Introduction

The public opinion of men and women differ on a broad variety of topics including redistribution, child care, or environmental protection (Shapiro & Mahajan Reference Shapiro and Mahajan1986; Howell & Day Reference Howell and Day2000; Schlesinger & Heldman Reference Schlesinger and Heldman2001; Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Cassese, Lizotte, Wolbrecht, Beckwith and Baldez2008). Scholarly work that aims to reveal whether this gender gap in policy preferences is appropriately represented in the political decision‐making process mostly focuses on sex differences in the parliamentary activities of legislators (see, e.g., Tremblay Reference Tremblay1998; Thomas & Welch Reference Thomas, Welch and Carroll2001; Childs & Withey Reference Childs and Withey2004; Celis Reference Celis2006; Barnes Reference Barnes2012; Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Debus and Müller2015; Lloren & Rosset Reference Lloren and Rosset2017). However, not all politicians are equally well‐equipped to change policy outcomes, but some function as ‘critical actors’ (Childs & Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009) or ‘equality champions’ (Chaney Reference Chaney2006), ‘who initiate policy proposals on their own and/or embolden others to take steps to promote policies for women’ (Childs & Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009: 138). As pivotal actors shape party positions (Harmel & Janda Reference Harmel and Janda1994), party leaders have an outstanding role of this sort, in particular, if activists’ factions are weak (Schumacher et al. Reference Schumacher, Vries and Vis2013) and if they are directly elected (Ceron Reference Ceron2019). Despite of the increasing number of women serving as party heads, the relationship between the sex of party leaders and their organisations’ positions has received comparably little scholarly attention. Notably, higher shares of women in party executive committees seem to enhance support for gender quotas; while stances concerning the expansion of redistribution and education are independent of the sex of the party leadership (Greene & O'Brien Reference Greene and O'Brien2016; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2011). Yet, the literature provides neither clear expectations nor empirical evidence of how women serving as party leaders might change party positions concerning the new dimension of political conflict, even though the content of political competition has shifted from “a simple alternative between socialist (left) and capitalist (right) politics to a more complex configuration opposing left‐libertarian and right‐authoritarian alternatives” (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994: 30–31). This study addresses this research gap by providing a comprehensive answer to the following question: In which manner do women party leaders change their organisation's agenda?

The article reveals that parties increasingly support green, alternative and libertarian positions if they are led by a woman, while stances concerning redistributive questions do not change in a systematic manner. I argue that these effects follow from dissimilar gender gaps in political preferences at the elite level. The support of female citizens for higher levels of redistribution emerges from their more pronounced economic vulnerability, but women politicians often come from more privileged backgrounds and are less affected by problems such as the gender gap in income, poverty among senior citizens, or the financial risk associated with divorce (Reingold Reference Reingold2000; Lloren & Rosset Reference Lloren and Rosset2017). For this reason, women as party leaders are less likely to transform party positions on the economic dimension of political competition. By contrast, gendered preferences on sociocultural questions, which include issues such as multiculturalism, immigration, environmental protection and women's rights, tend to stem from gendered patterns of socialisation and also occur for the most privileged women.

To provide empirical evidence for this argument, I study 304 manifestos of 102 parties in 19 developed democracies between 1995 and 2018. Data from the MARPOR project (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019) allow capturing shifting stances on the economic and sociocultural dimensions of political conflict. The analyses reveal that the impact of the sex of the party leader on their organisations’ positions concerning sociocultural debates is not limited to green or left‐wing parties. Neither is the observed pattern driven by a one‐time effect that occurs solely with the first woman leading a party. Moreover, I show that the observed pattern is not dependent on issues of particular concern to women, such as support or rejection of abortion or the protection of demographic groups (including those characterised by gender), which are part of the sociocultural dimension of political conflict. Instead, parties emphasise anti‐growth, environmental protection and the protection of freedom and human rights, if they are led by a woman.

These insights enhance the understanding of the ‘Politics of Presence’ argument (Phillips Reference Phillips1995) – the rationale that women in politics promote the interests of female citizens. Shared life experiences are supposed to enable women politicians to better understand the interests of their peers, to formulate justified beliefs about what women want if new issues emerge and to act as credible and effective advocates (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999). The findings presented here add two important clarifications to this argument: On the one hand, the set of issues for which this pattern holds is limited to those on which women in the citizenry and in politics actually share life experiences and, at least for the case of party leaders, it does not comprise economic concerns. On the other hand, policy areas in which women act for women go far beyond women's issues, covering a broad variety of sociocultural questions. Overall, this complements our understanding of the conditions under which women serving as critical actors can contribute to the enhanced representation of female citizens.

Literature review: The gender gap in policy preferences at the mass and elite levels

The expectation that women as party leaders change party positions is grounded in the literature revealing a gender gap in public opinion. Previous scholarly work revealed that, first, female citizens are more likely to display distinct policy preferences on issues of particular concern for their gender, that is, so called ‘women's issues’. These include demands for stricter sexual harassment laws, more liberal abortion rights, or generous parental leave and child care options (Lizotte Reference Lizotte2015; Clark Reference Clark2017). Beyond women‐specific issues, female citizens tend to favour higher levels of redistributive policies than men (Gidengil et al. Reference Gidengil, Blais, Nadeau, Tremblay and Trimble2003; Iversen & Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006; Abendschön & Steinmetz Reference Abendschön and Steinmetz2014; Jaime‐Castillo et al. Reference Jaime‐Castillo, Fernández, Valiente and Mayrl2016). Moreover, women are more likely than men to favour green, alternative and libertarian policies over traditional, authoritarian and nationalist ones. In contrast to men, women appear to be more concerned with the environment (McCright & Xiao Reference McCright and Xiao2014), are more likely to support calls for sustainable development (De Silva & Pownall Reference De Silva and Pownall2014) and display a higher willingness to pay to reduce the risks connected to global warming (Joireman & Liu Reference Joireman and Liu2014). Female citizens are also more supportive of anti‐discrimination and equal treatment policies for same sex couples (Herek Reference Herek2002), display a higher probability to oppose the use of force in international conflicts (Togeby Reference Togeby1994) and condemn police violence (Halim & Stiles Reference Halim and Stiles2001). These patterns persist even though most of these studies take party identification or sociodemographic characteristics into account, which indicates that conservative women differ from conservative men just like liberal women differ from liberal men.

