1 Introduction

Multiple-choice items have been a mainstay of educational and psychological assessments for nearly a century (Gierl et al., Reference Gierl, Bulut, Guo and Zhang2017). While single-answer multiple-choice (SAMC) items gained early popularity due to their simplicity and efficiency, they possess inherent limitations in assessing partial knowledge. The all-or-nothing response format of SAMC items is not conducive to partial credit (Bush, Reference Bush2001; Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1941), restricting researchers’ insights into a student’s reasoning. It is difficult to determine whether respondents have partially narrowed down the options or fundamentally lack understanding (Mobalegh & Barati, Reference Mobalegh and Barati2012; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Anderson, Heidemann, Merrill, Merritt, Richmond and Urban-Lurain2012).

To overcome these limitations, innovative item formats like multiple response (MR) items have been developed to capture more nuanced data on respondents’ knowledge. MR items allow respondents to select multiple options, providing richer, more detailed data (Betts et al., Reference Betts, Muntean, Kim and Kao2022; Duncan & Milton, Reference Duncan and Milton1978). The raw response data collected from MR items, known as response combinations (RCs), are also referred to as response patterns or multiple responses (Betts et al., Reference Betts, Muntean, Kim and Kao2022; Muntean & Betts, Reference Muntean and Betts2015). These RCs are defined as the data generated from various combinations of the selected options. They provide a more accurate differentiation of respondents’ latent abilities by capturing partial knowledge (Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Moss and Khampalikit1984; Pomplun & Omar, Reference Pomplun and Omar1997). These advantages have led to the widespread incorporation of MR items into various assessments, including the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), International English Language Testing System (IELTS), and Graduate Record Examinations (GRE) (Emmerich et al., Reference Emmerich, Enright, Rock and Tucker1991; Rustanto et al., Reference Rustanto, Suciati and Prayitno2023; Suvorov & Li, Reference Suvorov and Li2023).

Despite these benefits, MR items present several analytical challenges. Current analysis approaches based on scoring methods often overlook subtle ability differences indicated by distinct RCs when they lead to identical scores, and they also disregard the information provided by different options. Existing Item Response Theory (IRT) models often struggle to handle the complexity of MR data. These IRT models typically rely on modeling compressed scores (see Section 3), which can lead to a potential loss of valuable information. Furthermore, the diverse range of MR item formats (see Section 2), each with its unique sets of RCs, complicates straightforward comparison and analysis (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Raupach, Wiegand, Herrmann and Kanzow2022). Finally, local dependencies among options are a common but frequently overlooked feature of MR items (Albanese & Sabers, Reference Albanese and Sabers1988; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Holzer, Kopp and Fischer2011; Frisbie & Druva, Reference Frisbie and Druva1986; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Eaton, White Brahmia, Olsho, Zimmerman and Boudreaux2022). Particularly, neglecting such local dependence may result in biased estimates of both item parameters and respondent abilities, as well as an overestimation of test reliability (Pomplun & Omar, Reference Pomplun and Omar1997; Sireci et al., Reference Sireci, Thissen and Wainer1991; DeMars, Reference DeMars2006).

This study introduces a novel psychometric model framework designed to leverage the richness of RC data in MR items. The model overcomes the restrictive nature of traditional scoring methods and the limitations of existing IRT approaches by directly modeling RC data, accounting for local dependencies within items, and accommodating diverse MR item formats. This approach aims to provide more accurate estimates of respondents’ latent abilities and enable a more comprehensive analysis of item characteristics.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces three common MR item formats and highlights their similarities and differences. Section 3 outlines three scoring methods for MR items and illustrates the impact of different MR item types and scoring methods on the collected data and resulting scores using an example. Section 4 proposes a novel Multiple Response Model (MRM) framework and describes its Bayesian parameter estimation. An empirical study is presented in Section 5, where we administered an MR test based on middle school physics concepts related to light phenomena, demonstrating the advantages of the proposed method in analyzing MR items. Section 6 presents four simulation studies designed to evaluate the parameter estimation performance and robustness of the proposed and traditional models across a wide range of test scenarios. Finally, Section 7 concludes with remarks and a discussion of limitations and future research directions. Important abbreviations employed in this paper are listed in Appendix Table A1.

2 Types of multiple response items

Based on their instructions and the resultant RCs, MR items can be classified into three primary types: multiple true-false (MTF) items, conventional multiple-select (CMS) items, and select-N items. Each MR item encompasses O options, and contingent upon the item type, these options can be merged to generate X possible RCs.

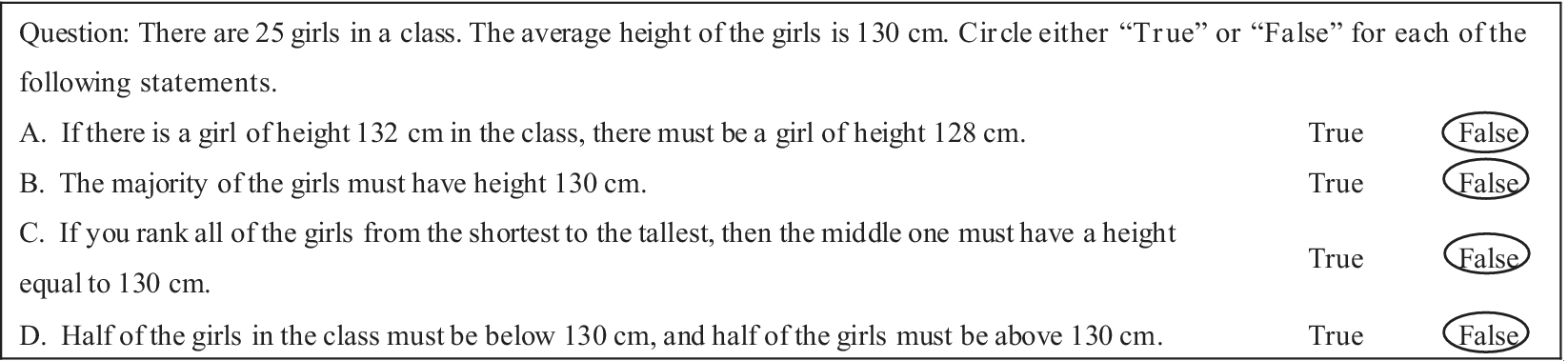

Multiple true-false items: MTF items present multiple options within a single item, each requiring a true or false judgment (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1939). Typically containing four to six options, MTF items allow any number of correct options. Figure 1 shows an MTF item from the PISA 2012 mathematics test sample (OECD, 2013), which includes four options. Respondents mark each option as either true or false, resulting in

![]() $X={2}^O=16$

possible RCs. The correct answer to this item is that all four options are false. MTF items allow for the possibility that all options are selected as incorrect. Hubbard et al. (Reference Hubbard, Potts and Couch2017) noted that MTF items require students to evaluate each option independently rather than simply recognizing a correct answer from a list, which can encourage deeper learning strategies akin to those promoted by free-response questions, making MTF items a valuable alternative to SAMC items.

$X={2}^O=16$

possible RCs. The correct answer to this item is that all four options are false. MTF items allow for the possibility that all options are selected as incorrect. Hubbard et al. (Reference Hubbard, Potts and Couch2017) noted that MTF items require students to evaluate each option independently rather than simply recognizing a correct answer from a list, which can encourage deeper learning strategies akin to those promoted by free-response questions, making MTF items a valuable alternative to SAMC items.

Figure 1 An MTF example item from the PISA 2012 mathematics assessment.

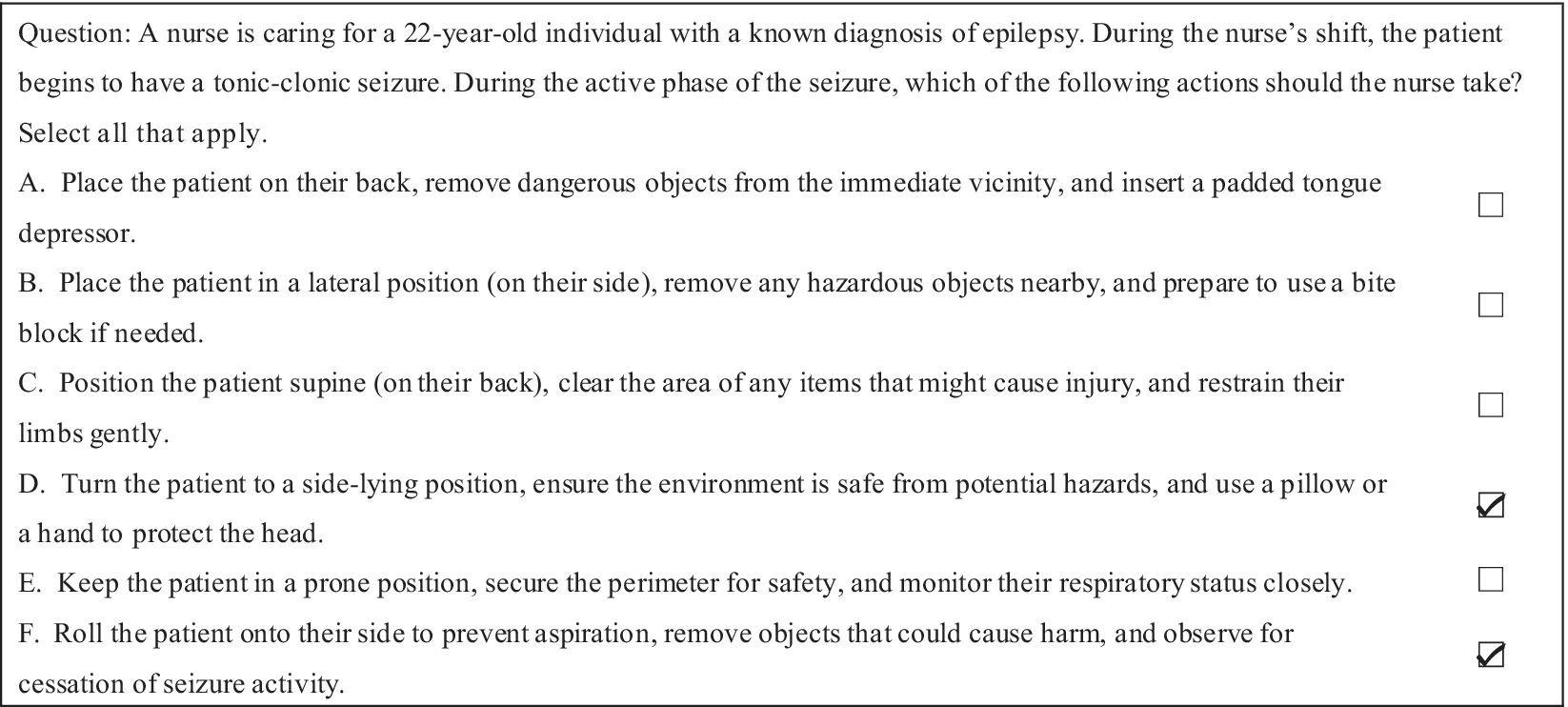

Conventional multiple-select items: CMS items, also referred to as select-all-that-apply items, require respondents to select all correct options while leaving incorrect ones unmarked, making them the most prevalent MR format (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Raupach, Wiegand, Herrmann and Kanzow2021). In contrast to MTF items, CMS items typically exclude the all-zero RC offering

![]() $X={2}^O-1$

possible RCs. For example, Figure 2 shows a National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN) practice sample item. This CMS item presenting six options requires respondents to identify only the correct options, resulting in

$X={2}^O-1$

possible RCs. For example, Figure 2 shows a National Council Licensure Examination for Registered Nurses (NCLEX-RN) practice sample item. This CMS item presenting six options requires respondents to identify only the correct options, resulting in

![]() ${2}^6-1=63$

possible RCs. CMS is structurally similar to SAMC, but the allowance of multiple selections expands the response space (Muckle et al., Reference Muckle, Becker and Wu2011), and it is less prone to “acquiescence bias” (the tendency to agree) than MTF items (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1941).

${2}^6-1=63$

possible RCs. CMS is structurally similar to SAMC, but the allowance of multiple selections expands the response space (Muckle et al., Reference Muckle, Becker and Wu2011), and it is less prone to “acquiescence bias” (the tendency to agree) than MTF items (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1941).

Figure 2 A CMS example item from the NCLEX-RN practice test.

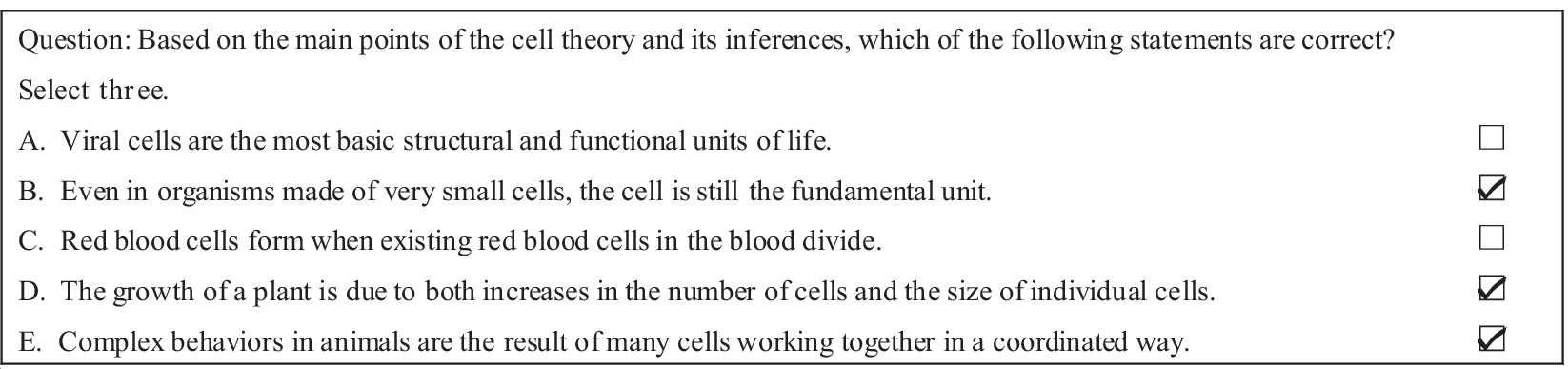

Select-N items: Also known as pick-N items, they are a variant of CMS items where respondents are informed of the exact number of correct options (

![]() $T$

) to select (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Holzer, Kopp and Fischer2011; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Raupach, Wiegand, Herrmann and Kanzow2022; Schmittlein, Reference Schmittlein1984). Figure 3 presents a select-N item of the 2024 Taiwan General Scholastic Ability Test (GSAT), with five options and three correct answers, and respondents must select precisely three options, yielding

$T$

) to select (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Holzer, Kopp and Fischer2011; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Raupach, Wiegand, Herrmann and Kanzow2022; Schmittlein, Reference Schmittlein1984). Figure 3 presents a select-N item of the 2024 Taiwan General Scholastic Ability Test (GSAT), with five options and three correct answers, and respondents must select precisely three options, yielding

![]() $X={C}_O^T={C}_5^3=10$

possible RCs. This structure simplifies the response process and helps lower the cognitive load on respondents as the number of options increases.

$X={C}_O^T={C}_5^3=10$

possible RCs. This structure simplifies the response process and helps lower the cognitive load on respondents as the number of options increases.

Figure 3 A Select-N example item from the GSAT 2024.

3 Scoring methods for multiple response items

MR items inherently generate significantly more RCs than SAMC items, which substantially increases the complexity of scoring. Consequently, researchers have identified over 40 distinct scoring methods for MR items (Kanzow et al., Reference Kanzow, Schmidt, Herrmann, Wassmann, Wiegand and Raupach2023; Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Raupach, Wiegand, Herrmann and Kanzow2021, Reference Schmidt, Raupach, Wiegand, Herrmann and Kanzow2022). These diverse methods primarily aim to compress RC data into either dichotomous or polytomous scores, which are then utilized for calculating overall test scores or estimating latent abilities. This article introduces three commonly used scoring methods that represent distinct points on a spectrum of scoring stringency: from strict, to moderate, to lenient.

Dichotomous scoring (DS): This method serves as a representative of the strictest scoring approach. It is the most demanding scoring method, where respondents receive full credit (typically designated as “1”) only if they answer all options correctly. If any option is incorrect, no points are awarded (Kolstad et al., Reference Kolstad, Briggs, Bryant and Kolstad1983; Lahner et al., Reference Lahner, Lörwald, Bauer, Nouns, Krebs, Guttormsen, Fischer and Huwendiek2018). This “all-or-nothing” approach completely disregards partial knowledge. As the number of options per item increases, the scoring becomes even more demanding. While simple to implement and commonly used, this method overlooks partial understanding and its stringency escalates with the increase in item options.

