1. Introduction

This paper is about a duality between semiframes (an algebraic structure) and semitopologies (a topological one). We will define semiframes, study their duality with semitopologies and also motivate and define relevant well-behavedness conditions on semitopologies and investigate how these conditions dualise to algebraic conditions on semiframes.

Both semitopologies and semiframes are relatively recent developments, arising from a novel application of topological ideas to study decentralised computing systems. So while this paper is about pure mathematics, and it can be read as mathematics for its own sake, it would be nice to understand the motivation for why we looked at these structures in the first place.

1.1 The challenge of decentralised systems

Consider a computing system whose operation is distributed over many collaborating participants, like a blockchain. At a high level, how can we design algorithms that participants can run such that the overall system will act coherently in some appropriate sense?

We could just assume a central controller: a dictator participant. In this case, ‘collaborating’ just means doing as the dictator instructs, and ‘truth’ just means whatever the dictator says.

This is indeed how many distributed systems actually work, but it introduces tradeoffs of latency, scalability, availability and trust, which may or may not be acceptable depending on the use case. Do we trust the dictator? What if it crashes or gets hacked? What if the network is slow? What if it is just busy? Sometimes, we need participants to be able, to a greater or lesser extent, to collaborate independently of central control.

This is the topic of decentralised systems, which are distributed systems that do not adopt a central controller. Decentralised systems are hard to design and implement because control itself is spread out,Footnote 1 but often this is the only architecture that is practical at scale and speed.

While blockchains are an example of decentralised systems,Footnote 2 these design issues arise repeatedly: for example, if we want to manage a system of drones, or satellites, or low-power devices. An ant colony is an interesting example of a (semi-)decentralised system in nature: while a queen ant exists, she does not dictate every action of every ant; for much of the time, individual ants work autonomously, yet they still manage to do so coherently and for the good of the colony. The human brain is another important example of a decentralised system. These systems are all inherently decentralised: they maintain some clear notion of global coherence (e.g., there is an identifiable thing called ‘an ant colony’ or ‘my sense of self’) all while their parts collaborate to perform significant actions independently of any explicit central control.

This leads us to consider the concept of what in Gabbay (Reference Gabbay2024, Reference Gabbay2025) is called an actionable coalition: a set of participants in a decentralised system with sufficient resources to act (if the participants in the coalition choose to do so), without the involvement – that is, without the help, the permission or even the knowledge – of any other participants.Footnote 3

Let us return to our ant colony and consider a column of foraging ants: what are the actionable coalitions here, where the ants’ task is to bring food back to the colony? When the column discovers some food, a relevant notion of actionable coalition is any collection of ants with the physical strength to heave the food back to the hive. Note that the ants do not need anybody to organise them into a group or to tell them what to do: they swarm over the food until some group of them manage to move the food – aha, an actionable coalition has assembled and agreed on their action! – and then that coalition gets on with heaving while the rest of the ants move on.

When we describe an actionable coalition as ‘a group of participants with the resources to act’, note that – this being a decentralised system – the action concerns just participants in that coalition and not the entire set of participants. Contrast with, for example, a national voting system, which is distributed but still centralised in the sense that the winning candidate wins for everybody, not just for the people who voted for that candidate.Footnote 4

A union of actionable coalitions is an actionable coalition.Footnote

5

This makes the set of all actionable coalitions look a bit like a topology, except that an intersection of actionable coalitions need not be actionable (just because sets

![]() $S$

and

$S$

and

![]() $S'$

are each collectively strong enough to act does not mean that

$S'$

are each collectively strong enough to act does not mean that

![]() $S\cap S'$

is; e.g.,

$S\cap S'$

is; e.g.,

![]() $S\cap S'$

may consist of just a single ant).

$S\cap S'$

may consist of just a single ant).

This brings us to a mathematical abstraction: point-set semitopology, which generalises point-set topology by removing the condition that intersections of open sets are necessarily open.

1.2 Point-set semitopologies

Notation 1.2.1.

Suppose

![]() $\mathsf{P}$

is a set. Write

$\mathsf{P}$

is a set. Write

![]() $\textit{pow}(\mathsf{P})$

for the powerset of

$\textit{pow}(\mathsf{P})$

for the powerset of

![]() $\mathsf{P}$

(the set of subsets of

$\mathsf{P}$

(the set of subsets of

![]() $\mathsf{P}$

).

$\mathsf{P}$

).

Definition 1.2.2. A semitopological space, or semitopology for short, consists of a pair

![]() $(\mathsf{P}, \mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P}))$

of a (possibly empty) set

$(\mathsf{P}, \mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P}))$

of a (possibly empty) set

![]() $\mathsf{P}$

of points and a set

$\mathsf{P}$

of points and a set

![]() $\mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})\subseteq \textit{pow}(\mathsf{P})$

of open sets, such that:

$\mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})\subseteq \textit{pow}(\mathsf{P})$

of open sets, such that:

-

(1)

$\varnothing \in \mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})$

and

$\varnothing \in \mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})$

and

$\mathsf{P}\in \mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})$

.

$\mathsf{P}\in \mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})$

. -

(2) If

$X\subseteq \mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})$

then

$X\subseteq \mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})$

then

$\bigcup X\in \mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})$

.Footnote

6

$\bigcup X\in \mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})$

.Footnote

6

We may write

![]() $\mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})$

just as

$\mathsf{Open}(\mathsf{P})$

just as

![]() $\mathsf{Open}$

, if

$\mathsf{Open}$

, if

![]() $\mathsf{P}$

is irrelevant or understood, and we may write

$\mathsf{P}$

is irrelevant or understood, and we may write

![]() $\mathsf{Open}_{\neq \varnothing }$

for the set of nonempty open sets.

$\mathsf{Open}_{\neq \varnothing }$

for the set of nonempty open sets.

Remark 1.2.3 (Justification for semitopologies). A classic text, Vickers (Reference Vickers1989) justifies topology as follows:

-

(1) Logically, open sets model affirmations:Footnote 7 an open set

$O$

corresponds to an affirmation (of

$O$

corresponds to an affirmation (of

$O$

) (Vickers, Reference Vickers1989, p. 10).

$O$

) (Vickers, Reference Vickers1989, p. 10). -

(2) Computationally, open sets model semidecidable properties. See the first page of the preface in Vickers (Reference Vickers1989).

We can justify semitopologies in a similar style as follows:

-

(1) Logically, open sets model actionable affirmations: an open set

$O$

corresponds to an outcome that is agreed on and can be actioned within

$O$

corresponds to an outcome that is agreed on and can be actioned within

$O$

.

$O$

. -

(2) Computationally, open sets model actionable outcomes.

So the distinction between topology and semitopology is this: topology is about things that can be positively said, whereas semitopology is about things that can be positively done.

Identifying actionable coalitions as a topological concept is new, but as is often the case for key concepts, with hindsight we can see them everywhere. The notion corresponds to that of a quorum in the classic distributed systems literature (Lamport, Reference Lamport1998). Social choice theorists have a similar notion called a winning coalition (Riker, Reference Riker1962, Item 5, p. 40). In blockchains, the XRP Ledger (Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Youngs and Britto2014) and the Stellar network (Lokhava et al., Reference Lokhava, Losa, Mazières, Hoare, Barry, Gafni, Jove, Malinowsky and McCaleb2019) have explicit notions of actionable coalition, in the sense that a participant must specify information about their desired actionable coalitions when they sign up to the system. In Ethereum and other proof-of-stake blockchains, an actionable coalition is (roughly speaking) any group of participants with more than half of the voting power of the system.

1.3 Well-behavedness conditions on semitopologies

It turns out that we can understand a surprising amount about a decentralised system just by analysing its actionable coalitions; that is, by viewing it as a semitopology. And when we do, the most relevant and interesting semitopologies turn out to be ill-behaved from the usual topological viewpoint, because they are almost never Hausdorff; indeed, the most well-behaved semitopologies satisfy an anti-Hausdorff property of being intertwined, such that all of their open set intersect.

This is because if all actionable coalitions intersect, then any two actions that are taken must be compatible, in the sense that there must exist at least one participant who was able to take both actions. This implies a practically useful form of coherence for the overall system: while it is not the case that participants must act in synchrony (since that would not be decentralised), any actions that are taken must be compatible on some nonempty overlap; we make this formal in Theorem3.2.3 and Corollary 3.2.4. In practice, it turns out that this property is often enough to derive important coherence properties for the overall system.

Notions of transitive open set (topen) and regular point become central to the theory, where topens are sets of pairwise intertwined participants (all their open neighbourhoods intersect), and points are called ‘regular’ when they have a topen neighbourhood. Briefly and in a nutshell: ‘good’ semitopologies have lots of regular points, and the best ones consist entirely of regular points.

The question we should ask then is: what are semitopologies, and what are well-behavedness properties like having topens and being regular?

One answer is that things are what the definitions define them to be – for example, semitopologies are Definition 1.2.2 – but the reader may know that we can use algebra to give better answers. In particular, looking at Definition 1.2.2 it might appear that semitopologies are just complete join-semilattices in sets. Well, this is not quite true, as we shall see.

1.4 Semiframes: the algebraic dual to semitopologies

There is a well-known recipe for understanding sets-based structures: we dualise them. That is, we decide what the morphisms should be (answer: continuous functions), we build a dual category of semiframes, and we study that.