Previous research traced the origin of these sex differences in citizens’ political preferences to three factors (Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Cassese, Lizotte, Wolbrecht, Beckwith and Baldez2008): First, distinct patterns of socialisation of men and women might lead to diverging attitudes and basic values, with women showing higher levels of altruism and empathy as well as stronger support for egalitarianism and government activism (Gilligan Reference Gilligan1982; Jaffee & Hyde Reference Jaffee and Hyde2000). Beyond simply forming women's preferences, gendered identities might emerge that are linked to different values (e.g., communal outlook) and expectations about government activity, for instance, concerning child care (Feather Reference Feather1984). Second, a feminist consciousness might motivate (some) women to hold distinct beliefs about women's and men's role in society, resulting in the development of strong support for egalitarianism and increased spending on social programs, sympathy towards the disadvantaged and lower levels of traditional morality (Conover Reference Conover1988; Hayes et al. Reference Hayes, McAllister and Studlar2000). Finally, sex differences in life circumstances cause diverging policy preferences between men and women, with women's higher economic vulnerability and larger expected gains from redistribution leading to higher levels of support for such policies (Box‐Steffensmeier et al. Reference Box‐Steffensmeier, De Boef and Lin2004; Carroll Reference Carroll, Carroll and Fox2006).

The ‘Politics of Presence’ argument (Phillips Reference Phillips1995) suggests that women politicians take up the preferences of the female part of the electorate when exercising their political role. Shared life experiences should enable women in politics to understand and approximate women's preferences successfully (Phillips Reference Phillips1995; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999). An extensive set of literature provides support for the distinct policy orientations of men and women running for and elected to legislative positions. Most notably, members of parliament hold gendered positions on ‘women's issues’, that is, topics that disproportionality affect female citizens. During their electoral campaigns, women candidates tend to emphasise social issues (La Cour Dabelko & Herrnson Reference La Cour Dabelko and Herrnson1997; Lloren & Rosset Reference Lloren and Rosset2017). Once elected, they promote these topics, for instance, through written and oral requests (Höhmann Reference Höhmann2020; Childs & Withey Reference Childs and Withey2004), bill sponsorship (Thomas & Welch Reference Thomas, Welch and Carroll2001) and co‐sponsorship (Barnes Reference Barnes2012) or speeches (Tremblay Reference Tremblay1998; Celis Reference Celis2006; Baumann et al. Reference Baumann, Debus and Müller2015). However, women running for and elected to legislative offices seem to be just as inclined as men to support legislation leading to an extension of the welfare state (Erickson Reference Erickson1997; Norris & Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski2004; MacDonald & O'Brien Reference MacDonald and O'Brien2011; Lloren & Rosset Reference Lloren and Rosset2017).

This study is interested in the role of party leaders, that is, the single (or in some cases dual) head of a party. This set of actors has the power to influence the substantial orientation of their organisations and initiate change in party structures (Harmel & Janda Reference Harmel and Janda1994). Previous research identified them as ‘critical actors’ (Childs & Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009) or ‘equality champions’ (Chaney Reference Chaney2006) that are better equipped to change party positions than any other political actor. Due to the presidentialisation of parties, they increasingly receive public attention (Webb & Poguntke Reference Webb and Poguntke2005) and who leads a party is becoming more decisive for vote choices (Bittner Reference Bittner2011). Notably, the internal organisation of the party, such as the power of activist factions or the selection mechanisms for the party leadership, moderates the power of party leaders to set the agenda (Schumacher et al. Reference Schumacher, Vries and Vis2013; Ceron Reference Ceron2019). Even though party leaders cannot set the agenda unilaterally (Meyer Reference Meyer2013; Fagerholm Reference Fagerholm2016), they might use inclusive decision‐making procedures strategically to increase the legitimacy of their suggested policies (Scarrow et al. Reference Scarrow, Webb, Farrell, Dalton and Wattenberg2000).

To date, two studies address the role of the sex of the party leader for party positions.Footnote 1 Kittilson (Reference Kittilson2011) investigates the impact of women in party executive committees in 24 post‐industrial democracies between 1990 and 2003, taking 142 parties into account. She finds that higher shares of women in party executive committees lead to a stronger emphasis of social justice in party programs (i.e., need for fair treatment of all people and the end of sex‐based discrimination) as well as to the introduction of party‐level gender quotas, but not to positional revisions concerning welfare policies such as health services, social housing, or education. Using more recent data, Greene and O'Brien (Reference Greene and O'Brien2016) study 20 democracies between 1952 and 2011 with a total of 110 parties. While interested in the effect of the share of women MPs on party positions, they also take the sex of the party leaders into account. The empirical evidence reveals that issue diversity increases if a party is led by a woman, but the left–right positioning remains unaffected (for similar evidence, see also O'Brien Reference O'Brien2019). Given that parties’ general left–right placement tends to be closely related to their economic position (Bakker & Hobolt Reference Bakker, Hobolt, Evans and De Graaf2013), this insight supports Kittilson's (Reference Kittilson2011) initial finding that women party leaders do not lead to a repositioning of parties on this dimension of politics. To my best knowledge, how the sex of the party leader shapes party positions concerning green, alternative and libertarian issues has not, as yet, received any scholarly attention.