Ripkey scoring (RS): Representing a moderate, or middle-ground, approach, this scoring method is commonly applied to CMS and select-N items (Ripkey et al., Reference Ripkey, Case and Swanson1996). Each correct selection is awarded

![]() $\frac{1}{T}$

point, and incorrect selections are not penalized. However, a crucial caveat is that if the number of options selected exceeds the number of correct answers, the score for that item is zero. Unlike DS, RS allows for partial credit but introduces a penalty for over-selection, thus balancing the recognition of partial knowledge with a demand for response precision.

$\frac{1}{T}$

point, and incorrect selections are not penalized. However, a crucial caveat is that if the number of options selected exceeds the number of correct answers, the score for that item is zero. Unlike DS, RS allows for partial credit but introduces a penalty for over-selection, thus balancing the recognition of partial knowledge with a demand for response precision.

Partial scoring (PS): This method is representative of the most lenient approach and allows for the greatest number of distinct score levels. Also known as the MTF method or true/false testlet, PS is a commonly employed method for MTF and CMS items, awarding

![]() $\frac{1}{O}$

for each correct response. It is more forgiving than the other methods because it does not penalize incorrect answers. However, this leniency can incentivize random guessing, as respondents face no penalty for over-selecting options.

$\frac{1}{O}$

for each correct response. It is more forgiving than the other methods because it does not penalize incorrect answers. However, this leniency can incentivize random guessing, as respondents face no penalty for over-selecting options.

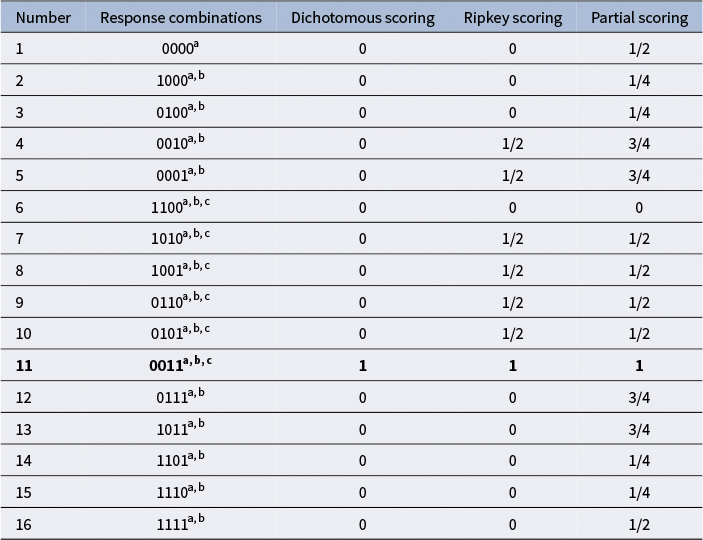

To illustrate the impact of item type and scoring method on scoring outcomes, consider a four-option MR item with options C and D as correct. Table 1 presents the valid RCs and their corresponding scores under DS, RS, and PS. For MTF, 1/0 denotes true/false; for CMS and select-N, it denotes selected/not selected. For example, the RC[0,0,0,1] means only option D is endorsed, which yields a score of 0 under DS, 1/2 under RS, and 3/4 under PS. After compression, this item produces two distinct score levels under DS, three under RS, and five under PS (with select-N typically yielding three under PS). These compressed scores can then be analyzed with standard dichotomous or polytomous IRT models.

Table 1 Response combinations and corresponding scores for MR items (four-option item).

Note: The total score of this item is assumed to be 1. Multiple true-false includes all response combinations, denoted as a; conventional multiple-select excludes the response combination where no options are selected, denoted as b; and select-N includes only response combinations where the number of selected options matches the number of correct options, denoted as c. The response combination shown in bold represents the fully correct response.

4 Multiple response model framework

For SAMC items, option-level IRT models, such as the nominal response model (NRM; Bock, Reference Bock, van der Linden and Hambleton1997) and the 3PL nested logit model (Suh & Bolt, Reference Suh and Bolt2010), have been established to provide superior performance over simple dichotomous scoring (Kim, Reference Kim2006; Thissen & Cai, Reference Thissen and Cai2010). In contrast, option-level methods for MR items remain underdeveloped. Traditional score-based approaches typically compress RCs into dichotomous or polychotomous scores, thereby discarding information on option-specific effects (Verbić, Reference Verbić2012). Furthermore, existing optimized modeling strategies face significant limitations. First, treating each option as an independent dichotomous item fails to account for local dependence within an item and proves unsuitable for constrained formats such as select-N (Dudley, Reference Dudley2006). Second, the approach of collapsing dependent options into unordered categories for analysis with the NRM requires prior identification of dependencies, obscures individual option effects, and leads to parameter proliferation as the number of options increases (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Eaton, White Brahmia, Olsho, Zimmerman and Boudreaux2022). To address these problems, this paper introduces the MRM and the MRM with Inter-option Local Dependencies (MRM-LD), specifically developed to directly estimate the probabilities of all possible RCs for an item. Without substantially increasing model complexity, these models both account for the unique contribution of each option to item responses and quantify the local dependencies among options within an item, thereby better preserving the information provided by RC data.

4.1 The multiple response model

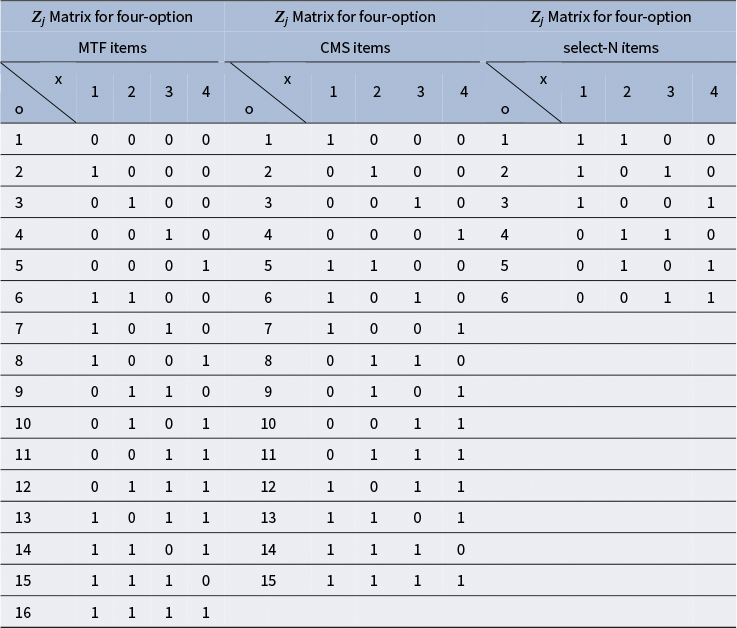

The MRM is grounded in the divide-by-total model family (Bolt et al., Reference Bolt, Cohen and Wollack2001; Thissen & Steinberg, Reference Thissen and Steinberg1986), which calculates the response probability of an RC based on the ratio of exponential terms, while being specifically tailored to accommodate RC data from various subtypes of MR items. To formalize the MRM, we define a design matrix

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

that represents all possible RCs for item

${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

that represents all possible RCs for item

![]() $j$

. Each element

$j$

. Each element

![]() ${Z}_{jxo}$

indicates the status of option

${Z}_{jxo}$

indicates the status of option

![]() $o$

in RC

$o$

in RC

![]() $x$

: for MTF items,

$x$

: for MTF items,

![]() ${Z}_{jxo}=1$

means option

${Z}_{jxo}=1$

means option

![]() $o$

is endorsed as true, and

$o$

is endorsed as true, and

![]() ${Z}_{jxo}=0$

as false; for CMS and select-N items,

${Z}_{jxo}=0$

as false; for CMS and select-N items,

![]() ${Z}_{jxo}=1$

means option

${Z}_{jxo}=1$

means option

![]() $o$

is selected, and

$o$

is selected, and

![]() ${Z}_{jxo}=0$

otherwise. The structure of

${Z}_{jxo}=0$

otherwise. The structure of

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

varies across item types due to differing constraints on permissible RCs. Table 2 presents the

${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

varies across item types due to differing constraints on permissible RCs. Table 2 presents the

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

matrices for four-option MTF, CMS, and select-N items with two correct options, which accommodate 16, 15, and 6 unique RCs, respectively. For example, RC[1,1,0,0] corresponds to endorsing the first two options as true in an MTF item (Table 2) or selecting the first two options in CMS and select-N items (Table 2).

${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

matrices for four-option MTF, CMS, and select-N items with two correct options, which accommodate 16, 15, and 6 unique RCs, respectively. For example, RC[1,1,0,0] corresponds to endorsing the first two options as true in an MTF item (Table 2) or selecting the first two options in CMS and select-N items (Table 2).

Table 2

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

Matrix for four-option MTF items,

${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

Matrix for four-option MTF items,

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

matrix for four-option CMS items, and

${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

matrix for four-option CMS items, and

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

Matrix for four-option MR items across different types.

${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

Matrix for four-option MR items across different types.

The MRM defines the probability of choosing a specific RC as the ratio of the attractiveness of that RC to the sum of the attractiveness values across all

![]() ${X}_j$

possible RCs. The probability that respondent

${X}_j$

possible RCs. The probability that respondent

![]() $i$

, with latent ability

$i$

, with latent ability

![]() ${\theta}_i$

, selects RC

${\theta}_i$

, selects RC

![]() $x$

for item

$x$

for item

![]() $j$

is given by the Response Combination Probability Function (RCPF):

$j$

is given by the Response Combination Probability Function (RCPF):

$$\begin{align}P\left({Y}_{ij}=x|{\theta}_i,{\boldsymbol{a}}_j,{\boldsymbol{d}}_j\right)=\frac{\mathit{\exp}\left({h}_{ij x}\right)}{\sum \limits_{m=1}^{X_j}\mathit{\exp}\left({h}_{ij m}\right)}\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}P\left({Y}_{ij}=x|{\theta}_i,{\boldsymbol{a}}_j,{\boldsymbol{d}}_j\right)=\frac{\mathit{\exp}\left({h}_{ij x}\right)}{\sum \limits_{m=1}^{X_j}\mathit{\exp}\left({h}_{ij m}\right)}\end{align}$$

where the term

![]() ${h}_{ijx}$

represents the total attractiveness of RC

${h}_{ijx}$

represents the total attractiveness of RC

![]() $x$

. This total attractiveness is modeled as a linear combination of the attractiveness of its constituent options:

$x$

. This total attractiveness is modeled as a linear combination of the attractiveness of its constituent options:

$$\begin{align}{h}_{ijx}=\sum \limits_{O=1}^{O_j}{Z}_{jxo}{h}_{ijo}^{\prime }\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{h}_{ijx}=\sum \limits_{O=1}^{O_j}{Z}_{jxo}{h}_{ijo}^{\prime }\end{align}$$

Here, the binary element

![]() ${Z}_{jxo}$

from the design matrix acts as a selector, determining which options contribute to the attractiveness of RC

${Z}_{jxo}$

from the design matrix acts as a selector, determining which options contribute to the attractiveness of RC

![]() $x$

. The attractiveness of each individual option,

$x$

. The attractiveness of each individual option,

![]() ${h}_{ijo}^{\prime }$

, is in turn modeled as a linear function of the respondent’s latent ability:

${h}_{ijo}^{\prime }$

, is in turn modeled as a linear function of the respondent’s latent ability:

By substituting Formulas (2) and (3) into Formula (1), the full RCPF expression for the MRM is obtained:

$$\begin{align}P\left({Y}_{ij}=x|{\theta}_i,{\boldsymbol{a}}_j,{\boldsymbol{d}}_j\right)=\frac{\mathit{\exp}\left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}{Z}_{jxo}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}\right)\right)}{\sum \limits_{m=1}^{X_j}\mathit{\exp}\left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}{Z}_{jmo}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}\right)\right)}\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}P\left({Y}_{ij}=x|{\theta}_i,{\boldsymbol{a}}_j,{\boldsymbol{d}}_j\right)=\frac{\mathit{\exp}\left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}{Z}_{jxo}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}\right)\right)}{\sum \limits_{m=1}^{X_j}\mathit{\exp}\left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}{Z}_{jmo}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}\right)\right)}\end{align}$$

In this model,

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

is the slope parameter for option

${a}_{jo}$

is the slope parameter for option

![]() $o$

of item

$o$

of item

![]() $j$

. A positive

$j$

. A positive

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

indicates a correct option, as its attractiveness increases with higher levels of

${a}_{jo}$

indicates a correct option, as its attractiveness increases with higher levels of

![]() ${\theta}_i$

. Conversely, a negative

${\theta}_i$

. Conversely, a negative

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

signifies an incorrect option, whose attractiveness decreases as

${a}_{jo}$

signifies an incorrect option, whose attractiveness decreases as

![]() ${\theta}_i$

increases. The parameter

${\theta}_i$

increases. The parameter

![]() ${d}_{jo}$

is the intercept parameter, representing the baseline attractiveness of option

${d}_{jo}$

is the intercept parameter, representing the baseline attractiveness of option

![]() $o$

when

$o$

when

![]() ${\theta}_i=0$

.

${\theta}_i=0$

.

A specific consideration for model identifiability arises with select-N items. In this format, every valid RC consists of exactly T selected options. This structural constraint leads to a potential identifiability issue because if a constant value were added to the attractiveness of every individual option, the total attractiveness of every valid RC would increase by an identical amount, leaving the choice probabilities unchanged. This makes a unique parameter solution impossible without further constraints. Therefore, to ensure model identifiability for select-N items, we impose the sum-to-zero constraints:

![]() $\sum _{o=1}^{O_j}{a}_{jo}=0\kern0.1em$

and

$\sum _{o=1}^{O_j}{a}_{jo}=0\kern0.1em$

and

![]() $\sum _{o=1}^{O_j}{d}_{jo}=0\kern0.1em$

. Consequently, one MTF or CMS item requires the estimation of

$\sum _{o=1}^{O_j}{d}_{jo}=0\kern0.1em$

. Consequently, one MTF or CMS item requires the estimation of

![]() ${O}_j$

slope and

${O}_j$

slope and

![]() ${O}_j$

intercept parameters (

${O}_j$

intercept parameters (

![]() $2{O}_j$

total), whereas select-N items require

$2{O}_j$

total), whereas select-N items require

![]() ${O}_j-1$

slope and

${O}_j-1$

slope and

![]() ${O}_j-1$

intercept parameters (

${O}_j-1$

intercept parameters (

![]() $2\left({O}_j-1\right)$

total).

$2\left({O}_j-1\right)$

total).

4.2 Incorporating local dependencies between options

In the MRM, the attractiveness of options is primarily determined by the respondent’s latent ability

![]() ${\theta}_i$

. However, beyond this latent ability, local dependencies can naturally exist among options within the same item in MR items (Pomplun & Omar, Reference Pomplun and Omar1997; Verbić, Reference Verbić2012). These dependencies are not related to the respondent’s ability but rather reflect specific interactions between the respondent and the item, arising from the common stimulus of the item stem and knowledge within the item (Beiting-Parrish et al., Reference Beiting-Parrish, Verkuilen, McCluskey, Everson, Wladis, Wiberg, Molenaar, González, Böckenholt and Kim2021). Motivated by the IRT testlet models (Li et al., Reference Li, Bolt and Fu2006, Reference Li, Li and Wang2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Bradlow and Wainer2002; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Han, Kim and Kao2022), we propose an extension to the MRM, termed the MRM-LD. The MRM-LD integrates these local dependencies by adding a term that represents person–item interactions into the definition of option attractiveness. This additional term accounts for specific abilities (Li, Reference Li2017) that may influence the respondent’s choice, separate from their general latent ability. The updated definition of attractiveness in the MRM-LD is shown in Formula (5), and the corresponding RCPF is provided in Formula (6):

${\theta}_i$

. However, beyond this latent ability, local dependencies can naturally exist among options within the same item in MR items (Pomplun & Omar, Reference Pomplun and Omar1997; Verbić, Reference Verbić2012). These dependencies are not related to the respondent’s ability but rather reflect specific interactions between the respondent and the item, arising from the common stimulus of the item stem and knowledge within the item (Beiting-Parrish et al., Reference Beiting-Parrish, Verkuilen, McCluskey, Everson, Wladis, Wiberg, Molenaar, González, Böckenholt and Kim2021). Motivated by the IRT testlet models (Li et al., Reference Li, Bolt and Fu2006, Reference Li, Li and Wang2010; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Bradlow and Wainer2002; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Han, Kim and Kao2022), we propose an extension to the MRM, termed the MRM-LD. The MRM-LD integrates these local dependencies by adding a term that represents person–item interactions into the definition of option attractiveness. This additional term accounts for specific abilities (Li, Reference Li2017) that may influence the respondent’s choice, separate from their general latent ability. The updated definition of attractiveness in the MRM-LD is shown in Formula (5), and the corresponding RCPF is provided in Formula (6):

$$\begin{align}P\left({Y}_{ij}=x|{\theta}_i,{\boldsymbol{a}}_j,{\boldsymbol{d}}_j,{a}_j^{\ast },{\gamma}_{ij}\right)=\frac{\exp \left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.20em {Z}_{jxo}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}+{W}_{jo}{a}_j^{\ast }{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)}{\sum \limits_{m=1}^{X_j}\kern0.20em \exp \left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.20em {Z}_{jmo}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}+{W}_{jo}{a}_j^{\ast }{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)}\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}P\left({Y}_{ij}=x|{\theta}_i,{\boldsymbol{a}}_j,{\boldsymbol{d}}_j,{a}_j^{\ast },{\gamma}_{ij}\right)=\frac{\exp \left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.20em {Z}_{jxo}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}+{W}_{jo}{a}_j^{\ast }{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)}{\sum \limits_{m=1}^{X_j}\kern0.20em \exp \left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.20em {Z}_{jmo}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}+{W}_{jo}{a}_j^{\ast }{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)}\end{align}$$