It will turn out that a semiframe is a compatible complete semilattice. What ‘compatibility’ means is given in Definition 7.3.1, and it has to do with an algebraic abstraction of the nonempty intersection of open sets. What we can observe here is that the devil will be in the details (as always): the definition ‘compatible complete semilattice’ is not immediately obvious, and the proofs require work, and the duals to the well-behavedness conditions on semitopologies translate to algebraic structure in the world of semiframes.

Studying the dualities between semitopologies and semiframes, and how well-behavedness properties on points translate (or do not translate!) to their algebraic duals, is the topic of the paper.

Remark 1.4.1 (Semitopologies are compatible complete join-semilattices in sets). Something interesting will happen when we dualise semitopologies: we will find ourselves obliged to introduce the notion of a compatibility relation

![]() $\ast$

(Definition 7.2.1). This arises naturally twice:

$\ast$

(Definition 7.2.1). This arises naturally twice:

-

• as a key technicality in our duality result, and also

-

• as an algebraic analogue of the intertwinedness property

$\between$

which we need to express well-behavedness properties such as regularity (Section 4).

$\between$

which we need to express well-behavedness properties such as regularity (Section 4).

It is interesting that

![]() $\ast$

/

$\ast$

/

![]() $\between$

appears for two reasons that, on the face of things, have quite distinct origins: algebraically in the duality and as a pragmatically motivated well-behavedness condition on sets.

$\between$

appears for two reasons that, on the face of things, have quite distinct origins: algebraically in the duality and as a pragmatically motivated well-behavedness condition on sets.

So a message of our study of duality is to corroborate that intertwinedness is both mathematically fundamental and practically useful, and that (as noted above) semitopologies are not just complete join semilattices in sets, but something a bit richer, namely compatible complete join-semilattices in sets.

1.5 Map of the paper

-

(1) Section 1 is the Introduction. You Are Here.

-

(2) In Section 2, we show how continuity corresponds to local agreement (Definition 1.2.2 and Lemma 2.2.4).

-

(3) In Section 3, we discuss transitive sets, topens and intertwined points. These are all anti-separation well-behavedness properties; for example, transitive and topen sets are guaranteed to be in agreement, in a sense made precise in Theorem3.2.3 and Corollary 3.2.4.

-

(4) In Section 4, we classify points in more detail, introducing notions of regular, weakly regular, and quasiregular points (Definition 4.1.4).Footnote 8

Regular points are points contained in a topen set, and as per Theorem3.2.3, they display good behaviour.

-

(5) In Section 5, we characterise regularity as regular = weakly regular + unconflicted: see Theorem5.3.4.

-

(6) In Section 6, we characterise regularity as regular = quasiregular + hypertransitive: see Theorem6.3.3.

This completes our treatment of point-set semitopologies, and next we dualise, as follows:

-

(7) In Section 7, we introduce semiframes. These are the algebraic version of semitopologies, and they are to semitopologies as frames are to topologies.

We discover that semiframes are not just join-semilattices; semiframes are compatible semilattices, which include a compatibility relation

$\ast$

to abstract the property of set intersection

$\ast$

to abstract the property of set intersection

$\between$

(see Remark 1.4.1).

$\between$

(see Remark 1.4.1). -

(8) In Section 8, we introduce semifilters. These play a similar role as filters do in topologies, except that semifilters have a compatibility condition instead of closure under finite meets. We develop the notion of abstract points (completely prime semifilters) and show how to build a semitopology out of the abstract points of a semiframe.

-

(9) In Section 9, we introduce sober semitopologies and spatial semiframes. The reader familiar with categorical duality may be familiar with these conditions, though some details are significantly different from the topological case (see, for instance, the discussion in Section 9.3.2).

-

(10) In Section 10, we consider the duality between suitable categories of (sober) semitopologies and (spatial) semiframes.

-

(11) In Section 11, we dualise the well-behavedness conditions from Section 3 to algebraic versions. The correspondence is good (Proposition 11.6.2) but also imperfect in some interesting ways (Remark 11.8.11).

-

(12) In Section 12, we conclude and discuss related and future work.

1.6 Comments on the context of this research

Remark 1.6.1 (Algebraic topology

![]() $\neq$

semitopology and semiframes). Algebraic topology has been applied to the solvability of distributed-computing tasks in computational models (e.g., the impossibility of

$\neq$

semitopology and semiframes). Algebraic topology has been applied to the solvability of distributed-computing tasks in computational models (e.g., the impossibility of

![]() $k$

-set consensus and the Asynchronous Computability Theorem (Herlihy and Shavit, Reference Herlihy and Shavit1993; Borowsky and Gafni, Reference Borowsky and Gafni1993; Saks and Zaharoglou, Reference Saks and Zaharoglou2000); see Herlihy et al. (Reference Herlihy, Kozlov and Rajsbaum2013) for a survey).

$k$

-set consensus and the Asynchronous Computability Theorem (Herlihy and Shavit, Reference Herlihy and Shavit1993; Borowsky and Gafni, Reference Borowsky and Gafni1993; Saks and Zaharoglou, Reference Saks and Zaharoglou2000); see Herlihy et al. (Reference Herlihy, Kozlov and Rajsbaum2013) for a survey).

This paper is not that! Algebra and topology are versatile tools: this paper is algebraic and topological, but in different senses and to different ends.

Remark 1.6.2 (Where the interesting properties are). Topology often studies spaces with strong separability properties between points, like Hausdorff separability. For our applications, the well-behavedness properties of semitopologies and corresponding properties in semiframes centre on clusters of points that cannot be separated.

For example, we state and discuss an ‘anti-Hausdorff’ anti-separation property which we call being intertwined (see Definition 3.5.1 and Remark 3.5.7). Within an intertwined set, continuity implies agreement in a particularly strong sense (see Corollary 3.5.6). This leads us to study classes of semitopologies and semiframes with various anti-separation well-behavedness conditions; see most notably regularity (Sections 4 and 11).

Remark 1.6.3. As the reader may know, frames and locales are the same thing: the category of locales is just the categorical opposite of the category of frames. So every time we write ‘semiframe’, the reader can safely read ‘semilocale'; these are two names for essentially the same structure up to reversing arrows.

The literature on frames and locales is huge, as indeed is the literature on topology. Classic texts are Johnstone (Reference Johnstone1986) and Mac Lane and Moerdijk (Reference Mac Lane and Moerdijk1992). More recent and very readable presentations are in Picado and Pultr (Reference Picado and Pultr2012, Reference Picado and Pultr2021). This literature is a rich source of ideas for things to do with semiframes, with respect to which we cannot possibly be comprehensive in this single paper: there are many things of interest that we simply have not done yet, or perhaps have not even (yet) realised could be done, and this is a feature, not a bug, since it reflects a wide scope for possible future research.

A partial list of possible future work is in Section 12.3; and lists of properties and non-properties of semiframes/semitopologies versus frames/topologies are in Sections 8.2.1, 8.2.2, 9.3.2 and 12.1.

Remark 1.6.4. This paper expands on selected material from a technical monograph by Gabbay (Reference Gabbay2024), and it continues where a journal paper on point-set topologies by Gabbay (Reference Gabbay2025) left off.

For this document to be meaningful and self-contained, we include some material on point-set semitopologies – just as a treatment of frames would define point-set topologies. The material has been organised, edited and streamlined specifically to provide a direct route to semiframes and their duality.

Our goal for this paper is to offer an accessible, dedicated and self-contained journal exposition on what is currently understood about semiframes and their relation to point-set semitopologies, in the context of current developments in decentralised systems.

Remark 1.6.5 (Who should read this paper?). This work is aimed at the advanced researcher interested in a new kind of point-free topology, albeit one that is grounded in the practical needs of modern decentralised systems, and at the advanced practitioner interested in seeing what they may already be doing in a new (and more abstract) mathematical light.

I hope this paper will stimulate interest in compatible complete join-semilattices and related structures as an elegant abstraction of decentralised systems.

2. Semitopology

2.1 Definition and examples

2.1.1 Semitopologies are not topologies

Recall from Definition 1.2.2 the definition of a semitopology. As a set structure, a semitopology on

![]() $\mathsf{P}$

is like a topology on

$\mathsf{P}$

is like a topology on

![]() $\mathsf{P}$

, but without the condition that the intersection of two open sets be an open set. This gives semitopologies their own distinct character, and we can see this before we have even developed much of the theory, as we discuss in Remark 2.1.1 and Lemma 2.1.2:

$\mathsf{P}$

, but without the condition that the intersection of two open sets be an open set. This gives semitopologies their own distinct character, and we can see this before we have even developed much of the theory, as we discuss in Remark 2.1.1 and Lemma 2.1.2:

Remark 2.1.1. Every semitopology

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

gives rise to a topology just by closing opens under intersections. But semitopologies are far more than just subbases for a corresponding topology:

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

gives rise to a topology just by closing opens under intersections. But semitopologies are far more than just subbases for a corresponding topology:

-

(1) Completing a semitopology to a topology by closing under intersections loses information.

For example, the ‘many’, ‘all-but-one’ and ‘more-than-one’ semitopologies in Example 2.1.4 express three distinct notions of quorum, yet all three yield the discrete semitopology (Definition 2.1.3) if we close under intersections and

$\mathsf{P}$

is infinite. See also the overview in Section 12.1.