Theoretical expectations: How women party leaders impact party positions

I argue that how party positions on a given dimension of political competition change as a consequence of the sex of the party leader depends on the degree to which women in politics share the same preference‐forming life experiences as women in the citizenry. Just like male politicians (see, e.g., Blondel & Thiébault Reference Blondel and Thiébault1991; Blondel & Müller‐Rommel Reference Blondel, Müller‐Rommel, Dalton and Klingemann2007), women who are active in politics tend to have exceptional social backgrounds, characterised by high levels of income and education (Schwindt‐Bayer Reference Schwindt‐Bayer2011). While these different realities are inconsequential for women's preferences concerning sociocultural issues, they translate into dissimilar gender gaps at the mass and elite level concerning positions on economic questions.

The first hypothesis states that parties led by a woman as opposed to a man emphasise green, alternative and libertarian issues. Two rationales justify the expectation: First, this ideological dimension includes traditional women's issues such as anti‐discrimination policies or abortion rights. These are issues that are of particular concern to all women independent of their social status. Second, new topics such as environmental protection and an anti‐growth economy but also support for human rights, migration, or same‐sex marriage are part of this dimension of political competition. Preferences concerning these topics likely result from political attitudes. Higher levels of empathy and altruism lead to larger support for the equal treatment of all societal groups, including demands for inter‐ and intra‐generational justice. These political attitudes develop as a consequence of socialisation, which differs between men and women (Gilligan Reference Gilligan1982; Jaffee & Hyde Reference Jaffee and Hyde2000), but not necessarily by social status. Despite differences in the economic context, women in politics and the population should develop similar political attitudes in this regard.

-

H1: If a party is led by a woman, the party position on the sociocultural dimension of political conflict moves towards a larger emphasis of green, alternative and libertarian issues.

For party positions concerning debates about redistribution, that is, the economic dimension of political conflict, I expect a null effect of the sex of the party leader. Women in the elite often fail to share the economic life experiences of the majority of women (Erickson Reference Erickson1997; Norris & Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski2004; MacDonald & O'Brien Reference MacDonald and O'Brien2011; Lloren & Rosset Reference Lloren and Rosset2017). If anything, those who become party leaders are even more exceptional than those running for and elected to parliaments – the context of most previous studies. In consequence, women party leaders lack both the self‐interest and the shared experience that might motivate them to shift their party's position towards larger support for redistribution.

-

H2: If a party is led by a woman, the party position on the economic dimension of political conflict does not change in a systematic manner.

Research design and data

To test these hypotheses, this article analyses changes in party manifestos for 102 parties in 19 developed democracies between 1995 and 2018 (for a complete list of countries, parties and manifestos, see Appendix 1 in the Supporting Information).Footnote 2,Footnote 3 The country selection enhances external validity by including a broad variety of countries. The regional variation ranges from Central and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Latvia) to Western Europe (Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Ireland), from Scandinavia (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway) to Southern Europe (Portugal, Spain, Greece) and several countries in other world regions (Australia, Canada, Israel, New Zealand, USA). The sample covers not only parliamentary democracies, but also a presidential and a semi‐presidential system. With Switzerland, the dataset also includes a political system characterised by strong direct democratic elements. While, in particular, the Nordic countries are front‐runners in terms of gender equality, other cases in the sample perform rather poorly in this regard. Despite these differences, parties in all countries have been led by women.

Dependent variables: Party positions on two dimensions of political competition

I make use of data from the MARPOR project (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019) to measure change in party positions on the economic and sociocultural dimensions of political conflict.Footnote 4 The dataset identifies the share of quasi‐sentences in a manifesto dedicated to a certain category of substantial statements. Overall, it covers 56 categories including policy domains as diverse as external relations, freedom and democracy, political systems, economy, welfare and quality of life, fabric of society and social groups.