Both

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij}$

and

${\gamma}_{ij}$

and

![]() ${\theta}_i$

are assumed to follow a standard normal distribution, i.e.,

${\theta}_i$

are assumed to follow a standard normal distribution, i.e.,

![]() $N\left(0,1\right)$

. Specifically,

$N\left(0,1\right)$

. Specifically,

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij}$

represents the respondent’s item-specific ability, reflecting a unique interaction between respondent

${\gamma}_{ij}$

represents the respondent’s item-specific ability, reflecting a unique interaction between respondent

![]() $i$

and item

$i$

and item

![]() $j$

. Parameter

$j$

. Parameter

![]() ${a}_j^{\ast }$

quantifies the magnitude of local dependence within item

${a}_j^{\ast }$

quantifies the magnitude of local dependence within item

![]() $j$

and is constrained to interval

$j$

and is constrained to interval

![]() $\left(0,+\infty \right]$

. Indicator

$\left(0,+\infty \right]$

. Indicator

![]() ${W}_{jo}$

determines the direction of this local dependence: it is set to 1 for correct options and to −1 for incorrect options. This ensures that the effect of local dependence

${W}_{jo}$

determines the direction of this local dependence: it is set to 1 for correct options and to −1 for incorrect options. This ensures that the effect of local dependence

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij}$

on option attractiveness depends on both its sign and option correctness: when

${\gamma}_{ij}$

on option attractiveness depends on both its sign and option correctness: when

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij}>0$

, correct options become more attractive and incorrect options less attractive, while when

${\gamma}_{ij}>0$

, correct options become more attractive and incorrect options less attractive, while when

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij}<0$

, the pattern reverses. It is important to note that for select-N items where only one correct answer is selected (

${\gamma}_{ij}<0$

, the pattern reverses. It is important to note that for select-N items where only one correct answer is selected (

![]() $T=1$

) or only one incorrect answer is excluded (

$T=1$

) or only one incorrect answer is excluded (

![]() $T={O}_j-1$

), the response structure takes the form of SAMC items in which selecting one option automatically excludes all others. Since the SAMC format itself enforces mutual exclusivity among response categories, local dependencies are inherent to this structure and do not require additional local dependence parameters. By setting

$T={O}_j-1$

), the response structure takes the form of SAMC items in which selecting one option automatically excludes all others. Since the SAMC format itself enforces mutual exclusivity among response categories, local dependencies are inherent to this structure and do not require additional local dependence parameters. By setting

![]() ${a}_j^{\ast }=0$

, the MRM-LD simplifies to the standard MRM. Furthermore, for these SAMC items (i.e.,

${a}_j^{\ast }=0$

, the MRM-LD simplifies to the standard MRM. Furthermore, for these SAMC items (i.e.,

![]() $T=1$

or

$T=1$

or

![]() ${O}_j-1$

), the MRM is equivalent to the NRM.

${O}_j-1$

), the MRM is equivalent to the NRM.

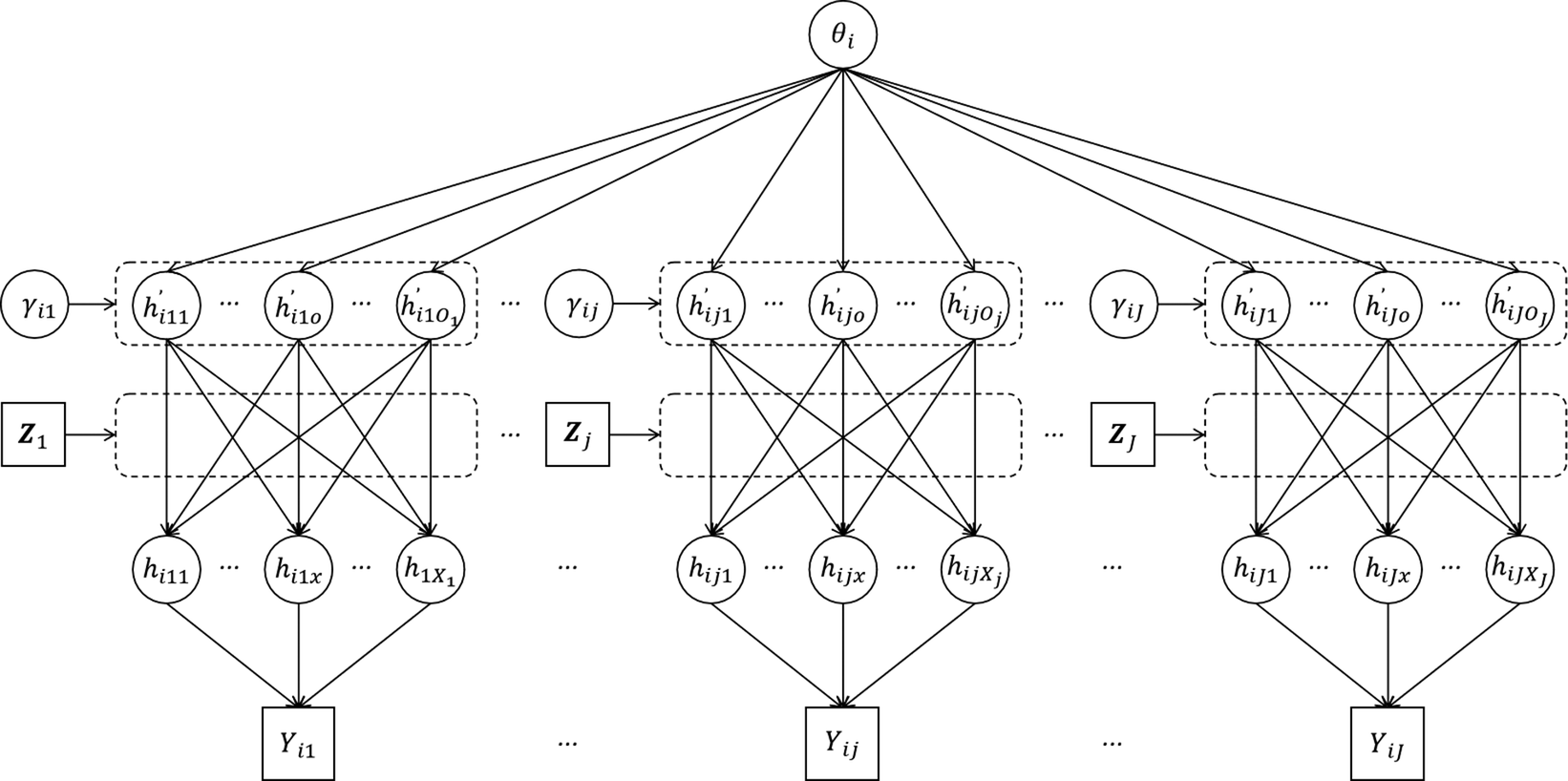

Figure 4 illustrates the architecture of the MRM-LD. The model’s core principle is that a respondent’s latent ability,

![]() ${\theta}_i$

, primarily determines the attractiveness (

${\theta}_i$

, primarily determines the attractiveness (

![]() ${h}_{ijo}^{\prime }$

) of each individual option. For higher-ability respondents, correct options have higher attractiveness values and incorrect options have lower attractiveness values. Building upon this, the respondent’s item-specific ability, represented by

${h}_{ijo}^{\prime }$

) of each individual option. For higher-ability respondents, correct options have higher attractiveness values and incorrect options have lower attractiveness values. Building upon this, the respondent’s item-specific ability, represented by

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij}$

, introduces a local dependence effect that further modulates the attractiveness of each option. Finally, the design matrix

${\gamma}_{ij}$

, introduces a local dependence effect that further modulates the attractiveness of each option. Finally, the design matrix

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

is used to aggregate this individual option attractiveness into the overall attractiveness (

${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

is used to aggregate this individual option attractiveness into the overall attractiveness (

![]() ${h}_{ijx}$

) for each possible RC. This overall attractiveness, in turn, determines the probability distribution over all possible RCs. The observed response is represented by

${h}_{ijx}$

) for each possible RC. This overall attractiveness, in turn, determines the probability distribution over all possible RCs. The observed response is represented by

![]() ${Y}_{ij}$

, which indexes the RC selected by the respondent.

${Y}_{ij}$

, which indexes the RC selected by the respondent.

Figure 4 The MRM-LD model structure diagram.

4.3 Bayesian parameter estimation

In this study, both the MRM and MRM-LD models were developed using Stan (Carpenter et al., Reference Carpenter, Gelman, Hoffman, Lee, Goodrich, Betancourt, Brubaker, Guo, Li and Riddell2017) and then compiled and fitted in R through the cmdstanr package (Gabry et al., Reference Gabry, Češnovar, Johnson and Bronder2024). Stan is a probabilistic programming language that utilizes the No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) algorithm within the Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) framework (Hoffman & Gelman, Reference Hoffman and Gelman2014). Following previous research settings (Kim & Bolt, Reference Kim and Bolt2007; Luo & Jiao, Reference Luo and Jiao2018; Natesan et al., Reference Natesan, Nandakumar, Minka and Rubright2016), the prior distributions of the model parameters and responses are set as follows:

![]() ${\theta}_i\sim \mathrm{Normal}\left(0,1\right)$

,

${\theta}_i\sim \mathrm{Normal}\left(0,1\right)$

,

![]() ${a}_{jo}\sim \mathrm{Normal}\left(0,2\right)$

,

${a}_{jo}\sim \mathrm{Normal}\left(0,2\right)$

,

![]() ${d}_{jo}\sim \mathrm{Normal}\left(0,2\right)$

,

${d}_{jo}\sim \mathrm{Normal}\left(0,2\right)$

,

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij}\sim \mathrm{Normal}\left(0,1\right)$

,

${\gamma}_{ij}\sim \mathrm{Normal}\left(0,1\right)$

,

![]() ${a}_j^{\ast}\sim \mathrm{Lognormal}\left(0,2\right)$

,

${a}_j^{\ast}\sim \mathrm{Lognormal}\left(0,2\right)$

,

![]() ${Y}_{ij}\sim \mathrm{Categorical}\left(P\left({Y}_{ij}=x|{\theta}_i,{\boldsymbol{a}}_j,{\boldsymbol{d}}_j,{a}_j^{\ast },{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)$

. For select-N items, the following constraints apply:

${Y}_{ij}\sim \mathrm{Categorical}\left(P\left({Y}_{ij}=x|{\theta}_i,{\boldsymbol{a}}_j,{\boldsymbol{d}}_j,{a}_j^{\ast },{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)$

. For select-N items, the following constraints apply:

![]() $\sum _{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.1em {a}_{jo}=0,\sum _{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.1em {d}_{jo}=0$

.

$\sum _{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.1em {a}_{jo}=0,\sum _{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.1em {d}_{jo}=0$

.

Thus, the likelihood function for the MRM-LD can be expressed as:

$$\begin{align}L\left(\boldsymbol{Y}\mid \boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{a},\boldsymbol{d},{\boldsymbol{a}}^{\ast},\boldsymbol{\gamma} \right)=\prod \limits_{i=1}^N\kern0.1em \prod \limits_{j=1}^J\kern0.1em \frac{\exp \left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.20em {Z}_{j,{Y}_{ij},o}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}+{W}_{jo}{a}_j^{\ast }{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)}{\sum \limits_{m=1}^{X_j}\kern0.20em \exp \left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.20em {Z}_{jmo}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}+{W}_{jo}{a}_j^{\ast }{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)}\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}L\left(\boldsymbol{Y}\mid \boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{a},\boldsymbol{d},{\boldsymbol{a}}^{\ast},\boldsymbol{\gamma} \right)=\prod \limits_{i=1}^N\kern0.1em \prod \limits_{j=1}^J\kern0.1em \frac{\exp \left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.20em {Z}_{j,{Y}_{ij},o}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}+{W}_{jo}{a}_j^{\ast }{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)}{\sum \limits_{m=1}^{X_j}\kern0.20em \exp \left(\sum \limits_{o=1}^{O_j}\kern0.20em {Z}_{jmo}\left({a}_{jo}{\theta}_i+{d}_{jo}+{W}_{jo}{a}_j^{\ast }{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)}\end{align}$$

![]() ${Z}_{j,{Y}_{ij},o}$

specifically refers to the element in

${Z}_{j,{Y}_{ij},o}$

specifically refers to the element in

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

matrix corresponding to this observed response index

${\boldsymbol{Z}}_j$

matrix corresponding to this observed response index

![]() ${Y}_{ij}$

. Its value indicates whether option

${Y}_{ij}$

. Its value indicates whether option

![]() $o$

was selected (1) or not selected (0) within the specific RC indexed by

$o$

was selected (1) or not selected (0) within the specific RC indexed by

![]() ${Y}_{ij}$

. The joint posterior probability of the parameters in the MRM-LD can be expressed as:

${Y}_{ij}$

. The joint posterior probability of the parameters in the MRM-LD can be expressed as:

5 Empirical study

The primary objective of this study is to validate the advantages and practical applicability of the new models in comparison to traditional scoring methods through empirical data analysis, while also offering practical recommendations for theirs implementation. Additionally, this study compares the test performance of three MR item formats—CMS, MTF, and select-N—using the new models to provide empirical evidence for their relative psychometric properties.

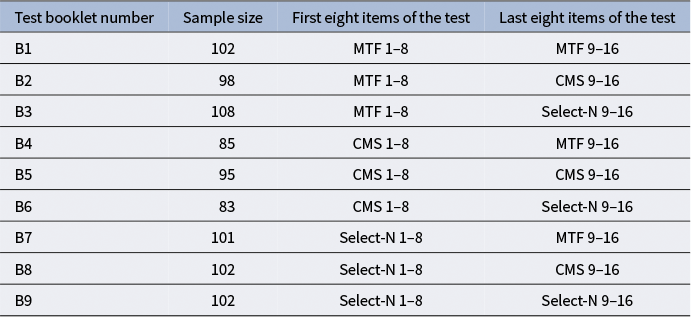

5.1 Design

In this study, a set of 16 MR items were developed, each with five options, based on the “Light Phenomena” chapter of eighth-grade physics in Chinese. These items and their options were sourced from the item bank website (https://zujuan.xkw.com) and reviewed by two experienced junior high school physics teachers. Three versions of each item were created: MTF, CMS, and select-N, by modifying the wording of the instructions. Among the 16 items, one item has one correct option, seven items have two correct options, six items have three correct options, and two items have four correct options. The 16 items were divided into two parts, the first eight items and the last eight items, and combined into nine test booklets with different item format pairings (see Table 3). This design ensured anchor item consistency across different item formats; for instance, in test booklets B1, B2, and B3, the first half contains MTF items, making the second half of the booklets comparable. This resulted in nine anchor item combinations. This approach allows the model to estimate parameters that are comparable across items (Betts et al., Reference Betts, Muntean, Kim and Kao2022; Ricker & von Davier, Reference Ricker and von Davier2007).

Table 3 Empirical study test booklet design.

Note: B1–B9 represent nine test booklets with different combinations of item formats across two halves of the test.

A computerized test was administered to 937 students from 19 classes in the eight grade of a junior high school in China, under the supervision of their teachers. Each student was randomly assigned one of the nine test booklets. Before the test, each student was asked to report their score category (seven ordinal levels: 1 for below 39, 2 for 40–49, 3 for 50–59, 4 for 60–69, 5 for 70–79, 6 for 80–89, and 7 for 90–100) based on their performance in the midterm physics examination, which was administered within one month prior to this test. This information was utilized as a criterion for validation. Since this was a low-stakes test, to prevent estimation bias due to lack of student effort, subjective effort scores on a 10-point (i.e., 1 means least effort and 10 means most effort) item were collected after the test (OECD, 2023). Students who scored 4 or below on the effort scale were excluded, resulting in a final sample size of 876. On average, each item was answered 292 times (SD = 13.3).