$\mathsf{P}$

is infinite. See also the overview in Section 12.1. -

(2) We are explicitly interested in situations where intersections of open sets need not be open, due to our motivating interpretation of open sets as actionable coalitions (as discussed in Section 1).

Much of the difference in flavour between topologies and semitopologies comes down to this:

Lemma 2.1.2.

-

(1) In topologies, if a point

$p$

has a minimal open neighbourhood, then it is least (= unique minimal).

$p$

has a minimal open neighbourhood, then it is least (= unique minimal).

-

(2) In semitopologies, a point may have multiple distinct minimal open neighbourhoods.

Proof.

To see that in a topology every minimal open neighbourhood is least, just note that if

![]() $p\in A$

and

$p\in A$

and

![]() $p\in B$

, then

$p\in B$

, then

![]() $p\in A\cap B$

. So if

$p\in A\cap B$

. So if

![]() $A$

and

$A$

and

![]() $B$

are two minimal open neighbourhoods, then

$B$

are two minimal open neighbourhoods, then

![]() $A\cap B$

is contained in both and, by minimality, is equal to both.

$A\cap B$

is contained in both and, by minimality, is equal to both.

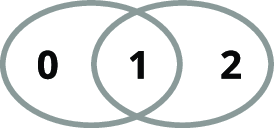

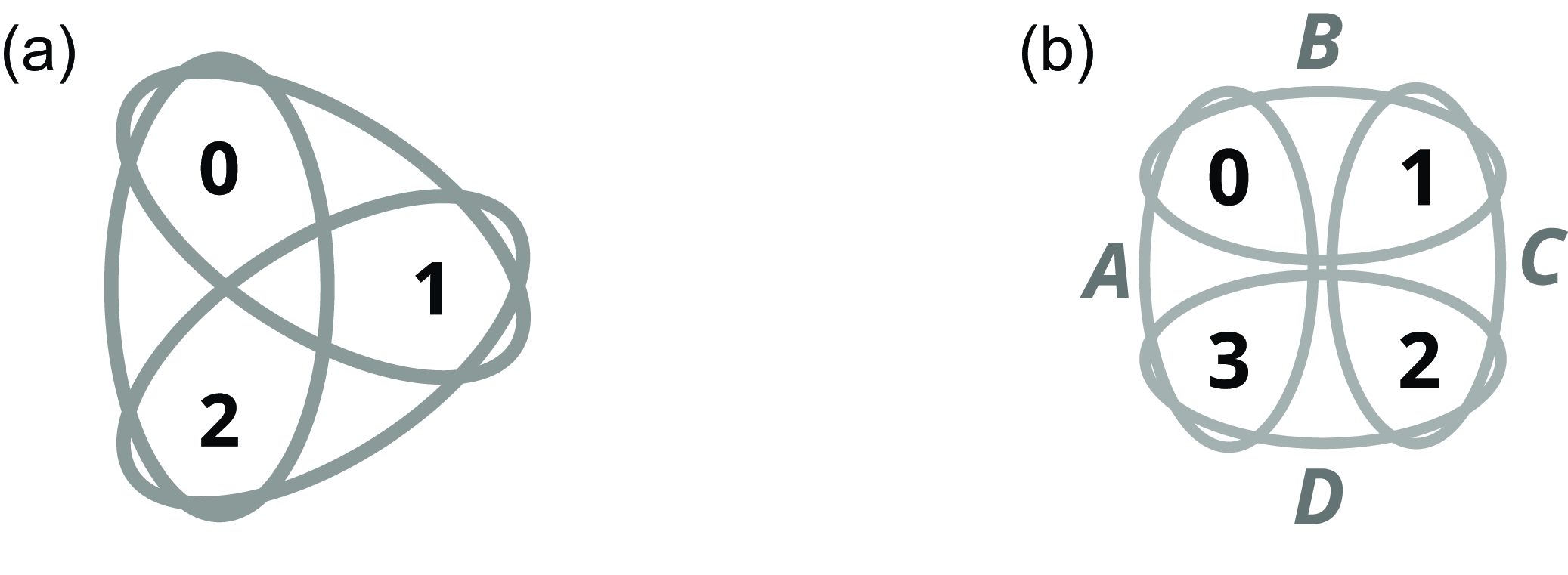

Figure 1. An example of a point with two minimal open neighbourhoods (Lemma 2.1.2).

To see that in a semitopology a minimal open neighbourhood need not be least, it suffices to provide an example. Consider

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

defined as follows, as illustrated in Figure 1:

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

defined as follows, as illustrated in Figure 1:

-

•

$\mathsf{P}=\{0,1,2\}$

$\mathsf{P}=\{0,1,2\}$

-

•

$\mathsf{Open} = \bigl \{ \varnothing ,\ \{0,1\},\ \{1,2\},\ \{0,1,2\} \bigr \}$

$\mathsf{Open} = \bigl \{ \varnothing ,\ \{0,1\},\ \{1,2\},\ \{0,1,2\} \bigr \}$

Note that

![]() $1$

has two minimal open neighbourhoods:

$1$

has two minimal open neighbourhoods:

![]() $\{0,1\}$

and

$\{0,1\}$

and

![]() $\{1,2\}$

.

$\{1,2\}$

.

2.1.2 Examples

As standard, we can make any set

![]() $\mathsf{Val}$

into a semitopology (indeed, it is also a topology) just by letting open sets be the powerset:

$\mathsf{Val}$

into a semitopology (indeed, it is also a topology) just by letting open sets be the powerset:

Definition 2.1.3.

-

(1) Call

$(\mathsf{P},\textit{pow}(\mathsf{P}))$

the discrete semitopology on

$(\mathsf{P},\textit{pow}(\mathsf{P}))$

the discrete semitopology on

$\mathsf{P}$

.

$\mathsf{P}$

.We may call a set with the discrete semitopology a semitopology of values, and when we do, we will usually call it

$\mathsf{Val}$

. We may identify

$\mathsf{Val}$

. We may identify

$\mathsf{Val}$

-the-set and

$\mathsf{Val}$

-the-set and

$\mathsf{Val}$

-the-discrete-semitopology; meaning will always be clear.

$\mathsf{Val}$

-the-discrete-semitopology; meaning will always be clear. -

(2) When

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

$\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values, we may call a function

$\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values, we may call a function

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

a value assignment.

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

a value assignment.Note that a value just assigns values to points, and in particular, we do not assume a priori that it is continuous, where continuity is defined just as for topologies (see Definition 2.2.1).

Example 2.1.4. We consider further examples of semitopologies:

-

(1) Every topology is also a semitopology; intersections of open sets are allowed to be open in a semitopology; they are just not constrained to be open. In particular, the discrete topology is also a discrete semitopology (Definition 2.1.3(1)).

-

(2) The initial semitopology

$(\varnothing ,\{\varnothing \})$

and the final semitopology

$(\varnothing ,\{\varnothing \})$

and the final semitopology

$(\{\ast \},\{\varnothing ,\{\ast \}\})$

are semitopologies.

$(\{\ast \},\{\varnothing ,\{\ast \}\})$

are semitopologies. -

(3) An important discrete semitopological space is

We may silently treat \begin{equation*} \mathbb B=\{\bot ,\top \} \quad \text{with the discrete semitopology}\quad \mathsf{Open}(\mathbb B)=\{\varnothing , \{\bot \},\{\top \},\{\bot ,\top \}\}. \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \mathbb B=\{\bot ,\top \} \quad \text{with the discrete semitopology}\quad \mathsf{Open}(\mathbb B)=\{\varnothing , \{\bot \},\{\top \},\{\bot ,\top \}\}. \end{equation*}

$\mathbb B$

as a (discrete) semitopological space henceforth.

$\mathbb B$

as a (discrete) semitopological space henceforth.

-

(4) Take

$\mathsf{P}$

to be any nonempty set. Let the trivial semitopology (this is also a topology) on

$\mathsf{P}$

to be any nonempty set. Let the trivial semitopology (this is also a topology) on

$\mathsf{P}$

haveSo (as usual) there are only two open sets: the one containing nothing and the one containing every point.Footnote 9

$\mathsf{P}$

haveSo (as usual) there are only two open sets: the one containing nothing and the one containing every point.Footnote 9 \begin{equation*} \mathsf{Open} =\{\varnothing , \mathsf{P}\}. \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \mathsf{Open} =\{\varnothing , \mathsf{P}\}. \end{equation*}

The only nonempty open is

$\mathsf{P}$

itself, reflecting a notion of actionable coalition that requires unanimous agreement.

$\mathsf{P}$

itself, reflecting a notion of actionable coalition that requires unanimous agreement. -

(5) Suppose

$\mathsf{P}$

is a set and

$\mathsf{P}$

is a set and

$\mathscr F\subseteq \textit{pow}(\mathsf{P})$

is nonempty and up-closed (so if

$\mathscr F\subseteq \textit{pow}(\mathsf{P})$

is nonempty and up-closed (so if

$P\in \mathscr F$

and

$P\in \mathscr F$

and

$P\subseteq P'\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

then

$P\subseteq P'\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

then

$P'\in \mathscr F$

, then

$P'\in \mathscr F$

, then

$(\mathsf{P},\mathscr F)$

is a semitopology. This is not necessarily a topology, because we do not insist that

$(\mathsf{P},\mathscr F)$

is a semitopology. This is not necessarily a topology, because we do not insist that

$\mathscr F$

is a filter (i.e., is closed under intersections).