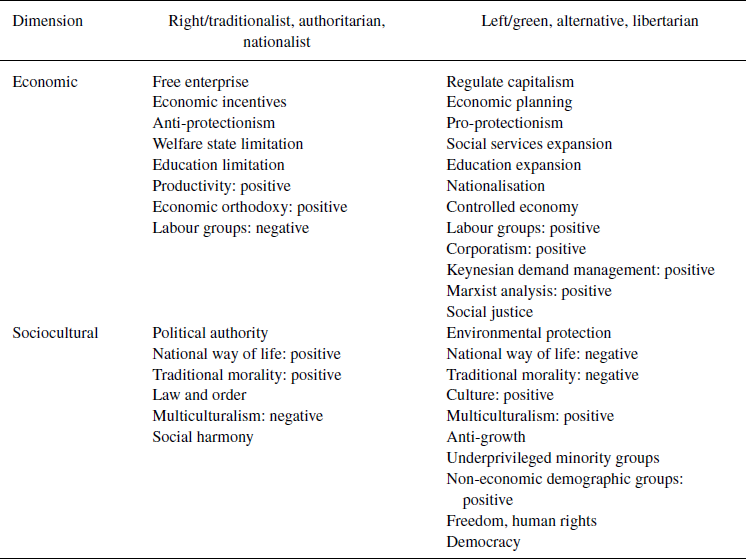

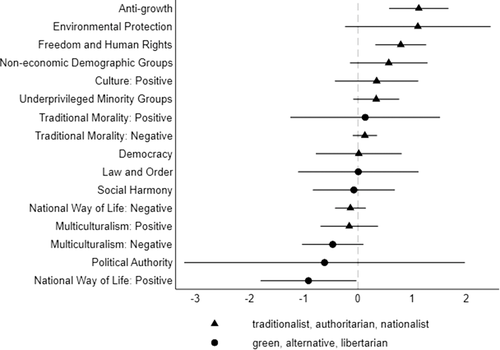

Table 1 presents a list of topics assigned to the right and left emphases of the economic dimension and the traditionalist, authoritarian, nationalist and green, alternative, libertarian emphases of the sociocultural dimension (for descriptions of each item and variable names, see Appendix 2 in the Supporting Information).To construct indices for the economic and socio‐cultural dimensions from these items, I, first, use factor analysis following suggestions by Bakker and Hobolt (Reference Bakker, Hobolt, Evans and De Graaf2013) to identify items belonging to the two dimensions for each country.Footnote 5 Afterwards, the items were merged into two indices following the recommendations by Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011). The resulting measures are logit scaled, meaning that shares of quasi‐sentences referencing a policy domain are weighted depending on the overall number of phrases. Smaller values of this measure indicate a stronger orientation towards the left on the economic dimension or, respectively, towards green, alternative and libertarian positions on the sociocultural dimension of political conflict. The analyses will investigate first differences, that is, increase and decrease of the indices from t ‐1 to t 0.

Table 1. MARPOR main categories and their assignment to the ideological dimensions of political competition

The observed modifications of party positions on the sociocultural dimension range between −5.99 and 6.95, with a standard deviation of 1.30 and a mean of 0.003. For the economic dimension, the observed first differences range between −4.05 and 4.20, with a standard deviation of 0.97 and a mean of −0.04. Parties, hence, do revise their positions on both dimensions of political conflict considerably from one election to the next. However, the strength and direction of these shifts vary. Single‐sample t‐tests, assessing whether the average movement of parties on each dimension from one election to the next equals 0, uncover underlying time trends towards any pole of the ideological spectrum. The results support the null‐hypothesis that revisions in party positions do not lean towards any direction (with p = 0.48 for the sociocultural dimension and p = 0.81 for the economic dimension).

Independent variable: Women as party leaders

As the main independent variable, I make use of original data for the sex of the person who led the party at the time the manifesto was developed. For the most part, this is the individual who also ran the electoral campaign of the subsequent election. However, in a few instances, leadership changes in the critical phase of the electoral race. For such cases, I take the sex of the person leading the party at the moment of the election for two reasons: First, this politician decides on the final revisions of the manifesto and, assuming that leadership change during a campaign is also supposed to communicate substantial adjustments to voters, these revisions shortly before an election are substantially influential. Second, someone who replaces a running party leader during a campaign was probably also involved in drafting early versions of the manifesto, meaning this person was already in the inner circle of power. I made use of official party websites, media reports and other Internet sources to identify the sex of the party leader. Within the dataset, 20.71 per cent of all observations or, respectively, 99 of 478 manifestos are developed by parties led by a woman. Of all 102 parties, 45 did experience a campaign led by a woman in the time horizon under study.

Control variables

As controls, the models include two sets of variables that might impact both, the sex of the party leader and changes of party positions.Footnote 6

A first set of variables follows from the literature on women in politics and how they impact party positions. To begin with, the share of women in party parliamentary groups is a decisive confounder. Party members who are elected to parliament have considerable agenda setting power and the increasing presence of women legislators should enhance responsiveness to women in the citizenry (see Greene & O'Brien Reference Greene and O'Brien2016 for the economic left–right dimension). Additionally, higher shares of women in parties’ parliamentary groups increase the pool of qualified women for a leadership position (O'Brien Reference O'Brien2015). I gathered data on the presence of women from the political data yearbook (European Consortium of Political Research 1992–2018) for more recent elections, and for earlier ones from parliamentary websites, statistical offices and electoral commissions. Second, previous research indicates that the presence of a gender quota itself impacts the acceptance for women's interests in a party (Weeks Reference Weeks2019). Logically, this variable also impacts the chances of women to move to the highest party office. I use a binary variable that takes the value 1 if a country had a legislated quota in a given year and 0 if not (data from Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Wilson, Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Ilchenko, Krusell, Maxwell, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Pernes, Römer, Stepanova, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2019).Footnote 7 Third, I include two variables that capture party ideology and party family, since certain types of parties are more likely to include higher proportions of women and are also more open to their policy demands (Caul Reference Caul1999; Kittilson & Tate Reference Kittilson and Tate2004). A first binary variable captures whether a party is a left‐wing party (1) or not (0) (based on the left–right measure by Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019). A second dummy variable takes the value 1 for green parties and 0 for all other party families (based on the party family identified by Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019). Finally, I consider women's role in the party leadership based on two dummy variables that identify (1) whether a woman is the first to lead a party and (2) whether the last electoral campaign was developed under a man. Both scenarios would lead to a one‐time effect, in which a woman as party leader goes hand in hand with a window of opportunity, in which change occurs even to a stronger degree. The variables are based on my own coding of diverse web sources.

