In Figures E.4 and E.5 in Appendix E.3 in the Supporting Information, we find results that are largely parallel to the contemporary inequality measure (although with a slight skew toward small, sometimes statistically significant, positive coefficients) when using lagged measures of inequality – up to 5 years before the survey interview – or the linear trend in inequality based on the 5 years preceding the interview year.

Following the previous literature on the topic, a logical follow-up question is whether this apparent absence of a relationship is in reality masking heterogeneity across income groups. Although previous research focusing on national-level inequality has indicated that the well-off become less supportive of the political system under higher inequality (Andersen, Reference Andersen2012; Krieckhaus et al., Reference Krieckhaus, Son, Bellinger and Wells2014), it seems at least equally theoretically plausible that the relatively better-off reward the political system with support for their privileged position (relatedly, Solt (Reference Solt2008) shows that inequality erodes participation of the rich relatively less than that of the poor). If the positive relationship for the more economically privileged overrides the negative one for the less well-off, this may explain the weak (and mostly insignificant) positive relationship observed in the analyses reported in Figure 2.

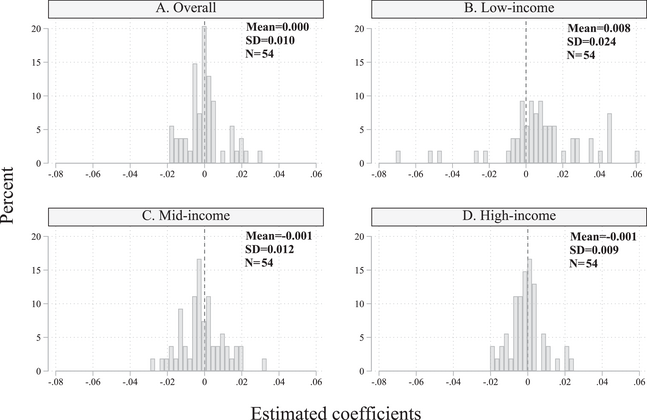

To test potential group-specific effects, we interacted local income inequality with the individual's income position in the national income distribution. Panels B, C and D in Figure 3 display the distribution of marginal coefficients estimated for individuals at the bottom, middle and top of the income distribution. For comparison, Panel A displays the distribution of the coefficients for the overall relationship (i.e., the coefficients already shown in Figure 2). A sub-group multiverse plot is reported in Appendix D.1 in the Supporting Information.

Figure 3. Coefficient distributions from the models estimating the relationship between political system support and inequality. Specifications for the average relationship in the overall sample (Panel A) and the relationship by income groups (Panels B–D).

Note: Low income: 20th percentile or below. Mid income: between the 20th and 80th percentile. High income: above the 80th percentile.

As Figure 3 reveals, there is little to indicate that inequality matters differently for people depending on their income. Generally, the estimated relationships are clustered around zero for all groups. The slight tendency for a more positive relationship for low-income individuals is not substantial. Based on this, we conclude that the relationship between local economic inequality and political system support does not vary markedly by personal economic situations, thereby ruling out the possibility that the null result is driven by countervailing effects by income groups.Footnote 2

Having found little evidence for a systematic relationship between local inequality and political system support, a natural follow-up question – emanating from the long-standing discussion about whether political trust stimulates or dampens political engagement (Levi & Stoker, Reference Levi and Stoker2000; Citrin & Stoker, Reference Citrin and Stoker2018) – is whether this absence of a relationship generalises to citizens' psychological and behavioural engagement with the political system. That is, do people become more or less politically engaged when living in more unequal local areas? Across several classical indicators of political engagement – political interest, voter turnout, internal political efficacy, having worked for a political party, and having contacted a politician – we find weak and mostly insignificant relationships between economic inequality and political engagement (see Figures E.6 and E.7 in Appendix E.4 in the Supporting Information).Footnote 3 Yet, among the statistically significant estimates (18 out of 90), all except for one are positive. Interestingly, this is primarily driven by the measure of having contacted politicians for which half of the estimated relationships (9 out of 18) are positive and statistically significant. Hence, while local inequality is essentially unconnected to support for the political system, there are some indications that it stimulates contacting the politicians that run the system, thereby potentially providing a channel for ameliorating inequality.

Discussion and conclusion

Does economic inequality undermine support for the political system in terms of satisfaction with democracy, trust in state institutions, and trust in politicians? In this paper, we argue that existing work, which has treated inequality as a national-level (or otherwise highly aggregate) phenomenon, has not been optimally equipped to answer this question. People are largely ignorant about national-level inequality, which likely reflects that it does not necessarily correspond with their everyday experiences. To test the inequality-political system support link more theoretically appropriately and methodologically rigorously, we have examined how palpable local experiences of inequality are related to political system support using geo-referenced panel and cross-sectional survey data linked with registry data in Denmark. Across different outcome measures, operationalisations of inequality, income groups, sizes of the local context and model specifications, we find no consistent relationship between local economic inequality and political system support. Our findings thus seriously challenge the notion that economic inequality erodes support for the political regime and the institutions that operate within it.