$\mathscr F$

is a filter (i.e., is closed under intersections).We give four sub-examples for different choices of

$\mathscr P\subseteq \textit{pow}(\mathsf{P})$

:

$\mathscr P\subseteq \textit{pow}(\mathsf{P})$

:-

a. Take

$\mathsf{P}$

to be any finite nonempty set. Let the supermajority semitopology haveSo

$\mathsf{P}$

to be any finite nonempty set. Let the supermajority semitopology haveSo \begin{equation*} \mathsf{Open} =\{\varnothing \}\cup \{O\subseteq \mathsf{P} \mid \textit{cardinality}(O)\geq \frac {2}{3}*\textit{cardinality}(\mathsf{P})\}. \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \mathsf{Open} =\{\varnothing \}\cup \{O\subseteq \mathsf{P} \mid \textit{cardinality}(O)\geq \frac {2}{3}*\textit{cardinality}(\mathsf{P})\}. \end{equation*}

$O$

is open when it contains at least two-thirds of the points.

$O$

is open when it contains at least two-thirds of the points.

Two-thirds is a typical threshold used for making progress in consensus algorithms.

-

b. Take

$\mathsf{P}$

to be any nonempty set. Let the many semitopology haveFor example, if

$\mathsf{P}$

to be any nonempty set. Let the many semitopology haveFor example, if \begin{equation*} \mathsf{Open} = \{\varnothing \}\cup \{O\subseteq \mathsf{P} \mid \textit{cardinality}(O)=\textit{cardinality}(\mathsf{P})\} . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \mathsf{Open} = \{\varnothing \}\cup \{O\subseteq \mathsf{P} \mid \textit{cardinality}(O)=\textit{cardinality}(\mathsf{P})\} . \end{equation*}

$\mathsf{P}=\mathbb N$

then open sets include

$\mathsf{P}=\mathbb N$

then open sets include

$\textit{evens}=\{2*n \mid n\in \mathbb N\}$

and

$\textit{evens}=\{2*n \mid n\in \mathbb N\}$

and

$\textit{odds}=\{2*n{+} 1 \mid n\in \mathbb N\}$

.

$\textit{odds}=\{2*n{+} 1 \mid n\in \mathbb N\}$

.

Its notion of open set captures an idea that an actionable coalition is a set that may not be all of

$\mathsf{P}$

, but does at least biject with it.

$\mathsf{P}$

, but does at least biject with it. -

c. Take

$\mathsf{P}$

to be any nonempty set. Let the all-but-one semitopology haveThis semitopology is not a topology.

$\mathsf{P}$

to be any nonempty set. Let the all-but-one semitopology haveThis semitopology is not a topology. \begin{equation*} \mathsf{Open} = \{\varnothing ,\ \mathsf{P}\}\cup \{\mathsf{P}\setminus \{p\}\mid p\in \mathsf{P}\} . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \mathsf{Open} = \{\varnothing ,\ \mathsf{P}\}\cup \{\mathsf{P}\setminus \{p\}\mid p\in \mathsf{P}\} . \end{equation*}

The notion of actionable coalition here is that there may be at most one objector (but not two).

-

d. Take

$\mathsf{P}$

to be any set with cardinality at least

$\mathsf{P}$

to be any set with cardinality at least

$2$

. Let the more-than-one semitopology haveThis semitopology is not a topology.

$2$

. Let the more-than-one semitopology haveThis semitopology is not a topology. \begin{equation*} \mathsf{Open} = \{\varnothing \}\cup \{O\subseteq \mathsf{P} \mid \textit{cardinality}(O) \geq 2\} . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \mathsf{Open} = \{\varnothing \}\cup \{O\subseteq \mathsf{P} \mid \textit{cardinality}(O) \geq 2\} . \end{equation*}

This notion of actionable coalition reflects a security principle in banking and accounting (and elsewhere) of separation of duties, that functional responsibilities be separated such that at least two people are required to complete an action – so that errors (or worse) cannot be made without being discovered by another person.

-

-

(6) Take

$\mathsf{P}=\mathbb R$

(the set of real numbers) and let open sets be generated by intervals of the form

$\mathsf{P}=\mathbb R$

(the set of real numbers) and let open sets be generated by intervals of the form

$[0,r)$

or

$[0,r)$

or

$(- r,0]$

for any strictly positive real number

$(- r,0]$

for any strictly positive real number

$r\gt 0$

.

$r\gt 0$

.This semitopology is not a topology, since (e.g.,)

$(1,0]$

and

$(1,0]$

and

$[0,1)$

are open, but their intersection

$[0,1)$

are open, but their intersection

$\{0\}$

is not open.

$\{0\}$

is not open. -

(7) Naor and Wool (Reference Naor and Wool1994) discuss a notion of quorum system, defined as any collection of pairwise intersecting sets. Quorum systems are key to the theory and practical implementation of consensus algorithms.

Every quorum system gives rise naturally to the least semitopology that contains it, just by closing under arbitrary unions.

To give one specific example of a quorum system from Naor and Wool (Reference Naor and Wool1994), consider

$n\times n$

grid of cells with quorums being sets consisting of any full row and a full column; note that any two quorums must intersect in at least two points. We obtain a semitopology just by closing under arbitrary unions.

$n\times n$

grid of cells with quorums being sets consisting of any full row and a full column; note that any two quorums must intersect in at least two points. We obtain a semitopology just by closing under arbitrary unions.

2.2 Continuity and its interpretation as agreement

Definition 2.2.1. We import standard topological notions of inverse image and continuity:

-

(1) Suppose

$\mathsf{P}$

and

$\mathsf{P}$

and

$\mathsf{P}'$

are any sets and

$\mathsf{P}'$

are any sets and

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{P}'$

is a function. Suppose

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{P}'$

is a function. Suppose

$O'\subseteq \mathsf{P}'$

. Then write

$O'\subseteq \mathsf{P}'$

. Then write

$f^{\text{-}1}(O')$

for the inverse image or preimage of

$f^{\text{-}1}(O')$

for the inverse image or preimage of

$O'$

, defined by

$O'$

, defined by \begin{equation*} f^{\text{-}1}(O')=\{p{\in }\mathsf{P} \mid f(p)\in O'\} . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} f^{\text{-}1}(O')=\{p{\in }\mathsf{P} \mid f(p)\in O'\} . \end{equation*}

-

(2) Suppose

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

and

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

and

$(\mathsf{P}',\mathsf{Open}')$

are semitopological spaces (Definition 1.2.2). Call a function

$(\mathsf{P}',\mathsf{Open}')$

are semitopological spaces (Definition 1.2.2). Call a function

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{P}'$

continuous when the inverse image of an open set is open. In symbols:

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{P}'$

continuous when the inverse image of an open set is open. In symbols: \begin{equation*} \forall O'\in \mathsf{Open}'. f^{\text{-}1}(O')\in \mathsf{Open} . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \forall O'\in \mathsf{Open}'. f^{\text{-}1}(O')\in \mathsf{Open} . \end{equation*}

-

(3) Call a function

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{P}'$

continuous at

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{P}'$

continuous at

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

whenIn words:

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

whenIn words: \begin{equation*} \forall O'{\in }\mathsf{Open}'.f(p)\in O'\Longrightarrow \exists O_{p,O'}{\in }\mathsf{Open}.p\in O_{p,O'}\land O_{p,O'}\subseteq f^{\text{-}1}(O') . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \forall O'{\in }\mathsf{Open}'.f(p)\in O'\Longrightarrow \exists O_{p,O'}{\in }\mathsf{Open}.p\in O_{p,O'}\land O_{p,O'}\subseteq f^{\text{-}1}(O') . \end{equation*}

$f$

is continuous at

$f$

is continuous at

$p$

when the inverse image of every open neighbourhood of

$p$

when the inverse image of every open neighbourhood of

$f(p)$

contains an open neighbourhood of

$f(p)$

contains an open neighbourhood of

$p$

.

$p$

.

-

(4) Call a function

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{P}'$

continuous on

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{P}'$

continuous on

$P\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

when

$P\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

when

$f$

is continuous at every

$f$

is continuous at every

$p\in P$

.

$p\in P$

.

Lemma 2.2.2.

Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

and

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

and

![]() $(\mathsf{P}',\mathsf{Open}')$

are semitopological spaces (Definition 1.2.2) and suppose

$(\mathsf{P}',\mathsf{Open}')$

are semitopological spaces (Definition 1.2.2) and suppose

![]() $f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{P}'$

is a function. Then the following are equivalent:

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{P}'$

is a function. Then the following are equivalent:

Proof.

The top-down implication is immediate, taking

![]() $O=f^{\text{-}1}(O')$

.

$O=f^{\text{-}1}(O')$

.

For the bottom-up implication, given

![]() $p$

and an open neighbourhood

$p$

and an open neighbourhood

![]() $O'\ni f(p)$

, we write

$O'\ni f(p)$

, we write

Above,

![]() $O_{p,O'}$

is the open neighbourhood of

$O_{p,O'}$

is the open neighbourhood of

![]() $p$

in the preimage of

$p$

in the preimage of

![]() $O'$

, which we know exists by Definition 2.2.1(3).