The second set of control variables follows from the literature on political parties. Decreasing polling results might motivate parties to revise their party manifestos to increase their attractiveness to voters in upcoming elections (Harmel & Janda Reference Harmel and Janda1994). At the same time, internal crises increase the chances of outsiders such as women to be selected for top executive positions (Ryan & Haslam Reference Ryan and Haslam2005; O'Brien Reference O'Brien2015). Given that comparing pooling data for a large number of parties across time and countries is difficult, I approximate this concept with the actual losses between the last and current election (vote share t ‐1 – t 0, based on Volkens et al. (Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Matthieß, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019). Additionally, the emergence of new contenders or a changing power balance in the party system might motivate parties to adapt their party positions and personnel choices. To capture such a process, I include change in the effective number of parliamentary parties (based on ParlGov, Döring & Manow Reference Döring and Manow2019). A final important confounding variable is the party‐specific context. Intra‐party democracy and the party's electoral context shape both, the chances of different candidates such as women to ascend to high‐profile party offices and the impact that party leaders can unfold on party positions. Notably, who stands the best chances to lead a party depends on the level of intra‐party democracy (Kenig Reference Kenig2009; Ceron Reference Ceron2012) and the divergence between party leaders and the party selectorate (Greene & Haber Reference Greene and Haber2016). Moreover, intra‐party organisation such as the dominance of activists’ factions limit party leaders’ scope to shift party positions as intended (Schumacher et al. Reference Schumacher, Vries and Vis2013; Schumacher Reference Schumacher2015, see also Ceron & Greene Reference Ceron and Greene2019; Ceron Reference Ceron2019). To take this diversity of factors into account, all models include party fixed effects.Footnote 8

Empirical evidence: Women party leaders and changing party positions

The subsequent section studies the relationship between the sex of party leaders and the repositioning of parties on the two ideological dimensions of political conflict. After presenting some bivariate evidence, I describe the results of the regression models and multiple robustness tests. At the end of the section, I investigate the effect of women as party leaders on the items composing the index for party positions on the sociocultural dimension of political conflict in detail.

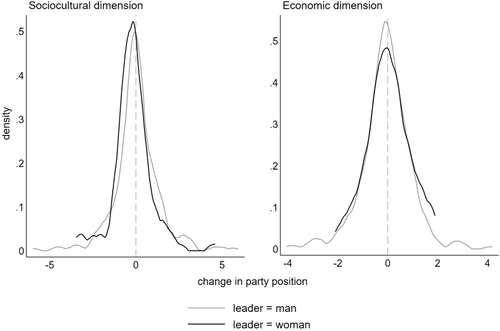

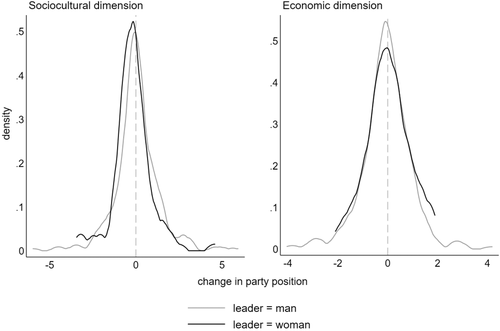

Figure 1 shows kernel density functions for change of indices capturing party positions on the sociocultural and economic dimensions of political conflict (from t ‐1 to t 0). Parties with men and women leading (at t 0) are displayed separately. The figure on the left shows the distribution of movements in party positions on sociocultural questions. For parties led by a man, the distribution peaks around 0, indicating that in most cases, these organisations do not revise their stances concerning new political issues. By contrast, if a party is led by a woman, the curve showing the distribution of changes in party position on the sociocultural dimension of political conflict is further to the left. Parties, thus, shift more frequently under women's leadership and the new position is often greener, more alternative and libertarian than before. Turning to the figure on the right‐hand side, which shows the distribution of changes in party positions concerning economic questions, the curves indicates a broader distribution of values, that is, that parties are more inclined to reposition themselves on these issues. For parties led by a man, the curve peaks around a slightly negative value, indicating that many of these organisations become more supportive of redistributive policies. The observed values for the dependent variable for parties led by a woman is symmetrically distributed around 0, lacking a clear trend towards more support for leftist economic policies.

Figure 1. Kernel density function of changes in the indices measuring party positions on the sociocultural and economic dimensions of political competition (t −1 to t 0) by sex of party leader (at t 0).