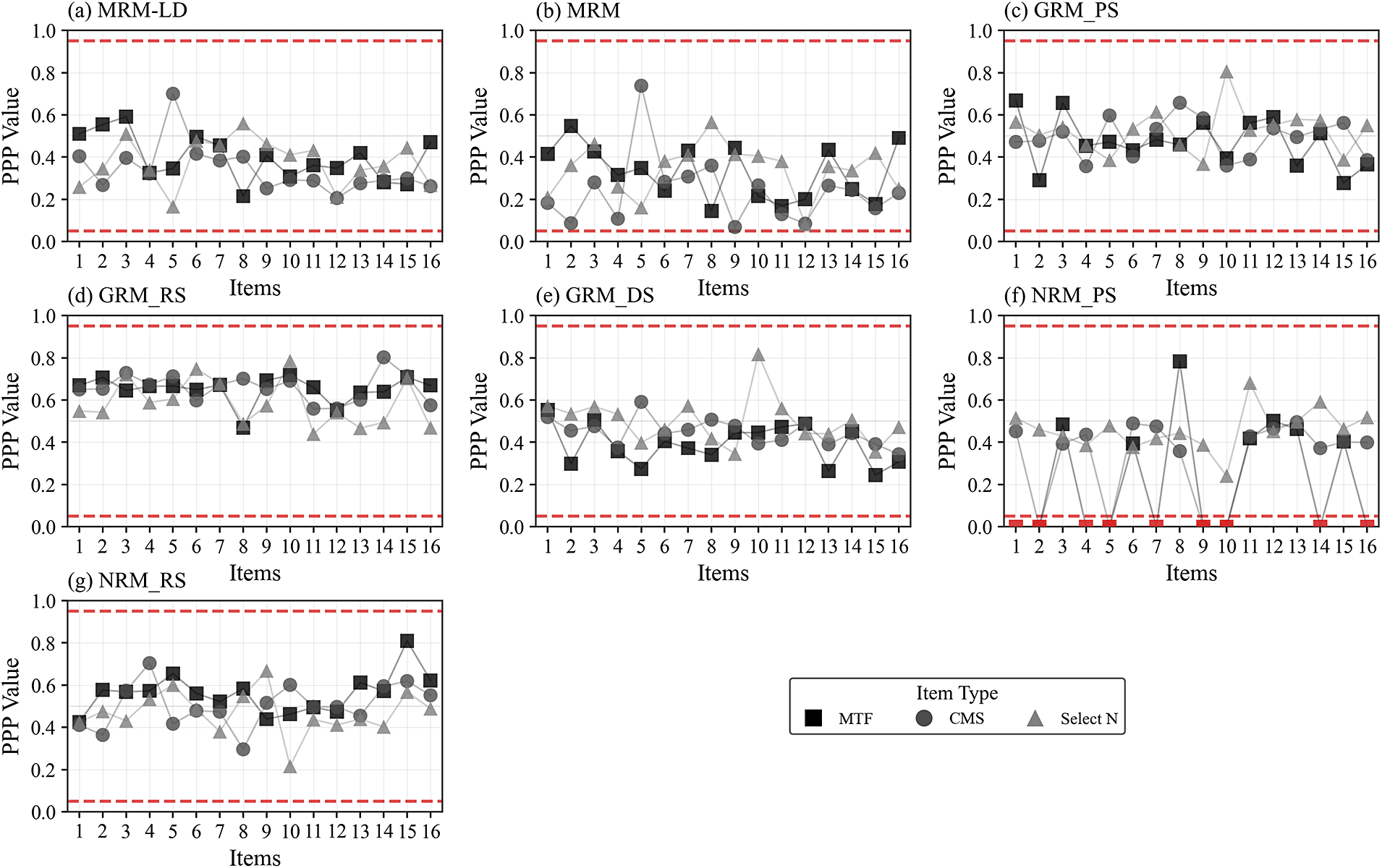

Figure 5 Posterior predictive model checks for each model across different MR item types.

Note: Red dashed horizontal lines mark the threshold boundaries at PPP = 0.05 and PPP = 0.95. Red points indicate PPP values outside the 0.05–0.95 acceptable range.

The data were fitted using the new models, MRM and MRM-LD, as well as traditional polytomous models, Graded Response Model (GRM, Samejima, Reference Samejima1968) and NRM. MRM and MRM-LD models were applied to RC data. In contrast, GRM and NRM utilized three distinct types of response data: PS, RS, and DS, forming models such as GRMPS, NRMPS, etc. When using DS data, GRM and NRM are mathematically equivalent; therefore, only the performance of GRMDS is reported. All models were estimated using Stan with two parallel Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains, each with 1,000 samples. To ensure the stability of the sampling, the first 500 samples were discarded. To ensure fair comparisons across models and to align the latent ability in the same direction as the score, the initial value of

![]() ${\theta}_i$

for all models was set to the z-score of the total test score under DS, with all other parameters left to be randomly initialized by prior distributions. The convergence of model parameters was evaluated using the potential scale reduction factor (PSRF; Brooks & Gelman, Reference Brooks and Gelman1998). A PSRF value below 1.1 was considered indicating sufficient convergence. In this study, the PSRF of all model parameters was below 1.1, indicating convergence and good mixing of the posterior distribution. All parameter estimates are presented in Supplementary Tables S1–S7.

${\theta}_i$

for all models was set to the z-score of the total test score under DS, with all other parameters left to be randomly initialized by prior distributions. The convergence of model parameters was evaluated using the potential scale reduction factor (PSRF; Brooks & Gelman, Reference Brooks and Gelman1998). A PSRF value below 1.1 was considered indicating sufficient convergence. In this study, the PSRF of all model parameters was below 1.1, indicating convergence and good mixing of the posterior distribution. All parameter estimates are presented in Supplementary Tables S1–S7.

To evaluate model performance, we first assessed absolute fit using Posterior Predictive p-values (PPP) (Gelman et al., Reference Gelman, Meng and Stern1996; Sinharay, Reference Sinharay2005). Relative fit was then compared using the Widely Applicable Information Criterion (WAIC) and Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOO) (Vehtari et al., Reference Vehtari, Gelman and Gabry2015). In addition, we also evaluated measurement precision via marginal IRT reliability (Green et al., Reference Green, Bock, Humphreys, Linn and Reckase1984; Zu & Kyllonen, Reference Zu and Kyllonen2020) and compared test information functions, extending the calculation for MRM and MRM-LD against the GRM and NRM (Lima Passos et al., Reference Lima Passos, Berger and Tan2007; Ostini & Nering, Reference Ostini and Nering2006). Finally, criterion-related validity was examined using Spearman’s rank-order correlation with preliminary physics exam grades. The corresponding computational details for these metrics are presented in Appendix B.

5.2 Empirical study results

5.2.1 Absolute fit

Figure 5 presents the PPP indices for the new models, the MRM-LD and MRM, fitted to the RC data of MR items, as well as for the GRM and NRM fitted to PS, RS, and DS data. The upper and lower red dashed lines in Figure 5 represent the limits of 0.95 and 0.05, respectively. It can be observed that except for the NRM fitted to PS data, where some MTF and CMS items exhibit misfit with PPP values less than 0.05, all other models show no significant discrepancies between model predictions and the data across the MTF, CMS, and select-N items.

5.2.2 Relative fit

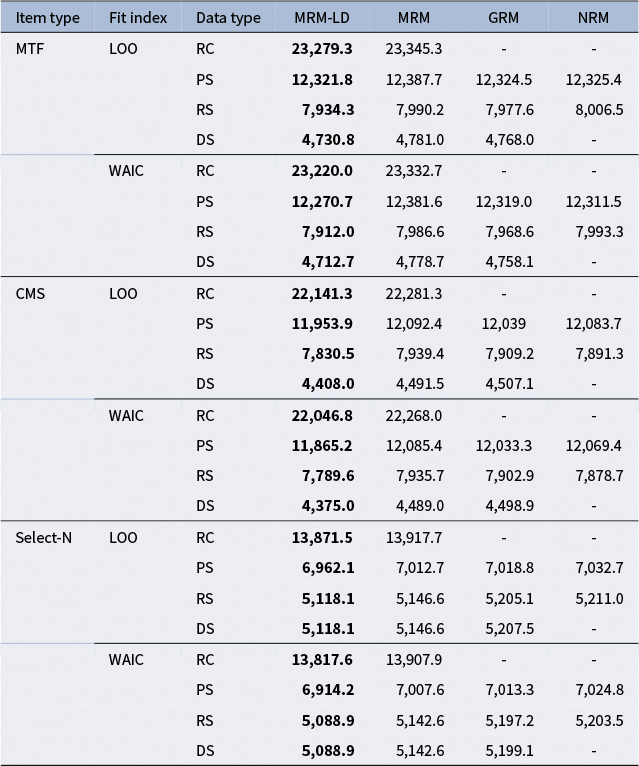

Table 4 presents the WAIC and LOO results for the four models across different MR item types. Lower WAIC and LOO values indicate superior model fit. Primarily, across all scenarios, the MRM-LD consistently outperforms the MRM, suggesting that incorporating the local dependence structure in the MRM-LD is crucial for improving the model fit when analyzing MR data. Furthermore, across all data types, the MRM-LD demonstrates the best performance according to both LOO and WAIC values. When compared with the GRM and the NRM, the MRM-LD shows superior performance at all data types. While the GRM and the NRM perform similarly, the GRM slightly outperforms the NRM in most cases.

Table 4 Results of relative fit indices.

Note: RC, PS, RS, and DS represent four data types: response combinations, partial scoring, Ripkey scoring, and dichotomous scoring, respectively. Boldface indicates the best-fitting model.

