1. Introduction

The stability and laminar-to-turbulent transition of high-speed boundary layers have been extensively investigated in recent decades. The skin friction and heat flux can be escalated by several times after the transition is completed. As a result, the transition mechanism is of great significance. Physically, multiple processes can emerge during the instability and transition. From early to late stages, the physical processes may include the receptivity to external disturbances, transient growth, eigenmodal growth, parametric resonance and mode–mode interactions, breakdown to turbulence, etc. The specific transition path and involved process are dependent on the environmental disturbance level (Morkovin, Reshotko & Herbert Reference Morkovin, Reshotko and Herbert1994).

During the flight or in the quiet wind tunnel, the disturbance level tends to be relatively low. In this case, the long-distance eigenmodal amplification of small-amplitude disturbances is likely dominant in triggering the transition. Common boundary layer eigenmodes include the Tollmien–Schlichting mode in subsonic, the first mode in low supersonic, the Mack second mode in hypersonic boundary layers, etc. These modes are solvable from a local eigenvalue analysis. The terms ‘local’ and ‘global’ refer to the instability of the local profile and of the entire flow field, respectively (Huerre & Monkewitz Reference Huerre and Monkewitz1990). These local modes possess predominantly high growth rates of energy under certain conditions, and can be exponentially amplified (Mack Reference Mack1984; Fedorov Reference Fedorov2011). In contrast to the exponential growth, algebraic growth is also likely responsible for the transition. For instance, the eigenmodal growth can be bypassed, provided that the environment is sufficiently noisy. Another scenario is that the system is linearly stable by local normal-mode analysis, whereas it undergoes an evident algebraic growth from global analysis (Schmid Reference Schmid2007). The discrepancy is attributed to the fact that the global analysis can be based on the linearised Navier–Stokes (N–S) equation, which includes the non-normality nature of the operator. By contrast, a local analysis usually neglects this factor. From the perspective of local analysis, the growth of the convective instability is called ‘non-modal’ if the local normal-mode analysis reports no unstable solutions.

In the high-speed transition community, one of the issues under debate is the nose-tip bluntness effect, which may be linked with the non-modal growth discussed above. This bluntness effect arises as the leading edge of the vehicle needs to be blunted to mitigate aerodynamic heating. Historically, Stetson discovered the ‘transition reversal’ phenomenon due to the bluntness effect in different tunnel facilities (Stetson & Rushton Reference Stetson and Rushton1967; Stetson Reference Stetson1983). Later, this phenomenon has been widely reported by transition measurements over blunt flat plates (Lysenko Reference Lysenko1990; Borovoy et al. Reference Borovoy, Radchenko, Aleksandrov and Mosharov2022), blunt cones (Softley, Graber & Zempel Reference Softley, Graber and Zempel1969; Ericsson Reference Ericsson1988; Zanchetta Reference Zanchetta1996; Aleksandrova et al. Reference Aleksandrova, Novikov, Utyuzhnikov and Fedorov2014; Marineau et al. Reference Marineau, Moraru, Lewis, Norris, Lafferty, Wagnild and Smith2014; Paredes et al. Reference Paredes, Choudhari, Li, Jewell, Kimmel, Marineau and Grossir2019) and ogive cylinders (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Oddo, Komives, Reeder, Borg and Jewell2022) for a wide range of Mach numbers. To be specific, as the nose-tip bluntness (normally characterised by the radius) is gradually increased, the transition onset or end locations can be firstly delayed and then moved forward. These two distinct regimes, called the small-bluntness regime and the large-bluntness regime, display a reversal trend. The trend is usually observable in a

![]() $Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

$Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

![]() $Re_{\textit {t}}$

or

$Re_{\textit {t}}$

or

![]() $Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

$Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

![]() $Re_{\textit {T}}$

plot. Here,

$Re_{\textit {T}}$

plot. Here,

![]() $Re_{\textit {R}}$

,

$Re_{\textit {R}}$

,

![]() $Re_{\textit {t}}$

and

$Re_{\textit {t}}$

and

![]() $Re_{\textit {T}}$

refer to the Reynolds numbers based on the nose-tip radius, the transition onset location and the transition end location, respectively. More detailed introductions to the stabilisation effect of the entropy layer in the small-bluntness regime and to the poorly understood large-bluntness regime can be found in Part 1 (Guo, Hao & Wen Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). In addition to experimental research, numerical efforts on the receptivity (Zhong & Ma Reference Zhong and Ma2002, Reference Zhong and Ma2006; Kara, Balakumar & Kandil Reference Kara, Balakumar and Kandil2011; Balakumar & Kegerise Reference Balakumar and Kegerise2015; Balakumar & Chou Reference Balakumar and Chou2018; He & Zhong Reference He and Zhong2021; Ba, Niu & Su Reference Ba, Niu and Su2023) and the nonlinear instability stage (Paredes, Choudhari & Li Reference Paredes, Choudhari and Li2020; Hartman, Hader & Fasel Reference Hartman, Hader and Fasel2021; Goparaju & Gaitonde Reference Goparaju and Gaitonde2022; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Schuabb, Duan, Paredes and Choudhari2022; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Li, Guo, Liu and Tong2023) were also reviewed.

$Re_{\textit {T}}$

refer to the Reynolds numbers based on the nose-tip radius, the transition onset location and the transition end location, respectively. More detailed introductions to the stabilisation effect of the entropy layer in the small-bluntness regime and to the poorly understood large-bluntness regime can be found in Part 1 (Guo, Hao & Wen Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). In addition to experimental research, numerical efforts on the receptivity (Zhong & Ma Reference Zhong and Ma2002, Reference Zhong and Ma2006; Kara, Balakumar & Kandil Reference Kara, Balakumar and Kandil2011; Balakumar & Kegerise Reference Balakumar and Kegerise2015; Balakumar & Chou Reference Balakumar and Chou2018; He & Zhong Reference He and Zhong2021; Ba, Niu & Su Reference Ba, Niu and Su2023) and the nonlinear instability stage (Paredes, Choudhari & Li Reference Paredes, Choudhari and Li2020; Hartman, Hader & Fasel Reference Hartman, Hader and Fasel2021; Goparaju & Gaitonde Reference Goparaju and Gaitonde2022; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Schuabb, Duan, Paredes and Choudhari2022; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Li, Guo, Liu and Tong2023) were also reviewed.

Some of the 3-D simulation work can capture the flow structures that qualitatively resembled the experimental image (Hartman et al. Reference Hartman, Hader and Fasel2021; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Schuabb, Duan, Paredes and Choudhari2022). Nonetheless, no numerical simulation replicated the transition reversal phenomenon that agreed with the experiment. Recently, Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025) simulated the complete transition to turbulence over a blunt plate with varying nose-tip radii. The authors applied three-dimensional (3-D) broadband slow acoustic perturbations in front of the bow shock to trigger the instability and transition at Mach 5. A good agreement with the experimental

![]() $Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

$Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

![]() $Re_{\textit {t}}$

curve was achieved for the first time, which manifested the transition reversal.

$Re_{\textit {t}}$

curve was achieved for the first time, which manifested the transition reversal.

As a continuation question of Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025) where acoustic perturbations were utilised, the response of the flow over a largely blunted body to various types of free-stream disturbances merits an investigation. Basically, there are fundamental types of disturbances in the uniform free stream, namely slow/fast acoustic waves, vortical waves and entropy waves (Kovasznay Reference Kovasznay1953). They are independent solutions when the perturbation amplitude is small to allow the linearisation of the governing equation. Over configurations such as flat plates, wedges and cones, the instability waves in boundary layers are three to five times more susceptible to slow acoustic waves than fast acoustic, vorticity and entropy waves (Balakumar & Kegerise Reference Balakumar and Kegerise2015; He & Zhong Reference He and Zhong2022). Numerical and experimental studies have revealed that the slow acoustic wave dominates the environment of noisy hypersonic tunnel facilities (Laufer Reference Laufer1961; Schneider Reference Schneider2001; Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Schülein, Petervari, Hannemann, Ali, Cerminara and Sandham2018). Recently, Zhao & Dong (Reference Zhao and Dong2025) examined the receptivity of non-modal instabilities to free-stream perturbations over a blunt wedge. The work was based on the shock-fitting harmonic linearised Navier–Stokes (HLNS) equation. They demonstrated that the linear response is more susceptible to acoustic and entropic disturbances than the vortical counterpart. Their focus is the receptivity and instability stages rather than the transitional one.

What remains to be explored is how the laminar–turbulent transition responds to various free-stream disturbances in the large-bluntness regime based on the following reasons. First, a sufficiently blunted leading edge is frequently encountered over a hypersonic vehicle, whereas the corresponding transition mechanism in the large-bluntness regime is scarcely recorded in literature. The sensitivity of the transition to the disturbance form is of interest. The transition dominated by non-modal instabilities may be different from conventional modal scenarios. Second, the transition onset Reynolds number during the flight test (

![]() $\sim O(10^7)$

) is usually larger than that in the conventional or quiet wind tunnel (

$\sim O(10^7)$

) is usually larger than that in the conventional or quiet wind tunnel (

![]() $\sim O(10^6)$

) (Lee & Jiang Reference Lee and Jiang2019; Tu et al. Reference Tu, Chen, Yuan, Yang, Duan, Yang, Duan, Chen, Wan and Xiang2021), regardless of the configuration. An alternative cause is the varied pronounced form of environmental disturbances, which may be the vortical disturbance in the atmospheric environment and the radiated acoustic wave in the tunnel. The flight/ground discrepancy is closely related to the disturbance type. In fact, during the revision of Part 1 (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025), the author has continued the consideration of the disturbance-form effect and the flight/ground discrepancy inspired by the feedback of reviewers.