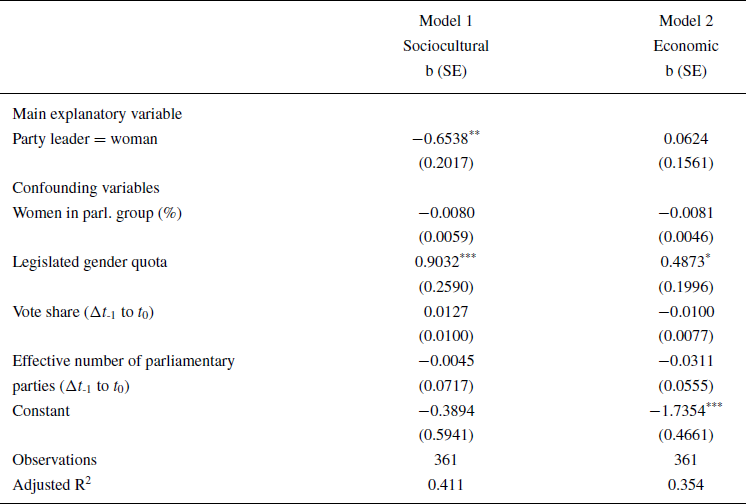

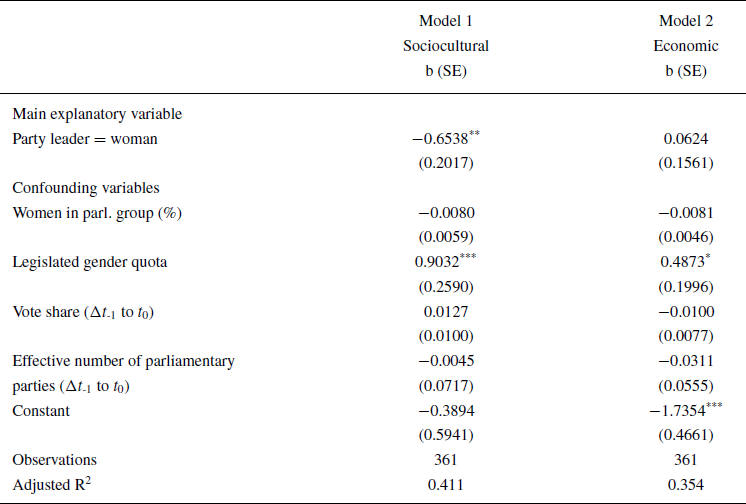

To further investigate this pattern, I estimate error correction models predicting change in the indices for party positions on the sociocultural (Model 1 in Table 2) and economic (Model 2 in Table 2) dimensions of political conflict from t ‐1 to t 0. All models take autocorrelation between party positions over time into account by including a lagged dependent variable (t ‐1). While the main models presented in Table 2 follow from linear regression with uncorrelated standard errors (i.e., based on the assumption of independent observations), Appendix 3 in the Supporting Information contains the results for models with jackknife standard errors and Appendix 4 in the Supporting Information for multilevel models with manifestos nested in parties nested in countries. In the more complex models, the effects of the key variables are substantially the same as described in the main text.

Overall, the models presented in Table 2 support the expectation that women leaders are more decisive for party positions on the sociocultural than economic dimension of political debates. Parties’ positions on the sociocultural dimension decrease −0.65 points from one election to the next, if a party is led by a woman as opposed to a man (with p = 0.001 based on Model 1.1 in Table 2). Substantially, this means that the prominence of green, alternative and libertarian ideas increases, but traditionalist, authoritarian and nationalist ideas decreases, if the party leader guiding the development of the new manifesto is a woman. This confirms H1 which posited that parties become more libertarian under women leaders. The index capturing parties’ positions on the economic dimension of political conflict, in turn, does not increase or decrease in a systematic manner depending on the sex of the party leader. The coefficient of the dummy variable for the sex of the party leaders is close to 0 (0.06 with p = 0.69 based on Model 1.2 in Table 2). This pattern is consistent with the expectation formulated in H2, namely that women's presence as party leaders is indecisive for party positions on classic redistributive debates.

Turning to effects of the control variables, the results presented in Table 2 suggest that women's numerical strength in parties’ parliamentary groups influences party positions on economic concerns. Larger numbers of women in parliament (at t 0) appear with increasing proportions of phrases supporting redistribution, corporatism and protection of national markets in manifestos (with p = 0.077) For the sociocultural dimension of political conflict, the effect of women's numerical strength in parties does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (with p = 0.173).Footnote 9,Footnote 10 This is consistent with the finding of earlier studies that higher shares of women in parliamentary groups would move parties to the left on the traditional left–right scale capturing party ideology (Greene & O'Brien Reference Greene and O'Brien2016; O'Brien Reference O'Brien2019).

Table 2. Linear regression models of the indices measuring party positions on the sociocultural and economic dimensions of political competition (t ‐1 to t 0)

Note: Models include a lagged dependent variable and party fixed effects.

***p < 0.001.

**p < 0.01.

*p < 0.05.

If a statutory quota exists, party manifestos tend to indicate larger support for traditionalist, authoritarian and nationalist ideas as well as for market freedom. This contradicts my original expectation deduced from Weeks (Reference Weeks2019) that parties are more inclusive of women's interests under gender quotas. Possibly, legally binding affirmative actions might reinforce negative stereotypes about women in politics as less experienced and dependent (Franceschet & Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008). The mere existence of statutory quotas decreases the chances of women to survive as party leaders (O'Brien & Rickne Reference O'Brien and Rickne2016) and of women legislators to get their policies enacted (Franceschet & Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008). In parallel, parties also appear to be less likely to revise their sociocultural positions if gender quotas are in place.

Neither changes in the party system nor expected electoral losses influence the repositioning of political parties on either of the two ideological dimensions. This fact clarifies that we still know little about the main drivers for change in party manifestos (Greene & O'Brien Reference Greene and O'Brien2016).