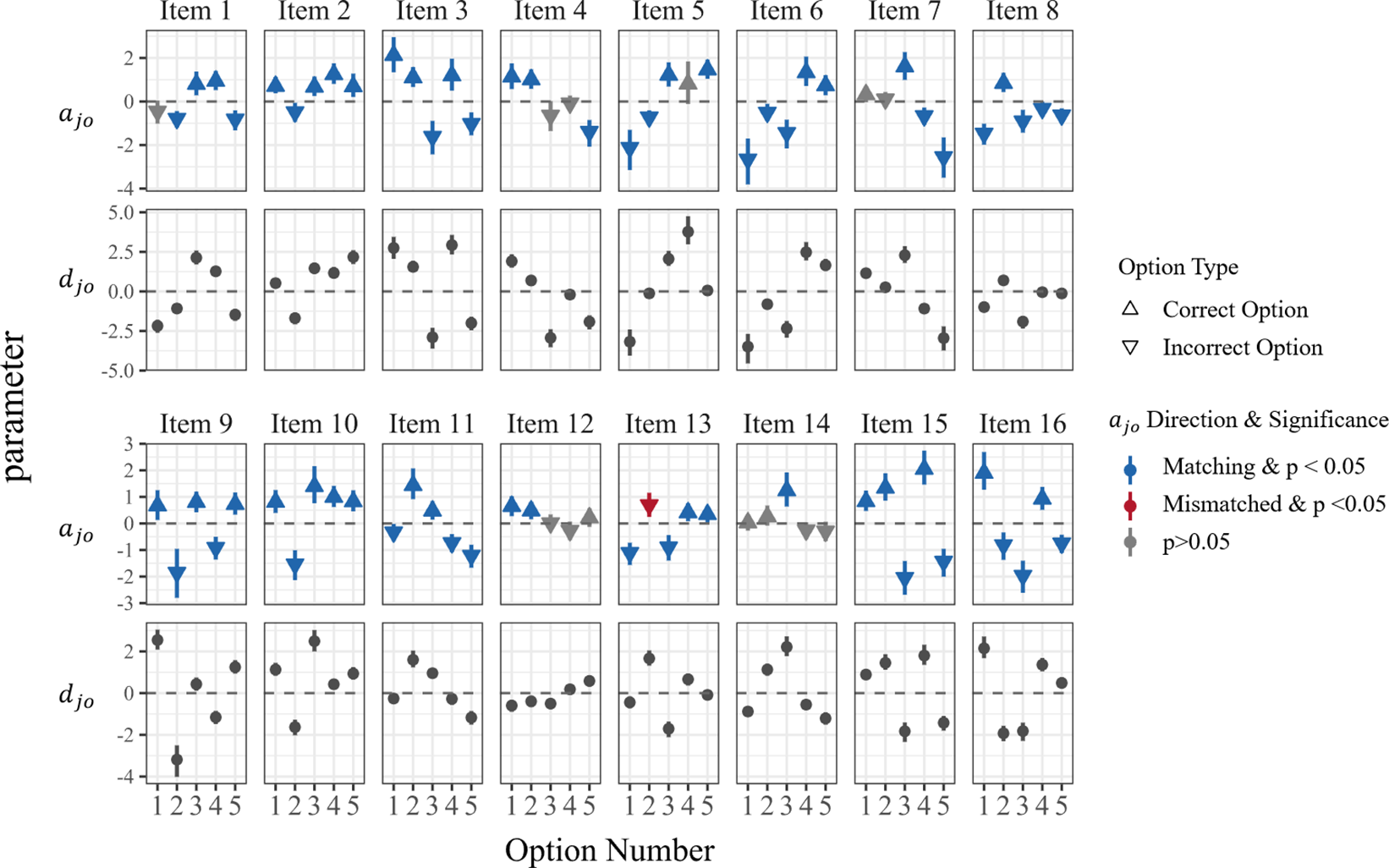

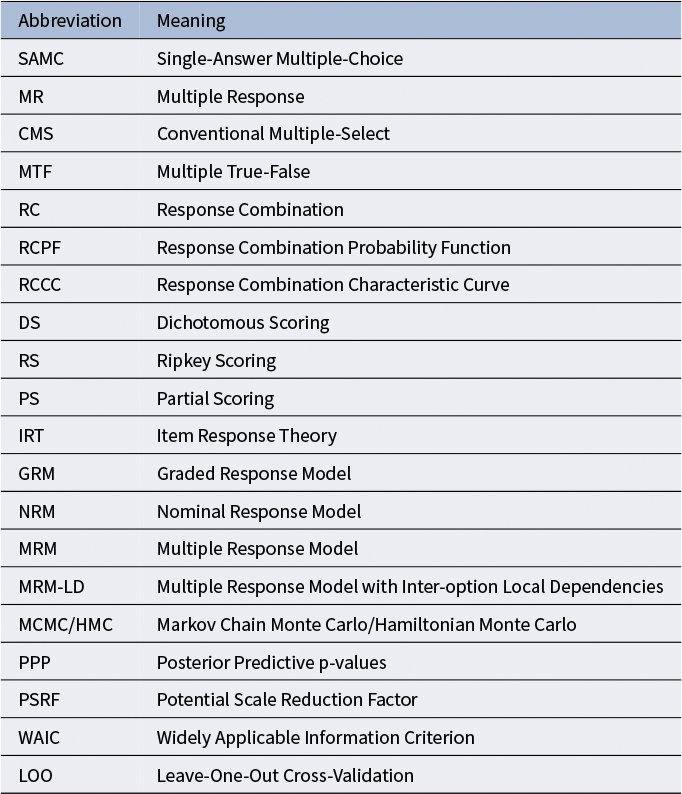

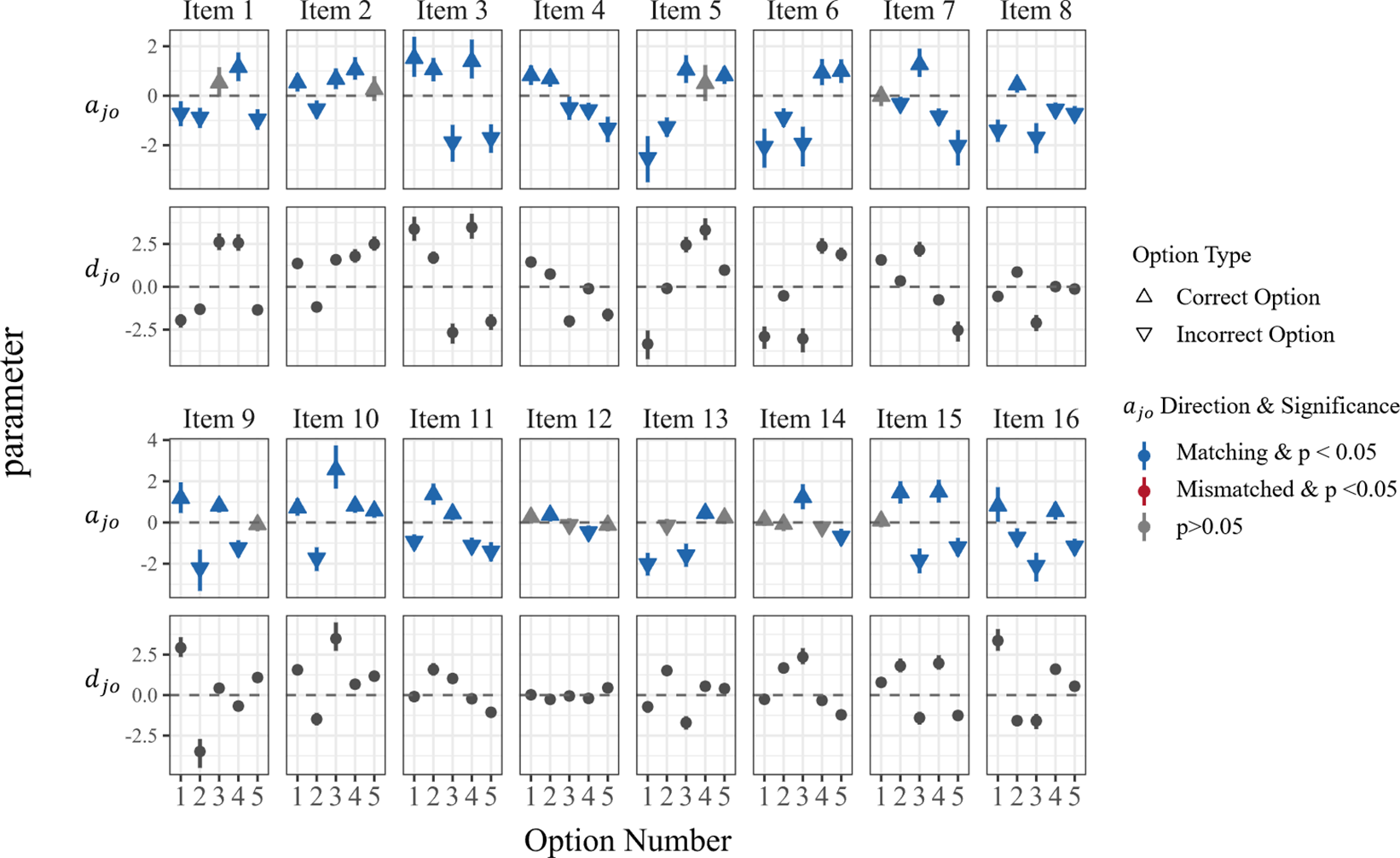

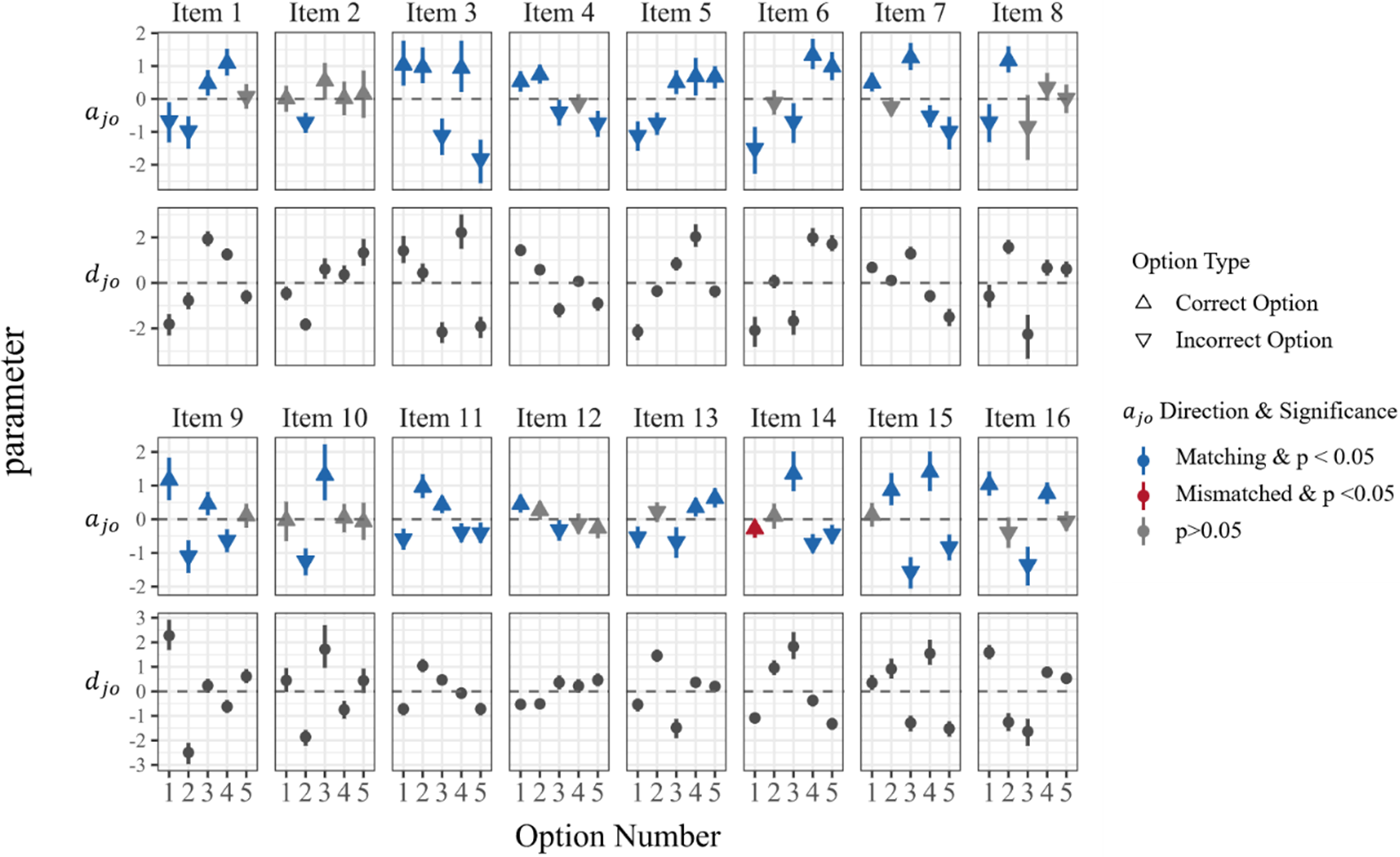

Figure 6 Item parameter distributions (

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

and

${a}_{jo}$

and

![]() ${d}_{jo}$

) of the MRM-LD for CMS items.

${d}_{jo}$

) of the MRM-LD for CMS items.

5.2.3 Item parameters

The fit indices consistently demonstrate that the MRM-LD is the optimal model for analyzing this real dataset. Given this finding, our subsequent analysis centers on the item parameters estimated by the MRM-LD model. These parameters are detailed in Supplementary Table S1.

Taking CMS items as an example, Figure 6 illustrates the distributions of the estimated slope (

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

) and intercept (

${a}_{jo}$

) and intercept (

![]() ${d}_{jo}$

) parameters from the MRM-LD. Appendix A includes Figures A1 and A2, which present similar distributions for MTF and select-N items, respectively.

${d}_{jo}$

) parameters from the MRM-LD. Appendix A includes Figures A1 and A2, which present similar distributions for MTF and select-N items, respectively.

At the option level, the sign and statistical significance of

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

parameter in relation to the predefined answer key (

${a}_{jo}$

parameter in relation to the predefined answer key (

![]() ${W}_{jo}$

) can reveal potential directional inconsistencies. When option

${W}_{jo}$

) can reveal potential directional inconsistencies. When option

![]() $o$

for item

$o$

for item

![]() $j$

is designated as correct (

$j$

is designated as correct (

![]() ${W}_{jo}=1$

, indicated by an upward triangle in Figure 6), the expected

${W}_{jo}=1$

, indicated by an upward triangle in Figure 6), the expected

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

parameter should be positive. Conversely, if it is designated as incorrect (

${a}_{jo}$

parameter should be positive. Conversely, if it is designated as incorrect (

![]() ${W}_{jo}=-1$

, indicated by a downward triangle in Figure 6), the expected

${W}_{jo}=-1$

, indicated by a downward triangle in Figure 6), the expected

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

should be negative. A significant

${a}_{jo}$

should be negative. A significant

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

parameter whose sign is consistent with the designated answer (i.e., matches the expected direction) is marked in blue. A significant

${a}_{jo}$

parameter whose sign is consistent with the designated answer (i.e., matches the expected direction) is marked in blue. A significant

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

parameter whose sign contradicts the intended direction (marked in red) indicates a discrepancy with the specified answer. Options with non-significant

${a}_{jo}$

parameter whose sign contradicts the intended direction (marked in red) indicates a discrepancy with the specified answer. Options with non-significant

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

parameters (marked in gray) are considered ambiguous or low-discriminating, suggesting areas for further item optimization.

${a}_{jo}$

parameters (marked in gray) are considered ambiguous or low-discriminating, suggesting areas for further item optimization.

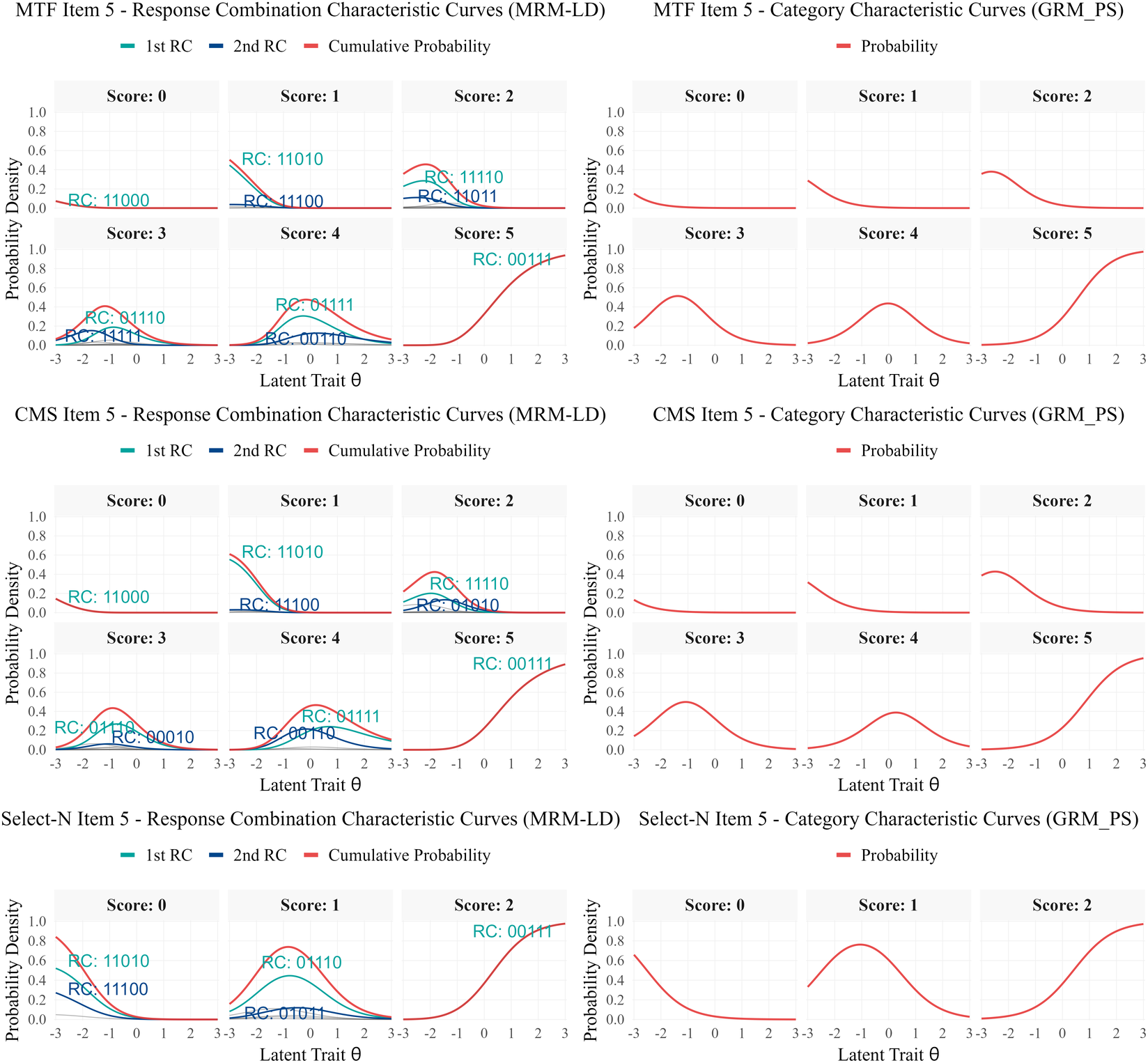

Figure 7 Item characteristic curves of the MRM-LD and GRMPS for MTF, CMS and select-N item (item 5).

Note: Scores calculated using Partial Scoring method (1 point per correctly judged option). For each score level, 1st RC and 2nd RC indicate the most and second-most probable response combinations. Cumulative Probability shows the total probability of all RCs with that score. For MRM-LD, RC probabilities are calculated conditional on

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij} = 0$

.

${\gamma}_{ij} = 0$

.

Using CMS items as an example, we observe that the vast majority of options (83.75%) align with the theoretically expected direction of the

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

parameter with

${a}_{jo}$

parameter with

![]() $p<.05$

(i.e., the 95% credible interval of estimates does not include zero). This indicates that for most options, the estimated

$p<.05$

(i.e., the 95% credible interval of estimates does not include zero). This indicates that for most options, the estimated

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

parameters are statistically significant and consistent with the intended direction based on the predefined answer key. A smaller proportion (15%) show non-significant

${a}_{jo}$

parameters are statistically significant and consistent with the intended direction based on the predefined answer key. A smaller proportion (15%) show non-significant

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

values, indicating potential ambiguity issues in these options. However, a notable contradiction emerged for the second option of item 13. Specifically,

${a}_{jo}$

values, indicating potential ambiguity issues in these options. However, a notable contradiction emerged for the second option of item 13. Specifically,

![]() ${a}_{13,2}$

was estimated at 0.69 (

${a}_{13,2}$

was estimated at 0.69 (

![]() $p<.05$

). According to the original item design, the fully correct RC was specified as RC[0,0,0,1,1], meaning option 2 (corresponding to the second position in the vector) was intended to be an incorrect option. Yet, the empirical results indicate that option 2 exhibits a significant positive attraction. This suggests that as a respondent’s latent ability (

$p<.05$

). According to the original item design, the fully correct RC was specified as RC[0,0,0,1,1], meaning option 2 (corresponding to the second position in the vector) was intended to be an incorrect option. Yet, the empirical results indicate that option 2 exhibits a significant positive attraction. This suggests that as a respondent’s latent ability (

![]() ${\theta}_i$

) increases, the probability of selecting this option also increases, which is contrary to the item’s design intention. This specific item will be further analyzed in detail in the next section.

${\theta}_i$

) increases, the probability of selecting this option also increases, which is contrary to the item’s design intention. This specific item will be further analyzed in detail in the next section.

5.2.4 Response combination characteristic curve

Based on Formula (6), response combination characteristic curves (RCCCs) depict how the probability of each RC varies with latent ability, offering a fine-grained view beyond score categories. Figure 7 compares the RCCCs from the MRM-LD with category characteristic curves from GRMPS for item 5 across MTF, CMS, and select-N formats. In the MTF format, dominant RCs “migrate” as ability increases: respondents typically transition from easier RCs, through intermediate ones (e.g., RC[1,1,0,1,0] → RC[1,1,1,1,0]), ultimately to the fully correct RC[0,0,1,1,1]. This progression reveals an implicit difficulty ordering among RCs. Notably, RCCCs demonstrate that among RCs sharing the same score, different RCs dominate at different ability levels. For example, among RCs with a score of 3, RC[1,1,1,1,1] dominates at lower abilities, whereas RC[0,1,1,1,0] dominates at higher abilities. A similar pattern is observed for CMS items, whereas the select-N format, by design, involves fewer RCs and score levels due to its structure. Although the MRM-LD and GRMPS can produce similar probabilities at the score level, only the MRM-LD captures and resolves respondents’ behavior at the detailed RC level.