$\sim O(10^6)$

) (Lee & Jiang Reference Lee and Jiang2019; Tu et al. Reference Tu, Chen, Yuan, Yang, Duan, Yang, Duan, Chen, Wan and Xiang2021), regardless of the configuration. An alternative cause is the varied pronounced form of environmental disturbances, which may be the vortical disturbance in the atmospheric environment and the radiated acoustic wave in the tunnel. The flight/ground discrepancy is closely related to the disturbance type. In fact, during the revision of Part 1 (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025), the author has continued the consideration of the disturbance-form effect and the flight/ground discrepancy inspired by the feedback of reviewers.

Following the above note, the efficiency in inducing the laminar–turbulent transition by different fundamental disturbances will be evaluated by 3-D direct numerical simulation (DNS). To this end, the strength of different free-stream fundamental disturbances will be set to be identical based on the criterion of Zhong (Reference Zhong2001), and then 3-D broadband disturbances will be constructed by superimposition. A systematic analysis will be made to elucidate the physical cause of different transitional progress. The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 describes the physical problem and free-stream condition. Section 3 gives the numerical method, the detailed construction of free-stream disturbances and the case set-up. Section 4 displays the solution of fundamental free-stream waves in a wide parameter space. Section 5 gives the LST results. Section 6 shows the DNS results and discussions. Section 7 provides a remark on a recent similar study. Section 8 and the appendixes present the conclusion and other relevant information, respectively.

2. Problem description

A flat-plate model with a cylindrically blunted leading edge is studied. The benchmark experiment was performed in a Ludwig wind tunnel UT-1 M by Borovoy et al. (Reference Borovoy, Radchenko, Aleksandrov and Mosharov2022) at Mach 5. Figure 1(a) depicts the free-stream condition as well as the comparison of the data trend in the

![]() $Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

$Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

![]() $Re_{\textit {t}}$

plot between the experiment and the DNS of Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). The relevant symbols are: dimensionless nose-tip radius

$Re_{\textit {t}}$

plot between the experiment and the DNS of Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). The relevant symbols are: dimensionless nose-tip radius

![]() $R$

, Reynolds number based on the nose-tip radius

$R$

, Reynolds number based on the nose-tip radius

![]() $Re_{\textit {R}}$

, Reynolds number based on the transition onset location

$Re_{\textit {R}}$

, Reynolds number based on the transition onset location

![]() $Re_{\textit {t}}$

, Mach number

$Re_{\textit {t}}$

, Mach number

![]() $M_{\infty }$

, total temperature

$M_{\infty }$

, total temperature

![]() $T^{\ast }_{0}$

, static temperature

$T^{\ast }_{0}$

, static temperature

![]() $T^{\ast }_{\infty }$

, wall temperature

$T^{\ast }_{\infty }$

, wall temperature

![]() $T^{\ast }_{{w}}$

and unit Reynolds number

$T^{\ast }_{{w}}$

and unit Reynolds number

![]() $Re^{\ast }_{\infty }$

. The asterisk represents dimensional quantities. The subscript ‘

$Re^{\ast }_{\infty }$

. The asterisk represents dimensional quantities. The subscript ‘

![]() $\infty$

’ refers to the free-stream quantity. The subscript ‘

$\infty$

’ refers to the free-stream quantity. The subscript ‘

![]() $\textit {w}$

’ represents the quantity at the wall. The primitive variables are non-dimensionalised by the corresponding free-stream quantities, except that the pressure

$\textit {w}$

’ represents the quantity at the wall. The primitive variables are non-dimensionalised by the corresponding free-stream quantities, except that the pressure

![]() $p$

is by the free stream

$p$

is by the free stream

![]() $\rho ^{\ast }_{\infty } {u}^{\ast 2}_{\infty }$

. The symbols

$\rho ^{\ast }_{\infty } {u}^{\ast 2}_{\infty }$

. The symbols

![]() $\rho$

and

$\rho$

and

![]() $u$

represent the density and the streamwise velocity, respectively. The reference length scale for non-dimensionalisation is

$u$

represent the density and the streamwise velocity, respectively. The reference length scale for non-dimensionalisation is

![]() $L^{\ast }_{\textit {ref}}=1$

mm, which is in the same order of magnitude as the thickness of the downstream laminar boundary layer .

$L^{\ast }_{\textit {ref}}=1$

mm, which is in the same order of magnitude as the thickness of the downstream laminar boundary layer .

Figure 1(a) illustrates that our recent DNS favourably reproduced the transition reversal trend of the experimental data. Given

![]() $Re^{\ast }_{\infty } =6\times 10^7$

m

$Re^{\ast }_{\infty } =6\times 10^7$

m

![]() $^{-1}$

, the critical nose-tip radius for transition reversal is around

$^{-1}$

, the critical nose-tip radius for transition reversal is around

![]() $R_{\textit {critical}}^{\ast }=1.19$

mm. In this paper the radius

$R_{\textit {critical}}^{\ast }=1.19$

mm. In this paper the radius

![]() $R^{\ast }=3$

mm, referred to as ‘R3’ in figure 1(a), is selected to conduct further investigations in the large-bluntness regime. Figure 1(b) provides a schematic drawing of the simulated problem. The Cartesian coordinate system (

$R^{\ast }=3$

mm, referred to as ‘R3’ in figure 1(a), is selected to conduct further investigations in the large-bluntness regime. Figure 1(b) provides a schematic drawing of the simulated problem. The Cartesian coordinate system (

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

,

$y$

,

![]() $z$

), corresponding to streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise velocities (

$z$

), corresponding to streamwise, wall-normal and spanwise velocities (

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

,

$v$

,

![]() $w$

), and the orthogonal body-fitted system (

$w$

), and the orthogonal body-fitted system (

![]() $\xi$

,

$\xi$

,

![]() $\eta$

,

$\eta$

,

![]() $z$

) are constructed with the origin at the centre of the cylindrical nose.

$z$

) are constructed with the origin at the centre of the cylindrical nose.

Figure 1. (a) Comparison of experimental and DNS data trends in the

![]() $Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

$Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

![]() $Re_{\textit {t}}$

plot and (b) the simulation strategy of the flow over a blunt plate (not to scale) (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025).

$Re_{\textit {t}}$

plot and (b) the simulation strategy of the flow over a blunt plate (not to scale) (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025).

Figure 2. Mach number contour of the laminar flow with nose-tip radius

![]() $R=3$

. Solid and dashed lines in the left panel represent the edges of the entropy layer and the boundary layer, respectively. The solid line in the right panel represents the sonic line near the nose.

$R=3$

. Solid and dashed lines in the left panel represent the edges of the entropy layer and the boundary layer, respectively. The solid line in the right panel represents the sonic line near the nose.

The Mach number contour of the two-dimensional (2-D) laminar flow is shown in figure 2 for R3. The edge positions of boundary and entropy layers are marked by the dashed and solid lines, respectively, which are defined by the criteria of Paredes et al. (Reference Paredes, Choudhari, Li, Jewell, Kimmel, Marineau and Grossir2019) and specified in Part 1 (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). As shown in figure 2, the boundary layer is entirely covered by the thick entropy layer. In other words, entropy swallowing does not appear in the blunt-plate flow, which is different from the blunt-cone flow. Hence, the pronounced entropy-layer effect is persistent along the plate, enabling the stabilisation of normal-mode instabilities.

3. Methodology, physical model and case description

The numerical set-up in Part 1 (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025) is inherited, since a good agreement in the

![]() $Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

$Re_{\textit {R}}$

–

![]() $Re_{\textit {t}}$

correlation has been reached with the experiment and mesh convergence of the instability evolution has been achieved. It is believed that useful and reliable insights can be provided via the same methodology as Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). Note that the stability analysis in Part 1 has shown that first and second modes are rendered stabilised by leading-edge bluntness with

$Re_{\textit {t}}$

correlation has been reached with the experiment and mesh convergence of the instability evolution has been achieved. It is believed that useful and reliable insights can be provided via the same methodology as Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). Note that the stability analysis in Part 1 has shown that first and second modes are rendered stabilised by leading-edge bluntness with

![]() $R=3$

. This work only provides further discussions on the entropy-layer mode. What remains to be explored is the transitional characterisation subject to different fundamental free-stream waves, which will be done via comparative studies.

$R=3$

. This work only provides further discussions on the entropy-layer mode. What remains to be explored is the transitional characterisation subject to different fundamental free-stream waves, which will be done via comparative studies.