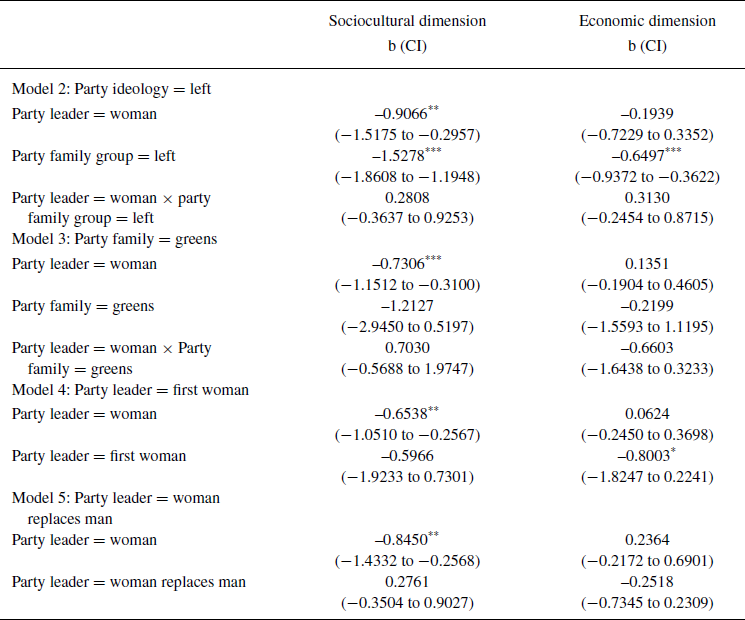

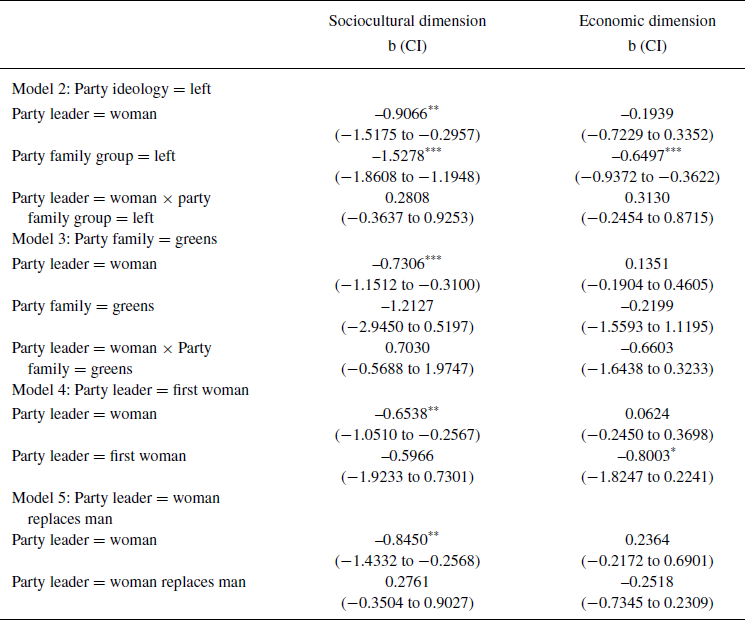

To further stress the robustness of the effect of party leader's sex on the repositioning of their party along the ideological axes, Table 3 presents key coefficients and their confidence intervals from a series of additional models (full models are presented in Appendix 7 in the Supporting Information). First, one might argue that party ideology functions as an enabling factor, so that in certain parties only women party leaders are able to change their organisations substantially. Left‐wing parties in general, and green parties in particular, are traditionally the main platforms for the representation of interests of excluded groups such as women and minorities and are more open to women's political participation (Caul Reference Caul1999; Kittilson & Tate Reference Kittilson and Tate2004). To take this rationale into account, I modified the main model and added interaction terms for the sex of the party leader and a dummy variable for left‐wing (Model 2) and green (Model 3) parties. The effects of the sex of the party leader on movement in party positions on the sociocultural and economic dimensions of political competition do not change if party ideology and family are taken into account. Furthermore, neither of the interaction terms is statistically significantly different from 0. There is, hence, no indication that the effect of sex of the party leader on their organisation's sociocultural position and the null effect on the economic position observed in the main models is solely driven by parties with certain ideological positions or belonging to specific party families.

Table 3. Coefficients of key variables on indices measuring party positions on the sociocultural and economic dimensions of political competition (t ‐1 to t 0) with 95% confidence intervals

Moreover, it might be that the increasing support for libertarian positions by parties led by a woman observed in the main model captures solely a one‐time effect, induced by the spirit of change that allowed the first woman to navigate the party through an electoral campaign. To test this proposition, I conducted an additional robustness test adding a dummy variable for the first women to lead the party (see Model 4 in Table 3). For the sociocultural dimension of political conflict, the results indicate no clear modifications in party programs under the first woman, but party positions on the economic dimension of political conflict shift towards more supportive statements for redistribution. However, despite of this modification, the effects of the sex of the party leader in general remain unchanged.

In a similar vein, a strong one‐time effect might occur if a woman replaces a man as party leader, which could drive the effect of women party leaders per se. To take this into account, another robustness test includes a dummy variable identifying cases in which a party led by a woman was led by a man in the previous election (see Model 5 in Table 3). The model displays no support for such a proposition, while the effects of having a woman party leader persist as outlined above.

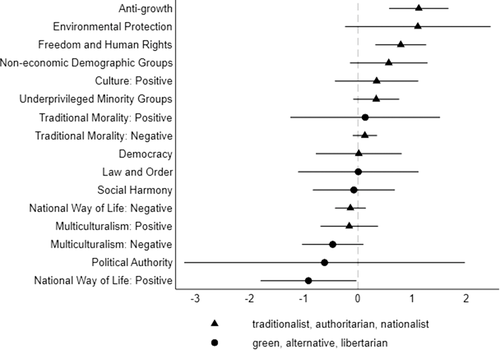

The final step of the analysis unravels the effect of the sex of the party leader on the sixteen components of the index for parties’ sociocultural position. By this mean, I aim to disentangle the causal mechanisms underpinning H1. Originally, the proposition that parties move on this dimension of political competition if they are led by a woman was built on two complementing arguments: First, woman as party leaders might emphasise typical women's issues such as abortion rights or anti‐discrimination laws in party manifestos. Second, they might try to incorporate women's distinct policy positions concerning a broader set of topics such as environmental protection or a liberal lifestyle. Separate linear regression models for each indicator included in the index allow to disentangle these two aspects. The models mirror the modelling strategy for Model 1 (for full models, see Appendices 8 and 9 in the Supporting Information).Footnote 11 Figure 2 presents the effect of the sex of the party leader for each model with 90 per cent confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Effects of women as party leaders on change in party positions on items composing the sociocultural dimension of political competition with 90% confidence intervals.

