Case presentation

An 11-year-old girl, diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy at age 8, presented with progressive heart failure manifested by exertional intolerance and severe left ventricular dilatation.

Comprehensive genetic and metabolic evaluations were conducted to elucidate the aetiology of the patient’s dilated cardiomyopathy, all of which yielded unremarkable results. Consequently, previous myocarditis was considered the most probable underlying cause. Furthermore, as part of the pre-transplant assessment, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a contrast enhancement defect within the interventricular wall, a finding consistent with myocarditis.

Despite optimised medical therapy including spironolactone, digoxin, enalapril, and carnitine, she developed inotrope-dependent end-stage heart failure. She was referred to our tertiary centre for advanced evaluation and listed for transplantation. At age 9.5 years, she underwent left ventricular assist device (HeartMate 3) implantation as a bridge to transplant. Her pre-implant ejection fraction was 15%, and her status was Pedimacs profile 2. In light of depressive manifestations, psychiatric follow-up was initiated as part of a comprehensive care plan, with the goals of monitoring mental health, preventing psychosocial complications, and reinforcing adherence to medical and lifestyle recommendations. Post-implantation, the patient was discharged and referred for regular multidisciplinary outpatient follow-up. Both pre- and post-implantation follow-up included structured education regarding device management, potential complications, and long-term care. In paediatric patients, the decision for device implantation was made through a multidisciplinary heart team consensus. Prior to implantation, both the patient and caregivers underwent not only clinical but also psychosocial assessment to evaluate their ability to adapt to the device. Despite this comprehensive preparation and education, the patient subsequently attempted such an act, which should be highlighted.

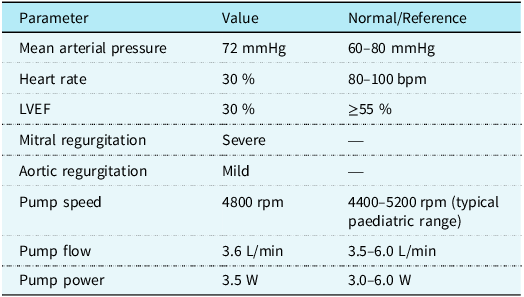

Despite regular education sessions regarding left ventricular assist device use, the patient entered the sea, resulting in driveline and battery exposure to sea water. Thirty minutes after immersion, alarms indicated imminent battery shutdown, and she was transferred to our emergency department. On admission, she was alert and haemodynamically stable, with a mean arterial pressure of 72 mmHg, heart rate 98 bpm, respiratory rate 26/min, and temperature 36 °C. Echocardiography showed left ventricular ejection fraction 30 %, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter 4.8 cm (z score + 1.79 SDS), severe mitral regurgitation, mild aortic regurgitation, and no right heart failure. Device interrogation revealed driveline and external battery moisture exposure. HeartMate 3 settings were flow 3.6 L/min at 4800 rpm, with power 3.5 W. (Table 1)

Table 1. Haemodynamic and device parameters at presentation

Haemodynamic and device performance parameters measured at initial presentation. The table summarises mean arterial pressure, heart rate, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), valvular findings, and HeartMate 3 LVAD pump metrics compared with reference paediatric ranges. The patient presented with reduced LVEF, severe mitral regurgitation, and mild aortic regurgitation. Pump parameters were within the expected range for paediatric support.

Given the risk of oxidation and future pump malfunction, urgent replacement of the battery and extracorporeal leads was planned. The patient was transferred to the PICU for closer monitoring and preparation for possible ECMO support. Radial arterial line and continuous ECG monitoring were established, and intubation equipment was prepared. Fifteen minutes before the procedure, intravenous dobutamine infusion at 5 mcg/kg/min was started to mitigate the risk of haemodynamic collapse.

An experienced cardiac surgeon performed the system controller and modular driveline exchange. During the brief 15-second interruption of left ventricular assist device function, the patient’s mean arterial pressure fell below 45 mmHg, and she developed presyncope despite inotropic support. After reconnection, the device function normalised immediately. Dobutamine infusion was continued for 2 hours, then weaned as the patient remained stable with normal blood gas parameters. She was discharged after reinforcement of education and psychosocial counselling.

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian.