3.1. Direct numerical simulation

The 3-D compressible N–S equations are written in a dimensionless conservation form, i.e.

where

![]() $t$

denotes time,

$t$

denotes time,

![]() ${\boldsymbol{Q}} = (\rho , \rho u, \rho v, \rho w, \rho e)^{\text{T}}$

refers to the vector of conservative variables,

${\boldsymbol{Q}} = (\rho , \rho u, \rho v, \rho w, \rho e)^{\text{T}}$

refers to the vector of conservative variables,

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}$

,

$\boldsymbol{F}$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{G}$

and

$\boldsymbol{G}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{H}$

represent the vectors of inviscid fluxes, and

$\boldsymbol{H}$

represent the vectors of inviscid fluxes, and

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_v$

,

$\boldsymbol{F}_v$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{G}_v$

and

$\boldsymbol{G}_v$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{H}_v$

are the vectors of viscous fluxes. The symbol

$\boldsymbol{H}_v$

are the vectors of viscous fluxes. The symbol

![]() $e$

refers to the total energy per unit mass and the superscript ‘T’ represents matrix transpose. A calorically perfect gas (air) model is used with a constant specific heat ratio

$e$

refers to the total energy per unit mass and the superscript ‘T’ represents matrix transpose. A calorically perfect gas (air) model is used with a constant specific heat ratio

![]() $\gamma =1.4$

. Sutherland’s law is utilised to compute the dynamic viscosity

$\gamma =1.4$

. Sutherland’s law is utilised to compute the dynamic viscosity

![]() $\mu$

and the thermal conductivity

$\mu$

and the thermal conductivity

![]() $\kappa$

is calculated with a constant Prandtl number

$\kappa$

is calculated with a constant Prandtl number

![]() $\textit {Pr}=0.72$

. Direct simulations of the 2-D laminar base flow and the full 3-D transitional flow are conducted using a finite-volume-based solver (Hao, Wang & Lee Reference Hao, Wang and Lee2016; Hao & Wen Reference Hao and Wen2020), which has been well validated (Hao et al. Reference Hao, Fan, Cao and Wen2022; Guo, Hao & Wen Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023).

$\textit {Pr}=0.72$

. Direct simulations of the 2-D laminar base flow and the full 3-D transitional flow are conducted using a finite-volume-based solver (Hao, Wang & Lee Reference Hao, Wang and Lee2016; Hao & Wen Reference Hao and Wen2020), which has been well validated (Hao et al. Reference Hao, Fan, Cao and Wen2022; Guo, Hao & Wen Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2023).

With regard to the mesh and numerical method, the structured mesh is iteratively designed to align with the shock of the steady laminar flow. A shock-capturing method is applied to solve the 2-D and 3-D problems. The inviscid flux is calculated by the seventh-order upwind scheme in the smooth region without the shock or away from the nose-tip region (

![]() $x\leqslant 0$

), while by a second-order MUSCL scheme in the remaining region. Time-accurate marching is implemented by the third-order Runge–Kutta method. More details about the numerical method and boundary condition can be found in Part 1 (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025).

$x\leqslant 0$

), while by a second-order MUSCL scheme in the remaining region. Time-accurate marching is implemented by the third-order Runge–Kutta method. More details about the numerical method and boundary condition can be found in Part 1 (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025).

3.2. Fundamental incident waves

To mimic a real-life environment, broadband perturbations are to be added on the far-field boundary in front of the shock. All the fundamental solutions in the free stream will be considered, namely the slow/fast acoustic wave, the vortical wave and the entropic wave. Multiple solutions will be superimposed to constitute the numerical perturbation in DNS. Before discussing the summed numerical forcing, it is necessary to elaborate the fundamental solutions of the free-stream waves.

Figure 3. Schematic drawing of the placed model and the radiated acoustic wave from the tunnel wall (not to scale). Red arrows: the wavenumber vector of the slow acoustic wave.

As shown in figure 3, the eddy sources in the boundary layer over the two-sided tunnel wall can radiate acoustic waves into the main stream. The wave front is assumed to be planar, since the averaged wavelength of the field is far less than the distance from the wall to the measured position (Laufer Reference Laufer1961). The inclination angle of the wave front depends on the source velocity

![]() $u_s$

, and the limit is the Mach wave angle (Schilden & Schröder Reference Schilden and Schröder2019). Planar acoustic, vortical and entropic waves in the free stream, propagating in arbitrary directions, are in the form

$u_s$

, and the limit is the Mach wave angle (Schilden & Schröder Reference Schilden and Schröder2019). Planar acoustic, vortical and entropic waves in the free stream, propagating in arbitrary directions, are in the form

where

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\varPsi }} = { ( {\rho ,u,v,w,T,p})^{\textrm {T}}}$

is the vector of variables,

${\boldsymbol{\varPsi }} = { ( {\rho ,u,v,w,T,p})^{\textrm {T}}}$

is the vector of variables,

![]() $\alpha ,\kappa ,\beta \in \mathbb{R}$

are wavenumbers in the x, y and z directions, respectively,

$\alpha ,\kappa ,\beta \in \mathbb{R}$

are wavenumbers in the x, y and z directions, respectively,

![]() $\omega$

is the angular frequency and

$\omega$

is the angular frequency and

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}$

is the amplitude. In the present paper the hat ‘

$\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}$

is the amplitude. In the present paper the hat ‘

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{\cdot }}$

’ and prime `

$\hat {\boldsymbol{\cdot }}$

’ and prime `

![]() $^{\prime}$

’ represent the spectral domain and the time domain, respectively. For waves propagating in a far-field uniform medium, the wavenumber vector

$^{\prime}$

’ represent the spectral domain and the time domain, respectively. For waves propagating in a far-field uniform medium, the wavenumber vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{k}_{\infty }=(\alpha ,\kappa ,\beta)^{\text{T}}$

must satisfy the dispersion relation arising from the linearised Euler equation (Kinsler et al. Reference Kinsler, Frey, Coppens and Sanders2000; Cook & Nichols Reference Cook and Nichols2024)

$\boldsymbol{k}_{\infty }=(\alpha ,\kappa ,\beta)^{\text{T}}$

must satisfy the dispersion relation arising from the linearised Euler equation (Kinsler et al. Reference Kinsler, Frey, Coppens and Sanders2000; Cook & Nichols Reference Cook and Nichols2024)

where the plus/minus sign indicates the fast/acoustic wave and the overbar represents the time-averaged value. Note that the free-stream velocity is in the streamwise direction, i.e.

![]() $\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}_{\infty }=(1,0,0)^{\textrm {T}}$

. For purely convected vortical/entropic waves, the dispersion relation becomes

$\bar {\boldsymbol{u}}_{\infty }=(1,0,0)^{\textrm {T}}$

. For purely convected vortical/entropic waves, the dispersion relation becomes

The subscripts ‘

![]() $\textit {a},\textit {v},\textit {e}$

’ refer to acoustic, vortical and entropic disturbances, respectively. The oblique wave angle on the

$\textit {a},\textit {v},\textit {e}$

’ refer to acoustic, vortical and entropic disturbances, respectively. The oblique wave angle on the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $z$

plane and the angle of inclination on the

$z$

plane and the angle of inclination on the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $y$

plane are defined by

$y$

plane are defined by

respectively. The angle

![]() $\phi$

is also the angle with counterclockwise rotation from the

$\phi$

is also the angle with counterclockwise rotation from the

![]() $+x$

direction to the wavenumber vector.

$+x$

direction to the wavenumber vector.

With regard to acoustic waves, (3.3) yields

\begin{equation} \frac {\omega }{{{\alpha _{\textit {a}}}}} = 1 \pm \frac {\text{sgn}(\alpha _{\textit {a}})}{{{M_\infty }}}\sqrt {1 + {{\left ( {\frac {{{\kappa _{\textit {a}}}}}{{{\alpha _{\textit {a}}}}}} \right)}^2} + {{\left ( {\frac {{{\beta _{\textit {a}}}}}{{{\alpha _{\textit {a}}}}}} \right)}^2}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \frac {\omega }{{{\alpha _{\textit {a}}}}} = 1 \pm \frac {\text{sgn}(\alpha _{\textit {a}})}{{{M_\infty }}}\sqrt {1 + {{\left ( {\frac {{{\kappa _{\textit {a}}}}}{{{\alpha _{\textit {a}}}}}} \right)}^2} + {{\left ( {\frac {{{\beta _{\textit {a}}}}}{{{\alpha _{\textit {a}}}}}} \right)}^2}}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $\text{sgn}(\boldsymbol{\cdot })$

denotes the sign function. Combining (3.5) and (3.6) in turn yields

$\text{sgn}(\boldsymbol{\cdot })$

denotes the sign function. Combining (3.5) and (3.6) in turn yields

A special case is for a zero angle of incidence, where

![]() $\kappa _{\textit {a}}=\phi _{\textit {a}}=0$

. Hereupon, (3.3) gives rise to

$\kappa _{\textit {a}}=\phi _{\textit {a}}=0$

. Hereupon, (3.3) gives rise to

Similarly, with

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}}=0$

, (3.3) yields what Egorov, Sudakov & Fedorov (Reference Egorov, Sudakov and Fedorov2006) have shown:

$\theta _{\textit {a}}=0$

, (3.3) yields what Egorov, Sudakov & Fedorov (Reference Egorov, Sudakov and Fedorov2006) have shown:

To avoid ambiguity, a note is given on the range of

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}$

, which is discussed in

$\phi _{\textit {a}}$

, which is discussed in

![]() $[-180^{\circ },180^{\circ }]$

. In the terminology framework of Duan et al. (Reference Duan2019), the angle of inclination of the radiated acoustic wave from the lower-side wall ranges from