Note: Full models presented in Appendices 8 and 9 in the Supporting Information. All models are error correction models and include the same list of confounding variables as presented in Table 2, a lagged dependent variable, and party‐level fixed effects.

For many items, there seems to be no relationship between the sex of party leaders and changing occurrences of related phrases in the party manifestos. Notably, the list of items in this category includes positive and negative references to traditional morality. Supportive statements for non‐economic demographic groups (i.e., women) are neither clearly linked to the sex of the party leader. Substantially, these three categories cover what can be described as ‘women's issues’.

However, the share of sentences in manifestos indicating support for green and libertarian issues increases for parties led by a woman, while nationalist statements become less frequent. The strongest positive effect occurs for positive mentions of an anti‐growth economy including opposition to growth that causes environmental damage. Additionally, references to environmental protection also become more frequent. Moreover, statements supporting freedom and human rights, that is, the protection of personal freedoms and civil rights, basic democratic rights, and the rejection of state intervention in the private sphere also increase in prominence if a party is led by a woman as opposed to a man. With the exemption of environmental protection, the standard errors of these coefficients are small and provide robust evidence for a positive trend.

Conclusion

This study contributed to the literature engaging with the difference women as party heads make for party positions. It revealed that green, alternative and libertarian positions become more prominent in party manifestos under women's leadership. More precisely, parties put greater emphasis on anti‐growth, environmental protection and freedom and human rights. I argued that this relationship follows from gendered patterns of socialisation that form the political attitudes of women in the mass and the elite (Gilligan Reference Gilligan1982; Jaffee & Hyde Reference Jaffee and Hyde2000). At the same time, this study confirmed that parties led by a woman do not change their stances concerning redistributive debates in a systematic manner (Kittilson Reference Kittilson2011; Greene & O'Brien Reference Greene and O'Brien2016). That women as party leaders do not impact their organisations’ positions on the economic dimension of political conflict was explained with the observation that women in the elite usually do not share the economic constraints experienced by many women in the citizenry (Reingold Reference Reingold2000; Lloren & Rosset Reference Lloren and Rosset2017). When studying the link between descriptive and substantive representation, scholarly work has to take into account to what extent shared experiences that shape political preferences exist at both, the citizen and elite level.

One important implication of this finding is that the internal division of traditionally excluded groups on certain policy issues may reduce the quality of their representation in the political decision‐making process. Party leaders, as critical actors, are sufficient to ensure responsiveness to the interests of women in the electorate on issues where citizens and elites hold rather coherent policy positions. However, if women are internally divided on an issue, for instance by social class, those in the elite may fall short of displaying the same capacity to promote the interests of the majority of women in the population.

Furthermore, the findings presented in this study imply that shared economic experiences of women at the mass and elite level seem to occur less frequently for party leaders as critical actors than the critical mass of representatives. After all, this article lends some support to previous research finding that larger numbers of women in party groups lead to greater support for redistribution in party manifestos (Kittilson Reference Kittilson2011; Greene & O'Brien Reference Greene and O'Brien2016). If shared experiences are equally decisive for the behaviour of women representatives and party leaders, it must be that larger numbers make it more likely that some of them perceive increasing redistribution as an urgent issue. Women's numerical strength in parliament should then increase within‐group diversity and reduce the risk that women politicians come from privileged backgrounds so that they do not struggle to understand the policy demands of the majority of female citizens. As Goodin (Reference Goodin2004: 454) puts it in a critical assessment of the ‘Politics of Presence’ (Phillips Reference Phillips1995) argument, “the chief function of the physical presence of others who differ from you is, in that connection, merely to remind you of the ‘sheer fact of diversity’ within your community”.

A promising avenue for future research will be to explore the way contextual factors moderate the ability of and incentives for women as party leaders to shape their party's positions. Studies engaging with the power of party leaders, more broadly highlight the role of activist factions and leadership selection mechanisms as limiting factors for leaders’ agenda setting powers (Schumacher et al. Reference Schumacher, Vries and Vis2013; Ceron Reference Ceron2019). The set of literature engaging with the legislative activities of women in parliament emphasises the role of electoral vulnerability, electoral systems and gender quotas (Höhmann Reference Höhmann2020; Dodson Reference Dodson2006; Xydias Reference Xydias2007; Barnes Reference Barnes2016). Uncovering the way these diverse contextual factors shape women's action as party leaders might enable us to reach an even better understanding of the factors that drive change in party manifestos.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix 1: Countries, parties and manifestos included in the dataset

Appendix 2: MARPOR main categories and their assignment to the ideological dimensions of political competition

Appendix 3: Linear regression models of the indices measuring party positions on the sociocultural and economic dimensions (t ‐1 to t 0) with jackknife standard errors

Appendix 4: Multilevel linear regression models of the indices measuring party positions on the sociocultural and economic dimensions (t ‐1 to t 0)

Appendix 5: Linear regression models of the indices measuring party positions on the sociocultural and economic dimensions (t ‐1 to t 0) with different operationalisations of women in parliamentary groups

Appendix 6: Linear regression models of the indices measuring party positions on the sociocultural and economic dimensions (t ‐1 to t 0) including a control variable for inclusiveness of the leadership selection process

Appendix 7: Linear regression models of the indices measuring party positions on the sociocultural and economic dimensions (t ‐1 to t 0) with additional variables for party ideology, party family, the first woman leading the party and sex change in party leadership

Appendix 8: Linear regression of change of party positions on the individual items composing the sociocultural dimension (t ‐1 to t 0) (part 1)

Appendix 9: Linear regression of change of party positions on the individual items composing the sociocultural dimension (t ‐1 to t 0) (part 2)

Supporting Information