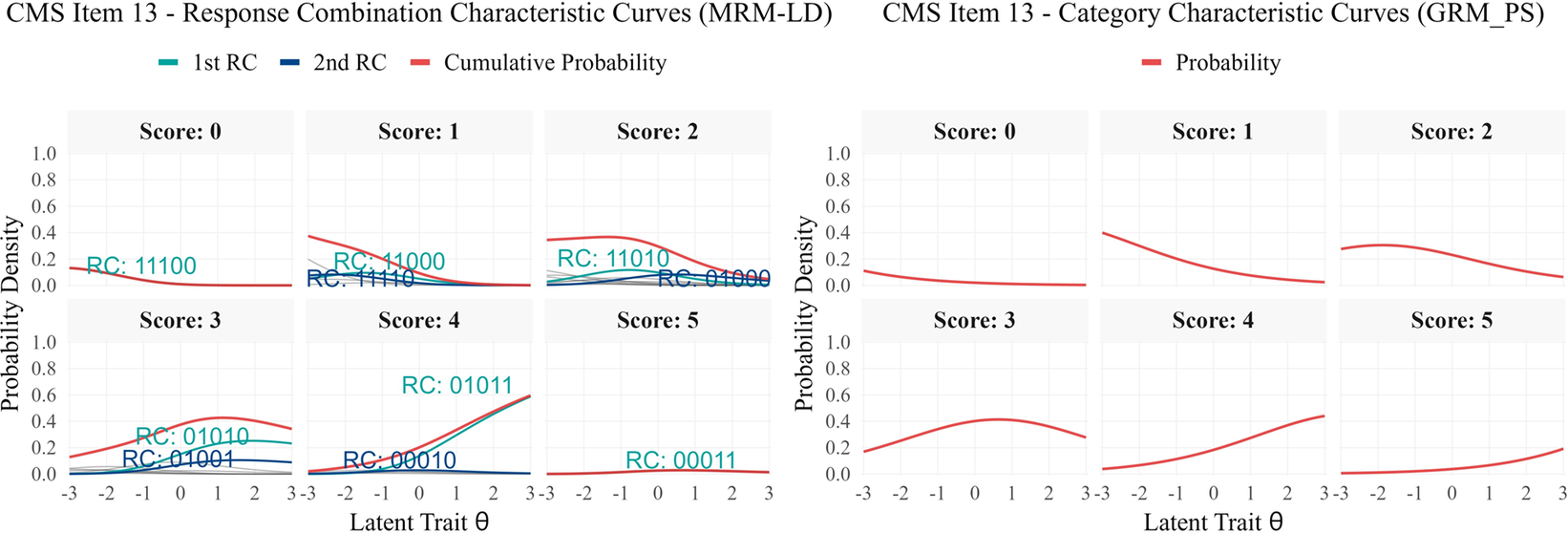

The potential issue of unexpected direction with option 2 of item 13, as previously noted, is further elucidated by the RCCC analysis. Figure 8 shows that the fully correct RC[0,0,0,1,1] remains below 5% across the ability range, while the partially correct RC[0,1,0,1,1] increases with ability and becomes dominant among high-ability respondents. A closer examination of the item stem and option content clarifies this pattern. The item asks respondents to identify correct statements regarding plane mirror imaging. Option 2 states: “Conducting multiple experiments to obtain multiple sets of data is to reduce errors.” This wording is subtly misleading. While repeating measurements to “reduce error” is appropriate when estimating a fixed quantity, it is less applicable when verifying a general law such as plane mirror imaging; in the latter context, multiple trials primarily serve to increase the reliability of conclusions. High-ability students appear to overgeneralize the “repetition reduces error” principle, leading them to select option 2.

Figure 8 Item characteristic curves of the MRM-LD and GRMPS for CMS item type (item 13).

Note: Scores calculated using Partial Scoring method (1 point per correctly judged option). For each score level, 1st RC and 2nd RC indicate the most and second-most probable response combinations. Cumulative Probability shows the total probability of all RCs with that score. For MRM-LD, RC probabilities are calculated conditional on

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij} = 0$

.

${\gamma}_{ij} = 0$

.

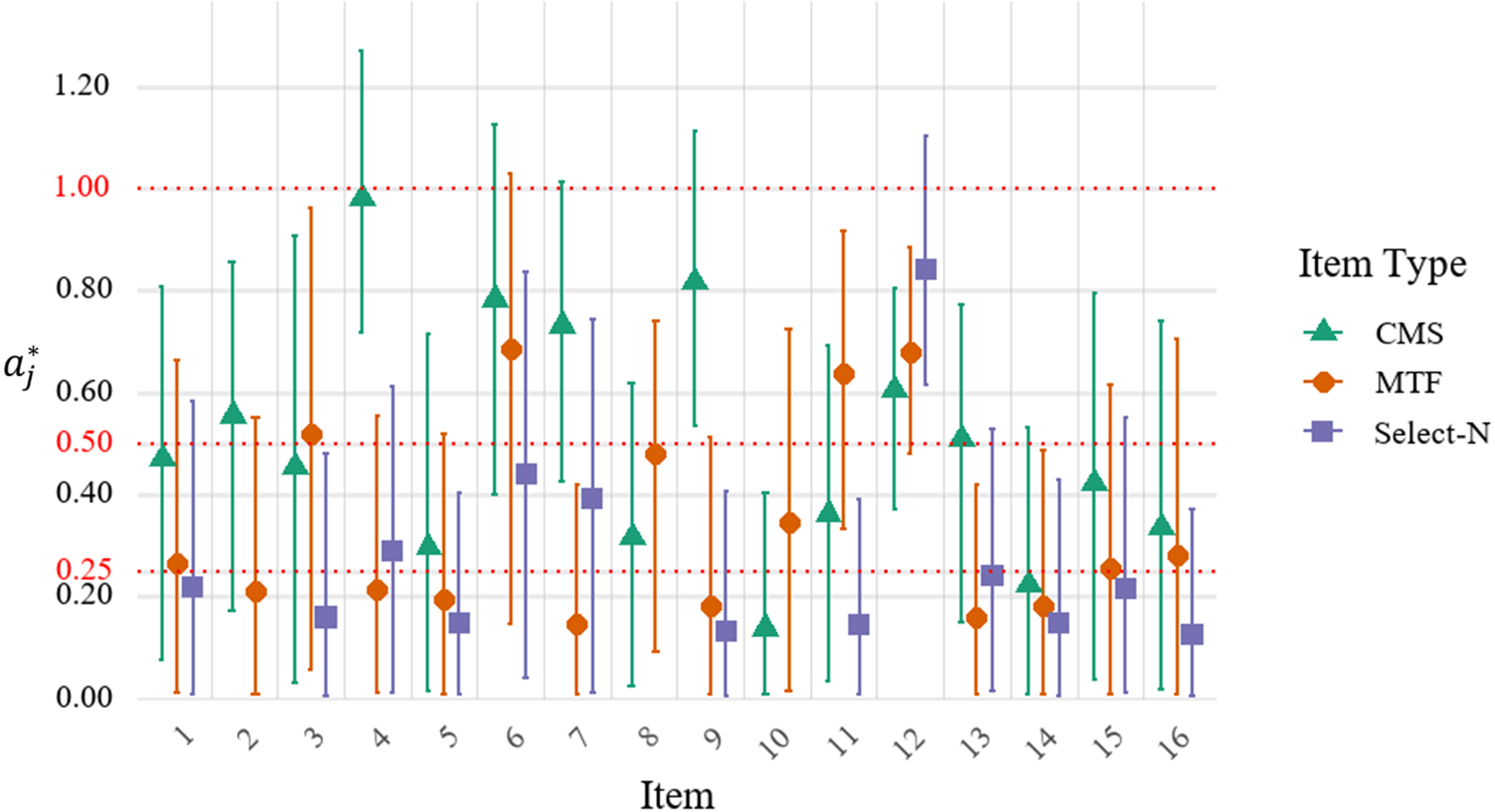

Figure 9 The distribution of the estimate local dependence parameters

![]() ${a}_j^{\ast }$

with 95% CIs for the MRM-LD.

${a}_j^{\ast }$

with 95% CIs for the MRM-LD.

5.2.5 Inter-option local dependence

Figure 9 displays the estimated mean local dependence parameters (

![]() ${a}_j^{\ast }$

) and their 95% confidence intervals by the MRM-LD. Values exceeding 0.5, which typically represent a non-negligible or moderate level of local dependence (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Han, Kim and Kao2022; Wainer et al., Reference Wainer, Bradlow and Wang2007; Wang & Wilson, Reference Wang and Wilson2005), were found in MTF items 3, 6, 11, 12; CMS items 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 12, 13; and select-N item 12. This widespread local dependence explains the better model fit of the MRM-LD over the standard MRM. It implies that responding to these items requires secondary skills beyond the main ability construct. For example, item 12 requires specific calculations for multiple mirror reflections. A student knowing the formula can solve for several options at once, creating strong dependence among them.

${a}_j^{\ast }$

) and their 95% confidence intervals by the MRM-LD. Values exceeding 0.5, which typically represent a non-negligible or moderate level of local dependence (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Han, Kim and Kao2022; Wainer et al., Reference Wainer, Bradlow and Wang2007; Wang & Wilson, Reference Wang and Wilson2005), were found in MTF items 3, 6, 11, 12; CMS items 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 12, 13; and select-N item 12. This widespread local dependence explains the better model fit of the MRM-LD over the standard MRM. It implies that responding to these items requires secondary skills beyond the main ability construct. For example, item 12 requires specific calculations for multiple mirror reflections. A student knowing the formula can solve for several options at once, creating strong dependence among them.

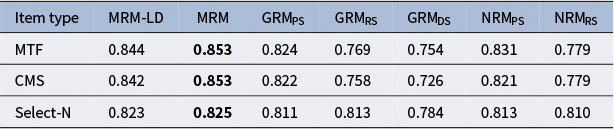

5.2.6 IRT reliability

Table 5 presents the IRT reliability for each model across three item types. The results indicate that both the MRM-LD and MRM yield superior IRT reliability compared to the three traditional methods. Furthermore, while the IRT reliability for MTF and CMS item types showed negligible differences, both were slightly superior to the select-N item type. Overall, the latent ability estimates

![]() ${\theta}_i$

derived from the MRM-LD and MRM are more reliable and exhibit lower measurement error compared to those obtained from traditional methods. Notably, the IRT reliability of the MRM was found to be higher than that of the MRM-LD. This finding aligns with previous research on local dependence modeling (Bradlow, Reference Bradlow1999; Li et al., Reference Li, Li and Wang2010; Lucke, Reference Lucke2005; Marais, Reference Marais, Christensen, Kreiner and Mesbah2012), which has demonstrated that unaccounted-for dependence can lead to an overestimation of ability measurement precision.

${\theta}_i$

derived from the MRM-LD and MRM are more reliable and exhibit lower measurement error compared to those obtained from traditional methods. Notably, the IRT reliability of the MRM was found to be higher than that of the MRM-LD. This finding aligns with previous research on local dependence modeling (Bradlow, Reference Bradlow1999; Li et al., Reference Li, Li and Wang2010; Lucke, Reference Lucke2005; Marais, Reference Marais, Christensen, Kreiner and Mesbah2012), which has demonstrated that unaccounted-for dependence can lead to an overestimation of ability measurement precision.

Table 5 IRT reliability of different models across item types.

Note: Boldface indicates the best model.

5.2.7 Criterion-related validity

Table 6 presents the criterion-related validity of the four models across nine test booklets and different data types. The results reveal that both MRM and MRM-LD consistently achieve comparable criterion-related validities. Notably, the latent ability estimates from MRM-LD and MRM exhibit a stronger correlation with prior physics test scores across most test booklets, compared to those derived from the GRM and NRM (which are based on three traditional scoring methods).

Table 6 Criterion-related validity across nine booklets.

Note: Boldface indicates the best model. All correlation coefficients in the table are significant at the p < 0.001 level.

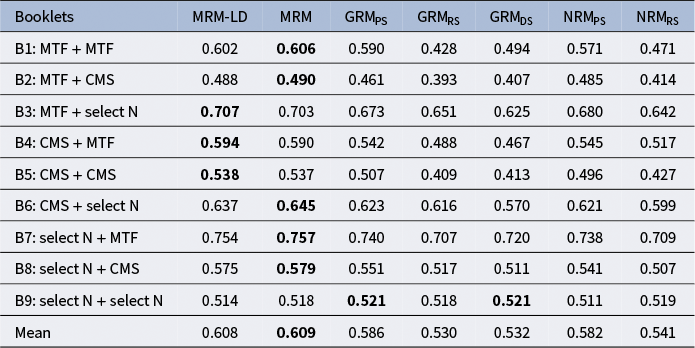

5.2.8 Information curve

Figure 10 illustrates the test information yielded by the four models at different data types across the three MR item types. It is evident that the MRM-LD and the MRM display similar test information curves. For MTF and CMS items, the two new models provide substantially greater information than other models within the ability range of −3 to 0 (i.e., from low to moderate ability), with their peaks occurring at an ability level of approximately −1. Within the ability range of 1 to 3, the information they provide is on par with other models. However, for select-N items, the test information provided is relatively lower compared to the information volume offered by MTF and CMS items. The comparison of different scoring methods yields results consistent with previous research: PS retains the most test information, followed by RS and then DS (Betts et al., Reference Betts, Muntean, Kim and Kao2022; Muckle et al., Reference Muckle, Becker and Wu2011). This study further employed RC data modeling within the MRM framework to optimize response utilization by unlocking the potential information in uncompressed RC data that distinguishes respondents’ abilities. This approach significantly enhances test information and improves the reliability of the test.

Figure 10 Test information curves for each model across different item types.

Note: Information curves for MRM-LD are conditional on

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij} = 0$

.

${\gamma}_{ij} = 0$

.

6 Simulation studies

6.1 Simulation study 1

6.1.1 Design

This study systematically evaluates parameter estimation accuracy through Monte Carlo simulations under conditions mirroring the empirical study. The simulation replicates key elements: 16 five-option MR items with three structures (MTF, CMS, select-N), nine test booklets, sample size N = 876, and an average of 292 responses per item.

Based on MRM-LD parameter estimates (Supplementary Table S1), which demonstrated optimal fit in the empirical study, response probability vectors were calculated using Formula (6). Simulated RC data were generated via categorical distribution:

![]() ${Y}_{ij}\sim \mathrm{Categorical}\left(P\left({Y}_{ij}=x|{\theta}_i,{\boldsymbol{a}}_j,{\boldsymbol{d}}_j,{a}_j^{\ast },{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)$

, and then converted using PS, RS, and DS scoring methods. Both RC and converted datasets were analyzed using MRM, MRM-LD, GRM, and NRM models, following identical empirical settings (i.e., prior distributions, MCMC iterations, convergence criteria). Across 30 replications, all models converged with PSRF <1.1.

${Y}_{ij}\sim \mathrm{Categorical}\left(P\left({Y}_{ij}=x|{\theta}_i,{\boldsymbol{a}}_j,{\boldsymbol{d}}_j,{a}_j^{\ast },{\gamma}_{ij}\right)\right)$

, and then converted using PS, RS, and DS scoring methods. Both RC and converted datasets were analyzed using MRM, MRM-LD, GRM, and NRM models, following identical empirical settings (i.e., prior distributions, MCMC iterations, convergence criteria). Across 30 replications, all models converged with PSRF <1.1.

6.1.2 Evaluation metrics

The accuracy of parameter estimation is evaluated using bias and root mean square error (RMSE) indices:

![]() $\mathrm{Bias}\left(\phi \right)=\frac{1}{R}\sum _{r=1}^R\kern0.1em \left(\hat{\phi}^{(r)}-\phi \right)$

and

$\mathrm{Bias}\left(\phi \right)=\frac{1}{R}\sum _{r=1}^R\kern0.1em \left(\hat{\phi}^{(r)}-\phi \right)$

and

![]() $\mathrm{RMSE}\left(\phi \right)=\sqrt{\frac{1}{R}\sum _{r=1}^R\kern0.20em {\left(\hat{\phi}^{(r)}-\phi \right)}^2}$

, where

$\mathrm{RMSE}\left(\phi \right)=\sqrt{\frac{1}{R}\sum _{r=1}^R\kern0.20em {\left(\hat{\phi}^{(r)}-\phi \right)}^2}$

, where

![]() $\phi$

represents the true parameter value and

$\phi$

represents the true parameter value and

![]() $\hat{\phi}^{(r)}$

is the estimated value obtained from the

$\hat{\phi}^{(r)}$

is the estimated value obtained from the

![]() $r$

-th replication. These two indices were computed for the estimated values of

$r$

-th replication. These two indices were computed for the estimated values of

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

,

${a}_{jo}$

,

![]() ${d}_{jo}$

,

${d}_{jo}$

,

![]() ${a}_j^{\ast }$

, and

${a}_j^{\ast }$

, and

![]() ${\theta}_i$

. Subsequently, the mean values of these indices across all relevant parameters were reported. In addition to these, for person parameters, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the true and estimated latent abilities is also calculated:

${\theta}_i$

. Subsequently, the mean values of these indices across all relevant parameters were reported. In addition to these, for person parameters, the Pearson correlation coefficient between the true and estimated latent abilities is also calculated:

$r=\frac{\sum _{i=1}^N\kern0.20em \sum _{r=1}^R\kern0.20em \left({\phi}_i-\overline{\phi}\right)\left(\hat{\phi}_i^{(r)}-\overline{\hat{\phi }}\right)}{\sqrt{\sum _{i=1}^N\kern0.20em \sum _{r=1}^R\kern0.20em {\left({\phi}_i-\overline{\phi}\right)}^2}\cdotp \sqrt{\sum _{i=1}^N\kern0.20em \sum _{r=1}^R\kern0.20em {\left(\hat{\phi}_i^{(r)}-\overline{\hat{\phi }}\right)}^2}}$

.

$r=\frac{\sum _{i=1}^N\kern0.20em \sum _{r=1}^R\kern0.20em \left({\phi}_i-\overline{\phi}\right)\left(\hat{\phi}_i^{(r)}-\overline{\hat{\phi }}\right)}{\sqrt{\sum _{i=1}^N\kern0.20em \sum _{r=1}^R\kern0.20em {\left({\phi}_i-\overline{\phi}\right)}^2}\cdotp \sqrt{\sum _{i=1}^N\kern0.20em \sum _{r=1}^R\kern0.20em {\left(\hat{\phi}_i^{(r)}-\overline{\hat{\phi }}\right)}^2}}$

.