$[-180^{\circ },180^{\circ }]$

. In the terminology framework of Duan et al. (Reference Duan2019), the angle of inclination of the radiated acoustic wave from the lower-side wall ranges from

![]() $0^{\circ }$

to

$0^{\circ }$

to

![]() $180^{\circ }$

, where the two limits represent the fast and slow acoustic waves, respectively. Moreover, the mean angle of inclination is around

$180^{\circ }$

, where the two limits represent the fast and slow acoustic waves, respectively. Moreover, the mean angle of inclination is around

![]() $120^{\circ }$

based on the DNS of turbulent boundary layers over the nozzle wall. By contrast, Schilden & Schröder (Reference Schilden and Schröder2019) claimed that, for the same situation, the inclination angle between the stream direction and the wavenumber vector should be no more than

$120^{\circ }$

based on the DNS of turbulent boundary layers over the nozzle wall. By contrast, Schilden & Schröder (Reference Schilden and Schröder2019) claimed that, for the same situation, the inclination angle between the stream direction and the wavenumber vector should be no more than

![]() $90^{\circ }$

for slow acoustic waves, as shown in figure 3. To clarify this issue, first, it is stipulated that

$90^{\circ }$

for slow acoustic waves, as shown in figure 3. To clarify this issue, first, it is stipulated that

![]() $\omega \gt 0$

, since a negative value of

$\omega \gt 0$

, since a negative value of

![]() $\omega$

would lead to ambiguity in the definitions of fast and slow acoustic waves (Huang & Wang Reference Huang and Wang2019). For slow acoustic waves where the negative sign is taken in (3.9),

$\omega$

would lead to ambiguity in the definitions of fast and slow acoustic waves (Huang & Wang Reference Huang and Wang2019). For slow acoustic waves where the negative sign is taken in (3.9),

![]() $|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|\gt 0$

and

$|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|\gt 0$

and

![]() $\omega \gt 0$

indicate that

$\omega \gt 0$

indicate that

![]() $|\phi _{\textit {a}} |\lt \arccos (1/M_{\infty })\approx 78.46^\circ \lt 90^\circ$

. This agreement with Schilden & Schröder (Reference Schilden and Schröder2019) starts from the wave ansatz in (3.2), i.e.

$|\phi _{\textit {a}} |\lt \arccos (1/M_{\infty })\approx 78.46^\circ \lt 90^\circ$

. This agreement with Schilden & Schröder (Reference Schilden and Schröder2019) starts from the wave ansatz in (3.2), i.e.

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{\varPsi }}_{\textit {a}} \propto \exp ( {\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }{\boldsymbol{X}} - {\textrm {i}}\omega t)$

, where

$\hat {\boldsymbol{\varPsi }}_{\textit {a}} \propto \exp ( {\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }{\boldsymbol{X}} - {\textrm {i}}\omega t)$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{X}$

is the coordinate vector. Alternatively, the left-running wave can have the form

$\boldsymbol{X}$

is the coordinate vector. Alternatively, the left-running wave can have the form

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{\varPsi }}_{\textit {a}} \propto \exp ( {\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }{\boldsymbol{X}} + {\textrm {i}}\omega t)$

, and accordingly the dispersion relation is changed to satisfy the linearised Euler equation. Finally, (3.9) becomes

$\hat {\boldsymbol{\varPsi }}_{\textit {a}} \propto \exp ( {\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }{\boldsymbol{X}} + {\textrm {i}}\omega t)$

, and accordingly the dispersion relation is changed to satisfy the linearised Euler equation. Finally, (3.9) becomes

![]() $|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|=\omega /(\mp 1/M_{\infty }-\cos {\tilde {\phi }_{\textit {a}}})$

. In this case,

$|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|=\omega /(\mp 1/M_{\infty }-\cos {\tilde {\phi }_{\textit {a}}})$

. In this case,

![]() $\tilde {\phi }_{\textit {a}}$

can exceed

$\tilde {\phi }_{\textit {a}}$

can exceed

![]() $90^\circ$

for slow acoustic waves. To keep consistent with Schilden & Schröder (Reference Schilden and Schröder2019),

$90^\circ$

for slow acoustic waves. To keep consistent with Schilden & Schröder (Reference Schilden and Schröder2019),

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{\varPsi }}_{\textit {a}} \propto \exp ( {\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }{\boldsymbol{X}} - {\textrm {i}}\omega t)$

is assumed to hold throughout this paper. In this case, for slow acoustic waves, one has

$\hat {\boldsymbol{\varPsi }}_{\textit {a}} \propto \exp ( {\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}}\boldsymbol{\cdot }{\boldsymbol{X}} - {\textrm {i}}\omega t)$

is assumed to hold throughout this paper. In this case, for slow acoustic waves, one has

![]() $|\phi _{\textit {a}} |\lt 90^\circ$

if

$|\phi _{\textit {a}} |\lt 90^\circ$

if

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}} =0$

and, similarly from (3.8),

$\theta _{\textit {a}} =0$

and, similarly from (3.8),

![]() $|\theta _{\textit {a}} |\lt 90^\circ$

if

$|\theta _{\textit {a}} |\lt 90^\circ$

if

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}} =0$

.

$\phi _{\textit {a}} =0$

.

For fast acoustic waves, it can be proven that the

![]() $x$

component of the direction of energy propagation, i.e. the

$x$

component of the direction of energy propagation, i.e. the

![]() $x$

component of the group velocity

$x$

component of the group velocity

![]() $\partial \omega /\partial \boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}$

, is equal to

$\partial \omega /\partial \boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}$

, is equal to

![]() $(M_{\infty }|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|-|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|/M_{\infty }+\omega)/(M_{\infty }|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|)$

. Apparently, the component is always positive for supersonic flows. Hence, the streamwise direction of energy propagation is always pointing to downstream for fast acoustic waves, regardless of the direction of the phase velocity

$(M_{\infty }|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|-|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|/M_{\infty }+\omega)/(M_{\infty }|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|)$

. Apparently, the component is always positive for supersonic flows. Hence, the streamwise direction of energy propagation is always pointing to downstream for fast acoustic waves, regardless of the direction of the phase velocity

![]() $\omega /\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}$

. Regarding the slow acoustic waves radiated from the lower wall in figure 3, the

$\omega /\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}$

. Regarding the slow acoustic waves radiated from the lower wall in figure 3, the

![]() $y$

component of the group velocity equals

$y$

component of the group velocity equals

![]() $-\kappa _{\textit {a}}/(M_{\infty }|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|)$

, which needs to be positive to propagate energy away from the lower wall. As a result, for the radiated slow acoustic waves,

$-\kappa _{\textit {a}}/(M_{\infty }|\boldsymbol{k}_{{\infty },\textit {a}}|)$

, which needs to be positive to propagate energy away from the lower wall. As a result, for the radiated slow acoustic waves,

![]() $\kappa _{\textit {a}}\lt 0$

and, thus,

$\kappa _{\textit {a}}\lt 0$

and, thus,

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}\lt 0$

for the lower wall, while

$\phi _{\textit {a}}\lt 0$

for the lower wall, while

![]() $\kappa _{\textit {a}}\gt 0$

and, thus,

$\kappa _{\textit {a}}\gt 0$

and, thus,

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}\gt 0$

for the upper wall. This justifies the direction of the wavenumber vector in figure 3. As shown in figure 3, a positive/negative

$\phi _{\textit {a}}\gt 0$

for the upper wall. This justifies the direction of the wavenumber vector in figure 3. As shown in figure 3, a positive/negative

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}$

signifies that the disturbance source is above/below the test model. In the following DNS, the disturbance source is above the blunt flat plate. In this case,

$\phi _{\textit {a}}$

signifies that the disturbance source is above/below the test model. In the following DNS, the disturbance source is above the blunt flat plate. In this case,

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}\in [0,78.46^\circ)$

for slow acoustic waves if

$\phi _{\textit {a}}\in [0,78.46^\circ)$

for slow acoustic waves if

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}}=0^\circ$

, and

$\theta _{\textit {a}}=0^\circ$

, and

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}=0$

is a limit that neglects the effect of angle of incidence.

$\phi _{\textit {a}}=0$

is a limit that neglects the effect of angle of incidence.

In this paper the angle of incidence

![]() $\phi$

is assumed to be a specific constant for each type of fundamental waves. Next, the effect of a non-zero angle of incidence will be examined for the acoustic wave. According to the linear regression of experimental noise data in a supersonic wind tunnel (Laufer Reference Laufer1961; Schilden & Schröder Reference Schilden and Schröder2019), the relation holds, i.e.