Why do we observe different results than previous studies of inequality measured at the national or more aggregate regional levels? At least two potential explanations come to mind. First and most mundane, perhaps it is just the case that national-level economic inequality is more important than inequality measured more locally as authors from neighbouring literature have argued (Wilkinson & Pickett, Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2010). This is hard to rule out, but – importantly – it is equally hard, if not harder, to rule in. In essence, analyses focusing on relatively few countries are vulnerable to various forms of confounding that make it very hard to convincingly establish a causal relationship between inequality and political system support. Perhaps most obviously, national-level inequality may be a proxy for national culture, institutions and general socioeconomic development. Even if all of these potential confounders are measured and included in the analyses, the limited number of countries makes it hard to distinguish them empirically from inequality and therefore, by implication, questions the validity of such analyses. By contrast, focusing on local-level variation within one country holds constant features of national culture and institutions and offers many more units, plus – in our case – the ability to measure plausible confounders through the administrative registries. As such, we believe that our analysis has credibly established the absence of a relationship between local inequality and political system support, while the aggregate-level analyses of inequality are, at best, inconclusive on this relationship.

Second, could the absence of a relationship between local economic inequality and political system support simply be a feature of the Danish context; for example, the combination of relatively low national-level income inequality, relatively high levels of wealth inequality and the comparatively high level of political system support (see Appendix C.1 in the Supporting Information)? As argued earlier, the pronounced local variation in inequality in Denmark makes for a strong test of the role of inequality, thus speaking against this alternative explanation ceteris paribus. However, it could be the case that the national context of, comparatively speaking, affluence and high income equality, dampens the relationship. To answer this question, future work would ideally incorporate local data from multiple contexts to better grasp the potential moderating influence of the national context.

Although we think that we have provided a strong test of the role of inequality in shaping political system support, our work has its limitations and there are various ways in which future work could expand on it. For example, parallel to most other studies we have focused exclusively on the residential context, and while this is arguably a meaningful starting point given that most people have a residence and spend considerable time there, there are non-residential contexts – for example, around places of work or study, along commuter routes, or near sites for grocery shopping – in which people may also experience inequality directly. By examining a larger range of contexts, possibly employing creative designs to track people's whereabouts (Moore & Reeves, Reference Moore and Reeves2020), future work could provide a fuller understanding of the role of everyday exposure to economic inequality on political system support. Furthermore, while we have employed panel data, which bypass some of the concerns associated with cross-sectional data in related existing work, to document the absence of a relationship between local inequality and political system support, future work would ideally employ well-powered field or natural experiments to strengthen causal identification and rule out a causal effect with even greater certainty.

Finally, our results should not be taken as an excuse for governments to refrain from pursuing policies that create a more equal distribution of resources in society. The literature on economic inequality abounds with results pointing to normatively troubling consequences of inequality in other domains than political system support (for an influential analysis, see Wilkinson & Pickett, Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2010). Although a great deal of these findings may suffer from some of the same methodological problems that we have identified in the literature on political system support, it would be inadvisable to ignore the potential dangers of economic inequality without investigating this empirically at great length. That said, the results of this study, in combination with studies of other determinants of political system support (e.g., Rothstein, Reference Rothstein and Levi‐Faur2012), suggest that combating corruption, prioritising equal treatment of citizens and an effective bureaucracy – in short, good governance – may be a more effective way of generating citizens' support than tackling economic inequality (e.g., Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Schneider and Halla2009; Chong et al., Reference Chong, De La O, Karlan and Wantchekon2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank participants and the discussant, Rasmus Tue Pedersen, at the panel ‘The effects of inequality on political trust’ at EPSA 2023 as well as the reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding statement

The study was funded by the Rockwool Foundation (grant number: 3026) and Spar Nord Foundation (Grant Number: 62636). Kim Mannemar Sønderskov was funded by the Danish National Research Foundation (Grant Number: DNRF144).

Data availability statement

The analyses are partly based on Danish administrative individual-level registry data. Although anonymised, the data are not publicly available by Danish law. The combined survey and registry data are stored at Statistics Denmark and can only be accessed by researchers affiliated with a Danish research institution. However, the authors have made available the script and output used to generate the main results included in the article. This replication material can be found on the Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PIJJQ0.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Δ

Δ