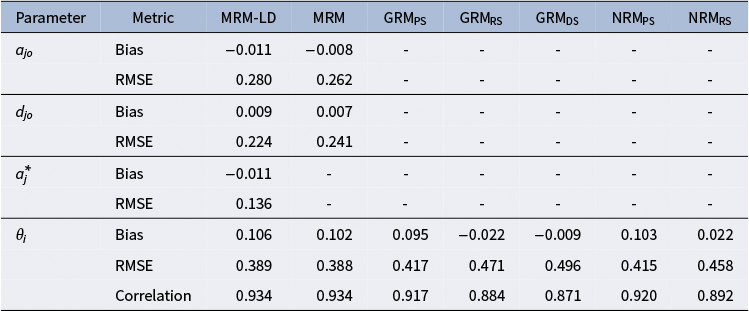

6.1.3 Simulation study 1 results

The Monte Carlo simulation results based on empirical data (see Table 7) are summarized as follows. For item parameter estimation within the MRM framework, both the MRM-LD and MRM showed absolute biases below 0.011 for

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

and

${a}_{jo}$

and

![]() ${d}_{jo}$

, with RMSE values not exceeding 0.280 and 0.224, respectively. Furthermore, the MRM-LD exhibited high estimation accuracy for

${d}_{jo}$

, with RMSE values not exceeding 0.280 and 0.224, respectively. Furthermore, the MRM-LD exhibited high estimation accuracy for

![]() ${a}_j^{\ast }$

(RMSE = 0.136), confirming its capability to accurately recover local dependence structures. For

${a}_j^{\ast }$

(RMSE = 0.136), confirming its capability to accurately recover local dependence structures. For

![]() ${\theta}_i$

parameter, both MRM and MRM-LD substantially outperformed all competing models, achieving RMSE values between 0.388 and 0.389 and correlations with true ability of 0.934. Compared to the GRMPS (correlation = 0.917, RMSE = 0.417) and NRMPS (correlation = 0.884, RMSE = 0.458), both of which are based on PS data, the MRM and MRM-LD, fitted using raw RC data, improved correlation by 1.7%–5.0% and reduced RMSE by 6.9%–15.3%. When compared to models based on DS or RS data (e.g., GRMDS with RMSE = 0.496, correlation = 0.871; GRMRS with RMSE = 0.471, correlation = 0.892), the MRM and MRM-LD achieved RMSE reductions of 17.6%–21.6% and correlation increases of 4.2%–6.3%.

${\theta}_i$

parameter, both MRM and MRM-LD substantially outperformed all competing models, achieving RMSE values between 0.388 and 0.389 and correlations with true ability of 0.934. Compared to the GRMPS (correlation = 0.917, RMSE = 0.417) and NRMPS (correlation = 0.884, RMSE = 0.458), both of which are based on PS data, the MRM and MRM-LD, fitted using raw RC data, improved correlation by 1.7%–5.0% and reduced RMSE by 6.9%–15.3%. When compared to models based on DS or RS data (e.g., GRMDS with RMSE = 0.496, correlation = 0.871; GRMRS with RMSE = 0.471, correlation = 0.892), the MRM and MRM-LD achieved RMSE reductions of 17.6%–21.6% and correlation increases of 4.2%–6.3%.

Table 7 Parameter estimation accuracy of each model in the simulation study 1.

Overall, the simulation validation based on empirical data confirms that the test booklet structure, number of items, and sample size configuration within the empirical research framework are highly feasible. The MRM and MRM-LD demonstrated robust parameter recovery performance. These findings further support the conclusions drawn from the empirical study.

6.2 Simulation study 2

6.2.1 Design

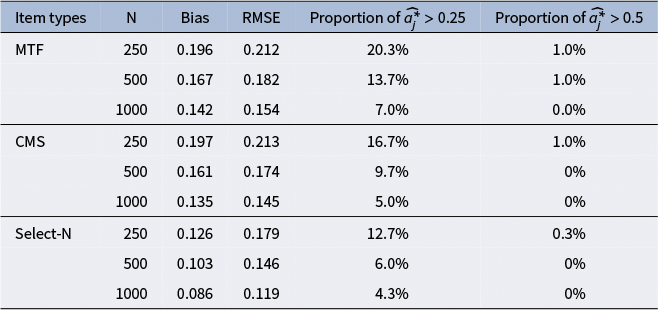

This study extends beyond the single setting of simulation study 1 by using Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate MRM-LD and MRM under broader data conditions, examining parameter estimation accuracy across testing scenarios and potential differences among MR item types.

A four-factor experimental design included: (1) item type: MTF, CMS, select-N; (2) test length:

![]() $J=5,10,15$

; (3) options per item:

$J=5,10,15$

; (3) options per item:

![]() $O=5,7$

; (4) sample size:

$O=5,7$

; (4) sample size:

![]() $N=250,500,1000$

; and (5) fitted models: MRM-LD, MRM, GRMPS, GRMRS, GRMDS, NRMPS, and NRMRS, yielding

$N=250,500,1000$

; and (5) fitted models: MRM-LD, MRM, GRMPS, GRMRS, GRMDS, NRMPS, and NRMRS, yielding

![]() $3\times 3\times 2\times 3\times 7=378$

conditions. The number of correct options per item was configured proportionally for each test length. For J = 5, the configurations included items with 1, 2, 3 (×2), and four correct options for O = 5, and 2, 3, 4 (×2), and five correct options for O = 7. These patterns were scaled accordingly for J = 10 and J = 15.

$3\times 3\times 2\times 3\times 7=378$

conditions. The number of correct options per item was configured proportionally for each test length. For J = 5, the configurations included items with 1, 2, 3 (×2), and four correct options for O = 5, and 2, 3, 4 (×2), and five correct options for O = 7. These patterns were scaled accordingly for J = 10 and J = 15.

Based on previous research (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Han, Kim and Kao2022; Natesan et al., Reference Natesan, Nandakumar, Minka and Rubright2016) and empirical findings, parameters were set as:

![]() ${\theta}_i\sim \mathrm{Norm}\left(0,1\right)$

,

${\theta}_i\sim \mathrm{Norm}\left(0,1\right)$

,

![]() ${\gamma}_{ij}\sim \mathrm{Norm}\left(0,1\right)$

,

${\gamma}_{ij}\sim \mathrm{Norm}\left(0,1\right)$

,

![]() ${d}_{jo}\sim \mathrm{Norm}\left(0,1\right)$

, and

${d}_{jo}\sim \mathrm{Norm}\left(0,1\right)$

, and

![]() ${a}_{jo}\sim \mathrm{Lognormal}\left(0,0.5\right)$

for

${a}_{jo}\sim \mathrm{Lognormal}\left(0,0.5\right)$

for

![]() ${W}_{jo}=1$

or

${W}_{jo}=1$

or

![]() $-\mathrm{Lognormal}\left(0,0.5\right)$

for

$-\mathrm{Lognormal}\left(0,0.5\right)$

for

![]() ${W}_{jo}=-1$

. Local dependence parameters

${W}_{jo}=-1$

. Local dependence parameters

![]() ${a}_j^{\ast }$

were set to small (0.25), medium (0.5), and large (1) effects (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Han, Kim and Kao2022). The number of items at each effect level (small, medium, large) was (1, 2, 2) for J = 5, (3, 3, 4) for J = 10, and (5, 5, 5) for J = 15. Responses

${a}_j^{\ast }$

were set to small (0.25), medium (0.5), and large (1) effects (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Han, Kim and Kao2022). The number of items at each effect level (small, medium, large) was (1, 2, 2) for J = 5, (3, 3, 4) for J = 10, and (5, 5, 5) for J = 15. Responses

![]() ${Y}_{ij}$

were generated from a categorical distribution based on probabilities from Formula (6), with all other settings consistent with simulation study 1.

${Y}_{ij}$

were generated from a categorical distribution based on probabilities from Formula (6), with all other settings consistent with simulation study 1.

6.2.2 Simulation study 2 results

Supplementary Tables S8 and S9 indicate that both MRM-LD and MRM yielded unbiased (near-zero bias) estimates for the

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

and

${a}_{jo}$

and

![]() ${d}_{jo}$

parameters. For

${d}_{jo}$

parameters. For

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

, the MRM performed slightly better, with a mean RMSE of 0.193 (range: 0.118–0.307), compared to 0.205 (range: 0.124–0.327) for MRM-LD. Conversely, for

${a}_{jo}$

, the MRM performed slightly better, with a mean RMSE of 0.193 (range: 0.118–0.307), compared to 0.205 (range: 0.124–0.327) for MRM-LD. Conversely, for

![]() ${d}_{jo}$

, the MRM-LD was slightly more accurate, showing a mean RMSE of 0.147 (range: 0.093–0.260) versus 0.158 (range: 0.105–0.268) for MRM. Sample size was the most significant factor: increasing it from 250 to 1000 reduced RMSE for both parameters by more than 50%. Item type also mattered, as MTF and CMS items yielded higher and comparable accuracy (e.g., the RMSEs of

${d}_{jo}$

, the MRM-LD was slightly more accurate, showing a mean RMSE of 0.147 (range: 0.093–0.260) versus 0.158 (range: 0.105–0.268) for MRM. Sample size was the most significant factor: increasing it from 250 to 1000 reduced RMSE for both parameters by more than 50%. Item type also mattered, as MTF and CMS items yielded higher and comparable accuracy (e.g., the RMSEs of

![]() ${d}_{jo}$

for MRM-LD ranged from 0.093 to 0.200 for MTF and from 0.093 to 0.199 for CMS, respectively), outperforming select-N items (e.g., the RMSEs of

${d}_{jo}$

for MRM-LD ranged from 0.093 to 0.200 for MTF and from 0.093 to 0.199 for CMS, respectively), outperforming select-N items (e.g., the RMSEs of

![]() ${d}_{jo}$

for MRM-LD ranged from 0.100 to 0.260). Increasing the number of options improved parameter recovery only for select-N items, whereas the number of items had no significant effect on the estimation of

${d}_{jo}$

for MRM-LD ranged from 0.100 to 0.260). Increasing the number of options improved parameter recovery only for select-N items, whereas the number of items had no significant effect on the estimation of

![]() ${a}_{jo}$

or

${a}_{jo}$

or

![]() ${d}_{jo}$

.

${d}_{jo}$

.

Supplementary Table S10 confirms that MRM-LD provided unbiased estimates for the local dependence parameter

![]() ${a}_j^{\ast }$

, demonstrating good recovery performance (mean RMSE was 0.147, with a range of 0.093 to 0.260). Similar to the other parameters, increasing the sample size from 250 to 1000 reduced the RMSE by approximately 50%. A larger number of items also led to a slight improvement in the accuracy of

${a}_j^{\ast }$

, demonstrating good recovery performance (mean RMSE was 0.147, with a range of 0.093 to 0.260). Similar to the other parameters, increasing the sample size from 250 to 1000 reduced the RMSE by approximately 50%. A larger number of items also led to a slight improvement in the accuracy of

![]() ${a}_j^{\ast }$

, with MTF and CMS items showing slightly superior recovery than select-N items.

${a}_j^{\ast }$

, with MTF and CMS items showing slightly superior recovery than select-N items.