$\phi$

is assumed to be a specific constant for each type of fundamental waves. Next, the effect of a non-zero angle of incidence will be examined for the acoustic wave. According to the linear regression of experimental noise data in a supersonic wind tunnel (Laufer Reference Laufer1961; Schilden & Schröder Reference Schilden and Schröder2019), the relation holds, i.e.

which yields

![]() $|\phi _{\textit {a}}|=61.0^\circ$

at Mach 6 and

$|\phi _{\textit {a}}|=61.0^\circ$

at Mach 6 and

![]() $|\phi _{\textit {a}}|=61.7^\circ$

at Mach 5. The angles are close to the

$|\phi _{\textit {a}}|=61.7^\circ$

at Mach 5. The angles are close to the

![]() $60^\circ$

value of the radiated wave angle (Duan et al. Reference Duan2019), which is based on the DNS of turbulent boundary layers over the nozzle wall. To be realistic, the examined non-zero angle of incidence is taken as

$60^\circ$

value of the radiated wave angle (Duan et al. Reference Duan2019), which is based on the DNS of turbulent boundary layers over the nozzle wall. To be realistic, the examined non-zero angle of incidence is taken as

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}=60^\circ$

in the present work.

$\phi _{\textit {a}}=60^\circ$

in the present work.

To satisfy the linearised Euler equation, the amplitudes in (3.2) of the corresponding waves are

\begin{align} \begin{array}{l} \displaystyle {\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}_{\textit {a}}} \propto {\left ( {1, \pm \alpha _{\textit {a}}/({M_\infty }|k_{\infty ,\textit {a}}|),\pm \kappa _{\textit {a}}/({M_\infty }|k_{\infty ,\textit {a}}|),\pm \beta _{\textit {a}}/({M_\infty }|k_{\infty ,\textit {a}}|),\gamma - 1,1/{{M_\infty ^2}}} \right)^{\textrm {T}}},\\[2pt] \displaystyle {\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}_v} \propto {\left ( {0,-(\kappa _{\textit {v}}+\beta _{\textit {v}})/\alpha _{\textit {v}},1,1,0,0} \right)^{\textrm {T}}},\\[2pt] \displaystyle {\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}_e} \propto {\left ( { -1,0,0,0,1,0} \right)^{\textrm {T}}}, \end{array} \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{array}{l} \displaystyle {\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}_{\textit {a}}} \propto {\left ( {1, \pm \alpha _{\textit {a}}/({M_\infty }|k_{\infty ,\textit {a}}|),\pm \kappa _{\textit {a}}/({M_\infty }|k_{\infty ,\textit {a}}|),\pm \beta _{\textit {a}}/({M_\infty }|k_{\infty ,\textit {a}}|),\gamma - 1,1/{{M_\infty ^2}}} \right)^{\textrm {T}}},\\[2pt] \displaystyle {\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}_v} \propto {\left ( {0,-(\kappa _{\textit {v}}+\beta _{\textit {v}})/\alpha _{\textit {v}},1,1,0,0} \right)^{\textrm {T}}},\\[2pt] \displaystyle {\hat {\boldsymbol{q}}_e} \propto {\left ( { -1,0,0,0,1,0} \right)^{\textrm {T}}}, \end{array} \end{align}

where the plus/minus sign indicates the fast/acoustic wave. For vortical waves, the listed amplitude is one possible case to satisfy the dispersion relation

![]() $\alpha _{\textit {v}}\hat u_{\textit {v}}+\kappa _{\textit {v}}\hat v_{\textit {v}}+\beta _{\textit {v}}\hat w_{\textit {v}}=0$

. With the same reference quantities for non-dimensionalisation, (3.11) has been confirmed to reduce to the same form as Kamal, Lakebrink & Colonius (Reference Kamal, Lakebrink and Colonius2023). Under the present free-stream condition, precursor numerical tests of a uniform flow have also verified that the respective planar wave is propagating with the correct angles

$\alpha _{\textit {v}}\hat u_{\textit {v}}+\kappa _{\textit {v}}\hat v_{\textit {v}}+\beta _{\textit {v}}\hat w_{\textit {v}}=0$

. With the same reference quantities for non-dimensionalisation, (3.11) has been confirmed to reduce to the same form as Kamal, Lakebrink & Colonius (Reference Kamal, Lakebrink and Colonius2023). Under the present free-stream condition, precursor numerical tests of a uniform flow have also verified that the respective planar wave is propagating with the correct angles

![]() $\theta$

and

$\theta$

and

![]() $\phi$

, as shown in Appendix A.

$\phi$

, as shown in Appendix A.

Due to the homogeneity of the considered base flow in the

![]() $z$

direction, the obliquely propagating planar waves should be symmetrical on the

$z$

direction, the obliquely propagating planar waves should be symmetrical on the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $z$

plane. As a result, the physical fluctuation in the time domain should be the combination of a pair of obliquely propagating waves with opposite wave angles, i.e. the sum of the wave

$z$

plane. As a result, the physical fluctuation in the time domain should be the combination of a pair of obliquely propagating waves with opposite wave angles, i.e. the sum of the wave

![]() $(\alpha ,\kappa ,\pm \beta)^{\text{T}}$

. Mathematically, the fluctuation takes the form

$(\alpha ,\kappa ,\pm \beta)^{\text{T}}$

. Mathematically, the fluctuation takes the form

where ‘

![]() $\text{c.c.}$

’ means complex conjugate.

$\text{c.c.}$

’ means complex conjugate.

The present paper intends to investigate the transitional blunt-plate flow in response to different forms of disturbances. A comparative numerical study will be conducted under the same strength of different disturbances. Regarding the definition of ‘strength’, the receptivity study of Zhong (Reference Zhong2001) via DNS measured the strengths of free-stream acoustic, vortical and entropic waves by

![]() $\left | {{p^{\prime}_{\textit {a}}}} \right |M_\infty ^2,\left | {{v^{\prime}_{\textit {v}}}} \right |{M_\infty },\left | {{S^{\prime}_\infty }} \right |$

, respectively. The strengths are set equal to

$\left | {{p^{\prime}_{\textit {a}}}} \right |M_\infty ^2,\left | {{v^{\prime}_{\textit {v}}}} \right |{M_\infty },\left | {{S^{\prime}_\infty }} \right |$

, respectively. The strengths are set equal to

![]() $\epsilon {M_\infty }$

for all the three waves by Zhong to examine the response of the boundary layer. Here,

$\epsilon {M_\infty }$

for all the three waves by Zhong to examine the response of the boundary layer. Here,

![]() $S$

is entropy and

$S$

is entropy and

![]() $\epsilon$

is a small parameter. Note that substituting (3.11) into (3.12) yields the amplitudes superimposed by a pair of oblique waves. To keep the same strength for the three types of fundamental waves, the amplitudes in the time domain need to satisfy

$\epsilon$

is a small parameter. Note that substituting (3.11) into (3.12) yields the amplitudes superimposed by a pair of oblique waves. To keep the same strength for the three types of fundamental waves, the amplitudes in the time domain need to satisfy

\begin{align} \displaystyle {{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\prime}_{\textit {a}}} &= \epsilon {M_\infty } \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\left ( {1, \pm \alpha _{\textit {a}}/({M_\infty }|k_{\infty ,\textit {a}}|),\pm \kappa _{\textit {a}}/({M_\infty }|k_{\infty ,\textit {a}}|),0,\gamma - 1,1/{{M_\infty ^2}}} \right)^{\textrm {T}}}\!,\nonumber \\[2pt] \displaystyle {{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\prime}_v} &= \epsilon \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\left ( {0,0,1,1,0,0} \right)^{\textrm {T}}}\!, \nonumber \\[2pt] \displaystyle {{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\prime}_e} &= \epsilon {M_\infty } \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\left ( { - 1,0,0,0,1,0} \right)^{\textrm {T}}}\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} \displaystyle {{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\prime}_{\textit {a}}} &= \epsilon {M_\infty } \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\left ( {1, \pm \alpha _{\textit {a}}/({M_\infty }|k_{\infty ,\textit {a}}|),\pm \kappa _{\textit {a}}/({M_\infty }|k_{\infty ,\textit {a}}|),0,\gamma - 1,1/{{M_\infty ^2}}} \right)^{\textrm {T}}}\!,\nonumber \\[2pt] \displaystyle {{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\prime}_v} &= \epsilon \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\left ( {0,0,1,1,0,0} \right)^{\textrm {T}}}\!, \nonumber \\[2pt] \displaystyle {{\boldsymbol{q}}^{\prime}_e} &= \epsilon {M_\infty } \boldsymbol{\cdot }{\left ( { - 1,0,0,0,1,0} \right)^{\textrm {T}}}\!. \end{align}

Here,

![]() $w^{\prime}_{\textit {a}}$

and

$w^{\prime}_{\textit {a}}$

and

![]() $u^{\prime}_{\textit {v}}$

become zero owing to the superimposition of

$u^{\prime}_{\textit {v}}$

become zero owing to the superimposition of

![]() $\pm \beta$

waves and the zero angle of inclination for vortical waves, respectively. One can easily prove that the Chu’s energy density, extensively studied in stability analyses, is close to each other for the fundamental waves in the free stream, provided that

$\pm \beta$

waves and the zero angle of inclination for vortical waves, respectively. One can easily prove that the Chu’s energy density, extensively studied in stability analyses, is close to each other for the fundamental waves in the free stream, provided that

![]() $\phi =0^{\circ }$

. In detail, Chu’s energy density is constituted by kinetic energy and a positive definite thermodynamic energy of fluctuations, which is defined by (Chu Reference Chu1965)

$\phi =0^{\circ }$

. In detail, Chu’s energy density is constituted by kinetic energy and a positive definite thermodynamic energy of fluctuations, which is defined by (Chu Reference Chu1965)

With the scaling in (3.13), (3.14) yields the relation

This equivalence somewhat justifies the strength measurement criterion for free-stream disturbances by Zhong (Reference Zhong2001).