$O'$

, which we know exists by Definition 2.2.1(3).

It is routine to check that

![]() $O= f^{\text{-}1}(O')$

, and since this is a union of open sets, it is open.

$O= f^{\text{-}1}(O')$

, and since this is a union of open sets, it is open.

Definition 2.2.3. Suppose that:

-

•

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and -

•

$\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values (Definition 2.1.3(1)) and

$\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values (Definition 2.1.3(1)) and -

•

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

is a value assignment (Definition 2.1.3(2); an assignment of a value to each element in

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

is a value assignment (Definition 2.1.3(2); an assignment of a value to each element in

$\mathsf{P}$

).

$\mathsf{P}$

).

Then:

-

(1) Call

$f$

locally constant at

$f$

locally constant at

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

when there exists

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

when there exists

$p\in O_p\in \mathsf{Open}$

such thatSo

$p\in O_p\in \mathsf{Open}$

such thatSo \begin{equation*} \forall p'{\in }O_p.f(p)=f(p'). \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \forall p'{\in }O_p.f(p)=f(p'). \end{equation*}

$f$

is locally constant at

$f$

is locally constant at

$p$

when it is constant on some open neighbourhood

$p$

when it is constant on some open neighbourhood

$O_p$

of

$O_p$

of

$p$

.

$p$

.

-

(2) Call

$f$

locally constant when it is locally constant at every

$f$

locally constant when it is locally constant at every

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

.

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

.

Lemma 2.2.4.

Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

![]() $\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values and

$\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values and

![]() $f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

is a value assignment. Then the following are equivalent:

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

is a value assignment. Then the following are equivalent:

Proof. This is just by pushing around definitions, but we spell it out:

-

• Suppose

$f$

is continuous, consider

$f$

is continuous, consider

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

and write

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

and write

$v=f(p)$

. By our assumptions, we know that

$v=f(p)$

. By our assumptions, we know that

$f^{\text{-}1}(v)$

is open, and

$f^{\text{-}1}(v)$

is open, and

$p\in f^{\text{-}1}(v)$

. This is an open neighbourhood

$p\in f^{\text{-}1}(v)$

. This is an open neighbourhood

$O_p$

on which

$O_p$

on which

$f$

is constant, so we are done.

$f$

is constant, so we are done. -

• Suppose

$f$

is locally constant, consider

$f$

is locally constant, consider

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

, and write

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

, and write

$v=f(p)$

. By assumption we can find

$v=f(p)$

. By assumption we can find

$p\in O_p\in \mathsf{Open}$

on which

$p\in O_p\in \mathsf{Open}$

on which

$f$

is constant, so that

$f$

is constant, so that

$O_p\subseteq f^{\text{-}1}(v)$

.

$O_p\subseteq f^{\text{-}1}(v)$

.

2.3 Neighbourhoods of a point

Definition 2.3.1 is standard from topology, and Lemma 2.3.2 is a (standard) characterisation of openness, which will be useful later:

Definition 2.3.1. Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

![]() $p\in \mathsf{P}$

and

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

and

![]() $O\in \mathsf{Open}$

. Then:

$O\in \mathsf{Open}$

. Then:

-

(1) Call

$O$

an open neighbourhood of

$O$

an open neighbourhood of

$p$

when

$p$

when

$p\in O$

.

$p\in O$

. -

(2) Define

$\textit{nbhd}(p)\subseteq \mathsf{Open}$

the neighbourhood system of

$\textit{nbhd}(p)\subseteq \mathsf{Open}$

the neighbourhood system of

$p$

by

$p$

by \begin{equation*} \textit{nbhd}(p)=\{O\in \mathsf{Open} \mid p\in \mathsf{Open}\} . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \textit{nbhd}(p)=\{O\in \mathsf{Open} \mid p\in \mathsf{Open}\} . \end{equation*}

Lemma 2.3.2.

Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology, and suppose

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology, and suppose

![]() $P\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

is any set of points. Then the following are equivalent:

$P\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

is any set of points. Then the following are equivalent:

-

•

$P\in \mathsf{Open}$

.

$P\in \mathsf{Open}$

. -

• Every point

$p$

in

$p$

in

$P$

has an open neighbourhood in

$P$

has an open neighbourhood in

$P$

.

$P$

.

In symbols we can write:

Proof.

If

![]() $P$

is open, then

$P$

is open, then

![]() $P$

itself is an open neighbourhood for every point that it contains.

$P$

itself is an open neighbourhood for every point that it contains.

Conversely, if every

![]() $p\in P$

contains some open neighbourhood

$p\in P$

contains some open neighbourhood

![]() $p\in O_p \subseteq P$

, then

$p\in O_p \subseteq P$

, then

![]() $P=\bigcup \{O_p\mid p\in P\}$

, and this is open by condition 2 of Definition 1.2.2.

$P=\bigcup \{O_p\mid p\in P\}$

, and this is open by condition 2 of Definition 1.2.2.

Remark 2.3.3. An initial inspiration for modelling collaborative action using semitopologies came from noting that the standard topological property described above in Lemma 2.3.2 corresponds to the quorum sharing property in (Losa et al., Reference Losa, Gafni, Mazières and Suomela2019, Property 1); the connection to topological ideas had not been noticed in Losa et al. (Reference Losa, Gafni, Mazières and Suomela2019).

3. Transitive Sets & Topens

3.1 Some background on set intersection

Some notation will be convenient:

Notation 3.1.1.

Suppose

![]() $X$

,

$X$

,

![]() $Y$

and

$Y$

and

![]() $Z$

are sets.

$Z$

are sets.

-

(1) Write

When \begin{equation*} X\between Y \quad \text{when}\quad X\cap Y\neq \varnothing . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} X\between Y \quad \text{when}\quad X\cap Y\neq \varnothing . \end{equation*}

$X\between Y$

holds, then we say (as standard) that

$X\between Y$

holds, then we say (as standard) that

$X$

and

$X$

and

$Y$

intersect

.

$Y$

intersect

.

-

(2) We may chain the

$\between$

notation, writing, for example,

$\between$

notation, writing, for example,

\begin{equation*} X\between Y\between Z \quad \text{for}\quad X\between Y\ \land \ Y\between Z \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} X\between Y\between Z \quad \text{for}\quad X\between Y\ \land \ Y\between Z \end{equation*}

-

(3) We may write

for

for

$\neg (X\between Y)$

, thus

$\neg (X\between Y)$

, thus

when

when

$X\cap Y=\varnothing$

.

$X\cap Y=\varnothing$

.

Remark 3.1.2. Note on design in Notation 3.1.1: It is uncontroversial that if

![]() $X\neq \varnothing$

and

$X\neq \varnothing$

and

![]() $Y\neq \varnothing$

, then

$Y\neq \varnothing$

, then

![]() $X\between Y$

should hold precisely when

$X\between Y$

should hold precisely when

![]() $X\cap Y\neq \varnothing$

– but there is an edge case! What truth value should

$X\cap Y\neq \varnothing$

– but there is an edge case! What truth value should

![]() $X\between Y$

return when

$X\between Y$

return when

![]() $X$

or

$X$

or

![]() $Y$

is empty?

$Y$

is empty?

-

(1) It might be nice if

$X\subseteq Y$

would imply

$X\subseteq Y$

would imply

$X\between Y$

. This argues for setting

$X\between Y$

. This argues for setting \begin{equation*} (X=\varnothing \lor Y=\varnothing )\Longrightarrow X\between Y . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} (X=\varnothing \lor Y=\varnothing )\Longrightarrow X\between Y . \end{equation*}

-

(2) It might be nice if

$X\between Y$

were monotone on both arguments (i.e., if

$X\between Y$

were monotone on both arguments (i.e., if

$X\between Y$

and

$X\between Y$

and

$X\subseteq X'$

, then

$X\subseteq X'$

, then

$X'\between Y$

). This argues for setting

$X'\between Y$

). This argues for setting

-

(3) It might be nice if

$X\between X$

always – after all, should a set not intersect itself? – and this argues for settingeven if we also set

$X\between X$

always – after all, should a set not intersect itself? – and this argues for settingeven if we also set \begin{equation*} \varnothing \between \varnothing , \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \varnothing \between \varnothing , \end{equation*}

for nonempty

for nonempty

$Y$

.

$Y$

.

All three choices are defensible, and they are consistent with the following nice property:

We choose the second – if

![]() $X$

or

$X$

or

![]() $Y$

is empty then

$Y$

is empty then  – because it gives the simplest definition that

– because it gives the simplest definition that

![]() $X\between Y$

precisely when

$X\between Y$

precisely when

![]() $X\cap Y\neq \varnothing$

.

$X\cap Y\neq \varnothing$

.

We list some elementary properties of

![]() $\between$

from Notation 3.1.1(1):

$\between$

from Notation 3.1.1(1):

Lemma 3.1.3.

-

(1)

$X\between X$

if and only if

$X\between X$

if and only if

$X\neq \varnothing$

.

$X\neq \varnothing$

. -

(2)

$X\between Y$

if and only if

$X\between Y$

if and only if

$Y\between X$

.

$Y\between X$

. -

(3)

$X\between (Y\cup Z)$

if and only if

$X\between (Y\cup Z)$

if and only if

$(X\between Y) \lor (X\between Z)$

.