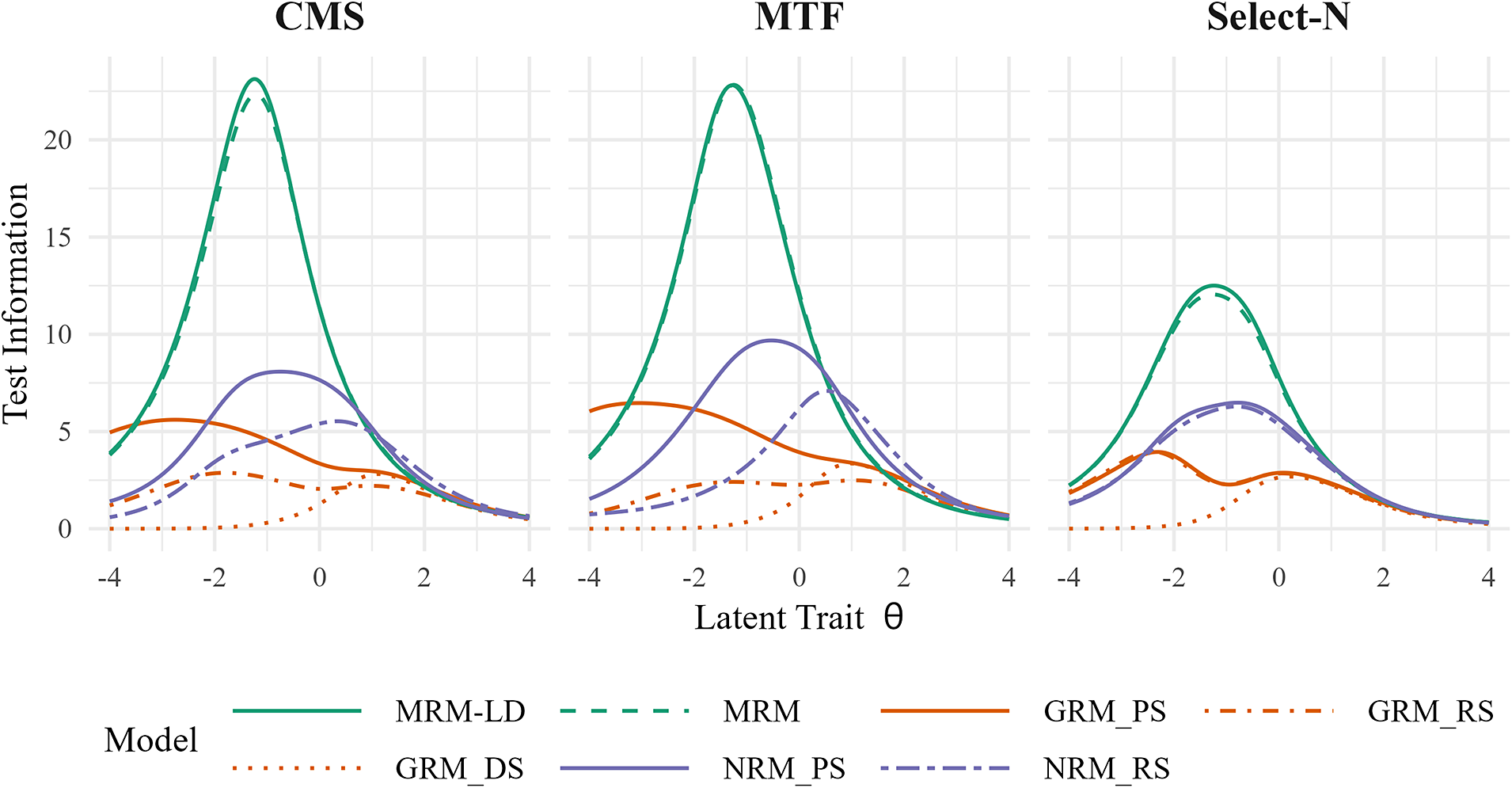

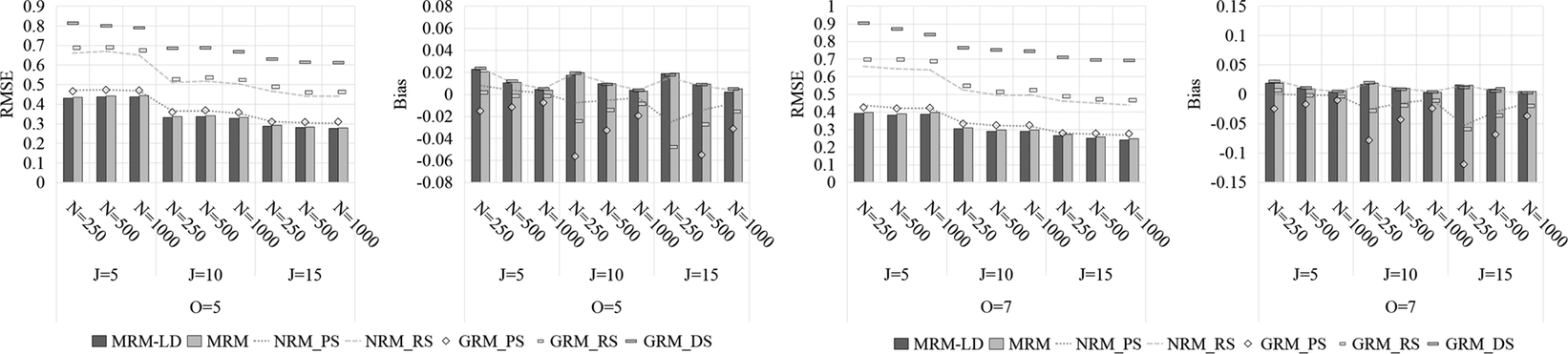

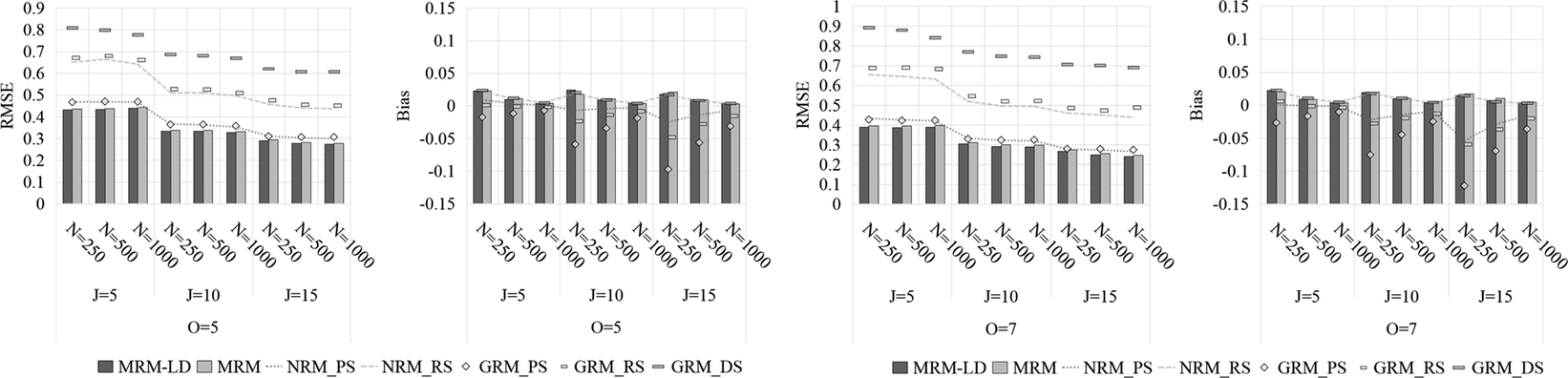

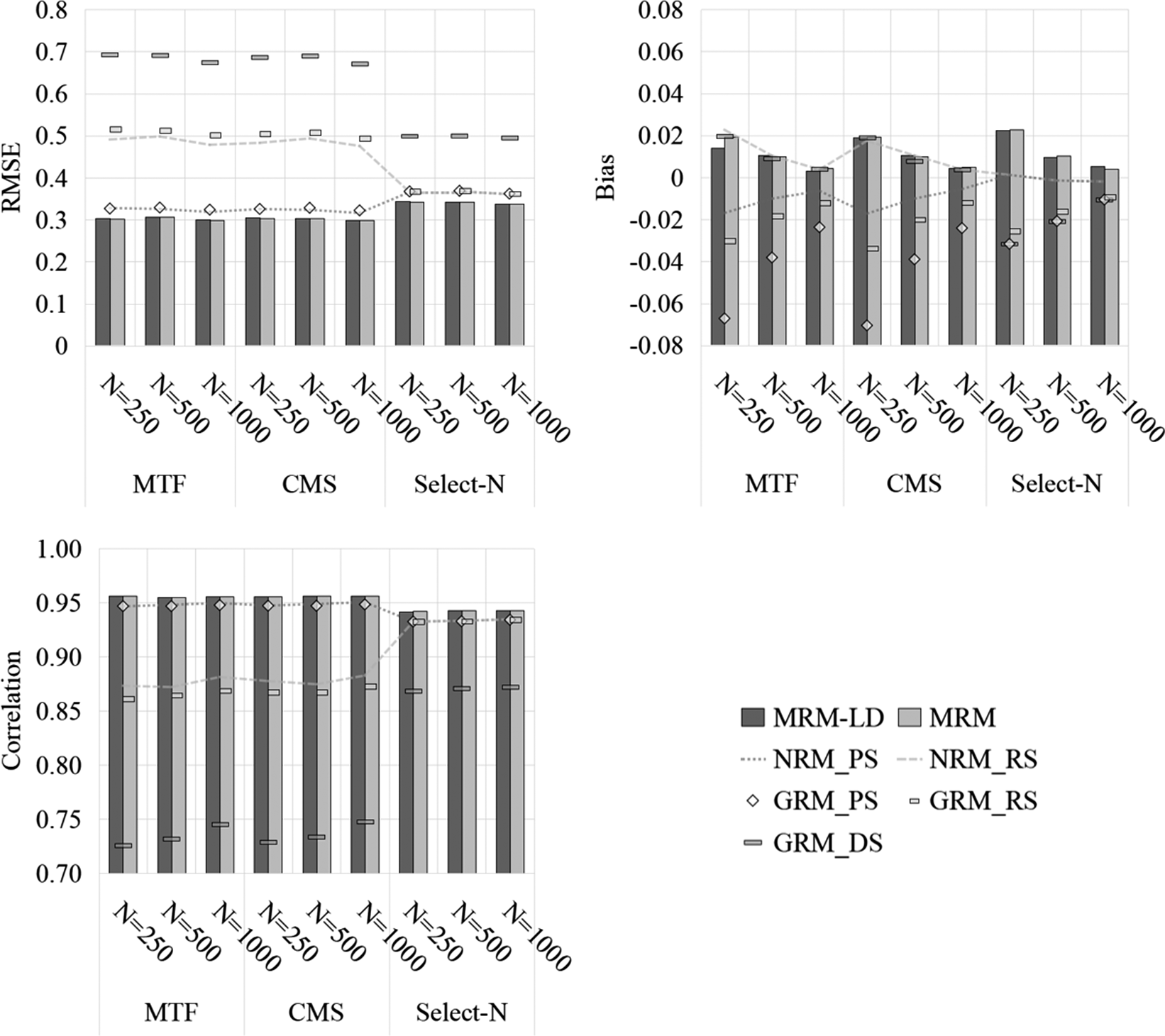

As shown in Figures 11–13, the MRM-LD consistently achieved the highest estimation accuracy for person parameter

![]() ${\theta}_i$

, closely followed by MRM. The overall ranking of accuracy was MRM-LD > MRM > GRMPS/NRMPS > GRMRS/NRMRS > GRMDS. The MRM-LD reduced RMSE by 4.4%—12.2% compared to GRMPS/NRMPS; 5.8%—50.8% compared to GRMRS/NRMRS; and 21.4%—65.1% compared to GRMDS. This pattern was corroborated by Pearson correlation results (see Supplementary Tables S11 and S12), where MRM-LD showed the highest values (0.901–0.972), followed by MRM (0.875–0.971). In contrast, GRMRS (0.716–0.959) and NRMRS (0.751–0.960) showed substantially lower correlations, while GRMDS had the lowest (0.345–0.900). In terms of item types, MTF and CMS items yielded slightly higher accuracy than select-N items. Estimation accuracy also improved with longer tests and a greater number of options. Although sample size minimally affected RMSE but did reduce bias. Notably, even with limited test length (e.g., J = 5), both MRM-LD and MRM maintained high accuracy (RMSE <0.5) and strong correlations (>0.88).

${\theta}_i$

, closely followed by MRM. The overall ranking of accuracy was MRM-LD > MRM > GRMPS/NRMPS > GRMRS/NRMRS > GRMDS. The MRM-LD reduced RMSE by 4.4%—12.2% compared to GRMPS/NRMPS; 5.8%—50.8% compared to GRMRS/NRMRS; and 21.4%—65.1% compared to GRMDS. This pattern was corroborated by Pearson correlation results (see Supplementary Tables S11 and S12), where MRM-LD showed the highest values (0.901–0.972), followed by MRM (0.875–0.971). In contrast, GRMRS (0.716–0.959) and NRMRS (0.751–0.960) showed substantially lower correlations, while GRMDS had the lowest (0.345–0.900). In terms of item types, MTF and CMS items yielded slightly higher accuracy than select-N items. Estimation accuracy also improved with longer tests and a greater number of options. Although sample size minimally affected RMSE but did reduce bias. Notably, even with limited test length (e.g., J = 5), both MRM-LD and MRM maintained high accuracy (RMSE <0.5) and strong correlations (>0.88).

Figure 11 Estimation accuracy of person parameter

![]() ${\theta}_i$

by various models in MTF tests.

${\theta}_i$

by various models in MTF tests.

Figure 12 Estimation accuracy of person parameter

![]() ${\theta}_i$

by various models in CMS tests.

${\theta}_i$

by various models in CMS tests.

Figure 13 Estimation accuracy of person parameter

![]() ${\theta}_i$

by various models in select-N tests.

${\theta}_i$

by various models in select-N tests.

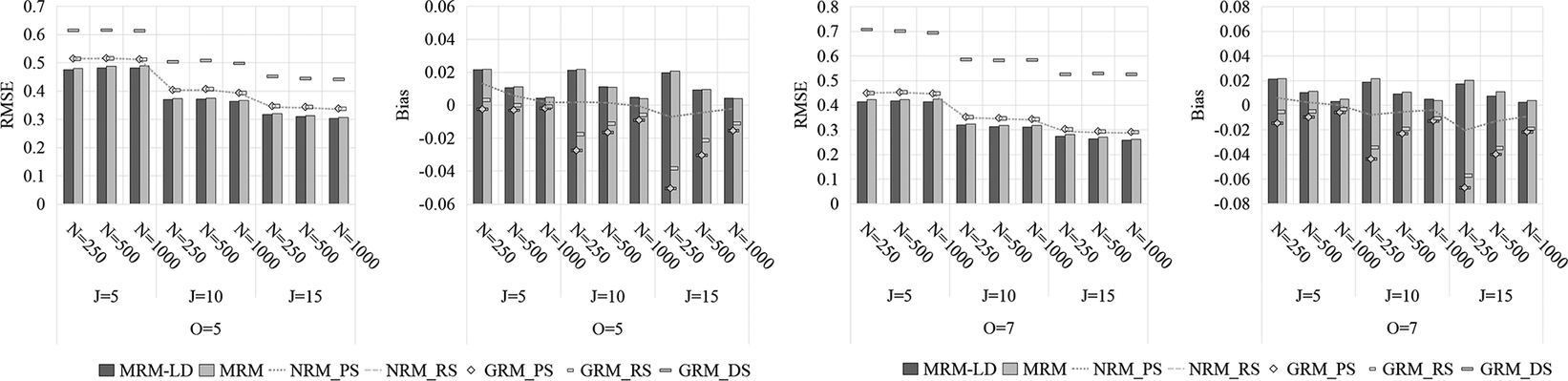

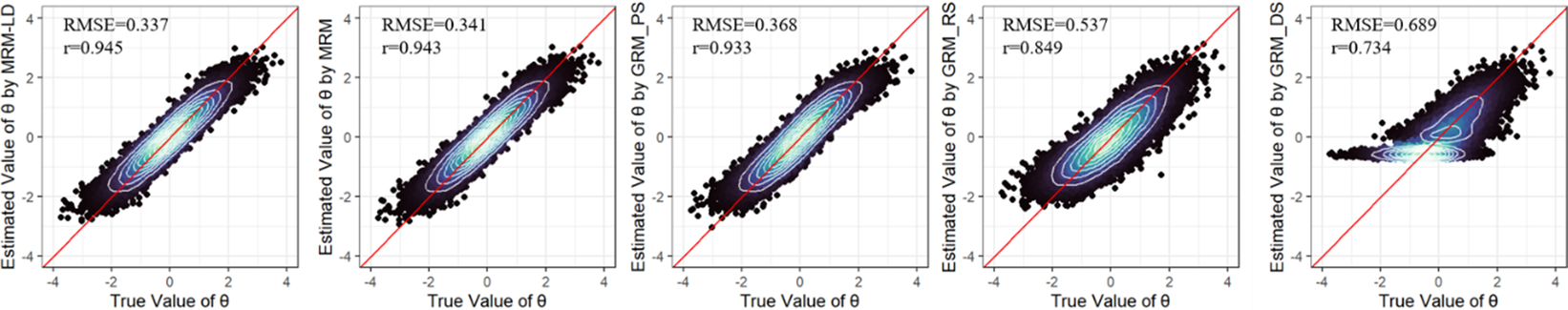

Taking the MTF condition with J = 10, O = 5, and N = 500 as an example, the scatterplots of true versus estimated

![]() ${\theta}_i$

in Figure 14 provide visual confirmation of these findings. GRMRS showed greater dispersion at high ability levels, while GRMDS failed to differentiate among low-ability respondents. Although GRMPS improved performance compared with GRMRS and GRMDS, the MRM and MRM-LD consistently exhibited the highest accuracy, minimizing estimation error and yielding the strongest correlations between estimated and true

${\theta}_i$

in Figure 14 provide visual confirmation of these findings. GRMRS showed greater dispersion at high ability levels, while GRMDS failed to differentiate among low-ability respondents. Although GRMPS improved performance compared with GRMRS and GRMDS, the MRM and MRM-LD consistently exhibited the highest accuracy, minimizing estimation error and yielding the strongest correlations between estimated and true

![]() ${\theta}_i$

parameters.

${\theta}_i$

parameters.

Figure 14 Scatter plots of the true and estimated values of

![]() ${\theta}_i$

for the condition: MTF, J = 10, O = 5, and N = 500.

${\theta}_i$

for the condition: MTF, J = 10, O = 5, and N = 500.

6.3 Simulation study 3

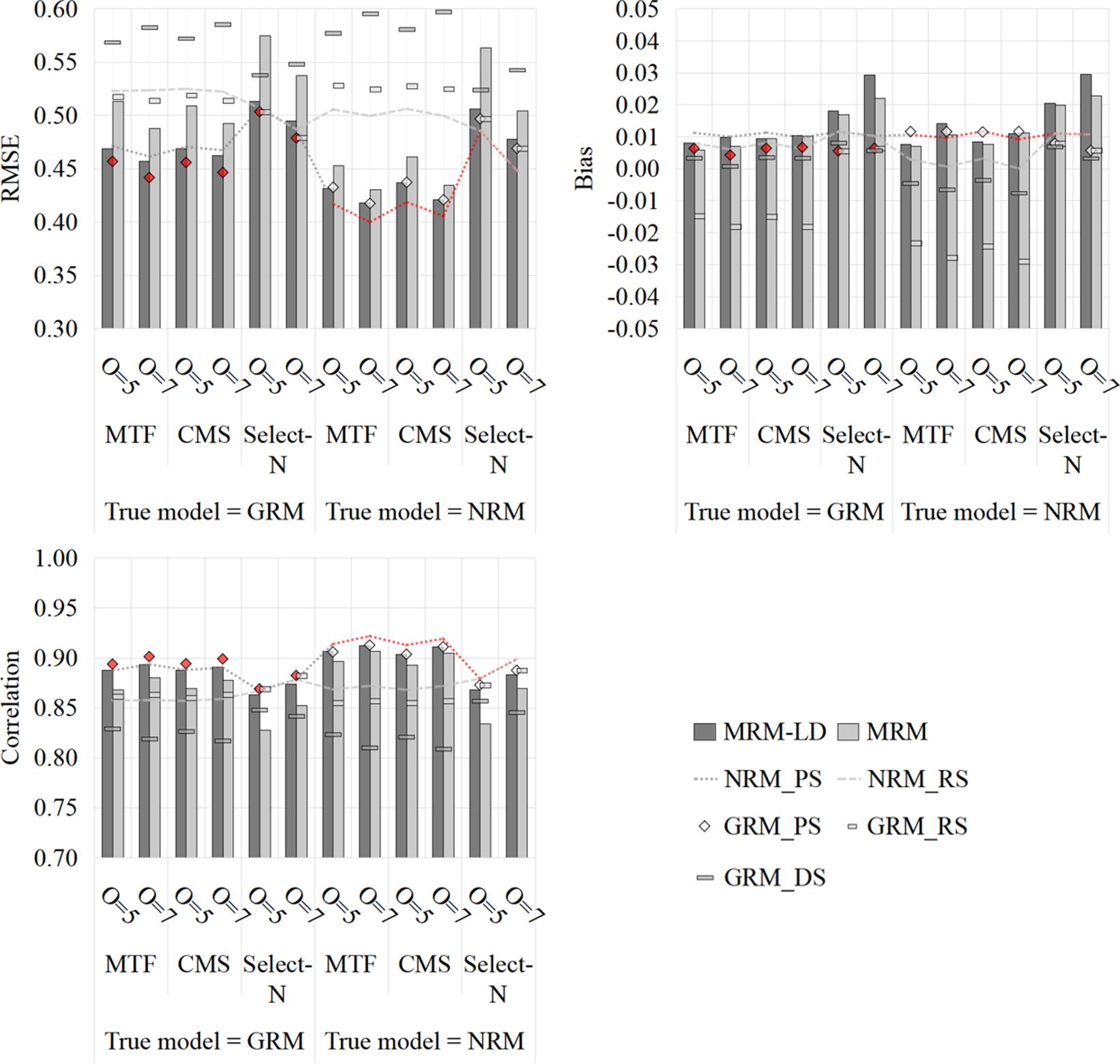

6.3.1 Design