3.3. Broadband disturbance model

On the far-field boundary of the simulation, a 3-D broadband model of the disturbance is employed, resembling that of Cerminara & Sandham (Reference Cerminara and Sandham2020). The merit of the broadband model is that the flow is allowed to select preferential frequencies and wavenumbers naturally. Part 1 of this work (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025) replicated the experimental transition reversal by using this model, which suggests that the model is a useful choice. The harmonic perturbation for a Fourier mode (

![]() $m$

,

$m$

,

![]() $n$

) with respect to the frequency and the spanwise wavenumber, respectively, is given by

$n$

) with respect to the frequency and the spanwise wavenumber, respectively, is given by

where

![]() $m = 1,2,\ldots ,{M_f }$

,

$m = 1,2,\ldots ,{M_f }$

,

![]() $n = 0,1,\ldots ,{N_\beta }$

and

$n = 0,1,\ldots ,{N_\beta }$

and

![]() ${{\boldsymbol{B}}_m}\in \mathbb{R}$

is the vector of frequency-dependent dimensionless amplitudes. The subscripts ‘

${{\boldsymbol{B}}_m}\in \mathbb{R}$

is the vector of frequency-dependent dimensionless amplitudes. The subscripts ‘

![]() $m$

’ and ‘

$m$

’ and ‘

![]() $n$

’ represent the

$n$

’ represent the

![]() $m$

th frequency component and the

$m$

th frequency component and the

![]() $n$

th spanwise-wavenumber component, respectively. Here

$n$

th spanwise-wavenumber component, respectively. Here

![]() $M_f$

and

$M_f$

and

![]() $N_\beta$

are the total numbers of frequencies and non-zero spanwise wavenumbers, respectively. The symbols

$N_\beta$

are the total numbers of frequencies and non-zero spanwise wavenumbers, respectively. The symbols

![]() $\psi _{m,n}$

(

$\psi _{m,n}$

(

![]() $n\ne 0$

) and

$n\ne 0$

) and

![]() $\varphi _{m,n}$

represent random constant phase angles. In other words, once all the phase angles are randomly generated at the beginning, the angle values will not change with time. The phase angles are also unchanged for different DNS cases, such that the effect of the initial phase difference is excluded. For

$\varphi _{m,n}$

represent random constant phase angles. In other words, once all the phase angles are randomly generated at the beginning, the angle values will not change with time. The phase angles are also unchanged for different DNS cases, such that the effect of the initial phase difference is excluded. For

![]() $n = 0$

, it is enforced that

$n = 0$

, it is enforced that

![]() ${\beta _0} = {\psi _{m,0}} = 0$

. Furthermore,

${\beta _0} = {\psi _{m,0}} = 0$

. Furthermore,

![]() ${\omega _m} = 2\pi {f_m}$

, where

${\omega _m} = 2\pi {f_m}$

, where

![]() $f_m$

is the frequency. In fact, (3.16) is obtained by combining (3.2) and (3.12), except that random phases are introduced for different Fourier harmonics. For a fixed frequency, the components of the vector

$f_m$

is the frequency. In fact, (3.16) is obtained by combining (3.2) and (3.12), except that random phases are introduced for different Fourier harmonics. For a fixed frequency, the components of the vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{B}_m$

, i.e. the primitive variables, are forced to obey (3.13).

$\boldsymbol{B}_m$

, i.e. the primitive variables, are forced to obey (3.13).

The amplitude

![]() ${\boldsymbol{B}}_m$

is set equal for each spanwise-wavenumber component. In other words, no preferential spanwise wavenumber is assumed, and the flow will naturally select appropriate spanwise scales to amplify. This ad hoc set-up is less perfect than adopting a rigorously measured spatial spectrum of tunnel noise. However, we have not found any available measurement database to fit such a wavenumber scaling, as the frequency spectrum is of more concern in experiments. At least, the behaviour of the wavenumber distribution does not affect the experimental transition reversal trend, as shown in Part 1 (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). The current same wavenumber set-up for all the cases would isolate the effect of the free-stream-disturbance form, which is sufficient for the present objective. The frequency-dependent dimensional amplitude of the pressure fluctuation

${\boldsymbol{B}}_m$

is set equal for each spanwise-wavenumber component. In other words, no preferential spanwise wavenumber is assumed, and the flow will naturally select appropriate spanwise scales to amplify. This ad hoc set-up is less perfect than adopting a rigorously measured spatial spectrum of tunnel noise. However, we have not found any available measurement database to fit such a wavenumber scaling, as the frequency spectrum is of more concern in experiments. At least, the behaviour of the wavenumber distribution does not affect the experimental transition reversal trend, as shown in Part 1 (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). The current same wavenumber set-up for all the cases would isolate the effect of the free-stream-disturbance form, which is sufficient for the present objective. The frequency-dependent dimensional amplitude of the pressure fluctuation

![]() $p_m^{\prime\ast }$

is determined by the relation

$p_m^{\prime\ast }$

is determined by the relation

\begin{equation} p_m^{\prime \ast} /{p_\infty ^ \ast } = \left \{ \begin{array}{ll} \sqrt {{C_L}f_m^{ * - 1}\Delta {f^ * }/2}, &f_m^ * \leqslant 40\ {\textrm {kHz}},\\[5pt] \sqrt {{C_U}f_m^{ * - 3.5}\Delta {f^ * }/2}, &\text{otherwise}, \end{array} \right . \end{equation}

\begin{equation} p_m^{\prime \ast} /{p_\infty ^ \ast } = \left \{ \begin{array}{ll} \sqrt {{C_L}f_m^{ * - 1}\Delta {f^ * }/2}, &f_m^ * \leqslant 40\ {\textrm {kHz}},\\[5pt] \sqrt {{C_U}f_m^{ * - 3.5}\Delta {f^ * }/2}, &\text{otherwise}, \end{array} \right . \end{equation}

which is fitted from the measured frequency spectra of noise in the Arnold engineering development complex hypervelocity wind tunnel 9 (Marineau et al. Reference Marineau, Moraru, Lewis, Norris, Lafferty and Johnson2015; Balakumar & Chou Reference Balakumar and Chou2018). The law of

![]() $f_m^{ * - 3.5}$

at high frequencies has been validated by the measured noise data in various tunnels with

$f_m^{ * - 3.5}$

at high frequencies has been validated by the measured noise data in various tunnels with

![]() $M_\infty$

ranging from 6 to 14 (Duan et al. Reference Duan2019). The law of

$M_\infty$

ranging from 6 to 14 (Duan et al. Reference Duan2019). The law of

![]() $f_m^{ * - 1}$

at lower frequencies was also verified by the DNS data of the tunnel noise at different Mach numbers (Duan et al. Reference Duan2019). The amplitude constants are

$f_m^{ * - 1}$

at lower frequencies was also verified by the DNS data of the tunnel noise at different Mach numbers (Duan et al. Reference Duan2019). The amplitude constants are

![]() ${C_L} = 3.953 \times {10^{ - 4}}$

and

${C_L} = 3.953 \times {10^{ - 4}}$

and

![]() ${C_U} = 126.5 \times {10^6}$

in SI units. According to the preceding work (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025), the current amplitude leads to a linear response of the boundary layer in 2-D simulations. Based on the dimensional

${C_U} = 126.5 \times {10^6}$

in SI units. According to the preceding work (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025), the current amplitude leads to a linear response of the boundary layer in 2-D simulations. Based on the dimensional

![]() $p_m^{\prime\ast }$

from (3.17), the dimensionless pressure fluctuation

$p_m^{\prime\ast }$

from (3.17), the dimensionless pressure fluctuation

![]() $p_m^{\prime}=p_m^{\prime\ast }/(\rho ^{\ast }_{\infty } {u}^{\ast 2}_{\infty })$

is determined to calculate the

$p_m^{\prime}=p_m^{\prime\ast }/(\rho ^{\ast }_{\infty } {u}^{\ast 2}_{\infty })$

is determined to calculate the

![]() $\epsilon$

in (3.13) for each frequency component. In this way, the reported law of the frequency spectrum is incorporated into the 3-D broadband disturbance. In reality, note that vorticity or entropy waves should have their own spectra. However, there are hardly available experimentally measured data or laws in the literature for vorticity waves or entropy waves in atmospheric environments, which the present work intends to mimic. Furthermore, it is likely difficult to reach a unified scaling law for different heights (say 0–100 km) resembling (3.17) in various facilities. Given the challenge, (3.17) is employed for all the disturbance forms to isolate the effect of the dispersion relation. This strategy at least provides some useful conclusions in this preliminary stage of investigating the flight/ground discrepancy.

$\epsilon$

in (3.13) for each frequency component. In this way, the reported law of the frequency spectrum is incorporated into the 3-D broadband disturbance. In reality, note that vorticity or entropy waves should have their own spectra. However, there are hardly available experimentally measured data or laws in the literature for vorticity waves or entropy waves in atmospheric environments, which the present work intends to mimic. Furthermore, it is likely difficult to reach a unified scaling law for different heights (say 0–100 km) resembling (3.17) in various facilities. Given the challenge, (3.17) is employed for all the disturbance forms to isolate the effect of the dispersion relation. This strategy at least provides some useful conclusions in this preliminary stage of investigating the flight/ground discrepancy.