$(X\between Y) \lor (X\between Z)$

. -

(4) If

$X\subseteq X'$

and

$X\subseteq X'$

and

$X\neq \varnothing$

then

$X\neq \varnothing$

then

$X\between X'$

.

$X\between X'$

. -

(5) Suppose

$X\between Y$

. Then

$X\between Y$

. Then

$X\subseteq X'$

implies

$X\subseteq X'$

implies

$X'\between Y$

, and

$X'\between Y$

, and

$Y\subseteq Y'$

implies

$Y\subseteq Y'$

implies

$X\between Y'$

.

$X\between Y'$

. -

(6) If

$X\between Y$

then

$X\between Y$

then

$X\neq \varnothing$

and

$X\neq \varnothing$

and

$Y\neq \varnothing$

.

$Y\neq \varnothing$

.

Proof. By facts of set intersection.

3.2 Transitive open sets and value assignments

Remark 3.2.1 (Taking stock of topens). Transitive sets are of interest because values of continuous functions are strongly correlated on them. This is Theorem 3.2.3, especially part 2 of Theorem 3.2.3.

A transitive open set – a topen – is even more important, because an open set corresponds in our semitopological model to a quorum (a collection of participants that can make progress), so a transitive open set is a collection of participants that can make progress and are guaranteed to do so in consensus, where algorithms succeed.

For this and other reasons, we very much care about finding topens and understanding when points are associated with topen sets (e.g., by having topen neighbourhoods). As we develop the maths, this will then lead us on to consider various regularity properties (Definition 4.1.4). But first, we start with transitive sets and topens:

Definition 3.2.2. Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology. Suppose

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology. Suppose

![]() $T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

is any set of points.

$T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

is any set of points.

-

(1) Call

$T$

transitive when

$T$

transitive when \begin{equation*} \forall O,O'{\in }\mathsf{Open}. O\between T \between O' \Longrightarrow O\between O'. \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \forall O,O'{\in }\mathsf{Open}. O\between T \between O' \Longrightarrow O\between O'. \end{equation*}

-

(2) Call

$T$

topen when

$T$

topen when

$T$

is nonempty transitive and open.Footnote

10

$T$

is nonempty transitive and open.Footnote

10

We may write

\begin{equation*} \mathsf{Topen}=\{ T\in \mathsf{Open}_{\neq \varnothing } \mid T\text{ is transitive}\} . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \mathsf{Topen}=\{ T\in \mathsf{Open}_{\neq \varnothing } \mid T\text{ is transitive}\} . \end{equation*}

-

(3) Call

$S$

a maximal topen when

$S$

a maximal topen when

$S$

is a topen that is not a subset of any strictly larger topen.Footnote

11

$S$

is a topen that is not a subset of any strictly larger topen.Footnote

11

Theorem3.2.3 clarifies why transitivity is interesting: continuous value assignments are constant – if we think of points as participants, ‘constant function’ here means ‘in agreement’ – across transitive sets.

Theorem 3.2.3. Suppose that:

-

•

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology.

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology.

-

•

$\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values (a nonempty set with the discrete semitopology; see Definition 2.1.3(1)).

$\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values (a nonempty set with the discrete semitopology; see Definition 2.1.3(1)).

-

•

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

is a value assignment (Definition 2.1.3(2)).

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

is a value assignment (Definition 2.1.3(2)).

-

•

$T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

is a transitive set (Definition 3.2.2) – in particular this will hold if

$T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

is a transitive set (Definition 3.2.2) – in particular this will hold if

$T$

is topen – and

$T$

is topen – and

$p,p'\in T$

.

$p,p'\in T$

.

Then:

-

(1) If

$f$

is continuous at

$f$

is continuous at

$p$

and

$p$

and

$p'$

then

$p'$

then

$f(p)=f(p')$

.

$f(p)=f(p')$

. -

(2) As a corollary, if

$f$

is continuous on

$f$

is continuous on

$T$

, then

$T$

, then

$f$

is constant on

$f$

is constant on

$T$

.

$T$

.

In words we can say:

Continuous value assignments are constant across transitive sets.

Proof.

Part 2 follows from part 1 since if

![]() $f(p)=f(p')$

for any

$f(p)=f(p')$

for any

![]() $p,p'\in T$

, then by definition

$p,p'\in T$

, then by definition

![]() $f$

is constant on

$f$

is constant on

![]() $T$

. So we now just need to prove part 1 of this result.

$T$

. So we now just need to prove part 1 of this result.

Consider

![]() $p,p'\in T$

. By continuity on

$p,p'\in T$

. By continuity on

![]() $T$

, there exist open neighbourhoods

$T$

, there exist open neighbourhoods

![]() $p\in O\subseteq f^{\text{-}1}(f(p))$

and

$p\in O\subseteq f^{\text{-}1}(f(p))$

and

![]() $p'\in O'\subseteq f^{\text{-}1}(f(p'))$

. By construction

$p'\in O'\subseteq f^{\text{-}1}(f(p'))$

. By construction

![]() $O\between T \between O'$

(because

$O\between T \between O'$

(because

![]() $p\in O\cap T$

and

$p\in O\cap T$

and

![]() $p'\in T\cap O'$

). By transitivity of

$p'\in T\cap O'$

). By transitivity of

![]() $T$

, it follows that

$T$

, it follows that

![]() $O\between O'$

. Thus, there exists

$O\between O'$

. Thus, there exists

![]() $p''\in O\cap O'$

, and by construction

$p''\in O\cap O'$

, and by construction

![]() $f(p) = f(p'') = f(p')$

.

$f(p) = f(p'') = f(p')$

.

Corollary 3.2.4 is an easy and useful consequence of Theorem3.2.3:

Corollary 3.2.4. Suppose that:

-

•

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology.

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology.

-

•

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

is a value assignment to some set of values

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

is a value assignment to some set of values

$\mathsf{Val}$

(Definition 2.1.3).

$\mathsf{Val}$

(Definition 2.1.3).

-

•

$f$

is continuous on topen sets

$f$

is continuous on topen sets

$T, T'\in \mathsf{Topen}$

.

$T, T'\in \mathsf{Topen}$

.

Then

Proof.

By Theorem3.2.3,

![]() $f$

is constant on

$f$

is constant on

![]() $T$

and

$T$

and

![]() $T'$

. We assumed that

$T'$

. We assumed that

![]() $T$

and

$T$

and

![]() $T'$

intersect, and the result follows.

$T'$

intersect, and the result follows.

A converse to Theorem3.2.3 also holds:

Proposition 3.2.5. Suppose that:

-

•

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology.

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology.

-

•

$\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values with at least two elements (to exclude a degenerate case where no functions exist, or they exist but there is only one because there is only one value to map to).

$\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values with at least two elements (to exclude a degenerate case where no functions exist, or they exist but there is only one because there is only one value to map to).

-

•

$T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

is any set.

$T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

is any set.

Then

-

• if for every

$p,p'\in T$

and every value assignment

$p,p'\in T$

and every value assignment

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

,

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

,

$f$

continuous at

$f$

continuous at

$p$

and

$p$

and

$p'$

implies

$p'$

implies

$f(p)=f(p')$

,

$f(p)=f(p')$

, -

• then

$T$

is transitive.

$T$

is transitive.

Proof.

We prove the contrapositive. Suppose

![]() $T$

is not transitive, so there exist

$T$

is not transitive, so there exist

![]() $O,O'\in \mathsf{Open}$

such that

$O,O'\in \mathsf{Open}$

such that

![]() $O\between T\between O'$

and yet

$O\between T\between O'$

and yet

![]() $O\cap O'=\varnothing$

. We choose two distinct values

$O\cap O'=\varnothing$

. We choose two distinct values

![]() $v\neq v'\in \mathsf{Val}$

and define

$v\neq v'\in \mathsf{Val}$

and define

![]() $f$

to map any point in

$f$

to map any point in

![]() $O$

to

$O$

to

![]() $v$

and any point in

$v$

and any point in

![]() $\mathsf{P}\setminus O$

to

$\mathsf{P}\setminus O$

to

![]() $v'$

.

$v'$

.

Choose some

![]() $p\in O$

and

$p\in O$

and

![]() $p'\in O'$

. It does not matter which, and some such

$p'\in O'$

. It does not matter which, and some such

![]() $p$

and

$p$

and

![]() $p'$

exist, because

$p'$

exist, because

![]() $O$

and

$O$

and

![]() $O'$

are nonempty by Lemma 3.1.3(6), since

$O'$

are nonempty by Lemma 3.1.3(6), since

![]() $O\between T$

and

$O\between T$

and

![]() $O'\between T$

).

$O'\between T$

).

We note that

![]() $f(p)=v$

and

$f(p)=v$

and

![]() $f(p')=v'$

and

$f(p')=v'$

and

![]() $f$

is continuous at

$f$

is continuous at

![]() $p\in O$

and

$p\in O$

and

![]() $p'\in O'\subseteq \mathsf{P}\setminus O$

, yet

$p'\in O'\subseteq \mathsf{P}\setminus O$

, yet

![]() $f(p)\neq f(p')$

.

$f(p)\neq f(p')$

.