Discussion

The use of continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices, particularly the HeartMate 3 (HM3), has significantly improved survival and quality of life in both adult and paediatric patients with advanced heart failure, especially when donor availability is limited. Reference Mehra, Uriel and Naka1–Reference Tume, Conway, Ryan, Philip, Fortkiewicz and Murray5 However, the complexity of device management necessitates strict adherence to lifestyle modifications and comprehensive caregiver education. One of the most critical restrictions for left ventricular assist device recipients is avoidance of water immersion, including swimming and bathing, as moisture exposure can damage external system components and the driveline, potentially leading to device malfunction or life-threatening complications such as pump failure and infection. Reference Belkin, Kagan, Labuhn, Pinney and Grinstein6,7 Seawater exposure carries significant risks, including bacterial contamination (notably Vibrio species) and accelerated corrosion of external device components. These factors may precipitate local infection, systemic sepsis, or irreversible hardware damage, necessitating urgent system replacement and antimicrobial prophylaxis. Reference Belkin, Kagan, Labuhn, Pinney and Grinstein6,7

The HM3 is a fully magnetically levitated centrifugal-flow pump with four unique features: a fully magnetically levitated rotor, a large blood flow pathway, an intrinsic pulsatility, and an intradevice operating system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. HeartMate 3 system components, including the pump housing, modular driveline, controller, and external batteries. The system utilises a fully magnetically levitated rotor minimising shear stress and thrombotic risk.

The Full MagLev technology (Abbott Corp., USA) minimises shear stress and compressive forces compared to hydrodynamic bearings, thereby reducing thrombotic complications. Reference Belkin, Kagan, Labuhn, Pinney and Grinstein6 Furthermore, the enlarged blood flow pathways prevent stasis and decrease activation of thrombogenic blood components, offering haemodynamic advantages over prior devices. Reference Belkin, Kagan, Labuhn, Pinney and Grinstein6

Despite these technical advancements, the management of paediatric left ventricular assist device patients remains particularly challenging. Psychosocial factors and issues of non-adherence can significantly impact clinical outcomes. In children and adolescents, activity restrictions may be especially difficult to maintain due to developmental drives toward independence, play, and peer interaction. Although light to moderate physical activity is encouraged to preserve functional capacity, swimming and other water-based activities are strictly contraindicated. Paediatric left ventricular assist device programme reports have emphasised that inadequate patient or caregiver education, or failure to comply with safety recommendations, may lead to preventable adverse events. 7

Device manufacturers explicitly contraindicate swimming, bathing, or full-body immersion because of risks of driveline corrosion, infection, and malfunction. Reference Belkin, Kagan, Labuhn, Pinney and Grinstein6,7 Only brief showering with waterproof protection is permitted. Despite comprehensive pre- and post-implantation education, our adolescent patient attempted swimming due to psychosocial stressors and family dynamics. This underscores the need for continuous reinforcement of education and integration of psychosocial support within left ventricular assist device programmes.

Our patient’s intolerance of even a 15-second interruption in pump function, despite an echocardiographic ejection fraction of 30%, underscores true left ventricular assist device dependency. Severe mitral regurgitation may cause echocardiographic ejection fraction to overestimate effective forward cardiac output. Reference Ön, Doğan, Tuncer, Engin and Özbaran8 To our knowledge, this is the first paediatric case report describing HeartMate 3 seawater exposure requiring emergent driveline and battery replacement. This highlights the importance of ongoing patient/family counselling, psychological support, and emergency preparedness in paediatric left ventricular assist device care.

In summary, this case illustrates the vulnerabilities of paediatric left ventricular assist device recipients and emphasises the importance of reinforced counselling strategies. Comprehensive pre- and post-implantation education, repeated reinforcement of safety precautions, and ongoing psychosocial support are critical in mitigating risk. Moreover, structured, paediatric-specific guidelines may help harmonise practices across centres and reduce the likelihood of hazardous behaviours. Finally, prevention of device-related complications in children requires a multidisciplinary approach that integrates not only cardiologists, left ventricular assist device coordinators, and nurses, but also psychologists and families. Future research should focus on developing standardised frameworks for paediatric left ventricular assist device activity counselling and safety monitoring as the use of HeartMate 3 expands in younger populations.