In the present model, the dimensional frequency ranges from

![]() $f_1^ {\ast }=10$

kHz to

$f_1^ {\ast }=10$

kHz to

![]() $f_{\textrm{max}}^ {\ast }=1000$

kHz with an interval

$f_{\textrm{max}}^ {\ast }=1000$

kHz with an interval

![]() $\Delta {f^ {\ast }} = 5$

kHz. The lowest frequency

$\Delta {f^ {\ast }} = 5$

kHz. The lowest frequency

![]() $f_1^ {\ast }$

is not decreased further, because the experimental data for the fitting of (3.17) showed insufficient resolution in a low-frequency range. Regarding the spanwise wavenumber, it ranges from

$f_1^ {\ast }$

is not decreased further, because the experimental data for the fitting of (3.17) showed insufficient resolution in a low-frequency range. Regarding the spanwise wavenumber, it ranges from

![]() ${\beta ^{\ast } _1}=2\pi /\lambda ^{\ast }_1$

to

${\beta ^{\ast } _1}=2\pi /\lambda ^{\ast }_1$

to

![]() $\beta _{\textrm{max}}^ {\ast }=40{\beta ^{\ast } _1}$

with an interval

$\beta _{\textrm{max}}^ {\ast }=40{\beta ^{\ast } _1}$

with an interval

![]() $\Delta {\beta ^ * }=\beta ^{\ast }_1$

, which is expected to achieve a broadband state. Here, the fundamental spanwise wavelength

$\Delta {\beta ^ * }=\beta ^{\ast }_1$

, which is expected to achieve a broadband state. Here, the fundamental spanwise wavelength

![]() $\lambda ^{\ast }_1=L_z^{\ast }=9\ \text{mm}=10\lambda ^{\ast }_{\textit {streak}}$

, where

$\lambda ^{\ast }_1=L_z^{\ast }=9\ \text{mm}=10\lambda ^{\ast }_{\textit {streak}}$

, where

![]() $\lambda ^{\ast }_{\textit {streak}}$

is the spacing of the most amplified streamwise streak in the work of Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). Therefore, the spanwise width of the computational domain contains 10 preferential streaks, which is deemed sufficient. The corresponding spanwise wavelength considered in the numerical forcing varies from 0.225 to 9 mm. The mode numbers are

$\lambda ^{\ast }_{\textit {streak}}$

is the spacing of the most amplified streamwise streak in the work of Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). Therefore, the spanwise width of the computational domain contains 10 preferential streaks, which is deemed sufficient. The corresponding spanwise wavelength considered in the numerical forcing varies from 0.225 to 9 mm. The mode numbers are

![]() $M_f = 199$

and

$M_f = 199$

and

![]() ${N_\beta } = 40$

accordingly.

${N_\beta } = 40$

accordingly.

Eventually, the total perturbation of the variable

![]() $\boldsymbol{\varPsi }^{\prime}$

is given by

$\boldsymbol{\varPsi }^{\prime}$

is given by

\begin{equation} {\boldsymbol{\varPsi }} ^{\prime}(x,z,t) = A_{\textit {rescaled}}\sum \limits _{n = 0}^{{N_\beta }} {\sum \limits _{m = 1}^{{M_f}} {{{\boldsymbol{\varPsi }} ^{\prime}_{m,n}}} }, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} {\boldsymbol{\varPsi }} ^{\prime}(x,z,t) = A_{\textit {rescaled}}\sum \limits _{n = 0}^{{N_\beta }} {\sum \limits _{m = 1}^{{M_f}} {{{\boldsymbol{\varPsi }} ^{\prime}_{m,n}}} }, \end{equation}

where the amplitude rescaling parameter is set to

![]() $A_{\textit {rescaled}}=0.366$

. With this set-up, the spanwise averaged

$A_{\textit {rescaled}}=0.366$

. With this set-up, the spanwise averaged

![]() $p^{\ast \prime }_{\infty ,\textit {rms}}$

of the 3-D wave is numerically equal to the 2-D counterpart determined by (3.17) for the baseline slow acoustic wave case. The subscript ‘rms’ denotes root mean square. For this baseline case, the detailed intensity of the pressure fluctuation is

$p^{\ast \prime }_{\infty ,\textit {rms}}$

of the 3-D wave is numerically equal to the 2-D counterpart determined by (3.17) for the baseline slow acoustic wave case. The subscript ‘rms’ denotes root mean square. For this baseline case, the detailed intensity of the pressure fluctuation is

![]() $p^{\ast \prime }_{\infty ,\textit {rms}}/\bar {p}^{\ast }_{\infty }=2.85\,\%$

. This amplitude is larger than that in Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025), which would probably lead to an earlier transition. Nonetheless, comparative studies are still valid under the same amplitude rescaling for different fundamental free-stream waves. For each time step during marching, the instantaneous variable on the far-field boundary is forced to be the sum of the base flow and the perturbed ones.

$p^{\ast \prime }_{\infty ,\textit {rms}}/\bar {p}^{\ast }_{\infty }=2.85\,\%$

. This amplitude is larger than that in Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025), which would probably lead to an earlier transition. Nonetheless, comparative studies are still valid under the same amplitude rescaling for different fundamental free-stream waves. For each time step during marching, the instantaneous variable on the far-field boundary is forced to be the sum of the base flow and the perturbed ones.

3.4. Case description

As shown in table 1, five cases are simulated with the same computational domain, mesh resolution and strength of the forcing prescribed by (3.13). The only difference is the type of free-stream disturbances and the angle of incidence

![]() $\phi$

. The chosen grid spacings can achieve mesh convergence regarding the streamwise evolution of statistical quantities (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). To save computational cost, the present streamwise length and spanwise width of the computational domain are reduced to

$\phi$

. The chosen grid spacings can achieve mesh convergence regarding the streamwise evolution of statistical quantities (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025). To save computational cost, the present streamwise length and spanwise width of the computational domain are reduced to

![]() $L_x=155$

and

$L_x=155$

and

![]() $L_z=9$

, respectively. The reduction in the streamwise domain length is acceptable because of the earlier transition onset subject to an increased forcing amplitude. The decrease in the spanwise width is also safe to maintain the same transitional characterisation according to precursor tests in Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025).

$L_z=9$

, respectively. The reduction in the streamwise domain length is acceptable because of the earlier transition onset subject to an increased forcing amplitude. The decrease in the spanwise width is also safe to maintain the same transitional characterisation according to precursor tests in Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025).

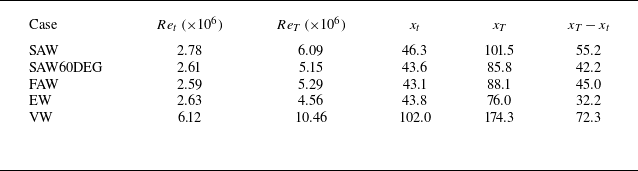

Table 1. Case description for DNS.

With regard to the mesh, the wall-normal distribution of the node is clustered near the wall and the shock using a hyperbolic tangent function. In the wall-normal direction, at least 140 points are placed in the fully developed turbulent boundary layers. The grid spacing is uniform in the spanwise direction. The spacing is almost uniform in the streamwise direction, except clustered in the vicinity of the leading edge. As in the former work, 22 points are used in the spanwise direction for each spacing of the most amplified streamwise streak. In the remainder of the paper, the mean and root-mean-square (r.m.s.) quantities are obtained after statistical stationarity is reached. The statistical convergence is also verified by comparing the results from different temporal windows.

3.5. Linear stability analysis

The linear stability theory (LST) is utilised to identify the normal-mode instability. The primitive variable vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}=(u,v,p,w,T)^{\text{T}}$

can be decomposed into

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}=(u,v,p,w,T)^{\text{T}}$

can be decomposed into

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}(\xi ,\eta ,z,t)=\bar {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}}(\xi ,\eta)+\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}^{\prime}(\xi ,\eta ,z,t)$

. With the normal-mode ansatz, the small-amplitude disturbance can be expressed by

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}(\xi ,\eta ,z,t)=\bar {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}}(\xi ,\eta)+\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}^{\prime}(\xi ,\eta ,z,t)$

. With the normal-mode ansatz, the small-amplitude disturbance can be expressed by

![]() $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}^{\prime} = \hat {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}}(\eta)\exp { [ {{\textrm {i}} ( {\tilde {\alpha }\xi +\beta z - \omega t})} ]}+ {\textrm {c}}{\textrm {.c}}{\textrm {.}}$

, where

$\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}^{\prime} = \hat {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}}(\eta)\exp { [ {{\textrm {i}} ( {\tilde {\alpha }\xi +\beta z - \omega t})} ]}+ {\textrm {c}}{\textrm {.c}}{\textrm {.}}$

, where

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}}$

denotes the eigenfunction and

$\hat {\boldsymbol{\mathcal{Q}}}$

denotes the eigenfunction and

![]() $\tilde {\alpha }$

is the complex streamwise wavenumber. Under the quasi-parallel flow assumption, the linear stability equation can then be derived from the linearised N–S equation and transformed to a complex eigenvalue problem. Dirichlet boundary conditions are enforced for

$\tilde {\alpha }$

is the complex streamwise wavenumber. Under the quasi-parallel flow assumption, the linear stability equation can then be derived from the linearised N–S equation and transformed to a complex eigenvalue problem. Dirichlet boundary conditions are enforced for

![]() $\hat u, \hat v, \hat w$

and

$\hat u, \hat v, \hat w$

and

![]() $\hat T$

. The local spatial growth rate

$\hat T$

. The local spatial growth rate

![]() $\sigma =-\tilde {\alpha }_i$

is positive if the eigenmode is unstable. The linear stability analysis is performed by our in-house code, which has been well validated by benchmark cases. A spectral collocation method is employed for discretisation to obtain the eigenspectrum. More details can be found in Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025).