We can sum up what Theorem3.2.3 and Proposition 3.2.5 mean as follows:

Remark 3.2.6. Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology, and

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology, and

![]() $\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values with at least two elements. Say that a value assignment

$\mathsf{Val}$

is a semitopology of values with at least two elements. Say that a value assignment

![]() $f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

splits a set

$f:\mathsf{P}\to \mathsf{Val}$

splits a set

![]() $T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

when there exist

$T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

when there exist

![]() $p,p'\in T$

such that

$p,p'\in T$

such that

![]() $f$

is continuous at

$f$

is continuous at

![]() $p$

and

$p$

and

![]() $p'$

and

$p'$

and

![]() $f(p)\neq f(p')$

. Then Theorem 3.2.3 and Proposition 3.2.5 together say in words that:

$f(p)\neq f(p')$

. Then Theorem 3.2.3 and Proposition 3.2.5 together say in words that:

![]() $T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

is transitive if and only if it cannot be split by a value assignment that is continuous on

$T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

is transitive if and only if it cannot be split by a value assignment that is continuous on

![]() $T$

.

$T$

.

Intuitively, transitive sets characterise areas of guaranteed agreement.

3.3 Examples and discussion of transitive sets and topens

We may routinely order sets by subset inclusion, including open sets, topens, closed sets, and so on, and we may talk about maximal, minimal, greatest and least elements. We include the (standard) definition for reference:

Notation 3.3.1.

Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\leq )$

is a poset. Then:

$(\mathsf{P},\leq )$

is a poset. Then:

-

(1) Call

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

maximal

when

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

maximal

when

$\forall p'.p{\leq }p'\Longrightarrow p'=p$

and

minimal

when

$\forall p'.p{\leq }p'\Longrightarrow p'=p$

and

minimal

when

$\forall p'.p'{\leq }p\Longrightarrow p'=p$

.

$\forall p'.p'{\leq }p\Longrightarrow p'=p$

. -

(2) Call

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

greatest

when

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

greatest

when

$\forall p.p'\leq p$

and

least

when

$\forall p.p'\leq p$

and

least

when

$\forall p'.p\leq p'$

.

$\forall p'.p\leq p'$

.

Example 3.3.2 (Examples of transitive sets).

-

(1)

$\{p\}$

is transitive, for any single point

$\{p\}$

is transitive, for any single point

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

.

$p\in \mathsf{P}$

.

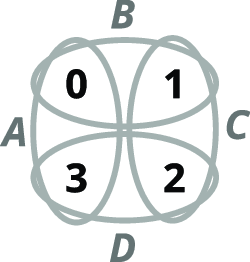

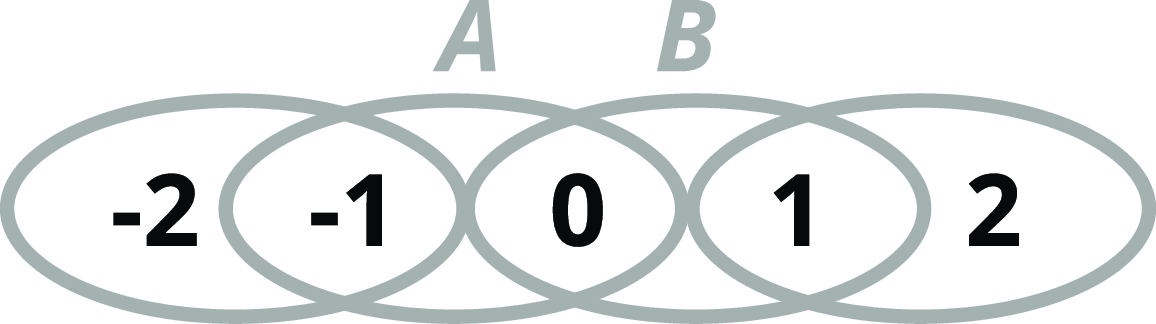

Figure 2. Examples of topens (Example 3.3.3).

-

(2) The empty set

$\varnothing$

is (trivially) transitive. It is not topen because we insist in Definition 3.2.2(2) that topens are nonempty.

$\varnothing$

is (trivially) transitive. It is not topen because we insist in Definition 3.2.2(2) that topens are nonempty. -

(3) Call a set

$P\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

topologically indistinguishable when (using Notation 3.1.1) for every open set

$P\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

topologically indistinguishable when (using Notation 3.1.1) for every open set

$O$

,It is easy to check that if

$O$

,It is easy to check that if \begin{equation*} P\between O\Longleftrightarrow P\subseteq O . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} P\between O\Longleftrightarrow P\subseteq O . \end{equation*}

$P$

is topologically indistinguishable, then it is transitive.

$P$

is topologically indistinguishable, then it is transitive.

Example 3.3.3 (Examples of topens).

-

(1) Take

$\mathsf{P}=\{0, 1, 2\}$

, with open sets

$\mathsf{P}=\{0, 1, 2\}$

, with open sets

$\varnothing$

,

$\varnothing$

,

$\mathsf{P}$

,

$\mathsf{P}$

,

$\{0\}$

and

$\{0\}$

and

$\{2\}$

. This has two maximal topens

$\{2\}$

. This has two maximal topens

$\{0\}$

and

$\{0\}$

and

$\{2\}$

as illustrated in Figure 2 (top-left diagram).

$\{2\}$

as illustrated in Figure 2 (top-left diagram). -

(2) Take

$\mathsf{P}=\{0, 1, 2\}$

, with open sets

$\mathsf{P}=\{0, 1, 2\}$

, with open sets

$\varnothing$

,

$\varnothing$

,

$\mathsf{P}$

,

$\mathsf{P}$

,

$\{0\}$

,

$\{0\}$

,

$\{0, 1\}$

,

$\{0, 1\}$

,

$\{2\}$

,

$\{2\}$

,

$\{1,2\}$

and

$\{1,2\}$

and

$\{0,2\}$

. This has two maximal topens

$\{0,2\}$

. This has two maximal topens

$\{0\}$

and

$\{0\}$

and

$\{2\}$

, as illustrated in Figure 2 (top-right diagram).

$\{2\}$

, as illustrated in Figure 2 (top-right diagram). -

(3) Take

$\mathsf{P}=\{0,1,2,3,4\}$

, with open sets generated by

$\mathsf{P}=\{0,1,2,3,4\}$

, with open sets generated by

$\{0, 1\}$

,

$\{0, 1\}$

,

$\{1\}$

,

$\{1\}$

,

$\{3\}$

and

$\{3\}$

and

$\{3,4\}$

. This has two maximal topens

$\{3,4\}$

. This has two maximal topens

$\{0,1\}$

and

$\{0,1\}$

and

$\{3,4\}$

, as illustrated in Figure 2 (lower-left diagram).

$\{3,4\}$

, as illustrated in Figure 2 (lower-left diagram). -

(4) Take

$\mathsf{P}=\{0,1,2,\ast \}$

, with open sets generated by

$\mathsf{P}=\{0,1,2,\ast \}$

, with open sets generated by

$\{0\}$

,

$\{0\}$

,

$\{1\}$

,

$\{1\}$

,

$\{2\}$

,

$\{2\}$

,

$\{0, 1,\ast \}$

and

$\{0, 1,\ast \}$

and

$\{1,2,\ast \}$

. This has three maximal topens

$\{1,2,\ast \}$

. This has three maximal topens

$\{0\}$

,

$\{0\}$

,

$\{1\}$

and

$\{1\}$

and

$\{2\}$

, as illustrated in Figure 2 (lower-right diagram).

$\{2\}$

, as illustrated in Figure 2 (lower-right diagram). -

(5) Take the all-but-one semitopology from Example 2.1.4(5c) on

$\mathbb N$

: so

$\mathbb N$

: so

$\mathsf{P}=\mathbb N$

with opens

$\mathsf{P}=\mathbb N$

with opens

$\varnothing$

,

$\varnothing$

,

$\mathbb N$

and

$\mathbb N$

and

$\mathbb N\setminus \{x\}$

for every

$\mathbb N\setminus \{x\}$

for every

$x\in \mathbb N$

. This has a single maximal topen

$x\in \mathbb N$

. This has a single maximal topen

$\mathbb N$

.

$\mathbb N$

. -

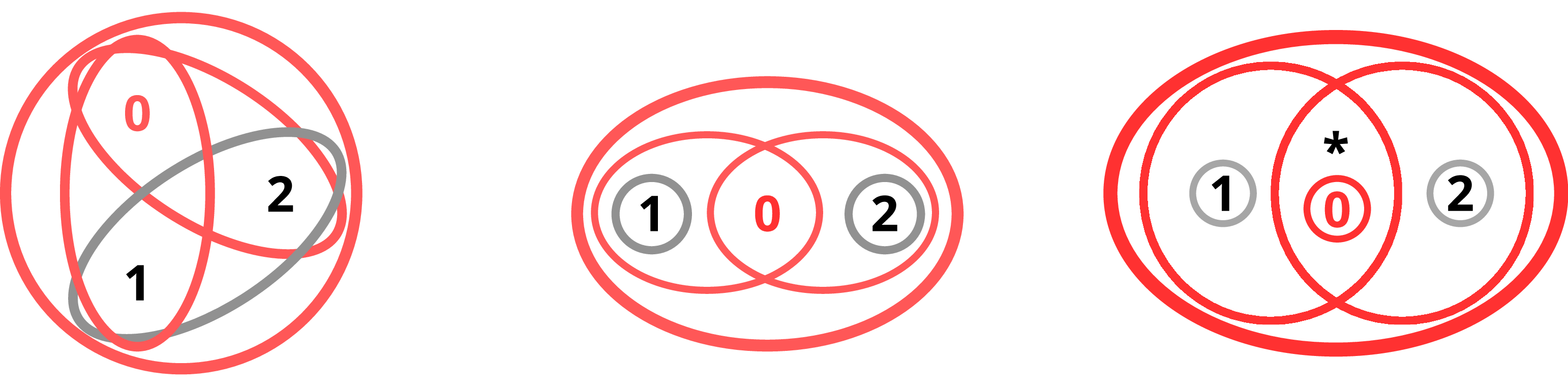

(6) The semitopology in Figure 3 has no topen sets at all (

$\varnothing$

is transitive and open, but by definition in Definition 3.2.2(2) topens have to be nonempty).