$\sigma =-\tilde {\alpha }_i$

is positive if the eigenmode is unstable. The linear stability analysis is performed by our in-house code, which has been well validated by benchmark cases. A spectral collocation method is employed for discretisation to obtain the eigenspectrum. More details can be found in Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Hao and Wen2025).

4. Solution of fundamental waves in the parameter space

As remarked in § 3.3, a maximum total number of

![]() $M_f\times (N_\beta +1)=199\times 41=8159$

Fourier components will be added in the 3-D broadband disturbance model. As shown by (3.4),

$M_f\times (N_\beta +1)=199\times 41=8159$

Fourier components will be added in the 3-D broadband disturbance model. As shown by (3.4),

![]() $\omega = {\alpha _{v,e}}$

and, thus,

$\omega = {\alpha _{v,e}}$

and, thus,

![]() $\beta _{v,e} = \omega _{v,e}\tan \theta _{v,e}$

. Hence, for purely convected vortical/entropic waves, the streamwise wavenumber

$\beta _{v,e} = \omega _{v,e}\tan \theta _{v,e}$

. Hence, for purely convected vortical/entropic waves, the streamwise wavenumber

![]() $\alpha$

is decoupled from the spanwise wavenumber

$\alpha$

is decoupled from the spanwise wavenumber

![]() $\beta$

and there is no explicit limit on the wave angle

$\beta$

and there is no explicit limit on the wave angle

![]() $\theta _{v,e}$

. As a result, there always exist solutions for planar vortical/entropic waves with given

$\theta _{v,e}$

. As a result, there always exist solutions for planar vortical/entropic waves with given

![]() $\omega$

and

$\omega$

and

![]() $\beta$

.

$\beta$

.

Figure 4. Contour of the oblique wave angle

![]() $\theta$

in the considered parameter space in § 3.3 for the incident angle

$\theta$

in the considered parameter space in § 3.3 for the incident angle

![]() $\phi =0^{\circ }$

(contour) and

$\phi =0^{\circ }$

(contour) and

![]() $\phi =60^{\circ }$

(dashed line): (a) slow acoustic wave and (b) fast acoustic wave.

$\phi =60^{\circ }$

(dashed line): (a) slow acoustic wave and (b) fast acoustic wave.

For acoustic waves, by combining (3.7) and

![]() $\beta _{\textit {a}}=\alpha _{\textit {a}} \tan \theta _{\textit {a}}$

, one can obtain

$\beta _{\textit {a}}=\alpha _{\textit {a}} \tan \theta _{\textit {a}}$

, one can obtain

where the plus/minus sign is taken for the fast/acoustic wave. Provided that

![]() $\beta _{\textit {a}}$

,

$\beta _{\textit {a}}$

,

![]() $\omega$

and the assumed constant angle of incidence

$\omega$

and the assumed constant angle of incidence

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}$

are given, (4.1) yields a quadratic equation with respect to

$\phi _{\textit {a}}$

are given, (4.1) yields a quadratic equation with respect to

![]() $\tan \theta _{\textit {a}}$

, of which the solution is

$\tan \theta _{\textit {a}}$

, of which the solution is

where

![]() $A = M_\infty ^2{\omega ^2}/{\beta _{\textit {a}} ^2} - 1,B = - 2M_\infty ^2\omega /\beta _{\textit {a}}$

and

$A = M_\infty ^2{\omega ^2}/{\beta _{\textit {a}} ^2} - 1,B = - 2M_\infty ^2\omega /\beta _{\textit {a}}$

and

![]() $C = M_\infty ^2 - {\tan ^2}\phi _{\textit {a}} - 1$

. The two roots of (4.2), with a positive or negative sign, will be substituted back into (4.1). The purpose is to verify that the final solution of

$C = M_\infty ^2 - {\tan ^2}\phi _{\textit {a}} - 1$

. The two roots of (4.2), with a positive or negative sign, will be substituted back into (4.1). The purpose is to verify that the final solution of

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}}$

satisfies (4.1) and the associated relation

$\theta _{\textit {a}}$

satisfies (4.1) and the associated relation

![]() $\beta _{\textit {a}}=\alpha _{\textit {a}} \tan \theta _{\textit {a}}$

. In addition, the wave angle limit should also be satisfied. For slow acoustic waves,

$\beta _{\textit {a}}=\alpha _{\textit {a}} \tan \theta _{\textit {a}}$

. In addition, the wave angle limit should also be satisfied. For slow acoustic waves,

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}}\in (-78.46^\circ ,78.46^\circ)$

for

$\theta _{\textit {a}}\in (-78.46^\circ ,78.46^\circ)$

for

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}=0$

, while the upper and lower limits are slightly changed for

$\phi _{\textit {a}}=0$

, while the upper and lower limits are slightly changed for

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}=60^\circ$

. For fast acoustic waves with

$\phi _{\textit {a}}=60^\circ$

. For fast acoustic waves with

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}=0$

, (3.8) implies that

$\phi _{\textit {a}}=0$

, (3.8) implies that

![]() $\cos {\theta _{\textit {a}}}+1/M_{\infty }\gt 0$

, which means that

$\cos {\theta _{\textit {a}}}+1/M_{\infty }\gt 0$

, which means that

![]() $|\theta _{\textit {a}}|\lt \arccos (-1/M_{\infty })\approx 101.53^\circ$

. Similar to slow acoustic waves, the effect of a non-zero

$|\theta _{\textit {a}}|\lt \arccos (-1/M_{\infty })\approx 101.53^\circ$

. Similar to slow acoustic waves, the effect of a non-zero

![]() $\phi _{\textit {a}}$

does not change the critical

$\phi _{\textit {a}}$

does not change the critical

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}}$

evidently for fast acoustic waves. It finally turns out that there exist solutions for the fast or slow acoustic wave if and only if the positive or negative sign is taken in (4.2), respectively.

$\theta _{\textit {a}}$

evidently for fast acoustic waves. It finally turns out that there exist solutions for the fast or slow acoustic wave if and only if the positive or negative sign is taken in (4.2), respectively.

Figure 4 depicts the resulting oblique wave angle

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}}$

in the considered (discretised) parameter space of

$\theta _{\textit {a}}$

in the considered (discretised) parameter space of

![]() $(\omega ,\beta)$

. The contours and dashed lines mark the isolines of the oblique wave angle

$(\omega ,\beta)$

. The contours and dashed lines mark the isolines of the oblique wave angle

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}}$

for

$\theta _{\textit {a}}$

for

![]() $\phi =0^{\circ }$

(contour) and

$\phi =0^{\circ }$

(contour) and

![]() $\phi =60^{\circ }$

(dashed line), respectively. Obviously, the non-zero angle of incidence

$\phi =60^{\circ }$

(dashed line), respectively. Obviously, the non-zero angle of incidence

![]() $\phi$

revises the oblique wave angle

$\phi$

revises the oblique wave angle

![]() $\theta$

to a certain degree, while the general distribution of

$\theta$

to a certain degree, while the general distribution of

![]() $\theta$

stays similar. As shown in figure 4 for the whole parameter space, there always exists a solution of

$\theta$

stays similar. As shown in figure 4 for the whole parameter space, there always exists a solution of

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}}$

within the respective limit values for slow and fast acoustic waves. For fast acoustic waves, figure 4(b) shows that

$\theta _{\textit {a}}$

within the respective limit values for slow and fast acoustic waves. For fast acoustic waves, figure 4(b) shows that

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}}$

can exceed

$\theta _{\textit {a}}$

can exceed

![]() $90^{\circ }$

. Above and below the boundary

$90^{\circ }$

. Above and below the boundary

![]() $\theta _{\textit {a}}=90^{\circ }$

, one finds that

$\theta _{\textit {a}}=90^{\circ }$

, one finds that

![]() $\text{sgn}(\alpha _{\textit {a}})=-1$

and

$\text{sgn}(\alpha _{\textit {a}})=-1$

and

![]() $\text{sgn}(\alpha _{\textit {a}})=1$

, respectively. This suggests that the streamwise component of the phase velocity, i.e.

$\text{sgn}(\alpha _{\textit {a}})=1$

, respectively. This suggests that the streamwise component of the phase velocity, i.e.

![]() $\omega /\alpha _{\textit {a}}$

, can be negative for fast acoustic waves. However, as discussed in § 3.2, the streamwise component of the group velocity is always positive for fast acoustic waves in supersonic flows, regardless of the direction of the phase velocity. Hence, the streamwise direction of energy propagation is still along the

$\omega /\alpha _{\textit {a}}$