$\varnothing$

is transitive and open, but by definition in Definition 3.2.2(2) topens have to be nonempty).

Here and elsewhere, we might omit open sets that are unions of open sets that are illustrated. For example, we explicitly draw the universal open set in the left-hand diagrams above, but not in the right-hand and bottom diagrams above. Meaning is clear, and we get cleaner diagrams.

3.4 Closure properties of transitive sets and topens

Remark 3.4.1. Transitive sets have some nice closure properties which we treat in this subsection – here, we mean ‘closure’ in the sense of “the set of transitive sets is closed under various operations”, and not in the topological sense of ‘closed sets’. Topens – nonempty transitive open sets – have even better closure properties, which emanate from the requirement in Lemma 3.4.3 that at least one of the transitive sets

![]() $T$

or

$T$

or

![]() $T'$

is open.

$T'$

is open.

Lemma 3.4.2.

Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

![]() $T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

. Then:

$T\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

. Then:

-

(1) If

$T$

is transitive and

$T$

is transitive and

$T'\subseteq T$

, then

$T'\subseteq T$

, then

$T'$

is transitive.

$T'$

is transitive.

-

(2) If

$T$

is topen and

$T$

is topen and

$\varnothing \neq T'\subseteq T$

is nonempty and open, then

$\varnothing \neq T'\subseteq T$

is nonempty and open, then

$T'$

is topen.

$T'$

is topen.

Proof.

-

(1) By Definition 3.2.2, it suffices to consider open sets

$O$

and

$O$

and

$O'$

such that

$O'$

such that

$O\between T'\between O'$

and prove that

$O\between T'\between O'$

and prove that

$O\between O'$

. But this is simple: by Lemma 3.1.3(5)

$O\between O'$

. But this is simple: by Lemma 3.1.3(5)

$O\between T\between O'$

, so

$O\between T\between O'$

, so

$O\between O'$

follows by transitivity of

$O\between O'$

follows by transitivity of

$T$

.

$T$

. -

(2) Direct from part 1 of this result and Definition 3.2.2(2).

Lemma 3.4.3.

Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

![]() $T,T'\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

are transitive, and suppose that at least one of

$T,T'\subseteq \mathsf{P}$

are transitive, and suppose that at least one of

![]() $T$

and

$T$

and

![]() $T'$

is open. Then

$T'$

is open. Then

Proof.

We simplify using Definition 3.2.2 and our assumption that one of

![]() $T$

and

$T$

and

![]() $T'$

is open. We consider the case that

$T'$

is open. We consider the case that

![]() $T'$

is open:

$T'$

is open:

The argument for when

![]() $T$

is open is precisely similar.

$T$

is open is precisely similar.

Proposition 3.4.4.

Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology. Then if

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology. Then if

![]() $\mathscr T$

is a set of pairwise intersecting topens, then

$\mathscr T$

is a set of pairwise intersecting topens, then

![]() $\bigcup \mathscr T$

is topen.

$\bigcup \mathscr T$

is topen.

Proof.

![]() $\bigcup \mathscr T$

is open by Definition 1.2.2(2). Also, if

$\bigcup \mathscr T$

is open by Definition 1.2.2(2). Also, if

![]() $O\between \bigcup \mathscr T\ \between O'$

then there exist

$O\between \bigcup \mathscr T\ \between O'$

then there exist

![]() $T,T'\in \mathscr T$

such that

$T,T'\in \mathscr T$

such that

![]() $O\between T$

and

$O\between T$

and

![]() $T'\between O'$

. We assumed

$T'\between O'$

. We assumed

![]() $T\between T'$

, so by Lemma 3.4.3 (since

$T\between T'$

, so by Lemma 3.4.3 (since

![]() $T$

and

$T$

and

![]() $T'$

are open) we have

$T'$

are open) we have

![]() $O\between O'$

as required.

$O\between O'$

as required.

Corollary 3.4.5.

Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology. Then every topen

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology. Then every topen

![]() $T$

is contained in a unique maximal topen.

$T$

is contained in a unique maximal topen.

Proof.

Consider

![]() $\mathscr T\ = \{T\cup T' \mid T'\text{ topen}\land T\between T'\}$

. By Proposition 3.4.4, this is a set of topens. By construction, they all contain

$\mathscr T\ = \{T\cup T' \mid T'\text{ topen}\land T\between T'\}$

. By Proposition 3.4.4, this is a set of topens. By construction, they all contain

![]() $T$

, so by our assumption that

$T$

, so by our assumption that

![]() $T\neq \varnothing$

, they pairwise intersect, and by Proposition 3.4.4 again

$T\neq \varnothing$

, they pairwise intersect, and by Proposition 3.4.4 again

![]() $\bigcup \mathscr T$

is topen. It is easy to check that this is the unique maximal topen that contains

$\bigcup \mathscr T$

is topen. It is easy to check that this is the unique maximal topen that contains

![]() $T$

.

$T$

.

3.5 Intertwined points

3.5.1 The basic definition

Definition 3.5.1. Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and

![]() $p,p'\in \mathsf{P}$

.

$p,p'\in \mathsf{P}$

.

-

(1) Call

$p$

and

$p$

and

$p'$

intertwined when

$p'$

intertwined when

$\{p,p'\}$

is transitive. Unpacking Definition 3.2.2, this means:By a mild abuse of notation, write

$\{p,p'\}$

is transitive. Unpacking Definition 3.2.2, this means:By a mild abuse of notation, write \begin{equation*} \forall O,O'{\in }\mathsf{Open}. (p\in O\land p'\in O') \Longrightarrow O\between O' . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} \forall O,O'{\in }\mathsf{Open}. (p\in O\land p'\in O') \Longrightarrow O\between O' . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} p\mathrel {\between } p' \quad \text{when}\quad \text{$p$ and $p'$ are intertwined}. \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} p\mathrel {\between } p' \quad \text{when}\quad \text{$p$ and $p'$ are intertwined}. \end{equation*}

-

(2) Define

$p_{\between }$

(read ‘intertwined of

$p_{\between }$

(read ‘intertwined of

$p$

’) to be the set of points intertwined with

$p$

’) to be the set of points intertwined with

$p$

. In symbols:

$p$

. In symbols: \begin{equation*} p_{\between }=\{p'\in \mathsf{P} \mid p\mathrel {\between } p'\} . \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*} p_{\between }=\{p'\in \mathsf{P} \mid p\mathrel {\between } p'\} . \end{equation*}

Example 3.5.2. We return to the examples in Example 3.3.3. There we note that:

-

(1)

$1_{\between }=\{0,1,2\}$

and

$1_{\between }=\{0,1,2\}$

and

$0_{\between }=\{0,1\}$

and

$0_{\between }=\{0,1\}$

and

$2_{\between }=\{1,2\}$

.

$2_{\between }=\{1,2\}$

. -

(2)

$1_{\between }=\{1\}$

and

$1_{\between }=\{1\}$

and

$0_{\between }=\{0\}$

and

$0_{\between }=\{0\}$

and

$2_{\between }=\{2\}$

.

$2_{\between }=\{2\}$

. -

(3)

$x_{\between }=\mathsf{P}$

for every

$x_{\between }=\mathsf{P}$

for every

$x$

.

$x$

.

Lemma 3.5.3.

Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology. Then the ‘is intertwined’ relation

$(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology. Then the ‘is intertwined’ relation

![]() $\between$

is not necessarily transitive. That is,

$\between$

is not necessarily transitive. That is,

![]() $p\mathrel {\between } p'\mathrel {\between } p''$

does not necessarily imply

$p\mathrel {\between } p'\mathrel {\between } p''$

does not necessarily imply

![]() $p\mathrel {\between } p''$

.

$p\mathrel {\between } p''$

.

Proof.

It suffices to provide a counterexample. The semitopology from Example 3.3.3(1) (illustrated in Figure 2, top-left diagram) will do. So take

![]() $\mathsf{P}=\{0,1,2\}$

and

$\mathsf{P}=\{0,1,2\}$

and

![]() $\mathsf{Open}=\{\varnothing ,\mathsf{P},\{0\},\{2\}\}$

. Then

$\mathsf{Open}=\{\varnothing ,\mathsf{P},\{0\},\{2\}\}$

. Then

3.5.2 Pointwise characterisation of transitive sets

Lemma 3.5.4.

Suppose

![]() $(\mathsf{P},\mathsf{Open})$

is a semitopology and